WHISPERS

OF The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

ISSUE 52

p04

NATASHA DEMIRBAG

Chairman’s Column FAREED F FETTO p06

Exploring the possibilities

HIS HONOUR EDWARD BAILEY

p14

50 Years with Party Walls

DAVID MOON

p24

Is the Party Wall etc wAct 1996 optional?

MATTHEW HEARSUM

p28

Is the Party Wall etc Act 1996 optional?

THE SOCIETY’S VIEW

p38

Risks, Costs and Pitfalls of seeking injunctions

HIS HONOUR EDWARD BAILEY

p09

From the vaults

LAWRENCE HURST

p20

Letter to the editor

p27

The Right to reply

MATTHEW HEARSUM

p31

Dealing with the bloodyminded building owner; Party Structure Notices, and going to Court

HIS HONOUR EDWARD BAILEY

p44

Readers Wall

CHRIS TOMLIN

2 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society Contents ISSUE

52 p03 Welcome

Welcome to the Spring edition

Natasha Demirbag FTPS

FOLLOWING HOT ON THE HEELS OF THE Winter 2023 issue (Issue 51) we have now sprung a Spring edition to share with you. We are fortunate to be able to bring you a copy of Mathew Hearsum’s recent article that was published in the Estates Gazette towards the end of last year and a letter to the Editors that was received in response to the publication of Matthew’s article. Matthew’s article has prompted much discussion within the membership of the Society and so the management team have decided to share their own personal thoughts on the matter within Whispers.

We have three articles for publication by retired judge His Honour Edward Bailey, which continue along the legal theme. They deal with the “Bloody-Minded” Building Owner and also the risks, costs and pitfalls of seeking

injunctions. Chris Tomlin has kindly shared with us photos of a large deep basement excavation project in central London, and we also have an article from David Moon.

natasha@natashademirbag.com

3 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Chairman’s column

Fareed F Fetto FTPS

PREFACE

The address, which, on the occasion was abridged due to time restrictions, has now been modified to read more as an article than an oral address. Items omitted have been reinstated.

FELLOW FELLOWS

“The Intended Business of the Society Prescribed by the Constitution”

Someone somewhere has placed confidence in me to the extent that I am capable of speaking on an austere subject such as this.

I am still recovering from the fact that anyone should have voted me in as chairperson during this very significant milestone: the transition into a Society. I take this opportunity to honour Shirley Waldron, the then outgoing

chairperson, who should have been the chairperson at transition but was obliged to step down due to extenuating personal circumstances.

Now, my mission is to continue to team up with others to build upon the foundation upon which the transition has been made.

Foundations are important, and while engineering-based party wall surveyors and myself feel quite at home taking an interest in foundations, all party wall surveyors take an interest in cracks!

We do not want them, but we are happy to record them –they give our schedules of condition a certain sense of ‘value for money’, compared with the case of a newly decorated or well-maintained building leaving us bereft of anything to record!

Cracks can develop in buildings for various reasons, even buildings on sound foundations, while, by contrast, cracks are very likely to develop in buildings built on weak inadequate foundations.

Get the foundation right, and you increase the chances of the building being crack-free!

So, here, after my short lesson on foundations brought to you absolutely free of charge, is the point I am making –just in case it has been missed.

The foundation of the Society is, of course, the Constitution, we are the builders, building in accordance with an award, method statements, and, of course, applicable regulations.

“Wait,” you might say, “I never wrote the constitution, but now I find myself being asked to build upon it” –

My friend, if you were at the original inaugural Fellowship meeting, and you watched, whether voting for or against, the constitution come into being, you became responsible for it!

On the happy side, I remind us all that we are the Fellowship. We are the boss. We are the champions!

As such we have the power to change anything, even if the concrete has hardened!

Friends, we have no power if we are not present. By that, I mean present in mind intent, activity, participation, agreement, disagreement, debate, discussion, production, promotion, collaboration cooperation enthusiastically, being US and US instead of US and THEM!

No more talk of ‘London-centric’. We are one Society with many Branches who are invited to take part in its business; sources are available to all, the steering wheel is available to all. The door is wide open and you and I are invited to enter.

4 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Any idea of there being some elite group, lording it over the membership, doing whatever it likes is not part of the Society culture and if any such thing exists, call it out, and come, join me and others in eradicating it.

Any idea of feeling separated and isolated from the membership, the business, or the governing of the Society is in stark contradiction of our values; such an idea should not be entertained by anyone.

Today, let’s continue to build the Society and make it what we would like it to be!

I would like to thank everyone of you, if I may do so on behalf of eachother, and on behalf of the Society: Thank you, thank you for the effort and hard work you have, and continue, to put in to the Society, and for those who found it practicable to attend, thank you for being here, and for those who did not, thank you for being there [that is, online]!

Of greater significance today, as we roll on towards our 50th Anniversary celebrations which we will celebrate in more depth and breadth, is the deep gratitude and honour we owe to certain of us who have spent years, even decades, working for the establishment, development and future of our organisation whether originally as a Club, or at present as a Society, in particular the two vision-bearers, Andrew Schofield and Stuart Birrell, and significantly Graham North. Both the vision-bearers declare that they could not have achieved what they did without Graham’s support and encouragement.

Today the Management Board is saying good-bye to some of the fellow champions who have worked hard both for the Club and the Society, as I have said, for many years, and although we will, no doubt, hang on to their apron strings for a while, we will have to release them as those deserving of a break, and, of course, of honour, and get on with the business of the Society even though it would be a hard act to follow!

So, what is the business of the Society?

Section 4.1 of the Constitution includes the words:

“……the object of the Society is to promote, maintain, improve and advance the education, standards of practice and awareness of members in matters relating to Party Walls and allied subjects especially those governed by the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 and subsequent party wall legislation.”

Under this general objective statement, we are working on the various aspects as you heard in the earlier part of this meeting.

What does it not say?

Allow me please to pick this point up and then bury it for good!

It does not say “compared with” !

We are not in competition with other organisations; we are not disrespectful of them neither do we look down upon them. We have our objectives and they have theirs. Some may converge and some may diverge. Even if we were running against them, which we are not, remember, the runner looking left and right reduces their chances of running in a straight line!

Let’s look straight ahead, minding our own business, setting the gold standard, and doing it well! To me, the gold standard speaks to me more than all considerations. Remember, it was implied in the old Club motto.

We are together focussed on the objective.

Here are some key motivating words from the Constitution.

Notice, they are all words of ACTION!

Promote

Maintain

Improve

Advance I like this one!

In connection with:

Education Standards

Awareness To this I would add, not only members, but the public at large

How can we achieve this …… “business”?

Promote, maintain, improve, advance…?

You are the bosses, the Management Board is the implementer of the objectives, but it is the Fellowship which determines them. I encourage you to play your part, and I say to those who are: thank you.

Your contribution is needed and valued.

Tell us, Fellowship, what needs to be done and let’s make the changes and advance!

How radical?

As radical as you like!

As mentioned in my formal report, I see plenty of positives which have been achieved during the year, but how should we develop, and will you, the Fellowship, all the Branches, take part and pull with us?

How can we improve what we have done?

What future should we map out for the Society –what further objectives, what inking in of existing objectives should we put our hand to?

How would you complete this sentence:

“I am proud to be a member of the Society because…..”

Here is what I would say:

“I am proud to be a member of the Pyramus & Thisbe Society because it is a fellowship of well-respected, wellexperienced and newly-practising mutually courteous members with like interests and vision, and because the Society is rooted in both the formation of the current Act, and a wealth of knowledge and experience I can freely draw from. It provides good resources for me to maintain and increase my knowledge of party wall and associated matters, it is enthusiastically promoting its objectives and it is good fun to be part of it”

You will be pleased to know that I am coming to the end of my address, and in so doing, I encourage you to express your views freely as we embark on an open discussion, questions and answers (if we know them!) and suggestions.

[The floor was then opened for discussion]

fetto@fareedfetto.co.uk

5 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Exploring the possibilities

His Honour Edward Bailey

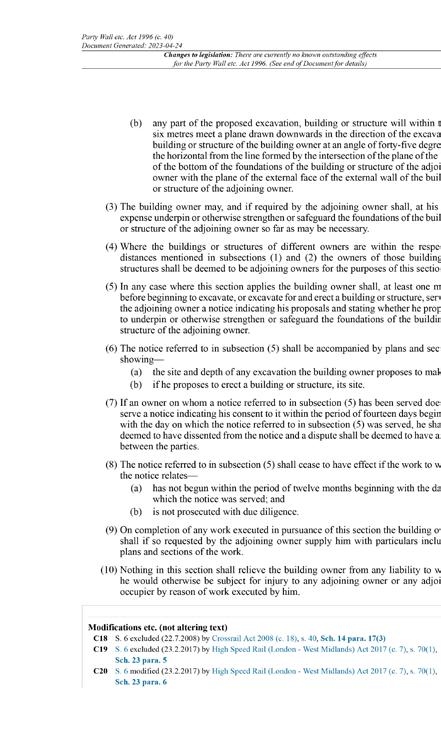

1What can the party wall surveyor do if it is apparent that there is something wrong with a party wall, but an external inspection does not reveal the problem? The answer in most cases will be to open up and investigate. But will the 1996 Act allow it?

2

In the rather ancient case of Hobbs, Hart & Co v Grover [1898] 1 Ch 11 the Building Owner had purchased a house at 75 Cheapside in the City of London. The BO wanted to pull building down and rebuild it. The wall between 75 and 76 Cheapside was accepted to be a party wall, but the BO was not certain of the condition of the wall and whether, and if so to what extent, that wall might require work. The BO’s surveyor decided to serve a party structure notice (PSN) under s.90 of the London Building Act 1894 which simply recited the whole of s.88 of the 1894 Act, the predecessor to what is now s.2(2) of the 1996 Act. (This appears to have been a general approach at the time). The Adjoining Owner objected to the notice, complaining that it did not state “the nature and particulars of the proposed work”. In response the BO argued that it was not possible for him to give a detailed notice before he knew the condition of

the party wall, and this would not be known until after the works had begun.

3

The matter came before Channell J who adopted a very pragmatic approach to the dispute. The Learned Judge decided to uphold the PSN on the BO’s undertaking not to act on any part of the notice which involved repair, pulling down, rebuilding or raising the party wall without first giving the AO inspection of his plans under an amended PSN, a month to serve a counter-notice, and a further period of 10 days to appoint an adjoining owner surveyor who could then resolve any dispute with the building owner’s surveyor in the usual way.

4

This was all too practical for the Court of Appeal. Finding that the provisions of the 1894 Act did not allow such an approach the Court overturned the Judge’s decision. The Court’s judgment (presumably after setting out the basic facts) extends to the whole of two sentences! Given by Lindley MR it reads “In my opinion the notice ought to be so clear and intelligible that the adjoining owner may be able to see what counter-notice he should

6 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

given to the building owner under s.89. This is the key to whole matter.” Chitty and Vaughan Williams LLJ concurred. Usefully, the Law Report records questions posed by their Lordships in the course of counsel’s argument, and Chitty LJ’s view on the matter appears from his question “Should not the notice be such as will enable the adjoining owner to judge whether he shall consent or object to the proposed works?”. This is perhaps a sounder basis for requiring detail in the PSN than the possibility of service of a counter-notice.

5

Intriguingly the Law Report records “Ultimately the defendant (BO) consented to amend his notice in accordance with the view taken by the Court.” Quite how he was able to do this is not clear; perhaps the BOS took the expedient of fearing the worst so as to obtain an Award which would cover anything that might have to be done, on the basis that the Award would not be so drawn as to require unnecessary work to be undertaken.

6

120 years later the appeal in Thomas Ash v Shayne Trimnell-Ritchard (19.11.2020) came before HHJ Parfitt sitting in Central London County Court. The problem facing the building owner was a leak in her basement ceiling the cause of which was not at all obvious to the two partyappointed surveyors. One possibility was that there was water ingress as a result of the connection of a side extension to the party wall by the AO, work which should have been authorised by award under the 1996 Act but in respect of which no notice had been served by the AO. But this was simply a possibility, and the party wall surveyors were quite unsure as to the precise cause. The AOS suggested some opening up to explore the source of the leak, but his preferred approach was to engage the services of a ‘damp specialist’ in the hope that such a specialist might ascertain the real cause of the leak.

7

The BOS and the 3S decided however to proceed to an award authorising the following works::

“….. namely

a. Lift, set aside and replace upon completion the decking at the rear of the AO’s extension;

b. Investigate the abutment detailing between the structure at the top of the underlying basement slab and the party wall;

c. Carry out repairs to the joint between the basement slab and the party wall;

d. Repair damp-affected plasterwork and redecorate affected surfaces within the BO’s property, redecoration to the extent required to achieve a reasonable colour match.”

The Award also provided that:

“Following the lifting of the decking described in clause 1(a) above and before carrying out the works described in clause 1(c), carry out such further investigations as are considered

necessary.

“Provide the surveyors with the results of the investigations, a photograph of the area showing the concealed fabric … And obtain their approval of a description of the proposed works and an itemised estimate of cost.”

The essence of the award was therefore an investigation followed by repair as may be found necessary.

The Judge set aside the Award. He observed at [18] that “there is no free-standing right … to carry our exploratory investigations outside of the actual entitlement to carry out work but to investigate if there is an entitlement to carry out work. If Parliament had wanted to grant such an investigatory right then it would have done so expressly. There is a long list of rights in Section 2 and the right to investigate to see whether or not you need to exercise other rights contained in the Act is not one of them, and I do not think that it is ancillary to any of the rights set out in Section 2 or otherwise, nor can it be implied and nor, as a matter of purposive construction, can the Act be said to create or give rise to such a right.”

8

In conclusion, at [21] “The surveyors had no jurisdiction to make this award because the Act does not give them the power to require or allow a party, independent of the exercise of an actual right given by the Act, to investigate and that is what this award purports to do, and that problem, the failure to identify that the award must first determine the right to execute work to which the Act is relevant is a fatal flaw throughout the very difficult to follow wording in this unfortunate and unhappy award.”

9 Is the above a fortunate and happy wording of a judgment?

10

Incidentally, the Judge went further and castigated the surveyors involved for including within the award observations, albeit expressly stated not to form part of the determination, to the effect that the adjoining owner had undertaken work to the party wall without serving notice in accordance with the provisions of the 1996 Act. The award also envisaged that these unauthorised works might have caused the leak (my emphasis). The Judge suggested at [11] that these comments would indicate to any reasonable person reading the award that the surveyors were not carrying out their function, or appeared to be carrying out their functions in a way that would fit their quasi-judicial roles. How far this criticism was merited on the facts is debatable and raises interesting questions, but these are outside the scope of this article.

11

But does the 1996 Act prevent investigatory work? What should the PWS do when uncertain as to what precise work is required? It is to be

7 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

noted that the rights granted to a building owner under s.2(2) include, at s.2(2)(f) a right “to cut into a party structure for any purpose (which may be or include the purpose of inserting a damp proof course)”. On a plain reading of the Act “for any purpose” surely means just that. Is not investigation a purpose? Investigation is regularly carried out to discover whether and if so what faults may exist in any particular part of a completed building. It is a perfectly legitimate purpose. It is not at all obvious to the author that a BO with genuine concerns as to the state of the party wall should be prevented from investigating quite what the problems are. It might be objected that investigation is not a proper stand-alone purpose, and that “any purpose” must be construed as involving a purpose connected with the Act and, perhaps, in particular connected with s.2(2) rights. The author does not advocate such a construction of the statute, but even if it were adopted it should not prevent investigation where this is necessary. Provided a party structure notice has been served identifying the right(s) under s.2(2) the BO wishes to exercise in the event that particular faults are found, and the notice has been suitably drafted, there should not be any difficulty in accepting investigation as a purpose under s.2(2)(f). In this regard the provisions of s.2(2)(b) may well be helpful. This gives the BO the right “to make good, repair, or demolish and rebuild, a party structure … in a case where such work is necessary on account of defect or want of repair of the structure or wall;”. The combination of (b) and (f) should cover most situations where an investigation is warranted.

12There remains the need to consider the extent of the work which would be allowable under s 2(2)(f) “to cut into a party structure for any purpose”. (Incidentally, s.88(8) of the London Building Act 1894 – see para 2 above – gave the BO the right “to cut into any party structure upon condition of making good all damage occasioned to the adjoining premises by such operation.”) How far can a “cut into” go? Plainly a ‘cut into’ a party structure must fall short of actual demolition, but if the purpose is to investigate a leak or a want of repair, presumably a ‘cut into’ may go as far as is necessary to make the necessary determination. “Cut into” also appears in s.2(2) (j) where the right to cut into an adjoining owner’s wall is permitted to insert a flashing or other weather-proofing of a wall erected against that wall. The context of the right in s.2(2)(j) might suggest that cutting into involves intrusion of a fairly limited extent, but there is no obvious reason why s.2(2)(f) should be interpreted by reference to another freestanding right under s.2(2). The more so because s.2(2)(f) expressly provides that “any purpose” may include the purpose of inserting a damp proof course. In the usual course an effective damp proof course requires a very extensive intrusion into the party structure, well beyond that required by the insertion of a flashing.

13

Ad ditionally to s.2(2)(f) there is s.2(2)(k) to consider. Here the BO’s right is “to execute any other necessary works incidental to the connection of a party structure with the premises adjoining it;”. Note that this right relates to “the connection of a party structure” not to the “connecting of a party structure” and so applies to an existing connection. If there is a leak at or adjacent to the connection of a party structure with adjoining premises opening up to find and remedy the leak would on the face of it come within s.(2)(2)(k).

14

Party wall surveyors tend to be practical people, and the award made in Ash was a practical award. (And I rather doubt justified the harsh words the Judge had for the surveyors involved). But as a cautionary note to surveyors, while being practical do keep an eye on the Act. Make sure that you work within it. As quoted in the Judgment in Ash it appears that the party structure notice was restricted to the rights afforded s.2(2)(b). If this is the case (and the author cannot be certain not having seen the notice and it not being quoted in its entirety in the Judgment) the surveyors missed a trick. Going back to the Award, see paragraph 7 above, the works at (a) and (d) are questionable as stand-alone works, but it seems to the author that the works at (b) and (c) could have been reworded so as to bring the work within s.2(2)(f) and or (k). Furthermore, neither (a) or (d) would appear to be work expressly requiring an award under the 1996 Act, and could have been included in the award either as part of the “manner of executing” (b) and (c) or as “any other matter arising out of or incidental to the dispute” under s.10(12)(b) or (c). The important thing is that the party structure notice in a case where exploratory works may be necessary does expressly include reference to the rights in s.2(2)(f) and (k).

15

Amendment to the 1996 Act to give the express right to undertake investigatory work to be undertaken would seem sensible. Quite how the amendment should be drafted may be the subject of some debate. For the present however a party wall surveyor should be able to carry out works of investigation in most situations by a careful use of s.2(2)(f) and (k) together with s.2(2)(b) or other rights afforded the building owner in section 2.

clams.tcc@gmail.com CREDIT 8 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

9 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society From the Vaults

Are there really two walls?

FIND OUT BEFORE YOU DEMOLISH AND AVOID SURPRISES

Lawrance Hurst

AS FIRST PUBLISHED IN WHISPERS 5 – SUMMER 2001

THE ACT IS ALL ABOUT AVOIDING surprises. Perhaps not really “all about” but its primary purpose today, as averred by the Earl of Lytton when promoting the Bill in the House of Lords is to find out about next door so that the works can take into account the interests of the neighbour and be designed, or varied if they are already designed, to minimise the implications for the next door building. Originally, starting in 1189, the party wall provisions were of course enacted to prevent the spread of fire across boundaries, but those essential measures are now enforced by other legislation, such as the Building Regulations, and our Act now deals exclusively with neighbourly issues.

When the works include demolition, one of the most important aspects, perhaps the most important, of those neighbourly issues is establishing the limits of demolition, which sends my rambling down a snake to where I started with my title - are there really two walls? Superficial evidence, such as straight joints on the front and rear elevations and what looks like two parapets may lead you to deduce that there are two walls and that the building owner can demolished the one on his side, leaving the adjoining owners wall intact. However I do urge you to check your deductions thoroughly to establish that there really are two separate and independent walls, each of adequate thickness, before telling the demolition contractor to bash on. Unless you do, you will risk laying open the adjoining owners building, which is a surprise we all wish to avoid.

thicknesses of walls, both party and external, have since time immemorial, or at least in London since the 1667 Act, and elsewhere since local Acts and By-laws laid it down, been determined by the height and length of the wall and the class of building they enclosed. This meant that if the Building Owner wished to add storeys to the top of his building, or take it down and replace it by a more lofty building, he needed not only to raise on the wall, but also to thicken it to bring it out to the thickness prescribed in the Act or the By-laws for the new height. He could of course exercise his right to take it all down and rebuild it to the new height and required thickness, but this would involve laying open and shoring the adjoining building, and no doubt paying substantial compensation to all the adjoining owners and occupiers, so was to be avoided if at all possible.

If he thickened and raised the wall, he would do this by adding a skin of new brickwork, which would inevitably be of different bricks and a different mortar to the existing party wall and so would look to his successors in title and their advisers like another wall built against the existing wall. Thickening is seldom well bonded or tied to the existing wall, but it does follow the wall in and out so there may not be a vertical plane between it and the wall.

The reason for advising this extreme caution is that

At the top of the old wall, the raising may not be on the whole width of the old wall, leaving a step in the wall thickness on the external side which can be mistaken for a parapet, and may even have a brick on edge and tile creasing to support the illusion, for it really is, or was, a parapet, but not of the whole width of the thickened wall.

10 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

At the front and rear, it is not uncommon to quoin up the end of the adjoining building and build the new external walls up to that line, forming a straight joint which may or may not be on the line of junction, and incidentally completing the illusion that there are two walls.

These operations can and have to my knowledge and in my experience resulted in the situation illustrated on the opposite sketch. Now imagine the implications if the owner on the right deduces that he has his own independent wall and starts to demolish it. The demolition contractor is hopefully surprised and stops before he does real damage and shares his surprise with the building owner’s advisers, work stops, re-design starts and the building owner’s lawyers start to load their blunderbusses with rusty nails to allege the liability of anyone standing in the way.

Party wall surveyors and their advisers need to be alert to this possibility so that they can ensure that sufficient survey and exploratory work is undertaken before demolition starts to convince everyone concerned that there really are two independent walls each of adequate thickness to enclose the two buildings.

I suggest that accurate dimensional surveys are undertaken of the face of the party wall in both buildings, on plan at all levels, and on section, to see if there is enough thickness for two walls. If these surveys leave doubts, the results of exploratory holes on the building owner’s side to discover the plane where the bricks or mortar change can be added to the surveys to reveal if there really are two walls or just one thickened, and hence what options are available to the building owner.

These actions are necessary if surprises are to be avoided and if the building owner cannot be persuaded to put them in hand, perhaps the reasons of time or expense, I venture to suggest that it is the appointed Surveyors’ duty to precipitate the situation by making a preliminary Award to force his hand.

But that is only an engineer’s view – what do Surveyors think?

Lawrance Hurst

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

I have discussed this weighty matter with an even older Codger. We have had quite a good response to the cri de coeur in the last issue, and a study of that response raises questions of itself.

Many of the questions require mini-articles as answers and dealing with these in the main journal would put severe demands on space. This is not really appropriate under a general heading. I have asked your Chairman to consider alternating Whispers and a Q and A publication, but the frequency of both would depend entirely on members’ input, not mine.

Predictably, there is a pattern among the questions, and

there are obviously matters which give almost regular cause for debate. It was ever thus, and these will be covered by a series of articles in future issues. For this issue, we have confined this section to the comments above, and to a few questions that can be answered briefly.

I regret to say that too many questions that are raised at meetings, and in writing, refer to fees. Whilst the end object of practice is to earn a crust, I have always considered the pre-occupation with fees to be unhealthy, and possibly damaging to the public’s conception of Party Wall Surveyors. If we do our jobs properly, we will be adequately remunerated. The odd bad debt, or charity case, should not stand in the way of a proper professional service, and dare I say it, duty.

Q1 What happens when the [sole individual] Building Owner [BO] dies after the publication of the Award and before the works subject of the Award are completed?

AWhere there is a change of BO, then for obvious reasons, the BO named in the Award is not capable of carrying out the obligations of the Award. Properly a new notice must be served and matters must proceed as from there; although there might be a nice legal argument that executors ARE the deceased for the purposes of such matters.

However regardless of the niceties, it is usually in the best interests of the Adjoining Owner [AO] for matters to be completed as quickly as possible and thus if the AO is satisfied as to the ability and willingness of the executors / estate to complete the works and wind up the matters covered by the Award then the surveyors could be instructed to facilitate this by an exchange of letters or a supplementary Award. If the estate are unable or unwilling to complete then the AO should be able to proceed against them under the terms of the Award for any matters affecting the AO.

Q2 Is an occupier with a licence of one year length an “owner”, (the licence stating that it does not create the relationship of landlord and tenant)?

ASection 20 defines owner very clearly and should be read with the circumstances in mind. A licensee for a year is not in receipt of the profits, rents etc. clause (a), not a purchaser under a contract or agreement (c) but is specifically excluded in clause (b) which says “a person in possession of land, OTHERWISE than as a mortgagee or as a tenant from year to year or for a lesser term or as a tenant at will”. A licensee is possibly an even lesser mortal than these excluded types. It is not thought that the rider set out in the question is necessary to exclude the licensee from the Act but it helps to underline the matter.

11 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Q3

There is a pre building contract archaeological dig on a site under the powers in the relevant Act and the excavation is or is likely to be within three metres of and / or below the level of the foundations of the adjoining building. The AO instructs a surveyor but the archaeology team say they cannot wait for the time limits etc of the Act. What is the AO and his surveyor to do?

AThink hard is the short answer. This is a trap situation and applies equally to a utility company digging trenches for pipes or sewers. Before the Act applies you must have [Section 6(1)(a)] a building owner [who] proposes to excavate. The archaeology team are not building owners; and in fact the owner of the site is probably very undesirous of the dig in the first place.

The owner of the adjoining property must take such action as is possible under the statute covering the Dig or in common law. To protect his client, a competent surveyor should be able to persuade the diggers to agree

to a schedule of condition and some ground rules for their operations.

The trap of not first thinking out the basics of this situation is one that Old Codger [not to be confused with Codger who is the editor of this worthy tome] fell into head first at an early Club meeting in Cambridge. After a lengthy and irrelevant discussion the said Old Codger had a very red face when someone pointed out the simple truth – the diggers [in that case, cable layers] are no owners.

Q4 Is a long-term tenant in a block of flats whose tenancy is up to the internal face of the external walls an “owner” under the Act and hence is formal notice required?

AThe lands of the respective owners do not adjoin as they are separated by the lessors half of the party wall. The tenant is not an Adjoining owner and is not entitled to notice under the Act.

12 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Save the date Announcing

for the second National Conference of Where The Assembly Room, The Exchange Building, Birmingham City Centre

13 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society 13 The Pyramus Thisbe Society

50

Years with Party Walls

14 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

David Moon FPTS(Ret)

THIS ARTICLE IS BASED ON TALKS GIVEN to the Thames Valley and Wessex branches of the P&T Society in November and December 2023, respectively. In what follows, you will be led through fifty years (almost) of hazy recollections of party walls leaned against, boundaries imagined or real and excavations climbed down or fallen into. In the interests of self-preservation, some locations and persons’ identities have been obscured. Other inaccuracies are due to failing memory.

My introduction to party walls came in 1974, coincidentally the year in which the Pyramus & Thisbe Club was proposed by John Anstey at the suggestion (as he put it) of his “incompetent and incomparable assistants” who thought it might be fun. I was then a junior civil servant in the Ministry of Public Building and Works. Having studied at the Polytechnic in Leicester, my knowledge of party wall matters as they were managed in London, was the essence of vague. I was given a copy of the London Building Acts (Amendment) Act 1939 and propelled towards Whitehall to act for H.M.Government as adjoining owner’s surveyor.

I was fortunate to meet, as building owner’s surveyor, Bernard Goodenough, sadly, no longer with us. In 1974, he was a partner in Goodman Mann Associates, practising from offices in St. James’s. What he thought of the longhaired youth from the Ministry, I cannot imagine.

What he did though, was to explain the mechanics of the Act, stand me a very decent lunch and leave me with the impression that party wall matters were a most gentlemanly pursuit and something that I should aspire to.

It sometimes surprises me to recall that about half of my career was spent while the 1939 Act was in force. It does not come as a surprise how few of the cases spring readily to mind. In fairness, I did less party wall work in those days. First with the Ministry (later Property Services Agency) and from 1978, in private practice with Davis & Co., most of my work was contract administration, project management, dilapidations and a sprinkling of structural surveys. However, a couple of party wall matters remain in sharp focus.

In (I think it was) 1987, I acted for an adjoining owner whose property in Hampstead Road was managed by the firm. It was a butcher’s shop with accommodation above and was a remnant with two other houses, of a wardamaged terrace. The vacant adjacent site was to be redeveloped. The building owner appointed a surveyor with whom I have worked on many occasions since. It was agreed the BO could open trial pits to establish the depth of the party wall’s foundations. It was further agreed that the pits be covered to prevent them flooding, it being early in the year during a prolonged wet spell of weather.

On a day in March, about lunchtime, the party wall failed, sliding into the excavations, collapsing the building

and seriously damaging the next adjoining property in the process. Unknown to the surveyors, the labourer charged with digging the trial pits had joined them all together forming a trench and had dug enthusiastically beyond the bottom of the foundations. By great good fortune, the butcher and his wife were out at the time but sadly, their cat was not and did not have a tenth life to rely on. The Fire brigade found an abandoned wheelbarrow and donkey jacket and fearing the worst, began to search for the missing labourer. An eye witness however, reported seeing a person fitting the description, running at speed away from the building shortly before the collapse. He was never found and the developer fled abroad. There were no casualties aside from the cat and all was eventually settled by insurance.

In 1990, I took over a case from a colleague who had retired. He was one of the original recipients of John Anstey’s invitation to form a party wall surveyors’ club and was a highly regarded party wall practitioner. The matter related to a development of housing by the borough council adjoining an existing terrace of houses in Haringey. I assumed duties in his place, as adjoining owner’s surveyor. The borough architect acted as building owner’s surveyor.

The AO alleged that damage had occurred to his property. The claim was disputed. On checking the award made by the original surveyors, they had not selected a third surveyor but had reserved selection to the President of the RICS. This was not unusual. The 1939 Act, unlike the present legislation did not contain the word ‘forthwith’ in the obligation to select a third surveyor. Timing was left to the discretion of the appointed surveyors and the means. We duly applied to the President (and paid the RICS

15 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Women of World War II monument, Whitehall

fee) and John Anstey was selected.

The necessary preliminary correspondence followed. It was then that our newly selected third surveyor wrote a short (testy) note to say that he had misled himself into believing that our matter was one to which the 1939 Act applied. He was not alone. We had all shared that belief and we were all mistaken. Haringey was not within the boundaries of the old LCC which defined the reach of the Act. It was an embarrassing discovery but all was not lost. The parties consented to Mr. Anstey being appointed arbitrator and on we went.

It was a very rainy day when the ‘tribunal’ met to examine the alleged damage. I arrived early to brief the AO about the visit. At the appointed hour, I opened the front door but found no sign of our arbitrator on the doorstep nor of the BO’s surveyor. I tried again a quarter of an hour later with the same result. After waiting a little longer I decided to venture out into the downpour for a more thorough search. I found them outside the BO’s property without shelter, the rain draining from the brim of Mr. Anstey’s fedora in cascades. Oh dear! It seemed ill-advised to point out that we had agreed to meet at the AO’s house. In spite of this inauspicious start, John Anstey’s award when it came, was scrupulously fair and well-considered and entirely in favour of my appointing owner who promptly invited me to his daughter’s wedding. This was the first but not the last time I was privileged to work with John Anstey. In 1997, the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 came into effect across the whole of England and Wales. With the demise of the GLC in London, it was realised that new legislation was required to preserve the party wall dispute procedures in London and the opportunity was taken to apply them to the country as a whole. The new Act largely mirrored the old one. Some old gaps were plugged but inexpert drafting left us with the troublesome definition of ‘special foundations’ and without a strong enough definition of ‘surveyor’.

Looking back, life under the old regime was very different and becomes increasingly so with the passage of time. The number of practising surveyors was small then and the community well-known to one another. It was suggested to me recently that the reason the new Act’s definition of ‘surveyor’ remained loose was out of concern that there would not be enough qualified surveyors to go round. There were fewer referrals to third surveyors who incidentally, were required to make their award within ten days of a referral being made under s.55(j). Appeals were also less frequent and the 1939 Act contained provisions under ss.55(n) and (o) for appeals to be heard in the High Court instead of the county court at the election of the parties, subject to certain undertakings being given.The 1939 Act gave no authority to the surveyors to settle

a dispute over security for expenses. Under s.57, this was a matter for a judge of the county court.

Awards of that vintage were different in style, often typed on foolscap size paper (with carbon copies) and with fewer reference documents. A full set of construction issue architectural and engineering drawings appended to an award was unheard of. Drawings were usually prepared specific to the subject matter of the award and the party wall would be coloured pink. Ah, the good old days when your office junior could be kept occupied with a set of water colours and a paintbrush! There were no method statements, they having not yet been conceived by health and safety officers. The award itself contained any necessary stipulations about the method of working. Fees were frequently expressed in guineas.

In the background, people in general were more law abiding in attitude and there was greater public awareness of what constituted good behaviour.

The 1996 Act brought immediate changes by extending the rights and obligations established in London, to the rest of England and Wales. Other changes, not least to social outlooks, have been more gradual but no less influential. Today, the circumstances in which surveyors operate under the legislation are quite different. There are many more referrals to third surveyors (who thankfully no longer have to determine the dispute within two weeks) and more appeals to the county court. Lawyers are more involved in the process both before and after awards have been made. They also write most of the authorities on the subject. The public is less instinctively law abiding and less risk averse when weighing up the pros and cons of compliance with laws that carry relatively modest sanction. The practising party wall surveyor now works in an altogether more hostile environment.

Working with the current legislation has brought moments of joy, horror and puzzlement in broadly equal measure. There follow some case summaries where those emotions were enjoyed to the full.

Colebrook Cottage, a home for a time of the essayist Charles Lamb, stands at the end of Duncan Terrace on (a now enclosed section) of the New River, a canal built in 1613 to carry water from Hertfordshire into the centre of London.

It adjoined a development site in Colebrook Row where I was acting for the building owner. The cottage had an enclosed garden with a pond in the centre of which was an island on which stood a life-size bronze crane (Japanese bird, not Scotch derrick). I don’t remember why the garden was so crowded on that cold December day but it was; filled with surveyors, architects, engineers and builders. Stepping back to allow someone to pass, I lost my footing and in the finest

16 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

John Anstey

cartoon fashion, fell backwards into the pond. As I surfaced, I heard the concerned housekeeper ask, “Has he damaged the sculpture?”

By contrast, on a very warm day several years later, I met a young surveyor standing in for his principal, the adjoining owner’s surveyor, to prepare a schedule of condition with me. The address in St. John’s Wood was one referred to by the ‘red top’ newspapers as ‘Millionaires’ Row’. The houses were (and are) very large and a bit bling and this was the blingest of all. A Rolls Royce with customised paintwork and trim loitered on the drive. We were ushered in by the housekeeper. We noticed the windows were all open. My companion expressed surprise as the house clearly had air conditioning. It was broken. We suggested it would be prudent nonetheless to close the windows when the demolition began. “What”, asked the housekeeper, “about the mink”. Both surveyors had the same thought, “put it in the wardrobe”. But “no” said the housekeeper making a sweeping gesture with her arm and repeating “the mink, the mink”. It seemed that all of the furniture in the reception rooms, including the sofa on which we sat, was covered in white mink fur.

Jet grouting is a relatively modern construction technique. My first brush with it was a development in Knightsbridge on a constricted site where deep excavations were to be dug to form multiple basements for an ‘iceberg’ building. There were many adjoining properties and no less than thirteen adjoining owners’ surveyors. Happily they all instructed Lawrance Hurst as their advising engineer whose advice proved invaluable to all. There was a debate about whether jet grouting was notifiable work and whether it

would lead inevitably to trespass onto the lands of adjoining owners. I believe we treated it as notifiable being part and parcel of the excavation work, its purpose being to stabilise the ground instead of piling in one form or another which the site conditions made impossible.

The method used was a cementitious form, pumped into the ground under pressure. It went pretty well with only two unhappy moments. An AO’s basement kitchen wall was breached and the grout filled voids beneath his kitchen cupboards necessitating a whole new fitted kitchen. More spectacularly, a titled lady called one day to report a concrete fountain in her garden! She was surprisingly calm and matter of fact about what was likely to have been a unique experience for her, as it was for me.

There are sometimes surprising, unforeseen aspects to a party wall matter. One such was at a very smart house near Hyde Park. It has always been a bad habit of mine to be distracted easily by paintings, sculptures or books during visits to prepare schedules of condition. On this occasion, as I mounted the stairs, I felt more and more strongly that I had seen some of these pictures before. Sure enough there were Picassos, a Piet Mondrian or two and the odd Matisse, among many others. Yes, they were all original works and most of them clung precariously to the party wall. They were insured for an eye-watering sum greater than the GDP of a small country. They could not stay where they were bearing in mind the scale of the neighbour’s proposed works.

A small bookshelf falling off a party wall in Notting Hill recently had created months of correspondence. Can you imagine the fall-out from a Picasso bouncing off a tiled

17 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Colebrook Cottage

London Building Acts (Amendment) Act, 1939

Does it involve the removal (excavation) of soil? In my opinion it is notifiable. It is immaterial whether of itself it removes soil from the ground.

floor at the stair foot three floors below?

It is surprisingly complicated to relocate world heritage class artworks to a place of safety. There are ‘before and after’ condition reports prepared by experts approved by insurers, then specialist removers arrive to pack and crate up. It all takes a lot of time and is hugely expensive. But, so far, so good; until that is the adjoining owner asked innocently what did she have to look at and enjoy while her art collection was away from home? A fair point. We thought of photographic copies, some inexpensive alternative pictures, hiring some paintings from a specialist agency etc.,etc. in the end it was the AO herself who found a perfect nil cost solution. She approached a gallery which exhibited young, up and coming artists and agreed to offer her own house as an extension of the gallery and to invite art-loving friends to view and buy the pictures.

Sheet piling; two words that have the power to wake up the most torpid of party wall surveyors. There has long been discussion over whether this form of construction is notifiable work under the Act. Does it involve the removal (excavation) of soil? In my opinion it is notifiable. It is immaterial whether of itself it removes soil from the ground. It is invariably linked to excavation work and is an essential part of the excavation process where specified. I discovered quite early in my career that bashing this stuff into the ground was a cast-iron guarantee that adjoining properties will be damaged. Alternative insertion methods such as the Giken system are preferable where the pile

sections are pressed into the ground. This however is not without risk.

Several years ago, close by Regent’s Park, I was acting for an adjoining owner who was remodelling his own very large, Grade II listed property. The BO was building two large houses on the adjacent site of one he had demolished. There were multiple basement levels which entailed digging one of the largest holes in the ground I have seen. There was to be sheet piling. My advising engineer, Derek Glenister was very clear. He didn’t like it. He especially didn’t like the jet watering of the pile toe to ease its passage into the ground. Derek explained that in clay soils, the water jetted under pressure risked opening natural fissures in the clay which would cause a rapid expansion in the soil. All of this was explained very patiently to the BO’s project manager, architect, engineer and contractor. It was agreed with the BO’s surveyor and awarded that the water jetting would be omitted; the piles would be pressed into the ground ‘dry’.

One morning, soon after the piling work had started, routine observation of monitoring targets on the AO’s property showed that on one corner, the building had lifted by 20mm. Damage was instantaneous and severe. Of course, the contractor, finding dry insertion difficult, resorted to jetting the pile toe. The predicted fissure in the clay soil opened into a cavity pushing the soil upward with force. It took years and several awards to settle compensation for the damage.

18 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

While a number of recent decisions in the courts have served to curtail the authority of surveyors, in some quarters it remains beyond question. I was in rather a hurry when I took the call from an adjoining owner, a lady of middle years, residing in one of north-west London’s leafiest and most exclusive suburbs. In fairness, she had suffered much at the hands of two very large developments backing on to her garden.

“They are eating their lunch on my roof. Are they allowed to do that?”

“No C they are not. They are trespassing and you can ask them to leave.”

“Do I have to be polite to them?”

“No.”

Sound of footsteps and window being opened.

“I have my party wall surveyor on the the telephone and he says I can tell you to **** off, so get off my roof!”

My talk for Thames Valley was entitled ‘Anecdotes of a third surveyor’. At some point, I don’t recall when exactly, I began to receive referrals as third surveyor. During the last few months before retirement, I believe I had in the order of twenty cases waiting for my attention. Some were simple, others quite complex and a good number were resolved by informal means.

One of the cases referenced in my talk to Thames Valley branch was an unusual damage claim. The owners lived in substantial adjoining detached houses on a steeply sloping site in Cricklewood. They did not get on. The downhill owner built a 30 metre long extension into the garden on piled foundations. The AO claimed that their garden flooded because the neighbour’s new building dammed surface water that previously drained away. The referrals included some complex legal arguments on trespass, nuisance and easements compiled by lawyers long since instructed by both parties. When in due course there was a lull in the crossfire, I came to consider my award. I decided that I could not give detailed consideration to the legal arguments on extraneous matters. I was not expert in these areas of law and in my view, s.10 of the Act did not require that I should be so. The tribunal formed under s.10 determines a dispute strictly within the confines of the Act. The questions to be considered were therefore;

• Was there loss or damage?

• Was the loss caused by work carried out by the BO?

• Was the work notifiable under the Act.

• Was s.7(2) of the Act in play?

These were the core considerations when making my award which was in favour of the AO’s claim. My award was appealed and as so often happens, I never heard the final outcome.

The immunity of surveyors appointed or selected under

the Act has long been a hot topic. As the discussions swung back and forth, I don’t suppose anyone was thinking about the surveyors suing one another. In 2020 I was selected as third surveyor and unusually, was asked to confirm my willingness to act (and to undertake a conflict of interest check). The case involved minor domestic scale work in north London. In due course, I was asked to make an award by the BO’s surveyor. Immediately afterwards the parties advised that they had settled matters between themselves. No further action was required. However, the BO’s surveyor wanted an award for his fee. I was slow to consider this referral not least because I had doubts whether an award was appropriate. I was served with a notice under s.10(9) to act effectively within ten days. The notice was served on Christmas Eve and my office had closed for the holidays the day before. I did not see the s.10(9) notice until we reopened the office in January by which time the notice period had run. I was no longer the third surveyor.

No amount of explanation, quoting of the Act or reasoned argument succeeded in loosening this man’s grip on his flawed understanding of the rules. His email had been no more than ‘a shot across my bows’. I was still in his mind, the third surveyor. He then threatened to sue me for his fee if I failed to make an award.

In short, that is what he did. He brought a claim in the county court against me for breach of contract. The case was heard in June 2022 and the claim was dismissed. The only surprise in all of this was that any practitioner could imagine that a contract existed between the surveyors. Impartiality, independence?

I ended my talk to Wessex branch with a short quotation, “But be of good cheer…..” words spoken by Hugh Latimer to his friend and fellow Protestant cleric, Nicholas Ridley. Admittedly, their circumstances were even more trying than those of a party wall surveyor managing a difficult owner with a difficult project. Waiting for Queen Mary’s inquisitors to finish piling bundles of twigs at your feet with blazing torches at the ready must have tested their patience even more than an email from one of the profession’s ‘bad boys’ rejecting a request for special foundations consent.

In closing, I send my warmest good wishes to all of my friends and associates in the party wall world and I leave you with some ‘pig Latin’ from my schooldays; nil carborundum illigitimi.

19 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

davidcharlesmoon@me.com

Letter to the editors

20 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Our Ref: AJC/P&T 19 February 2024

Whispers Editorial Team

The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

By email only

One George Yard

London EC3V 9DF 020 7936 3668

info@delvapatmanredler.co.uk www.delvapatmanredler.co.uk

Dear Editorial Team

Is the Party Wall Act optional?

A response to Matthew Hearsum’s article and presentation

We five are writing jointly to express our concerns about aspects and potential implications of Matthew Hearsum’s recent article, ‘Is the Party Wall Act optional?’, published in Estates Gazette (4 November 2023) and his subsequent talks on the subject to P&T members at branch events in London (16 January 2024) and Sussex (6 February 2024).

The sharing of opinions is the lifeblood of the Society, so we appreciate all members who give their time and share their knowledge, particularly in complex areas of legal, surveying or engineering practice that intersect with party wall practice. We are therefore grateful to Matthew for highlighting this area of law, which will impact on surveyors and property owners.

However, we are concerned that Matthew does not make clear various uncertainties in the law or highlight many of the potential pitfalls facing an owner who decides to rely on common law rights rather than comply with the Act’s procedures. We believe this may cause members, and the property owners they advise, to misunderstand the uncertainties and risks, thereby leading to costly disputes. Some property owners, perhaps facilitated by some surveyors, are all too easily attracted to circumventing the Act. We fear the tabloid -style tagline may embolden them, resulting in more widespread disputes among property owners.

We would like to see Matthew address the perceived shortcomings we have highlighted in this email (upon which we expand below) before the Society publishes any article by him in Whispers. We also ask the Society to invite another respected solicitor or barrister to provide a talk or article on the subject as soon as practicable to address these uncertainties and, where appropriate, to rebut some of Matthew’s points. This would ensure members are provided with a fuller and more balanced understanding of the issues.

We understand that a seminar may be in the offing from His Honour Judge Bailey and Victoria Woolf of Osborne Clarke, which we certainly welcome We hope the Society will do what it can to encourage and expedite this and to disseminate a recording or transcript of the event to all members as soon as possible thereafter

The shortcomings

Briefly, the shortcomings we have identified in Matthew’s article and slides include the following:

1. A change in the law

Matthew asserts that Power and another v Shah [2023] EWCA Civ 239 has changed the law and developers can now build on or excavate their land or undertake certain types of work on party walls without following the Act. We believe that to be incorrect for two reasons.

Also at:

Delva Patman Redler

The Quay

12 Princes Parade

Delva Patman Redler

40 Berkeley Square

Bristol

Liverpool L3 1BG BS8 1HP

Delva Patman Redler LLP. Registered in England & Wales OC335699. A list of members can be inspected at our Registered Office above.

21 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

19 February 2024

First, the remarks by Lewison LJ at paragraphs 73 and 102 of his supporting judgment were obiter dictum and therefore lack the force of precedent. Secondly, Lewison LJ is only repeating what other judges have said previously. For example:

• In Louis v Sadiq [1997] in the Court of Appeal, Evans LJ said, “The adjoining owner’s common law rights are supplanted when the statute is invoked”

• In Kaye v Lawrence [2010] in the High Court, Ramsey J said [paragraph 59]: “when the provisions of the relevant Act are operated, the common law rights are “supplanted” or “substituted” by the rights under the Act in relation to matters dealt with under the Act”; and [paragraph 62] “the building owner is exercising rights under the 1996 Act when he acts as such”

• In Group One Investments Ltd v Keane [2018] in the Court of Appeal, Hickinbottom LJ said [paragraph 2]: “the purpose of the 1996 Act being to provide a simple and relatively inexpensive statutory dispute resolution mechanism, which, when the provisions of the Act are operated, supplants the respectiv e common law rights and replaces them with rights under the Act… If for any reason the statutory procedure is not followed, then the parties’ respective common law rights and obligations continue to apply.”

Matthew may be correct that common law rights are only supplanted by the rights under the Act once notice has been served – which hopefully can be clarified soon – but this cannot be said to be new law.

2. Obligation to serve notice

Even if a property owner is exercising their common law rights to undertake work, if they are proposing to carry out work of a type listed in sections 1, 2 or 6 of the Act, the Act says they “shall” serve notice on any adjoining owner.

Matthew does not explain how a property owner may lawfully circumvent the requirement to s erve notice. His slides suggest it is because a developer who is not exercising rights under the 1996 Act, but rights at common law, is not a ‘building owner’ and the obligations do not apply. But in Heathcote v Doal [2017] in Birmingham County Court, the judge awarded an injunction and costs against a property owner who was excavating their own land without a valid notice.

We are therefore concerned Matthew’s conclusion that “developers may therefore choose to undertake the excavations under their common law rights, or to use the procedure in the 1996 Act” could be incorrect and may put members at risk of giving potentially negligent advice.

3. Breach of statutory duty

The flip side of the previous point is whether the failure to serve notice under the Act of an intention to carry out work of a type listed in sections 1, 2 or 6 of the Act constitutes a breach of statutory duty and whether an adjoining owner has a remedy in damages. The case law on this does not seem clear. (See Crowley v Rushmoor Borough Council [2010] EWHC 2237 (TCC) and Hough v Annear (2007) 119 Con LR 57.)

We feel Matthew should have highlighted this uncertainty, so that members know to make owners who seek to rely on common law rights aware of this.

4. Other potential pitfalls

Matthew’s slides give two reasons for using the common law and five reasons for u sing the Act. They do not, and nor does his article, set out clearly any of other the potential pitfalls of relying on common law rights alone We believe they are extensive, including:

• Developer would be at greater risk of claims for nuisance, negligence, trespass, and wrongful interference of an easement or right.

• Lack of a surveyor tribunal would probably result in the lack of an agreed methodology for the works or schedule of condition. Consequently, the burden of proof as to causation of any damage would most likely fall on the developer rather than the adjoining owner. (Roadrunner Properties Limited v Dean [2003] EWCA Civ 1816)

Page 2 of 3

22 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

19 February 2024

• An award of common law damages against the developer for any resulting nuisance or trespass could include consequential losses in addition to direct losses. In Louis v Sadiq [1997], because of the delay to the adjoining owner of being able to sell their property due to damage and the lack of an award, the awarded damages included four years’ mortgage interest, extra building costs for their new house in Guadeloupe due to increased prices (which the court held were reasonably foreseeable and not too remote), and general damages.

• Possible invalidity of insurance policies and/or difficulty with funders for failing to comply with statutory requirements.

Conclusion

We believe this could become a contentious area for property owners and surveyors. Whilst it is right that Matthew Hearsum highlights this, we feel members should be made more aware of the counterarguments and potential pitfalls, so they are better equipped to advise property owners.

We hope Matthew will provide further clarity in due course; however, we ask the Society in the meantime to invite another learned member from the legal profession to share their opinions on the subject and address the points we have highlighted

Yours sincerely

Aidan Cosgrave, Ashley Patience, Rob French, Shirley Waldron and Conor Healy

Page 3 of 3

23 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

M ATTHEW HEARSUM ADDRESSES the impact of the recent Court of Appeal decision in Power and another v Shah, which challenges the consensus view on the availability of common law rights

24 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

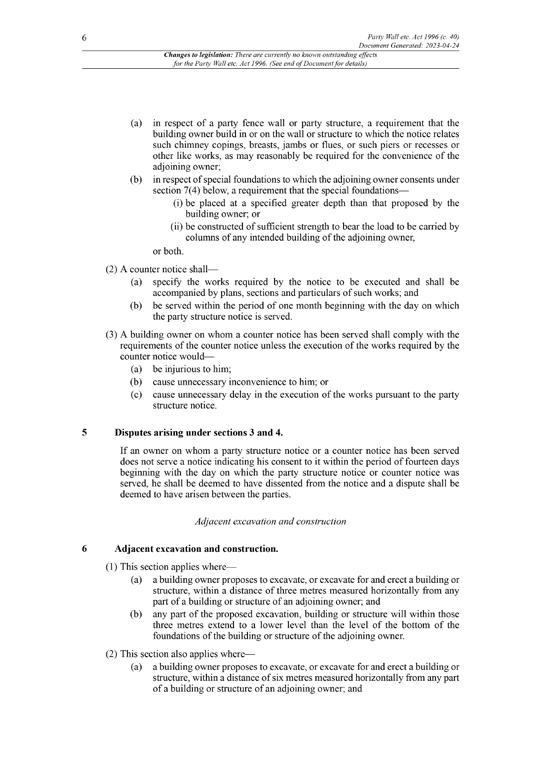

Is the Party Wall etc Act 1996 optional?

THE PREVIOUS CONSENSUS AMONG practitioners was that the rights and responsibilities set out in the Party Wall etc Act 1996 repealed and replaced the parties’ rights at common law. A developer who wanted to undertake works of a type listed in sections 1, 2 or 6 of the 1996 Act had to serve a notice under the relevant section and obtain either the adjoining owner’s consent to the works, or an award from a tribunal of surveyors.

A change in the law

In May 2023 the Court of Appeal handed down judgment in Power and another v Shah [2023] EWCA Civ 239. This decision principally concerned whether owners of adjoining land could rely on the dispute resolution provisions in section 10 of the 1996 Act if a building owner commenced works of the types listed in the Act without serving the relevant notice. The court held that the adjoining owner’s rights under the 1996 Act only arise after the building owner has served a notice. Unless and until a notice is served, adjoining owners have no rights under the 1996 Act, but may still bring claims in trespass or private nuisance. This principle is summarised in the slogan: “No notice, no Act.”

However, many are unaware that the decision in Power goes further; and developers also continue to enjoy all their rights at common law, including the right to undertake certain types of work listed in the 1996 Act without following its procedures.

This is at odds with the previous consensus among both surveying and legal professionals that the statutory rights in the 1996 Act operated as a wholesale replacement of the building owner’s rights at common law.

In the words of Lord Justice Lewison in Power: “So they

do, but only once the Act has been brought into operation.”

Until then, developers remain free to exercise their common law rights. Lewison explained that “it is the service of the party structure notice that causes the substitution of rights under the Act for common law rights”.

Works to an existing party structure

The rights to undertake works to an existing party structure at common law depend on what type of party structure it is. A detailed analysis of all the diverse types of party structures is beyond the scope of this article.

Broadly speaking, the two most common types of party structure are:

A structure divided into two moieties, each belonging to the adjoining property, but with right or user and support over the other moiety; and

A structure which belongs wholly to one owner but is subject to a right in favour of an adjoining owner to use the structure as a division between two buildings (or parts of buildings) on different land.

For type (a) party structures, at common law each owner may do what they like with their moiety, provided (1) they take reasonable care and (2) do not interfere with the easements of user and support in favour of the other moiety. This would include, for example, undertaking repairs to the party structure, or cutting into their moiety up to, but not across, the boundary line to insert a steel beam on a padstone or spreader plate.

For type (b) party walls, the owner of the wall may do as they please with their structure, provided they take reasonable care and do not infringe the other owner’s right to use the structure as a division between two buildings or parts of buildings.

25 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Adjacent excavations

At common law, the starting point is that an owner of land may do as they wish with their land, including excavations within three or six metres of the boundary line, irrespective of the depth of those excavations, provided they do not interfere with any rights of support or cause damage to neighbouring land.

Developers may therefore choose to undertake the excavations under their common law rights, or to use the procedure in the 1996 Act.

Construction at or near the boundary

As with adjacent excavations, at common law an owner of land may (almost) do as they wish with their land. This includes the construction of a wall at or near the boundary with adjoining land.

However, unlike the statutory right in section 1 of the 1996 Act, the common law does not permit the projection of foundations beneath adjoining land. Nor are there rights of access to adjoining land similar to section 8 of the 1996 Act, or indeed at all, and so the building owner would face significant difficulties in pointing or rendering the new wall.

Conclusion

The complex interrelation of rights and responsibilities that building and adjoining owners enjoy at common law explains the need for the 1996 Act and its predecessors,

which provide a speedy and (mostly) cost-effective means of resolving disputes compared to legal proceedings.

The 1996 Act also includes rights that do not exist at common law – for example, the right to underpin a party structure in section 2(2)(a) of the 1996 Act – or rights that are more expansive than those at common law, such as the right to demolish and rebuild a party wall to a greater height under section 2(2)(e).

Where a developer has a choice to proceed under the 1996 Act or under their common law rights, taking specialist legal advice on their options would be a sound investment.

Matthew Hearsum is a partner in the property litigation team at JMW Solicitors

Previously published in the Estates Gazette on 4 November 2023

26 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

matthew.hearsum@jmw.co.uk

The Right to reply

Dear Editors,

The purpose of my article in the Estates Gazette (“EG”) was to provoke a debate about an aspect of the Power decision that I felt had been overlooked. That endeavour appears to have been successful.

However, the EG article is not a complete account. It was, by editorial necessity, limited to the points that could be expressed within the limit of the 750 words kindly made available to me in that edition of the EG. It would likely require around 3,000 or 4,000 words to address the issue fully, and answer some of the questions raised by others. If there is appetite among the readers for such an article, I would be willing to prepare it for the next edition.

Regards,

Matthew Hearsum

27 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

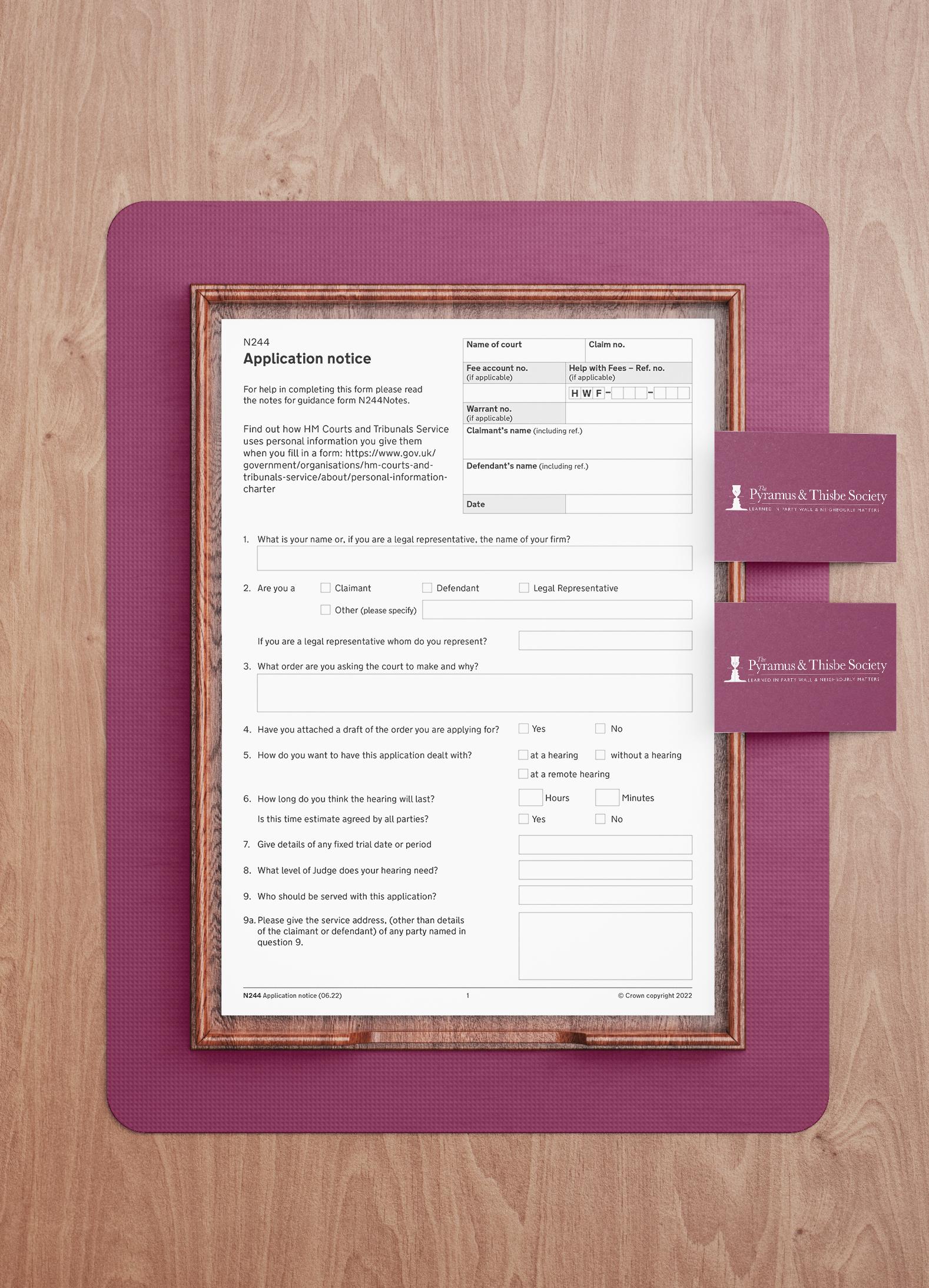

Is the Party Wall etc Act 1996 optional? The Society’s View

IMatthew Hearsum appears under the headline ‘Is the Party Wall etc. Act Optional?’. Originally published in The Estates Gazette, it is reproduced by permission of the author and original publisher. The views expressed in that article do not accord with those of the Society. In what follows, past and present members of the Society’s Management Board set out their answers to

The Publications Officer’s View

As the Society’s newsletter, Whispers has always accommodated a broad range of opinion among members. Debate is encouraged, always with the object of informing the readership and offering a platform for views to be expressed freely. It is in this spirit we asked for permission to reprint Mr. Hearsum’s EG article. In the same spirit, we encourage the

expression of contrary opinion. In this case, the central issue is one of the first importance to the profession. Unsurprisingly, there has been strong reaction to a proposition that the Act may be treated as an ‘opt in or opt out’ set of protocols. The Management Board believes it is important to state the position of the Society unequivocally. The collected views of the board members set out here, to which I add my full support, should offer reassurance to our membership that the Act is mandatory and owners must be advised accordingly.

The immediate past Honorary Secretary’s view

ANDREW SCHOFIELD

I think that Mr Hearsum has overlooked an important bit of the Act which is that the service of notices prior to the exercise of rights conferred by the Act is mandatory (see s1(2) and (5), 3(1) and 6(5)) “…..SHALL serve notice on any …..”.

28 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

Therefore, it follows that if a building owner doesn’t serve notice he is in breach of his statutory duty. That is why, if forced to apply for an injunction, the adjoining owner’s witness statement need only say that he believes that the works being undertaken fall within the rights conferred by the Act and that notice in respect of them has not been received. The important thing about this case is that it has confirmed the view held by most practitioners that if a building owner decides to ignore the legislation, he cannot rely on it later on.

The problem is not the Act, it is the law because the only form of enforcement by an adjoining owner is injunction which comes at a price and risk, albeit in my experience this is often exaggerated by lawyers and can be all but eliminated by careful adherence to the process. For most people, their property is a valuable asset and from time-totime steps have to be taken to protect it. These can range from painting and repairing the gutters to stopping a neighbour from doing something that might damage it. If they are not prepared to do this then why are they dissenting from works described in a notice? I’ll tell you why, because they are told by most surveyors (serving selfinterest) that they don’t have to pay for it.

I’m not for a minute saying that the Act wouldn’t benefit from more teeth but if it is given them, it must come at the cost of higher standards amongst practitioners and substantial improvements in the judicial system of enforcement.

The Education Officer’s View

STUART BIRRELL

I would add that it is always an option to ignore the law, for instance you can speed in your car providing you are prepared to accept the risk of points on your licence and a fine! Of course, with the no notice, no act ruling to not issue notice would automatically put the situation back into the common law. This would only give very limited rights to carry out works to a Party Wall, limited to repair of their own side of the wall and limited cutting in. All other conferred rights contained in the PWeA 1996 would not be available. The BO would have to accept the potential far reaching consequences. Whilst the Act doesn’t have teeth, Common Law certainly does.

The immediate past Membership Officer Relays a Point of View

DEREK

BATE

I recall Stuart Frame putting the suggestion forward (I used the word suggestion not opinion purposely) in a CPD meeting, that a BO might give notice if he was desirous of undertaking pursuant work and taking advantage of the

benefits of the Act (such as access). In other words, there was no penalty for not giving notice and continuing with pursuant works and so, if there’s no benefit, why bother.

The immediate past Treasurer’s View GRAHAM NORTH

I do not agree with Matthew Hearsum’s view. It seems to me that what he is suggesting is that a developer can either choose to follow the Act or not if he is exercising his common law rights. So, for example if he wants to dig a big hole on his land even if that big hole is within 3 or 6 metres of next door etc., he can choose to either serve Notice or not.

That cannot be correct.

The Chairman’s View FAREED F FETTO

The comments above remind me of the time when I was a student, visiting my aunt in Sheffield in my Mini -a real one! The very last leg of my journey presented me with a choice: bear left or right?

It caught me every time, so I was quite relieved to see two burly officers and their motorcycles at the junction. I stopped and asked them for directions. Having given them, the officer placed his hands on his hips, saying: “And don’t break the speed limit!”.

“Don’t break the speed limit” implies a choice, does it not?

Having a choice does not liberate me from the law, nor does it change the law.

No, my choices are ‘law-abiding’ or ‘outlaw’. Each choice has consequences.

Anyone who has driven in Beirut and survived deserves a five-star credit on their licence! And a mention in the Guinness book of records. And their name on the King’s honour list!

On one occasion, my father, followed a local car thereby inadvertently driving up a one-way street. Both he and the local driver were stopped by the police. My father explained that he was a stranger and that he simply followed the local driver without noticing that it was a one-way street.

The police fined the local driver, once for their misdemeanour and twice for my father’s!

Our Society is dedicated to the proper and lawful application of the Act, and to encourage others (including –especially- building owners) to do so.

While we welcome any contrary point of view, I hope you will agree that we, as a Learned Society must set and maintain the highest standard of best practice, by example, by good leadership and by the propagation of good advice. The alternative is unthinkable.

29 The Pyramus & Thisbe Society

“Is the Party Wall Act reall y optional?” Talk Given by: Edward Bailey, Howard Smith and Victoria Woolf Save the date 05.06.24