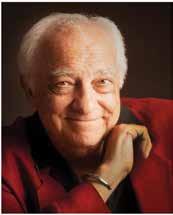

ED PENNIMAN

UntoUched:

contemporary landscape paintings of the central coast

Pacific Grove Art Center

May 5 through June 29, 2017

Schwan Lagoon, Santa Cruz, California, 2016, 48x48, oil on canvas, collection of Cindy Ranii and Shelly James.

i believe that the greatest trUths of the Universe don ’ t lie oUtside, in the stUdy of the stars and the planets they lie deep within Us, in the magnificence of oUr heart, mind, and soUl. Until we Understand what is within, we can ’ t Understand what is withoUt - anita moorjani, writing in dying to be me

Artist Ed Penniman’s paintings of California scenery go quite a bit deeper than simply showing us how he sees the world around him. Indeed, part of their depth is related to Ed’s familiarity with the coastal landscape of Santa Cruz where he was born, made his first paintings at the age of twelve and continues to live, but familiarity alone can’t account for the dreamlike vibrancy and spirituality that radiates from Penniman’s landscapes. They are—in many important respects—inner vignettes that transmit the deep appreciation for life of a man who has been to the brink of death and made a comeback. Penniman is an artist living out his second life: a life infused with humility, awe and gratitude.

Always inclined towards art, Penniman’s first life was centered on a career in design. After graduating from the Chouinard Art School with a degree in Fine Arts, Penniman—a hot young talent— had a job in advertising waiting for him. After a detour into his family’s escrow business, he climbed the career ladder nimbly, winning awards as a graphic designer and proving himself adept—even exceptional—in generating the kinds of images and forms that present corporations and their products convincingly and seductively. Penniman was clearly, in the material sense of the word, a success, although his record as a family man was noticeably flawed.

Then, at age 42, Penniman experienced a traumatic illness that would prove to be transformative: he was struck by Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS), an inflammatory nerve disorder that brought convulsions followed by paralysis.

Finding himself shockingly reduced in his physical capabilities, angry at the situation and uncertain about to what extent he might eventually recover, Penniman was turned inside himself to face a wall of angst and fear, with transformation and re-invention as his only options. “I had come to a crossroads in my life – a point in which my existence as I knew it needed to die,” he later wrote.

As he did recover—slowly—Penniman found that he was able to reach into a personal well of positivity to allay his fears and find the way forward. Among the positive by-products of this traumatic experience, Penniman found himself developing what calls a “witness consciousness” that allowed him to see the separation between his mind and body. Although his range of physical actions was severely limited, his state of mind offered glimpses of respite, control and even joy.

During his rehabilitation process—in which the most rudimentary daily activities were practiced and re-learned—Penniman was given an easel and paints. Since he could only move his head, he held the brush in his mouth. Rather than feeling disappointed by the results, Penniman soon felt “liberated.” Through painting, Penniman could momentarily transcend his physical limitations and express himself. “I learned to appreciate what I had,”

By John Seed

for Arts of Asia, Art Ltd., Catamaran, Harvard Magazine, Hyperallergic, The Huffington Post and Poets and Artists.

John Seed is a professor of art and art history at Mt. San Jacinto College in Southern California. Seed has written about art and artists

Ed Penniman in R.K. Davies Rehab Hospital, San Francisco, 1984.

Penniman recalls, “and to hold my self-criticism in abeyance. I suddenly appreciated everything.” Additionally the sense of limitation made every bit of progress precious and authentic: “As I progressed, I recognized more and more of my personal style in the art I was creating. It looked like I had done it. I had reclaimed a fundamental part of myself through my art.”

Another by-product of Penniman’s situation was that his physical limitations were so daunting that they forced him to confront and challenge his emotional and psychological limitations. In time, Penniman came to enjoy the psychotherapy sessions he was receiving, and was thrilled to encounter what he now calls the “intricacies of the mind.” Increasingly tender in his self-perceptions and in his relationships with others, Penniman blossomed into a much more self-aware human being, and this new, deeper awareness and sense of appreciation radiated into his paintings as he became able to work with his hands: “I started doing watercolors—landscapes—and they were like ‘places’ I could go. It was fulfilling to see nature come alive in painted form and to provide a destination for my inner journeys and meditations.”

Along with the process of deepening, Penniman found he was encountering a greater multiplicity of inner-selves and their associated roles. Some of these are reflected in the series of self-portraits that eventually filled the cover of his recently published book: You Are Up to You: Innovate a New Self for a New Life. Feel Spiritually Whole Again After Trauma and Disability. Increasingly leaving behind the “inner-child” that had been so prevalent before his paralysis, Penniman discovered and painted himself as a chef, a satyr, a priest and a Santa Claus (to name a few). As Penniman philosophizes in his artist’s statement, “Self-portraits are the most personal kind of artistic expression; brutally honest, unforgiving, revealing, self-referencing, frustrating, joyful, and/or uncomfortably objective.”

Now three decades past the shock and trauma of his original illness, Penniman is indeed a man with a more varied set of goals and perspectives and a deeper engagement with both himself and his community. A painter, writer and curator, Penniman has gone through a range of developments in his art that began with the idea of becoming a “really good landscape painter in the California Impressionist style.” He has certainly hit that mark, as his 2016 painting of Schwan Lagoon amply demonstrates: Penniman has a steady hand that works in concert with a superb sense of color. His paintings of California’s Central Coast have a great tranquility that reflects both Penniman’s sharp eye and inner peace.

Penniman’s recent move from watercolors into oils has allowed him a new range of experimentation—with his palette and with his brushwork—that has left him more free than ever to make “the joy of accidents” part of his artistic method. Penniman is also working a bit with the human figure and, partly as a by-product of his engagement with the unconscious via psychotherapy, is beginning to delve into the study and use of arcane symbols of the subconscious, as it has a symbolic, universal language.

Looking over Penniman’s works is likely to satisfy the soul and delight the eyes, but not because of the skill or training that are admittedly there, underlying their essence. The vitality of the work is hard won, the result of a deep psychic wakeup call that came into Ed Penniman’s first life when he neither expected or wanted it. As painting can teach us, sometimes it is the accidents that leave the richest traces, guiding us to reach for something that we are not even sure is there, grasping for meaning and paying attention to the new shapes of things that come next.v

comment

“when i was a child i caUght a fleeting glimpse oUt of the corner of my eye i tUrned to look bUt it was gone i cannot pUt my finger on it now the child is grown, the dream is gone.”

pink floyd

The paintings in this exhibit are intended to preserve and reflect my emotional response to the untouched places of beauty and to foster environmental stewardship. Certain locations draw me to paint them through their apparent numen— which is the power of either a deity or a spirit present in those places.

To date, the development of my painting has followed the lineage of the past historical periods of representational art. My knowledge and love of art history, along with the contributions of individual artists, help me to ground my work. This appreciation and understanding is also a solid foundation to support a new and authentic contemporary expression. Years of painting outdoors aligns me with nature, how I feel about it, and how I express myself in my mark-making. My ever-evolving mastery of the oil painting medium gives me an understanding of what the medium can achieve so that I may express my intention more clearly.

Recently I have found myself exploring new work that uses the underpinning of classical painting and explores deeper psychological realms. I have had the unique life experience of having everything taken away from me, of rebuilding myself, and now having an elevated clarity of vision and understanding of this life’s journey. I don’t want to squander these existential gifts, but rather tap into them and thereby continue to grow as a painter. I want to explore how my work can move people beyond a relaxing respite into a level of appreciation that will bone resonate.

In my explorations, I am not sure what my new work will look like. However, the lyrics from Pink Floyd’s song Comfortably Numb seem to express what I mean; it is a man’s boyish recollection of perfection: “When I was a child I caught a fleeting glimpse out of the corner of my eye. I turned to look but it was gone I cannot put my finger on it now. The child is grown, the dream is gone.”

As I paint, there is mystery in how memories, sensations, and perhaps my unconscious all emerge as tangible images. I alone know when I create a unique interpretative expression; it is where my effort begins and ends. I have always felt my paintings to be a step forward on the painting journey, each one closer to revealing a newer form, a newer expression, one that is subjective and at the same time universal.

I am trusting my process of evolution as a painter. v

By Ed Penniman

Photo of Ed Penniman: Mark Gottlieb

By Donna Maurillo

following his grandmother

“now, eddy, isn ’ t that better, now it has god’s hand in it.” ed’s grandmother ’ s comment after the wind sailed her canvas face down in sand when they were painting oUtdoors. -l. n. penniman

of UCSC in

included tech writing in Silicon Valley, then

found herself at the Minetta Institute with a MA in Public Transportation writing white papers about anti-terrorism. A popular food writer for the Santa Cruz Sentinel, she exhibits and sells her photos, has an amazing Italian vegetable garden in Scotts Valley where she lives with her cat Gary.

In most artists’ lives, there will be one family member who inspired them. For California artist Ed Penniman, it was his grandmother. Leonora N. Penniman was a well-known painter, who’s work is in the permanent collection of the Legion of Honor | Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. She taught him at an early age how to use a brush to interpret the world. Eventually, it would save his life.

Ed was born in the artistic community of Santa Cruz, California. Following his early education from his grandmother, he earned his degree in fine arts from Chouinard Art School of California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles. His creative talent caught the attention of Carson-Roberts Advertising (Ogilvy-Mather), where he was hired even before graduation. He also earned a graphic designer position for Robert Miles Runyan in Los Angeles. Since then, his exceptional graphic design has won many awards for corporate identity, packaging, collateral materials, and trade advertising.

His work was honored in the esteemed Communication Arts magazine, which featured an article about Ed. Examples of his work have been published in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Recently he lectured on Corporate Identity and Branding at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Baskin School of Engineering to students engaged in the Business Incubator Project.

saving his life throUgh art

Ed’s move from graphic design to fine art painting came as a result of a near-death experience. As an adult, Ed was stricken with Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare disorder in which his immune system attacked his nerves, leaving him almost completely paralyzed. After spending many months of hospitalization and rehabilitation, Ed moved into a wheelchair, then to a walker, and finally to a cane and leg supports. But he never gave up – not on his new challenges and not on his art. He knew that, without his art, he could not live with a disability. So he began painting, at first with a brush in his teeth. It was a restorative process to be part of nature, expressing what he saw around him.

On a trek to Eleuthera, Bahamas, Ed followed the painting trail of Winslow Homer. He also followed Paul Gauguin’s path to Tahiti, Moorea, and Rarotonga, producing exotic interpretations of people and landscapes. His plein air artistic journey has also taken him to the West Indies, the California coast, Italy, France, Spain, Holland, Canary Islands, Hawaiian Islands, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, Mexico, Baja California, the U.S. Southwest and Midwest, and the Canadian border. Closer to home, Ed had participated in the Arts Council of Santa Cruz County’s Open Studios tour for 25 years.

Leonora N. Penniman of “The Santa Cruz Three”

Graduate

photography, Donna Maurillo’s career

she

passing his grandmother ’ s legacy

Any artist, no matter how well known, must set a path so others may succeed – connecting past and present artists with the next generation. Ed, true to that mission, curated the Santa Cruz Art League’s Annual Statewide Landscape Exhibition from 2007 through 2016, redirecting the show to a more contemporary and relevant vision focusing once more on landscape painting. This was yet another example of his grandmother’s influence. She had established the exhibition in 1926, along with Margaret E. Rogers and Cor deGavere – Santa Cruz artists who were known nationally as the Santa Cruz Three.

During the exhibition’s recent resurrection, Ed selected Jean Stern, curator of the Irvine (Calif.) Museum, as its juror. Other noted jurors have included Scott A. Shields, curator and author from Sacramento’s Crocker Museum; Richard

Mayhew, member of the National Academy; and Nancy Boas, former assistant curator of American painting for the San Francisco Fine Arts Museums (De Young and Palace of the Legion of Honor) and author of The California Colorists: Society of Six, and David Park, A Painter’s Life. Most recently Michael Zakian, curator of The Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University, judged the 83rd Annual Statewide Landscape Exhibition. Kevin Macpherson, David Leffel, Rene deGuzman, curator of the Oakland Museum, and David Gallup, painter, were jurors chosen by Ed. Ed stepped back from his curator position, entering a piece that won second place.

Throughout his life, Ed has continued to paint and design, becoming even more prolific. He is still following the grandmother who first inspired him. v

“Soberanes Fire 2016,” Oil on canvas, 40’x30”

“Hidden Lake, “Oil on panel, 24”x16” “Cloud Circle,” Oil on panel, 12”x16”

“Grassy View,” Oil on panel, 30”x24”, “Yellow Pond,” Oil on panel, 30x24”

“Booming Sky,” Oil on canvas, 40”x30” “Purple Hillside,” Oil on panel, 12”x16”

“Path to ice plant, “Oil on canvas, 40”x30”

“Pogonip Hillside,” Oil on canvas, 48”x48”

“Poetic Reserve,” Oil on panel, 16x12”

“Coastal Haze,” Oil on canvas, 24”x18”

“Sun spot,” Oil on panel, 12”x16”

“Corcoran Lagoon,” Oil on canvas, 48”x48”

“Moss Landing Preserve,” Oil on canvas, 40”x30”

“Orange Funnel,” Oil on panel, 12”x16”

“Cowell Beach,” Oil on canvas, 48”x48”

“Blue Granite Rocks, Yosemite,” Cor de Gavere (1877-1955), 44”x36”, Oil on canvas, 1937, Collection of Ed Penniman

romance of the landscape: santa crUz and the california plein air movement

in the open air yoU are inspired to Use colors that woUld have been Unimaginable in the more diffUsed lighting of the stUdio. —pierre-aUgUst renoir

It has become something of an historical aphorism that the birth of the plein air art movement in California — with its implicit nod to both the Barbizon school and Impressionism can be traced directly to the legendary Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915, which opened in San Francisco in February of that year. With more than 4,500 paintings on display by artists from around the world (including significant landscapes by Monet, Pissarro, Millet, Renoir and Corot), the nearly year-long PPIE exhibition certainly brought a heightened awareness of contemporary European (and, also, Far Eastern) artistic styles to California’s general public. But the transition of California’s dominant pastoral aesthetic from a majestic view of nature, with somber tones and grandiose panoramas reflecting the dominant colonial sensibilities of 19th century Britain and Germany, to a more intimate and immediate naturalism, with softened forms and more colorful, imaginative palettes, actually began much earlier, in the late 1880s and early 1890s. If anything, the PPIE reflected the culmination of a regional artistic movement, centered in both San Francisco and Monterey, that had taken several decades to develop and mature.

During the robust era of California’s Gold Rush and stretching into the 1870s, visiting artists to the region brought with them their native cultural sensibilities that, for the most part, had been fostered in northern Europe or the eastern United States. In a sense, the early California landscapes of artists like Thomas Hill, Charles Nahl, Albert Bierstadt, Ernest Narjot, and William Hahn, reflect the imposition of a cultural aesthetic on the region, rather than an aesthetic derived and rooted in place. It is an important distinction. There were also economic underpinnings to the aesthetic, as there so often are to cultural expression, as the market for California paintings leaned toward those renditions that were both traditional and familiar.

But as landscape painters began spending more and more time in California, and indeed, as a new generation of artists who were born and raised in the Golden State came of age, the varying intensities of sunlight and color in California, particularly in the coastal regions, began to impose themselves on the styles and sensibilities of its artists, calling for a brighter palette and more delicate interpretations of light. And if the works of major European painters were not coming directly to California during this formative era (although George Inness, considered the greatest American landscape painter of his generation, and a practitioner of the Baribizon school, made an impactful visit to the region in 1891), the rising generation of California painters during the 1880s and 1890s almost invariably sojourned to Europe for schooling and intense cultural encounters with European masters. They studied at the

By Geoffrey Dunn

Geoffrey Dunn, PhD, is an awardwinning journalist, historian and filmmaker. He is the author of Santa Cruz Is in the Heart and served as editor of Chinatown Dreams: The Life and Photographs of George Lee. His films include Dollar a Day, Ten Cents a Dance; Miss…or Myth?; and Calypso Dreams. He was the recipient of a Gail Rich Award in 2002 for his many and varied contributions to arts community in Santa Cruz County. He is currently at work on a book about the poet George Sterling and the Carmel Art Colony.

Royal Academy in Munich and later at both the École des Beaux-Arts and Académie Julian in Paris. Europe thus had its influence, but it was no longer dominant, and as the light and unique landscapes of California asserted themselves, a native cultural aesthetic, if you will, was born.

The dean of California landscape painters during this transitional era was, without question, William Keith. Born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1838, Keith immigrated with his family to New York in 1850. Apprenticing as a wood engraver as a teen, he worked throughout Europe and the United States before settling in San Francisco in 1859, where he eventually opened his own engraving business. By his mid-twenties, however, he had taken up painting, went abroad for study in Düsseldorf, Germany, and soon made painting his career. Befriending fellow Scotsman John Muir in the early 1870s, Keith began making journeys to the Sierras, where he painted magnificent landscapes that reflected both his training in Germany and the popular styles of the day. He became wildly successful and earned the nickname “California’s Old Master.”

Following the death of his wife in 1882, Keith actually spent part of a summer painting and teaching in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Two important works from Keith’s oeuvre — Misty Mornings in the Santa Cruz Mountains and Moonlight in the Santa Cruz Mountains — were completed during this period. He also courted his future wife, Mary McHenry, during this rejuvenating moment in his life, which also foreshadowed a profound shift in style. After visiting Europe from 1883-1885, Keith’s renderings had taken on a tonalist sensibility, far more intimate and lyric in their mood.

“When I began to paint,” he acknowledged in a talk in 1888, “I could not get mountains high enough nor sunsets gorgeous enough for my brush and colors. After a considerable number of years experience, I am contented with very slight material—a clump of trees, a hillside and sky; I find these hard enough, and varied enough to express any feeling I may have about them.” The shift in California landscape painting had commenced.

While Keith was centered in San Francisco, a secondary cultural epicenter developed in Monterey, with the arrival

of the colorful Jules Tavernier in 1875. A native of Paris, and schooled at the prestigious Ecoles de Beaux-Arts, Tavernier worked his way across North America as an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly. He was once described by a San Francisco journalist as “free born, unconventional as the wind, ignorer of public opinion, generous, interesting, erratic, improvident, high strung—all of these things he was in superlative.” He was also a most talented artist—he worked in oil, watercolor and pastel—and embraced the artistic innovations of the Barbizon school, located in the Fontainbleu Forest, just outside his native Paris. As Scott A. Shields has noted in his brilliant work, Artists at Continent’s End: The Monterey Peninsula Art Colony, 1875-1907, Tavernier broke with the early California aesthetic of Hill and Bierstadt, and created “more intimate views of nature rendered with a freer and more spontaneous handling of paint.”

Although Tavernier’s sojourn to Monterey would last not quite four years—he angered local residents with derogatory compositions of street scenes published in the San Francisco Call—the artistic impulse in Monterey, and nearby Carmel, had taken hold. In the ensuing years, Keith and Inness would make extended painting journeys to the peninsula, while the likes of Julian Rix, Raymond Dabb Yelland, Meyer Strauss, and Gideon Jaques Denny would come to the peninsula for extended stays or to establish studios of their own. During the first decades of the 20th Century, leading up until the conclusion of World War I, a bevy of first-rate California landscape painters, including Charles Rollo Peters, Arthur and Lucia Mathews, Will Sparks, Xavier Martinez, Charles “Carlos” Hittell, Gottardo Piazonni, Ann Bremer, Evelyn McCormick, Mary Curtis Richardson, Francis and Gene McComas, Eugen Neuhaus, Albert DeRome, Mary DeNeale Morgan, and, perhaps most notably, Armin Hansen, would either call the peninsula home or take extended painting excursions there.

It would be an overstatement of grand proportions to say that Santa Cruz, with its economic foci on limestone, tanneries, commercial fishing, lumber production, and an incipient tourist industry, was in anyway central to the bourgeoning California art scene of the late-19th and early 20th

centuries; it was not. Although close in proximity to both San Francisco and Monterey, it was nevertheless geographically isolated and culturally conservative, and Santa Cruz marched to the beat of an entirely different drum. Nonetheless, the cultural gravities of both San Francisco and Monterey had their impacts here, and Santa Cruz developed a satellite art scene of its own.

There were two leading figures in Santa Cruz during this era: Frank L. Heath, raised in Santa Cruz and the son of prominent local businessman and politician, Lucien Heath; and Lorenzo Palmer Latimer, a native of the Sierra Nevada, and the son of a federal judge. (Their social status reflected the upper-class backgrounds of many—but not all—California artists during this era, who could afford formal training and study abroad.) Heath studied at the San Francisco School of Design under Raymond Dabb Yelland, who had a life-long influence on his student’s work, and he lived and worked in San Francisco for more than a decade, before returning to Santa Cruz and eventually opening a palatial studio on Beach Hill. In 1885, with the financial support of Frederick A. Hihn, he founded the Society of Decorative Art of Santa Cruz, which operated an art gallery on Pacific Avenue until 1891. Latimer, the same age as Heath (they were both born in 1857), also studied at the School of Design (his mentor was Virgil Williams), and, while he maintained a residence and studio in San Francisco, both he and Heath began teaching art classes in Santa Cruz in the 1890s. These groups of students

Top:

William Keith (1838-1911)

The idea for the Sierra Club was discussed in his art studio with his friend John Muir.

Above:

Frank Lucien Heath (1857-1921)

Felton Lime Quarry 1931

L.N.Penniman, oil on canvas, 18”x15”, 1931.

Collection of Ed Penniman

became known as “The Jolly Daubers.”

One of Heath’s most promising students, Lillian Josephine Dake, recalled that Heath “would rent a horse and carryall, and the livery stable would send it around early in the morning to pick up each member of the art class. Then we’d go to Felton or Scotts Valley or up the coast toward Davenport to spend a day painting.”

Dake and another young Jolly Dauber, Lillian A. Howard, would come to play significant roles in the nascent Santa Cruz art scene. Dake, a native of Milwaukee, arrived here with her widowed mother in 1877. She first began her formal

study of art in New York City, but returned to Santa Cruz, taught art here, and eventually married her mentor Heath in 1897. She was a delicate and accomplished watercolorist, her early works showing a strong trace of Barbizon tonalism, and she continued an active career in painting until well into her 90s. Like many other painting couples of the era, Dakecum-Heath opted solely for watercolors, while her husband focused on oils. She would later claim that she abandoned oils because her husband’s were “so superior,” though such a gender-determined faultline was typical of that generation. Howard, a native of Richmond, Indiana, began her pro-

Studio of Frank Lucien Heath, 1897, Native Santa Cruz artist. Geoffrey Dunn Collection

“Untitled Seascape,” Luther Evans Dejoiner, (1886-1954) 12”x12”, Oil on canvas, undated. Collection of Ed Penniman

“Untitled Landscape,” Frank Lucien Heath (1857-1921) 20”x13,” Oil on canvas, undated. Collection of Ed Penniman

fessional career teaching botany at Santa Cruz High. She was an avid naturalist painter and had 400 of her stunning botanical watercolors entered into the World’s Colombian Exposition of 1893, in Chicago. An article in the January 11, 1893, Santa Cruz Daily Surf, entitled “A Floral Four Hundred,” noted that “Howard’s magnificent collection of Pacific Coast flowers painted in watercolors and neatly mounted has been selected for the coming ‘dress rehearsal’ in San Francisco and at the World’s Fair in Chicago. This is a matter for congratulation, not only to Miss Howard but to Santa Cruz, as the exhibit will redound to the credit of both.” She was awarded a medal of merit for her efforts.

In 1911, Howard began teaching art classes at Santa Cruz High. Her superbly crafted pen-and-ink sketches of local scenes—the Cowell Ranch lime kilns, the ruins of the Santa Cruz Mission, the local Chinatown—served to illustrate early publications of the then-monthly Santa Cruz Trident. She was also a talented landscape watercolorist, often working in a small 6” x 8” format en plein aire, and painted scenes from Alaska to Africa, and throughout Europe. She was to have a profound impact on a generation of Santa Cruz High art students until she returned to her native Indiana in 1924.

By the end of World War I, Santa Cruz had formed its own critical mass of talented artists. In the fall of 1919,

an aging Frank Heath and one of Latimer’s more talented students, Margaret E. Rogers, a force of nature in her own right, formed the Santa Cruz Art League. Heath was its initial president, Rogers its vice-president. In a formal statement issued at its first meeting, the organization declared: “For a long time it has been contemplated to organize a club of a society, for the encouragement of Art in Santa Cruz; a place through which we could come in touch with visiting artists, and they with us.” They would also use their new home, the Seabright Crafts building, to stage a steady stream of exhibits, where they could bring their work together “for discussion and criticism,” and by so doing, “stimulating us to greater efforts for advancement.”

The Art League soon became the leading cultural organization in Santa Cruz County. In March of 1920, the League held a large “Spring Exhibit” in its new and refurbished Seabright gallery space, where some 53 works by local artists were on display, including those by both Heaths, Howard, Josephine Keck, Phillip Dodge, R. Clarkson Coleman, Mabel Lemos, Sydney Lemos, Maud Klipple, and Rogers, whose watercolors, the Santa Cruz Sentinel noted, had recently appeared in an Oakland exhibit, and that “the attention they attracted there is being repeated here….She has hung also, ‘Low Tide’ [an oil], which grows upon one as it is studied: A luminous sky, whose touch of pink is reflected

“Untitled Seascape,” 1931, Margaret Esther Rogers (1872-1961), 36”x15”, Oil on canvas, Collection of Ed Penniman

in the foam of the receding wave; in sharp contrast is the colors of the sea-wet rock and of the foreground, and there is movement here, you sense the pull of the out-going tide.”

By mid-decade, the Art League and its exhibits were beginning to attract regional attention. Frank Heath, who had died of cancer in 1921, had passed on the organization’s mantle to Rogers. She was clearly the engine that pulled the train. She was joined in her efforts by two close associates, Leonora Naylor Penniman, a native of Minnesota who had married into a prominent Santa Cruz business family; and Cornelia “Cor” de Gavere, a recent immigrant from Holland. Together they became known around statewide art circles as “The Santa Cruz Three.” They traveled together, went on painting excursions, and engaged other artists and art organizations throughout the West. They eventually held shows together under the rubric, from Berkeley to Sacramento to Stockton.

Rogers herself was British by birth. Born in Birmingham, England, in 1872, she and her family immigrated to southern Monterey County, near King City, in 1872, and established a ranch, not far from John Steinbeck’s grandparents, the Hamiltons, immortalized in the novel East of Eden. The young Margaret soon developed a hard-wrought reputation as one of the finest equestrians of the region. In 1893, at the age of 21, Rogers was the subject of a full-page account in the San Francisco Examiner, “A Centaur in Petticoats,” that noted “Monterey County boasts of a young woman who is as good a vaquero as is to be found in a county full of vaqueros.” The article went on to observe that she “plays classical [piano] and paints in oil” and that after “Miss Margert E. Rogers comes in from a day on the range she is ready to entertain visitors in the parlor with music or an intelligent discussion of the latest in art and literature.”

Rogers moved to Santa Cruz in 1905, and, in 1911, began her studies with Latimer. In her unpublished memoirs, “Eighty Years in California,” she noted that “Mr. Latimer came to Santa Cruz three times a month in the summer [to teach]. I took lessons each year, and worked myself in between. We all strived to paint as much like him as we possibly could— with the result that we were all branded with his influence.” Indeed, many of Rogers’ earliest watercolors look so much like those of Latimer’s that they were often taken for his. But

Rogers soon became known for her maritime paintings, both oils and watercolors, and she developed a broad-stroke style clearly her own.

If Rogers was a child of the open range, Leonora Naylor Penniman was born of the academy. Her father was a professor at the University of Chicago, where she studied art with Emma Siboni, and some of her early efforts were selected for the International Exposition in Paris. In the aftermath of the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, Leonora moved to Santa Cruz, where she soon married Harry Penniman and became active in his family business, Penniman Title Company. In 1919, she joined with Rogers and Heath in forming the Art League. She also continued her formal art training, spending a year under Lyonel Feinenger at Mills College and taking private lessons with the distinguished Armin Hansen in Carmel. As the one member of the Santa Cruz Three who could drive and own a car, she was often in charge of travel arrangements. Moreover, her works were selected for exhibition in Legion of Honor shows in San Francisco, with two of her watercolors being chosen for the Legion’s permanent collection.

The most talented of the “Santa Cruz Three,” however, and, arguably, the most talented painter of her generation of regional artists, was Cor de Gavere. Born to missionary parents in the then-Dutch colony of Java (Indonesia) in 1877, she was orphaned at the age of six, and raised by an uncle in the north of Holland, where she attended public schools. On the eve of her 30th birthday, and trained as an assistant in pharmacy, she took up formal study at the Royal Academy of Art at The Hague. In the years preceding World War I, she moved to Paris, where she studied in the atelier of Charles Guerin, and her palette shifted from earth tones to brighter primary colors. During the war, she served as a volunteer nurse for the Red Cross.

De Gavere relocated to Santa Cruz in 1920, with a close friend, Wilhelmina Van Tonnigen, and the two became part of the city’s vital Dutch community centered in the Seabright area, to the west of Wood’s Lagoon. She quickly befriended Rogers, who also resided in Seabright, and the quiet and refined Cor and the rough-and-tumble Rogers soon began weekly painting expeditions throughout the Monterey Bay

area. (When Penniman and her car joined the fray, they traveled even further.) De Gavere’s work differed from others in the region quite significantly. She had far more extensive training than any of her local contemporaries (she also studied with Arthur Hill Gilbert in Monterey), and her work reflected strong European influences that were perfectly suited to the light and varied landscapes of Northern California. She once said of Santa Cruz: “I realize it’s possible [for] a place to inspire the artist and I have never wanted to leave.”

In the fall of 1927, S. Waldo Coleman, the owner of the Casa del Rey Hotel, located directly across from the Coconut Grove and Casino on the Santa Cruz waterfront, encouraged members of the Art League to stage an art exhibition as a way of inducing visitors to Santa Cruz—and his hotel—during the winter season. Rogers, Penniman, de Gavere, and their colleague at the Art League, Bertha Rose, took to the task, and the First Annual Statewide Exhibition commenced

from February 1-15, 1928, in the Bay Room and spacious sun parlors of the Casa del Rey. By all accounts, the first statewide exhibition was a wild success. Some of the state’s best known artists, including Burton Boundey, Benjamin Brown, William Clapp, Phil Dike, Jade Fon, Selden Connor Gile, Emile Kosa, Otis Oldfield, Millard Sheets, Gunnar Widforss, and Karl Yens participated in the inaugural exhibition. Works by several well-known local artists, including Margaret King Rocle, Luther de Joiner, Josephine Keck, along with those by Rogers, de Gavere and Penniman, were also exhibited.

For more than three decades, the Santa Cruz statewide was one of the pre-eminent exhibitions in California. Several more of the state’s top landscape painters entered their works during this era, including Frank H. Cutting, Jade Fon, Albert DeRome, John DeVincenzi, Armin Hansen, Jerome Jones, Paul Lauritz, Laura Maxwell, Thomas McGlynn, Mary DeNeale Morgan, George Demont Otis, Charles Reiffel, William Ritschel, Louis Siegriest and Nell Walker Warner. And a growing list of prominent local artists also participated in the annual exhibition, including Jean and Jon Blanchett, Claude and Leslie Buck, G.C. McGreggor-Gregg, Maude Klipple, Lillie May Nicholson, Mildred Norman, Hazel Rittenhouse, Marion Ross, and Clarence Taubenheim.

Well into the 1950s, when the exhibition began shifting to a more local focus, Santa Cruz businesses sponsored entries in the annual affair by placing advertisements in area newspapers featuring the works of local artists. “Art Week” was celebrated in the city with a series of festivities, including a grand opening reception to the statewide, with the entire community embracing the exhibition. And for two weeks every year, Santa Cruz assumed center stage in the world of California landscape painting. v

“Pogonip, Santa Cruz, California”, 1934, Cor de Gavere (1877-1955), Collection of Ed Penniman

pacific grove art center

Patrons List

Arts Council for Monterey County

Monterey Peninsula Foundation

Nancy Buck Ransom Foundation

Barnet Segal Charitable Trust

Upjohn Foundation

Yellow Brick Road

teresa c brown Executive Director

elizabeth stein Gallery Manager

pacific grove art center

Building Community Through Creativity 568 Lighthouse Avenue : : PO Box 633 Pacific Grove, CA 93950 (831) 375-2208

Gallery and Office Hours: Wed-Sat 12-5 pm Sun 1-4 pm www.pgartcenter.org generalinfopgac@gmail.com contact ed@penniman.net edpenniman.faso.com (831) 462-2333