23

PMC Notes No .

The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art is an educational charity that promotes original research into the history of British art and architecture. It is part of Yale University and its activities and resources include research events, public lectures, publications, fellowships, grants programmes, and a library and archival collection.

PMC Notes, the Centre’s newsletter, is published three times per year.

Page 20

Georgian Provocations

Welcome 2 Events Calendar See cover wrap PMC

. 23

4

12 Fuseli’s

20

Notes No

Tudor Art, a Lively Story

Communist Murals at a Country House

Nightmare

Welcome to this issue of PMC Notes, which takes us from winter to spring. This period of transition, of course, is famously one of regeneration and reinvigoration, and these qualities are powerfully expressed in the programme of “New Directions” research seminars that we are running over the coming months. These highlight some of the most original approaches and subjects being pursued within the field of British art studies. Subjects being addressed by a sparkling array of speakers include food and the senses, the technologies of film and empire, indigenous objects, and art and artificial intelligence. We hope you’ll be able to join our conversation around all these lively topics: as always, you’ll find more details in the wrap-around events listing.

The articles we are publishing in this issue of PMC Notes also have the freshness and liveliness we associate with the transition to spring. In addition, they testify to the variety of ways in which the Centre promotes and disseminates new thinking on British art and architecture. Ella Nowicki’s fascinating article on the communist murals painted by Viscount Jack Hastings at Buscot Park, Oxfordshire, for example, emerges from our British Art in Motion undergraduate film competition. The launch of the competition in 2021 generated a series of remarkably mature, sophisticated, and visually stunning short films, all of which we screened at our inaugural film festival in October 2022. Ella’s film was one of these works and I’d urge you, having read her article, to watch her film along with those of her fellow contestants on our website and YouTube channel.

2

This issue also features a lively article on the impact and afterlife of The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli, written by my colleague Martin Myrone; it is based on a talk he gave as part of the Georgian Provocations Public Lecture Course we ran last autumn. I remember the talk well, not only for the brilliance of its contents, but also for the suitably gloomy and portentous music that greeted attendees as they walked into our lecture room. Its chilling thrum provided a nice example, I thought, of the ways in which we try and make British art as exciting and intriguing as possible for our audiences. Again, if you’d like to enjoy Martin’s lecture, and those given by the other contributors to Georgian Provocations, please go to the events recordings section of our website.

Our third and final feature is an article written by the art historian Christina J. Faraday on the subject of liveliness itself, to mark the publication of her new book Tudor Liveliness: Vivid Art in PostReformation England, which will be released in April. Christina’s book testifies to the continuing vitality and ambition of another, longstanding strand of the Centre’s activities: our book publications list, which has recently included the winners of both the 2022 Berger Prize and the 2022 Apollo Book of the Year prize. As you will quickly find in reading her article, Christina’s thinking and writing has all the liveliness of her topic; her similarly vibrant book is much anticipated and will be a perfect spring read.

The Centre itself will soon be pursuing its own form of renewal and regeneration, as it completes the process of appointing my successor. As many of you may know, I will be leaving the Centre in March, to take up a new role as the Märit Rausing Director of the Courtauld Institute of Art. I will do so having enjoyed every day of the decade I have spent leading this unique centre of research and learning. It has been both a privilege and pleasure to work with my lively, stimulating, and supportive colleagues in both Bedford Square and New Haven, and to engage with the passionate, knowledgeable, and ever-expanding community that the Centre serves to support. I look forward to watching the Centre continue to thrive and develop in the seasons to come.

Mark Hallett Director

3

Welcome

Tudor Art, a Lively Story

Christina J. Faraday explores how the rhetorical concept of “liveliness” sheds light on a lost mode of Tudor art criticism and appreciation. Her new book Tudor Liveliness:Vivid Art in Post-Reformation England will be published by the PMC in April 2023. Christina is Research Fellow and Director of Studies in History of Art, Gonville and Caius College, University of Cambridge.

For Tudor viewers, artworks were often “lively”. In the sixteenth century, this word referred to an especially potent kind of vividness – visual and textual – and came freighted with resonances from classical rhetorical theory. Rhetoric held a central place in the Tudor curriculum. Its guidelines for effective communication would have been familiar to everyone who had received a formal education, but also to many who had not. “Liveliness”, or enargeia to give it its technical title, was seen as an essential characteristic of effective communication. The use of the word “lively” about artworks suggests that they were seen as conjuring a realistic effect comparable to vivid speech.

Such a view runs counter to the traditional idea that Tudor England was hostile towards imagery, especially vivid imagery, partly a legacy of iconoclastic Protestant edicts. Indeed, Tudor artists’ enthusiasm for inscriptions and awkward efforts at perspective have often been seen as deliberate attempts to limit realism and avert idolatry. Yet looking at rhetorical ideas about “liveliness” reveals Tudor

5

artworks courting a kind of vividness dependent not on “naturalistic” artistic principles (single point perspective, proportion, and historical accuracy) but on detailed and multi-sensory depiction.

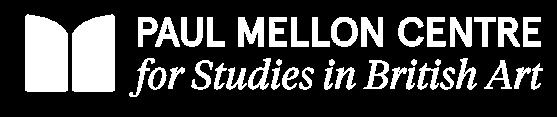

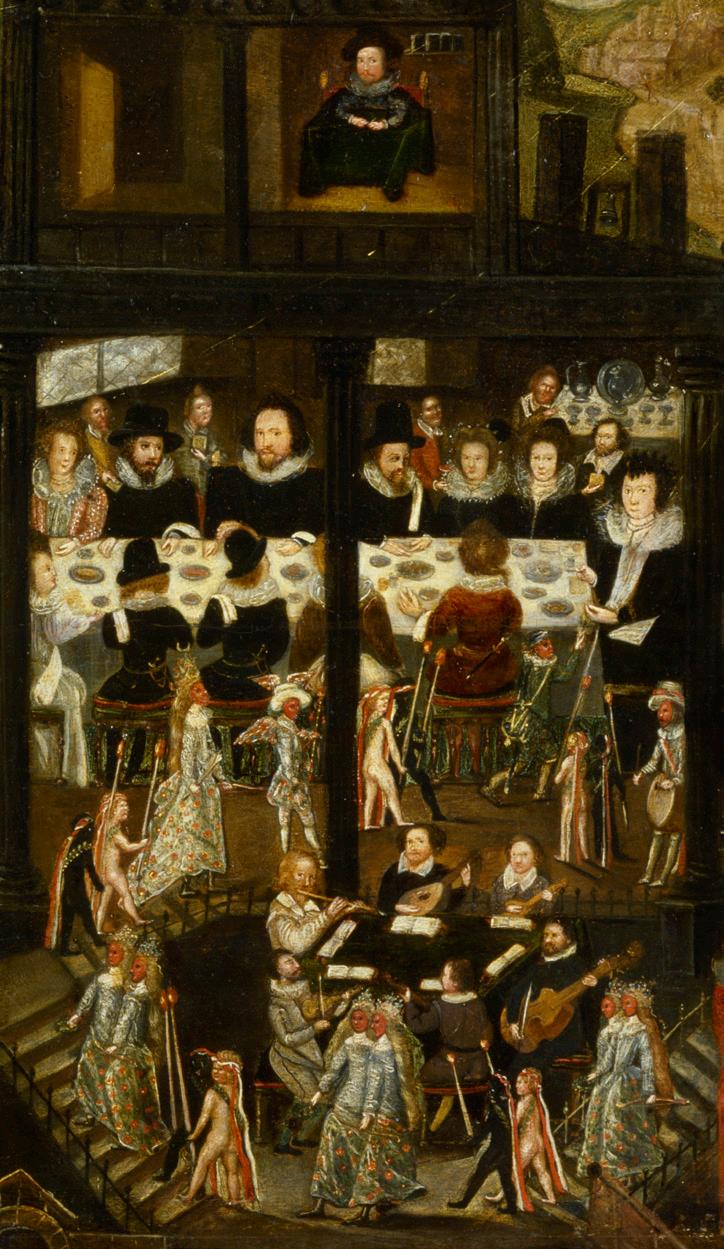

In what ways could Tudor artworks have been seen as “lively”? The extraordinary Unton Memorial of about 1596, now in the National Portrait Gallery, illustrates some of these principles. Designed to commemorate Henry Unton, Elizabeth I’s ambassador to France, the panel represents his biography through a series of scenes, Unton featuring multiple times. His life begins in the bottom left corner, where he appears as a baby in his mother’s lap, the shield of arms above her head revealing his illustrious family background. We are taken through his career at Oxford, his bravery in the Netherlands, and his diplomatic success in France. Counterbalancing his public life is a representation of his home at Wadley, opened like a doll’s house to reveal Unton at home: entertaining, disputing, and playing music with friends and relations. Finally, his funeral procession wends its way to the church and monument in the bottom left corner, the route lined with the grieving recipients of Unton’s charity.

In telling us the story of Unton’s life, the panel illustrates his virtues, commemorating him but also encouraging the viewer to follow his example. Distributing scenes of Unton’s life around a large-scale portrait, the panel mimics rhetorical advice for the vivid depiction of a person in “demonstrative oratory”, a genre used for the “praise and blame” of individuals. In this genre, the vivid description of the subject’s appearance, heritage, deeds, and virtues helps to win over an audience, convincing them of the subject’s virtues and encouraging them to lead a similarly righteous life. The panel’s multiple narrative, inconsistent perspective, and unrealistic heaping of scenes has often been characterised as anti-realistic. Yet, setting it alongside the principles of vivid, full description, we can see how, for viewers at the time, the panel would have presented a “lively” account of Unton’s life.

Art history’s focus on visuality can sometimes minimise the role of the other senses, particularly the sense of touch. Yet, an appeal to multiple senses was key to powerful, memorable speeches, and, by extension, images. The classical rhetorician Quintilian, whose handbook featured prominently in Tudor curricula, writes that a speaker “as a sort of salesman of eloquence, will allow the customer to see and almost to handle [paene pertractandum] all his most attractive maxims”.

6

7

8

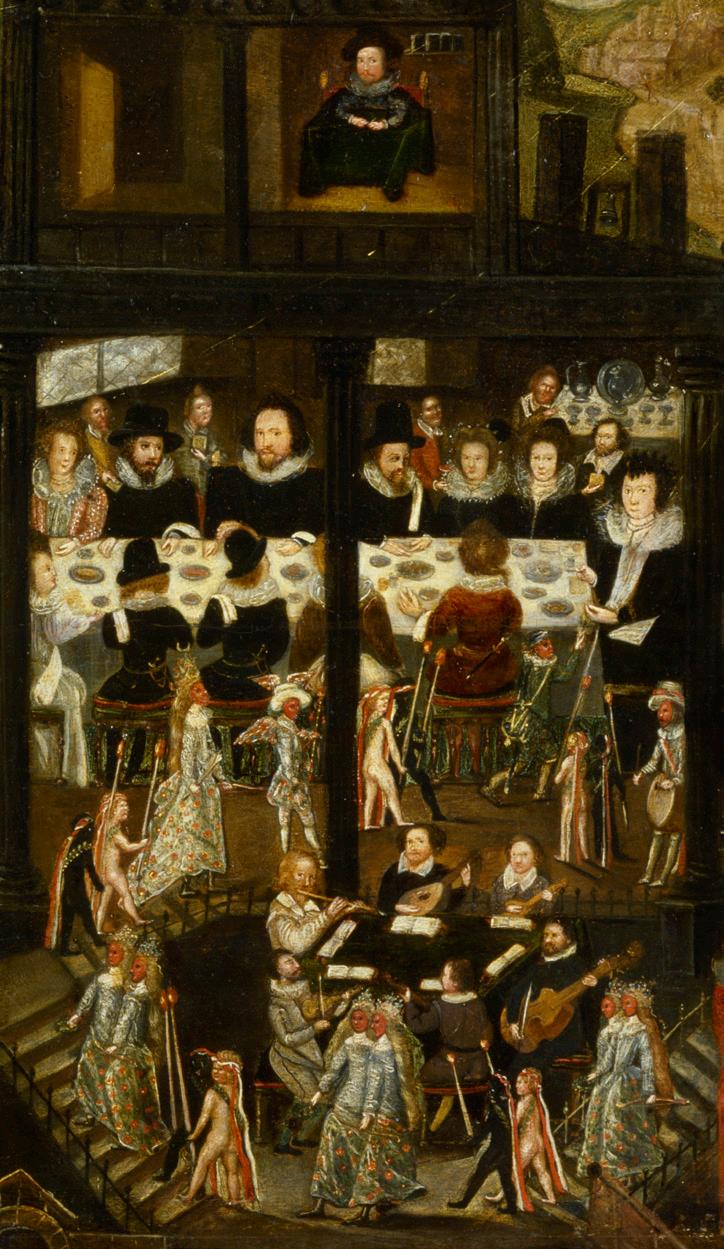

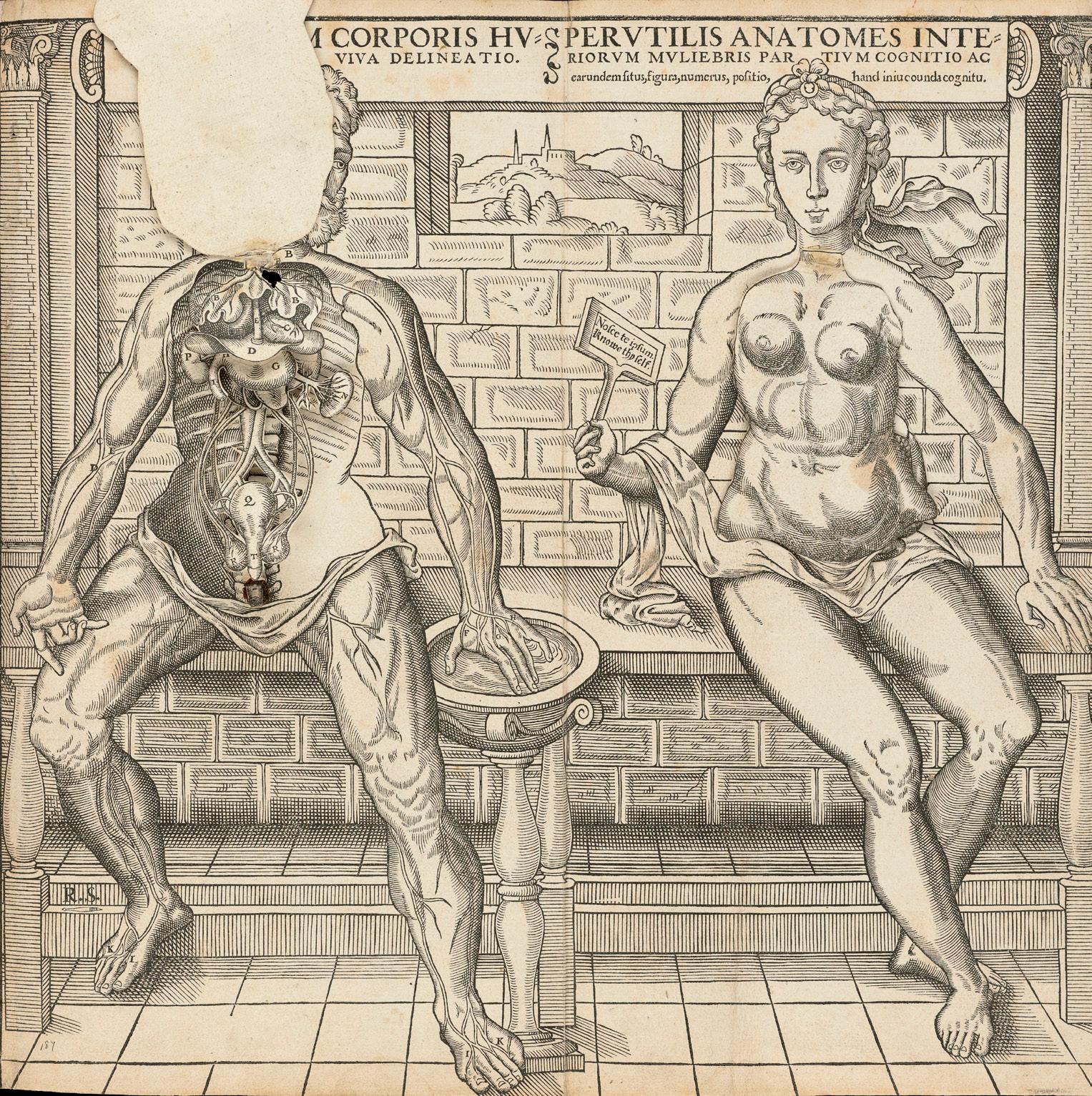

Touch helped the audience to “grasp” a point and images could also appeal to this sense. This was particularly true of interactive prints, once extremely popular, but only a handful of which now survive. One of the most intriguing was commissioned in the mid-sixteenth century by Thomas Gemini, a Flemish physician, copperplate engraver, and all-purpose rogue. At the front of his pirated edition of Vesalius’s anatomy textbook, Gemini incorporated an interactive anatomy print. Much like today’s “pop-up body books”, these prints enabled users to perform a paper dissection, lifting the flaps to “see inside” their own anatomy. Not only did this multiply the number of senses through which information entered the mind, but it also illustrated the process of anatomical discovery. This made anatomical information more memorable and vivid, making the viewer feel like an eyewitness to the unveiling of the body’s organs. This evocation of witnessing was vital to rhetorical liveliness. It could be achieved through detailed, sequential narration of events, as Quintilian recommends in his account of the invasion of a city:

No doubt, simply to say “the city was stormed” is to embrace everything implicit in such a disaster, but this brief communiqué, as it were, does not touch the emotions. If you expand everything which was implicit in the one word, there will come into view flames racing through houses and temples, the crash of falling roofs, the single sound made up of many cries, the blind flight of some, others clinging to their dear ones in a last embrace, shrieks of children and women, the old men whom an unkind fate has allowed to live to see this day… “Sack of a city” does, as I said, comprise all these things; but to state the whole is less than to state all the parts.

Although history and genre paintings on panel were few and far between in Tudor England, sequential narratives do appear in other media such as wall painting, plaster, and needlework. A case in point is the Parable of the Prodigal Son, from about 1600, represented at Knightsland Farm in South Mimms. Across four surviving scenes, the viewer observes the prodigal son’s revels, his bankruptcy, his nadir at the pig trough, and his return to his father. Although the story derives from the Bible, at South Mimms the figures are shown in contemporary dress, wearing slashed hose, codpieces, and ruffs. The houses too are of a Tudor type, with diamond windowpanes, reflecting the appearance of the houses and villages surrounding Knightsland Farm at the time when it was painted.

9

10

Two print sources have been identified as possible patterns for the paintings: one by Claes Jansz Visscher after David Vinckboons (1608) and the other by Gyles Godet (1566). Yet, even if these are the sources, the English artist was no slavish imitator. Visscher’s prints represent the story with consistently Dutch costume and landscape; Godet’s is more or less classical. The English paintings, by contrast, transfer the story to a setting more familiar to viewers in South Mimms. This can be compared to the rhetorical technique known as enallage, or the historical present tense: when past events are narrated in the present tense to emphasise their relevance and immediacy. By representing the parable in contemporary dress, the artist mimics preachers who used their sermons to link biblical stories with current events, underlining their ongoing relevance for the congregation. Furthermore, the paintings show the narrative unfolding scene by scene, allowing the viewer to witness the prodigal’s fall and salvation, and inviting them to draw comparisons with their own lives. These are just some of the ways that the rhetorical principles of “liveliness”, or enargeia, can be seen in Tudor artworks, revealing them to be a potent and persuasive source not only of moral lessons, but also of memory, knowledge, and entertainment. These parallels do not represent an act of conscious translation for artists or patrons; rather, rhetoric permeated their expectations of communication to such an extent, we can confidently argue that rhetorical ideas informed any attempt to see or be seen. In a culture where art criticism was almost non-existent, rhetoric provides us with a framework to talk about these issues in terms that people at the time would have recognised, re-enlivening their art, and thus restoring its vividness and vitality.

Pages 4 and 7

Unknown artist (possibly Richard Scarlett), The Henry Unton Memorial Portrait (details), circa 1596, oil on panel, 74 × 163.2 cm. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 710).

Page 8

“R.S.”, “Interiorum Corpus Humani Partium Delineatio”, woodcut with skin flaps lifted, bound in Thomas Gemini, Compendiosa Totius Anatomiae Delineatio, 1559 edition, 37 × 37 cm. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (EPB 2731/D/2).

Page 10

Unknown artist, East room of Knightsland Farmhouse, depicting the Parable of the Prodigal Son (details), circa 1600, wall painting. Knightsland Farm, Hertfordshire. Courtesy of Historic England Archive (BB84/02753).

11

Communist Murals at a Country House

Last year, Ella Nowicki participated in “British Art in Motion”, a new programme at the PMC that provided specialist training in filmmaking to ten undergraduate students who each produced a short film about a work of British art or architecture. This article is adapted from Ella’s film, which can be watched on our website.

In 2022, Ella graduated with a BA in History of Art from the University of Cambridge.

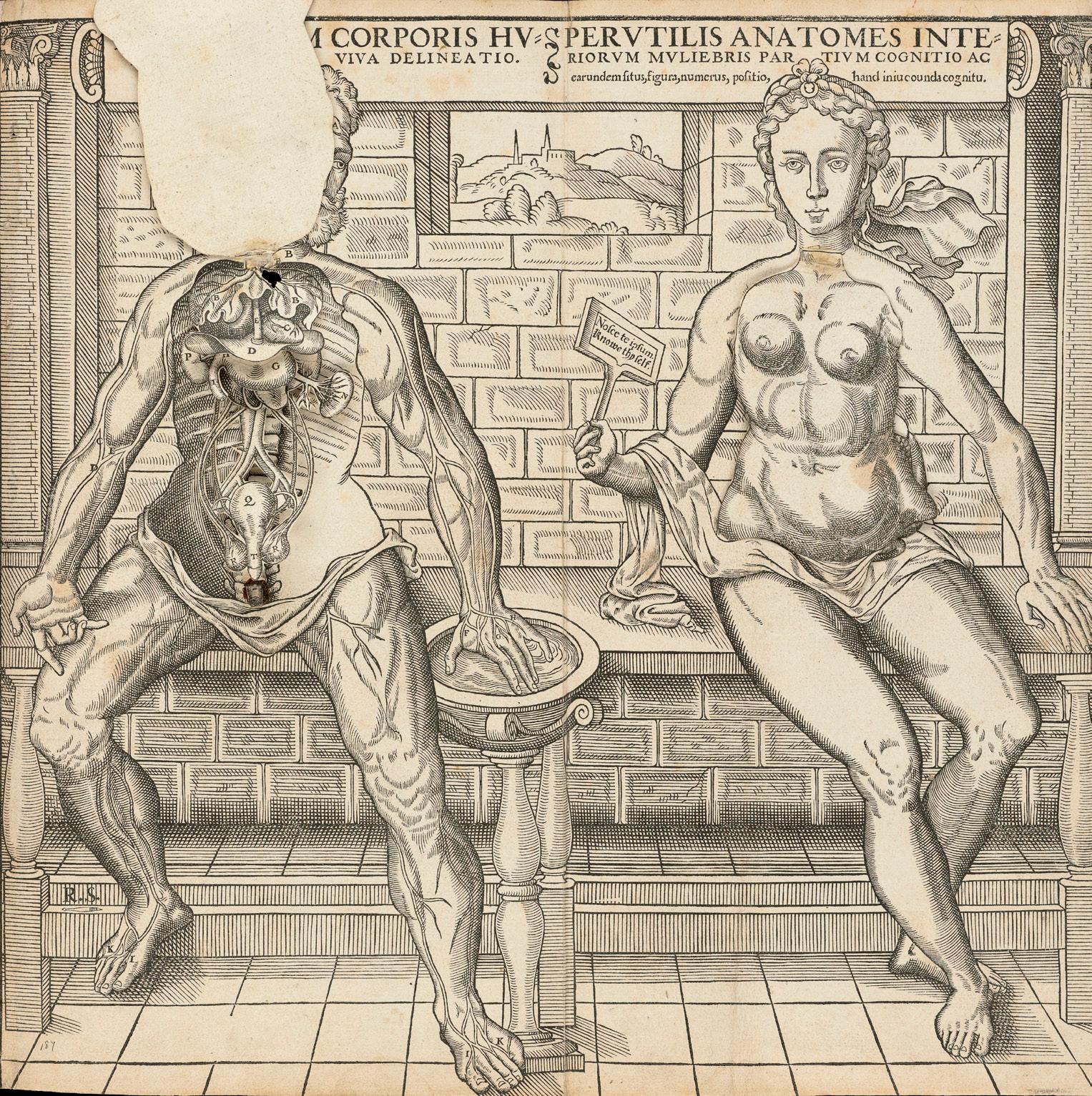

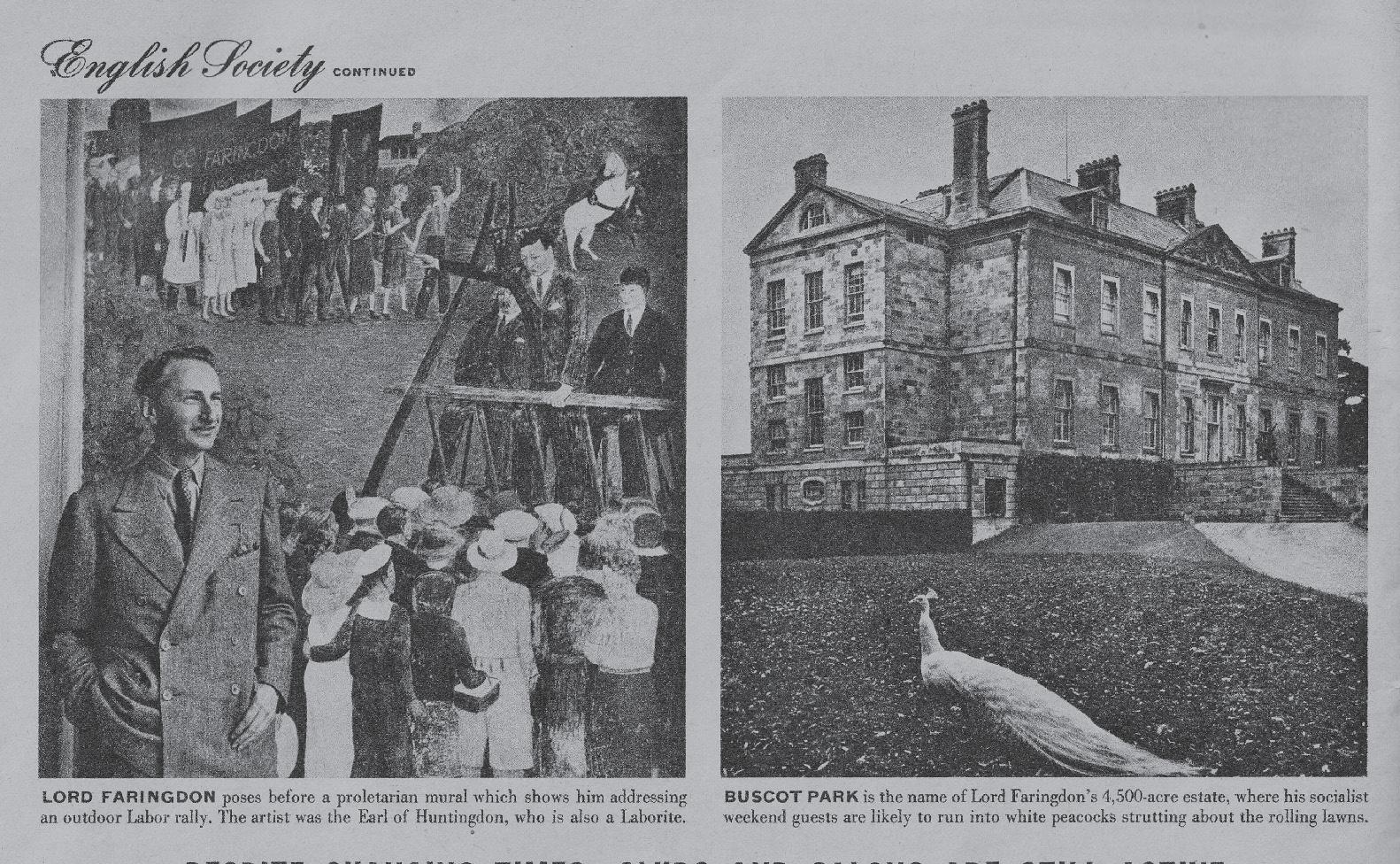

In 1937, Gavin Henderson, 2nd Baron Faringdon, commissioned a lavish and unusual fresco cycle for the pool house at his estate Buscot Park in Oxfordshire. The painter was Viscount Jack Hastings, who had trained with the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera and would become the 16th Earl of Huntingdon in 1939. Faringdon and Hastings were lifelong friends and Labour peers active in socialist causes. Balancing private humour and political content, Hastings’ Buscot Park frescos complicate the categories of both country house decoration and 1930s leftist muralism. They illuminate surprising encounters between North American mural movements and British art, and between radical politics and elite spaces.

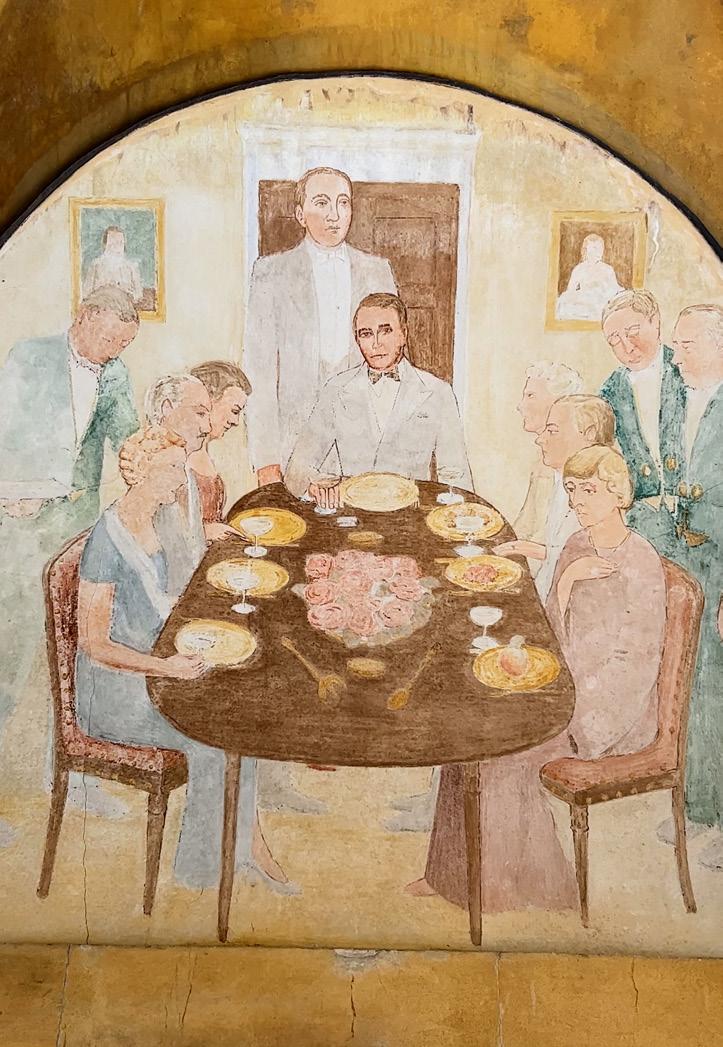

Painted in 1937–39, the frescos playfully illustrate life at a country house. Five sections depict recreation, showing tennis, golf, bathers by the

13

pool, a dinner party, and a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the gardens. Two further lunettes celebrate the farmers and gardeners whose labour sustained Buscot Park.

In the only overtly political panel, Lord Faringdon is shown speaking at a local Labour Party rally. His speech agitates the police horses in the background and energises a parade of Labour supporters, who carry the banner “Workers of the World Unite”. Faringdon had joined

the House of Lords as a Labour member in 1934, defying his family’s Conservative legacy. The diverse marchers allude to international leftist causes: the inclusion of a Sikh man affirms Faringdon’s support for Indian independence. Two whitehaired women represent the Quaker activists Poppy and Chloe Vulliamy, who arranged for Buscot Park to host child refugees from the Spanish Civil War in 1938. Faringdon was an early advocate for intervention on behalf of

14

Spanish Republicans fighting against Franco’s fascist troops.

Hastings had first come to leftist politics while working as an assistant to the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in San Francisco and Detroit in 1930–33. After studying with Henry Tonks at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, Hastings sought out Rivera to pursue his passion for muralism. Rivera viewed muralism as a “weapon” – as he wrote in 1932 – for communism. In the 1920s, Rivera had been instrumental in the

rise of state-sponsored murals in Mexico following the revolution. In the 1930s, he helped to catalyse a mural movement in the United States, which culminated in unprecedented funding for public art via the New Deal, a set of Depression-era relief programmes under Franklin D. Roosevelt. These North American murals often deployed a social realist style, featuring gritty depictions of economic inequality and heroic representations of labour.

Immersion in a robust community

15

16

of leftist artists in the USA – including Rivera, his wife Frida Kahlo, and the growing ranks of American muralists – led Hastings to embrace communist values. When he and his wife Cristina returned to England in 1934, Cristina joined the Communist Party and Hastings joined the Artists’ International Association (AIA), a group of communist artists and fellow travellers who organised exhibitions, fundraised to aid Spanish Republicans, and held seminars at the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ School in London. At the Marx Library in 1935, Hastings painted the fresco Worker of the Future Upsetting the Economic Chaos of the Present, in which a shirtless worker rips apart parliament and the church under the approving gazes of Marx, Lenin, and British socialists Robert Owen and William Morris.

While the Marx Library mural instructed students, artists, and workers about the coming revolution, the Buscot Park frescos entertained Faringdon’s guests with scenes of luxury. Mindful of their context, Hastings took a more subtle and self-conscious approach to politics, exploring the complexities and absurdities of his and Faringdon’s positions as leftist aristocrats. The frescos embrace the irony of Faringdon as a “red peer” who, according to a Daily Mail article from 1936, would “arrive at Westminster in a green chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce… and then, after railing against the

government, would return to his country mansion recently renovated at great cost”.

Such juxtapositions of aristocratic privilege and revolutionary politics endow the frescos with humour. Roger Vlitos, curator of the Faringdon Collection, notes that the moustachioed golfer in one lunette has been read as Stalin holding the world in his hands like a golf ball. While the likeness is inexact, Faringdon was given a lock of Stalin’s hair on a state visit to Moscow. This ambiguous portrait brings politics into view while resisting serious, fixed political meanings. The nearby figure wearing Robin Hood’s feathered cap is a selfaware joke, as Hastings claimed to be Robin Hood’s descendant. The Robin Hood outfit conveys a sincere belief that Hastings and Faringdon could take from their class and give to the poor, yet also hints that their leftist identities could come across as a kind of masquerade.

Even Hastings’s Labour rally panel is underpinned by irony, making light of the fact that the Faringdon Labour Party was in reality too small to organise such a parade. Exaggerated social realist tropes – Faringdon’s power pose and the rearing police horses – contrast with the lack of actual Labour support in the towns of Faringdon and Abingdon, where the campaign Lord Faringdon sponsored for his secretary, Frank Bourne, to run as MP had been unsuccessful. Faringdon had himself photographed

17

with this panel for Life in 1943, using it to broadcast both his sense of humour and sincere socialist commitments.

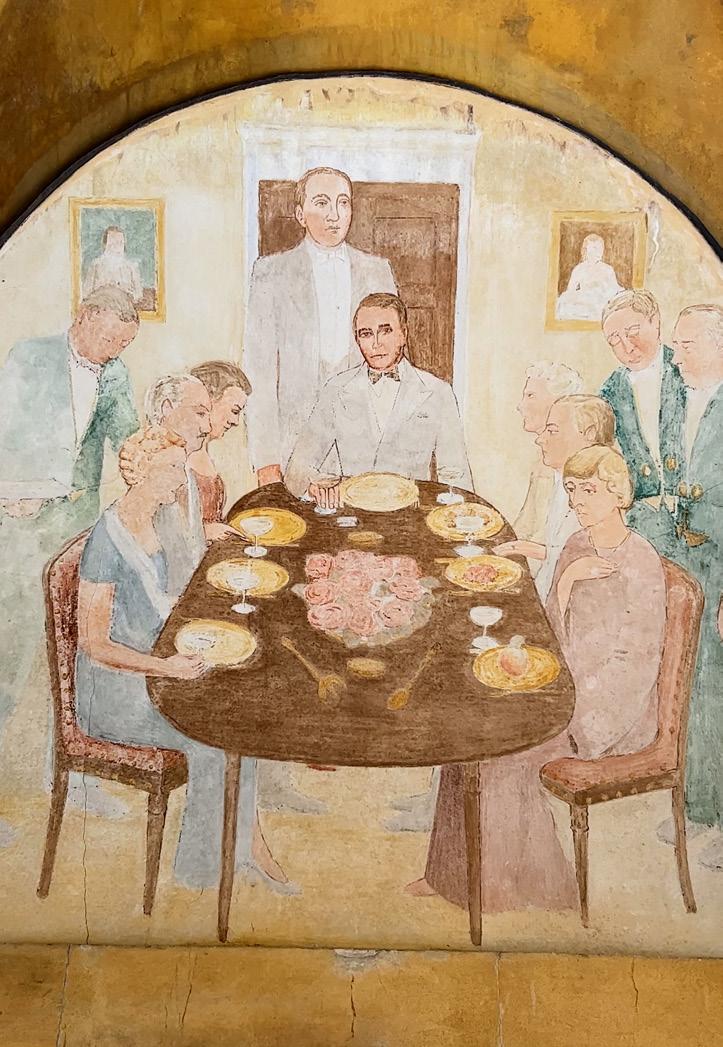

Another lunette depicts Faringdon and friends dining on gold plates in a composition that recalls Rivera’s caricature of American capitalists feasting on gold tickertape in Wall Street Banquet (1928). Hastings turned Rivera’s satirical eye inward and diffused his harshness, resulting in a panel that celebrates Faringdon’s friendships as much as it ironically contemplates aristocratic excess.

This mixture of sincerity and humour, and revolutionary and aristocratic imagery, sheds light on the condition of muralism in Britain in the 1930s. Murals in the USA and Mexico were often state funded and public. By contrast, lacking largescale state patronage, many British muralists painted for elite spaces like restaurants, hotels, and cocktail bars. While American muralism has been discussed in terms of labour, propaganda, and leftist politics, interwar British muralism has instead been understood in terms of recreation, entertainment, and luxury. In 1939, a review in The Times of the Tate exhibition Mural Painting in Great Britain – which featured Hastings’ frescos for the Marx Library and Buscot Park – concluded that “lighthearted” British muralism would “take the fear and mystery out of ‘mural’”.

Hastings’s Buscot Park frescos both confirm and complicate the narrative that British muralism was less

proletarian and propagandistic than its counterpart in North America. They subvert the conventions of country house decoration by expressing Faringdon’s leftist politics. At the same time, Hastings’ jokes, irony, and leisure scenes demand that we revise our expectations of social realism to make room for humour.

The frescos’ ambiguities suggest that Hastings could only partially adapt social realism to the walls of a country house – that the elite setting limited Hastings’ ability to make a political mural. However, this partial translation also reminds us that political art is not necessarily solemn, didactic, or uncontradictory. Hastings’ conflicting identities as a “red peer” allowed him to avoid taking too seriously either the leftist art world or the aristocracy, viewing both spheres with a simultaneously sympathetic and critical eye.

18

Page 12

Buscot Park, Oxfordshire. Photograph by Simon Q, 2011, Flickr.com (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Page 14

Viscount Jack Hastings (16th Earl of Huntingdon), Untitled Fresco Cycle (detail), circa 1937–39, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire. Courtesy of the Estate of the 16th Earl of Huntingdon and the Faringdon Collection at Buscot Park (all rights reserved).

Page 15

Viscount Jack Hastings (16th Earl of Huntingdon), Untitled Fresco Cycle (detail), circa 1937–39, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire. Photograph by Roger Vlitos. Courtesy of the Estate of the 16th Earl of Huntingdon and the Faringdon Collection at Buscot Park (all rights reserved).

Page 16

Viscount Jack Hastings (16th Earl of Huntingdon), The Worker of the Future Upsetting the Economic Chaos of the Present, 1936, fresco, Marx Memorial Library, London. Courtesy of the Estate of the 16th Earl of Huntingdon and the Faringdon Collection at Buscot Park (all rights reserved).

Photographs published in “English Society”, Life, 29 September 1947.

Page 19

Diego Rivera, Wall Street Banquet, 1923–28, fresco, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City. Photograph by Adam Jones, 2011, Flickr.com (CC BY 2.0).

Viscount Jack Hastings (16th Earl of Huntingdon), Untitled Fresco Cycle (detail), circa 1937–39, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire. Courtesy of the Estate of the 16th Earl of Huntingdon (all rights reserved).

19

Fuseli’s Nightmare

Last autumn, a series of public lectures at the PMC investigated key Georgian artworks and their context, impact, and often provocative content. Martin Myrone, who lectured as part of this series, looks anew at receptions and reinventions of The Nightmare (1781) by Henry Fuseli. Recordings of all the lectures in “Georgian Provocations Series II” can be watched on our website. Martin is Head of Grants, Fellowships, and Networks at the PMC and was previously a curator at Tate.

There are few works of art which enjoy a cultural life that extends far beyond the relatively rarefied world of art history. Think Mona Lisa, Last Supper, The Scream… these images are reproduced, imitated, lampooned, copied, and referenced so extensively and variously that it would be impossible to fully account for their cultural afterlives. They have, instead, entered the culture as icons – an overused word but one which properly captures how venerating and celebrating images can obscure their original meaning and history. Sometimes the reputations of these images have grown slowly over time, sometimes they have been rediscovered. Images which were once celebrated can also drop out of public view, their former fame now in need of explanation (look up, for instance, Joshua Reynolds’ cloying and bizarre Angel’s Heads).

In this limited canon of pictorial fame, there is a work of notable singularity: Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781). Singular because its

22

fame was instantaneous, and has been continuous since it was first exhibited, in London in 1782. It was also produced by an artist who adopted Britain as his home, and British art is not heavily represented in the international hall of the greatest artistic fame – and then with portraits and landscapes rather than the literary and supernatural subject matter we see with this painting. Singular, too, because critics at the time were decidedly uncertain about the merits of the work, and Fuseli and this picture have never quite been fully rehabilitated in terms of critical reputation.

So: what do we see in this painting? A young woman lies on her back in a bed, her arms thrown behind her, and her fair hair spread out, her body language restless. On her stomach squats a naked, darkskinned humanoid creature with pointy ears, who looks back at us with bulging eyes. Behind the bed, a ghostly horse’s head protrudes through a gap in heavy red curtains. A weird dark glitter pervades the scene, giving the squatting creature’s skin a certain reptilian quality, pinpricks of light catching our eye as they appear on a brooch on the woman’s chest, in the bottles on the table, and in the eyes of the horse.

The picture was an immediate sensation when it was exhibited in the Great Room of the Royal Academy of Arts during its annual public exhibition in Somerset House, London in 1782. There were various controversies that year and other works calculated to grab viewers’ attention, but none as controversial as, or with the lasting impact of, Fuseli’s The Nightmare.

Although from a well-established family of artists and art historians, Fuseli had begun training for the church before becoming embroiled in a local controversy and leaving Switzerland in search of creative and political freedom. Initially establishing himself as a translator in London in the 1760s, he turned to visual art and adopted a persona of extreme, eccentric creative genius. Fuseli’s selfpromotion secured him material support to travel to Rome where his fame grew. Back in London in 1779, he spent several years exhibiting literary and mythological works, which had garnered considerable public attention and some consternation.

The exhibition of The Nightmare in 1782 was a new departure for Fuseli: relatively small scale, the painting lacked definite literary or mythological source matter. Instead, it was a dazzling conundrum, combining an array of folkloric, classical, art-historical, and poetic allusions that no one then, or since, has been able to decode

23

satisfactorily. Viewers at the time speculated as to what the painting meant: was this something from a known literary source or just the sick outpouring of a deranged imagination? Art historians and critics have since the mid-twentieth century explored the picture more deeply, referring to interpretive keys from the artist’s sexual desires and experience of unrequited love, to the monstrous and phallic imagery contained with the painting – which makes it a gift to Freudian analysis – and fairy-tale traditions; and the possibility of scientific allusions (either in reference to then-current understandings of sleep paralysis, or the effects of narcotics, stimulants, and diet), as well as to sources in Shakespeare, folklore and antique texts, or images by Salvator Rosa, Guido Reni, and elsewhere within classical sculpture… the list goes on.

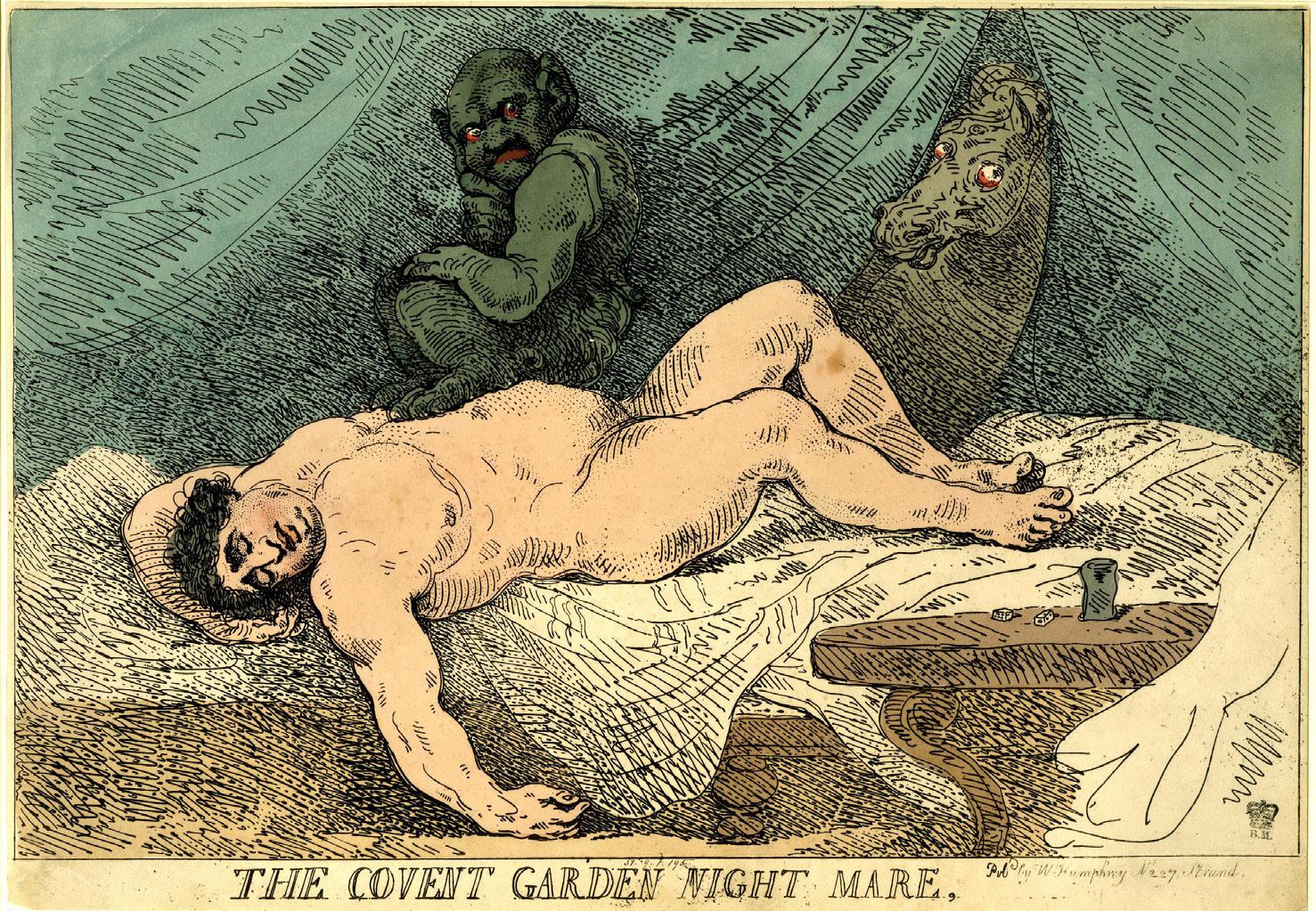

But above all, The Nightmare had immediate, visceral power as an image, loaded with metaphorical potential. The leading connoisseur Horace Walpole noted, simply, “Shocking” in the private comment scribbled in his copy of the exhibition catalogue. An official engraving was issued in 1783, but it was being lampooned by caricaturists as early as 1784, when Thomas Rowlandson cast the leading Whig politician Charles James Fox in the role of the oppressed woman. The Nightmare has never left the public imagination since. Intriguingly, the painting itself was rarely seen, being out of the public eye (and long outside of the UK) in a private collection before it was purchased by the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1955. As an image, it was instead mainly known by being caricatured, emulated, and copied.

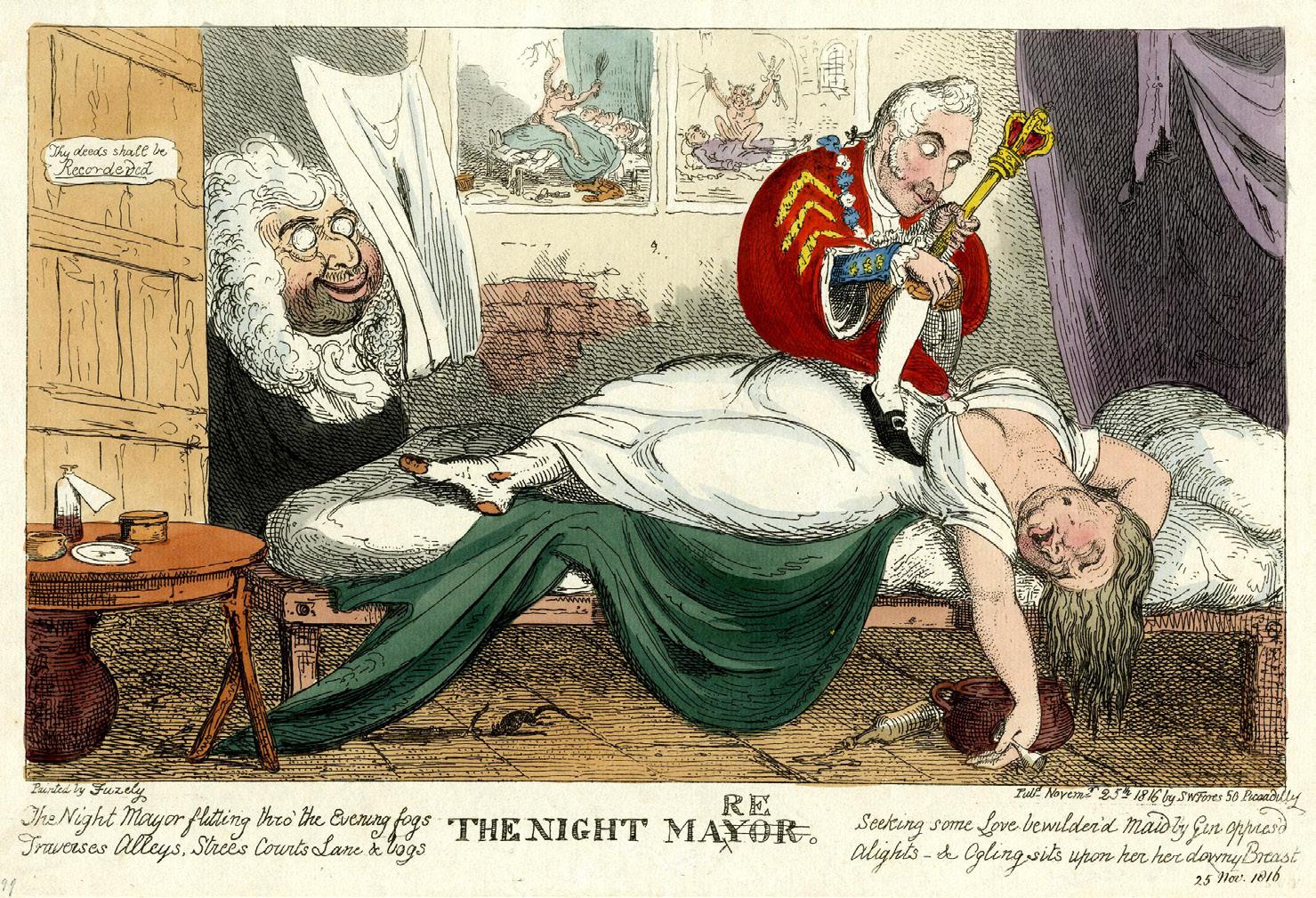

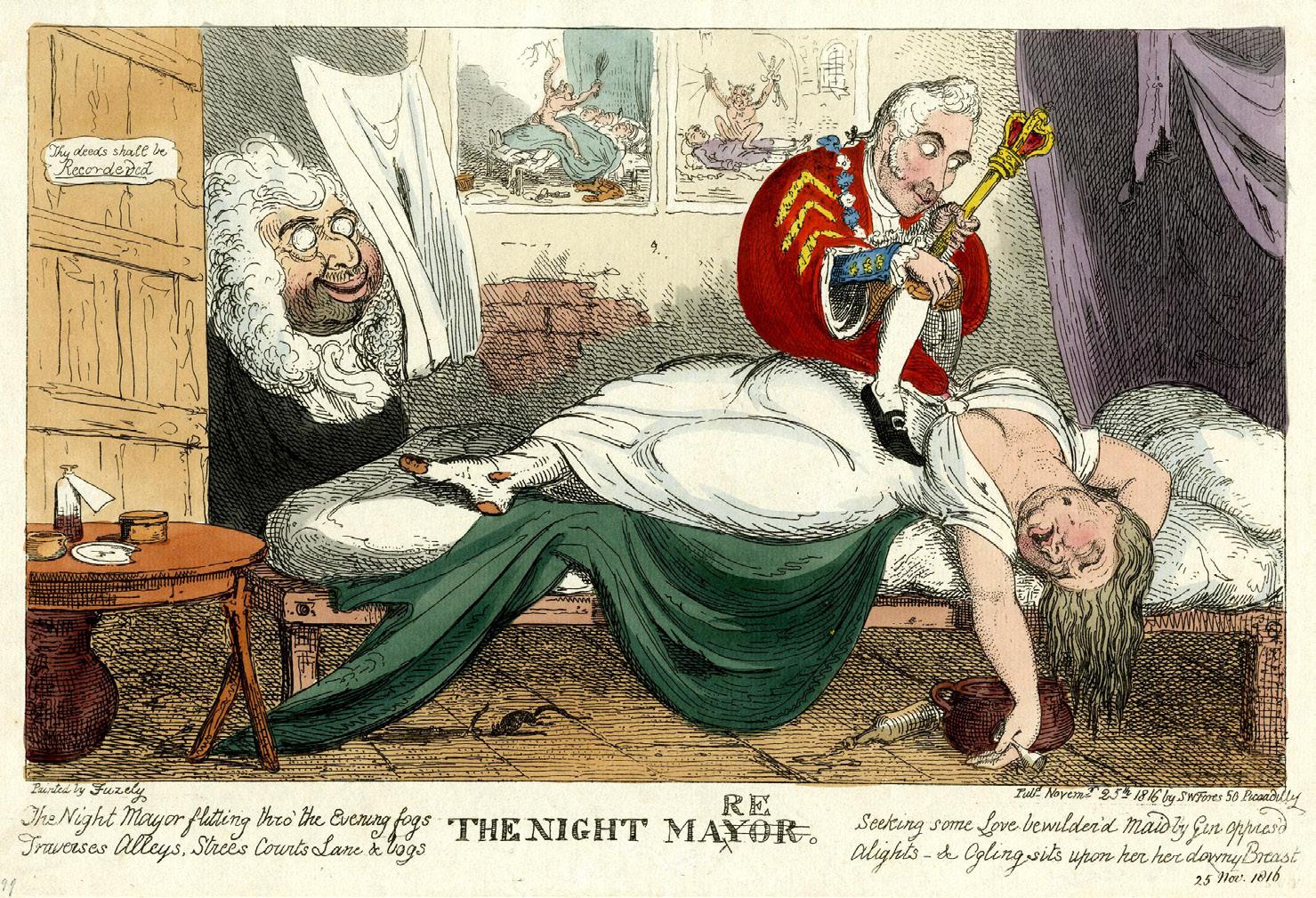

Its basic cast and composition have proved a favourite formula for satirists down to the present day, mobilised to comment on everything from art criticism to the economy. From the 1810s, we have George Cruikshank making a bad pun and having visual fun with his “Night Mayor” sitting on the stomach of a woman, while in our day Steve Bell cast Angela Merkel in the role of the woman herself, while former French president Nicolas Sarkozy sits on her and a googlyeyed Bismarck watches on. The art critic Brian Sewell was an admirer and collector of Fuseli and well aware of his reputation as an impish and sometimes outrageous writer, so knew what impact it would have when he was cast as the goblin on the striking cover of his collection of essays.

In the field of the moving image, Fuseli’s composition has been utilised numerous times, surely informing the visualisation of vampiric malevolence from Nosferatu (1922) through to “Hammer Horror” and

24

25

26

beyond, and serving as the model for a multitude of posters and DVD covers. There have also been cases where the image was mobilised in art-historically informed ways, as with Éric Rohmer’s The Marquise of O (1976), or most obviously Ken Russell’s Gothic (1986). The latter film centres on the night of storytelling in 1816 that led to Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, and features an oversized reproduction of the painting itself, hanging over a fireplace at Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva, and a nightmarish restaging of The Nightmare with Shelley, played by the late Natasha Richardson, oppressed by the imp, brought to life by the stunt performer and actor Kiran Shah. That restaging served, predictably, as the basis of the lead image in marketing and publicity for the film. Closer to our time, we can note that Alex van Warmerdam, the director of Borgman (2013), a psychological drama which evokes folklore around dreams and malevolent night-time invaders and which borrowed Fuseli’s composition visually, is also a painter.

The comical, ridiculous, or outrageous tone of much of the imagery which has kept The Nightmare in circulation means that it can be hard to take the image seriously now. Indeed, there may be an element of caricature in the original image; it is not clear how seriously Fuseli expected the image to be taken. Fuseli’s painting has been cheerfully reproduced as an emblem of weird fantasy and a metaphor of oppression. But that very cheerfulness should perhaps disturb us more than it does. What do we see in this painting? A dark-skinned monster molesting a young woman in her sleep. The racial and sexual politics set out by the picture are without doubt unpalatable, and the fact that such iconography has been so readily absorbed into and replicated by mainstream culture deserves, perhaps, some fresh attention.

27

Pages 20–21

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781, oil on canvas, 101.7 × 127.1 cm. Courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Bert L. Smokler and Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence A. Fleischman (55.5.A).

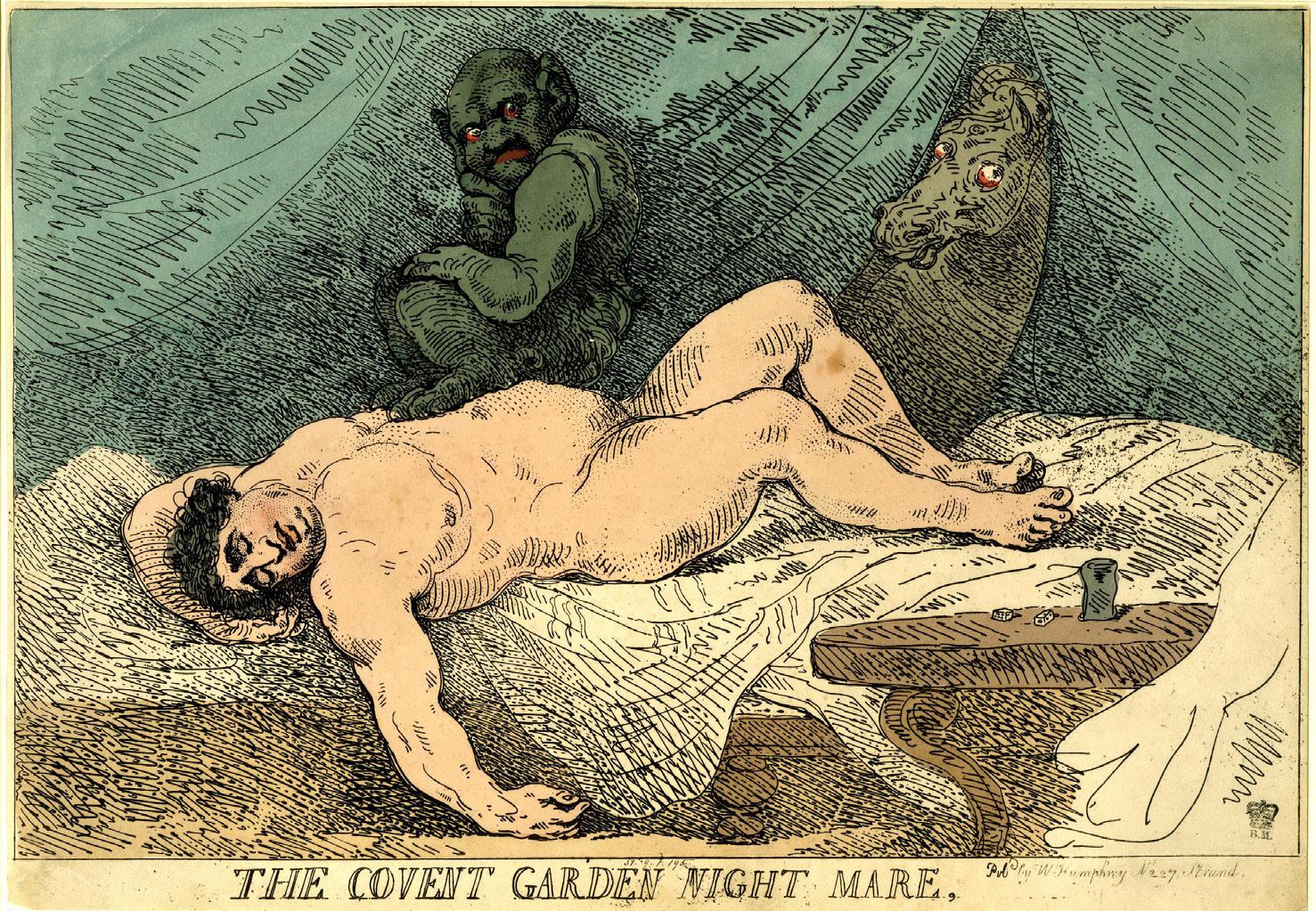

Page 25

Thomas Rowlandson, The Covent Garden Night Mare, 1784, etching, 23.9 × 33.5 cm. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum (1851,0901.195).

George Cruikshank, The Night Mare, 1816, 24.3 × 36.1 cm. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum (1868,0808.8351).

Page 26

Film still, Gothic, directed by Ken Russell, 1986. Courtesy of Cinematic Collection/Alamy Stock Photo.

Cover design of Brian Sewell, The Reviews that Caused the Rumpus and Other Pieces (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1994). Courtesy of Bloomsbury Publishing. Cover photograph by Andrea Heselton/Jacket design by Fielding Rowinski.

Film poster, Borgman, directed by Alex van Warmerdam, 2013. Courtesy of Graniet Film/Photo 12 /Alamy Stock Photo.

28

PMC

Director

Mark Hallett

Deputy Director

Sarah Victoria Turner

Executive Personal Assistant to the Director and Deputy Director

Victoria Walker

Chief Financial Officer Sarah Ruddick Finance Manager Donna Witter

Finance & Administration Officer

Barbara Ruddick Finance Officer Marianette Violeta Librarian

Emma Floyd Assistant Librarian Gaetano Ardito Archivist and Records & Data Protection Manager

Charlotte Brunskill Digital Preservation & Records Manager Pawel Jaskulski Assistant Archivist Morwenna Roche Archives & Library Assistant (Graduate Trainee)

Hannah Jones Senior Editor Baillie Card Senior Editor Emily Lees Assistant Editor Tom Powell

Picture Researcher Maisoon Rehani

Digital Lead Tom Scutt

Digital Marketing Manager Alice Read

Digital and Marketing Assistant (Graduate Trainee)

Shai Mitchell Operations Lead Suzannah Pearson

Operations Lead (Parental Leave Cover)

Guy Smith Operations Coordinator Stephanie Jorgensen Receptionist Karen Pilz Head of Research and Learning Sria Chatterjee Events Manager Ella Fleming Acting Learning Programme Manager Esme Boggis Events Assistant Danielle Convey Audio Visual Technician

Doug Palfreeman

Head of Grants, Fellowships, and Networks Martin Myrone Grants and Fellowships Manager

Harriet Sweet Grants and Fellowships Manager (Parental Leave Cover) Gareth Clayton Networks Manager Bryony Botwright-Rance Human Resources Manager Barbara Waugh Human Resources Officer Gabriella Rhodes Senior Research Fellow Hammad Nasar Senior Research Fellow Martin Postle

Advisory Council

Jo Applin Courtauld Institute of Art

Viccy Coltman Edinburgh College of Art

Tarnya Cooper National Trust

Elena Crippa Tate Britain

Caroline Dakers University of the Arts London

David Dibosa Chelsea College of Arts

John Goodall Country Life Julian Luxford University of St Andrews

Dorothy Price Courtauld Institute of Art

Christine Riding National Gallery Mark Sealy Autograph

Nicholas Tromans Independent Art Historian

Governors

Peter Salovey President, Yale University Scott Strobel Provost, Yale University Susan Gibbons Chief of Staff to the President, Vice Provost for Collections and Scholarly Communication, Yale University

Stephen Murphy Vice President for Finance and Chief Financial Officer, Yale University

Template Design

Strick&Williams

Editing and Layout

Baillie Card and Harriet Sweet Printed by Blackmore

Fonts

Saol Text and Galaxie Polaris Paper Fedrigoni Arena Natural Smooth

Contact us

Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA United Kingdom T: 020 7580 0311 www.paul-melloncentre.ac.uk

Staff

CBP003494