Dermatological Nursing Group

Dermatological Nursing Group

On behalf of the British Dermatological Nursing Group, I am pleased to introduce our first published Clinical Handbook. It will hopefully prove to be a useful read and quick reference guide to those who are new to dermatology and experienced clinicians alike.

This handbook is a practical guide to managing patients with common skin conditions. The information is predominantly based on the care that is delivered in primary care settings, although the content may be useful for those new to a secondary care dermatology setting.The focus is on practical advice with clinical pictures to assist in the management of common skin conditions.

As well as those who work exclusively with dermatology patients, it is hoped that this resource will also be useful for student nurses, practice nurses, community nurses and those nurses working in tissue viability. Although nurses are the main target audience, we also hope it will be useful for health care professionals for example pharmacists or physicians’ associates. Skin cancer is not covered by this handbook.

On behalf of the BDNG I would like to acknowledge the work of Rebecca Penzer-Hick (Former President of the BDNG) for all her assistance with this publication and her excellent writing skills. I would also like to express our sincere gratitude to Rob Mair and Lauren Nicolle for all their editorial support, and to Matthew Inman for the design. I would also like to thank our partners at DermNet NZ for their assistance with sourcing suitable images, and our team of reviewers for their positive input, we are extremely grateful.

Lisa McGovern President of the BDNG

Consultant Nurse

Dermatology

– Ashford & St. Peter’s NHS Foundation Trust Surrey

The British Dermatological Nursing Group would like to thank all our corporate sponsors for their support and continued investment with the BDNG

to thank all our corporate sponsors continued investment with the BDNG

The British Dermatological Nursing Group Corporate Sponsors

09/01/2025 16:52

The BDNG would like to thank all our corporate sponsors for their support and continued investment with the BDNG

DN Sponsors-2024.indd 1

09/01/2025 16:52

The BDNG would like to thank all our

This handbook is a practical guide to managing patients with common skin conditions. The information is predominantly based on the care that is delivered in primary care settings, although the content may be useful for those new to a secondary care dermatology setting. It does not cover information about skin cancer.

Prescribing information should always be viewed within the context of the individual patient, so that dosing and any contraindications can be accurately assessed.

The images used are for illustrative purposes only. For further cases please look at other resources including those listed below. Several key sources have been used to write this handbook and they can be accessed to find further information. This includes:

● Clinical Knowledge Summaries

● National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidelines

● Primary Care Dermatology Society

● Dermnet NZ

● British Association of Dermatologists

Patients with a skin condition need to be seen in an environment where there is a good light source and access to a magnifier is often very useful. Patients should be offered access to a chaperone, especially if intimate areas need to be examined. Make sure that on questioning, the full extent of the skin condition is ascertained, as the patient may be reluctant to tell you about flexural involvement or that genital skin is affected.

As dermatology is a visual specialty, using cameras to capture images is also a useful way of monitoring disease progression. Patients may like to do this using their own phones. If images are to be captured and stored in the patient record, the organisational policy around the capture, storage and use of images must be followed.

Once you have agreed a care plan, it is useful to provide this in writing for the patient or parent/guardian so that they can refer to it and optimise adherence to treatment. Sending an electronic version to the patient or parents/guardians may be a useful alternative for some.

Assessment tools are useful indicators of disease severity and impact on patients, but they should always be used in conjunction with an effective consultation. They can be particularly helpful in assessing whether a treatment has had a beneficial effect and are useful as indicators of severity when referring to secondary care.

There are a range of assessment tools which may be useful in practice either to assess quality of life or disease severity. The links below direct you to some relevant resources. Please note that for some of these, for example the Psoriasis Area Severity Index and the Eczema Area Severity Index, training should be undertaken to ensure they are used accurately. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMS) are completed by the patient, so training is not necessary, although it is important to know how to interpret the scores and use them effectively as part of the consultation process.

● Acne – Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI)

● Atopic eczema – Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM)

● Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI)

● Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

● Hidradenitis suppurativa – Hurley Staging

● Psoriasis - Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI)

Emollients are key treatments for dry skin conditions, and especially eczema. The best emollient is the one that the patient likes, will use and keeps their skin hydrated. Choosing an emollient should be based on patient preference to ensure it is used regularly and their skin is kept hydrated.

If you are new to the specialty, it is a good idea to be familiar with two or three emollients from each of the following categories, rather than trying to know all of them. As you become more experienced, your knowledge of different emollients will expand.

Companies are usually very happy to supply samples of emollients. These can be helpful for you to learn how emollients feel on the skin. If your organisation allows, supplying patients with samples before prescribing full size products can be a useful way of finding out what they will like and use.

Emollients with additional components in them can be particularly helpful, for example urea is anti-pruritic and products with urea in may help if someone is particularly itchy.

● Wash product/soap substitute: e.g. Dermol 500, Doublebase shower.

● Lotion: e.g. E45 lotion, Aveeno lotion.

● Cream: e.g. Cetraben, Epaderm.

● Cream with added urea: e.g. Balneum plus, Eucerin.

● Gel: e.g. Doublebase gel, Isomol gel.

● Ointment: e.g. Hydromol ointment, Epaderm ointment.

● Emolin spray.

Any product that contains paraffin (i.e. most topical creams and ointments) is a fire risk when it gets soaked into fabrics such as clothing and soft furnishing. Patients, particularly smokers, should therefore be advised to avoid naked flames.

Emollients should be applied to the skin using a stroking motion that follows the lie of the hair, this helps to avoid irritating the hair follicle and causing folliculitis. It is not unusual for people with dry skin conditions to use 500g of emollient in a week, so prescribing sufficient amounts is essential for treatment adherence. Transient stinging on application of an emollient is not uncommon. This will usually wear off, but if it persists it may be necessary to try an alternative emollient.

Emollients can make surfaces slippery, especially in the bathroom where there is water.

National organisations representing patients provide reliable patient information as do several professional organisations. Here are some good examples:

● Psoriasis - The Psoriasis Association

● Eczema - National Eczema Society

● British Association of Dermatologists

● The Primary Care Dermatology Society

● Eczema Outreach Support

Advise patients who pay for their prescriptions that buying a pre-payment certificate is likely to be cheaper than buying individual prescriptions. This is because they are likely to need more than one prescription on a regular, ongoing basis. For more information and to apply online click here

Acne is a common condition which affects most teenagers to some degree. It can continue into later years, and for women in particular, it can be a persistent problem.

Acne occurs when the duct leading to the sebaceous gland becomes blocked with overgrowth of skin cells leading to whiteheads (closed comedones) and blackheads (open comedones). This blockage can lead to the proliferation of the naturally occurring bacteria that live on the skin causing pustules, nodules and cysts. This is accompanied by significant inflammation.

Acne occurs in areas where there are high numbers of sebaceous glands i.e. the face, back, shoulders and torso. The scalp can sometimes be involved, too.

Lesions characteristic of mild acne are open and closed comedones (blackheads and whiteheads), while moderate acne typically presents with pustules. Severe acne is characterised by multiple pustules, nodules and cysts. Scarring is more likely to occur in moderate or severe disease.

More severe acne can be painful and sore, but all degrees of severity can lead to a significant impact on mental health and wellbeing.

Acne is relatively straight forward to diagnose, the key differential being rosacea. Rosacea presents with pustules on the face along with erythema, but there are no blackheads or whiteheads. Rosacea is also commonly associated with facial flushing and telangiectasia.

All patients should be advised of good skin care practices. This includes:

● Washing the face with a non-comodogenic/oil free cleanser daily.

● If a moisturiser is needed, a non-comodogenic/oil-free product should be used.

● Removing make up at the end of the day using a cleanser (as highlighted above).

● If sunscreen is needed, non-comodogenic/oil-free brands should be used.

● Try and avoid picking and squeezing spots as this can make them worse.

Acne severity: MILD

First line Alternative Practical tips

Fixed dose combined adapalene and benzoyl peroxide (e.g. Epiduo)

Topical tretinoin and topical clindamycin

OR

Topical benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin

OR if sensitive to retinoid, benzoyl peroxide as monotherapy

If irritant, build up contact time with Epiduo gradually or use on alternate days

Avoid exposure to sunlight as photosensitising

Benzoyl peroxide can bleach clothing and soft furnishings

Retinoid based products (e.g. Epiduo) are contraindicated in pregnancy

Duration of prescription

12 weeks then review

Acne severity: MODERATE

First line Alternative Practical tips

Fixed dose combined adapalene and benzoyl peroxide AND oral lymecycline 408mg once a day OR oral doxycycline 100mg once a day

Topical tretinoin AND topical clindamycin OR azelaic acid AND oral lymecycline 408mg once a day OR oral doxycycline 100mg once a day

Do not use oral and topical antibiotics together

Do not use oral antibiotics as monotherapy

Epiduo can be used as maintenance therapy once oral antibiotics have been discontinued

If the patient can’t take a tetracycline, consider replacing with trimethoprim or a macrolide (e.g. erythromycin)

Antibiotics (oral or topical) should only be continued beyond six months in exceptional circumstances

Duration of prescription

12 weeks then review

Acne severity: SEVERE

First line Alternative Practical tips

Fixed dose combined dapalene AND benzoyl peroxide AND oral lymecycline 408mg once a day OR oral doxycycline 100mg once a day

Topical tretinoin AND topical clindamycin OR azelaic acid AND oral lymecycline 408mg once a day OR

oral doxycycline 100mg once a day

Do not use oral and topical antibiotics together

Do not use oral antibiotics as monotherapy

Epiduo can be used as maintenance therapy once oral antibiotics have been discontinued

If the patient can’t take a tetracycline, consider replacing with trimethoprim or a macrolide (e.g. erythromycin)

Antibiotics (oral or topical) should only be continued beyond six months in exceptional circumstances

Duration of prescription

12 weeks but consider referral to a dermatologist at the same time as starting treatment

Someone with nodular-cystic acne should be referred immediately to a consultant-led team. Consideration for referral should be given to those who have had appropriate courses of treatment as outlined above (12 weeks of treatment).

For mild to moderate acne, this should be two completed courses of treatment and for moderate to severe, this should be a course containing an oral antibiotic. Those who are experiencing scarring or persistent pigmentary changes should also be considered for referral. If acne is causing significant psychological distress a patient should be considered for referral.

The usual reason for referral to secondary care is for consideration of treatment with isotretinoin. In order to ensure an effective referral, consider using the British Association of Dermatologists’ referral guidance.

Atopic eczema (also known as atopic dermatitis) is a chronic, inflammatory, itchy skin condition. Its aetiology is multifactorial with genetic, skin barrier dysfunction, immunological and environmental factors all playing a part.

It presents most frequently in childhood, with a high incidence of onset in the first 12 months. However, it can present in adults, usually as a continuation of childhood eczema. A personal or family history of atopic tendency (asthma, hay fever and atopic eczema) is common.

Whilst it is sometimes related to a specific allergy (e.g. a food), this is not common. Usually, atopic eczema is an episodic disease of flares and remission, although it may be continuous in severe cases.

Atopic eczema usually presents as dry, itchy, inflamed skin. In an acute flare, inflammation is more likely. Acute flares may be accompanied by small blisters/vesicles which are intensely itchy and exude clear fluid. Very dry skin may be accompanied by fissuring (especially on palms and soles). In skin of colour, a papular follicular presentation is more likely than in white skin.

Chronic atopic eczema tends to be less inflamed but still dry and itchy with increased prominence of skin lines (lichenification).

Because the skin is itchy, there are likely to be excoriations (scratch marks) in evidence.

When atopic eczema becomes bacterially infected, there is usually a significant increase in the inflammation alongside weeping and crusting with purulent fluid.

Eczema herpeticum (atopic eczema infected by the herpes virus) should be treated urgently as a red flag issue.

The location of atopic eczema tends to change throughout the life course.

Infantile Type

Face

Scalp

Trunk

Extensor surfaces of extremities

Childhood Type

Flexural folds of ext (antecubital, popliteal fossa) neck, ankles

Adult Type

Upper arms

Back Wrists

Hands

Fingers

Feet

Toes

Psoriasis

Fungal infection

Allergic contact dermatitis

Nummular dermatitis

Dermographism

Flat topped plaques with silvery scale, generally less itchy than atopic eczema, symmetrical and tends to affect extensor surfaces.

Area can be mildly scaly with a slightly raised border and central clearing. It is usually unilateral.

Eczematous rash at a site relating to a topical allergen. For example, a plaster, dressing or ring. Older adults have greater risk due to repeated allergen exposure and reduced skin barrier repair mechanisms.

Cause is unknown, unusual to present before five years old. Characterised by round or oval well-demarcated lesions that are acutely itchy.

Immunologic response to pressure applied to skin. Characterised by local wheal and flare erythema.

The multifactorial nature of atopic eczema means that providing good-quality general advice can be complex. The overall aim should be to guide the patient (and their family) towards sensible measures which are likely to have the most significant impact and steer them away from unsubstantiated recommendations that they might have read about in the newspaper or on social media. Obsessively trying to avoid one thing is rarely the solution.

● Avoiding irritants - For example soaps, perfumes, shower gels and leave-on products such as perfumed emollients.

● Keeping cool - Often heat will trigger atopic eczema, dry heat characterised by central heating is often the most problematic.

● Managing house dust mites and pet dander (skin and fur) - Pet dander can make atopic eczema worse. Frequent vacuuming, minimising soft furnishings, washing soft toys (or putting them in a bag in the freezer), and keeping pets out of the bedrooms can help to minimise this. If there is already a pet in the family, it is rarely worth advising that it should be rehomed as pet dander will stay in the house. However, if somebody within a household has atopic eczema, they should be advised to avoid getting furry pets.

● Minimising scratching - Scratching is a natural response to atopic eczema and whilst it makes the skin feel better in the short term, it can set up a vicious ‘itch-scratch cycle’. Scratching is habit forming and distraction is a good way of preventing scratching, particularly in children. Behaviour modification where scratching is replaced by another behaviour can be useful. Keeping fingernails short can help to minimise the damage caused to the skin by scratching.

● Avoid irritant fibres - People usually find that soft, breathable fibres next to the skin are most comfortable and that “scratchy” fibres such as wool are most irritating.

● Adherence to treatment - Atopic eczema needs a long-term treatment plan which the patient can adhere to. Regular and consistent application of topical treatments, especially emollients, are vital for keeping eczema under control.

● Do not rely on antihistamines - Unless an antihistamine is sedating and therefore helping someone sleep at night, they are rarely useful in atopic eczema.

The mainstay of atopic eczema treatment is the use of topical emollients. These are critical for maintaining skin hydration and helping to repair the skin barrier. They need to be used regularly and consistently for the best effect and, most importantly, the chosen emollient must be one the patient is willing and able to use.

As already mentioned, soap wash products (including shower gels) can act as irritants. They should be replaced by a soap substitute also known as a non-soap wash product. It is important not to over wash, and bathing or showering should occur no more than once a day.

Some examples of emollients are outlined in the table below.

Generic description Brand name example Comments

Useful if frequent skin infections are an issue due to the antimicrobial content.

Has more of a feel of a shower gel and may therefore increase adherence.

Cheaper option and may mean that the patient can use the same wash product and leave-on emollient, thereby reducing prescription costs.

Useful if the skin is very dry. Can be dissolved in hot water and added to a bath or wash water.

There are many different brands of leave-on emollient products to choose from, however, choice may be limited by what is available on a formulary.

It may be necessary to try more than one option before the patient finds one they like to use. Samples of emollients may be helpful in this selection process. Having a couple of options can also optimise adherence, for example, one for day-time use (e.g. a cream) and one for night-time use (e.g. an ointment).

The table below gives some examples of the different types of emollients. It is helpful to familiarise yourself with at least one or two from each category. Generic description Brand name example Comments Aveeno lotion

Consistency is thin due to high water content. Easy to apply but only useful when there is mild dryness.

White cream consistency which is thicker than lotion. Good for daytime use as it sinks in more quickly than an ointment. Good for moderate skin dryness.

Urea is a humectant ingredient which can help to manage itchy skin and/or thickened scaly skin.

Part way between a cream and an ointment; sinks into the skin easily. Good for moderate to severe dryness.

Ointments have a greasy consistency which take some time to sink into the skin, but are very good for severe dryness. It may be useful to use at night.

● Frequently so that the skin does not dry out (four or more times a day is not unusual).

● Prescribe sufficient quantities (250-500g per week is not unusual).

● Stroke into skin following lie of hair (to avoid folliculitis).

● Should not be mixed with topical steroids.

● Best to have a gap between application of steroids and emollients.

● Rarely, people are sensitive or allergic to pharmaceutical grade emollients.

● They can make the environment slippery.

● Greasy emollients particularly can irritate the hair follicle and cause folliculitis.

● When emollients are soaked into garments or soft furnishings, they become a potential fire hazard, so naked flames need to be avoided.

Steroid ointments and creams are the mainstay for the treatment of active atopic eczema. They must be used alongside emollients (see section on how to use treatments).

Topical steroids come in four potencies: mild, moderate, potent and very potent. As a rule, the potency should match the level of disease severity, the age of the patient and the location of application.

Generic description

Mild potency

Brand name example

Hydrocortisone

Moderate potency

Eumovate

Potent

Very potent

Elocon

Comments

Mainly used in babies and on delicate skin such as the face in children and around eyes in adults.

Generally used in mild disease.

Can be used on delicate skin in adults (face and flexures) and used on bodies of both children and adults.

Generally used in mild or moderate disease.

Should only be used on the body and is suitable for moderate to severe disease. Can be used in children over the age of two.

Generally only used in specialist services for severe disease. Never used on delicate skin such as the face and flexures.

May be used on palms and soles in less severe disease due to greater skin thickness.

This table illustrates some examples of topical steroids, ranging from mild to very potent

Dermovate (clobetasol proprionate)

Elocon (mometasone furoate)

Betnovate (betamethasone valerate)

Synalar (flucinalone acetonide)

Fucibet (betamenthasone and fucidic acid)

Diprosalic (betamethasone) diproprionate and salicylic acid)

Eumovate (clobetasone butyrate)

Fludroxycortide tape

Trimovate (clobetasone butyrate and oxytetracycline and neomycin)

Hydrocortisone 0.5%,1.0% & 2.5%

Fucidin H (hydrocortisone 1% and fucidic acid)

Calmurid HC (hydrocortisone 1% and urea and lactic acid)

Diprosone (betamethasone diproprionate)

Locoid (hydrocortisone butyrate)

Betnovate RD (betamethasone ¼ strength)

Synalar 1 in 4

and 1% hc)

Topical steroids should always be used alongside emollients (see page 26).

● The steroid potency selected should match the disease severity, the location on the body and age of the patient. Thinner skin (e.g. eyelids and flexures) needs milder topical steroids, while thicker skin (e.g. soles of feet and palms of hands) needs more potent steroids to be effective.

● Patient concern about topical steroids means they are often underutilised. A good guide is that an area of skin the same size as two palms needs one fingertip unit (approximately 0.5g) to cover it effectively.

A GOOD GUIDE IS THAT AN AREA OF SKIN THE SAME SIZE AS TWO PALMS NEEDS ONE FINGERTIP UNIT

● Using topical steroids once a day for 7-14 days is usually sufficient.

● Reducing frequency of use to alternate days for a further week may help to reduce the likelihood of a flare. This is particularly helpful if potent topical steroids have been used.

● If flares are common, once the skin is clear, consider reducing frequency down to twice weekly and only applying to areas that regularly flare. Review at 3-6 months.

● Generally, work down the steroid potency rather than up. In other words, use a potency of steroid that matches disease severity, rather than a mild one in the hope that it might work. It is better to use a product that will be effective and reduce the potency over time.

● Cream topical steroids may be more cosmetically acceptable; however, ointment topical steroids are better if the skin is very dry.

● Underutilisation of topical steroids means that there is a greater chance of itching and scratching which will lead to distress, excoriations, potential infection and/or lichenification.

● Overutilisation of topical steroids (especially potent ones) can lead to skin thinning and, in extreme cases, Cushing’s syndrome.

● As with emollients, if topical steroids soak into garments or soft furnishings, they are a potential fire hazard.

● Applying topical steroids under occlusion will increase their absorption and therefore their potency. Consider this particularly if using bandages for occlusion. Topical steroid withdrawal is a real concern for many patients and parents. Using topical steroids safely makes TSW unlikely. The National Eczema Society have some useful information you can share with those who are concerned. For more information Click here.

● Helping people to reduce scratching is always helpful for managing AE.

● Behavioural therapy aims to substitute scratching behaviour with an alternative activity. There is very useful information about habit reversal therapy here: Click here

● In children, distraction via play is a useful way of decreasing scratching behaviour.

● Bandaging can physically stop the damage caused by scratching, however, it is important to note wraps should not be used on infected eczema. Using tubular bandages over topical treatment can be helpful either as a single dry layer or as a double layer with the layer closest to the skin being made damp with warm water (known as wet wrapping). For more details on wet wrapping, please see this video from St John’s Institute of Dermatology. Click here

● Providing a written care plan for patients helps them to remember important information. There are several online resources which can help patients to document their symptoms. Patients can then share the documentation with you during a consultation.

● If topical steroids are needed as part of someone’s treatment, applying it just before bed is an effective way of managing itching at night.

Antibiotics should only be used if there are symptoms of infection, not just in response to eczema flares. Antibiotics should be prescribed, taking into account local resistance, particularly to topical antibiotics.

Symptoms

Eczema worsens rapidly

There is weeping, crusting and/or pustules

Patient may feel systemically unwell, sometimes with fever

Treatment

Flucloxacillin is first line choice

If allergic to penicillin or known resistance to flucloxacillin, prescribe clarithromycin

Localised, small infected areas may be treated with fucidic acid 2% for up to seven days

Otherwise known as eczema herpeticum, this is caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and is considered a red flag issue. Antivirals are needed.

Symptoms

Treatment

Initial lesions may be itchy or painful, appearing in groups which may join together

Lesions are often punctate

Fever and malaise may accompany

Can occur anywhere on the body but face and neck are more usual

Most commonly seen in infants and children

Start systemic antivirals immediately (aciclovir)

Discuss with the on-call dermatologist as it can, in rare circumstances, be fatal

If ocular area is affected, contact opthamologist for same day opinion

Patients should be referred if:

• Eczema herpeticum is suspected/diagnosed.

• Severe eczema has not responded to optimal treatment.

• The diagnosis is uncertain.

• Eczema is associated with severe and recurrent infections.

• High impact sites are affected (e.g. face and genitals).

Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) affects 1-3% of the population and is characterised by nodules and cysts which usually occur in the groin, axilla and submammary areas. HS is three times more likely occur in women than men and usually starts after puberty. Although exact causation is not yet understood, there is follicular occlusion and an abnormal skin microbiome. This is accompanied by a significant inflammatory response.

Early presentation is likely to involve double-headed open comedones (blackheads) and recurrent boils which can then progress into nodules. More severe disease is characterised by cysts and abscesses which can form tracts and sinuses. Whilst the condition can flare and remit, lesions heal with permanent scarring. HS is painful and is often accompanied by purulent exudate.

Diagnosis of HS is made clinically based on history and presentation. Early diagnosis is important, and HS should be considered as a diagnosis for someone experiencing recurrent boils in groins, axilla or submammary region.

● Individuals diagnosed with HS are likely to need psychological as well as physical support.

● There are several treatment options but no cure, and the symptoms of pain and exudate management will need significant nursing input.

● Monitoring of pain, mood, number and type of lesions along with the frequency of flaring are useful to ascertain treatment response. Periods of remission may be followed by flares and although the disease may eventually become inactive, it is likely that long term treatment and support will be needed.

● Supporting patients with lifestyle choices such as smoking cessation and/or weight loss may be helpful, but it is unlikely that these will be sufficient to manage the disease.

● It is important to work with patients to find dressings that conform to the skin, that absorb exudate and that do not use adhesives which can cause further irritation and damage (also known as medical adhesive skin injury, or MARSI). Securing dressings with garments specifically designed for HS (e.g. HidraWear) may be helpful.

First line

Antiseptic wash e.g. Octenisan AND

Topical clindamycin OR

Oral doxycycline (200mg once a day) OR

Oral lymecycline (408mg twice a day)

If insufficient or poor response

Second line

Antiseptic wash e.g. Octenisan AND

Oral rifampicin (300mg twice daily) AND

Oral clindamycin (300mg twice daily)

DurationComments

3 months

3 months

If good response after 3 months, have a treatment break.

Patients with severe disease should be referred to secondary care. Those with more moderate or mild disease should be considered for a referral if the above treatment regimens are not effective. If appropriate, referral to mental health services such talking therapies as should be considered.

The natural microbiome of the skin has a diverse range of commensal bacteria, fungi and viruses. These microbes are vital for skin health and when the skin is healthy, there is a harmonious balance which discourages the colonisation of the skin by pathogens. However, when this balance is disrupted and/or the barrier function of the skin is compromised, there is an increased risk of skin infections developing.

Good skin health practices are the best ways of preventing skin infection. In vulnerable populations, e.g. the elderly and those with compromised immune response, particular care should be taken to maintain skin integrity.

The most common bacterial skin infections include cellulitis, impetigo and folliculitis.

Unilateral erythema accomapanied by swelling

Well demarcated erythema

Cellulitis is a bacterial skin infection of the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissue, most commonly caused by streptococcus pyogenes or staphylococcus aureus. It manifests as localised inflammation accompanied by swelling, pain and systemic symptoms including pyrexia. It can progress into life-threatening conditions such as sepsis, so must be treated promptly.

Cellulitis most commonly occurs in limbs, with those who have compromised barrier function (e.g. through tinea pedis) at higher risk.

The most important differential is varicose eczema. Erysipelas has similar features to cellulitis but occurs in more superficial skin tissues such as the upper dermis. Erysipelas is almost exclusively caused by Group A beta haemolytic streptococci and is often seen on the face.

Onset

Inflammation

Gradual

Less well defined

Systemically unwell

Distribution

Not usually associated with being systemically unwell

Often bilateral

Relatively acute

Usually well-defined and may be advancing

Often associated with feeling unwell and pyrexia may feature

Skin surface Usually unilateral

Multiple changes including dryness and scale

Skin is tight due to swelling but skin surface generally unchanged

Cellulitis must be treated with either oral or intravenous antibiotics, depending on disease severity. Hospital admission may be needed for those with systemic symptoms.

For those who have repeated cellulitis episodes, prophylactic antibiotic treatment may be needed with low dose penicillin V or erythromycin. Any compression therapy should be discontinued during cellulitic episodes.

Characterised by its honey-coloured (yellowy) crust, impetigo is commonly seen in children with atopic eczema. It is also more commonly seen in those who are immunosuppressed and in environments where hygiene is poor.

Impetigo is usually caused by either staphylococcus aureus or streptococcus pyogenes and is a highly contagious superficial infection. Ecthyma is a deeper form of impetigo affecting the dermis.

Impetigo can be classed as non-bullous (most commonly seen) or bullous (see table below for differences). Impetigo usually heals without scarring and patients can be reassured that there are rarely serious sequalae.

Non-bullous impetigo Non-bullous impetigo

Most common location

Onset

Exudate

Tendency to spread

Erythema

Pain Systemic features

Non-bullous impetigo

Face, arms, legs

Single macule which develops into a pustule or vesicle

Honey-coloured crust develops when the pustule or vesicle ruptures

Can spread through autoinnoculation

Minimal erythema

Likely to be some mild itching

Generally none, but may be some lymphadenopathy

Bullous impetigo

Face, arms, legs, trunk, buttocks, perineal area

Superficial thin-roofed blister which ruptures to leave a scaley outer rim

Honey-coloured crust forms after the blisters burst

Can spread through autoinnoculation

Likely to be erythema

Lesions can be painful especially after blisters have burst

More likely to experience lymphadenopathy, fever and malaise

● Avoid socialising (stay off work or school) until the lesions are healed or until 48 hours after treatment has been started.

● As impetigo is highly contagious, attention should be given to good skin hygiene practices including frequent hand washing.

● Towels and wash cloths should not be shared, and bedding should be changed regularly and washed at a high temperature.

● Avoid touching the lesion and cover where possible to reduce likelihood of spreading to others.

The recommended treatment approaches are listed in the table below. However, practitioners must always consider the disease severity, the vulnerability of the individual and local conditions (e.g. specific issues related to local antibiotic resistance).

Non-bullous Bullous

Localised disease, no systemic symptoms

More widespread disease, no systemic symptoms

Antiseptics: hydrogen peroxide cream for 5-7 days

Topical antibiotics (if above not suitable): 5-7 days of fucidic acid 2%

OR

Mupirocin (if resistance to fucidic acid)

Topical antibiotics as above OR

5-7 days of oral flucloxacillin

OR

Clarithromycin or erythromycin (if flucloxacillin is contraindicated)

Straight to oral antibiotics

Straight to oral antibiotics

Widespread disease and/or systemic symptoms

Straight to oral antibiotics

Straight to oral antibiotics

Folliculitis describes an inflammation of the hair follicle; this can be an infective or noninfective process.

Folliculitis is characterised by erythema around the hair follicle and there is often an associated pustule. Folliculitis is usually self-limiting.

A boil (otherwise known as a furuncle) is significantly more pronounced and there is likely to be purulent matter associated with it. When several furuncles join, this is known as a carbuncle.

● Symptoms can often be resolved by modifying behaviours such as reducing the frequency and the closeness of shaving and/or using an electric razor.

● Apply emollients by stroking into the skin and consider using less greasy products.

● Changing out of sweaty clothes, particularly after exercise.

Folliculitis rarely requires oral antibiotics and usually resolves with a change in behaviour. If this does not occur, treatment for up to seven days with topical fucidic acid 2% is helpful. Furuncles and carbuncles are likely to need treatment with oral antibiotics (usually flucloxacillin or clarithromycin/erythromycin depending on allergy history). If a patient presents repeatedly with furuncles in the axilla/groin, a diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) should be considered.

There are many different fungal infections that affect the skin. Broadly speaking they can be divided into yeast infections and dermatophyte infections.

The most common yeast infection is candida which can give rise to several familiar conditions such as thrush (oral and genital), angular cheilitis (cracks at the corners of the mouth), napkin dermatitis (nappy rash), and chronic paronychia (nail fold infection).

Yeast infections are commonly seen in the very young and in old age. There are a range of risk factors including broad spectrum antibiotic therapy, high levels of oestrogen, a warm climate, endocrine conditions such as diabetes, and immune deficiency. Diagnosis can be aided by skin swabs and scrapings, but as candida are part of the natural skin microbiome, these results need to be corelated with disease severity.

● Careful drying of skin folds and interdigital spaces.

● Avoid sharing towels.

● Avoid walking bare foot in public spaces (especially when carpeted).

● Avoid socks and shoes that make the feet hot and sweaty as yeast thrives in such environments. Sandals may be helpful along with frequent sock changes and washing at a high temperature.

Oral candidiasis

Treatment

Miconazole gel (first line)

OR Nystatin

Vulvo vaginal candidiasis

Single oral capsule of fluconazole (first line)

OR

Single intravaginal clotrimazole pessary AND

Topical clotrimazole if there are vaginal symptoms

General advice

Good oral health

Ensure dentures fit and are clean

Avoid possible irritants such as bubble bath and perfumed cleansers

Avoid tight clothing

Napkin eczema

Mild erythema: barrier product

Moderate erythema: miconazole cream with mild topical steroid

Absorbent nappies

Regular nappy changes with skin cleansing

Avoid possible irritants such as bubble bath and talc

Angular cheilitis

Miconazole (with mild topical steroid if very inflamed)

Nail paronychia

Clotrimazole solution

Miconazole (with mild topical steroid if very inflamed)

Oral itraconazole/fluconazole for severe or intractable disease

Ensure dentures fit

Vaseline for lubrication

Good hydration

Protect hands during wet-work

Good skin care

Dermatophyte fungal infections are usually referred to as tinea and can affect virtually any part of the body. The second part of the name refers to the part of the body that is affected, for example tinea pedis refers to infection of the feet, while tinea capitis refers to infection of the scalp.

Tinea infections may be ovoid in shape depending on which part of the body they occur e.g. tinea capitis and tinea corporis. However, they can manifest in any shape, and it is common to see an erythematous, scaley advancing edge.

The edge of the lesion is the most active and diagnosis can be aided via skin scrapings from this area and/or subungual matter and/or nail clippings if the nails are involved.

Dermatophyte infections in the UK are usually passed from human to human but it is also possible for it to be passed from animal to human.

Dry palms

Inflamed dry feet

Circular/ovoid lesions on body

Type of tinea

Tinea manuum: just one palm is often affected with dusty white scale particularly in the palmar creases.

Differential diagnosis

Hand eczema: both palms usually affected and there will be general dryness and erythema rather than predominantly in the palmar creases.

Scalp lesions

Tinea pedis: moccasin distribution; clearly defined erythematous scaley edge; may be interdigital involvement; as with palms, creases in soles may be affected by fine scale.

Tinea corporis: annular border which is scaley and erythematous with clearing centre, may be mildly itchy, more likely to see a single lesion.

Tinea capitis: more commonly seen in children, look for patches of hair loss on the scalp (black dots represent broken hairs), there is usually erythema and scale.

Foot eczema: dry and scaley, likely to be itchy, less well demarcated edge.

Discoid eczema: no central clearing, may be very inflamed and moist in appearance, extremely itchy, more likely to be distributed bilaterally.

Scalp psoriasis: no hair loss, thicker scaling.

● The management measures outlined for yeast infections will be helpful.

● Avoid close contact with individuals who are known to have a tinea infection.

● In cases of tinea capitis, children should be kept off nursery/school until they have commenced treatment.

Mild tinea disease on the body (e.g. tinea cruris, pedis or corporis)

More extensive or inflammatory tinea disease on the body (e.g. tinea cruris, pedis or corporis)

First choice

Tinea of the nails

Tinea of scalp

Topical terbinafine twice daily for 2 weeks (e.g. Lamisil)

Second choice

Topical imidazole twice daily for 2 weeks (e.g. Daktarin)

Other comments

The addition of hydrocortisone to imidazole may help if very itchy or inflamed (e.g. Daktacort)

Oral terbinafine

250mg once daily for 2-4 weeks

Oral terbinafine 250mg once daily for 6 weeks to 3 months (toenails may need longer)

Oral terbinafine dose is weight dependent for 2-4 weeks

Nails are not successfully treated with topical products

In adults, oral itraconazole

In children, griseofulvin Sensible for patients to use ketoconazole shampoo to reduce fungal spores

There are multiple viral infections (sometimes known as viral exanthems) that manifest through the skin; however, they are not strictly considered skin diseases and therefore not within the scope of this handbook. The exception is eczema herpeticum which is covered in the chapter on atopic eczema.

For an excellent summary of viral exanthems visit the Primary Care Dermatology Society.

Psoriasis is a complex chronic inflammatory skin condition which is estimated to affect 2% of the population. It has numerous clinical presentations, the most common of which is chronic plaque psoriasis. It usually appears for the first time in adulthood but is occasionally seen in children. It is seen equally in men and women.

The pathophysiology is complex, but it appears to have a genetic component as it often runs in families. Genetic susceptibility can be triggered by several possible factors including stress, medications, including lithium, beta blockers, terbinafine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, anti-malarials (hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine being the highest risk), and physical trauma. For many individuals it is difficult to identify a specific trigger.

It is associated with several other chronic conditions including psoriatic arthritis, psychological co-morbidities and inflammatory bowel disease. For those with more severe disease, there is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.

Chronic plaque psoriasis most commonly presents as symmetrical, dry, scaley plaques (raised, ovoid patches) which are well demarcated. The size of the plaques varies from a couple of millimetres in diameter to covering large areas of the body.

In Caucasian skin tones, these plaques are pink/red in colour, while in darker skin tones they are darker red/purple in colour. If the scale is scratched away, pin-prick bleeding can occur.

The most common locations of the plaques are extensor surfaces (elbows and knees), scalp and lower back (natal cleft). If it occurs in flexural areas, the scale rubs away leaving the base colour depending on skin tone.

Symptoms for patients may include itch, dry skin, discomfort, soreness and psychological issues caused by the impact on quality of life.

Psoriasis can also affect the nail beds causing nail dystrophy on fingernails and toenails. Other types of psoriasis include pustular, erythrodermic and guttate, which require more specialised treatment and should be referred to secondary care.

Chronic plaque psoriasis is diagnosed clinically based on history and presentation. The most common differentials are:

Diagnosis

Tinea corporis (ring worm)

Description of differential

Round, inflamed, scaley patch on the body

Discoid eczema

Fungal nail disease

Round, inflamed, patch on body, often symmetrical

Nail dystrophy

Sub-ungual matter

But in psoriasis….

Scale is significantly greater

Distribution is symmetrical rather than unilateral

Usually more indurated (thicker)

Scale is more prominent

Less itchy than discoid

Usually more indurated

A clearer more well-defined border

Classic symptoms of nail disease are pitting in the nail surface and lifting of the nails from the nail bed

No fungal growth from nail clippings and scraping

● Significant psychological support is needed, and patients should be counselled that any treatment regime is about disease management rather than cure.

● Even once appropriate topical treatment has been instigated, psoriasis plaques can take months to resolve completely, and new plaques can occur.

● Plaques will typically clear from the middle outwards and once clear, can leave a mark on the skin that looks like a bruise. This may take several weeks to fade. Patients should be advised that once the skin is smooth, treatment can be discontinued.

● As well as identifying appropriate topical treatments, lifestyle counselling is a key part of the nursing role. Supporting weight loss and alcohol modification where necessary can be helpful, alongside cardiovascular monitoring.

Whilst emollients are not always considered a critical part of psoriasis treatment, they are often very helpful for reducing the impact of scaling. Daily use of an emollient (particularly one with urea in it) is recommended.

● Remind patients that Vitamin D analogues are irritant, so if the product gets on to non-psoriatic skin, it can cause irritation. It is important to be mindful of this, particularly if using Enstilar as a maintenance treatment.

● Plaques are clear once the skin is smooth.

● Careful washing of hands after application is advised to minimise inadvertent transfer.

● Topical treatments are not effective for nail psoriasis.

Fixed combination

vitamin D analogue/ betamethasone (Enstilar)

Once a day

Up to 4 weeks, then review. Further treatment can be given if needed No more than 105g weekly

Treat up to 30% of body surface area only

Once cleared, consider:

Twice times weekly (non-consecutive days)

Long term maintenance

As above

Vitamin D analogue alone (Dovonex)

Twice daily

Ongoing

No more than 100g weekly

The only licensed treatment for flexural psoriasis is a vitamin D analogue called tacalcitol (Curatoderm).

However, because of the sensitive nature of flexural areas, moderate potency topical steroids are more commonly used for up to two weeks in a month.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors are also helpful in flexural areas, particularly for those who need longer-term treatment or when topical steroids are contraindicated.

Main symptom Application tips

Thick scaley plaques

Treatment

Combination coal tar and salicylic acid (e.g. Sebco)

Thinner plaque (or once thick plaques have been removed)

Ongoing for both thin and thick plaques

Hairline psoriasis

Fixed dose combined vitamin D analogue and betamethasone (e.g. Enstilar)

OR

steroid only scalp application e.g. Betacap

Coal tar-based shampoo, either used alone or in combination with Sebco or Enstilar

Rub into sections of the scalp and leave for 2-3 hours or overnight

Remove loose scales with comb

As above

See flexural psoriasis

Use 2-3 times per week

Allow lather to sit on scalp for 5 minutes

Lift hairline up and away when applying

Referral to secondary care should be considered for those with extensive disease that cannot be effectively treated with topical products. Those who have psoriasis in high impact sites e.g. the face or genitals should also be considered for referral even if the overall extent of their condition is not that great.

Scabies is a highly contagious parasitic infestation of the epidermis. The female scabies mite burrows into the epidermis and lays eggs. The key symptom, which is intense itching, is an allergic response to mite antigens, and can start days to weeks after infestation.

An individual may carry 10-20 scabies mites at any one time. The mites are transmitted by close physical contact e.g. sexual contact, although they can also be transmitted through shared bed linen, clothes and towels.

Scabies affects both sexes equally and is commonly seen in children and the elderly. While scabies frequently occurs in environments where people live in close quarters, such as care homes, it can occur in any location.

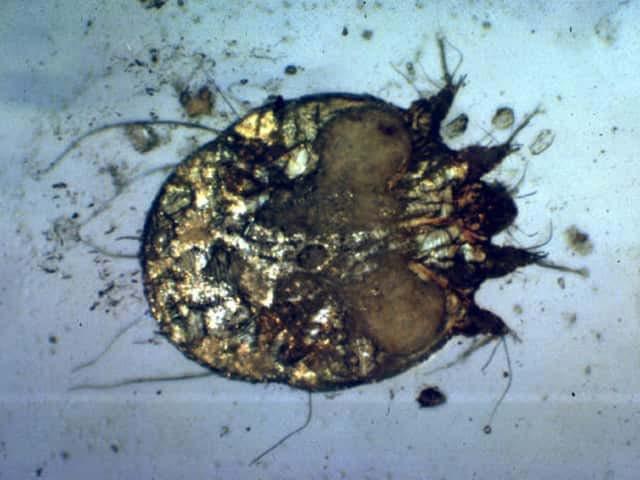

Patients who are immunocompromised or have some form of neurological impairment are at increased risk of crusted scabies (previously known as Norwegian scabies). Individuals with crusted scabies are hyperinfested with up to one million scabies mites. They are unable to mount the usual immunological response to the mite antigens and therefore may not itch.

Scabies presents as erythematous papules which are often symmetrical. It is sometimes possible to see the scabies burrow as a faint serpiginous (wiggly) line adjacent to the papules. Due to the intense itching which accompanies scabies, there are likely to be significant excoriations as well as a more generalised eczematous rash. Persistent scratching can break the skin barrier leading to bacterial infections and sometimes impetigo.

In adults, scabies is most commonly seen on the hands, wrists, axillae, thighs, buttocks, waist, soles of the feet, areola and genitals. It is unusual to see scabies mites affecting the head and neck in adults, but they may be seen in patients who are immunocompromised, as well as children, elderly and those with crusted scabies. In babies and children, the palms and soles are sometime affected.

Diagnosis is usually via a clinical history where intense itching, particularly at night, is key. It is possible to confirm diagnosis by excavating a mite from a burrow using a final needle and observing under a microscope. Crusted scabies presents as a generalised, extensive, crusty, erythematous rash which may not be itchy.

Folliculitis

> See page 46

Eczema

> See page 18

Folliculitis is typified by pustules appearing around hair follicles. Any papules or pustules associated with scabies often occur on non-hair bearing skin.

Both eczema and scabies are itchy, but scabies notably so at night.

Take note of whether other close contacts started itching at the same time, as this suggests scabies.

No previous history of eczema would make scabies more likely.

● Scabies is physically uncomfortable and can be psychologically distressing as it is often associated with significant stigma. Reassurance may therefore be needed.

● All members of the patient’s household and close personal contacts, including sexual partners within the last month, even if asymptomatic, should be treated. Careful contact tracing is needed to ensure effective treatment.

● Clothing, bedding and towels should be laundered at a minimum of 60 degrees centigrade once treatment has started.

● Clothing that cannot be washed should be sealed in a plastic bag for at least 72 hours.

● Mattresses and soft furnishings can be vacuumed or steam cleaned.

● Avoid close physical contact until treatment has been started.

● Keep nails short to avoid skin damage when scratching.

● Even after treatment, the skin may continue to itch for up to a month until the allergic response settles. Moderate topical steroids, applied for two to three days, can be helpful to manage itching.

● If the patient already has an immune mediated condition such as eczema or psoriasis, having scabies may make this worse.

● Topical 5% permethrin cream is first line treatment (Lyclear).

● The whole body should be treated, including head and neck, paying particular attention to under the nails and the areas most commonly affected (see above).

● The cream should be applied to cool, dry skin i.e. not straight after bathing when the skin is still warm. It should be stroked into the skin and will sink in itself; no vigorous rubbing is needed. Demonstrating how to apply topical treatment may be helpful in reducing the likelihood of treatment failure.

● One 30g tube is typically enough to treat an adult, but it depends on body surface area.

● Permethrin should be washed off eight to 12 hours after initial application. If hands are washed during this time, further permethrin should be applied to the hands.

● A second application should be made seven days after the first application. This second application is not necessary for asymptomatic contacts but should be applied to all those with a confirmed diagnosis of scabies.

● If the skin becomes infected, treatment with antibiotics may also be needed.

● If there is permethrin resistance, Malathion is an alternative treatment. Topical ivermectin may also be used, off license, if there are problems with resistance.

● There is no evidence of risk to pregnant or lactating women, although, if breast feeding, the skin should be free of permethrin.

● For scabies that is resistant to topical treatment, or if there are reasons why topical treatment is not possible, oral ivermectin can be used at a dose of 200 mcg/kg. Two doses seven days apart are recommended.

● For those with crusted scabies, both oral and topical treatment may be necessary depending on the level of the infestation. As an individual with crusted scabies will have high numbers of scabies mites, extra precautions to prevent cross infestation should be taken.

● Information for assessing and treating crusted scabies can be found at DermNet.

Referral to secondary care is rarely needed.

Urticaria is a common condition which is thought to affect 20% of the population at some point in their lives. It is caused by the release of chemical mediators including histamine.

Urticaria can occur as part of anaphylactic shock e.g. to a medicine, food or bee sting. However, ‘pseudo allergies’ to drugs such as aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and opiates can also lead to urticaria, as can foods, particularly those containing salicylates.

Urticaria is sometimes induced by heat, pressure from clothes or infection. The cause of urticaria is not always straight forward to identify and a careful history is always important. Sometimes, it might be impossible to identify the trigger for the urticaria.

Urticaria is characterised by itchy wheals (hives) usually against an erythematous background. The wheals can flare and remit, spontaneously coming and going within a few minutes and up to 24 hours. They can present as small slightly raised patches or they can cover large parts of the body in a map-like distribution.

Acute urticaria is described as urticarial episodes that lasts for no more than six weeks and chronic urticaria consists of episodes that occur over more than a six-week period. Angioedema may present alongside urticaria. Characterised by swelling in the deeper tissues, it is more commonly seen on the face and genitals. The swelling may be accompanied by soreness or pain.

Wheals classically seen in urticaria

Angioedema

There are no specific clinical markers for the diagnosis of urticaria, however there are few other conditions that are transient nature. The surface of the skin shows no changes other than erythema and texture of the skin generally remains normal.

The challenge for the clinician is to identify and minimise triggers.

● If the patient is acutely unwell and the urticaria is part of anaphylaxis, immediate emergency treatment is needed. This includes administering adrenaline via an EpiPen if the patient has one. Transfer to emergency care may be needed.

● As urticaria (and in particular chronic urticaria) can have a significant impact on mental health, this should be acknowledged and support provided as appropriate.

● Take a close medication history, noting the use of drugs that are known to trigger urticaria.

● Advise minimisation of behaviours that are likely to aggravate flares such as heat, pressure and stress. However, be aware that these factors may not resolve the urticaria.

● Ask the patient to take photographs of flares as this can be helpful if they present in clinic without any symptoms.

● It may be that no further treatment is needed, particularly if the episodes are infrequent and do not persist.

The mainstay of treatment for urticaria are antihistamines.

Non-sedating antihistamine (secondgeneration) e.g. fexofenadine

Sedating antihistamine (first-generation) e.g. hydroxyzine

1. One tablet once a day

2. If above does not control, then one tablet twice daily

3. If above does not control, then two tablets twice daily OR one tablet four times a day

If above does not control, consider trying an alternative second-generation antihistamine

For an adult, 25-50mg at night in addition to step 2

The dose should be kept at the lowest dose to control the urticaria. Although long-term non-sedating antihistamines are generally safe, healthcare practitioners should always consider other co-morbidities. If sedating antihistamines are needed, they should not be considered as a long-term treatment.

If urticaria is persistent and/or the above treatment regime does not work, a referral to specialist care will be needed.

Whilst the exact aetiology of vitiligo is not yet understood, it appears to have an autoimmune basis in which melanocytes are destroyed by a misdirected immune response. There also appears to be a genetic component as around 30% of those with vitiligo have a relative who also has the condition.

Men and women are equally affected, with approximately 1% of the global population having the condition. However, vitiligo appears to be more prevalent in people with darker skin tones.

The natural history of the condition is usually rapid loss of pigment with smaller macules joining together. These usually stabilise but rarely spontaneously repigment.

Vitiligo appears initially as depigmented macules on the skin, these can then coalesce forming larger patches. They are usually symmetrical. The skin texture does not change and there are rarely any other physical symptoms, although there may be mild itch.

Vitiligo can sometimes affect the hair causing pigment loss, leading to premature greyness. Early macules are usually noted on the hands, face and neck, but commonly lesions appear in parts of the body that are hyperpigmented naturally, e.g. the groin, areola, axilla and genitals. Vitiligo is more noticeable in skin of colour.

Vitiligo

Pityriasis alba

Post‐inflammatory

Complete loss of pigment, skin is normal texture

A type of eczema where there are hypopigmented patches, often mildly erythematous with fine scale

Skin surface often normal but pigment is still present i.e. skin is a shade lighter than normal

Hypopigmented patches of skin from birth usually associated with a section of white hair

● As vitiligo can have a significant impact on mental health, support for mental wellbeing is important.

● Patients should be counselled that although there are treatments available, relapse is usual.

● Patients should be given sun safety advice, including the use of high factor sunscreens (both UVA and UVB) particularly to the areas of depigmentation. In those with lighter skin tones, avoiding tanning will mean that the patches are generally less visible.

● Recommend camouflage services which are extremely helpful and will teach individuals how to use products to cover up the depigmented areas. These services are rarely available on the NHS, but the charity Changing Faces provides a service.

Central areas of vitiligo, e.g. the face and recently developed patches, are most likely to respond positively to topical treatment. Patches on the extremities (e.g. the hands) and those that are well‐established are least likely to respond positively. The treatments outlined here are used off‐label.

Treatment Area Considerations

Areas of thin skin (e.g. face, genitals) in adults

Areas of thicker skin (e.g. body) in adults

Tacrolimus (protopic) twice daily for up to three months

AND

Once daily potent topical steroid e.g. mometasone.

Once daily potent steroid with consideration for a super potent topical steroid (e.g. dermovate) if little response after three to six months.

Discuss possible consequences of long‐term potent steroid use such as skin thinning and hypertrichosis. Discontinue topical steroids if this is seen.

Children

Tacrolimus twice daily for up to three months.

As above.

Impact of topical steroids will be much greater in children, so a non-steroidal option is preferred.

Narrowband UVB is a secondary care treatment which can be effective in patients who have had little success with topicals and/or are significantly affected psychologically by vitiligo. Treatment periods are prolonged (up to a year).

Rapidly progressing vitiligo warrants an urgent referral to secondary care.

As well as providing an excellent source of dermatology images, DermNet NZ have a comprehensive glossary of terms. This glossary can be accessed here.

While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy of information, the use of and reliance on the information provided is entirely at your own risk. The BDNG does not make any warranty that the information we have provided is accurate or up-to-date, and we assume no responsibility for any consequences of relying on such information.

The information in this handbook represents the current view of the contributing authors only. It does not represent the views of the BDNG, any sponsors or supporting institutions. Inclusion of any named products does not indicate an endorsement from the authors, the BDNG, sponsors or supporting institutions.

The BDNG would like to extend our thanks to DermNet NZ for use of the images found in the handbook. Artificial Intelligence (AI) was used to assist the designer when removing watermarks from the images. This is the only time AI was used in the creation of this handbook.

All links provided in this handbook are not under our control or monitored by the BDNG. The links are provided for your convenience only. The BDNG does not endorse, and are not responsible for the content, validity, accuracy or your use of, those websites. The inclusion of any such links in this handbook does not indicate an endorsement from the authors, the BDNG, sponsors or supporting institutions.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the BDNG. Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the BDNG or the editorial/advisory board. Advertisements have no influence on editorial content or presentation.

The BDNG logo and name are Registered Trademarks. All registered rights apply. This handbook is published by the BDNG, 82 Antrim Street, Lisburn BT28 1AU Tel: 02892 793 981. www.bdng.org.uk

Rebecca Penzer-Hick Handbook Editor

Senior Lecturer, Postgraduate Medicine, University of Hertfordshire, and Dermatology Specialist Nurse, Dermatology Clinic Community Services, Cambridgeshire

Rob Mair Managing Editor rob.mair@pavpub.com

Lauren Nicolle Deputy Editor lauren.nicolle@pavpub.com

Sarah Copperwheat Lead Nurse Prescriber and Team Manager, Dermatology Sussex Community Service, Hove

Lucy Moorhead Nurse Consultant, Inflammatory Skin Disease Guy’s and St, Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

David Carmona Practice Nurse Buckden and Little Paxton Surgery St Neots

Ccreative Direction info@pongoandmatelot.co.uk pongoandmatelotstudio