Since the dawn of civilization, we could only look up to the heavens. The space pioneers of the 1960s harnessed new rocket technology to break the bonds of gravity and allowed us, for the first time, to look down at Earth and truly consider our place in the universe.

Project Mercury was NASA’s first human spaceflight program. It operated from 1958 to 1963 and its objective was to put a man into orbit and return him safely to Earth, ideally before the Soviet Union. In addition to many uncrewed test flights, six one-man Mercury missions were successfully completed. Project Gemini then took over and continued until 1966. Its objective was to test new hardware and develop spaceflight techniques that would be necessary to allow the U.S. to reach for the Moon, before the end of the decade, with Project Apollo. The ten two-man Gemini missions were conducted at a remarkable pace – all taking place between March 1965 and November 1966.

Despite the unique vantage point and extraordinary views promised during the very first human spaceflights, NASA didn’t fully embrace space photography as it risked being a distraction for the men they had selected to make these bold new ventures into the unknown. It wasn’t even clear how the human body would cope with the rigors of spaceflight, and the astronauts had enough mission- critical activities to focus on during their short, groundbreaking voyages. Their tiny capsules weren’t conducive to storing, preparing and operating additional equipment. One of the first Soviet space travelers, Alexei Leonov, strapped a small set of colored pencils to his spacesuit in order to capture the spectacular display of an orbital sunrise, so that he could share his privileged viewpoint with the world upon his return. And so it was often the astronauts themselves who pushed the case for photography to record their cosmic observations.

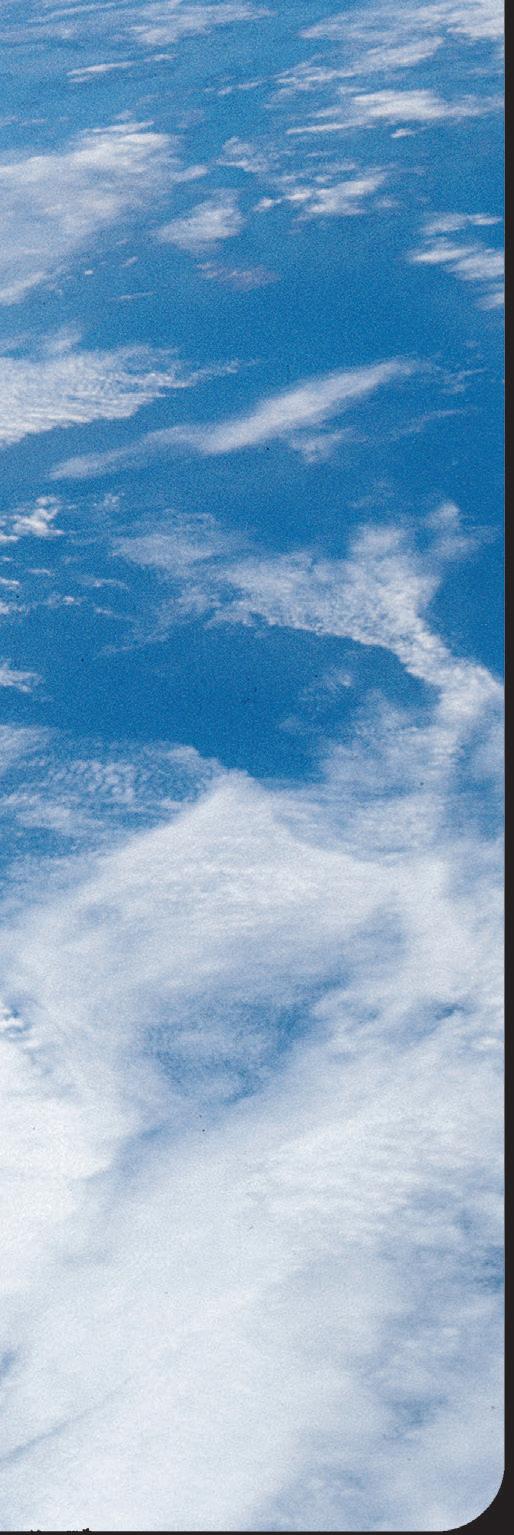

When an early NASA memo summed up its initial apathy (“If an astronaut desires, he may carry a camera”), some purchased their own, basic equipment. With these hastily adapted cameras, and little photographic training, they captured some of the first ever tantalizing views of the curvature of Earth from space, through the small windows of their ships. And when John Glenn lifted his camera to his window, during the first U.S. orbital flight, he took the first photographs of sunrise and sunset from above the atmosphere. NASA’s appreciation for space photography developed throughout the programs, and on the later Gemini missions, with more time and space, better equipment and training, and from altitudes way beyond those experienced today on the International Space Station, these early human space explorers returned some of the finest imagery of our home planet ever captured on film.

For the first time we were able to look back at Earth, experiencing the “overview effect,” the cognitive shift that elicits an intense emotional experience upon seeing our home planet from space for the first time. The film returned by these first astronauts is some of the most important and valuable in existence. Although copies were made, NASA was slow to appreciate the intrinsic value of the original film, even scribbling frame numbers and other information over it with felt pen, and much of the early film shows signs

of inappropriate handling and storage. As time progressed, the importance of the originals became more apparent and they were secured in a frozen vault, in Building 8 at Johnson Space Center, Houston, to help maintain their condition. Over the six decades since, almost all of the images seen by the public from this pivotal era in our history, have been copies of master duplicates, or copies of copies, leading to gradual degradation in the quality of the images we see. In recent years, however, the “holy grail” – the original flown film – for each mission has been removed from the freezer, thawed, cleaned, and digitally scanned.

There is a treasure trove of almost 5,000 photographs from Project Mercury and Project Gemini. Since they were taken in an era when photography was purely analog – requiring light-sensitive chemistry, film and paper – digital scans of the transparencies need additional digital processing to bring out their hidden details. The images in this book are derived from the new, raw scans of the original flight film. I have digitally restored and remastered them using image- enhancement technology and techniques, to present them in unprecedented detail and clarity. Having inspected all 5,000 frames in NASA’s archive, I have selected images based on those which most effectively represent the Mercury and Gemini programs, and of our first forays into space.

On the very first flights, during Project Mercury, 16mm “movie” cameras were integrated into the capsule’s instrument panel. These “Pilot Observer” cameras captured the astronauts, inside their tiny cockpit, during every phase of their trailblazing mission. During Project Gemini, the 16mm cameras were pointed through the windows to capture key sequences of events, such as vehicle rendezvous and docking, for technical assessment, or the astronauts’ spacewalks, to assess how effectively a man could operate out in the void of space. Their wider angle lenses also captured brief moments inside the spacecraft. Despite the captivating glimpses of such historic events afforded by the 16mm cameras, the footage suffers from comparatively more noise and a lack of detail inherent in smaller-format film. Some of the film was also severely damaged by water ingress as the capsules splashed down in the ocean.

I have undertaken a rigorous and transformative process to restore and enhance this footage and included the results alongside the still photographs. I have applied an image-stacking technique, often employed in astrophotography, to the highest- quality, uncompressed HD digital transfers of this film. Over recent years, I have developed a process to also apply this principle effectively to more dynamic scenes. As many as several hundred separate frames are stacked, aligned and processed to produce a more photo-like output, revealing detail that had been lost for 60 years. I have inspected the source film in its entirety, in places frame by frame, to identify key detail. The innate desire to see inside the first spacecraft that lifted us out of our cradle to explore the unknown and to observe life aboard these most historic journeys drove my selection. Here you will find scenes well suited to the stacking technique, those that reveal significant historical moments, or that create a sense of intimacy, or those that reveal fascinating details of the spacecraft interior

with its myriad analog dials and switches. Not only can we now clearly see what the first astronauts observed from their heavenly perspective, but we can see the explorers themselves, as they undertake some of the most daring and important voyages in our history.

I have used mission transcripts of air-to-ground voice transmissions and onboard tape recordings, flight reports, indicators in the imagery, and astronaut interviews to reconstruct every mission. As such, within each chapter, but for a few exceptions, I have made every effort to present the images chronologically. I have attributed credit to the appropriate photographer, outlined the content conveyed, and included pertinent quotes from those who were there at the moment the images were captured, in order to add context and perspective to the scene and to help better comprehend what it would be like to witness the events first hand. Following the images and captions in sequence tells not only the story of each mission, but also the whole progression from our first ever glimpses of the curvature of Earth, through to learning all of the key spaceflight techniques required to enable the Apollo program to take the next giant leap and reach for the Moon. These techniques are still used during spaceflight today – Mercury and Gemini paved the way.

The photographs taken throughout the programs were of immense scientific value. Although the cameras and photographers were viewed more as simple data recorders and scientific tools, they captured images of striking beauty that transcend documentation. My aim here is to present the best of the thousands that were captured, in the greatest detail and clarity attainable, so that we may better comprehend the endeavor and imagine making the incredible journeys ourselves. The imagery and captions also present the opportunity to recount some of the remarkable human stories and human drama that unfolded during these bold missions, as the U.S. and the Soviet Union vied for supremacy in space. The first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, described his mission as an unprecedented, single-handed, “duel with nature.” It was the broader duel between East and West that drove technological developments at an extraordinary pace. Project Gemini averaged a flight every two months, for almost two years. Each groundbreaking mission built on the last; pushing the limits of technology and the extremes which the human body could withstand in order to effectively function in the hazardous, inhospitable environment beyond Earth’s protective blanket.

These first men who boldly ventured into the black void of space in their tiny, rudimentary capsules were rewarded with the breathtaking views of Earth only dreamed of since humans first looked to the heavens. They witnessed the true beauty and fragility of our home planet, the cradle of civilization, from a cosmic vantage point. The photographs returned by the astronauts are a poignant reminder of this golden era of exploration, and that the beauty of science, and of discovery, transcends generations and political divides. Thanks to the remastered film, we can now join them on their voyage into outer space, witness their “duels with nature” and peer out of the small window of their spacecraft.

MR- 3

Redstone (No. 7)

No. 7 “Freedom 7 ”

14:34 GMT, May 5, 1961, LC-5

303 miles

15 minutes 22 seconds

Suborbital

N/A

117 miles

14:49 GMT, May 5, 1961, Western Atlantic USS Lake Champlain

MISSION

ROCKET

CAPSULE

LAUNCH

DISTANCE

DURATION

ORBITS

MIN. PERIGEE

MAX. APOGEE

SPLASHDOWN

RECOVERY SHIP

Alan B. Shepard Jr.

MR- 3

Born November 18, 1923. Before being selected as one of the “Original Seven,” Shepard was a naval aviator and test pilot. He would have become Command Pilot on the first Gemini mission, but was grounded due to an inner- ear problem. A surgical correction in 1969 restored his flight status and, at age 47, he walked on the Moon as Commander of Apollo 14.

MR- 4

Redstone (No. 8)

No. 11 “Liberty Bell 7 ”

12:20 GMT, July 21, 1961, LC-5

302 miles

15 minutes 27 seconds

Suborbital N/A

118 miles

12:36 GMT, July 21, 1961, Western Atlantic USS Lake Champlain

Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom

MR- 4

Born April 3, 1926. Grissom was a Korean War veteran and U.S. Air Force test pilot. He later became the first man to fly in space twice when he served as Command Pilot of the first crewed Gemini mission. After Gemini, he was selected as Commander of Apollo 1, but was tragically killed along with crewmates Ed White and Roger Chaffee in a ground test in 1967.

May 5, 1961–July 21, 1961

After the Soviets launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik, on October 4, 1957, the U.S. followed with a series of embarrassing failed attempts to launch their own. Although the U.S. had plans to put a man into orbit, they were lagging well behind the Soviets, as more rockets failed or exploded during test flights in front of the world’s media. They could still beat the Soviets to making a suborbital flight though, putting the first man into space. On April 12, 1961, however, Yuri Gagarin made a successful orbit of Earth on Vostok 1. The news was devastating for Americans and for the astronauts. Shepard was furious, but just three weeks later it was time to restore some U.S. pride.

By coincidence, capsule no.7, on rocket no.7, would launch the first of seven planned Mercury flights for the seven astronauts. Shepard suggested his own call sign – “Freedom 7,” and on May 2, fully suited, he waited in Hangar S, to be driven to the launch pad. Only when bad weather postponed the flight did Bob Gilruth inform the public of the true identity of America’s first astronaut. By May 5 the weather improved. Shepard was awakened at 01:10, had a breakfast of steak, scrambled eggs, and orange juice, then was helped into his space suit. At the pad, he stepped from a trailer into the dark as searchlights illuminated his Redstone rocket. Flight Director Chris Kraft felt a wave of excitement as Shepard looked up at the rocket; light reflecting off his silver suit – he looked like a spaceman. Shepard entered the capsule at 05:20, to a chorus of “Happy landings, Commander!” from the gantry crew.

The atmosphere in Mercury Control was palpable, as Kraft made a final poll of his team – he was shaking so hard he couldn’t see his own microphone and thought it had fallen off. He leaned on his console with both hands to settle himself, and each position confirmed, “GO, Flight.” The 15minute mission had the primary objective of demonstrating a man’s ability to withstand the g-forces of launch and re- entry. Shepard also observed Earth and tested the capsule’s attitude control system. As the flight progressed perfectly, Public Affairs Officer “Shorty” Powers catapulted a new

word into the American lexicon: “The astronaut reports that he is A - OK .” After testing the retrorockets that would return later missions from orbit, Shepard landed safely in the Atlantic.

Impressed with how the world reacted, just 20 days later, on May 25, Kennedy delivered a speech to Congress, in which he put forth an astonishing mandate: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

Gus Grissom’s MR- 4 flight followed a similar suborbital profile, but his Liberty Bell 7 capsule (he retained the “7” for his call sign) had some improvements, including a window above his head and an explosively actuated hatch. The flight went to plan until Grissom splashed down, 300 miles east of Cape Canaveral. There, Grissom’s recovery went horrifyingly wrong, as the hatch prematurely blew and water poured into the spacecraft.

The cause of the incident is one of NASA’s most enduring mysteries. Doubt was cast on Grissom’s insistence that the hatch blew of its own accord. Many, including the media, blamed him. He was never able to truly clear his name before tragically losing his life in the Apollo 1 fire in 1967. NASA’s investigation was inconclusive. Wally Schirra spent hours in a capsule, attempting to hit the detonator ‘accidentally’ but couldn’t. The only way was hammering the detonator with 6 pounds of force. This always left a bruise to the hand – a bruise Grissom didn’t have.

Working with Grissom biographer George Leopold, my photographic analysis of the recovery film that follows corroborates the post-flight statements of the recovery helicopter co-pilot John Reinhard. He stated that the hatch blew at the moment he saw an electric arc when snipping the whip antenna. The electrostatic discharge inadvertently set off the pyro squibs in his cutter, and likely Liberty Bell 7’s hatch. The pilot, Jim Lewis, had always countered that the hatch had blown earlier, but after seeing this analysis, finally agreed with Reinhard. If correct, this explanation of events finally exonerates Grissom, 60 years after the flight.

No hand-held camera was taken on MR-3. Views were restricted to two 10-inch porthole windows. A Maurer 220G time-lapse camera pointed out of the lower right-hand porthole, via a mirror attachment, and took photographs every 6 seconds. Since no film camera was on board Vostok 1, it took the first ever photographs of Earth from a human spaceflight. Inexplicably, the original film was annotated with felt pen post-flight, but is presented here with the inscriptions digitally removed.

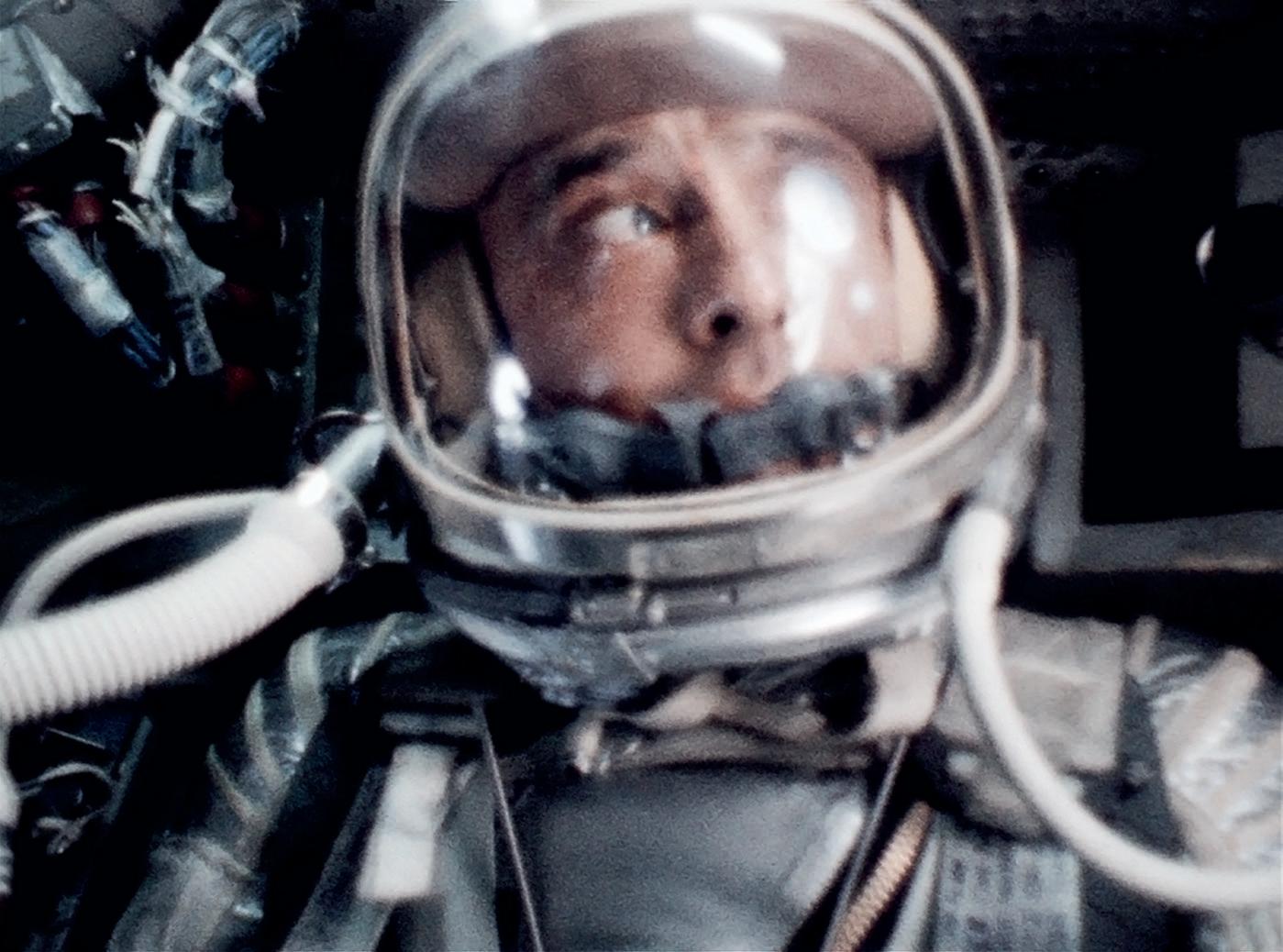

A Milliken 16mm “movie” camera was used as an “Instrument Observer” camera, and another, mounted in the control panel, as a “Pilot Observer” camera. Stacking and processing hundreds of frames from this camera allows us to see Shepard during this historic flight in unprecedented detail.

As Liberty Bell 7 was lost to the ocean, so too was the onboard film. It is the only U.S. human spaceflight not documented with photography.

May 5, 1961 / gmt 13:30* to 14:26* / Suborbital

79 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED

Calls of nature during extended pauses hadn’t been considered and Shepard wanted to exit the spacecraft to urinate, but decided to relieve himself into his suit after requesting the power to his bio-med sensors be turned off first, to avoid a short. At T minus 2 minutes 40, Shepard heard the dreaded word again, “Hold.” The computer at the Goddard Center in Maryland needed a reboot. He exclaimed, “I’ve been in here more than three hours. I’m a hell of a lot cooler than you guys. Why don’t you just fix your little problem and light this candle!?”

NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG MR-3. “Light this candle.” Alan Shepard is strapped into his Freedom 7 capsule, atop the MercuryRedstone rocket at Launch Pad 5, waiting to make history as the second human, and first American in space. His heart rate quickened as the hatch was closed and bolted shut at 10:20 GMT (05:20 local time). Launch was expected at 12:20 GMT, but as clouds rolled in, there was a pause to wait for better photographic conditions. An electrical part also had to be replaced on the Redstone rocket, causing further delay. Shepard passed the time looking through the capsule’s periscope.

May 5, 1961 / gmt 14:34* / Suborbital 16 AND 560

May 5, 1961 / gmt 14:35* to 14:36* / Suborbital 140 AND 59 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED AND MAURER 70MM (AUTO- TIMER) NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG AND 13012- 045

MR-3

Top left: “OK, it’s a lot smoother now.” MR-3 had just passed through maximum dynamic pressure at 1 minute 24, which caused his helmet to shake so violently that he couldn’t read the instrument panel. After hitting a maximum load of 6.3g, engine cut-off occurred at 2 minutes 22 – Freedom 7 was traveling at 5,157mph. He heard the escape tower jettison, then: “Capsule

Separation is green . Periscope is coming out and the turn-around has started.”

Bottom left: Shepard then tested manually maneuvering the capsule in space. Right: The first still photograph taken from space, on a human spaceflight. As Freedom 7 turned around, NASA’s definition of the boundary of space (50 miles) had been crossed, Shepard: “What a beautiful view!”

May 5, 1961 / gmt 14:42* / Suborbital

104 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED

NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG MR-3 Freedom 7 continued to coast up to an apogee of 116 statute miles, five minutes after launch. 30 seconds later, retrorockets slowed the spacecraft for re-entry, Shepard: “All three retros are fired!” Although his instrument panel didn’t confirm, he was in no doubt the retropack had jettisoned as planned, as debris flew past his porthole windows: “I do not have a light. I see the straps falling away. I heard a noise.” Capcom and fellow Mercury astronaut Deke Slayton, in the Mercury Control Center, confirmed to him that telemetry indicated it had jettisoned. Shepard then maneuvered the spacecraft into the correct re-entry attitude and engaged the Automatic Stabilization Control System (ASCS): “OK, Buster. Re-entry attitude, switching to ASCS . ASCS is OK.” After experiencing five minutes of weightlessness, 0.05g was detected, indicating he was hitting the denser atmosphere. Here, he is seen preparing for what would be a rapid and intense increase to a peak loading on his body of 11.6g during re-entry, “OK. This is Freedom 7. ‘G’ build-up 3, 6, 9 .”

May 5, 1961 / gmt 14:43* to 14:45* / Suborbital 4 AND 27 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED AND MAURER 70MM NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG AND 13012- 124

MR-3

Top left: Shepard looks out of the left porthole window. He had tried to look for stars earlier but was unable to. Bottom left: The porthole window is clearly visible in his visor reflection. As his rate of descent was greater than expected, he worried about drogue chute deployment, and was late calling out his altitude, “45,000 feet now.” Due to considerable pendulum movements, he considered jettisoning the drogue, but waited and this occurred automatically: “The drogue is green at 21,000 [feet].” And 30 seconds later: “Standing by for main . Main chute is coming unreefed and it looks good.” Right: The Maurer 70mm inadvertently captures the drogue, antenna fairing, and main chute deployment bag that separated from the capsule shortly after.

May 5, 1961 / gmt 14:45* to 14:49* / Suborbital

July 21, 1961 / gmt 12:38* to 12:50* / Suborbital 16MM RECOVERY FILM

MR-4

Top left: Liberty Bell 7 can be seen after splashdown, with its whip antenna (used for recovery communications) extended. Grissom to recovery helicopter Hunt Club 1: “My condition is good; OK the capsule is floating, slowly coming vertical, have actuated the rescue aids. The reserve chute has jettisoned . and the whip antenna should be up . Give me about another five minutes here . before I give you a call to come in and hook on.” Top right: “OK, Hunt Club. This is Liberty Bell 7. Are you ready for the pickup?” “This is Hunt Club 1, this is affirmative.” Grissom: “OK, latch on, then give me a call and I’ll power down and blow the hatch, OK?” “Roger, and when you blow the hatch, the [recovery] collar will already be down there waiting for you.”

A single unprocessed frame, filmed by National Geographic photographer Dean Conger from another recovery helicopter, shows Hunt Club 1 move in. Moments later, things went terrifyingly wrong. Bottom left: The hatch prematurely blew and water instantly entered the spacecraft. The processed film here shows Grissom hastily squeezing himself out of the hatch and entering the water, for fear of going down with his ship. Bottom right: As seen from Hunt Club 1, Liberty Bell 7 is sinking and Grissom is floundering in the water. Unbeknownst to the recovery crew, Grissom hadn’t closed an oxygen inlet on his suit, which caused him to quickly lose buoyancy. NASA was perilously close to losing its spacecraft, and its astronaut.

July 21, 1961 / gmt 12:50* / Suborbital

Top: Grissom bravely helped ensure Hunt Club 1 hooked onto his sinking spacecraft and can be seen in this processed film giving the double thumbs up to pilot Jim Lewis, and crewman John Reinhard, despite struggling to stay afloat. The weight of Liberty Bell 7, filled with water, proved too much and was ultimately lost to the ocean. Grissom was lucky to escape with his life – later picked up by another helicopter. Grissom always maintained the hatch blew of its own accord. Bottom left: One of 17 consecutive enhanced frames that appears to show the hatch tumbling away from the lower right area of the spacecraft. Bottom right: Single frames of the recovery film revealed little detail in the silhouetted helicopter (see previous page, top right), but

24 stacked and processed frames now reveal that at the moment the hatch is apparently observed leaving the spacecraft, Reinhard is standing in the doorway of Hunt Club 1, with a squib-activated cutter on a pole, extended to precisely where the antenna was snipped. This now corroborates Reinhard’s statement that he saw an electric arc from the pole to the antenna, which inadvertently set off the explosives in his squib cutter and the hatch explosives at the same time. This explanation of accidental electrostatic discharge would completely exonerate Grissom from any blame, 60 years after the mission.

MISSION

ROCKET

CAPSULE

LAUNCH

DISTANCE

DURATION

ORBITS

EVA TIME

MIN. PERIGEE

MAX. APOGEE

SPLASHDOWN

RECOVERY SHIP

GEMINI IX- A Titan II GLV

Gemini

13:39 GMT, June 3, 1966, LC-19

1,091,113 nautical miles

3 days, 20 minutes, 50 seconds

45 2 hours, 7 minutes

86 nautical miles

182 nautical miles

14:00 GMT, June 6, 1966, Western Atlantic USS Wasp

Thomas P. Stafford

COMMAND PILOT

Born September 17, 1930. Stafford was an Air Force officer and test pilot. Having flown on Gemini VI-A, performing the world’s first space rendezvous, Gemini IX-A made him the first of four astronauts to fly two Gemini missions. He and crewmate Cernan would later join John Young in 1969 and fly to the Moon on Apollo 10. He also commanded the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

Eugene A. Cernan

PILOT

Born March 14, 1934. Cernan, a naval aviator and fighter pilot, joined NASA as part of its third intake of astronauts in October 1963. Gemini IX-A was his first spaceflight. He and crewmate Stafford would later join John Young in 1969 and fly to the Moon on Apollo 10. He was Commander of Apollo 17 in December 1972, and is to this day the last human to have walked on the Moon.

June 3, 1966–June 6, 1966

Days after almost losing two astronauts on Gemini VIII, NASA announced the crew of the first Apollo mission. Due to launch within a year, Apollo 1 would be commanded by Gus Grissom, Ed White, and rookie Roger Chaffee. The prime crew of Gemini IX was Elliot See and Charles Bassett, with Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan as back-up. All four were due to attend rendezvous training and inspect their spacecraft at the McDonnell plant in St. Louis. Each pair flew their T-38 jets; See and Bassett led, with Stafford and Cernan flying wing position. There was bad weather and poor visibility as they approached the runway to land. Stafford pulled up and climbed skyward, but See banked low and left. He hit McDonnell building 101, the very building in which the Gemini capsule he was due to fly was being completed. The Gemini IX prime crew were killed.

The tragic accident bumped Stafford and Cernan up to prime crew. The mission’s main objectives were to dock with an Agena target vehicle, perform a further two rendezvous to demonstrate principles for Apollo, and conduct the second U.S. spacewalk, which included testing an Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU). Developed by the Air Force, the AMU was a jet-powered backpack with its own life-support system and radio. It was stored at the rear of Gemini’s adapter section. Handholds and a footbar with stirrups were added to help Cernan don the backpack, and 80 Velcro patches were bonded to the spacecraft and to his gloves and boots to help him crawl to it. Cernan would then disconnect himself from the spacecraft’s life-support system and fly the AMU away from Gemini.

Many felt the AMU was too dangerous. Its hydrogen peroxide thrusters could burn Cernan’s suit, so extra insulation was added, but this made it stiffer and bulkier. The Air Force wanted him to fly freely, but NASA insisted on the inclusion of a tether. It was still an extremely bold plan, but NASA had just three and a half years to put a man on the Moon before the end of the decade and, to date, the only EVA experience was Ed White’s short spacewalk. The Gemini team were comfortable with rendezvous on the fourth orbit, known as “M=4,” but those planning Apollo pushed for an

“M=1” – rendezvous on the first orbit, as this was the plan for lunar orbit rendezvous. A compromise was made and Gemini IX would attempt an “M=3.”

Launch day arrived on May 17 and the Agena lifted off on its Atlas booster. Two minutes later, the Atlas flipped hard over into a nosedive, and it headed back toward the Cape, crashing into the Atlantic 120 miles east. Just like Gemini IV, Stafford lost his Agena and he and Cernan made their way back down the lift at the pad. This time, the solution was already waiting for them in a hangar at the Cape – the simpler augmented target vehicle, the ATDA. The mission was redesignated Gemini IX-A.

The ATDA launched perfectly, but a computer issue meant Stafford again had to exit his spacecraft as the launch was scrubbed. When lift- off occurred two days later, for his second spaceflight, he’d been strapped into a spacecraft six times. As suspected from telemetry on the ground, Gemini IX-A arrived to find the shroud of the ATDA wasn’t fully open, so docking would be impossible. Various options were discussed to release the mechanism, including an EVA. Buzz Aldrin was a vocal proponent of the idea but it was highly risky, and given the other important mission objectives to come, it was decided no docking would take place.

Cernan later described his EVA as “the spacewalk from hell.” He made his way to the adapter section and donned the AMU, but was lucky to return from there alive. Had he not, Stafford would have an unthinkable decision to make. Before launch, Deke Slayton, who now ran flight crew operations, entered the room where Stafford was suiting up and asked the suit technician to leave and closed the door. He expressed NASA’s concerns about the EVA and added, “In case Cernan dies out there, you’ve got to bring him back, because we just can’t afford to have a dead astronaut floating around in space.” Stafford set out his concerns about how difficult that would be and that, ultimately, once the bolts blew at lift- off, he was Commander and he’d make the call. After suiting up, Cernan quizzed Stafford: “Deke was in there talking to you quite a while. What did he say?” Stafford replied: “He said he just hoped we’d have a good flight.”

A Maurer 70mm camera was taken on the flight, in addition to the usual Hasselblad 500C. A Hasselblad Super Wide (SWC) also made its first trip into space. Cernan described his time viewing Earth during his EVA as “like sitting on God’s front porch,” and he used the SWC out in the void to take some truly spectacular photographs, including one of the finest of a Gemini capsule in space.

Due to the residue left on the windows on previous flights, caused by the fireball that engulfed the entire spacecraft during second-stage ignition, covers were added over their windows that were jettisoned after launch. They didn’t help much, but the crew were still able to capture quality film and stills, including of the ATDA shroud for post-flight analysis.

June 3, 1966 / GMT 17:50* / Rev. 3

46 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED

NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG

Just 49 minutes after a successful launch, Stafford made their first burn, to raise their perigee. Cernan: “I felt that one, Tom!” More burns were necessary for rendezvous with their target – the ATDA (Augmented Target Docking Adapter). Intermittent radar lock was made at 129 miles out and one hour later, Cernan: “Hey! I see it.” Stafford: “Oh yes, it’s out there, man!” Cernan: “Boy, I hope that’s not the shroud . . . Wonder if I should try to get any pictures of this?” Stafford: “Go ahead . one final sequence . look at that moose!” Cernan: “Doesn’t look like it’s tumbling Come on, baby, you’re 5 feet per second and you’re at 780 feet . It’s upside down, but we’re looking at it! . Boy, I wish we had daylight, we could see this thing better, Tom.”

June 3, 1966 / GMT 18:10* / Rev. 3

16 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED

NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG Stafford: “There are no stars out there.” Cernan: “No, that Moon is just blinding.” Suspicions raised from telemetry after their target was launched were confirmed, Stafford: “The shroud is half open on that thing!” Cernan: “You could almost knock it off! I feel certain you could.” Stafford to Hawaii Capcom: “How are you? I’ve got a weird-looking machine here! Both the clamshells of the nose cones are still on, but they are open . . . just barely held on by those four little pyro wires there . . . I’m now about 3 feet from it . It looks like an angry alligator out here rotating around . I’d like to look at the idea of possibly extending the docking bar and going up and tapping it and maybe the whole thing may fall apart.”

June 3, 1966 / GMT 18:32 / Rev. 4

The “angry alligator,” 157 nautical miles above Isla La Orchila, off the Venezuelan coast, at a range of 75 feet. The planned docking with the ATDA would be impossible in its current configuration, but tapping it with the capsule was just too risky. Capcom: “I have some information for you. The people at the Cape and Houston do not believe we can get the shroud separated.” Gemini IX- A continued to

maneuver around to inspect their target – which also contributed to a Defense Department experiment to assess inspecting unidentified, tumbling satellites at close quarters. The crew then planned for their equiperiod rendezvous test. Stafford: “Were now directly above the ATDA and I’m getting into position for the burn.”

June 4, 1966 / GMT 12:19 / Rev. 15

An even more audacious plan to free the shroud was being considered – during the spacewalk. Capcom Neil Armstrong in Houston: “We’ve just been talking to Dave Scott and Jim McDivitt at some length. They’ve been climbing around the shroud out at Douglas [the plant with a duplicate vehicle] for the last few hours and they advised . the inside may turn out to be a problem. There’s

quite a few sharp edges and things.” The band could whip out and tear a spacesuit if cut free, so hopes of releasing the shroud, and docking, were fading. Stafford: “Still have him in reflected sunlight in a sunrise now.”

June 4, 1966 / GMT 12:24 / Rev. 15

The second rendezvous was a success, but the third, incorporating a test to determine if rendezvous could be completed visually, without radar, proved difficult. Stafford: “We’re looking straight down on him and I still can’t see him.” After three rendezvous in 24 hours the crew was ready for some rest, but first Capcom Armstrong informed them that Mission Control would remotely engage the

ATDA’s thrusters. “Would you be in a position to observe and photograph that?” Stafford: “My camera is all set up . You turned it on and off, now it’s started to roll to the left . Man! Those RCS thrusters are still firing real rapidly . We’re still snapping pictures . We’re going to have plenty of documentary evidence of what caused the failure [to the shroud].”

June 4, 1966 / GMT 21:51 / Rev. 21

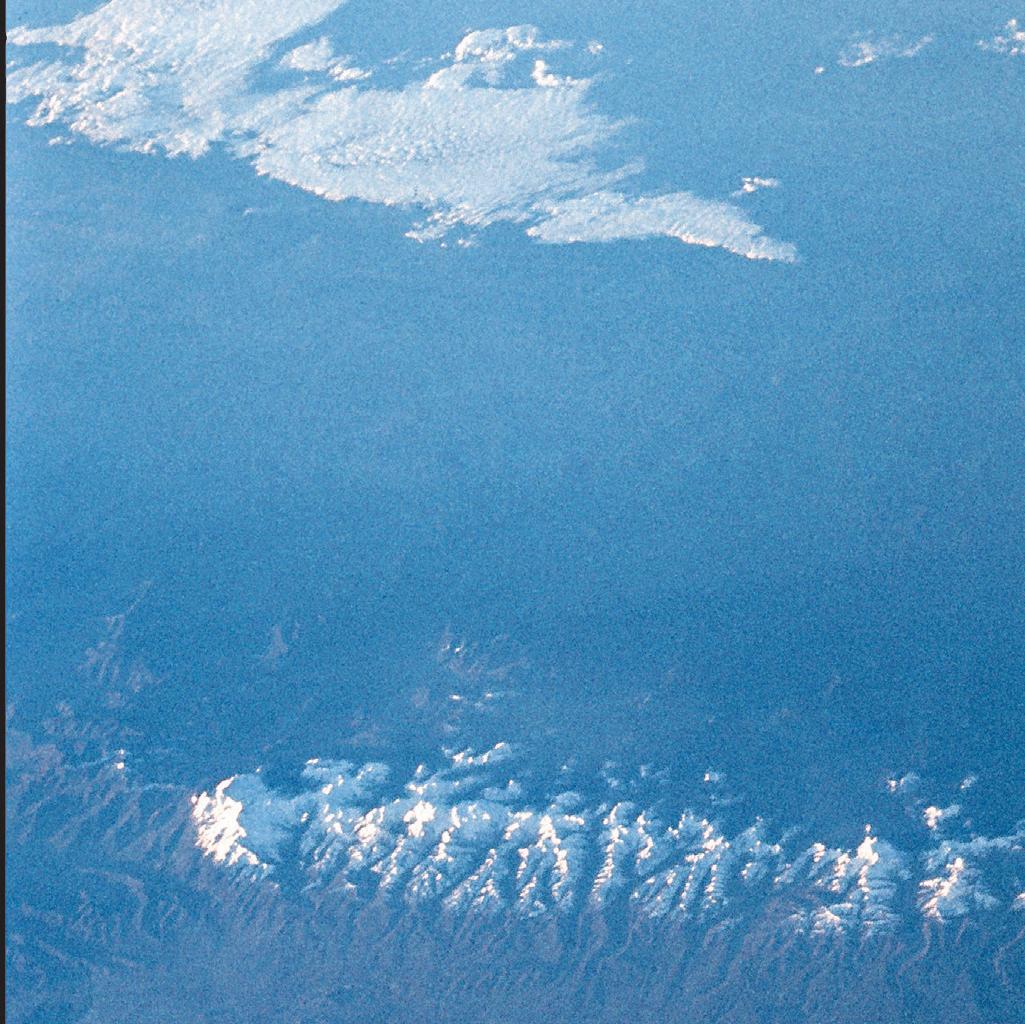

Twilight over Peru and Bolivia. The sunlit 21,300 feet Illimani volcano, east of La Paz, is prominent. The crew had barely had time to look out or photograph Earth due to their busy schedule. Stafford: “It’s been pretty much looking at other things – the ATDA on the rendezvous and it’s been kind of cloudy, too.” During the 15th revolution, they had expressed their concern about

F/2.8 BY

the imminent EVA. Stafford: “OK. We both just finished talking it over. Right now we’re both pretty well bushed. I’m afraid it would be against my judgment to go ahead and do the EVA at this time . [We should] do some experiments and try in the morning.” Capcom Armstrong told them that Houston agreed.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:10* / Rev. 31

Stafford: “I have just depressurized the cabin and all systems are holding pressure.” Cernan: “Why don’t we go ahead and pop it? . Man, the hatch is stiff . Standing in the seat now . Boy, is it beautiful out there, Tom!” Safford: “Sure looks pretty . You’re kind of rocking the boat.” Cernan: “You’d better hold me so I don’t leave you . while I’m standing here. Tom, let me at least get a

picture . . . We’ll find out how easy it is to be able to take pictures with this thing.” Stafford: “You’re the highest photographer in the world!” Cernan: “Not the highest paid . Man, is that beautiful! Oh, boy, Tom!” Restored from a damaged frame – the first photograph taken during Cernan’s EVA, and the first ever taken with a Hasselblad in the void of space.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:17* / Rev. 31

Cernan struggled to mount the 16mm camera, then made his way to the front of the capsule to fit a mirror to the docking bar, shoving away from the hatch with his feet and getting his hands in the RCS thrusters to pull himself along. Stafford: “I’ll help guide your feet out, Gene, and I’ll start taking some pretty pictures.” A magazine of film, possibly exposed, floated out of the hatch and was lost. Cernan: “Let me take a breather, Tom . . . Boy, everything wants to ride up . . . Let me get these Velcro pads on . Whew! We’re coming right over L.A. I can see Edwards [Air Force base] . Taking a picture of Baja right here.” Seen here, Stafford to Mission Control: “Say, is that terrific. Gene’s taking a picture of Baja California!”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:21* / Rev. 31

Cernan: “Hello, there! If I can get over here, I’ll take a picture, Tom.” Stafford: “OK. I don’t know how long you can hold out there . If you let go, you’re going to fly right off that thing . Let me get some pictures . smile!” Cernan: “Boy, am I smiling!” Cernan is out front, his Hasselblad can be seen mounted to his chest, having taken the photograph opposite. Stafford was concerned the thrusters may fire on Cernan as he pulsed to maintain attitude: “Let me know when you start back toward the aft thrusters and I’ll shut off the control power . You’ve really changed the moment of inertia of the spacecraft!”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:21* / Rev. 31

158

a

. and

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:22* / Rev. 31

Cernan: “I’m going to pitch off here to the left . I don’t know where I’m going right now, so hold on [firing the thrusters] . I’ve got the snake all over me . If I can push off, I’m going to try to get out here where I can evaluate this umbilical . I can’t get my feet in the right place to push off.”

pulled the

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:24 / Rev. 31

Cernan struggled to maneuver with the umbilical: “OK, Tom. I’m going straight for you.” Stafford: “OK, I can see you in the darkness while we’re here . . . looking real good.” Cernan: “Yes. I can see you in the cockpit. I’m overhead.” Cernan later told Mission Control about the unusual effect of continuously floating upward in relation to the spacecraft: “I think the main problem starts in the cockpit. The fact that you start floating up all the time. Whenever you’re outside, it’s always up, you never float down.”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:24 / Rev. 31

Cernan: “OK. I’ve just been back towards them [thrusters], Tom.” Stafford: “I’m going to take a picture through the mirror.” Cernan was getting tired, and can be seen in the mirror, tumbling over the top of the spacecraft. The 80 Velcro patches affixed around the spacecraft, pre-flight, were of little use. Cernan later told the ground: “Around the surface of the spacecraft, it would take a great deal of strength and wrist action to keep your body stiff. I don’t think you would be able to develop this type of torque with the Velcro pads, because again your feet will tend to go right on over the top of you because you tend to float up.”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:25 / Rev. 31

Cernan then managed to clamber forwards again: “OK. I’m going further out in front, Tom Boy, what a beautiful spacecraft, golly! . I’m going to try to get over on your side . I want to evaluate these hand pads if I can . OK. Now I’m stuck on this thing with a hand pad right now but they won’t stay. The Velcro’s not strong enough here . I’m trying to go up here now if I can, away from you. Right out.” Stafford: “You look like a real snake out there . You’re going end over end, Gene.” Cernan: “I want to see what I can do around the nose here.” Stafford: “OK. Come on over in front of the window and I can get a picture of you.”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:38* / Rev. 31

Cernan tugged on the umbilical: “OK, Tom. I’ll come back to the hatch here . . . what time is it?” Stafford: “About 24 minutes after sunrise . Your foot just kicked my head here, do you want me to help you in the hatch, Gene? . Don’t kick that dear heater circuit breaker whatever you do! How are you doing?” Cernan: “Looks like you had a nice lunch!? . I’m going to slow down and take a rest.” Stafford to Mission Control: “Gene’s finished with the umbilical evaluation . . . I can see him real well with this docking bar mirror. It’s a real useful piece of gear.” Cernan can be seen in the mirror, standing in the hatch as he prepares to head to the rear of the adapter section to don the AMU (Astronaut Maneuvering Unit). He was lucky to return alive.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 15:49* to 16:16* / Rev. 32

This accidental shot, looking down from above Cernan’s right shoulder, appears to show him in the adapter, his right foot close to the left-foot stirrup. His suit is bathed in reflected light from the Gold mylar. Stafford: “Ready for the next step?” Cernan: “Yes. Let’s go slow, though.” Stafford: “Connect black tether jumper hook to the AMU tether ring.” Cernan: “It’s very, very hot!” “Just take your time, Gene . . . night-time coming your way shortly . . . I can imagine the Sun beating down on you!” Cernan: “These darn hooks, Tom! . The umbilical is flying all over the place . I’ve got to rest a minute.” His heart rate was 155bpm, he was sweating, and his back was unbearably hot – it was later discovered he had torn his suit / insulation when he bumped and broke an antenna.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 16:35* / Rev. 32

SWC

LENS

Darkness fell. Cernan: “Who said this visor wouldn’t fog up!?” Stafford: “You’re going to have the Moon back there in just a minute . that should help you.” “I’m working up a good heat load, I’ll tell you . My pressure reading is fogged up, my visor’s fogged up.” His heart rate hit 180bpm and the Flight Surgeon was concerned he could lose consciousness. Stafford: “Turn around 180 degrees and back in[to] the AMU and relax.” Cernan: “I’m in, Tom.” He fastened his seatbelt. “Just sit there and rest, Gene . Is the visor starting to clear?” Cernan: “If I don’t breathe.” Cernan took this photograph over the Pacific Ocean, as GT-9A crossed the terminator back into the light; the distant Moon is high above. Alone, exhausted, hot, and effectively blind, he then lost communications with his Command Pilot.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 16:47 / Rev. 32

Cernan was shouting to be heard. For 20 minutes they resorted to binary – one “squawk” for “Yes,” two “squawks” for “No.” Cernan: “Just let me relax.” Stafford, barely audible: “Well, can you see out at all, Gene?” He received two “squawks” – “No.” “OK. You can’t get anywhere. I’ll tell Houston ‘NO GO.’ ” Cernan had to get back to safety but still couldn’t see. Pushing the mic away from his lips with his tongue seemed to help the comms issue. Stafford asked him to raise his hand above the adapter, so he could use the mirror to guide it onto a rail. Cernan found it and floated up, avoiding the jagged adapter plane, then “walked” hand-over-hand, effectively blindfolded save for a small spot around his nose, as Stafford pulled on the tether. Photo from the hatch, back toward the adapter.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 16:49 / Rev. 32

Cernan pulled down on his helmet, lifted his head, and used his nose to rub a larger hole through which to see: “I can see right through my nose but I can’t see in front of my eyeballs.” Stafford: “Houston . I can see in the mirror he’s pretty well fogged over to about 60 to 70 percent of his visor.” The AMU would not be tested in space. Cernan: “Hey, Neil [Armstrong]. You might tell everyone down there . I’m sure sorry about this.” Stafford: “OK. How about getting the docking mirror back in?” “You want that out of there?” Stafford: “Yes. We want it out of there.” Cernan: “OK. I’ll go up and get it .” Despite maximum flow on his suit’s temperature control, Cernan instantly fogged over again. Conscious of a troublesome hatch noted earlier, the mirror was left in place.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 16:54 / Rev. 32

Stafford to Mission Control: “He is still out there taking pictures. Except we’re having trouble closing the hatch and we’re going to go ahead and [try to].” Cernan again photographed Baja California, as he had 90 minutes earlier – he became the first man to orbit Earth, entirely outside a spacecraft. Stafford guided Cernan’s legs: “Boy, am I tired!” Stafford: “Houston . We are

having a very big deal getting this hatch closed. I don’t think I’d like to do this again, would you [Gene]?” Cernan: “No, I wouldn’t.” Stafford: “Don’t push it. It’s got to be pulled . Whooppee!” Cernan: “Is that it? . Let’s pressurize this cabin, Tom. Close the valve . I can tell you one thing, Tom – once I was back there [at the adapter], my chances were about 50–50.”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 18:41 / Rev. 34

Cernan: “We’re pressurized, Tom. I can’t get the visor open . . . I can’t get it off!” His visor was still fogged up. When his helmet was eventually removed, Stafford later said Cernan was pink – as if he’d been in a sauna too long. Despite the risk of causing a short-circuit, Stafford sprayed Cernan’s face with the water nozzle. The crew discussed the EVA. Stafford to Capcom: “We learned a whole lot out of the EVA. It was a real worthwhile exercise. I think it was still a real fine exercise. We hated to give up the AMU portion of it, but we did do some good umbilical evaluation and we got some pictures. We also got a lot of thermal inputs to give back to the people.” Tom Stafford on board Gemini IX- A.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 18:42 / Rev. 34

An exhausted Gene Cernan back on board. When pressurized, the suit ballooned and Cernan compared its flexibility to a rusty suit of armour. Still fogged over, he had contorted his body to such an extent to be able to close the hatch that he couldn’t get air into his lungs. Seeing spots in front of his eyes, he was close to losing consciousness before the cabin finally repressurized and his suit

softened. Capcom: “You did good work, friend.” Cernan: “You don’t know how much.” “I do . . . The Surgeon told me.” Cernan became extremely cold – each boot, which he couldn’t remove, contained 1.5lbs of sweat. Cernan to Mission Control: “Tom thinks I need some ballet lessons.” Capcom (Armstrong): “Ha ha! you want me to give them to you?” Cernan: “Not exactly.”

June 5, 1966 / GMT 20:17 / Rev. 35

Hawaii Capcom: “I have a Flight Plan update for you . at 54:38:34 through 54:47:28 [GET] – photographs of South America; 70mm Hasselblad, 80mm lens; strip chart; weather and film permitting. These should be nadir [vertical / straight down] photographs.” One of the photographs, here, looks straight down from 146 nautical miles on the coast of Peru, from Chimbote

F/2.8

BY

to Paramonga. Snow-capped peaks in the Andes are upper right. The white, fine meandering line pointing to “7 o’clock” from the central peak (the 22,205 feet Huascaran) is the path of the devastating avalanche that killed 3,000 people just four years earlier.

June 5, 1966 / GMT 20:28 / Rev. 35

The Earth’s terminator (the area between day and night), at sunset, 149 nautical miles over South America. The illuminated horizon is reflected and mirrored on the nose of Gemini IX- A. Capcom: “Could you do a fuel cell purge for us at this time?” There were none of the issues with fuel cells that had plagued Gemini V. Cernan: “Fuel cells have been working real good up here.” Capcom:

“They’re running real beautiful down here. This is the nicest I’ve ever seen fuel cells running!” The crew had further encounters with the ATDA since the EVA – gaining radar lock at 160 nautical miles, as they continued to circle Earth.

June 6, 1966 / GMT 09:28 / Rev. 43

The Tibesti Mountains (upper right), on the border of Libya, Chad, and Niger. Capcom Buzz Aldrin: “I’ve got some ball scores here if you’re interested?” Stafford: “OK. Let’s hear them, Buzz.” “OK. Pittsburgh 10, the [Houston] Astros 5.” Stafford: “You struck out, try again!” Capcom Aldrin: “Chris [Kraft] is wondering when he ought to get the cigars out to light up, once you hit the water.” Cernan: “When he sees our smiling face on the carrier, and I’ll buy. I might even break training after splashdown and smoke one, too.” Capcom Aldrin: “I’m not sure I read that right.” Cernan: “You did.”

June 6, 1966 / GMT 10:56 / Rev. 44

Stafford: “We’re going to take some pictures on this pass and then finish the stowage.” The more relaxed and rested crew were able to focus more on Earth observations and photography over the latter part of the mission. Stafford: “It looks like it’s nice and sunny out in the Canaries today.” Canary Capcom: “Yes. It’s a lovely day outside here.” “I’m going to snap a couple of pictures.”

Cernan: “Canaries, IX. Which island is the tracking site on?” Capcom: “It’s on the Grand Canary Island.” “Is that the big one in the middle?” “Right, that’s the big one. Way down at the south end.” Gran Canaria is the island in the foreground, with Tenerife above.

June 6, 1966 / GMT 13:44* / Rev. 45

20 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED

NASA ID: N/A 16MM MAG Stafford: “Do we have a loaded computer at this time?” Capcom Armstrong: “Negative Transmitting now.” One hour later, over Australia, Carnarvon Capcom: “We’ll be standing by. Have a good trip home!” Stafford to Cernan: “Got your D-Ring [for the ejector seat]?” “No. It’s jammed I just pulled the pin out about 1/4 inch.” Stafford: “I’ll do the same thing after retrofire . After you get your camera on the floor, then pull your D-Ring out . All we need is one of them.” If pulled, both ejector seats would fire. Cernan: “OK. Faceplates are down.” Capcom: “3, 2, 1, RETROFIRE!” Cernan: “Come on. Keep going, baby! . Four good Retros. I guess we’re coming home, baby OK, Tom, let’s fly the re-entry the way we can.” Stafford: “Really going to feel good to feel these gs!” An RCS thruster can be seen firing as the capsule proceeds through the atmosphere. Cernan: “Oh boy! . Man, that’s really – really something! . That’s pretty out there, Tom.” Stafford had seen it before, on Gemini VI- A: “You haven’t seen anything yet. Wait till you see the big fireball!”

June 6, 1966 / GMT 13:50* / Rev. 45

16 FRAMES OF 16MM FILM, STACKED AND PROCESSED

NASA ID: N/A

16MM MAG Cernan: “What’s all that stuff coming out there behind us?” Stafford: “Oh, just some pyro . The retro-pack will be behind us and above us and look like it’s up there.” Cernan: “You’re about 40 miles ’til Earth . It’s beautiful . Boy! What a fireball, Whew! . Boy, we’re really doing something, aren’t we?” Stafford: “Two gs . Boy, look at that fire!” Five minutes later, the main chute deployed at 7,000 feet. Cernan: “There it is. Oh! Beautiful, baby! Gemini IX, we’re on the main chute at this time . What a sight, wish I had a picture of that.” They were spotted at 3,000 feet. Capcom: “We have you in sight . . . Gemini IX. You’re on TV.” Cernan: “Splashdown! . . . Son of a gun! Excuse my language.” Stafford: “That was the worst of the whole shebang.” Cernan: “Man! That was a real hit!” Stafford: “Oh, we’re leaking water, too . This is Gemini IX. We’re starting to leak water. Get the swimmers over here ASAP!”

Violet Zhang Marketing Contact

VZhang1@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk

Fiona Livesey Publicity Contact

FLivesey@penguinrandomhouse.co.uk