Letter from the Chair

When most people imagine what planners do, they think about street design and zoning. This year’s edition of Panorama brilliantly demonstrates just how much more there is to what we do. The student work you’ll see in these pages ranges from a rethinking of how planners view equity and advocacy, to examining the parallels between the legal contestation of public electricity and municipal broadband, to exploring how municipal development banks could finance green infrastructure. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. I hope that when you read through this impressive volume you’ll appreciate the breadth and depth of our students’ work as much as I do.

I think you’ll also notice just how well-suited the work our students are doing is to the big challenges facing our world. Racial equity. Climate change. Financial precarity. These are the wicked problems our students tackle every day in our classrooms and in the field. It may sound cliché, but our students truly are devoted to making the world a better place. As you’ll see, they’re already doing just that.

As the chair of the Weitzman School’s Department of City Planning, and I could not be more proud of the work coming out of our department. Happy reading!

Lisa Servon Professor and Department ChairLisa Servon was previously Professor of Management and Urban Policy at The New School, where she also served as Dean at the Milano School of International Affairs, Management, and Urban Policy. She conducts research in the areas of urban poverty, community development, economic development, and issues of gender and race. Specific areas of expertise include economic insecurity, consumer financial services, and financial justice. Servon holds a BA in Political Science from Bryn Mawr College, an MA in History of Art from the University of Pennsylvania, and a PhD in Urban Planning from UC Berkeley.

Letter from the Editors

Welcome to Panorama!

We are thrilled to bring you the 30th edition of curated student work from the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania’s Weitzman School of Design.

Planning discourse has never been more critical as we contend with global challenges of climate change, refugee crises, growing cities, and shrinking landscapes. Panorama seeks to grapple with some of these questions through the intersectional lens of planning, design, policy, and development.

This edition outlines perspectives on international development finance, community empowerment, advocacy planning, and affordable housing. It investigates the manifestations of structural racism, political activity, and public opinion on our built environment; specifically protest patterns in Minneapolis following the murder of George Floyd, the harmful influence of incarceration in California’s Alameda County, and Penn’s own opportunities to repair histories of violence and displacement in West Philadelphia.

Panorama 2022 also features studio pieces that chart ecological exploitation in Appalachia, climate vulnerability in the Caribbean Virgin Islands, flood-risk in Washington DC’s Poplar Point, and mobility infrastructure development in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay. Through interventions that combine planning, landscape architecture, and design, the students of our department co-create solutions that help us imagine our futures on the foundations of equity, sustainability, and justice.

It has been our privilege to curate Panorama 2022. We hope you enjoy it!

Yours, The Panorama Editors

Celine Apollon (she/her) is the Senior Website Editor for Panorama. She is a second-year Master of City Planning student focusing on Urban Design and Community Development. She is passionate about implementing interdisciplinary approaches between the arts, culture, and urbanism in order to continue challenging conventional practices and facilitate long-lasting and equitable community development rooted in place. Ask her anything about music, dance, art, and feminist/black urbanism!

Riddhi Batra (she/her) is a Copy Editor for Panorama and a first-year Master of City Planning student with a background in architecture. A firm believer in the potential of design and communication to transform lives, she is currently exploring the intersection of mobility, infrastructure, and public space to develop solutions for social and ecological equity. When not glued to her laptop, you can find her petting a dog (or a cat), flipping through a book, sniffing coffee beans, or clicking photographs of almost everything.

micah epstein (they/them) is a Panorama Web Editor and first-year Master of City Planning student. They are a storyteller and systems meddler raised on vast swathes of fantasy and science fiction, which taught them the power of stories to change hearts, minds, and systems. As a designer, they’ve designed web experiences for the ACLU of Washington, the MIT Media Lab, the coveillance collective, and many others. When not pushing pixels, you can find them headbanging in grimy basements or racing c*rs on their rusty fixed gear.

Clara Lyle (she/her) is a Senior Copy Editor for Panorama and a second-year Master of City Planning Candidate focusing on environmental planning and energy policy. She is passionate about supporting the growth and development of resilient, equitable cities. Prior to Penn, she lived in New Orleans for nearly seven years where she worked at the intersection of sustainability and equity. When she is not working on Panorama, you can find her walking around Philadelphia with her dog, Soupie.

Anastasia Lyons Osorio (she/her) is a Copy Editor for Panorama and a first-year Master of City Planning Candidate focusing on Housing, Community, and Economic Development. As a designer and writer, Anastasia is passionate about the power of storytelling to mediate our relationship to place and community. When not buried in readings about climate change or housing and economic justice, Anastasia enjoys hosting lavish dinner parties, going on urban adventures, and dancing to music turned up too loud.

Jackson Plumlee (he/him) is a Graphics Editor for Panorama and a second-year dual degree student in the Landscape Architecture and City Planning programs. He focuses at the intersections of design, climate justice, community organizing, and cooperative ownership. Otherwise he’s out watercoloring on location or daydreaming about his next illustration project.

Marc Schultz (he/him) is the Senior Graphics Editor for Panorama and a second-year Master of City Planning student concentrating in Urban Design. Marc aims to design happier cities, figuring out what that means along the way. He can be found trying to cook Sichuan food, losing at board games, or sitting in his West Philly garden reading Ursula K. Le Guin.

Cade Underwood (he/they) is a Senior Copy Editor for Panorama and a dual degree Master of City Planning and Law School student with a general concentration in housing, debt, and ownership. Cade studies cooperative economies, community ownership, housing financialization, public finance, the political economy of debt, and how working people can reclaim the power to their housing and labor.

48

This Place is Not a Place of Honor

Marian April Glebes

50

Dismantling Power in Planning

Amanda Peña

58

To See a Community

Julia Verbrugge; Photo series continues on p. 78, 110, 154

60

Measuring Housing Affordability

Isabel Harner

Renters' Rights

Olivia Scalora

Green New Deal: Mississippi Delta

New Deal: Appalachia

Jamaica Reese-Julien, Maria Machin, Marc Schultz, Cade Underwood, Diyi Zhang

President Harnwell outside of College Hall in 1969.

Source: University Archives and Records Center

Penn’s Broken Promises

To the Black Residents of “University City”

By Anne Berg, Jake Nussbaum, and Chi-ming YangThe COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated an already endemic housing crisis in Philadelphia, killing neighbors and destroying communities. The recent devastating fire in Fairmount took the lives of 12 people–including 8 children–all members of a low-income, extended family squeezed into a four-bedroom apartment in a neglected building owned by the Philadelphia Housing Authority.1 The fire is the latest evidence of a systemic assault on Black residents, of which housing inequity is just one of many forms of violence. As Penn watches its endowment grow to over 20 billion dollars and develops real estate across the city, tens of thousands of Philadelphians struggle to find housing, turning to friends for shelter or living on the street.2 Penn is not just complicit in this inequity; it is one of its foremost perpetrators.

As we write, 69 homes in “University City” and hundreds of Black and working-class residents are Penn-trification’s next target. Just blocks off campus, the University City Townhomes at 3900-3999 Market Street are a private development of federally subsidized units, offering below-market rates to residents, some of whom have lived there a lifetime. In 2021 the Altman Group announced plans to sell the Townhomes, refusing to renew its affordable-housing subsidies.

[1]

University City’s insatiable expansion has ensured that the site now constitutes “prime real estate.” Developers contemplate demolishing the Townhomes in favor of yet another mixed-use building boasting luxury condominiums, commercial space, or science labs.

right of “eminent domain” in 1966. Residents had no choice but to accept small payouts and leave. Those who remained faced bulldozers and arrest. A total of 2,653 people were displaced. Roughly 78% of them were Black.

[2]

The eviction is scheduled for July 2022, and residents will confront Philadelphia’s extreme shortage of low-income housing. Those who hold federal Section 8 vouchers face a closed waiting list 40,000 households long. Neither “natural” nor “inevitable,” such forced displacements are the result of concrete choices made by city and Penn administrators past and present. However, a closer look at the local history reveals that Penn community members also have a vital role to play in resisting this violence. Indeed, the struggle to stop Penntrification led to the creation of the University City Townhomes in the first place.

[4]

[5]

In 1959 the West Philadelphia Corporation – with Penn the majority shareholder – formed to redevelop West Philly as “University City.” Working with the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, the Corporation targeted the 105 acres between 34th and 40th Streets, stretching from Chestnut and Ludlow Streets in the south to Lancaster and Powelton Avenues in the north, for “renewal.” This was the Black Bottom, a vibrant Black working-class community that took care of its own. “I come from a place where I had no love… my whole community showed me love,” says long-time activist Gerald Bolling, who grew up in the Black Bottom and has insisted on reparations for over 30 years. Love didn’t faze the Redevelopment Authority, which labeled the Black Bottom “blighted” to invoke the

But anti-Black violence in Philadelphia has always been met with Black-led resistance.3 In the late 1960s, as the Black Bottom organized to defend itself, Penn students refused to sit on the sidelines. In 1967, reporters of the Daily Pennsylvanian explained the insidious term “urban renewal” as shorthand for “giant impersonal institutions like the University ofPennsylvania…devouring small homeowners, spreading segregation and prolonging social inequalities.” Two years later, some 800 Penn and Philadelphiaarea students and local Black activists occupied College Hall for six days. They demanded affordable housing within the core of University City, specifically for displaced Black Bottom residents. They forced Penn’s trustees to the negotiation table, who on February 23, 1969 resolved “a policy of accountability and responsibility that accepts the concerns and aspirations of the surrounding communities as its own concerns and aspirations.”4

Subsequently, the University proposed the creation of three affordable housing complexes for displaced residents. One eventually became the UC Townhomes, but only after a prolonged struggle between community groups and trustees that ended when a private developer, the Altman Group, bought the property at 3900 Market for $1 and committed to building affordable housing there. The other two were never built.

[3] Palmer, Walter. Web log. Blackbottom (blog). Black Bottom Tribe, April 1, 2010.

Carlson, MacKenzie S. “A History of the University City Science Center.” Penn Libraries University Archives & Record Center. University of Pennsylvania, 1999.

Saffron, Inga. “The City Desperately Needs More Public Housing. There’s a Perfect Site in West Philadelphia.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 2022.

Kasakove, Sophie, Nicholas BogelBurroughs, Frances Robles, and Campbell Robertson. “18 People, a Deadly Fire: For Some, Crowded Housing Is Not a Choice.” The New York Times, January 8, 2022.

[3] Palmer, Walter. Web log. Blackbottom (blog). Black Bottom Tribe, April 1, 2010.

Carlson, MacKenzie S. “A History of the University City Science Center.” Penn Libraries University Archives & Record Center. University of Pennsylvania, 1999.

Saffron, Inga. “The City Desperately Needs More Public Housing. There’s a Perfect Site in West Philadelphia.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 2022.

Kasakove, Sophie, Nicholas BogelBurroughs, Frances Robles, and Campbell Robertson. “18 People, a Deadly Fire: For Some, Crowded Housing Is Not a Choice.” The New York Times, January 8, 2022.

Although the UC Townhomes were meant to house families displaced by the creation of University City, they never came close to compensating for that devastation. Today, those very same homes are targeted for destruction.

Philly politicians have recognized this injustice but fail to provide a viable solution.5 The legislation amended by the city council on November 4, 2021 extends the time to eviction beyond the currently projected 6 months, but offers little beyond that. In fact, it stipulates that only 20 percent

of the current units must be preserved as “affordable” –itself an amorphous term measured against median income, which the continuing displacement of low-income residents will only adjust upward. If ratified, the legislation would reinforce the violent logic of the market, leaving most residents to fend for themselves.

What Altman purchased for $1 is now worth over $100 million. By its sheer presence, Penn increases property value around its perimeter, or more bluntly,

Above: A visualization of the structures proposed for what was to become University City.

Source: 1950 University Redevelopment Area Plan by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission

Above: A visualization of the structures proposed for what was to become University City.

Source: 1950 University Redevelopment Area Plan by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission

within its police patrol zone, incentivizing the sale of any and all land to the highest bidder while professing benevolence.

On December 14, 2021 the Coalition to Save UC Townhomes, comprised of Penn faculty and students, the Black Bottom Tribe, housing justice organizers, and West Philly community members working alongside Townhomes residents, held a teach-in on campus calling on Penn to honor the Trustees’ 1969 commitment to a “policy of accountability.”6 After decades of broken promises it is time for innovative solutions to the racialized inequalities that rip through our city. An extension for residents to stay in their homes, considered by current legislation, is only the bare minimum. Residents also need access to Section 8 vouchers right away, without which they can’t even apply for subsidized housing.

But residents deserve justice. Penn should use its wealth and brain power to support a tenantowned cooperative or a Community Land Trust that would enable home ownership and guarantee permanent affordability as an immediate down payment on its debt owed to the community.7

This is a moment of reckoning for the University and its incoming President, M. Elizabeth Magill; a chance to begin the process of repairing the violence of Penn-trification. Penn created University City by displacing Black working-class residents, now it must take responsibility and ensure that Black workingclass people, who are here now, can stay.

“Although the UC Townhomes were meant to house families displaced by the creation of University City, they never came close to compensating for that devastation. Today, those very same homes are targeted for destruction.”Right: A site plan of the affordable housing structures agreed upon by the Quadripartite Commission, drawn by The Young Great Society Architecture and Planning Center, 1969. [6] Bond, Michaelle. “Penn Students and Staff Rally to Help Preserve Affordable Housing for West Philadelphia Residents.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 14, 2021

Anne Berg is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania.

Jake Nussbaum is a community organizer, artist, and Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Chi-ming Yang is Associate Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania.

They write on behalf of the Coalition to Save the UC Townhomes, whose email is: saveuctownhomes@gmail.com. Members of the Coalition and endorsers of this letter include:

Black Bottom Tribe

Black Lives Matter – Philadelphia

Penn Housing For All

Philadelphia Housing Action

Police Free Penn Reclaim Philadelphia

Home Repair We Need to Prioritize Home Repair Interventions in Philadelphia

Above: Middle Class Row House in Black Neighborhood of North Philadelphia, August 1973.

Photographer: Dick Swanson

Source: The U.S. National Archives

By Cade UnderwoodPhiladelphia’s housing crisis—decades in the making, exacerbated dramatically by COVID-19—is overwhelmingly due to the reduction of affordable units. Between 2000 and 2014, Philadelphia lost one out of five housing units with rents that fell below $750 per month. Part of this decline is residents—both homeowners and tenants—have lost homes because they were unable to maintain them.1 Between 2015 and 2017, around 75 percent of low- to medium-income homeowners have been denied home repair loans from traditional lenders, meaning that many of our neighbors are struggling quite literally to keep a roof over their head.2 As we try to recover from a year of profound instability, a growing mountain of evidence is showing that home repair interventions are uniquely powerful tools for equitable city redevelopment.

Home repair is one of the few existing redevelopment tools that strives to keep people in their homes. Devoting public dollars to opportunity zones and abatements on new construction frequently leads to rising prices and the displacement of longtime residents. But investing in home repair for low-income homeowners – especially in a city with one of the highest rates of Black homeownership in the country – grants communities the stability to stand against gentrification, exploitation, and climate change.

In an era of decreased state and federal support, the City of Philadelphia has been locally funding home repair interventions for decades.3 Philadelphia launched its Basic Systems Repair Program (BSRP) in 1995 to provide free repairs to low-income owner-occupied homes.4 More recently, the City of Philadelphia and Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority launched a new initiative, Restore, Repair, Renew (RRR), to help lower income homeowners access low-interest loans for home repairs.5 RRR is specifically for homeowners who make too much for BSRP but do not qualify for traditional financing. These two programs operate alongside several other targeted critical interventions such as adaptive modifications for residents with intellectual and physical disabilities, weatherization for climate resiliency, and HVAC repairs for greater energy efficiency. Homeowners frequently need to apply for several programs to approach their home’s repair needs holistically. Precisely to address this, The Philadelphia Energy Authority (PEA) has launched a pilot program –Built to Last – designed to support homeowners with needs that span across multiple programs.6 PEA’s whole home approach is predicated on not just the intersection of homeowner needs, but also on the fact that stable housing is fundamental to a safe and resilient society. Philadelphia has been making impressive strides on public home repair

“Investing in home repair for low-income homeowners— especially in a city with one of the highest rates of Black homeownership in the country—grants communities the stability to stand against gentrification, exploitation, and climate change.”

interventions, which is commendable. However, these programs often have long waitlists and often do not fully meet low-income homeowners’ needs. As new studies on health, safety, and climate are released, we know now that every dollar spent on repairing homes is not simply stopping homes from collapsing on our neighbors. The following studies demonstrate how every dollar spent on repairing homes is also associated with falling crime rates, increased public health, intergenerational wealth building, and climate change mitigation.

Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has identified decaying homes as a central culprit in preventing asthma in Philadelphian children.7 Through their CAPP+ home repair projects, they have seen a reduction of 40 to 50 percent in hospitalization rates in communities they serve.

[1] Howell, Octavia. 2020. “The State of Housing Affordability in Philadelphia.” Pew Trust.

[2] McCabe, Caitlin. 2018. “Getting a home improvement loan in Philly is harder when you’re low-income or a minority, study shows.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 27, 2018.

[3] Blumgart, Jake. 2016. “What’s at stake if Toomey and Trump cut funding to Philly?” WHYY, December 2, 2016.

[4] “Basic Systems Repair Program | Making Philadelphia Better Block by Block.” n.d. Philadelphia Land Bank.

Home repair and maintenance also have critical impacts on public health and environmental justice.

Older residential properties often contain unremedied lead, untreated mold, and leaky roofs. Gas hookups for stoves and other appliances are correlated with higher rates of asthma in children. These inefficient homes have external costs: In Philadelphia according to the Office of Sustainability, buildings and industry constitute 79 percent of our city’s greenhouse gas emissions 8

Home repair interventions are uniquely positioned to attack all these problems at once. Home repair unites affordable housing work, the fight for racial justice, and public health. Critically, it also is imperative for meeting environmental justice goals. The energy needed to repair a home compared to that required to build a new one (and demolish and cart away the remains of an older one) is much lower.9 Furthermore, home weatherization makes those homes more efficient as well as sturdier against the rainwracked, increasingly disastrous

storms that characterize our era of climate change.

New research also shows a significant association between home repair and crime reduction in Philadelphia. Contrary to the debunked “broken-windows theory” that has been used to justify heightened policing, this research suggests something critically different. 10 These repair programs help our neighbors feel secure, stress-free, and comfortable in the place that they already call home. The residents who are integral and historic parts of their neighborhoods are the experts on how to keep their own communities safe – not outside agents like the police. And these residents can only keep their neighborhoods safe when they have stable homes in those neighborhoods.

Lastly, long-term homeowners of well-maintained homes can pass those homes down as intergenerational wealth. In a city of Black homeowners, this is critical to building intergenerational wealth in

[5] “Restore Repair Renew | Making Philadelphia Better Block by Block.” n.d. Philadelphia Land Bank.

[6] “Built to Last.” n.d. Philadelphia Energy Authority.

[7] “Repairing a Home, Improving a Child’s Health: CAPP+.” n.d. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Accessed February 20, 2022.

[8] City of Philadelphia Office of Sustainability. 2020. Powering Our Future: A Clean Energy Future for Philadelphia. N.p.: Greenworks Philadelphia.

Council President Darrell L. Clarke in Olney celebrating fresh funding for the Basic Systems Repair Program.

Source: Jared Piper/ PHL Council Fellow

communities of color.11 Years of racist lending practices encoded in federal policy were designed to exclude Black homebuyers from lending and housing markets: from denying access to federally subsidized mortgage lending programs (“redlining”) to practices of locking Black people into substandard properties with punishing loan terms (what the scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls “predatory inclusion”).12

pleads “poverty” in response to public calls for greater spending, a response that could not be more mendacious than today, when the Pennsylvania legislature sits on billions of unspent federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan.13 Importantly, it is not just Philadelphia; the need for home repair is clear across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. In its 2020 Pennsylvania Comprehensive Housing Study, the PA Housing Finance Agency (PHFA) found that Pennsylvania has one of the oldest housing stocks in the country and that age correlates strongly with the need for repair.14 It is long past time for Harrisburg to begin investing heavily in the infrastructure for all Pennsylvanians to access holistic home repair programs.

[11] Hyun Choi, Jung, and Alanna McCargo. 2020. “Closing the Gaps,” Building Black Wealth Through Homeownership. Urban Institute.

In many respects, it isn’t surprising that the project of home repair offers an unparalleled look into the profound difficulties, and potential solutions, facing our city and state. And there are still more aspects of the idea that have yet to receive sufficient attention. For example, the extent to which a home repair program could include renters, by having grants to landlords be contingent on guaranteeing deedrestricted affordability. The history and success of existing programs, however partial their implementation and despite the overall lack of federal and state support, suggests the power of home repair as well as the need to do more.

Recent polling from Data for Progress suggests that investing in programs designed to make our homes more efficient has support across the political spectrum in Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania legislature often

Lastly, while the City of Philadelphia has made strong efforts in home repair, it has yet to consider public programs for home repair as big budgetary priorities. Extensive research suggests home repair interventions could be a powerfully efficient use of city funding to foster safer neighborhoods, less displacement, stronger communities, and intergenerational wealth. It is time for Philadelphia to make home repair a central budget priority.

[13] Southwick, Ron. 2021. “Pa. received $7.3 billion in federal COVID-19 rescue aid. The new state budget spends $1 billion of that money.” PennLive. com, June 25, 2021.

[14]

Cade Underwood is a dual degree Master of City Planning and Law School student with a general concentration in housing, debt, and ownership. Cade studies cooperative economies, community ownership, housing financialization, public finance, the political economy of debt, and how working people can reclaim the power to their housing and labor.

[9] F Pittau et al. 2019. “Environmental consequences of refurbishment vs. demolition and reconstruction: a comparative life cycle assessment of an Italian case study.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 296. [12] Taylor, KeeangaYamahtta. 2019. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. N.p.: University of North Carolina Press. PA Housing Finance Agency, Vincent Reina, and Claudia Aiken. May 2020. Pennsylvania Comprehensive Housing Study. N.p.: PA Housing Finance Agency. [10] South EC, MacDonald J, Reina V. Association Between Structural Housing Repairs for LowIncome Homeowners and Neighborhood Crime."Home repair unites affordable housing work, the fight for racial justice, and public health. Critically, it also is imperative for meeting environmental justice goals.”

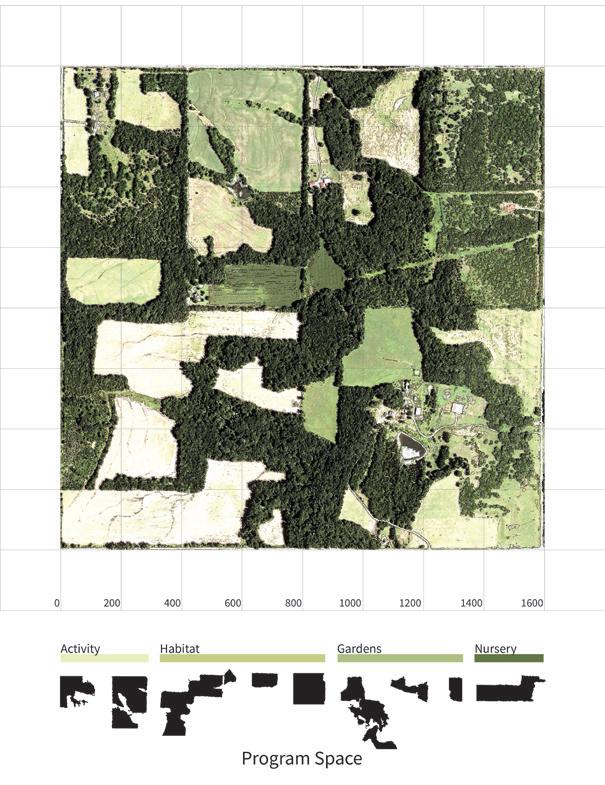

Fostering Connections

In Ciudad del Este

Instructor: David Gouvernour

Students: Yanhao Chai, Selina Cheah, Hanyu Gao, Linda Ge, Tristan Grupp, Samuel Hausner-Levine, Yue Hu, Ruoxin Jia, Clara Lyle, David Nugroho, Jiamin Tan

Situated at a triple frontier border of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, Ciudad del Este has become an important commercial and trading center, attracting visitors from across the borders and from the greater international region thanks to the diversity of products, competitive prices, and deregulated trade. However, the growth of the city has not been met with necessary planning or provisions and in turn, its urban form, mobility systems, and city services have evolved informally. As a result, it has become a hybrid city where the natural and the urbanized, the formal and the informal, the regulated economies and the contraband, national investments and the local interests, merge and compete.

The central commercial core of the city, called the Microcentro, overflows with activity and vitality and struggles with high levels of highly congestion, especially during the daytime. Meanwhile, while informal settlements at the outer fringe lack infrastructure, services, public spaces, and amenities, forcing most of their residents to commute to access better jobs and the services in the center city.

The Paraguayan and Brazilian governments are jointly investing in the construction of a new bi-national bridge and a peripheral road on the cities on either side of the border, which is expected to have a major impact on city performance and urban growth. This new mobility system will help decongest the central core, by rerouting regional transit and will bring new development pressures to the southern tip of the city and its neighboring departmentos. Ciudad del Este envisions the new bridge as an opportunity to further position the city as a major trading, industrial and high-tech center of the country and the region.

This studio asked participants to foresee and maximize the benefits of this new bridge & ring road initiative, and to ponder possible unwanted effects or unexpected trends, in a holistic and multiscaler approach. Participants were asked to foster spatial and performatives connections that would result in added value to the city. These included:

• Merging the ecological aspects with the urban systems (crucial in such a special natural setting)

• Envisioning the urban changes that will be brought about as the new bridge and peripheral road are completed

• Improving living conditions in the informal settlements and planning for the emergence of new ones (acknowledging that informal urbanism is and will be an important driver of city making)

• Interconnecting macro-economic formal economies with the micro-informal commercial, manufacturing and service-oriented drivers,

• Positioning Ciudad del Este as a progressive/ experimental city projected to the national and regional context without losing its unique cultural identify

These topics were tested by simultaneously analyzing urban dynamics at a metropolitan scale while exploring them in detail at a site-specific scale through pilot projects, from which the public sector and the private sector, as well as the local communities, can derive future policies and implementable courses of action.

This design integrates community agriculture, housing, local commerce, and water management into the same area to create a self-sustaining community that thrives through interdependence.

On the Paraguayan side of the new Puente de la Integración, a park provides a place of recreation and cover from the heat. In the background, a proposed gondola connects tourists and residents between the Iguazu Falls and the Monday Falls, two of the most stunning natural assets in the region.

What Counts as Infrastructure

In Philadelphia, what counts as infrastructure? What deserves repair and maintenance?

by A.L. McCullough, Daniel Flinchbaugh, and Ari VamosAMERICAN INFRASTRUCTURE THROUGH THE LENS OF THE BIPARTISAN INFRASTRUCTURE FRAMEWORK

On November 15, 2021, after more than six months of debate, President Biden signed H.R. 3684, more commonly known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework (BIF), into law.1 What the BIF includes and doesn’t include, what it prioritizes and doesn’t, illustrates what constitutes infrastructure in the American political imagination. Infrastructure is not an objective term; rather, it represents a collective agreement about which aspects of the built environment sustain life and deserve continual repair. Using the BIF as a view into this political imagination, we see that some physical assets are understood as essential for the collective life of the nation–bridges, for example–while other places and systems get left behind—such as public schools.

The BIF negotiations ended with a total of $3.2 billion dollars for bridge repair and maintenance over five years, the largest investment in bridges since the inauguration of the interstate highway system.2 Meanwhile, schools were parsed out a meager sum. The BIF’s investments in schools are drops in the bucket: so-called clean buses, eliminating lead contamination in school drinking water, and grants for energy efficiency improvements, renewable energy improvements, and an energy efficiency materials pilot program.3 These programs hardly represent a landmark investment in public school facilities across the country. This is not to say that the crumbs of BIF won’t improve schools—lead-free drinking water is both a necessity and a right. But this is a marginal investment in programs which, without full funding, programmatic and technical support, will not last beyond five or ten years.

Philadelphia Infrastructure

Playing Cards

Strawberry Mansion Highschool

Central Highschool

Andrew Hamilton Elementary

Year built...........1977

Last Repaired..........NA Programs......grades 9-11 .music production .........culinary ......photography .........drumline .......basketball ......volley ball .....voting venue

Philadelphia Infrastructure: School

Strawberry Mansion Bridge

Year built...........1836

Last Repaired........1937 Programs......grades 9-12 .Barnwell library .IP & AP programs .school newspaper .......chess team ....robotics team .......basketball ......volley ball

Philadelphia Infrastructure: School

Twin Bridges

Year built...........1968

Last Repaired........2021 Programs.......grades K-8

...garden program ......greenhouses ..........orchard ............music ..............art ....robotics Team .....voting venue

Philadelphia Infrastructure: School

Grays Ferry Bridge

Year built...........1976

Year built...........1896

Last Repaired........1995 Programs...14,500 car/day

........two lanes ...sidewalks

Philadelphia Infrastructure: Bridge

Year built...........1960

Last Repair..........2010 Programs..109,000 car/day .......PA Route 2 ...Roosevelt Blvd ........six lanes

Last Repaired........2021 Programs...21,333 per/day

.......pa route 2

..grays ferry ave ........six lanes .......bike lanes ........sidewalks

Philadelphia Infrastructure: Bridge

Philadelphia Infrastructure: Bridge

[1] Peter A. DeFazio, “Text - H.R.3684117th Congress (20212022): Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act,” legislation, November 15, 2021, 2021/2022.

[2] “FACT SHEET: Historic Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal,” The White House, July 28, 2021.

[3] DeFazio, “Text - H.R.3684 - 117th Congress (2021-2022).”

[4] Walter Licht, Mark Frazier Lloyd, J.M. Duffin, & Mary D. McConaghy, “West Philadelphia Collaborative History - Bridging the Schuylkill: Early- to Mid-19th Century,” accessed March 5, 2022.

[5] “The Bridges of Market Street,” Schuylkill Banks, February 16, 2021; Leonard, Joe. “Rehab Project to Close Chestnut Street Bridge for a Year, Add Bike Traffic Signals,” Philadelphia Business Journal, September, 2017.

[6] Kristen A. Graham, “Philly School Buildings Need Nearly $5B in Repairs, New Report Says,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan 26, 2017.

Bridges weren’t always considered infrastructure. In the early days of Philadelphia’s history, residents navigated the city’s rivers through a combination of ferries and pontoon bridges, and there was no consensus on the need to construct permanent river crossings until the early 19th century.4 Since then, however, a series of investments have marked bridges as necessary for the collective life of the city—the Market Street Bridge alone has been rebuilt and repaired five times since its construction in 1805 and is slated for another round of repairs soon. 5 When bridges must be closed because of safety issues or disrepair, there is disruption for entire communities—it complicates supply chains and the lives of families in equal measure. Philadelphia is a city of bridges, its urban fabric woven together by threads of crossing; but it is also woven together by our school communities–and they have and are being left behind. The crises of recent years have highlighted the disruptions from Philadelphia school’s state of disrepair.

Why not compare bridges and schools in terms of their status as infrastructure? Both bridges and schools are vital pieces of the built environment that sustain life and lead to thriving communities. We compare bridges and schools in Philadelphia as contrasts of what constitutes infrastructure in the political imagination of the US—one counted and one contested. Schools must gain status as infrastructure in the political imagination and receive investment with a level of national funding, support and maintenance appropriate for indispensable, life-sustaining pieces of the built environment.

OVER TIME, SCHOOLS IN CRISIS

In Philadelphia, public schools are in crisis. The School District of Philadelphia has a $3.5 billion backlog for “immediate upgrades” for its facilities. 6 School facilities in Philadelphia are plagued with four major hazards; every day, students walk into

[7] Kristen A. Graham, “98% of Philly Schools Tested in a New Study Had Some Lead-Containing Water; District Disputes Findings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb 16, 2022.

[8] Neena Hagen, “Asbestos Troubles at Masterman Raise Safety Concerns about Some Other Philly Schools as First Day Looms,” WHYY, August 17, 2021.

Why not compare bridges and schools in terms of their status as infrastructure? Both bridges and schools are vital pieces of the built environment that sustain life and lead to thriving communities.

facilities with lead in their drinking water,7 cracked asbestos floor tiles,8 mouse droppings on their shelves, and mold forming on their seats and on their carpets.9 These daily hazards are compounded by accidents and disasters. In 2016, a maintenance worker lost his life in a boiler explosion at a Philadelphia public school.10 In 2018, heavy rain caused flooding and ceiling collapse at another.11 The same year, students lost hours of school due to heat wave conditions their facilities couldn’t handle. 12 In 2021, a teacher was hit with debris while in an elevator at a third school.13 Whether an accident, disaster, or an everyday hazard, Philadelphia public school facilities are in crisis and they are endangering students and workers.

School facilities are a $5 billion problem that requires a $3 billion expenditure to address urgent needs; without a major investment in repair and maintenance now,

[9] Barbara Laker, Wendy Ruderman, and Dylan Purcell, “Toxic City: See How Much Lead, Asbestos and Mold Is in Philadelphia Schools,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 2018.

[10] Mike Dougherty, “Worker Dies Months After Boiler Explosion At Philadelphia School,” May 19, 2016.

[11] Tribune Staff Report, “Heat Wave Causes Philadelphia Public Schools to Close Early,” The Philadelphia Tribune, September 4, 2018.

[12] Kristen A. Graham, “Philly Schools to Close Early Wednesday; Officials Decry ‘Dangerous’ Conditions inside Schools,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Sep 4, 2018.

[13] Emily Rizzo, “Masterman Teachers and Parents at Odds with District over Asbestos Fears,” WHYY, August 26, 2021.

the problem will only continue to grow.14

Throughout the history of the School District of Philadelphia, investments in school facilities have been catalyzed by crises. The first was a crisis of numbers: in the early 20th century, Philadelphia’s population soared, putting immense pressure on already overcrowded schools.15 In 1909, classroom space was so scarce that one third of Philadelphia’s public school students could only attend school part time. 16 In 1911, when the state legislature allowed the District to borrow funds, Philadelphia began to build schools at an unprecedented rate, constructing 104 over the next 25 years.17 To make the case to the people of Philadelphia that they should pay for this massive investment in school facilities, District leadership framed schools as community infrastructure : in his 1911 report, School Board President Henry R. Edmunds called for “a new conception of the functions of the public school.”18 He continued:

“To-day, a multitude of interests are being cared for by the public school system which no one dreamed

of…medical inspection, vocational training, music, physical training, social centers, open air classes, evening lectures to adults, school gardens and summer playgrounds. … There is a growing tendency for the community to regard the school as the center of much of its social life.”

In the 1930s, school construction in Philadelphia accelerated due to a national crisis: the Great Depression. As communities across the country struggled through economic collapse, the federal government poured money into the nation’s infrastructure through the Public Works Administration (PWA). The PWA produced classic pieces of infrastructure such as the Triborough Bridge in New York, Reagan National Airport in Washington, DC, and the Grand Coulee Dam; this large umbrella of “public works” also included schools.19 In Philadelphia, PWA funds supported the construction of several large, key public schools, including Bok, John Bartram, and Central High Schools.20 These major investments in schools not only stimulated the local construction industry and created jobs; they also modernized the city’s educational system and

[14] Graham, “Philly School Buildings Need Nearly $5B in Repairs, New Report Says.”

[15] Ken Finkel, “The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia’s Schools,” City of Philadelphia: The Philly History Blog: Discoveries from the City Archive, December 9, 2011.

[16] “The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia’s Schools.”

[17] Steven Ujifusa, “Irving T. Catharine, Philadelphia’s School Design Czar,” City of Philadelphia: The Philly History Blog: Discoveries from the City Archive, February 27, 2020.

[18] Philadelphia

(PA) Mayor, Annual Report of the Mayor of Philadelphia: Containing the Reports of the Various Departments, 1912.

[19] “Public Works Administration (PWA) (1933),” Living New Deal (Department of Geography, University of California Berkeley CA), November 18, 2016.

Above: Four Rooms in a Philadelphia School Facility. Source: Wenjing Fang, Jerry Shang, A.L. McCullough, and Tracy Zhangimproved the quality of life for children and neighborhoods alike.

Irwin T. Catharine, the School District architect who oversaw the city’s school building boom from 1920 to 1937, campaigned for modernizing schools to address fire safety and overcrowding, but also to provide amenities such as school gardens, rooftop recreation spaces, and cafeterias.21 As anyone who’s walked around Philly’s neighborhoods can attest, Catharine’s school buildings are also beautiful; ranging in style from Gothic Revival to Art Deco. Catharine schools demonstrate a level of architectural care and investment that mark their status as major pieces of community infrastructure.

None of this is to say, however, that school funding in Philadelphia has ever been adequate or equitably distributed. As Erika Kitzmiller notes in her history of Germantown High School, during the school construction boom in the early 20th century, the District lacked the funds to construct and run all the

schools the growing city needed.22 Many schools relied on parent fundraising and partnerships with charitable organizations, creating inequality between wealthy communities that could afford to subsidize their schools and others that could not.23 These inequalities laid the foundation for a second crisis. As schools integrated, white families fled to the suburbs, taking tax dollars

with them and further destabilizing the city’s already precarious school funding. This second crisis did not spur renewed investment in public schools. Instead, as postwar Philadelphia’s population and public school students became increasingly Black, private and public funding for schools collapsed, precipitating the ongoing budget crisis we see in the District today.24 Rather

[20] “Edward W. Bok Technical High School - Philadelphia PA,” Living New Deal (Department of Geography, University of California Berkeley CA), January 4, 2015.

[21] Philip Jablon, “Why All Philly Schools Look The Same,” Hidden City Philadelphia, June 29, 2012.

[22] Erika M. Kitzmiller, “The Roots of Educational Inequality: Germantown High School, 1907–2011” (Ph.D., United States -- Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania), 2012.

[23] Kitzmiller, “The Roots of Educational Inequality.”

"Maybe this time, crisis can help schools take their rightful place as infrastructure in the political imagination.”

than viewing schools as pieces of infrastructure deserving of ongoing maintenance and investment, the School District of Philadelphia and the statecontrolled Philadelphia School Reform Commission used a logic of “austerity urbanism” to justify closing schools in predominantly low-income, Black and brown neighborhoods. 25 So even when and where there was funding to

CONCLUSION: A CALL FOR REPAIR AND MAINTENANCE

Maybe this time, crisis can help schools take their rightful place as infrastructure in the political imagination. After almost two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown public school facilities to be essential elements of American infrastructure as caretakers, students, and workers fight to

[24] Michael Clapper, “School Design, Site Selection, and the Political Geography of Race in Postwar Philadelphia,” Journal of Planning History 5, no. 3 (August 2006): 241–63.

support Philadelphia’s school infrastructure, investments in schools primarily served the needs of white children and majority-white neighborhoods. These inequities provide further evidence that school facilities were never seen as truly “public” infrastructure, meant to serve everyone in a city or its neighborhoods.

keep them open, safe, and healthy. Yet, during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures almost no dent was made in the multibillion-dollar backlog in Philadelphia school facility maintenance. After 536 days out of the school buildings, students and workers returned to Philadelphia schools to find little changed; they found schools which continue to expose them to toxic materials such as asbestos, lead, mold, and vermin.

As we face the overlapping and intensifying crises of COVID-19, toxic school facilities, and climate change, schools must again become essential pieces of community infrastructure in the political imagination as places of health, gathering, learning, and support. Like the architects of the school construction boom in the early 20th century, we can go beyond addressing the urgent needs of the moment and invest in schools as long-term neighborhood infrastructure. The children of Philadelphia deserve more than the bare minimum of a safe, healthy school; they deserve beautiful,

[25] Ariel H. Bierbaum, “Managing Shrinkage by ‘RightSizing’ Schools: The Case of School Closures in Philadelphia,” Journal of Urban Affairs 42, no. 3 (April 2, 2020): 450–73.

[26] Akira Drake Rodriguez, Daniel Aldana Cohen, Erika Kitzmiller, Kira McDonald, David I. Backer, Neilay Shah, Ian Gavigan, Xan Lillehei, A. L. McCullough, Al-Jalil Gault, Emma Glasser, Nick Graetz, Rachel Mulbry, and Billy Fleming, “Transforming Public Education: A Green New Deal for K–12 Public Schools,” Philadelphia: climate + community project, 2021.

Below: Plaque on Falls Bridge."The children of Philadelphia deserve more than the bare minimum of a safe, healthy school; they deserve beautiful, joyful spaces to learn and grow.”

joyful spaces to learn and grow. Philadelphia’s neighborhoods deserve schools that go beyond simply warehousing children for the day so that parents can work. They deserve multifaceted pieces of community infrastructure that are cared for and renewed.

So how is a story about bridges also a story about schools? Bridges tie together communities, they facilitate work, and their continual repair and maintenance provides good jobs—and so too, do public schools. Public schools are infrastructure, from Philadelphia to Arkansas to Oregon—and recognizing public schools as infrastructure in the political imagination means demanding national financial support for repair and maintenance. It is a call to address Philadelphia’s and every other school district’s backlog with novel formations, such as the Green New Deal for K-12 Public Schools.26 It is a call to invest robustly in each piece of infrastructure which, like the weave of the cloth, binds together the threads of living, working, playing, and learning.

Daniel Flinchbaugh is in his final year in the Master of Landscape Architecture program. He earned his BFA focusing on landscape painting and sculpture at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. He now uses his artistic abilities to visually communicate complex ideas to a broader audience.

Ari Vamos is a second-year Master of Landscape Architecture candidate at the Weitzman School of Design. They hold a Bachelor of Arts in Urban Studies from Vassar College with a concentration in gender, power, and the built environment. Before Penn, they worked in urban agriculture, community organizing, and neighborhood economic development in Philadelphia.

A.L. McCullough is a landscape architect based in Philadelphia and a member of climate + community project.Getting to Green

Connected Spaces for Environmental Justice and Stormwater Management at Sayre High School

BACKGROUND

Team: Henry Feinstein, Iain Li, Shawn Li, Saffron Livaccari, Cassandra Owei, Jackson Plumlee, Noëlle Raezer, Lorraine Ruppert, Amisha Shahra, Mrinalini Verma, Corey Wills, Haoge Xu

Advisor: John Arthur Miller

Sayre High School (Sayre), located in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood of West Philadelphia, has many assets; an onsite health center, a small garden program, and beautiful student-created murals all serve to create a vibrant community hub. However, Sayre falls within a combined sewer overflow (CSO) area, meaning that during rain events, stormwater and wastewater mix into the same pipes. During rain events, that mixture will overload the combined sewer system, and the excess will overflow into the local waterways. The sewer outfall for Sayre is located just north of Eastwick, a historically marginalized Black community in Philadelphia which experiences chronic issues from flooding and pollution.1 Therefore, the lack of onsite stormwater management at the school not only negatively impacts the school’s students and staff, but also downstream communities.

Additionally, the school is located in the hottest 10% of the city, with an average summer temperature that is up to 7.8°F above other neighborhoods. A recent analysis conducted by Itay Porat (MCP ‘22) found that Sayre is actually the hottest area within West Philadelphia, with temperatures reaching up to 17°F above the rest of the city. These temperatures, created by an urban heat island effect are dangerous to all residents, especially children and the elderly.

The school also lies within a food desert, which means there is a lack of access to fresh produce and other nutritious food at affordable prices. Additionally, according to the 2018 American Community Survey, the median household income in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood is $32,746; over $10,000 less than the median city-wide household income of $43,744. 44.2% of children below the age of 18 in the neighborhood are living below the poverty line – nearly 10% higher than Philadelphia overall.2 As Cobbs Creek’s residents are 93.1% Black, these economic

[1] The demographic statistical atlas of the United States— Statistical atlas. (2018, September 14).

[2] United States Census Bureau. American community survey. (2018).

[3] School District of Philadelphia. School profiles. (2021).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Pennsylvania Department of Education. 2019 Keystone Results. Department of Education. (2019)

[6] Kuo, M., Barnes, M., & Jordan, C. “Do Experiences With Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-and-Effect Relationship.” Frontiers in Psychology, 10 (2019). 305.

indicators and demographics compelled the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to classify the area as an Environmental Justice Area.

Sayre’s student body follows the pattern of Cobbs Creek; 90.9% of the school is Black, and at the time of this study, all but one student met the threshold for free lunch eligibility. The school has

heat, food access, poverty, and education. To mitigate these challenges, GSI can lower the school’s stormwater fee, mitigate flooding, alleviate the urban heat island effect, beautify public spaces, provide valuable STEAM education opportunities, and provide access to fresh healthy food for students and the surrounding community. With this in mind, a team of Penn students

"Green stormwater infrastructure can lower the school’s stormwater fee, mitigate flooding, alleviate the urban heat island effect, beautify public spaces, provide valuable STEAM education opportunities, and provide access to fresh healthy food for students and the surrounding community.”

a 45% four-year graduation rate (compared to an 86% state average) and a 16% college matriculation rate in 2019.3 According to the Philadelphia School District’s website, Sayre’s educational attainment scores trail behind their local counterparts, with 0% of students attaining Proficient or Advanced levels on the state standardized math exam and only 11% of students attaining Proficient or Advanced levels on the state standardized English exam. 4 When looking at standardized test scores, Sayre lags significantly behind Pennsylvania state averages. Results for the 2019 Keystone Exams - Pennsyvlania’s public school standardized testing system - scored Sayre students at between 8-16% proficient across literature, algebra, and biology, while the state averages hover around 70%. 5 Several studies have shown that exposure to green spaces, including green stormwater infrastructure (GSI), can boost students’ scores.6

Overall, the school has issues with combined sewer overflows,

is collaborating with the Netter Center for Community Partnerships, the Philadelphia Orchard Project, Mural Arts, the School District of Philadelphia, the Water Center at Penn, the Sayre Health Center, Penn Praxis, and the Philadelphia Water Department to co-design, fund, and ultimately implement a GSI installation at the school which will also act as a green space for recreation and gathering while providing a multitude of nutritional, environmental, health, and educational cobenefits. Design elements will include a green roof, rain gardens, permeable pathways, bioswales, tree trenches, a greenhouse, and raised beds.

COMMUNITY SURVEYS

To fully understand the Sayre community’s priorities, Penn students and Netter Center staff created a survey and conducted site visits to work with the students, staff, and parents of Sayre. These initial surveys will be followed by a series of interactive workshops which will be carried out in

spring of 2022 to gather more nuanced information and enhance community ownership of the design.

Survey respondents identified several existing challenges:

• “The flooding made it hard for me to get to work. The temperature in my room can be very hot.”

• “Very sunny in my classroom all day; it is hot inside the classroom in warm months and cold during the winter months; Little greenery to enjoy.”

• “It is, sometimes, too hot or cold in the building. It seems it’s hard to get the right balance.”

• Respondents’ visions for the space include:

• “A place where the students can spend their lunch period so they do not have to spend

their time in the cafeteria.”

• “I would really love to see a place for students and the community to gather and enjoy the outdoors.”

• “A more natural look around and inside the building; edible plants to eat; plants/ grass on roof.”

• “Outdoor classroom space and a place for science classes to do outdoor studies.”

• “With the pandemic I think it is most important for students to have a green space outside to relax, and where it is safe. There are articles that talk about the number of trees and green space associated with socioeconomic levels.”

• “The courtyards and grounds are becoming green with lots of pretty plants. A garden area to teach students how to grow edible plants.” ,

DESIGN SOLUTIONS: PERMEABLE PATHWAYS

Permeable pavements are porous surfaces that allow water to penetrate through into the soil while filtering pollutants. The incorporation of permeable pavement in our design will help to create a healthier and pollutionfree environment for the Sayre community. In addition, permeable paving has cooling effects that would work to reduce temperatures in the surrounding environment. To this end, at the south of the

distribution, and a market stand. The pathway expands upon the existing food distribution program in the health center by connecting the school with a greenhouse and raised beds; produce from which will be distributed to the community. This pathway also reconnects the school with the active recreation spaces of the Sayre Recreation Center. The two facilities will share the infrastructure at different times of the day. The existing basketball courts will be renovated to include

school, a former service drive will be repurposed as a permeable, shaded, and flexible corridor that prioritizes pedestrian connectivity and stormwater capture while allowing service access and a variety of uses at different times of the day.

The promenade features spaces for community gathering, food

shaded seating spaces, while lighting will be added to ensure this space is safely usable in the evening as well.

DESIGN SOLUTIONS: HEALTH CENTER FARM STAND

Our survey responses showed that most of the staff and students at Sayre High School

would like to see their school beautified. This can take place in a variety of ways, such as planting beautiful flowers in the rain gardens, managing overgrown plants, and overall reducing the concrete space in the central courtyards which the classrooms overlook. Redesigning the school’s parking lots and recreational centers will make the school a more accessible community gathering space for the greater Cobbs Creek neighborhood. With the addition of benches and a greenery, the parking lot can be converted into an outdoor venue for weekend farmers markets in which the students call showcase their produce from the school gardens, as well as being a space for other community events.

An existing program which takes place in the school’s health center sells food grown in the central courtyard to surrounding residents and health center visitors at affordable prices. Our design amplifies and celebrates this connection between the school and the surrounding community by providing a dedicated space along the promenade for a greenhouse, farm stand, seating, and raised garden beds. As a hub for demonstration, education, and connection, the greenhouse showcases stormwater collection from the roof and its reuse for irrigation of the plants in the greenhouse.

DESIGN SOLUTIONS: COURTYARD RAIN GARDENS

Access to, or even a view of, nature can have a lasting positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction levels, well-being, and stress levels.7 GSI can provide both access to and, if properly situated, a consistent view of

nature. This can be applied to the teachers and staff at Sayre, who desire to work in a school that is less industrial. Staff member Joe Brand pointed out that the Sayre building, due to years of underinvestment, can feel more like an “institution” than a school, with striking visuals of exposed pipes and peeling paint. He asserted that such an environment is not one in which students and teachers can feel emotionally safe; a situation which can lead to disputes, escalated situations, and other

manifestations of trauma in the neighborhood. Creating green spaces will lessen the institutional feel of the school, which can lead to higher overall job satisfaction and lower turnover.

Courtyards are key interior spaces of the school. Our design will create three distinct gardens for mental health and wellbeing, education and outdoor learning, and fostering social life. Though they serve different functions, the three spaces are unified through the expression of stormwater treatment and conveyance as an engaging experience. Stormwater processes are made visible through a series of connected channels, pavement treatment, and rain gardens, which call attention to the sights, sounds, and flows of water. Seating and tables within the courtyards will provide spaces for students to gather while being immersed in nature.

"Access to, or even a view of, nature can have a lasting positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction levels, wellbeing, and stress levels”

The plants and soils within the rain gardens have been chosen to balance the desires of the students and staff at Sayre with functional stormwater retention and infiltration. Rain gardens are designed to allow water to infiltrate through the ground before running off into the storm drains. They are a powerful solution to offset stormwater and concurrently have the benefits

into the parking lot space with the primary goals of decreasing stormwater runoff, addressing the urban heat island effect, improving walkability, creating a community corridor, and overall campus beautification.

of reintroducing nature to urban spaces. The benefits for the school would include a beautiful learning environment, an area to relax and unwind, or an area to chat with friends during lunch time. In addition to stormwater, rain gardens are able to alleviate the urban heat island effect which Sayre currently experiences.

DESIGN SOLUTION: PARKING LOT

When looking at Sayre High School from an aerial view, one immediately notices the vast parking lot space; it is a concrete desert. For this reason, our second focus area when looking at design solutions is the parking lot. Sayre’s parking lot slopes down with stormwater flowing directly in the direction of the street. The parking lot makes up 35,424 sq ft of the school site, making it a suitable area to incorporate GSI while beautifying the space. Our design focuses on incorporating tree trenches and permeable pavement

Bioswales are vegetated ditches that collect and filter stormwater. As the stormwater runs through the bioswale, the pollutants are captured in the stems and leaves of the plants. In addition to reducing stormwater and pollutants, bioswales also recharge groundwater.8 Finally, and most importantly for the needs of Sayre High School, bioswales combat the urban heat island effect by cooling the surrounding environment. With Sayre being in one of the hottest areas in Philadelphia, the inclusion of bioswales in our design solutions directly addresses this problem. Further addressing this issue is the inclusion of permeable paving in the parking lot space.

DESIGN SOLUTIONS: EDUCATIONAL SIGNAGE AND CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

A final element of the design incorporates both educational signage and the inclusion of environmental justice topics within the school’s everyday curricula. To improve students’ engagement with GSI and to enhance their understanding of environmental justice issues at Sayre, the project will work with students to create sitespecific educational signage as well as the development and implementation of both watershed-focused and nutritionoriented curricula.

Additional References:

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Benefits of green infrastructure.

United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Lower Darby Creek Area Site Profile [Overviews and Factsheets].

Accessed December 1, 2021 https://cumulis. epa.gov/supercpad/ CurSites/srchsites.cfm

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Protecting Water Quality From Urban Runoff. (2003, February).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Green Roofs. In: Reducing urban heat islands: Compendium of strategies. (2008).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Heat Island Impacts [Overviews and Factsheets]. (2014, June 17).

"In addition to stormwater, rain gardens are able to alleviate the urban heat island effect which Sayre currently experiences.”

CONCLUSION

Sayre’s GSI design will not only manage stormwater, but will provide a multitude of social, environmental, and economic cobenefits for students, staff, and the surrounding community. To increase community ownership of the design and to determine what matters most to the Sayre community, our team is working towards an equitable and inclusive outreach and design process. To ensure that the design is actually implementable, Penn students

have conducted exhaustive analyses of existing conditions, design feasibility, and project performance; identified a wide swath of funding opportunities for which the design is eligible; and have formed partnerships with a diverse range of stakeholders. The GSI project that will be collaboratively designed with the Sayre community will, once implemented, serve to create a more resilient, equitable, and healthy Sayre High School.

Below: Rendering of greenhouse farm stand and community promenade.

Below: Rendering of greenhouse farm stand and community promenade.

Property & Protest

Property Damage in Minneapolis after the Murder of George Floyd

INTRODUCTION

By Charlie TownsleyThe cover image of this piece shows Minneapolis during the uprising that followed the murder of George Floyd by members of the city’s police department on May 25th, 2020. Protests against police brutality swept across the city, before being echoed across the world, and numbered well into the thousands.1 This period also saw the largest deployment of national guard troops in the state’s history, significant property damage, and an outpour of mutual aid.2

While living in Minneapolis in 2020, I became involved with a project through the Twin Cities chapter of the Architecture Lobby to map property damage that occurred during the protests.3 Our goal was to better understand how these protests manifested in urban space. Our guiding questions centered around the theme of people claiming power in space.

Above: Looting of the Target on Lake Street during the first days of the protests was a striking symbol of a public claiming power over commercial civic space. Source: Nathan Anderson Photography, Flickr CreativeCommons• Why did protests with the greatest intensity, which some called riots, occur in certain parts of our city?

• Were these spatial patterns reactions against a history of “colonists and capitalists appropriating the land of the indigenous and indigent?”4

• Which areas received the most damage?

• We noticed that many damaged properties appeared to be shops along commercial corridors. Was there actually a strong correlation between commercial properties and damage?

• Did protestors target public space as “the battlefield on which the conflicting interests of the rich and poor are set,” as Springer argues protestors have done across time and place?5

To answer these questions, our group worked with a dataset of damaged properties published by the city of Minneapolis, which included addresses of damaged properties as well as the types of damage they received during the four-day period, between May 25th and May 29th, when protests were at their peak intensity. We added property owner and primary taxpayer information to this dataset, after which we began to run into the confines of our limited access to, and knowledge of, GIS mapping software. We decided to put the project on hold in the fall of 2020.

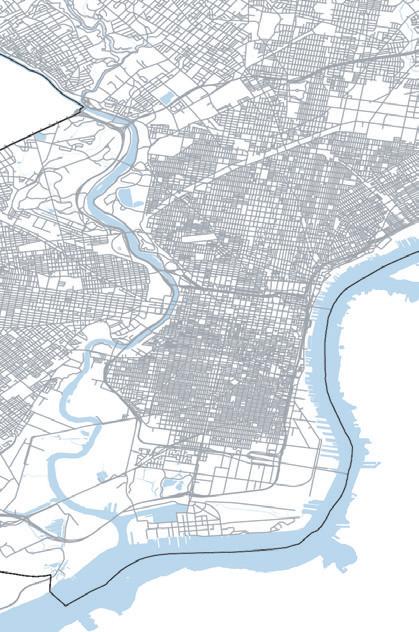

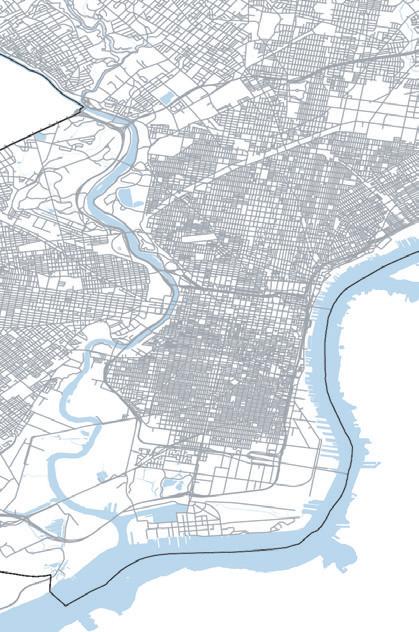

The following essay details my explorations, with data initially collected with the Architecture Lobby, layered with demographic information from the US Census Bureau, and property information from open data portals of the city of Minneapolis and Hennepin County, Minnesota.6 It begins by mapping property damage from the protests in relation to significant features from that time, specifically, sites of protest, police stations, and commercial corridors. It then studies these locations in juxtaposition with visualizations of race and income. Finally, it compares property damage to land use and property value.

My goal for this piece is to understand how mass protests claim power by disrupting existing patterns of ownership and control in space and to shed light on areas for further study.

PROTESTS AND PROPERTY DAMAGE

I began by grounding my inquiry in the primary patterns of protest and property damage that I observed while living in Minneapolis during this period. I noticed that most protest damage occurred along commercial corridors, in particular on Lake Street, and at police stations which became flash points for the crowd’s concentrated anger. Mapping these factors bears out the narrative I heard at the time. Of the 1,182 damaged properties, 65% were along commercial corridors, 66% were within half a mile of a police station, and 50% were within half a mile of a protest site (see Map 1). The dataset of damaged properties contained ten different types of damage which I consolidated into four: “destroyed,” “severe,” “moderate,” and “minor.” “Destroyed” describes properties that were rendered completely uninhabitable.

were

a mile of

police station,

[1] Boone, Anna. “One Week in Minneapolis.” Star Tribune. June 3, 2020.

[2] Bakst, “Guard Mobilized Quickly, Adjusted on Fly for Floyd Unrest”; Hopfensperger, “Mutual Aid Groups Surge”; Boone, “One Week in Minneapolis.” MPR News, July 10, 2020.

[3] An architecture advocacy organization. See http:// architecture-lobby.org/ about/

[4] McDonagh and Griffin, “Occupy! Historical Geographies of Property, Protest and the Commons, 1500–1850,” 1. Journal of Historical Geography 53. July 1, 2016. 1–10.

“Severe” includes significant fire and property destruction. “Moderate” consists of lesser fire damage, looting, and damage that required repair but did not make the building uninhabitable. Finally, “minor” damage includes cosmetic damage such as graffiti and slight vandalism to building elements or grounds.7

Diving into these correlations further, I found that 88% of “moderately damaged” properties were along commercial corridors, 81% of “destroyed” properties were within half a mile of a protest site, and 85% of “moderately damaged” properties were within

half a mile of a police station. A noteworthy outlier is the West Broadway commercial corridor in North Minneapolis, which was not the site of a police station or mass protests, but still experienced significant property damage. Interestingly, the weakest correlation was between “minor property damage” and proximity to protest sites. Just 44% of parcels with “minor damage” fell in this category. Overall, just 16% of all damaged properties did not match the above criteria, meaning they were not on a commercial corridor, and they were not within half a mile of a protest site or police station. Therefore, it appears

Map 1: Locations of damaged properties in Minneapolis from May 24 to May 29, 2020. It draws attention to police stations which served as anchors for many protests, and the clustering of property damage along commercial corridors near protest sites.17

“Of the 1,182 damaged properties, 65% were along commercial corridors, 66%

within half

a

and 50% were within half a mile of a protest site”

[5] Springer, Simon. “Public Space as Emancipation: Meditations on Anarchism, Radical Democracy, Neoliberalism and Violence.” Antipode 43, no. 2 (2011): 525–62.

[6] The portal for Minneapolis is at opendata.minneapolismn. gov. The portal for Hennepin County is at gis-hennepin.opendata. arcgis.com.

[7] Specifically, I merged the labels “destroyed” and “destroyed by fire” into “destroyed.”

The labels “severe fire damage” and “severe property damage” I merged into “severe.” I put “fire,” “looting,” “medium property damage,” “property damage,” and “fire damage” under “moderate.” Finally, “minor property damage” became “minor.”

that most damage did not occur in residential areas.

Scholarship on protest geographies supports these findings. Salmenkari argues that the majority of demonstration sites fall into the same categories, “outside governmental buildings to communicate with the authorities; at centers of commercial activity to appeal to the public; to places that link them historically, culturally or morally with symbolically important events; or at places connected with a particular grievance.”8 Police stations, commercial corridors, and the various locations of the protests I mapped all fall into these categories.

Minneapolis’ BIPOC population showed a moderate correlation between property damage and areas with greater numbers of BIPOC citizens. Roughly 40% of all damaged properties were in census tracts where more than half of their population identified as BIPOC. 10 Even though this correlation was quantitatively not as strong as others, of note is West Broadway, one of two commercial corridors in Minneapolis that experienced the most significant property damage and lies in the largest majority BIPOC area of the city (see Map 2). North Minneapolis, as the surrounding area is known, is a significant home to the city’s Black community.

SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS

Preliminary analysis of socioeconomic factors in relation to damaged properties suggests these may be fertile areas for future study in Minneapolis. I chose to compare property damage with the city’s concentration of residents who identify as Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC) and household income (see Box 2). I selected these factors based on a collective sense that emerged after George Floyd’s murder that the protests and subsequent property damage were “a challenge to the continued marginalization of Black, Indigenous, and other spaces of color through disinvestment and neglect by the state.”9 Mapping the spatial concentration of

Similarly, a study of riots in Los Angeles during the 1960s found a significant correlation between the locations of riots and the size of local Black populations. 11 The lack of a strong correlation between BIPOC population and protest damage in Minneapolis suggests that comparing damage to populations of specific races may have yielded different results.

Similar to mapping BIPOC population concentration, mapping household income (Map 3) did not show a significant positive correlation between the location of damaged properties and areas with the lowest income. However, there was a significant negative correlation between high income areas and property damage. Just 5% of all damaged properties were in census tracts that were in the top

[8] Salmenkari, Taru. “Geography of Protest: Places of Demonstration in Buenos Aires and Seoul.” Urban Geography 30, no. 3. April 1, 2009. 239–60. 1.

[9] Smiles, Deondre. “George Floyd, Minneapolis, and Spaces of Hope and Liberation.” Dialogues in Human Geography 11, no. 2. July 1, 2021. 167.

[10] Equity

Considerations for Place-Based Advocacy and Decisions in the Twin Cities Region.” Dataset. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Geospatial Commons, 2019.

[11] Case Study Inquiry into the Spatial Pattern of Four Los Angeles Riot Event-Types12.” Social Problems 19, no. 3. January 1, 1972. 408–26.

“88% “moderately damaged” properties were along commercial corridors and 81% “destroyed” properties were within half a mile of a protest site.”

[13]

25% of median household income.12 These tracts, where the average household income was over $82,400 per year, contained zero “destroyed properties”, 17% of “severely damaged” properties, only 1% of “moderately damaged” properties and 6% of properties with “minor damage.”13 The authors of the Los Angeles study found areas with high unemployment rather than income to be most correlated with sites of looting.14 Although this piece does not examine unemployment, their paper suggests it might be an equally telling metric for future studies of property and protest in Minneapolis. It is interesting to note that Map

3 shows Lake Street, where much of the most intensive property damage occurred, as sitting at a border between the bottom and bottom middle quantiles of household income. This brings into question whether contested class boundaries could have influenced the locations of property damage. Together, maps 2 and 3 suggest that areas of marginalization within Minneapolis loosely correlated with sites of protest. This pattern agrees with scholarship that links “urban riots” with “disadvantaged residential areas.”15

“Roughly 40% of all damaged properties were in census tracts where more than half of their population identified as BIPOC.”

Property Damage

Severe Damage

Moderate Damage

Features

Police Stations

Protest Sites