Newsletter of the pine ridge association

Henry W. Coe State Park

Greetings from the PRA Board of Directors! I am honored to write to you as your new PRA president. I take the responsibility seriously, but I also intend it to be lots of fun. Dan Benefiel has led us well through his two tenures in this position, and I am both glad to have him remain on the board and worried about filling his very large shoes.

The first thing I would like to do is to welcome you to the 50th year of the Pine Ridge Association! It all started in 1975 in a Morgan Hill living room with Dave Hildebrand as the first president. The Ponderosa started four years later and the rest, as they say, is history. We started 2025 by finalizing our online elections, and I thank all who voted. The overall participation rate was 46%, putting Jeff and Dan on the board for another three years. We are soon going to release our five-year strategic plan. We are reviewing our annual events to see what we should stop, start, or change and how to better reach people who may want to attend. We are ramping up for another big construction project and the interpretive panels around the main VC should be deployed. We are also looking at how to responsibly use some technology in the park - such as automatically reporting spring flow rates to the water resources page.

My last first words are an invitation to all of you to help the PRA grow, in order that we may do more for the park we love. Materials and services we need for our projects and events keep getting more expensive, and we want to keep doing them. Perhaps you have a neighbor or friend who enjoys nature or hearing your stories about the park. Invite them to join ! It’s only $20 per year and it comes with both this newsletter and the knowledge that they are helping PRA achieve its goals by making the park a better and more enjoyable place to go.

Our board meets bimonthly, and all members are welcome to join our discussions. For details on our next meeting, feel free to email Al Henning

Joseph Belli is our guide to this illusive and misunderstood predator and proves even a short life can have its benefits.

Teddy Goodrich delves into the history of land surveying in Coe and the challenges of drawing straight lines in rough terrain.

We revisit Barry Breckling’s foray into the mysterious and varied world of mushrooms A common sight in winter.

Ponderosa Prescribed Burn

Chris Weske reports on December’s prescribed burns and ongoing efforts to protect the park’s Ponderosa pines.

by Joseph Belli

If you polled Coe’s visitors and asked which of the park’s animals they’d most like to be, I wouldn’t be surprised if mountain lions topped the list. They’re symbols of grace, athleticism, and power, perched atop the pinnacle of the food chain, with nothing to fear besides people.

Mountain lions have the largest distribution of any New World mammal, from northern British Columbia to Patagonia. The fossil record has them arriving in North America 300,000 years ago, though at one point they were extirpated, and the continent was subsequently recolonized with mountain lions from South America. They coexisted beside a number of larger predators lions, saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, hyenas, and giant short-faced bears. Their ability to climb trees surely served them well in that company. They outlasted all those adversaries, and by the time Columbus set sail they were found from coast to coast. But colonists and cougars don’t mix, for settlers placed bounties on mountain lions beginning in the 1600s. Those bounties, along with habitat transformation, led to mountain lions disappearing from the eastern half of the continent by 1900, save for a remnant population in Florida’s Everglades.

Out west, mountain lions were similarly targeted, and California was no exception. In 1907, the state instituted a bounty, hiring hunters to kill as many as they could. The bounty program lasted 56 years and claimed the lives of over 12,000 mountain lions. Mountain lion math can be sobering. How much that impacted the population is hard to quantify; by the time the bounty ended in 1963 it was estimated that there were 600 mountain lions remaining in California.

But estimating mountain lion numbers is notoriously challenging, and who can say how accurate that figure was. All that was certain was that mountain lions survived the onslaught, though in reduced numbers.

Less than ten years after the rescission of the bounty the pendulum swung in the opposite direction. In 1972 mountain lion hunting was outlawed in the state. That edict was fortified at the ballot box in 1992, when voters passed Proposition 117, which elevated mountain lion status to that of Specially Protected Mammal and earmarked annual funding for habitat protection. That protection remains in place mountain lions can’t be hunted, although those deemed a problem to livestock, pets, or human safety can be killed through the issuance of a depredation permit.

* * *

It might be tempting to view mountain lions as simply larger versions of bobcats, though mountain lions are more closely related to cheetahs and jaguarundis. There are plenty of parallels: males are

considerably larger than females the former might exceed 150 pounds, while the latter often weigh less than 100 pounds. Both bobcats and mountain lions establish home ranges where those of males are much larger than those of females, and where males are intolerant of each other but willing to share territories with females. Both cats are ambush hunters that stalk rather than chase their quarry. Mountain lions take larger prey, and in California deer constitute the primary target. If the old saying “You are what you eat” has merit, it could well apply to mountain lions. Consider their appearance: their tawny coat and white belly align with those of deer, and the resemblance even extends to the black-tipped tail. The range maps of the two species in the state are practically identical, yet mountain lions show flexibility in their diet, consuming elk, wild pigs, and smaller fare such as raccoons and rabbits. There’s some livestock depredation, and they’ll pick off pets as well. They also kill bobcats and coyotes, less for food than as

competitors, and on extremely rare occasions, mountain lions take people as prey. There’s a lot of hysteria surrounding mountain lions, but when you consider that thousands of people live and recreate in mountain lion habitat every day without incident, it’s clear the odds of being attacked are very remote.

It’s been posited that adult mountain lions need to eat a deer a week to survive. Females with kittens (which remain with their mother for 12-18 months) require the most food, while non-breeding females require the least. Those considerable food requirements explain why mountain lions can never be considered numerous there’s not enough food out there to maintain a dense population. Even where they’re common, mountain lions are spread thin.

Mountain lions also regulate their own numbers. Males fight over territory, and sometimes those fights are fatal. Young males are particularly vulnerable. Such transients, hoping to establish a territory of their own, sometimes wind up in suburbs and even cities, where they make a news splash but often pay with their lives. Some are relocated to the countryside, where they may be unlucky enough to run into another resident male. Others don’t get even that chance, winding up shot by authorities who have little training in wildlife management. The lucky dispersers who avoid humans and other males sometimes travel extraordinary distances, occasionally exceeding 300 miles. Several years ago a mountain lion was discovered dead in Connecticut; its DNA matched those of lions from the Black Hills in South Dakota, the closest known breeding population outside of Florida.

Today, the mountain lion population in California appears reasonably healthy, but because they’re wideranging and spread out, they’re vulnerable to habitat fragmentation, where highways and sprawl block

movement between populations. If populations become truly isolated, they’re doomed to inbreeding and eventual extirpation.

The life of a mountain lion has its perks: being able to jump nine feet in the air, climb trees with ease, and cover ground almost effortlessly. They have nothing to fear from any other wild creature, and they spend most of their time resting. Sounds pretty sweet.

And when they’re not resting, consider this: during breeding season mountain lions have been known to mate copiously, up to 70 times a day. Who do they think they are, Wilt Chamberlain? Hugh Hefner? How can that possibly be? Why, that’s my equivalent of a… month …year...decade …never mind. Mountain lion math can be sobering in more ways than one. Still, 70 times a day…who wouldn’t want to be a mountain lion?

On the other hand, the mountain lion lifespan is shockingly short. Your housecat may well live twice as long as a male mountain lion, very few of which will live ten years. Those oak woodlands can be a jungle out there, for males live in a cat-kill-cat world. Females have it a little easier, at least in terms of intra-specific aggression, but all mountain lions need to eat, and eating means killing, which poses considerable risk,

which thrive on low-risk prey such as rabbits, ground squirrels, and birds, mountain lions routinely take down prey larger than they are. Large herbivores are not defenseless a well-placed kick can leave a mountain lion mortally wounded, and even if the injury isn’t fatal, a broken bone or a wound that becomes infected could impede a lion’s ability to hunt and result in starvation.

On second thought, I think I’ll pass on being a mountain lion, though 70 times a day isn’t easy to turn down. And perhaps it’s merely sour grapes, but isn’t that just a little too much of a good thing?

If you’re curious about condors and want to know what it’s like working to restore this magnificent species, my new book “Beneath a Black and White Sky” is for you. It’s a monthly account of the year 2017 within the central California condor flock at Pinnacles National Park. I describe the challenges of field work, the controversies surrounding recovery, and highs and lows of working so closely with these incredible birds. Proceeds support condor conservation; you can purchase it on Amazon, or, better still, the PRA bookstore in the Visitor Center! PRA members enjoy a 15% discount on items sold at the Coe Ranch Entrance Visitor Center.

by Teddy Goodrich - Pine Ridge Association Historian

The PLSS - Public Land Survey System divides public land into uniform parcels and was used with the Homestead Act of 1862 to convey land from the federal government to private individuals. This survey system has its origins in the Land Ordinance of 1785 which defined the process of creating townships and sections by which public land west of the Appalachians was surveyed and sold.

In 1851 Colonel Leander Ransom, Deputy Surveyor General, established the Mt. Diablo base and meridian thus creating a survey grid of townships, north and south and east and west of Mt. Diablo. The Mt. Diablo meridian covers much of California and all of Nevada.

A township is a square six miles on each side containing 36 sections, each section containing one square mile. Sections are numbered from right to left, beginning in the upper right corner, 1 through 12, then from left to right in the following line, and again right to left. Repeat for a total of 36 sections. A section contains 640 acres. A ¼ section contains 160 acres, the amount of land the original Homestead Act allotted to a prospective settler.

These original surveys were made using a Gunter’s Chain, an historic measuring device invented by Edmund Gunter, an English mathematician, in 1620. One chain is 66 feet long.* A survey field crew usually consisted of a deputy surveyor, two chainmen, an axe man, and in open country, a flagman. The survey crew

Coe is in all or part of the following townships: Township 7S, Ranges 5-6E; Township 8S, Ranges 4-6E; Township 9S, Ranges 4-6E; and Township 10, Range 5E. As indicated on the map, the Coe Ranch Entrance straddles Townships 8S and 9S.

camped in the backcountry and often relied on settlers for food for themselves and their horses and mules. The field notes often note what they purchased, how much they paid, and from whom they bought it.

G.H. Smith

5 bales hay @ $2.25

While a survey grid of townships north and south of an established base sounds easy and logical when drawn on paper, the reality of a survey within the park was a huge challenge. How do you measure a terrain that boasts an elevation gain and loss of several thousand feet within a few miles or a landscape that is often covered with thick, impenetrable brush? Early surveys were often incomplete or fraught with error. In 1853 Sherman Day surveyed the “Second Standard South,” an east-west line 48 miles south of Mt Diablo. Approaching from the west he stopped 1 ½ miles west of Coe headquarters. In 1858, Henry Washington extended this line east through the park, but his section

corners were all incorrect, a little short of the standard mile. A survey of the area northeast of Gilroy Hot Springs was abandoned when the surveyor in charge, Charles Healey, decided the landscape was simply too rough and not worth surveying. It was not until A.T. and Charles Herrmann surveyed the area that now comprises the park (and beyond) that an adequate and reasonably accurate survey was completed between 1880 and 1882.

Some years ago, several volunteers and the then unit ranger Barry Breckling became interested in finding remnants of the old surveys: witness or bearing trees and section corners that were marked with piles of rock or an engraved rock. They found that less permanent ways of marking section corners, stakes and piles of earth, were no longer visible. Of the bearing trees, usually only the oak trees survived. Attached are a few photos of what they found.

All the survey maps of Coe are available online at BLM GLO records. The same website can be used to find homesteaders and homesteads that once existed in the park.

I am indebted to my late friend and fellow volunteer, Lee Sims, for much of the information in this article. Lee was a dedicated and meticulous researcher.

*Eighty chains equals one mile – 5,280 feet. Ten square chains equals one acre. Country roads were traditionally one chain wide.

This is a bearing tree, location unknown. The blaze, made about waist high with an ax, identifies it as a bearing tree. Bearing trees were located near section corners and their species and location noted in the field notes.

This is a small portion of the 1882 map of T8sR4e. According to this map, “Jordan’s corral and log barn” would have been located near the current backcountry gate at the start of Manzanita Point Road and Monument Trail.

by Barry Breckling

There certainly isn’t much blooming in the winter but you can find rain flowers...better known as mushrooms to most people. Mushrooms are a type of fungus (fungi or funguses are the plural forms of the word). Fungi include such things as yeasts, molds, rusts, mildews, athlete’s foot, and of course, mushrooms.

The mushrooms we see are not so much the plant as they are the fruit of the plant. The plants consist of a web of root-like material called mycelium. Mushrooms pop out of the ground to release the “seeds” of the plant, the spores. These spores are so small that it would take about a dozen to span the width of a human hair, and they can be so numerous that a typical mushroom can have hundreds of millions of spores.

Typical shaped mushrooms often have gills that hold the spores, but others have pores. Some mushrooms such as puffballs and earthstars have spores contained within their rounded bodies that are dispersed when the outside covering ruptures. Some other shapes of mushrooms, such as teeth, jelly, coral, cup, and saddle, disperse their spores in other manners.

Mushrooms can be parasites, feeding on living organisms, but are more commonly saprophytes, feeding on dead organic material.

The mycelium break down complex organic compounds into raw materials that plants can use. Without mushrooms, we would be buried in

mountains of organic material. Mushrooms also have what is called a mycorrhizal relationship with many, probably most, higher plants.

Structures in the mycelium link with the roots of plants and form a symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationship. The plant provides moisture and carbohydrates to the mushroom, while the mushroom helps the plants absorb phosphorus and inorganic nitrogen. This relationship also gives the plants increased protection against certain pathogens. Without this relationship, plants do poorly.

Put on your raincoat and get out there and see those beautiful rain flowers this winter. You can get started by picking up a mushroom guide. The two I’d suggest are All That the Rain Promises and More, and the mushroom bible, Mushrooms Demystified, both by David Arora.

Publisher’s Note: Mushrooms are truly fascinating organisms. They play an important role in the park’s ecosystem, and thus, are protected. While many mushrooms may be edible, some are deadly poisonous. Therefore, we discourage foraging for wild mushrooms in the park. Instead, take some great pictures, share them with your friends, and learn all you can about mushrooms!

by ChrisWeske

On December 10th and 11th, 2024 prescribed burns were conducted on Pine Ridge. Two small plots were burned this year. The Ponderosa Loop plot at 7.5 acres and the Monument Trail plot 4.25 acres. The ponderosa loop area last saw fire as part of a prescribed burn in November 1992. Prior to that, the area experienced the Pine wildfire on August 21, 1991, and before that, the Star Wildfire in 1966.

The Monument Spring Plot at 39.75 acres and the Ponderosa South plot at 31.5 acres were not burned this season due to a lack of resources.

These plots are sub units of a pending 1,000 acre burn plot which will be conducted with CalFire. This larger plot will be a repeat of the November 1992 burn.

Our local Diablo Range Distract crew was supplemented by personnel from the Monterey District, Santa Cruz District, Central Coast Prescribed Burn Association, Tamien Nation Tribe, Ama Mutson Tribal Band, and our Coe volunteers. Stanford University researchers set up air quality monitoring equipment around the burn plots.

Fire is a natural component of the environment. One of the goals of the program is to re-introduce that component. An important element of the program is evaluation. Vegetation monitoring plots and photo

points are in place for each of the plots. Portions of some of the plots will be re-burned at different intervals to evaluate the vegetation response and try to identify an appropriate fire return interval for this area.

An additional goal of the burns in this area is to reduce the fuel loads under the Ponderosa Pine, to help protect them from future fire. The 1991 wildfire killed several mature Ponderosa Pine. Ponderosa Pine benefits from periodic burns but does not tolerate intense fire climbing into the tree crown. Periodic lower intensity fire will help protect these trees.

Our Sector Natural Resources staff and interpretive staff will be conducting public interpretive talks and hikes through these burn plots this spring. Please come join a walk and see what flowers are coming up this spring. We would also like to have volunteers come out to see what we are doing, and then be able to assist with hikes.

Visit coepark.net for the latest information about all activities.

Dowdy Ranch Entrance Reopening - February 15 (weather-permitting).

For more information, visit the Dowdy’s official webpage: https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=25820

Bring the family and join us at the Hunting Hollow Entrance for a scavenger hunt near the creek. Discover what animals and plants live there. Have you seen a newt before? What do you know about sycamore trees? Grab your raincoats and rubber boots and help us answer these questions! Kids, bring your bikes and helmets and ride the Mountain Biking Challenge Course for Kids! Parking is $6. For details: https:// coepark.net/park-events/

Coe uniformed volunteers are offering a guided backpacking trip into stunning areas of the park that few visitors ever see. This will be a rare opportunity to access the trail junction at Kaiser Aetna and County Line Roads by vehicle. From there, we will backpack deeper into Coe’s backcountry and spend the night in utter solitude. Registration required and space limited. For details: https://coepark.net/events/spring-in-orestimba-guidedbackpacking-trip/

For one weekend this spring, park staff will open the gate at Bell's Station on Hwy 152 east of Gilroy and allow registered attendees to drive along Kaiser-Aetna Road beyond the Dowdy Visitor Center. Hikers, mountain bikers and equestrians have a unique opportunity to see and enjoy an area isolated from the park's Morgan Hill entrance by long distances and rugged terrain. The east side of the park has beautiful spring wildflowers, great fishing, and scenic trails. Registration is required and usually begins in early March at https://coepark.net/events/backcountryweekend/

by Sue Dekalb

This year the new volunteer springs training took place at Monument spring. The old spring box was falling apart and most of the water was going around the box and into the trough over the ground, dragging all the silt and debris with it. The sedge and other debris were breaking the box apart making it impossible to fix the spring without digging out all the old box and growth that had formed around it.

The flow from Sierra View Spring was pretty slow because the outflow pipe was clogged with debris. There was also a lot of plant growth in the trough that was breaking apart. Bobby Barnett and I cleaned the debris out and got the water flowing again.

While out on Springs Trail doing the Trails Training, we did work on a few springs along the way. One spring was Blackberry Spring which is mostly a seep under a wooden bridge. We wanted to locate any spring box that might have been there long ago when the ranchers depended on that spring. We hacked out a bunch of blackberry bushes that followed the water flow up to the box. We also cleaned out the debris and located a nicely built brick spring box that had long since been forgotten. There was also a lot of old rusted out piping which we removed from the seep. The debris under the bridge was cleared out so the water could flow down the hillside. This spring could be developed again and a trough added for the wildlife. We also cleaned out the debris from under the Arnold Spring bridges that were placed on Springs Trail so

people would not have to walk through the water and mud from that spring. Lastly we brushed the trail that takes you to Plume Spring which is hidden behind a large tree down the hill a bit from the Springs Trail.

Much planning and discussion has been done to finally get the Live Oak Spring piping underground. The PRA has agreed to pay for some materials but most of the money will come from the State. The entire waterline will be buried in Live Oak Spring Road and Trail from the spring to Coit Road. The rest of the waterline from Coit Road down to Pacheco Camp is in pretty good shape and will be left alone. The timing for this project will begin sometime around the Backcountry Weekend work that is done by the heavy equipment operators since some of the

There has been a lot of activity since the last Ponderosa. We have been trying to keep up with all the trees that have fallen down on the trails and roads. We needed to clear some trees from Elderberry Spring Trail and from Rock Tower but Jackson Road was covered by high grass. Hollister Hills SVRA Natural Resources staff brought weed whackers, and along with myself, weed-whacked the entire 1.4 miles of Jackson Road. We were then able to drive to Elderberry Spring Trail so we could remove a large oak that had fallen on the trail. Volunteers brushed parts of Elderberry Spring Trail, Rock Tower Trail, and Grizzly Gulch Trail.

We had to go back out to Jackson Road to clear a large tree that had fallen on Rock Tower some time ago. The tree had fallen right on the trail near Pond C15. There had been a well used social trail around the debris for at least a year. We had hoped to clear the tree from the original trail but we were unable to clear the entire tree. It had become quite hard and very difficult to cut. We blocked off the social trail and did

equipment will already be in the park.

Remember, if you go out into the park, please send a report to water-reports@coepark.net. Please note if there is a critter stick and critter stick protector in the trough (if there is one). Unless the inflow is dripping or trickling in, you should plan on measuring the flow for your report.

The new volunteers who took the training were Sam Leen, Brian Leen, and Nabeel Al-Shamma. The other volunteers who helped us work on springs were Bobbie Barnett, Walter Dunckel, Andy John, Prithpal Khajuria, Mike Otte, Art Pon, Herveline Sartori, and Mary Williams.

the best we could to get the trail back where it belonged. Not really sure how successful we were but we made a safe trail to get through the area. We also cleared trees off Wasno Road, Live Oak Spring Road, and Crest Road.

Volunteers cleared brush and three trees off Coit Ridge Trail the next week. The trees had been on the trail for almost a year.

Next we went back to Cross Canyon Trail as four trees had come down in the canyon and on the trail after a very windy weekend. There are so many dead trees in that canyon from both big fires, we will be clearing downed trees for years to come. There was also a report of a downed tree on George Milias Trail and four trees down near the intersection of Kelly Cabin Canyon Trail and Cross Canyon Trail. We also did some brushing along George Milias Trail and Cross Canyon Trail. There were actually closer to 10 trees in Cross Canyon that needed to be cleared as more had come down after the initial report. There were also some hazard trees that needed to come down.

The volunteers went out to Coit Road next and did some brushing on the road from above Kelly Cabin Canyon all the way to Mahoney Meadows Road. The brush was encroaching on the road and also growing in the road.

The next trip found us back at Coit Road clearing trees and brush from Mahoney Meadows Road down to Anza Trail junction. We also removed a couple of trees from Cowgirl Trail and another one from Heartbreak Trail. Lynne Starr and I went out later and finished clearing Coit Road and also removed a tree on Wasno Road.

The next trip we cleared many downed trees in the park. We sent crews in three different directions so we could clear as many trails as possible. One crew went down Cross Canyon and cleared ten downed trees between Coit Road and the creek. Another crew went down Heartbreak Trail and Grapevine Trail to remove

several large trees. The third crew cleared trees from Fish and Game Trail, Steer Ridge Road, Wagon Road, Kelly LakeTrail, and Grizzly Gulch Trail.

The next weekend was the new volunteer Trails Training up at HQ. We went out on Springs Trail and did brushing, some tread work, and some springs work. One of those projects involved clearing out the blackberry bushes at Blackberry Spring. In the process we uncovered and cleaned out the old brick spring box up the hill from the bridge. All the blackberries in the path of the water flow were removed and debris was cleaned out from under the bridge. We also cleaned out all the debris from under the wooden bridges at Arnold Spring and cleared the path to Plume Spring.

The next week found us removing several trees on Phegley Ridge Trail, several from Elderberry Spring Trail, Coit Ridge Trail, and some brushing on Coit

Dam Road. We also cleared some hanging tree branches encroaching on Bowl Trail and he also did some much needed brushing there.

The final week of Trail work involved clearing trees on Mahoney Meadows Road, several trees on Willow Ridge Trail along with some much needed hedging and some tread work there, several trees from Rock Tower Trail, and one large one on Anza Trail that was blocking the entire trail.

Remember, when you go out into the park, please send a report to trail-reports@coepark.net. We can’t clear the hazards if we don’t know about them.

Thank you to the following people who helped with one or more of these projects: Coe Volunteers

Laura Bonnin, Liz Brinkman, Lee Damico, Walter

Dunckel, Virginia Goldwasser, Chris Howard, Jodie and Linda Keahey, Prithpal Khajuria, Bryan Murahashi, Mike Otte, Pete Palmer, Art Pon, Eric Simonsen, Lynne Starr, John Thatcher, Jesus Valdez, and Mary Williams; Hollister Hills SVRA Natural Resources staff Chris Arredondo, Victor Beaudoin, Joseph Bocanegra, Dan Daley, Jocelyn Fierro, Megan Fulford, Olivia Gonzalez, Noah Hidalgo, and Nano (Emiliano) Quintero; Tamien Nation representatives Nico and Jonathan Costillas; and Coe volunteer trainees Brian Leen, Sam Leen, and Nabeel Al-Shamma.

by Michael Newburn

The Mounted Assistance Unit (MAU) conducted another successful annual Search & Rescue (SAR) training in November. The training was enhanced by the participation of not only MAU members, but members of Coe’s Foot Patrol and members of the Santa Clara County Parks Trail Watch Volunteers. There were a total of 23 volunteers participating in the two-day training.

The first day was an introduction/refresher on the Incident Command System (ICS). ICS is a standardized approach to the command, control, and coordination of emergency response providing a common hierarchy within which responders from multiple agencies can be effective. The understanding of ICS is important for volunteers who might be involved in a SAR event, especially when multiple agencies are involved.

The second day was a field day with a mock SAR.

Volunteers were broken into two groups; Bicyclist and Equestrians assigned to a hasty search, and Foot Patrol members assigned a grid search. A hasty search is a quick, organized search for a person or people who need immediate help. The equestrians and bicyclist were broken into search teams to search assigned trails. There were two teams of two equestrians, and one team with two bicyclist and an equestrian.

Sixteen Foot Patrol members conducted a grid search to look for clues from the hypothetical ‘lost person’ at the last known location. A grid search in SAR is a systematic method of searching an area by dividing it into a grid pattern.

The MAU was pleased with the outcome of the training, and are especially thankful to the Coe’s Foot Patrol members and Santa Clara County Parks Trail Watch Volunteers for their participation.

by Margaret Mary McBride

Long time uniformed volunteer Lois Phillips has passed. Lois was a Coe Park volunteer for 32 years. She volunteered at numerous events and donated more than 3100 hours to the park. She enjoyed engaging with visitors and often worked at the Visitor Center. During a snowy Sunday a few years ago, while the staff was outside managing the huge number of cars waiting to enter the park, she kept the Visitor Center open with a fire in the stove and hot chocolate for the visitors. Lois was known for her love of her large extended family, love of the park and love of square dancing. She will be missed.

by Rick Casey PRA Treasurer

In 2024, our bottom-line net income for the year was $32,705; this represents a 230% improvement over 2023 net. This improvement was due mainly to a significant drop in interpretive expenses as described below. Without this extraordinary drop in expenses, our net income would have been down by approximately 4% when compared with 2023.

Our total income 2024 was basically flat when compared to 2023; it was up 0.8%. While our investement income was up 47%, this was almost completely offset by drops in our donations (3.6%), memberships (3.0%), and program income (3.5%). Visitor center sales were essentually flat with a decline of less than a percentage point. The greatest drop as measured in dollars, was program income due mainly due to reductions in Backcountry Weekend and Tarantula Fest, typically two of our highest revenue events. The drop in donations was not unexpected due to an extraordinary donation by a single individual in 2023.

Total expenses were down significantly (34.3%)

when compared with 2023. This reduction was mainly due to our interpretive expenses. In 2023 we funded the restoration of the cattle loading ramp and corral at Coe Ranch. While we had expected a similar expense in 2024 to fund interpretive panels around Coe Ranch, the design process has been taking longer than expected so these expenses will not be incurred until 2025. The remainder of our expenses are in line with the drop in our program income.

Our balance sheet remains strong with a 5.3% increase in our total assets. This was driven mainly by an increase in our bank acounts (8.1%) fueled by less than expected expenses.

Our financial performance in 2024 was respectable given the decline in income for our marquee events. Our focus for 2025 will be understanding the drop in attendance at our events and how to improve it as well as implementing strategies that allow our assets to return more and help further increase our ability fund interpretive projects.

PINE RIDGE ASSOCIATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Bobby Barnett PRESIDENT

Walter Dunckel VICE PRESIDENT

Albert Henning SECRETARY

Rick Casey TREASURER

Dan Benefiel

Steve McHenry

Jeff Zolotar

Stuart Organo SUPERVISING RANGER

THE PONDEROSA STAFF

Patrick Goodrich PUBLISHER

Teddy Goodrich

Margaret Mary McBride CO-EDITORS

CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE

Bobby Barnett

AUTHOR & PHOTOGRAPHER

Joseph Belli

AUTHOR & PHOTOGRAPHER

Barry Breckling

AUTHOR & PHOTOGRAPHER

Rick Casey

AUTHOR

Sue Dekalb

AUTHOR & PHOTOGRAPHER

Teddy Goodrich

AUTHOR & PHOTOGRAPHER

Margaret Mary McBride

AUTHOR

Michael Newburn

AUTHOR

Chris Weske

AUTHOR

Harishchandra Ramadas

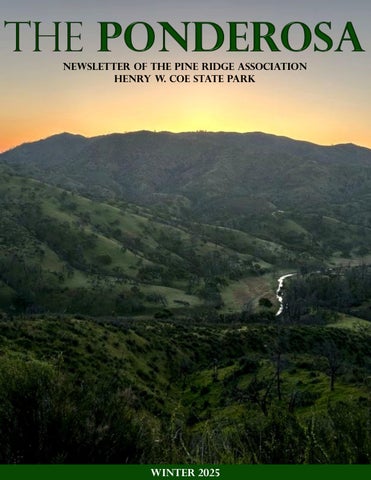

Eric Tuan

COVER PHOTO

C. Keller

Sheryl Nelson

Ron Wolf

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Pauline Wood

MEMBERSHIPS

We are pleased to announce the new members listed below. Thank you for your support!

Betsy Moore, Sunnyvale, CA

Albert Henning & Carol Muller, Palo Alto, CA

Eva Piontkowski, San Francisco, CA

Sean Rositano & Patricia Jonson, Gilroy, CA

We need your help to keep our membership list current and accurate. If you have any questions regarding your membership or to let us know of any change of address, please contact us via email at pra-membership@coepark.net or mail: Pine Ridge Association 9100 East Dunne Ave Morgan Hill, CA 95037

Membership supports the Pine Ridge Association’s mission to enhance and enrich the public’s experience at Henry W. Coe State Park through education and interpretation: https://coepark.net/pra

facebook.com/HenryWCoeSP instagram.com/HenryWCoeSP meetup.com/HenryWCoeSP

sfba.social/@HenryWCoeSP threads.net/@HenryWCoeSP

The Ponderosa is the quarterly publication of The Pine Ridge Association. Articles and artwork relating to the natural and cultural history of the park, park events, activities of the PRA Board, park management, and uniformed volunteer program are welcome! Please send submissions and ideas to ponderosa@coepark.net. Deadline for next issue is April 30, 2025.

© 2025 The Pine Ridge Association