VERTICAL_STUDIOS #VS_MONTAGE

SCAFFOLD PEDAGOGIES AS KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

SCAFFOLD PEDAGOGIES AS KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Prof. Gerhard Bruyns - Associate Professor, The School of Design, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Prof. Daniel Elkin - Associate Professor, The School of Design, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

DOI 10.31182/SDIndex.KAVA7751

#Vertical_Studio; #VS_Montage; #montage; #physical; #informational; #narrative_spaces; #cuisine; #HongKong_gastronomy; #narrative_space; #catalogue; #archive; #living_database; #collage; #montage; #narration

“Montage: The production of a rapid succession of images in a motion picture to illustrate an association of ideas.” (Merriam Webster, 2023) Our living environment outlines settings where spatial and informational realities coexist. First, the environment is a ubiquitous data driven spatial reality. This reality materialises through spatial tags, google maps, reviews and attached coded information that enlarges object’s ‘meta’ presence, more than its actual physical existence. In spatial, interior and architectural design processes, this overlaying of information with actual spaces is best described through the rise and articulation of Building Information Modeling (BIM). BIM systems tag each part of a space, from the planning stage to completion, like an image on Instagram. The tags allow the attachment of additional information such as material provenance, including information related to the massing properties specific to its length, height, and width, usually described within the traditional oblique spatial projections namely the plan, sections and elevations.

Subsequently, objects contain values based on their historical, cultural, material and thus embedded qualities. For instance, a handrail made from wood with scratches from decades of use allows for the reading of such traces in what Walter Benjamin (1936) coined as the ‘aura’ of an object.

The notion of ‘montage’ merges the material qualities and information narratives into one totalizing complex of analysis and historical documentation. The application within both the analytics as well as design competencies forms an ideal testing bed in educational curricula and a vertical learning experience between years.

“Cuisine: Manner of preparing food: Style of cooking.” (Merriam Webster, 2023)

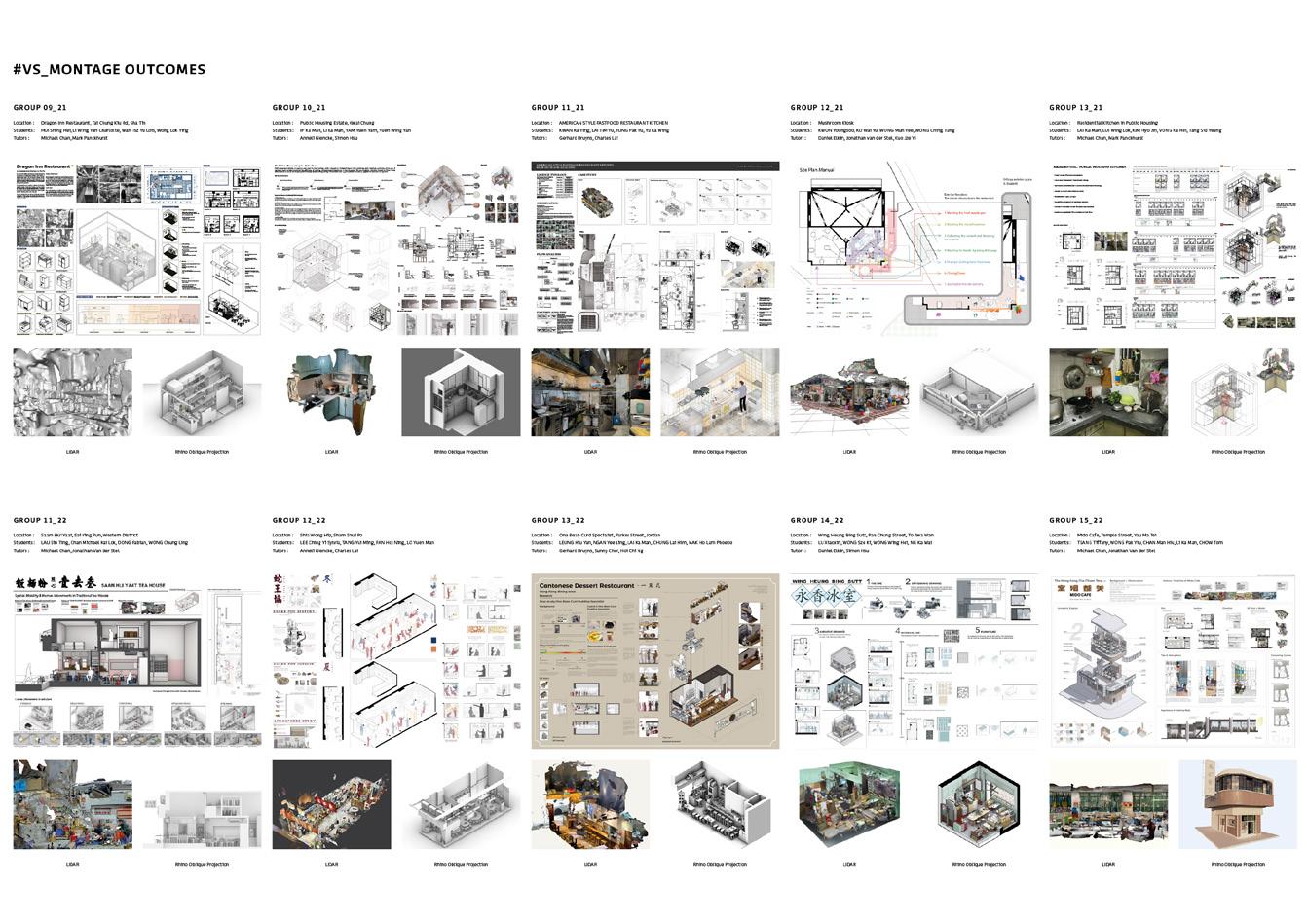

Within the montage framework, the 2021 and 2022 VERTICAL STUDIO [VS] modules of the Environment and Interior Design Discipline focussed on the multidimensional and multi-representational reality, in which narratives, information and perception collide and can collapse.

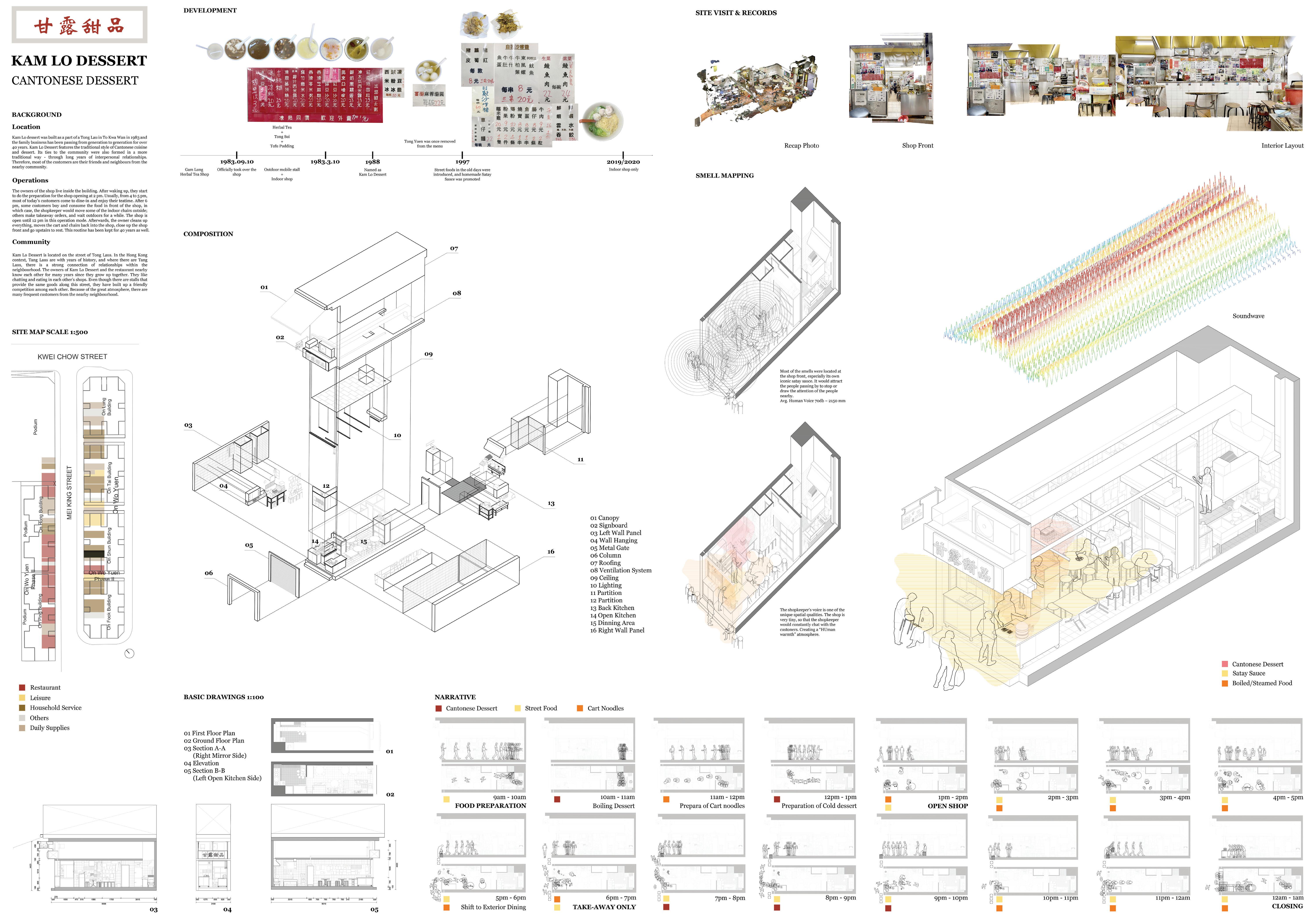

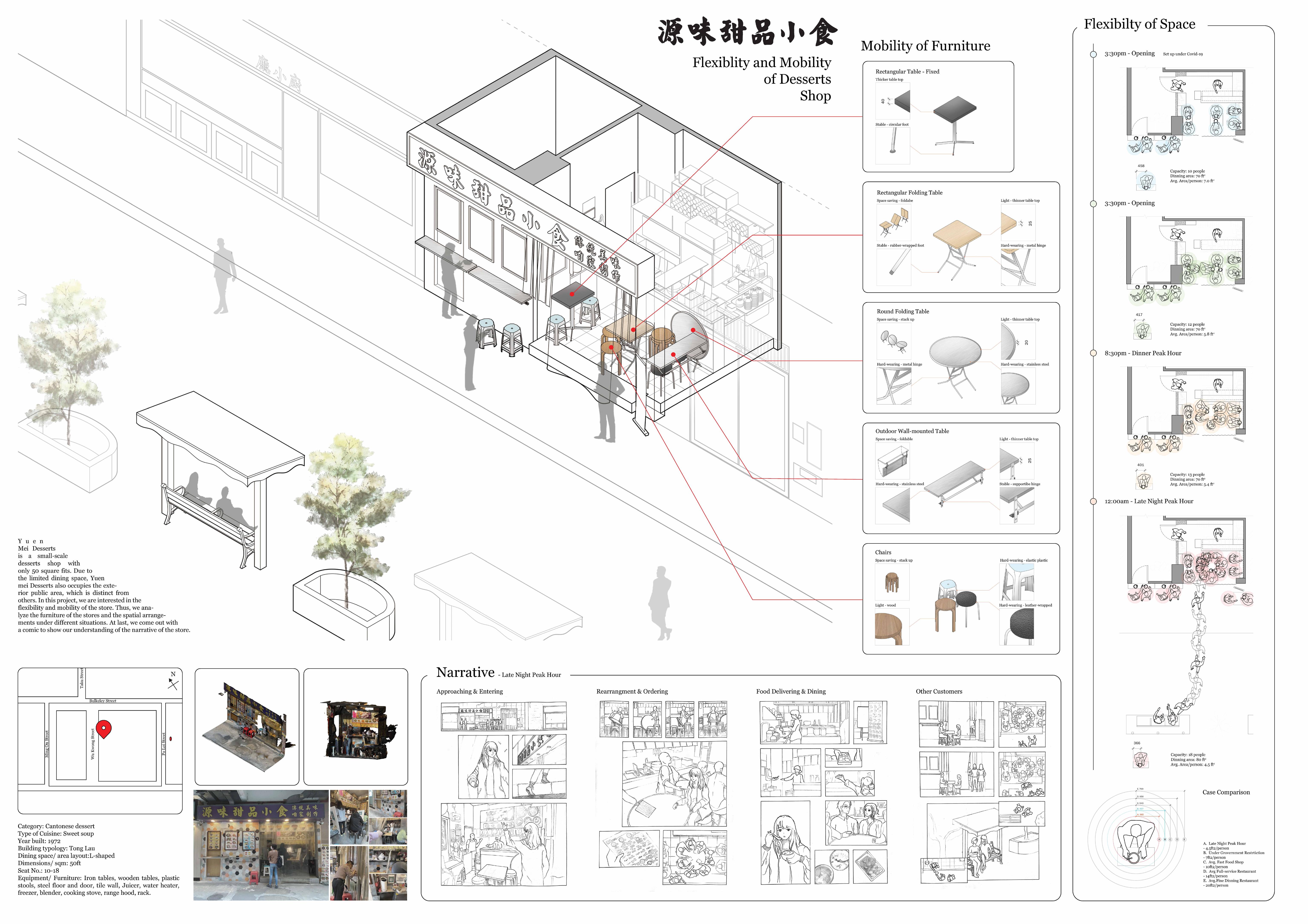

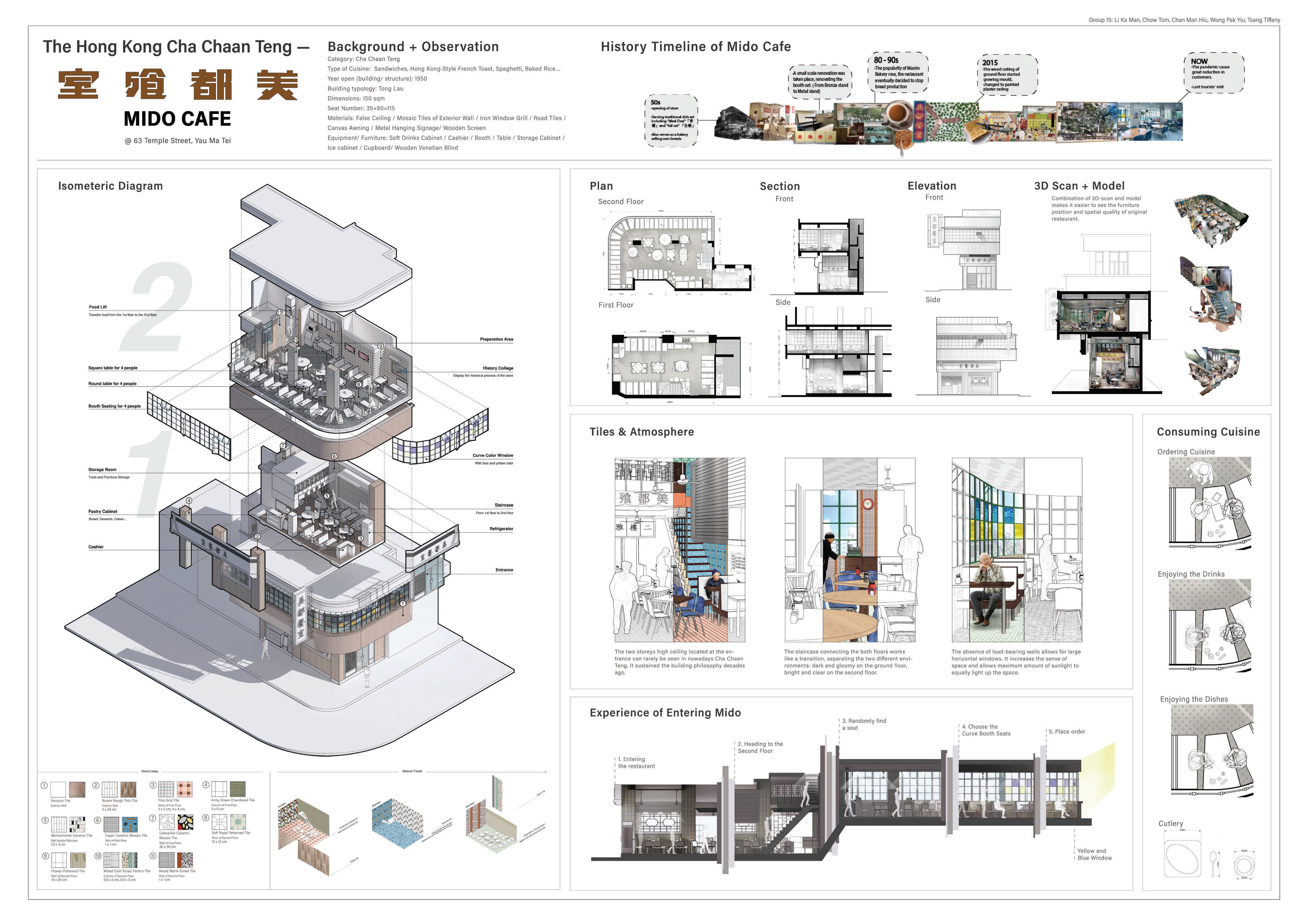

Centring attention on the theme of ‘Hong Kong Gastronomic Interiors’, the #_ VS modules studied various Hong Kong kitchens [2021] and Hong Kong cuisine typologies [2022] in terms of their diverse gastronomy, society, and spatial realties. With Hong Kong’s rich and unique food culture, the combination of eastern and western influences adds an additional place-identity layer to the processes of how people interact with the environment. Apart from Hong Kong’s cuisine settings as importance as design venues, each setting is a merger of local and traditional culture with globalized processes.

Typologically speaking, categorical boundaries between different Hong Kong cuisines remain blurry. This equally pertains to each cuisine type’s processual characteristics and its spatial relationship to an interior and building type, for example podium, Tong Lau, Kowloon block, shophouse, industrial, village house or hawker kiosk.

With the initial definition of basic indoor and outdoor cuisine types, the Vertical Studio #VS_MONTAGE examined:

a. Indoors cuisine: Cantonese Banquet Halls (Sui Mei, Chiu Chow, seafood); Yum Cha / Teahouse (Dim Sum); Cha Chaan Teng (instant noodles, sandwiches, Hong Kong-Style FrenchToast, curry, rice dishes); Soy Sauce Western cuisine (Swiss chicken wings,oven-baked pigeon, stir-fried beef noodles with Swiss sauce); Hot Pot / Clay Pot Rice cuisine; Cantonese dessert (sweet soup, tofu pudding, red bean soup / mung bean soup,black sesame soup, glutinous rice balls, steamed egg / milk custard, mango sago).

b. Outdoor or Take Away typologies involved: Dai Pai Dong (open-air cooked food stall); Hong Kong Bakeries; Street Food Stalls (egg waffles, fish balls, tofu, noodle, congee, Shanghainese food).

This booklet sets out the Vertical Studio process, its tools and outcomes covering the 2021 and 2022 vertical studios titled #VS_MONTAGE. We view this as a key aspect to knowledge transfer, disseminating the method and outcomes across teaching faculty but also disciplines. Apart from the overview of 38 student outcomes, the body of work captures two key text. A text by dr. Mike Louw and dr. Sally Farrah (University of Canberra) on the question of linking food to space and users.

Their contribution explores intersections between food, architecture, and urban spaces, advocating for “intelligent” practices amid climate change, urbanization, and inequality. They link regional cuisines and vernacular architecture, emphasizing local ecosystems and heritage as vital to cultural memory. Migration and movement—through rituals, preparation, or delivery— reshape food spaces, blending global and local identities. Post-colonial contexts reveal tensions between preservation and innovation, spatial justice, and power dynamics in food systems. The authors critique binaries (local/ global, tradition/modernity), proposing hybrid “third spaces” for equitable collaboration. Ultimately, they argue for valuing empathy, sustainability, and memory in designing food and built environments that reflect planetary and

human interconnectedness.

The second text by Chun Chuen Billy Chan, from The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, questions the how and in what way the Vertical Studio model integrates educational scaffolding—rooted in Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development—into design pedagogy, merging multi-year cohorts in collaborative roles. While advocating scaffolding to modernize curricula for industry demands, Chan cautions against its theoretical misapplication, stressing alignment with experiential learning (Kolb) and constructive pedagogy to bridge academia and practice.

As mentioned, this booklet showcases 38 outcomes from a two-year Vertical studio initiative. In addition to the aims, objectives and thematic definition, the work outcomes highlights the importance of digital assets as educational medium. For ease of dissemination, the shown outcomes could be separated into two parts.

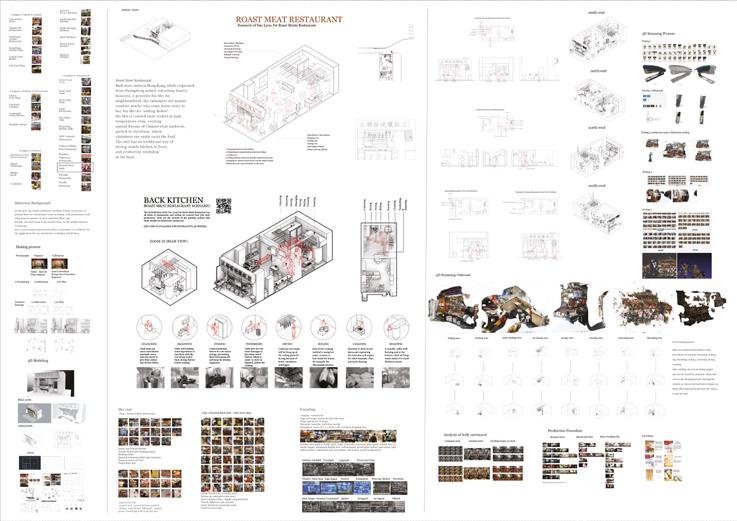

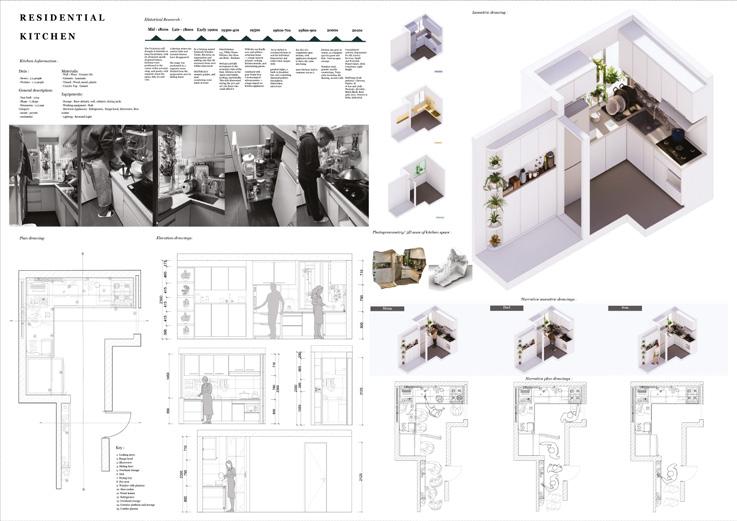

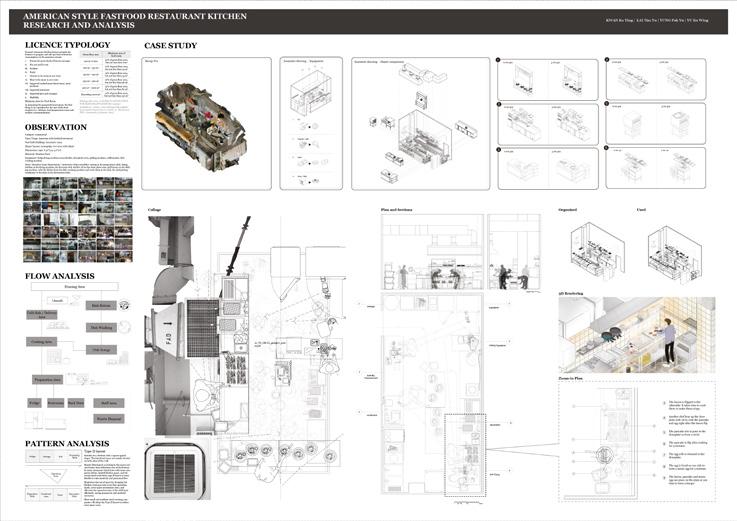

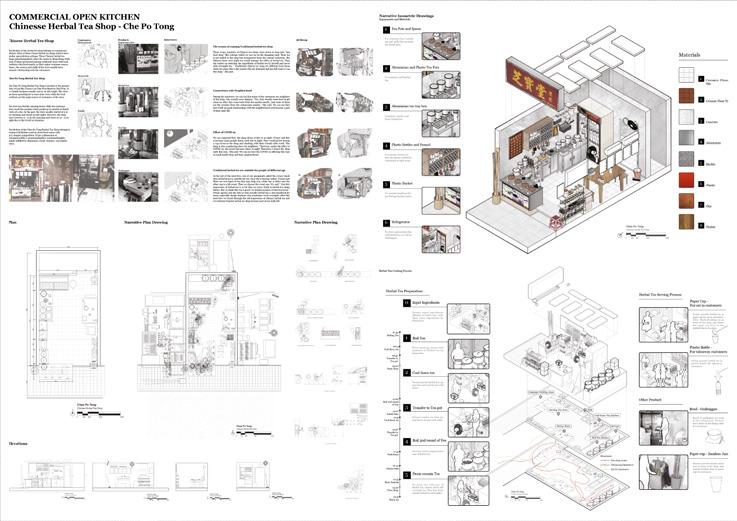

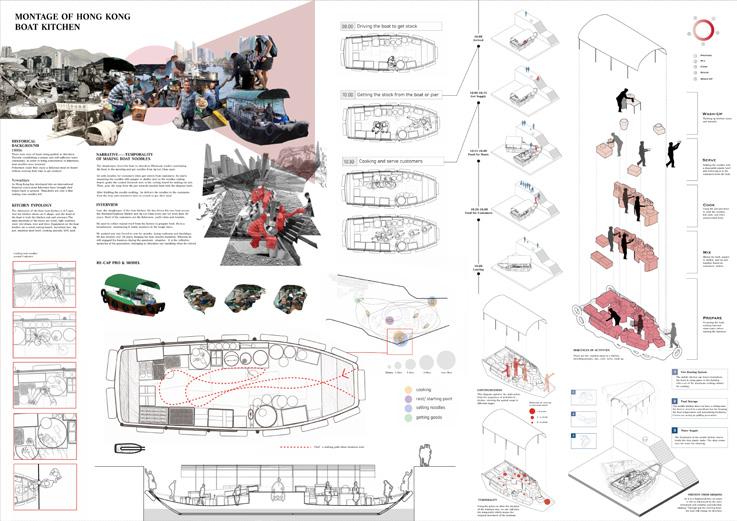

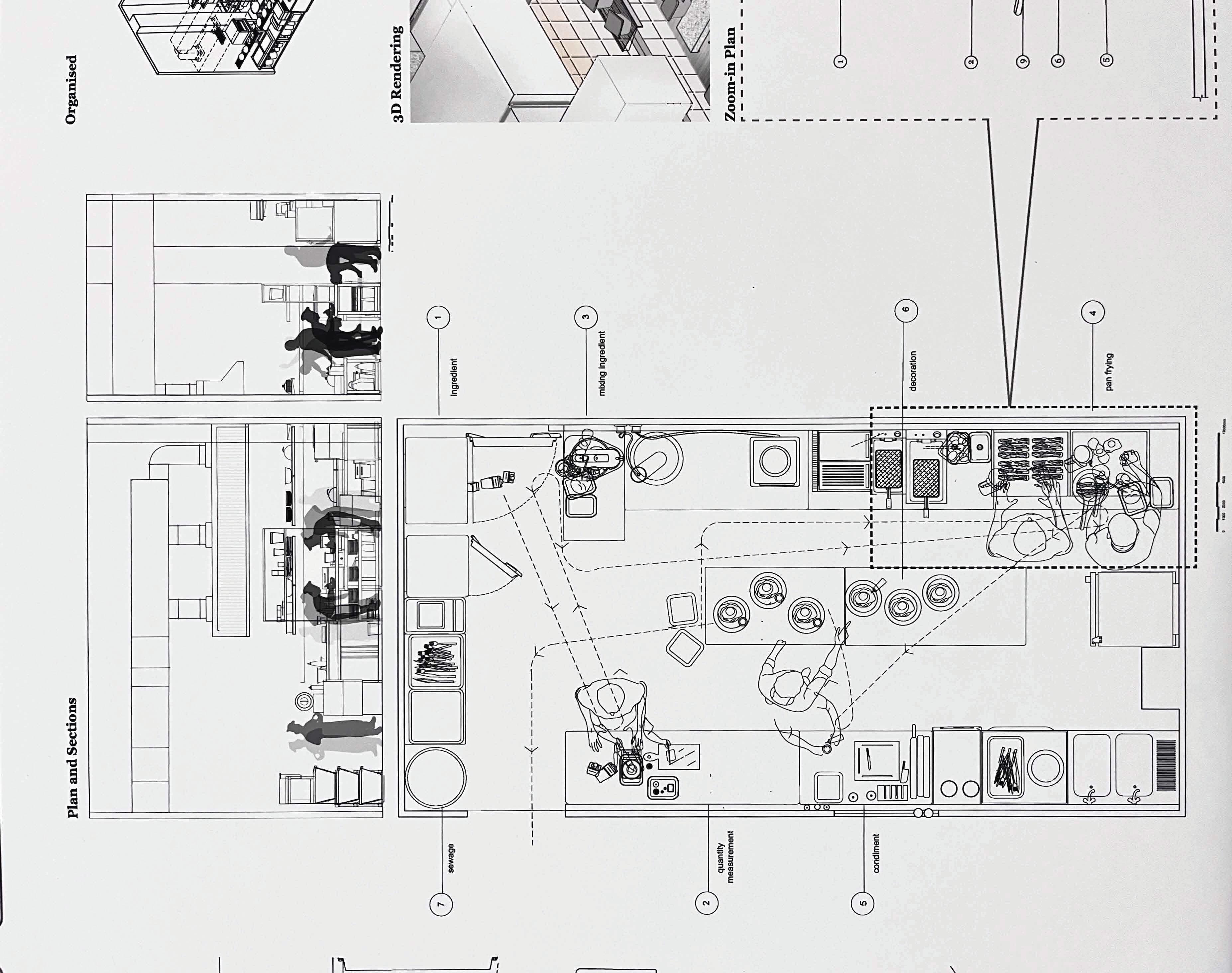

Part 1 outlines the detailing of the ubiquitous data driven spatial reality across four examples of work. Step one documents the analysis of kitchen or cuisine typologies dependent on photographic and site measurement documentation. Step two mechanises LIDAR scanning protocols for each space, using handheld mobile phone and downloadable apps to fuse numerous images together. Step three develops the translation of LIDAR data into oblique spatial projections, supported by step four, with the mirroring of the oblique spatial projections into Rhino.

Step 01 - Site Geographic Documentation

Step 02 - Lidar Scanning

Step 03 - Oblique Spatial Programme Step 04 - Rhino Oblique Programme.

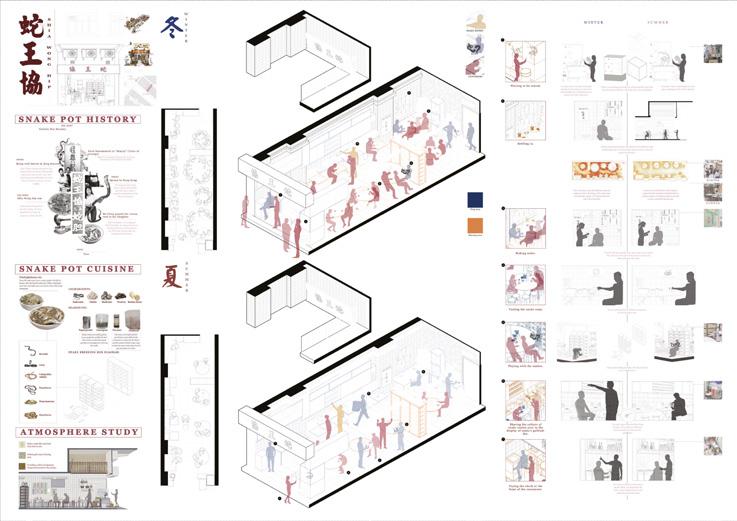

Part 2 provides a synoptic overview of informational realities associated with each typology. Defined as group outcomes, each poster is tagged with the narrative and societal processes layered into the use of kitchens and cuisine types. At various resolutions of details the tagging of user behavior with spatial specificities remains a key outcome.

Part 3 reflects the procedure of digitally preserving all vertical studio results. The compilation, digital tagging, and categorisation of over 5,000 digital assets into an online archive via single sign-on functionality constituted a significant accomplishment in this endeavour. In addition to collaborative peer-to-peer efforts, the vertical studio necessitates the implementation of archival and reference protocols. This focusses on the objective of establishing an expanding archive for students to reference regarding technological feasibility, as well as for drawing and analytical outcomes.

The #VS_MONTAGE Vertical Studio is in part a learning support programme, between peers and between years. Roles are assigned to each year to facilitate development before allowing for the transference of these skills.

Year 1 First year students focus on narrative component of montage. This covers digital literacy and visual communication through aspects, digital skills in Adobe Creative Suite Photoshop, Indesign, and Illustrator, and layout skills for visual materials and research outcomes.

Deliverables: One graphically and conceptually narrative based thought-through A0 layout including research, drawings and photographs provided by Years 2 and 3.

Year 2 Second year students focus on the informational component of montage.

The translation of one restaurant typology into a two-dimensional plan drawing including various layers of historical, technical, material, narrative and related information all in one synoptic overview. This includes the execution of relevant research on one cuisine category/ restaurant typology in Hong Kong; and enhance digital skills using CAD

programme by creating a complex multi-layered two-dimensional plan drawing.

Deliverables: One graphically well-presented two-dimensional plan drawing at scale 1:20 including various layers of informational data

Year 3 Third year students focus on the physical component of montage. Year three covers the surveying and documentation of a spatial typology using the technique of photogrammetry. In addition, this year acts as co-instructors, facilitating software knowledge transfer to second year students. More importantly third year students develop digital skills in the domain of surveying and documentation through new photogrammetric 3D environment scanning software ReCAp Pro/ Photo, as well as develop interpersonal and educational skills in the domain of becoming co-educators.

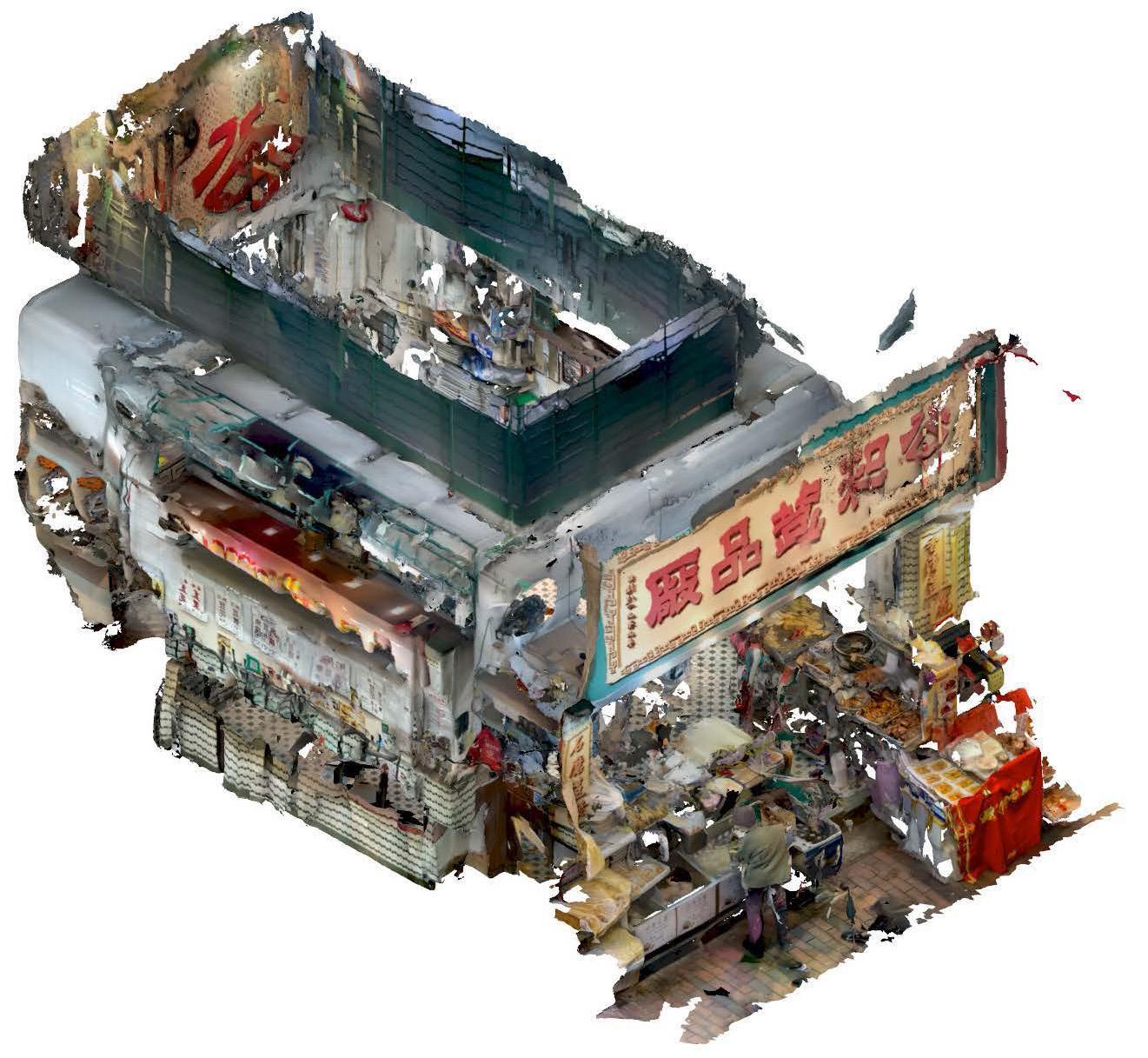

Deliverables: Exhaustive photographic and site measurement documentation of the restaurant / cuisines surveyed in its physical existence by using the technique of photogrammetry. One assembled photogrammetry depicting the surveyed venue, with refinements in Rhinoceros 3D resulting in one three-dimensional isometric image representing its spatial qualities.

Year 4 Year four students fulfill the role of peer advisors. When questions arise from any of the other years, they are free to consult with fourth year students.

Deliverables: Peer-to-peer mentorship and guidance where needed or required by first, second and third year students.

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER 1 - THE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, THE HONG KONG POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY, HONG KONG SAR, CHINA

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER 2 - SCHOOL OF DESIGN AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT, UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA ACT, AUSTRALIA

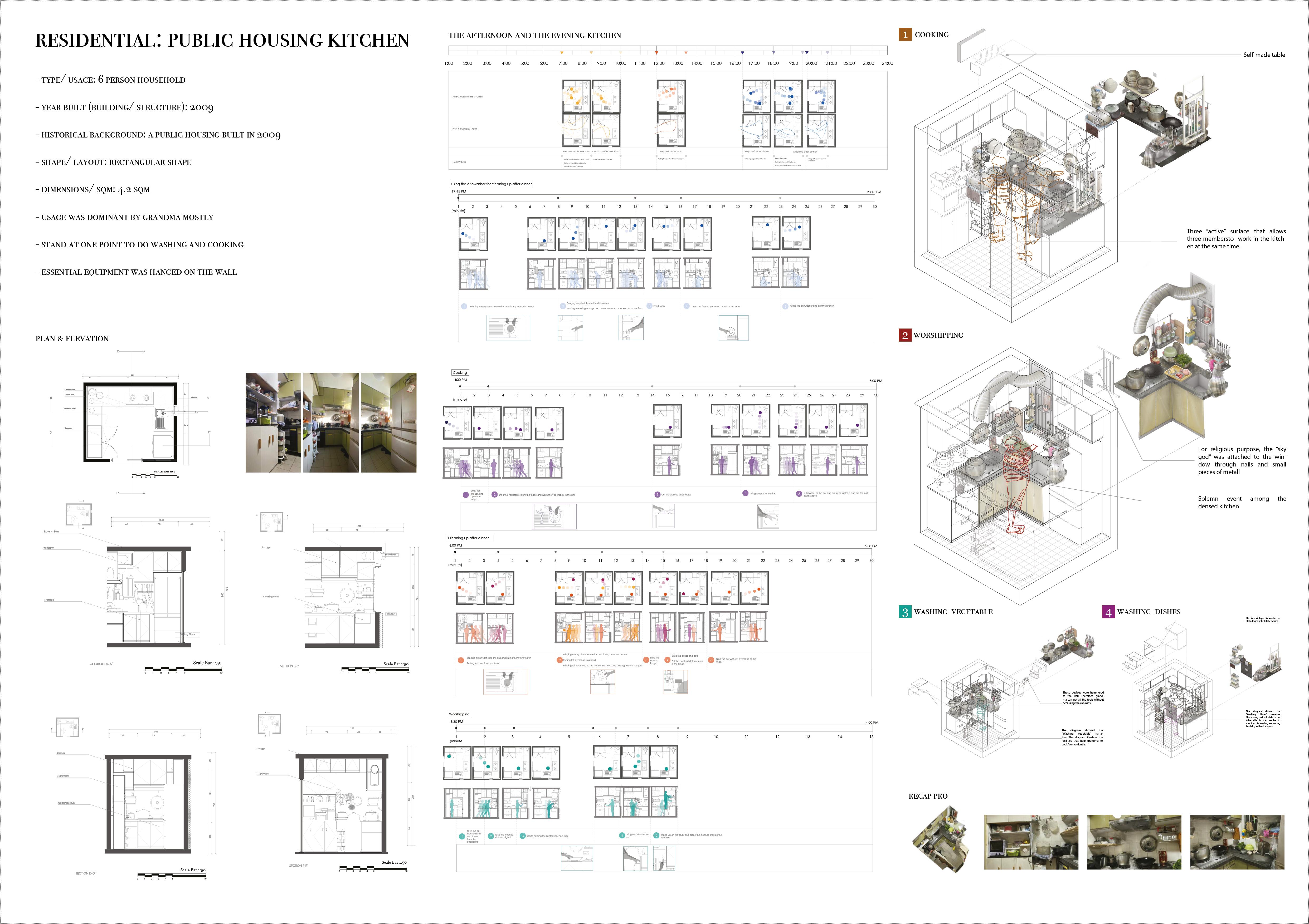

LOCATION : Fung Wong Chuen Building, Chuk Un, Wong Tai Sin

STUDENTS CHAN Michael Kai Lok, WONG Tak Mei, CHOW Hei Kiu Ellie, CHUNG Siu Chun

TUTORS : Anneli Giencke, Simon Hsu

LOCATION : Yau Lyun Fat Roast Meats Restaurant, Hung Hom

STUDENTS CHAN Wing, WONG Chung Ling, HUI Hin Sing, KUNG Wing Sze

TUTORS HUI Hin Sing, KUNG Wing Sze

LOCATION Residential Kitchen

STUDENTS : CHANG Shu Ting, NG Sze Wing, LAM Yuen Wai, LAU To

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Jonathan van der Stel, Kuo Jze Yi

LOCATION Lan Fong Yuen, Central

STUDENTS : CHENG Pak Ki Rex, MAK Ho Lam Phoebe, LIU Kai Hei Ruby, NG Wai Lok

TUTORS : Anneli Giencke, Simon Hsu

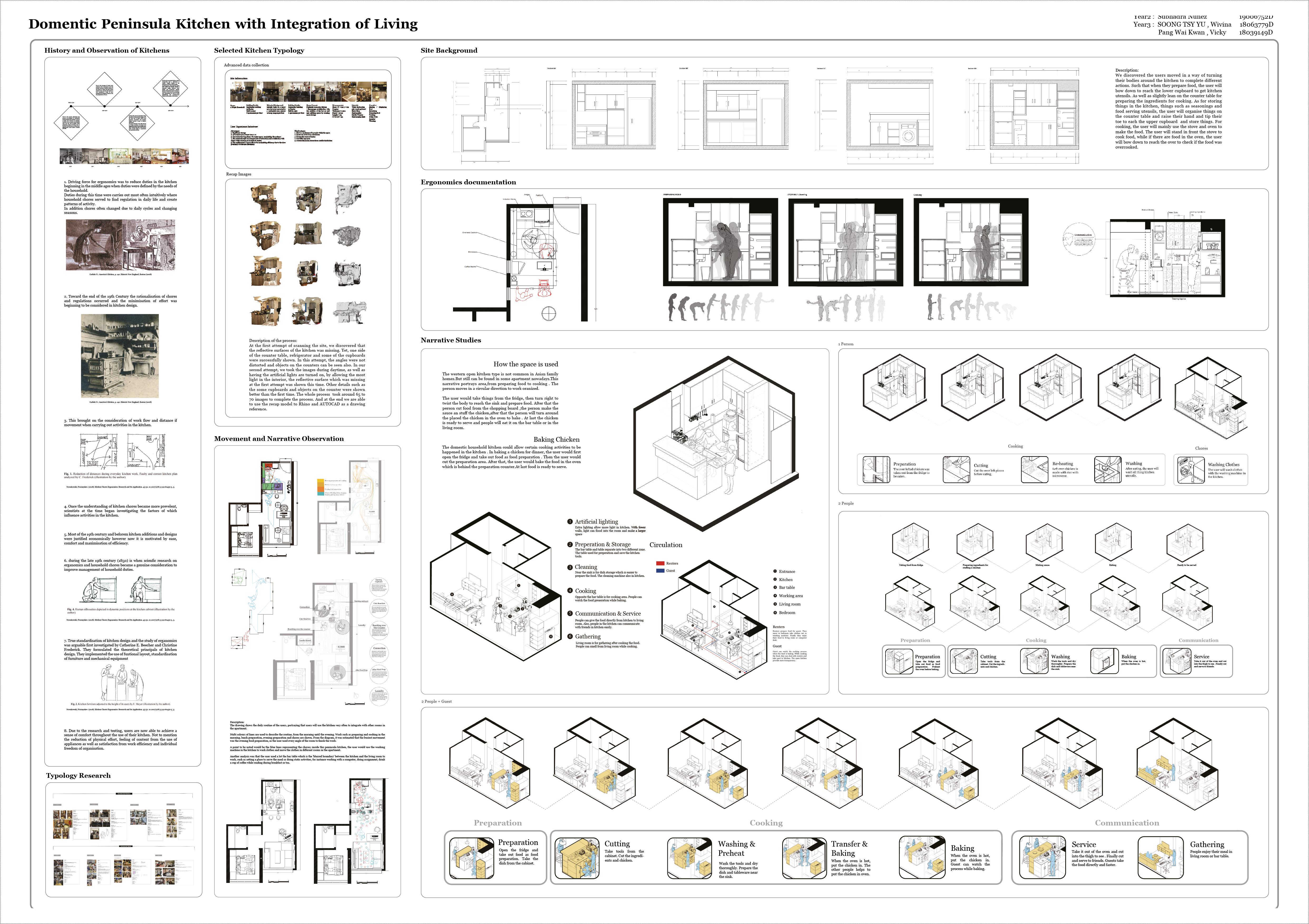

LOCATION : Domentic Peninsula Kitchen

STUDENTS FU Yuet, LILLEY NUNEZ Subhadra Devi Dasi, PANG Wai Kwan, SOONG Tsz Yu

TUTORS : Gerhard Bruyns, Charles Lai

LOCATION Lan Fong Yuen, Central

STUDENTS HONDA Kensei, LIEW Chi Him, TANG Chi Tat, TSE Man Yan

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Jonathan van der Stel, Kuo Jze Yi

LOCATION Dragon Inn Restaurant, Tai Chung Kiu Rd, Sha Tin

STUDENTS : HUI Shing Hei, Li Wing Yan Charlotte, Wan Tsz Yu Lois, Wong Lok Ying

TUTORS Michael Chan, Mark Panckhurst

LOCATION Residential Kitchen

STUDENTS : CHAU Mei Yee, NAIK Ankita, LEE Kiu Chor, LI Shing Hon

TUTORS : Michael Chan, Mark Panckhurst

LOCATION Public Housing Estate, Kwai Chung

STUDENTS : IP Ka Man, LI Ka Man, YAM Yuen Yam, Yuen Wing Yan

TUTORS Anneli Giencke, Simon Hsu

LOCATION : AMERICAN STYLE FASTFOOD RESTAURANT KITCHEN

STUDENTS KWAN Ka Ying, LAI TIM Yu, YUNG Pak Yu, Yu Ka Wing

TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Charles Lai

LOCATION Mushroom Kiosk

STUDENTS : KWON Youngsoo, KO Wai Yu, WONG Mun Yee, WONG Ching Tung

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Jonathan van der Stel, Kuo Jze Yi

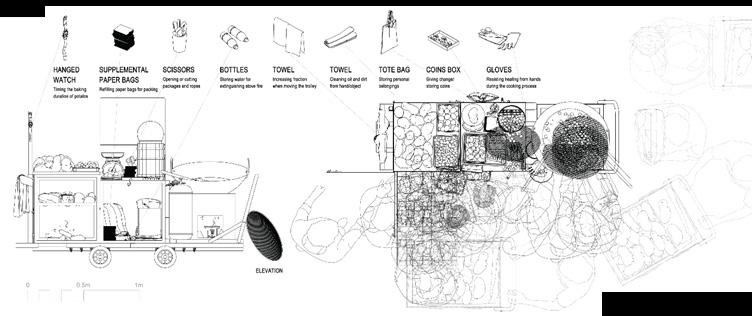

LOCATION Chestnut Stall, Mong Kok

STUDENTS TAM Hoi Ching, TAM Wan Ting Wylie, Chuk Chi Wai Vincent, KWOK Tsz Kwan, IP Cheuk Yan, HEO Sur Yun

TUTORS : Michael Chan, Mark Panckhurst

LOCATION Cha Chaan Tang

STUDENTS TANG Yui Ming, Wong Wing Hei, CHOI Hoi Yan, CHU Ka Lam, CHAN Yin Yeung, Chan Man Wai

TUTORS : Anneli Giencke, Simon Hsu

LOCATION Wing Wah Cafe, Cha Kwo Ling Main Street, Yau Tong

STUDENTS AU Choi Shan, HUI Shing Hei, NAIK Ankita

TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Sunny Choi, Hoi Chi Ng

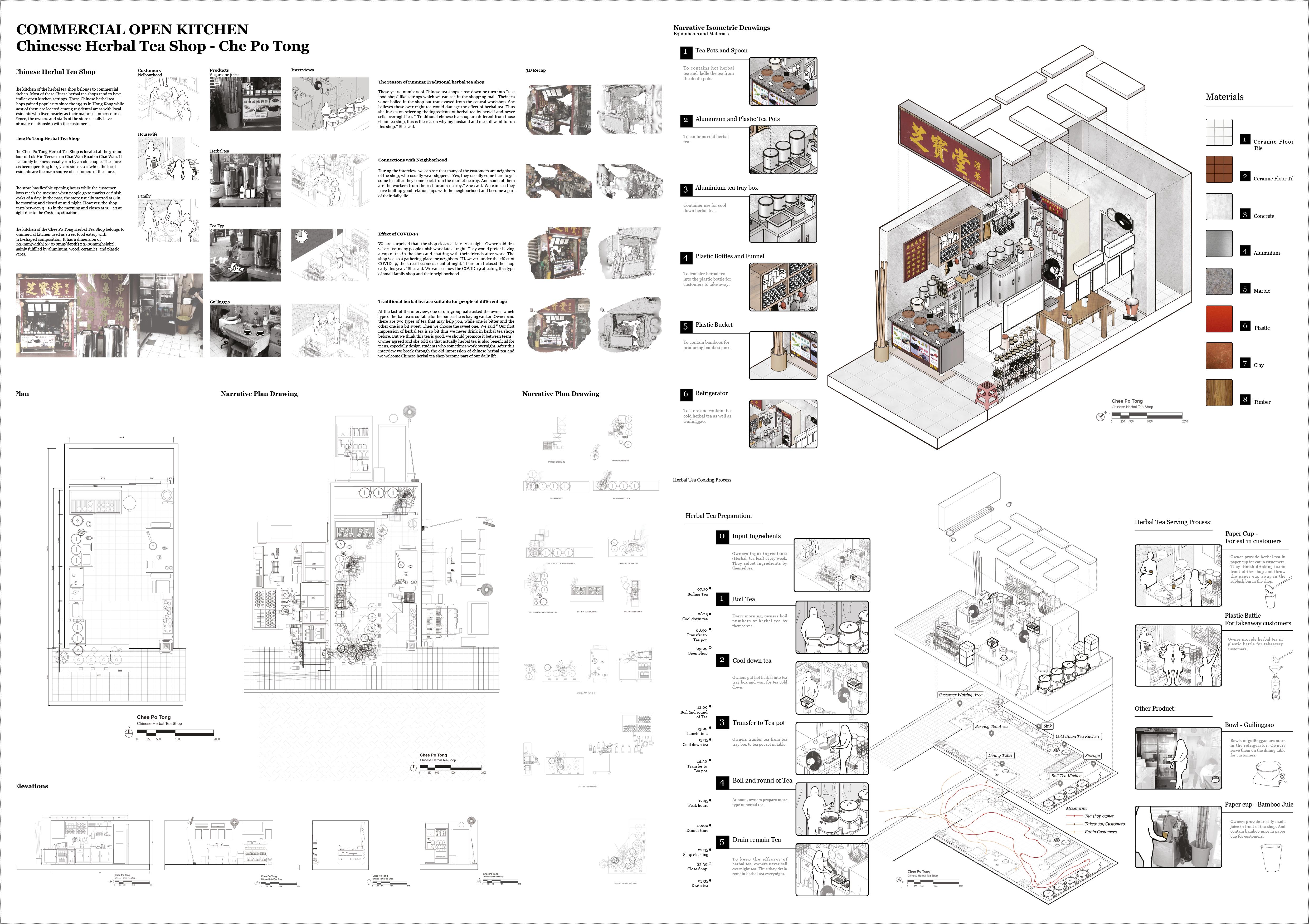

LOCATION : Tak Sin Tong, Siu Sai Wan Road, Chai Wan

STUDENTS : LAI Ka Man, LUI Wing Lok, KIM Hyo Jin, VONG Ka Hei, Tang Siu Yeung

TUTORS : Michael Chan, Mark Panckhurst

LOCATION : Ying Ying Kitchen, Ting On Street, Ngau Tau Kok

STUDENTS MAK Zhe Wing, MARIA Anona Sandy, KAM Long Yin Brian, SZE TO Ka Ming, SIU Hoi Yin

TUTORS : Anneli Giencke, Simon Hsu

LOCATION Boat Noodle, Aberdeen Harbour Shelter

LOCATION Kung Wo Beancurd Factory, Pei Ho Street, Sham Shui Po

LOCATION : Kung Wo Beancurd Factory, Pei Ho Street, Sham Shui Po

LOCATION Duen Kee Dim Sum Restaurant, Chuan Lung Village, Tsuen Wan

LOCATION Wing Heung Cafe, Pau Chung Street, To Kwa Wan

STUDENTS : CHAK Lai Wai, NGAN Lok Yiu, Wong Tak Mei, YEUNG Man Li

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Simon Hsu

LOCATION Kam Lo Dessert, To Kwa Wan

STUDENTS NG Wai Kiu, NGAN Lok Yiu, HONG Chun Ho, Ngan Hei Man, LUI Wing Yan Jasmine, Li Tsz Man TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Charles Lai

STUDENTS PAN Chin Kit, SO Mei Wan, FAN Hoi Ning, Leung Wing Chung, LAW Wing Laam, Lau Cheuk Yin

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Jonathan van der Stel, Kuo Jze Yi

STUDENTS : CHAN Nga Yee, Lau Ho Fai, NG Sze Wing, Yuen Ching Man Jane

TUTORS : Michael Chan, Jonathan Van der Stel

STUDENTS CHEUNG Man Ka, TAM Wan Ting Wylie, WONG Hon Ting Harry, Li Wing Yan Charlotte TUTORS Anneli Giencke, Dr. Charles Lai

STUDENTS : MA Chi Fun Javas, SO Mei Wan, Leung Sin Yan, Chuk Chi Wai Vincent

TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Sunny Choi, Hoi Chi Ng

STUDENTS : GONG Yanni, CHAN Wing, LAI Yuen Ching, HONG Chun Ho

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Simon Hsu

LOCATION : Chen Zai, Nga Tsin Wai Road, Kowloon City

STUDENTS HUANG Yongqi, CHENG Pak Ki Rex, KO Wai Yu, Chan Mei Kee Angel

TUTORS Michael Chan, Jonathan Van der Stel

LOCATION : Hung Wan Cafe, Shang Hai Street, Mong Kok

STUDENTS KWAN Yee Ting, KWON Youngsoo, LIEW Chi Him, POON Kei Yau

TUTORS Anneli Giencke, Charles Lai

LOCATION Star Cafe, Champagne Court, Tsim Sha Tsui

STUDENTS : LAI Suen Yi, HONDA Kensei, YU Ka Ho, KAM Long Yin Brian

TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Sunny Choi, Hoi Chi Ng

LOCATION Yuen Mei Desserts, Wu Kwong Street, Hung Hom

STUDENTS LAU Oi Yu, LUI Wing Lok, CHEUNG Yee Man, NGAN Hei Man

TUTORS : Anneli Giencke, Charles Lai

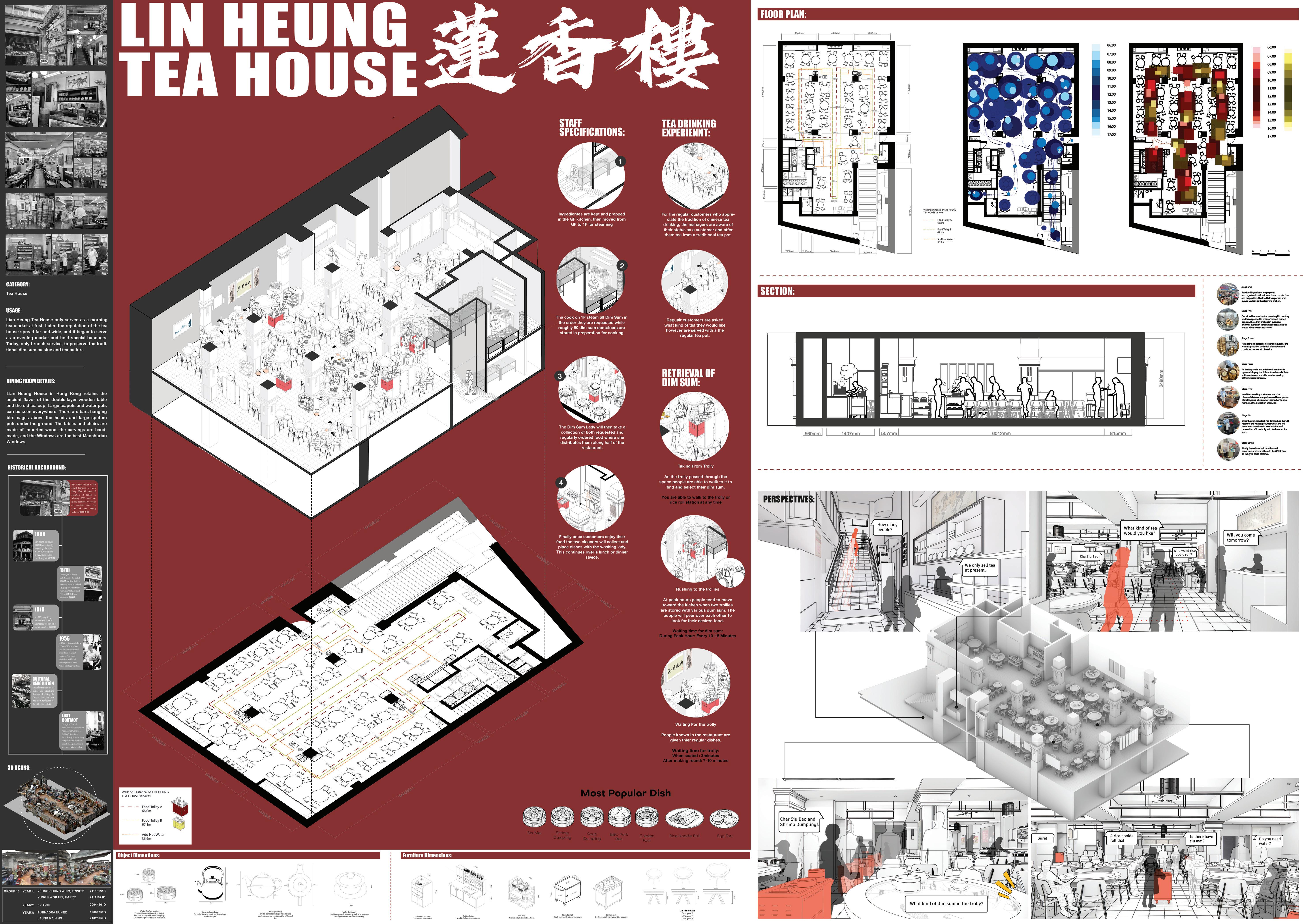

LOCATION : Lin Heung Tea House, Aberdeen Street, Central

STUDENTS SONG Jiayi, WONG Sin Yi Cheryl, PAN Chin Kit, Lai Tim Yu

TUTORS Michael Chan, Jonathan Van der Stel

LOCATION Sun Shing Chiu Chow Restaurant, Kowloon City

STUDENTS WONG Chun Jun, TAM Hoi Ching, MAK Zhe Wing, KAM Chin Hei, KIM Hyo Jin

TUTORS Anneli Giencke, Charles Lai

LOCATION : Sam Hui Yaat, Sai Ying Pun, Western District

STUDENTS LAU Sin Ting, Chan Michael Kai Lok, DONG Fabian, WONG Chung Ling

TUTORS : Michael Chan, Jonathan Van der Stel

LOCATION : Shia Wong Hip, Sham Shui Po

STUDENTS LEE Ching Yi Sylvia, TANG Yui Ming, FAN Hoi Ning, LO Yuen Man

TUTORS : Anneli Giencke, Charles Lai

LOCATION Wing Heung Bing Sutt, Pau Chung Street, To Kwa Wan

STUDENTS : LU Xiaoxin, WONG Sze Ki, WONG Wing Hei, NG Ka Wai

TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Sunny Choi, Hoi Chi Ng

LOCATION Wing Heung Bing Sutt, Pau Chung Street, To Kwa Wan

STUDENTS : LU Xiaoxin, WONG Sze Ki, WONG Wing Hei, NG Ka Wai

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Simon Hsu

LOCATION : Mido Cafe, Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei

STUDENTS TSANG Tiffany, WONG Pak Yiu, CHAN Man Hiu, Li Ka Man, CHOW Tom

TUTORS : Michael Chan, Jonathan Van der Stel

LOCATION : Lin Heung Tea House, Aberdeen Street, Central

STUDENTS YEUNG Chun Wing Trinity, YUNG Kwok Hei Harry, FU Yuet, LILLEY NUNEZ Subhadra Devi Dasi

TUTORS Anneli Giencke, Charles Lai

LOCATION Mido Cafe, Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei

STUDENTS MIAO Jiayi, IP Ka Man, YEUNG Chin H

TUTORS Gerhard Bruyns, Sunny Choi, Hoi Chi Ng

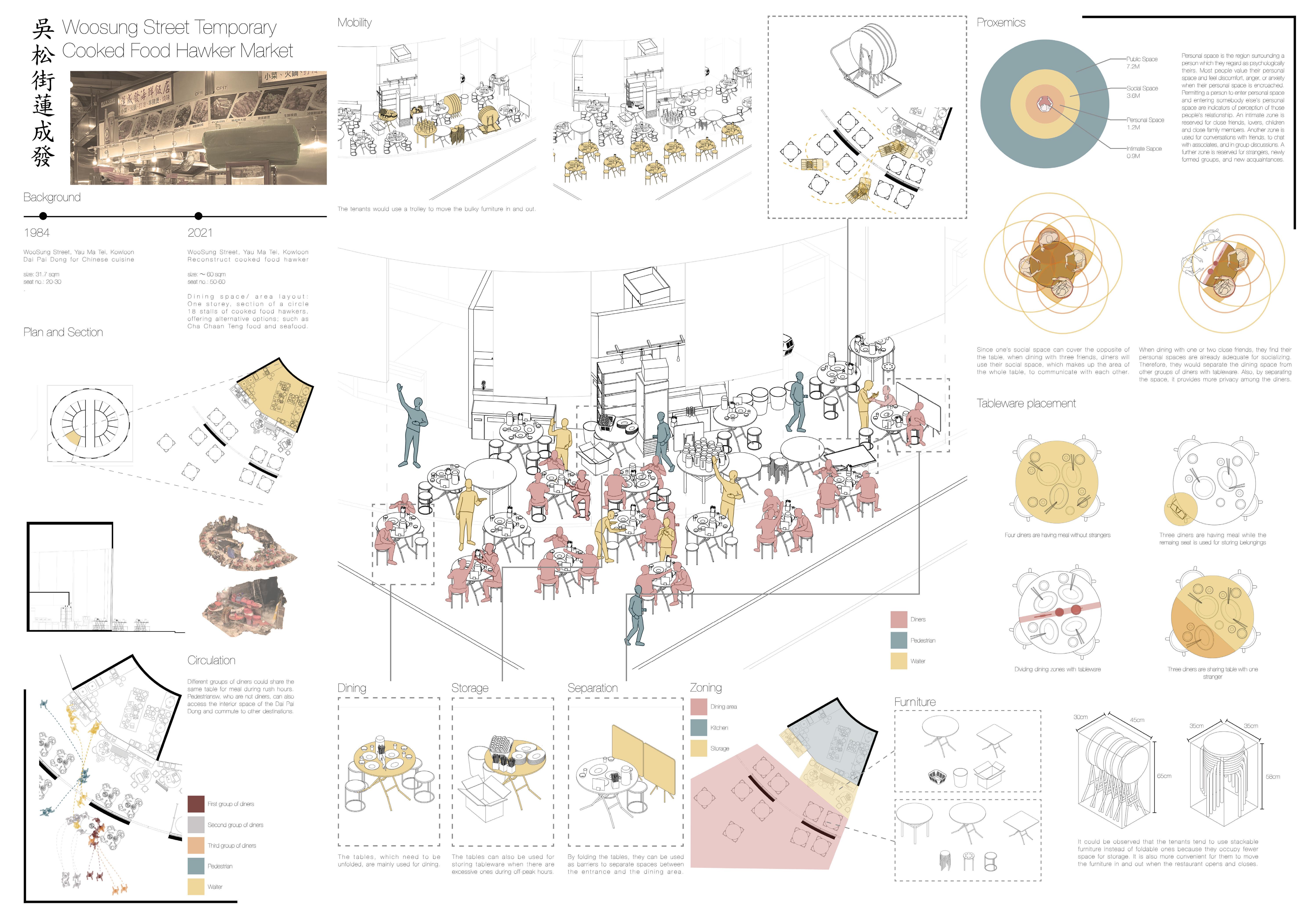

LOCATION Woosung Street Temporary Cooked Food Hawker Market

STUDENTS : SUM Ka Po, CHANG Shu Ting, CHEUNG Wang Yeung

TUTORS Daniel Elkin, Simon Hsu

LOCATION Mushroom Kiosk

STUDENTS : KWON Youngsoo, KO Wai Yu, WONG Mun Yee, WONG Ching Tung

TUTORS : Daniel Elkin, Jonathan van der Stel, Kuo Jze Yi

Dr. Mike Louw and Dr. Sally Farrah, University of Canberra ACT, Australia, 2025

DOI 10.31182/SDIndex.EOUM4628

Marco Frascari (2003: 51) recognises that “...to build and cook are a necessity. However, to build and cook intelligently is the chief obligation of architecture and cuisine”. Several authors have written about the links between food, architecture, and the city (Garrido, Calatrava & Sequeira, 2025; Hagen Hodgson & Toyka, 2007; Hurst and Lawrence, 2003; Louw, 2014; Martin-McAuliffe, 2016; Robinson, 2015) in relation to considerations such as ingredients, production, community, proportion and measurement, sensory perception, and poetry, but the question is what it means to build and cook intelligently today in the face of issues such as climate change, rapid urbanisation and migration, environmental damage and resource depletion, health, disappearing heritage, and rising inequality.

Time, place, and identity are also important considerations for food and architecture according to Hurst and Lawrence (2003: 356), and Marco Frascari echoes this when he writes that “If Kenneth Frampton is correct, in advocating critical regionalism in architecture, a supreme circumstance for architects to develop such intelligence is to understand fully the relationship between regional foods and regional buildings. Eating a hamburger in front of Leon Battista Alberti’s Sant Andrea in Mantua precludes the growth of this quintessential intelligence” (2003: 44). Bosco and Joassart-Marcelli (2018) emphasise the importance of the re-localisation of food systems and how food, health, and the local environment are interrelated. The same can be said about architecture. According to Waldheim (2025: xxi), “...heritage species are loci of inherited knowledge about climates, environments, and ecological dynamics essential for agriculture”. Could the same be said for heritage food spaces that are loci for similar inherited knowledge and that embody collective memory? On the other hand, the globalisation of tastes and ingredients are generating a different, global collective memory. The challenge is how to create an equitable and intelligent balance between the global and local ways of cultivating, processing, preparing and consuming food and architecture.

Movement in relation to food can be considered at many different scales: From the subtlest inhalation of a particular smell, the motion of bringing food from the plate to the mouth, the ritualistic movements in the kitchen when preparing food, the movements from kitchen to table, the increasingly ubiquitous delivery of food from where it is prepared to where it is consumed, the transportation of ingredients from where they are grown to where they are processed, and the sometimes difficult

movement of people to other contexts where food memories can make one feel extremely distant from, or uncannily close, to other places and people.

The process of cooking, refilling and selling chestnuts at a Chestnut Stall in Mong Kok, Hong Kong. Image source: Group 17 (Students: TAM Hoi Ching, TAM Wan Ting Wylie, Chuk Chi Wai Vincent, KWOK Tsz Kwan, IP Cheuk Han, and HEO Sur Yun. Tutors: Michael Chan and Mark Panckhurst), Hong Kong’s Gastronomic Interiors Vertical Studio, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 2021.

In the case of food preparation, the processes often determine the arrangement of the spaces, and rituals are re-enacted during different cycles. Musclememory works in parallel with sensory memory to manifest recollections of dishes, places and people, which is similar to the act of drawing. Both processes are non-linear, projective explorations that often rely on tacit knowledge. The architectural drawing’s ability to help us visualise both the physical and the conceptual boundaries through lineweight and linetype is a useful convention through which to document the sensorial “actual and possible worlds of cuisine and design” (Frascari, 2005: 33).

The consumption of food is also prone to ritual, and it is connected to place. Sarah Robinson writes that “Eating has complex ritualistic dimensions that are intimately related to the atmosphere in which the meal takes place” (Robinson, 2003: 150), while Hale’s reading of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s work is that memory and knowledge are situational, which means that they are tied to specific contexts (2017: 21). A memorable food experience in a specific space and time can be greater than the sum of its parts, and Frascari mentions how “the interlaced cosmos of architecture and cuisine” leads to “a metaphysical extension of space” (2005: 36). The metaphysical extension of space can extend into the city and beyond when one considers certain food destinations, markets, carts, or boat kitchens.

While there is a trend towards the re-localisation of food production and attempts towards narrowing the distance between production and preparation, and while mobile food preparation systems such as carts, stalls and boats aimed to bring preparation and consumption closer together, the increasingly ubiquitous food delivery platforms are increasing the distance between the spaces of preparation and consumption again. Considerations of mobility can be extended to lived experience and local movements or journeying. Bosco and Joassart-Marcelli consider young people’s freedom to interact with local food systems as a way of affirming personal identity (2018: 544). Journeying further, or to distant contexts, the foods and buildings that we have experienced can be modified and reformulated into new ones through imagination, which “...cannot only reconstruct something absent, but also can make a re-elaboration of it” (Frascari, 2003: 42). The acute pang experienced upon remembering a meal made by someone who is no longer present can be softened through re-elaboration, even though it will never be the same. Cooking and drawing can both summon memories of people and places. These memories carry an emotional charge, and they involve a type of reexperiencing (Hale, 2003: 21). This is particularly important when considering importance of food for migrants, refugees, and diaspora. Homi K. Bhabha (1993: 169) writes that people may “...deploy the partial culture from where they emerge to construct visions of community, and versions of historic memory,

that give narrative form to the minority positions they occupy” (1993: 169).

There are many power dynamics in the food industry, and Bosco and JoassartMarcelli argue that there is a direct correlation between issues related to food justice and spatial justice, and they go on to state that “...the spatial organisation of our food system might generate uneven environmental burdens, economic inequality, health disparities, or even social oppression” (2018: 541). The spatial organisation of these food systems is influenced by economics, market demands, and trends in the private sector but equally if not more so by governmental planning decisions and responses to “informality” (Joubert, Battersby and Watson, 2018).

Many food spaces, especially traditional food spaces, are disappearing – not only in Hong Kong. There are numerous reasons for this, including factors such as increased competition, rising rents, rising labour costs, and the percentage that delivery companies or online platforms charge for their services. Slimmer profit margins mean that speed, volume or quantity is important, which can be difficult for smaller establishments (Cam, 2023). However, the process might not be linear. Practices are transferred, and as Bosco and Joassart-Marcelli (2018: 541) argue, places are not specific points on a map, but they are locales where “spatially diffused social networks” connect. Bosco and Joassart-Marcelli (2018: 541) refer to David Harvey’s (1996) concept of places as processes when they describe space as something dynamic that keeps on changing, while Price (2000: 33) writes that “ It’s not that buildings should last a long or short time, it’s that they should last an appropriate time, just like food, just like the storage of food, the preparation, the eating and the evacuation”. Garrido, Calatrava and Sequeira (2025: 1) note how food spaces are “in a perpetual process of construction-reconstruction” at different scales including at the city scale, at the scale of intermediate spaces such as stalls and restaurants, and in the home itself where the relationship between the kitchen and the rest of the home is also changing. This might be difficult to accept at times, especially where these spaces are an important part of people’s collective memory. Dishes can be recreated to some extent - possibly slightly different every time - but recreating the space and the experience of a specific dish, chef, server, event, or the experience of having shared it with a particular person can be very difficult if not impossible.

There are often tensions between the need for heritage preservation and development in both food and architecture. Similar to this are the tensions between approaches that valorise the use of local ingredients or materials and those that promote innovation, scientific approaches or the exotic in what Albala and Cooperman refer to as natural or artificial approaches. They write how “The former often draws on indigenous or vernacular sources for inspiration, while the latter employs historicising elements removed from context, and often applied in novel profusion, indeed sometimes with a horror vacui... The former are populist and turn to local affordable traditions. The

latter is elitist, often produced in imperial contexts for wealthy patrons anxious to display the products of their colonial dominions, incorporating motifs and techniques that speak of power and far-flung connections” (2016: 6). However, especially in post-colonial contexts, these binaries and oppositions cannot sufficiently frame the complexities of food, architecture, and the urban contexts that they are produced and consumed in. In Bhabha’s view, “The enunciation of cultural difference problematises the binary division of past and present, tradition and modernity, at the level of cultural representation and its authoritative address” (2004: 51).

As Joubert et al observe, “A city is not an island, and its food system isn’t a discrete or neat web of routes along which our food moves, or along which the people who ship, process, or sell it to us, operate” (2018: 13). There are countless exchanges and encounters in what Bhabha refers to as the third space between binaries. This space can be a productive one, and it can lend itself to different forms of hybridisation and innovation in food and architecture, as mentioned by Hurst and Lawrence (2003: 356), and in what Bhabha describes as “innovative sites of collaboration and contestation” (2004: 2).

In the end, the decisions we make are often about values – not value in relation to cost or quantity, but in terms of what the buildings and foods we consume represent. They should represent a more empathetic and holistic consideration of the planet, people, place, and memory.

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER 3: EXHIBITION AT THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, PLANNING & GEOMATICS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA

Albala, K., & Cooperman, L. (2016). Cuisine and architecture: Beams and bones – exposure and concealment of raw ingredients, structure and processing techniques in two sister arts. In L. Martin-McAuliffe (Ed.), Food and architecture: At the table (pp. 1-14). Bloomsbury Academic.

Bhabha, H. K. (1993). Culture’s in between. Artforum International, 32(1), 167-214. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/apps/doc/A14580143/ AONE?u=unict&sid=AONE&x-id=cb3d26bf

Bhabha, H. K. (2004). The location of culture. Routledge. (Original work published 1994)

Bosco, F. J., & Joassart-Marcelli, P. (2018). Relational space and place and food environments: Geographic insights for critical sustainability research. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8, 539-546. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s13412-018-0521-6

Bruyns, G., Chan, C. C. B., & Elkin, D. (2025). Rewriting traditional in-person environment design with vertical studio: Merging technology and collective inquiry. In International Conference on Learning and Teaching 2025 (ICLT 2025), The Education University of Hong Kong.

Cam, L. (2023). Hong Kong’s disappearing dim sum: Why old-school trolleys and pig liver siu mai are being replaced. South China Morning Post. https:// www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/food-drink/article/3238622/hongkongs-disappearing-dim-sum-why-old-school-trolleys-and-pig-liver-siu-maiare-being-replaced

Frascari, M. (2003). Architects, never eat your maccheroni without a proper sauce! A macaronic meditation on the anti-Cartesian nature of architectural imagination. Nordisk Arkitekturforskning, 2, 41-55.

Frascari, M. (2005). Cooking an architectural happy cosmospoesis. Built Environment, 31(1), 31-37. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.31.1.31.59189

Garrido, D. A., Calatrava, J., & Sequeira, M. (Eds.). (2025). Eating, building, dwelling: About food, architecture and cities. Routledge.

Hagen Hodgson, P., & Toyka, R. (2007). The architect, the cook and good taste. Birkhäuser.

Hale, J. (2017). Merleau-Ponty for architects. Routledge.

Hurst, R., & Lawrence, J. (2003). Eating Australian architecture. In Contribution and confusion: Architecture and the influence of other fields of inquiry (pp. 350-357). Proceedings of the 91st ACSA International Conference, Helsinki, July 27-30, 2003.

Joubert, L., Battersby, J., & Watson, V. (2018). Tomatoes & taxi ranks: Running our cities to fill the food gap. The African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town.

Kocaturk, T. (2017). A socio-cognitive approach to knowledge construction in design studio through blended learning. Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education, 5(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.5278/ojs.jpblhe.v5i1.1544

Louw, M. (2014). “Slow” architecture and its links with slow food. The South African Journal of Art History, 29(2), 137-157.

Mallibhat, K. (2024). Scaffolding models in a project-based learning course—A case study. Journal of Engineering Education Transformations, 37, 796-803.

Martin-McAuliffe, L. (Ed.). (2016). Food and architecture: At the table. Bloomsbury Academic.

Masava, B., Nyoni, C. N., & Botma, Y. (2023). Scaffolding in health sciences education programmes: An integrative review. Medical Science Educator, 33(1), 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01691-x

Osborn, J. M., Kinzie, J. L., Karukstis, K. K., Malachowski, M. R., & Ambos, E. L. (2024). Fostering equitable transformation: Leading structural and cultural change for curricular scaffolding. The Magazine of Higher Learning, 56(3), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2024.2349457 Pea, R. D. (2004). The social and technological dimensions of scaffolding and related theoretical concepts for learning, education, and human activity.

Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(3), 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1207/ s15327809jls1303_6

Price, C. (2000). Time and food: The Kitchen Lecture at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, February 2000. In H. U. Obrist (Ed.), The conversation series 21: Cedric Price (pp. 27-44). Buchhandlung Walter Konig.

Puntambekar, S., & Kolodner, J. L. (2005). Distributed scaffolding: Helping students learn science from design. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(2), 185–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20048

Reiser, B. J., & Tabak, I. (2014). Scaffolding. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (2nd ed., pp. 44–62). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139519526.005

Robinson, S. (2015). Nested bodies. In S. Robinson & J. Pallasmaa (Eds.), Mind in architecture: Neuroscience, embodiment, and the future of design (pp. 137159). MIT Press.

Salama, A. M. (2016). Spatial design education: New directions for pedagogy in architecture and beyond. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315610276

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press.

Waldheim, C. (2025). Foreword: Eating, building, thinking. In D. A. Garrido, J. Calatrava, & M. Sequeira (Eds.), Eating, building, dwelling: About food, architecture and cities (pp. xix-xxii). Routledge.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Yuan, K., Wen, F., & Zhao, J. (2022, April). Study on the appropriateness of the design, use and removal of the instructional scaffoldings in programming teaching—Take Python crawler programming teaching as an example. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 708-717). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

STUDENTS

Au, Choi Shan

Chan, Kai Lok Michael

Chan, Lok Yiu

Chan, Man Hiu

Chan, Wai Sang

Chan, Wing Chau, Mei Yee Cheng, Pak Ki Rex Chang, Shu Ting Choi, Hoi Yan Chuk, Chi Wai Vincent Chow, Hei Kiu Ellie Chu, Ka Lam

Dong, Fabian

Fan, Hoi Ning Fu, Yuet

Gong, Yanni Heo, Sur Yun

Honda, Kensei

Hui, Hin Sing

Hui, Shing Hei

Huang, Yongqi Ip, Cheuk Yan

Ip, Ka Man

Kam, Long Yin Brian

Kim, Hyo Jin

Kwan, Ka Ying Kwan, Yee Ting

Kwok, Tsz Kwan

Kuo, Wai Yu

Lai, Ka Man

Lai, Suen Yi

Lai, Tim Yu

Lai, Yuen Ching

Lam, Yuen Wai

Lau, Cheuk Yin

Lau, Oi Yu

Lau, Sin Ting

Lau, To Lau, Ho Fai

Lee, Ching Yi Sylvia

Lee, Kiu Chor

Leung, Sin Yan

Leung, Wing Chung

Li, Ka Man

Li, Shing Hon

Li, Tsz Man

Liu, Kai Hei Ruby

Lo, Yuen Man

Lui, Wing Lok

Lui, Wing Yan Jasmine

Ma, Chi Fun Javas

Mak, Ho Lam Phoebe

Mak, Zhe Wing

Maria, Anona Sandy Miao, Jiayi Naik, Ankita

Ng, Ka Wai

Ng, Sze Wing

Ng, Wai Kiu

Ngan, Hei Man Ngan, Lok Yiu

Pang, Wai Kwan

Poon, Kei Yau

So, Mei Wan Soong, Tsz Yu Sum, Ka Po

Sze To, Ka Ming Tang, Chi Tat

Tang, Siu Yeung

Tang, Yui Ming Tam, Hoi Ching

Tam, Wan Ting Wylie Tse, Man Yan Tsang, Tiffany Wong, Chung Ling Wong, Lok Ying Wong, Mun Yee

Wong, Pak Yiu

Wong, Sze Ki

Wong, Tak Mei Wong, Wing Hei

Wong, Ching Tung

Wong, Chun Jun

Wong, Hon Ting Harry Wong, Man Li Yeung

Wong, Chin Hei

Yuen, Wing Yan Yung, Kwok Hei Harry Yu, Ka Ho Yu, Ka Wing Yung, Pak Yu

TUTORS

Anneli Giencke

Charles Laiw

Daniel Elkin

Gerhard Bruyns

Hoi Chi Ng

Jonathan Van der Stel

Kuo Jze Yi

Mark Panckhurst

Michael Chan

Peter Hasdell

Simon Hsu

Sunny Choi

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATORS

Dr. Chun Chuen Billy Chan - The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Dr. Mike Louw and Dr. Sally Farrah - University of Canberra ACT

PHD RESEARCHER

Lee Ching Veronica

ASSISTANT

Hui Hin Sing Sam

Font: POLYU Chatham Fourteen March 2025

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Modifications acknowledgement: “This work includes modifications to Vertical _Studios VS_Montage, Scaffold Pedagogies as Knowladge Transfer by Bruyns/Elkin, licensed under CC BY 4.0.”

Layout: HUI, Shing Hei

Cover: HUI, Shing Hei 24/03/2025