FOR ALL PEOPLE LIVING WITH BRONCHIECTASIS (BE). YOU DESERVE TO BE SEEN.

Introduction

The book you are holding is about more than bronchiectasis (BE). It’s about seeing the whole person behind the condition. It’s about helping you feel seen beyond having a disease that is too common to be considered rare, and too rare to be a household name.

BE is a chronic lung condition that gets worse over time and affects more than your breathing. It can impact your sense of self and how others perceive you. It can feel like living in a world where others no longer truly see or understand you.

At Insmed, we champion those who are overlooked and underserved, and we are dedicated to supporting people with BE along their journey. In everything we do, we put patients first.

As you read these stories from Jodi, Allison, Amber, and Edna—each written in their own unique voice—we think that you may see your own experiences in these 4 individuals: that their losses and triumphs are similar to your own; that their desire to be seen, not just apart from their BE, but in spite of it, is an inspiration for you to tell your story, not just suffer through it.

If you have struggled to breathe and felt afraid, we understand you. If your cough has introduced you before you even say your name, we hear you. If you have felt unseen because of your BE, we see you. You are not alone.

With you, Insmed

Unforeseen circumstances

JODI WAS DIAGNOSED WITH BE IN 2019

SEEING WHO I REALLY AM

The daily struggle with breath, self-perception, and being truly seen by others

Even with my eyes closed I can tell it’s the early morning and still dark. I’m guessing it’s a good 30 minutes before my alarm sounds. As I lie in bed, I’m focused on 2 things: my nose cannula resting on my upper lip and my breathing. I inhale. It’s a quick, sputtering pant with a wet rattle beginning to end.

My system for monitoring my breath is quite simple. If I inhale and there’s no tightness, no hard-to-describe but distinct feeling like something is lacking, it’s a good breath.

That last breath was an iffy one.

6:00 AM

It’s 6:00 and I have my doctor’s appointment at 10:00. Between nebulizing, nasal rinses, allergy sprays, getting cleaned up, and eating breakfast, I know I will have to hustle. I make my way downstairs into the family room, past the couch where my 2 dogs Bindi and Jasper are still sleeping, and over to my nebulizer. I keep it in the perfect place, a corner between the wall and my computer desk, still within easy reach but hidden away so my eyes can glaze over that area. I inhale again. Hmm, that breath was better.

With bronchiectasis (BE), it’s hard not to think about breathing every minute of every day. But I don’t like thinking about it—in fact, I hate thinking about it. There’s nothing I can do about it, though, so I tuck those thoughts away, move my nose cannula, flip my nebulizer on, and inhale through the mask. Yes, better. My breathing is better now.

It feels like a confession to say I kept BE a secret. But that’s what I did, especially in the beginning. I didn’t want people to know, because no one really understands the whole thing. Like when we went to restaurants and there was a short walk from the car to the door. The hostess would be the first to notice I couldn’t catch my breath, and as I huffed and puffed on the walk to the table, I could tell everyone’s eyes were on me. They were probably thinking, “Oh, she must have been a smoker.” And yes, I was. But whether that caused my BE or not, my doctor doesn’t know.

7:00 AM

It’s 7:00. Nebulizer done, nasal rinse done, allergy spray done. I drink a cup of coffee at my computer and scroll through the internet. More than an hour goes by as I sit there, catching my breath and waiting for everything to kick in before I take my pills and maneuver myself and my oxygen tank back upstairs. I make it all the way to the bathroom before I realize I forgot to use my inhaler. I sigh—I’ll just have to do it later.

For bathing, I use a neat little black stool to sit down while I shower. I bring my oxygen in and have everything on the ledge in front of me, my terrycloth bathrobe hanging just outside the sliding glass door, ready and waiting.

Before I was on oxygen, I had a slew of tricks for making it seem like I wasn’t out of breath, and I used them all when I was going out. I picked restaurants with lots of parking spots close to the entrance and always arrived ahead of time so I could walk in nice and slow. And forget places in the city—I couldn’t do that.

8:04 AM

I look at the clock. It’s already past 8:00 and I’m running behind.

I get dressed and head back downstairs for the second time this morning, toward the sound of Suzie, one of my cats, meowing for her breakfast. I have 6 pets, not counting the outdoor ones. I have this abnormal love of animals and must be surrounded by them constantly—so much so that I made a career out of it.

I used to go to people’s homes and play with their animals for an hour or so—it was just a dream come true. I couldn’t believe people paid me to come and love their animals. Then my health got bad, right before the pandemic. The one unexpected silver lining of COVID-19 was I could bow out of my pet-sitter gig gracefully without saying I couldn’t breathe.

I still miss it, though. When I remember walking up to a client’s front door and knowing Roxy or Nilla was just on the other side, excitedly waiting to greet me, my heart aches just a little. It’s an ache that hits me at the strangest times, like now, as I pull a bowl of fruit out of the fridge and move one of my grandkids’ sippy cups over so I can sit down at the kitchen table and eat. I inhale. It’s a shallow, petty thing, and I need to do a few more in quick succession to get enough air.

COVID-19 happened right around the time of the stair incident. My husband and I were watching the grandkids and he went out to get some pizzas. Well, during that time my grandson woke up from his nap. I went upstairs to get him but didn’t have the breath to carry him back down.

I must have stared at those steps for a good 10 minutes, my grandson squirming and fussy in my arms, before I decided I was going to have to scoot down them on my butt. There was no other way. I held my grandson tight in my lap, and all these feelings swelled up as we went down, down, down.

That broke something inside of me. I realized I couldn’t do this. Any of this. I couldn’t get up and bring my grandkids downstairs after their nap. I couldn’t keep up, and to me that meant I wasn’t a good grandmother, and I should be a good grandmother.

8:50 AM

“Ready to go?” my husband says, and I startle a little. I turn around and see he’s poking his head in through the mudroom door. He’s holding the door open wide enough that I can see the driveway behind him, where the car’s already running.

I close my eyes and inhale, then open them and slowly push myself out of my chair. My husband moves to help me, but I wave him away. Some things I can still do myself and I want to—although I do let him help maneuver my oxygen tank out the mudroom door, down the drive, and finally up into the car. It’s an ordeal, and I only think about my breathing every single second.

My husband climbs in on the driver’s side, and as I buckle my seatbelt, I inhale. Another iffy one. I reach into my purse and pull out a rescue inhaler for my chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). I take a couple of puffs, and when I exhale, I swear I can feel it go way, way down into my lungs, making them expansive-like. There’s nothing ever quite like taking that first breath after hours of feeling like no matter how hard you try, you can never really get enough air. I inhale, and ooh, that’s a good one.

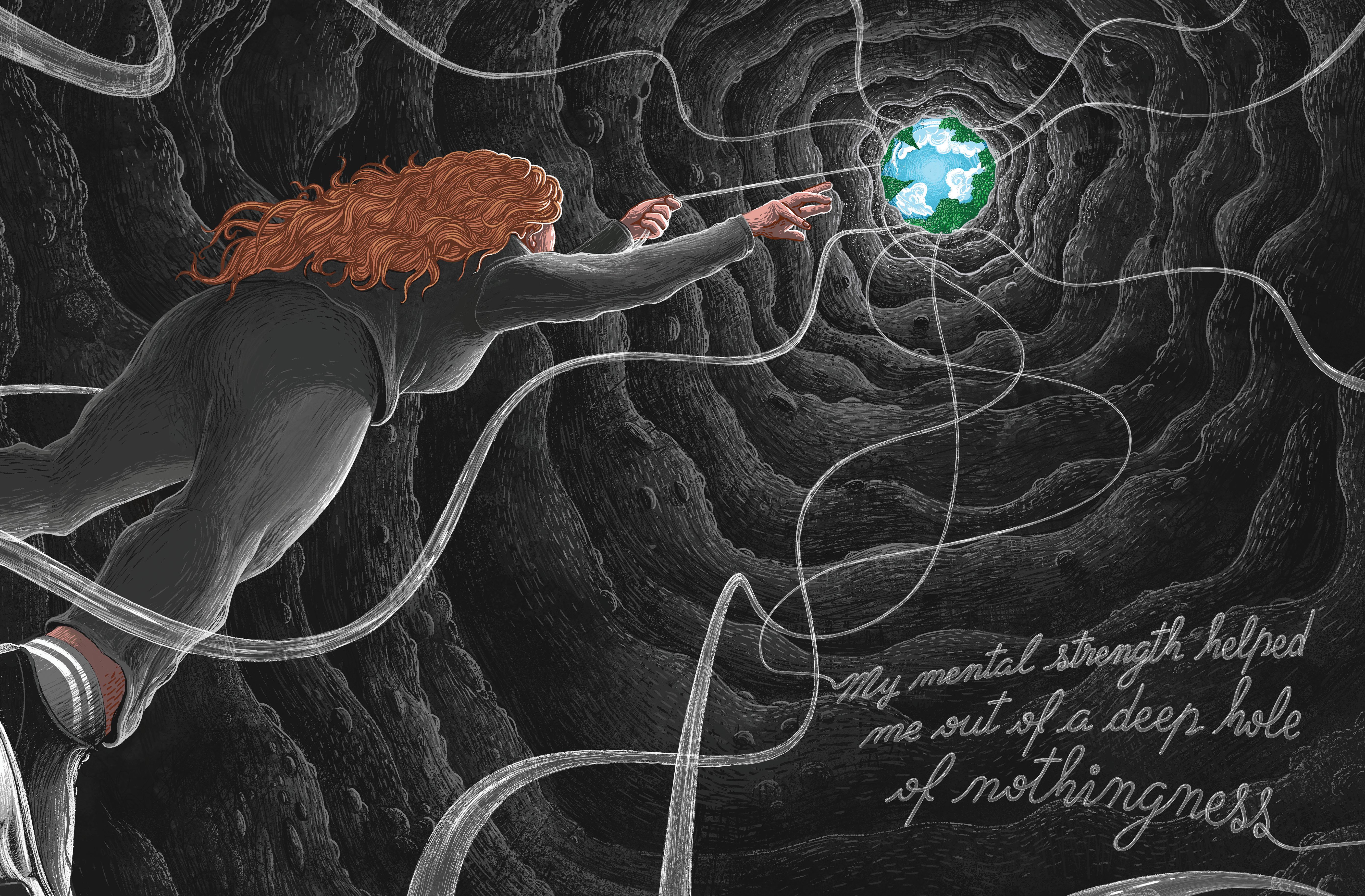

I can remember a time when breathing wasn’t so hard, but these days, the memory has more and more hazy edges. The first time a deep hole of nothingness swallowed me? I think that will forever stay sharp. I don’t think it was the constant struggle to breathe, the wide-eyed stares from kids eyeing my oxygen tank at the grocery checkout, or the large-scale changes my worsening health forced on me that caused the anxiety and depression. It was that all those things happened at once.

I hit a point where I was done. I was always the strong one when the going got tough and everyone was falling apart. But I didn’t feel so strong anymore, and I’d had enough. I didn’t want to accept this new way of living, and in fact, I couldn’t. The one thing people who haven’t been depressed get wrong is that they think depression means you have bad feelings all the time. But that isn’t always the case. That wasn’t me. I had trouble feeling anything at all. That’s when I got the call.

I remember my phone ringing, and when I saw it was the insurance company, all I could think was, “Now what?” I picked up and this woman said, “We’re offering free counseling over the phone. Would you like to participate?” And you know what, sometimes things really do happen exactly like in the movies. What I mean by that is, that call was exactly what I needed when I needed it, and the twice-weekly calls that followed with Ericka, my counselor, changed my life.

This weaker, older version of me had mental strength my younger self never had—and that was worth something.

9:25 AM

We’re 15 minutes out from the doctor’s office, and as we merge onto the highway and pick up speed, I can’t help but think how the best thing that program taught me was something I’d never bothered to learn: how to keep your eyes on the present.

When I was young and healthy, I multitasked—and I was good at it, too. But focusing on everything at once meant I was focusing on too much at once. Counseling helped me be mindful of only 1 thing at a time. True clarity hit me later, when I realized all the mindfulness and living-in-the-present exercises were just tools to help me see I deserved more than my own punishing attitude and less of the worry provoked by others’ opinions. I wasn’t physically strong anymore, and there was no changing that. But this weaker, older version of me had mental strength my younger self never had— and that was worth something.

There are still days when I can feel myself falling into that deep hole. Sometimes I want to be there. And my anxiety...well, I haven’t let that go completely either. I doubt I ever will. Even now, as we pull into the doctor’s office, I can feel nervousness crawl up my neck, then down into my hands. Will the waiting room be packed? Will there be a chair for me? What if someone steps on my oxygen line? What if people stare?

9:54 AM

We get inside, check in, and not 2 minutes after I sit down we’re called up to the front desk. What follows is a constant run back and forth that my husband thankfully handles.

“Bring us your cards,” then, “Come get your cards.” A minute later, “There’s a form I need you to sign.” A young boy holding his mother’s hand stares at my nose cannula. I smile, and when he asks what it is, I tell him what I tell my grandson: Some people need glasses to help with their eyes, and some people need this to help with their breathing.

A nurse calls us back and I move down the hall, ever careful of my oxygen line. We settle into the brightly lit room, and a moment later the doctor softly knocks and enters. He sits and swivels towards me on his little stool to ask, “How’s your breathing lately?” I can’t respond right away. I’m still recovering from the walk down the hall.

By the time we’re finished, I’m exhausted. My husband can tell and places a gentle hand on my back. Together, we navigate out through the waiting room, and he helps me up into the car. I love that I don’t have to ask for help. Even if these days I’m better at asking, I still hate it. Every so often, I get annoyed about it, and when that happens, I'll turn a little teary and I’ll tell my husband it’s not fair. His face will droop a little then and he’ll pat my hand. “Yeah, it’s not fair.”

I think how unfair everything is as I climb into the car now, but unlike those other times, I let it go. I don’t say anything but thank you.

With BE, I’ve found you can handle it, or you can fall apart. I’m choosing to handle it. I’m walking my daughter down the aisle in October, and I’ll be doing it with my oxygen tank. A whole crowd of people who don’t know how bad my breathing really is will see the truth and think, “Just another former smoker.” I haven’t quite made my peace with it yet, but I will try. That’s its own kind of strength, I think. To keep trying.

When my husband pulls out of the parking lot, the sun hits my car window at a certain slant, and for just a moment, I make eye contact with my reflection. Together we inhale. Exhale.

That breath felt good. ■

Jodi discovered her inner strength, but there’s more to see.

Exploring the complexities of obtaining medical oxygen

Even though it’s not for quite some time, Jodi is already thinking about her daughter’s wedding—specifically, that long, long walk down the aisle. The only way she’ll manage it is with her oxygen tank, a piece of medical equipment that’s becoming more difficult to get into the hands of patients.

According to Medicare, oxygen and oxygen equipment are categorized as something known as durable medical equipment (DME). DME is defined as medical equipment that can be repeatedly used within the home for up to 3 years. Items like blood sugar meters and test strips, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines, nebulizers and nebulizer medications, and wheelchairs all meet the criteria of DME. While Medicare pays for different kinds of DME in different ways depending on the type of DME, patients may need to either rent or buy their equipment. However, Medicare will only cover DME if the patient’s doctor and DME suppliers meet the strict standards to enroll, and remain enrolled, in Medicare.

“...dig just beneath the surface, and a complicated web of red tape makes obtaining DME that much more challenging...”

This puts the onus on patients to ensure that their prescribing doctor and DME supplier are enrolled in Medicare. Additionally, oxygen and other DME are subject to Medicare’s Competitive Bidding Program (CBP). The CBP was established in 2011 with the goal of saving Medicare, and its patients, money. The process is exactly what the name sounds like: Suppliers submit bids, and Medicare then uses these bids to award contracts to suppliers and set the amount it will pay for equipment and supplies. Yet despite the cost-savings offered by the CBP, other challenges began to pop up.

Jodi, a 68-year-old home-oxygen user, receives her oxygen through Medicare, which means she has the right to specific standards regarding her oxygen equipment. These standards include the right to choose an oxygen company, the right to get equipment that’s both correct and working, and the right to receive instructions on how to use the equipment. But when about half of patients report some form of problem with their oxygen equipment, it’s clear that what seems good on paper isn’t always great in practice.

On the surface, the CBP could be called a success—it has indeed cut costs. But dig just beneath the surface, and a complicated web of red tape makes obtaining DME that much more challenging for the people who need it.

In 2016, just 5 years after the CBP started, the majority of pre-2011 DME suppliers stopped distributing to Medicare due to overly competitive bidding tactics like suicide bidding. Suicide bidding is a risky move in which DME suppliers submit bids that price some items at a significant loss, but price other items higher to make up the difference.

The DME suppliers were forced to cut more and more costs to stay in an increasingly competitive market. DME suppliers in rural areas felt this pinch the hardest. In 2016, these companies received only half the reimbursement of the year prior for a typical home oxygen setup. DME cost-cutting came in the form of refusal to carry newer, more expensive equipment, and laying off respiratory therapists, who are needed to educate patients on oxygen use and ensure equipment stays in working order.

It would be unfair, however, to blame this cost-cutting solely on CBP. In truth, this was only 1 of the factors that contributed. The American Thoracic Society held a workshop in 2017 about the issues plaguing the medical oxygen system and found that, in the absence of clinical guidelines, most doctors’ offices lacked the resources or knowledge to prescribe oxygen devices correctly. The process for evaluating and comparing information about available oxygen systems was too difficult and time-consuming, and prescribing offices were not allowed to speak directly to DME suppliers at the time of oxygen ordering. The result was imprecise, inaccurate, or poorly documented prescriptions that had to be reworked multiple times to avoid jeopardizing DME reimbursement. Often, DME suppliers gave confusing or conflicting information about whether they did indeed carry the necessary equipment.

Jodi recalls getting advice from online patient communities when she had to switch oxygen companies to get the equipment she needed.

“It took many months,” she says. “It wasn’t easy. I was grateful for the advice I got from patients I met online who had similar challenges.”

Instances like this led to a situation in which close to 90% of patient case managers in 2016 reported an inability to obtain equipment and/or services in a timely manner for their patients. Medicare’s standards do not guarantee equipment in a timely manner, nor do they mention a need to properly communicate with patients about any delays. A recent survey of experts revealed that patients who needed oxygen were sometimes unaware of their equipment choices, rights, and how to report issues. While doctors and DME suppliers went back and forth over inaccurate prescriptions and reimbursement claims, patients were left without their DME.

Patients have reported many problems with their oxygen, including issues with equipment malfunction, portable systems that do not deliver enough oxygen, and obtaining manageable systems that are easy to transport. Jodi was 1 of the patients who had issues with her portable tank. She recalls, “I wouldn’t go out of the house because it was too difficult. To get me to my daughter’s graduation, everybody had to hold [an oxygen] tank. It was ridiculous.” There are so many patients like Jodi, whose inadequate oxygen supplies leave them stuck at home with limited mobility for work, travel, or exercise.

Over half of case managers noted that delays in obtaining DME (which includes medical oxygen) have contributed to patients experiencing medical complications, some of which led to hospital readmission. For those who depend on oxygen, these delays may get worse as the demand for oxygen grows. America’s population is becoming older, long-COVID symptoms place additional strain on medical oxygen use, and there’s a large number of people with COPD and other lung disorders.

...SOME EXPERTS OFFER A HOPEFUL FUTURE FOR THE 1.5 MILLION AMERICANS AND COUNTING WHO NEED MEDICAL OXYGEN.

Even so, some experts offer a hopeful future for the 1.5 million Americans and counting who need medical oxygen. At a workshop of doctors, payers, and DME suppliers brought together to develop solutions to what some describe as an oxygen crisis, they agreed that “optimal oxygen therapy prioritizes… each individual patient’s quality-of-life and health outcomes.” They proposed a range of solutions, including developing predictive technology that adjusts oxygen flow according to patient mobility needs, studies to assess DME reimbursement practices, and establishing standards for mandatory patient education.

Although it remains to be seen which solutions the American healthcare community will implement, there’s comfort knowing smart solutions are out there. It may not happen before Jodi has to walk her daughter down the aisle, but America’s medical oxygen crisis is solvable, and an end may soon be in sight. Until that day, Jodi will use her strength, courage, and oxygen to celebrate this special day. ■

5 WAYS TO MAKE LIFE WITH OXYGEN TOLERABLE

OUTFIT YOUR TANK:

Adding padding to parts that rub against your skin can reduce irritation and ear-loop pain. Fifty-foot cable covers can keep you mobile and the hose from knotting. Search online for tons of customizable options for both portable and standard oxygen tanks and tubing, like tank totes, which make it easier to take your oxygen on the go and can make your tank feel like yours.

KEEP EXTRA OXYGEN HOSES AND NOSE CANNULAS CLOSE BY:

Vacuuming, pets, grandchildren, even chairs— all can easily damage your plastic oxygen hose and nose cannula. Make sure you have a few extras close by so minor accidents don’t turn into an emergency.

KEEP AIRWAYS HYDRATED:

Morning headaches or dry and bloody noses? Use saline spray along with a water-based lubricant to save the inside of your nostrils. Bonus tip: drinking lots of water can help with mouth dryness—keep a water bottle close by. And you can always talk to your doctor about adding nebulized saline to help hydrate your airways.

AVOID THE LASTMINUTE DASH:

Dinner out, weekends away, graduation ceremonies—make sure you take the time to think through everything you need beforehand, like valet parking, extra batteries, or documentation from your doctor to avoid airport security snags, to help plans go smoothly.

SAY HELLO TO ALOE VERA:

Products with oils and petroleum are not recommended for those using oxygen, so look for water-based moisturizers like aloe vera that won’t damage tubing or put you at risk of burns. Bonus tip: keeping an aloe plant in your home can help purify the air and gives you access to fresh aloe when you need it.

Always refer to your equipment instructions for use before making any modifications to your equipment. Talk with your doctor if you experience changes in your health. Do not use skin products that you may be allergic to.

STAYING INDEPENDENT:

Insightful tips & tricks from Jodi

When life gives you lemons, think “I can”

Life with bronchiectasis (BE) can be tough. I realized saying “I can’t do it” meant I was missing out. But when I changed my answer to, “I can try,” I gained a more positive “yes” attitude towards life.

Stay calm

Anxiety begets anxiety, which led me to more episodes of breathlessness. A combination of breathing techniques, like taking deep breaths that are focused and slow for 5 minutes, and meditation now help me keep calm and collected.

Take the hassle out of lathering up

I recommend taking a bath to avoid shower steam and using an extra-large terry bathrobe instead of a towel to make drying off loweffort. If you prefer showering, cracking the shower door or window to let out the steam may be better than a fan.

A little bit of sweat does a lot

It’s important to keep fit with BE, and for me that means virtual fitness classes. You can find them for free online, and I can’t recommend this enough. Talk to your doctor about what exercises you should be doing.

Get connected with bronchiectasis groups

Check out the groups online. Find out what other people have to say, throw in keywords, and search! But use the information wisely—remember, your doctor is your go-to. Check out the list on SpeakUpInBronchiectasis.com to get started.

To see more tips from others in the BE community, use your phone's camera to open the QR code:

THAT BREATH FELT GOOD.

Seeing both sides

How a trip to the ER started a nurse on her greatest health mystery

When you’ve been a nurse for almost 20 years, you think you’ve seen everything. But then I got hit with a disease even this healthcare veteran didn’t see coming.

It was the end of 2019. I was an active nurse who loved gardening, reading, and the arts. One day I started feeling fatigue, shortness of breath, and chest pain. I had a suspicion that these symptoms were cardiac-related, so I went to the emergency room right away.

After I was admitted to the hospital, the doctor told me I either had a heart attack, developed myocarditis (an inflammation of the heart muscle), or both—they weren’t quite sure. I was treated and sent home with a slew of medications.

Three weeks after my hospital stay, I started to notice I was short of breath and fatigued while getting ready in the morning. It was hard to take a shower or feed my pets. I was also experiencing severe night sweats and brain fog to the point of losing words. I naturally thought it was related to my recent cardiac event.

I went back to the doctor to get tested. Turns out, these new symptoms weren’t cardiacrelated at all.

A hidden clue

I went home with no answers. The doctors couldn’t figure out what was making me so tired and short of breath. I felt frustrated as I sat down on my couch to read through the after-visit notes they gave me.

Most patients probably don’t pay any attention to these notes, but as a nurse I eagerly devour them like a mystery novel. You never know when they might contain a hidden clue that can give you insights into your health.

As I pored over the notes, something made me catch my breath: the computed tomography (CT) scan they ordered detected nodules in my lungs.

Now, I don’t know if my cardiologist even saw that note, or he felt like it was not significant enough to warrant further investigation, but

either way it was not brought to my attention as a cause for concern.

But it did concern me. My instincts as a nurse told me something was not right. I felt like there was much more going on than just cardiac disease. I realized in this moment that if the doctors couldn’t solve this mystery for me, I had to become my own detective.

I immediately picked up the phone and made an appointment with my cardiologist.

Finding allies

I arrived at my appointment with this clue in hand. I would have just gone directly to a pulmonologist myself except I needed a referral.

After speaking with the nurse practitioner about my symptoms and the CT scan findings, she said with concern in her voice, “You need to see a pulmonologist.”

I said with a laugh, “I know that, I’m a nurse!”

Outwardly, I was polite and gracious to the nurse, who had sat with me for about an hour listening to my struggles. But inwardly I was frustrated that I had to jump through these hoops in the first place just to get a referral to see someone who could help me.

By now it was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and pulmonologists weren’t easy to come by. I would have had to wait at least 6 months to get an appointment with the one the nurse practitioner recommended. And I couldn’t afford to wait that long.

Desperate to find another solution, I went to see my primary care provider for advice. He and I go way back, and he’s become my biggest healthcare ally. Finding a primary you can trust is essential, and I’m glad he’s on my side.

When he heard my story, a look of concern came over his face. He agreed I couldn’t wait 6 months to get treatment, so he referred me to another pulmonologist who got me right in.

I breathed a sigh of relief. I knew my primary care provider would come through for me.

It was a good thing, too, since this new doctor discovered I had NTM—or nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease.

NTM lung disease is caused by bacteria that’s naturally found in the air and water. I have an autoimmune disease that may have increased my risk. I also love steamy showers. But after I was diagnosed, I permanently switched to taking baths every 5 days since steamy showers can contribute to infection.

Boy, do I miss my showers.

Mystery solved?

As a nurse I mainly worked with Alzheimer’s, dementia, multiple sclerosis, and hospice patients, so lung disease was not my area of expertise. I immediately started asking my doctor questions about my newly diagnosed disease. However, a doctor is just one source of information. I also like to do my own research to learn everything I can about my health. When I was diagnosed with NTM, I had a lot to catch up on.

When I was researching NTM, I came across a series of videos on the topic, including information on a related lung disease called bronchiectasis, or BE for short. I had never heard of this disease before, and the condition was never brought up by my doctors, but the symptoms described in the videos felt all too familiar: coughing, excess mucus, shortness of breath, brain fog, and severe fatigue.

THERE WERE DAYS I HAD TO SIT DOWN TO BRUSH MY TEETH SINCE I WAS TOO WEAK TO STAND AT THE SINK.

And even though I was being treated for NTM, I was not getting better as quickly as my doctors had hoped. Some days I felt relatively OK, but on other days I had severe symptoms that made life nearly impossible. I just never knew what each day would bring.

There were days I had to sit down to brush my teeth since I was too weak to stand at the sink.

On other days, I had to sleep in the bathroom because I was too tired to walk there from my bedroom. There were times I just ended up falling asleep on the bathmat.

Then there were the days that the brain fog was so bad I would leave the stove and water on in the kitchen.

These unpredictable escalations of my symptoms, or flares, are common in BE. Though NTM was getting all the attention by my doctors, maybe there was something else at play?

Maybe it was BE?

A surprise twist

I made an appointment with my infectious disease specialist, who was treating my NTM, to discuss my findings. I told him, “I know something’s wrong. This isn’t normal.”

I sat in the exam room for a good 15 minutes telling him about my struggles. He nodded and took notes as I wiped away tears. I was lucky to have found a provider who was such a great listener— a quality I now look for in all my providers.

He looked at my CT scan results and, in collaboration with my pulmonologist, confirmed my suspicions: I had BE.

When I started this journey, I didn’t even know what that was. The odds of it being BE never even occurred to me. It’s not something you ever hear about, even in medical circles. When people my age have fatigue or breathing problems, cardiac disease and cancer tend to be top of mind. But BE? I never saw it coming.

Looking back, I wished I had been diagnosed sooner, and maybe researched my symptoms on my own sooner. It took 2 years from the time I went to the emergency room for cardiac issues to the moment I was diagnosed with BE. That felt like an extraordinarily long time to me, until I learned it can take 5 to 10 years for some patients to get diagnosed with BE. I realized that doing my own detective work helped me get a BE diagnosis—and a management plan—much, much sooner than that.

I was relieved to finally get an answer. It was hard-won through sheer self-determination. If I hadn’t advocated for myself at every step, I might still be taking bathmat naps with no hope of a functional life.

A new life with vibrating vests

Getting to the bottom of what was bothering me was only the first step. Managing life with BE was a whole other story.

First, there are the treatments. Nebulizers. Antibiotics. Vibrating vests that beat the mucus out of you. My entire daily routine is planned around them. I wake up, drink a protein shake, take my meds, get dressed, then do airway clearance with the vest. I’ve developed an intricate process for sterilizing my nebulizer equipment. Even though I’ve managed to be as efficient as possible, it still takes several hours out of my day. Treating BE can feel like a full-time job.

There isn’t a cure for BE, so using multiple techniques to clear mucus and infection is all I can do. They’re cumbersome, but I’m grateful to have them.

The treatments make a difference by helping to reduce my symptoms and make my life more manageable. But even with the treatments, I still feel fatigued and short of breath, and have multiple flares throughout the year. Because of that, I’m not as active as I once was, and probably never will be. I always thought my 50s would be filled with traveling, a busy social life, and career growth. But BE changed those plans.

I can’t walk as much as I used to. I ask for a wheelchair in airports if there’s a lot of walking involved. I limit my time outdoors in the summer since the humidity and poor air quality can trigger my symptoms.

My symptoms and flares made it impossible to continue my job as a nurse helping sick and disabled patients. Now, I’m the one who needs help.

“Be brave enough to hold on to the hope that life will be beautiful again.”

A beautiful future

Despite all this, I try to feel optimistic about the future. I have more hope now than I did at the beginning of my journey. I’m hopeful I’ll be back to work. My NTM disease is finally in remission after years of diligent treatment. But I know my future is going to look different because of BE.

If there’s one thing that keeps me going, it’s finding beauty in the world around me. Art and flowers especially help nourish my soul. When the air is clean and I’m not too tired, I like to take walks in the park to smell the flowers or go to an art museum. I listen to music to help me get through my daily, uncomfortable airway clearance sessions. And when I feel up to it, I go to concerts and travel to see family.

I have a quote written in my journal that sums up my perspective on life. It’s become my mantra for living with BE:

“Be brave enough to hold on to the hope that life will be beautiful again.”

I’m finding beauty in the present moment, and I believe I'll find beauty in the future, too. Even with BE. ■

A real phenomenon: What it means for people with BE

Imagine going into your favorite store one day, but the staff that normally fawns over you is now ignoring you in favor of the younger customers. At your favorite restaurant, the host seats the group of 20-somethings waiting behind you. It’s as if, suddenly, you’ve faded into the background of life.

While this may sound like an alternate reality, according to a 2016 survey, 70% of respondents felt that women become “invisible” as they age. (Only 32% felt the same happened to men.) Starting at age 52, women reported being ignored by staff at restaurants and stores, and even being cut in line.

This phenomenon is so common that it’s been given a name: Invisible Woman Syndrome— and it even happens in the doctor’s office. Studies have shown that women are more likely than men to be misdiagnosed and have their symptoms dismissed by their doctors. This means it often takes women much longer to be correctly diagnosed than men, which can have serious ramifications for their health and quality of life.

How did we get here? Numerous factors play a role, ranging from language nuances between men and women to deep-seated gender and age biases in the healthcare industry.

Research shows that, overall, women tend to be agreeable and use tentative language, which, while great for building relationships,

isn’t so great for convincing doctors of the severity of their symptoms. Some women’s tendencies to find common ground may make them more hesitant to disagree with their doctors and more likely to use uncertain expressions in their speech than men. A woman who doesn’t feel right about a doctor’s assessment may say, “Oh, OK, I see what you’re saying. I guess that’s what it could be. Sorry to waste your time.” Meanwhile, a man may respond to the same assessment with, “No, that doesn’t sound right. I want a second opinion.”

Also, up until the 1950s, there was a common belief in the medical system that women’s ailments were hormone-related or “all in their heads.” And until 1980, hysteria was an actual medical diagnosis given to women who expressed too much anxiety and anger.

This gender bias has also extended to clinical studies. Until the early 1990s, women were excluded from many clinical studies because some in the healthcare community worried that women’s menstrual cycles and hormones could sway the results, or the study drugs could harm their fertility or fetuses if they became pregnant. It was also thought that women were just smaller versions of men and would therefore exhibit the same symptoms and respond the same to treatments. Though women are now better represented in clinical studies, a dismissive attitude toward women still lingers in parts of the medical community.

But there are biases beyond gender that impact healthcare. Race and ethnicity also affect treatment and outcomes. One example involves diagnostic algorithms and guidelines that adjust outputs based on a patient’s race or ethnicity. Physicians use

these algorithms to determine individual risk assessment and guide clinical decisions. By factoring race into the basic data and decisions of healthcare, these algorithms may breed race-based medicine.

Spirometry, one of the most common ways to measure lung function, is affected by these practice guidelines. The expected lung function values set for Black American patients date back to the 1800s and are around 10% to 15% lower than they are for white patients. This means that they are less likely to be diagnosed with a respiratory condition, since the lower lung values are considered “normal” by these standards.

Ageism is also common in healthcare. Many studies have shown that doctors sometimes dismiss the symptoms of their older patients as just signs of old age.

While hard to directly observe or prove, the biases that contribute to Invisible Woman Syndrome may be experienced by people living with BE—66% of BE patients are women, with an average age of 68. BE also notoriously takes a long time to diagnose since its symptoms (persistent cough, shortness of breath, and fatigue) tend to mimic betterknown respiratory conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

In Allison’s case, self-advocacy and persistence were keys to getting the care she needed. It took her 2 years, lots of research, and finding the right providers to fully understand what she was dealing with.

“It was frustrating,” she reflected. “I had to become my own advocate to finally get where I needed to go.”

“Everyone deserves to be seen.”

But you don’t have to be a nurse like Allison to learn how to advocate for your health.

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ASK QUESTIONS

Even if your provider seems rushed, don’t leave the appointment until you’ve had all your questions answered. If you have more questions later, call or email your provider. Don’t be afraid to ask questions like: “What does that word mean?”, “Why are you prescribing that?”, or “Could it be something else?” Keep asking questions until you have the information you need to make good decisions about your health.

DO YOUR OWN RESEARCH

Read through the notes handed to you after each appointment and follow up with your provider if anything is unclear. Research your symptoms using trustworthy sources such as MedlinePlus.gov. If you feel your provider may have overlooked a possible condition, be sure to follow up with them.

FIND A NEW PROVIDER IF NEEDED

Having a care team you can trust is essential to good health outcomes. If you feel your provider is not listening to you or providing the care you need, don’t hesitate to find someone who will—such as a pulmonary specialist who is an expert on your condition. Ask your primary care provider for recommendations or contact your insurance company for a list of providers in your area. Read reviews online to see which provider may be a good fit for you.

TRUST YOUR GUT

You know yourself better than anyone— even your provider. If something doesn’t feel right to you, keep pushing until you find answers.

Self-advocating may not be easy, but it’s essential to getting the care you need. Providers are people, too, and they’re susceptible to the same unconscious biases that we all are. Sometimes, providers need your help to give them the information they need to look in the right direction. By self-advocating, asking questions, and communicating your needs, you can work with your provider so they deliver their best care.

Whether it’s at the doctor’s office or your favorite store, speaking up and sharing your perspective is helping you and all patients shed the cloak of invisibility for good. After all, everyone deserves to be seen. ■

Allison learned to speak up for herself.

The 10 BE medical terms you need to know

Bronchiectasis

(brong-kee-eck-tuh-sus)

is a chronic condition in which damage causes the airways in your lungs (bronchi) to become widened (ectasis), making it hard to clear mucus and making lungs more prone to infection.

Getting a diagnosis for bronchiectasis can be overwhelming, but these key terms can help you better understand the condition and navigate the complex world of this disease.

01 4 COMPONENTS OF BE

— There are 4 key interrelated factors in BE: difficulty clearing mucus, infection, inflammation, and lung damage. These 4 factors impact one another and can lead to the disease getting worse over time.

03

DIFFUSE AND FOCAL

— Diffuse BE appears in many areas throughout the lungs, whereas focal BE is focused in one specific area.

— Coughing up blood, caused by damage to the bronchi. It usually appears with mucus.

07

04

DYSPNEA

— A medical term for “shortness of breath,” a common symptom. May be caused by a buildup of mucus in the bronchi.

INSULT

— Also known as the initial damage to the lungs, usually caused by an infection, inflammation, some other lung condition, or trauma like smoking or radiation.

EXACERBATION

02 CILIA

— Hairlike structures that move mucus out of your lungs. BE damages cilia, making it more difficult to clear mucus from the bronchi.

— Also known as a flare, a sudden worsening of symptoms, like coughing, fatigue, mucus production, shortness of breath, and fever. Irreversible lung damage may occur due to these flares, so it’s important to talk to your doctor when they occur to ensure you’re on the right treatment plan.

NEBULIZER

— A device that turns liquid medication into a mist, which is then inhaled.

SPUTUM

— Another term for mucus from the lungs and airways.

10

For more BE terms you need to know, use your phone's camera to scan the QR code: 05

SPUTUM CULTURE

— A sample of sputum that’s taken by a doctor and sent to a lab to detect what type of infection may be in the lung.

Commonairway clearancetechniques explained

Deepcough

Airwayclearance,whichhelpsremovemucus fromthelungs,isanessentialBEtreatment. Mosttechniquescanbedoneathomeinorder topromotegoodlunghygiene.

Adeep,controlled cough that’s more effective and less tiring than typical coughing.

Huff cough

“Breathing out” the mucus by taking a deep breath, then exhaling like you’re fogging up a mirror.

Percussion

Hypertonic saline

A type of drug known as an expectorant that is used to help expel mucus from the lungs.

Positive pressureexpiratory (PEP)

A technique that involves breathing in and out of a handheld device that creates resistance while exhaling, helping to force out mucus. Oscillating PEP devices add vibration to aid clearance.

vest (high-frequency chestwall oscillation)

A vest that vibrates and creates “mini-coughs” to loosen the mucus. May be used in conjunction with huff coughing and nebulizers.

Gentle movement

Light exercise like walking can help remove mucus from the lungs. Always talk to your doctor before you try any of these techniques to determine if they are right for you.

To learn more about these airway clearance techniques and more, use your phone's camera to scan the QR code:

Looking for harmony

How a rapper with BE lost and found her voice

Imagine this: You’re 23 years old and you’ve just been featured on a multiplatinum rap album. You’re so close to stardom, you can almost reach out and touch it like a fan’s outstretched hand. The world feels like it’s yours, but in a few short years, several life-altering diagnoses will change everything.

At my highest high, I couldn’t imagine my life would go from center stage to in and out of the hospital. When my neuromyelitis optica (NMO) temporarily stole my ability to walk, I thought, “How can I recover?” When sarcoidosis, an autoimmune disease, appeared, I figured my life was over. I couldn’t guess that something else I’d never heard of—bronchiectasis (BE)—would be the final straw, the one thing that brought me to my lowest low.

But I’m still here. I still have hope.

In tune with myself and my purpose

It seems like a lifetime ago, but as a child, rapping was as easy as breathing. I didn’t have the issues I have now, and I was rarely ever sick. I was just a regular person—as regular as anyone could be starting their music career at the same time they’re starting elementary school.

I was only 9 years old when my sister and I formed a rap group out of our family apartment in Decatur, Georgia. While it started out as dancing, our group quickly became well known in the city of Atlanta, performing alongside other pioneers in the genre. During almost 2 decades, we were fortunate enough to be cheered on by local Atlanta legends, and eventually caught the attention of a national rap icon and went on to be featured on a multiplatinum album.

I had always been a writer, mostly of short stories and poems when I was younger. So when our first producers said they were going to write for us, I pushed back. I knew what I had to say was something that only I could write.

Not many people get the opportunity to chase their dreams at such a young age, but growing up in a family with 5 brothers and sisters

meant that I learned early on how to stand out and make myself heard.

What I loved most about my time in music was how performing made me come alive. When I was on stage, everything was different. I loved it up there. I could be me, I could be free, and I could always speak my mind.

But, while my rap career spanned about 20 years, I had no idea how much of a whirlwind my next act would be.

Losing my voice felt like everything

Over time, I started to want more stability than music could provide, so I pivoted to advertising. I spent the next 7 years paving my way in a new industry. I was surrounded by creative people who encouraged me to use my voice in ways I never had, first as a producer and then eventually on the design side.

Around 2012, almost overnight, I lost my ability to walk and all feeling from the waist down. I was diagnosed with NMO, a chronic autoimmune disorder. After some time I regained the ability to walk, but the experience is one that still haunts me to this day.

Then in 2015, I was diagnosed with another autoimmune disease, sarcoidosis. Everything about my normal life disappeared,

I wasn’t prepared for how bad things became when I had to add the oxygen.

I didn’t know what to expect. On the one hand, I was relieved to know why I couldn’t breathe. On the other hand, I didn’t know how my body was going to feel tomorrow—or the next day. I felt like I didn’t have any control at all. The worst part was that I felt like some kind of monster, someone unable to stop coughing up mucus all the time. How could anyone want to be around that? So instead of facing it, I isolated myself, staying in hiding. Anything to avoid looking completely disgusting. There were some days when leaving my bed wasn’t even an option because of how exhausted and in pain I was. I got really, really depressed and anxious. I had NMO. I had sarcoidosis. I had BE. I had the inhalers, nebulizers, antibiotics, steroids, and medicines that went along with each condition. I was heavily medicated all the time. I was managing it—barely. Still, I was hanging on. I wasn’t prepared for how bad things became when I had to add the oxygen. Sure, it helped me breathe a little easier. But it was horrible…this physical representation of everything I had to rely on. This weight that I literally dragged behind me. I called it my umbilical cord because I couldn’t do anything without it attached. and my days were a constant stream of hospital visits and tests. To make matters worse, the sarcoidosis made me more susceptible to other diseases like COVID-19 and pneumonia, which I got repeatedly.

It’s impossible to work when you’re that sick. I had no choice but to say goodbye to a career I loved—that I made my own—and go on disability. For several years, life was uncertain, to say the least. But amid the perfect storm of treatments, hospitalizations, and disability, I managed to push on, to stay calm.

In 2021, I was hospitalized again with a severe case of pneumonia, and during that time I started having problems breathing. The emergencyroom nurses initiallythought I had COVID again, but after a computed tomography (CT) scan the critical care doctor diagnosed me with BE.

With my new BE diagnosis, things started to make sense: the repetitive pneumonia, the mucus buildup, the times my symptoms would get worse. My doctor called these periods exacerbations, or flares. I was struggling to breathe, and it was terrifying. When they told me they were sending me home on oxygen, I understood why. It was a lot.

The oxygen tank stole the last shred of normalcy I had. It took away the invisibility of my disease and left me defenseless. I was tired of needing everyone’s help all the time, of not being able to do anything on my own, of having to depend, depend, depend. But mostly I was tired of not even being able to breathe on my own. I wanted to give up.

Finding new ways to be heard

When I was finally able to see things clearly, I knew I needed to rediscover my purpose. I’ve always been in touch with my spirituality, so I took to teaching the Bible. When you’re on disability and you have no job, and with no car, no partner, no children—it’s hard to know what your pillars of support are. But turning to my faith, and sharing in the Gospel, I’m able to share my story of survival. It helps ease my anxiety and brings me back into the world.

Now I’m focused on trying to take care of my body the best ways that I can. I still get flares about once a month, but I approach my bad days with a different mindset. I know flares are going to happen with BE, so I work to be prepared with all the necessary tools, like the action plan I’ve built with my doctor. I’ve gotten better at recognizing the signs and listening to my body.

Most recently, I became vegan. Before this, I experienced a lot of eating complications. Certain foods made my mucus thicker and more difficult to clear. I needed to make a change. Switching up what I eat has really made a huge difference for me, and given that I love to cook (thanks to my father), I’ve been able to create craveable dishes that have made the whole transition easier.

My next goal is to find my voice again. It’s a different world that we live in now. There used to be all these limitations in the music industry for women, like once you got to a certain age or had a baby that was it. But now it’s completely different. You could be 70, rapping in a wheelchair on oxygen, and people would completely accept it. I even have old friends from my time in music coming to me and asking when I’m coming out of retirement.

I think if I ever do anything in the music industry again it would be writing. I could be a ghostwriter for other

people, or perhaps use my talents in a different way and try out voice-overs. Something that helps me reclaim the power of my voice.

As someone who’s lived through the highest highs and the lowest lows, I know firsthand that it’s a choice every day to wake up and rebuild—starting over again, but always learning. Because that’s life. While I’m not the same person who went on tour or was featured on a multiplatinum album, I’m still Amber. I’m still breathing. And I still have a lot to say.

I can’t imagine what comes next. I just know I can handle it. ■

Amber found a different rhythm— now see how she soars.

The BE rewind

5 things I wish I knew sooner

Whether you are newly diagnosed with BE or have had it for a while, there is always more to learn about managing this condition. Here are a few things that Amber has learned over the years.

1. A BE diagnosis is not the be-all and end-all. I have something wrong with me, but I can still take care of myself and my body. I just need to be open to changing my goals and expectations.

2. There’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to BE. Some people experience more mild symptoms and others, like me, may need to use oxygen at times. What I need changes often and may even vary on a day-to-day basis.

3. Younger people can develop BE. Although it’s more common in people older than me, you don’t have to be a certain age to have it. I was actually diagnosed in my late 30s.

4. Diet made a difference. When I transitioned to a vegan diet, I was able to clear up some of the complications I had with mucus.

5. It’s important to keep your doctor in the know. Every time things get bad or my symptoms get worse, I try to go to the doctor to have them check me out. I don’t try to self-manage my flares like a person may try to do with a cold.

only

songs to de-funk a mood

Having a bad day with BE or just looking to boost your mood? Check out the top song recommendations from Amber.

The importance of airway clearance and breathing new life into your lung health

Most experts agree that airway clearance is one of the most important areas of care for people living with bronchiectasis (BE), with published guidelines around the world recommending it as a key component of treatment and preventative regimens.

In BE, damage to the lung airways can impair the body’s ability to remove mucus from the lungs. Mucus can then build up in the airways, making it easier for infections to develop. Doctors may recommend various airway clearance methods to help remove the mucus, including huff coughing, inhaled medications like hypertonic saline, handheld devices, a percussion vest, or pulmonary rehabilitation.

The goals of airway clearance include improving symptoms, reducing exacerbations (also called flares), reducing infections, and increasing quality of life. Being able to clear mucus more effectively can improve breathing and reduce cough and breathlessness. While experts agree on the importance of airway clearance, the therapies are still significantly underused.

A 2017 study of more than 5,000 people with BE reported that only half (50.5%) of participants performed airway clearance techniques regularly. To add to this, out of all prescribed components of BE treatment, airway clearance had the lowest rate of adherence, with 1 study reporting that only 31 of 75 participants, or 41%, were compliant.

So what’s causing this disconnect?

People with BE do not commit to airway clearance for a number of reasons. For example, it can create a higher treatment burden when added on top of other inhaled or oral medications. The methods are also time-consuming, and there’s a general lack of understanding that airway clearance is a necessary component of therapy.

And the underuse of airway clearance is not only due to lack of adherence. One recent study reported that less than half of participants were prescribed airway clearance by their doctors as part of their BE treatment plans.

Perhaps the best way to approach airway clearance is through a more personalized approach that matches each person to the most simple and effective method for them. The right airway clearance techniques can be identified based on health, environmental, and social factors—combined with an effort to benefit a person’s lung health while staying within a reasonable time commitment.

Even though experts agree that airway clearance selections should be driven largely by the personal preference of the individual taking the treatment, airway clearance can feel like a burden. So what if there were ways to make this necessary but time-consuming practice a little less daunting?

Striking a new chord

To breathe some fresh air into your daily airway clearance routine, adding music may be a great strategy. Music has a remarkable ability to lift our spirits, distract us from discomfort, and make any task more enjoyable—especially ones that are burdensome, like airway clearance. Let’s look at some ways to infuse rhythm, melody, and entertainment into your airway clearance routine.

Choose your soundtrack for therapy

Much like how a movie’s soundtrack can improve its scenes, choosing the right music is key to setting the tone for your routine. Look for songs that inspire positive emotions or have a lively beat. Consider creating an airway clearance playlist of your favorite genres, artists, or songs. Whether it’s upbeat pop, energizing rock, soothing classical, or even your favorite show tunes, find the musical styles that help motivate you the most when airway clearance feels like a chore.

The beat is everything

To create a harmonious rhythm between your airway clearance treatment and music, the beat is essential. Know how long each airway clearance session will take, and select songs that match or exceed that time frame. This will not only help you stay on track but also serve as an enjoyable countdown, making your treatment feel more structured and focused.

Establish rituals

Just like a band will have an opening and closing number when it performs, you can bring the same structure to airway clearance. For example, start by choosing a particular song that always plays as you begin your treatment. Over time, your mind will associate that specific music with the start of your session, making it easier to transition into the routine. Similarly, selecting a final song can provide a sense of accomplishment and closure when your session ends.

Delight in the distraction

During airway clearance, it can be helpful to move your attention away from any discomfort or boredom. Keep your mind off the treatment by focusing on the lyrics, melody, or rhythm of the music. Sing along, hum, or tap your fingers to the beat. By immersing yourself in the music, you’ll find yourself more engaged and less likely to perceive the treatment as a chore.

Go wireless

It’s never been easier to engage with music. Wireless headphones or portable speakers ensure a hassle-free experience. You can also explore various music streaming platforms or mobile apps that offer personalized playlists, song recommendations, and mood-boosting features. You can even view live performances of many of your favorite artists or songs online for free. Experiment with different technologies to find what works best for you.

Have a listening party

Music has a unique ability to bring people together. Share your airway clearance routine with family members or close friends who can join in or support you during the process. Their participation will not only make the routine more fun but also strengthen your bond.

Making music a part of your airway clearance routine can revitalize your treatment regimen and make it a more enjoyable experience. By choosing the right music, matching the timing, creating rituals, and engaging your senses, you can turn an otherwise boring task into a pleasant journey. While BE isn’t always in your control, how you make your routines work for you is. So, put on your favorite tunes, tap into the rhythm, and let the music harmonize with your airway clearance routine. ■

Maintaining a well-balanced diet is important for your lung health

Amber decided to change her diet and become vegan, and it’s had a huge impact on her well-being. Here is one of her favorite recipes.

You may need to make adjustments to this recipe based on your condition. Talk to your doctor before making any changes to your diet.

Amber’s Heart Pockets

Heart pockets are air-fried artichoke hearts, stuffed in a multigrain loaf (or pita bread) pocket and topped with sun-dried tomato aioli.

INGREDIENTS:

1 to 2 jars of artichoke hearts

1 cup flour

1 cup water to adjust texture, or more as needed

1 cup fine breadcrumbs

1 cup vegan mayonnaise

1 jalapeño pepper, chopped (optional)

1/2 jar of sun-dried tomatoes

1 teaspoon lemon juice, or more to taste

1/2 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1/2 teaspoon kosher salt, or other coarse-grain salt, or to taste

Dried spices, salt, and black pepper to taste

1 loaf multigrain bread (or 5 pitas)

Vegetable sandwich toppings to taste

INSTRUCTIONS:

Air-fried artichoke hearts:

1. Preheat air fryer to 350°F (175°C).

2. Drain jarred artichoke hearts, pat with paper towel, and squeeze out excess moisture.

3. Mix flour and 1 cup water together to form a batter about the consistency of pancake mix. Feel free to add any dried spices you like, salt, and black pepper to this batter.

4. Place fine breadcrumbs in separate bowl. Feel free to add any dried spices you like, salt, and black pepper to the breadcrumbs.

5. Dip each artichoke in batter, then coat in the breadcrumb mixture. Drop 1 layer of breaded artichokes into the preheated air fryer.

6. Air fry on high for 7 to 10 minutes. Check for desired crispness before removing.

Aioli:

Prepare the aioli by mixing vegan mayo, chopped sun-dried tomatoes, chopped jalapeño (if using), and lemon juice in a blender. Add olive oil and mix until desired consistency. Add salt to taste and adjust ingredient quantities based on your preferences.

Assembly:

1. Slice off the end of the bread loaf (unless using a pita) and remove extra bread from the middle, forming a “pocket.”

2. Spread the aioli on the bread, and stuff the pocket with crispy artichoke hearts, adding any veggie topping (lettuce, tomato, onion, etc) you like.

The

Staying positive when every breath is a struggle

For Edna, life with chronic lung conditions started early. As a child, she had trouble keeping up with her friends without being out of breath. Breathlessness made her feel insecure, like she was living with a hidden disability. But Edna persevered, all the way through adolescence and into early adulthood. Until one day, almost overnight, she completely lost her breath.

What her doctors initially thought might be a hole in her heart or a heart murmur brought on a new sensation that wasn’t too dissimilar from breathlessness: fear. Edna believed she’d end up like everyone else on her mother’s side of the family—a casualty of heart disease. But the diagnosis was asthma, and at 22 years old, Edna decided not to let the condition dampen her outlook. She chose to focus on the bright spots in life.

Here are Edna’s bright spots, in her own words.

BRIGHT SPOT #1

A wild, wild career full of fun jobs

My career has been a little on and off, but I’ve had a lot of really fun jobs over the years. I worked at a country club in Manhattan Beach, at LAX as a ticket agent for a major airline before they merged. I even worked at a national flower store chain, which inspired me to open my own flower shop in Santa Monica.

My shop didn’t last very long. Around this time, I started noticing I was getting more out of breath, more tired, making it harder and harder to put in the long hours required to run a flower business. So, with a little help from my friends, I turned my flower shop into a yarn shop. During this business venture, my life changed in 2 significant ways: first, through that little yarn store, I created a sewing circle with a mission to knit and donate hats and blankets for premature babies across the country.

The second change that happened was my bronchiectasis (BE) diagnosis.

That was 14 years ago. I’m no longer working— I had to stop working entirely during the pandemic because of my BE. And then, as the world started to return to normal bit by bit, I didn’t go back to work. I miss all those jobs and being able to support myself. But I look at all these work experiences and feel lucky to have had jobs that I truly loved and that allowed me to bring some bright spots into people’s lives.

Marrying the one who takes my breath away

I met my husband in 2003. We were close friends forever, and then in 2015 we decided to get married. He was a foreman on an oil refinery—he likes to joke that a computer does his job now. He’s like me: very calm, very easygoing. He’s the nicest person and a great friend. He was previously married, and even though his children are adults with families of their own, he’s always made sure we’re one big family.

My husband has always been there to support me with my BE, always telling me to take it slow, take a lot of water with me if I’m going somewhere, reminding me to use my vest. I know it’s only 20 minutes a day, but it just seems like it takes forever, and it makes me feel like I’m going to take off like a rocket. But my husband keeps reminding me to use it. I’ll make up an excuse or just flat out say “I just don’t want to do that!” and he’ll say, “But you don’t sound very good today.” And the truth is, the vest does help me.

About 25 years ago, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He’s now in the late stages of the disease, and in some ways our roles have reversed—I’m the one reminding him to take his medications, bringing him to doctors’ appointments, helping him keep a positive outlook. It gets scary for me when I think about the future. I think, one day I may be all alone. I don’t like to think about that.

Being his caregiver has been emotionally taxing. I have to be careful and remind myself not to get burned out, because I believe stress can cause me to flare up. But we have nurses and physical therapists who help us, which has been a blessing for me. I thought I couldn’t be the caregiver my husband needs, but I am doing it despite my BE.

You can’t be sad in the sunshine

One of my favorite things to do before BE came into my life was travel. I mostly stayed close to home in California, visiting places like Mexico or Hawai‘i. But the great thing about California is that it’s such a big state with so many different climates. I’d go up to San Francisco, or to Lake Tahoe, but my favorite has been and always will be Palm Desert. Even to this day, I still go to Palm Desert every summer and tan. I have a high school girlfriend who lives there, and my brother lives there too. I really like the heat and think it’s good for my asthma and BE. I don’t experience a lot of breathlessness there. I think I can breathe better in Palm Desert.

With BE, it’s challenging to have long-term plans, but visiting Palm Desert is something I look forward to every summer. Having bright sunshine helps you to feel good about living. It helps you be happy you’re alive.

BRIGHT

Finding hope in the darkest place

I’ll admit—this part may not seem like a bright spot, but sometimes the only way to see the light is through the dark.

In my early 50s, I started noticing I was really out of breath. My asthma medications weren’t helping. I went to my doctor, and he ran a bunch of tests. Somehow, I ended up seeing the head of pulmonology at the hospital and was told that I had aspergillosis, a fungal infection. But when that test came back negative, another pulmonologist came up with another diagnosis: BE.

“What is it? What does that mean?” I asked. He said that there was scarring, that my lungs were losing elasticity. I felt the room around me get hot and smaller and darker. I’m sure

there were other things he told me, but all I could think was, “What does this mean?”

I came back for more tests. I saw the head pulmonologist again. Scans were up on the screen, and there they were—my lungs. “Wow, look,” was all the pulmonologist said. I could see my lungs, but I didn’t know what I was looking at.

“It looks like a lot of your airways are damaged. You’ll probably have to have a double lung transplant at some point in your life.”

The room got hot again. And smaller. And darker. No one was there to hold my hand or tell me it’s going to be okay. At the time, I was working at my uncle’s income tax office. We had a client who had had a single lung transplant. I thought about him, how he didn’t look or sound too good. I thought about how my colleagues would say, “He’s not doing very well.” I thought, “Oh my god, that’s going to be me.” I came home from that doctor visit and told my husband, “I don’t know what this means, but I don’t think I’m going to be here very long.”

I couldn’t accept that. I needed another opinion. A third pulmonologist said I would need oxygen 24/7. And I just sat there thinking, “What? What are you talking about? I can breathe okay.” I felt as if she didn’t have any hope for me—in fact, she could have simply said, “You’re hopeless,” and I would have felt just as terrible. Nobody should ever feel hopeless, so I went searching for someone who understood BE.

My current doctor also prescribed oxygen, and I use it at night. She’s been monitoring me for quite some time now. When I tell her about my fears of a lung transplant, she reassures me with warmth and compassion that my BE is being managed, which to me is the bright spot in all of this. I know she’s very busy, and she only has a certain amount of time with each of her patients, but she gives me hope. She helps me feel better about the uncertainties I face with BE.

Breathing in Barcelona

One year after I was told I’d need a double-lung transplant, I decided to do something bold. A close friend was living in Barcelona and insisted I cross the pond. So, I went to Spain for a month! What an incredible journey that was, seeing a side of that city that tourists don’t always see. I wasn’t going to let BE control my life, so every morning, I’d pack a bag and head into town for the day. I swam in the Mediterranean, visited the Picasso Museum, and explored all the Gaudí buildings. I would look at these pieces of art and meditate on the incredible artists and their haunted and troubled lives. They reminded me of myself. That trip was the best experience of my life with this disease.

BRIGHT SPOT #6

A routine is not as bad as it seems

A long time ago, I had a bad flare that ended in a hospitalization. The doctors wanted to observe me overnight. After that, I went to a lung rehabilitation program that was sponsored by my doctors. It was incredible how much respiratory therapy taught me that I didn’t know, especially how important a routine is. I learned how to take my medicines correctly, what triggers my flares, and how crucial low-impact exercise was for me.

My routine starts in the morning: I take all my medications for BE and other conditions at one time, which includes 2 inhalers. I’ll also do my rescue medication if I feel a little short of breath. And usually once I take everything, I feel pretty good—good enough that I can do an errand or 2. Then when I come home, I’ll take a nap if I’m really fatigued. But the real thing that’s helped the most is exercise.

I exercise 3 days a week at the senior center. It’s mostly chair exercises, which aren’t very strenuous, but they move all your muscles and tighten things here and there. I went to my doctor about 2 years ago for spirometry

to test my airflow. And it turns out that my lung function had improved with all the exercising! She said, “You’re still severe,” but I was happy to know that exercising really does help. Everyone is different, so it’s important to talk to your doctor about what exercises you can do.

More than how exercise makes me feel physically, it keeps me engaged with people. I used to be part of an in-person support group, but it shut down during the pandemic. I miss the camaraderie of being with other people going through similar things. But I have a dear friend whom I exercise with regularly, and it’s a bright part of my week. She also happens to be a nurse, so there’s the added benefit of asking her questions if something feels out of whack.

Why look at the bright spots?

Here’s the thing about living with BE: there are a lot of dark moments. The stress, the anxiety, the constant watching out for triggers. I have days where I feel down. Depressed. Now pair that with not being able to breathe. It can be hard to maintain hope.

BE can turn your life into a challenge. There are things you may not be able to do. If I go somewhere and there isn’t an elevator—just stairs—that’s pretty scary. And even if I can make it up those stairs, it’s just so hard on my lungs. It’s not easy, especially if you’re not having a good day.

It’s hard and it hurts when you feel these challenges. But then I think about people with other illnesses that are a lot worse than mine, and I feel for them. I know I’m dealing with mine. I have to have faith that things will not

always be like this. So, I do one of the only things I can do during the bad, dark days: I talk myself into turning the bad thoughts around. I’ll say to myself, “It’s not going to last forever.” Sometimes your whole way of thinking will be different the next day. It’s not easy, but I do it, and it seems to help.

In fact, thanks to my positive outlook, people sometimes look at me and go, “I wonder how you’re sick, what’s wrong? You don’t look sick.” It’s true—sometimes I feel good. And other times, if you only knew. But hearing that boosts my self-esteem a little bit. It makes me feel like I don’t have a chronic disease.

So, I keep doing what works for me. I wake up and do my morning routine. I help my husband in the ways that I can. And when those dark thoughts enter my head, I stop, and talk myself into seeing the bright spot in all the darkness. ■

The science behind building healthy habits

Being a caregiver can be an incredibly rewarding experience. However, it can also be physically, emotionally, and mentally exhausting, and even more so if the caregiver is struggling with a chronic condition themselves. The positive emotions associated with caring for a loved one can often exist in the same breath as isolation and stress, and the risk of burnout among caregivers—whether by obligation or profession—is profound. It’s evenly split:

According to a recent report looking at caregivers of people over 50, just over half of those polled feel like their role as a caregiver gives them a sense of purpose. The rest don’t feel the same way.

For caregivers to do their job effectively, it is critical that self-care be practiced to help combat the stressors, anxiety, and burnout that are associated with caregiving.

In short, to be a good caregiver, caregivers must take care of themselves.

So what does self-care mean for a caregiver?

It’s important to look at how the stresses of being a caregiver impact one’s ability to give care. Many recent studies evaluate the effects of daily stressors on caregivers—both at home and in clinical settings—offering insights into how stress plays a huge role in their physical, emotional, and mental reactions.

A 2012 study looked at stress levels in people caring for loved ones with dementia and the effects of daily interventions (or breaks). It showed that caregivers who got 2 breaks a week had lower stress levels.

Another study looking at the effects of teaching nurses about self-compassion and mindfulness illuminated how important self-care is to caregiving. Before completing an 8-week training course, nurse participants reported how they felt across 6 emotional categories: self-compassion, mindfulness, secondary trauma (the stress of hearing a first-hand account of trauma), burnout, compassion satisfaction (the pleasure you get from helping others), and resilience. At the end of 8 weeks, the nurses reported again how they felt, and the scores showed a significant decline in secondary trauma and burnout. Not only that, but resilience and compassion satisfaction scores increased as well.

The more caregivers implement self-care into their routines, the better equipped they are to deal with both the emotional and physical stresses of their job.

A highly stressful situation

In the United States, the vast majority of unpaid caregivers are women. In fact, 61% of caregivers for people age 50 and up are women. Meanwhile, the average length of time someone provides care to a person over 50 is almost 4 years, with an average of 22 hours per week. This totals a whopping 4,522 hours of care per year.

According to a recent poll conducted by AARP, the number of Americans providing unpaid caregiving has increased from

43.5 million in 2015 to 53 million in 2020. Another way to look at this is that nearly 1 in 5 American adults is providing unpaid care to an adult with health or functional needs. But while the number of people stepping into the caregiver role has increased, so too has the burden of providing care. In 2020, more than a quarter of family caregivers reported having trouble coordinating care (compared to 19% in 2015), while more than one-third considered their situation to be highly emotionally stressful. If that weren’t bad enough, more than 20% of Americans said caregiving made their health worse, with their responsibilities making it difficult to take care of their own health.

Who to care for? Yourself or your loved one?

What happens when a caregiver is battling a chronic disease or condition but still has to answer the call to be a caregiver? For someone like Edna, who has been living with respiratory conditions including BE most of her life, the additional stress of caring for a sick partner adds a layer of difficulty to an already emotionally charged situation.

“You can get burned out being a caregiver,” Edna says. Even with the support of part-time nurses and physical therapists, Edna still needs to be careful because she’s found stress to be one of her triggers for flares. Like many people living with BE, a flare can put Edna in the hospital. “I’ll be wheezing, coughing. And when I can’t really breathe anymore, I go to the emergency room (ER). They’ll give me rescue treatments and oxygen.” But most importantly for Edna, a trip to the ER means no one is there to care for her husband.