16 minute read

EVERYDAY HEROES

Francky Pierre-Paul founded nonprofit A Different Shade of Love.

MEET SIX PALM BEACH COUNTY RESIDENTS WORKING TO MAKE OUR COMMUNITY A PAY-IT-FORWARD PARADISE

By Sam Kerrigan

Hitting Home

After sleeping on the streets as a teen, Francky Pierre-Paul uses his second chance to care for neighbors in need

Kicked out of his house at the age of 16, Francky Pierre-Paul found himself couch surfi ng and sleeping on park benches. “It was demoralizing,” he recalls. “I hated it, and I hated myself.”

He says it was like having two identities: At night, he was homeless and alone with nowhere to turn. But during the day, he was at school and surrounded by friends—masking his feelings of depression and loneliness.

“That’s why I’m so big on changing the perspective of homelessness and how people view those who are struggling,” Pierre-Paul says.

Now, as an advocate, Pierre-Paul helps the more than 1,500 people experiencing homelessness in Palm Beach County. He often fi nds himself back in those same parks he once called home, passing out food and personal care items to the people living there.

“My goal is to fi gure out why they are out here so I can share that story with the community and try to get them help,” he says.

His nonprofi t, A Different Shade of Love, holds events around Palm Beach County, providing clothes, shoes, haircuts, and showers. It’s the small things, Pierre-Paul says, that help people who are experiencing homelessness feel like they are a part of the life going on around them.

“What I’ve realized about our homeless neighbors on the street is that they’re voiceless, and that’s because of us in the community,” PierrePaul admits. “We tell them, ‘You’re not allowed to do this, or you’re not allowed to do that.’”

It’s what he was told (and how he lived) for

Pierre-Paul cares for people experiencing homelessness in Palm Beach County.

too many years. But things are different for Pierre-Paul now, and he credits the bulk of his success to his wife. “I feel like she’s my angel on Earth because she’s more than a wife to me— she’s also a counselor, a best friend, a pat on the back, and a smile when I need it.”

The couple’s two young children also motivate Pierre-Paul to continue his mission. “I’m able to teach them the values of life and the importance of waking up and inhaling and exhaling and appreciating each moment,” he says.

His journey has been brutal at times. But Pierre-Paul says that through it all, he’s found his purpose—and he’s not taking his second chance for granted. “If I can change one soul before I leave this Earth,” he says, “then I feel like my job here while I’m just passing by is not null and void.” (adifferentshadeofl ove.org)

Sweet Talk

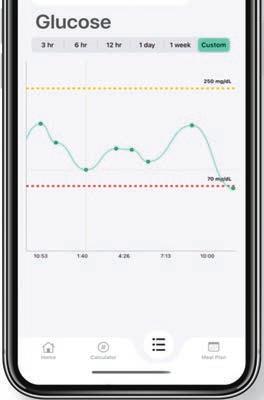

How teenager Jake Zur used his diabetes diagnosis to build an app that’s helping patients everywhere

When then-17-year-old Jake Zur was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in November 2020, something as simple as a Sunday morning doughnut stopped as a Sunday morning doughnut stopped being a sweet treat and instead became something to be charted and analyzed. “I was managing my sugars on spreadsheets and making huge lists of everything I ate,” he recalls. “It just took way too long.”

Zur searched for a simpler solution, but none of the diabetes management tools he tried did the trick. So, the senior at The Benjamin School in Palm Beach Gardens decided to build his own app called SweetSpot–The Diabetes Manager.

Mixing technology with his diagnosis was a no-brainer for Zur, who plans to major in computer science in college and has spent a summer as a programming data analysis intern at Jupiter’s Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience. It took him about four months to develop SweetSpot, but he used his tech know-how—plus some medical research, YouTube videos, and family support—to bring the app to life.

Available for free on the Apple App Store, SweetSpot offers a trio of functions: a carb calculator, a glucose log, and a meal planner.

Jake Zur’s SweetSpot app gives people with diabetes a simple way to track their food intake.

Zur is hopeful the app will help other people with diabetes and says that getting it into the hands of those who really need it has been the sweetest part of the process. “I just want to get it out to [as many] people as possible,” he adds. “I’m always updating the app, trying to make it the best for users. The fact that I can possibly help other people learn to manage their diabetes with this app is great.”

He hopes others who are struggling with a diabetes diagnosis will be empowered to manage their blood sugars and to understand that it’s a learning process that takes practice. Sometimes they’ll be high and sometimes they’ll be low, but eventually, Zur says, they’ll fi nd their sweet spot.

Diane Buhler and her crew clean Palm Beach’s shoreline, bucket by bucket.

Clean Coast

South Florida transplant Diane Buhler is healing her heart and home—one bucket of trash at a time

Diane Buhler had traveled from New York to South Florida on diving trips for decades, using the underwater world to escape the crush of the concrete jungle. But after losing friends during the September 11, 2001 attacks and supporting relief efforts at Ground Zero, she left Wall Street for West Palm Beach. “I needed to heal, and I needed to be by the ocean,” she says. “That’s my happy place.”

It wasn’t until Buhler became a full-time resident that she realized her happy place needed healing, too. “I found an ocean that needed me and animals that needed help because of the inundation of plastics and trash,” she says.

Buhler started organizing monthly beach cleanups with the help of the Solid Waste Authority, but she soon learned that once-amonth sessions weren’t enough to keep up with the amount of waste washing ashore. “We would leave a beach after one of those cleanups and the trash was still coming in with the winds,” she recalls. “I realized then and there I needed to do more.”

Buhler offi cially founded her nonprofi t, Friends of Palm Beach, in 2014 with the mission of cleaning our beaches. But her organization does more than that; it’s also a transitional work program that recruits clients from The Lord’s Place and Vita Nova, local outreach agencies that help the homeless and aged-out foster children land on their feet. “This is a safe space,” she says. “It’s hard work, and if you’re willing to show up and do the job, then I’ll keep you.”

Now her small but dedicated crew cleans seven-and-a-half miles of Palm Beach’s coastline fi ve days a week and also works to educate the community about the impacts of pollution. On average, Buhler and her crew remove 750 pounds of trash each week—the equivalent of 1,600 pieces of trash per day—and 80 percent of that trash is nonbiodegradable plastic. To date, Buhler says she and her crew have removed more than 230,000 pounds of trash from Palm Beach’s shores.

“I had no idea the amount we were going to collect,” she admits. “I knew I was going to make a dent, but it’s huge what we’re able to get. Unfortunately, it’s still only a small percentage of what is out there.”

What’s most rewarding, Buhler says, is seeing her crew making a difference every day. “They’re gaining a respect and an education about the environment and the community they live in and they’re taking that back home and buying differently and cleaning up their world. We all need to lend a hand, even if it’s something as small as picking up one piece of trash a day or fi ve pieces a day—it all makes a difference.” (friendsofpalmbeach.com)

would leave

Sophie Meridien helps local youth find books that resonate.

By the Book

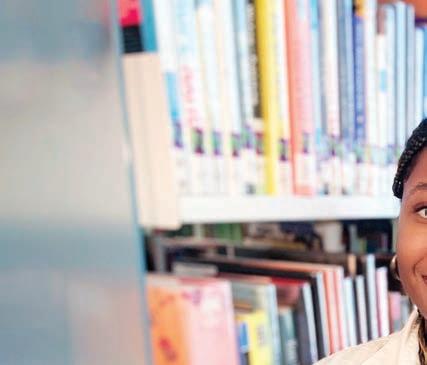

Sophie Meridien helps local kids connect to the stories of their lives

Whether she’s working at the Mandel Public Library of West Palm Beach or brainstorming ideas for her next novel, Sophie Meridien knows the power of story—and its ability to transport young minds. “I think it goes back to being in school and having a really awesome English teacher or a really awesome librarian and me wanting to be that for these kids,” she says. “I want to be a helpful adult in their life who they can talk to—not just about books but also about regular life stuff.”

Meridien has been a librarian at the Mandel Public Library for four years, helping teens reach their academic and social potential. During the school year, she runs the library’s teen homework center, where kids can come for free homework help, a healthy snack, or a friendly face. “Sometimes the kids don’t even have homework,” she admits. “They just need a safe place to hang out before their parents get home.”

Her efforts have not gone unnoticed: In 2021, Meridien was recognized as Florida’s Most Outstanding New Librarian of the Year by the Florida Library Association. “There were quite a few awards being handed out, and I remember thinking, ‘All these librarians are super incredible!’ To be a part of that was really awesome.”

But Meridien’s impact reaches far beyond the library’s bookshelves. She runs a monthly book club at the Pace Center for Girls, an alternative school for teenage girls in Palm Beach County. She has also coordinated author visits at a local juvenile detention center. “We’re trying to bring the library to teens who can’t make it to the library,” she says. “It’s one of the best parts of the job.” Meridien is on a mission to provide young readers with equal access to books—especially those that feature characters they can relate to. “Most of my teens come from our community and they don’t necessarily have a lot of books [with characters who] look like them,” she says. “I always want to make sure I’m buying the best books for them.”

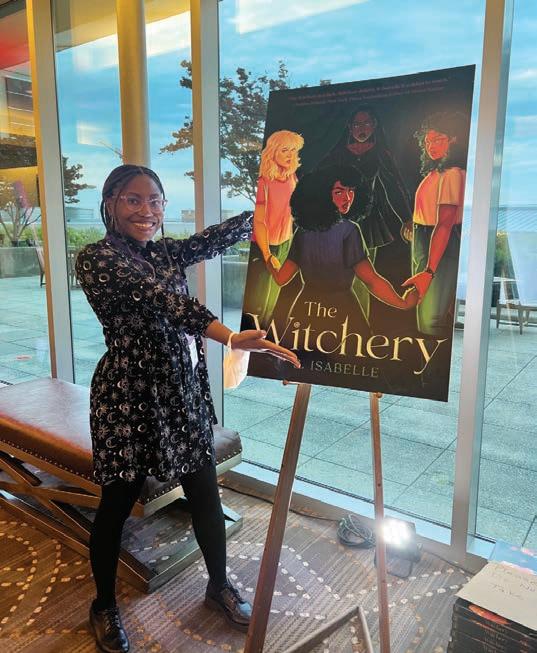

She’s writing the best books for them, too: Meridien’s debut novel, The Witchery, was released in late July. “In the fantasy realm, for me growing up, I couldn’t fi nd a lot of magical heroines who looked like me. That’s part of the reason I wrote this book.”

Meridien hopes the world of fantasy The Witchery offers can be an enjoyable escape for teenagers from all corners of the community. And when they step back into the Mandel Public Library, she’ll be there to help them continue writing their own stories.

Beach County. She has also coordinated author visits at a local juvenile detention center. “We’re trying to bring the library to teens who can’t make it to the library,” she says. “It’s one of the best parts of the job.”

Jack Hairston repairs bikes and donates them to children in need.

Free Ride

Bikes are a way for “Jack the Bike Man” Hairston to get lives (and smiles) rolling again

o you remember your fi rst bicycle? That’s the question Jack Hairston asks just about every person he meets—and he says the answer is usually a resounding ‘yes!’

“I don’t think they remember their fi rst toothbrush or fi rst pair of shoes or fi rst peanut butter sandwich,” Hairston says. “But they remember their fi rst bicycle.”

Better known as “Jack the Bike Man,” Hairston has been a pillar in the West Palm Beach community for more than 20 years. His nonprofi t gives away bikes to kids in need—and the holidays are his busiest time of the year. “We give away over 2,000 bikes at our Christmas party every year,” he says of his operation’s annual collection drive and repair efforts that could give Santa’s workshop a run for its money.

Hairston partners with other local charities to identify families that can benefi t most from a new set of wheels. On the day of the party, hundreds of volunteers descend on the bike shop to help make sure each kid rides off on a bike tailored to him or her. “A bunch of elves are down in the loading dock area, and they’re adjusting seats and whatever needs to be done so the bike is perfect for the child,” Hairston explains.

Hairston says it all started one day in 1999 when he was sitting on his front porch, watching a young man falling off his bike. He realized the kid’s brakes weren’t working. “I knew how to do that, and so I fi xed his brakes and told him to get out of here,” he recalls.

But there was no pumping the brakes on what would happen from that day forward. Word travels fast—especially among the kids in Hairston’s neighborhood, who continued to show up on his porch asking him to fi x their bikes. “It was an accident,” he admits. “I didn’t plan on this happening—I was retired and enjoying doing nothing.”

D

But he says he wouldn’t change a thing. These days, he enjoys educating kids on bicycle safety through his charity’s various programs. Recently, Jack the Bike Man moved his operations into a bigger workshop and programming space, thanks to a lead gift of $1.5 million from the Mary Alice Fortin Foundation.

Hairston says his organization will continue helping those who need it most—one bicycle at a time. “I’ve never seen anything as powerful as a kid’s smile when they get their fi rst bicycle,” he says. And at 80 years old, it’s those smiles that keep Hairston’s wheels turning. (jackthebikeman.org)

Allie Severino helps people experiencing addiction and homelessness find new hope.

Rise and Shine

After a turbulent youth, Allie Severino is helping others succeed

Arrested for drug traffi cking at the age of 17, Allie Severino faced a possible prison sentence of 120 years. She thought her life was over. “I even wanted to go to prison because I was convinced I couldn’t succeed on probation,” she says.

But Severino got a lucky break when the judge assigned to her case decided not to give up on her. “He saw something in me that I didn’t even see in myself at the time,” she says. “It’s people like him, who gave me a second chance, who allow me to live the life I live today.”

More than a decade later, Severino is sober and thriving in her new role as a homeless outreach specialist for the City of West Palm Beach. “They didn’t look at my past, they looked at what I was doing today and the woman I’ve become,” she says of her employer. “They believed in me and my ability to be an asset to the city.”

Severino admits the shift from her old life to her new one wasn’t easy; it took some time to turn things around (even after that fateful court appearance). “I was living on the street until I got my bed at the drug abuse foundation,” she recalls. “When I got there, I was like, ‘I don’t want to be here at all.’”

But Severino stuck it out, spending six months in rehab. She realizes now that her struggle was a key part of her growth. “If I didn’t struggle even in recovery like every other young person does, I wouldn’t have that knowledge to help others,” she says.

Today, Severino uses her own experiences to offer hope to people experiencing addiction and homelessness in West Palm Beach. “I know they feel like they can talk to me and not feel like I’m looking at them in a different way, because I’m not. I simply just want to help.”

Severino seeks to build trust fi rst. It’s the best way, she says, to truly assess the specifi c needs of each individual and get them connected to the right services. “What we do for them is navigate a very complicated system, whether that’s to help them get food stamps or disability or shelter placement,” she explains.

She says it’s the “boots on the ground” effort on West Palm Beach’s streets and in its parks that makes a difference. “We’re doing that hard work to make sure these amazing people can get to a point where they are self-suffi cient and able to live a happy life that they’re proud of,” she says.

Now—far from her life being over—Severino is on a positive path, both personally and professionally. She’s preparing to start social work courses at Florida Atlantic University to further enable her to help locals in need. “I just want to keep growing and doing a good job,” she says. “I know that if I’m able to continue to do well, then other people will know they can do it too.” «

key part of her growth. “If I didn’t struggle even