Paris

65

Marie-Rouge, May 26. Paris diary 3.

66 67

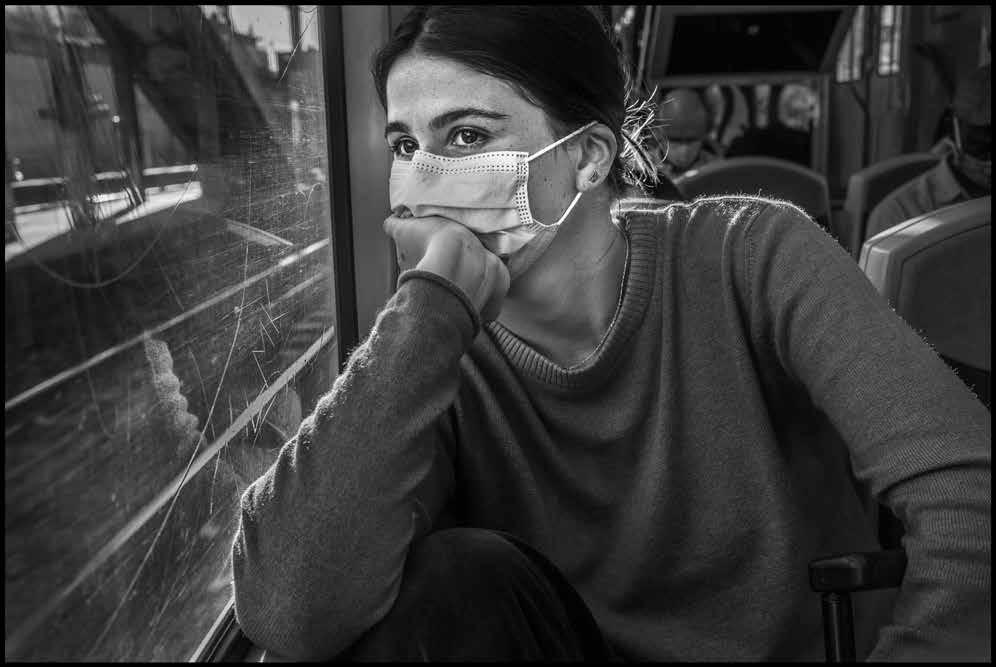

Inés, 18, Paris métro. June 25. Paris diary 43.

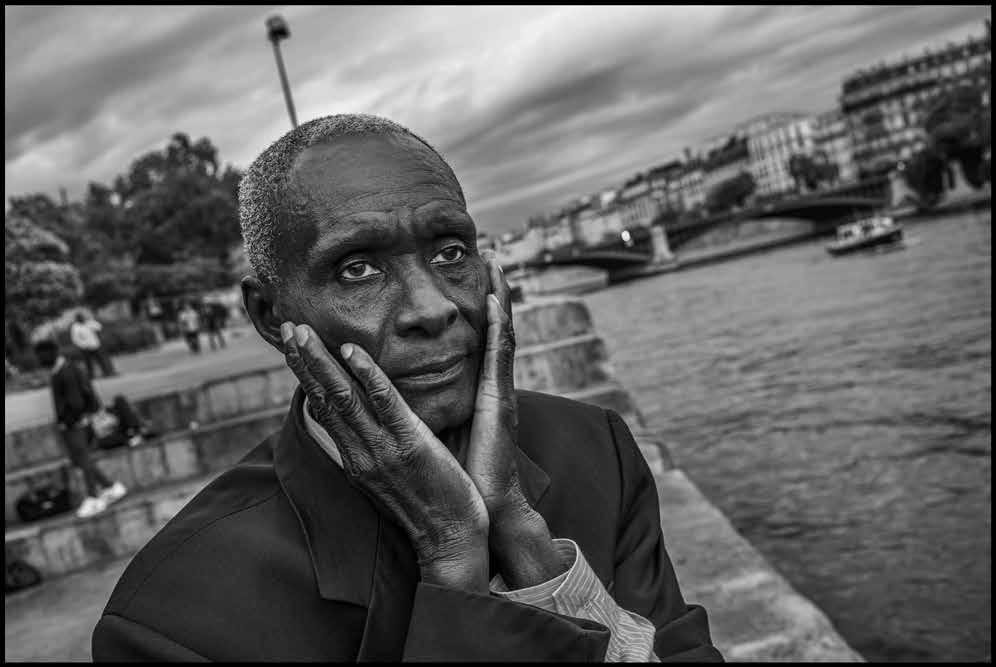

Abdelaziz, 64, at the grave of his mother, a victim of Covid-19. St. Denis, France. May 29. Paris diary 8.

68 69

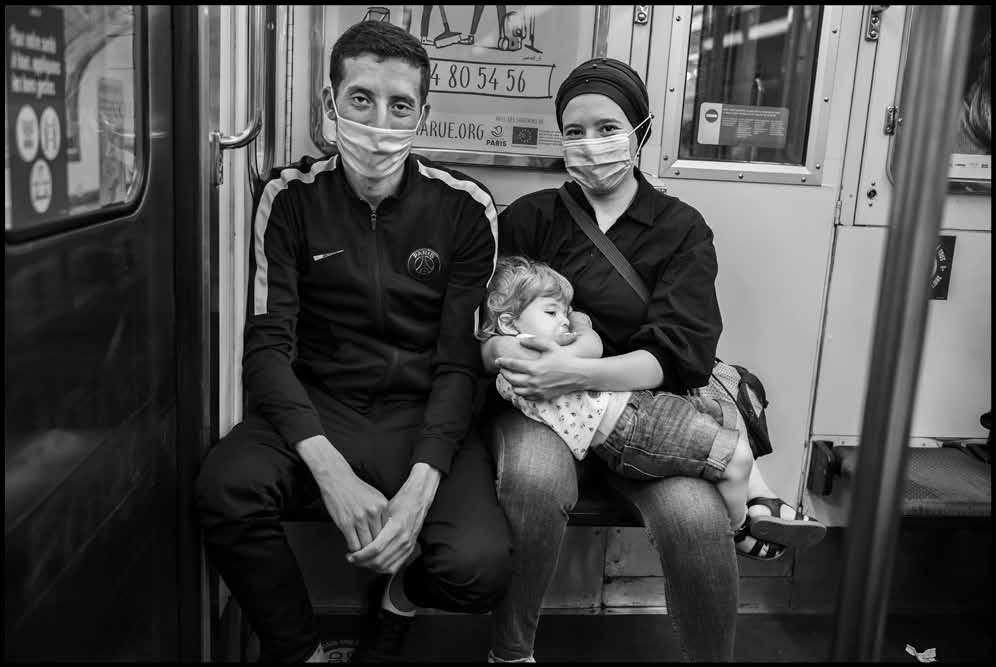

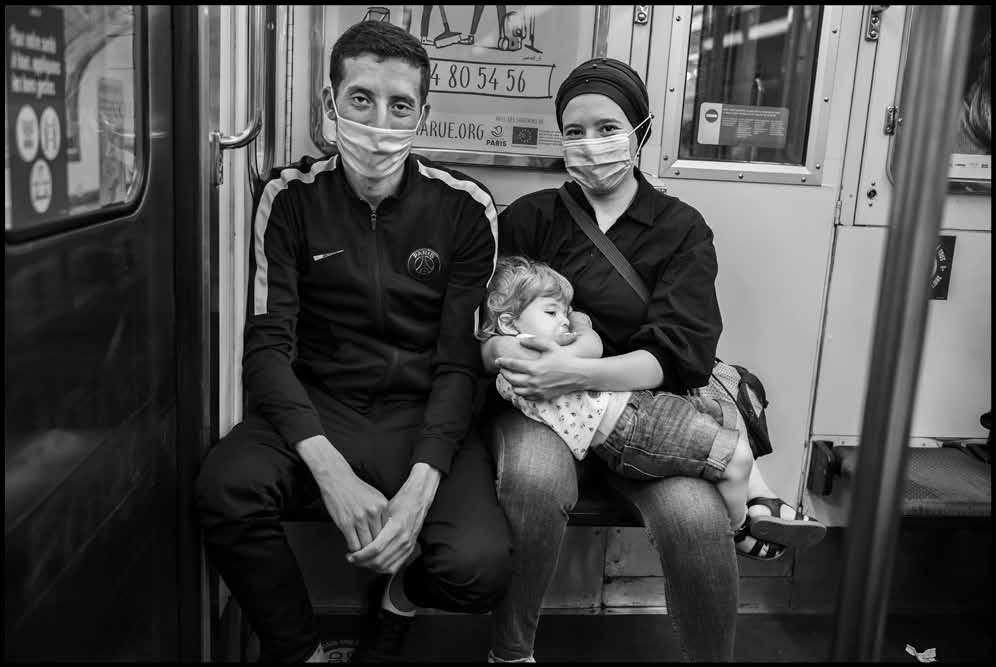

Paris métro. May 26. Paris diary 4.

Nur, Café de Flore. July 9. Paris diary 58.

70 71

Touré, a delivery person, Arc de Triomphe. June 4. Paris diary 15.

Philippe, Café de Flore. June 28. Paris diary 46.

72 73

Paris métro. May 26. Paris diary 4.

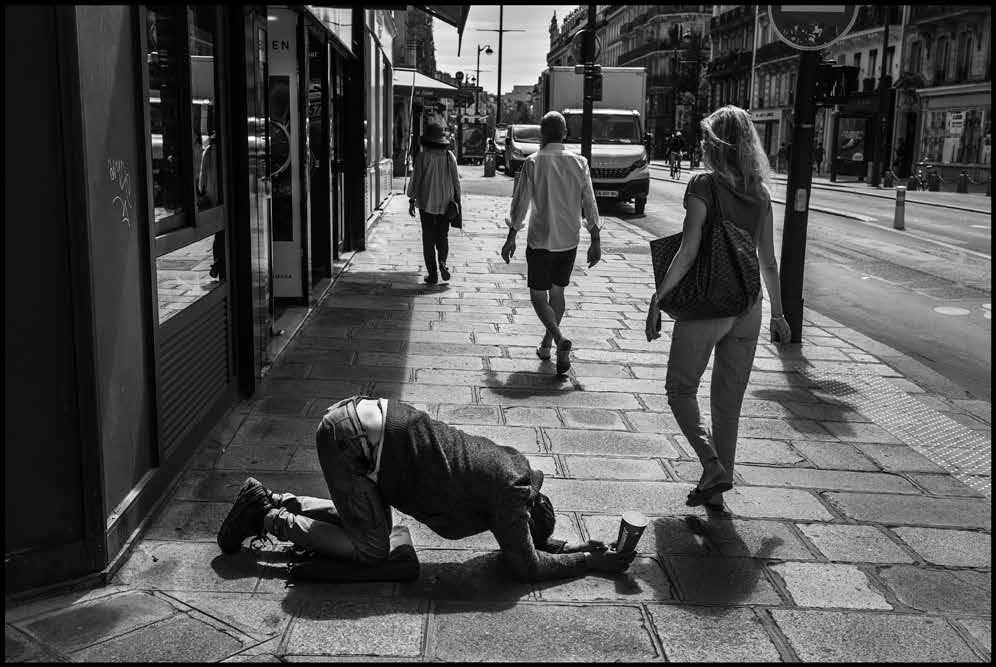

André, Boulevard St. Germain, June 28. Paris diary 46.

74 75

Eugenie and Jean, 90 and 92, married since 1952. June 28. Paris diary 46.

Sara and Eric. May 31. Paris diary 11.

76 77

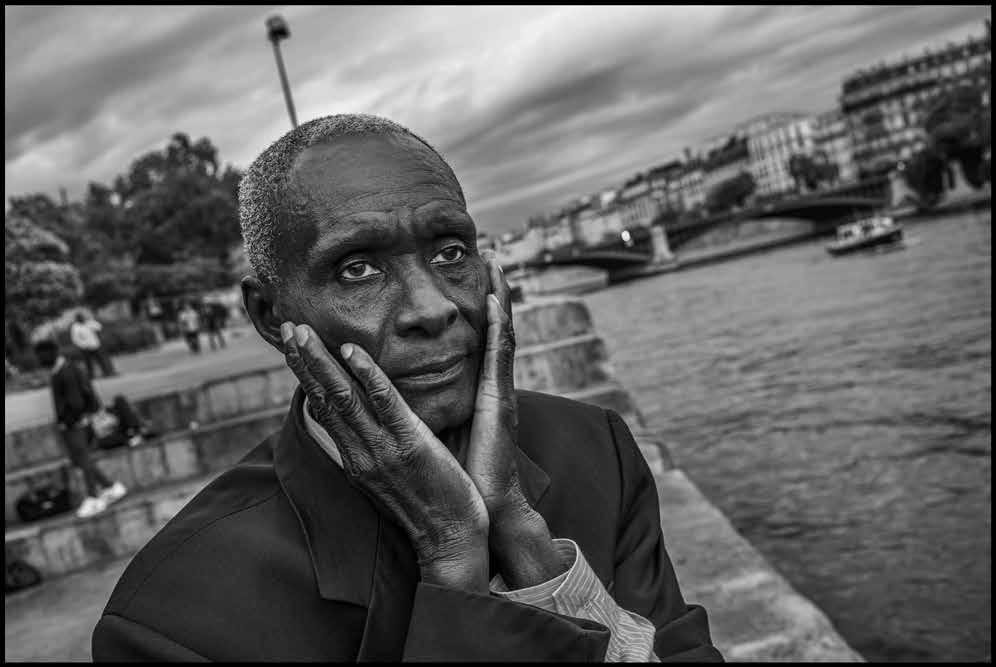

Mamours, banks of the Seine. July 14.

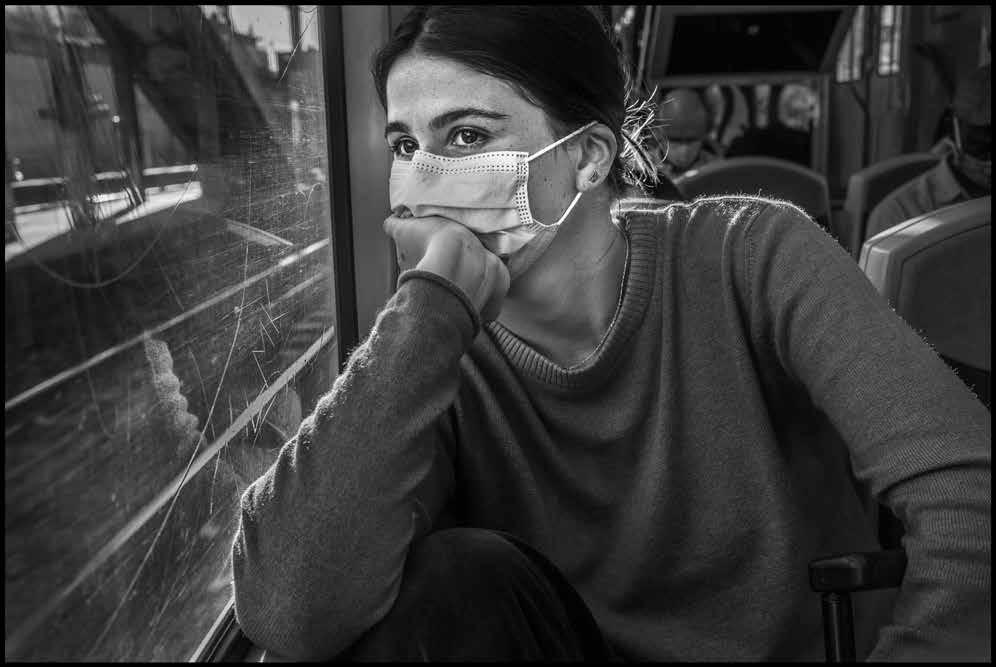

Alice on a train to Paris. July 11. Paris diary 59.

78 79

Ditl, from Moldova, sings in the métro with his family. July 5. Paris diary 53.

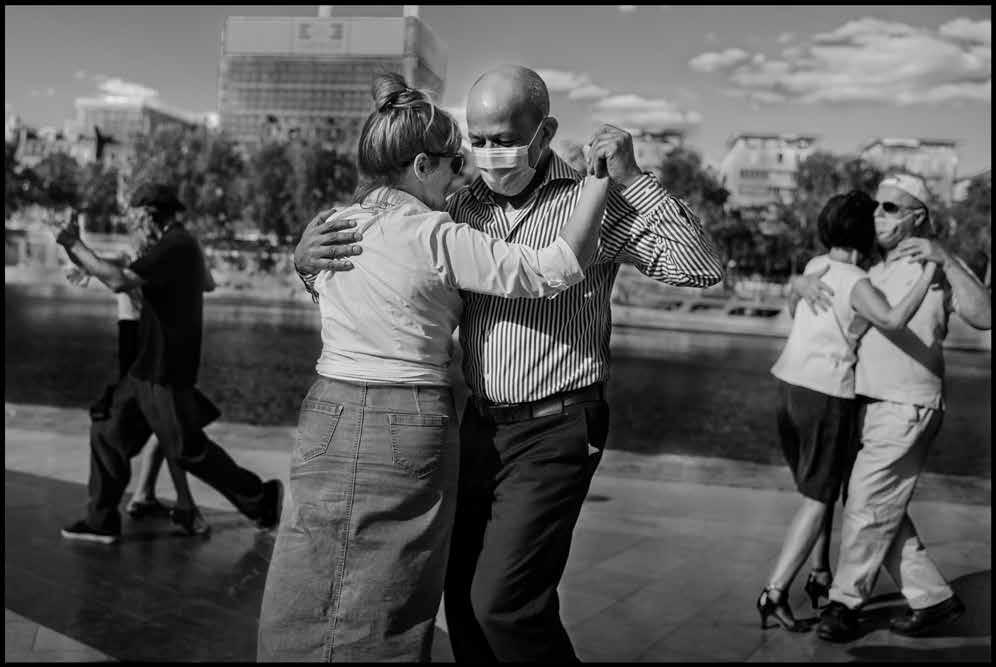

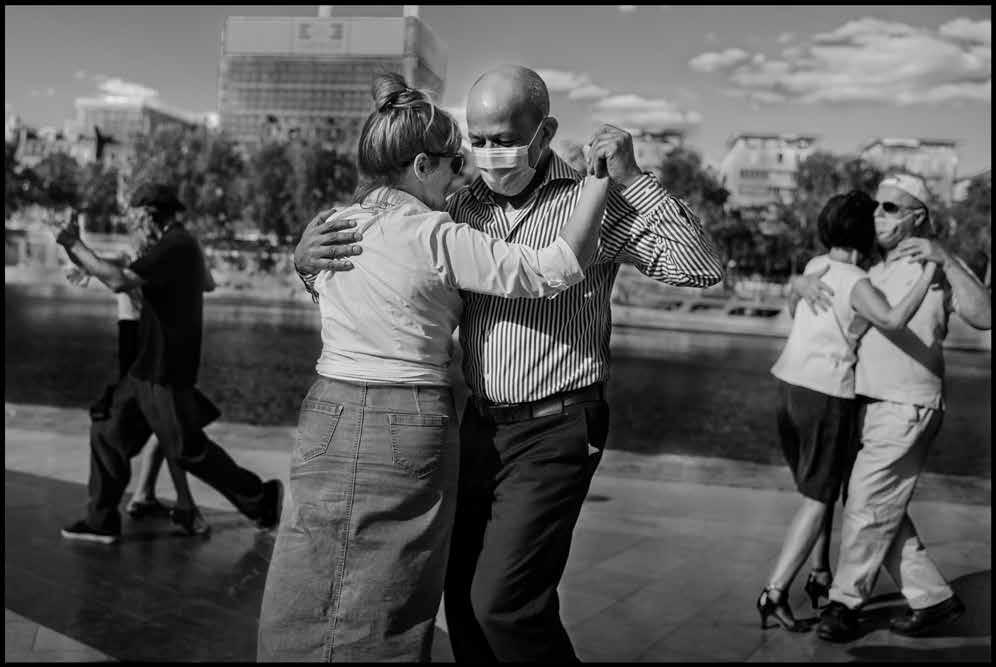

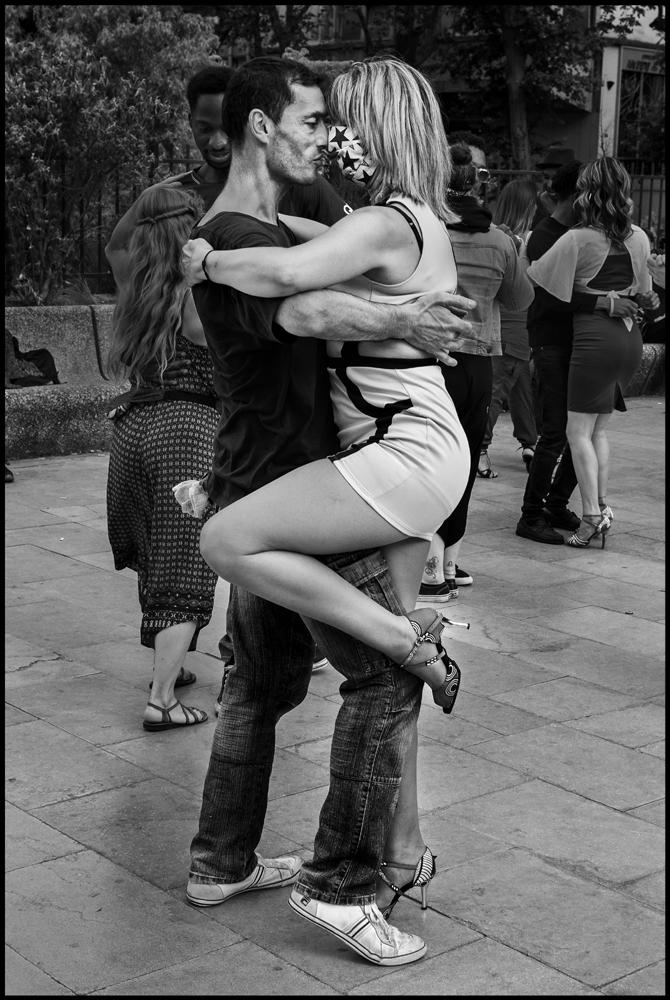

Tango. Banks of the Seine. May 31. Paris diary 11.

80 81

Mustafa, bus driver, Place de la Concorde. May 26. Paris diary 4.

La Gare du Nord. June 29. Paris diary 47.

82 83

Josephine and Ange, rue Poulet, near the Chateau Rouge métro. June 29. Paris diary 47.

Odette, 94, with her daughter Chantal. June 28. Paris diary 46.

84 85

Safia, on the first day the Louvre reopened. July 6. Paris diary 55.

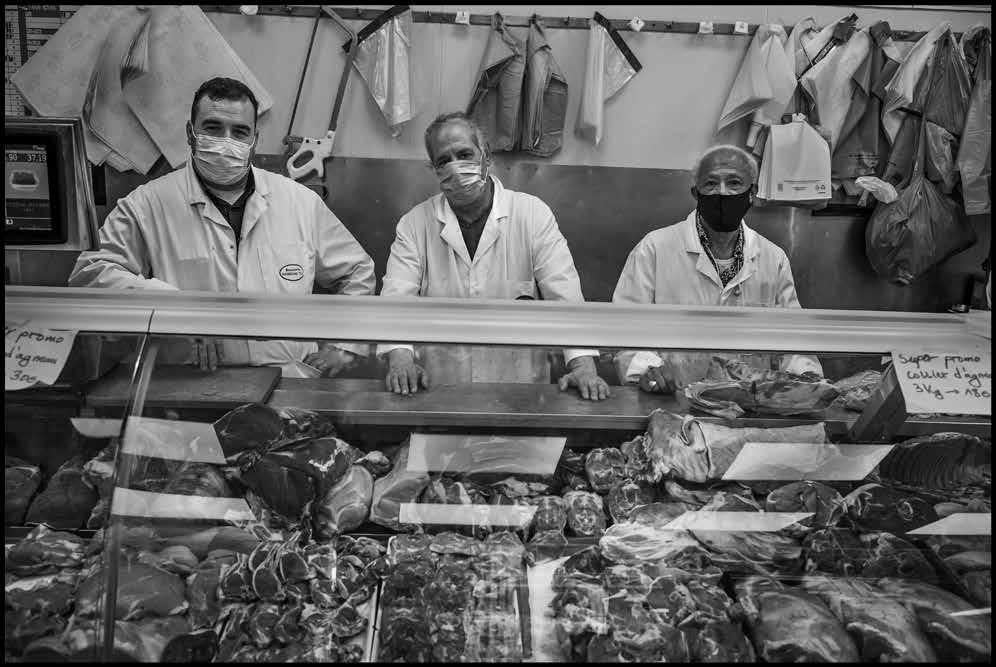

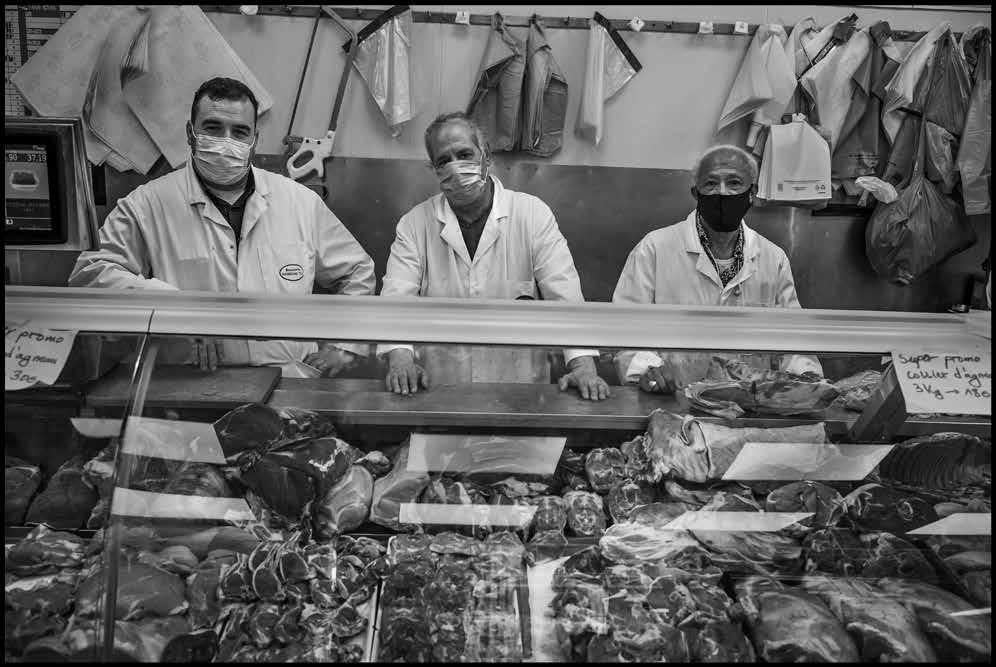

Butchers Ahmed, Djilali, and Said, Boulevard de la Chapelle. June 29, 2020. Paris diary 47.

86 87

above: Maria, 25, and Alex, 30, at the Louvre the first day it reopened. July 6. Paris diary 56.

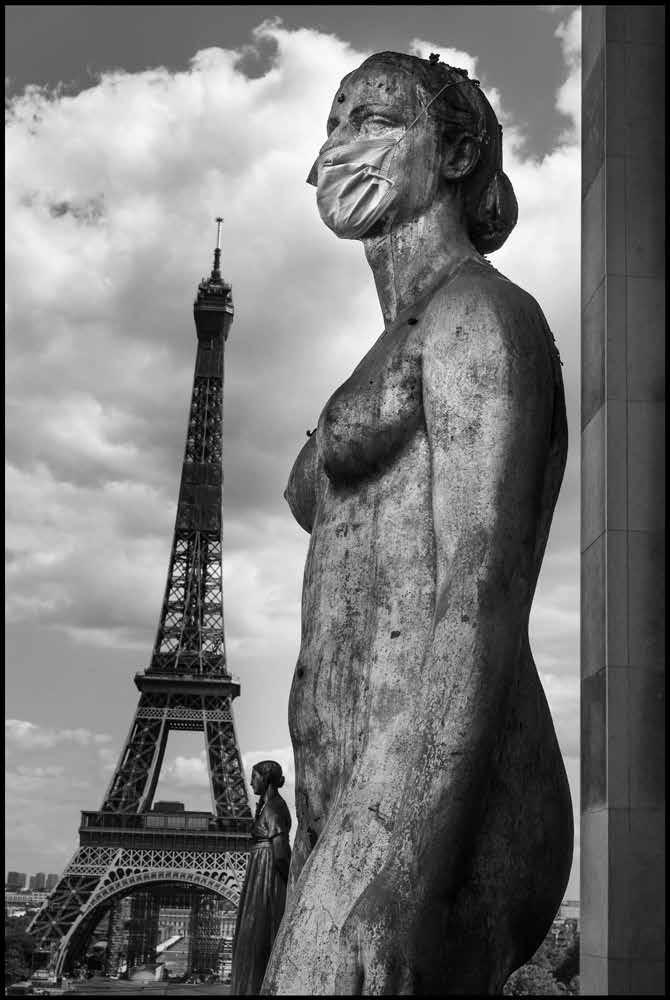

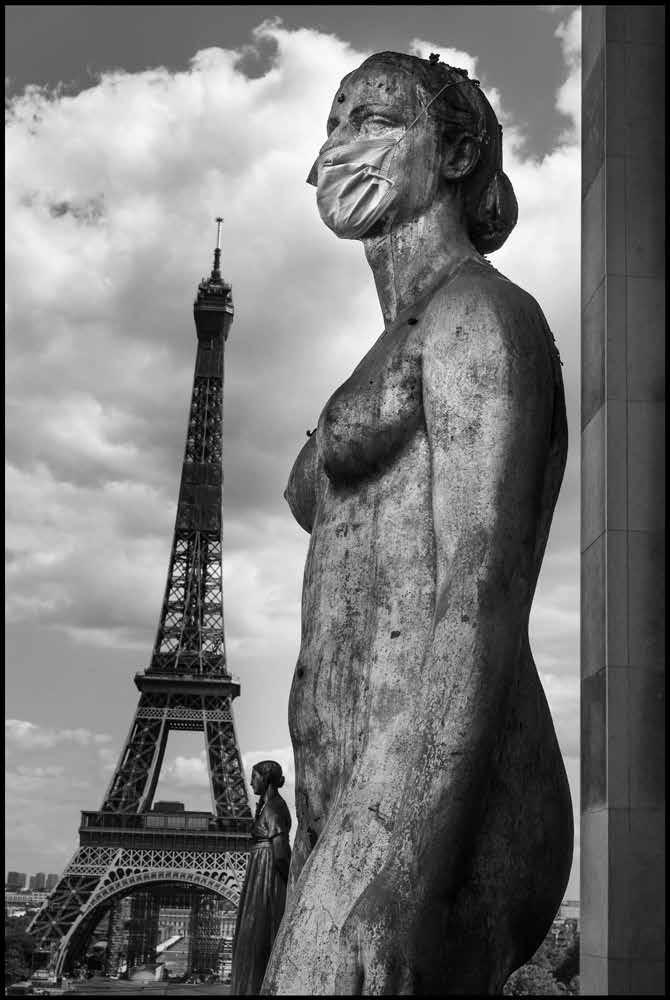

opposite: Esplanade du Trocadéro. May 25. Paris diary 2.

88 89

Monsieur Henri. July 3. Paris diary 53.

Childa and her daughter Victoria on a train to Paris. July 11. Paris diary 59.

90 91

Laura and Louis, L’Hotel de Ville. June 20. Paris diary 36.

Patricia, 70. July 4. Paris diary 53.

92 93

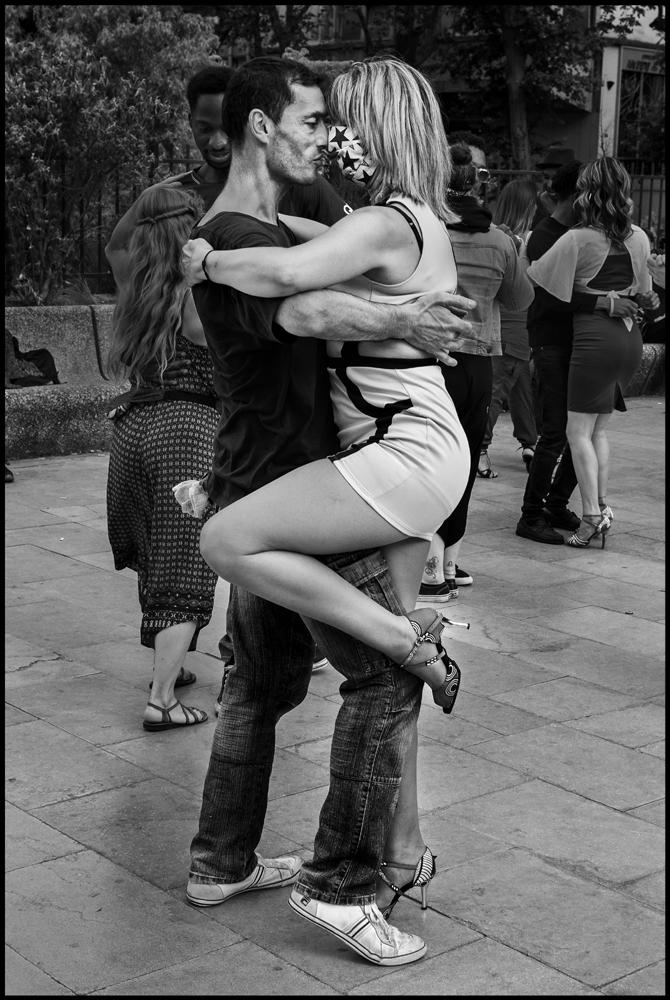

above: Dannick and César, Le Marais. May 27. Paris diary 6. opposite: Dancing Kizomba along the banks of the Seine. June 21. Paris diary 37 and 67.

94 95

Sarah has her hair done for the first time in three months by a friend. Gare du Nord. May 28. Paris diary 7.

Rue Marcadet, 18th Arrondissement. June 29. Paris diary 47.

96 97

Omar plays the Guembri, banks of the Seine. July 25. Paris diary 66.

Rue St. Croix de la Bretonnerie. July 21. Paris diary 65.

98 99

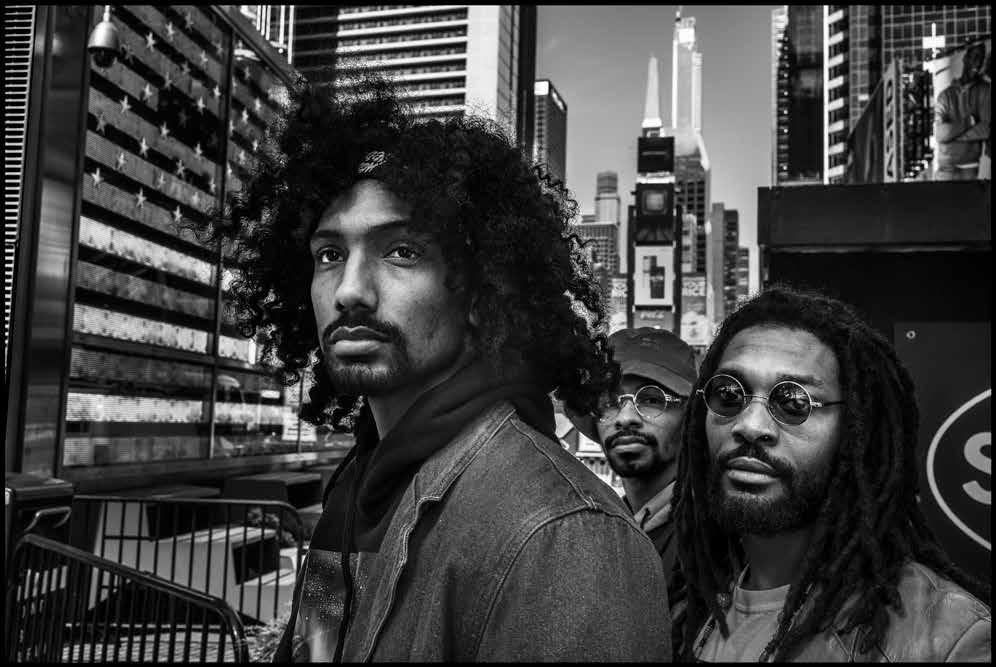

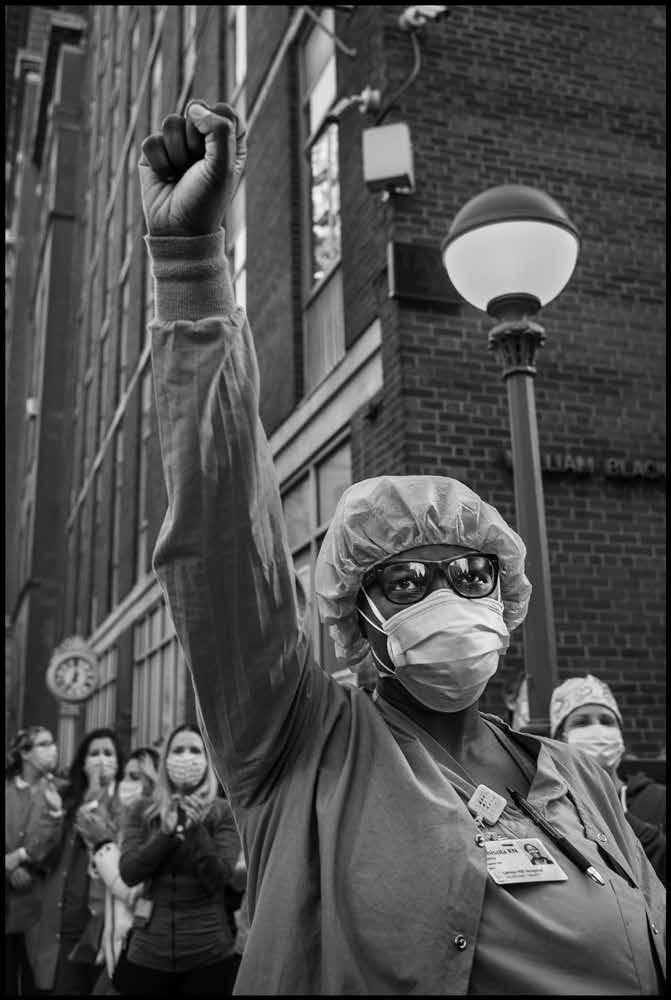

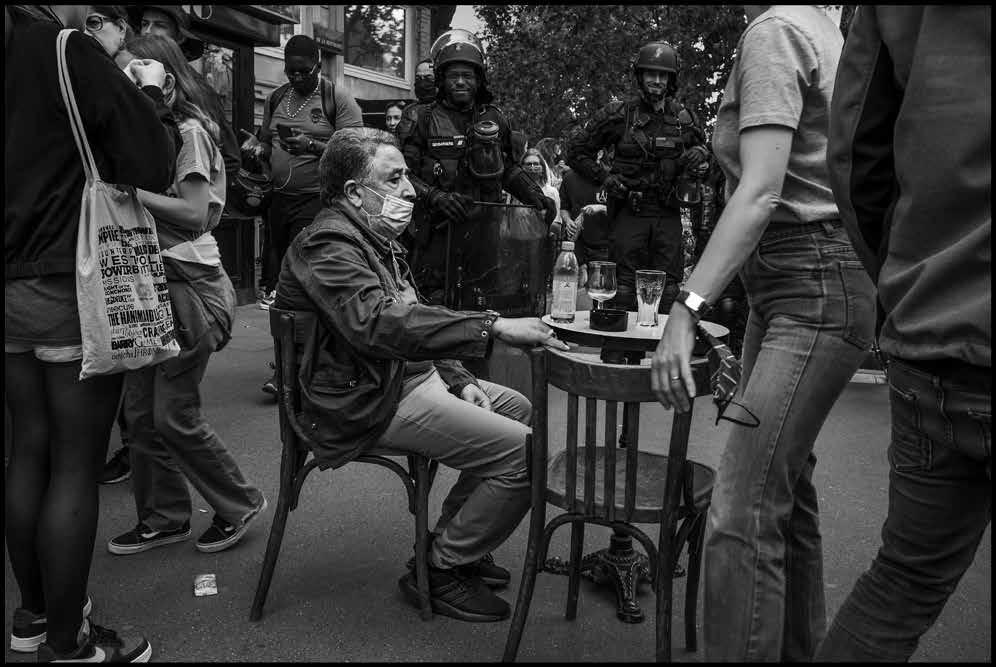

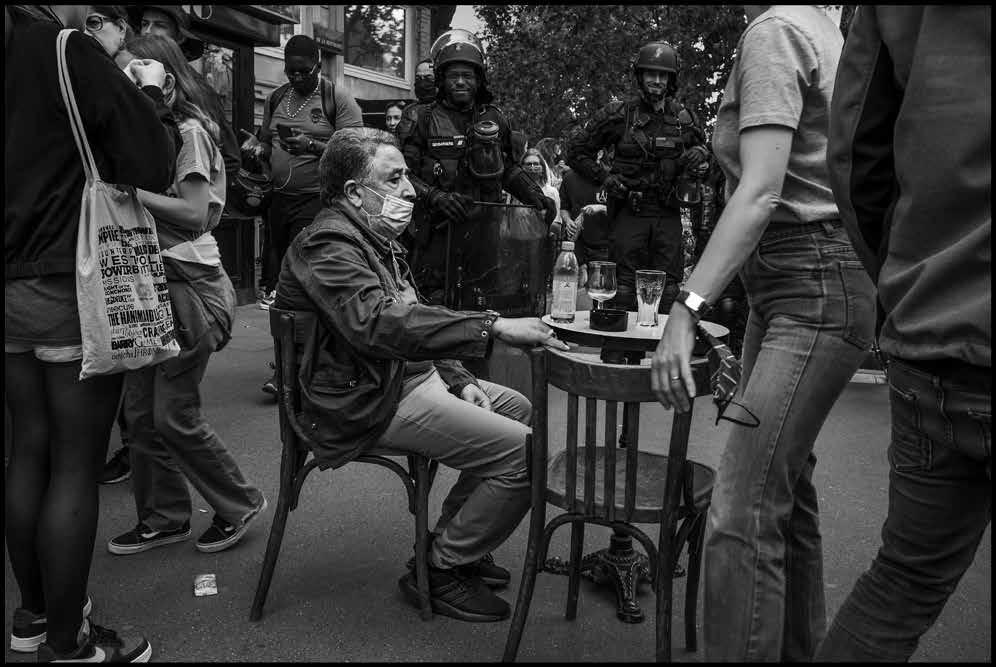

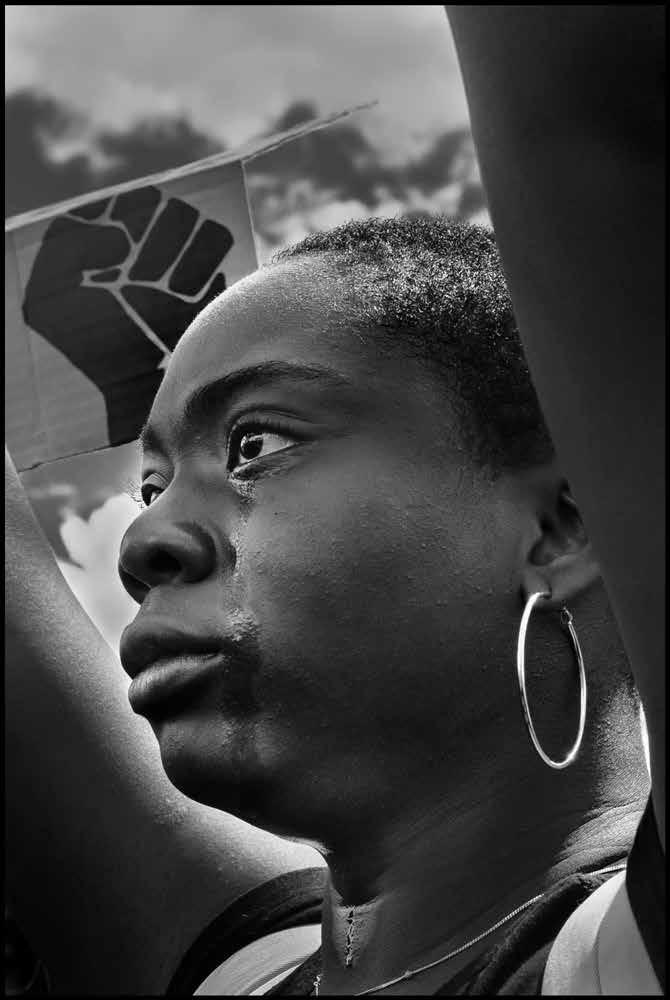

Demonstration against racism and police brutality, Place de la République. June 13. Paris diary 27.

Demonstration against racism and police brutality, Place de la Concorde. June 6. Paris diary 16.

100 101

Cléopatre, café at Hotel de Ville. June 16. Paris diary 32.

Gilbert. June 6. Paris diary 29.

102 103

Paris métro. June 29. Paris diary 47.

Kid Ally, on a train returning to Paris, July 11. Paris diary 59.

104 105

Arnaud and Karim, waiters at La Brasserie de l’Isle Saint-Louis. June 3. Paris diary 14.

Monika, Café Les Deux Magots. June 25. Paris diary 41.

106 107

Le Louvre the first day it reopened after “confinement.” July 6. Paris diary 55.

Florin, Gare du Nord. Paris, May 28. Paris diary 7.

108 109

Priyadarshika and Bharit. May 28. Paris diary 7.

Anita, 22, on the first day the Louvre reopened after “confinement.” July 6. Paris diary 55.

110 111

above: Hayat and Tidia, mother and daughter, mourn the death of a husband and father, Arezki Ammi, a victim of Covid-19, St. Denis. May 29. Paris diary 8.

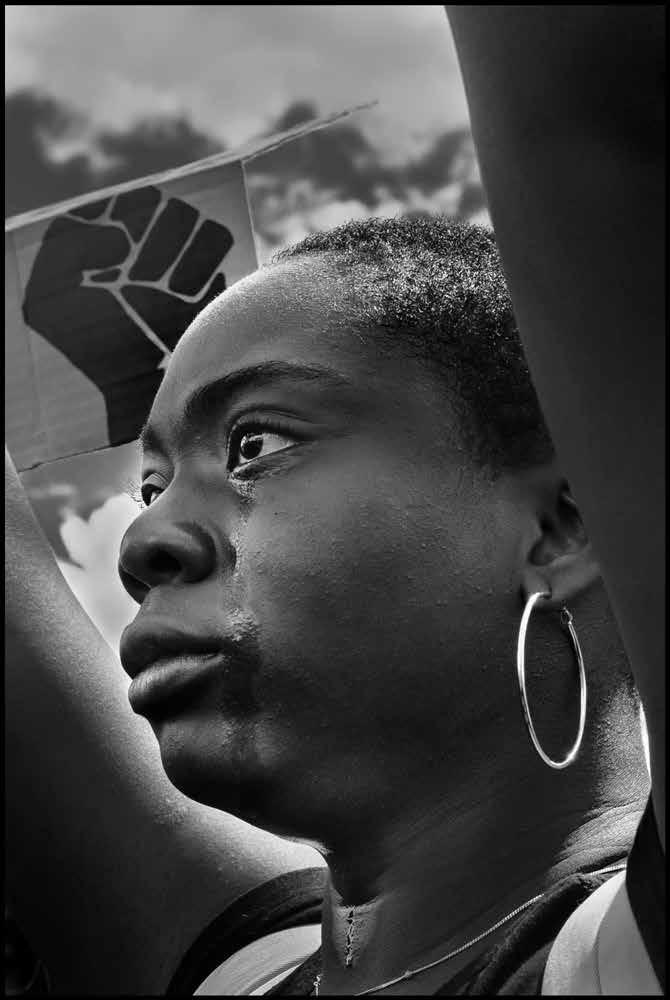

opposite: Black Lives Matter march against racism and police brutality, Place de la Concorde. June 6. Paris diary 16.

112 113

Pascal, photographer, Café de Flore. June 2. Paris diary 13.

Vassa, Café de Flore. July 8. Paris diary 57.

114 115

Banks of the Seine, June 21. Paris diary 37.

Rue du Pont Louis-Philippe. June 23. Paris diary 40.

116 117

Jean, 92, Café L’Etoile Manquante, rue Vielle du Temple. July 2.

Roger. June 11. Paris diary 24.

above: Pont Louis-Philippe. June 22. Paris diary 39.

opposite: Café Les Deux Magots. June 8. Paris diary 21.

118 119

120 121

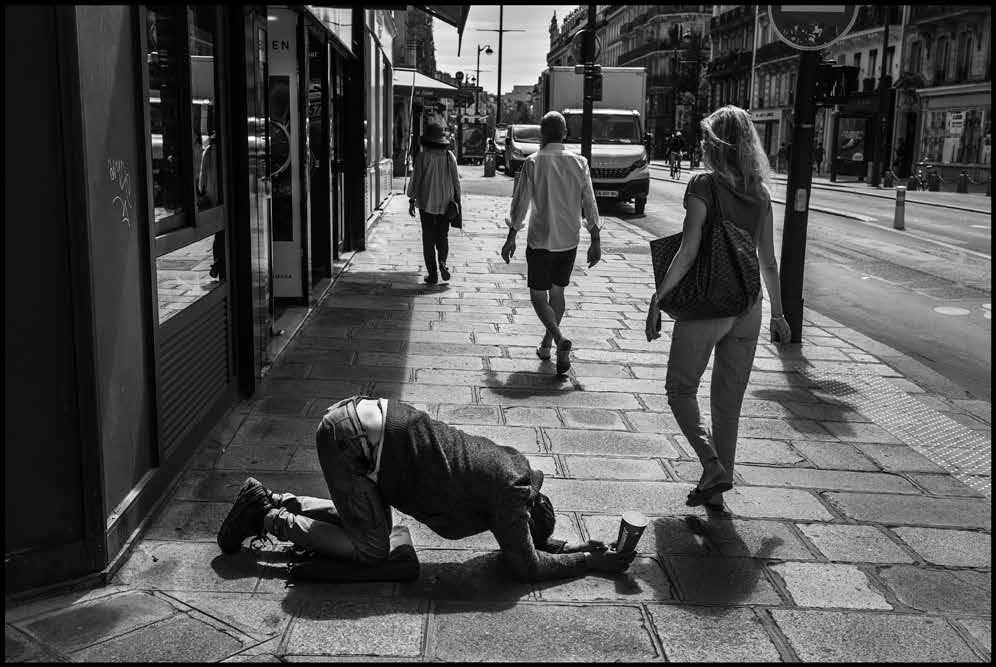

Rue de Rivoli. July 8. Paris diary 64.

Melania, Champs de Mars. June 26. Paris diary 45.

A New York Visual Diary

March 20, 2020, diary 1 (see page 11)

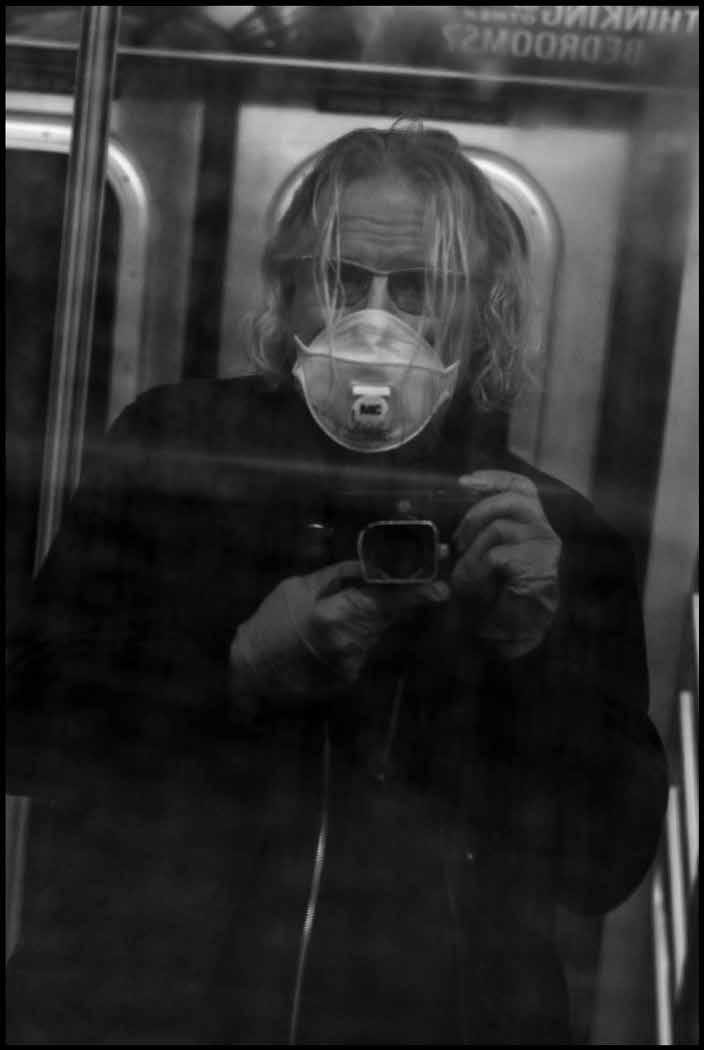

I woke up today and decided that even with the risks involved, I needed to go out and help be the eyes for a city that is in lockdown. I’ve been to many war zones in the world over a long time. On 9/11 I spent the late afternoon and night in the rubble of ground zero. We have entered a new form of war zone— more mysterious, unknown—it may last longer than some, and it will strike in the middle of where most of us call home.

I walked several hours through Manhattan and returned on the subway. Often there was no one around except more homeless people than I’ve ever seen—this is likely more noticeable exactly because often there is no one else around. The subway had the feeling of being a dark, risky tomb of necessity. I confess to being a bit shaken upon my return home from this day. I share here much of what I saw and felt. I hope you will share it with others. I’m not ashamed to say that I shed a few tears this afternoon. There are moments when duty calls, and it certainly felt that way for me this morning. I send love to all.

March 23, 2020, diary 2 (see pages 27 and 32)

It rained coronavirus cats and dogs today in New York City—both figuratively and literally. New York is ground zero of the pandemic in the U.S. Late afternoon, I went out and walked north on the Upper West Side. Within a few hours, I came across so much of the reality of this moment—and of the melting pot of New York—and the courageous people who perform essential jobs to keep life going for so many. I encountered a gentleman who was out for groceries, and as I photographed him, he looked up at the sky and declared, “It is raining, but it is a beautiful day!” I came across Natalia, from Odessa in the Ukraine, standing alone on the sidewalk at 83rd Street. A postal worker, delivering mail without a mask, Jason, told me with a smile, “I am not scared.” A bus driver opened his door and welcomed a photograph with a smile before taking off at a light. I walked past a laundromat where a woman working with a mask went about her chores in front of a washing machine, while Diallo, a young woman from Guinée, sat waiting for her wash to finish. A young man with a baseball hat prepared to take out the trash for a building on the Upper West Side. A doorman stood behind revolving doors with his mask on, proudly wearing his doorman’s uniform. Finally, as I arrived at 96th Street, I took a cab and asked Mohammed, a driver from Bangladesh, how he felt, and he told me, “I am scared to death.” I was very careful to keep a distance from all I photographed and felt somewhat comforted by the heavy rain. My life must go on, and I will be careful. I return to my home alone, and I am very careful with gloves and mask and immediately put the clothes in the laundry and jump in the shower, and I wash my hands often. But both my heart, and these times, need to carefully bear witness to the humanity of this moment— and, as carefully as possible, to indelibly convey the courage and hearts of so

many in the middle of a war zone, in the heart of the most energetic city in the world that fights back as it can.

March 24, 2020, diary 3 (see page 15)

New York is now the epicenter of the coronavirus crisis in the world. The hearts of this city continue to beat, and there are so many moving stories of courage and life going on and how people are coping during this lockdown. While wearing mask and gloves and keeping always a careful 6-foot distance from all with whom I come in contact, I think it is essential to share with the world the stories of this moment through photojournalism. I also return each day to where I live, alone. Yesterday I went out and again walked north. I came across Clifford standing at a bus stop hoping to receive some money to help him eat at this time. At the Happy Warrior Playground on the Upper West Side, 6-year-old Taji was shooting baskets—at a safe distance from everyone else—with his mother, Latoine. She told me Taji really misses school and Taji told me he was going to grow up to be the next Kobe Bryant. He seemed already like a champion to me. Loren was walking with her dog, Molly, and Joe looked through the window of a famous deli, Barney Greengrass—The Sturgeon King. Jacob, a nurse at Sloan Kettering, jumped rope at a safe distance. Rosario from Guatemala waited for a bus, and Rummy returned home, basketball in hand, from shooting baskets alone in a park. At the 125th Street Harlem train station, a mainstay station for many people working in the city who commute in each day, I came across several of New York’s heroes of this moment: Haymar, 29, a medical student from Myanmar who works in a Harlem medical clinic; C., a doctor, on his way home; and Linda, an oncology nurse who works at Mount Sinai. I will never forget the night of 9/11, when I was in the rubble of ground zero and a nurse walked up to me at 3 am and offered me her mask. I couldn’t accept it but will never forget her selfless kindness and gesture. Yesterday, after speaking to Linda, the nurse, for a while about how this moment is affecting her, she reached into her bag and offered me an extra mask for future days.

All over the city, I saw people very carefully keeping a social distance from each other, and I did too. In the midst of this crisis, the heartbeat of this dynamic city beats much slower, but the hearts of so many that I see each day profoundly remind me how strong the heart of this city is.

March 26, 2020, diary 4 (see pages 14, 23, and 28)

Today was a day of meeting heroes and encountering ironies.

As I moved carefully around the city today, I encountered so many heroes—doctors, nurses, policemen, subway workers, home health aides, union representatives, cleaning women, and many others. There was a strong irony to this day. On a day when the United States and in particular New York now have the most confirmed cases of coronavirus, it was a gloriously beautiful early spring day. Weather and light bring back memories: I will always remember that September 11, 2001, was one of the most beautiful days ever, the sun shining bright in a gorgeous blue sky, on that tragic day that changed our world.

Today, as I crossed the Brooklyn Bridge, seeing a person with a mask jogging alone on the bridge, I got down low to photograph her, and just as she arrived in front of me she jumped in the air. I called out and asked her name and where she was from. She replied that her name was Yanan and said she was from Wuhan, China. On Wall Street, I met an investment banker, Arthur, who told me he had grown up homeless for a period, and so he is optimistic that things will get better—this is only temporary. As I turned the corner onto Wall Street, I saw a lone woman sitting on the sidewalk, begging for money for food. On a day when Congress was voting on the biggest economic stimulus package in U.S. history, I met MJ, a freelance fashion stylist, who asked me, “What will $1,200 do for a person like me living in New York who won’t have work for months?”

I wonder if many others are going through what I am feeling today. My emotions often are like a roller coaster. Most of the time, particularly when I am sharing the visual stories of so many who are true heroes in this historic moment, I am uplifted and their example gives me courage and hope. Then there are moments when so much of this new reality and its unknowability, how it is changing our world in known and unknown ways, challenges the spirit. But, when I finish my day walking and encounter Lesley, a 46-yearold subway worker, standing with a big, wide smile—and who with pride tells me that she has just come from disinfecting the 23rd Street subway stop as part of her job—I say to myself, if Lesley can be this strong and generous and courageous, I certainly owe it to her and everyone else to do the same. There is only one New York—a special, strong, amazing city of wonderful people.

March 27, 2020, diary 5 (see page 35)

Today I have been inside most of the day. When I went out for groceries at a local store, I came across Priscilla, worshiping the sun. She was careful to stay 6 feet from her neighbor, as I did from her while making this photograph. We spoke for a short while, and she said, “It is so sad to stay inside all day—I had to come out to get some sun.” How well we all understand her feelings—just what so many of us are feeling and thinking too.

March 27, 2020, diary 6 (see pages 17 and 33)

Today I saw a lone elderly woman sitting on a bench in the rain at a place only yards from where I lived for seven years at 133rd and Lenox in the center of Harlem. Mary, she told me, was her name, and when I asked how she was making it, she replied, “By the grace of God.” She looked about the same age as my mother, who recently passed at 94. As I photographed, two young men walked by and said, “Why don’t you give her your umbrella.” So I walked up to her and handed her the umbrella I had just bought an hour earlier. I turned to look up the street toward the two young men and saw that they had been watching me—they broke out into big smiles and gave me the thumbs-up. I wish it had been my idea first, but as I walked away, it occurred to me that in this moment, not only are we all together in this situation, but we can help each other become better people.

I walked this morning for hours, almost 80 street blocks. This morning, I woke up and saw a video of life in Venice—a place I’ve been to very often and love so much. This video of this unique city across the earth from where I am, but so close to my heart, reminded me so much of our common humanity

In New York, still the epicenter of this crisis in the United States, with the most cases of coronavirus in the world, every life is affected, and every person I encounter has a story that is part of our collective story. So many of the people I encounter are true heroes, people doing essential work, or people simply struggling to get by. Aldalkiris, 21, works the cash register at a local grocery store. Kevin is a garbage collector. Markus is homeless and sits hoping to receive some money to eat—when I asked him how he was doing, he told me, “It’s rough.” I asked him if he was scared and he told me, “No, I was scared when I went to ’Nam.” Joe, a doorman who works in a building on the Upper West Side, has to take a bus to Queens near Elmhurst Hospital, where, he told me, “There are so many dead they have to put them in a freezer truck.” I came across a young man and we talked for quite a while and he said to me, “You know, you are the first person that has spoken to me today.” Two elderly gentlemen were standing at social distance speaking to each other on Lenox Avenue near Harlem Hospital. I asked them how they were making it, and one of the men replied, “WelI, I woke up again today.” I asked again, really, how he was making it? And he offered, “We’re never really making it—every time we come close, they come up with something to keep you down farther.” Mary, a stay-at-home mother returning from the grocery store, told me, “We’re doing the best we can.”

Each day I venture out during this time of our collective world crisis to document as safely as possible this moment in history, I am reminded of both the strength and courage of so many individuals, and of us, collectively all together, like Mary, just trying to do the best we can. Last night, around 7 pm, on the street where I stay on the Upper West Side, I heard loud applause and shouting as if something important was happening on the street. I ran outside with my camera. On a densely populated street of 5-story buildings, every window was filled with people spontaneously clapping and shouting— and this went on for twenty minutes. I asked someone what this was about, and they told me it was a way to thank the healthcare workers in New York. I, too, clapped hard for more than fifteen minutes, went back inside, and sat down and cried.

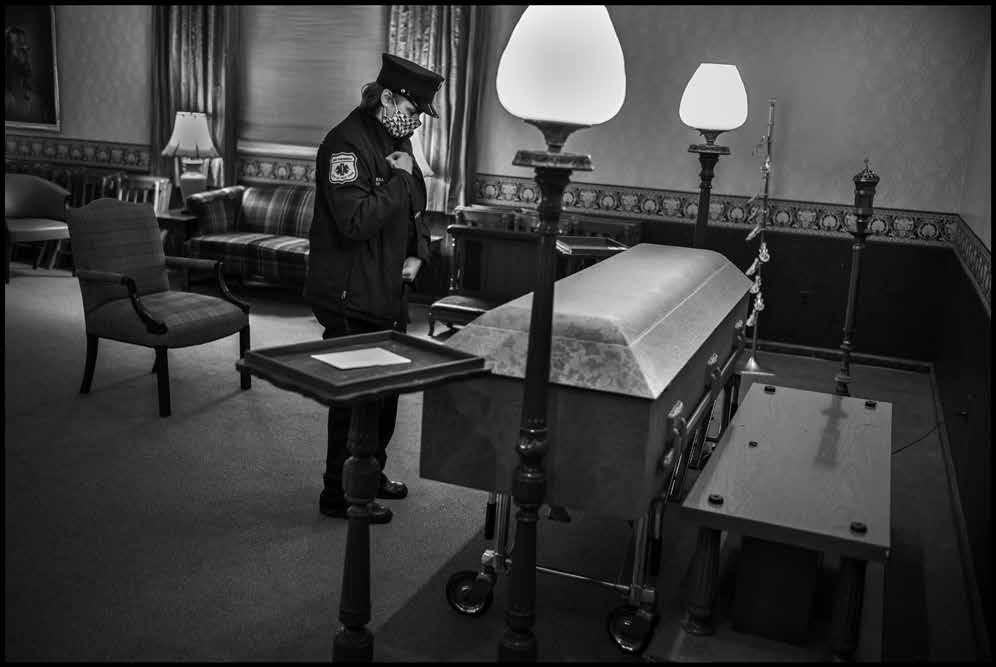

March 29, 2020, diary 7 (see pages 12, 18, 40, and 50)

I went today to the very eye of the storm of this crisis, Elmhurst Hospital, in Queens, which is possibly the most intense war zone in the United States at this moment. At the back of the hospital, dozens of ambulances were lined up. I spoke to an ambulance medic, Mike Galloway. He told me, “With 9/11, once it happened, you could see it coming. This is an invisible enemy. We don’t see what is coming. I could be sitting next to my partner and he could have it and we don’t know it. We don’t have enough protective gear, and I’m not the only

122 123

one that feels that way.” He works with an ambulance unit attached to Jamaica Hospital but for now attached to the New York Fire Department.

A few minutes later I spoke to Ethan, 29, another ambulance worker. When we began to talk, he was on his mobile phone. He stopped to speak with me and said, “That’s my wife—she’s scared for me.” I asked him if he had a child, when all of a sudden, over his phone came the loud, beautiful voice of a child, “I love you, Daddy!”

I didn’t cry just then, but I do as I write this. There are so many heroes in the midst of this moment that affects the entire world—and most of them will go forever unnoticed. I wake up each day and go out, and I always keep at least 6 feet from all people, and wear a mask and gloves, and when I am finished, I return home and stay alone. I am extremely careful with social distancing, but I think it is essential that the stories of so many heroes of all stripes be documented through photojournalism, helping to bring us together now, and for memory, forever.

Behind the hospital, several ambulances pulled up, their sirens wailing, and ambulance workers jumped out to take off stretchers loaded with urgentcare patients. It was not always clear which patients were suffering from coronavirus or from other ailments, but there was no doubt that coronavirus was overtaking this moment. Daniel, 26, another ambulance worker, told me, “It’s tough. It’s a lot at once. Had a lot of patients with symptoms. We call them fever coughs.” Carla, 32, an ambulance driver, told me, “You do what you got to do. We’re overwhelmed.” Another ambulance worker who preferred not to be photographed or named said to me with the most beautiful, soft voice, “It’s going to take time, but we will get through this. ” She then walked away, her head down, asking for no recognition for her work—and once again, I had come across another hero who wakes up each day, does the best she can in the most dangerous circumstances, and looks ahead to life with hope.

Fabrice, another ambulance worker, told me as he put an empty stretcher in the back of an ambulance, “I’m not scared, but this is my first shift during this crisis.”

An 81-year-old man, Charlie, walked by the back of the hospital using a walker. He stopped, looked at me, and said, “I’m trying to make the best of a bad situation.”

As I waited for the train back to Manhattan, a lone woman, Jessica, from Ecuador, stood waiting as well. I asked how she was doing, and in Spanish, she told me, “Not well. My father-in-law, who was 58, died last night from coronavirus. He lived in America for twenty-five years.” I realized it was possible she might have been going about her day without anyone to share that pain and g rief.

Eventually the train back to Manhattan arrived and I got on. I am most scared when I need to be on a train. I always feel very lonely there, and most often in the train I am alone. As the train raced toward Manhattan, at one stop the doors opened and there was a billboard with the famous photograph by Dorothea Lange The Migrant Mother. Dorothea may have been the greatest

documentary photographer in history, and seeing this photograph now and thinking of her gave me a boost of courage—I knew Dorothea would be working right now.

When I arrived at the Times Square stop to change trains to head uptown, a young couple, Stephon, 24, and Fidaus, 21, originally from Ghana, were sitting close together on a bench waiting for the train. I asked them if they were a couple and they said yes. I asked them how they were making it and they told me, “It’s scary, and there is so much chaos—but we have kind of become closer during this time.”

I was reminded that, as always, there is only one thing that gives us power and hope, and that is love.

As I rode the last leg of the train uptown, my train passed a homeless man lying asleep on the subway platform with a small sign with the word kindness These are really hard days. For all of us. But as a professor once told me, along with love, there are only three things important, the first is kindness, the second is kindness, and the third is kindness. And, if the anonymous ambulance worker can tell me that we are going to get through this—knowing what she is risking every moment at this time—I certainly can have the courage to go forward with hope as well.

March 30, 2020, diary 8 (see page 45)

Today I stayed home all day except for going out to buy groceries. As I returned to the apartment where I stay in the Upper West Side, on the sidewalk I saw a man standing, waving and gently smiling to someone in a window. I stopped and the gentleman departed. In the window, I saw Roxie, a 90-year-old woman everyone on this street knows. At this point in her life, she can no longer walk, and she is always sitting at the window. When I finished making this photograph of her, she put her hand to her mouth and blew me a kiss. I asked her if she was okay and she replied, “I am fine—if I need anything, I will give you a call.” Roxie put everything into a certain perspective for me today as we live through the serious storm that has blown into all of our lives. She has lived through ninety years of good and bad weather, and after all this time, she looks out at the world, happy to connect with everyone who lives near her, and gives us all hope and courage. If I can find and demonstrate only a fraction of the grace she shows, always, I will feel very blessed. And, this moment, and this photograph, remind me, with all of the beauty of the freedom to travel, there is glory, and light, to be noticed and found, right next door.

March 31, 2020, diary 9 (see pages 21 and 43)

We are clearly now at war—a serious war where we will lose more people to our common enemy of coronavirus than have been lost in many of the wars I have covered worldwide.

Almost every day since the beginning of this crisis, with mask and gloves I go out with my camera, keep social distance from all, and return home alone. There is a new aspect to my documentation of this crisis—besides

making photographs of the people I encounter, I take the time to speak with everyone, almost always asking their name, age, and how they are making it. It has become so clear that this war, taking place in one of the places I call home, New York (I am also a permanent resident of Paris and now have French nationality alongside being American), is our collective war, and the battle indiscriminately touches everyone. Every person is a target of this enemy and every person has a story. Never before have I encountered a situation where it is clear that absolutely every single person I encounter has an interesting and important story—and these stories have become and will forever be ours.

Yesterday I walked to the post office, and as I was walking in, a man wearing a mask exited. When I told him he looked like a bank robber in that mask, he laughed, and we struck up a conversation. Eric, 64, is originally from Detroit. He said he had been a fashion model and had traveled the world and had made a good living—“but I was born in the gutter,” he said. He was orphaned and adopted, and when he was an adult, he had tracked down his birth mother. The first time he spoke to her on the phone, he said to his birth mother, “I’ll bet you think of me on my birthday,” and she replied, “I don’t even know your birthday—I don’t even know your name.” He has worked out daily his whole life and has always asked himself, “Am I ready to save my own life?” With his frequent world traveling for work, he explained, “I am used to self-isolating, and since I was an orphan, I have learned to appreciate and have gratitude for all.”

Later, walking through Central Park, I saw many people walking, jogging, sitting in reflection, all at safe social distance. I encountered a couple, Bob, 97, and Karen, 83. Karen told me, “I am stressed—I find myself double-thinking everything.” They were sitting on a bench, and a young child ran by with its parent, and Karen said, “Seeing children go by is life enhancing.” Bob was born in 1923 and has lived through the Depression and fought in Germany in World War I I. He misses seeing his grandchildren, and when I asked him, after all he has seen, what he could teach me about life, he replied, “Stay close to your kids and be a good citizen.”

Martin, originally from Manchester, was playing the saxophone in the park. I asked him how he was handling this crisis, and he told me, “Music is a kind of defiance.” This spoke to me deeply, as I have always felt that way profoundly about photography, and with this diary—I am fighting back.

Earlier in the day, I encountered Patrick, 74, sitting alone on a bench at 80th and Broadway. He told me, “When the leaders become grown-ups, we’ll get this solved. I pray they really grow up. We have so many blessings on this earth to be happy about. It’s time for us to be more real. We got everything we need. Got to give thanks to the creator for creating all of us. We have enough for everyone to be happy. The billionaires won’t be takin’ it to the grave. There are too many homeless people. We all fall down sometimes. People share with me; I share with you. That’s what makes the world grow.”

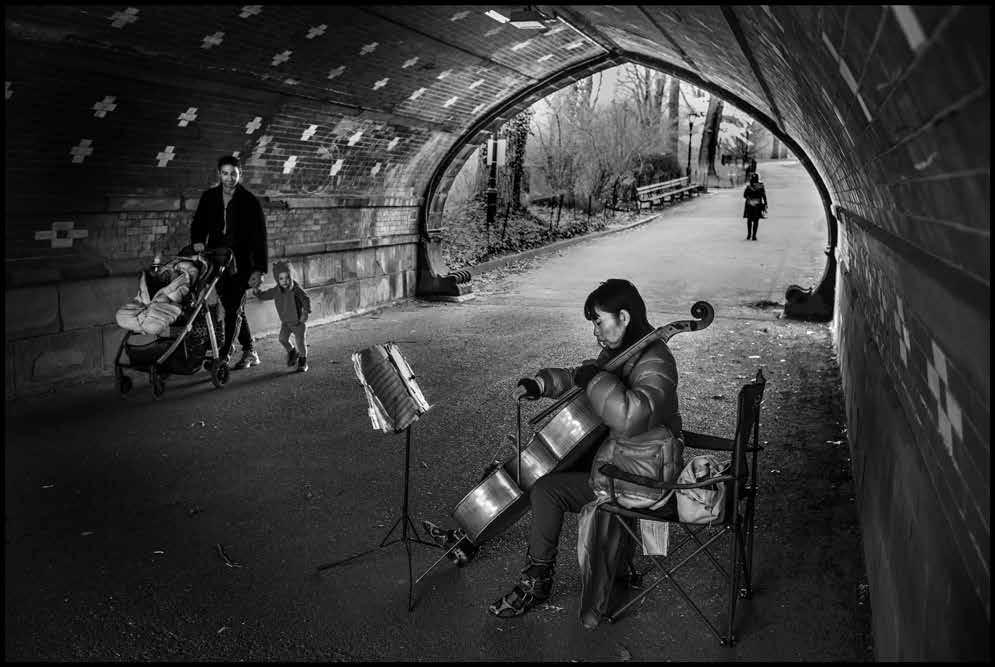

Under an underpass on the east side of Central Park, Chi, in her twenties, originally from Tokyo, played the cello. Her playing was profoundly beautiful,

and she told me that during this crisis she likes to play Bach and Tchaikovsky and music in G major. She said, “Everything must be based on life and light. I pray for peace.” My mother was a pianist, and every night of my childhood when I went to bed, I heard her playing the piano. Listening to Chi play such beautiful, life-affirming music in this hard time made me deeply miss my mother, who passed only six months ago. Leaving, I thanked Chi, and when I told her she made me think of my mother, I was a bit embarrassed when I spontaneously choked up and had a few tears. I told Chi I was sorry, and she replied to me, a stranger, “I love you, be safe.” The love she expressed was a love for our collective humanity.

When I returned home last night, the news was full of a very dire and dark prediction of the number of deaths that will take place in the next weeks and possibly months, here in New York, the U.S., and worldwide. My mind kept taking me back to the scenes I had witnessed at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens only a few days before. In the middle of this coronavirus war—almost like a world war III—there are so many heroes that I want to document to show our collective now, for the present, and the future.

April 1, 2020, diary 10 (see page 29)

I shout love and applause to all of the healthcare workers and all essential workers, in New York, Italy, France, and all over the world!

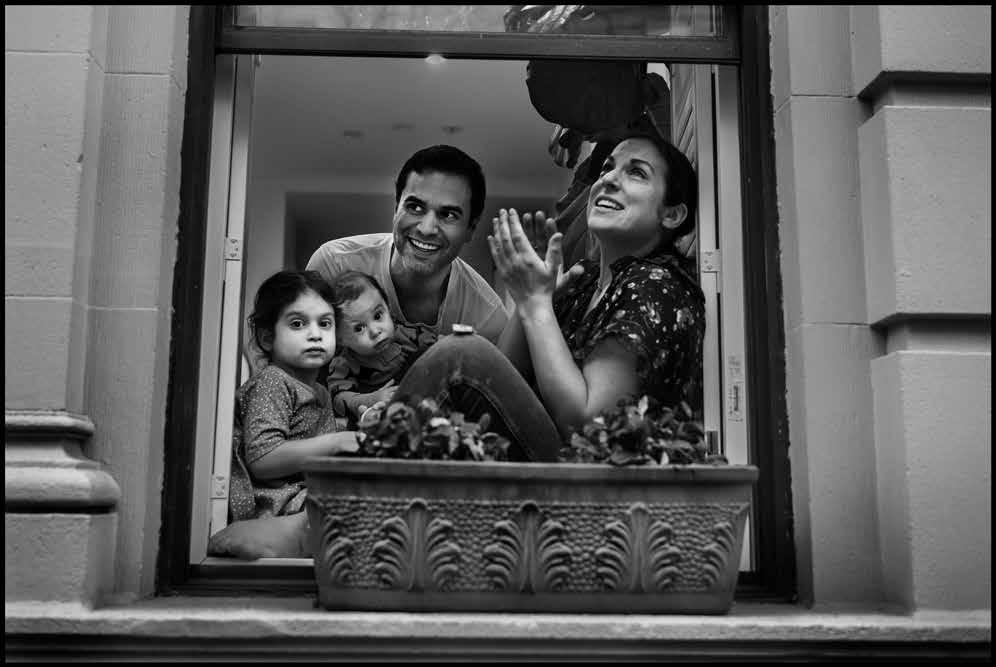

Tonight, when I went out for groceries, as I walked down my street on the Upper West Side, I saw a beautiful young family sitting in their windowsill. I stopped and introduced myself and told them I was their neighbor and asked if I could make a photograph. They asked me what I was doing, and I told them I was making a photo documentation of New York, for myself. It has been so nice to not come on strong, saying to people I work for some prominent publication, but to tell the truth: I am making photographs for myself, and for the world, of this moment affecting us all. I asked them how they were doing. Maria, the mother, told me, “Some days are hard and some not as much.” I asked the children, Isabel, 3, and Milo, 2 months old, how they were doing. Isabel told me they have learned a lot about germs, and I replied that I couldn’t imagine what that would feel like as a concern when you are just 3 years old. Maria mentioned that baby Milo could tell that they were home much more often, and that he sleeps less than usual.

As we spoke, suddenly, at the strike of 7 pm, the whole street erupted in applause and shouting of thanks to all of the healthcare and essential workers. This has now happened every night for the past five nights. I know that this is likely happening across all of the U.S. After making a few frames, I put down my camera and began to applaud and shout with all of my might as well. As Chris, the father of this family, said afterward, “This is very cathartic.”

When the applause died down, Maria asked me how I was doing. Just being asked from a person I had just met meant a lot to me. This is a different story from any I have ever covered. I too am in the middle of this one. And living alone at this time, I have a strong need to be with others—and the world. We are all in this together.

124 125

I will never forget when I was in a sports bar in New York to see the first game the New York Yankees played soon after 9/11. When a Yankee made the first score, everyone in the bar jumped up and down like I had never seen people do before—and the opposing team came out of the dugout to applaud and cheer. It didn’t make a bit of difference if the Yankees won the game that night—it was enough that they were back on the field.

It is going to take time and it will be hard, and it will change us forever. But I will tell you one thing: nothing can keep us down. And I will clap and shout that as loud as I can, every night at 7 pm, until we kick it in the teeth.

April 1, 2020, diary 11

Each night, more and more, as dark falls, and as I lie on my bed in an apartment in the Upper West Side, sirens scream out with long, echoing swirls—the sound not of police sirens—these are the sirens of a healthcare war zone, of a city that now distinguishes itself as the world’s ground zero in an invisible war on our bodies and our health.

At 7, the early evening starts with applause, with people at every window clapping and cheering for the healthcare and essential workers. And soon— too soon—as we all settle into our boxes of shelter alone, the sirens begin. It is ironic that the sirens sound almost evil—haunting, as a symbol that the enemy has struck—whereas in fact they are associated with heroes who are trained to help and save people with such courage and selflessness, like an amazing EMT I photographed, Mike Galloway, devoting his daily life to saving others.

Proust wrote about how the senses of taste and smell profoundly speak to memory; now sound provokes memories. The sirens of these days will always be associated with this moment of war, and when we hear them in the future, we will always remember this moment with sadness. But when this future memory occurs, it will be because we have survived this moment. And we will survive this moment. And several hours from now, and possibly months from now, there will be light.

April 1, 2020, diary 12 (see pages 8 and 25)

Today, as I walked along a street in the neighborhood where I’m staying, a voice called out, “Peter!” I turned to see a masked postal worker who said, “Peter, it’s Carline—I used to deliver your mail.” It has been a while, so I couldn’t believe she could remember my name, but as we spoke I discovered that her good memory is only one of her many fine qualities. Courage, decency, and kindness are clearly evident in the long list of this hero’s wonderful attributes. I asked Carline if she was scared, and she replied, “I take it one day at a time. We had two of our postal workers pass already.” I asked her if she had children and she told me she has a boy and a girl and that she and they also live with her mother, who is in her eighties. Carline drives every day four hours to and from the Poconos and is now working 10- to 12-hour shifts delivering the mail. I asked her why she does this, and she replied, “Because I feel so much love for my customers, and a sense of duty—and I need the money.”

Earlier in the day I photographed a bus driver who had pulled up to the corner of 81st and Columbus. As I was photographing him through the front windshield of his bus, he raised his hands as if to say a prayer. There are so many people who make our world go around, every day, who work hard, often for fairly low pay, who really are essential to our lives. I truly hope that when this is all over—and it will be over—that as a society, and a country, we don’t simply pay thanks to these heroes in a bourgeois sort of way, as happens so often—like thinking that thanking the troops for service is a form of patriotism even though so many people would never allow their own children to go and fight. I hope that as a society we will review our priorities and make sure that everyone has access to health care as a fundamental right and that all children have access to a good public education. If there is anything positive to emerge from this horrible war and ordeal, may it include that we learn from it that not only are we all in this together, but that to live in a world where we can all be proud, fairness and decency must be what we value most. This will require some fundamental change—but if there is one thing we know, when we come out of this, we will be fundamentally changed.

April 1, 2020, diary 12b

Today, on this Sunday, I want to look back at these past three weeks and share some images of moments that have touched my heart deeply. This visual diary is not just my diary—it is our diary. We will win this war, with courage, hope, and love. This selection is an expression of love to New York, to you, and to the world.

April 1, 2020, diary 13 (see page 49)

This morning, as the week in New York began with projections that the next two weeks will be America’s Pearl Harbor and 9/11 combined as the coronavirus will kill thousands and so many families will lose loved ones, ironically the sun beamed the beginning of a glorious spring day. There are so many difficult peculiarities in this moment. As I sat on the stoop of the building here on the Upper West Side, Gabriel, 22, a delivery person, walked by. He stopped to speak to me, and I asked him how he was making out. He told me he wasn’t scared but that his neighborhood in the Bronx is now said to be the place with possibly the most coronavirus cases in New York State. I asked him how he felt about his job and he said to me, “I love my job, and I wish that I could simply move to live in this neighborhood one day.”

Worldwide we all dream. I dream that out of this tragedy our nation, society, and our world will move to live in a world in which fairness, courage, decency, compassion, and equal opportunity for all is the basis for any notion of greatness. Everyone is part of that dream—it is our collective dream.

April 1, 2020, diary 14

In this crisis, living one day at a time, we have no compass, no direction. As the days pass, thoughts roll up and down and all around. Because I can tell how much happiness it brings others, one of the things that has brought me great pleasure when, carefully gloved and masked, I go out to photograph is when I

see people with their dogs. I have photographed many people with their dogs these past few weeks, and speaking with them about their dogs always makes for a moment of happiness, of love, of not being alone. I have also witnessed many people who are enduring this time alone. Probably never before has being alone been so alone as during this crisis. I am now alone, physically, in New York. l am lucky to have much love in my life, so I don’t feel alone and know that I am not. But my heart is with all who are alone. One thing very meaningful for me as I keep this visual diary is that I am not trying to prove any points or illustrate any ideas, and I am not working on assignment. I am simply responding to what I see and feel and everything I encounter that touches my heart. If there is one thing that feels positive now, it is this sense of freedom. This is partly my story, but it is also our story. I have taught photographic workshops around the world, and when the weeks are over, I am delighted when people have made interesting and compelling photographs. But what always makes me feel most grateful is when I have a sense that the week was a chance for someone to take stock of their life and think about what they really care about, possibly opening a path forward. This year is one in which we all will have more time than ever to do just that kind of thinking. Without a doubt, for me, aside from survival, the one thing that I care most about is feeling and sharing love! We who feel love are the most fortunate on the planet. To those who don’t have this good fortune, we must try when possible to share some of the love that we know!

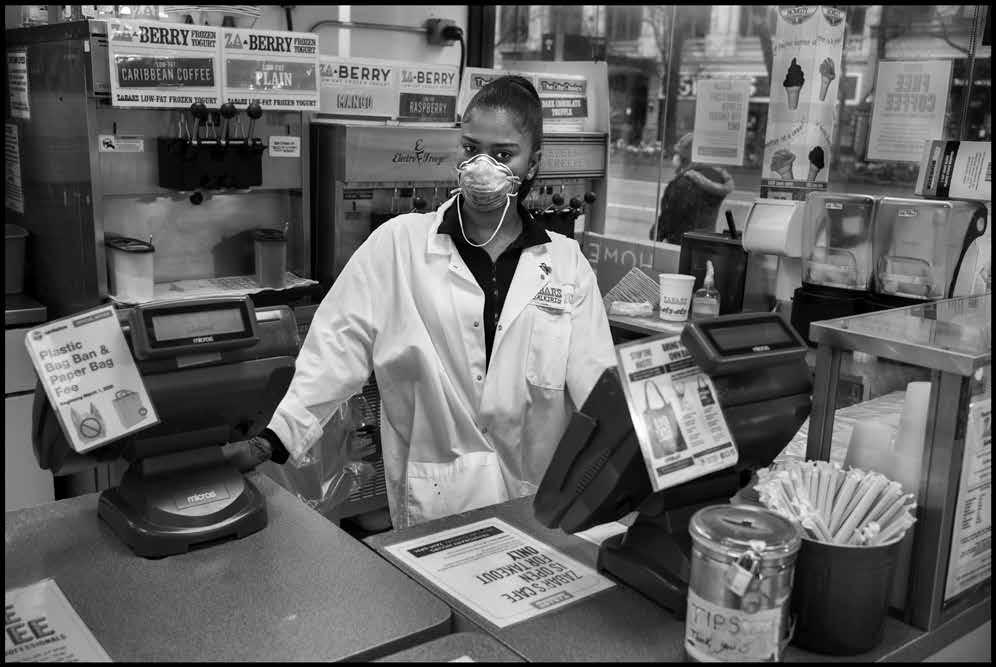

April 1, 2020, diary 15 (see page 54)

As we ride the train of life and feel alone, remember: we are one! We are all in this together. Even though things may well never be the same when this is over, we must remember the heroes of this moment. My god, what heroes—the hospital workers, postal workers, delivery men and women, police, grocery store clerks, and on and on. What a spectacle of amazing humanity. Never before have we been given such a clear view of who the heroes are. May we readjust our ideals and values and stand up and cheer and applaud the beauty of the human soul—within us all—and shown in the daily life of people who will never be recognized for their heroism. They go about their lives showing us how to live ours. What beauty, what humanity.

April 8, 2020, diary 16 (see page 42)

Some stories simply tell themselves. Yesterday I went out in the late afternoon and encountered three women at different moments, and their stories say so much about this time, heroism, courage, grace, and the realities of our society becoming more visible each day—but only when we share stories that would otherwise remain untold, invisible.

Avisia, 38, originally from Guyana, is a nanny for a Manhattan family. She lives with the family, so she doesn’t have to travel back and forth between her home and theirs. She has six children of her own and has sent them back to Guyana to stay with relatives. And so during this crisis, she looks after the children of another family, a continent away from her own children. She

explained, “I have to work—I have to support them.” Her husband is still in New York, employed as a hospital worker. She showed me a photograph of him in his protective gear at the hospital. She is able to see him only briefly every two weeks. Avisia’s situation struck me more strongly than ever how indebted we as a nation are to immigrants like Avisia for their selfless courage and grace at all times, not just this time when the leadership of this country is so fearful of immigration. Our nation was built by immigrants—how can we not be grateful for what millions of immigrants do each day to enable this nation and society to survive and be as humanly beautiful as it can be?

A bit later, walking by the reservoir in Central Park, I encountered Melissa, 39, who works in arts management. She told me that she was still working on projects already established before the crisis but feared she would soon have to file for unemployment. Melissa is very proud of her KoreanAmerican heritage. Born in the U.S. to Korean-American parents, she told me she has traveled widely and never felt fear. Melissa loves New York and told me that she hopes that this city, famous for its people who push themselves so hard, may take this time of self-care with them into the future, and that she hopes it will encourage others to be kinder to one another. Melissa volunteers several days a week at the Bowery Mission soup kitchen. I was so moved by this example of a person with reason to fear for her own survival humbly and heroically risking her life several times a week to help people severely less fortunate than herself.

As I walked home, I saw Jamie in a windowsill on an Upper West Side street nearby. Jamie, 26, is a pastry chef now unemployed because of the crisis. Wearing a welder’s dust-protection mask, she sat in the windowsill with a bottle of tequila and was on the phone using a “House Party” app for a group chat with friends in Texas, Virginia, and Maine. She told me she will likely have to move in with her parents. Laughing, she said, “They can’t deny me.” Her father works arranging supplies for the army and has been involved in equipping the Javits Center opening in New York as a temporary hospital center with beds for the surge of coronavirus patients in this city—still the epicenter of the crisis in the world. Jamie told me she feels fine as long as she stays inside and said lately she has watched many television shows. “Have you seen The Tiger King?” she asked (I have not), and she said, “You should—it’s worth it.”

In this two-hour stroll outside I encountered three personifications of courage, grace, determination, hope, kindness, and humor—all stories that would remain invisible forever if not told. There are millions of stories such as these in this moment. More than ever, before really looking and stopping to learn the stories of so many people brings out just how extraordinary these people are, people who in ordinary times we walk by every day without really noticing them. Their stories can remind us of what can be best about our common humanity. We will struggle and win this struggle always, together, with love, and attention to each other.

126 127

April 10, 2020, diary 17 (see page 57)

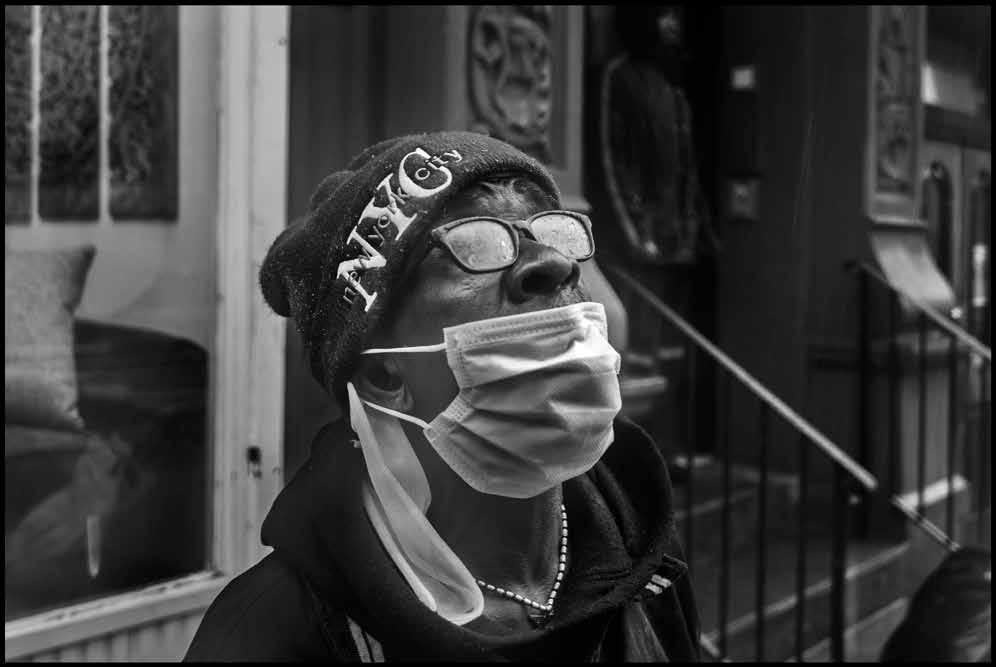

Exiting Zabar’s yesterday afternoon, the store that has essentially kept me alive with food these past three weeks, I saw a gentleman standing in line waiting to enter the store. I had my camera on my shoulder as always, and upon seeing the man, wearing a mask, I called out to him, “You are so handsome, do you mind if I make a photograph of you?” Wordlessly, he nodded in agreement and I made his photograph. I then asked him his name, and again without speaking, he made a dismissive gesture that it was not necessary to know his name. He is right. It isn’t necessary to know his name.

There are some things unavailable for purchase in any store: pride, dignity, confidence, and conviction among them. I have often encountered people who freely teach the lessons of life that we cannot learn any way other than observation. I thank this man for standing up for what he felt and in turn for all of us. God bless him.

April 11, 2020, diary 18 (see page 19)

It was just a few days ago in Central Park that I photographed Melissa, a wonderful woman, who told me about volunteering several days a week at the Bowery Mission. Since the 1870s, and continuing today, the Bowery Mission—whose neighborhood in the past came practically to define the term “skid row”—“serves homeless and hungry New Yorkers and provides services that meet their immediate needs and transforms their lives from poverty and hopelessness to hope.”

There is an epidemic of homelessness in the New York City area with more than 70,000 people without a home. Added to this reality, with the coronavirus crisis and millions of people in New York and around the U.S. now without a job or any income, the challenges of daily survival have become overwhelming.

Yesterday I witnessed a multitude of men and women, all among our society’s most vulnerable, especially during this time of the coronavirus crisis, standing in the cold, waiting to receive a bag of food at the Bowery Mission at Prince Street and the Bowery. The line of men and women standing 6 feet apart ran a long, long way down the block.

Carl, at the front of the line, told me he is “struggling a bit” and said, “I am still here, but it is stressful.” Andre, 56, lives temporarily at the Bowery Mission and was eating a hot meal inside.

Inside the Bowery Mission, I met many of the people who work on staff and also many who volunteer. Wanda, a volunteer, was cooking in the kitchen. I asked her why she does this and she told me, “I love serving humanity. I want to be a better servant today than I was yesterday. I believe this virus is a wake-up for mankind.”

John, a Bowery Mission cook, stood preparing food at a grill with a sign behind him that said, serve Like You Are serving A king

I asked Rebecca, another volunteer, who hands food to the many hungry people waiting outdoors in line, why she takes the risk to do this work, and she replied, “I want God to love New York!” Asked the same question, Kenton,

another volunteer, replied, “It’s hard to shelter in place when you don’t have a home.”

There are many very good people among us who do many good things daily, but homelessness and hunger are issues that most often are the problems of others—and those others most often are out of our thoughts and sight. This moment worldwide of the coronavirus underscores, possibly more than ever before, how much humanity is united in its common vulnerability. Will our society continue to be one of haves and have-nots, where, implicit in a system of relentless competition, there are winners and losers? Or might there be a possibility that we will reconsider ourselves as a nation, as a people, and stand up to the economic powers that be? Might we unite in a societal responsibility to everyone—even those who fall and need help and compassion? They are not losers—they are us!

More than anything else that I witnessed at the Bowery Mission, what I will remember most is what I heard from the people in need who I saw walk up and take a bag of food from heroic people like Rebecca and Kenton. In many different accents and voices, weak and strong, every single person would say the one thing they could offer back—and that was: “Thank you.” It broke my heart and leaves me writing this in tears. No one among us should ever have to say thank you for food to survive. Our human family has enough food for all—particularly in a society like the United States, where certain highrolling investors have recently made literally billions of dollars shorting the stock market as this crisis drives millions out of jobs and income.

This could be me, and this could be you. Every year at Easter lunch for years, I am the one in our family that says grace. This will be the first year without my mother, and this will be the first year I will be alone for Easter. But by myself I will say, as I say each year, “Dear lord, thank you for all that I and we have in our life, and please let us think of, and help, all those of us who have less. God bless, Amen.”

April 13, 2020, diary 19 (see page 16)

Late yesterday afternoon, I went out on Easter day to get some air, wanting to feel some daylight on my face and body. As happens often these days, I didn’t have any determination to look for anything particular with my camera; I simply always have it with me on my shoulder.

As I crossed a street corner near Broadway and 85th Street, I saw a couple walking hand in hand. Something about the way they walked together felt very happy, and while they were both wearing masks, there was a lift to their step that caught my eye. I called out to them and asked if I could make their photograph. They said yes and walked across the street toward me. I introduced myself and they told me their names, Sid and Cheryl. I asked them how old they were, and Sid told me he is 87 and Cheryl is 70. I told them they looked beautiful together and it was nice to see them holding hands. Sid said, “Well, you know, we’re newlyweds.” I asked them when they were married, and they told me six months ago. I said, “Wow, this is really a honeymoon under fire—how’s it going?” They both replied simultaneously, “We laugh and

love. We are so compatible.” Sid told me they sneak out sometimes for walks, and almost like she was sharing a wonderful secret, Cheryl said, “We dance together all of the time in the living room.” I asked them if there was any notion of life they were taking with them from these times, and Sid replied, “Live every day, because you never know what will happen after today.”

A bit later, as I walked by the Victoria’s Secret store, I saw a woman very elegantly dressed passing by. I stopped her and introduced myself and asked her name. Gretchen, she said, and she works in digital publishing. She said, “We are all in this together, and we are all struggling together. We will come out of this.” I complimented her lovely outfit, and she told me, “I’m trying to acknowledge that it’s Easter.”

A bit farther, I saw Bernardino, from Mexico, now in the U.S. for fifteen years, standing at the outdoor flower section of a local grocery store. Since he was outside, very exposed to everyone who passes by, I asked him if he was scared and he told me in Spanish, “No, I am not scared.” I asked him if he loved flowers and he told me, “I sell fruit,” and he said it with such an enthusiastic tone that it occurred to me that particularly in this moment, fruit is synonymous with life.

I returned to the place where I stay on the Upper West Side to relax for a while, and it being Easter and I was alone, I indulged in a large bowl of chocolate chip ice cream. At the strike of 7 pm, I suddenly began to hear outdoors, as I do each night now, loud applause and cheers. I picked up my camera and went outside and saw a gentleman waving a big American flag, as he does each night now during the collective 7 pm expression of gratitude for all of the healthcare and essential workers. I made a photograph and moved farther down the street and looked up and saw an elderly person high up in a window, their hand raised in a peace sign.

During these long days of lockdown it doesn’t take much for my day to be lifted—a short conversation, a moment I’ve photographed, a telephone call from a friend, even the two eggs I fry each morning all seem like large victories in this struggle. Every story I come across is also, in some way, part of my story, part of our story. Every day I am a bit scared. I take my temperature numerous times—and the smallest change in my body raises my awareness toward a fear of the dreaded enemy. I have been fortunate so far, and so very careful with mask, gloves, and distancing when I go out.

What people I meet during these times may not know is how much I need their stories and how much they give me strength and hope and courage. And on this year’s Easter day, I ate alone and didn’t have any Easter eggs—and I missed the people I love most, and my mother, who left us this past year. But the people of New York—each and every one I’ve met—gave me a beautiful gift. A gift of life. And with that, I had light.

April 14, 2020, diary 20

Every day is a new day of feelings, mood, darkness, light, and is a new chapter in this crisis, which is my life, our life. This is all new—in many ways horribly new. The beginning of each day is so important. Much of my life these past

weeks, when I am not outside, has been defined by lying alone on a bed in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, a tall window to my left, with wooden shutters in various positions of open and shut, and a small television high over the bed on a wall in front of me. I have probably spent the 80 percent of each day when I am not out lying on this bed. I usually go to bed before it is very late and most often wake up around 2 am, then again 4 am, and then again around 6:30. The last thing I do before I go to sleep is take my temperature—it is usually the first thing I do in the morning too—and several times during the day.

During the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague, Josef Koudelka photographed an empty Wenesclas Square with his forearm extended, stopping time, and the time of his watch, for then and forever. The watch of this coronavirus invasion of New York has been a digital thermometer. This time is like none I have ever known. Each day is a new day of discovery—discovery of my own emotions, discovery of the evolution of how this enemy is attacking our world, and discovery of how I and we are doing in the middle of this battle. Thinking back over the last forty years, I can remember parts of how I felt going to, being in, and returning from places like Iraq, Afghanistan, Kosovo, Rwanda, Somalia, Chechnya, Bosnia, South Africa, putsches in USSR and Russia, Tiananmen Square in China, Ground Zero on 9/11, and other places. But I’ve never known any moment quite like this.

So many times in recent years people who have attended my street photography workshops around the world have asked me, Don’t you miss photojournalism? This question has always left me baffled, because I’ve photographed in recent years more than ever before, simply on longer-term projects in a barrio of Cuba, in Paris, in a barbershop in New York, and many long-term stories elsewhere—not hard news stories, but I always reply, “Well, I don’t think I have ever left it; I feel I continue to grow as a photographer and hopefully as a person.” I also always have answered clearly that I didn’t want to have an impression of retracing my steps doing the same things I’ve done for a long time—but if there was ever another story of a 9/11 magnitude, of course I would be involved. Well, so it’s happened, but this time I am not simply a passionate and compassionate observer, I am in the middle of this ongoing conflict and the enemy is hunting everyone I know, my family, all of my friends worldwide, and it feels like it is after me each day as well. It hasn’t caught me yet, and I will continue to do my best to see that it doesn’t. But there’s something I learned a long time ago, when people would say to me, “There is no photograph worth dying for.” I always thought that this expression is an insult to my friends and colleagues who have lost their lives over time in the line of duty—because it implies that we control our world, that we get to choose. I’ve always thought it would be more appropriate to say that there are stories and photographs that are worth the risk to live for.

Every gesture, each day, is one we learn anew—and most of them are our acts of defiance, and our way of saying “You will not steal my joy, and you will not steal our life.” We will win this war. And together, with you reading this, with these rambling words, we move forward in time, with love, and take

128 129

ourselves toward beautiful light, while the enemy disappears slowly into the shadows. We shall overcome. With love.

April 14, 2020, diary 21

Worldwide, it continues—when the clock strikes 7 pm every evening, people are united in their expression of gratitude deep from the heart and from every cell of the body. Cheers to the many, many, many heroes risking their lives to save ours!

Tonight, again at 7 pm on the dot, an explosion of applause, shouting, and yelling began. People come out of their doorways, people lean out windows, cars honk their horns, and Kimberly, a woman I photographed, came down from her apartment to stand in the street this one night to have a new point of view. Kim is a pastry chef and a flight attendant, out of work now. Originally from a small farm town in Minnesota she has lived in New York for the past thirty-one years. She told me, “But, I’m a New Yorker now! It’s in my blood! What we are doing here—thanking the healthcare and essential workers—this is a simple gesture anyone can do. I feel like it is my civic duty to stay inside. I’m not doing anything, and this makes me feel like I am doing something. I have friends that have friends who are healthcare workers and they say this helps them and encourages them. I usually clap from the window—but today I wanted to see what it was like downstairs.” Kim also lived through 9/11 in New York and did volunteer work then.

Kim told me that a lot of days she goes through ups and downs. I do too. We all do. But when the day ends, and we all come out and shout and clap, our day ends with an expression of thanks, and gratitude, and a feeling of victory! And this gives strength to approach the night while we wait for the light of tomorrow.

April 16, 2020, diary 22 (see pages 26 and 59)

In the war with the coronavirus, as the world seeks an antiviral drug to fight this enemy, a nation may also take an opportunity to find a cure for its soul, to heal the divisiveness in its most important values.

Yesterday afternoon, on the outskirts of a field hospital created to treat Covid-19 patients from the Mount Sinai hospital system, I met Meredith, 24. She is a master’s student at Mount Sinai studying biomedical science and has volunteered as part of a student workforce. She has been volunteering since the crisis started. She told me, “This feels surreal, like a bad movie. My family is in upstate New York and they are definitely nervous. This scares a lot of people away, but it makes me want to be a part of it. I feel like there is not enough I can do. It’s craziness. I’m doing the PPE. The first call I got as an assignment was for body bags. That was crazy. I work until 11 pm every day. When I go home, I feel sad. It doesn’t feel real. I live alone. Most of my friends are in health care. The nightly applause is really moving—it makes it feel worth it. There are little girls across from my building where I live who bang on pots and pans. What frustrates me most are the people that aren’t wearing masks and staying home.”

Earlier, as an ambulance was pulling out of the tent hospital area, I met Karolyne, an EMT, originally from Brazil. She and her colleague had just delivered to the field hospital a Covid-19 patient from Queens. She told me most of the calls her ambulance was responding to were for Covid-19 patients. She looked out at this tent field hospital in the middle of an American city and said, “This looks like a war scenario.” I asked her if she was scared and she replied, “I just do my job.”

Another nursing assistant, Angela, 54, originally from Baku in Azerbaijan, living twenty-six years in the United States, crossed my path as she was leaving her shift at Mount Sinai Hospital, where she works with Covid-19 patients in intervention radiology. She sees at least ten coronavirus patients every day and has been doing this since the beginning of the crisis. “I’m scared of course. I live in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. I live with my family and I work the night shift from 11 pm to 7 am. This is my job and I have three kids. Everyone in my family is in the medical field. I don’t feel good. My wish is that everybody on this planet will be able to return home from hospitals. Everyone. In my work with the coronavirus patients, I clean them, feed them, and at night I sit and watch them. I am very sad about this problem.”

When I started my day, I went out to get a coffee at a local store and came across Alex, 52, from Brooklyn, who works for Go Fund and cleans the streets of New York and takes care of picking up the trash from the trash bins on city street corners. I watched him work and saw the care and concentration in his efforts. It reminded me of the time when I was 10 years old and my father pointed out to me a gentleman cleaning the windows of a diner. My father said to me, “Peter, watch that man work. He wants to be the best window washer in the world, and if you go forward and do anything and everything you do in life as well as that man does his job, you will be okay.”

A bit farther I encountered Roger, 26. A traffic policeman. We spoke and he told me, “Not much opportunity for me to do most anything. I guess my presence helps others to watch their p’s and q’s. I’m not a hero, just another human being. Humbly doing my best. Live with my mom. My mom is always telling me to be careful. I get why she does it. She’s a mom. I see some people being kinder these days. In situations like this you see what a person is all about. I try to see the best in people. I’m seeing that a little bit more right now.”

Llewelyn was washing the glass door of the apartment complex where he is the super. “My name has Welsh origin, but my origins are Dominican. I’m the super. Cool profession. I wipe down every day the door handles, elevator buttons, anything that has been touched. I’ve been okay so far. I’ve worked here for two years. I live here now with my daughter, son, and wife.”

Late in the day, I came across two women, Jocelyn and Dorothy, sitting a safe distance apart on a park bench. They’ve been friends for sixty years. They live near each other on the Upper West Side. They told me they call their meetings outside on the bench “a bench date.” I asked how they were making it and Jocelyn responded, “It’s rather bizarre to say the least.” Dorothy told me that as a result of this crisis, “We have to get a new system where the people come first. We had a whole civil rights movement in my time—what went wrong?

Cuomo says he is surprised that the fatality rate is higher with people of color. He said we have to study this. You don’t have to study anything—just call me.”

At the end of this day, at 7 pm, like every other day, on the street where I stay, people came to every window and many came out on front stoops to shout and applaud, sing, and thank, all of the people, like Meredith, Angela, Karolyne, Alex, Llewelyn, and millions of essential workers all over America and the world, who offer us something we can all be proud of—our common, beautiful, loving, hardworking, decent, humanity, offering us hope.

April 17, 2020, diary 23 (see page 24)

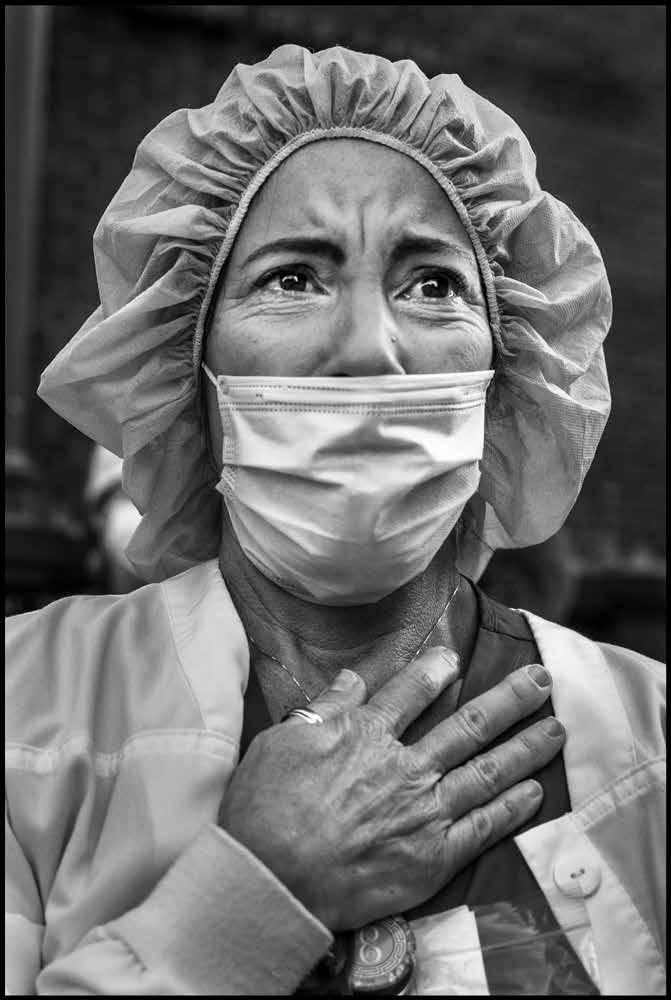

More than 12,000 people have now died from coronavirus in New York. I understand the importance of statistics, particularly with this crisis, how the numbers offer possibilities for scientists and specialists and policy makers to have an overview of the evolution of this crisis in the effort to win this war. And yet I have always felt that statistics remove the public from looking into the human face and emotion of what war is really like—and this is a war, possibly the most important war of most of our lifetimes. I recall during the Gulf War in 1991 how the U.S. military would give daily press briefings during the air war, and viewers would see on television statistics of Iraqi dead and occasionally see aerial photographs of bombs exploding—something akin to a Nintendo game. But what the public was not seeing was that behind each statistic was a human being, a dead human being with a wife, a family, parents, and a community, and it would leave the viewer without any sense of emotion regarding the loss of human life. When I covered the ground war of the Gulf War, I saw firsthand what this destruction looked like, and I was determined to bring back a set of photographs that would convey the true cost of war and the human emotion connected to human loss. I published a portfolio called The Unseen Gulf War I have always thought this was an important record of what that war really looked like.

Since the beginning of this crisis, I have gone out most every day to photograph and document, the human face of this war on the world, and on New York City—a war waged by an invisible enemy smaller than a pinhead but as lethal as major bomb attack. Today I looked into the eyes of true heroes— the healthcare workers of Mount Sinai Hospital, many of whom had lined up outdoors, waiting to take a noon pizza break, a short respite from their time of battle, inside one of the major New York Hospitals fighting the pandemic. In photographing the plight of refugees worldwide, I’ve always thought our world would be so much better if every world leader was obliged to spend at least one week living in a refugee camp before taking power. One way or the other, we will win—because our souls are not governed by one person but uplifted by our collective power of humanity, which the people I have seen every day in the last month here in New York show us always.

April 17, 2020, diary 24

I am not ashamed to say that every day, in the middle of this war, I know fear. Fear comes from the drive for survival. I imagine that much of the world is

living with an omnipresent fear every day—for many this is a first extended encounter with war. I am hoping we can collectively learn from it. There is probably no more powerful inspiration to become more human than when we recognize and accept our vulnerability and embrace this as part of what makes us beautifully human. Clearly love emerges as what is most important in a moment like this. Nothing is more important to any of us than the survival of the people we love—our family, our friends, our community, and our world. We need to change some things! How are we to survive as a society with such great disparity of wealth, with so many lacking health care, and so many of our children deprived of excellent free public education? Why should we live like that? Who are the real heroes? The CEO of a company who makes $35 million a year while the package delivery person ensures our survival by delivering food works for an hourly wage barely sustainable? When we emerge from this battle, as we will, we must not return to a world where the rich and powerful continually lecture us about patriotism and demand everyone stand for the flag and support the status quo. Fundamental readjustments are required. There can be glory in this. It doesn’t mean we have to live in an us-against-them world. The challenge will be to make clear that everyone must be able to live better. There are no losers in this change. And, as a society, we will know less fear. This moment of fear for survival underling our collective vulnerability will have made us stronger. This will be our victory, with glory.

April 19, 2020, diary 25 (see pages 22, 44, and 62)

My world and existence this past month are both reduced and expanded to little—and much. Each day I wake up grateful to meet the day feeling healthy. I make coffee, fry two eggs (another victorious morning!), shower and dress, don my mask, put several pairs of gloves in my pockets, and pick up my Leica M10 camera (one of my best friends), and walk out the door. Suddenly, my existence exits the confines of a bedroom, living room, bathroom, and kitchen (with a crucial tall window next to the bed so I am greeted each morning with either beautiful sunshine like today, or grayness and rain, like yesterday), and I walk out into the city of New York—continuing to be the epicenter of the world’s coronavirus crisis.

For the past month the world’s most dynamic city has been a ghost town. Yesterday, I went to Grand Central Station, household name symbolizing the bustle of the city that never sleeps. I walked into the grand concourse, one of the busiest commuter train stations in the world—and found it almost completely empty. This emptiness became immediately synonymous with being alone. This feeling was bittersweet. In such a grand expanse, one feels diminished, small, insignificant—and yet I marveled at the feeling of having this tremendous palace of transit all to oneself.

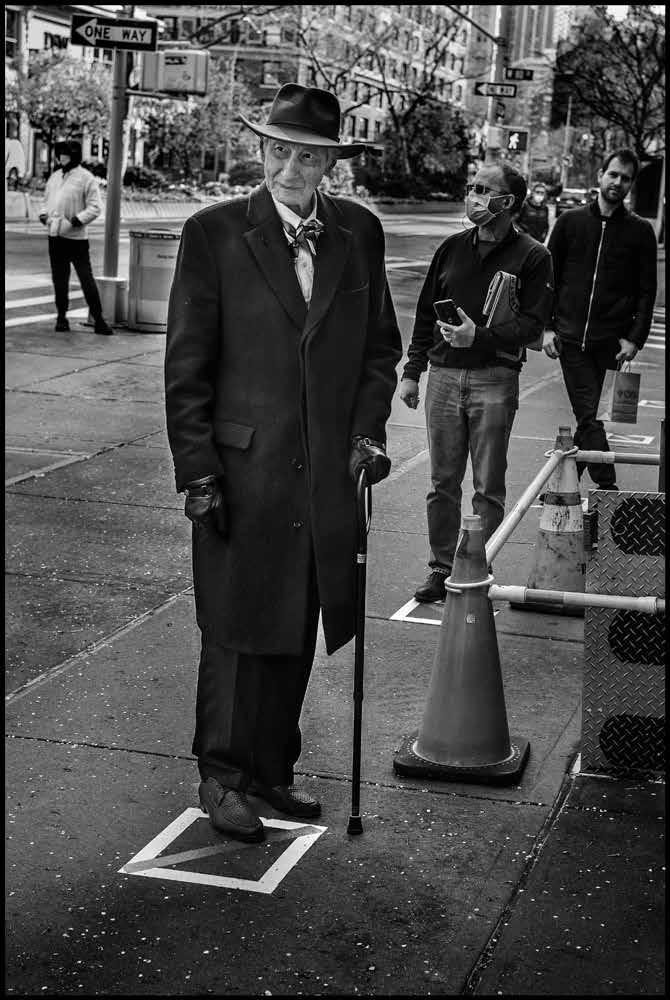

I caught sight of a lone man walking with a cane across the main hall. Very often, when I photograph, I don’t make just one photograph—particularly if it is of a person—I like to do what I call “stay with it, work a situation.” Life evolves every second with new gestures, body language, expression, and often gets more interesting. After making an initial photograph of this elderly man, I

130 131

introduced myself. His name was Richard and he said he lived on 23rd Street and was heading toward Larchmont, New York. I followed him as he walked to his train, literally the only passenger on this commuter train. He sat at the front of the train and told me he likes to sit there because it feels safer. Richard worked for thirty years in maintenance for the New York Board of Education. He said, “I grew up during the Depression and remember World War I I. This moment we are living through is an enormous economic catastrophe. Poor people are in big trouble. I recall in my childhood getting ration tickets for food. What we are living through now will be worse. Society has grown larger and more complex.” I made a small essay of photographs of Richard. He seemed to me a symbol of so much about this moment. We are all in this together—yes—and at the same time also very much alone. We embrace every phone call with our loved ones, every conversation with a neighbor, every encounter with a person we photograph, because we know that if it is our destiny to make that dreaded trip to the hospital, we will be alone.

On the train tracks of Richard’s train, I encountered Alex, a train conductor who works for Metro North. “Our families are scared for us. We’ve had some sick and some deaths among our colleagues. Stay safe, hug the ones you love, and follow the guidelines—that is all we can do.”

A bit later, I met another train conductor, Jason, 38. He told me, “I haven’t had much experience in life—but there is nothing I can compare this with. My family is scared.” I told him he was a hero, and he shook his head, almost in disgust—I think both out of a sense of humility and the realization that he was doing this work out of a sense of duty and obligation, and out of economic necessity. He is, though, very much a hero.

At the information booth in the center of the main hall of the station sat “D.” She told me she is very scared of her commute to work an hour and a half each way from and to New Jersey. She says she feels safe inside the bubble of her information booth.

Larry, 57, a customer service worker for Metro North with twenty-eight years on the job, stood alone in the main hall. He travels each day four hours from and back to Connecticut for his job. “It’s been a ghost town since the beginning of this. I ride like I always do. The cleaners are taking extra precautions to keep the trains safe. I do hear rumors some of the conductors have gotten sick.”

A young couple, John and Megan, stood in the main hall getting their photograph made holding an “I Love New York” T-shirt. I asked them why they had come to do this. They explained that they were expecting a baby in September and they wanted to have a record to show what the world looked like before the baby is born.

Before returning home, I stopped by a fire station on West 10th Street. Josh, 39, a fireman, was sitting in front of a fire truck. “It’s tough—we’re working a lot. We’ll get through it. Everyone is doing their part. We go on a lot of EMS calls now—we always have this thing in the back of our head. My wife is more nervous when I go to work. It sucks that she is furloughed from work, but I’m glad she is not essential.” When asked why he became a fireman, he replied, “I used to work EMS—it is a natural progression. I like to be of public service.

There is definitely an adrenaline rush to it. Unfortunately, that usually means someone else is in a shitty situation. Our biggest fear on the job is being trapped in a fire or hearing little kids trapped in an apartment. Since the beginning of this crisis I’m probably a little more aware of my surroundings. There are firemen getting sick around the job.”

I wake up on this Sunday morning to beautiful sunshine out the window. I know I will return today to photograph more hospital workers from Mount Sinai Hospital. I wrote earlier of the notion of being alone. One can say you are not alone—and this is true, I am not alone—in that we are all in this together. But the truth is more complex—we are alone, and we are together. What is important is spirit, hope, and love. The human face of New York that I witness each day provides me with hope and courage. My heart and the hearts of so many people I care about all over the world let me know and feel love.

April 19, 2020, diary 26 (see pages 48, 51, and 58)

Through many years of walking with a camera I have learned a few things: one, that things never happen exactly as expected, and two, that if you just stay open to receiving and responding to them, most often the things that do happen, humanly and visually, are much more interesting than anything you could predict or foresee. Yesterday, almost exactly one month since the beginning of New York’s lockdown—a major change in my life and all of our lives—I decided to return to Mount Sinai Hospital to meet and speak to more hospital workers bravely risking their lives to save ours.

I met George, Anna, Herbert, Cleo, Clara, Mariana, Richard, Mike, Bella, Kristen, Cameron, Rachel, Julian, Angel, Avic, Pam, Teri, Andre, Ray, and Scott. I mention all of these names for a reason—it is exactly why I wake up each day during this crisis and at some risk to my own health go out to photograph and document this moment. New York City is a city of human beings, each with a name, each with an age, each with a life experience, each with a family that cares about them—and they all, like each of us, are much more important than statistics, numbers, peaks, flattened curves, and definitely politics—they are the heart and soul of this moment.

If there is one overriding theme that dominates my motivation to pick up a camera and to memorialize, for now, and for all time, it is that I am driven to make a declaration with my life and existence, and, more importantly, driven to honor the people I encounter, and hence to honor the gift of life itself. I have traveled the world for almost fifty years now, and through all I have seen— many moments that challenge the compass of my heart and soul—I remain resolutely hopeful and optimistic. Never has my hope been stronger than after this past month of looking into the eyes and faces of so many people in New York City—every single one worried and anxious—and yet so many standing up every day to show us all what can be best about ourselves. Not once have I witnessed one single person who asks for thanks, gratitude, or particular appreciation. Every day I hear people say “I have a job to do,” “a sense of duty,” “we are all in this together,” “one day at a time,” “thank you,” “how are you doing,” “be safe and take care of yourself.”

In the coming days I will be working on a video montage of all of the photographs I have made and the stories I have come across this past month. This will be my expression of the human face of the coronavirus crisis in New York City. I look forward to sharing this with the world soon and will strive with all of my ability and heart to honor the so many people who have honored me, and us. This will be their story, and more importantly it will be our story. We can all stand up and be proud—we are one, and together we will overcome.

April 19, 2020, diary 27

Let’s show the healthcare workers of the world our love! Everywhere in the world, at this moment—it is 7 pm. Let’s let them know worldwide, we love them! They are fighting for us and together with them we will win this war!

April 19, 2020, diary 29 (see page 41)

I boarded the 10:30 Staten Island Ferry today. Immediately I saw a couple sitting, holding hands, on a lower deck. I made a few photographs and introduced myself. The couple told me they were from West Virginia. Rachelle is a traveling nurse and has quit her job back home to come work in an ER at a hospital in Queens. Rob, her boyfriend, is a welder back in West Virginia and this is his first trip to New York. I mentioned that the the best view of the Statue of Liberty they’d made this trip to see would be on the upper deck. We went upstairs together, and after making a few photographs, I left the couple to themselves. A while later, I lifted my camera to make this photograph of a tender moment between this very brave and kind couple. It is a photograph that will always be very meaningful to me. On the return trip to Manhattan we spoke further.

This moment encapsulates so much about the humanity of this moment of war in which we all find ourselves. Rachelle served as a nurse in Afghanistan. Upon return, she was working as an ER nurse back home at a hospital near Parkersburg, West Virginia. When the coronavirus crisis hit the United States and New York the hardest, she decided to quit her job and come to New York. “I spent a year in Afghanistan with the army,” she said. “I just thought it was my duty to come here and help out again—this time wearing a different uniform. I expected the worst. Everyone is so nice—I just wanted to help out. I’ve been here a week. We had a day off and I wanted Rob to see the sights. I’ll stay until July. If I am needed more, I’ll stay longer.” I asked Rob how he felt about her clearly very dangerous work in a Covid ward section of a hospital in Queens—one of the hardest hit areas in the world. Rob replied, “Honestly, I worry—she’s smart—she takes care of herself. I’m proud. It’s her heart’s calling—I can’t deny her that.” Rachelle added, “It’s catching people left and right—it doesn’t discriminate. I’m less scared here because here you know everyone has it that comes in—in the little town where I worked back home, people come in complaining of a chest pain—and then later you discover they have Covid.”

Rachelle has four children and Rob has two. They told me they had been together three and a half years until recently when they went through a five-month breakup. Since the beginning of this crisis, they have gotten back together, and both hope this time it will be forever—“this has brought us back closer.” Rachelle told me that this experience is actually not much different than her time in Afghanistan. In each place the concern is what you can’t know—“the not knowing.” In both places the priority is maintaining safety. I asked her how the virus was affecting the patients she sees. “Everybody is taking it differently. I’m just here to make them feel better,” she explained. Rob added, “This might be what humanity needed. It’s sad to say that—but when it’s all over, hopefully we will realize we are all together.” Rachelle added, “Now when I go to McDonald’s or the grocery store, I thank everybody for their service.”

My heart sang to see this couple together, in love, and to witness two human beings with such grace and courage. In our long conversation as the ferry brought us back to Manhattan, I had the impression of having just met some wonderful new friends.

In middle of this tragic war, the world has lost hundreds of thousands of people who have died from the virus, and in the United States alone, almost as many have died in a few short months as the number of U.S. soldiers killed during the more than ten years of the Vietnam War.