PITTSBURGH’S ALTERNATIVE FOR NEWS, ARTS + ENTERTAINMENT SINCE 1991

PITTSBURGH’S ALTERNATIVE FOR NEWS, ARTS + ENTERTAINMENT SINCE 1991

By: Rachel Wilkinson

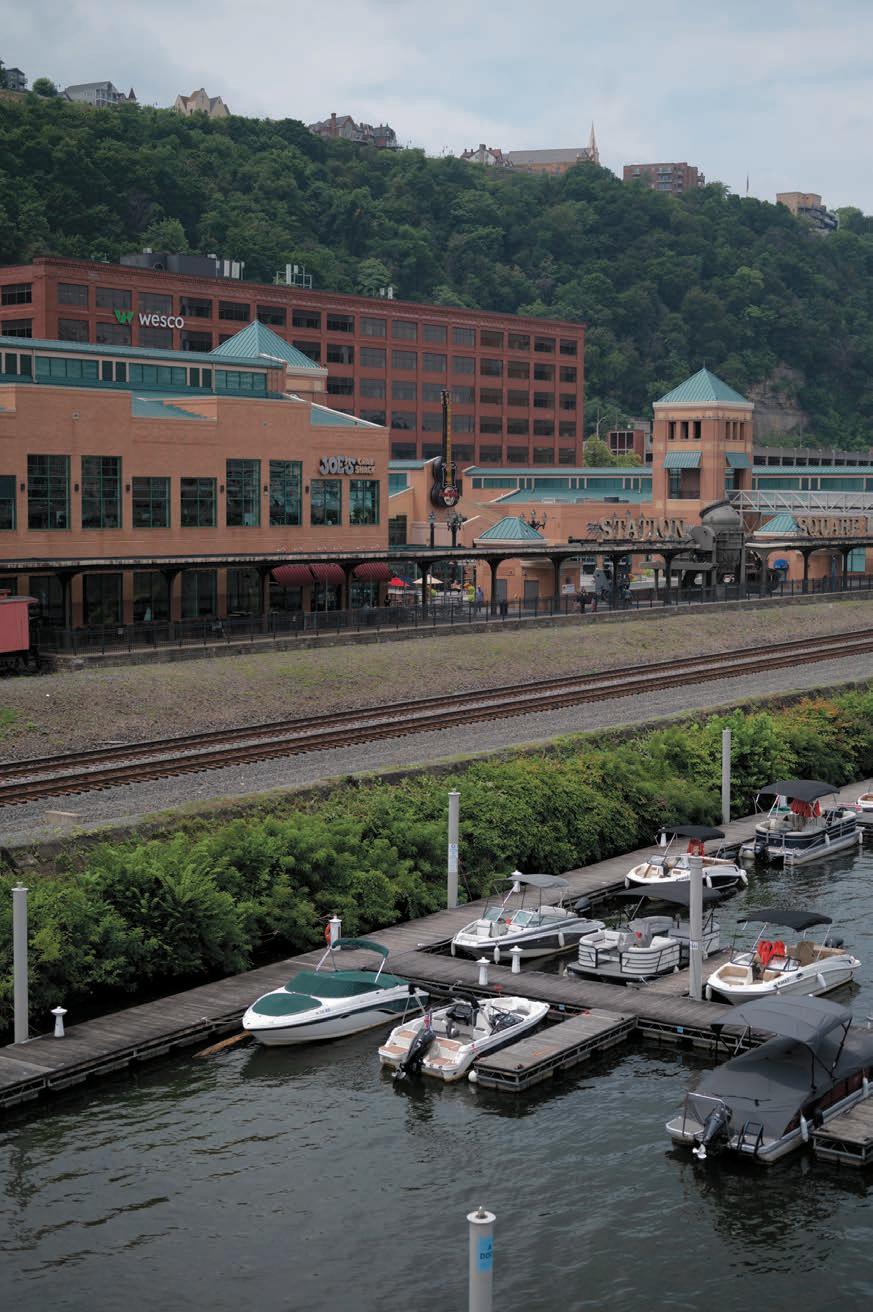

Station Square is due for a turnover. Will it happen in time?

Product/features not available in all states. Contact us for complete details about this insurance solicitation. To find a network provider, go to physiciansmutual.com/find-dentist. This specific offer not available in CO, NV, NY, VA – call 1-800969-4781 or respond for a similar offer in your state. Certificate C254/B465, C250A/B438 (ID: C254ID; PA: C254PA); Insurance Policy P154/B469, P150/B439 (GA: P154GA; OK: P154OK; TN: P154TN). 6347

This role requires a sales and marketing-minded individual who desires an exciting opportunity to earn uncapped commissions and focus on connecting the local Pittsburgh business owners and organizations with marketing strategies including print, digital, events, sponsorships and social media advertising. This person desires to work with a supportive team base and the passion to build the brand within the community. This position includes a current client base to manage, foster and grow while also focusing on acquisition of new clients to hit monthly goals set forth by the company.

This position needs an individual with in-depth knowledge and understanding of the local market and understands the competitive landscapes that many SMBs face today. The ideal candidate is motivated and focused on revenue growth across all platforms with the intention of meeting and exceeding revenue goals.

Pittsburgh’s historic riverside entertainment complex is due for a turnover. Will it happen in time?

BY: RACHEL WILKINSON // RWILKINSON@PGHCITYPAPER.COM

Ask around town and the future of Station Square is, at best, in flux. In the past eight months, three of the riverfront complex’s mainstay restaurants have shut down after operating since the turn of the century. Buca di Beppo closed in June after 25 years, shuttering the Italian chain’s last location in the region. Joe’s Crab Shack followed in September, abruptly closing with no official announcement. And Hard Rock Cafe Pittsburgh, which, for decades, hosted live music ranging from tribute bands to local acts, closed on Feb. 13 after 23 years. The restaurant’s closure came after Brookfield Properties, the New York-based firm that owns Station Square, reportedly decided not to renew its lease. To compound the uncertainty, Brookfield Properties also faces a foreclosure lawsuit, filed in November, demanding more than $140 million in unpaid loans. One news report described the situation as “dismal.” District 2 City Councilor Theresa Kail-Smith, who represents the area that includes Station Square, called the possible foreclosure “a terrible blow to Pittsburgh.”

Hard Rock Cafe kitchen manager Matt Byrne, a 15-year veteran who recently created the restaurant’s award-winning Pittsburgh Burger, says management “did this to themselves for whatever is going to happen down here.”

Pittsburgh City Paper visited Hard Rock in August, where Byrne and the staff, several of whom had been working at the Station Square restaurant since it opened in 2002, were relieved to have weathered pandemic shutdowns.

Byrne describes his reaction to its permanent closure as “not bitter, just disappointed in how this area was mismanaged.” But it’s not all doom and gloom. He says Hard Rock staff in the restaurant’s final days remained “all very grateful for the time spent here and the friends and family we made while having the privilege of working in the area and at the cafe. So that’s the silver lining for us.”

Station Square has long held a special place for Pittsburghers. Ensconced in historic buildings, the soon-to-be 50-year-old complex has consistently billed itself as a “premier dining and entertainment destination,” with scenic views of the Monongahela River and Incline. Once a social hotspot, Station Square has been the site of weddings, birthdays, proms, and vibrant nightlife with warehousestyle clubs, as well as serving as a potent symbol for Pittsburgh’s postindustrial renaissance.

Poised again for transition, Station Square rekindles the questions of what redevelopment in Pittsburgh can be, especially as Downtown, just across the Smithfield Street Bridge, undergoes its own revitalization.

Karamagi Rujumba, director of education, development, and advocacy at the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, explains that the Station Square we know today began with the death of the passenger rail. The Pittsburgh and

Lake Erie Railroad was anchored by a grand seven-story station — whose “P&LE RR” sign can still be spotted from Downtown — at the base of the Smithfield Street Bridge. Though the railroad was once known as the “Little Giant” for moving heavy tonnage of steel, coal, and iron ore, by the 1970s, it had declined and operated only one commuter line.

The Landmarks Foundation, founded in the 1960s, saw the area could be slated for demolition, as the city had already done in Pittsburgh’s Hill District.

“Our organization was really formed in antipathy of what urban renewal was,” Rujumba tells City Paper, noting that swaths of the North Side and South Side had also been marked for demolition. “Our idea was that you don’t have to demolish neighborhoods to reinvest in them, that you can actually use the historic buildings and historic neighborhoods to create vitality by restoring them.”

PHLF acquired the 52-acre riverfront site in 1975, establishing the Landmarks Building at the railroad’s headquarters.

Rujumba emphasizes their goal was not only to “turn around what was a railroad into commercial, retail, and office space,” but to integrate “artifacts from Pittsburgh’s industrial past.” Station Square’s Bessemer Court was designed to link the site’s riverwalk to its heritage, incorporating a 10-ton Bessemer converter built in 1930.

In 1978, PHLF facilitated the creation of the Grand Concourse Restaurant, a significant addition to Pittsburgh’s fine dining scene. The restaurant also modeled historic preservation, repurposing the former train station’s Victorian and Edwardian architecture, marble columns, and stained-glass cathedral ceilings.

After 19 years and having achieved its goals, PHLF sold Station Square to developer Forest City Enterprises

in 1994. At the peak of Landmarks’ ownership, Rujumba says, Station Square operated 150 businesses, created 3,000 jobs, and generated more than $4 million in tax revenue.

“We like to say it’s the shining example of what real urban renewal can be,” he tells City Paper

One challenge Station Square faces today, says Chris Briem, a regional economist at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Social and Urban Research, is that it might be a victim of its own success.

“There was an era where it probably didn’t have that much competition,” Briem reflects.

When Station Square was created, “you probably could have stood [and] looked up the river and seen the J&L [steel] plant. There was an orange glow on the river. Things were pretty bad. Here was something new,” Briem says.

While bars dotted the South Side in the 1970s, the neighborhood catered to workers, and wasn’t yet a nightlife destination. The Strip District, then home to a tri-state produce terminal, had fallen into disrepair after Penn Central Railroad filed for bankruptcy in 1970, and had yet to undergo its own transformation.

“When the ‘80s came, there’s all this great effort to move beyond steel,” Briem tells CP. “We didn’t really do very well, or at least not quickly. So Station Square was kind of an exception to that, a place that people wanted to be.”

Briem cites another wave of urban development that emphasized redeveloping Pittsburgh’s rivers (culminating, in part, with a visit by then Prince Charles to the first Remaking Cities Conference in 1988).

“You go back 40 or 50 years, we were not using any of these riverfronts,” Briem says.

Given all this, Station Square “justified proof of concept” to build out other riverfront retail and

entertainment destinations (or so-called “lifestyle centers”) like Southside Works or the North Shore, which now draw its customers.

As an urban or pedestrian mall, Station Square also battled with other shopping complexes like the now-defunct Allegheny Center Mall, Briem says. Though Station Square survived while most malls (urban and suburban) did not, it’s been subject to the same retail apocalypse, hastened by the pandemic.

Briem also views Station Square’s trajectory as tied to larger shifts in Downtown Pittsburgh, which is still grappling with the rise of remote work and repurposing office space for residential conversion.

“No one really planned on COVID happening or this shift happening so fast. And change can be absorbed if it happens slowly enough,” Briem says. “But I think as leases turn over Downtown, you’ll see more and more vacancy and more and more property

devaluations, which will beget more and more turnover.”

Practically speaking, “it’s not actually that easy to get to,” Briem says of going to Station Square from Downtown. “It’s an old joke, because Pittsburghers don’t cross bridges … For Americans, it’s a complex path.”

If you want to hear from an optimist, Thomas Jayson can easily reel off a detailed plan for Station Square’s future. The former club magnate and owner of storied venues including Chauncy’s, Matrix, and Rock Jungle (to name a few) still runs a sports bar in Station Square, Homerun Harry’s.

“I see it. I’ve been here. I lived it,” Jayson tells CP . “Been here from day one.”

In Jayson’s view, it’s misguided to try to attract foot traffic from Downtown or entice guests to cross a bridge. Though the Smithfield Street Bridge is well-traveled by pedestrians, Station Square should still be thought of as its own destination.

“Because it’s a great location, it’s a safe location,” Jayson says. “You’ve got two inclines that attract a lot of tourism. You’ve got the Gateway [Clipper] fleet down here, which brings in a lot of people. You’ve got [Highmark] stadium; you’ve got everything.”

Jayson asserts that the recent restaurant closures weren’t due to a lack of business, but broader issues with the chains’ business models, such that successful locations “went down with the ship.” Even so, as he previously cautioned, novelty is a tricky thing, and he considers Hard Rock’s concept outdated.

Conversely, Station Square’s existing restaurants, the Grand Concourse (whose developer Jayson knew), the Melting Pot, and Texas de Brazil are “all doing fantastic,” Jayson says. “That proves it’s a good location.”

The biggest challenge currently is “nothing’s going to happen until a new owner’s in place,” Jayson says, which he believes will be resolved

in a matter of months. (The prediction may prove true as Boston-based firm S Development was reportedly working to buy Station Square last month.

After the complex changes hands, Jayson says, it needs new tenants, and “the e ort should be to bring in more restaurants and some entertainment.”

The Freight House, once home to the original Funny Bone comedy club and 50 shops, sits empty, save for a vacant medical training center subleased by P C. Commerce Corner, where Chauncy’s was, also has occupancy problems. Jayson believes it’s still “a great space” that, with upgrades, could attract a national restaurant chain. A new owner could also extend Station Square’s sidewalk to the Sheraton Pittsburgh Hotel which is owned separately and attract more guests.

Jayson says he’s working on “three or four or five concepts”

that could slot in next door to his bar, including a lounge with live entertainment.

“They need some cocktail lounges,” he emphasi es. “Not nightclubs like the old days those days are gone. But I’d open up a restaurant lounge, a cool place to hang out-type place.”

Contrary to Station Square’s rumored decline, both Ru umba and Jayson believe there’s room for it to grow, even to build more residential space in addition to the lasshouse Apartments, developed in 201 . Jayson can envision a hotel near the incline with a “magnificent view.”

“A very upscale, five-star boutique hotel would do spectacular there,” he says.

“So I think it’s going to come back. There’s no doubt in my mind, it’s not going anywhere,” Jayson says. “I think there is definitely a future here at Station Square, and I think that’ll soon be reali ed.” •

A quest for truth leads one writer down the rabbithole of history as written by the victors

BY: DANI LAMORTE

In the Leechburg I knew, a 100-foot serpent, translucent and full of rage, surfed the Kiskiminetas River. According to a woman at my church, located 40 miles northeast of Pittsburgh, the beast was a “leviathan” — a Biblical-era demonic Nessie. I was 8 or 9 years old, learning to see into a realm that my church said was populated by angels and demons.

The other people in town didn’t see what we saw. To them, eechburg wasn’t filled with invisible spiritual beings, but had ghosts of another sort floundering mills, empty storefronts, and incomplete legends. The town’s history is filled with the names of people who own or owned property. Some of the owners are well-known and others are almost anonymous, leaving lots of space to speculate. A legendary town founder might be as real as a leviathan.

While drafting essays for my book on identity and self discovery, Nobody’s Psychic , I revisited the religious “vision training” I underwent in the 1990s and wondered about its relationship to my life today. As a writer, I’m expected to ground my memories in general historical context, but all I knew about Leechburg was spectral. Lacking information, but possessing a library science degree, I began researching Leechburg’s history in expert fashion: I went to Google and typed “Leechburg history” into the search bar. What returned to me was what I vaguely knew: In 1850, David Leech humbly renamed the town after himself. There were salt mines, railroads, canals, and mills. Bridges, then floods.

What is less known, maybe less knowable, is what happened before Leech made himself a burg. In a book commemorating Leechburg’s 150th anniversary, Joseph Kantor imagines the area before European settlement as “pristine,” with “sunlight glittering on the Kiski [River], lush forest overhanging the swift current. Game was likely plentiful and the flooding of the river

made the soil rich.” He admits, though, this is all fantasy.

Even in 1822, only eight white families lived in the area. The area wasn’t far from an Indigenous town of unknown Tribal affiliation, but — by all accounts — no native groups took up the site of Leechburg as a permanent dwelling. One could make the case that native people were using the land even if they didn’t live on it. Foraging grounds, fishing shores, and hunting woods all come to mind. But do you have to use something to make it yours? Nobody needed to work the land for the land to be working on somebody.

Empty like the address bar of a web browser, waiting for its cue.

More typing and clicking led me to John Walker, who surveyed the area in 1773. The following year, he sold a portion of the land to Joshua Elder. Nearly 10 years later, Elder reportedly sold that portion to Delaware Indian Chief White Mattock for five pounds, 10 shillings.

“Delaware” comes from an honorific title given to colonial Virginia governor Sir Thomas West, known as Lord de la Warr

“THE IMPROVED ORDER OF RED MEN ‘PAINTED ITSELF AS A GATHERING OF HISTORIANS, THE WORTHY KEEPERS OF THE NATION’S ABORIGINAL ROOTS.’”

III. When Captain Samuel Argall explored present-day Delaware, he passed the name along in honor of West. Encroachment by and violence from European settlers forced

And we want to imagine it, don’t we? We, who look like the King’s traitorous subjects, want to imagine the land as “pristine,” “lush.” We borrow this desire from the men who arrived on ships and said “It’s empty” into the eyes of living people. This desire is where the real emptiness is.

many Unami- and Munsee-speaking Lenape peoples — called “Delaware” by white settlers — towards the western frontier, the area of Fort Pitt and Ohio. Some headed north into New York and Ontario.

William Riley Trout, a Leechburg area resident born in 1829, was the first person to report Delaware Chief White Mattock’s land purchase. His knowledge was passed along in a 1916 book of local history by T.J. Henry. Henry writes that Trout, “a local historian of note, was of the opinion [that White Mattock] had taken out patents for land after the manner of the white man. White Mattock had taken up the site of Leechburg.”

Henry and Trout refer readers to an 1883 text by Robert Walter Smith, which is said to confirm this story. But Smith’s book contains no reference to a Delaware Chief named White Mattock, just a presumably European man named White Matlock. The three history buffs were wrong on several accounts. Their errors open up as doors to another time, to an adjacent America.

In the late 1700s, a group of European settlers formed an organization for

hyper-patriotic, very American Americans. With no irony in their colonial hearts, they named themselves “The Sons of King Tammany,” later “The Sons of St. Tammany,” after Tamanend—a Lenape leader known to white settlers as “Tammany.”

Historian Phillip J. Deloria argues that the selection of a Native American mascot like Tamanend wasn’t random. White Americans have repeatedly donned Native American costume — literally or ideologically — for political projects. For instance, during the Whiskey Rebellion (1791-1794) a group of white anti-taxation rebels penned a pseudo-declaration under fictitious Native pen names and published it in the Pittsburg Gazette as a message from the “Six United Nations of White Indians.”

Tamanend emblematized the “wild” spirit that white settlers hoped would keep government interference in check. They wanted an icon who was a potential menace to “the powers that be,” made from corpuscles of unalienable aboriginal sovereignty. Tamanend, the man, may or may not have seen himself as any of those things.

As the Tammanies grew, the Lenape people themselves were pushed further west and north by people who sought to copy them to death. These copyists would dress in “native” garb, smear their faces with paint, and pass a ritual pipe as a sign of brotherliness.

A 1798 New York City directory lists the local Tammany chapter’s “sachems” — a term for a traditional Lenape leader (the NYC chapter would later become a byword for the city’s machine politics). Among them was a 53-year-old watchmaker, silversmith, brewer, and steel manufacturer. In 1783, he purchased 192 acres of land along the Kiskiminetas River, right where Leechburg would one day be. His name is inscribed in the land patent books, in that heavilyslanted, thin-lined 1700s script we know from Declarations of things: White Matlack. In a bit of flourish, the scribe crossed not only his T’s but his L’s, too. The second “a” was left ambiguous. To a quick eye, “Matlack” looks like “Matlock,” maybe even “Mattock.” Property deeds in Leechburg often copied this misread, showing White Mattock as a once-upon-a-time owner.

Getting what you want has a way of not lasting. Less than a century after the United States declared its independence, settlers began to worry that the true American way of life was being forgotten. Focused on history, patriotism, and charitable causes, the Improved Order of Red Men “painted itself as a gathering of historians, the worthy keepers of the nation’s aboriginal roots,” according to Deloria. Like the Tammanies, they dressed in costume. Unlike the Tammanies, they didn’t think of Native people as a symbol of political power, but as touchstones for a good, old, natural, all-American, meateating, firework-firing past that never was. ocal chapters of the Order took on “tribal” names and used faux-Indigenous jargon. The Order also revived the legacy of early Tammany members like White Matlack.

Between 1875 and 1906, at least two chapters of the Improved Order of Red Men were established in the Kiskiminetas Valley. Somewhere in this timeframe, William Trout told T.J. Henry the tale of Chief White Mattock, Delaware real estate innovator. If Trout, the touted expert on Natives, joined one of those “improved” tribes, it might explain why he told Henry that Matlack-turned-Mattock was a sachem or chief. Matlack was a Tammany, the kind of man that many white men of Trout’s generation idolized: a skilled craftsman, a rebel against the crown, a patriot to his ruin. Trout would have wanted to celebrate Matlack’s story, to place him at the center of town. Perhaps Trout was like me — looking for a Leechburg he never knew, but wished he had.

Or perhaps Trout didn’t even know about White Matlack, but his fantasies took hold in a bit of unclear handwriting. Trout could have read the property records too fast, read “White Mattock” in place of “White Matlack.” “White Mattock,” like “Crazy Horse.” Stereotypes about Native names did the rest. Just describing things, all sparkling, lush, rich.

We who look like White Matlack used to imagine a White Mattock to tell us who we are, how we got here. That’s the way of the Tammanies and the Improved Order fill yourself up with stories from elsewhere, stories you’ve misunderstood. It’s wrong, we now say, and we know it doesn’t work. We’re aware that we’re seeing the Quaker Oats man wearing gemstone turkey feathers from JOANN Fabrics. We see the clipped coupons, the strip mall, and sewing projects-to-beabandoned. The question — What is Leechburg to me? — disappears behind the whites of town history. But, then, they turn transparent, too. I see the question again. It’s still there.

I wanted to know a Leechburg untouched by religious delusion. White Matlack and William Trout wanted to know a perfect America that never went wrong. Centuries apart, we’re still looking for unquestionable origins, but our origins are in the questions themselves, in the need to make an emptiness at the center of our history.

This article was adapted from an essay in Nobody’s Psychic: Finding & Losing Yourself, forthcoming September 2025 from the University Press of Kentucky. •

Thursday, February 27 - Saturday, May 31

Opening Reception: Thursday, February 27 6:00pm - 8:00pm Kelly Strayhorn Theater | 5941 Penn Ave.

ABY: COLLEEN HAMMOND

breathless three-story climb up the winding stairs of the Braddock Library transports audiences to The Return of Benjamin Lay, Quantum Theatre’s exploration of an 18th-century antislavery activist. The 80-minute show rolls the stone away and resurrects the legacy of a forgotten abolitionist under the shadow of a deserted basketball hoop.

Many of Lay’s words could be spoken before a modern congregation. Throughout the show, he frequently calls slaveholders apostates, and rightfully so. It’s hard to watch the piece without imagining Lay’s condemnation of those upholding the oppressors of today. In discussing the horrors of the colonialistic sugar trade, he breaks down the human

“Why do we call them goods when

they conceal the blood of those who labored in their creation?” Lay asks the audience, a stark reminder of the

The script by Naomi Wallace and Marcus Rediker, the University of Pittsburgh history professor whose The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the laid the groundwork for Quantum’s production, resurrects Lay’s impressive legacy of anti-oppression, but slowly deviates from triumphant antiestablishment speeches to didactic

“Are you willing to go to jail for

conscience?” Lay asks the audience near the show’s conclusion. The question hangs in the air for half a breath as audience members contemplate the current political climate and what laws they might have to break in the name of ethics and morality. This poignant question is cheapened when, immediately after, Lay directly asks the audience for a show of hands who would be willing to be jailed for their beliefs.

While the play’s finale is overly prescriptive, The Return of Benjamin Lay is a necessary retelling of an ordinary person who dared to do good.

Quantum, a company that has staged its productions at non-theater spaces across the city, possesses unique creative control over its environment. Each performance location is a creative gamble with the possibility to elevate the production to new, immersive heights.

The choice to convert Braddock Library’s

basketball court into a proscenium stage creates a noticeable distance between Povinelli and the audience. Even though he shines as a performer when interacting with the audience, the design of the performance space and seating bank perpetually keep Povinelli at arm’s length from the crowd. This creates an emotional distance from the play, ensuring that Povinelli must work significantly harder to gain the audience’s trust and engender their participation. However, the choice of venue allows lighting designers C. Todd Brown and Anthony Doran to show off their impeccable flair for the craft. The Braddock Library space presents two lighting designer nightmares: white walls and floor-to-ceiling windows. But, the lighting design refuses to shy away from the challenges and instead embraces them as a key storytelling device. The designers strung a strip of LED lights around the perimeter of

the theater in an off-kilter parallelogram shape. This choice could easily make the stage resemble a college dorm room but instead acts as a powerful ambiance tool that further demonstrates Lay’s inability to fit into the world around him. •

CONTINUES THROUGH SUN., FEB. 23 BRADDOCK CARNEGIE LIBRARY 419 LIBRARY ST., BRADDOCK. $20-73 QUANTUMTHEATRE.COM/LAY

• Yourfavorite live TV, showsandnews – localchannelsincluded L ocal channels maynot beavailable inall areas.Devicemayneed tobe in billing region in order to view local channels.

• Catch your favorite livegames withDIRECTV– leader in sports Claim based ono eringof Nat’l and Regional Sports Networks RSNs avail. with

E package or higher. Availabilityof RSNs varies byZIP code and package.

• 99% signal reliability* plus exclusive SignalSaver™ technology** *Based on Nationwide Study of representativecities.**Requires

Black residents’ fight to stop the construction of radio towers in the Hill Sugar Top highlights a forgotten history of environmental activism

BY: DAVID S. ROTENSTEIN // INFO@PGHCITYPAPER.COM

Sugar Top is the name that Black Pittsburghers gave to the highest elevation in the Upper Hill District neighborhood. Its bungalows, foursquares, and period revival homes were an attractive destination for the city’s upwardly mobile Black middle class in the first half of the 20th century. Moving to Sugar Top from the Lower Hill District became a badge of honor. Sugar Top residents protected their neighborhood from encroachment by urban renewal and land uses they believed would degrade their community.

Between 1 52 and 1 55, homeowners there mounted two campaigns to block the construction of new radio towers in their neighborhood. The battles became forgotten early episodes in a city with a long history of environmental activism. They were among a small number of 20th-century episodes involving Black residents resisting what they perceived to be environmental injustices.

“The richer more affluent African Americans [lived in] Sugar Top,” folklorist Hugo Freund wrote of the Hill District in 1992. “In Sugar Top, the houses are larger, mani cured and perhaps designed by architects.”

“Sugar Top was a hub within the Hill, but I looked at those people as the elite,” explains barbershop owner Michelle Slater, who grew up in the Hill District. “They were just a little bit, to me, higher class than just basic Hill people.” Slater’s grandmother once lived in Sugar Top with her common law husband, George Harris. George was the brother of racketeer William "Woogie" Harris and pho tographer Charles "Teenie" Harris.

It was home to Black lawyers, journalists, business owners, racketeers, athletes, and church leaders. So many pastors lived on the six-block Anaheim Street that it became known as “Preacher’s Row.”

Built in 1880, the Herron Hill Reservoir occupies the second-greatest elevation in Pittsburgh and is one of the highest points in Allegheny County. “The outlook from the summit is grand, and the Hill is worthy of a visit,” wrote Pittsburgh guidebook author George Thornton Fleming in 1916.

More than a century later, the panoramic view is still spectacular. The reservoir dominates a city park in the heart of Sugar Top originally named Herron Hill Park. The city changed the park’s name in 1984 to Robert E. Williams Memorial Park, honoring the city’s first Black magistrate.

By the 1950s, the Upper Hill had become established as the city’s premier destination for Black homeowners. But to city leaders, it was still a Black neighborhood that was fair game for urban renewal. As demolition ramped up in the Lower Hill, Upper Hill residents successfully mobilized to prevent the city from fulfilling urban renewal plans that included leveling 900 acres.

“Despite the devastation in the Lower Hill District and Middle Hill District, property values in Sugar Top have not declined,” Freund wrote. “Herron Hill and Sugar Top are very different from the stereotyped portraits of ghetto life that so often describes the Hill District.”

After World War II, radio and television towers sprouted in communities across the country. Broadcasters, telephone companies, and the Western Union Telegraph Company bought and rented land to build out new infrastructure.

Wartime advances in radio technology included microwaves for sending telegrams, long-distance telephone calls, and faxes. The Federal Communications Commission also began licensing television stations. Earlier technologies, like the use of radios in police cars, required towers. Broadcasters, telecommunications companies, and local governments saw Herron Hill and Spring Hill on the North Side as prime tower sites.

Some communities pushed back against

proposed new towers. Opponents testified before zoning boards and lobbied elected officials to prevent what many described as visual blight from encroaching on their neighborhoods. In Washington, D.C., residents of the Tenleytown neighborhood successfully forced Western Union to disguise a new microwave terminal as a silo-shaped building with concealed antennas; the company had scrapped an earlier design to camouflage it as a clock tower.

In 1947, KDKA built a 500-foot tower below Sugar Top near the University of Pittsburgh sports complex. It was far enough away from Sugar Top that there were no reported complaints ahead of its construction. WQED bought the tower in 1953 and replaced it with

a 593-foot tower that’s still visible from many parts of the city.

Other towers built inside the city after World War II included a Western Union microwave relay station in Northview Heights, completed in 1946, and television towers in Forest Hills, the West End, and South Side.

The tower wars arrived in Pittsburgh in 1951 when a contractor for the then-CBS affiliate WJS proposed building a 600-foot tower on Camp Street across from the Herron Hill Reservoir. The Pittsburgh Radio Supply House, Inc. approached city leaders requesting a zoning change to build the tower on Camp Street. Residents from Sugar Top, led by Black attorney and future councilmember Paul F. Jones, successfully defeated the effort, which would have included rezoning part of Sugar Top from “Residential” to “Slope.”

After failing to get the necessary approval,

the Pittsburgh Radio Supply House company sold its lots to a construction company, which built two homes there in 1955.

“RESIDENTS COMPLAINED TO CITY LEADERS THAT EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE WAS MAKING THEIR NEIGHBORHOOD ‘LOOK LIKE AN OKLAHOMA OILFIELD.’”

Another scrap over towers broke out in 1955 when the city proposed building a new police radio tower next to the reservoir. Herron Hill residents complained to city leaders that existing infrastructure was making their neighborhood “look like an Oklahoma oilfield.”

Many of the complaints aired in the February 1955 hearing turned on what were described as “sociological factors.” Public Safety Director David Olbum wrote a letter to the City Council in July summarizing the complaints and factors in favor of building the new tower. He vigorously denied that the location was selected because of its proximity to Black-owned homes. Olbum wrote that there was no attempt to “unload this alleged unsightly tower on the Herron Hill neighborhood simply because the population is largely or entirely Negro.”

After hearing the complaints, Councilmember and Sugar Top resident Jones temporarily killed the measure. It was revived a few months later after Jones announced that the opposition had been withdrawn. The 75-foot steel tower built in 1955 is still there today.

The Sugar Top towers were not isolated cases of local Black environmental activism. In 1965, Lincoln Park residents successfully forced Penn Hills to clean up sewage spills and dumping from East Liberty urban renewal activities in their neighborhood. Longtime Lincoln Park residents also recall that Helen Greenlee, wife of Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenley, bought two lots on her street to block the construction of new broadcast towers there.

Historians who have documented Black life in Pittsburgh acknowledge that environmental activism is a blind spot in their research. “The scholarship is sparse on this subject,” Carnegie Mellon University professor Joe Trotter emailed Pittsburgh City Paper in response to questions about environmental history and Black activism.

Trotter’s University of Pittsburgh colleague Larry Glasco agrees. “A most important topic but understudied,” Glasco emailed City Paper “I don’t know of an organized environmental movement, but searching the Courier under topic headings like trash, garbage, rodents and the like would turn up a lot of articles of Black residents complaining about unsanitary conditions.”

Pittsburgh Courier columnist Ethel Payne suggested that one reason Black residents bypassed environmental justice issues until the 1970s was that they were used to environmental racism. “Black folks used to laugh at white folks obsession with environmental protection,” Payne wrote in 1977. “Air pollution wasn’t no big thing with us. We’d been breathing bad ghetto air all our lives.”

The Sugar Top tower cases are a reminder that Pittsburgh has a long history of Black environmental activism. Some 21st century Pittsburgh residents might call those earlier e orts NI BYism. Yet, they helped to protect and preserve an important part of Pittsburgh’s history. •

Sal Vulcano: Everything’s Fine Tour 7 p.m. Heinz Hall. 600 Penn Ave., Downtown. $40.75-60.75. pittsburghsymphony.org

MUSIC

MUSIC

Performance Thursday: Luke Gallagher

5:30-7:30 p.m. The Mansions on Fifth. 5105 Fifth Ave., Oakland. Free. mansionsonfifth.com

TALK

Black History Month Lecture: David J. Dennis Jr. 6-7:30 p.m. Heinz History Center. 1212 Smallman St., Strip District. $5-10, free for students with valid ID. heinzhistorycenter.org

ART • DOWNTOWN

Opening Reception: Envisioning a Just Pittsburgh and Intermission. 6-10 p.m. August Wilson African American Cultural Center. 980 Liberty Ave., Downtown. Free. RSVP required. awaacc.org

DANCE • MIDLAND

Tom Sawyer: A Ballet 7:30 p.m. Continues through Sun., Feb. 23. Lincoln Park Performing Arts Center. One Lincoln Park. Midland. $18-25. All ages. lincolnparkarts.org/events

GAME SHOW • ALLENTOWN

Meet Cute: A Dating Game Show with Rick Sebak. 8 p.m. Doors at 5 p.m. Bottlerocket Social Hall. 1226 Arlington Ave., Allentown. $10. bottlerocketpgh.com

MUSIC • MILLVALE

MON., FEB. 24

Veronica’s Picnic with Favorite Band. 8 p.m. Poetry Lounge. 313 North Ave., Millvale. $5. poetrymillvale.com

Refuge: Somatic Magic Queer Dance Party 7-10 p.m. The Glitterbox Theater. 210 W. Eighth Ave., Homestead. $10-20 sliding scale. theglitterboxtheater.com

Folk February Concert Series: Addison Agen. 7:30 p.m. Doors at 6:30 p.m. Sweetwater Center for the Arts. 200 Broad St., Sewickley. $25. sweetwaterartcenter.org/folk-february

COMEDY • DOWNTOWN

Celebration of Black Comedy: Derek Gaines and Dave Temple 8 p.m. Arcade Comedy Theater. 943 Liberty Ave., Downtown. $25. BYOB. arcadecomedytheater.com

BURLESQUE • STRIP DISTRICT

The Velvet Hearts present Burlesque on the Rocks 9 p.m. Doors at 8 p.m. Kingfly Spirits. 2613 Smallman St., Strip District. $20. kingflyspirits.com

LIT • OAKMONT

Snag some free books while supporting a good cause at Mystery Lovers Bookshop

The ARC Fundraiser invites readers to take as many advanced reader copies (free preview versions of upcoming releases given to booksellers by publishers) as they want. In exchange, Mystery Lovers asks that guests leave a donation for PEN America, an organization created to protect free speech and support writers of all kinds around the world. 9 a.m.-1 p.m. 514 Allegheny River Blvd., Oakmont. Free. Donations accepted. mysterylovers.com

Bach Choir of Pittsburgh presents A Choral Celebration of Black History Month. 7:30 p.m. Continues through Sun., Feb. 23. Eastminster Presbyterian Church. 250 N. Highland Ave., East Liberty. $15-35. bachchoirpittsburgh.org

Tony From Bowling with Astrology Now and Rex Tycoon 8 p.m. Brillobox. 4104 Penn Ave., Bloomfield. $10. brilloboxpgh.com

MUSIC

Thula Sizwe in Concert: The Sounds of South Africa’s Indigenous Peoples 4 p.m. First Unitarian Universalist Church. 605 Morewood Ave., Shadyside. $5-30, free for kids under 12. pittsburghyouthchorus.org

Fight o cabin fever with a fun event at Spirit Bingo Bango presents the Summer Forever! Midwinter Cabaret, a night of BINGO, drag acts, burlesque, and more. An event description promises “a full cabana of special guests” coming together to help support Dreams of Hope Queer Youth Arts, a local organization focused on LGBTQ individuals between the ages of 13 and 26. 6-8:30 p.m. 242 51st St., Lawrenceville. $5 donation benefits Dreams of Hope. spiritpgh.com

Jessica Kirson 7 p.m. Byham Theater. 101 Sixth St., Downtown. $36-61.

TUE., FEB. 25

MON., FEB. 24

Pittsburgh Opera Fashion Show: Threads of Destiny at Bitz Opera Factory

MUSIC • DOWNTOWN

Chamber Music Pittsburgh presents Les Délices with Nicholas Phan. 7:30 p.m. Pittsburgh Playhouse. 350 Forbes Ave., Downtown. $35-55. chambermusicpittsburgh.org

CRAFTS • REGENT SQUARE

Community Craft Night 6-9 p.m. WorkshopPGH.

321 Pennwood Ave., Regent Square. Free. instagram.com/workshoppgh

FASHION • STRIP DISTRICT

Pittsburgh Opera invites audiences to a “dazzling evening of fashion and philanthropy” highlighting local designers and performers. The Threads of Destiny runway show at Bitz Opera Factory presents a “stunning visual narrative” inspired by “operatic masterpieces” like Madama Butterfly while “pushing the boundaries of modern couture.” The evening includes a pre-show presentation by local women’s wear designer Kiya Tomlin, designs by Nolan Kouri, and live performances by Pittsburgh Opera Resident Artists. 7:30 p.m. Doors at 6:30 p.m. 2425 Liberty Ave., Strip District. $15-55. pittsburghopera.org

MUSIC • NEW KENSINGTON

Make Them Su er with Like Moths to Flames, Aviana, and Windwaker. 7 p.m. Doors at 6 p.m. Preserving Underground. 1101 Fifth Ave., New Kensington. $25-30. preservingconcerts.com

FILM • LAWRENCEVILLE

Wicked Sing Along 8:15 p.m. Row House Cinema. 4115 Butler St., Lawrenceville. $12.50. rowhousecinemas.com

PODCAST • STRIP DISTRICT

The Sloppy Boys Podcast Tour. 7:30 p.m. Doors at 6 p.m. $30-35. City Winery. 1627 Smallman St., Strip District. citywinery.com/pittsburgh

MON., FEB. 24

ESTATE NOTICE

ESTATE OF FISHER, JAMES, P, A/K/A, IF NECESSARY, JAMES PAUL FISHER, JAMES FISHER DECEASED, OF CORAOPOLIS, PA No.02240189 of 2024

Joseph R. Fisher Extr. 210 Synder Drive, Corapolis, PA, 15108 Or to Caruthers & Caruthers, P.C. Attorneys. 660 Adele Drive, North Huntingdon, PA 15642

ESTATE NOTICE ESTATE OF CHALFANT, ROSS, D, DECEASED OF GIBSONIA, PA No. 022500526 of 2025 Arlyn Garcia Chalfant Executor, 3779 Bakerstown Rd, Gibsonia,PA,15044.

ESTATE NOTICE

ESTATE OF BARCHFELD, CHARLES, J, A/K/A, IF NECESSARY, CHARLES JOSEPH BARCHFELD DECEASED, OF BRENTWOOD, PA No. 022407914 of 2024

Richard W. Snyder Extr. 26 Dogwood Lane, Grove City, PA, 16127

ESTATE NOTICE

ESTATE OF BENSON, MARY, E, DECEASED, OF MONROEVILLE PA No. 022500887 of 2025, Carl J. Benson Extr. 421 Middlesex Road, McKeesport, PA. 15135.

Extra Space Storage, on behalf of itself or its a iliates, Life Storage or Storage Express, will hold a public auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extra Space’s lien at the location indicated: 1005 E Entry Drive Pittsburgh, PA 15216 on 3/5/2025 at 11:30 AM. John Quinn 3185, Justin Bush 4160. The auction will be listed and advertised on www.storagetreasures.com. Purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction.

Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the personal property.

Extra Space Storage, on behalf of itself or its a iliates, Life Storage or Storage Express, will hold a public auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extra Space’s lien at the location indicated: 700 E Carson St, Pittsburgh, PA 15203. March 5, 2025 at 12:15 PM. 148 Cole Thomson, 1056 Charlene Garcia-Otano, 4062 Karen Gault. The auction will be listed and advertised on www. storagetreasures.com. Purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction. Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the personal property.

Extra Space Storage will hold a public auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extra Space’s lien at the location indicated: 141 N Braddock Ave Pittsburgh PA 15208, March 5, 2025 at 11:00 AM. LC Lighty 1112A, Deonna Cohen-Beck 1184A, Darlene Hopkins 1211A, Sahira Muhammad 2185A, Nicole Frison 3087, Sheila Greene 3106A, Leebrun Massie 6038. The auction will be listed and advertised on www.storagetreasures.com. Purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction. Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the personal property.

PUBLIC AUCTION

Extra Space Storage, on behalf of itself or its a iliates, Life Storage or Storage Express, will hold a public auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extra Space’s lien at the location indicated: 111 Hickory Grade Rd. Bridgeville PA 15017, March 5, 2025 at 12:30 PM. Heather Davidson 2081, Tracey Wise 3294, Corrigan Adkins 3312. The auction will be listed and advertised on www.storagetreasures.com. Purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction. Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the personal property.

Extra Space Storage, on behalf of itself or its a iliates, Life Storage or Storage Express, will hold a public auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extra Space’s lien at the location indicated: 1212 Madison Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15212. March 5, 2025 at 1:30 PM. Tiernan Mallon L107. The auction will be listed and advertised on www.storagetreasures.com. Purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction.

Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the personal property.

Extra Space Storage, on behalf of itself or its a iliates Life Storage or Storage Express, Will hold a Public Auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extras Space’s lien at the location indicated: 902 Brinton Road, Pittsburgh, PA 15221 on Wednesday March 5, 2025 at 11:30am. 2229 Tiara Law, 2273 Dyese Street, 2292 Olivia Goughler. The Auction will be listed and advertised on www.storagetreasures.com purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction. Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the property.

Struggling With Your Private Student Loan Payment? New relief programs can reduce your payments. Learn your options. Good credit not necessary. Call the Helpline 888-670-5631 (Mon-Fri 9am-5pm Eastern) (AAN CAN)

Extra Space Storage, on behalf of itself or its a iliates, Life Storage or Storage Express, will hold a public auction to sell the contents of leased spaces to satisfy Extra Space’s lien at the location indicated: 880 Saw Mill Run Blvd Pittsburgh, PA 15226, March 5, 2025, at 1:15 PM. Lena Thomas 1016, Crystal Egenlauf 1032, Maggie Clemmons 1038, Ryan Small 1101, Caelon Johnson 2033, Melissa McGhee 2045, Ja’bree Thompson 3127, Nadia Branch 3154, Jakwuan Scott 4078, Adeshina Adetayo 4089, Season Acel 4216. The auction will be listed and advertised on www.storagetreasures. com. Purchases must be made with cash only and paid at the above referenced facility in order to complete the transaction. Extra Space Storage may refuse any bid and may rescind any purchase up until the winning bidder takes possession of the personal property.

The University of Pittsburgh’s Alcohol & Smoking Research Lab is looking for people to participate in a research project. You must:

• Currently smoke cigarettes

• Be 18-49 years old, in good health, and speak fluent English

• Be right handed, willing to not smoke before two sessions, and to fill out questionnaires Earn up to $260 for participating in this study.

For more information,

For more information on the available

and locations, please contact us at

SAVE BIG on HOME

Compare 20 A-rated insurances companies. Get a quote within minutes. Average savings of $444/year! Call 844712-6153! (M-F 8am-8pm Central) (AAN CAN)

1. Cuts down

5. “Schübler Chorales” composer

9. Castle defenses

14.

Maze goal

15. Outdoor feast

16. Straddling

17.

“I Just Want to Celebrate” band

19. VW compact sedan

20. With 43-Down, Strangers with Candy comic

21. It comes with Apple Intelligence

22. 100% legit

23. French pronoun

24. Letters before nicknames

26. Royal Canin rival

27. Plum loco

29. Kind of plane engine

31. Talk down to

33. Disney princess who sings “Into the Unknown!”

34. Sigur ___ (band that sings in its own made-up language Hopelandic)

37. Roadside restaurant’s dare

39. First president of The Ninety-Nines: International Organization of Women Pilots

41. ___ health

42. Eye part

44. Kinda blue

45. Playwright Balzac

47. Takes advantage of

48. Genesis victim

50. ___ Lobster

51. Hair color tint

52. Sports radio fodder

54. Slash’s band?

56. Reciprocal of sine: Abbr.

59. Give to the church

60. Flowering evergreen plant

62. Perfect picture

63. Pepper processor

64. Sticky substance

65. Breathmint brand

66. Where a Princess migh stop

67. Group that might say “skibidi” or “rizz”

1. Daughter of Cronus and Rhea

2. Course finale

3. Sinewy and lean

4. O ice building rm.

5. Assign fault

6. Superstar’s vibe

7. Persian bakery?

8. “What was that?”

9. Magic charm

Baby’s covering 11. Proceeding thus

Head piece? 13. Fights 18. Brainiac

22. Little House on the Prairie setting 23. Its flag has a prominent beehive

25. Leafy green 27. Loverboy

28. Place that puts on avant-garde productions

30. Co ee and Cigarettes director Jim

31. Seek change

32. Proofreader’s finds

35. Table scraps

36. Mud room?

38. Word next to a harp on €1 coin

40. “Be quiet”

43. See 20-Across

46. Ancient history

48. Bedroom cover?

49. Woman in white

51. “Someone Like You” singer

53. Fish served in unaju

55. Box in sudoku

56. John of the Velvet Underground

57. Knock out

58. Word in many French restaurants

60. “Stop talking,” briefly

61. Scotch ___

Let Pittsburgh City Paper help you hire! Every month, over 400,000 people visit pghcitypaper.com for news, entertainment, and job listings.

New jobs are posted every Sunday online and in our Tuesday City Pigeon e-newsletter.

Contact T’yanna McIntyre at tmcintyre@pghcitypaper.com to advertise your job listing in City Paper.

•

PITTSBURGH VARIOUS LOCATIONS

•

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION of the SCHOOL DISTRICT OF PITTSBURGH ADVERTISEMENT FOR BIDS

Sealed proposals shall be deposited at the Administration Building, Bellefield Entrance Lobby, 341 South Bellefield Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15213, on February 25, 2025, until 2:00 P.M., local prevailing time for:

ADMINISTRATION BUILDING

• Water Cooler Replacement

• Plumbing and Electrical Primes

PITTSBURGH BROOKLINE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

• Air Conditioning

• Mechanical and Electrical Primes

PITTSBURGH ROOSEVELT EARLY CHILDHOOD CENTER

• Finish Floor Replacement and Miscellaneous Work

• Abatement, General, and Plumbing Primes

PITTSBURGH WESTINGHOUSE ACADEMY 6-12

• Stair Tread Replacement

General Prime

Project Manual and Drawings will be available for purchase on Monday February 3, 2025, at Modern Reproductions (412-488-7700), 127 McKean Street, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15219 between 9:00 A.M. and 4:00 P.M. The cost of the Project Manual Documents is non-refundable. Project details and dates are described in each project manual.

EACH YEAR, PITTSBURGH REGIONAL TRANSIT HONORS LOCAL HEROES WHO WERE TRUE PIONEERS IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT.

RECENTLY, WE HONORED THE LATE CONSTANCE B.J. PARKER AND THE LATE ROB PENNY WITH THE 2025 SPIRIT OF KING AWARD FOR THEIR EFFORTS TO PROTECT AND DEFEND EQUAL RIGHTS.

PRT IS PROUD TO CELEBRATE THE LIVES OF THESE TWO INDIVIDUALS AND ALL TRAILBLAZERS WHO HAVE HELPED PAVED THE WAY FOR OTHERS TO OVERCOME BARRIERS INCLUDING RACISM AND INEQUALITY SO THAT THEY, TOO, COULD REACH THEIR FULL POTENTIAL.