WWW.JAMRIS.ORG pISSN 1897-8649 (PRINT)/eISSN 2080-2145 (ONLINE) VOLUME 19, N° 4, 2025

Indexed in SCOPUS

WWW.JAMRIS.ORG pISSN 1897-8649 (PRINT)/eISSN 2080-2145 (ONLINE) VOLUME 19, N° 4, 2025

Indexed in SCOPUS

A peer-reviewed quarterly focusing on new achievements in the following fields: • automation • systems and control • autonomous systems • multiagent systems • decision-making and decision support • • robotics • mechatronics • data sciences • new computing paradigms •

Editor-in-Chief

Janusz Kacprzyk (Polish Academy of Sciences, Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Advisory Board

Dimitar Filev (Research & Advenced Engineering, Ford Motor Company, USA)

Kaoru Hirota (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan)

Witold Pedrycz (ECERF, University of Alberta, Canada)

Co-Editors

Roman Szewczyk (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Oscar Castillo (Tijuana Institute of Technology, Mexico)

Marek Zaremba (University of Quebec, Canada)

Executive Editor

Katarzyna Rzeplinska-Rykała, e-mail: office@jamris.org (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Associate Editor

Piotr Skrzypczyński (Poznań University of Technology, Poland)

Statistical Editor

Małgorzata Kaliczyńska (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Editorial Board:

Chairman – Janusz Kacprzyk (Polish Academy of Sciences, Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Plamen Angelov (Lancaster University, UK)

Adam Borkowski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Wolfgang Borutzky (Fachhochschule Bonn-Rhein-Sieg, Germany)

Bice Cavallo (University of Naples Federico II, Italy)

Chin Chen Chang (Feng Chia University, Taiwan)

Jorge Manuel Miranda Dias (University of Coimbra, Portugal)

Andries Engelbrecht ( University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa)

Pablo Estévez (University of Chile)

Bogdan Gabrys (Bournemouth University, UK)

Fernando Gomide (University of Campinas, Brazil)

Aboul Ella Hassanien (Cairo University, Egypt)

Joachim Hertzberg (Osnabrück University, Germany)

Tadeusz Kaczorek (Białystok University of Technology, Poland)

Nikola Kasabov (Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand)

Marian P. Kaźmierkowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Laszlo T. Kóczy (Szechenyi Istvan University, Gyor and Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Hungary)

Józef Korbicz (University of Zielona Góra, Poland)

Eckart Kramer (Fachhochschule Eberswalde, Germany)

Rudolf Kruse (Otto-von-Guericke-Universität, Germany)

Ching-Teng Lin (National Chiao-Tung University, Taiwan)

Piotr Kulczycki (AGH University of Science and Technology, Poland)

Andrew Kusiak (University of Iowa, USA)

Mark Last (Ben-Gurion University, Israel)

Anthony Maciejewski (Colorado State University, USA)

Typesetting

SCIENDO, www.sciendo.com

Webmaster TOMP, www.tomp.pl

Editorial Office

ŁUKASIEWICZ Research Network

– Industrial Research Institute for Automation and Measurements PIAP

Al. Jerozolimskie 202, 02-486 Warsaw, Poland (www.jamris.org) tel. +48-22-8740109, e-mail: office@jamris.org

The reference version of the journal is e-version. Printed in 100 copies.

Articles are reviewed, excluding advertisements and descriptions of products.

Papers published currently are available for non-commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. Details are available at: https://www.jamris.org/index.php/JAMRIS/ LicenseToPublish

Open Access.

Krzysztof Malinowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Andrzej Masłowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Patricia Melin (Tijuana Institute of Technology, Mexico)

Fazel Naghdy (University of Wollongong, Australia)

Zbigniew Nahorski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Nadia Nedjah (State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

Dmitry A. Novikov (Institute of Control Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia)

Duc Truong Pham (Birmingham University, UK)

Lech Polkowski (University of Warmia and Mazury, Poland)

Alain Pruski (University of Metz, France)

Rita Ribeiro (UNINOVA, Instituto de Desenvolvimento de Novas Tecnologias, Portugal)

Imre Rudas (Óbuda University, Hungary)

Leszek Rutkowski (Czestochowa University of Technology, Poland)

Alessandro Saffiotti (Örebro University, Sweden)

Klaus Schilling (Julius-Maximilians-University Wuerzburg, Germany)

Vassil Sgurev (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Intelligent Systems, Bulgaria)

Helena Szczerbicka (Leibniz Universität, Germany)

Ryszard Tadeusiewicz (AGH University of Science and Technology, Poland)

Stanisław Tarasiewicz (University of Laval, Canada)

Piotr Tatjewski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Rene Wamkeue (University of Quebec, Canada)

Sławomir Wierzchon (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Janusz Zalewski (Florida Gulf Coast University, USA)

Teresa Zielińska (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Publisher:

Copyright © by Łukasiewicz

VOLUME 19, N˚4, 2025

1

Positivity and Stability of Descriptor DiscreteTime Linear Systems with Interval State Matrices

Tadeusz Kaczorek

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐030

7

Innovation Capacities and Business Models in Colombian Farming Organizations

Daniela Niño‐Amezquita, Jhancarlos Gutiérrez‐Ayala, Diana María Dueñas Quintero, Fabio Blanco‐Mesa, Eduardo Covarrubias‐Audelo

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐031

18

A 2-tuple Linguistic Dynamic Owawa Aggregation Operator and its Application to Multi-Attribute Decision-Making

Yeleny Zulueta‐Véliz, Carlos Rafael Rodríguez Rodríguez, Aylin Estrada Velazco

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐032

26

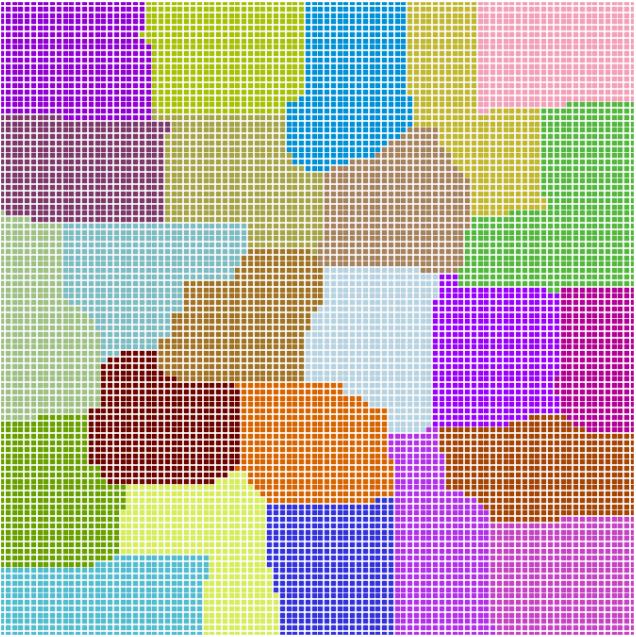

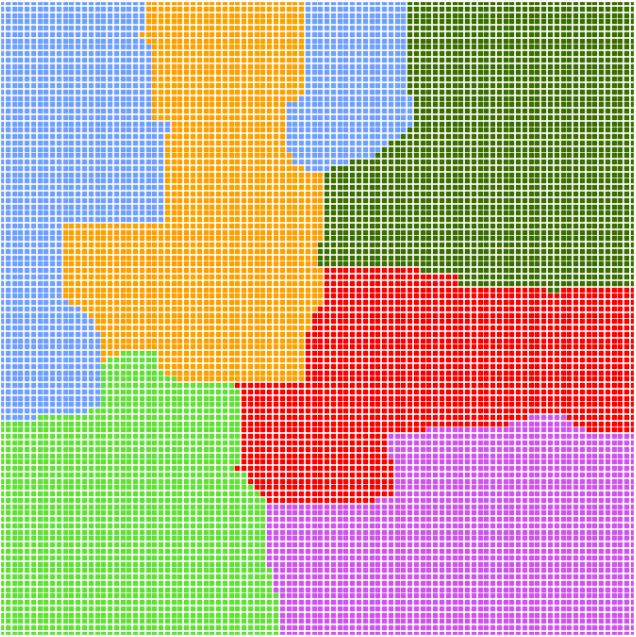

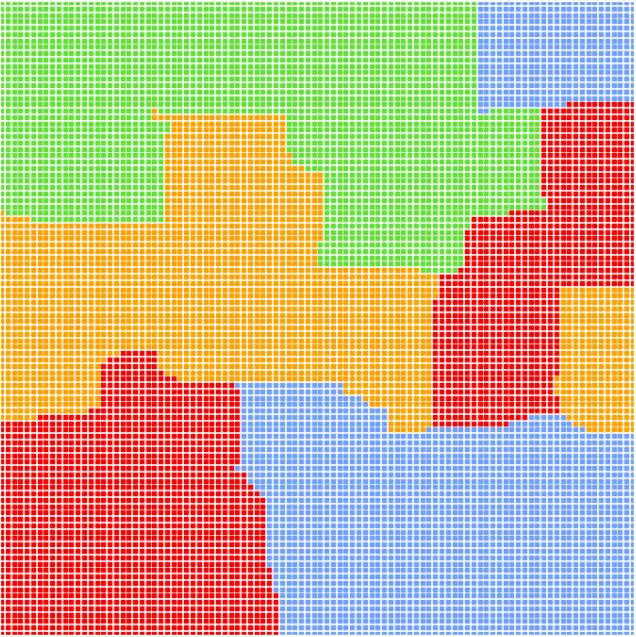

Partitioning of Complex Discrete Models for Highly Scalable Simulations

Jakub Ziarko, Mateusz Najdek, Wojciech Turek

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐033

35

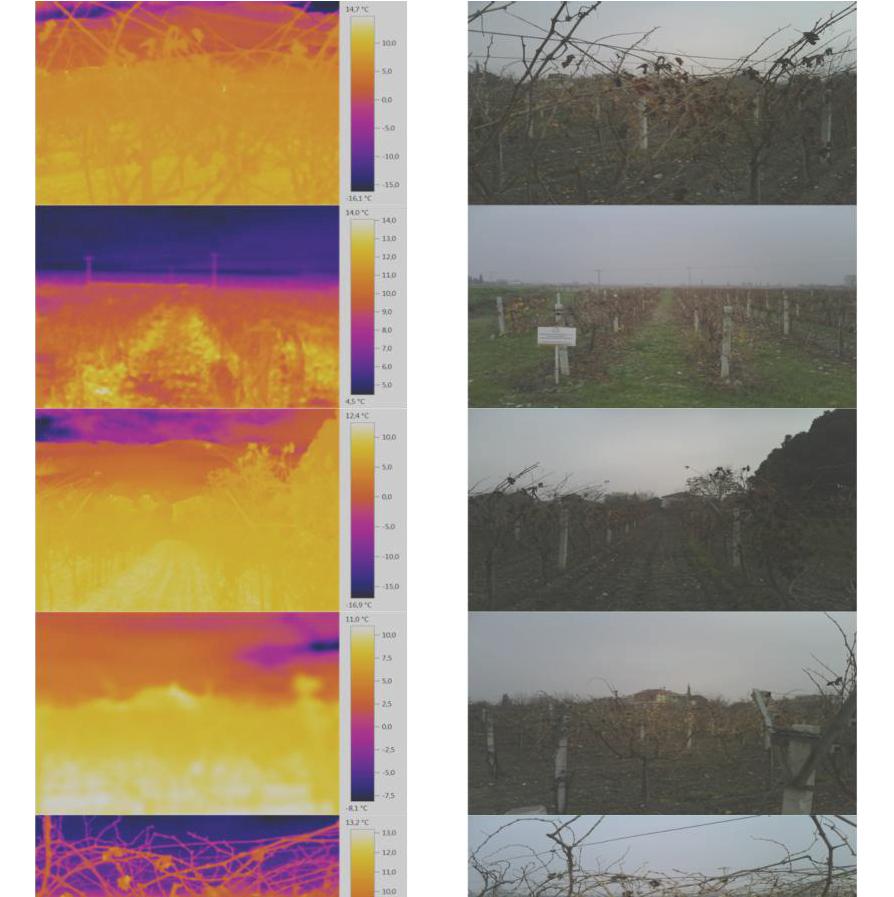

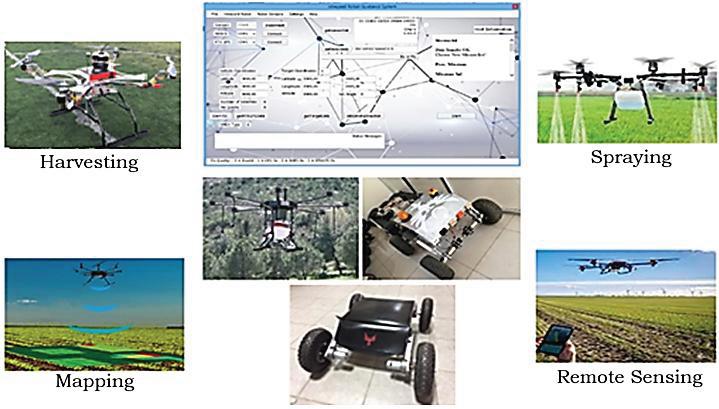

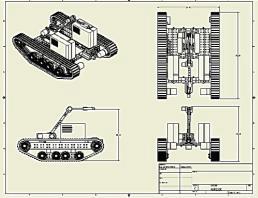

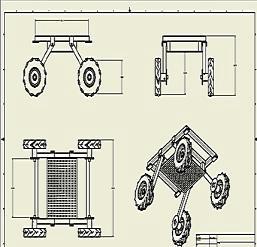

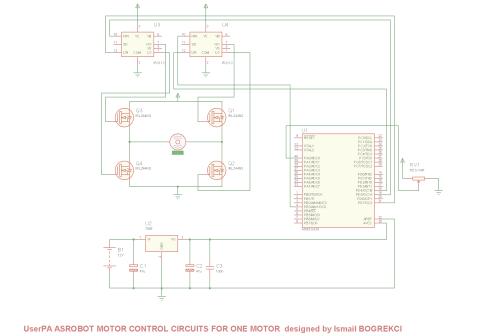

Advancements in Industry-Agriculture 5.0: Utilizing Unmanned Ground and Aerial Vehicles for Sustainable Precision Agriculture

Ismail Bogrekci, Pinar Demircioglu

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐034

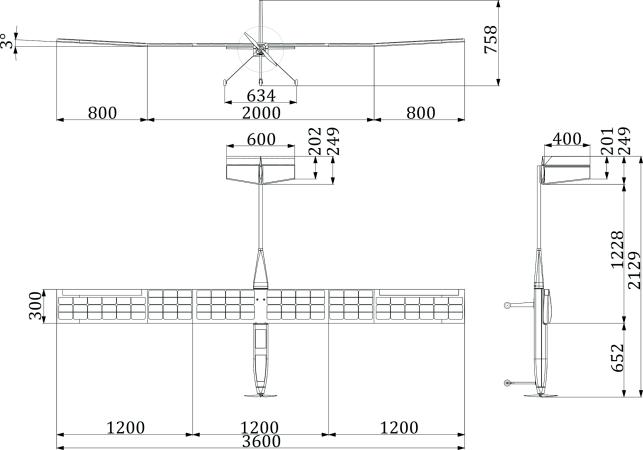

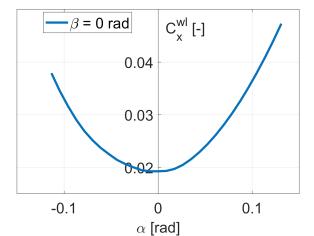

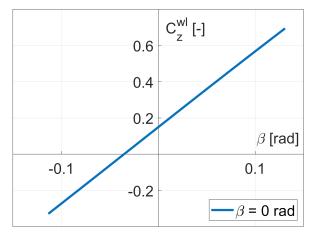

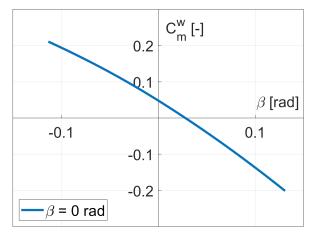

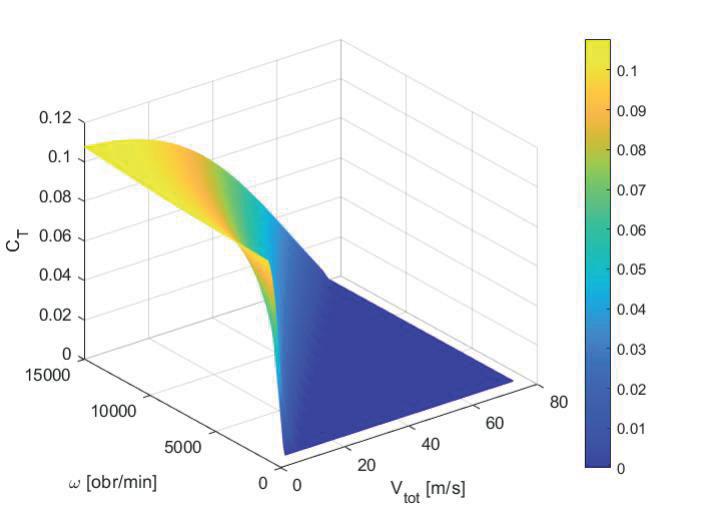

In-Flight Solar Radiation Intensity Measurement Using a Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

Rafał Oz̀óg, Mariusz Jacewicz, Robert Głębocki, Juliusz

Hanke

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐035

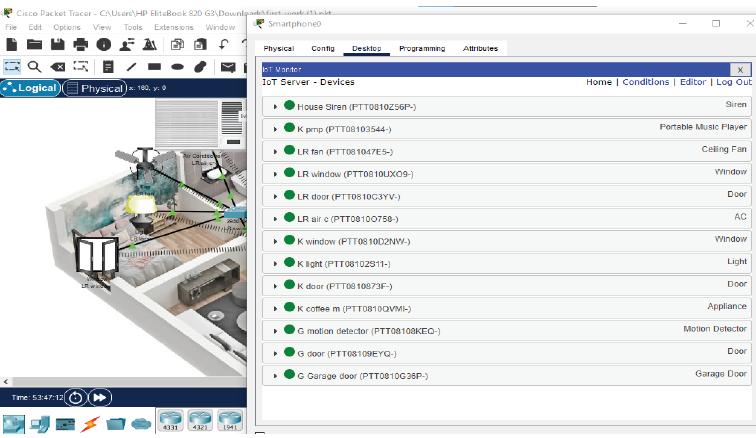

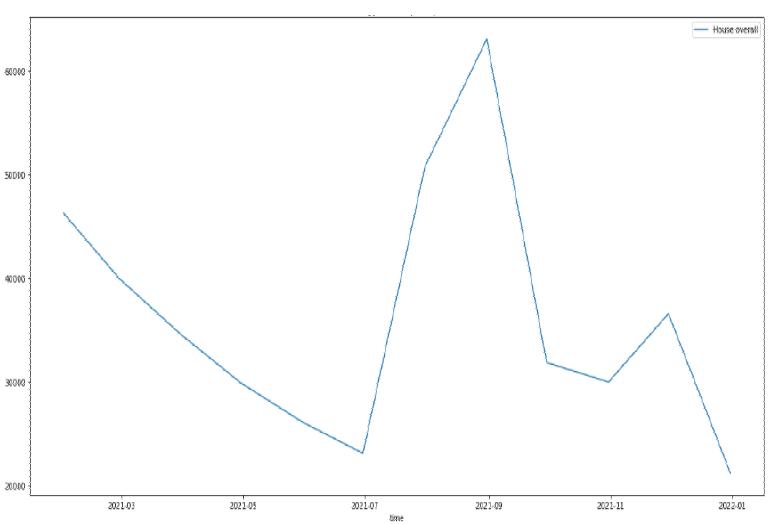

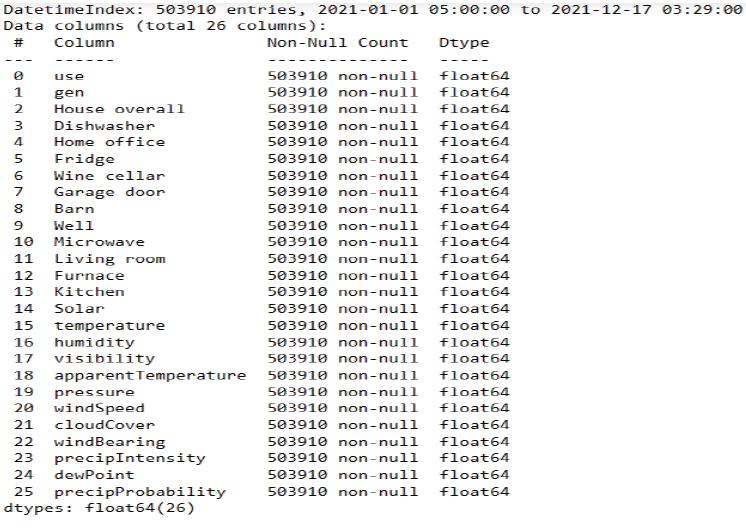

Challenges in Predicting Smart Grid Stability Linked with Renewable Energy Resources through Spark MLlib Learning

Amal Zouhri, Ismail Boumhidi, Ismail Boumhidi, Abderahamane Ez‑Zahout, Said Chakouk, Mostafa El Mallahi

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐036

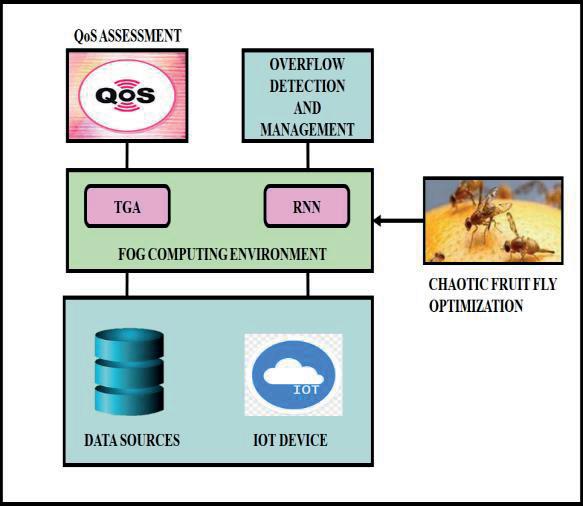

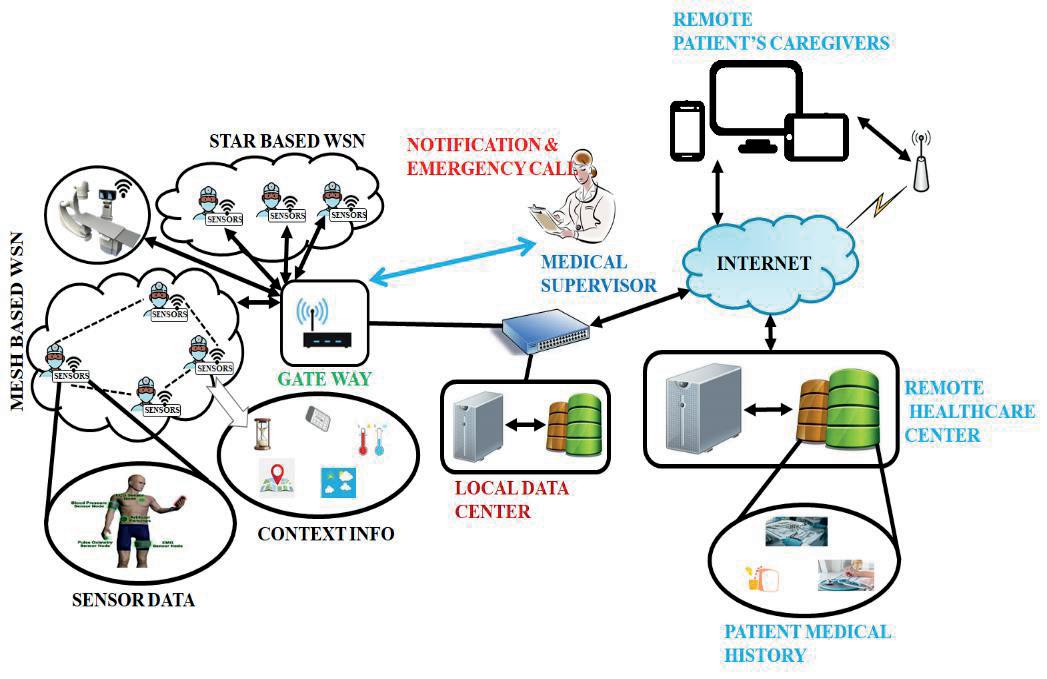

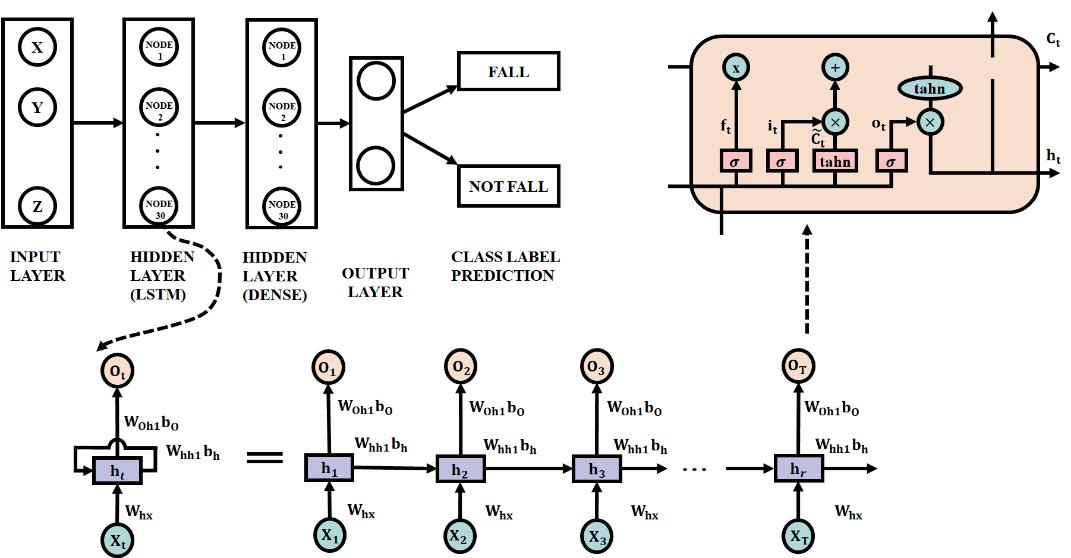

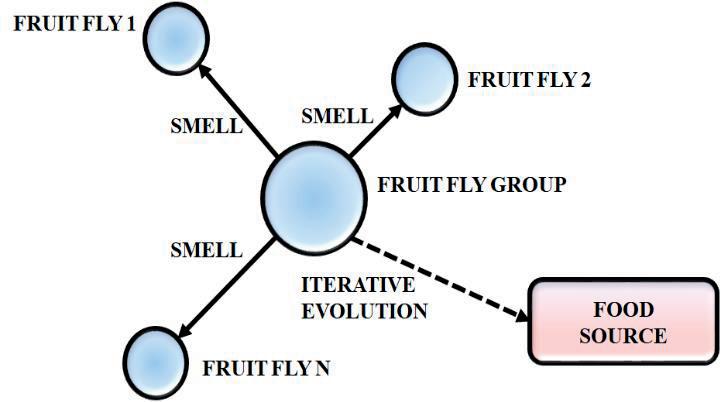

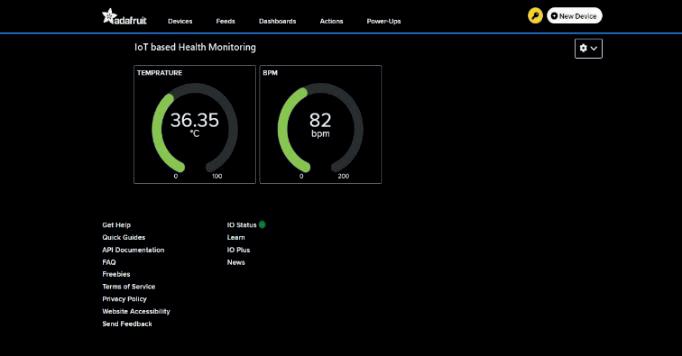

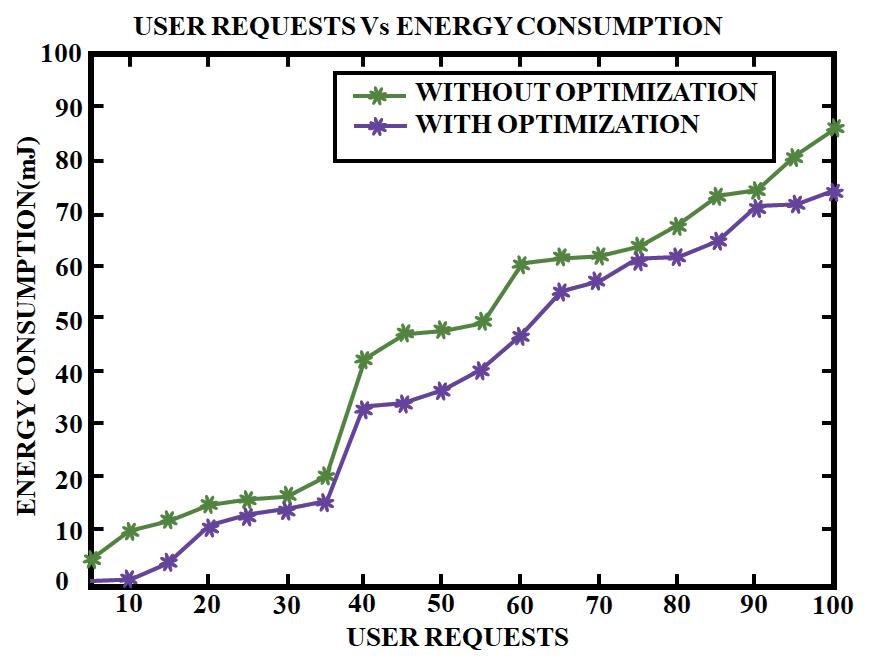

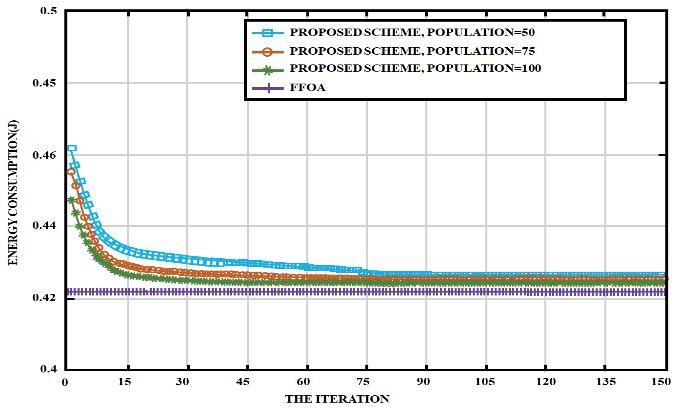

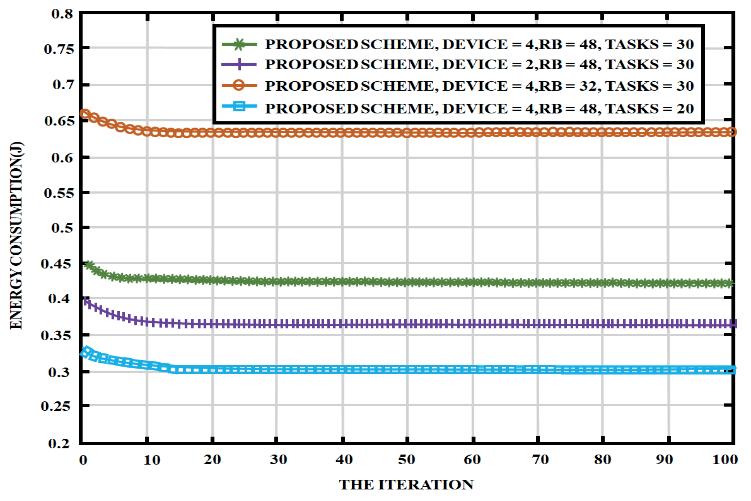

Enhancing Efficiency And Security In Healthcare IoT: A Novel Approach for Fog Computing Resource Optimization Using TGA-RNN

Rahul Jaywantrao Shimpi, Vibha Tiwari

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐037

94

Finding the Sweet Spot: A Study of Data Augmentation Intensity for Small-Scale Image Classification

Windra Swastika

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐038

102

Design of a Fuzzy PID Controller to Improve Electric Vehicles Performance Based on Regenerative Braking System

Hayder Abdulabbas Abdulameer, M A Khamis, Mo‐hammed Joudah Zaiter, Karin Ennser

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐039

109

RETRACTION NOTE

DOI: 10.14313/jamris‐2025‐040

DOI:10.14313/jamris‐2025‐030

Abstract:

Submitted:8th July2024;accepted:20th May2025

TadeuszKaczorek

Thepositivityandstabilityofdescriptordiscrete‐time linearsystemswithintervalstatematricesareaddressed. Necessaryandsufficientconditionsforthepositivityof descriptordiscrete‐timelinearsystemsareestablished. Thestabilityofdescriptorlinearsystemswithinterval statematricesisinvestigated.

Keywords: Descriptor,Linear,Discrete‐time,Intervalsys‐tem,Positivity,stability

1.Introduction

Adynamicalsystemiscalledpositiveifitsstate variablestakenonnegativevaluesforallnonnegative inputsandnonnegativeinitialconditions.Positivelin‐earsystemshavebeeninvestigatedin[1,5,10,11], whilepositivenonlinearsystemshavebeenstudied in[6,7,9,17,19].

Examplesofpositivesystemsincludeindustrial processesinvolvingchemicalreactors,heatexchang‐ers,anddistillationcolumns,aswellasstoragesys‐tems,compartmentalsystems,andmodelsforwater andatmosphericpollution.Avarietyofmodelshaving positivelinearbehaviorcanbefoundinengineering, managementscience,economics,socialsciences,biol‐ogy,andmedicine.

Positivelinearsystemswithdifferentfractional ordershavebeenaddressedin[3,12,14,23].Descrip‐tor(singular)linearsystemshavebeenanalyzedin [9, 15, 16],andthestabilityofaclassofnonlinear fractional‐ordersystemsin[6, 13, 19, 26].Applica‐tionofDrazininversetotheanalysisofdescriptor fractionaldiscrete‐timelinearsystemshasbeenpre‐sentedin[8],andstabilityofdiscrete‐timeswitched systemswithunstablesubsystemsin[24].Therobust stabilizationofdiscrete‐timepositiveswitchedsys‐temswithuncertaintieshasbeenaddressedin[25]. Comparisonofthreemethodsofanalysisofthe descriptorfractionalsystemshasbeenpresentedin [22].Stabilityoflinearfractionalordersystemswith delayshasbeenanalyzedin[2],andsimpleconditions forpracticalstabilityofpositivefractionalsystems havebeenproposedin[4].Theasymptoticstabilityof intervalpositivediscrete‐timelinearsystemshasbeen investigatedin[18].

Inthispaper,thepositivityandstabilityofdescrip‐tordiscrete‐timelinearsystemswithintervalstate matriceswillbeaddressed.

Thepaperisorganizedasfollows.InSection 2,somebasicde initionsandtheoremsrelatedto descriptordiscrete‐timelinearsystemsarereviewed. InSection3,thepositivityofdescriptordiscrete‐time linearsystemsisinvestigated.Thestabilityofpositive descriptorlineardiscrete‐timesystemsisanalyzedin Section4,andthestabilityofpositivedescriptorlinear systemswithintervalstatematricesisanalyzedin Section5.Concludingremarksaregiveninsection6. Thefollowingnotationswillbeused:R‐theset ofrealnumbers,R������ ‐thesetofnxmrealmatrices, R������ + ‐thesetof nxm realmatriceswithnonnegative entriesandR�� + =R����1 + ,Z+ ‐thesetofnonnegative integers,I��− ‐the nxn identitymatrix,forA=[a����]∈ R������ andB=[b����]∈R������ andinequalityA=Bmeans a���� =b���� fori,j=1.2,…n.

2.Preliminaries

Considertheautonomousdescriptordiscrete‐time linearsystem ������+1 =������,��∈��+ ={0,1,...}, (1)

where���� ∈ℜ�� isthestatevectorand��,��∈ℜ��×�� .

Itisassumedthat det[����−��]≠0forsome��∈ C (the ieldofcomplexnumbers) (2)

Inthiscase,thesystem(1)hasauniquesolution foradmissibleinitialconditions��0 ∈ℜ�� +.

Itiswell‐known[20]thatif(2)holds,thenthere existsapairofnonsingularmatrices��,��∈ℜ��×�� such that ��[����−��]��= ����1 ��−��1 0 0����−����2 , ��1 ∈ℜ��1×��1,��∈ℜ��2×��2 , (3)

where��1 = deg{det[����−��]}and N isthenilpotent matrix,i.e. ���� =0, ����−1 ≠0 (�� isthenilpotency index).

Tosimplifytheconsiderations,itisassumedthat thematrix N hasonlyoneblock.

Thenonsingularmatrices P and Q canbefound, forexample,bytheuseofelementaryrowandcolumn operations[20]: 1) Multiplicationofany i‐throw(column)bythe number��≠0.Thisoperationwillbedenotedby ��[��×��](��[��×��]).

2) Additiontoany i‐throw(column)ofthe j‐throw (column)multipliedbyanynumber ��≠0.This operationwillbedenotedby��[��+��×��](��[��+��×��]).

3) Interchangeofanytworows(columns).Thisoper‐ationwillbedenotedby��[��,��](��[��,��]).

De inition2.1. [5,11]Theautonomousdiscrete‐time linearsystem ����+1 =������,��∈ℜ��×�� (4)

iscalled(internally)positiveif���� ∈ℜ�� +,��∈��+ forall ��0 ∈ℜ�� +

Theorem2.1. [5,11]Thesystem(4)ispositiveifand onlyif ��∈ℜ��×�� + . (5)

De inition2.2. [5,11]Thepositivesystem(4)iscalled asymptoticallystable(Schur)if lim ��→∞ ���� =0forall��0 ∈ℜ��1 + (6)

Theorem2.2. [18]Thepositivesystem(4)isasymp‐toticallystableifandonlyifoneoftheequivalent conditionsissatis ied:

1) Allcoef icientsofthecharacteristicpolynomial det[����(��+1)−��]=����+����−1����−1+...+��1��+��0 (7) arepositive,i.e.���� >0for��=0,1,...,��−1

2) Thereexistsastrictlypositivevector ��= [��1 ⋯����]�� ,���� >0,��=1,…,��suchthat ����<��. (8)

3.PositiveDescriptorLinearSystems

Inthissection,thenecessaryandsuf icientcon‐ditionsforthepositivityofthedescriptorlinear discrete‐timesystemswillbeestablished.

De inition3.1. Thedescriptorsystem(1)iscalled (internally)positiveif���� ∈ℜ�� +,��∈��+ foralladmissi‐blenonnegativeinitialconditions��0 ∈ℜ�� +

Theorem3.1. Thedescriptorsystem(1)ispositiveif andonlyifthematrix E hasonlylinearlyindependent columns,andthematrix��1 ∈ℜ��1×��1 + .

Proof. Usingthecolumnpermutation(thematrix Q) wechoose ��1 linearlyindependentcolumnsofthe matrix E asits irstcolumns.Next,usingelemen‐taryrowoperations(thematrixP),wetransformthe matrix E totheform ����1 0 0�� andthematrix A tothe form ��1 0 0����2 .From(2),itfollowsthatthesystem(1) hasbeendecomposedintothefollowingtwoindepen‐dentsubsystems

where

and

+ (11)

and Q and��−1 arepermutationmatrices. Notethatthesolution ��1,�� =���� 1��10, ��∈��+ of (9)isnonnegativeifandonlyif��1 ∈ℜ��1×��1 + andthe solution��2,�� of(10)iszerofor��=1,2,...

Example3.1. Considerthedescriptorsystem(1)with thematrices ��= ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ 0002 010−2 1−200 000−2 ⎤ ⎥ ⎥ ⎦ ,��= ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ 0101 1−2 3 0−1 0 2 3 10 1−10−1

Thecondition(2)issatis iedsince det[����−��]= 0−102��−1 −1��+ 2 3 0−2��+1 ��−2��− 2 3 −10

=−2��2 + 5 3 ��− 1 3 (13) and��1 =2.Inthiscase����������=3and��=����������− ��1 +1=2.Performingonthematrix

⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ 0−102��−1 −1��+ 2 3 0−2��+1 ��−2��− 2 3 −10 −110−2��+1

(14)

thefollowingcolumnshowselementaryoperations ��[4×1 2],��[4,1]andtherowoperations��[2+4×(−1)], ��[4+1×1],��[3+2×2]weobtain ��1 = 1 2 1 0 1 3 ,��= 01 00 . (15)

Inthiscase,thematrices Q and P havetheforms

⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢

(16)

ByTheorem3.1,thedescriptorsystem(1)with(12) ispositivesince��1 ∈ℜ2×2 + andthematrix Q ismono‐mial.

4.StabilityofPositiveDescriptorLinearSys‐tems

Considerthedescriptorsystem(1)satisfyingthe condition(2).

Lemma4.1. Thecharacteristicpolynomialsofthesys‐tem(1)andofthematrix��1 ∈ℜ��1×��1 arerelatedby det[����1 ��−��1]=��det[����−��], (17) where��=(−1)��2 det��det��.

Proof. From(2)wehave ������[����1 ��−��1]=(−1)��2 det ����1 ��−��1 0 0����−����2 =(−1)��2 det��det[����−��]det�� =��det[����−��]. (18)

Theorem4.1. Thepositivedescriptorsystem(1)is asymptoticallystableifandonlyifoneofthefollowing equivalentconditionsissatis ied:

1) Allcoef icientsofthecharacteristicpolynomial det[����1(��+1)−��1]=����1+����1−1����1−1+...+��1��+��0 (19) arepositive,i.e.���� >0for��=0,1,...,��1 −1

2) Allcoef icientsofthecharacteristicequationofthe matrix����−�� det[��(��+1)−��]=̄����1 ����1 +̄����1−1����1−1 +...+̄��1��+̄��0 =0 (20) arepositive.

3) Thereexistsastrictlypositivevector ��= [��1 ⋯����1]�� ,���� >0,��=1,...,��1 suchthat ��1��<��. (21)

4) Thereexistsastrictlypositivevector ��= [��1 ����1]�� ,���� >0,��=1,...,��1 suchthat ������<��, (22a) where ��=����1 ����1, (22b)

����1

∈ℜ��1×��1 + consistsof ��1 nonzerorowsof ����1 ∈ℜ��×��1 + whichisbuiltof irst��1 columnsof thematrix Q de inedby(2), ����1 ∈ℜ��1×�� consistsof��1 rowsofthematrix P de inedby(2),

��∈ℜ��×��1 consistsof��1 columnsof��∈ℜ��×�� correspondingtothenonzerorowsof����1 Proof. Proofofcondition1)followsimmediatelyfrom condition1)ofTheorem2.2.ByLemma4.1det[����1(��+ 1)−��1]=0ifandonlyifdet[��(��+1)−��]=0.There‐fore,thepositivedescriptorsystem(1)isasymptot‐icallystableifandonlyifallcoef icientsof(20)are positive.

From(2),wehave ��1 =����1������1 (23) andusing(8),weobtain ��1��=����

��1 ��<�� (24) forsomestrictlypositivevector��∈ℜ��1 + .Premultiply‐ing(24)by����1 andtakingintoaccount����1 ��= ��and eliminatingfrom A allcolumnscorrespondingtozero rowsof����1 weobtain(22).

Example4.1. (ContinuationofExample3.1)Using Theorem4.1,checktheasymptoticstabilityofthe positivedescriptorsystem(1)withthematrices(12). Thematrix��1 ofthesystemisgivenby(15)andits characteristicpolynomial

det[��2(��+1)−��1]= ��+ 1 2 −1 0��+ 1 3

��+ 1 3 (25) haspositivecoef icients.Therefore,bycondition1)of Theorem4.1,thematrix��1 isasymptoticallystable. Thecharacteristicequation(20)ofthematrices (12)

det[��(��+1)−��] = 0 −102��+1 −1��+ 5 3 0−2��−1 ��+1−2��− 8 3 −10 −1 10−2��−1

=2��2 + 7 3 ��+ 2

(26) haspositivecoef icientsandbycondition2)ofTheo‐rem4.1,thepositivesystemisasymptoticallystable. Inthiscasewehave

(27) and

Therefore,using(22a),(27),and(28),weobtain

(29) andbycondition(22),thepositivesystemisasymp‐toticallystable.

5.StabilityofPositiveDescriptorLinearSys‐temsWithIntervalStateMatrices

Considertheautonomousdescriptorpositivelin‐earsystem ������+1 =������,��∈��+ (30) where���� ∈ℜ�� isthestatevector,��∈ℜ��×�� isconstant (exactlyknown)and ��∈ℜ��×�� isanintervalmatrix de inedby ��≤��≤��orequivalently��∈[��,��]. (31)

Itisassumedthat

det[����−��]≠0anddet[����−��]≠0 (32)

andthematrix E hasonlylinearlyindependent columns.

Iftheseassumptionsaresatis ied,thenthereexist twopairsofnonsingularmatrices (��1,��1), (��2,��2) suchthat

columnsandintervalmatrix A isasymptoticallystable ifandonlyifthereexistsastrictlypositivevector��∈ ℜ�� + suchthat ������<��and������<��, (38) where��isde inedby(22b).

Proof. Byassumption,thematrix E hasonlylinearly independentcolumnsand ��=������ ∈ℜ�� + isstrictly positiveforany���� ∈ℜ�� + withallpositivecomponents. Bycondition2)ofTheorem2.2andTheorem5.2, thepositivedescriptorsystemwithinterval(31)is asymptoticallystableifandonlyiftheconditions(38) aresatis ied.

Example5.1. (ContinuationofExample4.1)Consider thepositivedescriptorsystem(30)with E givenby (12)andtheintervalmatrix A with

= ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ 0100.4 0−0.70−0.4 1−0.610 0−10−0.4

Theorem5.1. Iftheassumptionsaresatis ied,then theintervaldescriptorsystem(30)with(31)ispos‐itiveifandonlyif

and��1 ∈ℜ��1×��1 + (34)

Proof. TheproofissimilartotheproofofTheorem3.1.

De inition5.1. Thepositivedescriptorintervalsys‐tem(30)iscalledasymptoticallystable(Schur)ifthe systemisasymptoticallystableforallmatrices E,��∈ [��,��].

Theorem5.2. Ifthematrices��and��ofthepositive system(30)isasymptoticallystable,thenitsconvex linearcombination

��=(1−��)��+����for0≤��≤1 (35) isalsoasymptoticallystable.

Proof. Bycondition2)ofTheorem2.2,ifthepositive systemsareasymptoticallystable,thenthereexistsa strictlypositivevector��∈ℜ�� + suchthat ����<��and����<��. (36)

Using(35)and(36),weobtain ����=[(1−��)��+����]�� =(1−��)����+������<(1−��)��+���� =��for0≤��≤1. (37)

Therefore,ifthematrices��and��(36)hold,then theconvexlinearcombinationisalsoasymptotically stable.

Theorem5.3. Thepositivedescriptorsystem(30) withthematrix E withonlylinearlyindependent

⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ 0100.8 0−0.40−0.8 1−1.210 0−10−0.8

(39)

WeshallcheckthestabilityofthesystemusingTheo‐rem5.3.Thematrices Q and P havethesameform(16) asinExamples3.1and4.1.Therefore,thematrix��in (38)isthesameasinExample4.1,anditisgivenby (27).Takingintoaccountthatinthiscase

⎥ ⎥ ⎦ (40) andusing(38),weobtain

Therefore,byTheorem5.3,thepositivedescriptor systemisasymptoticallystable.

Thepositivityandasymptoticstabilityofdescrip‐torlineardiscrete‐timesystemshavebeenaddressed. Necessaryandsuf icientconditionsforthepositiv‐ity(Theorem3.1)ofthedescriptorlineardiscrete‐timesystemsandfortheasymptoticstability(The‐orem4.1)ofpositivedescriptorsystemshavebeen established.Ithasbeenshownthatthedescriptor linearsystemsarepositiveifandonlyiftheconditions (34)aresatis ied(Theorem5.1).Necessaryandsuf i‐cientconditionsfortheasymptoticstabilityofaposi‐tivedescriptorlinearsystem(30)withintervalstate matriceshavealsobeenestablished(Theorem5.3). Numericalexamplesofdescriptorpositivediscrete‐timelinearsystemshaveillustratedtheconsidera‐tions.

Theconsiderationscanbeextendedtocontinuous‐timeanddiscrete‐timepositivefractionallinearsys‐tems.

AUTHOR

TadeuszKaczorek∗–BialystokUniversityofTechnol‐ogy,Poland,e‐mail:kaczorek@ee.pw.edu.pl.

∗Correspondingauthor

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ThisworkwassupportedbytheNationalScience Centreincountry‐regionplacePolandunderwork No.2014/13/B/ST7/03467.

References

[1] A.BermanandR.J.Plemmons,“Nonnegative matricesinthemathematicalsciences”,SIAM, 1994.

[2] M.Busłowicz,“Stabilityoflinearcontinuous‐timefractionalordersystemswithdelaysofthe retardedtype”, BulletinofthePolishAcademyof SciencesTechnicalSciences,vol.56,no.4,2008, 319–324.

[3] M.Busłowicz,“Stabilityanalysisofcontinuous‐timelinearsystemsconsistingofnsubsystems withdifferentfractionalorders”, Bulletinofthe PolishAcademyofSciencesTechnicalSciences,vol. 60,no.2,2012,279–284.

[4] M.BusłowiczandT.Kaczorek,“Simplecondi‐tionsforpracticalstabilityofpositivefractional discrete‐timelinearsystems”, InternationalJournalofAppliedMathematicsandComputerScience,vol.19,no.2,2009,263–269.

[5] L.FarinaandS.Rinaldi,“Positivelinearsystems: theoryandapplications”,J.Wiley,NewYork, 2000.

[6] T.Kaczorek,“Analysisofpositivityandstability offractionaldiscrete‐timenonlinearsystems”, BulletinofthePolishAcademyofSciencesTechnicalSciences,vol.64,no.3,2016,491–494.

[7] T.Kaczorek,“Analysisofpositivityandstability ofdiscrete‐timeandcontinuous‐timenonlinear systems”, ComputationalProblemsofElectrical Engineering,vol.5,no.1,2015.

[8] T.Kaczorek,“ApplicationofDrazininverseto analysisofdescriptorfractionaldiscrete‐time linearsystemswithregularpencils”, InternationalJournalofAppliedMathematicsandComputerScience,vol.23,no.1,2013,29–34.

[9] T.Kaczorek,“Descriptorpositivediscrete‐time andcontinuous‐timenonlinearsystems”, ProceedingsofSPIE,vol.9290,2014. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2074558.

[10] T.Kaczorek,“Fractionalpositivecontinuous‐timelinearsystemsandtheirreachability”, InternationalJournalofAppliedMathematicsand ComputerScience,vol.18,no.2,2008,223–228.

[11] T.Kaczorek,“Positive1Dand2Dsystems”, Springer‐Verlag,London,2002.

[12] T.Kaczorek,“Positivelinearsystemswithdif‐ferentfractionalorders”, BulletinofthePolish AcademyofSciencesTechnicalSciences,vol.58, no.3,2010,453–458.

[13] T.Kaczorek,“Positivityandstabilityofstandard andfractionaldescriptorcontinuous‐timelin‐earandnonlinearsystems”, InternationalJournal ofNonlinearSciencesandNumericalSimulation, 2017(inpress).

[14] T.Kaczorek,“Positivelinearsystemsconsisting ofnsubsystemswithdifferentfractionalorders”, IEEETransactionsonCircuitsandSystems,vol. 58,no.7,2011,1203–1210.

[15] T.Kaczorek,“Positivefractionalcontinuous‐time linearsystemswithsingularpencils”, Bulletinof thePolishAcademyofSciencesTechnicalSciences, vol.60,no.1,2012,9–12.

[16] T.Kaczorek,“Positivesingulardiscrete‐timelin‐earsystems”, BulletinofthePolishAcademyof SciencesTechnicalSciences,vol.45,no.4,1997, 619–631.

[17] T.Kaczorek,“Positivityandstabilityofdiscrete‐timenonlinearsystems”, IEEE2ndInternational ConferenceonCybernetics,2015,156–159.

[18] T.Kaczorek,“Stabilityofintervalpositive discrete‐timelinearsystems”,submittedto BulletinofthePolishAcademyofSciences TechnicalSciences,2017.

[19] T.Kaczorek,“Stabilityoffractionalpositivenon‐linearsystems”, ArchivesofControlSciences,vol. 25,no.4,2015,491–496.https://doi.org/10.1 515/acsc‐2015‐0031.

[20] T.Kaczorek,“Theoryofcontrolandsystems”, PWN,Warszawa,1993(inPolish).

[21] V.L.Kharitonov,“Asymptoticstabilityofanequi‐libriumpositionofafamilyofsystemsofdif‐ferentialequations”, DifferentsialnyeUravneniya, vol.14,1978,2086–2088.

[22] Ł.Sajewski,“Descriptorfractionaldiscrete‐time linearsystemanditssolution–comparison ofthreedifferentmethods”, Challengesin Automation,RoboticsandMeasurement Techniques,AdvancesinIntelligentSystems andComputing,vol.440,2016,37–50.

[23] Ł.Sajewski,“Descriptorfractionaldiscrete‐time linearsystemwithtwodifferentfractional ordersanditssolution”, BulletinofthePolish AcademyofSciencesTechnicalSciences,vol.64, no.1,2016,15–20.

[24] H.Zhang,D.Xie,H.Zhang,andG.Wang,“Stability analysisfordiscrete‐timeswitchedsystemswith unstablesubsystemsbyamode‐dependentaver‐agedwelltimeapproach”, ISATransactions,vol. 53,2014,1081–1086.

[25] J.Zhang,Z.Han,H.WuandJ.Hung,“Robust stabilizationofdiscrete‐timepositiveswitched systemswithuncertaintiesandaveragedwell timeswitching”, Circuits,SystemsandSignalProcessing,vol.33,2014,71–95.

[26] W.Xiang‐Jun,W.Zheng‐Mao,andL.Jun‐Guo, “Stabilityanalysisofaclassofnonlinear fractional‐ordersystems”, IEEETransactionson CircuitsandSystemsII:ExpressBriefs,vol.55,no. 11,2008,1178–1182.

Submitted:20th February2025;accepted:17th September2025

DanielaNiño‑Amezquita,JhancarlosGutiérrez‑Ayala,DianaMaríaDueñasQuintero,FabioBlanco‑Mesa, EduardoCovarrubias‑Audelo

DOI:10.14313/jamris‐2025‐031

Abstract:

Themainobjectiveofthispaperistoanalyzetheinter‐actionbetweeninnovationcapabilitiesandelementsof thebusinessmodeloffarmingorganizationsinBoyacá, Colombia.Thisstudyusedaquantitativemethodology, employingthePartialLeastSquaresPathModeling(PLS‐PM)technique.Thetheoreticalmodelincludesseven hypothesesthatoutlinetherelationshipsbetweeninno‐vationcapabilities(sensing,seizing,andtransformation) andabusinessmodel(creation,delivery,andcapture). Thestudyrevealedasignificantcorrelationbetweenthe abilitytodetectandretaininnovationandthedevel‐opmentandimplementationofbusinessmodels.This underscoresthesignificanceofcontinuouslearningand efficientalliancemanagementinacquiringandutilizing environmentalknowledge.Theimplicationsofthisstudy aredirectedtowardsdecision‐makers,stakeholders,and policymakerswithinColombia’sNationalAgricultural InnovationSystem(NAIS).Thestudyemphasizesthecru‐cialroleofawell‐integratedsystemamongitsvarious actorsininfluencingthesuccessofbusinessmodels. Itexaminesinnovationasadynamiccapabilityandits interplaywithvitalcomponentsofthebusinessmodel, therebyenhancingcomprehensionofbusinessdynamics withinthissector.

Keywords: InnovationCapabilities,BusinessModelInno‐vation,FarmingOrganizations.

TheResource‐basedview(RBV)providesaframe‐workforexaminingthedevelopmentofsustainable competitiveadvantagesovertime[1],whichmain‐tainsthatstrategicresourcescouldleadtosustained competitiveadvantage[2].Thisapproachsuggests thatorganizationaldiversityandheterogeneitycreate resourcesandcapabilitiesthatestablishacompetitive position.Fromthistheory,dynamiccapabilitiesview emerges,whereitassumesthatthevalueofstrate‐gicresourceswillerodeovertimeastrendsevolve [3].Hence,morethanjusthard‐to‐replicateassetsare needed;itisessentialtoequiponeselfwithcapabili‐tiestocreate,expand,andupdatetheorganization’s assetbase.Buildingontheoutlinedtheoreticalfoun‐dations,theroleofinnovationasacapabilityisestab‐lishedascrucialinvaluecreation.

Innovationcapabilityrepresentstheexploitative potentialofknowledge,fromitsexplorationandseiz‐ingwithinandoutsidethecompany[4].Innova‐tioninvolvesacomprehensiveprocessofknowledge exchangewiththeimplementationofnewideas,prod‐ucts,processes,orservices[5].Therefore,innovation canoccurwithinthebusinessmodel,embodyingthe deliveryofvalueandenablingorganizationstoadapt andpositionthemselvesinthevaluechain[6].

Innovationisin luencedbyenablingconditions andislinkedtohuman,organizational,orenviron‐mentalknowledgeandcapabilities[7].Intheagricul‐turalcontext,thesefactorsfacilitatetheemergence ofnewideasthatuseexistingresourcesandcapa‐bilitiestoidentifyopportunitiesandinnovativesolu‐tions[8,9],butitlacksinfrastructureandtechnology neededtodevelopcapabilitiestostimulateinnovation [10].Tosolvethat,farmersareconformedassociative unitsthathelpproducerstogainbargainingpower, reduceproductioncosts,improveproductivityand marketing,andmanagepriceuncertainty[11],where cohesionderivesfromthelinksoftrustandcoopera‐tionthatpromoteparticipatoryworkschemesamong itsmembers[12].Likewise,abusinessmodelmay involveacollaborativeprocessthatincludespartner‐shipstoaddresscommonissuesandachievesocial and inancialgoals,i.e.,associatingwithothersallows organizationstomarketwithlowerinvestmentsatan individuallevel[13].Therefore,analyzingtheinnova‐tioncapabilitiesandbusinessmodelsoftheseorga‐nizationscanprovideinsightintotheirsuccessfac‐torsandhowtoaddresschallengesusingtheirunique skillsandpreferencestomakesigni icantandnovel changestothekeycomponentsandarchitectureof abusinessmodel[14].Whiletheagriculturalsector requiresparticipationfrombothpublicandprivate entities,smallproducerscandeveloptheirowninno‐vativeapproachesconsideringtheiruniquecircum‐stances[15].Forinstance,inemergingeconomies suchasColombia,farmingorganizationsfacesignif‐icantobstaclesinobtainingdirectandfairaccessto variousresourcesthatcouldpotentiallyprovidecom‐petitiveadvantages.Althoughpossessingknowledge andexperienceacrossvariousdomains,theseorgani‐zationsstruggletoidentifythefactorsthatenablethe establishmentofinnovative,inclusive,andpro itable negotiationmodels.

Therefore,itisimperativetoexplorenewtheoret‐icalapproachesthatalignwiththerealitiesofthese organizations,facilitatingacomprehensivediscussion oftheirorganizationaldynamics.

Themainaimistoanalyzetheinteractionbetween innovationcapabilitiesandelementsofthebusiness modeloffarmingorganizationsinBoyacá,Colombia.It focusesonanalyzingthefactorsthataffectinnovation fromdynamiccapabilitiesperspectivewithinthebusi‐nessmodelsoftheorganizationsthatbringtogether farmers.ThisusedthePartialLeastSquaresPathMod‐eling(PLS‐PM)methodtoestimatetheproposedthe‐oreticalmodelandarepresentativesampleoffarm‐ingorganizationsinBoyacáareusedaswell.This methodexaminescomplexmultivariaterelationships betweenobservableandlatentvariables[16].Seven hypothesesareevaluatedconsideringtherelation‐shipsbetweeninnovationcapabilities(Sensing,seiz‐ing,andtransformation)andbusinessmodelinnova‐tion(creation,delivery,andvaluecapture)infarm‐ingorganizations.Findingshighlightastrongcorrela‐tionbetweeninnovationsensingandseizingcapabil‐itiesandthecreationanddeliveryofbusinessmod‐els.Thedocumentisstructuredasfollows:Section2 presentsatheoreticalfoundation.Section3showsthe methodologicalcomponenttovalidatethehypotheses suggestedinthetheoreticalmodel.Sections4and5 presentresultsandadiscussionontheestimationof themodel.Finally,Section6showstheconclusions drawnabouttherelatedelements.

2.1.DynamicCapabilities

Extensiveresearchhasbeenconductedonthe creationanddevelopmentofcompetitiveadvantages inorganizations.Previousstudieshaveanalyzedthe dynamicsofstrengthsandmeasurestomitigate potentialthreatsthatcanleadtoafavorablecom‐petitiveposition[17].Thesestudiesexaminedthe resources,capabilities,andstrategiesthatarecompa‐rableamongdifferentcompaniesinaspeci icindustry butuniqueinobtainingacompetitiveadvantage[1]. Capabilitiesareresourcesusedtogainacompetitive advantage,whosevalueisdeterminedbythemar‐ketcontext[18].Theydevelopatdifferentratesand havelifecyclesthatdemonstratehowtheyarecon ig‐uredtogenerateadvantages[19].LawsonandSam‐son[20]arguethatcapabilitiesenhancemanagement andresourceutilizationforinnovationandtechnolog‐icaldevelopmentthroughlearningprocesses,prod‐uctdevelopment,andprocessimprovement(p.379). Likewise,capabilitiesundergoacontinuousadaptive process,inwhichstrategicmanagementadjusts,inte‐grates,andrestructuresbothinternalandexternal elements,i.e.,itistheabilitytoconsistentlyreinvent capabilitiesinresponsetoachangingenvironment [21].Thus,thisperspectivesuggeststhatthedevelop‐mentofnewcapabilitiesareanopportunitytoachieve sustainableresultswithinorganizationsovertimein linewithchangingenvironments[18].

Finally,thisdynamicincapabilitiesdevelopment promotestheabilitytoinnovate,duetohowit involvesacontinuousprocessofutilizing,exploring, andexploitingknowledgetocreatenewproducts, services,orprocesses[6].Indeed,innovationinthis dynamicisknownasinnovationcapability,foritis constantlyengagedintheuse,exploration,andhar‐nessingofknowledge.Hence,innovationcapability translatesknowledgeintopioneeringproductsand servicesthatcanadapttotheever‐changingenviron‐ment[4].

Innovationcapabilitiesarepartofadynamicpro‐cessthatcanbeexplainedbythemicro‐foundations ofsensing,seizing,andtransforming[2].Sensing involvesidentifyingopportunitiesthroughskillssuch asexploration,knowledgegeneration,andnetwork‐ing.Thisprocessincludesdiscoveryandexploration ofknowledgeforsubsequentabsorptionandexploita‐tion[4, 22].Likewise,theknowledgeandinforma‐tionacquiredcanbeusedtoexploitopportunitiesin variousindustriesandmarkets.Seizingcapabilities involvestheef icientexploitationoftheseopportuni‐ties,providingacompetitiveadvantagebycapitaliz‐ingonemergingtrendsandadvancements[6].Trans‐formationcapabilitiesarevitalforlong‐termcom‐petitiveness,astheyalloworganizationstoadaptby recon iguringresourcesandprocesses[6].Transfor‐mationprocessenablestheuseofknowledgeinthe formofinnovation,transfer,orexploitationthatis appropriatefortheorganization[4].Indeed,ithigh‐lightstheimportanceofhavingstrongleverageand transformationcapabilitiestoachievesustainedcom‐petitiveadvantage[3].Thus,thesemicrofoundations canbeunderstoodasastagedmodelwithasignif‐icantinterdependencebetweenitselementsforits developmentinorganizations[23–25].Eachstageis crucialforthedevelopmentofinnovationcapabilities inorganizations.Inthatsense:

H1a:TheSensingcapacityisthedeterminingfac‐torfortheexistenceofaseizingcapacity.

H1b:Seizingcapacitiesareadeterminingfactorfor theexistenceoftransformativecapacities.

2.2.1.BusinessModelInnovation

Thebusinessmodeliscriticaltothedynamicabil‐ityofanorganizationtoadaptandsucceedinanever‐changingenvironment,anditssigni icanceliesinthe strategicpositioningoftheorganizationwithinthe valuechain[6],re lectingchangesinthefundamental elementsandarchitecturalframeworkofthebusiness model[14].Businessmodelinnovationentailslever‐aginginternalandexternalresourcesandcapabilities tocreatevalue,delivernewproposalsfor irm’sseg‐ments,andgeneratesustainablepro its,ensuringthat revenuecoverscosts[26].Thisinnovationprocess mayfollowasequentialtrajectory,markedbydistinct featuresfortransitioningfromonestagetothenext [23–25].

Notably,businessmodelinnovationcanmanifest invariousdimensions,includingshiftsinindustry mindset,alterationsinthedeliveryofvalue,andadap‐tationsintheconditionsforcapturingvalue[23].In essence,businessmodelinnovationinvolvestheinte‐grationofthethreevaluedomainstocreateinnova‐tion,deliverproducts,services,technology,andinfor‐mation lowsofycapturevalueinagrowthcycle[26]. Inthatsense:

H3a:Innovationincreatingvalueiscriticaltoinno‐vatingindeliveringvalue,

H3b:Innovationindeliveringvalueiscriticalto innovatingincapturingvalue.

2.2.2.SensingandValueCreationCapabilities

Identifyingbusinessopportunitiesthatarisefrom marketandindustrytrendsiscrucialforbusiness modelinnovation.Theabilitytosensetheseoppor‐tunitiesisessentialforadaptingtoadynamicenvi‐ronment[24,27].Toidentifynewopportunities,orga‐nizationsshouldengageinexploration,creation,and learningactivitiesthatenablethemtoanticipateand identifykeyenvironmentalsignals[23].Thesesignals willenablegreater lexibilityinadaptingandcontin‐uouslyrenewingtheorganization’sunderlyingbusi‐nessmodel[28].Valuecreationnecessitatescontinu‐ousobservationoftheenvironmentbeyondthecur‐rentcustomer.Itiscrucialtopossessanexploratory capabilitythatcanidentifyopportunities[26]togain abetterunderstandingofopportunitiesandthreats [29].Tocomprehendthesigni icanceofintegrating newknowledgewiththeorganization’scapabilitiesto createculturalandeconomicvalue,aconvergentview oftheorganizationisessential.Kianietal.[30]argue thatintegratinginadynamicenvironmentiscrucial foranorganization’ssuccess.Inthatsense:

H2a:Sensingcapabilitiesin luenceinnovationin thevaluechainofagriculturalorganizations.

2.2.3.SeizingCapabilitiesandValueDelivery

Duringtheseizingstage,organizationsaimto recombinetheirtechnology,resources,knowledge, andmarkettotakeadvantageofemergingopportuni‐ties.Theseopportunitiestypicallymanifestaschanges intheorganization’svaluedelivery,suchasnewprod‐ucts,processes,orservices.However,tomaintainand improvetechnologicalcompetencies,itisnecessary toinvestindesignandprocesses,striveforqual‐ityimprovement,andmakenecessaryinvestmentsto gainmarketacceptance[2].Thistypeofchangeoften generatestensions,soitisimportanttopossessskills tomanageexpectationsandfosteracceptanceand buy‐ininthefaceofdefensiveattitudesthatmayarise duringtheprocess[23].Changestothevaluedeliv‐eryarecrucialastheydirectlyimpactthesolutions offeredtocustomersandhowtheyarepresented.Itis essentialforanorganization’ssuccessinscalingnew productsandservicesandenhancingthecustomer offeringtoincorporateseizingcapabilities[26, 30]. Thus,therenewalprocesscannotbecompletedsolely withtheexistingresourcebase.

Totakeadvantageofmarketopportunities,itis recommendedtodevelopnewcapabilities,createa differentoffering,andfosteraculturethatreduces resistancetochangeduringthetransitionperiod[24]. Keyelementsforsuccessaredeliveringvalueand innovation.Inthatsense:

H2b:Seizingcapacityin luencesinnovationinthe valuedeliveryofagriculturalorganizations.

2.2.4.TransformationandValueCaptureCapabilities Transformationalcapacityisessentialforachiev‐ingsustainabilityandiscloselylinkedtosustaining thenewbusinessmodel.Itenablestheorganization toshareitsknowledgewiththeoutsideworldto reapbene its[31].Thiscapabilityisconsideredthe inalstageintheprocessofstructuralinnovationand sustainabilityofthebusinessmodel[25].Ensuring sustainableperformancerequiresunderstandinghow irmsgeneratecost‐coveringrevenuesandpro its [26].Valuecaptureinvolvesnotonlysettingpricesbut alsoconsideringfactorssuchastimingandeffective‐ness,whichcanimpactcustomerinteractionsandthe sustainabilityofavalue‐basedpricingstrategy[32]. Hence,theabilitytorecombinecapabilitiesandadapt tochangeiscrucialinsupportingthenewbusiness modelwithexistingresources,organizationaldesign, andculture[23].Inthatsense:

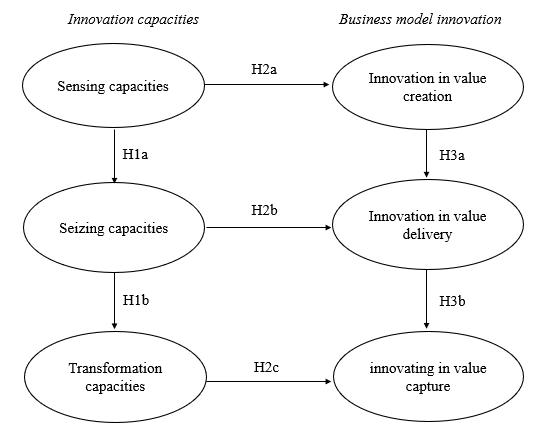

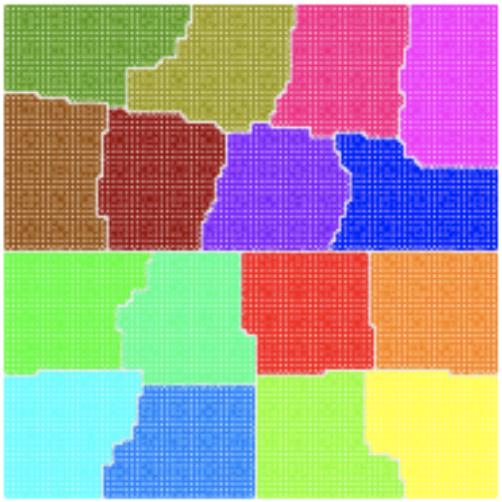

H2c:Transformationcapacityin luencesinnova‐tioninvaluecapturebyagriculturalorganizations. Oncethehypothesesofthetheoreticalmodelhave beenpresented,theyareconsolidatedinFigure1:

Thepaperanalyzesnumericaldatatotest hypothesesthatsupporttheproposedtheoretical modelforidentifyingthedeterminantsofinnovation capabilitiesinbusinessmodelsoffarming organizations.ThePLS‐PMmethodisutilizedto estimatetherelationshipcoef icientsandvalidate thehypotheses.Thismethodisdevelopedintwo stages,allowingforcreatingindicesassociatedwith unobservabletheoreticalvariablesandestablishing theirstatisticalrelationships.

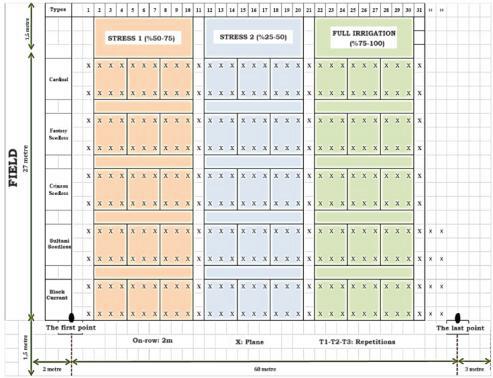

Asampleof65agriculturalorganizationspar‐ticipatingintheProductiveAlliancesProgrammeof theMinistryofAgricultureandRuralDevelopment inBoyacá‐Colombiaisconsidered.Theinformation collectionwascarriedoutduringJanuaryandFebru‐ary2023,wherevisitsweremadedirectlytothe companies’establishments,andevenwhentheman‐agerswereabsent,appointmentsweremadewith themtoapplytheinstrumentonanotherdate.The UniversidadPedagogicayTecnologicadeColombia (UPTC)EthicsCommitteereviewedthisresearch project,andeachoftheparticipantsreadandsigned theinformedconsentform,agreeingtoparticipate intheresearchprojectanonymously.Thesample wasobtainedthroughsimplerandomsamplingand includedindividualsfrom13provinceswithinthe department.Theprovinceswiththehighestpar‐ticipationrateswereTundama(18.5%),Occidente (16.9%),Centro(15.4%),andSugamuxi(12.3%)(see Table1).Intermsofeconomicactivities,theorganiza‐tionsmainlyengageinfruittreecultivation(27.7%), cattleandmilkproduction(20%),vegetablefarm‐ing(15.4%),andpotatocultivation(13.8%).Notably, 81.5%oftheorganizationsinthesampleareestab‐lishedasassociations,and70%haveamembershipof 20ormoreindividuals.

3.1.Instrument

Thepurposeofthisstudyistoestablishthecor‐relationbetweenvariablesrelatedtodynamicinno‐vationcapabilitiesandbusinessmodelcapabilities,as illustratedinFigure1.Theinstrumentusedincludes characteristicsrelatedtosixinnovationcapabilities thatareessentialtoadynamicprocess:learningorien‐tation,relationships,strategicdirection,creativecul‐ture,productandservicedevelopmentorimprove‐ment,andadaptabilityuseda5‐pointLikertscale [33].Furthermore,businessmodelinnovationispur‐suedwithafocusoncreatingvaluethroughtechnol‐ogy,processes,andpartnerships.Thevaluedelivered relatestotheinteractionbetweenorganizations,cus‐tomers,andmarkets.Finally,valuecaptureisassessed fromtheperspectiveofresourcemanagementandthe creationofinnovativecostandrevenuestructures. TheseapproachesareshowninTable2

3.2.MethodofEstimation:PartialLeastSquares–Path Modeling(PLS‐PM)

Totestthehypothesesinthetheoreticalframe‐work,weuseStructuralEquationModeling(SEM) methodology.SEMisawidelyusedmultivariateana‐lyticaltoolinscienti icresearchthatcombinesmea‐surablevariableswithunobservedvariablestopro‐ducepreciseresults[16, 49, 50].Theprocessof SEMinvolvestwostages.The irststepinvolves estimatingtheexternalmodeltoestablishrelation‐shipsbetweenlatentvariablesorevaluateassociated indices.Thesubsequentstepinvolvesestimatingthe internalmodeltofocusoncausalityordependence relationships.

Thegoalistovalidateorinvalidateproposed hypothesesbyestimatingtherelationshipcoef icients (Path)usingOrdinaryLeastSquares(OLS)[50–53]. ThisstudyemploysthePLS‐PMmethod,whichuses groupsofobservablevariablestocreateadataset associatedwiththetheoreticalconcept.Tovalidate theconstruct,statisticaltestssuchasCronbach’s AlphaandDillonGoldstein’sRhoareapplied,and parametersareestimatedusingOLS.Thevalidation isachievedthroughstatisticaltestssuchast‐tests andbootstrapping[18,31,49,50,52,53].Toperform thesecalculations,weusedthePLS.PMlibraryinthe Rprogramminglanguage[53].

4.1.ExternalModel

Toevaluatethestatisticalvalidityofthequestions andmeasurementoflatentvariablesintheproposed theoreticalmodel,weperformedaCon irmatoryFac‐torAnalysis(CFA)usingtheinstrument.Theanalysis comprisesfourindicators:Cronbach’sAlpha,which measuresthepercentageofvarianceexplainedby thesetofmanifestvariablesforthelatentvariable [49,54];TheDillonGoldsteinRho,whichdetermines thelevelofvariationamongasetofvariables;and theloadingcoef icient,whichillustratestheexplained varianceofeachmanifestvariableintheinstrument. Furthermore,thecommunality,whichisthesquareof theloadingcoef icient,ishighlycorrelatedwiththe loadingcoef icient(seeTable3).

Toensurethevalidityofquestions,itisnecessary toachieveanoptimalCronbach’sAlphavalueof0.7 orgreater[52].Additionally,anoptimalDillonGold‐stein’sRhovalueshouldbeequaltoorgreaterthan 0.7.Whenvalidatingindividualquestions,itisneces‐sarytohavealoadingof0.7orgreaterandacommu‐nalitygreaterthan0.7,whichindicatesacommunality valueofatleast50%.Table 3 displaystheresultsof theCFAperformedontheblocksofobservablevari‐ables.Theanalysiscon irmsthevalidityandstatistical robustnessoftheobtainedvalues,validatingtherel‐evanceofeachobservablevariableinexplainingthe hypotheses.Thus,theproposedexternalmodelforthe researchiscon irmed.

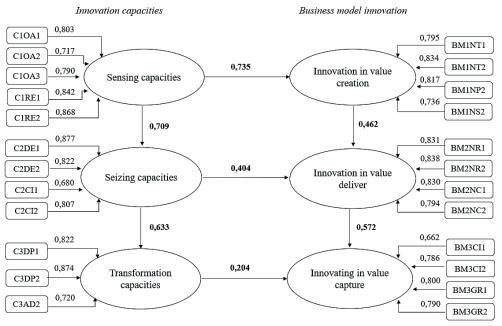

4.2.InternalModel

Thissectiondiscussestheassessmentofpath orrelationshipcoef icientsbetweenlatentvariables, includingtheirdirectionandmagnitude.Theesti‐matedeffectsdemonstrateapositivedirection,which supportsthehypothesis(seeTable4).Quotationsare clearlymarked,and illerwordsareavoided.Addi‐tionally,medium‐strongrelationshipsbetweenSens‐ingandSeizingcapabilityareobserved(H1a0.709). Organizationsfacechallengesinobtainingandadapt‐ingtheknowledgerequiredforinnovation[22].To achievegreaterknowledgeappropriationandiden‐tifyopportunitiestogeneratevalue,effectiveprac‐ticesincludeallianceandrelationshipmanagement [24,55].

Table1. Distributionoforganizationsbyprovinceandeconomicactivity

Table2. Theoreticalstructureoftheproposedinstrument

Table3. Evaluationmeasurementresults

Thecorrelationcoef icientof0.633betweenseiz‐ingcapacityandtransformationsuggestsadirectand moderaterelationship(H1b).Intheagriculturalsec‐tor,itisimportanttoestablishinfrastructuresthat facilitatethecreationandre inementofproductsor services.Thisrequirescooperativenetworkstoassim‐ilateessentialknowledgenecessaryforcollaborative innovation[37,44].

Asigni icantassociationwasfoundbetween sensingandvaluegeneration(H2a0.735). Sensinginvolvesinvestigating,producing,and acquiringknowledgetoanticipateandrecognize environmentalcuesthatenablebetterunderstanding ofopportunitiesandthreats[23].Additionally, buildingandmaintainingprofessionalrelationships isacrucialfactorincreatingvalue.Thiscapability allowsorganizations,particularlythosewithlimited resourcesandtechnicalexpertise,todiscoverand accessnewideas,technologies,processes,projects, resources,contacts,andproductsorservices[12].

Table4. Resultsandvalidationofhypotheses Hypotheses

Theresultsindicatemoderaterelationships,such asthecorrelationbetweentheseizingvariableand innovationinvaluedelivery(H2b).Toencouragecol‐lectiveaction,agriculturalorganizationsshouldprior‐itizethedevelopmentof lexibleorganizationalpro‐cessesandcommunicationmechanismstoimprove theirproductionsystems.Incorporatingcultureinto innovationstrategiesiscrucialforaddressingprocess inef icienciesandfacilitatingchangetotakerisks[12, 40,56].

Thecorrelationbetweenvaluecreationandvalue delivery(H3a0.462)suggeststhatestablishingcon‐nectionswithvariousstakeholdersfacilitatescollab‐orativeknowledgegeneration[45].Internalpartner‐shipshavebeendemonstratedtobecriticalfororgani‐zations.However,asorganizationsexpandandpros‐per,newemployeesfacesigni icantobstaclesdue totheresultingincreaseinthecomplexityoftheir workscenarios.This indingsupportsthathigherlev‐elsoforganizationalcomplexityareassociatedwith increasedintensityandimprovedqualityofinterac‐tions.

Intermsofinnovationinvaluedeliveryand valuecapture(H3b0.572),adirectrelationshipexists withthebusinessmodelthatenableshigherreturns. However,bene itsarenotlimitedtocommercializa‐tion.Effectivemanagementofexternalresourcesthat alignswithsocio‐entrepreneurialempowermentis alsocrucial.Valuecaptureheavilyreliesonfavorable policiesandinstitutionalarrangementsthatsupport collectiveaction[57].

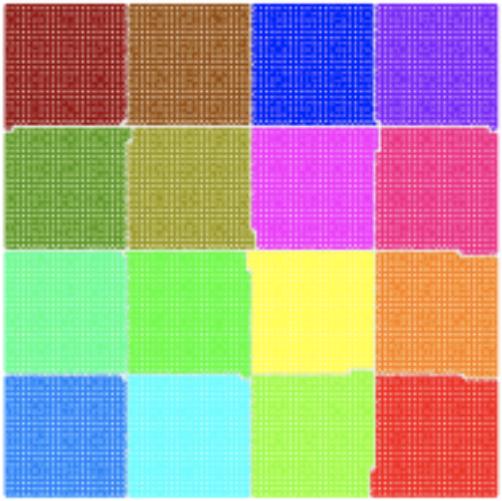

H2cwasrejected(0.204),indicatingnocorrelation betweentransformationcapacityandvaluecapture. Thisoutcomemaybeattributedtoorganizationalfac‐tors,speci icallythecomplexityofdecision‐making processeswithinboardsthatrequiretheparticipation ofallmembers,ultimatelylimitingadaptability.Addi‐tionally,theseorganizationshavebotheconomicand socialobjectives,whichcouldleadtoadifferentinter‐pretationofthevaluecaptureprocess[23].Thestudy foundthat43%ofparticipantsdidnotparticipate injointmarketingactivities.Instead,theyreceived alternativebene itssuchasknowledge,relationships, status,orvisibility.Figure 2 showsthevalidationof theproposedtheoreticalmodelandtherelationship coef icients.

Hypotheses

Validated***

Validated***

Validated***

Thereisadirectcorrelationbetweenanorgani‐zation’ssensingandseizingcapabilitiesanditsabil‐itytoinnovate,bothinthedeliveryandcreationof value.Thesecapabilitiesenable irmstoidentifynew ideasandresources,receivetrainingandtechnical assistance,anddevelopstrategiesforgreaterbargain‐ingpower.However,thereisnoclearrelationship betweenanorganization’stransformationalcapabili‐tiesanditsabilitytocapturevalue.Thereisasigni i‐cantneedtodevelopskillsthatfacilitatetheenhance‐mentandcreationofproductstoestablisharobust valueproposition.

Thisresearchdelvesintotheintricaterelationship betweeninnovationcapabilitiesandtheevolutionof thebusinessmodelinagriculturalorganizationsin Boyacá,Colombia.TheRBVperspectiveunderscores thesigni icanceofinternalfactorsforcompetitive‐ness,emphasizinginnovationasadynamicprocess capableofleveragingknowledgetofosterorganiza‐tionaladaptability[4,14].

ThestudyconductedbyKianietal.[30]shows asigni icantcorrelationbetweeninnovation,sensing, andseizingcapabilities.Thisemphasizestheimpor‐tanceofcontinuouslearningandeffectiveknowledge management,whicharecrucialforfarmingorganiza‐tions.Theprocessofdetectingandadaptingknowl‐edgecloselyalignswiththeuseoftechnologiesin theproductionsystem.However,organizationsfacea challengeinassimilatingknowledgetomobilizethe necessarytechnicalandeconomicsupportforinnova‐tion[22].

Alliancemanagementisarecurringandeffec‐tivepracticeforacquiringandadaptingknowledge [55].Theabilitytobuildrelationshipsisessentialfor identifyingopportunitiesandinvolvinggovernmental, private,ornon‐pro itactorsinanopeninnovation approach[39].Constructingnetworksthatinvolve diverseactorsisawaytoabsorbexternalknowledge andexposetheorganizationtonewstimuliandexpe‐riences.Duringtheseizingstage,itiscrucialtohigh‐lighttheimportanceofstrategicdirectionandaddress anyculturalchallengesthatmayhinderthepercep‐tionoflessonslearnedasopportunitiesforinnovation [8].Organizationalcultureplaysacriticalroleinthe innovationstrategy,aslessonslearneddonotalways translateintoopportunitiesforfurtherlearningand experimentation.Thetransformationstageshowsa directandmoderaterelationship,highlightingthe importanceofdevelopinginnovationcapabilitiesfor productsandservices[45].Intheagriculturalcontext, cooperativenetworksemphasizeco‐creationascru‐cialforproductdevelopment,representingatangible manifestationofinnovation[44].Inthe ieldofbusi‐nessmodelinnovation,thereisamoderatecorrelation betweenvaluecreationandvalueproposition.Effec‐tiverelationshipmanagementwithstakeholdersfrom boththepublicandprivatesectors,aswellasinternal collaborationsamongteammembers,iscrucial.How‐ever,thesecollaborationsoftenencounterchallenges thatcanraiseentrybarrierswithinorganizationsand complicatecoordination.

Therelationshipbetweensensingcapabilitiesand innovationinvaluecreationissigni icant,highlighting thecomplementaritybetweentheseconcepts.Sensing capabilitiesplayacrucialroleinexploring,creating, andlearningtoanticipateanddetectenvironmental signals.Relationship‐buildingisalsofundamentalfor organizationswithlimitedresources.Althoughagri‐culturalorganizationsgeneratevaluethroughexter‐nalproductsandservices,itisimportanttohighlight theirroleinstrengtheninginternalbondswithasso‐ciates,ortheirsocialcapital.Therelationshipbetween seizingcapabilitiesandinnovationinthevaluepropo‐sitionisdirectandmoderate,underscoringtheneed for lexibleorganizationalprocessesandtheincorpo‐rationofcultureintotheinnovationstrategy.There isnoclearrelationshipbetweentransformationcapa‐bilitiesandvaluecapture.Thislackofcorrelationcan beattributedtothefactthatparticipatingorganiza‐tionsarerelativelyyoungandfocusedonimmediate growth,whichexplainsthelowsigni icanceoftrans‐formationcapabilities.Thedualpurposeofagricul‐turalorganizations,whichpursuebotheconomicand socialobjectives,createsdivergencesinvaluecap‐ture.Furthermore,thelimitedcontroloverproduction costsrestrictstheimpactoftransformationcapabili‐tiesinthisaspect.

However,itispossibletocapturevaluethrough thesensingprocessbycreatingproposalsthatalign withtheneedsofbothinternalandexternalclients.In conclusion,thisresearchhighlightstheimportanceof improvinginnovationcapabilitiesthroughcontinuous learning,effectiveknowledgemanagement,external collaboration,andaninnovationstrategythatcon‐sidersbothculturalandeconomicaspects.Internal andexternalcollaboration,alongwithdiversi ication oftheproductoffering,emergeaskeyelementsfor thesuccessofagriculturalorganizationsinthiscon‐text[24].Futureresearchshouldthoroughlyexplore thedynamicsoftransformationcapabilitiesinmore matureorganizationsandenvironments.Additionally, ananalysisofthespeci icimpactofdivergencesin economicandsocialobjectivesonvaluecaptureissug‐gested.Theseareascouldprovidevaluableinsightsto furtheradvancethe ieldofstudy.

Thestudyusesthedynamiccapabilitiesframe‐worktoidentifyinnovationcapabilitiesinfarming organizationsoperatinginBoyacá,adepartmentin Colombia,andtoestablishtheirrelationshipwith theinnovationelementsinthebusinessmodel.The identi iedinnovationcapabilitiesenableacompre‐hensiveinnovationassessmentacrossvariousdimen‐sions,includinglearningandculture.Therelationship betweeninnovationcapabilitiesandtheelementsof thebusinessmodelofagriculturalorganizationsindi‐catesthatsensingandseizingcapabilitiesaffectthe processesofvaluecreationanddelivery,primarily throughcapabilitiessuchasrelationshipsandlearn‐ing.Sharingknowledgeandexperienceswithexter‐nalactorscanfacilitatethecreationofopeninnova‐tionscenarios,bene itingorganizationswithlimited resourcesandcapabilitiesingeneratingnewideas. However,ithasbeenfoundthattransformationcapa‐bilitiesdonotplayacriticalroleinthevaluecap‐tureprocess.Duetobarriersthathinderthedevel‐opmentofinnovationcapabilities,suchasdiscrepan‐ciesbetweensocialandeconomicgoalsandconvo‐lutedparticipatorystructuresthatobstructdecision‐makingandadaptation,theinnovationprocessmay notplayacrucialroleintheprocessofvaluecapture. Theresearchaimstomeasureinnovationand identifyinnovativecapacitiesinrural,peasant,and associativeworkcontexts.Theseareasoftenfacechal‐lengesandshortcomingsindevelopingpro itableeco‐nomicactivities.Theinformationobtainedcanassist decision‐makersandactorsoftheNationalAgricul‐turalInnovationSystem(NAIS)inpromotinginnova‐tion.These indingscanaideconomicdevelopment practitionersincraftingstrategiesthatarecongruent withtheirlocales.Additionally,thismethodologymay beespeciallybene icialforruralareasthathavenot yetfullyintegratedintotheglobaleconomy.

Theprimarylimitationofthisstudyisitsnar‐rowfocusonaspeci icregioninColombia,withan emphasisonagricultureandlivestock.Therefore,itis recommendedthatfutureresearchinvestigateother contextstosupplementthese indings.Toadvance researchinthisarea,itisrecommendedthatefforts focusondevelopingstrategiesthatpromotetrans‐formationalcapabilitiestoachievesustainabilityand competitiveadvantage.

AUTHORS

DanielaNiño-Amezquita∗ –FacultyofEconomics andAdministrativeSciences,UniversidadCatólicade laSantísimaConcepción,Concepción,Chile,e‐mail: dnino@doctorado.ucsc.cl.

JhancarlosGutiérrez-Ayala –FacultaddeCiencias EconómicasyAdministrativas,UniversidadPedagóg‐icayTecnológicadeColombia,Av.CentraldelNorte, 39‐115,150001,Tunja,Colombia,e‐mail:jhancar‐los.gutierrez@uptc.edu.co.

DianaMaríaDueñasQuintero –CentroRegionalde GestiónparalaProductividadylaInnovacióndeBoy‐acá(CREPIB),Av.CentraldelNorte,39‐115,150001, Tunja,Colombia,e‐mail:diana.duenas@crepib.org.co.

FabioBlanco-Mesa –FacultaddeCiencias EconómicasyAdministrativas,Universidad PedagógicayTecnológicadeColombia,Av.Central delNorte,39‐115,150001,Tunja,Colombia,e‐mail: fabio.blanco01@uptc.edu.co.

EduardoCovarrubias-Audelo –EscuelaNormalde Sinaloa,BlvdManuelJ.ClouthierS/N,Col.Liber‐tad,C.P80180,Culiacán,Sinaloa,México,e‐mail: eduardoaudelo8@gmail.com.

∗Correspondingauthor

ThisprojectwassupportedbyMinisteriodeCiencia, TecnologíaeInnovación,MincienciasandUniversidad PedagógicayTecnológicadeColombia75878.Also, ResearchsupportedbyRedSistemasInteligentesy ExpertosModelosComputacionalesIberoamericanos (SIEMCI),projectnumber522RT0130inPrograma IberoamericanodeCienciayTecnologíaparaelDesar‐rollo(CYTED).

Wedeclarethatthedatacollectedinthisresearch areunderprotectionasdeterminedbytheethicscom‐mitteeforresearchoftheUniversidadPedagógica yTecnologíadeColombia(UPTC)andwillonlybe shareduponrequesttosaidcommitteethroughthe emailcomite.eticainvestigacion@uptc.edu.co

[1] L.Achtenhagen,L.Melin,andL.Naldi,“Dynamics ofBusinessModels‐Strategizing,CriticalCapa‐bilitiesandActivitiesforSustainedValueCre‐ation,” LongRangePlanning,vol.46,no.6,2013, pp.427–442;https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.20 13.04.002

[2] V.G.Alfaro‐García,A.M.Gil‐Lafuente,andG.G. AlfaroCalderón,“AFuzzyMethodologyforInno‐vationManagementMeasurement,” Kybernetes, vol.46,no.1,2017,pp.50‐66;https://doi.org/ 10.1108/K‐06‐2016‐0153

[3] K.AmofahandR.Saladrigues,“ImpactofAttitude towardsEntrepreneurshipEducationandRole ModelsonEntrepreneurialIntention,” Journalof InnovationandEntrepreneurship,vol.11,no.1, 2022;https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731‐022‐00197‐5

[4] C.Baden‐FullerandS.Hae liger,“BusinessMod‐elsandTechnologicalInnovation.” LongRange Planning,vol.46,no.6,2013,pp.419‐426.

[5] J.Barney“FirmResourcesandSustainedCom‐petitiveAdvantage,” JournalofManagement,vol. 17,no.1,1991,pp.99‐120.

[6] J.B.Barney,“Resource‐BasedTheoriesofCom‐petitiveAdvantage:ATen‐YearRetrospectiveon theResource‐BasedView,” JournalofManagement,vol.27,no.6,2001,pp.643‐650.

[7] M.E.ABarreraandH.Gutiérrez,“Desigualdad deGéneroyCambiosSociodemográ icosen México,” Nóesis:RevistadeCienciasSocialesy Humanidades,vol.26,no.51,2017,pp.2‐19.

[8] M.I.Barrettetal., BeingInnovativeAboutServiceInnovation:Service,DesignandDigitalization,ICIS,2012.

[9] M.T.Bastanchury‐Lópezetal.,“Reviewofthe MeasurementofDynamicCapacities:AProposal ofIndicatorsfortheSheepin,” CienciayTecnologíaAgropecuaria,vol.20,no.2,2019,pp. 355‐386.

[10] C.Battistellaetal.,“CultivatingBusinessModel AgilitythroughFocusedCapabilities:AMultiple CaseStudy,” JournalofBusinessResearch,vol. 73, 2017,pp.65‐82.

[11] S.Behnam,R.Cagliano,andM.Grijalvo,“How ShouldFirmsReconciletheirOpenInnovation CapabilitiesforIncorporatingExternalActorsin InnovationsAimedatSustainableDevelopment,” JournalofCleanerProduction,vol.170,2018,pp. 950‐965.

[12] B.Bestetal.,“MissionorMargin?UsingDynamic CapabilitiestoManageTensionsinSocialPur‐poseOrganisations’BusinessModelInnovation,” JournalofBusinessResearch,vol.125,2021,pp. 643‐657.

[13] J.BjörkdahlandS.Börjesson,“AssessingFirm CapabilitiesforInnovation,” InternationalJournalofKnowledgeManagementStudies,vol.5,no. 1‐2,2012,pp.171‐184.

[14] F.Blanco‐Mesaetal.,“MedicióndelasCapaci‐dadesdeInnovaciónenTresSectoresPrimarios enColombia,” EfectosOlvidadosdelasCapacidadesdeInnovacióndelaQuínoa,laGuayabay ApícolaenBoyacáySantander,RealAcademiade CienciasEconómicasyFinancieras,2019.

[15] N.Bockenetal.,“TheFront‐EndofEco‐InnovationforEco‐InnovativeSmallandMedium SizedCompanies,” JournalofEngineeringand TechnologyManagement,2014,vol.31,pp. 43‐57.

[16] M.Castillo‐VergaraandE.TorresAranibar,“El PapeldelaCooperaciónparaDesarrollarInno‐vaciónTecnológicaenlaPYME,” JournalofTechnologyManagementandInnovation,vol.14,no. 4,2019,pp.41‐53.

[17] J.CepedaandJ.Arias‐Pérez,“InformationTech‐nologyCapabilitiesandOrganizationalAgility: TheMediatingEffectsofOpenInnovationCapa‐bilities,” MultinationalBusinessReview,vol.27, no.2,2019,pp.198‐216.

[18] W.W.Chin,“ThePartialLeastSquaresApproach toStructuralEquationModeling,” ModernMethodsforBusinessResearch,vol.295,no.2,1998, pp.295‐336.

[19] U.R.Christaetal.,“TheRoleofValueInnovation CapabilitiesintheIn luenceofMarketOrienta‐tionandSocialCapitaltoImprovingthePerfor‐manceofCentralKalimantanBankinIndonesia,” JournalofOpenInnovation:Technology,Market, andComplexity,vol.6,no.4,2020,pp.140.

[20] T.Clauss,“MeasuringBusinessModelInnova‐tion:Conceptualization,ScaleDevelopment,and ProofofPerformance,” R&DManagement,vol.47, no.3,2017,pp.385‐403.

[21] A.R.Cummings,“ConstruyendoCapacidades deInnovaciónenIniciativasAsociativas dePequeñasAgroindustriasRuralesenEl Salvador,” RevistaIberoamericanadeCiencia TecnologíaySociedad,vol.8,no.24,2013,pp. 295‐319.

[22] M.DeSilva,O.Al‐Tabbaa,andZ.Khan,“Business ModelInnovationbyInternationalSocialPur‐poseOrganizations:TheRoleofDynamicCapa‐bilities,” JournalofBusinessResearch,vol.125, 2021,pp.733‐749.

[23] M.J.Donate,I.Peña,andJ.D.SanchezdePablo, “HRMPracticesforHumanandSocialCapi‐talDevelopment:EffectsonInnovationCapa‐bilities,” TheInternationalJournalofHuman ResourceManagement,vol.27,no.9,2016,pp. 928‐953.

[24] H.R.Espinosa,C.J.RGómez,andL.F.R.Betancur, “FactoresDeterminantesdelaSostenibilidadde

lasAgroempresasAsociativasRurales,” Revista deEconomiaeSociologiaRural,vol.56,2018,pp. 107‐122.

[25] J.F.HairJretal.,“PartialLeastSquaresStruc‐turalEquationModeling(PLS‐SEM)AnEmerg‐ingToolinBusinessResearch,” EuropeanBusinessReview,vol.26,no.2,2014,pp.106‐121.

[26] R.FloresandC.Naranjo,“UsodelCapitalSocial enlaGeneracióndeAsociatividadenPequeñas OrganizacionesFamiliaresCampesinas,” Revista deTrabajoSocial,vol.73,2006,pp.99‐109.

[27] N.J.FossandT.Saebi“BusinessModelsandBusi‐nessModelInnovation:BetweenWickedand ParadigmaticProblems,” LongRangePlanning, vol.51,no.1,2018,pp.9‐21.

[28] G.N.FrancesconiandN.Heerink,“Ethiopian AgriculturalCooperativesinanEraofGlobal CommodityExchange:DoesOrganisational FormMatter,” JournalofAfricanEconomies,vol. 20,no.1,2011,pp.153‐177.

[29] I.Freije,A.delaCalle,andJ.V.Ugarte,“Roleof SupplyChainIntegrationintheProductInnova‐tionCapabilityofServitizedManufacturingCom‐panies,” Technovation,vol.118,2022,p.102216.

[30] J.French,K.Montiel,andV.PalmieriReymond, “LaInnovaciónenlaAgricultura:UnProceso ClaveparaelDesarrolloSostenible,” IICA, 2014.

[31] G.D.Garson,“PartialLeastSquares(PLS‐SEM): RegressionandStructuralEquationModels,” NorthCarolina:StatisticalPublishingAssociates, 2016.

[32] J.M.Gil‐León,J.Gutiérrez‐Ayala,andE.A. Ramírez‐Hernández,“ElPapeldelTurismo PatrimonialenelIndicedeCompetitividad TurísticaRegionaldeColombia:UnaEvaluación deLasRelacionesMediantePLS‐PM,” Revista EAN,vol.90,2021,pp.169‐192.

[33] A.González‐Moreno,F.J.Sáez‐Martínez,andC. Díaz‐García,“AttitudestowardsEco‐Innovation intheChemicalIndustry:PerformanceImplica‐tions,” EnvironmentalEngineeringandManagementJournal,vol.13,no.10,2014,pp.2431‐2436.

[34] C.E.HelfatandM.A.Peteraf,“TheDynamic Resource‐BasedView:CapabilityLifecycles,” StrategicManagementJournal,vol.24,no.10, 2003,pp.997‐1010.

[35] J.M.Huesca‐Mariñoetal.,“ElExtensionismoen ProgramasAgrícolasRegionales:PlanPuebla yMasAgro,” Estudiossociales.Revistadealimentacióncontemporáneaydesarrolloregional, vol.29,no.53,2019.

[36] M.N.Kiani,M.Ahmad,andS.H.MGillani“Service InnovationCapabilitiesasthePrecursortoBusi‐nessModelInnovation:AConditionalProcess Analysis,” AsianJournalofTechnologyInnovation, vol.27,no.2,2019,pp.194‐213.

[37] B.LawsonandD.Samson,“DevelopingInno‐vationCapabilityinOrganisations:ADynamic CapabilitiesApproach,” InternationalJournalof InnovationManagement,vol.5,no.3,2001,pp. 377‐400.

[38] U.LichtenthalerandE.Lichtenthaler,“A Capability‐BasedFrameworkforOpen Innovation:ComplementingAbsorptive Capacity,” JournalofManagementStudies, vol.46,no.8,2009,pp.1315‐1338.

[39] H.‐M.LinandC.‐C.Tsai,“ConceptionsofLearning ManagementamongUndergraduateStudentsin Taiwan,” ManagementLearning,vol.39,no.5, 2008,pp.561‐578.

[40] M.MuhicandL.Bengtsson,“DynamicCapabili‐tiesTriggeredbyCloudSourcing:AStage‐Based ModelofBusinessModelInnovation,” Reviewof ManagerialScience,vol.15,no.1,2021,pp.33‐54.

[41] M.Mutenjeetal.,“AgriculturalInnovationsand FoodSecurityinMalawi:GenderDynamics, InstitutionsandMarketImplications,” TechnologicalForecastingandSocialChange,vol.103, 2016,pp.240‐248.

[42] D.Niño‐AmézquitaandD.M.D.Quintero,“Inno‐vationCapabilitiesinBusinessModelsforAgri‐culturalOrganizations:TheoreticalApproaches,” InnovationandSustainabilityinGovernmentsand Companies:APerspectivetotheNewRealities, RiverPublishers,2023,pp.159‐181.

[43] A.OsterwalderandY.Pigneur, Generaciónde modelosdenegocio,2011.

[44] M.E.Porter, CompetitiveAdvantage:Creatingand SustainingSuperiorPerformance,FreePress,vol. 43,1985,p.214.

[45] A.V.PrietoandC.S.Álvarez,“AnálisisdeEvolu‐cióndelaAsistenciaTécnicayelFomentode CooperativasRuralesenColombia,” Cooperativismo&Desarrollo,vol.28,no.116,2020,pp. 1‐22.

[46] R.Ramos‐Sandoval,J.M.G.Álvarez‐Coque,andF. Mas‐Verdú,“InnovativeCapabilitiesofUsersof AgriculturalR&DServices,” RegionalSciencePolicy&Practice,vol.11,no.2,2019,pp.295‐306.

[47] C.P.Ribau,A.C.Moreira,andM.Raposo, “SMEsInnovationCapabilitiesandExport Performance:AnEntrepreneurialOrientation View,” JournalofBusinessEconomicsand Management,vol.18,no.5,2017,pp.920‐934.

[48] V.SachitraandS.‐C.Chong,“Resources,Capa‐bilitiesandCompetitiveAdvantageofMinor ExportCropsFarmsinSriLanka:AnEmpirical Investigation,” CompetitivenessReview:AnInternationalBusinessJournal,vol.28,no.5,2018,pp. 478‐502.

[49] G.Sanchez, PLSPathModelingwithR.,Trowchez Editions,vol.383,2013,p.551.

[50] A.Setyawatietal.,“LocusofControl,Environ‐ment,andSmall‐MediumBusinessPerformance inPilgrimageTourism:TheMediatingRoleof ProductInnovation,” Heliyon,vol.10,no.9,2024.

[51] B.A.Shiferaw,J.Okello,andR.V.Reddy,“Adop‐tionandAdaptationofNaturalResourceMan‐agementInnovationsinSmallholderAgricul‐ture:Re lectionsonKeyLessonsandBestPrac‐tices. Environment,DevelopmentandSustainability,vol.11,2009,pp.601‐619.

[52] D.J.Teece,“ExplicatingDynamicCapabilities: TheNatureandMicrofoundationsof(Sustain‐able)EnterprisePerformance,” StrategicManagementJournal,vol.28,no.13,2007,pp.1319‐1350.

[53] D.J.Teece,“BusinessModels,BusinessStrategy andInnovation,” LongRangePlanning,vol.43, no.2‐3,2010,pp.172‐194.

[54] D.J.Teece,“ADynamicCapabilities‐Based EntrepreneurialTheoryoftheMultinational Enterprise,” TheEclecticParadigm:AFramework forSynthesizingandComparingTheoriesof InternationalBusinessfromDifferentDisciplines orPerspectives,Springer,pp.224‐273.

[55] D.J.Teece,G.Pisano,andA.Shuen,“Dynamic CapabilitiesandStrategicManagement,” StrategicManagementJournal,vol.18,no.7,1997,pp. 509‐533.

[56] J.A.Turneretal.,“UnpackingSystemicInnova‐tionCapacityasStrategicAmbidexterity:How ProjectsDynamicallyCon igureCapabilitiesfor AgriculturalInnovation,” LandUsePolicy,vol.68, 2017,pp.503‐523.

[57] M.G.Velazquez‐Cazaresetal.,“InnovationCapa‐bilitiesMeasurementusingFuzzyMethodolo‐gies:AColombianSMEsCase,” Computational andMathematicalOrganizationTheory,vol.27, 2021,pp.384‐413.

A2‐TUPLELINGUISTICDYNAMICOWAWAAGGREGATIONOPERATORANDITS

A2‐TUPLELINGUISTICDYNAMICOWAWAAGGREGATIONOPERATORANDITS A2‐TUPLELINGUISTICDYNAMICOWAWAAGGREGATIONOPERATORANDITS

Submitted:14th April2024;accepted:17th September2024

YelenyZulueta‑Véliz,CarlosRafaelRodríguezRodríguez,AylinEstradaVelazco DOI:10.14313/jamris‐2025‐032

Abstract:

Alinguisticdynamicdecision‐makingproblemreveals situationsinwhichthedecisiondatagatheredinmulti‐pleperiodsisrepresentedbymeansoflinguisticvalues. Todealwithlinguisticvariablesinlinguisticdynamic decision‐makingproblems,the2‐tuplelinguisticmodel standsoutamongcomputationalmodelsbecauseofits accuracyandinterpretability.Theselectionofasuitable time‐dependent2‐tuplelinguisticaggregationoperator isrelevantduetoitspropertiesthatcanhighlymodifythe computingcostaswellastheresultsthemselvesandtheir accuracyandinterpretability.Thispaperproposesanew 2‐tuplelinguisticdynamichybridweightedaggregation operatorwhichissuitabletomodeldifferentattitudesin decision‐makingbysimultaneouslyweightingthegiven argumentsaswellastheirorderedpositions.Thenovel 2‐tupleLinguisticDynamicOrderedWeightedAveraging‐WeightedAverage(2TDOWAWA)operatorweightsnot onlytheimportanceofaparticulartimeperiod,butalso theimportanceofnon‐dynamicevaluationsinsucha timeperiod.Eventually,a2‐tupleLinguisticDynamicMul‐tipleAttributeDecision‐Makingapproachbasedonthe 2TDOWAWAAggregationOperatorisdescribed.Finallya practicalexampleisprovidedtoillustratethedeveloped approachandtodemonstrateitspracticalityandeffec‐tiveness.

Keywords: linguisticdecision‐making,dynamicdecision‐making,2‐tuplelinguisticmodel,aggregationoperator

Granulationplaysakeyroleinhumancognition. Forhumans,itservesasawayofachievingdatacom‐pression.Thisisoneofthepivotaladvantagesaccru‐ingthroughtheuseofwordsinhuman,machine,and man‐machinecommunication[1].Zadehemphasized twokeynotes[2]:theconceptofgranulationisunique tofuzzylogic[3]andcloselyrelatedtotheconceptof aroughset[4].Granulationinvolvespartitioningaset intogranulesandagranulemaybeinterpretedasa restrictiononthevaluesthatavariablecantakes.In thissense,wordsinanaturallanguageare,inlarge measure,labelsofgranules.

Sincealinguisticvariableisavariablewhoseval‐uesarewordsor,equivalently,granules,theconcept ofgranulationisrootedintheconceptoflinguistic variables[5].

Ingeneralsense,by”informationgranule”,one regardsacollectionofelementsdrawntogetherby theircloseness(resemblance,proximityorfunctional‐ity)articulatedintermsofsomeusefulspatial,tempo‐ralorfunctionalrelationships.Whenwedecompose anuncertaindecision‐makingproblemintogranules, temporalrelationshipsareveryimportanttofocuson themostsuitablelevelofdetail.

Asdecisionenvironmentsandcontentsbecome increasinglycomplex,theuseofsingle‐granule informationalonefailstoaccuratelydescribe dynamic,ambiguousandfragmentarycognitive information.Dynamicmulti‐attributedecision‐makingframeworksoffertodecision‐makersaway ofdealingwithuncertainty,sincethiskindofsolution enablesforaniterativeandinteractiveprocessin whichthedecisioninformationisusuallycollected fromdifferentperiod[6–9].Thatis,thedynamic decision‐makingproblemconsistsofselectingthe bestalternativesfromasetofavailableonesbut consideringtimegranulation[10].Dynamicmulti‐attributedecision‐makingapproachesareimplicitly granule‐basedbecausetheygenerallymodela dynamicproblemasacollectionofstaticdecision‐makingproblemsthataresolved irstandthentheir resultsareaggregatedusingadynamicweighted aggregationoperatoranditsweightingvector.

Theconceptofthelinguisticdynamicmulti‐attributedecision‐making(LDMADM)problem revealssituationsinwhichdecisiondatagatheredin multipleperiods,whichisrepresentedbylinguistic termsbymeansoflinguisticvariables.

Withagranulebeingacollectionofelements whicharedrawntogetherbyequivalence,proximity, similarityorfunctionality,intheLDMADMprocess, uncertaintyismanagedinthesetwogranule‐based dimensions:(a)linguisticvariablesand(b)timeperi‐ods.Let’sgetintothetwofoldcomplexityinbrief.

Todealwith(a)linguisticvariablesinLDMADM, the2‐tuplelinguisticrepresentationmodel[11]pro‐videsapowerfulapproachbecauseitcanexpressany countingofinformationinthediscourseuniverse; meanwhile,itimprovestheinterpretabilityandeffec‐tivenessofthedecision‐makingresultsbyavoiding losinginformationincomputations.Studiesof2‐tuple linguisticrepresentationmodelnotonlyhaveastrong theoreticalresearchvalue,butalsohavewideappli‐cationprospectsinpractice,speci icallyindecision‐makinganddecisionanalysis.

Todealwith(b)timeperiodsinLDMADM,theres‐olutionprocesshasbeenstructuredin[12].Theselec‐tionofasuitabletime‐dependentlinguisticaggrega‐tionoperator,anditsweightingvectorifnecessary,is akeyelementduetothepropertiesthatcanhighly modifythecomputingcostaswellasresultsthem‐selvesandtheiraccuracyandinterpretability.The aggregationisamulti‐stepprocess: irst,acollective assessmentiscalculatedforeachalternativeforeach period,i.e.,eachstaticproblemissolved;second,a dynamiccollectiveassessmentforeachalternativeis calculatedusingvaluesobtainedpreviously,i.e.,the generaldynamicproblemissolvedandanoverall resultisobtained.

Thisdynamicaggregationisgenerallycarriedout usingtime‐dependentaggregationoperatorsconsid‐eringthediversein luenceoftimeperiodsinresults bymeansofweightingvectors.Basedontheabove reviews,wefacetheneedofproper2‐tuplelinguis‐ticaggregationoperatorsforsuchatime‐dependent aggregationprocess.

Whatkindof2‐tuplelinguistictime‐dependent aggregationoperatorsareavailableintheliterature? Asfarasweknows,the2‐tuplelinguisticDynamic WeightedAveraging(2TDWA)[14],the2‐tuplelin‐guisticDynamicAveraging(2TDA)[14],the2‐tuple linguisticDynamicWeightedGeometric(2TDWG)[15] andthe2‐tuplelinguisticDynamicGeometric(2TDG) [15]aggregationoperatorsonlyweightthe2‐tuple linguisticargumentsthemselves.Thatis,theyweight eachtimeperiodinrelationtotheirreliabilitybut theycannotsyntheticallyconsidertheimportance oftimeperiodsandtheimportanceofnon‐dynamic evaluations.

Whatkindofhybridweightedaggregationoper‐atorsareavailableintheliterature?Numericaggre‐gationoperatorshavebeenstudiedforalongtime. Amongthelargenumberofaggregationoperatorsand functions,thearithmeticmean(AM)andtheweighted mean(WM)arethemostpopularones.Arelatedoper‐ator,theorderedweightedaveraging(OWA)operator, wasproposedbyYagerin[16].Thisoperatorissimilar totheWMasbotharealinearcombinationoftheinput data.ThedifferencebetweentheWMandtheOWA operatoristhatthelatterordersthedatabeforeapply‐ingthelinearcombination[17].Thisorderingstep causesthesemantics(ormeaning)oftheweightstobe radicallydifferentintheweightedmeanandtheOWA. Infact,theweightsintheweightedmeanmeasurethe reliabilityofthesourcesandtheweightsintheOWA measuretheimportanceofthevalues(withrespectto theirordering).Theneedofcombiningbothfunctions hasbeendevelopedbydifferentauthors[18,19]and threemainclassesoffunctionshavebeenproposed forgeneralizingthem:theweightedOWA(WOWA) operator[18],thehybridweightedaveraging(HWA) operator[19],andtheorderedweightedaveraging‐weightedaverage(OWAWA)operator[20].Themain advantageofthelastapproachisthatituni iesthe OWAandtheWA,takingintoaccountthedegreeof importancethateachconcepthasintheformulation.

Motivatedbythisgap,inthispaper,wepropose anew2‐tuplelinguisticdynamichybridweighted aggregationoperatorwhichisusefultomodeldif‐ferentattitudesindecision‐makingbysimultane‐ouslyweightingthegivenargumentsaswellastheir orderedpositions.

Theremainderofthispaperisstructuredasfol‐lows.Section2reviewsbasicconceptsofthe2‐tuple linguisticrepresentationmodel.Section3introduces anew2‐tuplelinguisticOWAWAaggregationoperator whichisintegratedinthe2‐tupleLDMADMapproach describedinSection 4.Section 5 givesanillustrative example,andSection 6 summarizesthekey indings ofthisresearch.

2.Preliminaries

Thissectionrevisesconceptsandmethodstobe referredtointhispaper,includingthe2‐tuplelinguis‐ticrepresentationmodelanditscomputationalmodel.

2.1.2‐tupleLinguisticRepresentationModel

In[11],HerreraandMartínezprogressedthefuzzy linguisticdecision‐making ieldbyrepresentingthe linguisticinformationwiththename2‐tuple,con‐structedbyalinguistictermandanumericalvalue, supportingtheinformationofthesymbolictransla‐tion.

The2‐tuplelinguisticmodel[11]aimedtoimprove theaccuracyandfacilitatetheprocessesofcomputing withwordsbytreatingthelinguisticdomainascon‐tinuousbutkeepingthelinguisticbasis(syntaxand semantics).The2‐tuplefuzzylinguisticrepresenta‐tionmodelconsistsofmodellingthelinguisticinfor‐mationbymeansofapairofelements[21]:

‐ Let ��={��0,...,����} bealinguistictermde inedby thefuzzylinguisticapproachwhosesemantics(pro‐videdbyafuzzymembershipfunction)andsyntax arealsode inedaccordingtothefuzzylinguistic approach.

‐ �� isanumericalvalue, SymbolicTranslation,that indicatesthetranslationofthefuzzymembership functionwhichrepresentstheclosestterm, ���� ∈ {��0,...,����}if���� doesnotmatchexactlythecomputed linguisticinformation.Thevalueof��isthende ined as

[−0.5,0.5)�������� ∈{��1,��2,...,����−1} [0,0.5)�������� =��0 [−0.5,0)�������� =���� (1)

Thelinguisticinformationisthenexpressedbya pairofelementsnotedas (����,��).Asymboliccompu‐tationonlinguistictermsin �� obtainsavalue ��∈ [0,��] thatwillbetransformedintoaequivalent2‐tuplelinguisticvalue,(����,��),bymeansoftheΔfunc‐tionde inedasfollows:

De inition1 [21]Let ��={��0,...,����} thesetoflinguisticterms,theassociated2-tupleis ��=��×[−0.5,0.5) andthebijectivefunction Δ∶[0,��]→�� isgivenby:

����, ��=����������(��) ��=��−��,��∈[−0.5,0.5) (2)

with ���������� assignsto �� theintegernumber ��∈ {0,1,...,��} closestto ��

The Δ and Δ−1 transformationfunctionssupport conversionsbetweennumericalvaluesand2‐tuple linguisticvalueswithoutinformationloss.The2‐tuple linguisticmodelonlyguaranteesaccuracywhendeal‐ingwithauniformlyandsymmetricallydistributed linguistictermset.

Therecenttwodecadeshavewitnessedtheboom‐inginterestandgrowingdevelopmentinresearchof 2‐tuplelinguistictime‐independentaggregationoper‐ators.FunctionsΔandΔ−1 greatlyhelptheextension ofconventionalnumericaloperatorstothe2‐tuplelin‐guisticdomain.Inwhatfollows,twoseminal2‐tuple linguistictimeindependentaggregationoperatorsare revised.

De inition2 [11]Let ��={(��1,��1),...,(����,����)} bea setof2-tuplelinguisticvalues,and ��=(��1,...,����), ���� ∈[0,1] beaweightingvectorsuchthat ∑�� ��=1 ���� =1, theweightedaveragingaggregationoperatorassociatedwith �� isthefunction2TWA: ���� →�� de inedas:

(��)=Δ �� ��=1

) (3)

Especially,if ��={ 1 �� , 1 �� ,..., 1 ��},the2TWAoperator reducestothe2-tuplearithmeticmean(2TAM)operator:

2TAM(��)=Δ 1 �� �� ��=1 Δ−1(��

) (4)

2.2.Discretetime2‐tuplelinguisticvariable

Thesigni icantcharacteristicofthe2‐tuplelin‐guisticvariableisthatitinvolvesthedimensionof time,andthisconceptispivotalinunderstanding2‐tupleLDMADMproblems.

De inition3 [10]Let �� bethevariableoftime,then ��(��) iscalledadiscretetime2-tuplelinguisticvariable where ��(��)=((��1,��1)(��1),...,(����,����)(����)) isacollectionof �� 2-tupleargumentscollectedfrom �� different periods, ��={��1,...,����}.

Operationlawsandpropertiesontheconven‐tional2‐tuplelinguisticvaluealsoholdforthediscrete time2‐tuplelinguisticvariablebecauseifomittingthe parameterofthetime(����),thelatercanbemathemat‐icallytakenastheformer.

Theconceptofdiscretetime2‐tuplelinguistic variableaddressestherepresentationofchangesof experts’assessmentsongivenalternativesoveran attributebutconsidersdifferenttimeperiodsinthe LDMADMprocess.

2.3.2‐tupleDynamicWeightedAggregationOperators

The2‐tuplelinguisticaggregationoperatorsare logicallyrequiredtodevelopthedynamicaggregation phaseintheLDMADMresolutionprocess.Let’sana‐lyzesomeoftheexistingaggregationoperators.

De inition4 [14]Let �� = {(��1,��1)(��1),...,(����,����)(����)} beacollectionof �� 2-tupleargumentscollectedfrom �� different periods, ��={(����)|��∈(1,...,��)},whoseweightsare givenbytheweightingvector ��,thenthefunction 2TDWA ∶���� ⟶�� de inedas

2TDWA(��)=Δ �� ��=1 ��(����)Δ

(5)

iscalleda2-tupleDynamicWeightedAveragingaggregationoperator.

Especially,if ���� ={1 �� , 1 �� ,..., 1 ��},the2TDWAoperatorreducestothe2-tupleDynamicAveraging(2TDA) aggregationoperator:

2TDA(��)=Δ 1 �� �� ��=1 Δ−1(����,����)(��

(6)

De inition5 [22]Let �� = {(��1,��1)(��1),...,(����,����)(����)} beacollectionof �� 2-tupleargumentscollectedfrom �� differentperiods, ��={(����)|��∈(1,...,��)} andaweightingvector ��,then thefunction2TDOWA ∶���� ⟶�� de inedas

2TDOWA(��)=Δ

iscalleda2-tupleDynamicOrderedWeightedAveragingaggregationoperator,where (����,����)(����) isthe ��-th largestofthe (����,����)(����) values.

Ontheonehand,inthe2TDWAthe i‐th2‐tuple linguisticvalueisweightedaccordingtotheweight ��(����).Ontheotherhand,in2TDOWAeach ��(����) is attachedtothe i‐thvalueindecreasingorderwithout consideringfromwhichinformationsourcethevalue comes.NoticethattheOWAoperatoriscommutative. Thatis,allinformationsources(orexperts)havean equalcontributiontothe inalsolution.

Thebehaviorofweightedaveragingoperators allowsustoweighteachinformationsourceinrela‐tiontotheirreliabilitywhileorderedweightedoper‐atorsallowtoweightthevaluesaccordingtotheir ordering.

The2TDWA[14,15]operatoronlyweightsthe2‐tupleargumentsthemselves,butignorestheimpor‐tanceoftheorderedpositionofthearguments,while the2TDOWA[22]operatoronlyweightstheordered positionofeachgivenarguments,butignoresthe importanceofthearguments.Tosolvethisdraw‐back,anew2‐tupleaggregationoperatorswillbe de inedfortimedependent2‐tuplelinguisticargu‐ments,whichweightallthegivenargumentsandtheir orderedpositionsbasedonOWAWAoperator[20].

Intherestofthepaper,wewillrecallorintro‐ducede initionsofweightedaggregationoperators. Itisworthnotingthatthesefunctionsarede ined bymeansofvectorswithnon‐negativecomponents whosesumis1.

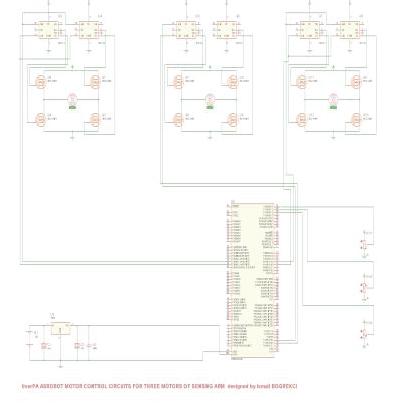

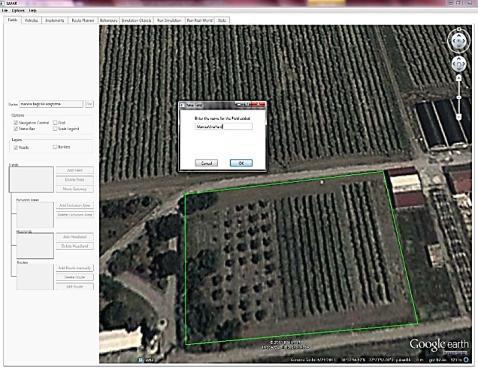

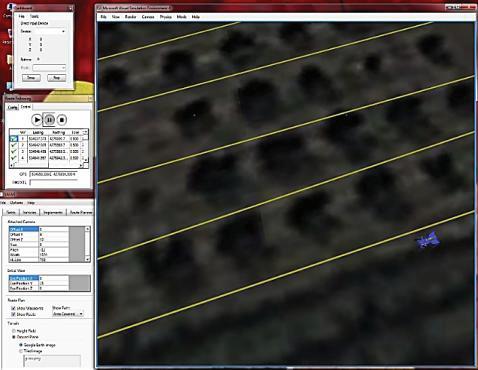

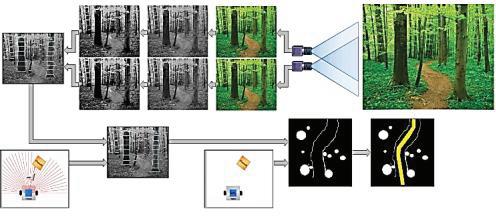

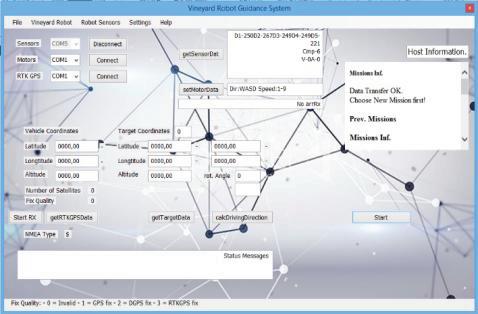

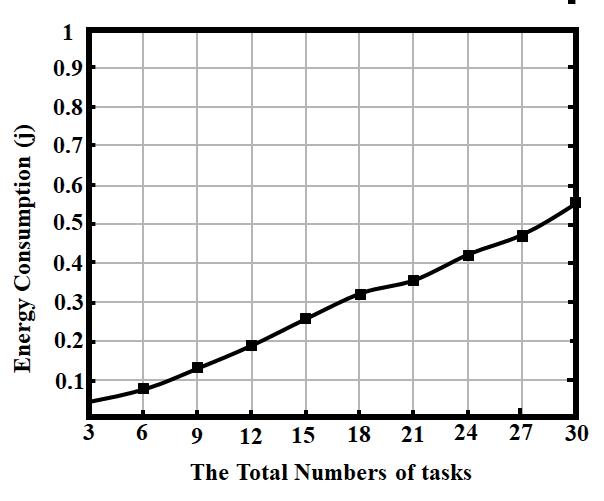

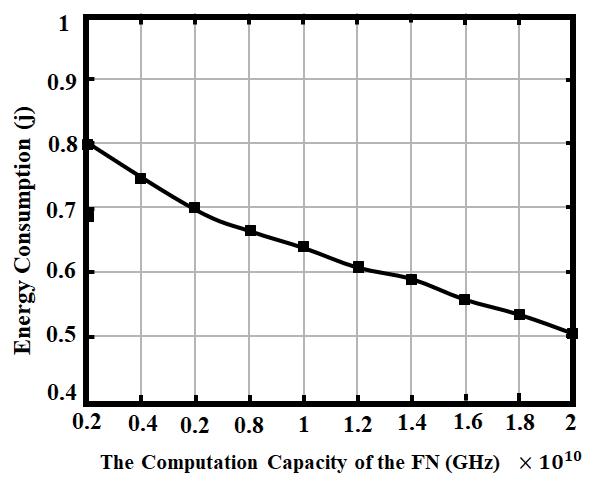

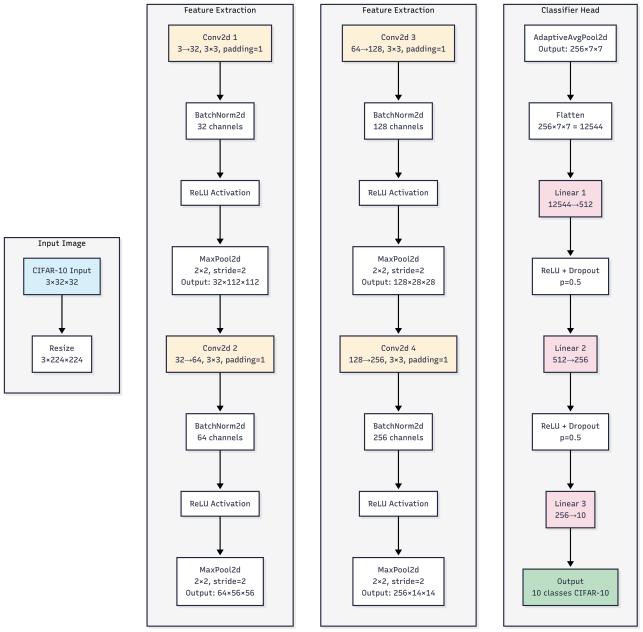

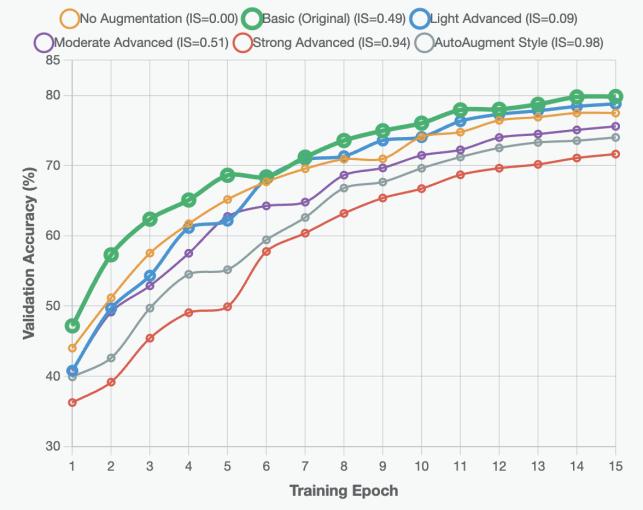

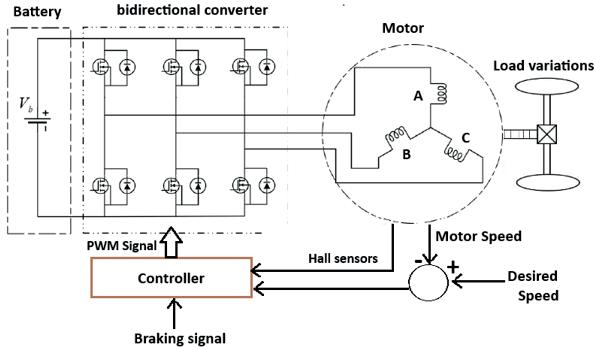

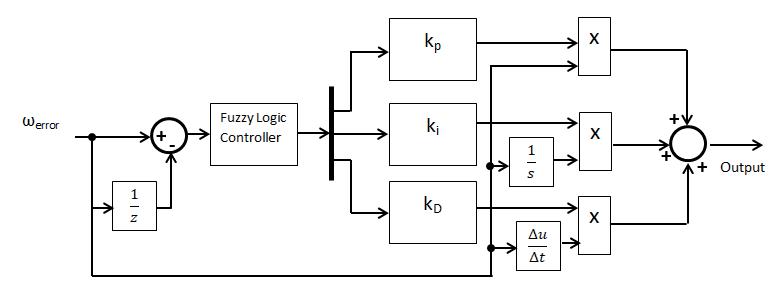

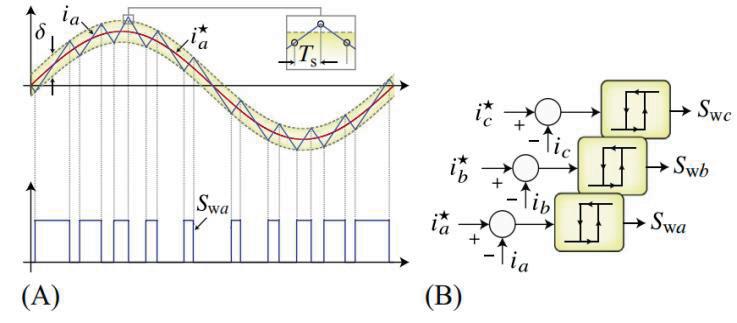

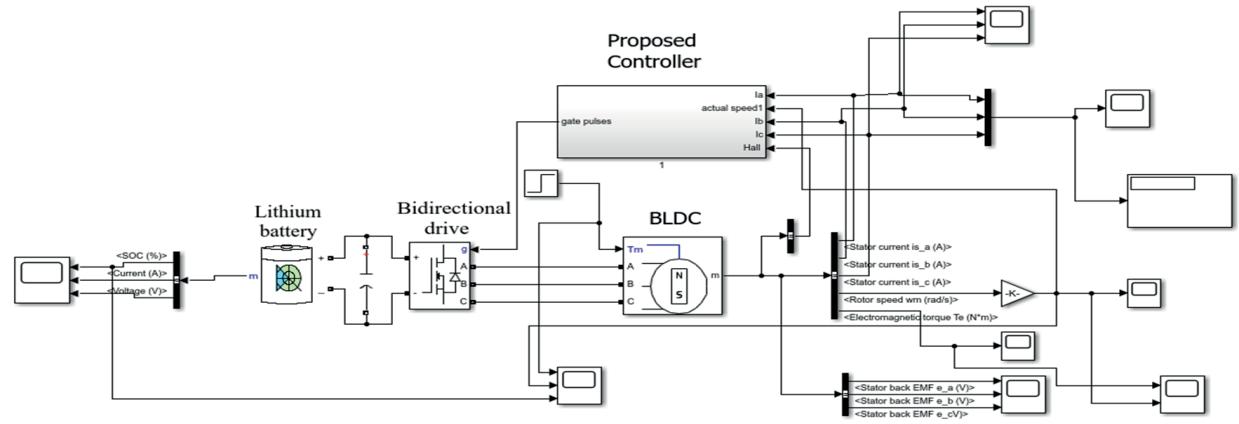

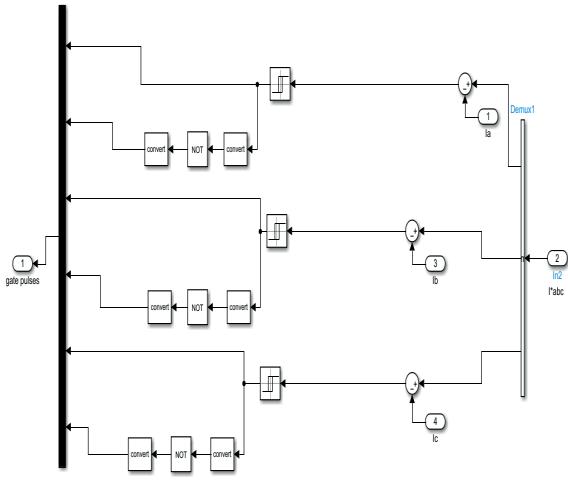

De inition6 Avector ��∈ R�� isaweightingvectorif ��∈[0,1]�� and ∑�� ��=1 ���� =1