bellwether

The Zoonosis Issue

FALL/WINTER 2021-22

THE MAGAZINE OF PENN VET

FALL/WINTER 2021-22

THE MAGAZINE OF PENN VET

Members of the Class of 2025 pose at the “Ben on the Bench” statue on Penn’s campus during orientation. Photo by Isabel Rodriguez, V’24.

Members of the Class of 2025 pose at the “Ben on the Bench” statue on Penn’s campus during orientation. Photo by Isabel Rodriguez, V’24.

Penn Vet adheres to the CDC mask guidelines. Any unmasked people were vaccinated at the time the photo was taken or standing at a distance of more than six feet from others.

6 A Hub for Zoonotic Disease Research Penn Vet’s unique new Institute for Infectious Zoonotic Diseases 14 Pandemic Preparedness, Three Years Early A multidisciplinary approach to preparing students for global health disasters 18 Fighting on the Front Lines of Infectious Disease Colonel Eric Lombardini, C’93, G’01, V’01, battles threats overseas and in the U.S. 24 Supporting a Pipeline of Infectious Disease Experts The Martin E. Winter and Pamela Winter Infectious Disease Fellowship Fund Read Bellwether online at: repository.upenn.edu/bellwether Fall/Winter 2021-22 #96 2 DEAN’S MESSAGE 26 IN THE OFFICE 28 RESEARCH 30 SCHOOL NEWS 31 FACULTY NEWS 40 STUDENT NEWS 43 ALUMNI NEWS 46 IN MEMORIAM 48 CALENDAR Contents Departments

Dear Penn Vet Community,

The world is getting smaller. Humans (all 7.9 billion of us), animals, and the environment share one atmosphere, and a hierarchy of oceans and watersheds. Two- and four-legged animals, and our winged cohabitants, are tightly squeezed into habitable land (43% of total land mass). Pandemics result from people sharing environments with animals. Penn Vet was an early force in understanding and controlling zoonoses, such as bovine brucellosis, tuberculosis, and avian influenza. We could not be more grateful for and proud of the scholars at Penn Vet that have continued this great tradition of devoting their lives to the study of infectious diseases impacting billions of people and animals.

In recognition of these dedicated faculty and their research teams, we are launching Penn Vet’s first institute, the Institute for Infectious and Zoonotic Diseases (IIZD). This historical launch crystalizes three years of work by senior leaders and investigators at the School. They planned investments and convened scholars and centers across the School to strengthen our research, innovation, and training environment related to emerging, zoonotic, and vector-borne diseases. What differentiates IIZD is its attention to proximity and interactions between experts in globally and regionally important infectious diseases. The Institute serves as a unique regional hub of collaboration and communication, providing scholarship and guidance on area diseases that impact domestic, peri-domestic, and wildlife species in the Commonwealth.

2 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22 DEAN’S MESSAGE

“I WANT TO THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT OF OUR MISSION — WE COULD NOT BE MORE GRATEFUL FOR YOUR ENGAGEMENT AS ALUMNI AND COMMUNITY MEMBERS.”

DEAN ANDREW HOFFMAN

The new Institute joins 17 other Institutes at Penn (research.upenn.edu/centers-and-institutes/). The School, University, and region are excited about IIZD’s potential to transform the approach to infectious disease prevention, surveillance, and management in the Northeastern U.S., a global hot spot for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases.

The sky is the limit, from the discovery of new pathogens and understanding how they are transmitted, to the development of new animal vaccines and approaches to control vectors, to the creation of novel integrative training opportunities for veterinary students. And IIZD fills a critical gap in pandemic preparedness by incorporating a strong emphasis on zoonotic diseases.

Penn Vet is always evolving, from originating the now-pervasive specialties in veterinary medicine, to offering distinctive interdisciplinary dual degree opportunities, to addressing issues of sustainability, wellness, diversity and inclusion, and workforce development in our profession. We are fearless in asking questions, daring to generate new knowledge. And we’re undeniably energized — and focused — on preparing students to live and work in an interconnected, unpredictable world.

I want to thank you for your support of our mission — we could not be more grateful for your engagement as alumni and community members. I hope that this issue of Bellwether inspires you to continue the journey with us to be leaders in veterinary medicine and beyond.

EDITORIAL

Editor

Martin J. Hackett

Contributing Editor and Writer

Sacha Adorno

Writers at Large

Katherine Unger Baillie, Michele W. Berger, Martin J. Hackett

Class Notes Editor

Shannon Groves

Production Manager

John Donges

DESIGN

Associate Creative Director

Hannah Kleckner Hall

Designer

Anne Marie Kane, Imogen Design

Illustrator

Jon Krause

Photographers at Large

John Donges, Isabel Rodriguez, V’24

Contributing Photographer

Lisa Godfrey

ADMINISTRATION

Gilbert S. Kahn Dean of Veterinary Medicine

Andrew M. Hoffman, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM

Associate Dean of Institutional Advancement

Hyemi Sevening

Communications Director

Martin J. Hackett

Director of Alumni Relations

Shannon Groves

Director of Annual Giving

Mary Berger

Directors of Development

Margaret Leardi (New Bolton Center)

Helen Radenkovic (Philadelphia)

CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Sarah Trout

Office of Institutional Advancement

School of Veterinary Medicine

University of Pennsylvania 3800 Spruce Street Suite 151E, Philadelphia, PA 19104 strout@vet.upenn.edu 215-746-7460

Andrew M. Hoffman, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM

The Gilbert S. Kahn Dean of Veterinary Medicine

None of these articles is to be reproduced in any form without the permission of the School. ©Copyright 2021 by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The University of Pennsylvania values diversity and seeks talented students, faculty, and staff from diverse backgrounds. The University of Pennsylvania does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or status as a Vietnam Era Veteran or disabled veteran in the administration of educational policies, programs or activities; admissions policies; scholarship and loan awards; athletic, or other University administered programs or employment. Questions or complaints regarding this policy should be directed to: Executive Director, Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity Programs, Sansom Place East, 3600 Chestnut Street, Suite 228, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6106 or by phone at 215-898-6993 (Voice) or 215-898-7803 (TDD).

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 3

First Up...

THE SPILLOVER SPIRAL

Like many folks last summer, I got out of town, heading north to Maine to seek a reprieve from the Philadelphia region’s insufferable heat and humidity (and tornadoes). The heat, although not as intense as at home, was indeed there — and so was the humidity. On my agenda was a hike through Bald Head Preserve at the tip of Arrowsic Island, at the confluence of the Kennebec and Back Rivers. The solitude and the scenery were beautiful. The mosquitoes, not so much. They were relentless, tormenting the three of us as we hiked from Squirrel Point Light, through the 640-acre preserve, to Bald Head. It was a clarifying moment for me (“experiential” learning so to speak) that inspired how we would visually communicate the themes of this issue of Bellwether .

The role of sustained weather events on insect vectors; proliferation of infectious and zoonotic diseases; and inevitable spillover impacting humans, and animals, and landscapes — these issues are complex, connected, and scary. For the issue, I knew we needed a visual and imaginative vocabulary that simply conveyed these linkages. We found it in illustrator Jon Krause, whose work graces our cover and the feature story on Penn Vet’s new infectious disease institute. Krause, a Society of Illustrators gold medalist, captured so perfectly what we do here at Penn Vet. He got “us.” I do hope you take some time and linger on Jon’s illustrations. He gave us his best — and we are delighted with the result.

Enjoy the issue.

MARTIN J. HACKETT, EDITOR mhackett@vet.upenn.edu

4 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

Located on Arrowsic Island in Maine, Squirrel Point Light is one of four navigational aids dating back to 1895 along the Kennebec River’s 11-mile stretch between the Atlantic Ocean and Bath. The property is surrounded by 640 acres of land conserved by Maine’s Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife and The Nature Conservancy.

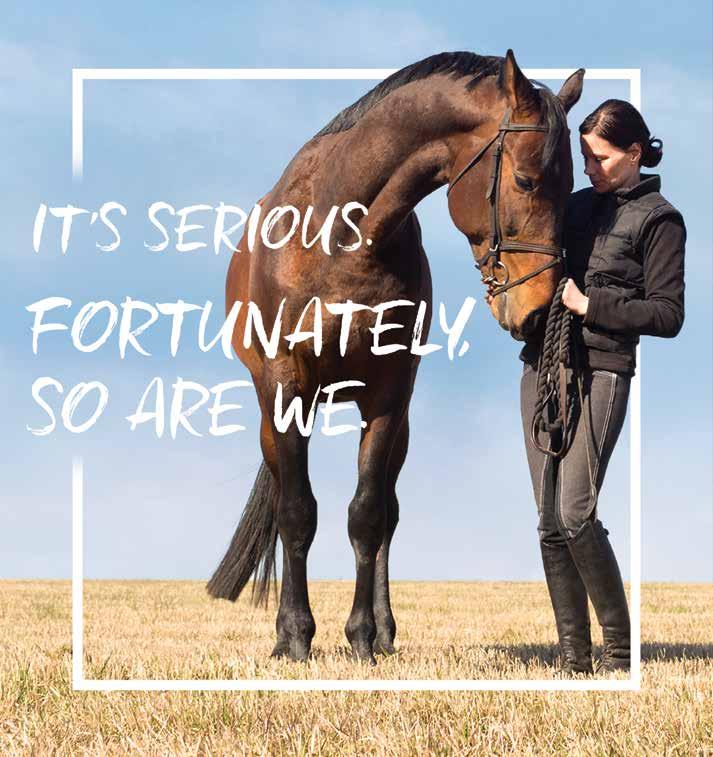

STATE-OF-THE-ART EMERGENCY CARE 24/7/365

For decades now, those in need of critical care have placed their trust in the hands of the region’s foremost veterinary emergency team. With five dual-boarded clinicians on call around-the-clock, at New Bolton Center, equine care is not just our profession. It’s our innermost passion.

For emergency services, call 610-444-5800 or visit us online at vet.upenn.edu/newboltoncenter

6 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

By Katherine Unger Baillie

Illustrations by Jon Krause

Illustrations by Jon Krause

The new Institute for Infectious and Zoonotic Diseases, launched by the School of Veterinary Medicine, leans on Penn’s strengths in immunology and infectious disease to prepare for emerging threats to animal and human health.

More than three-quarters of emerging infectious diseases that affect humans come from animals. Many scientists are confident that SARS-CoV-2 is among them, likely originating in bats. For many adults alive today, COVID-19 is not the first brush with a dangerous zoonotic disease, one that can move from animals into people. In just the last two decades, outbreaks of Ebola, Zika, swine influenza, avian influenza, and West Nile virus — among others — have occurred around the world, while other established infections, such as malaria and dengue, continue to be a global concern.

While COVID-19 understandably continues to command much of the world’s attention, scientists, veterinarians, physicians, and others are working to prepare for future threats. Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine is launching the Institute for Infectious and Zoonotic Diseases to address precisely these types of animaland human-health challenges by bringing together world-class expertise in infectious diseases, immunology, agriculture, veterinary medicine, and molecular diagnostics.

“We live in an infectious world,” said Christopher Hunter, PhD, the Mindy Halikman Heyer Distinguished Professor of Pathobiology at Penn Vet, who is serving as director of the Institute. “There are many emerging infectious diseases that are viewed as profoundly significant to public health, and the majority of these are zoonotic.”

By fostering strong partnerships within Penn and beyond — most notably with the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture and the Pennsylvania Game Commission, as well as other government bodies, foundations, and industry collaborators — the Institute aims to build expertise, enhance scientific understanding, leverage innovative technological approaches, and support the infrastructure needed to confront the next zoonotic disease outbreak.

“Because it’s not a matter of whether there will be another outbreak of one of these diseases,” Hunter said, “it’s when, where, and at what scale.”

BUILDING ON STRENGTHS

Far from starting from scratch, Penn Vet has a track record of success in research, technology-building, and training when it comes to immunology and infectious diseases. “Even prior to the pandemic, there were a lot of conversations about how we had something really unique at the vet school,” said Dan Beiting, PhD, assistant professor of Pathobiology. “But everyone was in their lab doing their own thing. There were no program project grants, no initiatives that linked together these different labs into something larger.”

One road map for determining the structure and scope of the Institute can be found within the School itself: the Center for Host-Microbial Interactions (CHMI), launched in 2013, for which Beiting serves as technical director.

“We developed a blueprint that the Institute will be able to use,” said Beiting, one of the associate directors of the new Institute. “The goal of CHMI was always

8 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

to lower the barrier for labs to access genomic technologies. Now we are going to bring that to bear on questions related to infectious diseases.”

Expertise on the microbiome will also factor into the Institute’s work on infectious diseases. “The microbiome can profoundly influence susceptibility to infection, while also contributing to inflammation and pathology in the gut and on the skin,” Beiting said. “We have a real track record and a research community prepared to really dig into how the microbiome influences the outcome of infection.”

Beiting sees great possibility in increasing the use of single-cell genomics to study disease. “Immune responses and host-microbe interactions can now be studied not at the tissue or organ level, but at the cellular level for unprecedented resolution,” he said.

And the tools that he and others at the vet and medical schools have been using to study microbiome communities — including shotgun metagenomics, which can capture genomic sequences of all microbes in one sample — could find powerful application in diagnostics. “Potential culprits, such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, can be identified without prior knowledge of what’s in a bit of stool, or a blood or tissue sample,” Beiting said.

IIZD leaders (l to r): Christopher Hunter, PhD; Lisa Murphy, VMD; Daniel Beiting, PhD; De’Broski R. Herbert, PhD; and Julie Ellis, PhD.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 9

BY FOSTERING STRONG PARTNERSHIPS WITHIN PENN AND BEYOND, THE INSTITUTE AIMS TO BUILD EXPERTISE, ENHANCE SCIENTIFIC UNDERSTANDING, LEVERAGE INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGICAL APPROACHES, AND SUPPORT THE INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDED TO CONFRONT THE NEXT ZOONOTIC DISEASE OUTBREAK.

PURSUING NEW QUESTIONS

Such new opportunities in diagnostics as well as surveillance play to existing strengths at Penn Vet. At New Bolton Center in Kennett Square for example, home to part of the Pennsylvania Animal Diagnostic Laboratory System (PADLS) and a base for disease surveillance for the state’s livestock producers, the Institute will channel new support and energy aimed at bolstering these capabilities, while fostering new connections between diagnosticians and basic science researchers.

“With the Institute we can bring the best of both worlds, both animal-focused research and human-focused research, together and cross-pollinate and collaborate,” said Dr. Lisa Murphy, resident director of PADLS New Bolton Center, co-director of the Wildlife Futures Program, associate professor of Toxicology, and an associate director of the Institute. “Because we already know that there is a lot of overlap between the diseases that affect humans and those that affect animals.” On a similar collaborative note, Murphy sees potential for sharing best practices. “At PADLS New Bolton Center what we have is situational awareness: we know what’s happening close by and regionally,” said Murphy. “I’m excited to find out, are there things happening in Pennsylvania that we can apply regionally and nationally and globally? And the reverse: what can we learn from what’s happening in terms of infectious disease, that human-animal interface, internationally?”

With a background in toxicology, Murphy is particularly interested in new investigations that consider how toxins in the environment may play a role in zoonotic infections. “Some toxicants can have more subtle, delayed, or chronic effects, such as on the immune system.” she said. “I’d like to see if we can start to tie together some of these factors and how they influence infectious disease susceptibility.”

She also expects to see diagnostic and disease surveillance approaches and technologies advance apace, with faster and more accessible techniques. As an example, Penn Vet scientists are working on a portable polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine to provide genomic capabilities in realtime, even in a field setting. More examples of this kind of out-of-the-box thinking are already playing out at Penn, for example, in tackling one of the state’s major challenges: chronic wasting disease (CWD), a prion-based, fatal illness that affects deer, threatening the economically and culturally important hunting industry.

In one project, the Penn Vet Working Dog Center’s Dr. Cynthia Otto and colleagues are training scent-detecting canines to sniff out CWD-positive deer, a feat that could help with containment. And in another lab-based effort, Penn Vet biochemist Anna Kashina, PhD, is receiving support to look for novel biomarkers of CWD.

“The goal is intervention, whether we’re looking at an infectious disease or a contaminant or how they interact,” said Murphy. “If we can identify some of these issues, it gives us a chance to intervene.”

10 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

“WITH THE INSTITUTE WE CAN BRING THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS, BOTH ANIMALFOCUSED RESEARCH AND HUMANFOCUSED RESEARCH, TOGETHER AND CROSSPOLLINATE AND COLLABORATE.”

DR. LISA MURPHY

THE WILDLIFE FACTOR

Whether the infection is CWD or COVID-19, one can’t study zoonotic diseases without factoring in the role of wildlife. While most people associate the Northeastern U.S. with a high population of humans rather than wild animals, the close proximity of metropolitan areas, agriculture landscapes, international ports, and natural lands can make the region a hot spot of zoonotic disease.

“The Northeast is kind of an unusual place,” said Julie Ellis, PhD, adjunct associate professor of Pathobiology, senior research investigator, and another associate director of the Institute who also co-directs the Wildlife Futures Program. “It’s the smallest region in the country yet has the highest human population density, and each state has its own border and regulations. There’s a lot of need for us to work together as a region, because wildlife don’t see those boundaries.”

As a partner and participant in the Institute, Wildlife Futures — itself a partnership between the vet school and the Pennsylvania Game Commission — presents rich opportunities to grow the scientific understanding of wildlife disease, leaning on both Penn’s depth in science and the expertise of Game Commission scientists in the ecology and biology of the state’s hundreds of wildlife species.

“As an example, right now we’re working with them to develop a new research program on SARS-CoV-2 in white-tailed deer,” Ellis said. “It’s an important topic and we’re going to be able to jump on that as a zoonotic disease issue.”

In another potentially fruitful project just getting off the ground, pulmonologist Dr. Nilam Mangalmurti of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine is conducting basic research into how red blood cells from bats respond to infection. Scientists from Wildlife Futures and biologists from the Game Commission are helping supply the bat blood samples.

“The Institute is helping us put together these kinds of cross-school collaborations and promote the type of interdisciplinary work that’s necessary to address challenging disease issues,” said Ellis.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 11

LOCAL SOLUTIONS, GLOBAL CAPACITY

Recognizing that infectious diseases are a global issue requiring creative and far-ranging collaborations, the Institute is supporting training and outreach efforts that extend from Philadelphia to Africa and South America to build capacity and expertise in immunology and infectious disease research for the next generation of scientists and veterinarians.

De’Broski R. Herbert, PhD, presidential associate professor in the Department of Pathobiology and another of the Institute’s associate directors, is heading up international affairs and outreach.

“Out of my office, we’re going to be developing innovative ways of facilitating education and training opportunities focused on combating disease, all using a One Health–based approach,” Herbert said.

The outreach efforts will take both a local and a global lens to training. In one initiative, Herbert and colleagues Dr. Brittany Watson, director of Shelter Animal Medicine, and Dr. Molly Church, assistant professor of Pathobiology, are planning to provide scientific curriculum content for Pennsylvania high schools, such as videos that rely on the expertise of Penn faculty in infectious disease, to teach students about infection and the connection between human and animal health. Internationally, Herbert has already begun establishing connections in Africa and South America to share the work that Penn Vet faculty such as Dr. Jenni Punt, professor of Immunology and associate dean for One Health, and Dr. Amy Durham, assistant dean for education, have done to incorporate One Health concepts into its curriculum. In addition, a new mentorship program will pair mentors at Penn with students at veterinary schools in Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria, with the long-term goal of fostering relationships where Penn Vet can contribute to formalized training in the U.S.

“The mentees being suggested to me are the best and brightest, the most highly motivated,” Herbert said. “It’s not just an altruistic effort either — it’s self-serving in the sense that we get to learn from them and benefit from their expertise down the line.”

12 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

“WE RECOGNIZE THAT COVID HAS TAUGHT US A LOT OF THINGS. AND ONE OF THOSE IS THAT THESE LARGE, COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS ARE HOW WE CAN SOLVE LOTS OF OUR PROBLEMS AS A SOCIETY.”

DR. CHRISTOPHER HUNTER

Herbert’s future outreach plans include partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) to increase diversity in the veterinary profession and engagement with both undergraduate and high school students in the Philadelphia region to introduce them to the diverse work that veterinarians and veterinary scientists do to prevent and control disease.

“What local to global means to me is exposing a wide array of students to the opportunities that exist that they may not otherwise know about,” Herbert said.

RESULTS THAT MAKE A DIFFERENCE

As the Institute gets off the ground and gains momentum, new funding will provide seed grants for infectious disease researchers, support graduate education, and enable additional trainees into labs to work on zoonotic disease.

Critically, a foremost goal of the Institute is to provide services and research that aren’t stuck in the ivory tower but provide a service — to Pennsylvania, to farmers, to clinicians, to fellow scientists, and to the public at large.

“Our goal is to expand research of global and local infectious diseases,” Hunter said. “We want to make it as easy as possible for our faculty to work on these pathogens, and we want to provide tangible benefits to stakeholders.”

Already Hunter and Beiting are collaborating with the Perelman School of Medicine’s Dr. Drew Weissman, whose work on mRNA led to the platform for the Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, to apply a similar technology toward vaccines for porcine infections.

“We recognize that COVID has taught us a lot of things,” Hunter said. “And one of those is that these large, collaborative projects are how we can solve lots of our problems as a society.”

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 13

PANDEMIC PREPAREDNESS, THREE YEARS EARLY

By Michele W. Berger for Penn Today

By Michele W. Berger for Penn Today

14 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

When Penn Nursing’s Dean Antonia M. Villarruel and Deborah Becker, PhD, practice professor of nursing and director of the Adult Gerontology Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Program, gave a 2018 presentation at the University’s Perry World House with U.S. Ambassador Bonnie Jenkins, under secretary for arms control and international security, about the need for disaster preparedness, they had no idea just how prophetic that talk — and the subsequent simulations they put on — was.

From that initial talk came three simulation situations under the moniker PennDemic, created with Jenkins, Dr. Shelley Rankin, global director of microbiology and molecular diagnostics at Zoetis Reference Laboratories and formerly professor of Clinical Microbiology at Penn Vet; Dr. Stephen Cole, assistant professor of Clinical Microbiology, Penn Vet; Hillary Nelson, associate professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the Perelman School of Medicine; and Cathy Poon, associate dean of Interprofessional Education at the University of the Sciences.

Two iterations focused on infectious disease outbreaks, the third on a natural disaster. (A fourth, in October, focused on a plague.) Each exercise placed graduate students into interdisciplinary teams that included public health providers, basic scientists, veterinarians, pharmacists, physical therapists, nurses, physicians, and more to come up with solutions to the challenge at hand.

They published findings about their framework in Frontiers in Public Health

Penn Today recently spoke with Becker, Nelson, and Cole about PennDemic, as well as how the experience equipped participants for the coronavirus pandemic of today and for future disasters.

is

and

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 15

“We knew we wanted to engage more people in training for these events so that if they happened, we would be better prepared. We had no idea we were on the cusp of a worldwide pandemic.”

Deborah Becker, PhD

Drs. Stephen Cole

Shelley Rankin. Rankin

now with Zoetis Reference Laboratories.

Q: FOR EACH PENNDEMIC SIMULATION, AFTER YOU PRESENTED THE SCENARIO, WHAT HAPPENED NEXT?

Hillary Nelson: The very first activity is just in your discipline. That means you only talk about the information your discipline might receive. After that, you get into interdisciplinary groups, very purposefully, to come up with solutions. That is the crux of PennDemic: rather than throwing everyone together at the beginning, we start them out in their own disciplines.

Deborah Becker: This shows them what each group brings to the table, but it also helps the quieter students or those who were less experienced feel like they could contribute and ask a lot of questions. Why don’t we know this information? Where do these disciplines get this information that we don’t get? Why is that? It can be very eye-opening.

Q: DID ANYTHING IN PARTICULAR SURPRISE YOU?

Becker: Veterinarians do so much more than I knew. It’s not only about caring for pets, but also about the food chain, caring for livestock, and evaluating the safety of what we eat.

Nelson: For me, it was the pharmacists. We work with colleagues from the University of Sciences for the disciplines we don’t have at Penn, so there’s a nice synergy there. From that collaboration, we brought in pharmacy students. I had no idea how much pharmacists did beyond dispensing drugs.

Q: IN THE PAPER YOU PUBLISHED ABOUT PENNDEMIC, WHAT FINDINGS DID YOU DETAIL?

Nelson: The question we’d hoped to answer was, did this jigsaw framework that we developed have the pedagogical impact that we wanted? The answer

16 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

Dr. Laurel Redding summarizes her group’s thoughts during a brainstorming session during the first PennDemic outbreak simulation in 2018.

was yes. We saw statistically significant increases in both working in interprofessional teams and in disaster and emergency preparedness. That was really the big picture. If you drill down a little more, to the qualitative answers, students were asking about why certain disciplines were missing. These graduate students — who are normally very siloed — understood that to truly tackle disasters and emergencies, you need an interdisciplinary team.

Stephen Cole: Beyond that, we also showed that this is a field where we can help to grow the workforce. We need a diverse group of individuals to enter this workforce as these issues become more prevalent. This is a route our students can take regardless of their profession. There’s room for a wide variety of experiences to be involved in these sorts of responses.

Q: TO THAT END, HAVE YOU GOTTEN A SENSE FROM PREVIOUS PARTICIPANTS THAT THE SIMULATIONS HELPED THEM PREPARE FOR COVID-19?

Becker: I ran into two students, one who did the first simulation, one who did the second. They said to me, ‘Did you know a pandemic was going to happen?’ Of course, we had no crystal ball. They told me that what we reviewed in our simulations was what they were seeing happening in the hospital with COVID. They’re both nurse practitioners, and it seems that being able to refer back to this experience helped them. It was only two people out of a hundred and some who have done this, but

anecdotally we can say that they found value in it, particularly in terms of understanding what their roles might be during an actual pandemic.

Nelson: The third PennDemic simulation happened virtually [in fall 2020]. Those students definitely brought the experience of living through a pandemic into it. We haven’t yet done a follow up on the students who participated in the past few years, but that would be an interesting study to conduct.

Q: HOW DID THE EXPERIENCE PREPARE PARTICIPANTS FOR FUTURE PANDEMICS AND DISASTERS?

Cole: Regardless of the scenario, our framework is all about building our students’ confidence. We take them from a setting they’re comfortable in within their own discipline to an interdisciplinary scenario where they’re maybe not as comfortable, but we’ve spent the time making them sure that they know what they know. So, this process helps to build interest and confidence working in teams, as well as in disaster preparedness and response. To me, that’s the real take-home.

Becker: When it comes to disasters, we always think about health and safety. We’ve got to make sure that people aren’t drowning, that they have water and food — which absolutely is important — but what about other facets like infrastructure? What happened with the building near Miami is an example of this. It’s not just about health, and that was really eye-opening for the participants. I think that might fuel their interest in this field.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 17

We need a diverse group of individuals to enter this workforce as these issues become more prevalent.

BY SACHA ADORNO

Fighting on the Front Lines of Infectious Disease

Colonel Eric Lombardini, C’93, G’01, V’01 has lived or worked in 70 countries, on all continents except Antarctica, as a veterinary corps officer rising through the ranks of the U.S. Army.

Board certified in veterinary pathology and veterinary preventive medicine, Lombardini now is stationed in Bangkok, Thailand, where he serves as director of the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS), the Department of Defense’s largest medical research institute outside of the U.S.

FROM DIPLOMACY TO POPULATION HEALTH

It wasn’t the path Lombardini set on as an undergraduate at Penn studying diplomatic history, with a focus on Africa and the Middle East.

“I simply wasn’t attracted to economics, which was the future of diplomacy, so I turned instead to international development,” said Lombardini, who grew up in Niger and Bahrain as the son of a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) worker. “I decided to see if I could get

18 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

Colonel Eric Lombardini, C’93, G’01, V’01

into vet school as a way into development, specifically population health, looking at large animal production and how to improve nutrition for people in developing nations.”

The only catch was he had never taken any “serious science” courses in college. He eventually caught up on the necessary coursework and was accepted at Penn Vet. During vet school, he also earned a master’s degree in Clinical Epidemiology from Penn, focusing on transmission of the morbilliviruses from domestic stock to wildlife. Then, in 2001, things took a turn again. Lombardini joined the Army. “What the military offers is access to places far more challenging, far more difficult to get to than a lot of non-governmental organizations (NGOs),

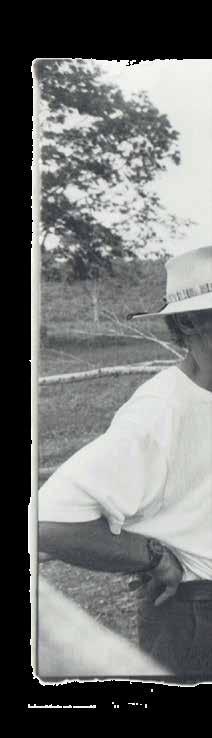

Dr. Eric Lombardini and Dr. Eric Davis in Northern Guatemala, Remote Area Medical, 2000.

Dr. Eric Lombardini and Dr. Eric Davis in Northern Guatemala, Remote Area Medical, 2000.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 19

Northern Guatemala

civilian agencies, or academia can offer,” said Lombardini. “The Army has enabled me to have deeper access and impact in times of crisis.” Crisis, like the unabating pandemic of the last nearly two years.

AT THE FRONT LINES OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

AFRIMS was formed in 1958 through an international treaty between Thailand and the U.S. Today, the bi-national institute conducts regional infectious disease surveillance and medical countermeasure research in five countries: Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines, Nepal, and Australia. It has robust partnerships in combating tropical and emerging infectious diseases with both military and civilian organizations in Vietnam, Mongolia, Bangladesh, India, Lao-PDR, Indonesia, and Bhutan. Headquartered in Bangkok — in the epicenter of more than 50 percent of the world’s population — AFRIMS comprises nine fixed satellite laboratories and hundreds of personnel spanning South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania — all under Lombardini’s direction.

“AFRIMS is an extraordinary place,” he explained. “Sixty years ago, Thailand invited the U.S. Army into the country to help control a cholera outbreak, one of a series that was plaguing the region. The relationship solidified into the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization Laboratory – the SEATO lab — which soon after became AFRIMS.”

Since its founding, AFRIMS has evolved its activities to include infectious disease research and epidemiology, its mission to protect the health and safety of American soldiers and civilians and Southeast Asian nationals across its service area.

The institute also has a storied legacy of success in medical countermeasures development — products, medications, and devices — to diagnose, prevent, or treat

diseases that are endemic or emerging in the region. It develops and tests vaccines (Pre-clinical and Phase 1 through Phase 3 clinical trials), rapid diagnostic tests, and treatments for endemic threats and emerging infectious diseases.

“We have played a significant role in disease prevention and countermeasures, such as developing every anti-malarial drug that is FDA approved and two Japanese encephalitis vaccines, dengue and the hepatitis E vaccines, and the world’s only partially effective HIV vaccine,” said Lombardini.

FIGHTING COVID-19 FROM DAY ONE

The first COVID-19 case outside of China occurred in Thailand, mobilizing AFRIMS in the pandemic’s earliest days in its role as a regional Research Center of Excellence and World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Center.

“We’ve been very active in COVID-19 surveillance, which is a huge issue — just recently, we were the first to identify the Delta variant in Thailand,” Lombardini said.

“And we feed information back to our allies and regional collaborators, as well as into the U.S. Indo-Pacific command. Our information becomes actionable for the various health ministries, U.S. and allied militaries, and interagency partners, such as the CDC and USAID, all of which depend on us for this surveillance data. And as a result, we’re able to protect people and track the spread of disease and how it works.”

Under Lombardini’s leadership, AFRIMS’s COVID-19 attack strategy is multifold. A key member of the U.S. ambassador to Thailand’s health working group and COVID-19 task force, Lombardini advises on U.S. strategic medical policy in Thailand and throughout Southeast Asia. Additionally, he is responsible for maintaining the scientific and ethical integrity of human, animal, and basic science research happening under AFRIMS’s auspices.

Bangkok, Thailand

Above, CPT Eric Lombardini examining a goat in Southern Iraq, OIF 2004. Left, CPT Eric Lombardini trimming a goat’s hooves in Southern Iraq, OIF 2004.

IraSouthern q

“The Army has enabled me to have deeper access and impact in times of crisis.”

–Dr. Eric Lombardini

CPT Eric Lombardini conducting an examination on a sick camel, Southern Iraq, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) 2004.

And for AFRIMS supporting its partner nations, sharing news, protocols, best practices, and tools to build each country’s capacity to fight COVID-19.

For example, during the earliest days of the outbreak, when testing kits were extremely limited, AFRIMS was one of the first laboratories in Southeast Asia to help screen suspected COVID-19 cases. It distributed hundreds of screening kits to partner laboratories.

AFRIMS has also provided subject matter expertise during the pandemic and is involved with pre-clinical development of therapeutics and COVID-19 vaccines in partnership with regional scientists. This includes helping with the pre-clinical development of ChulaCov19, a collaborative mRNA vaccine being developed in Thailand by Chulalongkorn University and the University of Pennsylvania.

“Over the course of my military career, I’ve seen Penn impact at many different levels.” Lombardini explained. “Penn Vet’s Working Dog Center, for example, has a strong relationship with the Department of Defense. The University developed the platform that the U.S. Army uses to develop resilience in its soldiers, and most recently and specific to AFRIMS, Penn Medicine’s Drew Weissman is working with Chulalongkorn University to help its researchers generate an mRNA vaccine for preventing COVID-19 in developing countries. AFRIMS participated in the vaccine research process. It’s a nice link for me to my alma mater.”

FROM BATTLEFIELD TO LAB BENCH

Lombardini’s current position is the pinnacle of an Army tenure that began in Fort Polk, Louisiana.

“I’d asked human resources for an operational unit and was thinking special forces — every special force group has a veterinarian attached to them,” he said. “They said, ‘Absolutely, we’ve got just the place for you — Fort Polk.’ Not quite what I had in mind.”

But it proved a formative assignment, and it’s where Lombardini learned to be a soldier and to lead. As an officer in charge at Fort Polk, he successfully trained a team of veterinary technicians and food inspectors in preparation for deployment.

In 2003, Lombardini was given a mission in Kuwait, entering Iraq immediately after the start of the invasion and becoming one of the first conventional veterinarians in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Stationed in An Nasiriyah in the earliest days of the war, he and his team provided veterinary and public health support to more than 75,000 coalition soldiers, airmen, and marines, as well as food inspection services for the local Iraqi population.

Following his Iraqi tour, Lombardini was sent to the Aviano Air Base veterinary services in Northern Italy. The only U.S. Army member assigned to the Air Force base, he was officer in charge of zoonotic disease prevention, public health measures, and clinical care for the companion animals of thousands of active and retired service members and their families, as well as three populations of military working dogs. On top of this, he conducted vendor food and water inspections across Northern Italy, Hungary, Romania, the Balkans, and

22 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

MAJ Eric Lombardini, Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute, Bethesda, Maryland 2010.

At the same time, Lombardini supported NATO forces in Kosovo and Bosnia, giving medical support to military working dogs.

After Italy and before landing in his leadership role at AFRIMS, Lombardini would go on to work in different areas of the DOD’s complex and vast medical research and public health infrastructure. He completed a veterinary pathology residency at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and led field research projects in multiple countries. As a lieutenant colonel, he was selected to command the battalion responsible for the U.S. Army public health mission across much of the western half of the U.S. He attended the U.S. Army War College and conducted field research in the Arctic Circle and elsewhere, earned a PhD in Microbiology from the Open University through collaborative malaria work with Oxford University, and published in more than 80 peer-reviewed journals.

“I’ve had a fascinating career, some of it in very heated places,” he reflected. “A number of missions were a blend of animal care, human food safety, and infectious disease monitoring, like Operation Iraqi Freedom, which involved leishmania surveillance,

military working dog care, and food inspection. It’s been wonderful and at times very sobering.”

ENGAGEMENTS OF THE NONMILITARY KIND

Lombardini’s career narrative is about to become even longer when he retires from the military this fall and returns stateside to work in industry, taking a leadership role in pre-clinical development.

For all his accomplishments, the busy colonel finds time for less globally urgent but personally essential activities with his wife and 11-year-old son. “We love to travel and enjoy good food and wine — my wife is Italian, so of course, we drink a lot of Italian wine,” laughed Lombardini. He’s also a wildlife photographer and an amateur paleontologist, the latter, he said, much to his wife’s chagrin. Not bad, for a would-be diplomat, who confesses to having never been a great science student. “I certainly will not go down in history as a stellar student, but I was enthusiastic and my mentors recognized something in me and took a chance,” he said. The gamble, for sure, paid off.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 23

COL Eric Lombardini at a Merit Making ceremony for the 58th Anniversary of AFRIMS.

Bangkok,

“Over the course of my military career, I’ve seen Penn impact at many different levels.”

–Dr. Eric Lombardini

Supporting a Pipeline of Infectious Disease Experts

By Sacha Adorno

Martin Winter, G’76, W’76, believes Penn is positioned to lead “just about every intersection of research and practice there is.” Right now, the intersections that intrigue him most are in science, particularly the translation of laboratory findings into efficacious treatments for humans and animals.

24 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22 MARTIN WINTER Philanthropy

As a philanthropist and vice chair of Penn Vet’s Board of Advisors, Winter has long followed and supported the cancer research of Dr. Nicola Mason, The Paul A. James and Charles A. Gilmore Endowed Chair Professorship within the Department of Clinical Sciences and Advanced Medicine, and Ellen Puré, PhD, Director, Penn Vet Cancer Center, both of whom collaborate closely with Penn Medicine.

Earlier this fall, intrigued by the work happening at Penn Vet and Penn Medicine in infectious disease, he and his wife established The Martin E. Winter and Pamela Winter Infectious Disease Fellowship Fund to support the School’s new Institute for Infectious and Zoonotic Diseases (IIZD) (see page 6).

PHILANTHROPY FOR TOMORROW’S EXPERTS

“Penn leads in animal and human cancer research, and I don’t see any reason why Penn shouldn’t also take the lead in infectious disease investigation,” said Winter, who has served on the School’s Board of Advisors since 2012.

Among IIZD’s goals are building the field of veterinary specialists with leading-edge microbiology and infectious disease skills; expanding the size and readiness of a veterinary workforce that is poised to detect infectious disease; and preparing and grooming veterinary professionals to respond to future zoonotic outbreaks.

Designed to bring talented people to IIZD, the Martins’ eponymous fund provides financial support to rising experts focusing on infectious disease research under the direction of IIZD faculty. It will help the institute attract and retain veterinary, master’s, and PhD students, as well as residents — particularly from underrepresented communities — who are motivated to participate in this new well-resourced, multidisciplinary program.

Winter co-heads the Healthcare Industry Group at the global consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal and has seen many enterprises drive change and make an impact. He is excited to see IIZD take off: “Penn Vet has the faculty; we have the research capability; we have the intersection with human medicine

that positions Chris Hunter (IIZD’s director) and IIZD faculty members to really step on the gas and develop tools that rapidly address vaccination issues, for example.”

URGENT AGENDA

The world is primed for this, added Winter, “COVID-19 showed us the multidimensional reach of veterinarians and veterinary science. Veterinarians are in positions they may not have pursued 40 years ago. Take Pfizer CEO Dr. Albert Bourla, a DVM, PhD. He’s leading a major pharmaceutical company that’s been central to COVID-19 prevention. These are the areas veterinarians need to be and increasingly are.”

Martin said the opportunity to train young researchers in these areas is what sets Penn Vet apart and inspired him and Pam to give.

“The close connection among Penn Vet and Penn Medicine — the fluidity of ideas between the two — has extraordinary implications,” he said. “These are incredibly focused folks who have learned so much and do a great job applying their knowledge. And, at the end of the day, training new people is key to their work. It helps us from a wildlife perspective; it helps us from a food animal perspective; and it helps us from a companion animal perspective. As a lay person who understands the science only so much, I am proud to be part of this bold new and never more urgent initiative.”

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 25

“Penn leads in animal and human cancer research, and I don’t see any reason why Penn shouldn’t also take the lead in infectious disease investigation.”

Martin Winter

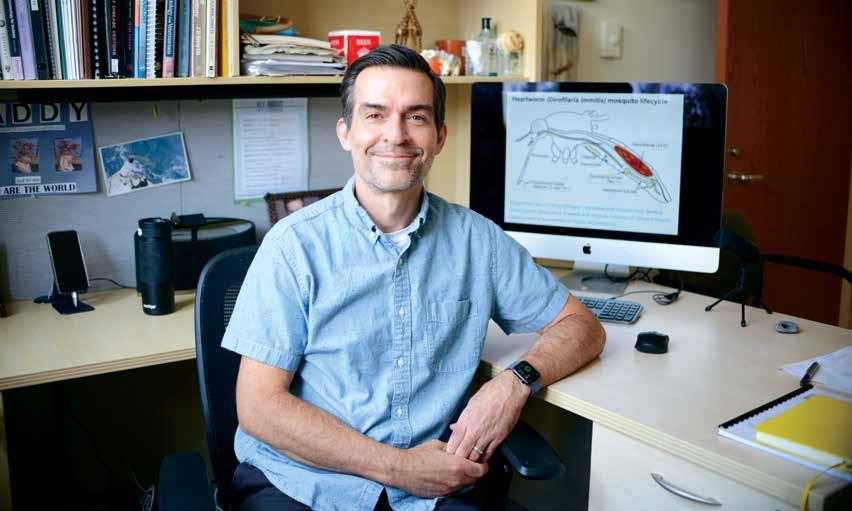

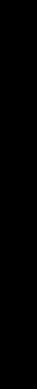

IN THE OFFICE WITH Dr. Michael Povelones

Head of the PoveLab

By Sacha Adorno

Causing roughly 409,000 deaths a year according to the Gates Foundation, mosquitoes are deadlier than sharks, lions, crocodiles, scorpions, tigers, or, even, humans. As a vector for diseases like malaria, which kills nearly one child every minute, the insects are more than backyard nuisances, especially in developing countries. Understanding and subverting the insect’s role as a host for animal and human disease is the life’s work of Dr. Michael Povelones, assistant professor of Pathobiology. (See page 28 for more about his research.) Povelones’s lab on Penn Vet’s Philadelphia campus studies “the most species-rich group of animals on the planet,” and his office is also filled with mosquitoes, of the art and object kind.

26 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

What’s the world’s deadliest animal?

A hint — it’s usually smaller than an inch and notorious for itchy bite marks.

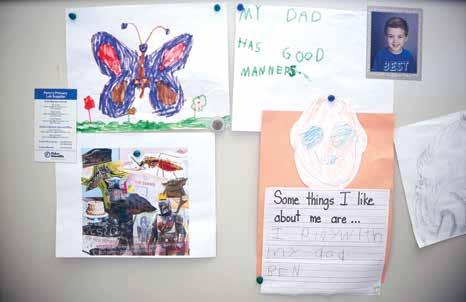

1. “Good manners.” I have mountains of artwork from my son Benjamin. These are a few pieces and school writing assignments — I appreciate the reminder that I have good manners [laughing]; it’s always nice to hear. He is seven, and his brother William is three.

2. Mosquito…or is it? I found this metal sculpture at the Chelsea Flower Show in London – it’s another reminder of my time in the UK. I noticed it from afar and knew I had to have it. I learned after buying it that it’s meant to be a bumblebee, which I can sort of see, but to me it resembles a mosquito more than a bee. That’s how I first saw it, and no one has questioned it since.

3. Bottle stopper and bottle. The American Heartworm Society gave the mosquito bottle stopper as an appreciation gift for participation in its triennial symposium. The meeting is the premier place to present heartworm research in the U.S. The stopper is atop an empty bottle of bourbon from Brandywine Distillery — it’s known for gin but also does bourbon, which I prefer. My colleague Amy Durham told me about the distillery’s pandemic delivery program when Pennsylvania liquor stores were closed, and the bottle is a little reminder of the shutdown.

4. Mosquitoes on canvas. My first lab technician, Letitia Thompson, painted this piece for me as a parting gift — I’m proud she just completed her PhD at New York University. Those are the two types of mosquitoes my lab works with: the brown are Anopheles gambiae, the African malaria carrying mosquito; the black are Aedes aegypti that we use for heartworm — it’s a cousin of the tiger mosquito, the kind that are abundant in Philly.

5. Mosquito on camera. The amazing photographer and entomologist Alex Wild shot this. He photographs all manner of insects. I purchased the image for my office — and it has also appeared on the cover of Science magazine.

6. London in Philly. I became a fan of English football — or soccer — as a postdoc at Imperial College in West London, which is near the grounds of Chelsea Football Club. A friend was a season ticket holder, and I went to a lot of top-level games. I loved participating in that aspect of British culture, and I still watch televised games whenever possible.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 27

1.

3.

2.

IN THE OFFICE

4.

6.

5.

STOPPING DISEASE TRANSMISSION AT THE SOURCE

By Katherine Unger Baillie

Some of the world’s most concerning infectious diseases, from malaria and Chagas disease to heartworm and leishmaniasis, are transmitted by mosquitoes and other insect vectors. While an ample body of research has worked to develop treatments and preventive strategies that focus on what happens once a pathogen has entered the body of a human or animal, Penn Vet’s Michael Povelones, PhD, assistant professor of Pathobiology, takes a different approach, jumping back a step to consider how the chain of disease transmission could be halted before a pathogen ever leaves the insect vector.

In recent work, Povelones and colleagues have made advancements toward this goal, working in several different infection models. A paper out last year in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported the successful outcome of the lab’s effort to ramp up the immune response of mosquitoes in order to prevent them from transmitting the related parasitic worms Dirofilaria immitis , which causes the debilitating canine heartworm disease, and Brugia malayi , responsible for lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis.

Studying a strain of Aedes aegypti mosquito that is resistant to infection with the heartworm parasite, the team — including co-first authors Elizabeth Edgerton, now a VMD student in the class of 2022, and research technician Abigail McCrea — discovered that this quality correlates with a hypercharged immune response. By activating this immune system defense in otherwise-susceptible mosquitoes, they were able to stop parasites — both D. immitis and B. malayi — from developing into a transmissible form in the insects. Such a blockade could stop filarial parasites from passing to dogs or humans.

28 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22

RESEARCH

THE NEW MODEL, WHICH CAN BE APPLIED QUICKLY AND SIMPLY USING JUST A FEW MOSQUITOES, HAS ALREADY BEEN TAKEN UP BY OTHER MOSQUITO RESEARCHERS.

“Heartworm is everywhere; in some places if you don’t give dogs a preventive drug they’re almost definitely going to get heartworm,” Povelones says. “On top of that there is emerging drug-resistant heartworm parasites in certain areas. All of that makes the mosquito seem like an attractive target to make inroads into these problems and prevent disease transmission.” The lab has recently had a grant recommended for funding by the Morris Animal Foundation to explore this concept further.

Although the parasite that causes lymphatic filariasis behaves slightly differently within the mosquito than the heartworm parasite, Povelones was encouraged that the same immune system activation strategy significantly lowered mosquitoes’ ability to pass along either parasite.

“People are starting to look at these solutions that focus on the mosquito in diseases like malaria and dengue,” he said. “I don’t think it’s disingenuous to say that these kinds of approaches could be used, perhaps in a locally targeted way, to stop heartworm or lymphatic filariasis.”

In a parallel vein of work, Povelones has teamed up with his wife, Megan Povelones, PhD, a faculty member at Villanova University, to investigate another group of disease-causing microorganisms called kinetoplastids. These single-celled microbes are responsible for serious infections such as Chagas disease, African sleeping sickness, and leishmaniasis. The collaboration led to a new model for studying how these parasites latch on to mosquitoes’ insides, a necessary step in propagating infection to other organisms. They described the model, which uses the non-disease-causing kinetoplastid species Crithidia fasciculata , in a 2019 paper in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases .

“The parasite has to hold on so it won’t pass right through,” said Povelones. “It needs to get retained in the gut in order to multiply and eventually get transmitted. These mechanisms of adherence seem to be [shared] across kinetoplastid species, so the

hope is that our insights about Crithidia will tell us something about adherence in the medically relevant species.”

The couple recently received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to continue enlisting the model system to understand what prompts the shift from a “swimming” form to an adherent form. If a chemical or genetic manipulation could prevent the parasite from adhering, then perhaps the parasites would pass through the vectors, unable to be transmitted to a human or other animal.

And in yet another innovative model system developed by the lab, Penn Vet VMD-PhD student Greg Sousa led the lab’s efforts, with the readout coming from an unlikely source: mosquito poop.

“Greg found out in the course of doing standard assays that if we inject mosquitoes with bacteria, they start to secrete a pigment in their waste,” Povelones said of the study, shared in the journal PLOS Pathogens . “Basically, their poop is extra brown. And so now we can go in and challenge them with an infection or knock down a gene of interest and learn something about what is happening with their immune defenses by these spots they leave.”

The new model, which can be applied quickly and simply using just a few mosquitoes, has already been taken up by other mosquito researchers. For the Povelones lab, it has enabled them to begin identifying components of the immune system that mosquitoes use to mount a response against the malaria parasite, among other infections.

As the new Institute for Infectious and Zoonotic Diseases gains momentum, Povelones is eager to continue contributing to the University’s coordinated efforts to illuminate and solve challenges when it comes to animal and human health. “Many of these neglected diseases we study — whether it’s trypanosomes, malaria, or leishmaniasis — affect dogs and other animals as well,” Povelones said. “There are zoonotic threads throughout this work.”

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 29

RESEARCH

CLIMATE WEEK

THE VETERINARY PERSPECTIVE ON CLIMATE CHANGE THREATS AND SOLUTIONS

In September, Penn students, faculty, staff, and guests spent a week looking at climate change from all angles during the University’s second annual Climate Week at Penn. At the nexus of humans, animals, and the environment, Penn Vet had a lot to say.

Penn Vet faculty discussed the zoonotic consequences of extreme heat in the panel The Wet and Sweltering Spillover: Happy Mosquitoes, Miserable Humans, Dangerous Disease

Presented by the School’s Bellwether Sessions virtual event series and hosted by De’Broski Herbert, PhD, presidential associate professor and associate professor of Pathobiology, the webinar featured Julie Ellis, PhD, co-director, Wildlife Futures Program; Lisa Murphy, VMD, resident director of the Pennsylvania Animal Diagnostic Laboratory at New Bolton Center; and Michael Povelones, PhD, assistant professor of Pathobiology.

The group shared insights on the impact of rising heat and precipitation on disease transmission; mosquitoes, insects, and animal hosts for disease; and the very real risk of major spillover events that could compromise the health of wildlife, livestock, and humans. The same week, which coincided with the 2021 Penn Annual Conference, Penn Vet alumna

Dr. Angela Frimberger, V’90 , presented a PAC keynote entitled Climate Change — A Veterinary

Problem . Her keynote explored the realities of climate change, its impact on animals, and veterinary-focused solutions.

A veterinary oncologist who lives and practices in Australia, Frimberger has immersed herself in the science, policy, education, and organization around climate change. She is a founder and board chair of Veterinarians for Climate Action, a global network of animal health professionals concerned about climate change.

To learn more about Veterinarians for Climate Action, their vision, their approach, and their work, go to vfca.org.au.

30 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22 SCHOOL NEWS

FACULTY & STAFF UPDATES

Matthew Atherton, BVSc, PhD , began his new role as Lecturer in Clinical Immunology-Oncology. In addition, he published Lenz J, Assenmacher C-A, Costa V, Louka K, Rau S, Keuler N, Zhang PJ, Maki RG, Durham AC, Radaelli E, and Atherton MJ, “Increased TumorInfiltrating Lymphocyte Density Is Associated with Favorable Outcomes in a Comparative Study of Canine Histiocytic Sarcoma,” Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy , https://doi. org/10.1007/s00262-021-03033-z. The paper was also featured in the Veterinary Cancer Society’s newsletter on August 24, 2021.

William Beltran, DVM, PhD , published Mbefo M, Berger A, Schouwey K, Gérard X, Kostic C, Beryozkin A, Sharon D, Dolfuss H, Munier F, Tran HV, van Lohuizen M, Beltran WA, and Arsenijevic Y, “Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) Contributes to Rod

Photoreceptor Death Process in Several Forms of Retinal Degeneration and Its Activity Can Serve as a Biomarker for Therapy

Efficacy,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences , 2021, https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179331. He also published Aguirre GD, Cideciyan AV, Dufour VL, Ripolles-García A, Sudharsan R, Swider M, Nikonov R, Iwabe S, Boye SL, Hauswirth WW, Jacobson SG, and Beltran WA, “Gene Therapy Reforms

Photoreceptor Structure and

Gary Althouse, DVM, PhD, MS, Diplomate ACT , was recognized as the 2021 Theriogenologist of the Year at the American College of Theriogenologists general conference in Omaha in July. He is the founder and director of Penn Vet’s Reference Andrology Laboratory, which provides critical research and clinical services in food animal production in the US and abroad. In addition, the 2021 World Health Organization laboratory manual has incorporated several publications from the Althouse laboratory in its new recommendations for the examination and processing of human semen.

Restores Vision in NPHP5Associated Leber Congenital Amaurosis,” Molecular Therapy , 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ymthe.2021.03.021.

Leonardo Brito, DVM, PhD, DACT was elected vice president of the American College of Theriogenologists. He was also a member of the committee that selected the recipient of the Research Award from the National Association of Animal Breeders; the award will be presented to the winner during the association conference in October.

Kara Brown, VMD, DACVSMR , successfully passed the board certification exam for the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation. Having completed her residency and examination, she is now a Diplomate of the College.

Jen-Yun Chou, MSc, PhD , received the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare’s 2021 Early Career Animal Welfare Researcher of the Year Award. The award recognizes innovative research activities aimed at advancing animal welfare and improving the understanding of animal welfare challenges.

Bruce Freedman, VMD, PhD , was appointed chair of the Gene Therapy and Vaccines (GTV) graduate group.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 31 FACULTY NEWS

FACULTY & STAFF UPDATES

De’Broski Herbert, PhD , University of Pennsylvania President Amy Gutmann appointed Herbert to Presidential Associate Professor. Presidential Professorships are awarded by the University president to exceptional scholars, at any rank, who contribute to faculty eminence through scholarship and diversity across the University.

Linda Baker, VMD, MS , received the Distinguished Veterinary Service Award by the Pennsylvania Veterinary Medical Association for her contributions to the Pennsylvania dairy industry, specifically recognizing her commitment to both the science and the skills necessary to steward healthy, productive, and profitable herds of cattle.

Angela Gaesser, DVM, DACVS , successfully passed the board certification exam for the American College of Veterinary Surgeons. Having completed her residency and examinations, she is now a Diplomate of the College.

Fuyu Guan, PhD , published Guan F, You Y, Fay S, Li Xi, and Robinson MA, “Novel Algorithms for Comprehensive Untargeted Detection of Doping Agents in Biological Samples,” Analytical Chemistry, 2021, https://doi. org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01273.

Rebecka Hess, DVM, MSCE , published Shea EK and Hess RS, “Assessment of Postprandial Hyperglycemia and Circadian Fluctuation of Glucose Concentrations in Diabetic Dogs Using a Flash Glucose Monitoring System,” Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine , 2021, https:// doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16046. She also published Shea EK and Hess RS, “Validation of a Flash Glucose Monitoring System in Outpatient Diabetic System,” Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine , 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/ jvim.16216. In addition, she gave a virtual talk on Addison’s disease at Curso Internacional De Endocrinologia Veterinaria, Sedivet, Santiago, Chile on August 13, 2021.

Andrew Hoffman, DVM, DVSc, DACVIM , received the George B. Wolff Legislative Leadership Award from the Pennsylvania Veterinary Medical Association for his dedicated legislative advocacy on behalf of the veterinary profession at the state and federal levels.

Tonya Bennett, MLA , was elected to the Penn Professional Staff Assembly (PPSA), which provides a forum for staff to engage in dialogue about issues facing the University and higher education. She is also one of two recipients of the EDUCAUSE 2021 Rising Star Award, which recognizes early-career IT professionals who demonstrate exceptional leadership and accomplishments in information technology in higher education.

Heather Hunchuck , imaging and sports medicine technician at New Bolton Center, was awarded PVMA’s Veterinary Assistant of the Year Award. She was honored for her outstanding service, skills, character, and dedication, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic as she stepped into a critical role to address the demands of the hospital.

32 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22 FACULTY NEWS

CONTINUED

Chris Lengner, PhD , published Simeonov KP, Byrns CN, Clark ML, Norgard RJ, Martin B, Stanger BZ, Shendure J, McKenna A, and Lengner CJ, “Single-Cell Lineage Tracing of Metastatic Cancer Reveals Selection of Hybrid EMT States, Cancer Cell , 2021, https:// www.doi.org/10.1016/j. ccell.2021.05.005. He also published Kolev HM, Tian Y, Kim MS, Leu NA, Adams-Tzivelekidis S, Lengner CJ, Li N, and Kaestner KH, “A FoxL1-CreERT-2A-tdTomato Mouse Labels Subepithelial Telocytes, Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology , 2021, https://www. doi.org/10.1016/j. jcmgh.2021.05.009.

Timothy J. Manzi, VMD, ACVR, ACVR-EDI , passed his examination to become boardcertified in Equine Diagnostic Imaging, the ACVR-EDI subspecialty.

Jennifer Reetz, DVM, DACVIM (LA), DACVR , won the 2021 Faculty Teaching Award, awarded by Penn Vet residents.

Emily Rule, VMD, DABVP , passed the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners certifying examination to become a Diplomate of the ABVP, certified in Equine Practice.

Jennifer Reetz, DVM, DACVIM (LA), DACVR , won the 2021 Faculty Teaching Award, awarded by Penn Vet residents.

Dieter Schifferli, PhD , DrMedVet, published Dehinwal R, Cooley D, Rakov AV, Alugupalli AS, Harmon J, Cunrath O, Vallabhajosyula P, Bumann D, and Schifferli DM, “Increased Production of Outer Membrane Vesicles by Salmonella Interferes with ComplementMediated Innate Immune Attack,” mBio , 2021, https://www.doi. org/10.1128/mBio.00869-21.

Deborah Silverstein, DVM, DACVECC , spoke at the Argentina Vet School Conference in July 2021. In addition, she published Chalifoux NV, Hess RS, and Silverstein DC, “Effectiveness of Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation in Hypotensive Cats: 82 Cases (2012–2019),” Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care , 2021, https://doi. org/10.1111/vec.13072. She also published Buriko Y, Hess RS, Pfeifer JM, and Silverstein DC, “Utility of the Sonoclot Analyzer to Assess Hyperfibrinolysis in Dogs,” Veterinary Clinical Pathology , 2021, https://doi. org/10.1111/vcp.12953. And she published Chalifoux NV, Spielvogel CF, Stefanovski D, and Silverstein DC, “Standardized Capillary Refill Time and Relation to Clinical Parameters in Hospitalized Dogs,” Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care , 2021, https://doi. org/10.1111/vec.13088.

Boris Striepen, PhD , professor of Pathobiology, has been named the Mark Whittier and Lila

Griswold Allam Professor of Microbiology and Immunology. The Professorship was established in 1980 by Elizabeth R. Moran in honor of Dr. Mark Allam.

Vince Thawley, VMD, DACVECC , received the Zoetis Distinguished Teacher Award and the Class of 2022 Philadelphia Campus Teaching Award at the SAVMA award ceremony in May.

Charles Vite, DVM, ACVIM (Neurology) , joined the Canine Committee of The Seeing Eye, located in Morristown, New Jersey. He spoke about developing therapies for pediatric neurodegenerative disorders at the Korat School of Veterinary Medicine Departmental Seminar; about gene therapy for Niemann Pick type C disease at the Gene Therapy Symposium for Veterinary Summer Research Students organized by Michigan State University Veterinary Medical Center; and about canine and feline models of neurological disease at the 13th Comparative Medicine Resource Directors

Meeting, Office of Research Infrastructure Program, NIH. And he served as special government Employee and consultant for the FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapy Advisory Committee in September 2021.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 33

GRANTS

Gustavo Aguirre, VMD, PhD , received an 18-month, $74,160 grant from the Poodle Club of North America Foundation for Genetic Test Development for Inherited Eye Disease in Poodles. The grant spams from July 1, 2021 to December 31, 2022. He also received a $87,173 grant from the American Spaniel Club Health & Rescue Foundation for Molecular Genetic Studies of Inherited Cataracts in the American Cocker Spaniel. The grant spans from January 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022.

Jorge Alvarez, PhD , received a $205,152 grant from EMD Serono for Defining the Role of BTK in Meningeal Inflammation — From Meningeal B Cells to Tertiary Follicle-Like Structures. The grant spans from February 4, 2019 to July 31, 2022.

Eman Anis, PhD , received a $8,063 grant from the Pennsylvania Center for Poultry and Livestock Excellence for Surveillance for Egg Drop Syndrome (EDS) Infection Using a Commercial ELISA Kit. The grant spans from May 24, 2021 to May 24, 2022.

Michael Atchison, PhD , received a $2,544,568 NIH NIAID grant to compare the molecular genetic phenotype (gene expression patterns, chromatin accessibility, epigenetic structure, and chromatin folding) of YY1-null pro-B cells developed into DN1, DN2a, DN2b, DN3, DP, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells, compared to wild-type T lineage cells, as well as YY1 conditional knockout T lineage cells (Aim 2). The grant spans from June 2021 to May 2026. His collaborators are Ivan Maillard, Jennifer Phillips-Cremins, and Golnaz Vahedi. He also received a $2,489,662 NIH NIAID grant to determine chromatin folding patterns, nuclear localization of key genes, chromatin accessibility, and epigenetic structures in wild-type and YY1-null pro-B cells to define the genomic structures regulated by YY1 during B lineage commitment. The grant spans from July 15, 2021 to June 30, 2026. His collaborators are Jennifer Phillips-Cremins, Cornelis Murre, and Ranjan Sen. In addition, he received a $1,240,972 NIH/R01 grant for Mechanisms of Lineage Plasticity Revealed by YY1 Deficiency. The grant spans from June 1, 2021 to May 31, 2026. He also received a $1,532,099 NIH/ R01 grant for YY1-Dependent Chromatin Structure Stabilization of B Lineage Commitment. The grant spans from July 15, 2021 to June 30, 2026. And he received a

$20,000 NIH/Boehringer Ingelheim grant for the NIH-BI summer scholars program at Penn Vet. The grant spans from April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022.

Matthew Atherton, BVSc, PhD , received a $711,345 NIH NCI K08 grant for Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications of IFNAR1 Signaling on CAR T-Cell Therapy for Cancer. The grant spans from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2026.

Swarna Bais, PhD , received a $275,000 NIH R21 grant for Oncolytic Virus Targeting Schistosomes. The grant spans from March 16, 2021 to February 28, 2023. Her collaborator is Robert Greenberg, PhD.

William Beltran, DVM, PhD , received a one-year, $500,000 grant from the Foundation Fighting Blindness for PENN Large Animal Model Translational & Research Center. The grant spans July 1, 2021 – June 30, 2022.

Joseph Bender, DVM , received a $10,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture for Evaluation of Reproductive Efficiency on Pennsylvania Dairy Farms. The grant spans from January 1, 2021 to June 30, 2021.

34 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22 FACULTY NEWS

Ashley Boyle, DVM , received a $15,000 grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica for Guttural Pouch Microbiome in Health and Disease. The grant spans from January 1, 2021 to December 31, 2021.

Raimon Duran-Struuck, DVM, PhD , received a $150,000 grant from ITMAT-TAPIMAT for CAR Treg Technology for Immune Tolerance to Skin Allografts — A Pre-clinical Model of Skin Grafting and Vascular Tissue Allotransplantation. The grant spans from March 1, 2021 to February 28, 2023.

Anna Gelzer, DrMedVet, PhD , received a $14,933 grant from the ACVIM Foundation for Characterization of Buccal Mucosal Cells from Boxers with ARVC. The grant spans from January 1, 2021 to January 1, 2023.

Ronald Harty, PhD , received a $275,000 NIH R21 grant for Role of Host Angiomotin as a Central Regulator of Filovirus Egress and Dissemination. The grant spans from March 31, 2021 to February 28, 2023. He also received a $553,990 grant from Fox Chase Chemical Diversity Center for Development of Host-Oriented Small Molecule Therapeutics for Filoviruses and Arenaviruses. The grant spans from April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2024.

De’Broski Herbert, PhD , received a $343,891 NIH U01 supplement award for Trefoil Factor Proteins Regulate Inflammation and Immunity Importance of Trefoil Factor 3-LINTO2 Interactions

During Infection of Human Nasal Epithelial Cells with SARS-Cov-2. The grant spans from November 25, 2020 to July 31, 2021. He also received a $1,160,564 NIH T32 grant for Parasitology: Modern Approaches. The grant spans from September 1, 2021 to August 31, 2023. In addition, he received a $1,000,000 NIH R01 grant for Myeloid Derived IL-33 Controls Treg Responses During Parasite Infection. The grant spans from August 6, 2021 to July 31, 2025.

Katrin Hinrichs, DVM, PhD , received a $68,590.67 grant from the American Quarter Horse Foundation for Effect of Day Estrus Cycle at TVA on Rates of in vitro Oocyte Maturation and Blastocyst Production after ICSI. The grant spans from October 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022. She also received a $68,371 PENVFY2021 capacity grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture/Department of Agriculture for. The grant spans from October 1, 2020 to September 30, 2022.

Christopher Hunter, PhD , received a $799,998 NIH U01 (sub to University of Colorado) grant for Mechanisms of Combined CD40/TLR Adjuvant-Elicited Cellular Immunity. The grant spans from March 25, 2021 to February 28, 2026. He also received a $1,690,655 NIH U01 grant for The Role of CD40L in Resistance to Enteric Infection. The grant spans from August 17, 2021 to May 31, 2026. His collaborator is Boris Striepen, PhD.

Anna Kashina, PhD , received a $510,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture for Fecal Microbiome Signatures as a Diagnostic Marker in Chronic Wasting Disease. The grant spans from May 14, 2021 to February 28, 2023.

Hania Kébir, PhD , received a $123,000 grant from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada for Immunotherapy to Target Meningeal B Cells in a Model of Progressive-like Multiple Sclerosis. The grant spans from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2024. She is affiliated with the Alvarez laboratory.

WWW.VET.UPENN.EDU/BELLWETHER 35

GRANTS CONTINUED

Michaela Kristula, DVM , received a $9,348 grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture for Novel Implementation of FARM on a Pennsylvania Dairy Farm Pilot Project. The grant spanned from January 1, 2021 to June 30, 2021.

Chris Lengner, PhD , received a $55,000 grant from the Abramson Center Pilot Breakthrough Bike Challenge for Development of Perturb-macsGESTALT to Interrogate Colon Cancer Regulation and Clonal Evolution. The grant spans from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022. His collaborator is Andres Blanco. He also received a $1,115,688 NIH/R01 grant for The Basis for and Function of Enteroendocrine Lineage Plasticity in the Intestinal DNA Damage Response. The grant spans from May 5, 2021 to April 30, 2024.

Claudia Lovell, MD-PhD candidate , received a $30,000 Future Physician Scientist Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation. The grant spans from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2023. She is affiliated with the Anguera laboratory.

Nicola Mason, BVetMed, PhD , received a $1,890,627 NIH U24 grant for New Supplement: Coordinating Center for Canine Immunotherapy Trials and Correlative Studies. The grant spanned from September 1, 2020 to August 31, 2021.

Leonardo Murgiano, PhD , received a $46,504 grant from the Collie Health Foundation for Molecular Mapping and Characterization of the Genetic Modifier Associated with Collie Eye Anomaly. The grant spans from September 1, 2021 to February 28, 2022.

Cynthia Otto, DVM, PhD , received a $220,224 grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture for A Proof of Concept: Are Detection Dogs a Useful Tool to Screen WhiteTailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Feces for Chronic Wasting Disease? The grant spans from March 1, 2021 to February 28, 2023.

Mark Oyama, MSCE , received a $11,813 grant from Nestle Purina Petcare for Targeted Metabolomics in Dogs with Mitral Valve Disease. The grant spans from February 1, 2021 to January 31, 2022.

Ellen Puré, PhD , received a $50,000 grant from the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics Pilot Grant Translational Biomedical Imaging Center for Companion Diagnostic and Therapeutic Biomarker Imaging Tools for Understanding CAR T-Cell Efficacy. The grant spans from March 1, 2021 to February 28, 2022.

Gatha Thacker, PhD , received a $75,000 BRCA Early Career Award for Regulation of IFN- γ Signaling in BRCA1-loss Dependent Breast Cancer. The grant spans from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022. He is affiliated with the Chakrabarti laboratory.

Andrew van Eps, BVSc, PhD , received a $148,185 grant from the Grayson Jockey Club Research Foundation for Understanding and Preventing Supporting Limb Laminitis. The grant spans from April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2023.

36 BELLWETHER FALL/WINTER 2021-22 FACULTY NEWS

Charles Vite, DVM, ACVIM (Neurology) , received a two-year, $298,018 direct costs grant from StrideBio for Intracisternal Administration of Novel Viral Vectors to Restore Expression and Treat Cerebellar Ataxia in Feline NPC1. He also received a $298,018 grant from StrideBio for Biodistribution Study in Normal Cats and Intracisternal Administration of Novel AAV-fNPC1 to Restore Expression and Treat Cerebellar Ataxia in Feline NPC1. The grant spans from February 11, 2021 to December 31, 2022.

Susan Volk, VMD, PhD , received a $182,845 grant from the AKC Canine Health Foundation for Tumor-Permissive Collagen Signatures in Canine Mammary Gland Tumors: Development of Prognostic Markers and Targeted Therapies for Improved Outcomes. The grant spans from March 1, 2021 to February 28, 2023.

John Wolfe, VMD, PhD , received a $27,796 Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award from the CTSA/Program in Comparative Animal Biology. The grant spans from June 1, 2021 to May 31, 2022.

Penn Vet’s Memorial Program for Animals

Is there a special animal, large or small, that you would like to remember? Are you a veterinary practice that wishes to honor the memory of your patients?

When you participate in our Pet Memorial Program, you support Penn Vet’s commitment to animal health by accelerating the discovery and clinical development of innovative therapies and diagnostics.

MORE INFORMATION

If you would like more information about this very special program, please visit www.vet.upenn.edu/animal-memorial-giving or contact Liz Velez at lvelez@vet.upenn.edu, or call 215-898-1480.

FACULTY RETIREMENTS

Gustavo Aguirre, VMD, PhD , professor of Medical Genetics and Ophthalmology, Department of Clinical Sciences and Advanced Medicine.

Narayan G. Avadhani, PhD , professor of Biochemistry and the Harriet Ellison Woodward Professor of Biochemistry, Department of Biomedical Sciences.

Peter Dodson, MSc, PhD , professor of Anatomy, Department of Biomedical Sciences, and professor of Paleontology, Department of Earth and Environmental Science.