0. Abstract

This thesis aims to explore the construction of humour in architecture. While there are examples of humour in postmodern architecture, primarily in the discussions on wit, symbolism and contextualism to existing European architectural expression, this essay ventures further to the use of humour and its techniques of referencing and reframing to explore the possibility of its use in architectural design. Humour exists diversely in all other artforms, where in film, humour is expressed beyond form and has the physiological and mental ability to create scenes that make one laugh, bend expectations and bring forth new meanings to established norms. Can humour thus be able to do the same in architecture?

Through an examination of humour, its philosophical theories and its techniques used in film, I explore how the film Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) uses techniques of referencing to create humour throughout the film and to then use it as a lens to study existing architectural spaces that subtly arrest our attention, redirect and relink our perception of spaces.

The thesis is divided first into the study of humour – its theories, examples in architecture and in the film, Everything Everywhere All At Once. Then an analysis of how humorous referencing is brought about through filmic language and mapping its translation into architectural language through the study of architecture works to find methods of constructing humorous architecture.

Keywords: Humour, incongruity, comedy film, referencing, constructing architectural humour.

Research questions:

1. What is the value of humour? What is its value relating to construction and perception of architecture?

2. Why is humour not discussed more extensively within the architectural discourse? How does it manifest itself in other mediums?

3. How is humour constructed in film and how can it be translated into constructing humour in architecture?

4 Humour in Architecture

5 Humour in Architecture

1. Introduction

We all experience humour in our everyday lives. Having a “sense of humour” being a source of entertainment, enjoyment, and happiness. Yet, humour that is inverting and incongruous, has also been a tool for critiquing and bringing to attention our invisible norms, Humour, however, is rarely considered in the design process in architecture, likely due to architecture’s own self-seriousness and humour’s perception of being below high culture and therefore, beneath academia’s view1. Postmodernist architecture and humour have both been discredited for their inherent jocular nature. The former being considered “historiographic cliché… seen as synonymous with a certain ‘easy’ aesthetics” and being written off by critics such as Fredric Jameson, Hal Foster and Kenneth Frampton, who has described postmodernism as “pastiche”, “cliché” or “kitsch”.2 Similarly, humour is negatively viewed within historical philosophical discourse beginning with Plato considering laughter to be malicious and a result of losing self-control3, and this negative connotation continuing through in current times.

However, in other mediums, humour is readily examined as the genre, Comedy, which is defined as the attempt at planning something humorous4. Comedic directors, such as The Daniels, have managed to harness humour in the film medium, which has established humour that is continually practiced and re-imagined in contemporary media, having various sub-genres of comedy being vastly developed. While humour is rarely discussed academically, there is value in its ability to create a dialogue that subverts the current order, bringing awareness and subversion of one’s understanding and use of a topic. However, one must be cognizant of the nuances of humour that manifests itself as one-liners, parody, or satire, that is not critical and only makes fun a subject, leading again to humour’s push into irrelevance in academia.

This essay proposes that the values of humour and its constructions are valuable in not only the critical conversations surrounding Architecture but as a technique that could fold effects of spatial tectonics with affects. First, I examine the theories, concepts, and values of humour before turning to film as a lens to understand how humour is constructed. Applying these humorous constructs into studying various architectural projects, this essay speculates possible ways to create humorous architecture beyond satire or parody and that resonates through to an inverting intellectual level.

6 Humour in Architecture

Figure 1. (opposite page) Collage poster of absurd humour and all its proponents (Image by author)

7 Humour in Architecture Blank page

2. Humour 2.1. Theories and concepts

Humour is “that quality which appeals to a sense of the ludicrous or absurdly incongruous: a funny or amusing quality”.5 The use of the term “absurdity” within this thesis refers to “ridiculously unreasonable, unsound, or incongruous”6, not to be confused with “Absurdism” that deals with existentialism and nihilism.

One thing we perceive when confronted with humour is incongruity. The Incongruity Theory is the most widely accepted theory of humour, based off Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgement (2005) on our perception and reaction of the world with laughter as a bodily reaction to having our expectations disrupted into nothing.7 Incongruity stems from first having preconceived notions and expectations that are later, turned on its head. Laughter, then is “a form of psychological processing, a coping mechanism that helps people deal with complex and contradictory messages” 8. Arthur Schopenhauer elucidates that the perception of incongruity stems from the idea that we tend to categorise multiple real objects under a single cognitive concept that identifies them, the wider the contrast between the established concepts of the objects brought into a common understanding, the more humorous it would be9. Further expanded, that the resemblance cannot be too near each other for there will be no “delight or surprise” 10 –important aspects of humour.

But for the purposes of this architectural speculation, Noel Carrol describes a framework ripe for translation into an architectural ambition that hopes to utilise the ‘rapt attention’ gained from the occupant of such a construct. At once, humour acknowledges an established order while also breaking it, creating the space to play with our assumptions, and as Noel

8 Humour in Architecture

Figure 2 Congruity and incongruity: Surprise and delight occur when the red shape unexpectedly turns into The Spanish Inquisition30, also red but not a shape. (Diagram by author)

Carrol writes, becomes a ‘rehearsal and re-establishment of our concepts’, calling attention to our flawed thinking11. Its value then is seen in bringing contradicting subjects together, highlighting awareness by demonstrating the inverse and making complex topics more accessible.

Noel Carroll argues through the Neo-Jamesian approach to cognitive and perceptual theory that humour is an emotional state in which the incongruity that one perceives in life does not threaten them, allowing one to enjoy it instead, usually resulting in laughter as a bodily reaction and happiness as an emotional product.12 Establishing the atmosphere derived from humour to be one of joy and light-heartedness. Threat and safety come in with the Benign Violation Theory, where humour happens when the norm is violated or seems threatening but is simultaneously perceived safe (or benign).13 People only laugh when they are not threatened, or the subject of ridicule. Adapting the Maslov’s Hierarchy of Needs on human motivation, the Maslov’s Hierarchy of Humour structures required for humour to reach a higher cognitive potential (figure 3). Humour must first be within a safe space, physically and psychologically (deficiency needs), before incongruity is able to resonate through us as a physical and emotional reaction, to a cognitive level that amounts to an intellectual re-interpretation of our established concepts (growth needs).

9 Humour in Architecture

Figure 3. Benign Violation theory Venn Diagram by Peter McGraw: Where cancer is threatening and unfunny, reducing its threat to an unpoppable pimple is funny.

2.2. The Rejection of Humour

However, humour has a negative reputation, where it is brushed off as being purely for enjoyment and uncritical. The first writings of humour, by Plato, placed it as an unbecoming reaction14. Andrew Stotts examines comedy and its inability to hold standing within academia due to its being associated with plebeian culture and “thought to be local and vulgar, antithetical to the vision of art” prevalent in the medieval and renaissance periods. Its lack of a common foundational manifesto also leading to its reputation as nothing “serious”.15 Due to the lack of research into humour as a critical discourse, the value of humour in architecture was rarely discussed, with few writings or codifications on the subject.

2.3. Humour in Architecture (or the lack of it)

The few studies alluding to humour in architecture arose around postmodernist architecture, with works being critiqued as intelligent wit or farce. Postmodernism was ripe for the tool of humour due to its underpinnings in pluralism that considers and brings together the contradictions and complexities of a city and its people, trying to move away from the universal solution of modernist architecture,16 though not every manifestation would be considered humorous or amusing.

10 Humour in Architecture

Figure 4. Maslov’s Hierarchy of Humour (Diagram by author)

In Irony, Or the Self-Critical Opacity of Post Modern Architecture (2013), Emmanuel Petit wrote of humour in architecture in the form of irony, examining its expression of multiple meanings that usually signify the opposite, establishing architecture as “a form of thinking and interpreting that is eminently suited to deal with the many conceptual paradoxes that humans perceive in the world” and that this subset of humour as the dialogue between architecture and complex “world of humans (histories, memories, fears, emotions)”.17 However, theorists of irony tried to separate themselves from humour to gain an alleviated standing in academia, taking the discourse away from light-hearted humour.

Postmodern architect, James Wines, wrote of humour in his manifesto, De-Architecture (1987), where he considered the “use of humour and critique to initiate dialogue, the proposal of new relationships between art and architecture, and the expansion of narrative vocabulary”.18 His works culminated in the series BEST showrooms, in which the Indeterminate Façade (1975) served as a direct critical commentary against the homogenous aesthetics of modern architecture and the American commercial strip19. Its humour seen mainly in its symbolic crumbling façade, rather than with spatial experience. Both considered humour to be a means of communication for architecture with the complex world, yet it is not clear how humour could be constructed to invert perceptions in a safe space.

11 Humour in Architecture

Figure 5. Indeterminate Façade (1975), BEST Showroom by SITE

12 Humour in Architecture Blank page

3. How Films Construct Humour

3.1. Comedy: Planning Humour

Even with these theories, the formula for creating humorous architecture is non-existent, especially when the experience is spatial. Juhani Pallasmaa argues the similarity of architecture and film, that they “both define dimensions and essence of existential space; they both create experiential sense of life situations”20. Cues can be taken from the study of humour in film, as it successfully creates and reinvents humour and is closely studied in relation to the architectural experience. In Writing the Comedy Movie (2020), Marc Blake breaks down aspects of every comedic film genre into its constituents and structure, examining what it takes to construct humour in the narrative medium. Blake determines these methods in creating humour in film21:

Extraneous inclusion

Exaggeration

Inclusion of external genres or unrelated characters or props

Exaggerated scaling of things than they ought to be

3.2. Establishing knowledge through referencing

Incongruity in humour is having our expectations inverted. Therefore, it is required for the viewer to have preconceived expectations (or knowledge) or for the director to be able to establish it. This is done with techniques of referencing, in which information is delivered to the viewer and reiterated later to be inverted. In film, it is visual or auditory, as is the nature of the medium.

13 Humour in Architecture

Reiteration Creating similarity and difference Inversion Expectations are corrupted Misdirection Changes into unexpected realms

Table 1. Methods of creating humour in film from Writing a Comedy Movie (2020)

The film Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), or EEAAO, contains humour that is complex and inverting. Considered a comedy film, it has been lauded with accolades and reviews, showing that its humour goes beyond parody, cliché, or camp (subsets of humour that have a more negative perception due to their surface-level inversions) 22. The directors (The Daniels) manage to incorporate the aforementioned methods to not only break the academic lens in which most audiences perceive films23, but achieve a film that inverts notions of existentialism and film. Its construction of humour involves tapping on existing knowledge or establishing new ones and then referencing them. Here, I break down the construction of humorous scenes, in three categories of referencing in which the subject is different in each: (1) cross-referencing, (2) external referencing, (3) self-referencing.

3.2.1. Cross-referencing

Cross-referencing are scenes that reference scenes or narratives established previously within the film. In an early sequence, a kung fu master tells the protagonist, “even this cookie can be kung fu”, telling her that even she can become a kung fu fighter, making this a motivational speech. At 45:49 the scene is directly referenced again, setting the exact scene back up but instead of a motivational quote, the kung fu master establishes a literal rule of kung fu, that “even this pinky can be kung fu” and we see an exaggeration of the pinky’s strength to a humorous effect.

Here we see film language used to create this cross-referencing, in which the exact framing of a subject is used to clearly anchor the audience within the kung fu world’s logic and immediately inverting the meaning and expectations of the dialogue There is the reiteration of a scene and an inversion of expectations.

14 Humour in Architecture

15 Humour in Architecture

16 Humour in Architecture

Figure 6. De-constructing the kung-fu pinky in EEAAO (Drawing by author)

3.2.2. External referencing

EEAAO is notable for its use of different genres and famous film scenes to convey different meanings throughout the film. Daniel Kwan, the director, reflected that “movies are the language that so many people speak and think in these days,”24 These references to other films show the inherent ideas we place on different films and genres and how they hold meaning and symbolism that many people can identify due to film’s widespread reach. They can be, like Schopenhauer postulates, brought together under one concept to create a humorous (due to the incongruity of film forms) but more impactful and immediate dialogue. An example of these humorous insertions is the inclusion of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s “The Dawn of Man” to immediately establish the absurd change in the evolution of mankind to have sausagelike fingers in EEAAO. The film is directly referenced in subject, style and sub-plot, showing only the inversion of evolution to sausage-handed apes. (figure 7 & 8)

17 Humour in Architecture

Figure 8. The scene in EEAAO where the sausage-fingered ape kills the normal ape, signifying a change in the evolutionary strain

Figure 7. The original Dawn of Man from 2001: A Space Odyssey

3.2.3. Self-referencing (Meta referencing)

The “self” refers to the film beyond the screen, the perception of film as a medium. The Daniels uses the audience’s very established notions of how films progress to invert expectations and allow the film to expand into absurd proportions, breaking out of these filmic structures. Below, we see the narrative structure and temporal elements that the Daniels bring our attention to and how they subvert it.

Midway, after a climatic fight the protagonist “dies”, the credits roll, displaying the end title card and even naming the directors. In doing so, the audience’s expectation of a resolution is disappointed, but their sense of film timing is brought out of subconsciousness, and they realise that this credit roll is not real and is inverting the film’s structure to form a new narrative.

18 Humour in Architecture

Figure 10. End credits in the middle (1:25:09) of the film (Source: Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022)

Figure 9. The Incongruous structure of EEAAO. Referencing the in-built structure and time of films we hold in our minds.

(Diagram by author)

These different methods used in film not only elicit laughter but break preconceived ideas of films and narratives. They are inverted, redirected, and exaggerated in order for wider relationships beyond the film to connect. How directors craft and use humorous scenes where aspects of film (cinematography, editing, sounds and narrative, etc.) can be translated into architectural operations so that the architect can, like a director, control these elements to construct 3-dimensional humorous spaces is examined. It is important to note the use of a narrative plot as a thread in which the logical and illogical can attach itself before they become unrelated nonsense with incongruity that does not help cognitive reconnections.

19 Humour in Architecture

Table 2. Translations from film elements into architecture elements into its respective type of drawings (Table by author)

4. Humorous Architecture

4.1. Techniques of Architectural Referencing

From the study of the construction of humour in film, it is now easier to see how these techniques present themselves in existing architectural projects that are not necessarily humorous but demonstrate spatial techniques that create incongruity in our mental processes when experiencing spaces through different forms of referencing. Walter Benjamin states that architecture is mainly perceived in distraction, rather than visual concentration, and that the masses understand architecture, not through optical contemplation, but through tactile appropriation - gained through habits formed in a space.25 Referencing thus becomes an important technique to bring these habitual understandings that sit in the background of our cognitions to the fore, allowing the initial step of establishing knowledge or bringing attention to it to occur.

The following case studies were chosen for their potential ability to show incongruity in the visual field, spatial experience, and mental constructs in architecture. They parallel the different methods of creating humour: reiteration, inversion, misdirection, extraneous inclusion, and exaggeration.

4.1.1. Case Study #1: Serralves Museum, Alvaro Siza

The Serralves Museum (1999) by Alvaro Siza is not a humorous building but demonstrates effective referencing using specific frames and the garden around the site to draw one’s attention to the external garden setting but also as a guide to the adjacent gallery spaces. These framings become starting points of diverting attention or ‘establishing a new knowledge’, like how humour focuses our attention to something at the start and then references it later to achieve a humorous effect. Like a film director, Siza adjusts the architectural elements of his work to divert our attention demonstrating how referencing could be done through more spatial techniques, such as windows, repeating walls, rhythm, columns, and projected shadows that help frame distant spaces to reiterate the museum’s place in the garden.

20 Humour in Architecture

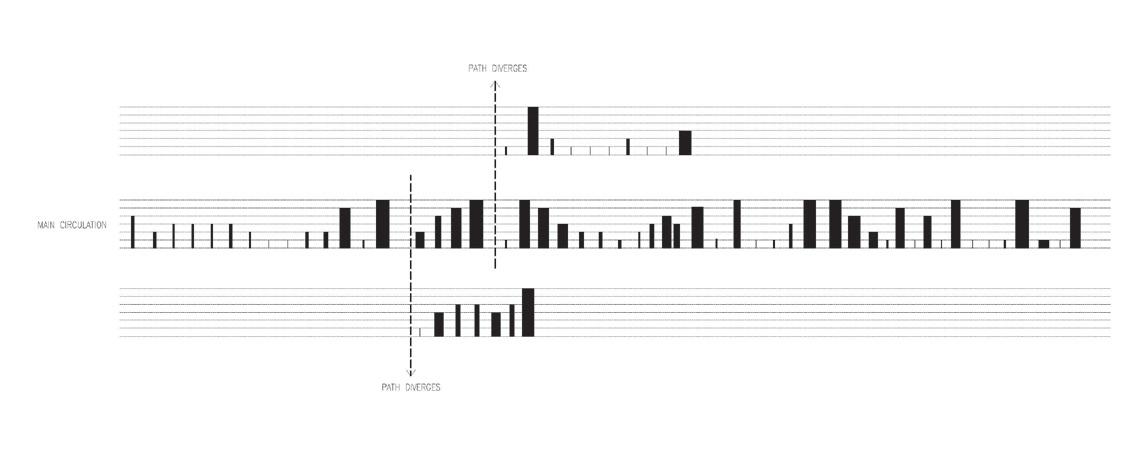

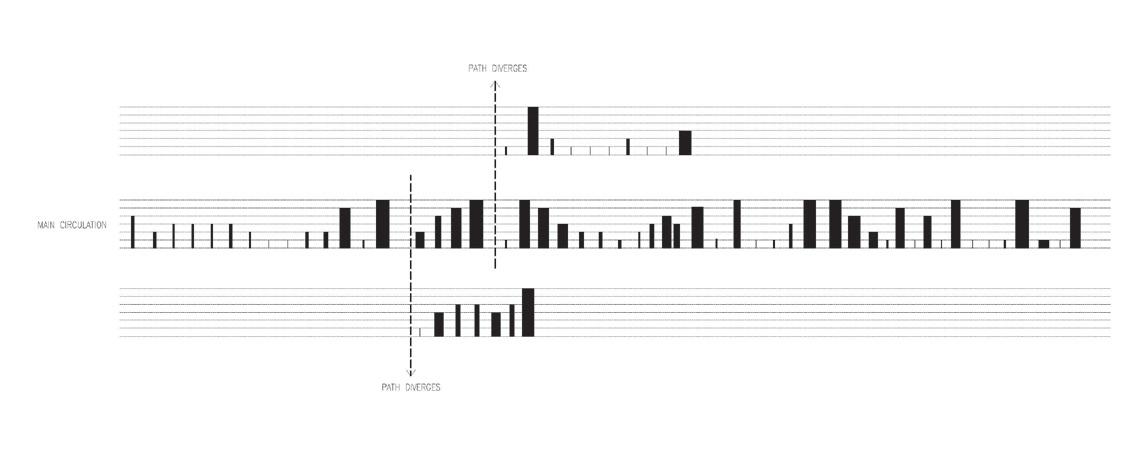

This mode of referencing helps with creating humour in the form of reiteration and extraneous inclusion, allowing for things inside and beyond the site to be referenced throughout the building. It also shows the rhythm in which these diversions appear, in which spaces with larger visual change and variances occur at diverging paths and always in gradual punctuations.

21 Humour in Architecture

22 Humour in Architecture

Figure 13. Rhythm of visual variance through Serralves Museum (Drawing by author)

Figure 11. (opposite page, top) Visual depths, variance and changes throughout the Serralves Museum L1

Figure 12. (opposite page, bottom) Visual depths, variance and changes throughout the Serralves Museum L-1

LEGEND

4.1.2. Case Study #2: Sainsbury Wing, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown

Venturi Scott Brown Architects’ (VSBA) National Gallery Sainsbury Wing, London (1991) is an extension to the Neoclassical National Gallery built in the 1830s to house the gallery’s Italian and Northern renaissance paintings. Humour is immediately found in the approach of the wing: off to the side and a third of the original gallery’s size, it seems like an unassuming side entrance, leading into a compressed and dim foyer, inverting the entrance experience of museums that are grand and large. The experience further enhanced with the addition of a “façade-scale Portland stone rustication” making the foyer seem as though it is underground.26

Humour is demonstrated in the reiteration of the original building’s Corinthian columns on its main façade but disrupted in rhythm to an extreme ‘echo’ and replicating only one of the round columns (figure 8). This visual incongruity due to its messy rhythm and out of place single round column highlights the double meanings of the columns as structure and aesthetics and inverting our expectations of functional structures as functionless

23 Humour in Architecture

Figure 14. Corinthian columns found on the original National Gallery Building

aesthetics. There is safety as it does not impede or cause inconvenience to the visitor. The façade demonstrates an architectural move of referencing its external context while also inverting ideas on structure in the discipline bringing contradicting subjects together, especially that of a complex site.

The Sainsbury Wing also demonstrates a spatial method of referencing in its framing of The Mond Crucifixion (Raphael, 1502-1503). This deals with visual attention and its resulting mental attention to the painting while walking through the gallery. The first interaction with The Mond of Crucifixion makes it seems like one of many paintings in the gallery’s third section, quietly inputting its existence into the viewer’s mental space. VSBA then directs all attention away from it as one walks through the gallery and other paintings make it fade into the background. The painting is then brought back into full focus (referenced back) as one turns the last corner, and sees it framed by multiple archways. The walk back to the painting is one that misdirects its focus to other painting in other sections, while keeping its existence constantly in mind through its framing. Finally pulling the viewer back to confront the painting again. (figure 16-19)

24 Humour in Architecture

Figure 15. The absurd rhythm of the Sainsbury Wing’s Corinthian “columns” that fade as it turns the corner

25 Humour in Architecture

Figure 18. Diagram of attention to The Mond Crucifixion (15021503) as one walks through the Sainsbury Wing Gallery (Drawing by author)

Figure 17. Rhythm of visual variance through the Sainsbury Wing gallery (Drawing by author)

Figure 16. Plan of the National Gallery Sainsbury Wing. The circulation in relation to The Mond Crucifixion. (Drawing by author)

26 Humour in Architecture

Figure 19. The Mond of Crucifixiondirecting focus and attention

4.1.3. Case Study #3: House VI, Peter Eisenman

House VI (1975), part of Eisenman’s series of experimental houses, focusing on the “transformational process” of shifting two volumes, containing multi-layered inversions in function and cognition. Starting with the design process, Eisenman plays with the grid and cube, creating twin cubes, one that is situated within the “normal rules of tectonics” and the other, an inverted cube that counters them27, resulting in inversions of structures and columns where some do not touch the ground, or they form column clusters that do not make functional sense. Their incongruity in function draws our attention and rewires our expectations of structure in the house – that columns are mainly structural.

While calling attention to physical elements of architecture, the home also “specifically opposed some of the users’ assumptions of ‘normalcy’ “28, creating incongruity of the home and its attached programmes through disruptions in expected scale, size, shape, and location of specific rooms in a house. For example: upon entry, one is confronted with the narrow dining room, demarcated by columns, that barely fits within the space, with one column becoming one of the diners, another disruption occurs in the bedroom, cut in half by a strip of glass, forming an invisible

27 Humour in Architecture

Figure 21. The glass that splits the master bedroom and the couple’s bed

Figure 20. Cluster of columns in House VI that do not make structural sense

plane and the couple’s bed resultantly split in two, forced to separate. This inversion in expectations seen in the comparison with Neufert’s standards for programmes (figure 22 & 23), show how a small inversion, like softly dividing a space, affects the programme and forces a lifestyle adaptation, highlighting societal norms attached to the space.

Eisenman noted these cognitive shifts:

“This mental attempt to reorder the elements is triggered by their precise size, shape, and juxtaposition. This produces a sense of tension or compression in a particular space that is not created through the actual position of walls but is in our conception of their potential location. The sense of warping, distortion, fluctuation, or articulation occurs because of the mind’s propensity to order or conceptualize physical facts in certain ways, like the need to complete a sequence A-B or to read symmetries in a straight line.”29

House VI’s critical humour references established architectural preconceptions of space and programme of a house, showing the affective links between the construction of space and societal conceptions of programmes and typologies (e.g., one bed in the master bedroom for a married couple), through physical disruption to spaces.

28 Humour in Architecture

Figure 23. (right) Neufert’s standards for a bedroom layout

Figure 22. (left) House VI plans showing the split in the bedroom caused by the glass

4.2. Synthesis of Humorous Architecture

These case studies show the possibilities for constructing humour in architecture, with the methods of referencing and inversion being a requirement for creating incongruity. Being able to choreograph attention - to direct or misdirect - is important in knowledge formation in humorous architecture and is shown in the Sainsbury Wing and Serralves Museum’s techniques of framing and circulation. Spatial and physiological experience of space is also referenced in the last two case studies where they play with the expectations of spaces through transforming scale and programme. In the Sainsbury Wing and House VI, humour can bring out double meanings in architectural elements under one conception: Functioning structure, order and aesthetics are brought under the physical form of a column. Scale, thresholds, programmes, and societal norms are questioned in an incongruous room.

29 Humour in Architecture

5. Conclusion

Humorous architecture brings the contradictions of life together, highlights our awareness of space, and makes the multi-layered complexities of architecture more accessible, but is rarely discussed critically in architecture, or made into a tool of constructions of spaces that resonate through our understanding of architecture and the society that shapes it. Understanding humour in popular media such as films, create a lens for looking at existing hidden constructs of humour within architectural projects. Using operations to create visual referencing is important in knowledge formation and can form effective visual connections between different programmes and typologies. Following the adapted Maslov’s Hierarchy of Humour as a base for humorous architecture, basic safety, where the user does not feel like the subject of an architectural joke, must be achieved before humour can be effective. Considering also that programmes and typologies are loaded with their own preconceived set of expectations and atmospheres, the design of safety of judgement can be tied to programmes and altered in ones perceived as unsafe.

From the architectural projects discussed, effective humour in architecture resonates through to an intellectual re-enactment of our established concepts. It is the opposite of the horizontal consistency of aesthetic compositional consistency or accepted norms of compositions. Instead, humorous architecture resonates through many different aspects at different scales and various effects, re-establishing ideas from structure to programmes to societal notions that shape architectural typologies.

(Another product of this research into humour was the tendency for me to write informally as a result of reading and researching books on humour that were themselves always written in an informal manner.)

30 Humour in Architecture

i. References

1 Stott, Andrew McConnell. Comedy. Routledge, 2014.

2 Petit, Emmanuel. Irony, or, the Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013, 18.

3 Morreall, John. “Philosophy of Humor.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, August 20, 2020. https://plato.stanford. edu/entries/humor/.

4 Wilund, Jean. “The Difference between Comedy and Humor.” Almost An Author, February 26, 2017. https://www.almostanauthor.com/thedifference-between-comedy-humor/.

5 Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “humor,” accessed October 11, 2022, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/humor.

6 Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “absurd,” accessed October 11, 2022, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/absurd.

7 Kant, Immanuel., & Bernard, J. H. Critique of judgment. Dover, 2005, 131.

8 O’Hara, Mary. “How Comedy Makes Us Better People.” BBC Future. BBC, August 30, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20160829-howlaughter-makes-us-better-people.

9 Schopenhauer, Arthur. The world as will and representation. (J. Norman, A. Welchman, & C. Janaway, Eds.) (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press, 2010, 50.

10 Stott. Comedy, 130.

11 Carroll, Noel. Humour a Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. 2014, 78.

12 Carroll. Humour a Very Short Introduction, 77.

13 McGraw, Peter, and Joel Warner. The Humor Code: A Global Search for What Makes Things Funny. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2015, 75-76.

31 Humour in Architecture

14 Morreall. “Philosophy of Humor.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2020.

15 Stott. Comedy, 23-24 & 37.

16 Jencks, Charles. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. United States of America, New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1977, 101.

17 Petit, Irony, or, the Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture, 24.

18 Wines, James. De-architecture. Rizzoli International Publications, 1987.

19 “Best Products Company Buildings.” SITE. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://sitenewyork.com/portfolio-1/project-one-7tnzy-llznb-83lxp6xw4p-726sh-k86c6-7l6se?rq=best.

20 Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Architecture of Image: Existential Space in Cinema. Helsinki: Rakennustieto Oy, 2001.

21 Blake. Writing the Comedy Movie, 95-96.

22 “And the Winners of the 5th Annual HCA Midseason Awards Are....” Hollywood Critics Association. Accessed October 12, 2022. https:// hollywoodcriticsassociation.com/and-the-winners-of-the-5th-annualhca-midseason-awards-are/. “For the first time in its five-year history, one film, Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s Everything Everywhere All At Once, took home the top prize in every category the film was nominated in.”

23 Robinson, Tasha. “Yes, the Directors of Everything Everywhere All at Once Are Trying to Destroy Your Brain.” Polygon. Polygon, April 12, 2022. https:// www.polygon.com/23021092/everything-everywhere-interview-danielkwan-daniel-scheinert-daniels.

24 Tasha. “Yes, the Directors of Everything Everywhere All at Once Are Trying to Destroy Your Brain.”

25 Benjamin, Walter. “XV.” Essay. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 34–35. New York, NY: Prism Key Press, 2008.

26 Furman, Adam Nathaniel. “Ad Classics: Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery London / Venturi Scott Brown.” ArchDaily, October 3, 2018. https://www. archdaily.com/781839/ad-classics-sainsbury-wing-national-gallery-

32 Humour in Architecture

london-venturi-scott-brown.

27 Petit, Irony, or, the Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture,157.

28 Petit, Irony, or, the Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture,159.

29 “House VI 1975 - Eisenman Architects.” EISENMAN ARCHITECTS. Accessed October 18, 2022. https://eisenmanarchitects.com/House-VI-1975.

30 “The Spanish Inquisition” was a 1971 comedic sketch from the British comedic troupe Monty Python. The sketch involves the sudden and unrelated appearance of the Spanish Inquisition, while announcing “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!” The surprise entrance of the Spanish Inquisition is repeated again and again due to constant mistakes made in their monologue, making their entrance exclamation paradoxical and increasingly ridiculous. Also creating a popular culture reference that uses the phrase “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition”, in the most unrelated situations.

33 Humour in Architecture

On Humour

Bergson, Henri. “Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic.” The Project Gutenberg E-text of Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic, by Henri Bergson. The Project Gutenberg, July 26, 2009. https://www. gutenberg.org/files/4352/4352-h/4352-h.htm

Chapman, Antony J. It’s a Funny Thing, Humour International Conference on Humour and Laughter, Cardiff, Wales, 13 - 17 July, 1976. Oxford u.a.: Pergamon Pr, 1977.

Freud, Sigmund, James Strachey, Anna Freud, Alix Strachey, and Alan Tyson. Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis, 1968.

Meredith, Michael. “For the Absurd.” Log, no. 22 (2011): 7–15. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/41765702.

Rovic, Ivana. “These Pretzels Are Making Me Thirsty: 920 Grams of Architectural Humour.” CURVE. Dissertation, Carleton University, 2019. https://curve. carleton.ca/cf79f92f-73f7-4e04-ae25-4f6e23bbc371.

Szczegielniak, Anna. Thesis. “Why So Serious?” – The Joke As A Means Of Expression In Architecture. Thesis, Opole University of Technology, 2015. https://suw. biblos.pk.edu.pl/downloadResource&mId=1683960.

van der Velden, Daniël, and Vinca Kruk. “Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? Memes, Design and Politics”. METAHAVEN. Strelka Press, 2014.

Zacharopoulou, Katerina. “In the Scale of a Joke.” In the scale of... A gesture, a discourse, a joke. Canadian Centre for Architecture . Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/85415/in-the-scale-of-agesture-a-discourse-a-joke.

On Architecture

Brown, Patricia L. . “What Exactly Is ‘De-Architecture’?” The New York Times. The New York Times, December 3, 1987. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/12/03/

34 Humour in Architecture

Bibliography

ii.

garden/currents-what-exactly-is-de-architecture.html.

Evans, Robert. Translations from Drawing to Building. In Robin Evans: Translation from drawing to building and other essays. London: Architectural Association. 1997.

Hicks, Stewart. “What’s Behind Architecture’s Hidden Humor.” YouTube. YouTube, October 14, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhC9EKGa62g&am p;t=147s&ab_channel=StewartHicks

Jencks, Charles. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. United States of America, New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1977.

Tschumi, Bernard. The Manhattan Transcripts. London: Academy Editions, 1994.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and Contradition in Architecture. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1998.

Loughrey, Clarisse. “Everything Everywhere All at Once’s Multiverse Leaves Marvel in the Dust – Review.” The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, May 14, 2022. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/ films/reviews/everything-everywhere-all-at-once-review-uk-b2079094. html.

James, Fredrick. “How ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’ Subverts the Action Movie Climax.” Collider, June 7, 2022. https://collider.com/everythingeverywhere-all-at-once-subverts-action-movie-climax/.

Kirby, Ben. “Film Studies 101: A Beginner’s Guide to Aspect Ratios.” Empire. Empire, May 1, 2014. https://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/filmstudies-101-aspect-ratios/.

Kwan, Daniel, and Sheinert, Daniel, directors. Everything Everywhere All At Once. 2022. A24, 2022. 2:19:19. Digital file.

35 Humour in Architecture

On Film