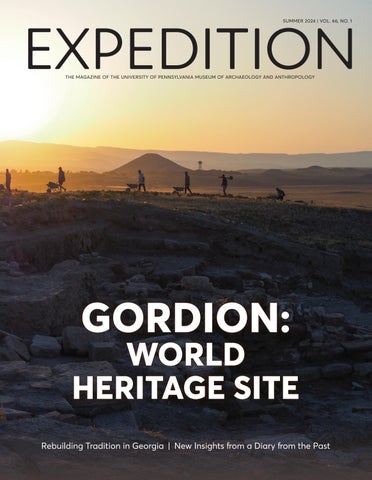

GORDION: WORLD HERITAGE SITE

Kate Pourshariati and Alessandro Pezzati

Manana Tevzadze

By C. Brian Rose and Gareth Darbyshire

Johann Begel, Carl Callaway, and Peter Mathews

Penn Museum respectfully acknowledges that

Above: Cotton and silver Lenape woman’s decorated blouse; one of four Lenape objects selected for the new Native North America Gallery and treated by an Indigenous community conservation fellow thanks to a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project (see page 52).

On the Cover: The excavation of Gordion’s South Citadel Gate in June 2024, with the Midas Mound Tumulus in the background; photo by Gebhard Bieg.

The People are the Stories

As someone who comes to work every day at the Penn Museum, it can feel like our permanent galleries and special exhibitions are my coworkers. I know what they look like and where I can find them, and I know there is always more to learn about them each time I walk by.

What I can’t anticipate from one day to the next are the people who visit the Museum. Class trips and family vacations. History buffs and art lovers. Renowned scholars and international authors. As these people walk through our Museum, they don’t just look at the objects in front of them—they look at one another, and they talk about what they’re seeing. These conversations are the soundtrack of our Museum.

In a staff-only hallway behind the Rome Gallery, there are two rooms that remain relatively quiet: the Tikal Archives. These rooms hold troves of documents from one of Guatemala’s most important Maya sites, which the Museum excavated in the 1950s and ’60s. One day last fall, I noticed a group of seven people sitting inside the Tikal archives. A smiling man named Alejandro Puga greeted me: “This is my family. We are from Tikal, and our grandfather worked with the Penn Museum for many years.”

For Alejandro, the Museum showed his family another side of their homeland (p. 4). He spent the day reading letters his grandfather had written to Museum archaeologists, and his relatives selected dozens of photos to be scanned by the Penn Museum Archives. In Guatemala, Alejandro's family operates a hotel inside the remote rainforests of Tikal National Park. This allows tourists to visit a tough-to-access UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Meanwhile, I recently spoke with two researchers from Mexico who came to the Museum on the final stop of a global research tour. They were studying codices made by their ancestors in the Mixtec region of southern Mexico. Only a handful of these codices still exist, and the Mexican Consulate organized a visit for the researchers to see one at the Penn Museum, which we'll share more about in the next issue of Expedition. When I asked why it was important to see the codex in person, researcher Omar Aguilar Sánchez told me: “When I look at the codices, it’s more than just academic, scientific, or artistic—it is for my own life and my own culture. When I see them inperson, it is very powerful for me. It feeds my soul.”

Whether you visit us in Philadelphia to see our galleries up-close, or you read the stories in Expedition and on our new blog Penn Museum Voices (pennmuseum.org/blog), we hope the Museum can spark conversations between you and the people in your life—and help you see how your own story fits into the larger history of humankind.

QUINN RUSSELL BROWN, EDITOR

EDITOR

Quinn Russell Brown

PUBLISHER

Amanda Mitchell-Boyask

ARCHIVES AND IMAGE EDITOR

Alessandro Pezzati

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Colleen Connolly

Christina Jones

COPY EDITOR

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Richard Leventhal, Ph.D.

Simon Martin, Ph.D.

Kathleen Morrison, Ph.D.

Lauren Ristvet, Ph.D.

C. Brian Rose, Ph.D.

Page Selinsky, Ph.D.

Stephen J. Tinney, Ph.D.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, Ph.D.

Lucy Fowler Williams, Ph.D.

CONTRIBUTORS

Jessica Bicknell

Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D.

Jennifer Brehm

Kris Forrest

Sarah Linn, Ph.D.

Anne Tiballi, Ph.D.

Jo Tiongson-Perez

PHOTOGRAPHY

Jennifer Chiappardi

Colleen Connolly

Francine Sarin (unless noted otherwise)

INSTITUTIONAL OUTREACH MANAGER

Thomas Delfi

© The Penn Museum, 2024 Expedition® (ISSN 0014-4738) is published three times a year by the Penn Museum. Editorial inquiries should be addressed to expedition@pennmuseum.org. Inquiries regarding delivery of Expedition should be directed to membership@pennmuseum. org. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Penn Museum.

Community Collaborations

Dear Friends,

When I wrote to you in the Fall 2023 Expedition, we had just heard that Gordion, where the Penn Museum has worked with local and heritage communities in Türkiye continuously since the 1950s, is a new UNESCO World Heritage Site—a testament to the research and cultural heritage work at this remarkable site over seven decades of fieldwork (page 14).

Cultural heritage is central to our new 2024–2027 Strategic Plan; our first goal is to centralize and build greater capacity and impact for the wide range of cultural heritage endeavors at the Museum and Penn, working with the Penn Cultural Heritage Center (PennCHC). In line with the PennCHC’s mission, researchers work in collaboration with communities to keep alive traditional cultural practices at risk around the work. In Georgia, where those displaced from the Tskhinvali region have struggled to maintain their ancestral traditions after war (page 10), PennCHC researchers are offering resources to preserve and celebrate these traditions.

Our Strategic Plan was developed within Penn’s strategic framework In Principle and Practice, and our goals aligned under the practices it defines, in particular to lead on great challenges of our time. For museums, a leading challenge is confronting the legacies of our collections. By dedicating more resources to provenance and repatriation, our Museum has begun this work. Two new staff who joined our NAGPRA Office this year are working with longstanding colleagues to respond quickly to repatriation claims in line with new regulations around the implementation of NAGPRA effective January 2024, and in May we were pleased to convene our peers across regional museums for a conversation with Melanie O’Brien, Program Manager for National NAGPRA. In our Biological Anthropology Section, a new collections manager and new registrar are doing important inventory and provenance work. Community collaborations are key in all aspects of our work. In our own Philadelphia community, we are grateful to the deeply engaged members of our Penn Museum Community Advisory Group, inaugurated just 18 months ago. They guided our early repatriation work around the Morton Collection and have already transformed our community engagement programs, working in partnership

with our new Community Engagement Department led by Chief Diversity Officer Tia Jackson-Truitt.

Our recent Juneteenth celebration—in collaboration with Forum Philly—showed how deep community involvement can serve wider audiences and build new traditions of celebration around our collections—a core goal of our Strategic Plan. We were honored to have Mayor Parker and Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Education Mumin speak and are delighted that a great many attendees experienced the Museum for the first time. Working to serve first-time audiences will help our Museum do more to focus on issues of contemporary importance and the relevance of the stories our collections tell today.

I look forward to sharing the full Strategic Plan with you; in the meantime, I hope you enjoy this issue which—as always—tells stories that emerge from our research and our collections to transform understanding of our shared human story. Through the goals in the plan we seek to bring these stories to wider audiences—at Penn and around the world. Thank you for being with us on the journey!

CHRISTOPHER WOODS, PH.D. WILLIAMS DIRECTOR

Celebrating Juneteenth and One Philadelphia, United: (left to right) Chris Woods; Rev. Dr. Malcolm Byrd, Founding President, Forum Philly; Honorable Cherelle Parker, Mayor, City of Philadelphia; Dr. Tia Jackson-Truitt, Chief Diversity Officer; Dr. Khalid N. Mumin, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Education; photo by Eddy Marenco.

Tourists from Tikal

FOLLOWING A FAMILY TRADITION, THE ORTIZ FAMILY TRAVELED FROM GUATEMALA TO THE PENN MUSEUM ARCHIVES

WHEN INTERNATIONAL TOURISTS travel to the Maya site of Tikal, in a remote area of Guatemala, they are likely to stay at the Jungle Lodge Hotel and Hostel. It’s not easy running a hotel in a rainforest, but the Ortiz family has been hosting travelers for five decades. The Jungle Lodge was built by José Antonio Ortiz, a Guatemalan entrepreneur who

combined his passion for adventure and archaeology. Ortiz worked with the Penn Museum from the start of its excavation work at Tikal in 1956, providing crucial logistical support, project management, and local knowledge about an area full of Maya temples and palaces. While the Museum's Tikal Project wrapped up its active excavation phase in 1970,

The Ortiz family in front of the Penn Museum courtyard; photo courtesy Ortiz family.

Ortiz continued to promote the site and make visits possible for many thousands of visitors from around the world. The site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979.

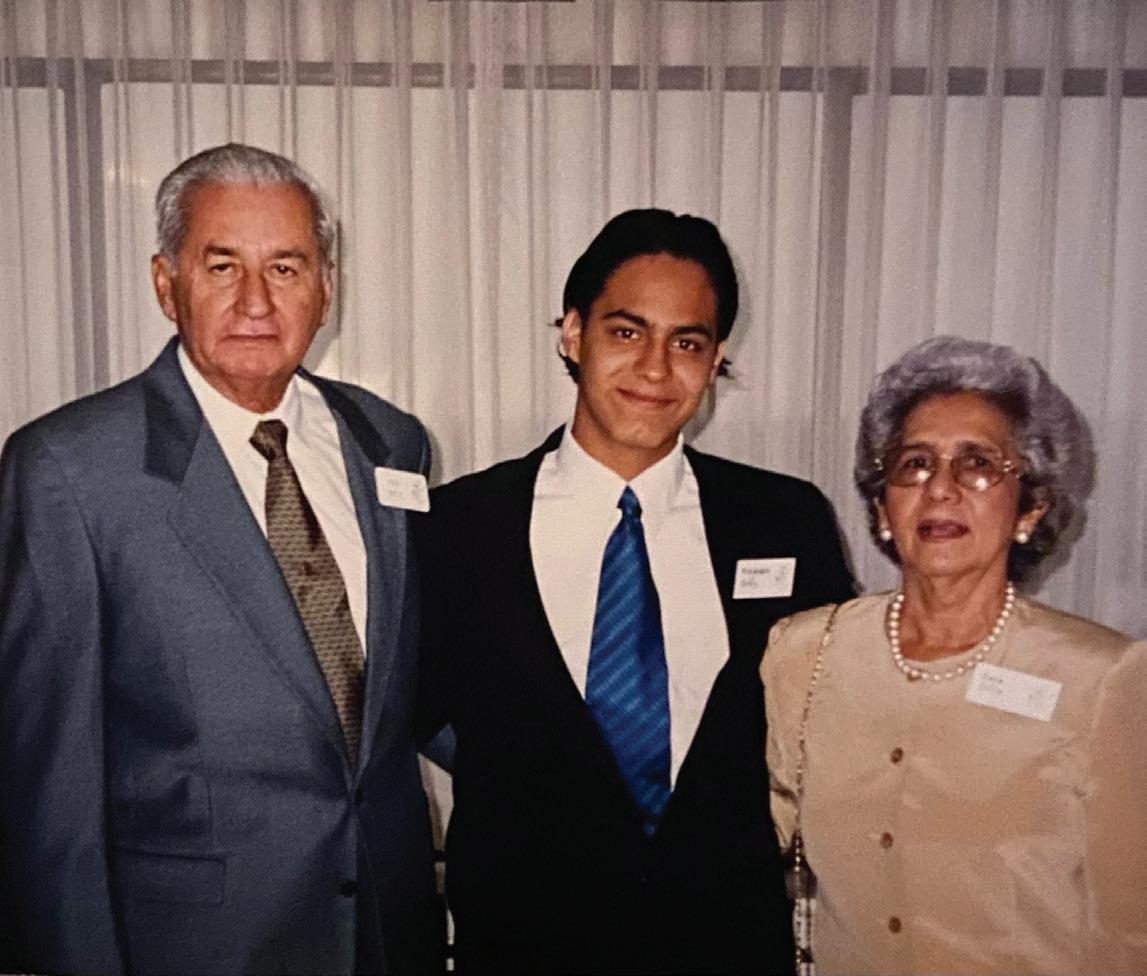

Ortiz came to the Penn Museum many times over the years, including in 1998 to accept an award for his many decades of service. His grandson, Alejandro Puga, came with him on that trip. This year Alejandro and six members of the Ortiz family came back to the Penn Museum to explore the Museum’s vast Tikal archives, reading handwritten letters by Antonio Ortiz and looking through photos of him over the years. Expedition talked with Alejandro Puga about the visit.

How did your grandfather, Antonio Ortiz, become involved with the Penn Museum?

Alejandro Puga: My grandfather lost his father when he was very little. He studied in Belize, where he learned English. He started working to extract the gum from the trees in Petén [region of Guatemala]. My grandfather was really smart, and he started making a lot of money very quickly. He bought horses and mules and contracted workers to help extract the gum. He had a contract to sell the gum to the Wrigley Company.

When the technology was developed to start making artificial gum, the people at Wrigley’s told him to move on from the business, since it would decline. My grandfather was a native Guatemalan who knew how to work the jungle, and he knew English, and he knew how to work with people. When the University of Pennsylvania came to do the Tikal Project, my grandfather was the perfect person. He knew the site, and he guided them in the jungle. He was the connection between the University and all the people involved at Tikal. He coordinated the people, the food, the rooms.

When the visitors started to come to Tikal, and it became famous, they needed a place to stay. My

Top: Antonio Ortiz visited the Penn Museum many times over the years, including to receive an award for his work on the Tikal Project in 1998. He is pictured with his wife, Aura Luz de Ortiz, and his grandson Alejandro Puga, interviewed in this story. Bottom: Temple I, one of the first buildings to receive attention in the program of preserving for the world the great architectural wonders of Tikal.

grandfather bought the place where the Jungle Lodge is. The Tikal Project lasted about 14 years, and there were a lot of scientists and archaeologists who my grandfather hosted. As the Tikal Project expanded, it was up to him to maintain everything and keep it in good condition. There was only an encampment at the time. In the ’60s and ’70s, he went to Penn’s campus several times.

Your grandfather also made a discovery. He discovered the Temple VI. The story goes that he was walking through the jungle, and he saw a big pyramid. He didn't know what it was, so he reported it. And the archaeologists didn’t have it in their records. It became known as the Temple VI, known as the Temple of the Inscriptions. (Editor’s note: This temple features a panel with one of the longest text inscriptions at the site of Tikal.)

And over time, the whole family became involved with the hotel?

In the 1990s my mother started managing the hotel. Then me and my brother and our cousins and our wives all got involved. We grew up with the Tikal Project and all of its stories and the jungle. We came to Penn in 1998, because they gave a recognition to my grandfather for all his support. We met with Christopher Jones and other archaeologists who worked in the Tikal Project. It opened a new dimension for us: We saw this other side of Tikal at the Museum.

Why did you come back to the Museum this time?

The first time we came to the Archives was in 2019. We wanted to learn more about the history of the project and to see all the letters my grandfather wrote to Penn and to the government of Guatemala. We wanted our wives to visit with us and take

The extended Ortiz family in front of Temple VI in Tikal National Park, known as the Temple of the Inscriptions and discovered by José Antonio Ortiz in 1951.

another look through the archive pictures and documents. We got very emotional when we were there. We have plans to expand the hotel. One of our ideas is to create a little museum in the hotel, so that people can learn the history of Tikal and the Tikal Project. We have to stay in touch. We have to work together. We have to send the Museum information and get information back.

Can you tell us more about the hotel?

The hotel is like a miracle. The environment of the jungle is very hard. To maintain the hotel at its best requires a lot of work. Every day is a challenge. We don’t have public electricity for lighting, so we have to create our own electricity. We have solar panels and machines to make energy.

Just last year, we got air conditioning in the suites. So, we are making little steps. We have some luxury rooms and we have also maintained the 12 original rooms where all the archaeologists stayed for the first time.

The Queen of Spain has stayed here. A lot of actors, musicians, and other famous people. My grandfather was a very visionary person. He could look into the future, and since he was 13 years old, he was connecting with people and working. He was negotiating the price of gum with Wrigley’s from a

young age. He asked the government for the permission to establish this hotel in the jungle, in the middle of nowhere. It was el mundo perdido—“the lost world.”

It is not easy to get to the Tikal National Park. It requires an adventure.

Tikal is far away. You have to take a plane from the big cities. The Jungle Lodge is an hour away from the nearest city. It’s mostly tourists who love culture. They come from all over the world: the United States, Italy, Germany, Spain. In the past few years, since the pandemic, a lot of Guatemalans have come, many of them for the first time. Others came when they were little.

Everybody here knows about Tikal. In school we learn about it. Our roots are linked to the Maya culture, and Tikal is the most important Maya city. Still, only a small percentage of families come to Tikal. The access is not that easy. But in a way, it helps that it’s not easy to get here—it helps keep that magical aura of Tikal.

To learn more about the Jungle Lodge Hotel and Hostel and the history of the Ortiz/Puga family, please visit www.junglelodgetikal.com.

The Ortiz family in front of the Jungle Lodge in Tikal.

Submarine Film Emerges

By Kate Pourshariati and Alessandro Pezzati

DURING A RECENT INVENTORY in the Penn Museum’s Photographic Archives, we discovered a few unprocessed cans of film, simply titled "Submarine", in scratchy writing on the masking tape that wrapped around the can. Curiosity, of course, was piqued. The film reels, or elements, were all uncut black-andwhite negatives. A careful glance at a few opening

frames seemed to reveal a submarine on the tiny 16-millimeter frames. We decided that the footage was worth digitizing, which would include inverting the footage to positive images.

We were delighted when the lab returned beautiful, probably never-before-used footage from 1964, including a sync sound interview with George F.

Still from the recently discovered film in the Museum's Photographic Archives showing George Bass off the coast of Bodrum with the submarine Asherah behind him.

Bass, a Penn-educated archaeologist and underwater diver who was the founding director of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology. There was also a good amount of B-roll (cutaways filmed to build a complete program). The footage was taken in and around shipwreck sites in the harbor of Bodrum, Türkiye. Film and sound were almost always recorded separately at that time, so we reunited the picture with the sound.

The Penn Museum once had a submarine as part of the pioneering underwater archaeology program instituted by Bass beginning in 1960. The submarine was named Asherah, after a Phoenician sea goddess. Made by General Dynamics in 1962 after specifications drawn up by Bass, it was the first non-military, human-operated submarine built in the United States.

The Asherah was used in Türkiye in 1964 and 1967, and was also chartered out to other research institutions, including the U.S. Navy. It was displayed in the pool in the upper courtyard of the Museum in 1967. The submarine’s visibility was poor, so it was sold in 1969 to a Texas oilman, and then changed hands several times, resurfacing around 2010 at the Merri-Mar Yacht Basin and Marina in Newburyport, Massachusetts, where it was painted yellow and put on display. It is now at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut.

Since the film elements were discovered, we have been able to trace the names of all the participants in the film thanks to Rebecca Ingram, the Archivist at the Institute of Nautical Archaeology. (The INA has been at Texas A&M University since 1976.) It is our understanding that most of the team has since passed away, other than Susan Womer Katzev, a young researcher at the time. Katzev was the only woman in the group, and can be seen at the beginning of the film. We hope to record an oral history with her to learn more about this exciting time.

FOR FURTHER READING

Rose, C.B. 2021. In His Own Words: George F. Bass and the Birth of Underwater Archaeology. Expedition 63(2): 8–13. Eiseman, C.J. 2014. Underwater Archaeology & George F. Bass. Expedition 56(2): 12–21.

WATCH A SHORT, EDITED VERSION OF THE SUBMARINE

In the village of Kekhvi in the occupied Didi Liakhvi Vally, Bezhan and Ilo Kakhniashvili continue their agricultural traditions in the Karaleti IDP settlement.

Rebuilding Traditions after War in Georgia

By Manana Tevzadze

IN AUGUST 2008, a war erupted in Georgia’s conflict-affected region of Tskhinvali, also referred to as South Ossetia. Fighting between the Georgian military and the South Ossetian proxy forces (under effective control of the Russian Federation) shattered the fragile peace in place since earlier confrontations in the 1990s. A second front opened in the contested region of Abkhazia, and Russia quickly recognized both regions as independent states.

Today, Russia continues to occupy around 20% of Georgia’s internationally recognized territory. Almost 300,000 Georgians have fled their homes and become internally displaced persons (IDPs) since the initial conflicts in the 1990s. In the Tskhinvali region, Russia’s forces destroyed almost all ethnically Georgian villages, with numerous reports of ethnic cleansing. Former residents of the region now live in IDP settlements across the country. Their cultural heritage has been significantly disrupted by prolonged conflict and occupation and threatened by the dispersal of the region’s residents. Since 2013, the Georgian National Committee of the Blue Shield (GNCBS), a chapter of Blue Shield International—the cultural heritage equivalent of the Red Cross—has worked to protect Georgia’s cultural heritage in the face of conflict and natural disaster. The GNCBS has long recognized the devastating effects of displacement on social and

cultural livelihoods. With the collaboration of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center (PennCHC), GNCBS recently expanded its programming and engagements to advocate for cultural heritage preservation among Georgian IDP communities. In September 2022, they jointly launched the project “Protection of the Cultural Heritage of the Occupied Regions” (Tskhinvali Region-PCHOR) with support from the U.S. Embassy in Georgia.

The Tskhinvali Region-PCHOR Project aims to empower Georgia’s IDP communities by promoting cultural resilience.

Researchers from the GNCBS work most closely with IDPs from the occupied Didi Liakhvi Valley who now reside in settlements throughout Georgia. The GNCBS and the PennCHC collaborate with local Georgian partners, including the Didi Liakhvi Valley Museum-Reserve and Historical and Cultural Heritage Preservation Center, as well as U.S. supporters like the Artistic Freedom Initiative. Together, they study Georgia’s at-risk heritage, promote collaboration between Georgian and U.S. heritage professionals, and increase the engagement of IDP youth with their local identity and culture.

To launch the project, the Tskhinvali RegionPCHOR team held focus group meetings and interviews with IDPs from the Didi Liakhvi Valley to learn about the cultural heritage of the Tskhinvali

A resident of Kekhvi continuing agricultural traditions in the Tserovani IDP settlement.

region. The focus groups concentrated on intangible cultural heritage practices, such as festivals, music, and cuisine. Due to Russia’s continued occupation of the region, former residents cannot access much of their tangible cultural heritage, such as culturally significant sites and important museum collections.

Along with documenting stories of traditional practices in the villages, the research team sought to understand how IDP communities have adapted their customs to fit new conditions in the IDP settlements, and how members of these communities are actively contributing to the preservation, transmission, and curation of their intangible heritage despite the continued conflict.

Findings from the focus group meetings shed light on the rich and distinctive culture of the Tskhinvali region. Participants vividly recounted memories from their villages and expressed a deep nostalgia for pre-conflict life. Attendees frequently told stories of the traditional holidays and festivals of the Liakhvi Valley. They reflected on the holiday of Geritoba, for example, which they observed for three consecutive Sundays in August in the village of Geri.

During this holiday, villagers would undertake a long pilgrimage transporting sacrificial sheep to the St. George Church. While villagers look back fondly on Geritoba, memories of the holiday are somewhat

bittersweet, as ethnic Georgians once celebrated the day peacefully together with ethnic Ossetians. After the initial 1990s conflict displaced ethnic Georgians from Geri, IDPs would make pilgrimages to the Geri Niche (“niche” means a special place to pray, akin to a shrine, in Georgian) in the village of Vanati instead of the St. George Church. The new occupation line set by the 2008 war barred ethnic Georgians from Vanati, as well. The once-beloved holiday of Geritoba has become emblematic of the devastation the Russo-Georgian conflict has wreaked on the social fabric of the region.

One focus group member from Kemerti recounted: “Even now when we gather around the table, we say grace to St. George of Geri and raise a toast to the church. We sometimes go to Arbo [a village close to where they are living in displacement] and light a candle there. Some families celebrate this day at home.”

Attendees eagerly shared memories of other village festivals. Tamarasheni locals recalled celebrating Mtskhetis Jvari in honor of the Jvari Monastery in Mtskheta, Georgia’s ancient capital. Kekhvians took pride in their village festival, Shvidmaisoba. People in the village of Charebi had huge celebrations for Barbaloba, in the name of St. Barbare. The list goes on and on.

Agricultural traditions constituted another vital element of life in the Didi Liakhvi Valley. Displaced people recollected the abundant orchards, vineyards, and mouth-watering fruits of the region, especially the Kekhura apple variety. Elderly interviewees long for the fertile soil of their homeland but also told researchers how they have planted vegetable gardens and fruit orchards in the small plots allocated to them in the settlements. One elderly focus group participant from Tamarasheni shared: “It was a desolate area, there was no shadow apart from that of you or the house, but we all managed to transform it into greenery and grow sufficient fruits and vegetables for my family. If I am told that I can return to my home tomorrow, I am ready to start everything from scratch again.”

Young residents of the Koda IDP settlement participating in a focus group meeting.

Memories from the Tskhinvali region are still alive, but the places where these celebrations and practices took place are no longer accessible. While some customs are still observed in the settlements, many traditions are bound to culturally significant sites and natural resources in the occupied territory and have lost their relevance in displacement. Elders wonder if they will ever see their homes again and fear that interest in the cultural heritage of their villages will fade among younger generations.

The focus group sessions offered hope for the future of cultural heritage preservation among the IDP communities. Some young community members attended the sessions and were awed by their elders’ spirited recollections of their native villages. They even expressed interest in reinstating some of the old traditions in the settlements.

The Tskhinvali Region-PCHOR team hopes that they will continue to stoke this interest among younger generations. In 2023, the team integrated their findings into educational material for IDP youth and conducted several lessons on cultural heritage for learners of various ages. More educational programs

are in development, as well as a pop-up exhibition about the intangible cultural heritage of Kekhvi, a village in the Didi Liakhvi Valley. The exhibition will make its rounds through multiple settlements where locals of the valley currently reside.

Moving forward, the Tskhinvali Region-PCHOR team and local partners seek to build networks of Georgian and international cultural heritage organizations to advance the field, support practitioners, and help Georgia’s IDP communities heal from their losses through cultural resilience-building. Together, the organizations hope to safeguard the traditions and living culture of the Tskhinvali region until they can flourish at home once again.

Manana Tevzadze is a cultural heritage preservation specialist with more than 15 years of experience working in Georgia’s heritage sector. She served as the Chair of the GNCBS for more than 10 years. She is a graduate of the World Heritage Studies program at the Brandenburg University of Technology. Manana is the Secretary of ICOMOS Georgia and a board member of ICOM Georgia.

Resident of Kekhvi village Nugzar Kakhniashvili keeping bees at his home in the Tserovani IDP settlement.

The road to Gordion’s Citadel Mound leads through a chain of over 100 royal burial mounds, the oldest in Asia Minor. One of these, the “Midas Mound” tumulus, was the first major construction project of King Midas in 740 BCE, and the wooden tomb chamber within it—the oldest standing wooden building in the World—is continually monitored by the Gordion excavation team. Photo by Gebhard Bieg.

Of Outstanding Value to Humanity

IN SEPTEMBER 2023, GORDION, TÜRKİYE, CAPITAL OF ANCIENT PHRYGIA, BECAME THE FIRST SITE TO BE DEEMED "OF OUTSTANDING VALUE TO HUMANITY" AND INSCRIBED ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST BY UNESCO WHILE UNDER ACTIVE EXCAVATION BY THE PENN MUSEUM.

By C. Brian Rose and Gareth Darbyshire

Penn at Gordion

IN 1950, THE PENN MUSEUM BEGAN EXCAVATING AT THE ANCIENT PHRYGIAN SITE OF GORDION IN WEST CENTRAL TÜRKİYE, APPROXIMATELY 65 MILES SOUTHWEST

OF ANKARA.

Led by Penn professor Rodney S. Young, the project has systematically revealed an imposing city that controlled the Phrygian kingdom, and it has been conducted under the auspices of the Penn Museum for nearly 75 years. Gordion has proven itself to be one of the most important excavation projects in the region, revealing evidence for habitation at the site that spans more than four millennia, from ca. 2400 BCE to 1400 CE. In the following pages of photographs and illustrations, we trace Gordion’s development as both an influential ancient city and a rich archaeological site.

Aerial view of Gordion in 1950, during the first season of the Penn excavations. The Citadel Mound is at lower left, and Tumulus MM (“Midas Mound”) at upper right.

Rodney S. Young was Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania and head of the Museum’s Mediterranean Section. A complex, charismatic, and dominating figure, he directed the Gordion excavations from 1950 until his untimely death in a car accident in Philadelphia in 1974.

From the Bronze Age to modern times, Gordion has occupied a strategic location on a long-distance trade route connecting the Middle East with the Mediterranean. As the royal capital of ancient Phrygia, Gordion had been a powerful and influential political and cultural hub, and consistently maintained cultural ties with the great civilizations to its west (Lydian, Macedonian, and Roman) and its east (Hittite, NeoHittite, Assyrian, Urartian, and Persian). It has also entered the public imagination as the land once ruled by the eighth century BCE King Midas, known for his “golden touch” (a legend that represents the great wealth of the region), as well as the place where Alexander the Great unsheathed his sword to cut the Gordian Knot (a moment that symbolized the Macedonian conquest of the Persian Empire).

A map of Anatolia with a reconstruction of the area influenced by Phrygian culture during the eighth century BCE; by G. Darbyshire, A. Anderson, and G. Pizzorno.

◀A selection of the many bronze vessels discovered inside Tumulus MM, believed to belong to Gordias, father of the fabled King Midas. Some of the vessels still retained the sediment from the funeral meal that was served in ca. 740 BCE. Analysis of the sediments by Dr. Patrick McGovern of the Penn Museum indicates that the feast consisted of a spicy meat stew with lentils, washed down with an alcoholic beverage that combined wine, beer, honey, and saffron; photo by Tom Stanley.

OF OUTSTANDING VALUE TO HUMANITY

The Hellenistic burial mound, Tumulus O (ca. 300 BCE, Macedonian period), was excavated in 1955. The stone tomb chamber, covered by an earthen mound, has two rooms, each with a distinctive corbelled roof that is paralleled in other dynastic burials from western Anatolia. Although the tomb had been robbed in antiquity, fragments of a terracotta sarcophagus were found.

Ancient Innovators

THE CITADEL MOUND CONTAINS NINE SETTLEMENT LAYERS THAT DOCUMENT NEARLY 4,000 YEARS OF LIFE AT GORDION. THE RESIDENTS WERE INNOVATORS IN ARCHITECTURE, CITY PLANNING, AND THE PRODUCTION OF TEXTILES, FURNITURE, MOSAICS, AND METALWORK.

Excavations have uncovered the oldest standing wooden building known in the world (Tumulus MM tomb chamber, ca. 740 BCE), the earliest decorated pebble mosaics ever found (ca. 825 BCE), and some of the best-preserved wooden furniture from antiquity (9th and 8th centuries BCE). Gordion has therefore become an exceptional type-site in for the archaeology of the region, demonstrating the major role that Phrygia played in cultural and economic exchange between the Mediterranean and the Middle East during the Iron Age.

An ivory plaque of a mounted Phrygian warrior, dated to the later ninth century BCE, discovered inside the monumental Megaron 3 building on the Citadel Mound.

The wooden tomb chamber inside Tumulus MM (ca. 740 BCE), during the excavations in 1957.

Three bronze cauldrons on iron stands (two pictured here), in situ along the south wall, are surrounded by several large bronze jugs and ornamental drinking bowls.

A World Heritage Site

AFTER A TWO-YEAR APPLICATION AND APPROVAL PROCESS, GORDION WAS INSCRIBED ON THE WORLD HERITAGE SITE LIST OVERSEEN BY THE UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC, AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION (UNESCO).

The application was jointly prepared by the Turkish government's Ministry of Culture and Tourism in tandem with the Gordion excavation team. When UNESCO's representatives visited the site to evaluate the application, the team escorted them to many of the tumuli (burial mounds) that surround the ancient city. Finally, they went to the Citadel Mound and presented a tour to a wider group of cultural heritage experts who formed part of the UNESCO team.

The UNESCO and ICOMOS team touring the Citadel Mound with excavation director Brian Rose. Photo by Zekeriya Utğu.

Tumulus MM (ca. 740 BCE), the burial mound where Penn Museum’s Rodney S. Young discovered the oldest standing wooden building in the world in 1957. The tomb is now considered to belong to the father of Midas, the Phrygian ruler Gordias, whose tomb featured over 100 bronze bowls and vessels, over 180 bronze clothing pins, and some of the most luxurious and best-preserved wooden furniture ever to have been found at an archaeological site. Photo by Gebhard Bieg.

The reception in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, following Gordion’s inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site List in September of 2023, with Penn Museum’s C. Brian Rose pictured second from right.

A Future for Gordion's Past

A recently completed architectural conservation program, seven years in duration, will ensure that it continues to stand for many more generations. The perimeter of the Citadel Mound is now equipped with information panels chronicling the 4,000-year occupation levels of the site, which are presented as well in a new guidebook. All of this information is shared with the youth of the region through Ayşe Salzmann’s Cultural Heritage Education Program, designed to guarantee a future for Gordion’s past.

Conservation work on the Early Phrygian citadel's East Gate (constructed ca. 850 BCE), in 2014; photo by Gebhard Bieg.

Since Rodney S. Young’s death, the Penn Museum’s work at Gordion was directed by four eminent scholars: Keith DeVries (1974-1987); G. Kenneth Sams and Mary Voigt (co-directors, 1988-2012); and current director C. Brian Rose (right). Dr. Rose came to Penn Museum after decades as a leading expert on the archaeology of ancient Troy, in northwestern Türkiye. He works closely with Gordion Project Archivist Gareth Darbyshire (left). Their excavations in Türkiye take place from June to August each summer. Photo by Gebhard Bieg.

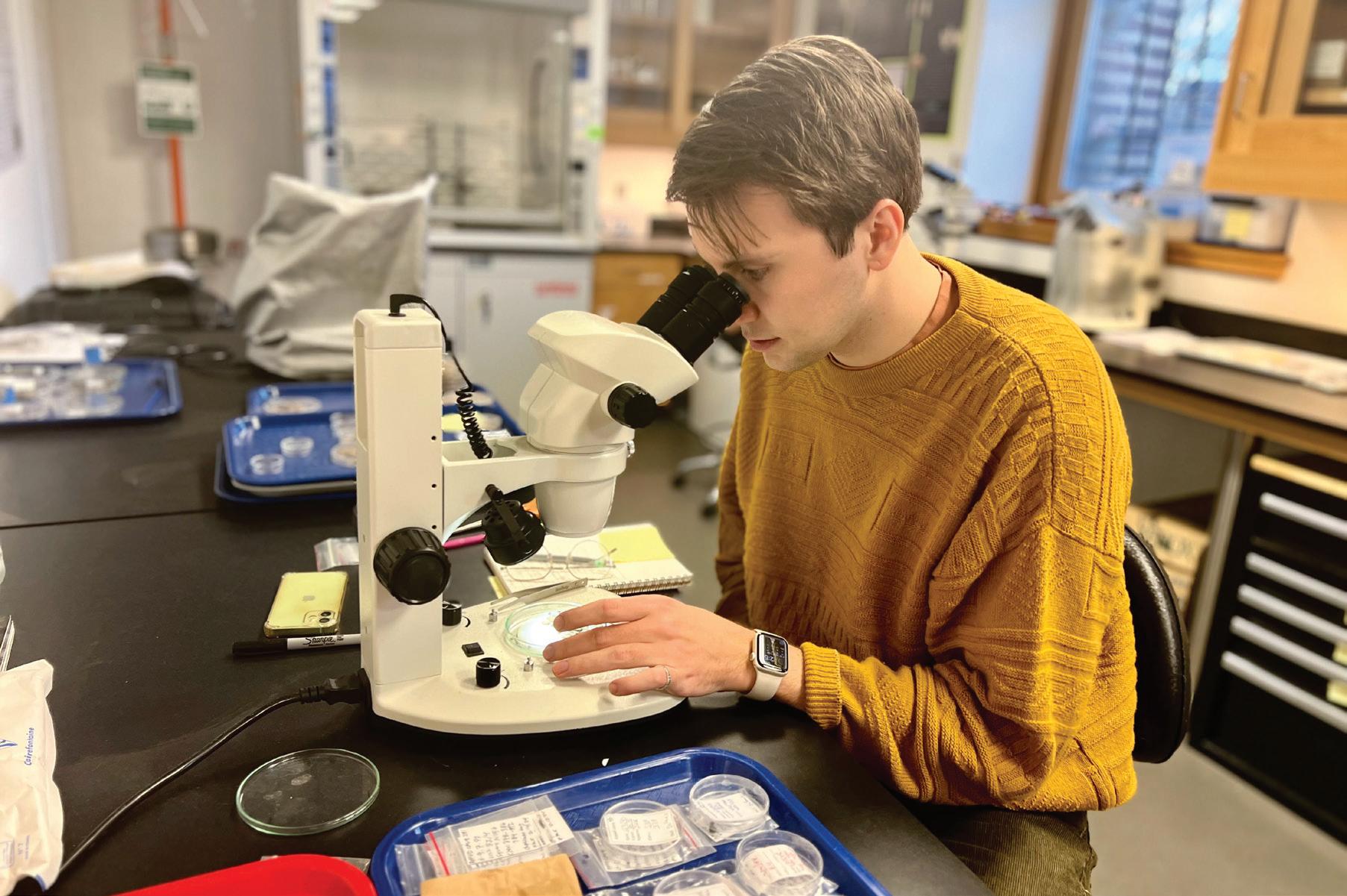

Students in the Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Program (CHEP) attend a lecture on faunal analysis at the dig house;

▲ Scan to read more about the Gordion Archaeological Project

C. Brian Rose is Ferry Curator-in-Charge, Mediterranean Section, and James B. Pritchard Professor of Archaeology. Gareth Darbyshire is the Gordion Project Archivist and a Research Associate at the Penn Museum.

photo by Brian Rose.

Ali Kurultay setting up the Faro laser scanner in the narrow confines between the roof of the tomb and the concrete retaining shell above; photo by Gebhard Bieg, Penn Museum Gordion Archives.

lasers in the tomb

Digitally Modeling the Tomb within the Midas Mound

BY MATTHEW HARPSTER AND MICHAEL BARNGROVER

We quickly learned three important

things after entering the tomb chamber in Tumulus MM, known as the Midas Mound at Gordion, Türkiye, and walking around the oldest standing wooden building in the world. First, it was cold. Outside it was a hot summer day on the Anatolian plateau in July 2021. Dogs and cars were settled at awkward angles in the shade of trees, and the heat made everything feel heavier. Inside the tomb structure, under a 53-meter pile of soil, it was about 15 degrees Celsius and dry. Clearly, the pants, sandals, and T-shirts we donned for a normal day of archaeology would not keep us warm for long. The second thing we learned was that we were out of our element. That year, two of us (Matthew Harpster and Günce Öçgüden) had specialized in maritime archaeology at Koç University in Istanbul, and the other one (Michael Barngrover) was a digital visualization expert typically working with Augmented and Virtual Reality (AR & VR). Nevertheless, with permission from the Ministry of Culture and

Tourism in the Republic of Türkiye and support from Professor C. Brian Rose, Director of the Gordion Archaeology Project (GAP), we were standing in this cold tomb. Our objective: To make a three-dimensional digital model of this ancient structure. We aimed to use this model in the prototype of an AR application we were building for underwater sites. Like a wreck site, the tomb was visually and geometrically complex, relatively inaccessible to the public, yet important to the rich history of Türkiye. It would be a valuable way to test the development platform we were building, and it would be a new way for visitors to understand the tomb.

The third thing we learned was the most important: We needed Richard Liebhart and his unique knowledge. Most scholarship about this structure, since its first investigation by Rodney Young in 1957, focused on who was buried inside and when. For decades, scholars proposed that this was the resting place of the legendary King Midas, buried in the late 8th century BCE. Following the 2010 reevaluations of dendrochronological and carbon-14 data, the consensus is now that the tomb was built by Midas for his father, Gordias. Our interest in the tomb was more prosaic, however, so we couldn’t engage those numerous experts and their proposals. As we tried to document this structure, we needed to know its history—how it was built, and what has happened to it in the centuries since. And, Richard Liebhart was the person who knew this best.

Liebhart arrived at Gordion in 1990 to begin this long-term investigation, near the beginning of a new period of research as G. Kenneth Sams began overseeing the GAP. In 1993, GAP hosted a specialized congress about the degradation, stabilization, and care of the wooden chamber, finally

Location of the ancient site of Gordion in modernday Türkiye. Map by Gareth Darbyshire, Ardeth Anderson, and Gabriel H. Pizzorno, Penn Museum Gordion Archives.

recognized as the oldest standing wooden tomb in the world. Soon afterwards, Stephen Koob installed monitors on the chamber’s timbers to record structural changes, and Robert Blanchette and Timothy Filley’s team was modeling the impact of the soft-rot fungi evident in the exposed logs. By the end of the decade, more dendrochronological samples had been taken, and the wooden struts once supporting the chamber’s outer walls were replaced by a custom steel armature by Conor Power and Ural Engineering, of Ankara. In a way, then, Liebhart was deciphering the phases of the building’s construction as other scholars were determining how it may be falling down.

For us in 2021, however, we were struck by the difference between reading about this structure and the challenges of encountering it in person. Some challenges were technical, because the tomb presents a range of issues for digital documentation while other challenges are very much atypical. This is why it was attractive to us to combine laser scanning and photogrammetry methods in this project—both methods have strengths that balance the other’s weaknesses. So, in addition to our use of digital cameras, we were lucky to work with a Faro Focus laser-scanning device in both years, which performed well in the relatively low-light conditions of the tomb.

Laser scanning works by casting an extremely high number of infrared laser rays, one at a time, which reflect off surfaces, such as stone or wood, in the surrounding environment. These devices utilize one of two methods for measuring the distance to these surfaces. The first is the Time-of-Flight

method, which measures the time it takes for the light to bounce back. The second is the Phase-Based method, which is the displacement in the light’s waveform when it returns. Time-of-Flight is best for measuring long distances, while Phase-Based is best suited for complex surfaces within a limited range. Thus, for our needs in the narrow and tight confines of the tomb, the Phase-Based method was the most appropriate because of its superior precision. This was especially true in 2022, when we undertook to scan the roof of the wooden tomb structure, where we

Richard Liebhart (on ladder), Ali Kurultay, and Michael Barngrover erecting a temporary platform to scan the south gable of the tomb chamber; photo by Gebhard Bieg, Penn Museum Gordion Archive.

Günce Öçgüden recording the interior of the chamber in 2021; photo courtesy of Matthew Harpster.

faced a restricted working space between the wooden roof and the cement ceiling of the surrounding superstructure.

Photogrammetry works differently than laser scanning. By analyzing many high-resolution photographs taken from slightly different angles and positions, photogrammetry identifies common features between them. By analyzing the changes in relational orientation of features across multiple photographs, a topography representing the surfaces of objects and environments can be generated. Comparing the two methods, photogrammetry is susceptible to greater error rates on account of its sensitivity to light conditions and indirect measurement of surfaces. However, photogrammetry offers an advantage over laser scanning because it is capable of capturing even greater visual detail. Whereas laser scanning captures points in space, photogrammetry captures surfaces, or the space between points. A handheld camera, or even a mobile phone, is also much more maneuverable when trying to capture narrow or hard-to-reach areas.

we touch it? How fragile was it? And, what happens if we’re locked in for the night? By the end of our 2021 season, we had systematically scanned the interior and exterior walls of the structure, but key issues remained. First, we had good data, but we didn’t know how useful it was for Liebhart’s needs. Second, we had only documented the easy parts. We needed to return in 2022.

The other major challenge in 2021 was Liebhart’s absence. As he quarantined in the United States, we found lights, ladders, and extension cords among his tools hidden behind the chamber, and we encountered no problems operating the laser scanner to document the structure. But we were unsure about the structure itself. Without Liebhart, this tomb chamber was a mystery and, in the cramped working spaces around its edges, it was intimidating, too. It felt much larger than the dimensions we had read. Could

Our team changed slightly in the following year. Günce Öçgüden remained in Istanbul to finish writing her M.A. thesis, but we were joined by Ali Kurultay, a preservation architect specializing in the documentation of historic structures. We also had Liebhart now. His presence answered many of our questions. With his guidance, we documented the roof of the building while maneuvering around pine timbers over 2,000 years old and climbed the surrounding concrete rafters and steel girders to scan the gables, corners, and details barely visible from the floor. Our photogrammetry efforts were particularly useful in 2022 when we focused our efforts on scanning an inscription on one of the exterior structure’s immense juniper logs. The inscription was discovered in 2007 and is visible by means of a cutaway portion of an adjacent log. Unfortunately, while the inscription is near the public viewing area and of great significance, it is not easily seen. It was not possible to position the Faro Focus ideally on the exposed space around the inscription, or to angle it toward the inscription on an elevated platform. Moreover, Günce had done M.A. research documenting early-modern ship graffiti carved into the walls of a mosque that suggested that this particular scanning device would not yield ideal results with such shallow and delicate

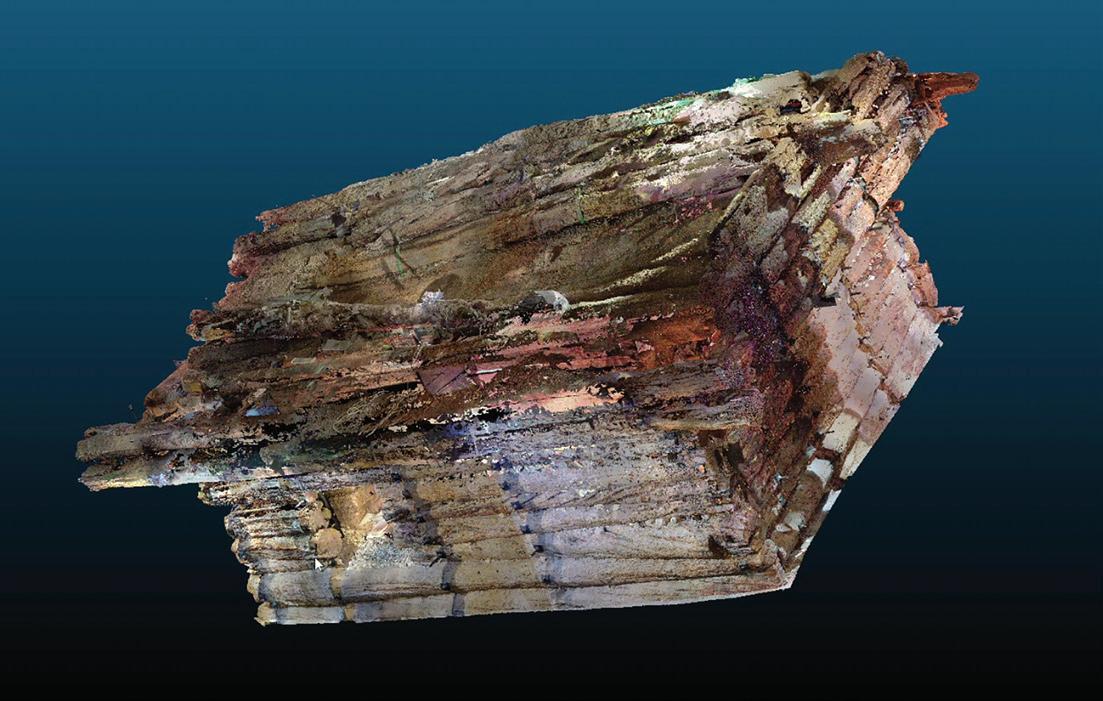

Axonometric view of an incomplete point cloud model of the tomb chamber; model by Michael Barngrover and Ali Kurultay.

Ali Kurultay (on ladder), Michael Barngrover, and Matthew Harpster trying to position the laser scanner to record the inscription; photo by Gebhard Bieg, Penn Museum Gordion Archive.

topographic detail. While there exist laser-scanning devices better suited for this specific use case, photogrammetry proved to be the more practical method for documenting this important feature given the resources available on site. Photogrammetry was also used to document other minute and interesting topographic details, such as the trails beetles bored into the logs thousands of years ago.

After two complete seasons in the tomb, laser scanning is finished, and we have a complete and detailed scan of the wooden tomb’s interior and external structures as well as the surrounding concrete superstructure. Photogrammetric work on the features we prioritized is also finished; additional work is still possible but depends on new and optimized lighting solutions within the tomb’s highly sensitive electrical and thermal environment. This digital model is presently the most accurate record of the tomb structure and will greatly aid future conservation, management, and public outreach efforts. Ultimately, our plan is to combine the results of the laser-scanning and photogrammetry data to create a set of visualizations that can provide value for as many stakeholders as possible. While a seemingly straightforward goal, we also know that difficulties can easily arise over the medium and long term. For example, experience suggests that simply digitally documenting and archiving scanned assets is not sufficient to ensure that the visualizations meaningfully contribute value within multiple sectors. In fact, without identifying which stakeholders would benefit from these digital visualizations, and clear input from stakeholders and medium and long-term planning, the assets can become obsolete and inaccessible. Without clear utility, the risk is that these scanned assets will be deemed impractical to work with. Moreover, as more time passes, the risk of

software updates and obsolescence that the project can only partially hedge against increases.

This potential obstacle means that the medium and long-term planning for the project outputs is as important as the scanning itself. For example, viewing and working with the tomb’s raw scanned assets is demanding on computing power and memory, and requires users to possess the right tools. Few stakeholders, whether they be students or

researchers, are likely to possess easy access to such tools, meaning that the project will engage with key individuals to understand which tools are necessary to utilize these digital assets. The ability to use these assets will allow stakeholders to anticipate and undertake the additional steps needed to turn the raw scanning data into many activities such as

The documentation team in 2022, from left to right: Ali Kurultay, Michael Barngrover, Matthew Harpster, and Richard Liebhart; photo by Gebhard Bieg, Penn Museum Gordion Archive.

“After two complete seasons in the tomb, laser scanning is finished”

digital exhibitions, research, and archiving. We foresee a variety of valuable applications in the coming years. For example, because the model represents a record for the current state of the structure, subsequent digital and analog documentation can assess if and how much the walls may be shifting or buckling. The very restricted access to the tomb, however, also means that this model is a viable alternative for educational efforts

for users inside and outside the academic environment. We are creating a digital guide to the tomb that integrates photos from its discovery in 1957, audio guides to particular details, and superimposed text for features, so visitors can engage with a variety of content to enhance their visit to the tomb itself.

Matthew Harpster is the Director of the Koç University Mustafa V. Koç Maritime Archaeology Research Center, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art at Koç University, Istanbul. Michael Barngrover is a freelance XR developer focused on areas of cultural heritage and photogrammetry. He has documented tangible heritage around the world and has taught methods to students and researchers in the field. He is the Managing Director of XR4Europe, the pan-European association supporting academicians, entrepreneurs, and creatives using immersive technologies.

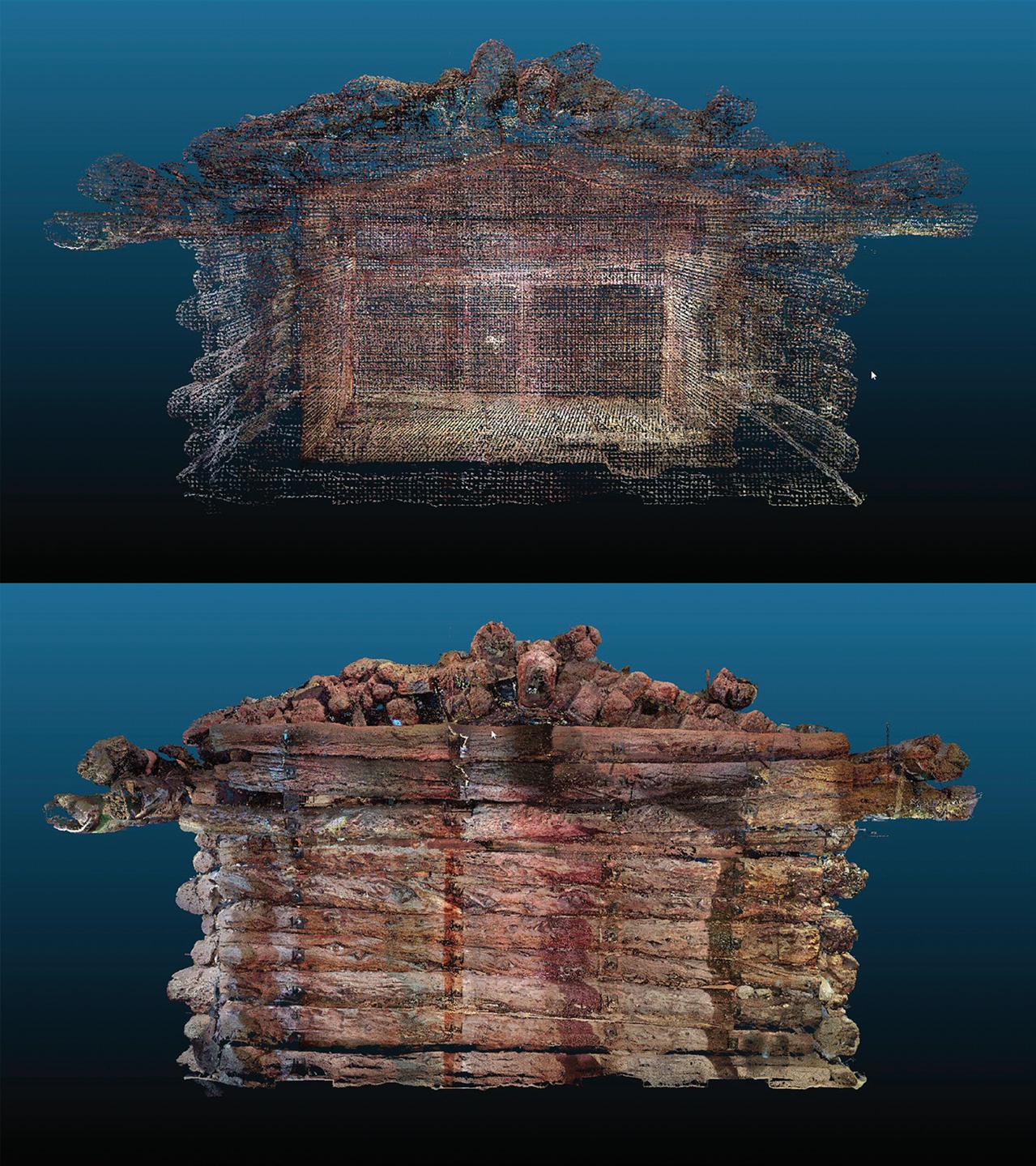

Two views of the point cloud model of the north end of the tomb structure. The density of the point cloud representing the external walls of the structure is reduced in the top image, revealing details of the interior chamber; models by Michael Barngrover and Ali Kurultay.

FOR FURTHER READING

DeVries, K. 2000. Gordion. Expedition 42(1):18–20. Filley, T., R. Blanchette, E. Simpson, and M. Fogel. 2001. Nitrogen Cycling by Wood Decomposing Soft-Rot Fungi in the King Midas Tomb. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98:13346–50.

Kohler, E., and E. Ralph. 1961. C-14 Dates for Sites in the Mediterranean Area. American Journal of Archaeology 65:357–67.

Kuniholm, P., and M. Newton. 2011.

Dendrochronology at Gordion. In Gordion Special Studies VI: The New Chronology of Iron Age Gordion, ed. C.B. Rose and G. Darbyshire, 79–122. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Liebhart, R., and J. Johnson. 2005. Support and Conserve: Conservation and Environmental Monitoring of the Tomb Chamber of Tumulus MM. In The Archaeology of Midas and the Phrygians, Recent Work at Gordion, ed. L. Kealhofer, 191–203. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Liebhart, R., and L. Stephens. 2015. Tumulus MM, Fit for a King. Expedition 57(3):3–41.

Ralph, E.K. 1981. IV. 14C. Review of 14C Dates for Tumuli MM and W brought up to date with the MASCA Correction Factors. In The Gordion Excavations Final Reports, Volume I. Three Great

Early Tumuli, ed. R. Young and E. Kohler, 293. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Simpson, E. 1988. The Phrygian Artistic Intellect. Source: Notes in the History of Art 7:24–42. Simpson, E. 1990. Midas’ Bed and a Royal Phrygian Funeral. Journal of Field Archaeology 17:69–87. Simpson, E., and R. Payton, 1986. Royal Wooden Furniture from Gordion. Archaeology 39:40–47. Young, Rodney S. 1981. The Gordion Excavations Final Reports, Volume I. Three Great Early Tumuli Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We want to thank the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in the Republic of Türkiye for granting us permission to conduct this project, as well as C. Brian Rose, Gareth Darbyshire, and the rest of the Gordion Archaeology Project team for their interest, generosity, time, and hospitality between 2021 and 2023. Richard Liebhart was an invaluable source of information about the long history of the tomb structure and its research, and he was continually patient as we tiptoed around and on the subject of his research for the past three decades. Ali Kurultay and Günce Öçgüden were tireless, meticulous, and essential co-workers. The U.S. Embassy in Ankara kindly awarded this project a grant in 2021 to begin this documentation process, and we also want to thank Koç University for supporting this work for the past three years.

Point cloud model of the inscription found in 2007; model by Michael Barngrover.

Toniná EXCURSION TO

THE DIARIES OF ADVENTURER AND ARTIST

Jean-Frédéric de Waldeck

BY JOHANN BEGEL, CARL CALLAWAY, AND PETER MATHEWS

From May 1832 to June 1833, French explorer and artist Jean-Frédéric de Waldeck led the first systematic study of the ruins of Palenque in southern Mexico. As early as August 29, 1833, his diary mentions correspondence with the parish priest Valentin Solís of San Pedro, in which they discuss Maya ruins near Ocosingo, 70 km south of Palenque. The first mention of the site of Toniná dates from the 18th century, and it had been visited by Guillermo Dupaix in 1808.

Waldeck led an eccentric life as an adventurer and artist. Of his early years little is known, yet he later proved to be a versatile and meticulous artist. His travel diaries and drawings are a wealth of information, and speak of his interest not only in history and ancient ruins, but also architecture, art, writing systems, customs, language, cartography, and herbology. Long overlooked because of his misplaced anthropological theories, sometimes too farfetched even for his time, his early contributions to Mesoamerican studies are now being reevaluated by an interdisciplinary group of researchers, revealing key observations and images of Maya art and architecture that in many cases have all but disappeared.

Waldeck’s diary includes an excursion to the ruins of Toniná, the most relevant extracts of which are quoted below. It is necessary to mention that Waldeck was very much a man of his time and culture, and his words are often imbued with a racism that reflects Western colonial attitudes. His 11-day excursion took him over the rugged Chiapas mountains, encountering a variety of people and places that he describes with brush and pen. At Toniná, he planned to survey the ruins and compare its art and architecture with his study of Palenque.

We present here an edited version of Waldeck’s journal of his trip to Toniná, which is preserved in the collection of the Newberry Library, Chicago. For brevity, we have shortened his narrative but have included all descriptions relating to Ocosingo and Toniná. Waldeck’s French grammar, spelling, and punctuation is at times weak; we have kept as close as possible to his original prose, but have made some changes, especially with punctuation.

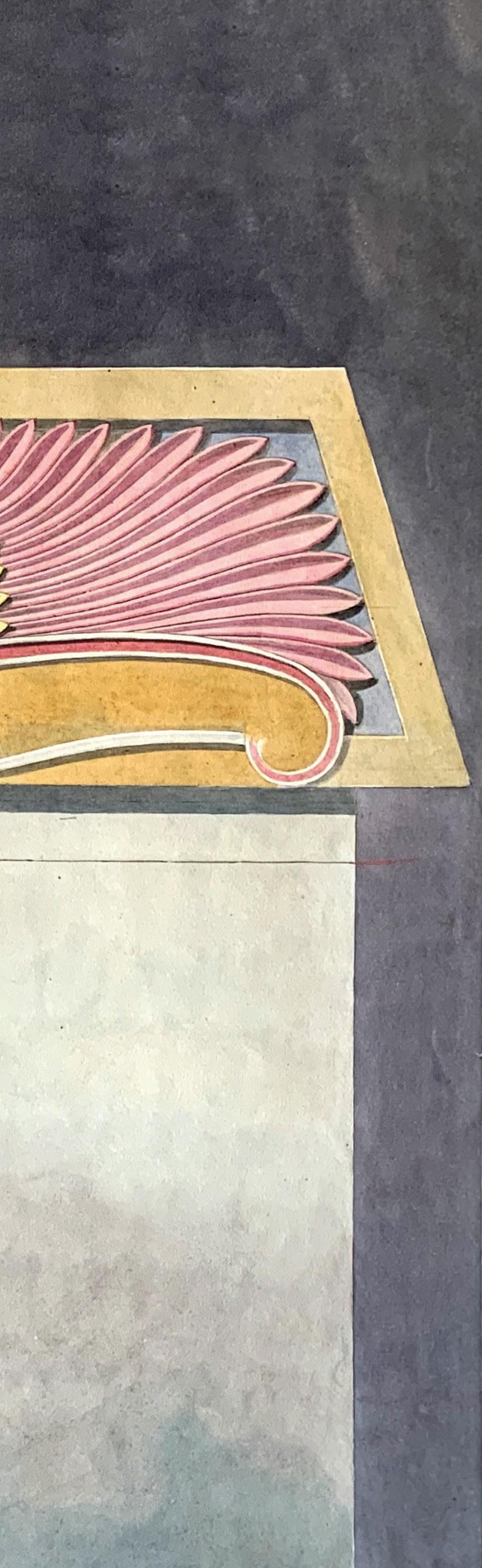

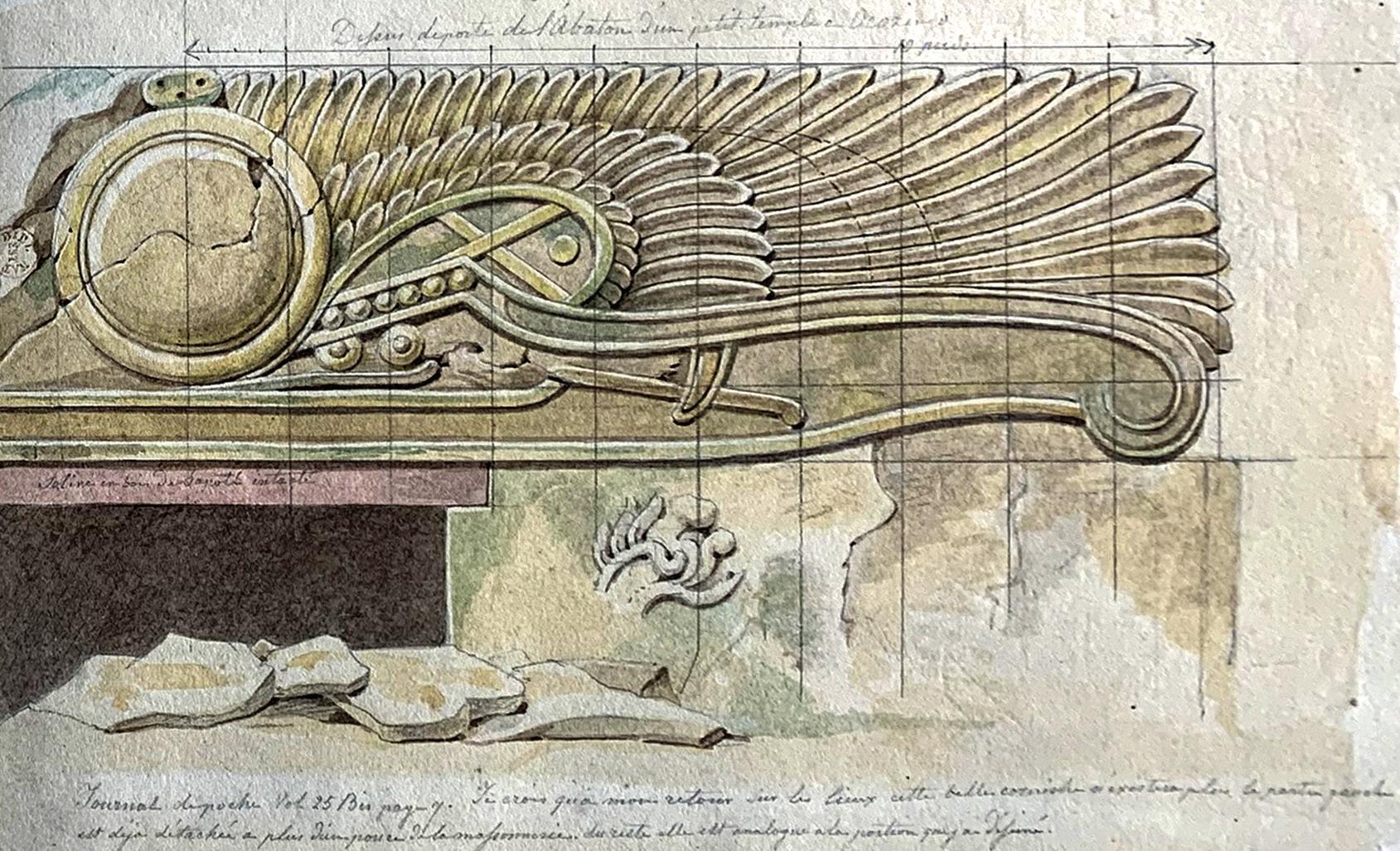

Reconstruction by Waldeck of a stucco temple façade.

In reality, only one half of the façade survived and he mirrored the one wing to make the full wing spread.

Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Editor’s Note: Although Jean-Frédéric de Waldeck’s journals contain valuable insights into the 19thcentury exploration of Maya and Aztec culture, Expedition wishes to acknowledge that his writings rely on a worldview informed by scientific racism and colonialist language that does not reflect the current views and values of the Penn Museum.

Monday, March 25, 1833

Left at 6 o'clock in the morning with José and the four Indians who carry my small luggage and the silla on which I must be transported to my destination. Near the forest, a shortcut which will save us almost two hours.

The road is rather good and instead of eight hours we can make it in six. At midday, we arrived on the small plain in the middle of which is situated the rancho, a house permanently not lived in, it is only a hut whose roof rests on six or eight palos [sticks] covered in buano [palm leaves]. The clearing is surrounded by a thick forest. We immediately made a fire and José went to look for caracoles [snails] in the river: it is the customary food of travelers because the ground is covered with the shells of this gastropod as useful as it is good to eat. At Palenque I made a fairly good plaster by calcining them, but it cannot be used for plaster molding. To eat them while traveling, they are cooked in a thick covering of ashes; at the ruins I boiled them in their own juices, as we do with mussels in Europe. I spent the rest of the day walking around and doing some herbology, and as soon as night fell, I admired the huge number of fireflies.

Tuesday, March 26, 1833

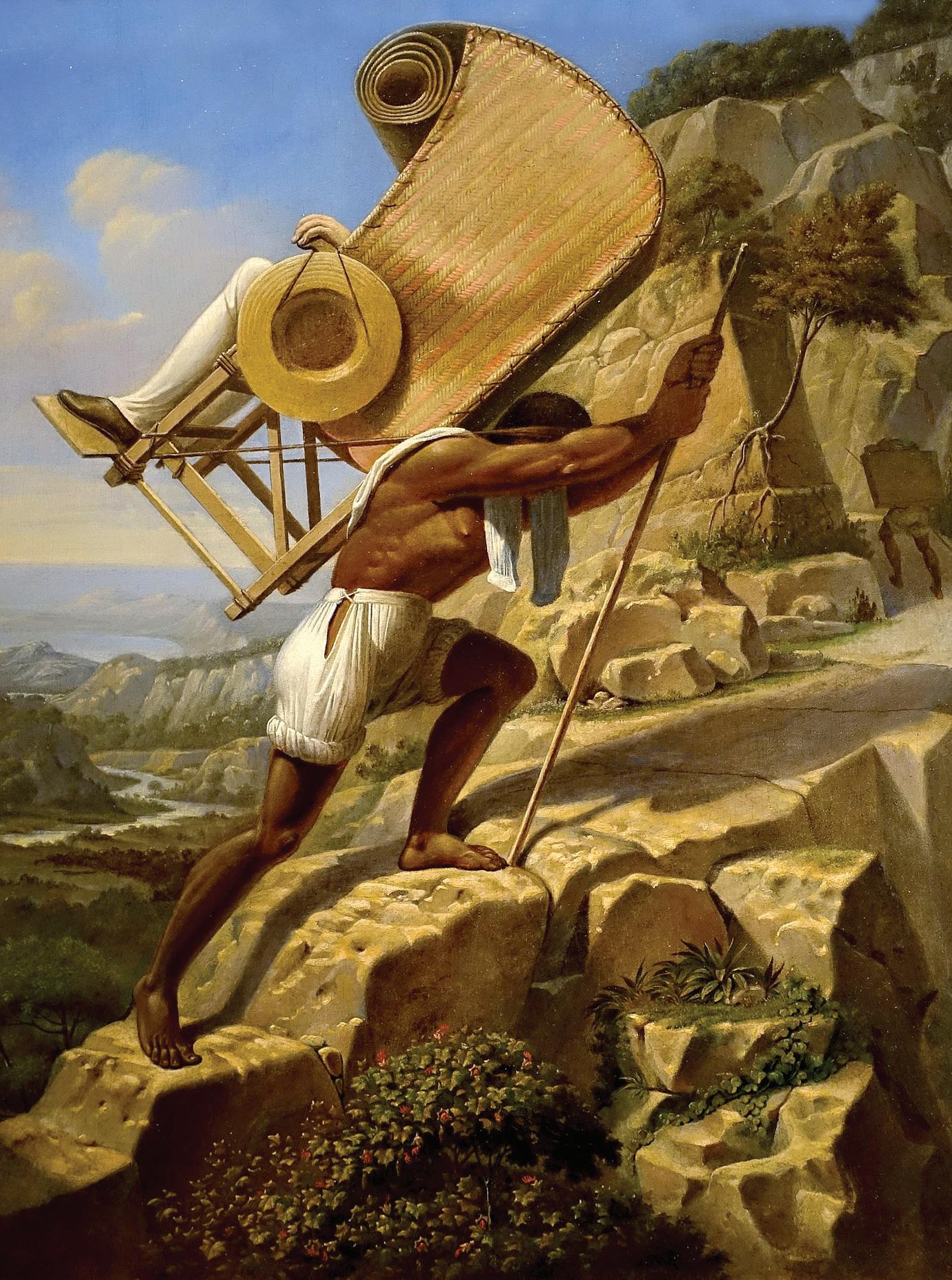

After a good breakfast of chocolate and caracoles we set out at 7:30 am, this time through very thick woods and a very rapid ascent. After crossing a river which we followed for some time, we began to climb the mountain which was not to end until the end of our day. I could not help feeling sorry for the Indian who was carrying me on his back. I believe that this is the place to give an idea of this way of locomotion. Four Indians are needed, who take it in turns to share the work during the day. The silla [chair] is a very crudely made chair, but very solid, even though it looks as if it's all broken up. Each village has two or three of these, which belong to the Cabildo [colonial administrative authorities responsible for governing municipalities during the Spanish Empire and later]. Each Indian is paid at the rate of 4 Reaux [Spanish dollar, or real de a ocho] for the day's journey. All the traveler has to do is sit in the armchair, put his feet on the board which is fixed at the bottom of the two front legs, cross his arms, or read if he can. And if it begins to rain, all he has to do to secure himself is to unroll the mat or petate which is above his head, and he will be quite comfortable. That's how I got there and back [by] a narrow and very difficult path, sometimes bordered by a precipice to the right, to the left, and once on both sides, very slippery and not more than two-and-a-half feet wide. I leave it to the reader to imagine what emotion I must have felt, with the prospect of a seemingly bottomless abyss and that of a false step that could throw me into one or the other! Finally,

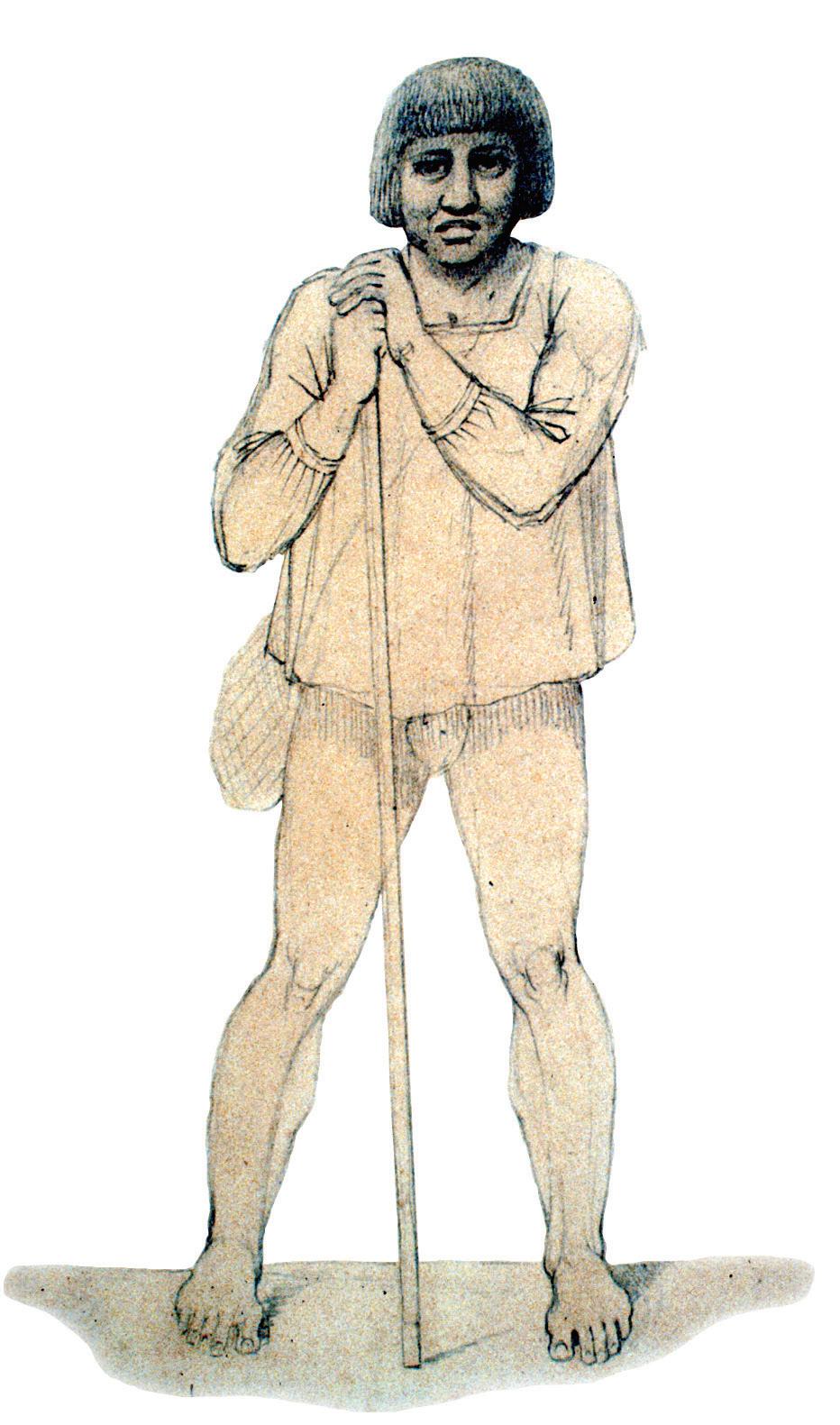

An ethnographic portrait painted by Waldeck, which he describes as an “Indian from Tumbala who comes to Palenque to sell cotton from the factory”; Waldeckiana Collection, courtesy of the Newberry Library.

the descent began, as fast and horrible as the climb.

At last at 3:30 we entered San Pedro. The parish priest Valentin Solís received me very well, and while we were smoking our cigars we talked about the customs of the Indians.

Wednesday, March 27, 1833

After breakfast we set off and began to climb again, then another distressing descent, and finally we came

to a halt near another small arroyo [creek], where all agreed to stop. Each Indian took his xicara [half a calabash], [and] a ball of sour corn paste. This drink is most refreshing in a hot country and especially after long, hard work. Another drink which is also prepared for the road is a compound of ground roasted corn mixed with ground cocoa and sugar, but it is a luxury which is only used by the rich, priests, and women who travel. We entered Tumbala at

FACTS and FALSEHOODS

The work of Jean Frederic Waldeck has long been discredited for its far-fetched interpretations, notably his identification of elephants in sculpture and glyphs or his hypotheses as to the IndoEuropean origins of Palenque's settlers. Yet his work contains a wealth of useful information for today's researchers. His earliest sketches are the most faithful and show a constant concern for accuracy, even more so than the hundreds of paintings and lithographs completed years later from memory after the originals had been seized by the Mexican authorities. From his field sketches, it is possible to reconstruct several stuccoed reliefs and inscriptions, it is possible to reconstruct bas-reliefs and inscriptions now partially lost after two centuries of erosion and damage by later visitors.

workers employed to clear the ruins.

His expedition to Palenque between 1832 and 1833 was undertaken against the unstable political context of General Santa-Anna's uprisings. Waldeck documented the many difficulties he encountered in dealing with state and local authorities. His eccentric, authoritarian character, coupled with his marked colonial racism, also earned him strong opposition from both the Western members of his expedition and the Indigenous

Nevertheless, once these ruminations have been set aside, his diary provides a striking picture of a small, isolated village in the Chiapas foothills in the early 19th century. It reveals the dynamics of local power, whether ecclesiastical or political, the place of the Indigenous people in this nascent postcolonial society, and the syncretism between ancient and Catholic traditions. Having lived in the village for almost ten months, and then for three others in a small ranch on the site, Waldeck observed and recorded a great deal of ethnographic data, such as the fate reserved for a Lacandon Maya albina. He described but also also painted, among other things, a Palenque carnival and a major celebration in the annual calendar. This event is still practiced today, but the explorer's details show later changes, such as the abandonment of body paint for dancers. Idle during the rainy season, the insatiably curious Waldeck took advantage of these delays to take an interest in other subjects such as botany, history (often-fanciful accounts that he was given), and Mayan languages, from which he drew a lexicon that is most useful to today's ethnolinguists.

Ultimately, despite the explorer's diffusionist views of Old World contact with the ancient Maya, the raw data collected by Waldeck during his stay at Palenque is proving to be a trove of art and historical insights.

Detail from Waldeck's painting of a Maya Jaguar Dancer; Waldeckiana Collection, courtesy of the Newberry Library.

HIDDEN LABOR OF EXPLORATION

In this startling painting from around 1833, Waldeck focused his brush on the invisible labor behind many scientific explorations of the 19th century. A local guide, known as a sillero, carries Waldeck on his back as they travel as they travel between Palenque and Ocasingo. The guide was not alone: He switched off in shifts with three other workers, and they were paid for their labor. Still, this image shows a stark power imbalance, one that Waldeck appears aware of—despite his continued participation in it. He has painted something undeniably heroic here, with the local man presented as the protagonist, and any hint of a self-portrait has shrunken quietly into the carriage. The Artist Carried in a Sillero over the Chiapas from Palenque to Ocosingo, Mexico, ca. 1833. Oil on wood panel, 49.2 x 41.6 cm. Princeton University Art Museum, Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund.

6:30 pm, where I asked the Padre for shelter for the night. This village is situated on the highest plateau of this cordillera [mountain range]. The antiquity of this site is forgotten, tradition does not say if it was built on the ruins of an older settlement, there is no trace of ancient structures. The Indians are too rough to suspect that they descend from an old race, they do not have the physiognomy of the Aztecs—I have drawn one.

On a rise behind the cabildo, the most splendid view imaginable unfolds before the eyes of the spectator: At his feet, there is the view of a ravine which sinks two or three thousand feet, and to the left a line of mountains on which can be seen the village of St. Pedro, behind these mountains those of Palenque, Playa de los Terminos, and the Gulf of Mexico. What a beautiful study for a landscape painter and how much I regret not being one! On the top of the platform there is a ruined church and a tower in the same state near which we can see a number of crosses stuck in the ground. It is the graveyard of criminals: Each cross indicates the sepulture of an Indian murderer! These Indians had, many years ago, tied the arms and legs of the local parish priest and had thrown him into the abyss of the place where we were. I have no doubt that such a tragedy could happen again if the village priest didn't have the diplomacy to make himself liked!

Thursday, March 28, 1833

At 7 o'clock in the morning we set off from Tumbala through a narrow passage between the rocks. Here and there the huts of the Indians are perched on the rocks. We reached Yaxalun, which we passed without stopping, and then continued on to Chillon, where the Prefect's house is, in which I spent the night.

Friday, March 29, 1833

I left Chillon at 8 am. At noon we arrived at Huaxachul, a village of Indians as wild as those of San Pedro and Tumbala, and at 3:00 I arrived at my destination, Ocotzinco, which, like Huaxachul, is situated on a plain surrounded by wooded mountains and has a lovely appearance. A rather beautiful church in the courtyard of which there are two figures of a

This village is situated on the highest plateau of this cordillera [mountain range].

The antiquity of this site is forgotten, tradition does not say if it was built on the ruins of an older settlement, there is no trace of ancient structures.

different style from that of Palenque set in the wall [editor’s note: possibly Toniná’s Monument 13], in the center of the Plaza there is an enormous and superb ceiba tree. I stopped by the alcalde [mayor who chairs the municipal council], for whom I had a letter from the political Chief of Palenque, Don Domingo Gonzales, who explained my mission to him. He received me politely and eagerly, and then asked me for a remedy for his daughter's eye, which had been in a pitiful state for more than six months. It was as big as an egg and discharging virulent pus. I examined it attentively, bathing it abundantly with fresh water,

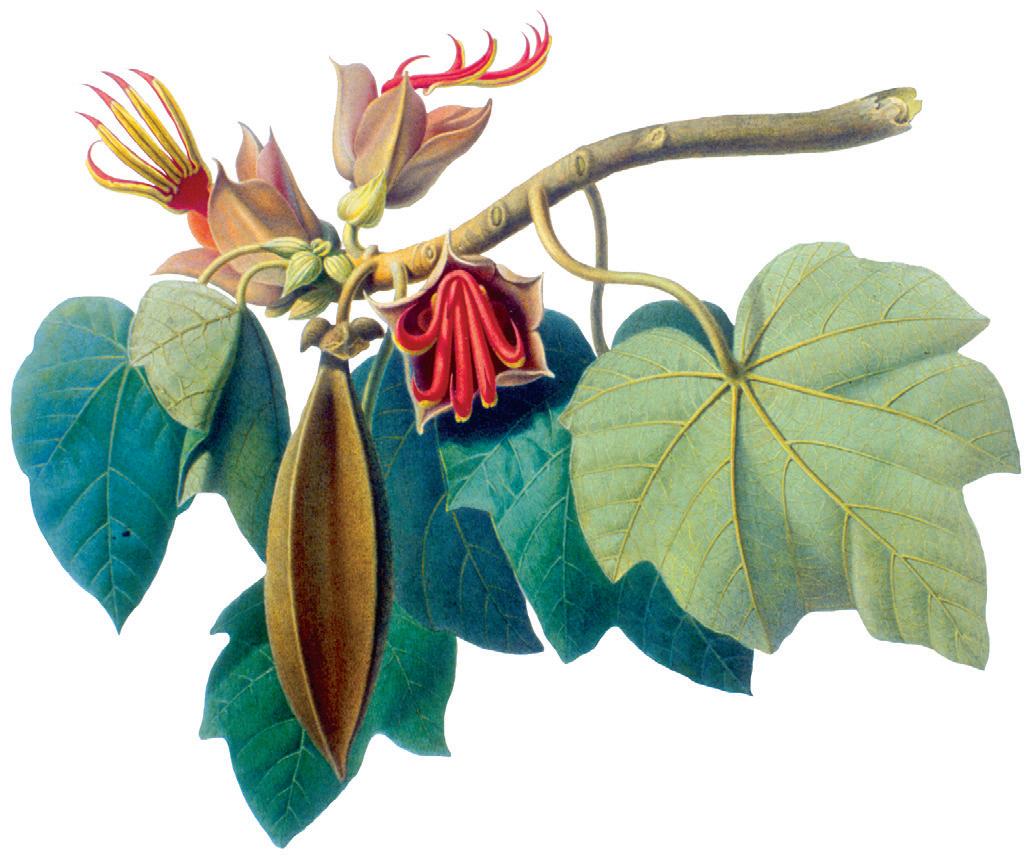

Waldeck painted this herbological study of the cocoa tree; Waldeckiana Collection, courtesy of the Newberry Library.

EXCURSION TO TONINÁ

and to my great astonishment I spotted the hairy leg of a small insect in the outer corner. Before nightfall I got rid of the insect, which had made a nest in the flesh. How much that girl had to suffer!

Saturday, March 30, 1833

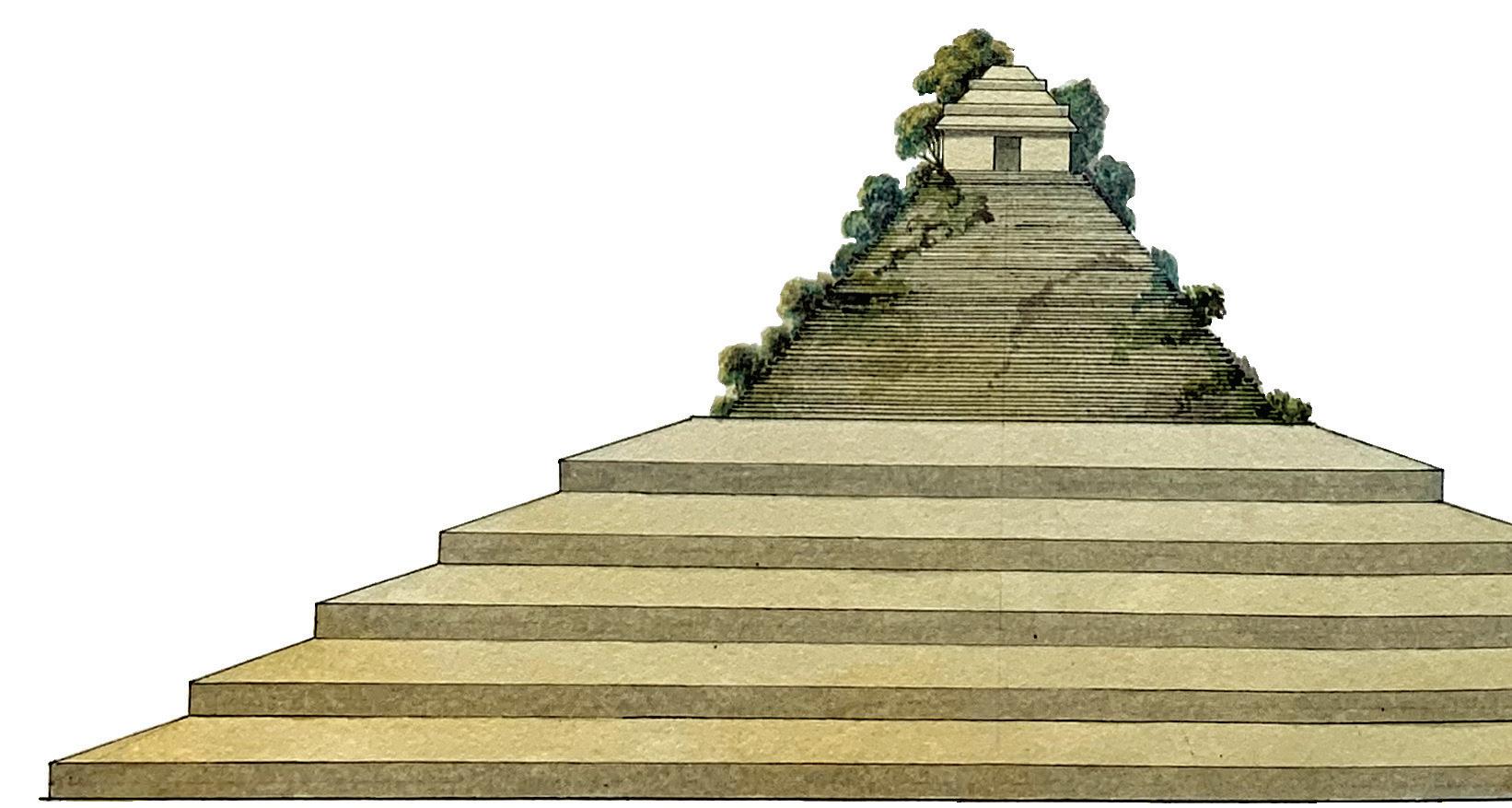

There are two-and-a-half to three hours of walk from the Village to the ruins of Ocotzinco, and we left for the Rancho of Doña Isabel where we arrived at 11 am. The mistress of the house, a young woman of mixed blood, pretty and well-dressed, received me affably, and when I explained the purpose of my journey, she replied in the customary manner Mui a la disposicion de usted, Cabalero ["At your service, Sir"]. And about half an hour later we were at the ruins. After having climbed up three kinds of stepped platforms we were in front of a Pyramid less deteriorated than those in Palenque and covered with a dense vegetation of trees. The monument on the Pyramid is similar in all respects to those at [Palenque]—of the same stone and lime construction. The interior layout differs only in that on each side of the first entrance door there is a square room with its own doorway. The second entrance doorway opens onto an aedicule [small shrine]. The facade above the door of this small chapel is very well preserved. It rests on a sapote beam of astonishing preservation. But what is even more astonishing is that this frieze represents a globe in the center, from which emerge two large, very well-worked wings, the colors of which have withstood the action of the damp air. The gables of these wings

are symbolic, forming an arch of Assyrian form. At the back of the aedicule there is a painted bas-relief in Stucco, representing two isometric figures facing each other; but there is not enough daylight to draw them, so I shall have to bring my Palenque machine [editor’s note: this was his name for his camera lucida, a small lens-based tracing device]. The chamber on the left of the aedicule is made up of perfectly preserved painted stucco reliefs, where one can see a very welldepicted monkey, but it has no tail. The chamber on the right is similar, but why is the stucco degraded and the paint faded? This is a problem that may be due to the position of the northwest angle of the temple in both cases, as in the middle one there is no light and the obstruction is so considerable that I will need a dozen Indians with the appropriate instruments for a complete clearing. While I was waiting to return to the site, I carefully drew up the facade and put off scrupulously measuring the building until the following day.

The galleries end in a pyramid [a Maya corbel vault], as at Ototiun [Palenque], with superimposed stones, one on top of the other, until they meet at a distance of 18 to 20 in. The galleries of Palenque are made of covered rubble, which is a notable difference, and the Columbaria, or holes that are lined up along these pyramid-shaped galleries can just as easily be the place of the putlog holes that supported the construction

“I

think that when I'll be back on the site, this beautiful cornice will no longer exist. The left side is already more than an inch detached”; courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

scaffolding, as the supports that I thought were used to hang mats or draperies. We returned to the village at 6 pm and I began to write down my ideas.

Sunday, March 31, 1833

I returned to the ruins with José to make a plan of the temple and explore the surrounding area. There are several other edifices in the forest, but they are all too covered in vegetation to be approached and recognized from the inside. Not being able to make either clearing for lack of the necessary things, and having by myself obtained the information which I wished, I prepared to return to Palenque where I arrived on Thursday the 4th.

POST-SCRIPT FROM THE AUTHORS IN 2024

Unfortunately, Waldeck was unable to return to Toniná. Sick and harassed by authorities, he was forced to leave Palenque on July 1, 1833, where he could not return due to a cholera epidemic. Instead, he headed to Yucatan to survey the site of Uxmal. The Toniná ruins were subsequently visited by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood in 1840, whose account and drawings of the same temple verify Waldeck’s observations. Frans Blom visited Toniná in 1922 and 1925. The first excavations were carried out by the French Toniná Project between 1972 and 1980 under the direction of Pierre Becquelin, Claude Baudez, and Eric Taladoire, followed by that of Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), led by Juan Yadeún Ángulo. Currently an INAH project to document and conserve the monuments of Toniná is being undertaken, under the direction of Martha Cuevas García, Luz de Lourdes Herbert Pesquera, and Ángel A. Sánchez Gamboa.

Dr. Johann Begel is a postdoctoral fellow at Centro de Estudios Mayas, UNAM, IIFL, tutored by Dr. Francisca Zalaquett Rock. Dr. Carl Callaway is Adjunct Professor at Austin Community College. Dr. Peter Mathews is Professor Emeritus at La Trobe University.

FOR FURTHER READING

Baudez, C.F. 1993. Jean-Frédérick Waldeck, Peintre: Le Premier Explorateur des Ruines Mayas. Paris: Editions Hazan.

Becquelin, P., and E. Taladoire. 1981. Informe de la cuarta temporada de excavaciones en Toniná, Chiapas. Estudios de Cultura Maya 13: 349–371. Maudslay, A.P. 1889–1902. Biologia Central–Americana. Archaeology, Volume 4. London: Porter and Dulau & Co.

Stephens, J.L. 1841. Incidents of Travel in Central America Chiapas and Yucatan Volume II. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Waldeck, J.F. de. 1833–1837. Nottes du Voyage de JF Waldeck Anre Commissioné. Vol. 26. an 1834. Manuscript, Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Collection: Newberry Library of Chicago.

Waldeck, J.F. de. 1838. Voyage Pittoresque et Archéologique dans la Province d’Yucatan (Amérique centrale) Pendant les Années 1834 et 1836. Paris: Bellizard Dufour et Compagnie éditeurs. London: W. Boone and Lowell.

A watercolor illustration of Toniná: “The large five-level base used as a fortification for the Pyramid and the temple that crowns it”; courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

A Bigger Picture of the Prehistoric Diet

By Phoenix Strouse

PLANTS ARE SUCH AN ESSENTIAL PART OF HUMAN LIFE, and yet they have often been overlooked in archaeological contexts. Last year, as a junior anthropology major at West Chester University, I began volunteering at the CAAM Archaeobotany Laboratory to learn more about the analysis of preserved botanical remains. After learning the skills required for identifying seeds and nutshells, I began to help sort materials recovered from archaeological sites. I was immediately drawn to the work of analyzing the seeds and soil under the microscope. There is so much opportunity and beauty in that tiny, hidden world if you look closely.

In the Fall of 2023, I completed a 120-hour internship in the CAAM Archaeobotany Lab. My lab

work was supervised by Dr. Chantel White, Teaching Specialist for Archaeobotany. I was able to sit in on her graduate Archaeobotany Seminar course, during which time I took part in the analysis of samples from a 40,000-year-old cave site located in Jordan. The cave site was occupied by anatomically modern humans (AMH) who left behind stone tools, animal bones, and charred plant remains from the fires they burned for heat and cooking. Looking at these burned seeds under the microscope, I could hardly believe that I was seeing fragments of the everyday lives of humans left behind so long ago.

Interestingly, many of the seeds found at the site, including wild vetch, wild lentils, and wild grass pea are toxic to humans unless they are processed

properly. When uncooked, the legumes we eat today still contain some of these same toxins called “antinutrients,” which can prevent the body from utilizing the nutrients in food. Frequent consumption of these toxins can lead to serious health issues. Just like modern people, our human ancestors would have needed to cook these seeds to make them edible. It is not as simple as picking them off the plant. As part of the class research project, we explored different preparation methods that ancient humans may have used to detoxify the seeds, including boiling, roasting, and soaking.

Looking at the ways in which early people adapted to their local resources helped me to recognize the importance of cooked foods. I was interested to find that AMH likely had similar diets to Neanderthals who were living in the same region just a few thousand years earlier. Could Neanderthals have also processed these plants for food? The possibility could suggest a greater degree of cultural exchange between these groups than has been previously recognized. Together with the other students in the Archaeobotany Seminar, our research on this topic was presented at the Society for American Archaeology annual conference in April 2024.

I am currently conducting my senior thesis research in the CAAM Archaeobotany Lab, analyzing burned seeds and nutshells from a 60,000-year-old Paleolithic cave site. It will be exciting to see where this project leads, and to see how it might contribute to the broader picture of prehistoric diet. The resources at CAAM have been instrumental in my academic journey. Going forward, I am especially interested in working toward developing improved methods of recovery and analysis, so that we can better unravel the stories hidden in the delicate remnants of burned plant foods.

For additional inquiries about the CAAM Archaeobotany Lab, contact Chantel White, Teaching Specialist for Archaeobotany, at chantelw@ upenn.edu.

Phoenix Strouse is a senior at West Chester University who completed a 120-hour internship at the CAAM Archaeobotany Laboratory.

Seeds that were studied came from the Paleolithic site of Mughr el-Hamamah, in modern Jordan; photo by Chantel White.

Graduate Guides Lead the Way

By Sarah Linn

WHAT STARTED AS A FEW CLASS TOURS

led by a handful of graduate students has become one of the primary ways visitors engage with the Museum’s galleries, collections, and research. The Graduate Guide Program grew out of two separate needs: Academic Engagement’s mission to include students more meaningfully in the Museum, and Group Sales’ efforts to meet demand for real engagement with experts. The solution? A corps of graduate students from across the University leading tours that connect visitors with Museum collections and their own research and field experiences.

Unlike gallery guide programs at other university museums—which typically train undergraduates to lead interpretive tours—the Graduate Guide Program draws graduate students from departments associated with Museum collections,

like Anthropology, Art History, and area studies in the Near East, Mediterranean, and Asia. These students are well-versed in their fields of study but have little experience sharing their knowledge with people outside academia. In an intensive day-long training, Guides learn how to make the content of the Museum and their own studies engaging, relevant, and relatable to various audiences. We discuss best practices, including methods that encourage visitors to look closely at objects, avoiding trivia in favor of open-ended questions that provoke deeper thought, and carefully navigating harmful or exclusionary language. Finally, Guides learn how to share stories, not just facts.

All Graduate Guides begin by learning the popular Highlights tour that covers one object in each of six to eight galleries. Through learning the Highlights tour, Guides become comfortable with

Graduate Guides use iPads to illustrate their tours. Left: Stephanie Mach, an Anthropology Ph.D. who graduated in 2024; right: Benjamin Abbott, an Ancient History Ph.D. who graduated in 2023.

N U M B E R O F T O U R S

ACADEMIC YEAR

material from areas outside their own regions of study, giving them a birds-eye view of the Museum collections and exhibition themes. New Guides lead practice tours and receive thorough feedback on narrative structure, pacing, and engagement.