Conservation Management Plan, 2024 - Phase 1: Assessment of biodiversity value and threats

Conservation Management Plan, 2024

edited by Paul J J Bates

Recommended citation: Dendup, T., M. Suarez-Rubio, S. Renner, B. Lanzinger, T. Yangzom, M. Zangmo, and P. Bates (2024). DeothangNarphang-Samdrup Jongkhar IBA: Conservation Management Plan, 2024, Phase 1: Assessment of biodiversity value and threats. Unpublished Report.

Acknowledgements: We thank the Ministry of Education for their kind permission and support. We are indebted to former Principal Tashi Tenzin and Acting Principal Tenzin Wangchuk, and all the staff of Phuntshothang Middle Secondary School for their encouragement and participation. We thank RSPN (Royal Society for the Protection of Nature), NBC (National Biodiversity Centre), and BBS (Bhutan’s Birdlife Society) for their advice and assistance. None of this would have been possible with the active participation of the ever-enthusiastic and exceptionally talented school children. Finally, we thank CLP (Conservation Leadership Programme) for their financial support, training and guidance. They provided inspiration and enthused us to aim high and play our part in conserving Bhutan’s richly diverse, beautiful biodiversity.

This action plan is an output from the CLP (Conservation Leadership Programme) project ‘Schools-based,science-basedparticipatoryapproachto conservationinBhutan’,which was led by Tshering Dendup MSc and Ms Tshering Yangzom of the Nature Club, Phuntshothang Middle Secondary School, with support from fellow staff members. It was assisted by colleagues in the Department of Forests and Park Services.

In addition, four international organisations provided technical training, further financial assistance, and extra equipment, namely: the Harrison Institute (UK), the Natural History Museum Vienna, the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (Austria), and the Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

All photos and maps copyright of CLP-Deothang (unless otherwise stated) namely: Tshering Dendup Paul Bates, Pipat Soisook and Marcela Suarez-Rubio.

Tshering Dendup MSc is a science teacher at Phuntshothang MS School. As a bat ecologist and head of the school’s Nature Club, he led the CLP sponsored project, throughout its 16month field programme. Responsible for all aspects of the project, he helped raise substantial additional sponsorship, liaised with in-country NGOs, and included an international scientific component.

Tshering Yangzom BSc is a teacher at Phuntshothang MS School. She has a degree in science and a commitment to developing new approaches to teaching and equal opportunity for girls. In the Nature Club, she particularly works with younger pupils. With expertise in field study techniques, she joined both the bird and bat survey teams.

Maylem Zangmo is a Forest Ranger for the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. Based in Phuntshothang, she graduated with a national certificate in nature study and forest management. For the project, she actively participated in the bird surveys, assisting the school pupils, and in the remote sensing training.

Paul Bates PhD is the Director of the Harrison Institute, UK. Trained as a mammal taxonomist, today he leads the Institute’s programme of enabling and empowering the next generation of scientists and conservationists in the tropics. As well as participating in the field work, he assisted Tshering Dendup in promoting the project to the international scientific community.

Marcela Suarez-Rubio PhD is a landscape ecologist and senior researcher at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) Vienna. For the project, she led the training programme in remote sensing and GIS, as well as assisting the training of school pupils in field study techniques for bird surveys. Swen Renner PhD is Curator of Ornithology at the Natural History Museum Vienna and an expert on the Himalayan bird fauna. For the project, he led the training programme in the theoretical and practical aspects of bird surveys. This included training staff and pupils in bird netting techniques, bird identification, and the taking of blood samples to determine the presence of avian malaria.

Beatrix Lanzinger is Project Manager at the Harrison Institute. With a background in community-based projects, she worked extensively with Tshering Yangzom and the younger pupils of the Nature Club in developing new approaches to learning about wildlife and the importance of environmental protection. She also participated in the bird field work.

Pipat Soisook PhD is is an award-winning curator of mammals at the Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Natural History Museum, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand. An international expert on Asian bats, he worked with Tshering Dendup, his former student, and the school pupils to help develop a comprehensive survey of forest bats within Deothang-IBA.

The project would not have been possible without the active participation of so many pupils and staff from Phuntshothang MS School.

Contents Pages

2 ……………………….. Section 1 – Deothang-Narphang-Samdrup Jongkhar IBA – summary of key biodiversity features

3 ……………………….. Section 2 – Background Information

5 ……………………….. Bhutan – Topography, climate, population

6 ........................... Bhutan – Biodiversity summary

6 ……………………….. What is an IBA?

7 ……………………….. Bhutan’s IBAs

8 ……………………….. Purpose of the Conservation Management Plan for Deothang-NSJ IBA

9 ……………………….. Background to developing the Conservation Management Plan for Deothang-NSJ IBA

9 ……………………….. Section 3 – Deothang-Narphang-Samdrup Jongkhar IBA

10 ……………………… Geographical location

10 ……………………… Conservation status

11 ……………………… Ecology

11 ……………………… IBA criteria and trigger species

13 ……………………… Biological attributes

13 ……………………… Bird fauna

15 ……………………… Status of trigger species

16 ……………………… Status of potential additional trigger species

16 ……………………… Status of all bird species in Deothang-NSJ IBA

16 ……………………… Status of other fauna

19 ……………………… Mammals

19 ……………………… Bat fauna

19 ……………………… Plants

20 ……………………… Section 4 – Threats to Deothang-Narphang-Samdrup Jongkhar IBA

20 ……………………… Climate change

21 ……………………… Air pollution

21 ……………………... Forest degradation

22 ……………………… Urban development

28 ………………….…… Road building

30 ………………………. Fire

31 ………………………. Mining

31 ………………………. Hunting and Human-Wildlife conflict

20 ……………………… Section 5 – Role of citizen science

20 ……………………… Section 6 – References

Deothang-NSJ IBA is both an ‘Important Bird Area’ (IBA) and a ‘Key Biodiversity Area’ (KBA). It is partly situated in Bhutan’s Biological Corridor 5, which is within the ‘Eastern Himalayan Endemic Bird Area’ and the ‘Himalayan hotspot’ for biodiversity.

It has an area of 39,174 ha and an elevation range of 150-2400+ masl. At lower elevation, it is part of the Himalayan Subtropical Broadleaf Forest Ecoregion, which has a conservation status of ‘Endangered’ and a biological distinctiveness of ‘Regionally outstanding’. In areas that exceed 2000 masl, it is part of the Eastern Himalayan Broadleaf Forests Ecoregion and is ‘Globally outstanding’ for species richness.

The bird fauna recorded from the IBA is diverse, abundant for many species, and comprises:

• 447 species (ebird), including:

• one Endangered species (EN): Pallas’s Fish Eagle

• six Vulnerable species (VU): Steppe Eagle, Great Hornbill, Rufous-necked Hornbill, Wreathed Hornbill, Dark-rumped Swift, Beautiful Nuthatch, Grey-crowned Prinia

• 15 Near-threatened species (NT): Chestnut-breasted Partridge, Ashy-headed Green Pigeon, Green Imperial Pigeon, River Lapwing, Lesser Adjutant, Himalayan Griffin, Mountain Hawk-Eagle, Rufous-bellied Eagle, Ward’s Trogon, Blyth’s Kingfisher, Black-headed Dwarf Kingfisher, Yellow-rumped Honeyguide, Alexandrine Parakeet, Large-billed Leaf Warbler and Rufousthroated Wren Babbler.

• 425 species of Least Concern (LC).

There are globally significant populations of three ‘Vulnerable’ species of hornbill: Great Hornbill, Rufous-necked Hornbill, and Wreathed Hornbill. Two other ‘Vulnerable’ species, Beautiful Nuthatch and Dark-rumped Swift are present but rare.

In general, with the exception of birds, the fauna is little known. However, mammals of conservation importance include Asian Elephant (EN) and Black Giant Squirrel (NT). At least 17 species of bat, are known from the IBA. Other fauna includes King Cobra (VU) and Bengal Monitor Lizard (NT). The IBA also supports rare, endangered and critically endangered flowering plants.

At present, the level of threats to wildlife appear low, especially when compared to elsewhere in the Himalayas. However, they do include to varying extent:

• Climate change – risks unknown but probably include changes in species range

• Atmospheric air pollution – exact risks unknown but probably increasing

• Forest degradation – currently relatively low

• Urban development – currently low but increasing

• Road building – currently low but increasing

• Mining – risks present but not quantified

• Fire – currently low.

Bhutan is situated on the southern slopes of the Eastern Himalayas. It has a land area of 38,394 km 2 . The topography is characterised by high mountain ranges and north-south V-shaped valleys, formed by fast flowing rivers and streams. Elevation rises from south to north, through the Southern Foothills, to the Lesser Himalaya, and finally the Higher Himalaya.

Minimum elevation is 97 masl and maximum elevation 7570 masl (Tshewang et al., 2021). Some 20% of the land is above 4200 masl and is covered by perpetual snow and ice. The elevational range of 7,473 m is the fifth largest for any country globally and the largest per unit area (further information).

As a result of its complex topography, Bhutan’s climate is highly diverse, with extreme variation in temperature and precipitation between different areas. The country experiences four seasons: Spring (March to June) with increasing heat and humidity;

Summer Monsoon (July to September), the southeast monsoon brings rain, especially to the south of the country; Autumn (end of September to November), the weather stabilises, and skies start to clear; and Winter (December to February), temperatures fall, especially at higher elevations (Gogoi, 2024).

Bhutan’s population is approximately 790,000. This has more than doubled in the last 50 years, although the growth trend is now greatly reduced (further information). The median age is 29.4 years.

Population density (21 per km2) is low, especially in the rural areas. Land-use trends show a substantial reduction in area under cultivation from 314,600 ha in 1995 to 105,684 ha in 2016. Meanwhile, there is an increase in urbanisation, although with an area of just 7,457 ha in 2016, this represents only 0.19% of the total land area (Tshewang et al., 2021). Nearly half the population (48.5%) is urban (further information).

Bhutan is considered a global hotspot for biodiversity.

It retains large areas of pristine Himalayan forests and alpine habitats. The forests on the lower slopes of the Bhutan Himalayas are particularly important, as low altitude forests have been cleared extensively in Nepal and in north-east India (Birdlife, 2024b).

Provisional figures suggest that within Bhutan there are over 5600 species of flowering plant, 200 species of mammal, and between 800 and 900 species of butterfly (CBD Profile).

The number of bird species varies according to the source. Birdlife (2024c) includes 620 species; Spierenburg (2005) lists 645; the CBD profile has 678,

ebird has 729; and Avibase Bird Checklist includes the highest figure of 761 species.

Currently, forest covers over 70% of the Bhutan’s land area. Of this, the vast majority is broadleaf forest, with smaller proportions of mixed conifer, fir, chir pine, and blue pine forest (Tshewang et al., 2021).

The country has an enviable national policy to maintain environmental stability, which includes at least 60% of the country forested. It has five national parks, four wildlife sanctuaries, one strict nature reserve. Together, these nine protected areas cover 35% of the total land area (WWF, 2016). It also has a number of biological corridors linking the protected areas (Fig.6).

In addition to protected areas and biological corridors, Bhutan has 23 IBAs (Important Bird Areas) of which eight fall within protected areas and 15 are unprotected (BirdLife (2024b).

They are distributed throughout Bhutan, cover some 26% of the country’s land area, and vary considerably in size.

Nine IBAs are 5,000 ha or less, with the smallest being Kanglung Wetlands with an area of 1,000 ha. Nine IBAs are 50,000 ha or more, with the largest two being Jigme Singye Wangchuk National Park and Jigme Dorji

IBA is the acronym for ‘Important Bird Area’, also known as ‘Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas’ (Waliczky et al., 2019).

Currently, there are over 13,000 IBAs globally. Of these, 2293 are in Asia, distributed within 28 countries. Together, they cover a total area of 2,331,560 km2, which is 7.6% of the region’s land area (Chan et al., 2004).

IBAs have been developed to promote the conservation of birds and other biodiversity and to help guide sustainable development. They are distinct areas, which are defined using objective, internationally recognised criteria.

According to BirdLife (2024a), each IBA must fulfil one or more of the following four criteria, A1 to A4 (see below).

IBAs vary in size from a few hectares to thousands of hectares. Sometimes, they include land that is protected (for example in a National Park). Often, much or all the land is unprotected with a variety of ownerships, both

public and private. IBA boundaries help identify areas that deserve prioritisation for conservation actions, and they can act as a spatial guide for planning purposes. They should be considered approximates, rather than absolute boundaries of critical habitats (Audubon, 2024).

The designation of a site as an IBA does not provide legal or regulatory status. Rather, the participation in its conservation is entirely voluntary on the part of the local landowners (Audubon, 2024).

In many cases, outside the conservation community, most local people, including those involved in day-to-day planning issues, are not aware that they live within an IBA. In almost all cases, there is no on-the-ground signage and often little public knowledge of the location or the meaning of an IBA. This requires a process of raising awareness and building consensus for conservation action through engaging with local, as well as national, stakeholders.

National Park, with 130,000 ha and 390,000 ha, respectively (BirdLife (2024b).

In 16 IBAs, forest is the main habitat. Six IBAs are in high altitude valleys. One (IBA 18) supports the only major wintering population of Black-necked crane outside China.

All 23 IBAs support globally threatened species (Criterion A1). Twelve have restricted-range species (Criterion A2), 15 have biome-restricted species (Criterion A3), and four hold more than 1% of regional populations of waterbird species (Criterion A4) (BirdLife (2024b).

A1. Globally threatened species: The site is known or thought regularly to hold significant numbers of a globally threatened species (categorized by the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable). Specific thresholds are set for species within each of the threat categories that need to be exceeded at a particular IBA. The list of globally threatened species is maintained and updated annually for IUCN by BirdLife International.

A2. Restricted-range species: The site is known or thought to hold a significant population of at least two rangerestricted species.

Restricted-range bird species are those having a global range size less than or equal to 50,000 km2. ‘It is recommended that site-level populations of at least two restricted-range species should be equal to or exceed 1% of their global population.

A3. Biome-restricted species: The site is known or thought to hold a significant component of the group of species whose distributions are largely or wholly confined to one biome-realm. Bioregion-restricted assemblages are groups of species with largely shared distributions which occur (breed) mostly or entirely within all or part of a particular bioregion. Many biome-realms cross political boundaries; where this is so, national networks of sites are selected to ensure that all relevant species in each country are adequately represented in IBAs.

A4. Congregations: The site is known or thought to hold congregations of ≥1% of the global population of one or more species on a regular or predictable basis.

Sites can qualify whether thresholds are exceeded simultaneously or cumulatively, within a limited period. In this way, the criterion covers situations where a rapid turnover of birds takes place (including, for example, for migratory land birds).

The purpose of this Management Plan is to promote biodiversity conservation and environmental protection in Deothang-NSJ IBA.

It has three principal objectives:

• provide a starting point for stakeholders to understand in more detail the biological value of Deothang-NSJ IBA

• provide a baseline against which future conservation actions can be measured

• advocate for local and national stakeholders to develop a strategy and implement day-to-day actions that will enhance and promote biodiversity conservation and sustainable development within the IBA.

Within the context of limited time and finite resources, this first-phase Conservation Management Plan has followed Stages 1-5 of an eight-stage conservation process (see blue box).

This process is ongoing and the level of detail within the plan can be continuously enhanced, and the recommendations revised and improved.

Conservation actions, once implemented, can also be evaluated for relevance and effectiveness.

• Stage 1: Researching background data about the IBA.

• Stage 2: Ground-truthing information from desk-based studies through fieldwork.

• Stage 3: Determining priority species, areas, and habitats, based on background studies and field research.

• Stage 4: Defining conservation targets and developing recommendations.

• Stage 5: Producing a draft/initial Conservation Management Plan to assist with extensive consultation.

• Stage 6: Raising awareness and building consensus for conservation action through engaging with local and national stakeholders.

• Stage 7: Implementing action in the field that meets the aim of ensuring long-term environmental protection of the IBA, which is compatible with sustainable development and enjoys local and national support.

• Stage 8: Implementing adaptive management through combined behaviour change and impact evaluation to ensure objectives and actions continue to meet the above aim and objectives.

*: a revised version of wbcsd’s guidelines

Geographical location

Deothang-NSJ IBA is situated in south-eastern Bhutan (IBA 21 in Fig. 8), centred on 26.90°N, 91.52°E. It has an area of 50,000 ha* and extends approximately 28 km north to south and has a maximum east-west width of 25 km. The altitude ranges from 150 masl on the Indian border to over 2400 masl in the north (Birdlife (2024d).

Essentially triangular in shape, the IBA is mostly included in the western part of Samdrup Jongkhar District, with

*The area of the KBA is given as 39,174 ha, which appears to be a more accurate figure for the IBA. According to the KBA citation, 30% of the area is protected. However, this would appear to refer to that part of the IBA/KBA that lies within the Biological Corridor 5, which itself receives no formal protection.

only its most northerly part in a small area of south-west Trashigang and eastern Pemagatshel Districts, respectively.

Its southern border is the international boundary between Bhutan and India. The villages of Raysinang and Zobel are approximately its most northerly extension. Its western border lies some 2-3 km west of the main road (PNH3) which runs north from the border town of Samdrup Jongkhar towards Trashigang. Much of its eastern border is delineated by the Puthimari River.

Conservation Status:

Deothang-NSJ IBA is not formally protected. In addition to being an IBA, it is also recognised as:

• a KBA (Key Biodiversity Area) (KBA, 2024).

It is located within:

• the ‘Himalaya hotspot’, which is one of the Earth’s key biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities identified by Myers et al. (2000)

• two Indo-Pacific Terrestrial Ecoregions that have been assessed as ‘Regionally Outstanding’ and ‘Globally Outstanding’, respectively for biological distinctiveness (Wikramanayake et al., 2002)

• two Global 200 ecoregions (Olson and Dinerstein 1998), namely at lower altitudes, the ‘Brahmaputra Valley Semi-evergreen Forests Ecoregion’ and at higher elevations, the ‘Himalayan Subtropical Broadleaf Forests’

• the Eastern Himalayas Endemic Bird Area, with a conservation priority of ‘urgent’ and the highest score for biological importance; it borders the Assam Plains Endemic Bird Area (Stattersfield et al. 1998)

• Bhutan’s Biological Corridor 5, which links Jomotsangkha Wildlife Sanctuary to Royal Manas National Park (Wildlife Conservation Division, 2010).

According to Birdlife (2024d), the area was identified as an IBA in 2004 because “it was regularly supporting significant populations of the following bird species.”

• Chestnut-breasted Partridge Arborophila mandellii NT

• Dark-rumped Swift Apus acuticauda VU

• Rufous-necked Hornbill Aceros nipalensis VU

• Grey-crowned Prinia Prinia cinereocapilla VU

• Beautiful Nuthatch Sitta formosa VU.

Plants

It is also considered important for some plant species (Appendix 2, page 83 in CEPF, 2005), although no details are given (but see below).

Ecology:

With an elevational range of 150 to 2400+ masl, Deothang-NSJ IBA’s natural vegetation comprises montane broadleaf evergreen forest (montane temperate), semievergreen rain forest (tropical), and hill evergreen forest (subtropical) (Birdlife (2024d).

At lower elevations, it is part of the Himalayan Subtropical Broadleaf Forest Ecoregion, which, according to Wikramanayake et al. (2002), has a conservation status of ‘Endangered’ and a biological distinctiveness of ‘Regionally Outstanding’.

In areas that exceed 2000 masl, it is part of the Eastern Himalayan Broadleaf Forests Ecoregion and is ‘Globally outstanding’ for species richness.

These two ecoregions comprise an east-west band of forests that run along the Outer Himalayan Range, from eastern India, through Bhutan and Nepal to western India. They are characterised by high rainfall.

According to Rawat and Mukherjee (1999), the forests in these ecoregions are known to have rich biodiversity and the forest types are varied because of the subtropical climate, complex topography, rich alluvial soils, moisture gradient, and intermingling of taxa from the Indo-Malayan and Palaearctic regions.

Forests generally reach at least 30 m in height. The top canopy is less dense than the tropical evergreen forests, and a mid-canopy and shrubby undergrowth is recognisable (Wikramanayake et al., 2002).

These forests form a critical link in the interconnected Himalayan ecosystems that extend from the Terai and Duar grasslands along the foothills to the high alpine meadows.

Historically, they have been heavily degraded such that outside Bhutan, the majority (70%) of these natural forests had already cleared by the end of last century (Wikramanayake et al., 2002).

Summary

There are no dedicated scientific publication on the bird fauna of Deothang-NSJ IBA. Pittie (2009) summarized historical publications of Bhutan’s birds. Of these, Bishop (1999) includes some sightings from within the IBA area.

On the basis of maps included in Spierenburg (2005), there are 353 bird species present in the IBA (Appendix 1). However, this is an approximation as the maps are small and therefore the exact location of each distribution dot is not known.

Avibase does not provide data for the IBA but lists 612 bird species for Samdrup Jongkhar District. However, the IBA forms only the western part of this district, and also includes small parts of Trashigang and Pemagatshel Districts. More precisely, GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information System) lists 492 bird species for a polygon that replicates the shape of the IBA. GBIF datasets are

based on a combination of sources, including specimens from natural history museums, observations from citizen science networks, and environmental recording.

Meanwhile, ebird lists 447 bird species from Deothang-NSJ IBA. This results from 578 checklists (ebird, 2024a). ebird is a global checklist of over 100 million bird sightings annually (ebird, 2024b). The recent CLP project recorded 133 species, including 32 species collected in a 12 day netting programme. Details are included in Appendix 1

Collection points:

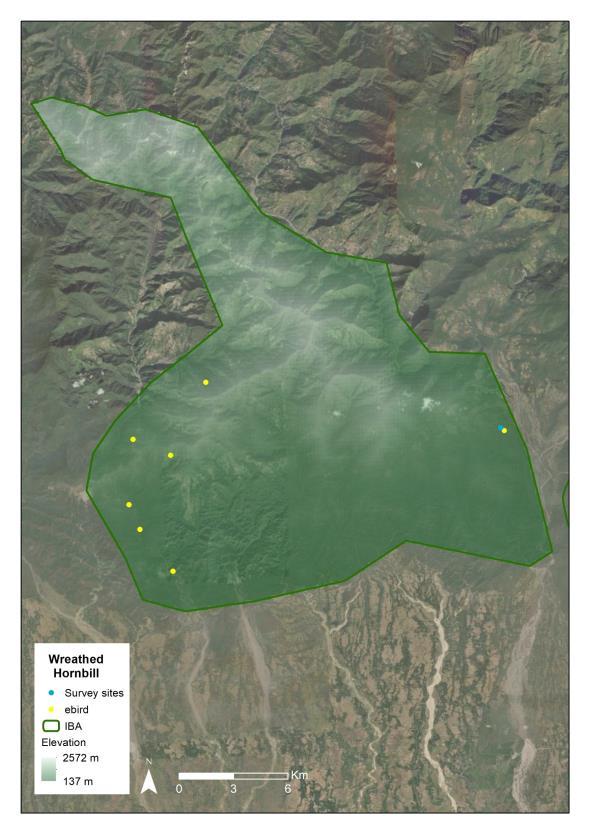

A map of the combined data collection points for ebird (November 2019 to December 2023) and the recent CLP study shows a coverage that follows two principal highways, and one smaller road (Fig. 16), namely:

• the primary national highway (PNH3) which runs from Trashigang (extralimital) to Samdrup Jongkhar via Menlong Brak, Narphung, and Deothang

• (the newly renovated secondary national highway (SNH11) which runs east from Deothang to Phuntshothang

• the small road that runs west of the Samdrup Jongkhar/Pemagatshel District border towards Zobel and Barseri.

This reflects the impenetrable nature of most of the district with its numerous peaks and valleys.

Timescale:

The 447 bird species included in ebird (2024a) are the result of almost 28 years of bird checklists.

In 2023, 238 species were reported (53% of the total known bird fauna for the IBA); 323 species (72%) have been reported since January 2020 and 441 species (99%) since March 2010. For five species the most recent records are 2006-2008 and one species, the Osprey, was last seen in 1996.

Of the 133 reports (excluding duplicates filed by different members of the same bird recording teams) on ebird (2024a), 75 were made in the Spring (March to June) and 51 in winter (December to February), only 5 were made in autumn (October to November) and only 2 during the summer monsoon season (July to September).

With only 5% of records from the monsoon and autumn period, this is a clear seasonal bias, which principally reflects the difficulty of travelling in the rains.

For the CLP study, netting for birds took place in March and July. Informal bird recording with binoculars took place throughout the year. Formal spot counts at 36 sites were undertaken in June, August, September, October, and November.

Five bird species are included as trigger species for the IBA (Birdlife (2024d), namely:

Chestnut-breasted Partridge (NT) is included by GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) and ebird from the area. It was not recorded during the recent CLP survey. In ebird, the last known record of this species from Deothang-NSJ IBA was from:

• near Tashi Gasel Lodge (26.811442°N, 91.498099°E) (heard but not seen) on 26 April 2018, (further information) (Fig. 19A).

The very infrequent records suggest it is either rare or difficult to observe or both.

Dark-rumped Swift (VU) is included by GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) and ebird from the area, where it is known from both the north and south of the IBA (Fig. 19A). It was not recorded during the recent CLP survey. In ebird, the most recent records are:

• 7 individuals seen near Tashi Gasel Lodge (26.811442°N, 91.498099°E) on 1 August 2023 (further information)

• 6 individuals seen to the east of Tashi Gasel Lodge (26.828183°N, 91.544619°E) on 12 May 2023 (further information)

• 4 individuals seen at Malongbra in the north of the IBA (27.019654°N, 91.508367°E) on 24 March 2021 (further information).

Rufous-necked Hornbill (VU) is included by GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) and ebird from the area. It was also recorded during the recent CLP survey. In ebird, it is

• one of the most reported species from the IBA with 14 sightings, including 9 in 2023

• widely distributed within the IBA, from north to south and east to west (Fig. 19B)

• seen in all four seasons, with records from February, March, April, August, and November

• most often recorded as single individual (35% of records) or as two individuals/pair (43%); in one report there were four individuals and in two reports the exact number of individuals was not given

• sometimes reported together with other hornbill species (5 out of 14 reports) (although this does not mean they are associating), including Oriental Pied-hornbill, Great Hornbill and Wreathed Hornbill.

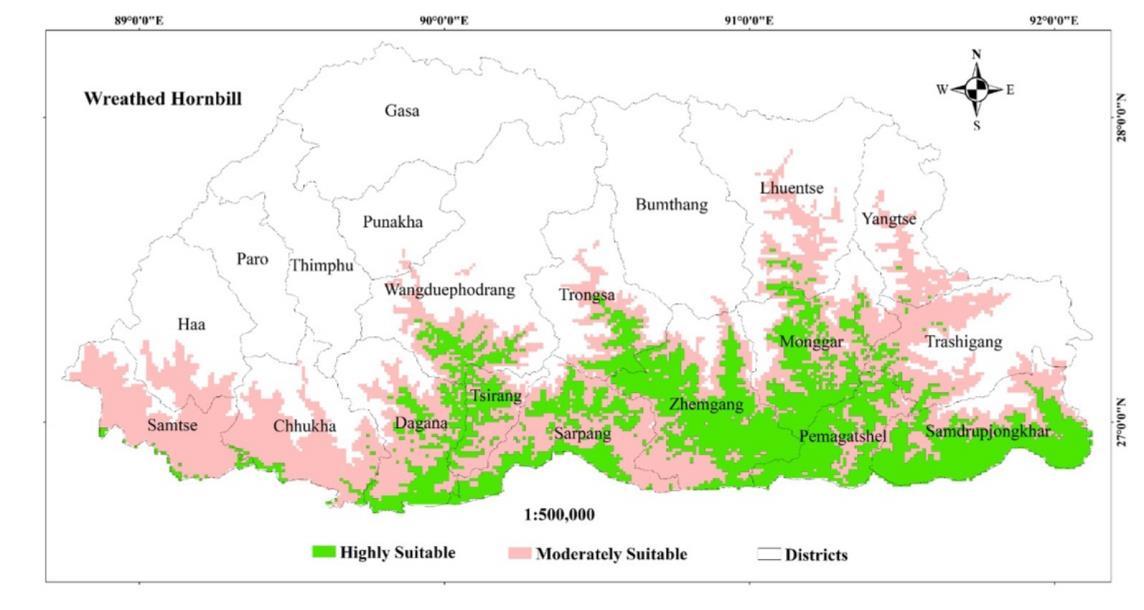

The habitat suitability map for the species included in NCD (2023) confirms that Deothang-NSJ IBA is a prime area for supporting populations of this species (Fig. 17). However, climate change is considered to be a major threat to the long-term survival of this taxon within Bhutan and elsewhere in the Himalayas (Dahal et al., 2023; NCD, 2023).

Grey-crowned Prinia (VU) is included by Avibase for Samdrup Jongkhar District. However, it was not seen during the CLP survey and is not included for the IBA in GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) or ebird. This species is no doubt difficult to observe and identify but on current evidence it would appear to be either extremely rare or not present within Deothang-NSJ IBA.

Beautiful Nuthatch VU is included by GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) and ebird from the area. It was not recorded during the CLP survey. In ebird, the most recent records are:

• one individual seen in ‘Morong’ (26.913440°N, 91.543470°E) on 23 April 2023 (further information)

• one individual seen in ‘Morong’ (26.930829°N, 91.546016°E) on 24 March 2021 (further information)

• two individuals seen in ‘Morong’ (26.879976°N, 91.498710°E) on 15 February 2020 (further information).

Spierenburg (2005) provides valuable information about the ecology of this nuthatch in Bhutan. He suggests that it occupies a narrow altitudinal zone from 1,200 to 2,000 m, although it may be found at lower elevation in winter. He notes that it is found in Narphung area, within the Deothang-NSJ IBA. It depends on tall, mature trees with abundant epiphytes, making it vulnerable to logging of old-growth warm broadleaf forests (Spierenburg, 2005).

Bishop (1999) observed this species north of Deothang, at 1,400 msal, and provides interesting notes on its foraging behaviour. Meanwhile, all three recent ebird sightings are attributed to Morong Valley. However, of the three

co-ordinates provided only one is near to Morong (Fig. 19A). This suggests that either the co-ordinates are inaccurate or the Beautiful Nuthatch was observed in Morong and also to the north and south of the valley.

Of the 447 bird species included in ebird (2024a) from Deothang-NSJ IBA, 23 species are listed as conservation dependent (NT to EN) (see also Appendix 1), namely:

• EN: Pallas’s Fish Eagle

• VU: Steppe Eagle, Great Hornbill, Rufous-necked Hornbill, Wreathed Hornbill, Dark-rumped Swift, Beautiful nuthatch, Grey-crowned Prinia

• NT: Chestnut-breasted Partridge, Ashy-headed Green Pigeon, Green Imperial Pigeon, River Lapwing, Lesser Adjutant, Himalayan Griffin, Mountain Hawk-Eagle, Rufous-bellied Eagle, Ward’s Trogon, Blyth’s Kingfisher, Black-headed Dwarf Kingfisher, Yellow-rumped Honeyguide, Alexandrine Parakeet, Large-billed Leaf Warbler and Rufous-throated Wren Babbler.

Of these 23 species, five are already included as trigger species for the IBA (see section above and here marked in italics). However, at least two others might also be considered as relevant. The Great Hornbill and Wreathed Hornbill are two globally Vulnerable species (VU). As with the Rufous-necked Hornbill, they are widespread within Deothang-NSJ IBA (Figs 19C and 19D, respectively).

Their inclusion would reinforce the status of the IBA under Criteria A1 – an area “known or thought regularly to hold significant numbers of a globally threatened species categorized by the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable”).

Great Hornbill (VU) is included by GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) and ebird from the area. In ebird (2024a), it is

• one of the most reported species from the IBA with 12 sightings, including 5 in 2023

• widely distributed, seemingly at lower elevations (Fig. 19C)

• seen in January, February, March, April, November, and December

• most often recorded as single individual (42% of records) or as two individuals/pair (42%); in two reports there were 9 individuals and in one report the exact number of individuals was not given.

As part of the CLP project, it was found to be common in and around Phuntshothang and its environs, with frequent sightings.

The habitat suitability map for the species included in NCD (2023) confirms that Deothang-NSJ IBA is a prime area for supporting populations of this species (Fig. 20 above).

Wreathed Hornbill (VU) is included by GBIF, Spierenburg (2005) and ebird from the area. It was also seen during the recent CLP survey. In ebird (2024a), it is

• less frequently recorded from the IBA than the Great Hornbill or Rufous-necked Hornbill but there were 8 sightings, including 4 in 2023

• widely distributed at lower altitudes (Fig. 19D)

• seen in all four seasons, with records from February, March, April, August, and November

• most often recorded as single individual (50% of records) or as two individuals/pair (38%); in one report there were 4 individuals

• as part of the CLP project, it was seen from the roadside from Phuntshothang to Deothang; it was less frequently sighted/heard than the Great Hornbill or the Rufous-necked Hornbill

The habitat suitability map for the species included in NCD (2023) confirms that Deothang-NSJ IBA is a prime area for supporting populations of this species (Fig. 20 below).

Potentially three other species, Ward’s Trogon, Yellowrumped Honeyguide, and Rufous-throated Wren-Babbler could also be included as trigger species under Criteria A2, restricted range species. However, of these only Ward’s Trogon has been seen recently (31 December 2023) (further details), whilst the Yellow-rumped Honeyguide was last seen in the IBA on 8 May 2019 (further details), and the Rufous-throated Wren-Babbler on 18 May 2018 (further details).

In view of the small size of the IBA (392 km2), a bird fauna of 447 species (ebird, 2024a) is extraordinarily rich.

It is one third of the total for India (1367 species), which has a land area 8,385 times larger (3,287,263 km2) than Deothang-NSJ IBA.

Deothang-NSJ IBA has an impressive number of records of raptor and owl species, including:

• the Accipitridae with 22 species

• the Falcons (Falconidae) with 5 species

• the True Owls (Strigidae) with 8 species.

Forest birds are particularly diverse. Highlights include:

• the Woodpeckers (Picidae) with 18 species

• the Old-World Flycatchers (Muscicapidae) with 49 species

• the Laughingthrushes and allies (Leiothrichidae) with 26 species

• the Old World Babblers (Timaliidae) with 9 species

• the Jungle Babblers (Pellorneidae) with 6 species

• the White-eyes (Zosteropidae) with 7 species.

The warblers are also richly varied and include:

• the leaf warblers (Phylloscopidae) with 17 species

• the bush warblers and allies (Scotocercidae) with 12 species.

With so few surveys taking place in the summer monsoon season (July to September), it is difficult to say anything meaningful about seasonal variation. However, it is noticeable that in the CLP project surveys and on ebird (2024a), the Western Hooded Pitta was only observed in the monsoonal period).

In the CLP project, it may be meaningful that the Orangeheaded Thrush and Blue-throated Flycatcher were only collected in mistnets during the monsoon period. The Orange-headed Thrush has never been reported from the IBA on ebird (2024a) or GBIF, although it is included in Spierenburg (2005) from the area and in Avibase.

The Blue-throated Flycatcher is listed on Avibase, GBIF, and ebird from the area but has not been reported on ebird since 24 April 2019 (further information). Similarly, the Fire-capped Tit was only observed on ebird once and this was in August 2023 (further information).

No data were collected systematically on other fauna, except for bats. However, interesting sightings included:

Deothang-NSJ IBA is home to a range of snake species. Chance observations included a young King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) observed just outside the eastern border of the IBA (Fig. 23). This record has been included on a new iNaturalist page, set up by the CLP project team, especially for Bhutanese wildlife road-kills (Fig. 21). The King Cobra, which is considered to be Vulnerable (VU) by IUCN, has been previously recorded from Bhutan, although not from the Deothang-NSJ IBA area (Bhutan Biodiversity Portal). Other snake species encountered included: the Banded Krait (Bungarus fasciatus), the Buffstriped Keelback (Amphiesma stolatum) and Light-barred Kukri Snake (Oligodon multicinctus) (Fig. 22). All are considered Least Concern (LC) by IUCN.

The Bengal Monitor Lizard was also observed. This is a Near Threatened (NT) species. Despite being previously recorded from Phuntsholing and Samchi, there appears to be only a small number of records from Bhutan (Bhutan Biodiversity Portal).

The large mammals include Asian Elephant (VU), tracks of which were seen in the forest. The Elephant Conservation Action Plan for Bhutan indicates that this area is well suited to elephant populations (NCD, 2019) (Fig. 27).

The area is less suited to tigers, even though Royal Manas National Park to the west is a hotspot of tiger populations (DoFPS, 2023) (Fig. 27 below).

A single Northern Red Muntjac (Muntiacus vaginalis) and East Asian Porcupine were observed. Grey Langurs and Assam Macaques are relatively common.

were seen in the forest. The Elephant Conservation Action

The area is less suited to tigers, even though Royal Manas National Park to the west is a hotspot of tiger populations

Elsewhere in Bhutan, the protected area system is known

Various squirrel species were also common. A road-kill included the Black Giant Squirrel (Ratufa bicolor), a Near Threatened (NT) species.

Elsewhere in Bhutan, the protected area system is known to contribute to the conservation of a wide range of mammal species (Dorji et al., 2019).

No bat research has taken place in the IBA prior to the recent study.

As part of the CLP project, a survey of bats, using hand nets, mist nets, harp traps, and acoustic bat detectors was

conducted in intact and degraded forest and in ‘caves’ and amongst boulders.

The team included trained biologists (a staff member of PMSS and a scientist from the Prince of Songkla University Natural History Museum), a staff member of the Forest Department, and a number of school children from PMSS.

Bat research took place primarily in the months of July September and December. Seventeen bat species of seven bat families were captured (Table 1 ). Three taxa have yet to be identified. However, at present, it appears that all species have a conservation status of Least Concern (LC).

The most abundant species was the Short-nosed Fruit Bat (Cynopterus sphinx), which is widely distributed in southern and South-east Asia.

Although no botanical literature was found relating specifically to Deothang-NSJ IBA, Samdrup Jongkhar District is known to support some rare, endangered and critically endangered flowering plants (Tshwegang et al., 2021).

These include:

• Saurauja punduana CR

• Ceropegia dorjei CR

• Aquilaria malaccensis CR

• Hypericum sherriffii EN

In addition, there are over 420 orchid species in Bhutan, including 14 that are endemic. Although, there are publications on Bhutan’s orchids, including Gurung (2006) and Dorji (2008), no literature was found which listed orchid species specifically for Deothang-NSJ IBA or even Samdrup Jongkhar District.

However, it is known that the critically endangered Paphiopedilum fairrieanum is present in the area (Tshering Samdrup, 2020). Meanwhile, a new species of orchid, Chiloschista himalaica, was described recently and is known to occur in the area of the IBA (Gyletshen et al., 2020).

Currently, there appear to be relatively few substantial threats to biodiversity in Deothang-NSJ IBA compared to many other areas of the Himalayas.

This is because human population density is low, there are relatively few roads, and the terrain is extremely precipitous in many areas, restricting access into the forest.

However, there are some potential threats, and these can be subdivided between those that originate within the IBA and those whose origin are either regional or global.

Girish and Srinivasan (2020) reported that there appears to be an upward elevational shift in bird distributions in response to climate change in the Eastern Himalayas. Meanwhile, Srinivasan and Wilcove (2020) looked at the interaction of climate change and habitat degradation on the survival rate of Himalayan birds. They concluded that those species living in intact forest are less vulnerable to climate change than those living in degraded/modified habitats.

In more general terms, Banerjee et al. (2022) have looked at the vulnerability of protected areas to climate change in the Eastern Himalayan region.

According to NBSAP (2014), pollution is seen as ‘an emerging concern’ in Bhutan. It stated that the ‘different sources of pollution are all indicative of the rapid socioeconomic development, urbanization, increasing population densities in localized areas, and industrialization’ in Bhutan.

That said, in Deothang-NSJ IBA, except for coal mining (see below), domestic pollution, in most areas, is not yet a major concern, as the population density is so low.

However, air borne pollution from elsewhere in the Indian subcontinent is potentially a concern. A study by Ellis et al. (2022) suggests that the Eastern Himalayas will suffer from

No data were gathered as part of the CLP project on the impact of climate change on Deothang-NSJ IBA. However, studies elsewhere have shown the potential impact on Himalayan biodiversity. For example, Dahal et al. (2023) assessed the impact of climate change on the distribution of the Rufous-necked Hornbill in Bhutan; elsewhere in the Himalayas, pheasants have been a particular focus (Chhetri et al., 2021), including the Western Tragopan (Singh et al., 2020) and Himalayan Monal (Rai et al., 2020).

critically high levels of atmospheric nitrogen pollution (Fig. 36). This is driven by the extensive use of manure, slurry, and urea-based fertiliser in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. This leads to one of the highest concentrations of atmospheric ammonia (NH3) globally. The release of ammonia in turn leads to a nitrogen-enriched air mass that is pushed northwards during the summer monsoon months. This has significant consequences for the forests on the south-facing aspects of the Himalayas, including those in Bhutan. Once above a critical threshold, this atmospheric nitrogen has considerable negative consequences on biodiversity and ecosystem function (Ellis et al., 2022).

No data can be found on forest loss that relates exclusively to Deothang-NSJ IBA. However, data are available for the four subdistricts (Deothang, Phuntshothang, Jangchhubling, and Gomdar) of Samdrup Jonkhar, within which the IBA is mostly included.

Based on these figures (Table 2), there appears to be relatively little forest loss in the last decade.

Gomdar Subdistrict which includes a small part of the IBA (north-eastern section) has suffered the most, with a 1.1% decrease in primary forest and 1.9% loss of total tree cover. Deothang Subdistrict, in the south, has lost just 1.0% of its total tree cover.

These figures are surprisingly low in view of the repeated reports of trans-boundary smuggling of logs and other forest products from Bhutan into India (further information).

Meanwhile, anecdotal evidence suggests that those in the community who are extracting wood from the forest for fuel and other uses may, inadvertently, target trees that have the highest value for many species of wildlife. In particular, these are the most mature, dying and decaying trees, which provide essential feeding and nesting habitats for many species, especially hornbills, woodpeckers and other forest dependent birds.

In addition, community forests, whilst beneficial in many ways, may reduce habitats for a range of wildlife as management practices frequently favour removing the understorey of bushes and other vegetation which is essential for a rich diversity of wildlife.

Elsewhere in the Eastern Himalayas, forests are being lost at varying rates. It is thought that by 2100 only 10% of the land area of the Indian Himalayas will be covered by dense forest and that this will lead to the extinction of a quarter of endemic species of fauna and flora (Pandit et al., 2006). In addition, research in Africa has shown that the full impact of forest degradation and fragmentation on bird diversity and abundance may take several decades to be realised. This means that the effects may be far worse than it originally apparent (Brooks et al., 2008).

It is expected that within Deothang-NDJ IBA, towns such as Deothang, Samdrup Jongkhar, and Phuntshothang will continue to grow. This reflects a national trend that sees a rural population increasingly moving to urban centres. This is/will lead to increasing urban sprawl with an impact on the surrounding forested areas and the potential for accelerated forest loss. Conversely, there has also been a reduction in land area under cultivation. This may allow forests to gradually recolonise areas previously used for agriculture.

Below:

Within Deothang-NSJ IBA, there has been a recent upgrading of roads (Department of Roads, 2017), including:

• the Primary National Highway (PNH3), which runs south from Trashigang (Trashigang District) to Samdrup Jongkhar and the Indian border

• the Secondary National Highway (SNH11), which runs east from Deothang to Samrang by way of Phuntshothang (Fig. 32).

Although roads are important contributors to the quality of life for rural communities, they impact adversely on most biodiversity.

First: by the destruction of habitat during their construction (Fig. 32).

Second: by enabling the extraction of timber and other forest products from previously remote, inaccessible areas.

Deothang-NSJ IBA is home to two working coal mines, Tshophangma and Habrang and some smaller abandoned mines. The large mines are both operated by the Government of Bhutan’s State Mining Corporation. They are surface mines with a capacity of 0.04 million and 0.06 million tons of sub-bituminous thermal coal, respectively. The mining corporation tries to support the local community by creating employment and other economic opportunities. Once extracted the coal travels by truck to Deothang.

Although, Bhutan has a requirement for coal, particularly

for its cement and ferro-alloys industries (IRADe-SARI-27, 2021), most of the coal from the Deothang-NSJ IBA area is exported by way of the Indian border at Samdrup Jonkhar. No information was seen on environmental impact of the mines. However, they have led to habitat loss in their immediate vicinity and contributed to the urban expansion of Phuntshothang (Fig. 31). The level of pollution, including in the near-by Puthimari River, is not known.

Elsewhere, the dolomite/limestone mines of Pugli (Phuntshopelri) in south-west Bhutan have caused considerable environmental damage (deforestation, landslides, pollution of the soil and water), affecting biodiversity and agriculture (Yakra, 2023).

In some areas of Bhutan fire is a major contributor to forest loss and environmental degradation (Fig. 34). However, Deothang-NSJ IBA is situated in a low-risk area for fire (UNDP, 2021).

No data were gathered on human-wildlife conflict, as part of the CPL project. However, anecdotal evidence suggests it is a problem for local farmers within Deothang-NSJ IBA. Studies elsewhere in Bhutan have shown that 55% of crop losses can be attributed to wildlife and that on average households spend 110 nights a year guarding crops.

Human-wildlife conflict is one of the more important contributory factors that is leading to the abandonment of agricultural land and a drift of the rural population to urban areas throughout Bhutan.

Meanwhile, the social and economic cost of the conflict leads to retaliatory killings by farmers and resentment of conservation initiatives (NBSAP, 2014; Tshewang et al., 2021).

With its highly diverse fauna and flora, fascinating culture, and spectacular landscapes, Bhutan is well positioned to capitalise on an ever-expanding market of nature tourism.

Deothang-NSJ IBA, with at least 447 bird species, including many rare and range-restricted taxa, already features on a number of national and international bird tour itineraries, such as Birding the Strait and Odin Tours.

Positioned on the Primary National Highway (PNH3), which runs south from Trashigang (Trashigang District), via Yonphoogla Airport to Samdrup Jongkhar on the Bhutan-India border, it has an accessible location, especially when the Samdrup Jongkhar border crossing to India is open. There is also accommodation available for both national and international visitors in the Samdrup Jongkhar area, including at the Tashi Gasel Lodge, which is often frequented by bird watchers. Accommodation and restaurants are also available in Phuntshothang and there are a range of eating places in Deothang.

The preparation of this first-phase Conservation Management Plan results from a project entitled ‘Schoolsbased, science-based participatory approach to conservation in Bhutan’, which was funded by CLP (the Conservation Leadership Programme).

The project had four principal objectives:

1. To inspire personal responsibility and active involvement of school children in biodiversity science and conservation

2. To undertake field studies to provide scientific data on the intensity of threats and importance of Deothang-NSJ IBA for rare and range-restricted species

3. To raise awareness and build consensus amongst key stakeholders (CSOs, Forest Department, and local communities) for conservation action

4. To deliver a first-phase Conservation Management Plan for Deothang IBA, which would advocate for sustainable management and protection and provide a baseline against which future conservation actions can be measured.

Institute, Swen Renner (PhD) of the Natural History Museum Vienna, Marcela Suarez-Rubio (PhD) of BOKU, Vienna, and Pipat Soisook (PhD) of the Prince of Songkla University, Thailand . The international team helped with the training of teachers and pupils in different aspects of bird and bat research, remote sensing, and nature study for the younger children.

The project was based at Phuntshothang Middle Secondary School (PMSS), which is located adjacent to the eastern border of the IBA.

It was led by Mr Tshering Dendup (MSc) who is a qualified ecologist a staff member of the school, and head of the school’s Nature Club. It was supported by Ms Tshering Yangzom (BSc) and additional PMSS staff members, and by Ms Maylem Zangmo, a Forest Ranger in the Department of Forests and Park Services (Fig. 45).

Further scientific and financial support were provided by Paul Bates (PhD) and Ms Beatrix Lanzinger of the Harrison

All 68 staff and 972 pupils of Phuntshothang Middle Secondary School were aware of the project, including its aims and activities. Over 70 pupils, including all members of the Nature Club participated in at least one project activity (some participated in 3 or more), including: bird surveys, bat surveys, lessons-in-a-box (for younger children) and remote sensing. There were over 50 bird surveys, including 12 days of bird netting with 10 nets/day. There were over 30 bat surveys.

The project responded to four in-country priorities:

1. RSPN’s (Royal Society for the Protection of Nature, Bhutan) initiative ‘Environmental Education for Change’, which seeks to “inspire personal responsibility and active involvement of people of Bhutan in conservation through education”, and the development of School Nature Clubs

2. BBS’s (Bhutan’s Birdlife Society) objective of assessing and monitoring Bhutan’s 23 IBAs (Important Bird Areas) (for further information)

3. Department of Forests and Park Services’ mission of conserving species and providing training of current and future generations of conservation and environmental leaders, practitioners and academics in Bhutan,

4. CEPF’s (Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund) priorities for the Bhutan Biological Conservation Complex, including targeting conservation awareness programmes in schools and developing grassroots civil society organisations to manage, monitor and mitigate threats to biodiversity (Priority 1.3).

The bird data for this Conservation Management Report come from two citizen science sources, ebird and the CLP project.

• ebird provided a list of 447 species reported from Deothang-NSJ IBA. This list is based on 576 checklists which have been submitted by a wide range of predominantly amateur bird watchers, Bhutanese and international. The earliest record available is 1996. In addition, ebird provides access to 133 lists (discounting duplicates submitted for the same observations but by different individuals), which together comprise 1502 records. In this section of ebird, the earliest currently available online is 29 November 2019 and the most recent 31 December 2023 (although this will change as new reports are published).

• the CLP project provided up-to-date groundtruthing for the desk-based study. Comprising trained biologists, professional ornithologists, staff of the Forest Department, and staff and pupils from Phuntshothang Middle Secondary School (PMSS), it gathered data in two ways:

o netting of birds in a range of intact and variably degraded forest

o systematic point counts of birds and additional opportunistic observations. Prior to the release of the birds, it took blood samples in order to study avian malaria and other parasitic diseases.

Together ebird and the CLP project are a very valuable data source. They represent thousands of hours of bird observations, which would otherwise be unavailable to science and conservation. However, they also both have their limitations.

The ebird data only provides information on bird observations that are deemed interesting by the bird watchers. Almost all the lists are incomplete. The mean number of species recorded is 11.3 and the range is 1 to 84. Almost half of the lists (48.9%) record 5 species or less.

Furthermore, the reporting is no doubt biased towards those bird species that are most easily observed and are ‘charismatic’ in some way – large, rare, vocal, brightly coloured. Some of the more difficult to identify species, especially small drab species that occupy the forest understorey are under-reported. Therefore, the lists do not say anything meaningful about abundance, except in the broadest of terms.

The 15 most commonly reported species on ebird for Deothang-NSJ IBA are listed in Table 3. Four of the top seven are bulbuls. All are easy to observe and vocal. The Scarlet Minivet is particularly colourful and is the fifth most common sighting. The two hornbill species, at 11th and 13th are spectacular. The two drongo species are easy to see and identify in the field.

As noted above, there is also seasonally bias, with only 5% of checklists from the summer monsoon and autumn period (the five months from July to November).

The distribution of reporting sites is quite widespread (Fig. 16). However, hotspots particularly favoured by bird watchers include: Tasi Gashel Lodge to Samdrup Jongkhar in the south of the IBA (with 288 species recorded); Powerhouse Road, to the north of Deothang (with 310 species recorded) and Morong, the midpart of the IBA (with 138 species recorded).

In contast to ebird, the netting programme of the CLP project provided much information on low-flying, forest interior birds, such as Puff-throated and Gray Babblers, Rufous-bellied Nivalta, and Western Hooded Pitta. It is noteworthy that of the 14 species collected most often in mist nets, only one, the Common Tailorbird, appears in the most frequently reported on ebird (2024b) from Deothang-NSJ IBA (Table 3).

It is of interest to note that one species collected in the netting programme, the Orange-headed Thrush, has never been recorded from the area on ebird (2024b). Furthermore, species such as the Pygmy Flycatcher, which was captured on Day 3 of the netting programme was reported only once in 133 ebird reports from the IBA.

The netting programme, especially if it is extended in time and geographical area, would provide very valuable information about diversity, composition, distribution and abundance of forest understorey birds.

To help ensure long-term protection for Deothang-NSJ IBA, the project aimed at involving as many families within the local community as possible.

For younger pupils, it was not feasible to take them into the field for bird or bat mist netting. Therefore, the Nature Club of the Phuntshothang Middle Secondary School organised a series of lessons particularly targeted at children aged from 6 to 11 years old.

Topics included the importance of trees, pollination, and plastic waste. Lessons involved a wide variety of media, including learning songs and performing to the whole school at assembly, drawing, craft work, films, and interactive learning.

Led by Tshering Yangzom and inspired by international specialist Beatrix Lanzinger who provided advice on innovative approaches, the children responded positively to this immersive style of learning.

For older children (primarily between the ages of 15 and 18 years old) who wished to be involved in the CLP project but were less interested in the field studies, a class-based alternative was provided.

For these children, visiting scientist Dr Marcela SuarezRubio of BOKU, Vienna developed a practical programme on remote sensing. It was based in the school’s computer room.

Although academically rigorous and requiring good computer skills, the children accepted the challenge and worked with keen interest and notable enthusiasm. This clearly illustrates the further potential for schools to play an ever-increasing role in quite sophisticated research that will ultimately help conserve the biodiversity and natural landscapes that surround them.

was conducted in intact and degraded forest and in ‘caves’ and University

school children from PMSS.

The CLP project provided some answers and a lot of questions. Many of these questions make for ideal follow-up projects, some of which can incorporate a sizeable citizen science component, including the participation of schoolteachers and school children. Follow-up projects and ideas include:

• A project that provides a better understanding of the seasonal variation in bird faunas (migration), focusing particularly on gathering further data from the summer monsoon and autumn seasons.

• A project that provides more information about the elevational gradient of bird faunas. This would provide a baseline for subsequent studies of the impact of climate change (see example of Girish and Srinivasan (2020)).

• Follow-up surveys of other diverse fauna within Deothang-NSJ IBA, including invertebrates, which are understudied throughout most of Bhutan.

• A project that focuses on the impact of urban growth on the bird fauna – the study would focus on a rural-urban gradient from intact forest to the centre of townships such as Phuntshothang or Deothang. This could be expanded to include a range of other taxa.

• A project that focuses on the environmental impact of the two working coal mines, Tshophangma and Habrang. This could include a science study for school pupils in measuring water pollution in the near-by Puthimari River.

• A project that looks at the rewilding process of abandoned mines to assess long-term implications of mining on biodiversity.

• A project that works with farmers and other stakeholders to assess the impact and possible solutions to humanwildlife conflict within Deothang-NSJ IBA.

• A project that looks at different forest management strategies (community forest, protected forest, forest plantations) to determine their impact on different faunal elements (vertebrate and invertebrate, and particularly high value species such as hornbills).

• A programme, involving a range of stakeholders to develop further innovative biodiversity research and conservation projects for schoolteachers and pupils.

• An enlarged programme to deliver assessments of biodiversity value and threats in all of Bhutan’s 23 IBAs.

Audubon (2024). Important Bird Areas. (downloaded 16/01/2024).

Banerjee, S., R. Niyogi, M.S. Sarkar, and R. John (2022). Assessing the vulnerability of protected areas in the eastern Himalayas based on their biological, anthropogenic, and environmental aspect. Trees, Forests and People, 8: 1-8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100228

BirdLife (2024a). Global IBA criteria. (downloaded 16/01/2024).

BirdLife (2024b). Bhutan. (downloaded 16/01/2024).

BirdLife (2024c). Bhutan, Data Zone (downloaded 15/02/2024).

BirdLife (2024d). Deothang-Narphung-Samdrup Jonkhar IBA. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

Bishop, K.D. (1999). Preliminary notes on some birds in Bhutan. Forktail, 15: 87-91.

Brooks, T.M., S.L. Pimm, and J.O. Oyugi (2008). Time lag between deforestation and bird extinction in tropical forest fragments. Conservation Biology. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

CEPF (2005). Eastern Himalayas Region: Ecosystem profile. (downloaded on 17/02/2024)

Chan, S., M.J. Crosby, M. Z., Islam and A.W. Tordoff (2004). Important Bird Areas in Asia: Key Sites for Conservation. BirdLife International. 297 pp.

Chettri, B., H.K. Badola and S. Barat (2021). Modelling climate change impacts on distribution of Himalayan pheasants. Ecological Indicators, 123: 107368.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107368

Dahal, D., A. Nepal, C. M. Rai and S. Sapkota (2023). Understanding the impact of climate change on the habitat of the rufous-necked hornbill (Aceros nipalensis) (Hodgson, 1829) using MaxEnt modeling in Bhutan. Ornithology Research 31(3): 182–192. DOI:10.1007/s43388-023-00130-8

Department of Roads (2017). Road classification system in Bhutan. Royal Government of Bhutan. Ministry of Works and Human Settlement. Department of Roads. 20 pp. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

DoFPS (2023). Status of Tigers in Bhutan: The National Tiger Survey Report 2021–2022. Bhutan Tiger Center, Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Royal Government of Bhutan, Thimphu, Bhutan. (downloaded on 17/02/2024)

Dorji, S. (2008). The field guide to the orchids of Bhutan. Bhutan: Bhutan Orchid Science Society.

Dorji, S., R. Rajanathan, and K. Vernes (2019). Mammal richness and diversity in a Himalayan hotspot: the role of protected areas in conserving Bhutan’s mammals. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28: 3277-3297. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

Ellis, C., C.E. Steadman, M. Vieno, S. Chatterjee, M.R. Jones, S. Negi, B.P. Pandey, H. Rai, D. Tshering, G. Werakoon, P. Wolseley, D. Reay, S. Sharma and M. Sutton (2022). Estimating nitrogen risk to Himalayan forests using thresholds for lichen bioindicators. Biological Conservation, 265: 109401. (downloaded on 17/02/24).

Girish, K.S. and U. Srinivasan (2022). Community science data provide evidence for upward elevational range shifts by Eastern Himalayan birds. Tropica, 54(6): 1457-1465. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.13133

Gogoi, B. (2024). Climate of Bhutan. (downloaded on 30/1/2024)

Gurung, D. B. (2006). An illustrated guide to the orchids of Bhutan. Thimphu, Bhutan: DSB Publication, GPO Box 435.

Gyeltshen, N., Gyeltshen, C., Tobgay, K., Dalström, S., Gurung, D.B., Gyeltshen, N. and Ghalley, B.B. 2020. Two new spotted Chilochista species (Orchidaceae: Aeridinae) from Bhutan. Lankesteriana, 20(3): 281-299. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/lank.v20i3.44149

KBA (2024). Deothang/ Narphang/ Samdrup Jongkhar KBA. (downloaded on 17/02/2024)

Kumar, T. (2020). Distribution and Threats of Rufous-necked Hornbill (Aceros nipalensis) in Bhutan. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 9(11): 797-800. DOI: 10.21275/SR201111231036

Lehner, F. and H. Formayer (2023). Insights on the climate of Bhutan from a new daily 1 km gridded data set for temperature and precipitation. International Journal of Climatology, 43: 4927-4943. DOI: 10.1002/joc.8125

NCD (2019). Elephant Action Plan for Bhutan (2018-2028). Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Thimphu, Bhutan. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

NCD (2023). Conservation action plan for hornbills of Bhutan (2023-2034): Ensuring Healthy Forests and Happy Hornbills. Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Royal Government of Bhutan. Thimphu Bhutan. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

NBSAP (2014). National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plan, Bhutan. 191 pp. (downloaded on 05/03/2024).

Pandit, M.K., N.S. Sodhi, L.P. Koh, A. Bhaskar and B.W. Brook (2007). Unreported yet massive deforestation driving loss of endemic biodiversity in India Himalaya. Biodiversity and Conservation, 16: 153-163. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

Pittie, A. (2009). A bibliography of the ornithology in Bhutan: 1838–2008. Indian Birds, 4 (6): 194–204. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

Rai, R., B. Paudel, C. Gu, N.R. Khanal (2020). Change in the distribution of national bird (Himalayan Monal) habitat in Gandaki River Basin, Central Himalayas. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 11(2): 223-231. DOI: 10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2020.02.010

Singh, H., N. Kumar, M. Kumar, and R. Singh (2020). Modelling habitat suitability of western tragopan (Tragopan melanocephalus) a range-restricted vulnerable bird species of the Himalayan region, in response to climate change. Climate Risk Management, 29: 100241.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100241

Spierenburg, P. (2005). Birds in Bhutan: status and distribution. Oriental Bird Club, Bedford, UK. 383 pp.

Srinivasan, U. and D.S. Wilcove (2020). Interactive impacts of climate change and land-use change on the demography of montane birds. Ecology, 102(1): e03223.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3223

Stattersfield, A.J., M.J. Crosby, A.J. Long and D.C. Wege. (1998). Endemic Bird Areas of the World: priorities for conservation. BirdLife Conservation Series No 7. BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK. 846 pp.

Tshewang, U. M.C. Tobias and J.G. Morrison. Bhutan: conservation and environmental protection in the Himalayas. Springer. 353 pp.

UNDP (2021). Assessment of climate risks on forests and biodiversity for National Adaptation Plan (NAP) formulation process in Bhutan. 89 pp. (downloaded on 17/02/2024).

Waliczky, Z., L.D.C. Fishpool, S.H.M. Butchart, D. Thomas, M.F. Heath, C. Hazin, P.F. Donald, A. Kowalska, M.P. Dias, and T.S.M. Allinson (2019). Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs): their impact on conservation policy, advocacy and action. Bird Conservation International, 29: 199-215.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270918000175

Wikramanayake. E., E. Dinerstein, C.L. Loucks et al. (2002). Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a conservation assessment. Island Press, Washington. 642 pp.

Wildlife Conservation Division (2010). Regulatory Framework for Biological Corridors in Bhutan Part III: Policy Recommendations and Framework for Developing Corridor Management Plans. (downloaded on 30/01/2024).

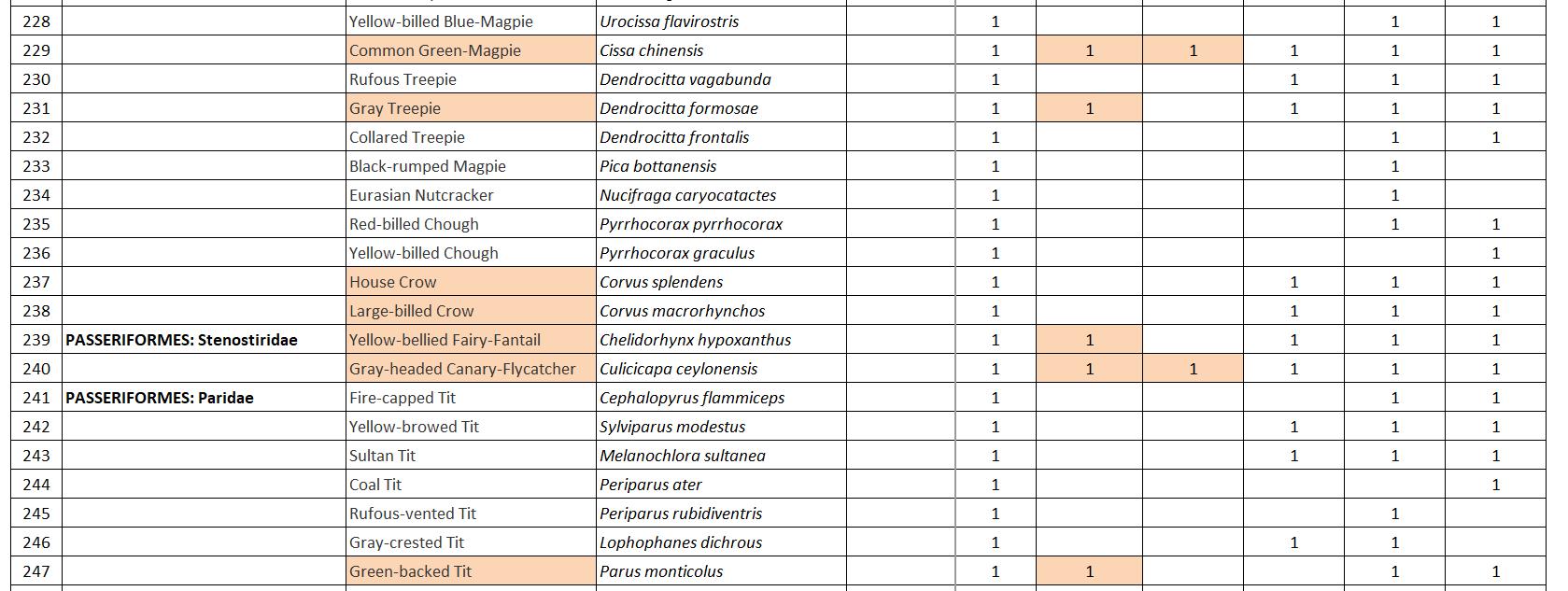

APPENDIX 1: The number of species recorded from Deothang-NSJ IBA depends on the source. Here, data from CLP (Conservation Leadership Project), Spierenburg (2005), and ebird are included.

The common and scientific species names follow Avibase (including spelling) and they are listed in the order that they appear on Avibase. All species are categorised by IUCN as Least Concern (LC) unless otherwise stated (highlighted in blue).

The two CLP lists refer to all species seen (observed and captured in mist nets), and just those captured in mist nets, respectively (both marked in pale orange). Data from Spierenburg (2005) has been obtained from the maps provided for each species in his book. GBIF occurrence data are based on a polygon that approximates to the boundaries of DeothangNSJ IBA. ebird data refers to Deothang-NSJ IBA exclusively.

Contact Details

Tshering Dendup, & Tshering Yangzom, ……………

Paul Bates & Beatrix Lanzinger, Harrison Institute, Bowerwood House, 15 St Botoloph’s Road, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 3AQ, UK.

Swen Renner, Natural History Museum Vienna, Burgring 7, 1010 Vienna, Austria

Marcela Suarez-Rubio, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), Gregor-Mendel-Straße 33, 1180 Vienna, Austria

Pipat Soisook, Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Natural History Museum, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla 90112, Thailand