5 minute read

International economy

In recent weeks we have seen an emergent banking crisis that had its origins in the coronavirus stimulus packages. The government support and cheap lending saw an influx of deposits for many US banks. They faced a choice to:

1. Originate more loans to take advantage of the capital influx, or

2. purchase higher yielding debt securities (mainly bonds) on the market.

The influx of government support and the recession fears back in 2020 meant Option 1 was off the table. Many banks chose Option 2 and bought higher yielding assets (mainly fixed rate ones such as government bonds and mortgage-backed securities).

This was the scenario besetting Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the largest banking failure (~$US211 billion in assets1) in the US since the global financial crisis. SVB, like peers, had invested its excess deposits heavily in bonds. Ordinarily, if held to maturity the value of these bonds (shown on a bank’s balance sheet as assets) would cover liabilities (customer deposits). When the Federal Reserve (the Fed) lifted rates from a low of 0.08% in January 2022 to 4.1% by December, the market value of these bonds fell sharply To fund customer withdrawals SVB was forced to sell bonds at a loss, which became public knowledge once disclosed in their accounts. By extrapolation, investors soon realised that further withdrawals would crystallise more losses

The situation rapidly spiralled into a classic “bank run” where depositors withdrew funds on mass

This saw US authorities intervene in mid-March to guarantee all deposits held by SVB, and implicitly other troubled banks, to mitigate the risk of further runs on other banks The key risk now is whether this morphs into a more severe financial crisis. While other institutions look vulnerable or have been rescued (cue Credit Suisse2), the overall system appears to be largely intact. We may see other, smaller, banks be absorbed by larger peers, with First Republic Bank being one of the leading candidates. The larger, more regulated institutions such as JP Morgan or Bank of America have more robust capital positions and are far less susceptible to a bank run phenomenon given greater diversification in their customer base. That does not mean this saga is without consequence, however. By reducing the number of lenders, competition is reduced. The concern about profitability could see banks tighten their credit standards as they need to make up for the weaker returns of their asset portfolios. Arguably this is already the case with the Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Survey noting that the largest proportion of lenders are tightening credit standards since early 2020, to levels usually seen in recessions.

Percentage of US banks tightening lending standards to Large/Middle-Market firms (Mar-03 to Mar-23)

1 SVB Financial Group, Form 10-K as at 31 December 2022 https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/719739/000071973923000021/sivb-20221231.htm

2 Credit Suisse stocks and shares, all you need to know, Forbes, 27 March 2023: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/au/investing/creditsuisse-shares-all-you-need-to-know/

The withdrawal of credit makes it harder for businesses to reinvest in new staff and equipment, dragging on investment spending and overall economic growth as a result. It could also see debt-dependent sectors such as property struggle as they look to refinance their borrowings. We have begun to see stresses emerge in this space with a landlord owned by fund manager PIMCO defaulting on $US1.7 billion in mortgage debt held against office properties3 More loans are falling due in the year ahead which could see more defaults ensue with consequent credit losses impairing bank profitability and contributing to more conservative lending (leading to further credit tightening).

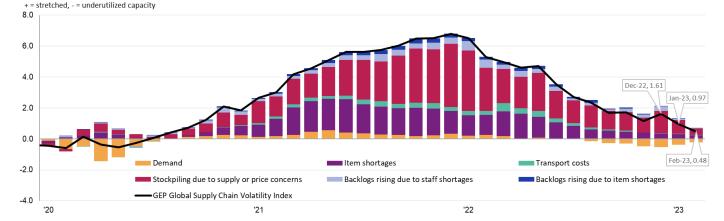

We see this saga as a net negative for the US economy to the extent it has spilled over to other markets (e.g. Credit Suisse) It also poses a negative for the broader global economy for similar reasons in our view. In addition, we are in a period where central banks have continued to tighten. In March, the European Central Bank (ECB) lifted rates by 0.5% while the Fed, despite the unfolding banking crisis, increased by 0.25%4 Nevertheless, global supply chain pressures have eased substantially suggesting further rate hikes are increasingly less likely.

GEP Global Supply Chain Volatility Index Breakdown (Jan-20 to Feb-23)

Sources: S&P Global, GEP

The picture in services is decidedly more mixed. Globally this sector has fared better than many have expected with recovery from lockdown restrictions and redistribution of consumer spending away from goods both being important drivers. The JP Morgan Global Services PMI, a broad measure of services sector business output, was 52.6 in February implying growth versus a much more modest 50 reading for manufacturing (readings above 50 imply expansion, readings below imply contraction) In the US, prices for core service, excluding the cost of housing (the blue line), are running at elevated levels of 6.1% growth for the year to February (versus a pre-pandemic average of 2%-2.5%) This poses a challenge for the Fed as it implies there is still work left to sufficiently cool demand and ensure headline inflation (the black line) does not remain at a level permanently above their long-term target of 2%.

US inflation – Headline versus Core services excluding shelter (Feb-13 to Feb-23)

3 Two office landlords defaulting may be just the beginning, AFR, 22 March 2023: https://www.afr.com/property/commercial/two-officelandlords-defaulting-may-be-just-the-beginning-20230320-p5ctrv

4 European Central Bank hikes rates despite market mayhem, pledges support if needed, CNBC, 16 March 2023 https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/16/ecb-rate-decision-march-meeting-lagarde-announces-new-rate-hike.html compounds the economic damage as a greater proportion of income is diverted towards borrowing costs and away from consumption or investment spending.

It also has implications for credit growth. The creation of new credit is a part of a healthy economy as new lending goes towards projects and assets that should help expand the economy over time. A higher cost of borrowing however raises the hurdle on the returns that these investments need to generate to be viable. If we look at the implication for the US and Eurozone, both economies are seeing negative credit impulses

Given the scale of the US and Europe’s contribution to the world economy, this would suggest weaker global growth in the year ahead.

Bloomberg credit impulse by region as a percentage of GDP (Mar-13 to Mar-23)

Overall, this is shaping up to a decidedly negative world view. The outlook in China however is somewhat less pessimistic. The economy is emerging from self-inflicted harm with the scale and length of its coronavirus restrictions. Business surveys are pointing towards stronger demand and consumer spending is picking up for the first time in several months with retail sales for January-February rising 3.5% year-on-year versus a fall of 1.8% in December 2022. Authorities have also set a growth target of 5% for 2023, a sizeable recovery from the 2.9% recorded in 2022 but below consensus expectations for above 5%5

On the policy front however there has been a marked reluctance to revisit past approaches that relied on stimulating investment in infrastructure, property and other fixed assets. That was the key to fuelling booms for commodities and manufactured goods in the past that benefitted exporters in Australia (mining) and Europe (industrials) respectively It appears this recovery will be more muted than past episodes. A modest expansion of the fiscal deficit from 2.8% of GDP in 2022 to 3% in 2023 also supports this perspective. While China will likely be a net positive for global growth this year it will not be the support some countries might have counted on

Conclusion

In summation we have a world beset with several major challenges. First, a banking crisis that raises the prospect of subdued credit creation and may still prompt new financial risks. Second, an unfavourable policy backdrop with central banks continuing to hike and look to slowdown economic activity to combat still elevated levels of inflation. Finally, there is a lack of meaningful offsets to support a more positive outlook. While China is a significant driver of the global economy, we do not believe it will be enough to change the trajectory of our outlook which is for weak growth and heightened recession risk. Caution remains advised in the near-term.

5 China sets modest growth target as economic risks persist, Bloomberg, 5 March 2023: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/202303-05/china-sets-modest-growth-target-as-economic-risks-persist?leadSource=uverify%20wall