Now that September is here and return-to-office policies are in place, attention is shifting from physical presence to the quality of the workplace experience. More than half of Fortune 100 companies now require full-time office attendance but just showing up doesn’t necessarily mean people are engaged.

To get the most out of working in-person, design has to do more than look good and meet operational needs It must also support the psychological, social, and behavioral dynamics that shape how people interact, collaborate, and contribute.

At Perkins Eastman, we believe that the built environment should respond to human needs in all their complexity. To deepen our understanding of how behavioral science can inform workplace strategy, we spoke with Dr. Ian Roberts, a behavioral scientist whose research explores the interplay between individual psychology, environmental cues, and organizational systems

Designing for Behavior

Too often, workplace strategy focuses on operational details how many desks are needed, who comes in when, or how to optimize square footage. While those are important considerations, they overlook the most critical factor in workplace success, which is how people behave once they’re there.

“Mandates and incentives don’t get you very far without a deeper understanding of what drives human behavior,” Roberts says. “When people feel they’re losing control over their choices, they tend to push back It’s a natural human response ”

Reactance is a psychological reflex that triggers resistance conscious or unconscious when people perceive a threat to their autonomy. In the workplace, it can show up as disengagement, withdrawal, or just doing the bare minimum

Sustained engagement, Roberts says, is not the result of enforcement or consequences, but of alignment between an individual’s sense of purpose and the environment in which they operate

A Framework for Behaviorally-Informed Design

Behavior is a product of both the person and their environment. Neither leads to behavior without being shaped by the other Roberts offers a way to understand workplace behavior in the context of a broader system:

This framework emphasizes the constant interplay between internal drivers and external cues

Person: Identities, motivations, values, and routines

Example: One employee may prefer early-morning focus, while another works best in team sessions later in the day Designing for variety and choice supports a range of work styles and promotes autonomy

Environment: The spatial, social, and organizational context that shapes behavior

Example: A centrally located wellness area communicates that wellbeing is a priority Quiet zones convey support for focus; open zones invite connection. These signals operate consciously and subconsciously.

Behavior: The actions and interactions that emerge from the alignment or misalignment between person and environment

Example: Transparent office fronts may signal openness and accessibility, while enclosed rooms suggest privacy and control

“Spaces send signals,” Roberts says “They shape what people believe is acceptable, encouraged, and expected.” Environmental cues can set social norms and influence attitudes and behavior, often without conscious awareness

Strategic Questions for Workplace Planning

Behaviorally informed design invites more nuanced questions, such as: What purpose does the office serve in this organization’s current and future state?

What types of interactions or outcomes is the space intended to support? How do workplace policies and leadership behaviors reinforce or contradict the values the space is designed to represent?

The goal is to ensure consistency across all levels of the employee experience, from spatial design and cultural norms to policies and performance expectations. Misalignment in these areas can undermine trust and reduce the effectiveness of workplace investments.

Translating Insight into Action

Bringing behavioral science into workplace design requires thoughtful application. The following principles can help guide the process:

1. Engage employees as co-creators

Use surveys, interviews, and workshops to bring employees into the design process. Visioning sessions or “build-your-ownneighborhood” exercises allow participants to define priorities and co-create solutions generating insight and building trust.

In practice: This approach guided Perkins Eastman’s recent workplace transformation for the East Coast offices of a global pharmaceutical company. Rather than relying on top-down communications, the team co-developed an etiquette guide with internal stakeholders to clearly articulate the “why” behind the new work model. Involving employees in the process fosters

2. Design for intrinsic motivation

Support the core drivers of engagement autonomy, mastery, purpose, and connection. Tactics might include shared commons for informal dialogue, flexible zones for individual control, or displays that reflect collective goals and values.

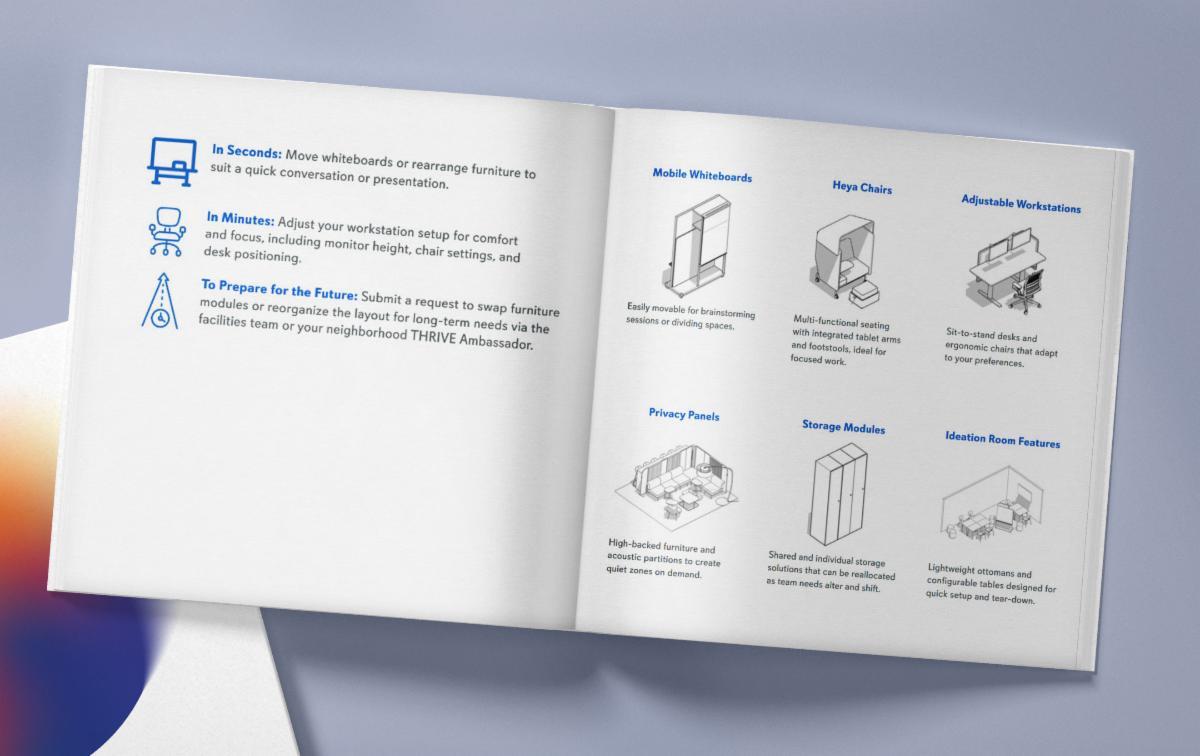

In practice: For the same client, an innovative furniture system empowers employees to reconfigure their environment in seconds or minutes. Whether adjusting monitors and chairs for ergonomic comfort, arranging whiteboards for a quick team huddle, or customizing their setup with color-coded cushions and accessories, employees gained control over certain aspects of their space. Small acts of autonomy help reinforce a sense of agency and belonging.

3. Align policy, environment, and leadership

Ensure consistency across space, norms, and behavior If flexibility is a stated value, policies and leadership practices should reflect that Inconsistencies reduce trust and weaken cultural signals.

In practice: “Me,” “we,” and “us” zones at the new offices clearly reinforce whether the space is intended for individual focus, team collaboration, or organizational community. Complementary design features like shared planters, personal lockers, and team storage support a sense of shared responsibility. Community walls encourage teams to share achievements and updates, making cultural values tangible in the everyday environment.

4.

Measure meaningful outcomes

Move beyond attendance to assess collaboration quality, sense of belonging, and ability to do meaningful work. These qualitative indicators can be harder to measure, but they offer deeper insight into workplace effectiveness.

In practice: User journeys, or storyboards of a typical “day in the life,” helped teams visualize how the space could support diverse needs Community practices were also clearly outlined, with encouraged and discouraged behaviors made explicit. Feedback loops gave employees ways to offer input, reinforcing that the change wasn’t happening to them but with them.

Designing with Intention

“Behavior is shaped by the relationship between people and their environment,” Roberts says. “If you want to influence outcomes, you need to design that relationship intentionally.”

Workplace design is no longer a matter of space planning alone It is a strategic tool to shape culture, support engagement, and enable high performance. As work continues to evolve, organizations that design with intention will be better positioned to attract, retain, and empower their people.

Further Reading

Thinking, Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman

Nudge – Richard H Thaler & Cass R Sunstein

The Power of Habit – Charles Duhigg

Selected research by Dr. Ian Roberts

How did you like this email?