ARTICLES FROM

STUDENTS

FIRST CLASS TRIPOS ESSAYS

FIRST CLASS TRIPOS ESSAYS

DearReaders,

Welcome back to the Per Incuriam, Lent 2025 edition! Once again, I would like to offer my sincerest congratulations to the Per Incuriam Editorial team for successfully rolling out this Spring’s edition. Thank you to Editor-in-Chief Ewan O’Mahony, and Deputy Editors Chloe Levieux and Alpha Ngai for your hard work throughoutterm,inmeticulouslysifting through numerous essays and putting together a cohesive narrative for this issue.

We hope that you will benefit from the Lent edition of Per Incuriam as much as you did from the Michaelmas edition. Per Incuriam is an important avenue through which CULS provides our members with high-quality academic essays, and student-written articles on salient topics. We hope that this edition of Per Incuriam remains inspiring and thought-provoking – academically and beyond! In the same vein, I would like to thankthegenerouscontributorsforthis edition, without which this edition wouldnotbepossible.

Lent has been an unforgettable term, marking the end of the current Executive Committee’s tenure. We have had the pleasure of welcoming Lady Rose and Lady Simler, two esteemed Supreme Court Judges, to speak with our Members this term as part of our Speakers’ line up. With our diverse range of socials and weekly welfare drop ins, we hope that we have provided an environment where our members feel taken care of. Throughout this 2-month period, we have also hosted significant career events that welcomed legal professionals from all fields of law, including in-house counsels and family andhumanrightsbarristers.

We hope that the 2024-25 CULS year was as fruitful for you as it was for us. We wish everyone all the best for Tripos examinations, and a restful (but productive) Easter break ahead, where our Per Incuriam, Lent edition, comes intogooduse!

SeeyouinEaster!

Joyce Mau

CULSPresident2024-2025

Chloe Levieux, Ewan O’ Mahony, Alpha Ngai

PerIncuriamSubcommittee2024-2025

DearReaders,

CongratulationsonmakingitthroughLent Term!Aswintergiveswaytospring,weare reminded that only one term remains in the academic year, and for third-year students like me, it is a sign that our time in Cambridge will be coming to an end soon. With exams fast approaching, I hope that the selection of essays in this edition, which have scored top grades in actual Tripos exams, will serve as a valuable study resource.

This Lent Edition of Per Incuriam also features a diverse and thought-provoking collection of articles. Two contributions adopt a comparative law perspective –Harry Huang explores the concept of analogy in Islamic Law, contrasting it to Western legal doctrine, while Grace Cronin compares the conceptions of the Rule of LawinSingaporeandtheUnitedKingdom.

Additionally, a case note by Jun Xiang Wong analyses the recent decision of RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV [2024]UKSC18.We hopeyoufindthesearticlesasengagingas wedidduringtheeditorialprocess.

I would like to extend my gratitude to Alpha Ngai and Chloe Levieux, Per Incuriam’s deputy editors, as well as Nathanael Tung and Owen Warrington, our Freshers’ Representatives, for their dedicationinbringingthisissuetofruition.

I would like to also extend thanks to our article contributors, Harry Huang, Grace Cronin and Jun Xiang Wong, and our essay contributors, Rowan Lightfoot, Harry Marsh, Liew Li Ren, Zheng Yu Chow, Ffion Griffith, Camryn Taliku, Oluwatoni Adewole and Sulanya Pallewatte. Finally, my thanks go to the Executive Committee, especially the Publicity Team who completed the creative design of this edition, for supportingthroughout.

If you would like to contribute to Per Incuriam, please email us at perinc@culs.org.uk. In addition to having your work published, we also reward our essay contributors with a monetary award.Weacceptpiecesonawiderange of legal topics, so please feel free to pitch your ideas to us and keep an eye out for contributor applications opening for the Summeredition.

02. 03. 05. 11. 18.

President's Foreword

Joyce Mau

Editors’ Welcome

Ewan O’Mahony

A comparative study of the rule of law

Grace Cronin

Analogy in Islamic Law

Harry Huang

CASE NOTE: RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV

[2024] UKSC 18

Jun Xiang Wong

26. 27. 30. 36. 43.

Essay Selection Guidelines

Constitutional Law

Rowan Lightfoot

Tort Law

Harry Marsh 53.

Land Law

Liew Li Ren

Family Law

Oluwatoni Adewole

Zheng Yu Chow 48. 59. 63. IP Law

Criminal Procedure & Evidence

Camryn Taliku

Aspects of Obligations

Ffion Griffith

Comparative Law

Sulanya Pallewatte

A

Grace Cronin

Introduction

In ‘The Rule of Law’, Tom Bingham writes of a formal conception of the rule of law, which includes the protection of fundamental rights such astherighttocounselandfreedomof expression. This perspective is convincingandrightlyemphasizesthe law’s relationship with morality. Through this lens, the rule of law is weakerinSingaporeassuchrightsare lessprotected.

In ‘Rule of law within a non-liberal ‘communitarian’ democracy’, Thio referenced that Singapore’s history of being a British colony means its legal system is based on the Westminster model. However, Singapore’s modern conceptionoftheruleoflawhasmore weaknesses than the United Kingdom’s.

This article submits that the United KingdomandSingaporehavedifferent conceptions of the rule of law due to having different overarching aims in their respective legal systems. Singapore is focused on minimizing crime levels and maximizing government efficiency (Reynolds, ‘Intertwining Public Morality’) whereas the United Kingdom’s main priority is havingopen,clearlawsandhavingfair laws in order to be democratically accountabletothepublic.

In ‘Developing a people-centered justiceinSingapore’,CheahWuiLing commented that the weakness of the right to counsel was evidenced by the 1998 case of Rajeevan Edakalavan v. PP, the Singapore HighCourt(1435).

In this case, it was held that the Constitutional right to counsel is “a negative right” because the Constitution’s text states that an accused “shall be allowed” access to counsel but does not require the accused to be informed of his right tocounsel.Thecourtrefusedtofind a positive obligation to inform the accused of this right, noting that to do so would “be tantamount to judicial legislation” . This weakens the individual’s right to counsel as, since they need not be informed, they are less aware and thus less empoweredtoexercisethisright.

This directly contrasts the United Kingdom’s approach. The Human Rights Act of 1988 incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights into UK domestic law. Under Article 6 of the latter, the right to counsel is described not as something that ‘shall be allowed’ but with stronger language –‘[e]veryone charged with a criminal offence has the …minimum right[]… to defend himself in person or through legal assistance’. This strength of the right to counsel can be seen in case law. For example, in Cadder v HM Advocate [2010], the United Kingdom Supreme Court ruled that not having immediate access to a lawyer, prior to a police interview, could infringe your right tocounselunderArticle6(ScotsLaw News).

Furthermore, the issue of quality and availability of legal advice furthersuggestsSingapore’srelative

‘weakness in comparison to the United Kingdom in regard to the right to counsel. In the Legal Aid Review Report by Singapore’s Law Society, it was recommended that Singapore firms each dedicate 25 hours per year to pro bono work. However, only some firms have taken up such a pledge, let alone succeeded. By contrast, in the UK, the Global Legal Post reported that under the UK Collaborative Plan for ProBonowork,78firmscontributed a record of 609,000 hours of pro bonoworkin2023.Thisworksoutto each firm contributing over 7000 hours to pro bono work on average. This suggests there is greater availability of free legal aid in the United Kingdom compared to Singapore as individual firms contributemoretoprobonowork.

This disparity suggests the right to counsel is in a stronger position in the UK as poorer individuals have more access to free legal aid compared to Singapore. This is supported by the fact that in 2010, the Singapore Chief Justice noted that a third of accused persons in criminalcasesrepresentthemselves. Furthermore, pro bono work by the largest pro bono organisation, the CriminalLegalAidScheme,doesnot cover legal work for clients facing thedeathpenalty.

In a 2017 report by Human Rights Watch, it was persuasively argued that Singapore’s various existing provisions overly restrict freedom of speech. For example, the organization cited that the Media Development Authority is empowered to instruct internet service providers to remove any material not deemed within the ‘public interest’. This criterion not being sufficiently defined is worrisome and ascribes too much control to the government to police expression. Statutory powers are not the only tools for restricting freedom of expression. Human Rights Watch wentontocommentthat

‘individuals who are critical of the governmentorthejudiciary,orspeak critically about religion and issues of race, frequently face criminal investigationsorcivilsuits,oftenwith crippling damages claims’. This can be evidenced by the 2014 case, where Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong sued blogger Roy Ngerng for $150,000 under defamation for his criticism of the government online (TheStraitsTimes).Thiswasfollowed by a new bill, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act,beingpassedafewyearslaterin 2019, which allows for ‘false information’ that is oppositional to ‘public interest’ to be removed. This highlights how freedom of expression is stifled in Singapore as the media and online resources are overly policed with statutes and civil actions which deter possible ‘offenders’.

This greatly contrasts the approach to free expression in the United Kingdom.UnderArticle10,whichUK courts are obligated to enforce, ‘[e]veryone has the right to freedom of expression’ which includes ‘freedom to hold opinion….and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority’. This has been upheld throughoutUKcaselaw.

Simms is an excellent example. In Simms,itwasruledthattheHome Secretary was acting ultra vires by banning journalists from visiting a prisoner claiming to be innocent. Additionally, the Supreme Court also included obiter comments on the importance of this case in regardtofreedomexpression.Lord Steyn wrote that freedom of expression is ‘instrumentally important’, highlighting that ‘[i]t facilitates the exposure of errors in the governance and administration of justice of the country’ and thus, reduces ‘abuse of power by public officials’ and improves public confidence (‘people are more ready to accept decisions that go against them if they can in principle seek to influence them’). This highlights that there is a greater commitment to freedom of expression in the United Kingdom as courts are explicitly seeking to empower individuals to criticise the government for an alleged wrongful conviction. This improves public trust and prevents abuse of government power. Furthermore, laws in the UK do not include statutory rights to take down individuals’ expressions but rather enshrinefreedomofexpressionvia Article10.

In Singapore, the same political party, the People’s Action Party, has been in power since 1965. This stagnant political environment and the likelihood of this party continuing to comfortably win elections means that there is less democratic accountability to the public. There is therefore less of an incentive for the government to investinsafeguardingtheruleoflaw through strengthening certain fundamental rights. If anything, there is incentive to tighten restrictions on freedom of expression, specifically in regard to critiquing the government (as evidenced prior in the article), to maintainthisstatusquo.

This contrasts with the United Kingdom, which has a more varied history regarding election results and political parties in power. The political rivalry between the Labour and Conservative party encourages thegovernmenttobemoreattuned to safeguarding fundamental rights under the rule of law, since Parliament is democratically accountablefortheirchoices.

...Singapore’smodernconceptionof theruleoflawhasmoreweaknesses thantheUnitedKingdom’s.

Moreover, the difference between the conceptions of the rule of law between Singapore and the United Kingdom can be attributed to their differing governmental aims. A major aim in Singaporeistomaintainalowcrimerate. A diminished and weakened right to counsel in Singapore fits into a broader context of harsh sentencing guidelines, strict laws, and disproportionate punishment relative to crime. The Death Penalty Project, for example, reports that Singapore’s criminal justice system does not abide by international standards due to the inclusion of caning and death penalty punishments. Maintaining this strict legal regime is part of Singapore’s desire to maintain its famously low crime rate. In a 2022 report, it was found that Singapore’s crime rate is far lower than that of any major city in the UK across a broad range of crimes, sometimes 4 times lower than the most dangerous cities of the UK (Ashby et al.).

Contrastingly, the United Kingdom’s government, of course, strives for low crime rates, as any government would, but not the extent of being willing to compromise on the fundamental rights and having an immensely strict criminal justicesystem.TheUK’sfullconceptionof the rule of law demands upholding the fundamentalrightsofprisoners,including the right to counsel and freedom of expression via journalists reporting on theircases.

Fundamentalrightssuchasfreedomofexpressionand right to counsel are not as strongly protected in Singapore as they are in the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom’s adoption of the European ConventiononHumanRightsiscriticaltothispoint;the contents, namely article 6 (right to counsel) and Article 10 (freedom of expression), include strong language suggesting positive rights, which means courts are obligated to unambiguously enforce these rights in domestic cases. Contrastingly, the right to counsel is describedlessforcefullyintheSingaporeanConstitution (‘shall be allowed’) and even more concerningly, freedom of speech is prohibited and unduly restricted undermultiplestatutes,withgovernmentbodiesbeing able to use vague justification (‘public interest’) for removingsuchspeechonline.

Similar comparisons can be found outside statutory provisions. There is a troubling history of Singaporean politicians using civil action against dissidents, whereas judgments uphold the principle that free expression is important for democratic purposes. Furthermore, Singapore having less of a culture of pro bono work compared to the United Kingdom impedes poorer individuals’righttocounsel.

These differences can be attributed to politicians being lessdemocraticallyaccountableinSingaporeincontrast to the United Kingdom, so interest in using statutory provisions to strengthen fundamental rights is not as incentivized.Morespecificallyregardingtheissueofthe right to counsel, Singapore’s harsh criminal justice system and commitment to low crime make them less inclined to strengthen the right to counsel. Contrastingly, the United Kingdom’s broader commitment to human rights in their statutory schemes obligates them to ensure prisoners have accesstofundamentalrights.

Harry Huang

Introduction

Max Weber liked to talk about kadijustiz (“Islamic judge justice”), which he defined as “a kind of adjudication that is primarily bound to hallowed traditions,” consisting of arbitrary judgments decided by caprice,independentofasystematic law (Weber 1978, p. 976). Since then, Westernlegalscholars,evenuptoUS Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, have used kadijustiz as an insult, conjuring up images of inexpert Islamic judges (qadi) sitting “under a tree dispensing justice according to considerations of individual expediency,” in blissful ignorance of statutes and rational law(Rosen1980).

But Weber was wrong. Legal scholarship has flourished throughout Islamic history, coalescing into a diverse set of established legal schools of thought, each with its own system of jurisprudence and precedent to guide Islamic judges. This article is a loose exercise in comparative law, offering an exposition of analogy in Islamic jurisprudence and discussing itscontrastswithanalogyinWestern legaltraditions.Inparticular,Ichoose to focus on the jurisprudence of the progenitor of the Shafi’ite school of Islamiclaw,al-Shafi’i.

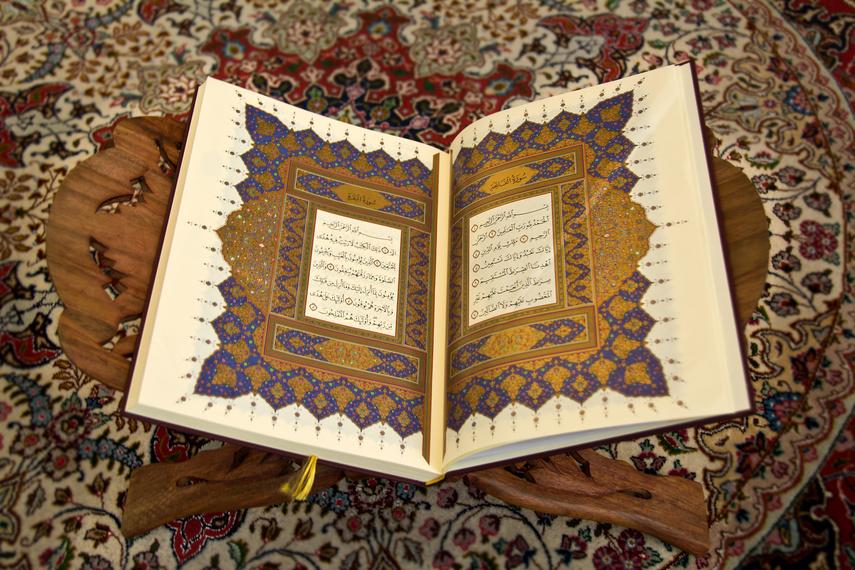

Islamic law begins with the Qur’an, the sacred text of Islam, revealed throughout the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad. Contemporary Muslims generally also believe that the sunnah oftheProphet,embodied in the corpus of hadith, is another source for religious law. Collectively, the Qur’an and sunnah essentially comprise Islam’s body of statutory law.

SincethedeathoftheProphetin632, Islamic law has been a legal system withoutalegislator,onlyjurists.When al-Shafi’i was born in the late eighth century, early Islamic jurists were contending with this issue, developingcompetingjurisprudential remedies to enable Islamic law to survive without new definitive judgmentsfromtheProphet.Indeed, the flourishing of legal thought during this period produced all four progenitors of the four extant Sunni schools of legal thought (Hanbali, Shafi’i,Hanafi,Maliki).

Part of the contemporary legal debate was the conflict between “allegiance” (ittiba’) to received tradition and “originality” (ibtida’) of judicial reasoning to rationalize the law (Hasan 1976, p. 203, Lowry p. xix). For supporters of ibtida’, new Islamic law could come from juristic interpretation and ijtihad Ijtihad could comprise a broad category of legal techniques, such as decisions based on public interest or expediency (istislah), subjective juristic preference (istihsan), or analogical reasoning from authoritative sources (qiyas), among other techniques. In contrast, supporters of ittiba’ vigorously disparaged these techniques and campaigned for a strict textualism, upholding a higher view of the authorityofthe sunnah

To some degree, Shafi’i walked a middle path between these poles (Lowry p. xix). The jurisprudence of Shafi’i circumscribes the limits of juristic reasoning, firmly upholding the text of the Qur’an and the sunnah, whilst synthesizing it in a subtle harmony with the reason of thejurist.Thisistheaccomplishment ofoneofthefirstsystematisersofthe principlesofIslamicjurisprudence.

Shafi’ibeginsfromthepremisesthat the collective corpus of the Qur’an and received hadith contains no contradictions and provides law for every single situation without lacunas. Therefore, to the extent that this corpus of law does not directly comment on a situation, there must existsomeindirectindication(dalil)

in the text, which can then be unravelled into an applicable ruling through ijtihad (Lowry pp. xxii-xxiii).

And yet, Shafi’i accepts that just as judgesmaylegitimatelydisagreeona matterlikethecredibilityofawitness, jurists may find themselves legitimately disagreeing on the result of analogy (Lowry pp. 353-355, p. 345).

To address this issue of subjectivity in analogy, he considers the case of two worshippers who find different qibla and cannot reconcile their disagreement. While it is impossible thatbothindividualshavethecorrect qibla, in both applying earnest effort, each has produced an answer with theappearanceoftruth.Hence,Shafi’i declares that each person is justified in praying according to their own qibla, reasoning that either the duty of the qibla only requires making a best effort to discover the right qibla, orthatifthedutyofthe qibla requires finding the true qibla, making a best effort waives the penalty of failure (Lowryp.351).

Once you have your overall theme, you can start brainstorming the content. Just starting? Design a memorable masthead with an equallymemorablename.

This goes on the cover and sets up the branding for your entire magazine. What style are you going for? Is it playful? Classic? Bold? A goodmastheadcapturestheessence of your magazine, so it needs to be flexible, meaningful, and consistent enoughforfutureissues.

This uncertainty of qibla equates to and justifies the uncertainty of analogy, pointing to a deeper spirit within Islamic law. The philosophy of Islamic law is underpinned by the contrast between the sharia and fiqh. The sharia is the idealized, unseen law as laid down by Allah, and only known completely to Allah. Theattemptsoffalliblehumanjurists to access the sharia create fiqh, which is the body of laws that constitutethehumanunderstanding of the sharia. In acknowledging and validatingthesubjectivityofanalogy, Shafi’i expresses the great spirit of intellectual humility of Islamic law that comes from the gap between fallible human fiqh and the true sharia,ultimatelyknownonlytoGod. Thus, just as the devotee necessarily lacks ultimate certainty about whether they have found the right prayer direction, the jurist must be content with the results of their qiyas, and accept uncertainty about whether they have found the true sharia

Intheend,thelegalthoughtofShafi’i comes to resemble a very odd form of civil law. His ideal Islamic judge must be utterly dependent on the corpus of divine law revealed in the Qur’an and sunnah, exceeding even thedependenceofthecivillawjudge on statutory law. Yet, the Islamic judge does not have the luxury of a continually existing legislative authoritytofeedinnewstatutes,and thusfrequentlyfacesnovelsituations. Farmoresothancivillawjudges,the Islamic judge must exercise considerable discretion to produce law for novel situations, although doing so in a grave, carefully prescribedmannerthatseekstohew as close to original statutes as possible.

Within the historical context of Shafi’i, his defence of qiyas is not oriented against the alternative of a stricter textual adherence that excludes qiyas, but against the alternative of freer methods of judicial interpretation less bound to statute. Indeed, his fundamental attitude is that qiyas only uncovers rulesalreadycontainedintheunseen divine law and indirectly indicated in thecorpusofrevealedlaw.

This orientation contrasts sharply against Western attitudes toward legal analogy. Shafi’i understands analogy to be a relatively conservative judicial tool, while Western law understands analogy as arelativelyliberaljudicialtool.

Given that Western legal systems have relatively plentiful statutory law and have continuing sources of new statutory law, the alternative to analogy is usually understood as the option of stricter adherence to statute and analogy is seen as a departure from the fundamental text. For example, the maxim nulla poenasinelege isgenerallyaccepted tomeanthatforcriminallaw,ajudge cannot employ analogical reasoning to expand a statute to the detriment oftheaccused(Koszowskip.138).

This difference in attitude leads to sharply different practical outcomes. If analogy is understood as liberal and thus sometimes unacceptable, the temptation is to generate separate categories of methods of judicial interpretation to justify them by contrast with analogy. For example, while French law forbids extending criminal statutes by analogy,Frenchcourtsstillstretch

statutes to cover novel situations. Instead of using the forbidden tool of analogy, they instead invoke the principles of the spirit of the law or legislative intent (Troper et. al 1991, pp. 200-201). Unsurprisingly, the boundary betweenthesemethodsandanalogy iselusive.Indeed,somescholarshave suggestedthatwhileFrenchcriminal courts prohibit analogia iuris, analogy from a general spirit of the legalsystem, analogia legis,inferring a grander rule from a particular statute to apply to a novel situation, has hidden acceptance in practice. Italian law similarly prohibits analogy from criminal statutes, so Italian criminal courts sometimes instead declarethattheirjudicialreasoningis actually just extensive interpretation (La Torre 1991, p. 219). Because of this conception of analogy, the temptation arises for judges to split hairs to justify ambiguously permissibleactsofjudicialdiscretion.

In contrast, Shafi’i is very clear about the difference between analogy and other varieties of textual interpretation. A judicial decision is either licitly based ondirectreadingofthestatute,licitlybasedon qiyas,orillicitlybasedonsome othermethodthatfailstodirectlydependonthetext.Since qiyas isconstrued broadly to mean anything outside the most literal meaning of the text—even basic a fortiori inferences are classed as qiyas—the boundary between straightforward literal readings and qiyas is clear (Lowry p. 369). Hence, Shafi’i doesnotneedtoconfrontthesubjectivityofanalogybyarbitrarilydividingout acceptablecategoriesofjudicialinterpretationfromanalogy.Instead,he

adoptsaprofoundintellectualhumilityabouttheefficacyof qiyas,andfocuses his efforts on refining the procedural aspect of analogy. He compares analogy to criminal justice, in that both involve careful application of procedure that tends towards, but does not guarantee, a correct answer. Just as a judge may use a methodical process to judge the credibility of a witness, the jurist can apply a defined procedure of analogy to answer a point of law. But just as finding for the credibility of a witness can never completely guarantee their honesty, even the best-crafted process of analogy does not fully guarantee a correct result (Lowry pp. 353-357). Later scholars eagerly took on this work of developing jurisprudential formulas to define and refine proper procedure in qiyas

Unfortunately, the Western world has gotten away with a terrible disregard for the intellectual products of the Islamicate world and its pantheon of great thinkers. Far from the Western stereotype of inchoate kadijustiz, Islamic judges look back to a legal tradition with a longsequenceoftitanicscholars,no less talented than legal thinkers in Western traditions. Shafi’i is one of the greatest scholars of that tradition, and his fresh perspective on analogy he offers has great relevance for contemporary practicesinWesternlaw.

Bibliography

1. Koszowski, M. (2016). Restrictions on the Use of Analogy in Law. Liverpool Law Review, 37(3),pp.137–151.doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10991-016-9186-y.

2. Massimo, L.T., Enrico, P. and Michele, T. (1991). Statutory Interpretation in Italy. In: D.N. MacCormick and R. Summers, eds., Interpreting Statutes: A Comparative Study.Routledge,pp.213–256.

3. Muḥammad Ibn Idrīs Shāfiʻī and Lowry, J.E. (2013). The epistle on legal theory NewYork:NewYorkUniversity.

4. Rosen, L. (1980). Equity and Discretion in a Modern Islamic Legal System. Law & Society Review,15(2),p.217.doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3053603.

5. Troper, M., Grzegorczyk, C. and Gardies, J.-L. (1991). Statutory Interpretation in France. In: D.N. MacCormick and R. Summers, eds., Interpreting Statutes: A Comparative Study.Routledge,pp.171–212.

6. Weber, M. (1978). Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology Google Books.UniversityofCaliforniaPress.

Sunnah: The practice and customs of Islamic prophets consideredobligatoryordesirabletoemulate

Hadith:Atransmittedaccountofasaying,eventordecisionfrom thelifeofMuhammad,potentiallyasourceforthesunnah

Ijtihad:Theprocessofajuristapplyingindependentreasoningto generateanoveljudgementfromtheQur’anorsunnah

Qiyas:AnalogyfromexplicitsourcesofIslamiclaw

Dalil: Broadly meaning a sign or indication, or specifically a legal sourceorprooftextSharia:Thebodyoftruedivinelaw

Fiqh:ThebodyofhumanIslamicjurisprudence

Qibla: The direction Muslims are obliged to face during ritual prayers,presentlytheKaabainMecca

Jun Xiang Wong

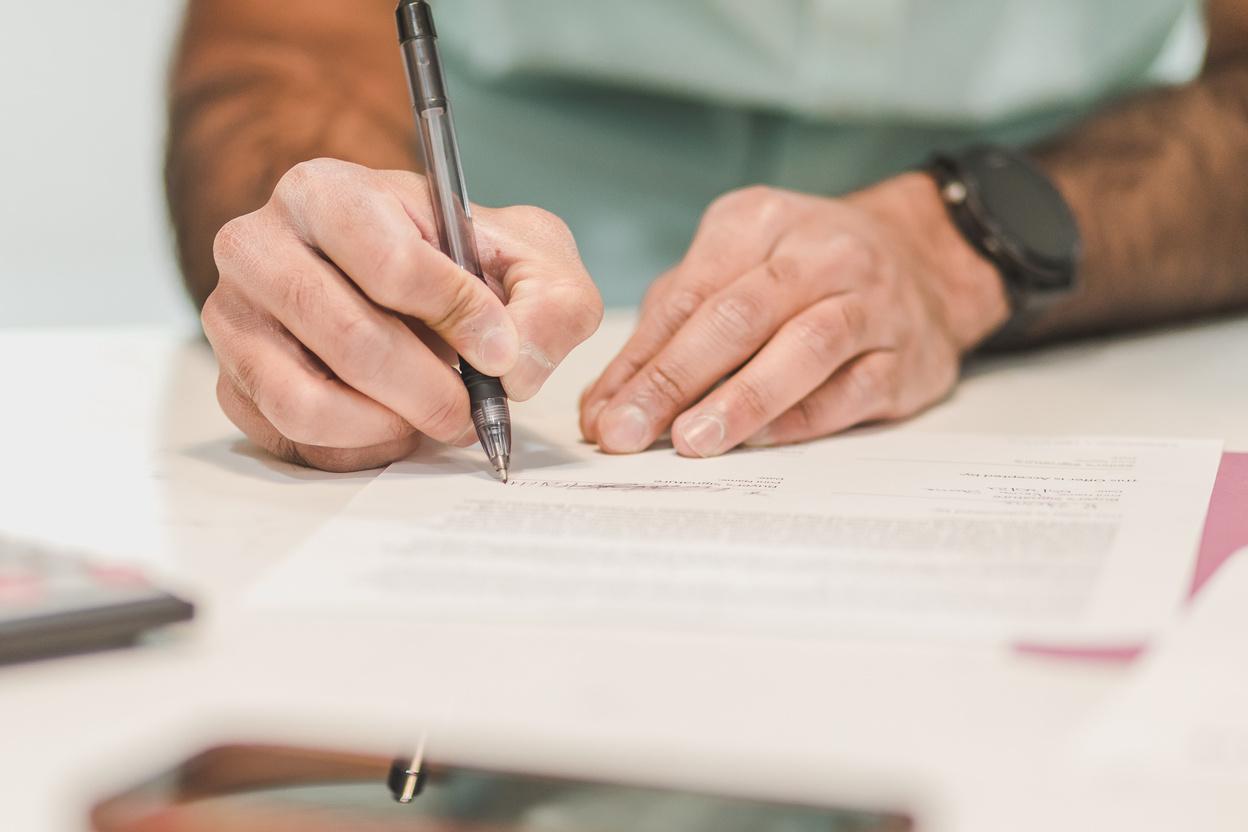

Therecentcaseof RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV. offers a valuable insightintocorevaluesinthelaw of contract through the lens of force majeure and “reasonable endeavours” clauses. However, although it attempts to uphold thesanctityoftheparties’legally binding agreement, the case raisespotentialissuesforthelaw of currency, the effects of force majeure events and the interpretation of contractual terms.

The Facts

On 9 June 2016, Dutch shipowner MUR Shipping BV (“MUR”) entered into a contract of affreightment with Jersey charterer RTI Limited (“RTI”) for the shipment of bauxite from Guinea to Ukraine. They agreed that paymentsweretobemadefromRTI toMURinUSDollars.

Subsequently, the American Office of Foreign Assets Control placed sanctions on RTI’s parent company, andbyextension,RTIitself,on6April 2018. The sanctions did not prohibit RTI outright from making payments in US Dollars. However, transactions in US Dollars would have to pass throughanintermediarybank,

which would delay them to investigate if they complied with the sanctions. It appeared highly unlikely that RTI would be able to uphold its end of the deal and make payments in US Dollars in a timely manner.

MUR and RTI had inserted a force majeure clause into their contract. Clause 36 purported to exclude both sides from contractual liability if a “Force Majeure Event” arose. MUR notified RTI that the US sanctions had constituted such a “Force MajeureEvent”.

However, RTI rejected MUR’s notification, and proposed an alternative course of action. RTI offered to pay in Euros instead of US Dollars. RTI also offered to bear any additional costs or exchange rate lossessufferedbyMURinconverting EurostoUSDollars.MURdeniedthis offer and insisted on its right to receive payment in US Dollars, refusing to continue nominating vessels otherwise. Unable to agree on this point, the parties commencedarbitration.

The arbitrators, and the parties, had no problem accepting that the sanctions would have ordinarily constitutedaForceMajeureEvent.

However, Clause 36.3(d) of the contract added an additional criterion that purported Force Majeure Events had to fulfil—that they could not “be overcome by reasonable endeavours from the Partyaffected.”

The recent case of RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV[1] offers a valuable insightintocorevaluesinthelawof contract through the lens of force majeure and “reasonable endeavours” clauses. However, although it attempts to uphold the sanctity of the parties’ legally binding agreement, the case raises potential issues for the law of currency,theeffectsofforcemajeure events and the interpretation of contractualterms.

It is here that we come to the key legal issue in this case. The question for the arbitrators (and the judges afterthem)waswhether“reasonable endeavours” in Clause 36.3(d) included accepting RTI’s noncontractual offer to pay in Euros. Certainly, MUR would have suffered no financial detriment, due to RTI’s offer to bear the costs and losses of converting Euros to US Dollars—so had MUR failed to make “reasonable endeavours” by rejecting RTI’s offer? The arbitrators decided that it had, and that it had therefore breached thecontractbyrefusingtonominate vessels.

The very same question arrived for determination at the Supreme Court, whereupon it received a unanimous answer penned by Lords Hamblen and Burrows. They found that “reasonable endeavours” to overcome a force majeure event would not extend to accepting an offer of non-contractual performance, unless there were clearwordstothateffect.2

The Supreme Court broke new ground in this case. Previously, the question of whether a “reasonable endeavours” proviso in a force majeure clause could include having to accept performances that were not provided for by the contract had never been answered by an English court.3

The Court noted that it was “a very common feature” of force majeure clausesthatthepartyinvokingthem could only do so if the event or state of affairs was beyond its reasonable control and could not be avoided by reasonablesteps.4

Following from that, the Supreme Courtreasonedthatevenifclause36 of the contract had not contained a “reasonable endeavours” proviso, it would have been interpreted as containing one. The general applicability of this holding has been criticised,aswillbeexaminedbelow.

5

Thisrepresentedanotabledeparture from the approach adopted by the Court of Appeal in the same case. TheCourtofAppealhadapproached the case with a view to interpreting the words of the specific contract between the parties. According to Males LJ, the force majeure clause “should be applied in a common sense way which achieves the purpose underlying the parties’ obligations”.6

Males LJ then proceeded to resolve the case based on interpreting the wording used by the parties, with particular focus on the meaning of the word “overcome”. The other judge in the majority, Newey LJ, broadlyconcurredinthisapproach.

7 8

The majority of the Supreme Court heldthatthemajorityoftheCourtof Appeal had been wrong to focus on the specific reasonable endeavours proviso in the instant case. Such a decision, they held, would end up being applicable to force majeure provisionsgenerally. 9 10

The question of law which arose in this case was novel and lacking in directly applicable authority. Four broad principles supported the Supreme Court’s decision to rule in favourofMUR.

First, the purpose of the reasonable endeavours proviso was to maintain contractual performance, not substitute alternative performance. Torelyonaforcemajeureclause,the relying party must show that the force majeure event caused a failure to perform, which could not have been avoided through reasonable steps towards the continuation or resumption of the contractual performance. The reasonable endeavours proviso was not concerned with whether different steps could or should have been taken to achieve a different, noncontractualperformance.

11 12 13

Second, the fundamental principle of freedom of contract included freedom to choose not to accept the offer of a non-contractual performanceofthecontract.14

Third, clear words were needed to allow a party to forgo valuable contractual rights and accept noncontractualperformance.15

It is a general principle of contractual interpretation that parties do not forgo valuable contractual rights unless the contract makes clear (expressly or impliedly) that that is their intention. MUR had a contractual right to be paid in US Dollars, and to refuse payment in any other currency, and the wording of clause 36 was not sufficiently clear to allow them to forgo that right in favour of non-contractualperformance.

16 17

The recent case of RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV[1] offers a valuable insightintocorevaluesinthelawof contract through the lens of force majeure and “reasonable endeavours” clauses. However, although it attempts to uphold the sanctity of the parties’ legally binding agreement, the case raises potential issues for the law of currency,theeffectsofforcemajeure events and the interpretation of contractualterms.

Fourth, certainty in commercial contracts required strict adherence to the terms of the contract. MUR’s case was tied to the contractual wording (or rather, the lack of clear wording to the contrary): the focus of the “reasonable endeavours” inquiry was what steps could reasonably be taken to ensure contractual performance, and the limits of that inquiry were provided by the contract. In contrast, the Court criticised RTI’s case for being “not anchored to the contract”, raising a number of questions and “giv[ing] rise to considerable legal and factual uncertainty. The determination of “reasonable endeavours” could not involve departure from the contractual wording and from contractually required performance, or additional uncertaintywouldarise.

18

19

Hose has been critical of the Court’s approach. He writes that the court should have taken the orthodox approach to interpretation: determining what the parties objectively intended by the term, and placing analysis of the specific language before generic arguments of principle (as Males LJ did in the Court of Appeal). In deviating from the textual approach, the court failed to give effect to the parties’ freedom of contract, and “sent a potentially dangerous signal” that textual analysis was unimportant when dealing with commonly appearing contractual terms. Day and Foxton, likewise, have preferred the approach taken by Males LJ, placingfocusonthedefinitionofthe word “overcome” and interpreting it to include not only preventative but alsomitigatoryefforts. 21 22 23

It is advised that the Supreme Court’s “commonly used clause” approach in this case should be restricted as far as possible to the area of force majeure clauses. Excessive expansion to other types of (potentially less) commonly-used terms would risk subverting the intentionsoftheparties,andinfringe on their freedom to vary even regularly-occurring contractual terms through their own choice of wording.

The recent case of RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV[1] offers a valuable insightintocorevaluesinthelawof contract through the lens of force majeure and “reasonable endeavours” clauses. However, although it attempts to uphold the sanctity of the parties’ legally binding agreement, the case raises potential issues for the law of currency,theeffectsofforcemajeure events and the interpretation of contractualterms.

24 25 26

Day and Foxton note that the Supreme Court had not considered theconvertibilityofmoneyfromone currency to another in their judgement. Thelawhasrecognised the convertible nature of money by allowing obligations measured in one currency (the “money of account”)tobeperformedinanother currency (the “money of payment”) unless the contract stipulates otherwise. While the money of account in this case could rightly be restricted to US Dollars, there was a farweakercaseforimplyingthatthe contract had taken a similarly firm lineastothemoneyofpayment.

The Court, unfortunately, had not considered this aspect of the payment obligations sufficiently, and it was doubtful whether payment in a different currency could truly be considered “non-contractual performance”. Allowing the RTI to make payment in a different currency could provide a coherent andpracticalsolutiontoovercoming force majeure events, while preservingthecontractbetweenthe partiesandgivingeffecttowhatthey might consider commercially sensible(i.e.,thatmoneyofpayment isconvertible). 27 28

Inhercasenote,Goldbycritiques RTI for implicitly suggesting that the force majeure event does not need to cause non-performance by one party in order for the other party to rely on it to escape the contract. MUR was therefore able to take advantage of the force majeure clause to escape a bad bargain it had freely entered into. This was arguably contrary to the purposes of force majeure clauses, and raises questions about force majeure clausesonawiderscale.

The Supreme Court dismissed an analogy between force majeure clauses and frustration in RTI. However, they are similar in that they excuse contracting parties for non-performance of their obligations where said nonperformancewascausedbyexternal events outside their control, and must therefore be narrowly applied. Excessively broadening the application of force majeure clauses, and making them too easy to rely on, risks undermining the sanctity of contractual agreements andallowingterminationintoowide a range of circumstances. This outcome may reduce certainty in commercial contracting, and cut across the very considerations of general principle which motivated the Supreme Court to reason as it didin RTI.

The recent case of RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV[1] offers a valuable insightintocorevaluesinthelawof contract through the lens of force majeure and “reasonable endeavours” clauses. However, although it attempts to uphold the sanctity of the parties’ legally binding agreement, the case raises potential issues for the law of currency,theeffectsofforcemajeure events and the interpretation of contractualterms.

Day and Foxton also warn that a blanket exclusion of “noncontractual performance” from “reasonable endeavours” provisos may be over-broad. In other cases, “reasonable endeavours” taken to mitigate the effects of a force majeure event may involve as great a part of the obligation as possible, evenwhereitwouldstopshortoffull performance. For instance, in a contract for sale of goods where a scarcity of supply rendered full performance impossible, the seller might nevertheless have to deliver as large a quantity as possible (though not the full quantity contracted for). The Court’s judgement therefore risks excessively restricting the scope of “reasonableendeavours”. 34

RTI Ltd v MUR Shipping BV may have been a case about force majeure clauses, and one way of (not) sidestepping them. However, the general considerations underlying the decision go to the very heart of the law of contract. Above all, it is a case about the certainty, essentiality and enforceability of the obligations provided for by agreement in a contract. Lords Hamblen and Burrows illustrate that the core of the law of contract is the agreement between the parties, and that it shouldgiveeffecttothatagreement asfaraspossible. .

Yet, in arriving at this result, the Supreme Court departed entirely from the textualist orthodoxy. It focused on general considerations over the specific wording of the contractual term to formulate a general rule applicable to all force majeure clauses. It also failed to consider the ways in which the case interacted with the law of currency. Furthermore, in its analysis of force majeure clauses, the Supreme Court risked allowing force majeure clauses to be used to excuse nonperformance of commercial bargains too lightly, while opening the door to a potentially over-broad reading of “non-contractual performance”. This may undermine commercial certainty and weaken the binding force of the agreement between the parties, contradicting the very reliance upon those values which the Court used to support its

outlined above, the approach of the Supreme Court in this case should be limited in its application. It is essential that RTI should not become an unfortunate own-goal in the application of its own core doctrines to force majeure clauses, an all-too-common feature in commercialcontracts.

Notes

1.[2024]UKSC18,[2024]2WLR1350.

RTI (n1)[102]. 2. RTI (n1)[60]. 3. RTI (n1)[26]. 4. RTI (n1)[29]. 5. RTI (n1)[18]. 6. RTI (n1)[18]-[20]. 7. RTI (n1)[21]. 8. RTI (n1)[30]. 9. RTI (n1)[30]. 10. RTI (n1)[38]. 11. RTI (n1)[37]-[38]. 12.

RTI (n1)[38]. 13. RTI (n1)[41]. 14.

RTI (n1)[44]. 15. RTI (n1)[44]. 16. RTI (n1)[45]. 17. RTI (n1)[48]. 18. RTI (n1)[49]. 19. RTI (n1)[57]. 20.

23.

21. 22.Hose(n21)435-436. William Day and David Foxton, ‘Gold, Banking CentsandMur’(2025)141LQR13,18.

25.

Christopher Hose, ‘You Get What You Pay For: Reasonable Endeavours and Force Majeure’ (2024)83(3)CLJ433,434-435.

24.DayandFoxton(n23). Day and Foxton (n 23) 15; Barclays Bank International Ltd v Levin Brothers (Bradford) Ltd[1977]QB270,277-278.

26.DayandFoxton(n23)15.

27.DayandFoxton(n23)16-17.

29.

28.DayandFoxton(n23)18. Miriam Goldby, ‘Force Majeure in the Supreme Court: MUR Shipping BV v RTI Ltd [2024] UKSC 18’(2024)44LS748,751-752.

30.Goldby(n29)752.

31.Goldby(n29)751-752. RTI (n1)[92]. 32.

33.Goldby(n29)752.

34.DayandFoxton(n23)17-18.

We consider the following relevant factors when selecting which submissions to publish. It is important to note, however, that this is not an exhaustive list of all relevant considerations. We encourage readers to reach out to the Per Incuriam team if they have any questions or suggestionsregardingourpolicy:

(1) The mark achieved on essay beingsubmitted

We aim to publish the highest quality work to help current and future students prepare for their exams.

(2) Whether the student has had an exam essay published in the past

We aim to ensure diversity of contributors, offer a wider range of styles and illustrate the different ways in which a first-class mark can be achieved.

(3) The year in which the student sattheexam

We aim to publish recent work to ensure that the law discussed and cited remains current and does not confuse students.

(4) Whether we have recently and/or frequently published exam scripts in the paper in whichthemarkwasachieved

We aim to publish sample answers in a wide range of papers to help current and future students in as many different papers as possible to prepare for their exams. Although we are particularly keen on publishing essays from less popular papers, our ability to do so is dependent on receiving essay submissions for those papers. o. Maestro agrees to these terms.

(5) The type of question (essay questionorproblemquestion)

We aim to publish sample answers dealing with a wide range of question-types within each paper to ensure that current and future students may better familiarise themselves with the range of questions that might arise in the exam.

Rowan Lightfoot

Mark: 80

‘Scotland cannot be given more autonomy without converting the UK into a federal state.’ Discuss.

Introduction

This essay will argue that the possibility of the UK becoming a federal state through increased Scottishdevolutionishighlyunlikely. Although Scotland does possess the strongest legislative competencies of the devolved nations, there is still a long way to go before the UK system could be characterised as federal. For this conversion to occur, structural as well as merely powerbased change would be needed. I shall start by assessing the current devolution settlement with Scotland, before moving on to the possibility of extension and the followingunlikelyshifttofederalism.

The current devolution settlement with Scotland

It is common consensus amongst Constitutional lawyers that Scotland, out of all devolved nations and regions in the UK, possesses power to the greatest extent. The devolution-based agenda of the New Labour Government,electedin1997,beganthe transferofpowersfromWestminsterto Holyrood. A 1998 referendum saw the Scottish electorate vote 74.29% in favour of establishing a Scottish Assembly, which led to the passing of theScotlandAct1998.Aswellassetting up a Scottish Parliament and Government, this saw the beginning of the devolution of legislative competency to Scotland. S29 of the Scotland Act gives the Scottish Parliament general legislative competencyoveranymatterswhichdo not lay outside of the legislative competence. The competency limits concern inter alia matters outside of Scotland, reserved matters, incompatibility with convention rights andrestrictionsovertheroleoftheLord

iadvocate. Schedule 4 lists certain matters which are outside of the competency: certain articles of the act of union, the HRA 1998, the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and the UK InternalMarketAct2020.Inaddition, schedule 5 limits the Scottish competency on reserved powers, whichincludethecrown,union,High courts,Foreignaffairsanddefence.

Although prima facie the limitations may seem broad, in reality the Scottish Parliament, even from the initiationofthedevolutionprocessin 1998, did possess a broad range of general legislative competencies. They could legislate on education, healthcare, transport, social-care; all areas which have a significant impact on the lives of citizens. This impactwasonlyexacerbatedastime went on. As Ron Davies famously said, devolution is a ‘process not an event’, and this is certainly true of Scotland. The Calman Commission followed by the Scotland Act 2012 gavetheScottishParliamentincome tax varying powers, powers over property tax and the government greater borrowing power up to five billion pounds. This trend was continuedthroughthe2016Scotland Act, which further extended income taxpowers,competenciesoversocial security and recognised the permanence of the Scottish parliament. The extent of these changes was significant, with Mark Elliot describing the development as making Scotland ‘fiscally autonomous of the UK to an unprecedenteddegree’.Despitethis, theassertionthatgivinganymore

autonomy to Scotland would ‘convert the UK into a federal state’ seemsblindtotherequirementsand characteristics of such a state. I shall nowmoveontotestthefeasibilityof thisassertion.

It is helpful at the outset of this section to outline some common features of federalism. Federalism is generally regarded as the sharing of sovereignty between the central ‘federal’ state and subdivisions. Examples of this system include the USA and Germany, and although each have a relatively unique constitutional makeup, there are some paradigmatic similarities. Both value the centrality of a written constitution which regulates the relationship between the federal centre and the states. Both systems arose out of a significant political event which necessitated the creation of a new state. Both have largely, if not totally, symmetrical powers between the subdivisions. In light of these observations, it seems the characterisation of the UK as a federalsystemintheeventoffurther Scottish devolution would be unlikely.

As noted above, areas in which Scotlandcouldbegivenmorepower include foreign policy, war, Human Rights and EU membership. This suggeststhatthereisagreatdealof latitude for the UK government to further devolve powers to Scotland. Ignoring for a moment the political limitations on such a move, I shall hypothesise that Scotland were givenallthesepowers.Thiswould

essentially leave the only power still vested in the Westminster government as the physical maintenanceoftheunion.Usingthis hypotheticalscenario,itcanbenoted that even after this extreme devolution,theUKsystemwouldnot be federal. Firstly, the system would still be asymmetric. A key characteristic of federalism is that all states possess the same powers. Although there is variance as to how they employ said powers, their competencies are identical. This would not be the case in the UK; Wales and Northern Ireland would stillpossessthesamepowersasthey hadpriortothefurtherdevolutionto Scotland. This would deepen the current asymmetry to a point which is unrepresentative of a system whichcouldreasonablybedescribed as ‘federal’. Secondly, the constitutional security of the UK arrangement would be much weaker than that of other federal states. The uncodified character of theUKconstitutionleavesdevolution largely at the mercy of political constitutionalism. There are very few legalsafeguards,withtheonlyquasilegal safeguard being the Sewelconvention, which status as legally enforceable is highly disputed. The transfer of greater powers would not change this fact; the ‘federal’ arrangement would be insecure and vulnerable to centralised power, which is exactly what a federal system serves to resist against. Thirdly, the route by which the hypothesised system emerged would not match that of other federal states. Generally, as Elliot notes,federalsystemsemerge

through a ‘bottom-up’ approach, with states surrendering powers to the federal government. Devolution charts the opposite course, with the centralised states surrendering power to the regions and nations. This further creates dissonance between the hypothetical scenario and a secure characterisation of a ‘federalstate’.

Therefore, it seems that even if Scotland were afforded a great deal of further powers, the UK system could not be described as federal. It lacks the structural features of a federal state, and the presence of other asymmetrical settlements would further this assertion. The change would merely further the extend to which the UK can be described, as Bogdanor has, as a ‘quasi-federal state’. The extensive powers devolved to the region may ‘appear as’ creating federalism, but upon closer inspection, the characterisationisinaccurate.

This essay has argued that Scotland can be given greater autonomy without converting the UK into a federal state. The UK’s constitutional framework and method of devolution does not align with that synonymous with a federal state, and an unachievable level of constitutional and political upheaval wouldbenecessarytoensuresucha descriptionisaccurate.

Harry Marsh | Mark: 72

Hogston is a seaside village surrounded by agricultural land. Two years ago, Ruddick, a wealthy investment banker, bought land in Hogston that had previously been used to grow crops. Upon securing a planning permission, Ruddick built at great expense several cottages on the land to rent out. Ahmed owned a large estate close to Ruddick’s land. Ahmed had allowed pheasant shoots to take place on his estate several times a week for many years. Owing to the sound of gunfire and the sight of dead birds, Ruddick was unable to rent out many of the cottages. Ruddick managed to rent one of the cottages (called ‘Flora’) to Padma, an 80-year old deaf woman, for four months. Padma complained that Asian oxen, kept by Owen in a nearby farm, were exceptionally smelly and that the smell affected her sleep. During last year’s summer months, Maeve, Ruddick’s daughter, stayed for free in another of Ruddick’s cottages (called ‘Lily’). For three weeks during those months, a group of activists, who were unhappy with Ruddick’s investment bank’s practices, camped in Dermot’s garden, which was located next to the ‘Lily’. The activists chanted against Ruddick from early morning until late afternoon. Dermot did not try to remove the activists from his land because he hated Ruddick. Maeve was upset that the activists spoiled her holiday. In response, Ruddick installed a video surveillance system on the roof of the ‘Lily’. The camera records

Dermot entering and leaving his house. After the activists had left, Dermot cut down some old trees on his land, collected them at the end of his garden, and started a fire to burn them. The fire escaped onto Elizabeth’s land and destroyed her pine tree, which she had decorated every Christmas. Advise the parties of their rights and liabilities in tort.

Ahmed’s liability:

Ahmed (A) may be liable to Ruddick (R)underprivatenuisance.

Lord Lloyd in Hunter v Canary Wharf [1997] set out 3 different forms that private nuisance can take. This was nuisance by encroachment on C’s land, nuisance by direct physical injury to C’s land and nuisance by interference with the enjoyment of C’s land. This would be an interference with the enjoyment of land.

C cannot sue in nuisance if the only damage they suffers is a fall in the value of the land. (Network Rail Infrastructure Ltd v Williams [2018]). This would likely mean R could not claim for not being able to rent out theproperties.

Fearn [2023] stated that the interference must be (1) substantial and (2) an interference with the ordinaryuseofC’sland.

What constitutes substantial interference is assessed objectively by the standards of an ordinary person in C’s position. The interference must exceed the minimum level of seriousness. The intensity, duration (Bamford v Turnley (1860)) and the timing of interference are all relevant. Shoots on the estate several times a week is likely substantial. C cannot complain if his use of the land interfered with is not an ordinary use (Robinson v Kilvert (1889)). Renting out properties to live on is likely an ordinary use of land. Where D’s activity substantially interferes with C’s ordinary use of land, it will still not give rise to liability if D’s activity isanordinaryuseoftheirland(Fearn [2023]). For this to apply 2 conditions must be satisfied. These are that D’s actisnecessaryforthecommonand ordinary use of land and that D’s act is conveniently done (ie done with proper consideration for the interests of neighbouring occupiers). Neitheroftheseapply.

There will be no nuisance if the nuisance is in the character of the locality (Sturges v Bridgman (1879)). It is likely within the character of a seaside village surrounded by agriculturallandthattherewouldbe pheasantshoots.However,therecan still be a nuisance if the nuisance goes beyond that expected in that area. Shoots multiple times a week likely goes beyond what would be expectedinthearea.

Coming to the nuisance is not a defence (Coventry v Lawrence [2014]). When there is a change in theuseoflandbyC,theissueis Page 31

whether an alteration in C’s property after the activity in question has started can give rise to a claim in nuisance if the activity would not have been a nuisance had the alteration not occurred. The activity would not have been a nuisance if the land was still used for crops so there possibly cannot be a claim, despite the planning permission. Planning permission as a defence onlyservesDratherthanC.

D is only liable for reasonably foreseeabletypesofloss(TheWagon Mound (No 1) [1961]). It is reasonably foreseeable from the shoots that R would not be able to rent out some oftheproperties.

C must have a proprietary interest in the land and must enjoy exclusive possession of the land (Hunter v Canary Wharf [1997], Dobson v Thames Water Utilities Ltd [2009]). R hasthisastheowner.

D may have the defence of prescription where they have committedthenuisancefor20years without complaint. Therefore, D would have a defence if ‘many years’ metthis.

C may claim damages, measured according to the diminution in the value of the land (Hunter v Canary Wharf [1997]). R may therefore claim in the loss of value due to not being able to rent out the houses if A is liable. Courts calculate the damages for intangible nuisance by using the actual impact on occupiers as a practical guide rather than a formal measure.

Dobson v Thames Water Utilities Ltd [2009] affirmed Hunter v Canary Wharf[1997]instatingthatdamages do not increase according to the number of people occupying the land. Therefore, damages would not increase for the increase in populationontheland.

C may be awarded an injunction against D. Coventry v Lawrence [2014] stated that the prima facie an injunction should be granted but it should be easier than before in Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting[1895]forthecourttoaward damages. The Supreme Court also stated here that the public interest (and planning permission considering the public interest) should be taken into account in the exercise of the discretion. The court may therefore award damages instead of an injunction if the pheasant shooting was found to be inthepublicinterest.

O would likely be liable to P and R under private nuisance for the interference with the use or enjoyment of the land due to the smell (especially through disrupting P’ssleep).

The interference here is likely substantial due to the ‘exceptional’ smell (Adams v Ursell [1913]). The keeping of Asian oxen is not an ordinary use of land. However, havingoxeninanagriculturalareais likely within the character of the locality so there may not be a nuisance.

Coming to the nuisance is not a defence as stated above so P could still claim. (Coventry v Lawrence [2014]).

There will be no nuisance if there is onlyanuisanceasC’suseoftheland is hypersensitive (Robinson v Kilvert (1889)). P’s deafness would not maker her hyper-sensitive to smell sothisdoesnotapply.

D is only liable for reasonably foreseeabletypesofloss(TheWagon Mound (No 1) [1961]). Worse sleep is a foreseeable consequence of bad smell.

Activist’s and Dermot’s liability to Maeve (M) and R and R’s liability to Dermot

The activists and Dermot could be liableunderprivatenuisance.

M is unlikely to be able to sue as she does not have a proprietary interest inthelandassheisstayingforfree.

The use of land here is likely substantial as the ordinary person would see such activism as substantial. The use of land is not ordinaryduetotheactivism.

The rule in relation to acts of strangers is that an occupier continues the nuisance if with knowledge or presumed knowledge of its existence he fails to take any reasonable means to bring it to an end though with ample time to do so. He adopts it if he makes any use of the thing which constitutes a nuisance (Sedleigh-Denfield v O’Callaghan [1940]). Dermot could be argued to have adopted the nuisance if he is seen to have made use of the activism to annoy his neighbour who he dislikes though this is unlikely. However, he has failed to take reasonable measures to bring the activism to an end to would likely be continuing the nuisance.

P has a proprietary interest in land as a tenant and enjoys exclusive possession of the land so could claim.Rcouldalsoclaim.

P may claim for damage or an injunction.

Dwouldlikelythereforebeliable.

The activists could also be liable as there is no requirement that D is the owner or occupier of the land, so a trespasserorlicenseecouldbeliable.

R could claim damages or an injunction as stated above, though thepublicinterestduetotheprotest maypreventaninjunction.

Dermot may be able to claim under private nuisance for the cameras as this is likely substantial and the ordinary person would see viewing someone entering and leaving their house as substantial. Such a surveillance system is also not an ordinaryuseofland.

D has a proprietary interest in the land and has sole possession as the ownersocouldclaim.

In Fearn v Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery [2023], the Supreme Court unanimously held that intrusive overlooking can amount to nuisance; but some degree of being overlooked from neighbouring properties is a normal feature of life and bound to be tolerated. This is likely not an ordinary degree of overlooking as the camera records every entry and exit from the house. This militates towards a finding of nuisance.

Malicious intent makes interference morelikelytobeanuisance(Christie v Davey [1893]) so the cameras in response to the protest are more likely to be a nuisance. Dermot may claimdamagesoraninjunction.

Dermot’s liability under Rylands v Fletcher (R v F)

ThedefinitionofthetortinRylandsv Fletcher (R v F) defined in Rylands v Fletcher (1866) and restated in Transco plc v Stockport MBC [2004] statesthat‘[a]noccupieroflandwho can show that another occupier of land has brought or kept on his land an exceptionally dangerous or mischievous thing in extraordinary or unusual circumstances is… entitled to recover compensation from that occupier for any damage caused to his property interest by theescapeofthatthing’.

Ward LJ in Stannard (t/a Wyvern Tyres) v Gore [2012] extracted the following framework of liability under R v F. D must be the owner or occupier of the land. Dermot is the owner. D must bring or keep or collect an exceptionally dangerous or mischievous thing on his land. The Court of Appeal in Stannard (t/a Wyvern Tyres) v Gore [2012] ruled thatfireisonlybroughtontolandfor the purposes of R v F if the fire is deliberately or negligently started. The fire was deliberately started so Dermot has brought an exceptionally dangerous thing on to the land. D must have recognised or ought reasonably to have recognised, judged by the standards appropriate at the relevant place and time, that there is an exceptionally high risk of danger or mischief if that thing should escape, however unlikely an escape may have been thought to be. Dermot should have recognised such a risk fromfire.

D’suseoflandmust,havingregardstoallthecircumstancesoftimeandplace, be extraordinary and unusual. Starting a fire to burn some old trees is an extraordinary and unusual use of land. The thing must escape from D’s property into or onto the property of another. The fire did escape on to Elizabeth’s (E) property. The escape must cause damage of a relevant kind to the rights and enjoyment of C’s land. Damage to the pine tree would suffice. Damages for death or personal injury are not recoverable (Transco plc v Stockport MBC [2004]) and C can likely not recover for pure economic loss (D Pride&PartnersvInstituteforAnimalHealth[2009]).Thiswouldnotapplyhere as the damage would be for the pine tree. It is not necessary to establish D’s negligence but an Act of God or act of a stranger will provide a defence. There isnoactofGodoractofastrangerhere.Therefore,DislikelyliableunderRvF.

OnlythosewithaninterestinthelandcansueasbecauseRvFisasubspecies of private nuisance (Cambridge Water Co Ltd v Eastern Counties Leather plc [1994], Transco plc v Stockport MBC [2004]), the restrictions in Hunter v Canary Wharf[1997]shouldapply.Eistheownersocanclaim.

Theactivistsmaybeliablefortrespasstoland.

“A trespass occurs when there is an unjustified intrusion by one party upon land which is in the possession of another.” (Bocardo SA v Star Energy UK Onshore [2011] (per Lord Hope)). The intrusion must be direct. The activists camping in the garden would be a direct intrusion. The entry must be intentionalratherthanthetrespass.Theentrywasclearlyintentional.

The activists may have the defence of permission as they were not removed. However, this would likely not apply as they were never actually given permissionandDermotwasnotawarebeforethetrespass.

C must have or be entitled to possession to sue. Dermot clearly has legal

Liew Li Ren I Mark: 79

In January 2023, four siblings – Connor, Kendall, Shiv and Roman – each inherited £500,000 on their father’s death.

In February 2023, Connor, an actor, bought ‘Logan View’ for £500,000 using all of his inheritance, as somewhere to stay whenever he visited London. In March 2023, he entered into a whirlwind relationship with Adam, and told him ‘I think you could be my forever man; please make Logan View your home’. Adam was delighted; he served a notice to quit his existing tenancy, with a view to moving into Logan View properly in May 2023, when Connor was back from filming abroad. In the meantime, Adam, with Connor’s agreement, paid for a new kitchen and bathroom to be installed at Logan View, at a cost of £50,000; Adam also moved some of his belongings into Logan View. Inspired by Adam’s home improvements, Connor told Adam that he would renovate the rest of Logan View, to be funded by a £100,000 mortgage loan from Waystar Bank. Adam was pleased to hear Connor’s plan. In April 2023, Connor duly obtained a £100,000 mortgage loan from the Waystar Bank, secured by a registered charge over Logan View. In May 2023, Adam moved into the property.

In June 2023, Kendall, Shiv and Roman, who all worked for their family business, pooled their inheritance money to buy Succession House, at a cost of £1.5 million, for their joint occupation. The registered freehold title to Succession House was conveyed to Kendall and Shiv expressly on trust for all three of them as equal tenants in common.

In October 2023, Kendall, a secret drug addict, persuaded Shiv to agree to the creation of a registered charge over Succession House to secure a £200,000 loan from Waystar Bank, at a 12% interest rate. Kendall insisted that this was ‘an essential business move’, to enable him to ‘pursue a personal business investment’; and that ‘there’s no need to bother Roman with this – he’ll certainly concur’. Shiv accepted Kendall’s proposal in principle, assuming that Kendall knew what he was doing in financial matters. Although the bank advised Shiv to seek independent legal advice, she said ‘there’s no need: I haven’t got the time and, in any case, I trust Kendall implicitly’. After Shiv signed the relevant documents, Waystar Bank paid the money into Kendall’s personal bank account and registered its charge. Kendall proceeded to use all £200,000 to fund his drug habit.

Since then, the following problems have arisen:

In October 2023, having been out of work for seven months, Connor became unable to make any monthly mortgage repayments. Waystar Bank now plans to obtain possession of Logan View, and then sell the property, by a private sale, to the Waystar Bank’s manager’s cousin, Greg, for £500,000 (similar houses on the street have recently sold for between £500,000 and £600,000). Connor is eager to resist Waystar Bank’s plans, claiming that ‘acting work is just around the corner’. Adam asserts that the Waystar Bank mortgage does not affect him.

Since November 2023, no monthly repayments have been made in respect of Succession House to Waystar Bank. Waystar Bank has just informed Kendall, Shiv and Roman of its intention to obtain possession and sell the property. Shiv and Roman protest, saying ‘this is deeply unfair – we haven’t seen a penny of Waystar Bank’s money, and this is our home’.

Advise Waystar Bank as to whether it can proceed as it intends. If either property were sold, how would the sale proceeds be divided?

Whether Adam has acquired an equitable interest in Logan View

Since equity follows the law, since Connor is the sole registered title holder, the starting point is that the entire equitable ownership rests in him(ThomsonvHumphrey);thiscan berebuttedbymakingsomeformof

financial contribution for a resulting trust or as common intention for a constructive trust (Oxley v Hiscock), or by express discussions (Lloyds Bank v Rosset). Straightforwardly, Adam cannot acquire an interest in the property via resulting trust because he has made no contributiontothepurchasepriceof thepropertydespitespending

money to renovate the house; contributions to repairs or renovation are not counted (Bank of IndiavMody).

Adam’s interest may arise under a common intention constructive trust. Common intention may be shown by express agreement by parties that the property should be shared beneficially (Kahrmann v Harrison-Morgan). It is plausible that Conner’s statement to Adam to “please make Logan View your home” can amount to an express agreementthatAdamshouldhavea beneficial interest in the land. However, the better view is that Conner was clearly tentative (“I think”) and his promise to make Logan View his home can reasonably be interpreted as a bare license to stay at the house instead. Indeed, this was stated to be a “whirlwind romance” so it is unlikely that Adam can reasonably interpret this statement as giving a beneficial interest in the property that he hitherto has never stayed in and from a man who he only recently met.

Alternatively, if it can be accepted that the broadening of the common intention constructive trust to include contributions apart from contributions to purchase price as in StackvDowdenandJonesvKernott applies to single-name cases, then Adam’s 50k payment of the kitchen and bathroom would allow him to acquire a beneficial interest. Indeed, in Stack itself, Lady Hale suggested that “the law has moved on” from Rosset and subsequent cases have appliedStacktolikeAspdenvElvy.

Thus, the better view is that Stack v Dowden modifications do apply, notwithstanding judicial confusion, tosinglenamecases.

On this view, Conner’s statement, while not amounting to an express discussion in itself, in conjunction with Adam’s expenditure of 50k, as well as Connor’s undertaking to renovate the rest of Logan View (presumably so they can cohabitate together in an apartment of their joint design), would allow an inferenceofcommonintention.

Conner did also survive detrimental loss; by serving notice to quit on his existing tenancy, he is now be in a “substantially worse position” (Lloyds Bank v Rosset). Indeed, it does not matter if the Adam’s act might have been partly motivated by love and affection (Chun v Ho), so long as the claimant would have acted differently(CurranvCollins).

Dixon suggests, by analogy to proprietary estoppel, where detriment is suffered, reliance may be presumed (Greasley v Cooke). Alternatively, if that analogy is not apt, nonetheless on the facts there wasreliance,especiallyinlightofthe 50kpayment.

Thus, Adam would acquire an interestunderCICT.

For completeness, on the facts described above, Adam may also have acquired an interest under proprietaryestoppel.

Where a common intention as to acquisition of an interest is inferred, the court can also infer the size of the equitable interest (Oxley v Hiscock). Given the expenditure of 50k in relation to the total value of the house at 500k, it would be equitabletoawarda10%interest.

As the sole title holder, Connor does not need to seek Adam’s consent before mortgaging the property to WaystarBank.

The disposition to Waystar Bank from Connor to Waystar Bank triggers s 29 LRA because there is a registrable disposition of a registered estate made for valuable consideration, completed by registration, so prima facie Adam’s interest is postponed unless protected at time of registration (s 29(1)LRA).

Adam’s interest is protected from postponement if he was in actual occupation (s 29(2)(a)(ii), Schedule 3 Para 3) and that the actual occupation is obvious on a reasonably careful inspection of the land at the time of disposition (Schedule 3 Para 3(c)(i)). For simplicity,itisassumedthatWaystar Bank did not have actual knowledge of the occupation and so Schedule 3 Para3(c)(ii)LRAisnotengaged.

It must first be queried whether Adamisinactualoccupationto

begin with. This is because he only moved in in May 2023, whereas the charge was executed in April 2023. Nonetheless, he formed the view to occupy the building in February 2023,andbyanalogytoLinkLending vBustard),whereapositiveintention to occupy amounted to actual occupation,hemightbesaidtobein actual occupation. However, I think thisisaweakargument;Bustardcan be distinguished because the positive intention was to return to the property, whereas here the intention is only to move in for the first time. Nonetheless, a positive intention to return argument might bestrengthenedbyAdammovingin ofhisbelongings,sincethepresence of furniture does support a positive intentiontoreturn(BankofScotland vHussain).

For completeness, Adam moving in his belongings would not amount to actual occupation; mere presence of furniture does not count as actual occupation (Strand Securities Ltd v Caswell).

Even if it might be said he was in actual occupation, it is unclear whether that occupation was discoverable by way of him moving his belongings in. This is factsensitive to what belongings he did bringin.

Finally, even if it might be established that there was actual discoverable occupation, I think there is some argument to him having waived his priority implied. Adam may be taken to have authorised Conner as a trustee and sowaivedhisprioritytocompletethe

transaction by analogy to agency, where Adam knows they are not the legal owner (Wishart v Credit & Mercantile). This is supported by the fact that Adam was “pleased to hear Connor’s plan”; it is implicit that he approved of the plan and so waived hispriority.

On that basis, the mortgage does bind Conner. Thus, the Bank would be able to use their paramount powers under s 101 LPA to repossess thehouseandsellit.

Nonetheless, Connor and Adam can try to resist the possession order if it appears to the court that he is “likely tobeablewithinareasonableperiod to pay any sums due under the mortgage or to remedy a default” (s 36(1) Administration of Justice Act 1970 “AJA”) so that the court may adjourn proceedings as appropriate (s 36(2) AJA). This depends on the real possibility of Conner actually securing work and thereby being able to repay the mortgage repayments. In my view, this is unlikely given he has already been out of work for seven months and his suggestion that “acting work is just around the corner” seems doubtful and overly optimistic. It is likely he can only resist the possessionorderifheisabletoshow that he can secure a loan or gift, such as from Adam or his siblings, to paythedebtsdue.

Thus, Waystar bank is likely to be able to re-possess the property. It can then sell the property as its power of sale has arisen and is exercisable in light of the 7 month default.

However, Waystar is under an objective duty to take reasonable care to obtain true market value at timeofsale(CuckmereBrickCoLtdv Mutual Finance Ltd). While not inherently fraudulent, a sale to an associated person requires the Waystar to discharge a burden of proof that the sale was not fraudulent or at an undervalue (Tse Kwong Lam v Wong Chit Sen). It is unclear whether Greg is an associated person, since Greg is a cousin to an employee of Waystar. However,inconjunctionwiththefact that 500k is at the lower limit of houses sold in the area, it might be that they have not rebutted the presumption that the sale is at an undervalue and so have not discharged their duty to obtain true marketvalue.

Out of an abundance of caution, it is suggested Waystar should instead sell the property by open auction; Greg can attend the auction as a bidder.

Regarding sale proceeds, by operation of s 105 LPA, the proceeds first discharge all costs incurred by the sale, then in satisfaction of Waystar’s principal debt, costs and interest, and any residue thereafter to Adam and Conner in a 90-10 split reflectingtheirbeneficialinterests.

Kendall, Shiv, and Roman are all equitable tenants in common under an express trust. Kendall and Shiv arejointlegalowners.

Prima facie, since the mortgage conveyanceismadebytwotrustees, Kendall and Shiv for capital money (ss 2(1)(ii), s 27(2) LPA), Waystar Bank takes free of the equitable interest and Roman only has a beneficial interest in the monies received by the trustees. However, Shiv has not received the 200k, only Kendall. Where capital money is consideration for the conveyance, the monies must actually be received by trustees to overreach; it is unclear whether reception of just one trustee of the full capital money would satisfy overreaching. In my view,Iwouldthinksoifthepayment to Kendall’s personal account was prescribed under the relevant documents.

Assuming there is overreaching, sale proceeds are used to discharge the costs incurred by the sale and Waystar’s debts, without any account of Roman’s overreached interest; the residue is thereafter split equally between Roman, Shiv, andKendall.

However, there is a strong case that the mortgage may be rescinded for undueinfluenceofShivbyKendall.

It is unlikely actual undue influence canbeproven.

However, there is a factual relationship of trust and influence between Kendall and Shiv; indeed ShivassumesKEndallknowswhathe is doing in financial matters; this allows a presumption of undue influence to arise (Royal Bank of ScotlandplcvEtridge(No2))ifitisin conjunctionwiththetransactionthat callsforanexplanation.

Here the transaction is not easily explicable (Turkey v Awadh) because while it is framed as a essential business move, it is framed as only a business investment in respect of Kendall, not of Kendall, Shiv and Roman. Furthermore, the 12% interest rate seems high and so it would be manifestly disadvantageous to the claimants (PopowskivPopowski).