Chosen one of Canada’s top Landscape Designers

Canada’s first Green for Life award

Awards

Chosen one of Canada’s top Landscape Designers

Canada’s first Green for Life award

Awards

By Shauna Dobbie

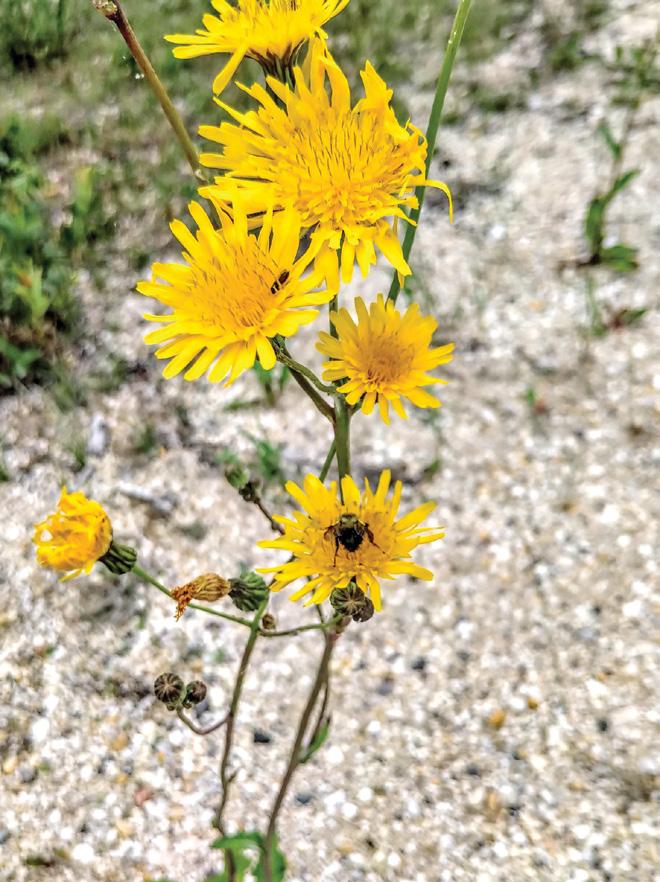

You’ll notice something new in our pages this issue: we’re printing the names of native plants in green. It’s a small change intended to help you easily spot which plants are native to some part of Canada.

We’re not here to tell you what to plant. Whether your garden is filled with heirloom roses, hardy vegetables, or tropical annuals, we’re all for it. But we also see the value in growing native plants, especially as gardeners look for ways to support pollinators, reduce maintenance, and reconnect with the natural world.

So, what exactly is a native plant?

A native plant is one that occurs naturally in a region without human introduction. These plants evolved alongside local wildlife, like pollinators, birds, insects, fungi, and they form the backbone of their ecosystems. They're often well adapted to the soils, climate, and rhythms of the place they call home.

But here's the catch: where a plant is native to matters. A species native to the southern interior of British Columbia might not occur naturally in Newfoundland. Even within one province, a plant might be native to a certain habitat or elevation but not to another. That’s why our use of green text means only that a plant is native to somewhere in Canada, not necessarily to your own area.

There are also “nativars”, which are cultivars of native plants. These won’t appear in green in our pages. They may be beautiful or even beneficial, but because they’ve been selectively bred by humans, they aren’t true natives.

Think of it as a prompt, not a prescription. If a plant name is printed in green, it’s a chance to learn more. Maybe it’s native to your region, or maybe it’s worth researching what alternatives are.

We’ll continue to celebrate all kinds of gardens and all kinds of gardeners, and we hope this new feature adds a layer of awareness, and maybe even curiosity, about the plants that have been here all along.

Purchase a single digital copy of any issue of Canada’s Local Gardener from Volume 2 Issue 4 and up now available! Scan the QR code or go to https://order.emags.com/ca_local_gardener_digital

Follow us online www.localgardener.net

Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener

Instagram: @local_gardener

YouTube: @LocalGardenerLiving

Published by Pegasus Publications Inc.

President Dorothy Dobbie dorothy@pegasuspublications.net

Editor & Publisher Shauna Dobbie shauna@pegasuspublications.net

Art Direction & Layout Karl Thomsen karl@pegasuspublications.net

Contributors

Steven Biggs, Dorothy Dobbie, Shauna Dobbie, Edith Fishlock, Robert Pavlis, Tania Scott.

Editorial Advisory Board

Greg Auton, John Barrett, Todd Boland, Darryl Cheng, Ben Cullen, Mario Doiron, Michel Gauthier, Mathieu Hodgson, Jan Pedersen, Stephanie Rose, Michael Rosen, Aldona Satterthwaite and Trudy Watt.

P rint Advertising

Gord Gage • 204-940-2701

gord.gage@pegasuspublications.net

Marketing Manager

Micaela Soto • 204-940-2702 micaela@pegasuspublications.net

Subscriptions

Write, email or call Canada’s Local Gardener P.O. Box 47040, RPO Marion Winnipeg, MB R2H 3G9 Phone: 204-940-2700 info@pegasuspublications.net

One year (four issues): $35.85

Two years (eight issues): $68.08

Three years (twelve issues): $98.40

Single copy: $12.95 Plus applicable taxes.

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Circulation Department

Pegasus Publications Inc. PO Box 47040, RPO Marion Winnipeg, MB R2H 3G9

Canadian Publications mail product Sales agreement #40027604

ISSN 2563-6391

CANADA’S LOCAL GARDENER is published four times annually by Pegasus Publications Inc. It is regularly available to purchase at newsstands and retail locations throughout Canada or by subscription. Visa, and American Express accepted. Publisher buys all editorial rights and reserves the right to republish any material purchased. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright Pegasus Publications Inc.

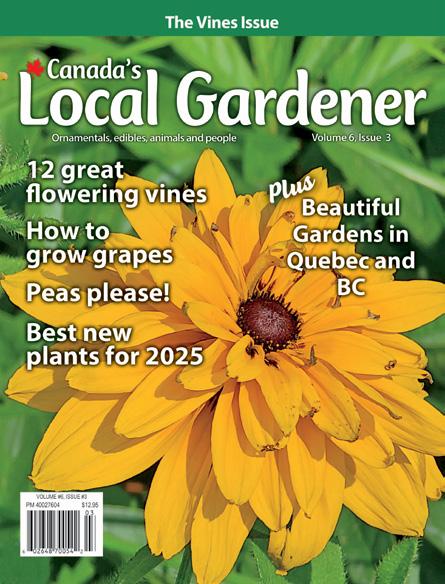

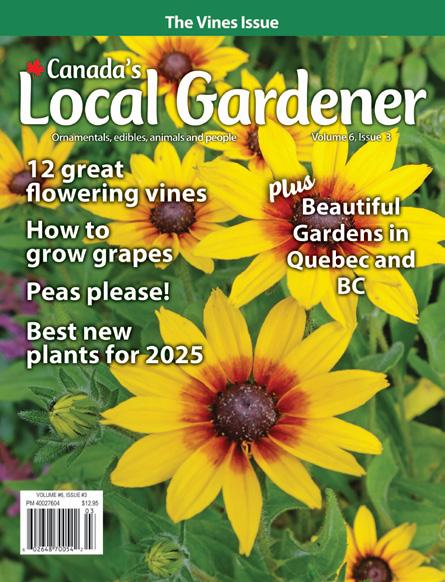

The cover on this issue is not perfect, but we think it’s darned good. It makes you wish you were a tiny bee that could fly in and around the black obelisk, that could venture into the pea blossom.

We had been looking for a “DYC” flower. At first, the one upper left looked perfect. Then, at the correct size, I realized that the edges of the petals were past their best-before date. And then I realized that we just had a yellow composite flower on the cover a couple of issues ago. So… so much for our other yellow composite covers.

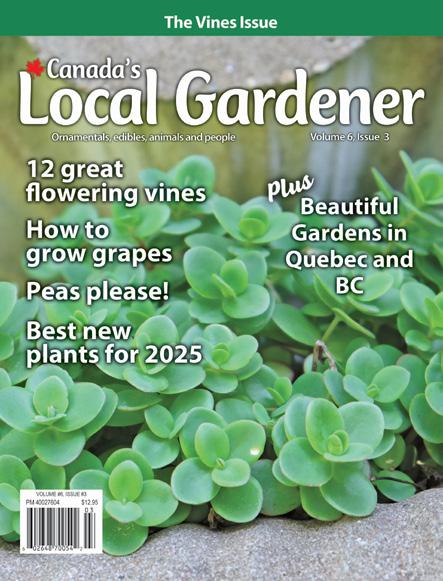

I really love the image from the lower right, and you may see it on a cover soon. The sedum is so new and juicy. The fence behind it has the right amount of room for the magazine title. And there is a spot and a bit of dead leaf in the live area that proves that this is real. AI has not touched this image!

I found the picture of peas growing in my back yard at the eleventh hour. If only the camera had been lowered about two degrees! The bottom of the peas is cut off and there is a little too much fence. But you look at the beautiful fresh flower in the middle and the intricate lace of tendrils around it… This must be the image for the cover of The Vines Issue.

During the Second World War, when resource shortages were hitting hard, an unlikely Canadian plant stepped into the spotlight: Asclepias syriaca, better known as common milkweed.

At the time, life jackets for sailors and airmen were typically filled with kapok, a buoyant fibre harvested from tropical trees in Southeast Asia. But when wartime blockades cut off supply routes, Allied forces were left scrambling for an alternative.

In Canada and the United States, scientists discovered that the silky white floss inside milkweed pods had remarkably similar properties: it was lightweight, naturally waterproof, and highly buoyant. Even better, the plant grew abundantly in fields, ditches, and along roadsides – especially in southern Ontario and parts of Quebec.

Beginning around 1944, the Cana-

dian government supported a collection program that mobilized children, families, and farmers to gather milkweed pods during the fall. Schools were recruited to help, with students encouraged to fill sacks with mature pods before the frost. The slogan from the American campaign – “Two bags save one life” – was echoed in Canadian classrooms and agricultural bulletins.

The pods were gathered in burlap sacks, dried, and sent to processing facilities where the floss was cleaned and packed into life jackets for Navy and Air Force personnel. One life vest required roughly 1.5 kilograms (or about 30,000 fibres) of milkweed floss.

Though the program was shortlived and largely forgotten after the war, it marked a rare moment when a native “weed” was nationally valued for its life-saving potential. It’s also a remarkable example of wartime citizen science, as botanists, engineers, and schoolchildren alike worked together to turn a roadside plant into a vital resource.

Today, with Asclepias again in the spotlight for its role in monarch conservation, it’s worth remembering the time when Canadians were called to gather it – not just to save butterflies, but to help save lives. k

By Dorothy Dobbie

Gardeners of a certain age will be saddened to learn of the passing of Mr. Tomato, Brian Gory. Born March 28, 1943, he was just 8 days short of his 82nd birthday.

Gardeners will remember Brian as the man who invented Kozy Coats, which allowed tomatoes to be planted outside as much as two months earlier in some places. He also created the Sea Magic brand as a fertilizer booster in Canada and the United States. He sold his company some years ago, but the products are still sold by many retailers and on the Internet.

Readers of the Local Gardener series of magazines will remember Brian for his entertaining stories, his light touch with his pieces which were often laced with humour. He was a great favourite at trade shows and on the garden speaking circuit.

Brian began life as a reporter and was a long-time stringer for The Globe and Mail, breaking many important stories in

his day. His other love was horse racing and for many years, he was the handicapper and columnist, writing under the name Ivan Bigg for Assiniboia Downs in Manitoba and more recently as a writer for Toronto’s Woodbine.

Brian had a beautiful garden – very small and cozy but broken into rooms with intriguing pathways leading from one vignette to another. He loved Arctic impatiens, even though he understood their bad reputation of having explosive seed heads (like all impatiens) that cause

them to spread. Despite the size of his garden, he always had something edible growing that he could munch on while doing some early morning deadheading –as he liked to say in his impish way on my radio show, he enjoyed having the occasional pea in the garden!

Brian could be irascible and difficult with very firm opinions on gardening and horse racing, too, but that did not stop people from loving him. Brothers Kevin and Brian Twomey, the former owners of T&T Seeds, credit him with bringing life to their seed catalogue amid battles and laughter.

He gardened right up to the very end, helping friends and neighbours beautify their yards, helping a dear friend build a rooftop garden on top of his garage, and looking for new wonder products to share with the world.

Mr. Tomato, Ivan Bigg, Brian Gory… the world is a much less interesting place in your absence and gardening is so much better for your having been a part of it. k

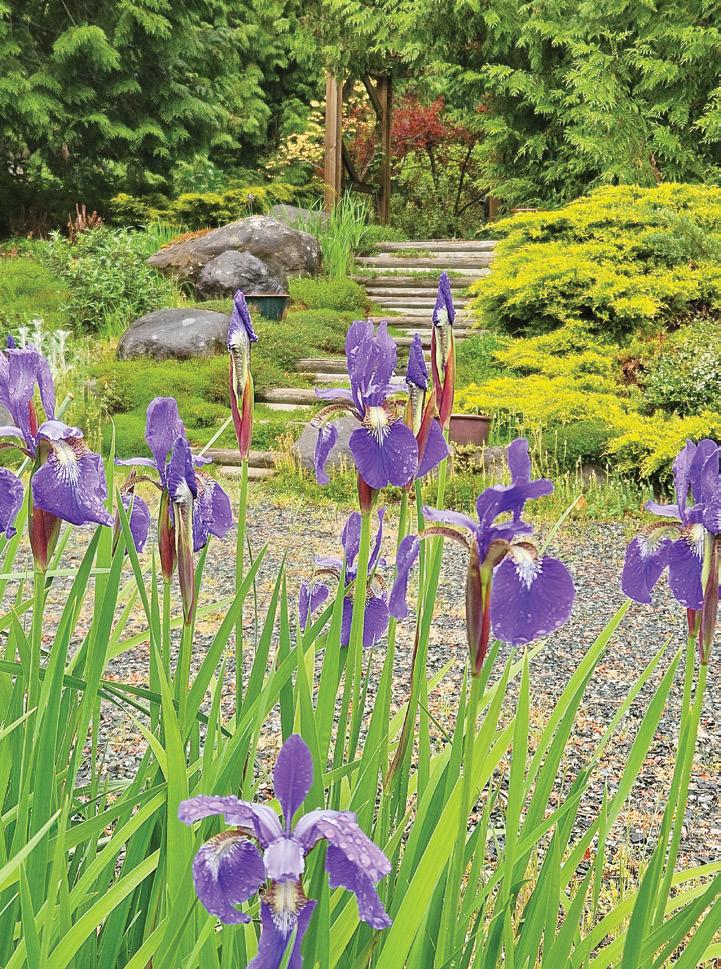

Spring and fall are the traditional seasons for dividing perennials, but early summer offers a valuable window for refreshing certain plants, especially those that bloom later in the season. With the right care, early summer division can rejuvenate crowded clumps, improve flowering, and help you expand your garden without spending a dime.

The key is timing and technique. Early June, when the soil is still moist and the heat hasn’t peaked, is ideal. Focus on perennials that are not in full bloom. Daylilies, Siberian iris, phlox, and Shasta daisies respond particularly well to division at this time. Avoid plants that are flowering or already stressed from heat or drought.

Start by watering the plant well the day before. Lift the clump carefully with a spade or garden fork,

trying to keep as much root intact as possible. Use a sharp knife or spade to cut the plant into sections, making sure each division has healthy roots and several shoots. Replant immediately at the same depth they were growing, water thoroughly, and mulch to help retain moisture. Shade them for a few days if the sun is intense.

Removing flower buds or cutting back the foliage can help the divisions direct energy into root growth. Within a few weeks, your plants should be settling in, ready to grow strong through the summer and bloom better than ever.

Dividing in summer isn’t for every plant, but when done wisely, it gives your garden a mid-season boost. It’s also a great time to share divisions with fellow gardeners or fill in bare spots in your own yard. k

By Shauna Dobbie

Inever thought I would get excited about a Y-valve. Then I tried several types, ranging from cheap hardware-store plastic pieces to a pricey electronic one from Amazon and a few in between. I went through three last year alone! But I recently got a new Twin Shut-Off valve from Dramm, the company that makes Rainbird and other watering and gardening products and this promises to answer my problems.

If you’ve been through as many Y-valves as me, you will know that they can be ridiculously fragile. Most are made out of zinc alloy, which is practically designed to wear out as soon as you look at it. They also have tiny, flimsy plastic levers to determine which side should be on and off. These levers are not made for manipulating with garden gloves on. They are made for breaking with those gloves on, though. This new twin shut-off valve is made out of POM, or polyoxymethylene, which is, according to Wikipedia, “an engineering thermoplastic used in precision parts requiring high stiffness, low friction, and excellent dimensional stability.” It’s used in things like locks and ball bearings. It is very stable in temperatures down to -40 Celsius (but I’ll bring it in for the winter) and as high as 80 Celsius. And it resists all the elements found in your water without buildup.

The levers to turn the water for either side on or off aren’t weak-armed things, they are sturdy handles that you can operate with gloves on. And to make things so much easier, there is an easy-grip swivel fitting to attach the unit to the spigot in your garden. And finally, the outlets (the parts you attach the hoses to) are brass. k

Soil temperature plays a crucial role in gardening, particularly in the early spring when planting seeds and transplants. It's not just the air temperature that matters; soil warmth determines seed germination, root development, and microbial activity. But how do you know what your soil temperature is?

You can use a soil thermometer, but for gardeners eager to get started without a soil thermometer, there are practical ways to estimate soil temperature using common tools and observational cues.

Why soil temperature matters

Different plants have different temperature needs. For example, peas and spinach germinate well when the soil is around 5 to 10 Celsius, while tomatoes and corn prefer it closer to 15 to 18 Celsius or warmer. Cold soil can delay germination or cause seeds to rot, and transplanting tender plants

BOB’S SUPERSTRONG GREENHOUSE POLY.

10 & 14 Mils. Pond liners. Resists hail, snows, winds, yellowing, cats, punctures. Long-lasting. Custom sizes. Free samples. Email: info@northerngreenhouse.com www.northerngreenhouse.com Ph: 204-327-5540 Fax: 204-327-5527 Box 1450 Altona, MB R0G 0B0

To place a classified ad in Canada’s Local Gardener, call 1-888-680-2008 or email info@localgardener.net for rates and information.

Join the conversation with Canada’s Local Gardener online! www.localgardener.net

Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener

Instagram: @local_gardener

YouTube: @LocalGardenerLiving

into chilly ground can stunt their growth or kill them.

Estimating soil temperature without a thermometer

While a soil thermometer is the most accurate tool, there are still reasonably effective ways to gauge soil temperature using simple techniques and good observation.

Use your hand or bare foot. This is the oldest method in the book. Stick a finger or foot a few inches into the soil. If it feels uncomfortably cold, it's likely below 10 Celsius. If it's cool but not shocking, it's probably in the 10 to 15 Celsius range. Warm and comfortable soil suggests it's closer to 18 Celsius or higher. This method isn't precise, but it gives a general idea and helps tune your senses to the conditions.

Monitor air temperature trends. Soil lags behind air temperature but eventually catches up. A good rule of thumb is that after five to seven

consecutive days of average daytime temperatures above 10 Celsius, your soil will likely also be nearing that temperature – especially if nights are above freezing. If daytime highs are consistently over 15 Celsius with warm nights, expect soil temperatures to reach planting range for warmseason crops.

Use a kitchen thermometer. If you have a metal probe-style kitchen thermometer (used for meat or candy), it can double as a soil thermometer in a pinch. Insert it into the soil about 2 to 4 inches deep, ideally in the morning and again in the late afternoon to get an average.

While nothing replaces the accuracy of a proper soil thermometer, you can still make well-informed planting decisions using your senses, tools from the kitchen, and nature’s signals. Paying attention to soil temperature helps you avoid wasted seeds and gives your plants a healthy start. k

is moved between locations, so are the insects.

Story by Tania Scott

Chamomile is not only a beautiful flower but a powerful healing plant. Indeed, the words strong, kind and powerful come to mind when I think about chamomile. This is one of the most widely grown and used medicinal herbs in the world. Native to the temperate regions of Europe and Asia, this lovely gold and white daisy-like flower is easy to grow and is now cultivated around the world.

In honour of chamomile being declared the ‘2025 Herb of the Year’ by The International Herb Association; I decided to reacquaint myself with this famous medicinal plant.

How chamomile is used as a medicinal around the world

The traditional use of chamomile – I’ll focus on German chamomile

(Matricaria chamomilla) rather than Roman chamomile or other kinds of chamomile – mainly involves the use of dried flowers for a tea with a lovely apple-like fragrance. The word “chamomile” comes from the Greek words “chamos” and “melos” which are translated as “ground apple”.

Chamomile tea is consumed for a wide variety of traditional medicinal purposes, such as colds, fevers, nervous disorders, digestive disorders, and as a sedative in Spain, Bulgaria, the United Kingdom, Germany, Portugal and other countries in Europe; and used in traditional Chinese medicine in Asia; indeed, its use as a medicinal goes back thousands of years in ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt. In Canada, chamomile also has a long history of use; for

example, in the book Baba’s Kitchen Medicines, the author recounts how chamomile tea was used as an important medicinal by early Ukrainian settlers on the Canadian prairies for a variety of conditions, such as colds and flu, anxiety, gastrointestinal disorders, sore throats, and congestion.

Folk medicine versus scientific evidence

Although we tend to think of chamomile as folk medicine, I was curious to see what the scientific research had to say about chamomile’s therapeutic uses. In fact, a lot of research has been done. I’ll narrow down the research to three areas (and point out that scientific research has confirmed several other therapeutic uses for chamomile).

Considerable research has been done on chamomile’s antioxidant activity. Antioxidants are powerful plant nutrients that protect our cells from the excessive production of unstable molecules (free radicals, for example). This research demonstrates that chamomile has important antioxidant activity mainly because it is a good source of the flavonoid apigenin. Apigenin has been shown to strongly inhibit free radical production and help protect the body.

Several lab studies report that the essential oils found in chamomile exhibit antimicrobial activity against certain bacteria and fungi. For instance, chamomile essential oils show antibacterial activity against several Staphylococcus, Bacillus, and Streptococcus species. In a recent study (2024) looking at the effects of eye drops containing chamomile on microbial pathogens, the authors write: “Chamomile-containing eye drops displayed great antimicrobial properties against Streptococcus pneumoniae and S. aureus. All concentrations resulted in a decreased growth of S. pneumoniae CFUs [colony forming units]. The effect on S. aureus was so fast that we had to adjust shorter exposure times.” In addition, chamomile essential oils show antifungal activities against several Candida species.

Much of the folk medicine use of chamomile centres around its potential to reduce anxiety. Until recently, there had been no systematic review on the topic, so it was hard to say what the scientific evidence was for using chamomile to reduce anxiety. Another recent paper (2024) has closed that gap by conducting a review of the previously published studies on the use of chamomile to treat anxiety. Starting with 389 papers and then whittling down the selected papers to 10 (based on their screening process; for example, human subjects, oral intake of chamomile), the authors found that nine studies demonstrated that chamomile is effective in reducing anxiety by modulating neurotransmitter pathways. Furthermore, they note that “due to the side effects of drugs used to treat anxiety disorders, the use of chamomile seems to be effective and less dangerous.”

Making tea out of chamomile is the way most people enjoy it.

This is promising confirmation by scientists that generations of traditional medicinal users were on the right track.

Chamomile is easy to grow. Direct sow the seeds outdoors in May. The seeds need light to germinate, so sow the seeds on top of the soil, press in and cover lightly with soil. Keep the soil moist until germination. Harvest chamomile flowers at any stage. You can even harvest chamomile flowers after the petals have fallen off the golden centres. Run your fingers through the flowers like a rake to

harvest the heads. This is a faster process than picking the flowers one by one. Dry the flowers for tea. You can also use them fresh.

Making chamomile tea

Use 1 teaspoon of dried flowers (or 2 teaspoons fresh) per 1 cup of boiled water. Let the flowers steep for about 5 minutes – chamomile can get bitter if it steeps too long – and then add a spoonful of honey if desired. k

Tania Scott is a seed saver and urban farmer. Tania and her family love growing things and have started the seed company Common Sense Seeds (www. commonsenseseeds.ca) in Calgary.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

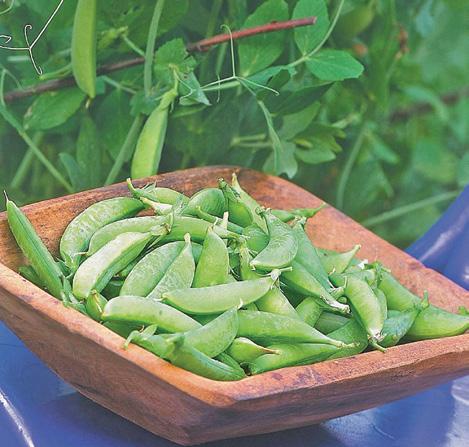

Peas are among the first vegetables you can plant outdoors, offering a welcome taste of spring and a productive harvest with minimal fuss. Whether you're interested in snap peas, snow peas or shelling peas, growing them in your home garden is easy, rewarding, and well-suited to Canada’s climate.

Why grow peas?

Peas are a cool-season crop that thrive in early spring and tolerate light frosts. Their sweet flavour makes them a garden favourite, and they enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen, a natural benefit for crop rotation. With the right conditions, peas are not only quick to grow but also one of the most spaceefficient vegetables for small gardens and containers.

Pea types

When selecting which peas to grow, consider your space, taste preferences, and climate. There are bush-type and vining peas, and different varieties are bred for different points of harvest.

Shelling peas (also called English peas): grown for their sweet green seeds, not the pods.

Snap peas: edible pods with plump seeds.

Snow peas: flat, tender pods harvested before the seeds mature. Pick them early!

You can sometimes eat a shelling pea as a snow pea before it is mature, or a snow pea as a snap pea, but it depends on the variety; don’t count on it.

Plant them early

The key to success when growing peas in Canada is early planting. As soon as the soil can be worked in spring, typically late March to mid May depending on your region, peas can go into the ground. They germinate in soil as cool as 5 Celsius, though they’ll sprout faster in slightly warmer temperatures.

Avoid soggy soil by planting in raised beds or well-draining areas. If your garden tends to stay wet in early spring, wait until the soil dries out enough to crumble easily in your hand.

Soil: pH 6.0 to 7.5, well-draining, moderately fertile.

Water: Consistent moisture, especially during flowering and pod set.

Starting: Direct sow outdoors; don’t disturb the roots.

Timing: Sow as soon as soil can be worked in spring; harvest in 55 to 70 days.

Depth and spacing: 2 inches apart in rows 12 to 24 inches apart

Notes: Provide a trellis for vining type. Bush type can benefit from some support, too.

Prepare the soil. Choose a sunny location with well-drained, moderately fertile soil. Peas do not need a lot of nitrogen, so avoid high-nitrogen fertilisers. A top-up of compost is ideal.

Sow the seeds. Plant pea seeds 1 to 2 inches deep and about 3 inches apart in rows spaced 12 to 24 inches apart. Dwarf types can be grown more densely, while climbing types need space and support.

Provide support. Even bush peas benefit from some form of support. Use trellises, netting, or bamboo stakes to keep plants upright and improve air circulation, which helps prevent fungal diseases.

Watering. Peas need consistent moisture, especially during flowering and pod development. Water at the base of the plant to avoid wetting the leaves, which can lead to mildew.

Mulching. Add a layer of straw or leaf mulch to retain moisture, cool the soil, and suppress weeds.

Weeding. Keep the area weed-free, especially early in the season. Pea seedlings don’t compete well with aggressive weeds.

Peas are typically ready to harvest 55 to 70 days after sowing. The ideal time to pick depends on the type:

• Snap peas should be full and crisp, with rounded pods.

• Snow peas are harvested while still flat but before seeds swell.

• Shelling peas are ready when pods are plump but not over-mature.

Pick peas every day or two to encourage more production. Harvest in the morning when sugar levels are highest, and use or refrigerate them quickly;

Did you know the same pea plants you grow for pods can also give you an early bonus harvest? The tender tips and tendrils of pea plants are not only edible, they’re delicious.

When to harvest

Snip the top 4 to 6 inches of growth before the plant starts to flower. Use clean scissors and cut just above a leaf node to encourage branching.

How much to take Harvest just a few shoots from each plant to avoid reducing your

pod yield. The best time is early in the season when the vines are young and leafy.

How to use them

Pea tendrils are crisp and sweet with a mild pea flavour. Add them fresh to salads, toss into stir-fries at the end, or pile them onto sandwiches for a gourmet touch.

Bonus tip

If you’re planting a second round of peas in late summer, take more tendrils and fewer pods; they’re perfect for fall salads.

peas lose sweetness as their sugars turn to starch.

Common pests and diseases

Powdery mildew can affect lateseason plants. Reduce risk by spacing plants well, using resistant varieties, and watering at the base.

Aphids may appear on young growth. Knock them off with water or use insecticidal soap if necessary. Aphids can also transmit pea enation mosaic virus, which causes curled, thickened leaves and distorted pods. Remove infected plants promptly and control aphids to reduce spread.

Pea weevils and cutworms can be managed with crop rotation and floating row covers to protect seedlings.

Root rot , caused by soil-borne fungi

like Fusarium or Pythium, leads to stunted, yellowing plants and mushy roots. Avoid planting in cold, wet soil, improve drainage, and rotate crops regularly.

Downy mildew appears as yellow spots on the tops of leaves with grey mould beneath, especially in cool, damp conditions. Improve air circulation, avoid overhead watering, and remove affected plants.

Ascochyta blight causes dark lesions on stems, leaves, and pods. Prevent it by using certified seed, rotating crops, and removing all plant debris at the end of the season.

Can I grow a second crop?

In most areas, you can plant a second round of peas in mid- to late summer

for a fall harvest. Choose fast-maturing varieties and be prepared to provide extra moisture during hot, dry weather. Final tips for growing peas in Canada

Peas are one of the easiest vegetables to grow, even for beginner gardeners. Their cool-season preference makes them perfect for our climate, and their quick maturity offers fast gratification. With proper planting, good soil preparation, and regular harvesting, you’ll be rewarded with baskets of fresh, sweet peas before most of the summer garden even gets going.

Whether you’re growing peas on a balcony, in raised beds, or a full garden plot, this humble legume deserves a spot in your spring lineup. k

Story by Shauna Dobbie

If you’ve ever found a brown, shield-shaped bug crawling across your windowsill in autumn, you may have met Halyomorpha halys – the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB). Native to East Asia, this insect has been spreading across North America since the early 2000s and is now established in parts of southern Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia. Gardeners and farmers alike are keeping a close eye on this unwelcome visitor.

A stowaway turned pest

The BMSB was first identified in North America in Pennsylvania in 1996, likely arriving via shipping containers. By 2010, it had made its way to Canada, with Ontario as the first confirmed sighting. Since then, it

has slowly expanded its range, aided by its tendency to hitch rides in vehicles, packing materials, and cargo. This stink bug is highly adaptable and feeds on over 100 species of plants, making it a serious threat to fruit and vegetable crops, ornamental plants, and even field crops like soybeans and corn.

What it looks like

Adult BMSBs are roughly ½-inch long, with a marbled brown colouring and a distinctive shield shape. Their most recognizable features are the white bands on their antennae and legs, which help distinguish them from similar-looking native species. The edges of their abdomen often show alternating dark and light bands. Nymphs start out almost tick-like and red with black

markings, gradually changing to brown as they mature through five instars.

Unlike predatory stink bugs, the brown marmorated is a plant-feeder. It uses a long, piercing-sucking mouthpart to tap into plant tissues and draw out sap. This feeding damages fruits and vegetables by leaving behind sunken areas, discolouration, and internal rot, sometimes making produce unmarketable. In tomatoes, for example, this can cause cloudy spots; in apples and peaches, it leads to puckering and deformation known as catfacing.

Crops affected in Canada include:

• Apples and pears

• Peaches and nectarines

• Tomatoes and peppers

• Sweet corn

• Beans and soybeans

Why it's a problem

The BMSB is particularly troublesome because it’s a generalist – it doesn’t specialize in one type of plant. Its

broad appetite and lack of native predators allow populations to grow quickly in new areas.

It also has a seasonal nuisance factor. In late summer and autumn, adults begin to search for warm places to spend the winter. Homes and greenhouses often become targets. While these insects don’t reproduce indoors or bite, they release a foul, musty odour when crushed or disturbed. Some people say it resembles the scent of rotten almonds, burnt rubber, or dirty socks.

Control and prevention

Home gardeners may feel limited in their options for controlling brown marmorated stink bugs, but there are several strategies that can help:

• Exclude them: Seal cracks and crevices around windows, doors, vents, and siding. Install screens on attic vents and chimneys.

• Trap them: Light traps and sticky traps can be used indoors to capture stragglers.

• Hand-pick: In small gardens, hand-picking adults and nymphs and dropping them into soapy water is effective.

• Cover crops: Use floating row covers on sensitive vegetables, especially in late summer.

• Vacuuming: Use a handheld vacuum to remove bugs indoors (consider a shop vac, as household vacuums may retain the smell).

Pesticides are not particularly effective for homeowners, and widespread spraying can harm pollinators and beneficial insects. Avoid chemical solutions unless dealing with a large infestation and always read product labels carefully.

Hope from a tiny wasp

Canadian researchers are closely monitoring the spread of the samurai wasp (Trissolcus japonicus), a parasitoid native to Asia that lays its eggs inside BMSB eggs. The wasp kills the host egg, preventing stink bug nymphs from hatching. Encouragingly, this beneficial insect has been found naturally occurring in Ontario and British Columbia, likely arriving the same way as its host.

While it's not a quick fix, biological control may be the best long-term solution to keep brown marmorated stink bug populations in check without harming the broader ecosystem. k

Ontario

• First confirmed in 2010 (Hamilton).

• Now well established in parts of southern Ontario, especially the Niagara region, Greater Toronto Area, and Windsor-Essex.

• Has caused damage to fruit crops like apples and peaches.

Quebec

• Detected in Montreal and surrounding regions.

• Still limited in distribution but considered established in some areas.

• Agricultural impact has been

observed on apples and field crops.

British Columbia

• Found primarily in the Lower Mainland, especially around Vancouver and the Fraser Valley.

• Also detected in the Okanagan Valley, a key fruit-producing region.

• Considered established and spreading slowly.

(not yet established)

Alberta

• Occasional individuals have

been detected, likely through transportation.

• Not considered established as of latest monitoring efforts.

Manitoba

• No confirmed established populations.

• There have been isolated finds (often indoors), likely as stowaways in goods or vehicles.

Nova Scotia & New Brunswick

• No established populations reported.

• Some detections in cargo or homes, but no evidence of breeding outdoors.

Not all stink bugs are bad news. While the brown marmorated stink bug gets the headlines, Canada is home to a diverse range of native stink bug species, many of which play helpful roles in the garden. Here are a few to know.

Spined soldier bug (Podisus maculiventris). Beneficial predator of caterpillars and beetle larvae.

Two-spotted stink bug (Perillus bioculatus). Preys on Colorado potato beetle.

Green stink bug (Chinavia hilaris). Mild plant pest; prefers beans and tomatoes.

Red-shouldered stink bug (Thyanta custator).

Occasionally feeds on crops; usually minor. Rough stink bug (Brochymena quadripustulata). Generalist feeder, rarely causes damage.

Tip:

To distinguish the brown marmorated, look for white bands on the antennae (a key sign of the invasive BMSB). Native species typically lack this feature and are often green, red-brown, or grey with rougher textures. Encouraging biodiversity in your garden by reducing pesticide use and planting a range of flowers and crops can support beneficial insects, including our native stink bugs.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

There’s something undeniably cheerful about a flowering shrub that erupts into a flurry of soft pink blooms just as winter loosens its grip. Double flowering plums (Prunus triloba ‘Multiplex’) are among the earliest and most generous spring bloomers, producing an abundance of double-petalled, rose-like flowers on bare branches long before their foliage appears. Hardy, low-maintenance, and stunning in full bloom, these ornamental shrubs offer both structure and drama to Canadian gardens.

When I was a little girl, my grandma’s neighbour across her back land had one of these that bloomed gloriously every spring. I was entranced by it. I’ve been hoping to buy one since moving to Winnipeg; maybe this will be my year!

A brief history

Double flowering plums are a cultivar of Prunus triloba, a species native to northern China. The ‘Multiplex’ variety was developed for its exceptionally full, sterile blooms. Because the flowers are sterile, they don’t produce fruit, just beauty. The original species was introduced to North America in the 1800s, primarily for ornamental use, and it has remained a cottage garden classic.

Why “double” makes a difference

The “double” in double flowering plum refers to the multiple rows of petals in each bloom, giving flowers a frilly, pompom-like appearance. This feature not only increases visual impact but also means the blooms last longer than those of single-flowered varieties. While they don’t offer much for pollinators, they more than make up for it in sheer decorative appeal.

In most of southern Canada, double flowering plums bloom in April or early May, depending on the region. The shrub’s dark branches are quickly covered in light pink blossoms that look almost like tiny peonies. The effect is particularly striking when planted en masse or used as a specimen plant in a prominent

Blooms typically last two to three weeks, weather depending.

Growing conditions

These plums are hardy to Zone 3 and can tolerate temperatures as low as -40 Celsius, making them a solid choice for prairie gardens as well as coastal and central regions. They prefer full sun to part shade and well-drained soil. While reasonably drought-tolerant once established, they benefit from consistent moisture during flowering and establishment.

Maintenance and pruning

Double flowering plums are relatively low maintenance but benefit from some care to maintain their shape and vigour. They tend to sucker from the base, so removing unwanted shoots can help keep the plant tidy. Prune immediately after flowering to shape the shrub and remove any dead or damaged wood. Because flowering occurs on old wood, late pruning will reduce next year’s bloom.

Pests and diseases

Like many Prunus species, these plums can be susceptible to issues like black knot, powdery mildew, and aphids. Regular monitoring and good air circulation help mitigate these risks. Avoid heavy pruning during wet weather,

which can increase the chance of fungal infection.

Landscaping ideas

Plant double flowering plums where their early-season performance can be enjoyed – near entrances, patios, or pathways. Their strong structure also makes them ideal for mixed shrub borders, and their size (usually 4 to 6 feet tall and wide) makes them manageable even in small gardens. Their upright habit contrasts well with spreading evergreens or lower perennials.

Propagation

Since 'Multiplex' is a sterile cultivar, it doesn’t produce viable seed. Propaga-

tion is typically done through softwood cuttings or grafting. Most gardeners will purchase nursery stock, which is often available in the spring, but I have not found it yet.

A brief but brilliant moment

Double flowering plums may only bloom for a short time, but their effect is unforgettable. In a season when many landscapes are still waking up, these shrubs offer a vivid promise of the beauty to come. For anyone looking to add a little theatrical flourish to their spring garden without sacrificing hardiness, Prunus triloba ‘Multiplex’ is an ideal candidate. k

by Cliff.

Compiled by Shauna Dobbie, photos courtesy of the National Garden Bureau

Beloved for their vivid colours and non-stop blooms, annuals bring immediate charm to garden beds, containers, and hanging baskets. With just one season to shine, these plants put all their energy into growing, flowering, and delighting. The 2025 introductions offer new forms, fresh colour palettes, and reliable performance to keep gardens lively from spring through frost.

Ageratum 'Monarch Magic' ( Ageratum houstonianum). Brings so many pollinators to your outdoor spaces, your garden will be all aflutter. The vigorous and spreading habit helps it tumble out of hanging baskets and over balconies and window boxes. Height: under 12”. Spread: 8-16”. Ball Floral Plant.

Dahlia 'Mystic Wizard' (Dahlia hybrid). Deep mahogany foliage topped with jewel tone blooms. ‘Mystic Wizard’ has rich, magenta flowers with a dark black central disc. A great addition to the pollinator garden, ideal for containers, garden border or mass landscape plantings. Compact rounded habit. Height: 24-36”. PlantHaven International.

Dianthus 'Dart' (Dianthus barbatus). Petite dianthus offering early spring colour. A star as a front-border flower or to line a welcoming walkway. The flowers put

on a show in five special colours: Pink Magician, Purple, White Picotee, Scarlet, and White. Combine any of the colours for your own mix. Height: 6-8”. Spread: 6-8”. PanAmerican Seed Co.

Dipladenia 'Sun Parasol Fired Up Orange' (Dipladenia hybrid). A flat pinwheel-shaped flower that's sure to captivate. Its upright growth habit and narrow leaves create a sleek, modern look. Perfect for adding a fiery punch of orange colour to your patio or garden. Height: 18-24”. Suntory Flowers.

Mandevilla 'Sun Parasol Original XP Bluephoria' (Mandevilla hybrid). Coral-pink buds open to reveal stunning, velvety dark blue-purple blooms. Its compact size, abundant branching, and nonstop flowering make it great for gardens, containers and hanging baskets. Height: 12-18”. Suntory Flowers.

Ornamental kale ‘Crane Early Red’ (Brassica oleracea). This is a cut-flower type of kale. Extremely long lasting in arrangements and bouquets, it makes a stunning visual statement due to its beautiful form. Also comes in 'Early White'. Height: 36-48”. American Takii.

Pericallis 'Senetti Blue Spoon' (Pericallis hybrid). This groundbreaking new spoon-type variety is closer to true blue than purple. With its mounding habit and flowers above the foliage, it is a spring magnet for bees. Height:

12-18”. Spread: 12-18”. Suntory Flowers.

Petunia 'Capella Rim Raspberry' (Petunia hybrid). Featuring large, show-stopping, violet blooms that are rimmed in bright white. Perfect in containers, hanging baskets or as a landscape plant, you'll be drawn to this petunia again and again. Height: under 12”. Danziger.

Petunia 'Easy Wave Navy Velour' (Petunia hybrid). Do you have a favourite dark blazer or moody, oversized sweater in your closet? That’s the vibe that this petunia gives your garden. Blanket your intimate outdoor spaces with these large, velvety, blue-purple-black flowers and embrace a new era. Height: under 12”. Spread: 30-39”. PanAmerican Seed Co.

Petunia 'Easy Wave Rose' (Petunia hybrid). A distinct colour nestled somewhere between a passionate pink and neon. Beautifully iridescent and a standout in the garden. Height: under 12”. Spread: 30-39”. PanAmerican Seed Co.

Petunia 'Easy Wave Rose Morn' (Petunia hybrid). Softens the garden palette with blooms of consistent rose-pink hues and a contrasting white centre. The little peek of yellow at the very centre is a cheerful sight and welcoming at entrances or on patios. Height: under 12”. Spread: 25-32”. PanAmerican Seed Co.

Petunia 'Painted Love Purple' (Petunia hybrid). Unique bicolour flower pattern presents a dramatic new

look in the garden, planted alone or in combinations. Mounding habits are for hanging baskets and patio containers. Tested for outstanding garden resilience and flower stability for continued performance all summer long. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 18-22”. Syngenta Flowers.

Petunia 'SuperCal Premium Rose Star' (Petunia x Petchoa). Part petunia, part calibrachoa, this all-weather performer stands up to cold and heat. Plus, it can withstand heavy rains and bounce right back with little to no damage. Large, flat flowers feature a watercolour star pattern. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 18”. Sakata Seed.

Petunia 'Surfinia Heavenly Blackberries & Cream' (Petunia hybrid). Creamy white blooms adorned with a captivating, deep blackberry jam center – a truly irresistible combination. They deliver endless blooms and thrive even in rainy conditions, adding a touch of elegance to containers, hanging baskets, or the landscape. Height: under 12”. Suntory Flowers.

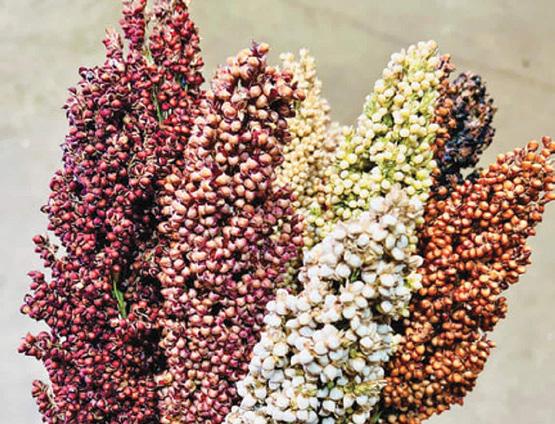

Sorghum 'Prairie Pearls' (Sorghum bicolour). An excellent choice for enhancing cut flower arrangements. With its natural colour options, interesting texture, and impressive vase life, this ornamental grass is perfect for bouquets, arrangements, and home décor alike. Can be used fresh or dried. Height: 3-4'. Spread: 12-16”. Express Seed Company.

Vinca 'Soiree Double Orchid' (Catharanthus hybrid). Two distinct layers of frilly lilac purple petals that light up the garden with amazing flower coverage and deep glossy green foliage. These plants keep their tight compact form all summer, with no leggy branches and tons of flower power. Height: under 12”. Spread: 14-16”. Suntory Flowers.

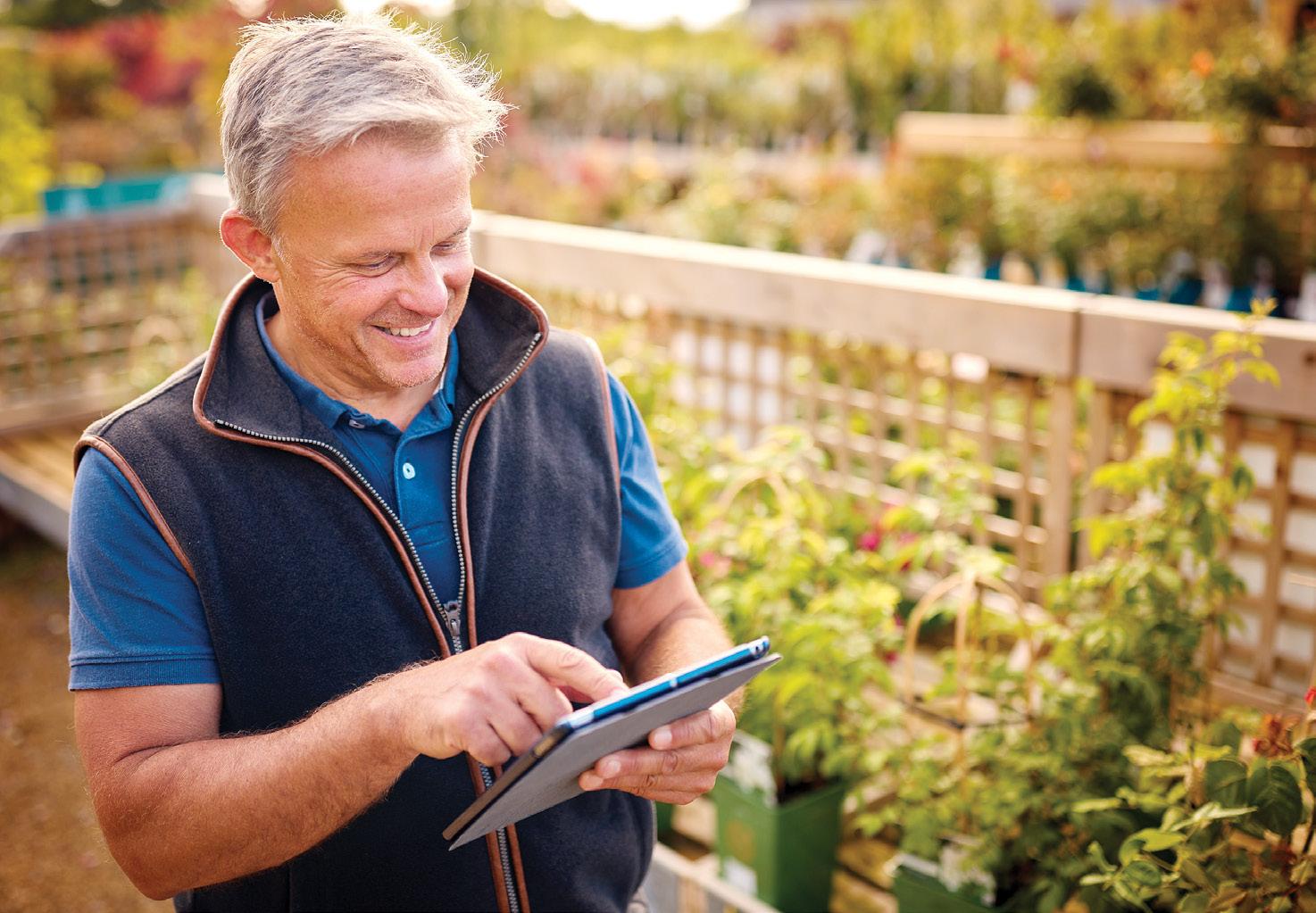

The stars of a returning cast, these new introductions offer fresh takes on long-time favourites like more blooms, better form, and sometimes surprising colours. Zones are listed as provided by the growers, but don't let that stop you. Ask at your local garden centre, if they are selling a variety, whether it will overwinter in your region, or if you should grow it like an annual and enjoy the show.

Butterfly bush 'Candy Lil' Raspberry' (Buddleia davidii). Exceptionally compact butterfly bush that attracts abundant pollinators with hot pink-hued blooms that rebloom from spring through fall. With fragrant blooms that provide bold splashes of pink in the landscape, this variety is water-wise once established. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 24-36”. Zone: 5. Plant Development Services.

Delphinium 'Delgenius Kingsley' (Delphinium

hybrid). A fresh look to the classic delphinium with semi-double, royal-purple blooms edged in electric blue, a colour combination that creates a captivating display. Maintains a compact habit, producing multiple sturdy flower spikes that reduce the need for staking and increase garden resilience. Height: 18-24”. Spread: 16-20”. Zone: 3. Pacific Plug & Liner.

Dianthus 'EverLast Ruby Edge' (Dianthus interspecific). Enjoy more days of colour than any other perennial dianthus. Tough as nails in all types of weather, it’s double-flowered and has a soft fragrance. Watch it flush in early spring, bloom late into summer, and flower again in autumn. Deep purple with white edges. Height: under 12”. Spread: 10-14”. Zone: 5. Selecta One.

Fountain grass 'Water to Wine' (Pennisetum alopecuroides). Add texture and four seasons of interest to the garden. Black inflorescences emerge from bright green foliage in the summer. Sturdy, bottle brush-like flowers are a nice cinnamon colour all season. As temperatures cool, foliage blushes red and purple and flowers turn tan. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 36”. Zone: 5. Must Have Perennials.

Gaura 'Flutterby Fountains Gold' (Gaura lindheimeri). This North America native has fresh golden central variegation to the more usual dark green

foliage. Profusions of pink buds open to sterile clear white blooms, giving an exceptionally long flowering period attracting an abundance of pollinators to the garden. Foliage maintains a neat tidy habit all season. Compact rounded habit. Height: 18-24”. Spread: 24”. Zone: 5. PlantHaven International.

Hellebore 'Frostkiss Elemental' (Helleborus hybrid). Captivating with its two-toned flower type featuring bubblegum pink petals beautifully outlined in rich magenta. It's an early bloomer, boasting an abundance of flowers and a compact growth habit. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 12-18”. Zone: 5. Pacific Plug & Liner.

Hellebore 'JWLS Endless' (Helleborus hybrid). A compact, upward facing hellebore with an extended bloom season. Selected for its glossy, dark green foliage topped with abundant and long-lasting blooms that start out green and transition to a beautiful white. Height: 12-18”. Zone: 5. Monrovia Nursery.

Hydrangea 'Game Changer Giant Pink' (Hydrangea macrophylla). Hydrangea macrophylla is the type you usually buy from the florist and isn’t very hardy. This one is hardier than most! It has extraordinarily large paniculata flowers that will bloom every day of the growing season. Flowering of new and old wood makes pruning easy. Height: 18-24”. Spread:

24-30”. Zone: 5. Green Fuse Botanicals.

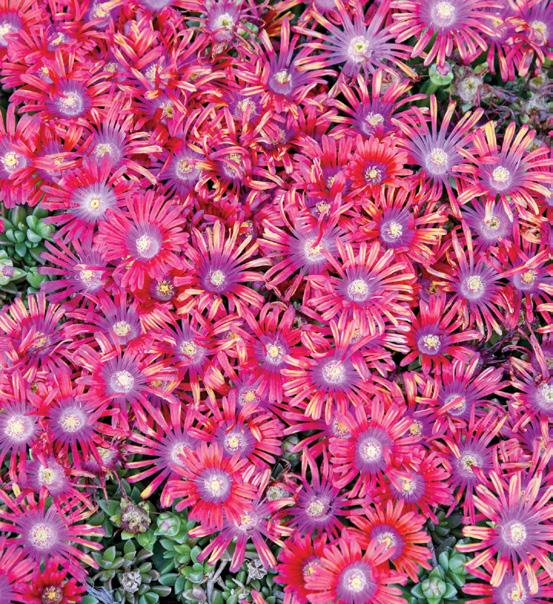

Ice plant 'Kaleidoscope Razzle Dazzle' (Delosperma hybrid). These plants are notable for heat and drought tolerance, as well as requiring little to no maintenance. Bicolour flowers transition from raspberry red tips to fuchsia purple eyes around cream centers. Height: under 12”. Spread: 20-24”. Zone: 5. Proven Winners.

Primrose 'Pretty Polly! Blushing Pink' (Primula x hybrid). Brings a new level of elegance to the polyanthus family with its large, double flowers in a soft, blushing peach hue. Unlike traditional polyanthus primulas, this one is more robust in growth, featuring a taller and more vigorous habit that fills larger pots beautifully, making it a real standout. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 6-8”. Zone: 4. Pacific Plug & Liner.

Rose mallow 'Cookies and Cream' (Hibiscus hybrid). A night and day combination of matte black foliage and pure white flowers. 'Cookies and Cream' emerges in late spring already showing its dark foliage. Full sun will bring out the deepest foliage colour. Beginning in midsummer slightly cupped 6-7” bright white flowers will appear. Each bloom is solid white, without the typical red eye of hardy hibiscus. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 42-48”. Zone: 4. Proven Winners.

Salvia 'Blue By You' (Salvia nemorosa). Bright bluepurple flower spikes bloom from summer to frost. With deadheading, it can rebloom up to five times per season. Attractive to hummingbirds, butterflies, and bees. Deer resistant and drought tolerant. Height: 18-24”. Spread: 20-24”. Zone: 4. American Meadows.

Sedge 'Bunny Blue' (Carex laxiculmis). Neat and wellbehaved, showing off strappy foliage with beautiful, cool blue tones. Evergreen and naturalizing, it will slowly spread for a versatile groundcover or alternative lawn. An excellent selection for shade gardens. Good for rain gardens and moist soil, while also tolerant of hot, dry shade. Deer resistant. Height: under 12”. Spread: 12-28”. Zone: 5. American Meadows.

Shasta daisy 'Lemon Puff' (Lucanthemum x superbum). Delightful double flowers with soft lemon-yellow petals and darker golden centers on a compact plant with a tight, low habit. Incredible flower power with a profusion of blooms. Excellent for container gardening or at the front of a border. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 18-22”. Zone: 4. ThinkPlants.

Shasta daisy 'Real Jewel' (Leucanthemum hybrid). Shredded banana-yellow petals give excellent garden performance in high rain areas. Elegant small foliage gives excellent resistance to higher temperatures. Compact habit. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 12”. Zone: 5. PlantHaven International.

Lots of beauties here. Only a couple are hardy to Zone 3 and none are listed below that. What can you do in Zone 2? Just look through with interest and thank heaven for lilacs!

Abelia 'Suntastic Peach' ( Abelia). Tidy and compact shrub with fantastic colours: new foliage is yellow and green, turning caramel through winter. Fragrant flowers. Height: 36-60”. Spread: 30-60”. Zone: 7. PlantHaven International.

Boxwood 'Better Boxwood Renaissance' (Buxus). Scientifically bred for its ability to resist blight! Rich green foliage and a conveniently compact habit. A great pick for parterre and knot gardens, borders and low hedges. Height: 12-18”. Zone: 5. Plant Development Services.

Burning bush 'Fire Ball Seedless' (Euonymus alatus). The only seedless, sterile, non-invasive burning bush on the market! It has all the durability and inferno-red colour that you expect but no risk of spreading into wild areas like conventional burning bush. Height: 5-6'. Zone: 4. Proven Winners.

Doghobble 'Paisley Pup' (Leucothoe fontanesiana). A handsome broadleaf evergreen with foliage that blazes an array of pink, green, cream, white, bronze,

and yellow hues. Racemes of fragrant white flowers dangle elegantly from the slender, arching stems, enticing pollinators. It has a versatile, low habit, outstanding deer resistance and it’s shade tolerant. Height: 3-4' Spread: 5'. Zone: 5. Proven Winners.

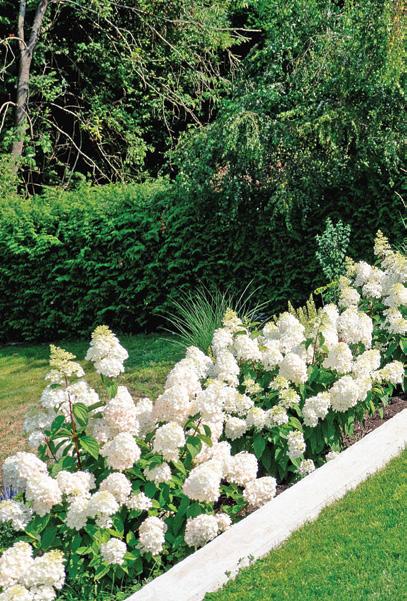

Hydrangea 'Bouncy' (Hydrangea paniculata). Very strong red stems hold large pure white panicle flowers each summer. As fall approaches, white flowers become red and pink for a new season of beauty. Height: 60-72”. Zone: 3. Bloomin' Easy.

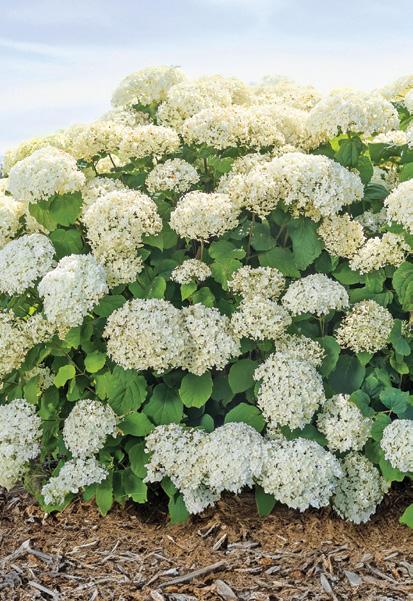

Hydrangea 'FlowerFull Smooth' (Hydrangea arborescens). Bold blooms and sturdy upright stems that won’t flop in the wind and rain. With two-to-three times more blooms per season than other smooth hydrangeas, it makes an outstanding focal point plant. Disease-resistant and low-maintenance. Height: 36-48”. Spread: 48-60”. Zone: 3. First Editions.

Redbud 'Garden Gems Amethyst' (Cercis canadensis). This compact tree is an elegant focal point in small gardens and when potted on patios. Its size and burgundy foliage give a similar effect to Japanese maple, but it has native North American parentage. A spring flush of pink blooms will attract pollinators. Height: 8-10'. Spread: 8-10'. Zone: 5. Star Roses and Plants.

Redbud 'Midnight Express' (Cercis canadensis). Bright pink, pea-shaped spring blooms followed by velvety, deep burgundy foliage. Adds a dramatic flair to any setting, whether it's a meticulously planned landscape or a natural-style garden. Gold and orange fall foliage. Height: 20-30'. Spread: 10-20'. Zone: 5. Proven Winners.

Rhododendron 'Bloombux Blush' (Rhododendron hybrid). Blush pink flowering and low growing. Perfect as a low hedge alternative to boxwood. Height: 18-24”. Zone: 5. Bloomin' Easy.

Rose 'Eau de Parfum Blush' (Rosa). Big, fully fragrant blooms provide the classic romance of roses with the added benefit of disease resistance brought to you by modern breeding. Blush pink blooms form a lovely bud, then slowly unfurl to their full glory. The lush foliage makes these excellent shrubs in the garden. Blooming repeatedly from early spring until first frost. Height: 3-4'. Zone: 5. Monrovia Nursery.

Rose 'Oso Easy En Fuego' (Rosa). Graces the garden with intensely colourful flowers that start off yellow and red and fully open to an electric orange. The large flower size and glossy green foliage make the effect especially memorable. It has outstanding disease resistance. Height: 3-4.' Zone: 4. Proven Winners.

These new edibles are bred for gardeners who want beauty, flavour, and performance in one tidy package. Whether you're growing on a balcony or in backyard beds, this year's selections may offer better disease resistance, more compact habits, or standout taste.

Basil 'Everleaf Lemon' (Ocimum basilicum). Tall, upright and highly branched for plenty of harvest potential. They are also very late to flower – up to eight weeks later than standard basil – for season-long enjoyment of tasty leaves. It has a bright lemon flavour, great for adding to dressings, marinades, and fresh salads. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 8-12”. PanAmerican Seed Co.

Broccoli 'Skytree' (Brassica oleracea). This broccoli is an 'easy floret’ variety with a segmented head allowing for easier harvest and preparation. It has a sweeter stem than traditional broccoli varieties. Height: 12-36”. Spread: 12”. Seminis/Bayer.

Cabbage 'Verve' (Brassica oleracea). This non-heading leafy cabbage produces beautiful mounds of hearty leaves. Prepared similarly to collards, leaves tenderize and offer a subtle sweet flavour and unctuous chew when cooked. To use leaves as carb-free wraps, lightly blanch and lay flat to cool. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 24-36”. Bejo Seeds. Hot pepper 'Hot Portugal' (Capsicum annuum). 60-85

days to maturity from transplant. Suitable for growing in containers, garden plots, raised beds, and greenhouses. Resistant to tobacco mosaic virus. Elongated fruit, bright red when mature. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 12-24”. True Leaf Market.

Pak choi 'Polly-Pak' (Brassica rapa). Fast-growing pak choi with bright purple leaves that hold well in the garden and add a beautiful pop of colour. Slow to bolt. Height: under 12”. Spread: 6-10”. Pure Line Seeds.

Pepper 'Pillar Peppers Luna Red' (Capsicum annuum). Sweet, red fruits on a compact plant habit, perfect for pots. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 5-7”. Pure Line Seeds.

Pepper 'Pumpkin Spooky Red' (Capsicum annuum). Pumpkin-shaped sweet peppers. The immature fruit starts in a creamy, ghostly green colour and matures to a deep red. Pot-sized. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 5-7”. Pure Line Seeds.

Sorrel 'Red Apache' (Rumex acetosella). Sorrel is a perennial herb with a tangy, lemon-earthy flavour often used in salads and sauces. It is easy to grow from seed and a great addition to your herb garden. Highly ornamental, drought and heat-tolerant sorrel variety. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 5-12”. True Leaf Market.

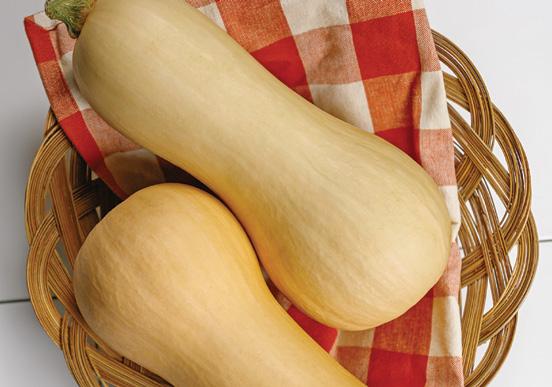

Squash 'Ceres' (Cucurbita moschata). Early maturing butternut is ready in 90-95 days from direct seeding. The creamy tan exterior is very smooth with no ribbing

and the interior firm, solid, dark orange flesh. Vigorous plant habit with intermediate resistance to powdery mildew. Height: 12-18”. Spread: 3-5'. Sakata Seed.

Tomato 'Honey Bee' (Solanum lycopersicum). Honey Bee is an early, improved artisan type with excellent flavour. Beautiful 1-inch red- and yellow-striped fruit. Compact plant habit, high yields, and less cracking than others of its type. Late blight-resistance. Height: over 6'. Spread: 24-36”. Johnny's Selected Seeds.

Tomato 'Lemonsugar' (Solanum lycopersicum). Indeterminate golden yellow round cherry that has strong vigor, good flavour and excellent cracking tolerance. It has a uniform cluster and good disease resistance. Height: 5-6'. Seminis/Bayer.

Tomato 'Pink Gal' (Solanum lycopersicum). An early producing indeterminate pink round beefsteak tomato with very good taste. Fruits are smooth, have excellent quality and uniformity and a nice pink colour. Nice slicer with great internal quality and a long shelf life. Average fruit weight is about 8 ounces. Excellent disease resistance package as well and has high resistance to gray leaf spot. Height: 5-6'. Seminis/Bayer.

Tomato 'Pink Pixie' (Solanum lycopersicum). A round indeterminate cherry tomato with excellent flavour, shiny skin and nice pink colour. Large uniform fruit size with minor cracking and great fruit quality. High

yield, heavy fruit set. Height: 5-6'. Seminis/Bayer.

Tomato 'RuBee Prize' (Solanum lycopersicum). Expect loads of very large (9-10 ounce) fruit with colour and show-stopping flavour in just 65 days. The compact indeterminate plants are leafy with good fruit cover, are disease resistant and super productive. The fruit are deep red, juicy, almost seedless with a slightly flattened globe shape. Height: 24-36”. Spread: 24”. Sakata Seed.

Tomato 'Unicorn' (Solanum lycopersicum). A indeterminate tomato that produces medium to large size, deep red fruits. Fruits are tolerant to cracking, firm, and have an excellent sweet-tasting flavour. Height: 5-6'. Seminis/ Bayer.

Tomato 'WonderStar Red' (Solanum lycopersicum). Determinate plants produce early maturing, bright-red fruits with excellent flavour. Good disease resistance, specifically to late blight and septoria leaf spot. Days to maturity from transplant is 60-65 days. Height: 18-24”. Spread: 24-36”. PanAmerican Seed Co.

Tomato 'Woodstock' (Solanum lycopersicum). Sugary and rich, with plenty of acid. Green when fully ripe with a psychedelic swirling interior. Productive yields of 8 to 12 ounce beefsteak-sized fruit. Easier to harvest than some green tomatoes as the bottom of the fruit shows a nice pink blush when ripe. Height: over 6'. Spread: 12-24”. Johnny's Selected Seeds. k

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Vines are the secret ingredient that can take a garden from nice to truly memorable. They soften walls and fences, create leafy tunnels, climb over arbors, and add height and drama to any space, big or small.

Clematis for all seasons

Clematis are among the most versatile and beloved flowering vines. With hundreds of cultivars available, there's a clematis for nearly every hardiness zone and garden style. Some, like Clematis alpina, bloom early in spring and are hardy to Zone 3, while others like Clematis 'Jackmanii' flower mid-summer with dramatic purple blooms. In colder regions, look for clematis that bloom on new wood.

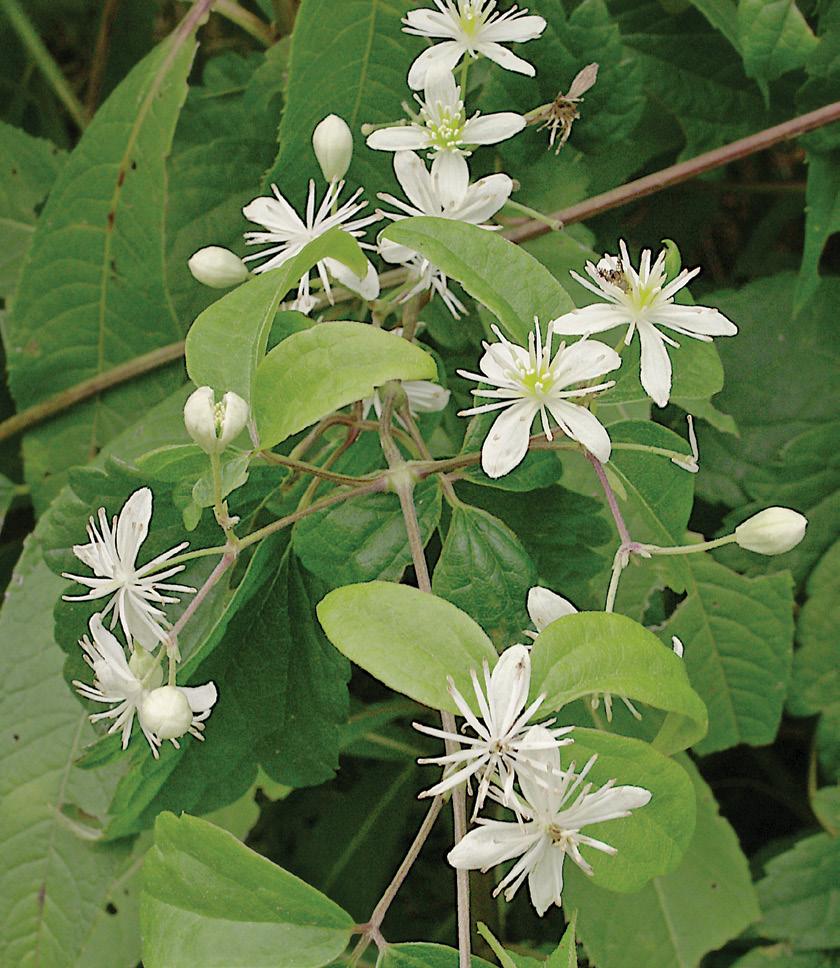

Virgin’s bower (C. virginiana) is a native clematis that produces frothy white flowers in late summer and attractive seed heads in autumn. It’s a great alternative to invasive species like sweet autumn clematis

(C. terniflora). Hardy to Zone 3. Western virgin’s bower (C. ligusticifolia) is a similar native.

Hops, for more than beer

Humulus lupulus is a vigorous, fast-growing vine that can provide excellent coverage over trellises and fences. It’s grown for its cone-shaped flowers and interesting foliage. Hardy to Zone 3, hops die back to the ground each winter but return with vigour in spring. The female plants produce the aromatic cones used in brewing, but even if you’re not into beer, hops add texture and a slightly wild look to ornamental beds.

Virginia creeper and its fiery fall show

If you're looking for a vine that provides coverage and seasonal drama, Parthenocissus quinquefolia delivers. This native vine is incredibly hardy to Zone 2 and will cling to walls and fences without support. Its green summer foliage turns brilliant crimson in autumn. Be aware that it can be aggressive, so it’s best

suited to larger spaces or areas where you want full coverage.

In shady areas, Aristolochia macrophylla, also called Dutchman’s pipe, is a standout. With large, heartshaped leaves, it forms a lush screen that’s perfect for privacy or for softening the look of outbuildings. While the pipe-shaped flowers are modest and often hidden, the dense foliage is the main draw. Hardy to Zone 3 or 4, it’s a slow starter but becomes a reliable perennial once established.

Climbing hydrangea for patience and payoff

Hydrangea anomala subsp. petiolaris is a self-clinging vine with large, flat, lacecap-style white flowers and exfoliating bark that adds winter interest. It's ideal for north- or east-facing walls, tolerating considerable shade once established. Hardy to Zone 4, climbing hydrangea is slow to get going, but once rooted

in, it rewards with elegant, long-lasting blooms and dependable foliage. It’s an excellent choice for those who favour a more refined, classic look.

Lonicera species range from native vines like Lonicera dioica to cultivated varieties like ‘Mandarin’ or the long blooming ‘Goldflame’. Honeysuckle vines are not only fragrant but also popular with hummingbirds and bees. Many are hardy to Zone 4 or 5 and bloom from early summer into autumn. Some varieties can become woody and dense, so regular pruning keeps them manageable. You may want to avoid Lonicera japonica, which is invasive in some regions.

Trumpet honeysuckle (L. sempervirens) is native to eastern US. It performs well in many southern Canadian gardens. It blooms with red-orange tubular flowers that attract hummingbirds. Less aggressive than non-native honeysuckles.

While technically annuals, sweet peas (Lathyrus odoratus) deserve a place in ornamental gardens for their scent and delicate beauty. In Zones 3 and up, they can be direct-sown once the soil warms or started indoors for an earlier display. Provide a small trellis or string support and enjoy the continuous blooms from early summer to frost, especially if you keep picking them.

Campsis radicans, or trumpet vine, produces vivid orange-red flowers that hummingbirds adore. It’s hardy to Zone 5 and needs a sturdy support, as it can grow quite heavy and rambunctious. Once established, it's drought-tolerant and low-maintenance – but give it space, or it may spread by root suckers.

Wisteria is the dream vine for many gardeners, with its pendulous, fragrant blooms and elegant habit. However, not all wisteria are suited to Canadian climates. Stick with Wisteria macrostachya, such as ‘Blue Moon’, which is reliably hardy to Zone 3 (or so I’m told). It may take a few years to flower, but the reward is worth the wait. Be patient and avoid overfertilising, which can delay blooming even longer. In warmer areas, it will grow big and strong enough to tear down a weak trellis, so make sure you have the foundation for it.

Celastrus scandens, or American bittersweet , produces clusters of orange berries in fall that persist into winter, adding interest long after flowers have faded.

It’s a native vine that tolerates cold well (Zone 3) and supports local biodiversity. You'll need both a male and a female plant to get berries. Be sure not to confuse it with the invasive Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), which is more aggressive and a threat to native species.

Akebia for something unusual

Akebia quinata, or chocolate vine, is a fast grower with delicate foliage and curious purple-brown flowers that smell faintly like chocolate. Hardy to Zone 5, it’s not widely grown in Canada but is gaining popularity for its ornamental value and shade tolerance. It’s semievergreen in mild winters but deciduous elsewhere.

Wild grape (Vitis riparia) is hardy and fast-growing, this vine produces small, tart grapes that are loved by

birds. It can cover fences or arbors quickly, but needs regular pruning to keep it in check. Hardy to Zone 2.

When selecting vines, consider your climate zone, the amount of sunlight the site receives, and the support structure available. Some vines twine, others cling with tendrils or suckers, and some need to be tied in manually. As with any plant, the first couple of years are the most important: water deeply, mulch well, and prune if needed to train growth in the desired direction.

Vines are more than just vertical fillers. They can frame views, create privacy, and provide shelter for wildlife. With thoughtful placement and the right species, vines will quickly become essential elements in your ornamental garden. k

While flowering vines can be beautiful and beneficial, some non-native species are invasive and can harm native ecosystems, outcompete local plants, and become difficult to control once established. These vines should be avoided in Canadian gardens:

1. Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica). This fast-growing vine smothers native vegetation and is considered invasive in parts of southern Ontario and British Columbia. It spreads aggressively and is banned in several jurisdictions.

2. Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus). Highly invasive in eastern North America, this vine strangles trees and spreads rapidly via birddispersed seeds. It’s sometimes sold as a decorative plant, but native Celastrus scandens is a better alternative.

3. English ivy (Hedera helix). Though widely planted, English ivy is invasive in mild regions, particularly on the West Coast. It damages buildings, trees, and infrastructure and suppresses native plant growth in forested areas.

4. Periwinkle (Vinca major, Vinca

minor). Often used as groundcover, periwinkle can escape cultivation and form dense mats in woodland settings, displacing native ground flora. It’s especially problematic in parts of southern Ontario and British Columbia. If you do grow it, keep it away from natural forests.

5. Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata). Though not widespread in Canada yet, kudzu has been found in southwestern Ontario. Known as “the vine that ate the South” in the U.S., it grows at an astonishing rate and should never be planted.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Imagine a romantic, story-book cottage in the woods. Does it have vines growing up it?

If you’ve heard from roofers, bricklayers or pest-controllers – or if you are one – you are probably thinking of the many warnings you’ve heard. Forget them for a moment. Growing vines on your house can be safe and beneficial, if you choose the right species and keep up with maintenance. For homes with wood siding, old mortar, or limited airflow, it’s better to use a support structure that keeps vines off the actual wall. In other situations, with regular care, vines can add natural beauty and ecological value.

1. Natural insulation. Vines like Virginia creeper and Boston ivy can act as a thermal blanket. In summer, they provide shade, reducing cooling costs. In winter, deciduous vines drop their leaves and let in sunlight while offering an extra layer of air insulation against walls.

2. Habitat and biodiversity. Climbing plants offer shelter and food for birds and insects. Honeysuckle and native clematis attract pollinators and songbirds.

3. Aesthetic appeal. Vines add lush greenery and visual softness to buildings. Some, like climbing roses or wisteria, can become centrepieces of the landscape.

1. Damage to masonry. Clinging vines such as English ivy (Hedera helix) and Boston ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata) use adhesive pads or aerial roots to attach to surfaces. While these won’t damage sound brick or stone, they can worsen existing cracks or pull off loose mortar, particularly in older buildings.

2. Pest and moisture issues. Vines can harbour moisture against walls, increasing the risk of rot in wood structures and encouraging insects. In areas with high humidity or poor airflow, this can be a real concern.

3. Maintenance. Vines grow fast. Without regular trimming, they can climb into eaves, gutters, and under shingles, leading to blocked drainage or structural issues. k

If you find yourself short of gardening space, it might be time to add height to your vegetable garden. Adding height – growing vertically – is a simple way to harvest more from the same amount of garden space. This vertical growing is easy to do with vining crops. Grow vining veg upwards instead of letting the plants spread out at ground level. By directing growth upwards, you free up space at ground level to plant other things.

There’s nothing new about this idea. Think of staked tomato plants. If the tomato plants are staked upwards and not sprawling on the ground, space below is freed up for other crops such as shade-tolerant leafy greens. Beyond staked tomato plants, there are many other “vertical gardening” opportunities.

Let’s look beyond stakes and tomatoes for more vertical gardening opportunities. Then, I’ll share five crops that I like to grow vertically in my garden. Add vertical crops to the garden

There are many ways to support vertical, vining crops in your garden. They include: Fences. If you have a fence around your yard, it can be part of your vertical garden. Tie tomato plants to a chain-link fence. Or run twine along a board fence for cucumbers and other vining plants. I grow squash along the fence I share with my neighbour so that she can share in the harvest.

Self-supporting structures. Use stakes or wood to create self-supporting structures for vertical growing.

Examples include teepees and a-frames. (I use a combination of wire mesh, bamboo, and zip ties. They’re easy to find, and easy to assemble, with no special tools needed.)

Landscape features. Use features in your garden as support for veggies. I’m talking about arbours, pergolas, railings… even downspouts!

Plant material. Trees and shrubs work well too! I’ve harvested a big haul of squash from vines that grew up my cedar hedge. My runner beans make their way from a trellis right up into an apple tree above… and look great!

Five versatile vine crops to get started with

1. Great cucumber substitute

Cucamelon (Melothria scabra), a.k.a. Mouse Melon, Mexican Sour Gherkin

If you have an on-again-off-again relationship with cucumbers…if poor pollination, wilt, or cucumber beetles have you down, try this bulletproof crop. This cucumber relative has smaller leaves and fruit, but is a vigorous grower that easily climbs a trellis. The small, thumbnail-sized fruit are cucumber-like, with a bit of citrus. Eat fresh, or make into pickles.

2. Peas please

Vining peas (Pisum sativum)

If you've grown bush-types peas, you might not think of peas as a vertical vegetable. For vertical gardening, get vining-type peas, which grow 6 to 8 feet tall. ‘Tall Telephone’ is a well-known variety. Peas are a versatile crop because in addition to the peas, you can eat young shoot tips, tendril, and flowers.

3. Awash in squash

Tromboncino squash (Curcubita moscata), a.k.a. trombetta

Tromboncino squash is a garden standby for me. Young fruit make an excellent summer squash, while those left to mature store well as winter squash. This squash has a vigorous vining growth habit, making it a winner for vertical growing. (Remember, some summer squash have a bush-like habit.) Another plus: Like its cousin the butternut squash, tromboncino isn’t both-

ered by squash vine borer. When it comes to versatility, remember that you can eat more from the plant than the fruit: shoot tips are edible too… and someone recently gave me a jar of squash stem pickle!

4. Full of beans

Runner beans (Phaseolus coccineus)

Runner beans are a great way to add height to a garden. Grow them up trellises, garden structures, and tall fences. Runner beans do better than pole beans in cooler, maritime climates – and they even tolerate partial shade. I fell in love with them when I worked in the UK, and saw them widely used. The flowers are edible. And an added bonus is that they’re a magnet for hummingbirds. I plant mine where I can watch for hummingbirds from my kitchen window. One of my favs is ‘Painted Lady,’ which has a red-and-white flower.

5. Towering tomatoes

Grow “indeterminate” tomato varieties for training upwards. The vines get longer and longer all summer. (Bush-type, determinate tomatoes don’t.) If you pinch off side shoots, you can create a very tall, skinny tomato plant. While most people think of growing tomatoes upwards… some gardeners also let them dangle down. Imagine a curtain of tomato vines coming off a lowroofed shed!

When my daughter, Emma, decided to grow 100 tomato varieties in our suburban garden, space (lack of space!) was a big problem. Intensive vertical tomato growing is the solution. She grew walls of tomato plants up twine. In so doing, she could cut back the space between plants by over half.

Save space, not time

Growing vertically frees up space for more plants. It cuts back on bending when harvest time arrives. But it’s not less work. That’s because vertical growing entails staking, trellising, and tying. Not a bad trade for the extra harvest from the same space.

Horticulturist Steven Biggs specializes in home food gardening. Find his edible gardening courses, and books about growing lemons, figs, and olives in cold climates at FoodGardenLife.com.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Grapes may not be the first fruit you think of for a Canadian garden, but with the right cultivar and care, they can be a productive and beautiful addition across much of the country. From coastal British Columbia to the Prairies, Ontario and Quebec to Atlantic Canada, gardeners can successfully grow grapes for fresh eating, preserves, juice, or even smallscale winemaking.

Selecting cold-hardy grape varieties

Your hardiness zone will play the biggest role in determining what types of grapes you can grow. Many popular table grapes, like ‘Thompson Seedless’, aren’t suited for most of the Canadian climate (though you may succeed at or above Zone 6). Instead, choose varieties bred specifically for cold climates. Most of these are hybrids developed in northern US states or here in Canada.

Prairie-hardy varieties:

‘Valiant’. Developed in South Dakota, extremely hardy (to -35 Celsius), productive, and great for jelly or juice. Mid-season ripening.

‘Bluebell’. Similar to Concord in flavour, early ripening, very hardy, seeded table grape.

‘Edelweiss’. Early season green grape with mild flavour, can be used for table, juice, or wine. May need winter protection in colder zones.

‘Swenson Red’. Red, mid-season, good table quality, but more diseaseprone; needs some winter care.

For southern Ontario and British Columbia:

‘Frontenac’ A wine grape developed at the University of Minnesota. High sugar content, vigorous growth.

‘Somerset Seedless’. Hardy to about -30 Celsius, red seedless grape for fresh eating.

‘Concord’. The classic juice and jelly grape; grows well in milder Canadian zones.

‘Niagara’. A green grape popular in Ontario vineyards for white juice and wine.

Check with a local nursery to confirm what thrives in your specific region.

Site selection and soil preparation

Grapes need full sun, at least six to eight hours per day. Choose a southfacing slope or wall, especially in colder regions, to maximize heat and light. Avoid frost pockets and poorly drained soil.

Grapevines prefer slightly acidic to neutral soil (pH 6.0 to 7.0). If you are unsure of the pH of your soil, do a soil test first. Good drainage is critical. Amend clay-heavy soils with compost or sand if needed.

Planting and early care

Plant grapes in early spring once the soil is workable. Space vines 6 to 8 feet apart for good airflow and light. Water deeply at planting and keep the soil evenly moist during the first growing season. Mulch can help retain moisture and suppress weeds, but keep it a few inches away from the base of the vine to prevent rot.

Pruning: the key to grape production

Grapes fruit on one-year-old wood, so annual pruning is essential for

productivity. In fact, you’ll remove up to 90 percent of the previous year’s growth each winter.

Year 1: Focus on building a strong trunk.

Year 2: Establish permanent arms or cordons using your chosen trellis method.

Ongoing: Prune each winter while the plant is dormant. Use spur or cane pruning depending on your trellis style.

See the sidebar How to prune a grapevine for full instructions.

Pest and disease management

While grapevines are relatively low maintenance, they can be vulnerable to a few pests and fungal diseases, especially in humid regions.

Common issues:

Downy mildew. Yellow spots and fuzzy patches on leaves. Avoid overhead watering and prune to allow airflow. Copper fungicides may help. Powdery mildew. Appears as white dust on leaves. Sulphur-based fungicides or baking soda solutions can suppress it.

Black rot. Black lesions and shrivelled fruit. Remove infected material and use fungicide preventatively.

Grape berry moth. Larvae feed inside of grapes. Remove infested fruit and consider pheromone traps. Grape berry moths aren’t much of a

problem in the home garden unless you live in an area with vineyards. Keep all grape litter cleaned up.

Japanese beetles and leafhoppers. Skeletonise leaves or reduce vigour. Hand-pick beetles or use floating row covers.

Proper spacing, air circulation, pruning, and good sanitation (removing fallen leaves and fruit) go a long way toward prevention.

Winter protection