2 minute read

SWAMPED

Wakodahatchee: It’s a word from the Seminole language meaning “created waters.” That’s because in 1996, Palm Beach County’s Water Utilities Department did just that: create a swamp on 50 acres of unused land as a way to treat wastewater for eventual use in agriculture and irrigation. At the time, the project was hailed as a novel alternative to industrial modern sewage treatment—but it’s a process as old as the Everglades themselves.

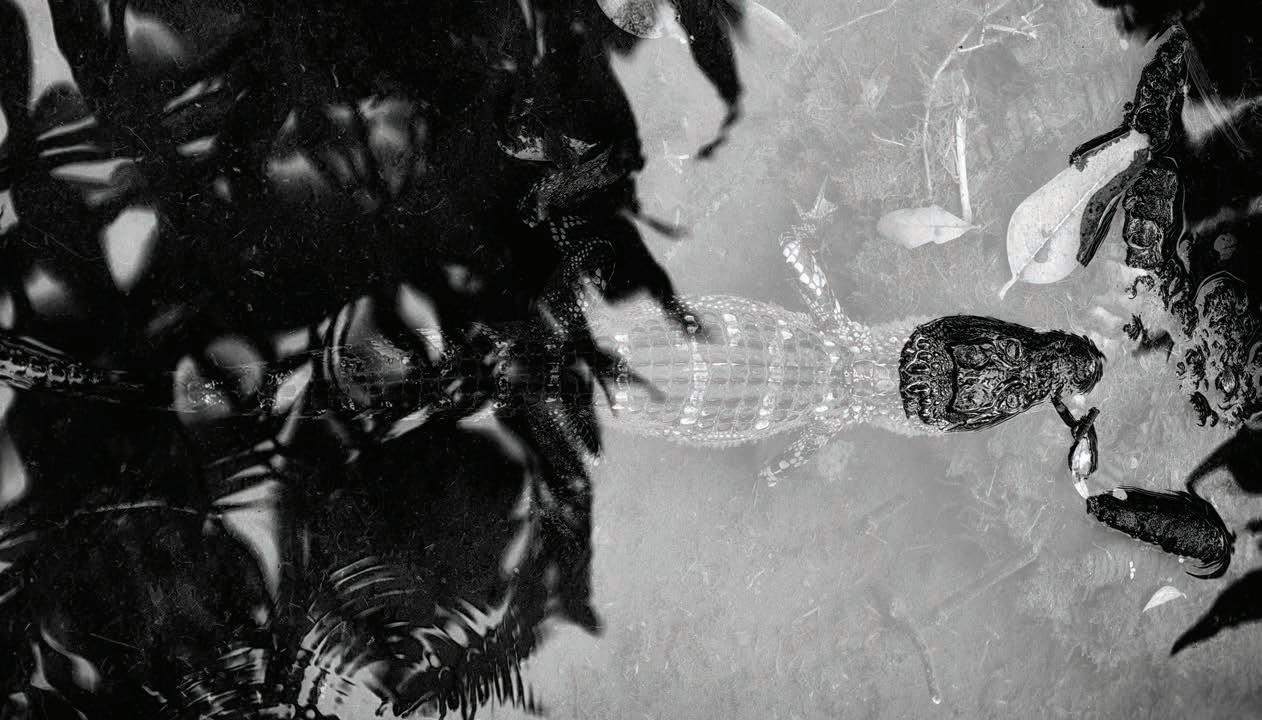

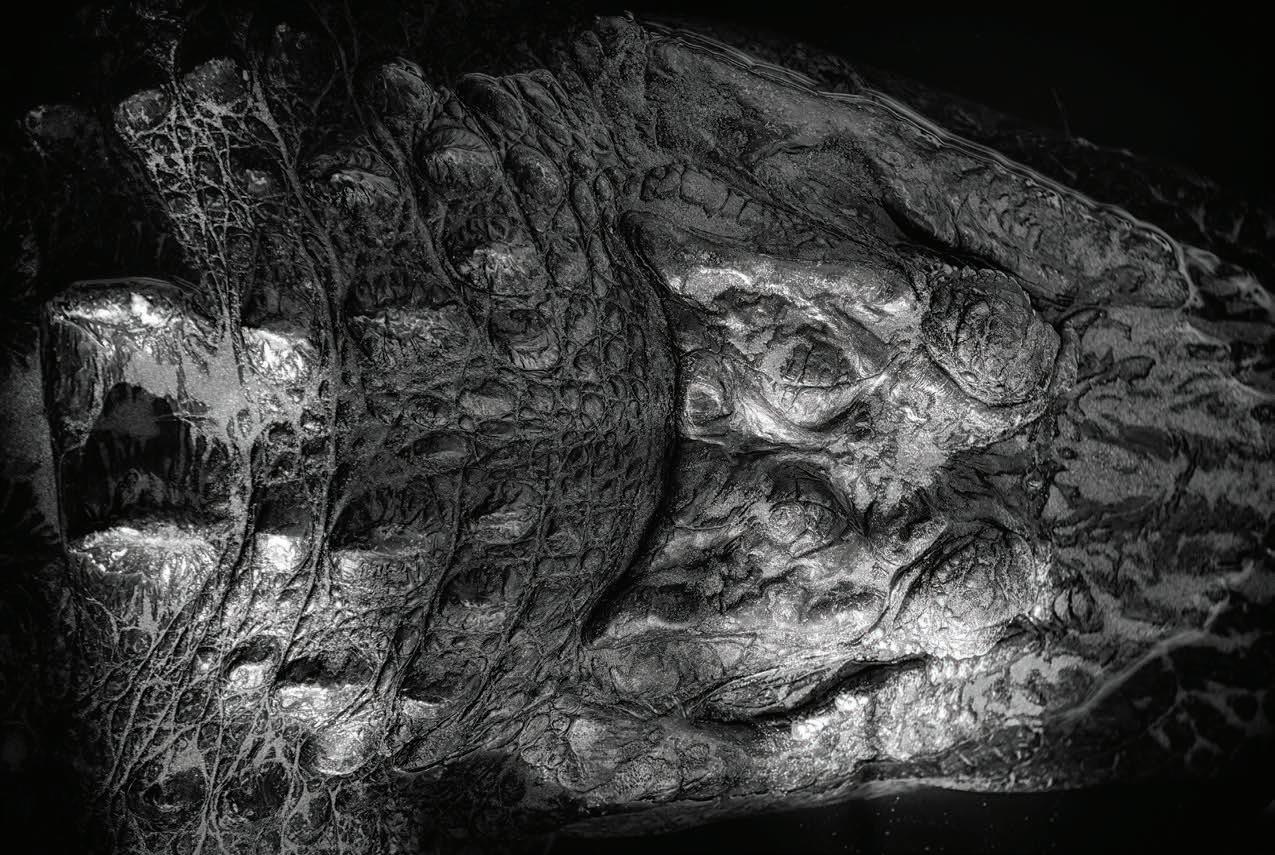

Approximately 2 million gallons of treated wastewater flows through the Wakodahatchee Wetlands daily. The swampy waters act as a percolation pond, returning billions of gallons of fresh water back into the local water table over time. They also support ever growing numbers of birds, alligators, turtles, fish, and

other wildlife—not to mention insects and native flora—that thrive in and around the nutrient-rich waters.

Photographer Jerry Rabinowitz first started photographing the Wakodahatchee in 2015. “I had been there before but not really to photograph,” he recalls. “I lived close to there at the time, and we started to walk there for exercise. Being a photographer, I brought my camera. I was not a wildlife shooter, but more of a nature guy.”

Over time, Rabinowitz returned to the wetlands and its threequarter-mile boardwalk with his cameras and lenses to capture a variety of vignettes—open-water ponds, emergent marshes, shallow shelves, grassy islands, and tree canopies among them. “As I started to document there, I began to realize

that there was something special. It became an intimate experience. I kept going back because the place changed by the time of day, season, and weather. Each time was a new experience,” he explains, describing what he calls a “hidden Eden that exists on the other side of a suburban fence.” “As I walked and photographed, I discovered the layering of the wetlands becoming more distinct,” he adds. “A cycle of life existing on the surface, in the air, and beneath the purifying waters.”

Rabinowitz has collected his images into a book, aptly titled Created Waters. His black-and-white photographic studies celebrate the successful merger of sustainability and nature. “Wakodahatchee restores some of what we have lost through development,” he says. “It is the beauty, steeped in underlying purpose, that causes me to journey, reflect, photograph, and embrace this small marvel in my city of Delray Beach.” «

“As I walked and photographed, I discovered the layering of the wetlands becoming more distinct. A cycle of life existing on the surface, in the air, and beneath the purifying waters.” —Jerry Rabinowitz