PETER FINER

FINE ANTIQUE ARMS, ARMOUR & RELATED OBJECTS

ARMOUR

1 An Extremely Rare Pair of Saddle Swipe-Guards (Dilgen ) for use in the ‘Joust of War’ (Rennen )

c. 1500 – 1510

2 A Flemish Shaffron

c. 1520 – 30

3 An Important Armour attributed to the Habsburg Court Armourer Desiderius Helmschmid and the etcher Jörg Sorg dated 1545

4 A Rare Breastplate for Foot or Light Calvary Armour

c. 1550 – 60

5 A Cavalry Half-Armour

c. 1560 – 70

6 A Suite of Magnificent Armour for Man and Horse, Etched and Gilt in the Lombard Fashion Late 16th Century

7 A Very Rare Milanese Etched Breastplate charged with an Armorial Cross, for a Light Cavalry or Foot Service Armour, Inspired by the Etched Motifs of Pompeo della Cesa

c. 1580-1600

8 A Half-Armour of Blued Steel

c. 1580 – 1600

9 A North Italian Etched Circular Shield for Foot Service in the Manner of Pompeo della Cesa

c. 1580 – 90

10 A Fine Cuirassier Three-quarter Armour in the Manner of the ‘Master MP’

c. 1600 – 1620

11 A Model of an Armour for a Man and Horse in the 16th Century Style

c. 1850

An Extremely Rare Pair of Saddle

Swipe-Guards (Dilgen ) for use in the ‘Joust of War’ (Rennen )

c. 1500 – 1510

Southern Germany, Augsburg or Innsbruck. Steel, copper alloy, leather.

42 cm × 40 cm / 16.5 in × 15.7 in (each)

PROVENANCE

Possibly the Armoury of the Court of the Emperor Maximilian I

Private collection, Austria

The German tourney course with sharp lances, known as the Rennen (the mock ‘joust of war’), had evolved in the mid-15th century (from its first mention in 1436) and over successive decades existed in ever more numerous versions, as dictated by their differing objectives and rules, but all of these were run in the Lists without a tilt or barrier separating the riders. The contests were fast-moving (Rennen translates as ‘run’ or ‘race’), warlike in character and unfailingly spectacular. Among the more frequently practiced Rennen courses as many as seven eventual types were in fact fought without leg armour, other than tassets defending the thighs, and in some configurations a Rennzeug (Rennen armour) comprised the torso, head and arm portions only. Only a few exceptions such as the Feldrennen or Kampfrennen existed, in which reinforced field armour with full leg defences was worn.

The danger of jousting without a dividing tilt was to some degree of course the increased exposure to the opposing lance (the specialist armour provided good protection for the upper body, and the lance-points were often purposefully biased in order to deflect). The far greater danger in fact lay in the possibility

of the opponent’s horse passing too narrowly and seriously injuring the legs and perhaps the horse of the on-coming rider. This danger was not confined to the on-coming rider’s left side (the side intended to receive the lance impact) since a horse may startle and mistakenly bolt down the right side also.

To address this in the Rennen fought without leg armour, after about 1460 pairs of graze shields were suspended from the saddle, hung at a level covering the thighs and knees. Initially probably made of either hardened leather or wood, by about 148085 these had developed as steel ovoid or rounded shields referred to as ‘Streiftartschen’ (derived from the German ‘streifen’, to graze, known in English only by the misnomer ‘tilting sockets’). Several examples dating from circa 1485 survive in the Kunsthistorisches museum, Vienna, including one commissioned by the emperor in 1485 from the court armourer Lorenz Helmschmid of Augsburg (B 11).

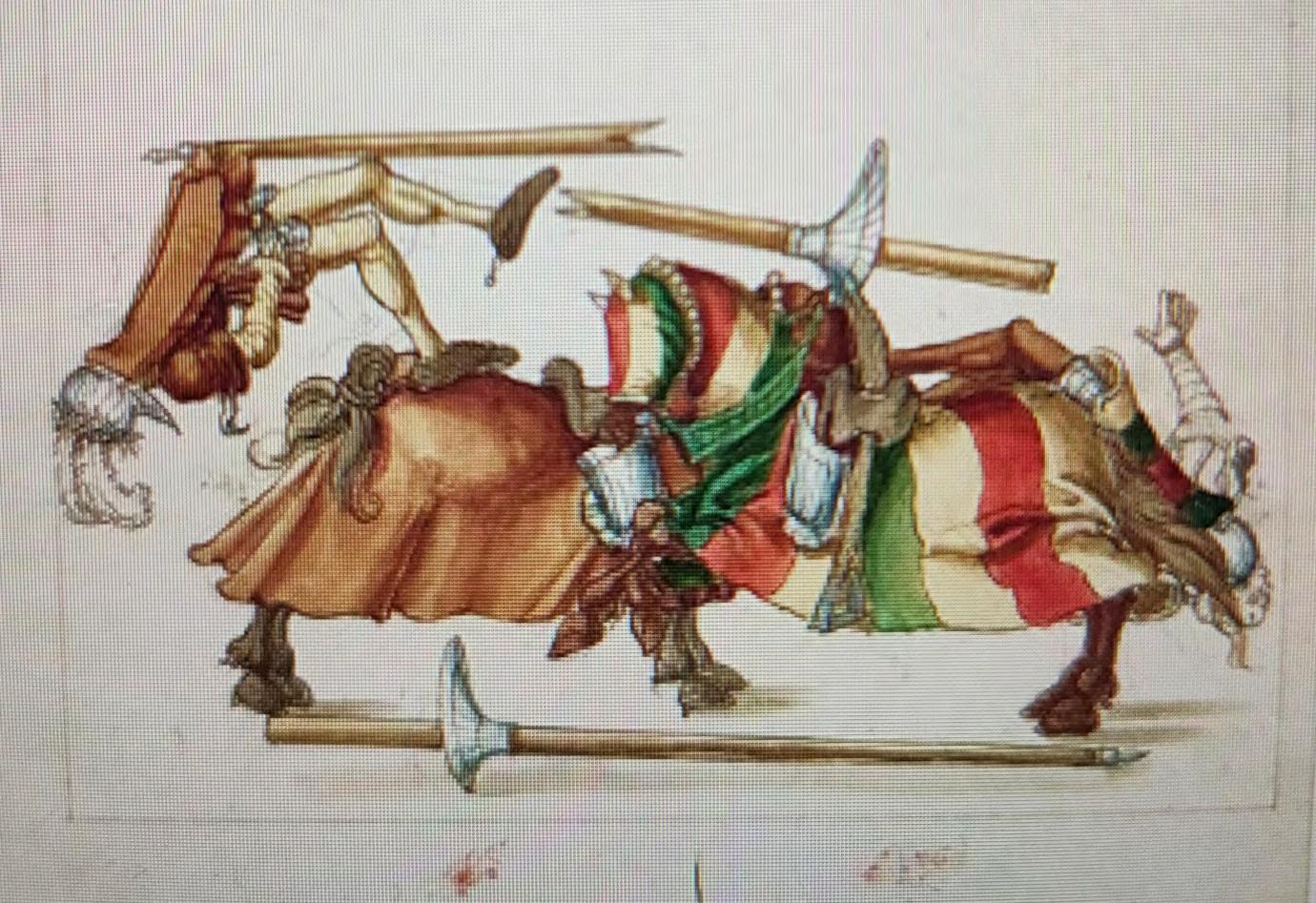

Joust of War between Christoph Lamberger and Freydal (Maximilian himself), from a plate in ‘Freydal’, circa 1512-15. Note the separately worn Dilgen remaining suspended in place.

Another example from the same work of 1512-15.

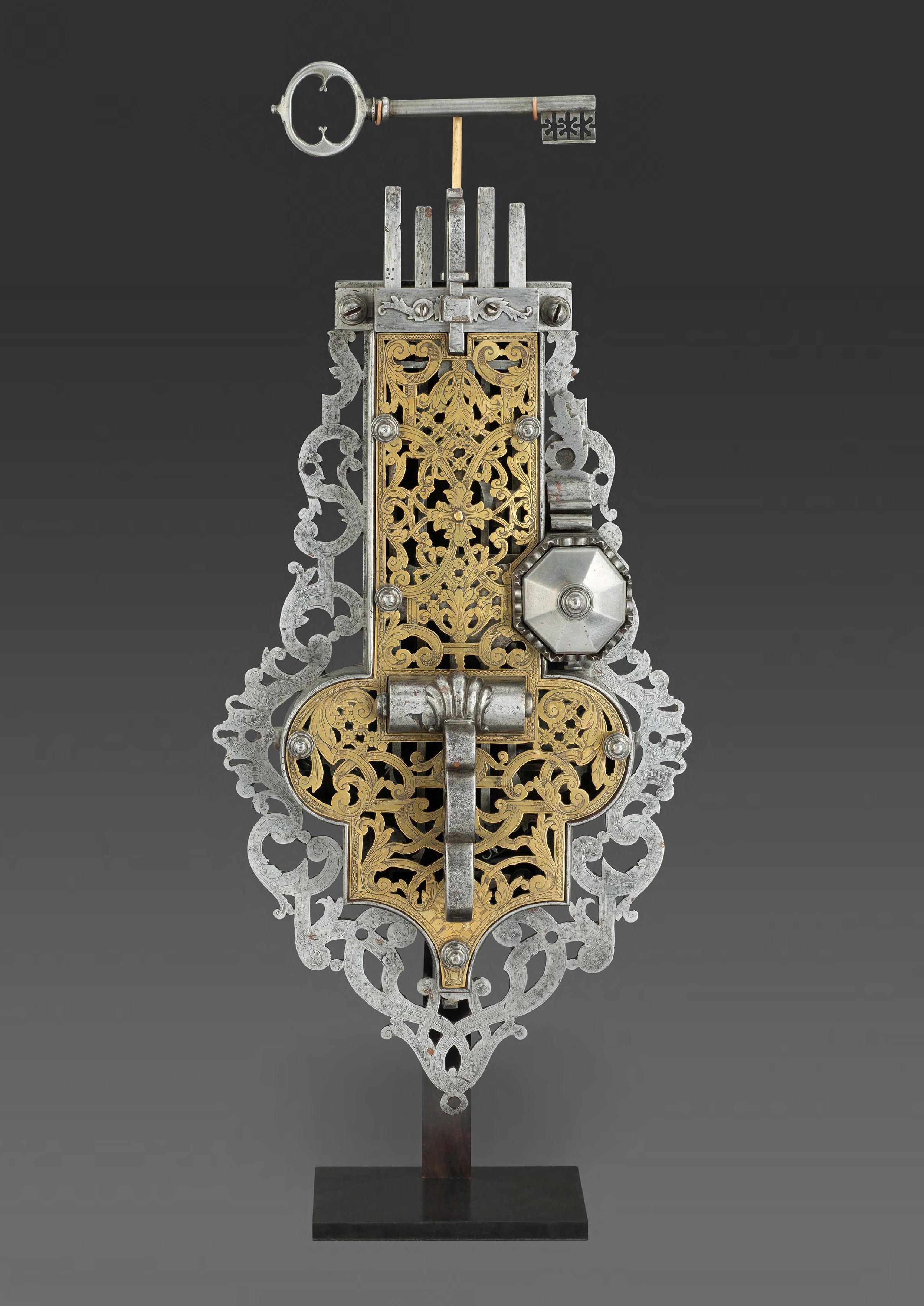

By about 1490-1500 the relatively flat Streiftartsche had evolved to a shape better fitting the thigh and the knee, and in this ergonomic form were referred to as ‘Dilgen’ (sing. Dilge) within the early 16th century.

As previously, Dilgen such as the present pair were constructed to be suspended on either side of the saddle, but now to sit broadly over the thighs and knees. As such, the more compact size and shape of the present examples represent the optimum point of development. They were not elements of body armour attached to the rider; as if verification of this were needed, illustrations in contemporary ‘tournament books’ (the superb miniatures of Maximilian’s ‘Freydal’ for example) include multiple dramatic records of competitors in one or other form of the Rennen hurled rearward out of the saddle by the impact of an opponent’s lance, while the Dilgen remain in their correctly suspended position at the saddle.

It would appear that surviving examples of Dilgen are limited to those with historic connection to the Habsburg imperial court, seat of the foremost exponent and patron of the tournament, the Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519, King of the Romans from 1486, Holy Roman Emperor from 1508).

Several pairs of Dilgen compare closely with the pair under present discussion, sharing not only their unique ergonomic form but their embossed and fluted decoration also.

A fine example is the pair forming a part of the Rennzeug made in about 1494, displayed in the Royal Armouries Leeds (II. 167 n-m). This pair belong to one of several such armours with Dilgen known to have been commissioned by the Emperor Maximilian I for his own use and that of his guests. Originally in the former imperial collection, this armour and its Dilgen were deaccessioned by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in about 1935. The complete set was subsequently included in an auction held by Galerie Fischer in Zurich and acquired by William Randolf Hearst; the armour was in turn purchased by the Royal Armouries in 1952.

Both this and the present pair are decorated immediately beneath the upper border with an embossed inverted arc of three flutes, from below which radiates a so-called ‘wolf’s teeth’ pattern, popular among the court armourers of Augsburg and Innsbruck in the late 15th and early 16th century.

The present examples are additionally embossed with a six-pointed star over the knee. This may be either a decorative feature, or plausibly the heraldic emblem central to the coat-of-arms of the original owner.

The borders surrounding the present Dilgen are studded with brass-capped lining rivets and retain fragments of the original lining-straps on the insides.

Another pair, ascribed to Southern Germany, circa 1500, is in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (B 174c). Closely related to the present pair and to the pair in the Royal Armouries, these are again characterised by their pronounced ergonomic shape, sharing again the broad band of ‘wolf’s teeth’ ornament embossed across the central area. A particular feature of these, seen also in the present Dilgen, is the strong protective raised, incised cabled flange which is rivetted about the upper edge of the thigh. This would presumably have been intended to prevent a stray lance point from deflecting up the thigh.

Another pair, also in Vienna (B 16a) and also comparable to the present examples are ascribed to circa 1515, made by Konrad Seusenhofer, founder of the imperial armour workshops in Innsbruck in 1504.

Among a range of other armour of this brief period which includes this distinctive ‘wolf’s teeth’ style of embossed ornament is the visor of a close helmet for a boy, possibly Innsbruck, circa 1505, in The Philadelphia Museum of Art (1977- 167-81); the horse armour of Georg von Stubenberg-Wurmberg, attributed to the Hapsburg court armourer Konrad Seusenhofer of Innsbruck, circa 1505-10, removed to the Landeszueghaus collection in Graz (57.1); and the Innsbruck globose cuirass, circa 1510, again in the Royal Armouries, Leeds (III. 1246).

As far as can reasonably be determined, the present pair are possibly unique in private ownership, surviving pieces being understandably depleted by successive fashionable developments in the joust, ultimately leading to the redundancy of this type of armour and it being discarded from noble armouries throughout the territories of The Holy Roman Empire. One known exception exists within the historic von Matsch / von Trapp armoury at Schloss Churburg in the Tyrol, in the form of a pair of Streiftartschen, mentioned previously as the forerunners of Dilgen, made by the Habsburg court armourer Adrian Treitz (Treytz) of Mülau, near Innsbruck.

One of the pair of dilgen in Vienna (B 174c) referenced above.

A Flemish Shaffron

c. 1520 – 30

Belgium, Flanders. Steel, brass

67 cm × 30 cm / 26.4 in × 11.8 in

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Europe

This shaffron is of a distinctively Flemish fashion of about 1520-30. It relates to, and may possibly derive from, a large quantity of Flemish horse armour imported into England in the time of King Henry VIII and stored in the Tower of London Armouries in readiness for its use by his cavalry.

In the late 15th and early 16th centuries Flanders rivalled Northern Italy and Southern Germany as a major centre for European armour-production. Although the armourers of Flanders like those of much of Europe looked to Northern Italy and Milan in particular, to provide the models for their own styles, they tended to adapt those models to Northern European tastes by introducing forms and decorative details that imbued them with a recognisable character of their own.

The earliest surviving shaffron to which a Flemish origin can confidently be assigned is one in the Real Armeria, Madrid (cat. no. A. 11), associated with an armour of the Flemish-born Philip I, “the Handsome”, King of Castile (1478-1504-1506), which bears the mark of an unidentified armourer known to have worked for him in Flanders. The shaffron, moreover, bears engraved decoration from the hand of Paul van Vrelant of Brussels, which was perhaps applied in 1505 when he was paid for the decoration of various items of equestrian equipment for the King. Very close to it in style, and therefore presumably in date as well, is an undecorated shaffron in the same collection (cat. no. F, 110).

Of a somewhat later date than the latter but once again decorated by van Vrelant of Brussels are further two shaffrons in the Real Armeria, Madrid (cat. nos F. 111-12), which were almost certainly among six that van Vrelant was paid for decorating in 1520 for the Emperor Charles V, son of Philip the Handsome, and like the latter, born in Flanders.

Very similar in style to them are two undecorated shaffrons in the Real Armeria, Madrid, each forming part of a complete horse armour bearing the mark of the Flemish armourer Guillem Margot, who is recorded a having worked between 1494 and 1530 for Philip the Handsome, Charles V and the latter’s younger brother Archduke Ferdinand, who for a time served as governor of the Burgundian Low Countries. Records show that horse armours formed a significant part of Guillem Margot’s output.

Two further horse armours bearing Margot’s mark are among the remains of the personal armoury of King Henry VIII of England, preserved in the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London. Both are decorated by Paul van Vreland. One of them may have formed part of a gift of armour made to the King by the Emperor Maximilian I in 1514, while the other appears to have been decorated by van Vreland in England between 1514, when he took up employment with the King, and 1519.

Flemish armour was evidently much appreciated in England around that time, as is shown by the fact that in 1511 King Henry brought over to the country to work for him in a royal workshop that he set up in his Palace of Greenwich, two armourers from Brussels: Copyn de Watt and Peter Fevers.

However, much munition armour of Flemish make was also imported into England in Henry’s time, including substantial quantities of horse armour that are still seen in part among the remains of the former national arsenal of the Tower of London, and are now distributed between there, the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, Windsor Castle and Hampton Court. Shaffrons form a significant part of those remains.

Viewed collectively, they show a clear relationship in both form and detail to the Flemish examples in Madrid discussed above. Persistent among their features are the boxing of their sides, and the decoration of those sides and the ear-defences with cascaded fluting of the kind seen on the shaffron under discussion. Although some of the Henrician shaffrons are likely from their close resemblance to the Philip the Handsome example of c. 1505 discussed above to date from the earliest years of the King’s reign (1509-47), others of a bolder form and with boldly roped edges clearly date from a later part of it.

What appears to be the latest of them, inv. no. VI. 35 in the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, is also that which most closely resembles the example under discussion. It, like the latter is boxed at each side, decorated over the nose with a roped medial ridge, fitted with separate defences for the ears, the nose, and formerly the eyes, and is ornamented at the brow with a small, radially fluted roundel. Even more similar to the example under discussion is one formerly in the collections of the Baron C. A. de Cosson at Pyrcroft, Chertsey, Surrey, and Sir Edward Barry at Ockwells Manor, Bray, Berkshire. It shows not only the same cascaded fluting on its sides and ear-defences, but also the same very distinctive fluted decoration on its prominent nose-defence. Exhibiting many of these same features is a shaffron formerly in the collection of Alfred W. Cox of Glendoick, Perthshire. The fact that both the Barry and Cox shaffrons had an English provenance raises the very real possibility that they may have been sold from the Tower of London’s overcrowded storerooms - often simply as old iron – in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is not impossible that the markedly similar shaffrons in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, and the Museo Civico Medievale di Bologna might have shared that origin. Aside from having fixed rather than separately applied eye-defences, the Bologna example is almost the twin of the example under discussion.

An Important Armour attributed to the Habsburg Court

Armourer Desiderius Helmschmid and the etcher Jörg Sorg

dated 1545

Germany, Augsburg. Steel, gold, copper alloy, leather. The gorget, shoulder plates and lance-rest later. Minor restorations, including refreshing to the etching and gilding.

PROVENANCE

Private Collection, Florence, Italy

The Charles Hummel collection, Genoa

Included in the subsequent auction sale of the collection in Gênes (Genoa), lot 6, pl. XIV, May 1908

Sold Gallerie Fischer, Lucerne, August 18-20th 1931

Purchased by Hans von Schulthess (1885-1951), Schloss Au, n. Zurich, likely acquired at the 1931 Gallerie Fischer sale

Included in the private sale of the von Schulthess Collection by his heirs, 2008

Included in the private sale of the von Schulthess Collection by his heirs, 2008. This armour is likely the earliest known collaboration between Desiderius Helmschmid, court armourer to the Emperor Charles V, and the etcher Jörg (II) Sorg, acclaimed masters of their respective disciplines working in Augsburg in the 16th century. The armour is etched on the helmet visor with the date 1545, the year of its completion, which pre-dates by three years the previously held start of their collaboration.

Desiderius Helmschmid (1513-79) was a member of a dynastic family of armourers working with distinction in Augsburg and Vienna, in the service of the Habsburg emperors and the nobility of their courts. His great-grandfather, Jörg the elder, was armourer to the Emperors Friedrichs III and Maximilian I. His grandfather, Lorenz, inherited the latter appointment and his father, Koloman, was in turn armourer to the Emperor Charles V. Katharina (1508-53), the sister of Desiderius, married the etcher Jörg Sorg the elder in 1520, and it was his son of the same name who later worked in association with Desiderius.

LITERATURE

Mario Scalini, ‘Autography problems and study of Renaissance armours: additions to the Helmschmid family and Mattäus Frauenpreiss catalogues’, p.66, fig.9, in A farewell to Arms, studies on the history of Arms and Armour, Legermuseum, Delft, 2004

The Sorg family of etchers and painters (maler ) formed a similar artisanal dynasty, beginning in 1457. Jörg the elder (1481-1565) and his wife Katharina, were the parents of Jörg the younger (1522-1603), who is recorded as a Master etcher in 1548.

Another and equally valid route has been study of the armours known to have been decorated by Jörg Sorg, and more specifically those for which Sorg was engaged by Helmschmid to etch. In examining Sorg’s decorative treatment of these we have made comparisons with the etching of the present armour, particularly those armours etched with the ‘luntte’ or ‘schuppen und ranken’ pattern which dominates both the present armour and a small number of others acknowledged to be Sorg’s work.

In looking at Sorg’s etching we are assisted by his own ‘Harnisch-Musterbuch’, his personal finely illustrated record of the armours he worked on, detailing in his hand also who they were made for and importantly to us, providing the names of the master armourers who made them. Sorg’s records clearly reveal the measure of his ability, in that parallel with Desiderius Helmschmid he was also employed by many of the foremost armourers of the day.

The original Musterbuch codex is lodged in the Württembergischen Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart, but fortunately the full series of superb watercolour drawings and Sorg’s accompanying notes have been reproduced in a volume published in 1980, together with modern scholarly commentary. Less convenient, given that the present armour was completed in 1545, is that Sorg’s record begins only in 1548, the year in which he is recorded as becoming a Master etcher.

This chronological gap is first bridged by looking at Sorg’s record of an armour made by Hans Luzenberger in 1550, for a member of the Spanish Habsburg court (see MS. fol. 11 v, plate 40). This gives a clear image of the lunette pattern, complete with the small scrollwork designs which individually fill the nodules in the design, and which form part of the lunette pattern on the present armour.

Further comparison is offered by Sorg of a garniture comprising four armour designs, successively for the foot tournament, the tilt at the barrier and two field armours. This elaborate garniture was made by Helmschmid in 1552, for Ludwig Ungnad von Weissenwolf auf Sunegg, Freiherr zu Sanegck, a senior officer of the Habsburg court, active 154266 (see MS. fol. 22 v 23 and 24, number 80). With the exception of the tilt armour, the three remaining manuscript illustrations display the lunette pattern as being closely related to the overall corresponding

design on the present armour, albeit lacking the augmentation of the small scrollwork designs and projecting sprigs which are an additional etched detail of the present armour. Given the minute scale of this last feature its omission may perhaps have been an oversight on the part of the manuscript draughtsman.

A survey of surviving armour constructed and etched in the manner of Helmschmid and Sorg includes several detached elements in institutional collections. The first of these is a detached couter (elbow defence) in the von Kienbusch Collection of The Philadelphia Museum of Art (cat.no. 190). This belongs to the same armour as the cuff of a right gauntlet and the front and rear lame of a gorget in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (29.158. 329 and 389).

A strong example is a light field armour in The John Woodman Higgins Armory, Worcester, Massachusetts (JWHA 2582). This is compared in the catalogue to the work of Desiderius Helmschmid and Jörg Sorg, and once again conforms quite closely to the embossed and etched decoration of the present armour; the catalogue draws attention also to a matching left cuisse (thigh defence) in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The Higgins catalogue entry further invites comparison with the ‘Mühlberg’ armour of Charles V, the exchange close helmet included in its garniture has particular relevance to present armour.

The attribution of the present armour to Helmschmid is made based on close similarities between its construction style and constructional characteristics in Helmschmid’s acknowledged works. Two elements of the present armour offer the most compelling evidence: these are the close helmet, and the specific construction of its visor and upper-bevor, and the concealed lance-rest mounted on the breastplate.

In terms of its construction, the present helmet compares particularly closely with the helmet made by Desiderius Helmschmid as a part of the Mühlberg garniture of Charles V. Below the sophisticated double visor, a spring-loaded system of pierced slotted plates shoots rearward to reveal corresponding ventilation slots now open on the left- and right-hand sides of the upper-bevor. Moving on internal spring-catches left and right, the plates are released from their forward closed position by the touch of a projecting button on either side. This ingenious device is extremely rare, and quite possibly exists on no other helmets save the examples of the present armour and the Mühlberg, each a very close constructional, near-twinned match throughout.

The lance-rest on the breastplate of the present armour is again a very rarely seen device of great ingenuity. The arm of the rest is straight in plan and may be pushed back into the breast-plate to form a concealed fit entirely flush with the now streamlined armour surface. The release spring-catch is formed as a rectangular button beneath, neatly flush-fitting.

This device exists on the ‘von Cleve’ half-armour of Charles V, made by Desiderius Helmschmid in 1543; the armour is preserved in the Leibrüstkammer of the Kunsthisorisches Museum, Vienna, the former imperial collection (A 546). The concealed lance-rest was an invention of Koloman Helmschmid and is not known on armour outside of a minority of those produced by Koloman and Desiderius.

On 24th April 1547 the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor led his army to a decisive victory over the Princes of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League near the town of Mühlberg, in the Electorate of Saxony. In his victory Charles V crushed the Protestant opposition and the German lands were his. Such was the significance

of this his most prized victory, that the artist Titian was commissioned to paint an iconic equestrian portrait of the emperor wearing the light cavalry armour of embossed, etched and gilt plate which he had worn during the campaign. This armour, now widely recognised through Titian’s painting, belongs to a magnificent field garniture made by Desiderius Helmschmid, completed in 1544 and so dated. Titian’s portrait of 1548 provides a faithful detailed record of this Helmschmid armour, its embossed and etched decoration provides a clear reflection of the Habsburg court taste of this period (Museo Nacional del Prado, inv. no. P-410).

Known today as the ‘Mühlberg’ garniture, the halflength light armour which formed the core of the garniture, together with most of the constituent exchange pieces, are preserved in the Royal Armoury, Madrid (Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, A. 165, A. 184 and A. 182). Included within the surviving garniture is its close helmet, a sophisticated construction in all respects, the current relevance of which has been the subject of our brief commentary above. Faithful records of this helmet exist in two further portraits of Charles V, painted in 1599 and 1608 (though repeatedly giving the armour wrongly as black and gilt), each by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, after Titian (Patrimonio Nacional. El Escorial, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo).

The Mühlberg close helmet also appears among a limited number of pieces from the garniture which were recorded in a page of the Inventario Illuminado of the Royal Armoury, the pictorial inventory of the arms and armour of Charles V. The Mühlberg close helmet was also included in the important exhibition of royal armour and portraits from Imperial Spain, ‘The Art of Power’, 2009, cat. no. 42, pp.165-167, 222, figs. 28, 29, 31.

A Rare Breastplate for Foot or Light

Calvary Armour

c. 1550 – 60

Northern Italy, probably Brescia. Steel, copper alloy, gold

41.5 cm × 35 cm / 16.3 in × 13.7 in

PROVENANCE

Possibly included in the removal of arms and armour from the armoury of The Order of the Knights of St. John, Valetta, Malta, during either the French occupation of 1798-1800, or when under British governance within the first half of the 19 th century.

This breastplate was certainly made for wear by an officer of an elite body of troops, possibly those of The Order of the Knights of St. John, or alternatively the armed retinue of a high-ranking nobleman, or perhaps those forming a city guard.

The elegant elongated construction typifies the long-waisted form which was fashionable during the mid-16th century period of armour production in Milan, Brescia and Mantua. With the obvious exception of the gilded relief decoration, the outer surface is entirely blued, the finish now naturally lightly oxidised by age; it is not difficult, however, to picture the splendour of this armour within its period of use. Characteristic of the type, the construction comprises a main plate formed with a ridge running over the full height of the median and continuing over an over-lapping broad waist plate. The edges at the neck-opening and arm-gussets are finished with boldly cabled turns and the outward flange of the waist plate carries its original skirt of two lames.

Decorative embossed scrollwork sweeps downward in a symmetrical pattern from the upper corners to below the neck, and in the Italian style of the period this is balanced by its repetition over the waist plate.

The linear scrolls of the embossed ornament are conspicuous in their broad plain surfaces and bold graceful curves, in these respects the embossed work is comparable, for example, with the ornament embossed over the sides of an Italian burgonet skull of the same period, in the Stibbert Museum, Florence. The stylised fleur-de-lys motif incorporated in the embossed design is most likely the badge of a body of troops also (see Lionello Boccia, Il Museo Stibbert, Florence, 1975, cat. no. 64, fig. 65A).

Placed on the present breastplate as if suspended from the embossed scrolls is an heraldic Cross Moline, serving both to identify the allegiance of the wearer and to act as a Christian talisman. Similarly medieval in their origin were the crosses worn by the early Knights Templar and by the Knights Hospitaller, the latter properly titled ‘The Order of the Knights Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem’.

With its straight parallel-sided arms and small outwardly turned pairs of points, the Cross Moline is the design from which the better-known Maltese Cross developed and which was subsequently adopted as the badge of the Order of the Knights of St. John.

Within the immediate decades following their move to Malta in 1530, related tomb effigies, frescoes and portraiture of the period reveal that the Knights of St. John were initially identified by their medieval Cross in Ordinary rather than by the Maltese Cross, which only latterly became synonymous with this knightly order. This appears to have remained the case until circa 1550, beginning with the gradual introduction of the Moline type, but used in parallel with the Cross in Ordinary. It is only within the period 1570-1600 that the fully developed Maltese cross becomes frequently observed on the breastplates, red fabric tabards, shields and ceremonial cloaks of the knights.

Two late 16th century examples of munition breastplates bearing the Cross Moline (each considerably less elaborate than this present example), are preserved in the Royal Armouries Collections, Leeds (III.905, III.1327). A further two examples, of the same period, ascribed to possible Brescian origin and each embossed with a pendant Maltese Cross are in the Odescalchi Collection in the Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia, Rome (inv. 1105 and 1113).

Notable also in this discussion is a portrait in the Palace of Hampton Court, London, by Jacopo Robusti, called ‘Tinteretto’ (1518-94). The subject is a Knight of St. John; suspended from his neck is a Cross Moline, while the cross on his cloak is a Maltese Cross approaching its fully developed form.

A Cavalry Half-Armour

c. 1560 – 70

Northern Italy, probably Brescia; North European lesser additions. Iron alloy (steel), copper alloy (brass), leather 171 cm × 76 cm × 35 cm / 67.3 in × 30 in × 13.7 in

This armour is a good representation of the type produced in the city of Brescia within the third quarter of the 16th century for the use of Italian heavy cavalry armed with lances. The close helmet in particular compares closely with the helmets of the two cavalry armours of this period among the hoard of Lombardic armour in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie di Curtatone, now removed to the Francesco Gonzaga Museum, Mantua (cat. nos. B 12 and B 13).

The skulls of these generously proportioned helmets are further characterised by a highly pronounced but slender comb, rearward-swept over the crown. Characteristic also is the visor, formed with horizontal narrow sights with a narrow medial divide and extending centrally to form a pointed prow. The lower edge of the visor fits flush into the substantial upperbevor, aligning the sights exactly with its upper edge. The upper-bevor naturally forms the body of the prow and is invariably pierced with a single circular group of small circular breathing holes on the right side only, away from the point of an opponent’s lance.

The breastplate is again characteristic of cavalry armours produced in Brescia within the period. The V-shape became accentuated by 1570, as evidenced here. This style being referred to in English as ‘Peascod’; the elegance of the shape belies its important function, although its influence will be recognised in the extremes of male fashion portrayed in art over the remainder of the century.

In terms of functionality, the shape was conceived in the defence of the wearer’s left torso, it being essential to prevent the catastrophic injury resulting from an opponent’s lance slipping into the wearer’s left armpit. The effective defence was to snap the opposing lance on impact, a possibility only if the lance impacted the breastplate at the exact angle of 90 degrees. To enable this, the rider had to lean forward at 30 degrees, in this way presenting a vertical surface to the offensive lance tip. The lower part of the breastplate had to be slanted forward, creating what we refer to as the ‘Peascod’ shape.

The shoulder defences (pauldrons) are correctly asymmetric, the configuration necessary to accommodate the lance when couched beneath the right shoulder. The larger plate of the opposing left pauldron provides evidence that this pair of pauldrons had likely seen service in the joust, it shows a plugged aperture originally intended for a bolt attaching a large reinforcing piece specifically for wear in the joust (buffa da torneo). This alternative sporting role for a field armour was typical among Italian heavy cavalry armours of this period.

A further notable feature within the arm defences is bifurcated design embossed on the bracelet couters (elbow defences), briefly a fashion in Brescian armour of the period.

A Suite of Magnificent Armour for Man and Horse,

Etched and Gilt in the Lombard Fashion

Late 16th Century

The Armour dating circa 1580-85 and possibly made for Don Carlos d’Aragona y Tagliavia, Duke of Terranova, Prince of Castelbeltrán, Count of Castelvetrano and Spanish Royal Governor of Milan (the helmet and cuisses both of a contemporary late 16 th century armour.)

The Horse Armour and the Shield dating circa 1560 from a garniture made for Emanuel Filibert, The Duke of Savoy.

PROVENANCE OF THE ARMOR:

The Rt. Hon. Lt. Col. Charles Seale Hayne, M.P. (d.1903), of Fuge House and Kingwear Castle, Devon. To F. Robert, Paris, 1904.

Acquired by William Waldorf Astor, later 1st Viscount Astor; thence by descent through the family.

Sold Sotheby’s London, The Hever Castle Collection, 5th May 1983, lot 54 (including associated elements now not present).

Northern Italy, Milanese workshops. Steel, gold, copper alloy, period textile forming the bridle, leather.

Height of the suite: 244 cm / 96 in Overall installation length of the suite (nose to tail): 272 cm / 107 in Maximum width of the suite (outside of stirrup to outside of stirrup): 107 cm / 42 in

PROVENANCE OF THE HORSE ARMOUR AND SHIELD:

By descent through the Ducal House of Savoy to the Royal Sardinia-Piedmont line.

These pieces of armour were dispersed, together with other constituent pieces, from the extensive garniture made for Duke Emanuel Filibert, the dispersal almost certainly occurring prior to 1840 and most likely prior to the establishment of the new royal armoury in Turin in 1837.

Acquired by Count Hector de Economos, Paris.

Included in the purchase of the Economos collection in its entirety by William Randolph Hearst, 1924.

William Randolph Hearst, as Anonymous sale, Galerie Fischer, Luzern, 29 November 1972, lot 71.

Acquired by a private collection, USA.

Anonymous sale, Christie’s, London, 12 December, 1997.

Almost certainly prior to this armour being acquired by William Astor, circa 1904/5, the cuisses and poleyns defending, respectively, the thighs and knees, were added. These are again contemporaneous with the arm defences and main body of the armour. These pieces have in common with the greater part a similar close-set arrangement of etched bands with black linear borders, but the contained ornament differs in being largely formed of vertical designs of welldrawn trophies-of-war.

The attribution to Don Carlos has only recently been determined by Italian scholarship, and we thank Mario Scalini for his work on this, through the interpretation of an etched palm branch and crown motif, a predominant feature recurring throughout the etched bands of ornament over the core elements of the armour. This palm motif has been identified as the impresa (personal emblem) of Don Carlos, which is carved in relief on the tomb of Don Carlos, in the church of San Domenico in Castelvetrano, Sicily.

Essential in the consideration of the provenance of this armour is that imprese were the informal emblems chosen by individual members of the Italianate nobility. Unlike a family coat-of-arms, they were not hereditary. In the case of Don Carlos, the palm is derived from the Tagliavia palm tree device found within his family arms, which had been quartered with those of Aragona in 1522 (upon the union by marriage with the niece of Frederico II, King of Sicily).

An additional motif recurring in conjunction with the palm on the armour discussed, appears to be a representation of the bulb-like Mandrake fruit. It has been suggested that this may have been included for its talismanic qualities.

The repeated incorporation of the Tagliavia impresa etched on the present armour is strikingly paralleled in one of the finest surviving armours made by Pompeo della Cesa. In a similar recurring manner to the armour of Don Carlos, this example carries both the motto and the ‘three rings’ impresa of the Borromeo family dispersed throughout the decorative scheme.

The helmet from the Borromeo armour is separately preserved in the Poldi Pezzoli museum, Milan, while the body of the armour is in the Stibbert Collection in Florence.

The armoured figure is superbly mounted for display, complemented by the shield and its matching elements of horse armour from an important etched garniture made, circa 1560, for Emanuel Filibert, Duke of Savoy, 1528-80.This situation came to an abrupt end, however, on 10th August in that year, with the decisive route of the French by Emanuel Filibert’s Habsburg army at the battle of San Quintino. Following both this defeat and yet further military failures the majority of French troops left Piedmont, to pursue another ill-fated campaign in the Hautede-France. Subsequently, a succession of French defeats in Piedmont, again at the hands of Emanuel Filibert, heralded the end of the twelve-year war with Habsburg Spain.

The consequential Peace of Cateau Cambrésis in 1559 saw not only the return to Savoy of almost all of its hereditary lands but it additionally gave Emanuel Filibert a bride, Margherita of Valois, sister of Henry II, King of France (together with substantial dowry). Anecdotally, the elaborate festivities that accompanied the marriage in July included a week of knightly tournaments, and it was while jousting on 30th June that Henry II was mortally wounded, dying within a few hours of the marriage.

With the restitution of Savoy completed under the terms of the marriage, Emanuel Filibert then handed the government of the Spanish Netherlands to a daughter of Charles V, to take up residence in Nice and commence the reconstruction of the Savoyard Duchy. In the course of his pursuit of the Swiss Savoyard lands a religious war now erupted in Piedmont, the complex political outcome of which was settled in 1561 by Emanuel Filibert’s skills as a statesman rather than as a soldier. He next gave his attention to agrarian reform in the duchy, together with the reconstruction of mining and commerce, to be followed by an extensive re-building and reorganisation of the Savoyard army and the birth of a naval force also.

Thus re-equipped, the Savoyard Duchy under Emanuel Filibert became a new force in the alliance of the Holy Roman Empire, rendering valued onward assistance in the eternal fight against a Turkish conquest of the Mediterranean.

bronze equestrian statue

A

of Emanuel Filibert, Duke of Savoy, is in the Piazza San Carlo, Turin.

THE HORSE ARMOUR,

SHIELD and EMANUEL FILIBERT, THE DUKE OF SAVOY

In the context of the history of 16th century Northern Italy, Emanuel Filibert the duke was a singularly influential and pivotal figure. He provided both the blunt militaristic force and the diplomatic finesse necessary for the restitution of the Savoyard Duchy, the essential strategic buffer between longstanding French ambition and access to the Spanish Habsburg lands within the Italian peninsula. Through his prowess and courage as a general in the army of The Holy Roman Empire, but in particular for the wresting of his paternal duchy back from the invasive French, Emanuel Filibert became known in his lifetime as ‘Testa di Ferro’ (‘Iron Head’).

Armour belonging to this garniture is shown worn by Emanuel Filibert in a portrait of circa 1565, by Giacomo Vighi, called l’Argenta (d.1573), at the Galleria Sabauda, Turin. The majority of the surviving parts of this garniture remain in the Royal Armoury in Turin (inv. nos. B4- C86- C151- C227/228- E12), other pieces having been dispersed prior to 1840, in which year it is recorded that a helmet and a breastplate were in the possession, respectively, of the Conte S. Martino La Motta and the Marchese Claudio d’Aix. The latter, a distinguished general, was aide-de-camp to King Carlo Alberto of Sardinia and related to the first director of the newly established royal armoury, Vittorio Seyssel d’Aix. It is reasonable therefore to suggest that these two pieces were royal gifts. By extension, the present shield and horse armour from this garniture may have been dispersed from the royal collection under similar circumstances.

The present elements of horse armour from the historic garniture comprise a half-shaffron complete with its poll-plate, and the original leather-covered saddle-tree mounted with four plates over the bow and its rear cantle defended by a pair of large plates. The original matching circular shield from the garniture provides a complementary bridge with the armoured figure.

These pieces are preserved in superb condition throughout, with little evidence of wear. The matching etched and gilt pattern is clearly identical to the etched and gilt armour detailed in Emanuel Filibert’s portrait. The etched pattern takes the form of a series of broad bands both radiating across and bordering the bright steel surfaces. The bands are filled with a repeating design of partly-foliated interlaced strapwork, alternating with quadruple loops at intervals, and all on a gilt ground within subsidiary herringbone border ornament.

The shaffron extends down to the upper part of the muzzle, with flanged cut-outs for the eyes, separate riveted ear-guards, tubular brass plume-holder, and bolt for fitting an escutcheon. The poll-plate moves on a hinge at the apex.

The original saddle leather is authentically dressed in rich textile, after the fashion of the period. Its applied plates are retained by screws with prominent rosettelike heads. Both the saddle and the shaffron are painted with the inventory number ‘16’ on the inside.

The shield is of slightly concave form on its inner side, the outer face fitted with an iron acanthus calyx. It retains its original brown velvet lining edged in decorated braid, and additionally its original leather braces, which are partly velvet-covered.

To this historic ensemble are added a pair of late 16th century stirrups damascened with fine gold ornament in the North Italian taste, together with a pair of rowel-spurs also dating from the 16th century and similarly damascened in gold.

Elements of a contemporary equestrian garniture (including a half-shaffron, armoured saddle and shield) are etched in an almost identical pattern to the corresponding pieces under discussion; made for capitano Valerio Corvino Zacchei of Spoleto, this smaller garniture remains in the Royal Armoury, Turin (nos. B7- E38- F23).

As Prince of Piedmont, Emanuel Filibert acceded to the title Duke of Savoy upon the death of his father, Duke Carlo III, in 1553. Under the weak tenure of Carlo III, Turin and the majority of the Savoyard lands in Piedmont had since 1536 been annexed by France. Thus, with no option other than the church, in 1545 at the age of seventeen Emanuel Filibert had embarked on a military career, in the service of his great-uncle, the Emperor Charles V. From this beginning he would rise quickly to become both a highly accomplished field commander and statesman, and ultimately the much-acclaimed redeemer of the Savoyard lands from French occupation.

As a soldier Emanuel Filibert engaged with distinction first in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546-7, thereafter continuing in the service of Charles V in support of his son, the Habsburg Infante Filippo (later Philip II of Spain), fighting the French in the Habsburg-Valois (or Italian) War which had erupted in 1551. In 1553 Emanuel Filibert was appointed lieutenant-general and Governor of Flanders, in supreme command of the imperial army there. In Savoy meanwhile, France further extended its territorial grasp over the succeeding two years, and subsequent efforts by the new Spanish Governor of Lombardy to reverse the position achieved little.

A brief truce was followed by the re-commencement of the ever-worsening attrition in Piedmont in 1557. This situation came to an abrupt end, however, on 10th August in that year, with the decisive route of the French by Emanuel Filibert’s Habsburg army at the battle of San Quintino. Following both this defeat and yet further military failures the majority of French troops left Piedmont, to pursue another ill-fated campaign in the Haute-de-France. Subsequently, a succession of French defeats in Piedmont, again at the hands of Emanuel Filibert, heralded the end of the twelve-year war with Habsburg Spain.

The consequential Peace of Cateau Cambrésis in 1559 saw not only the return to Savoy of almost all of its hereditary lands but it additionally gave Emanuel Filibert a bride, Margherita of Valois, sister of Henry II, King of France (together with substantial dowry).

Anecdotally, the elaborate festivities that accompanied the marriage in July included a week of knightly tournaments, and it was while jousting on 30 th June that Henry II was mortally wounded, dying within a few hours of the marriage.

With the restitution of Savoy completed under the terms of the marriage, Emanuel Filibert then handed the government of the Spanish Netherlands to a daughter of Charles V, to take up residence in Nice and commence the reconstruction of the Savoyard Duchy. In the course of his pursuit of the Swiss Savoyard lands a religious war now erupted in Piedmont, the complex political outcome of which was settled in 1561 by Emanuel Filibert’s skills as a statesman rather than as a soldier. He next gave his attention to agrarian reform in the duchy, together with the reconstruction of mining and commerce, to be followed by an extensive re-building and reorganisation of the Savoyard army and the birth of a naval force also. Thus re-equipped, the Savoyard Duchy under Emanuel Filibert became a new force in the alliance of the Holy Roman Empire, rendering valued onward assistance in the eternal fight against a Turkish conquest of the Mediterranean.

A bronze equestrian statue in the Piazza San Carlo, Turin, commemorates the life of Emanuel Filibert, Duke of Savoy.

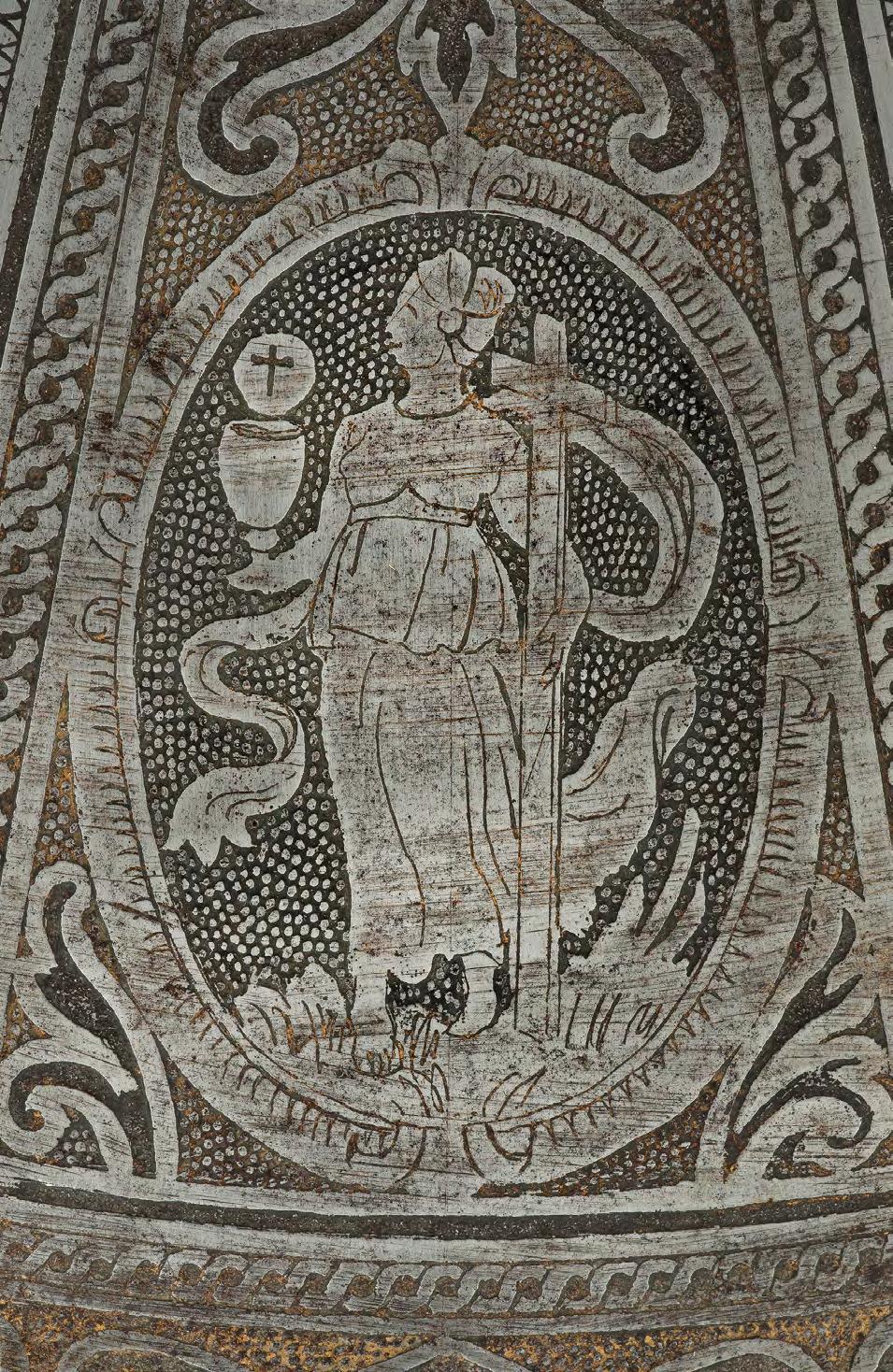

A Very Rare Milanese Etched Breastplate charged with an Armorial Cross, for a Light Cavalry or Foot Service Armour, Inspired by the Etched Motifs of Pompeo della Cesa c. 1580-1600

Italy, Milan. Steel, gold, copper alloy, leather

46 cm × 35 cm / 18 in × 13.7 in

PROVENANCE

Private collection, France

The large cross dominating the face of this breastplate is almost certainly a badge of senior authority associated with a specific body of troops, most likely within the north Italian orbit of power and probably an emblem of the Duchy of Savoy.

The prominence of the cross naturally indicates the level of its significance to the nobleman for whom the armour was made. As such, the cross is an original element of the etcher’s plan, rather than a subsequent addition. The cross is purposefully off-set from centre in order to retain the aesthetic qualities of the etched banded design, a theme conventional to the foremost armourers of Milan, circa 1565-1600. In addition, the arms of the cross are of slightly unequal lengths in order to maintain perspective over the curvature of the plate.

The large scale of this cross (typologically referred to as Greek) differentiates it from the family coats-ofarms and personal devices (imprese) which, on a far smaller scale, are seated generally more discretely within the etched ornament on the finest Milanese armour.

In the absence of a full representation of the tinctures or colours which are fundamental to specific identification in heraldry, it is only possible in the present instance to make informed suppositions in this respect.

Fortunately, the etcher has finished the cross in the white (rather than reproducing any of the patterns used to denote other heraldic colours or materials), the intended representation undoubtedly being a white cross (argent).

While a firm attribution cannot be ascribed, it is most likely that this breastplate belonged to an armour made for a senior commander in the standing army established by Duke Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy (r. 1553-80), famed for his successful armed retrieval of the Savoyard Principality of Piedmont (Piemonte) from the French. The Savoyard army was maintained under his successor, the militaristic Duke Carlo Emanuele di Savoia (r. 1580-1630), repelling in 1589 an offensive by Geneva and other Swiss cantons as members of a French coalition. In the following year Carlo Emanuele sent an army to Provenace in the interests of the Catholic League, the French conflict being temporarily settled by the peace of 1593.

The sole viable alternative attribution for the present breastplate is that it may have been made for a senior officer of the Knights of the Order of St. John, perhaps the commander of an Italian Priory of the Order.

Parallel to the use of the better-known eight-pointed or Maltese cross, which is found on a relatively numerous series of munition breastplates of circa 1560-1600, both the Standard and the Coat-of-arms of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John take the form of a white Greek cross; in common with the white cross of Piedmont-Savoy, this is set against a red ( gules) ground.

Within this period, however, the use of a Greek cross on surviving armour associated with the Knights of St. John appears to be unknown; exceptions to this are limited to art of the period, showing the Greek cross emblazoning the painted shields and tabards of men-at-arms during the era of the Great Siege of 1565. Notable works exemplifying the period use of the Greek cross include the carved tabard on the important tomb effigy of the then Grand Master of the Order, Jean Parisot de Valette (d. 1568), in St. John’s Co-Cathedral, Valletta; this is repeated in d’Aleccio’s fresco battle-scene, in the cathedral also, therein worn by Jean Parisot de Valette and the troops of the Order alike.

Returning to the breastplate under discussion, the etched decoration draws on the conventions and motifs established by the leading armourers active in Milan within the final quarter of the 16th century. This includes the technique of ‘raised etching’, in which the ground alone is etched with acid around the drawn pattern, rather than the standard reverse process in which a pattern is created by the direct application of acid.

The result is the visual strengthening of the pattern, which by this means is projected in low relief. As with much fine Milanese armour of the period, this particular process is well-used in the present instance, giving emphasised structure to the ribbandlike scrolls and cartouches within the banded pattern. These features are made the more striking by being picked-out in black and set against a stippled gilt ground (the present example retains some of this original gilding, the balance now white).

Foremost among the surviving elements of magnificent etched and gilt Milanese armour are those made for the ruling Ducal House of Savoy, and for the nobles of its court and armies. These historic examples are for the greater part preserved in the Royal Armoury, Turin, with other dispersed pieces from these garnitures now mostly in museums across Europe, Britain and the United States. Further important examples are represented in the historic collections of the Royal Armoury, Madrid and in the former Imperial Armouries in Vienna.

The present breastplate is of the form fashionable in the latter decades of the century, drawn-down to an elegant V-shaped point, with turned cabled edges, a single waist lame, and pairs of rivets on brass rosette washers for the shoulder-straps and tasset leathers (expertly replaced).

The absence of a lance-rest is indicative of this breastplate belonging to an armour intended either for light cavalry use, or for foot service in the field or even perhaps the tourney fought at the barrier.

The basis of the fine etched decoration is a characteristic arrangement of bands radiating from the base, with secondary bands across the neck, bordering the sides and continuing over the skirt lame.

The bands are in turn framed throughout by guilloche strips edged by a vacant strip inside and out, and with a blackened single outside line fringed by a spikey neo-dentil pattern. This distinctive border in fact originates in the earlier etching (probably by Ambrosius Gemlich) of armour made for the Habsburg courts in Madrid and Vienna, by Wolfgang Großschedel of Landshut, seen for example in an armet and matching gauntlets of circa 1535-40 (see The Wallace Collection, London, A 164, A 264-5).

In its subsequent Milanese incarnation this border is further developed and found on a number of armours attributed to the workshops of the celebrated armourer Pompeo della Cesa (recorded 1572-93), together with armours ascribed to others of his circle, including the ‘Master of the Castle’, the ‘Master IFP’ and the ‘Master LB of the Globe’.

In the present instance, the ornament within the etched bands comprises a series of cartouches separated by conjoined pairs of opposing C-scrolls, and enhanced by adjacent matching scrollwork flourishes. Typically, the cartouches contain a series of figural vignettes from classical Roman mythology and history. At the centre below the neck, the Goddess Fortuna occupies a cartouche together with a ship and marine monsters, a symbol of her

acts of guidance. At the top of the medial band, the hero Gaius Mucius Scaevola holds his hand into the fire before the Clusium King Lars Porsenna, with a warrior beneath, possibly Mars the God of War. Uppermost within the respective flanking bands are the figures of Marcus Curtius riding into the fiery chasm and Horatius at the bridge. Further male and female classical figures are dispersed among lesser cartouches throughout the design, together with other grotesque emblems of the period.

From the quality of the etched decoration and the likely high status of the man for whom the breastplate was made, it would be reasonable to suggest that this breastplate was possibly the product of one of these workshops referred to above.

Pompeo della Cesa, for example, would have led a large workforce and employed a number of etchers, evidently working in parallel on the many elements of a single garniture of armour. He is also known to have held contracts in cooperation with other Milanese workshops, in order to fulfil large commissions. By these means etched motifs and characteristics favoured by his workshop would be disseminated among the wider Milanese school of decorated armour production.

A Half-Armour of Blued Steel

c. 1580 – 1600

8 Northern Italy, Brescia or Milan. Steel, gold, leather, textile Restoration to the blueing. The leathers and piccadills are modern.

87.5 cm × 72 cm × 39 cm / 34.3 in × 28.3 in × 15.3 in (on mount)

PROVENANCE

Private collection, USA

The half-length configuration of this armour was best suited to foot combat in late 16th century warfare. The new widespread use of military firearms now made agility in the field a defensive requirement, rendering cumbersome leg defences redundant. Italian decorated armours such as this one are frequently identified with the elite small bodies of troops which formed the bodyguard of politically significant noblemen and senior clergy.

The open-faced helmet, properly described in this instance a ‘morione aguzzo’ or pointed morion, was the preferred head defence for field combat by the close of the 16th century. The present example is notably elegant, and richly ornamented with etched and gilt linear bands of warrior figures and trophiesof-war against a ground of scrollwork and mythical grotesques.

The body of the armour is decorated in the more open incised designs which emerged in north Italian armour after about 1560, in parallel with armour decorated with the more often observed bands of etching. Armour decorated with incised flowing symmetrical patterns of foliage and plain broad gilt bands, such as we see here, was also the style worn by the Vatican Papal Guard in the latter decades of the 16th century.

A particularly distinctive feature of the present armour is the Christian iconography incised and gilt over each of the lower-cannons of the arm defences. This would suggest probable wear by a member of a guard, or armed retainer, in the service of a monastic or otherwise religious body.

The design is contained by a gilt framework and centres on a medieval Christian Tau cross (so called because of its resemblance to the Greek letter tau). About the cross are the celestial motifs sometimes present in the renaissance iconography of the Crucifixion. The letters ‘I O H’ are incised above, which may be interpreted as the abbreviated Latin name ‘JOHANNES’ (John), very likely a reference to St. John The Evangelist. A plumed helmet is placed over the top, in the manner of a crest.

A North Italian Etched Circular Shield for Foot Service in the Manner of Pompeo della Cesa

c. 1580 – 90

Italy, Milan

Steel, gold, copper alloy, textile, gilt brocade, leather 58 cm / 22.8 in (diameter)

PROVENANCE

Private collection, United States

The etched decoration on this shield draws compelling parallels among a range of examples of decorated armour attributed to the much-celebrated Milanese armourer Pompeo della Cesa (Chiesa). He was the last of the great Italian armourers to sign with his name the central pieces of his work.

One prominent parallel example is a shield of identical type, attributed to della Cesa circa 158090, preserved in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan (inv. 1740). The most striking similarity between their respective etched patterns is found in the shared radial arrangements of oval figural cartouches, pendant from ribbon-like decorative knotwork, and which develop to form partly foliated scrollwork at either end. The whole design is highlighted in black against a stippled gilt ground and set within guilloche and blackened linear borders. The Poldi Pezzoli shield differs primarily only with the alternative placing of the Virtues in cartouches within the otherwise vacant spaces between the bands, and by the substitution of warrior figures within the radial pattern.

This scroll-ended knotwork (in the later years of della Cesa’s repertoire to also involve addorsed C-scrolls) is a frequently recurring and conspicuous element of his work. Foremost among della Cesa’s armours to include this etched pattern are the magnificent large garnitures which he made for the Dukes of the Royal House of Savoy and other closely related armours for the nobility in their service, much of which are preserved in the Royal Armoury, Turin. A garniture etched in this fashion and made by della Cesa in about 1560-65 for the Duke Emanuele Filiberto (d. 1580) was in part included in a private collection sold in London in 1997; the majority of that garniture remains in Turin (Nos. B4 etc.).

Other than the overall close similarity in the decoration of the two shields discussed here, the detail of their shared examples of scroll- and knotwork possess, in particular, a sufficiently strong resemblance as to suggest a workshop in common. The museum catalogue entry gives further comparative reference to a number of della Cesa’s works of salient significance, including those in the Royal Armoury in Turin and the Royal Armoury in Madrid, all of which have this style of etched design as a common thread (see Lionello G. Boccia and José A. Godoy, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Armeria. I, Milan 1985, cat. no. 341, pl. 370).

Returning to the present shield, the guilloche and linear ornament which borders the radial bands and the band encircling the rim is another distinctive feature of armour attributed to della Cesa and his Milanese followers. One such example, which also includes the ‘toothed’ or dentil pattern of the present shield, exists on the surviving parts of a garniture in the Royal Armoury, Turin (C 14- C73), etched in the manner of Pompeo della Cesa, by the Master L B and an Orb (or Globe), circa 1580-90.

Another very closely comparable example of this type of border pattern is seen on a Milanese morion in the Wallace Collection, London (A 146).

In consideration of the etched oval cartouches on the present shield and of the figures within them, a very close comparison exists in the corresponding features on a part-armour in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (acc. 2001.72a-d). Signed by Pompeo della Cesa, this armour, for either light cavalry or foot service, was made for Vincenzo Luigi di Capua, Prince of Riccia and Count of Altavilla, circa 1595.

In the instances of both the shield and this armour, the oval cartouches and the figures have a naïve character very likely inspired by the same set of pattern engravings. Again, in each example particular note is drawn to the relatively cursory treatment of some of the subject faces, giving an unfinished appearance. The natural conclusion would be that both examples were etched in della Cesa’s workshop, although apparently not by the same hand.

A Fine Cuirassier Three-quarter Armour

in the Manner of the ‘Master MP’ c. 1600 – 1620

Flanders (now Belgium), possibly Brussels. Steel, copper alloy, leather 173 cm × 45 cm / 68 × 17.7 in

PROVENANCE

Sir Guy Francis Laking, Bt. (1875-1919), sold privately within his lifetime. Subsequently included in the sale of Important Specimens of Arms and Armor … from XII to XVII Century, American Art Association, New York, 24th November 1923, lot 254 ($400). Acquired by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Sold Christie’s London, 22nd November 1960, lot 171 (£280) To Basil Robinson, later Keeper of the Department of Metalwork, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1966-72, d. 2005. The Norman Fargo Collection, Sandpoint, Idaho; included in the sale of the collection in 2024

Armours of this three-quarters type were the product of the widespread use of hand firearms on the battlefield, fully established since about 1580. With this shift in the balance of tactical power, the heavy cavalry charge head-on with lances was no longer a force impregnable to infantry. The heavy cavalry were instead required to engage with greater speed and mobility, primarily against opposing horsemen, but even to fight on foot should the need arise. Full-length leg defences were abandoned as both unnecessary and impractical, the emphasis being placed on a bullet-proof breastplate, fully flexible leg defence to the knee only, and a lightergauge helmet no longer needed to defend against the momentum of an on-coming lance.

Now referred to as ‘cuirassiers’ (with their shot-proof cuirasses and remaining the most comprehensively armoured among the cavalry), the heavy cavalry was now armed with a sword, a pair of pistols and over time a short carbine also. When used effectively to sweep down upon an enemy from the flanks, the cuirassiers could sway the course of a battle against superior numbers.

The present armour accords exactly with the Flemish style of cuirassier armour developed within the later phases of the Dutch Eighty Years War, fought throughout Flanders and Brabant, the concluding decades of which merged to become the western element of the pan-European Thirty Years War (161848).

Typically, the breastplate bears the dent of a proving ball. Characteristic also of the higher-quality Flemish cuirassier armours are the scalloped inner edges of the component plates, most visible among the present arm and leg defences, together with the lavish use of brass decorative rivets also displayed here.

Comparable Flemish helmets with two-piece skulls fluted in this angular corrugated manner are in the Musée de l’armée, Paris (H. 150), the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (Z.O. 3288), the Livrustkammaren, Stockholm (2645), The Art Institute of Chicago (2661) and The Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Mass. (17.23.9).

Similar to France but unlike London and the German centres of armour-making, almost all armour produced in Flanders in the late 16th and early 17th century, regardless of superior quality, was completed without having been struck with the maker’s mark, or a city armourers’ guild mark either. This practice has to some extent become a feature in the identification of Flemish work, aside of course from a number of subtle characteristics, together with those more obvious characteristics outlined above.

The present armour certainly ranks among the upper tier of Flemish armour produced within the opening decades of the 17th century. It also provides a rare instance in which it is possible, by stylistic and constructional comparison, to attach a degree of identity to a Flemish armour of this period. On this basis the present armour is judged to be closely related to a distinctive group of high-quality Flemish armours, which in some cases can be identified as the work of the ‘Master M P’. For the most part these armours are now preserved in the Royal Armoury, Madrid (A 380-401, A 414-21), having been purchased in Brussels in 1624 and 1625 for King Philip IV of Spain.

Further details concerning this maker are regrettably negligible, though it is thought very likely that he was a Brussels armourer, with these Madrid armours most probably acquired from his workshop there. It follows also, that the present armour will be the work of an armourer not only working in that city, but also within the close circle of influence of the ‘Master M P’. For exploration of the works of this enigmatic armourer we recommend: Walter J. Karcheski, Jr., ‘Notes on a Newly-Identified Armour by the Flemish Master ‘MP’, in The Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Mass.’, Journal of the Arms and Armour Society, XI, December 1985, pp. 307-14.

In the great period of gothic armour the city of Bruges had been the centre of armour production in Flanders, its leading armourers such as Jean and Martin Rondel being patronised by some of the most eminent ruling

figures across Europe, including Maximilian I both as king and Holy Roman Emperor. Within the same period, the city of Tournai housed 232 armourers, and Brussels also, as the preferred seat of the Dukes of Burgundy, attracted the production of high-quality armour. By the end of the 15th century there were 73 known armourers active in Brussels, with clients within the Burgundy/Habsburg court.

Over time the port of Bruges became silted; as the direct consequence of this the Brabantine city of Antwerp on the river Scheldt, came to prominence as the main Flemish port, as an important centre of international trade, wealth and culture. With this transfer of fortune Antwerp also became renowned for the high-quality of its armour-making. Armour produced in Antwerp reached the zenith of achievement within the third quarter of the 16th century, with the embossed and gilt Mannerist masterpieces of parade armour from the workshop of Elisius Libaerts, and similarly with the etched and gilt luxurious works of the Collaert family.

Antwerp’s fortune died with the regional spread of the Dutch Eighty Years War. In 1576 the city was sacked by Spanish Habsburg troops, during which at least 7,000 of the civilian population were killed.

The production of luxury armour all but ceased throughout Flanders, its armour-making now realigned with the demands of contemporary warfare. The existing mass export of Flemish plain munition armour had been fuelled over much of the second half of the 16th century by the continuous need to equip newly raised forces and mercenaries during the French Wars of Religion. By the outset of the 17th century, the making of superior-quality armour was almost certainly limited to the armourers of Brussels, the city as a whole being little-touched by the Eighty Years War. Brussels remained secure as a governing capital for the Spanish Habsburg administration and as a permanent hub for the Spanish standing Army of Flanders, which together provided a ready clientele among its officers of the nobility.

DESCRIPTION

The present armour comprises a close helmet with two-piece skull embossed with V-shaped flutes radiating downward from a ring finial on a stellate washer, the nape fitted with plume-holder, with pivoted peak drawn-out to a blunt point, visor embossed with a pronounced transverse rib pierced with a series of diagonal slots and a panel beneath them at each side pierced with numerous small ventilation holes, closed at the right by a hook-andeye, bevor closed by a strap, and fitted with neckguard of three lames front and rear; gorget of one plate front and rear; heavy shot-proof breastplate of late ‘peascod’ type and flanged outward at the base to receive a pair of tassets each of seventeen lames and divisible at the eleventh for service on foot, and with poleyns of six lames defending the joints of the knees, the third in each case embossed with a central rosette and formed with a pointed spadeshaped wing;

matching backplate extended at the sides within its working life, this corresponding with similar early alterations to the breastplate, fitted with armoured shoulder-straps for attaching the breastplate, and with a hinged bracket to attach a rear skirt of five lames; a pair of symmetrical pauldrons of eleven

lames connected by turners to articulated vambraces formed of tubular upper-and lower-cannons linked by a winged bracelet couter of five lames embossed with a central rosette;

a pair of fingered gauntlets each with strongly flared pointed cuff, metacarpus of five lames, knuckleplate, hinged thumb-piece and finger scales;

the main edges of the armour scalloped and bordered by pairs of incised lines, studded throughout with numerous brass rivets and retaining some original blued finish, the balance of the outer surfaces naturally oxidised to form a desirable finish.

Regarding the modern provenance of the present armour, Sir Guy Francis Laking, 2nd Bt., was in his time the leading published authority on the subject. In 1902 King Edward VII created for Laking the post of ‘Keeper of the King’s Armoury at Windsor’. He was also Inspector of the Armoury at The Wallace Collection, and in 1911 became first Keeper of the London Museum. Laking’s ‘A Record of European Armour through seven centuries’, together with his catalogues of the armouries of the Knights of St. John and the Winsor Castle armoury remain valued reference today.

A Model of an Armour for a Man and Horse in the 16th Century Style c. 1850

Probably

by E. Granger

Probably France, Paris. Steel, bronze, polished marble

54.5 cm × 19 cm × 41.5 cm / 21.4 in × 7.4 in × 16.3 in

PROVENANCE

Private collection, France

The man’s armour comprising a close helmet with a bellows visor, mounted on a single-lamed gorget with raised collar; the cuirass comprising a breast and backplate, the breastplate of peascod form fitted with a lance rest and with a fauld plate to which are attached tassets of five simulated lames; the fourlamed pauldrons large and symmetrical, attached by turners to articulated vambraces complete with winged couters; the gauntlets with shaped cuffs, five metacarpal plates and a knuckle plate; the legs formed of cuisses integral with five-lamed, winged poleyns, greaves and broad-toed, ten-lamed sabatons; the main plates with roped edges and etched throughout with bands and cartouches of gilt floral decoration.

The armour for the horse comprising full fluted shaffron with broad hinged poll-plate , gutter-shaped ear-defences, side -plates, cupped eye-defences and an heraldic escutcheon with central spike at the brow; laminated crinet with mail throat-defence; peytral of three plates applied with three heraldic escutcheons; flanchards of one piece; and a deep crupper of five riveted plates; all decorated at all main edges with bold, roped, inward turns bordered by raised ribs and brass rivets, accompanied by a curbbit with reinforced reins, and a saddle with high bow, cantle-plates and stirrups all decorated with panels of floral pattern on a gilt ground. Mounted on an articulated mannequin astride a bronze horse, with a heavy polished marble base.

Edward Granger arrived in Paris by 1820 where he established a business at 70 Rue de Bondy, today Rue René Boulanger, registered as a maker of giltbronze jewellery and of occult items. As early as 1844 Granger exhibited the meticulously detailed miniature armours for which he became renowned at the Exposition des Produits de l’Industerie Française, after which the artist met with tremendous commercial success. Granger also created fullscale armours for the Paris Opéra and the Duchess d’Orléans. She requested a perfectly scaled etched three-quarter armour to fit a five year old boy – LouisPhilippe-Albert, Comte de Paris, later King Louis VII, pretender to the French throne and eldest son of the Duc d’Orléans. We had the privilege of handling this armour, which featured in our 2009 catalogue, no. 41. Granger’s armour for the young Louis was published as an engraving by the Musée Challamel in 1844; Granger was credited as ‘the distinguished Parisian Armourer’.

BLADED WEAPONS

12

An Exceptional Italian Renaissance Hand-and-a-Half Sword

c. 1490 – 1500

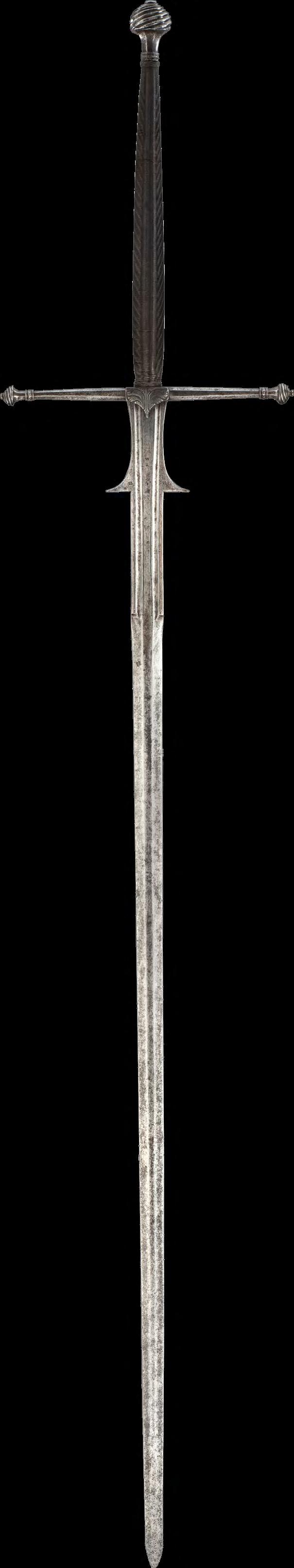

13 A Two Hand Sword of Knightly Quality or Montante c. 1500 – 1530

14 A Swept-Hilt Rapier with Silver-Encrusted Hilt c. 1610

15 A Riding Sword with Silver-Encrusted Hilt of Distinguished Quality

c. 1625 – 35

An Exceptional Italian Renaissance

Hand-and-a-Half Sword

c. 1490 – 1500

Italy. Steel, copper-alloy, silver, gold, ebony and bone

The grip a later restoration 114.3 cm / 45 in (overall length)

PROVENANCE

G. P. Jenkinson Collection

Private collection, Germany

Private collection, USA

‘As in all other fields of applied art,’ observed the late Dr John Hayward when writing some years ago, ‘the high point of hilt design, either as ceremonial or fighting weapon, was reached during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century.’ ‘The excellence of the weapons of this period’, he went on to note, ‘is reflected in their superb proportions and exquisite decoration.’ He felt this sword ‘worthy of the greatness’ of any of the Renaissance princes. Few could deny that this sword, with is elegant lines and rich ornament arranged in counter-changed panels of contrasting gold, silver and gilt copper-alloy, satisfies this criteria of proportion and decoration.

The gilt hilt of the sword comprises a flattened pearshaped pommel, and long horizontally re-curved flat quillons. Each part is cast and finely chased with running vine leaves, scrolling acanthus foliage, fleursde-lis and plaited ornament, and is inlaid at points with similarly decorated gold and silver panels and, in silver, a female bust whose breasts are bitten by serpents. Beneath is a gaping Medusa’s head from which further serpents rise. The later grip is decorated with a chequer pattern of freshwater mother-of-pearl and ebony panels. The double-edged blade, each side with a pronounced medial ridge, tapers to a point; inlaid in copper is a Lombardic M beneath a cross and the blade is etched at the forte with a pattern of imbricated scales.

LITERATURE

Dr J.F. Hayward, An Italian Renaissance Sword, in Arms and Armour at the Dorchester Ltd, London, 1982, p. 15-17

Dott. Mario Scalini, Reconsidering some Cerimonial Italian Swords of the Renaissance, Hieb- Und Stichfest: Waffenkunde und Living History, Imhof Verlag, Coburg, 2020, p. 75, illustrated p. 74

The quillons of the sword, like its pommel, are divided into panels of various metals: seven on one face and five on the other. The plaques are either chiselled in relief or engraved intaglio with conventional floral ornament. Each side of the cross is chiselled with the same plaited design as the edge of the pommel, while the tongue or langet, which was intended to cover the mouth of the scabbard, is chiselled with acanthus foliage issuing from a scallop shell and fleur-de-lis at its base. The purpose of this socket was practical: to prevent water from seeping into the scabbard and so rusting the blade, should the sword be exposed to rain or humidity.

Although its superlative quality suggests that the sword was intended primarily for ceremonial use, its design nevertheless accords in all essential respects with that of a practical fighting weapon. Its long handand-a-half grip enable it to be wielded with either one or two hands as needed in combat, and its long, acutely pointed blade, would have been suited to both cutting and thrusting. The pronounced medial ridge that runs down each side of the blade serves to stiffen it, and would have made the sword better able to penetrate any gaps in the full plate armour favoured in Renaissance Italy.

Contemporary representations such the illuminations of Tallhofer’s Fechtbuch of 1459 (Schloss Ambras), and the painting The Coronation of the Virgin (1474, Museo Civico, Pesaro), by Giovanni Bellini, show that blades of this medially ridged pattern were fit to the hand-and-a-half sword type, and interestingly both images represent swords with hilts similar to the present example.

Surviving early Renaissance swords of a quality comparable to the present are few in number and invariably associated with persons of great wealth and rank of the period. Among the most celebrated of these is a sword in the Rüstkammer, Staatliche Kunstsammlung Dresden (no. hm.a36), identified in early inventories of the Saxon Electoral Armoury as that of Graf Leonhard von Görz (1440–1500). Though its pommel is of plummet-shaped rather than pear-shaped form, the two swords show a strong resemblance. The Rüstkammer blade is inscribed JESUS MARIA and IN ETERNVM, which has led to the idea that it was given to von Görz at the time of his marriage to the Mantuan princess, Paola Gonzaga, daughter of Luigi III Gonzaga in 1478.

A splendid sword today in the Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna (no. a.170) made for Maximilian I, King of Rome and later Holy Roman Emperor (1459–1519) provides another comparison. Though it has a key-shaped pommel and straight rather

than re-curved quillons, it also bears a striking resemblance to the present sword. Its hilt, also of gilt copper-alloy, bears the inscription IN DIO AMOR which together with the representations of Amor and putti in the decoration of its blade has led to the suggestion that the sword was given to Maximilian at the time of his marriage to Bianca Maria, daughter of Duke Galeazzo Maria Sforza of Milan in 1493/4. This would also suggest the sword was created in Milan, then the greatest of all European arms-producing centres. Affording support for that view is the fact that a sword in the Museo Civico L. Marzoli, Brescia, again bearing similarities, was stated to be struck on its tang with the Sforza mark of a viper. Equally worth examination is the decoration of the so called ‘Martelli Mirror’ in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (no. 8717–1867), which like the present sword involves gilt copper-alloy inlaid with silver and gold, and is thought to have been produced by the Milanese artist Caradosso Foppa (1452–1527) around 1495–1500.