Garnets on the Boulder: Jay DeFeo Paintings of the 1980s

Garnets on the Boulder:

Jay DeFeo Paintings of the 1980s

Garnets on the Boulder:

Jay DeFeo Paintings of the 1980s

October 30 – December 13, 2025

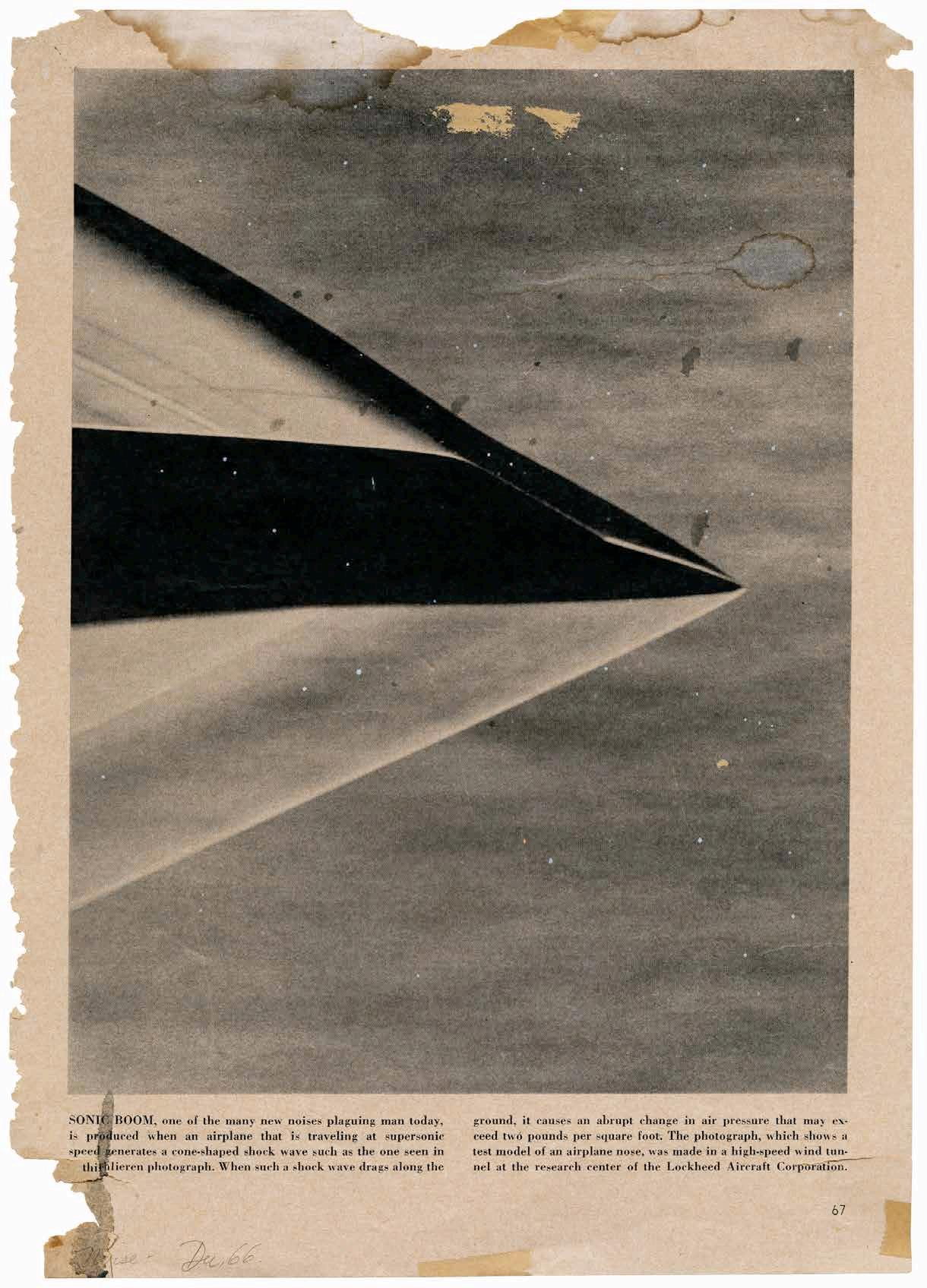

Page torn by DeFeo from Scientific American magazine (Dec. 1966), from the article “Noise,” showing a photograph of the nose of an airplane and a sonic boom shock wave, 1966

Previous page: Jay DeFeo in her studio in Oakland, California, 1986

GARNETS ON THE BOULDER

I saw a couple things on TV — one about a grist mill — with wheels & some kind of spatial image that riveted me — & as if in a dream it was gone before I could grasp it — even a clumsy sketch. Along with that was a wildlife special on snakes. & the colors of red, black, yellow white — — — (maybe?) These fleeting images truly are like dreams. Nailing it down seems to remove the magic. & one can only hope to discover another in ptg — (while trying to “nail down” something else.) It’s a slippery fish.

Jay DeFeo, journal entry, August 13, 1984

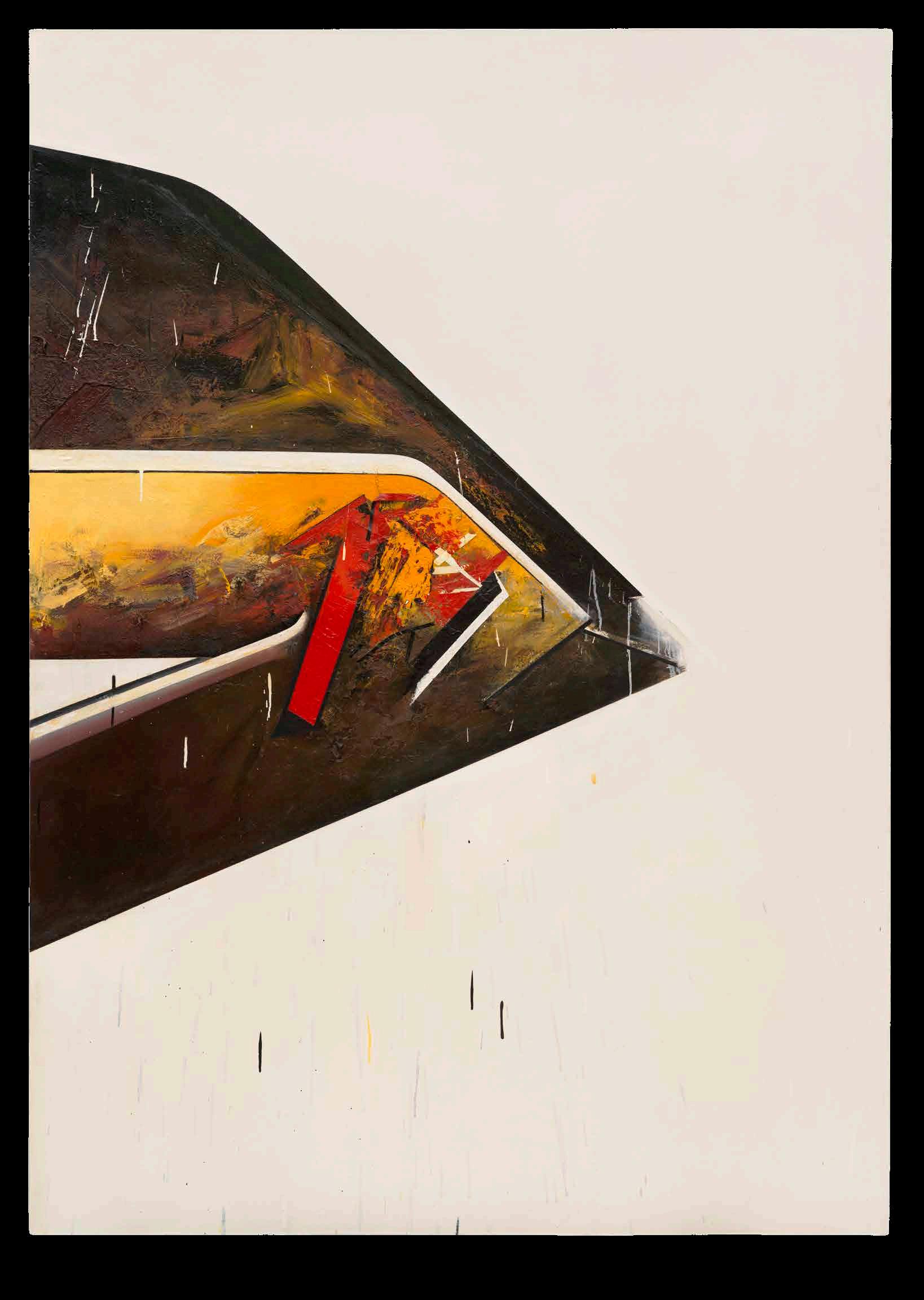

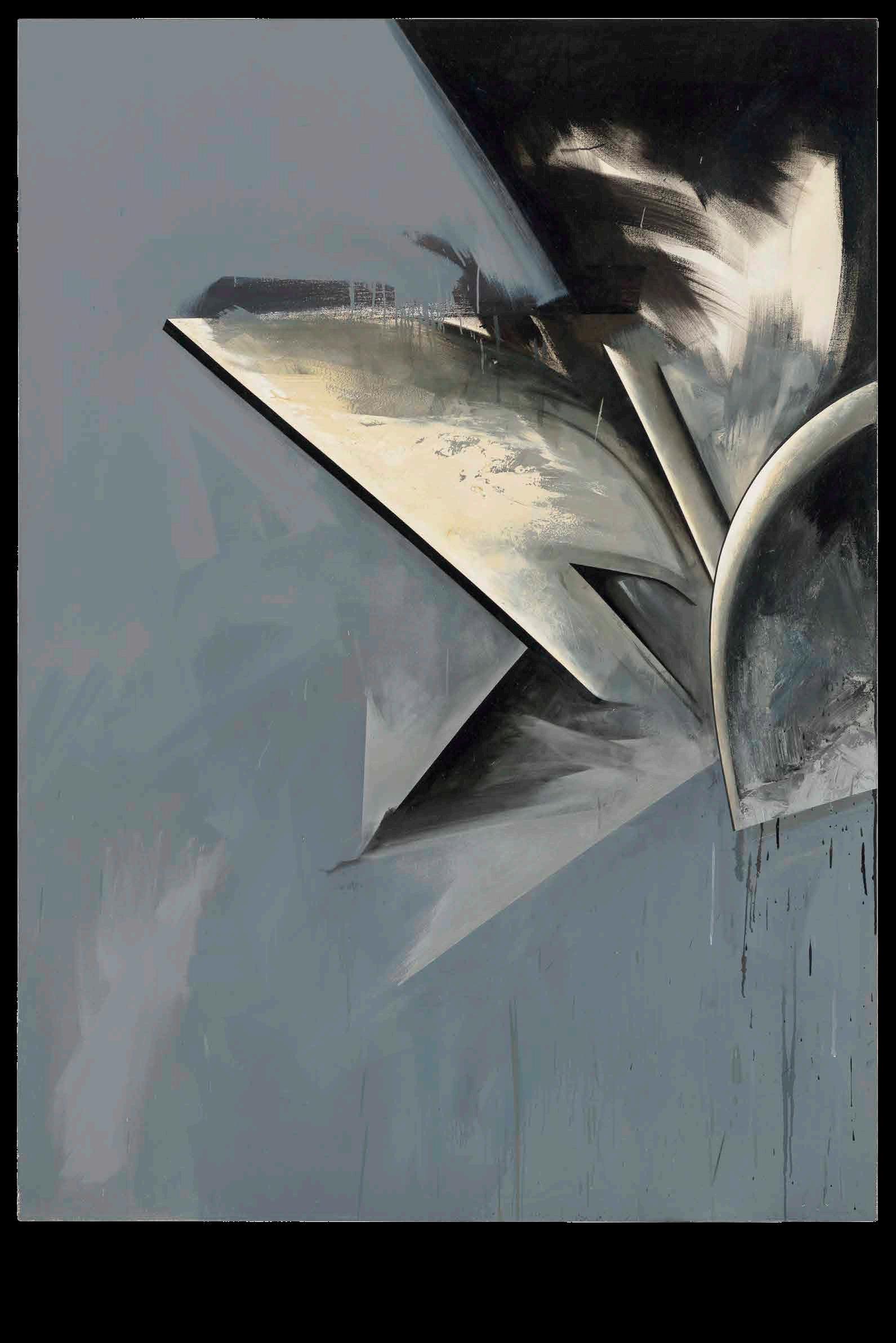

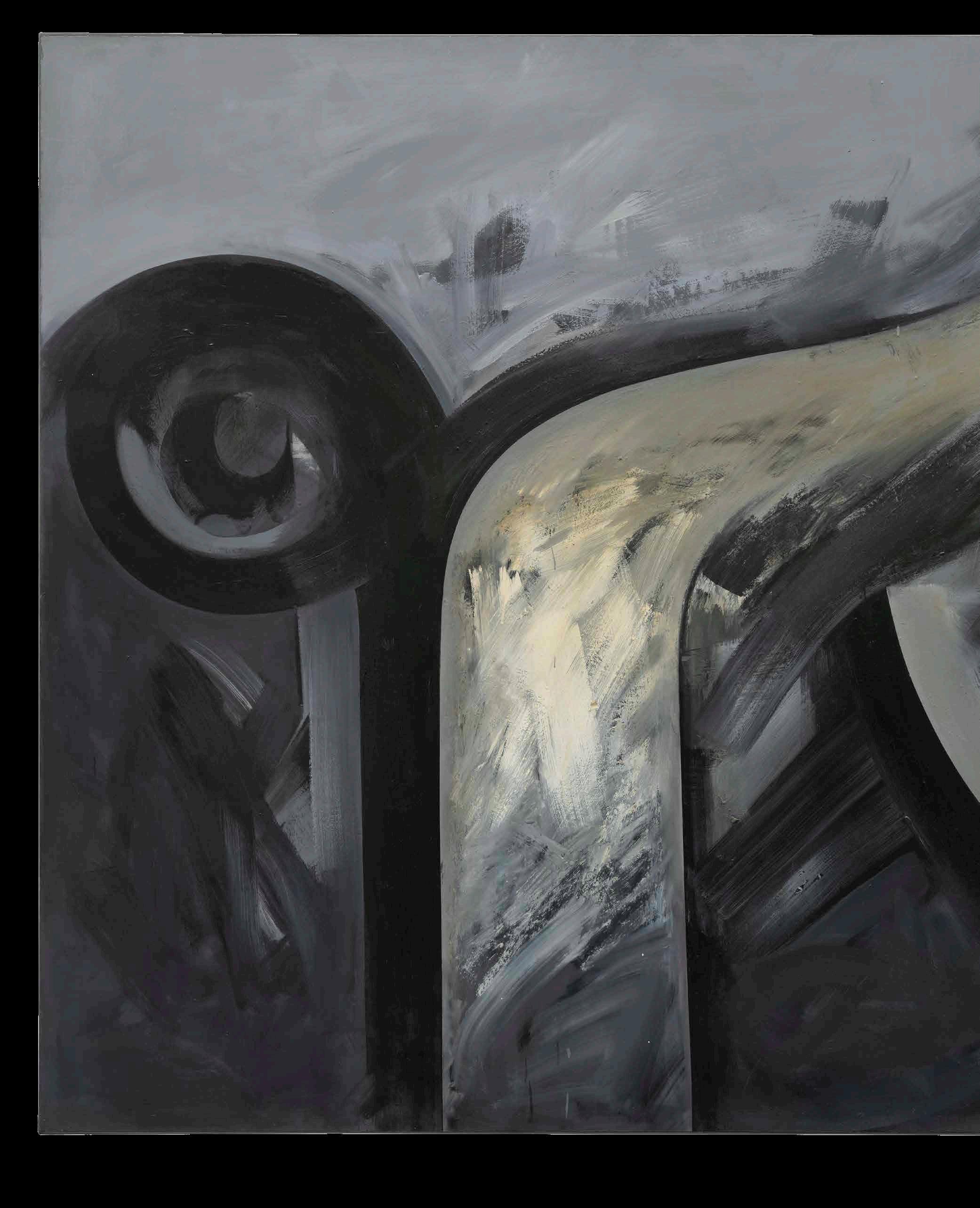

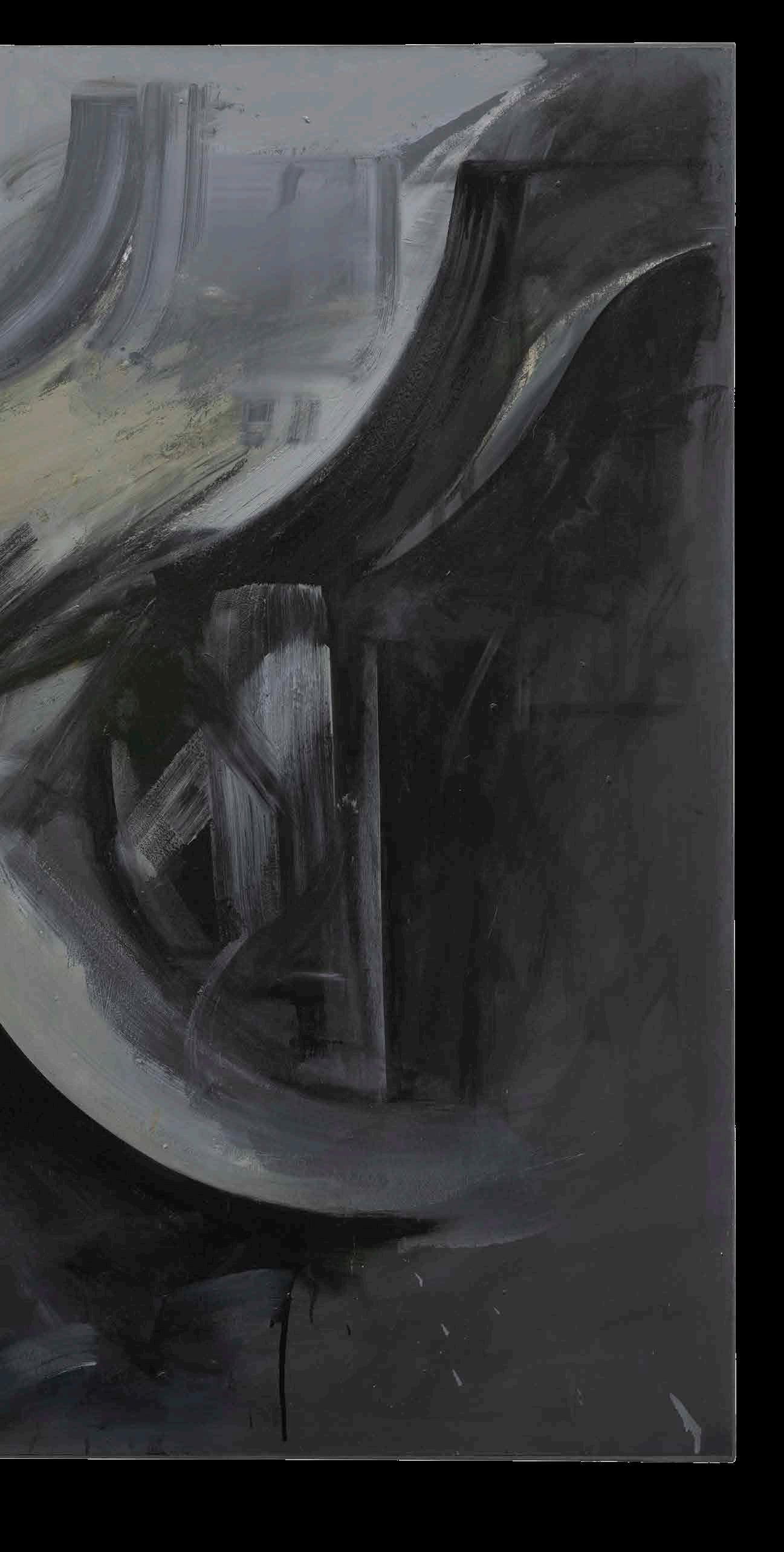

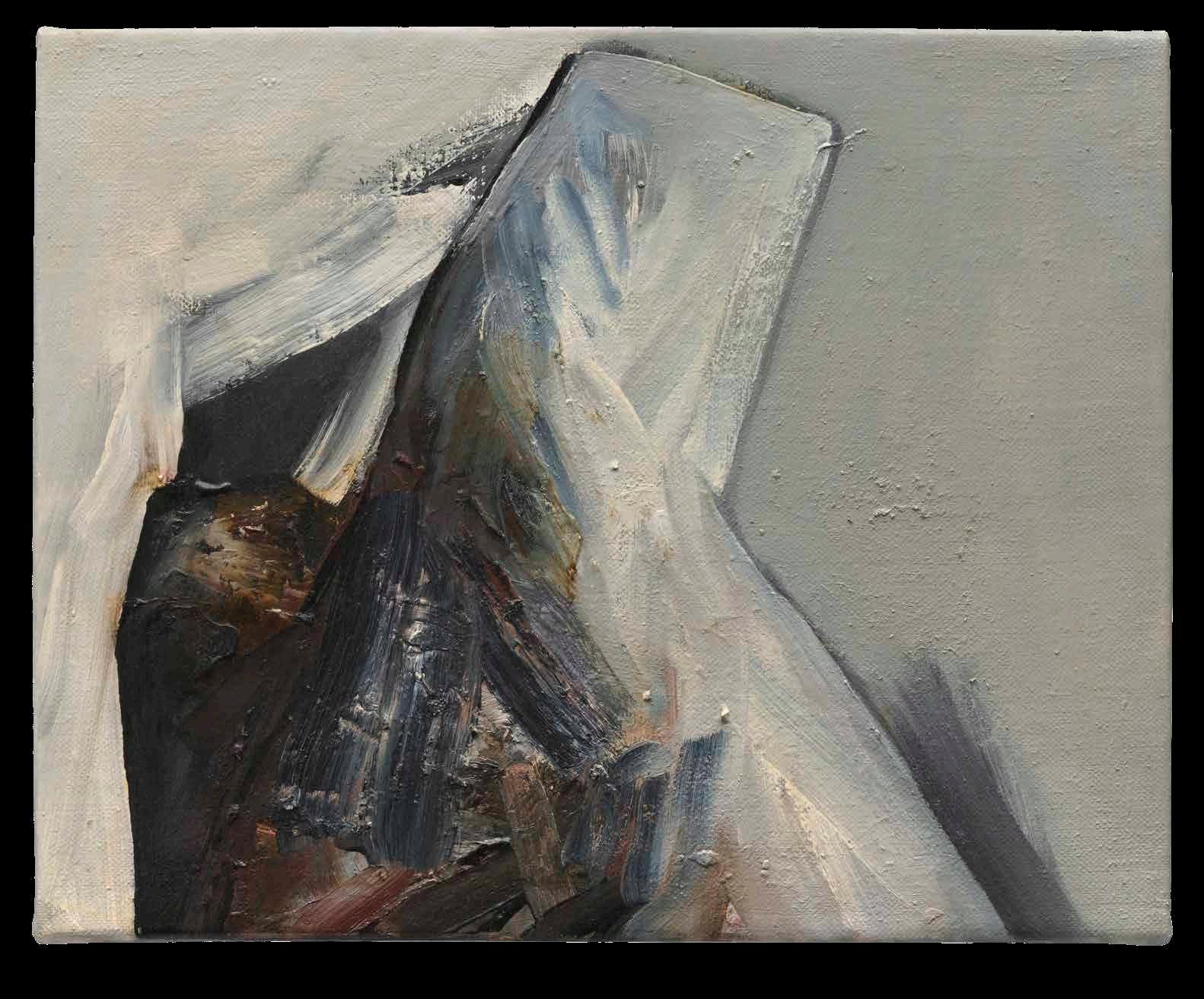

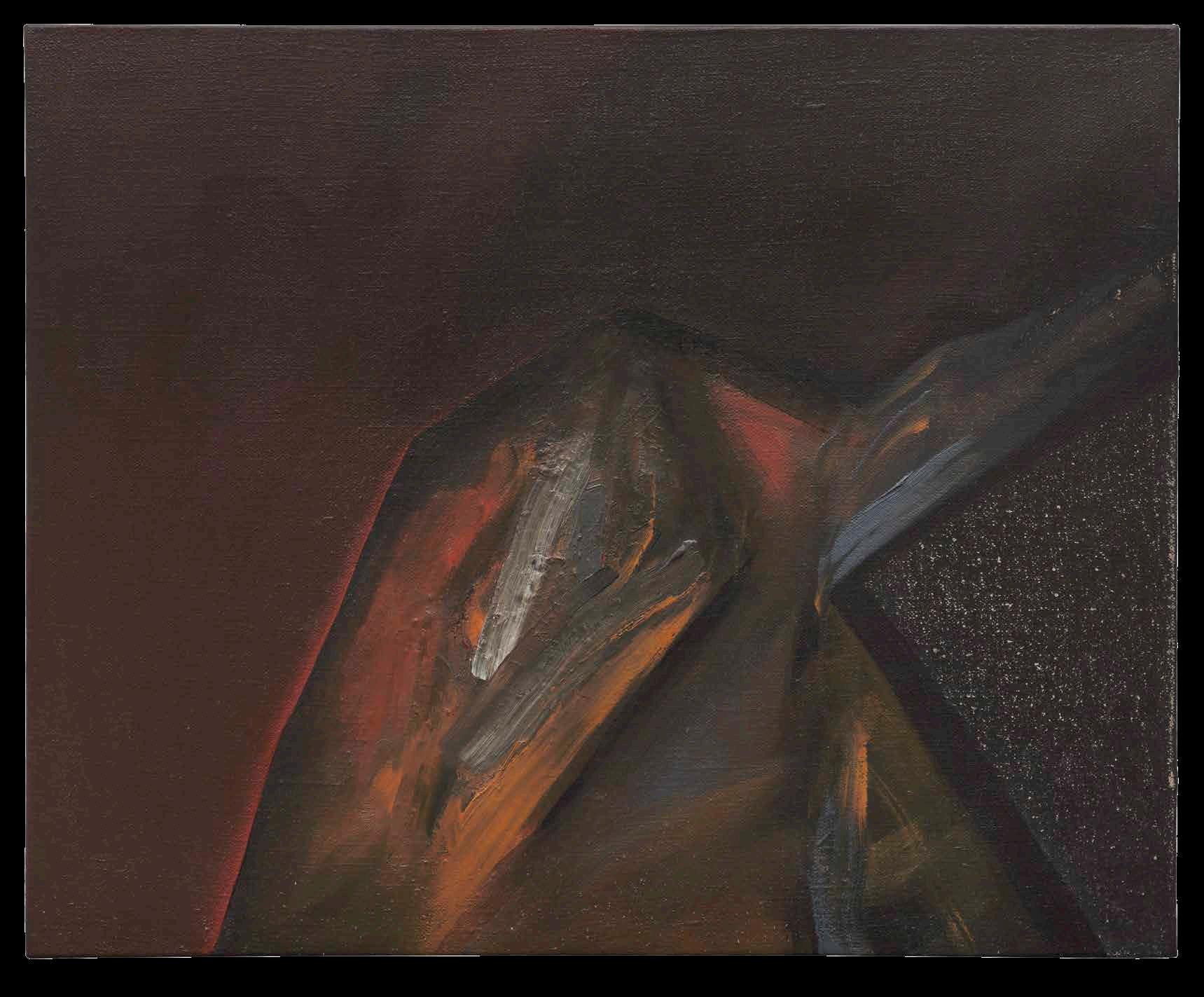

Jay DeFeo painted Verdict No. 1 in 1982 (detail, overleaf; fig. 1), and it was shown publicly only once in her lifetime. We know from the many process photographs she made in the studio that a torn page from a 1966 issue of Scientific American was taped to her wall during the work’s production. The image is abstract, the nose of an airplane as it bursts beyond the speed of sound. One assumes she liked how it looked, but also that it looked — an instant of arrested phenomena. The photo caption indicates that a sonic boom occurs when an airplane traveling at supersonic speed generates a “cone-shaped” shock wave that “causes an abrupt change in air pressure that may exceed two pounds per square foot.”

DeFeo came of age in San Francisco, but never joined a club; neither beatnik nor hippie nor punk, she was always and only an artist. Change was in the air, so why not change the air itself?

Verdict No. 1’s materials are listed as oil and tape on canvas, but letters indicate that she incorporated roofing compound, which “has a nice gooey look” when mixed with white, and that a friend, curator Phil Linhares, gave her some “Mt. St. Helens ash” to employ. “Adore it!” she wrote. And, the painting does have a molten character — fleshy passages where hot and rusty yellow, orange, and brown come together in heavy-duty impasto. She’s after the edges of things, too, and the painting — like most of the paintings in this exhibition — is a medley of hard and soft, unruliness and restraint.

Bits of red, black, and white tape adorn the surface of Verdict No. 1, even hanging off in places, glossy reminders of DeFeo’s whatever-it-takes approach. In fact, adhesive is an important element in its seven-foot-tall atmosphere, part of the real miracle that makes the provisional nature of the painting — and perhaps all painting — feel immutable. The majority of the canvas is covered in a field of white that hosts occasional drops of colored paint like rain or spit.

The motion of the painting moves like a sentence from left to right as a near-triangle points off the page. It’s the razor’s edge, the tip of a pencil, a beak. Look closer, though, and you’ll see that there is no tip, she’s done away with it. Object and background merge under such conditions, or vanish altogether at such speeds.

DeFeo made art, not exhibitions, and curator Dana Miller notes that in the early 1980s, for the first time in her life, she worked toward the deadline of a gallery show. It’s a wonder she survived all those seasons, an artist in the wild. The early

Jay DeFeo, view of studio in Oakland, California, with Verdict No. 1 in progress. At left are photocopies of works from the Plow series and a page from Scientific American magazine, 1982

1980s also marked DeFeo’s return to oil paint after sixteen years, her first use of the material since The Rose, that rare 2,000-pound artwork whose whole is far greater than the sum of its parts. She painted The Rose over seven years in her famously bohemian Fillmore Street apartment, punctuated by small mountains of paint and dead Christmas trees. (Her masterpiece is presently on view again at the Whitney Museum of American Art.)

DeFeo moved out of the city post-Rose and took to photography, photocopy, collage, painting in acrylic, and to an iterative, self-composting process that broke down and reassembled media in a dizzying array of forms. Her present often literally contained her past; she trashed very little. While her work from this period is extraordinary, her professional prospects were not. (The Rose, for example, was hidden behind a false wall at the San Francisco Art Institute until after her death.) As the decade turned, and with a new teaching job and larger studio, she may have specifically invested in a more visible future for her work, whether or not she could have predicted it.

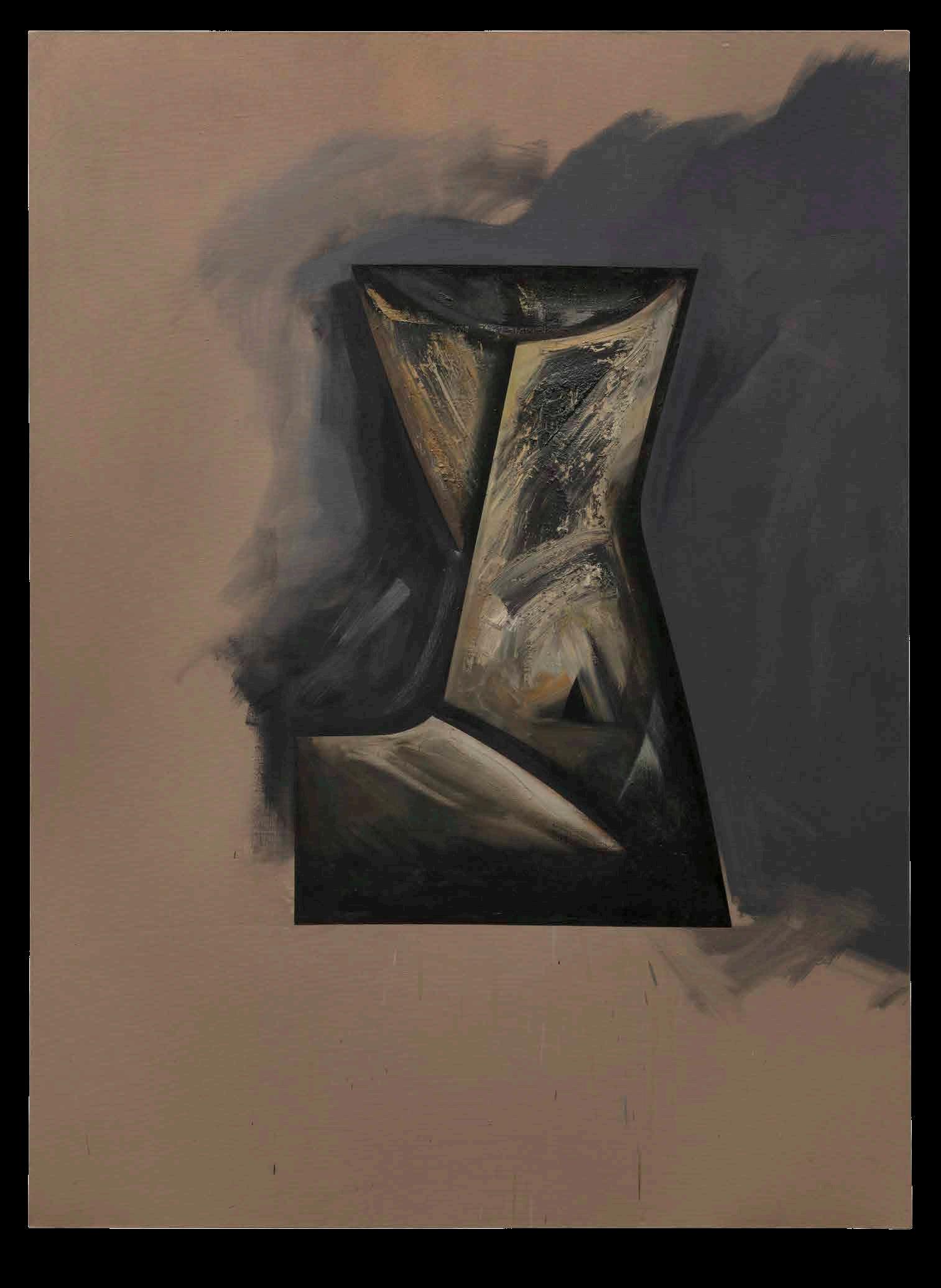

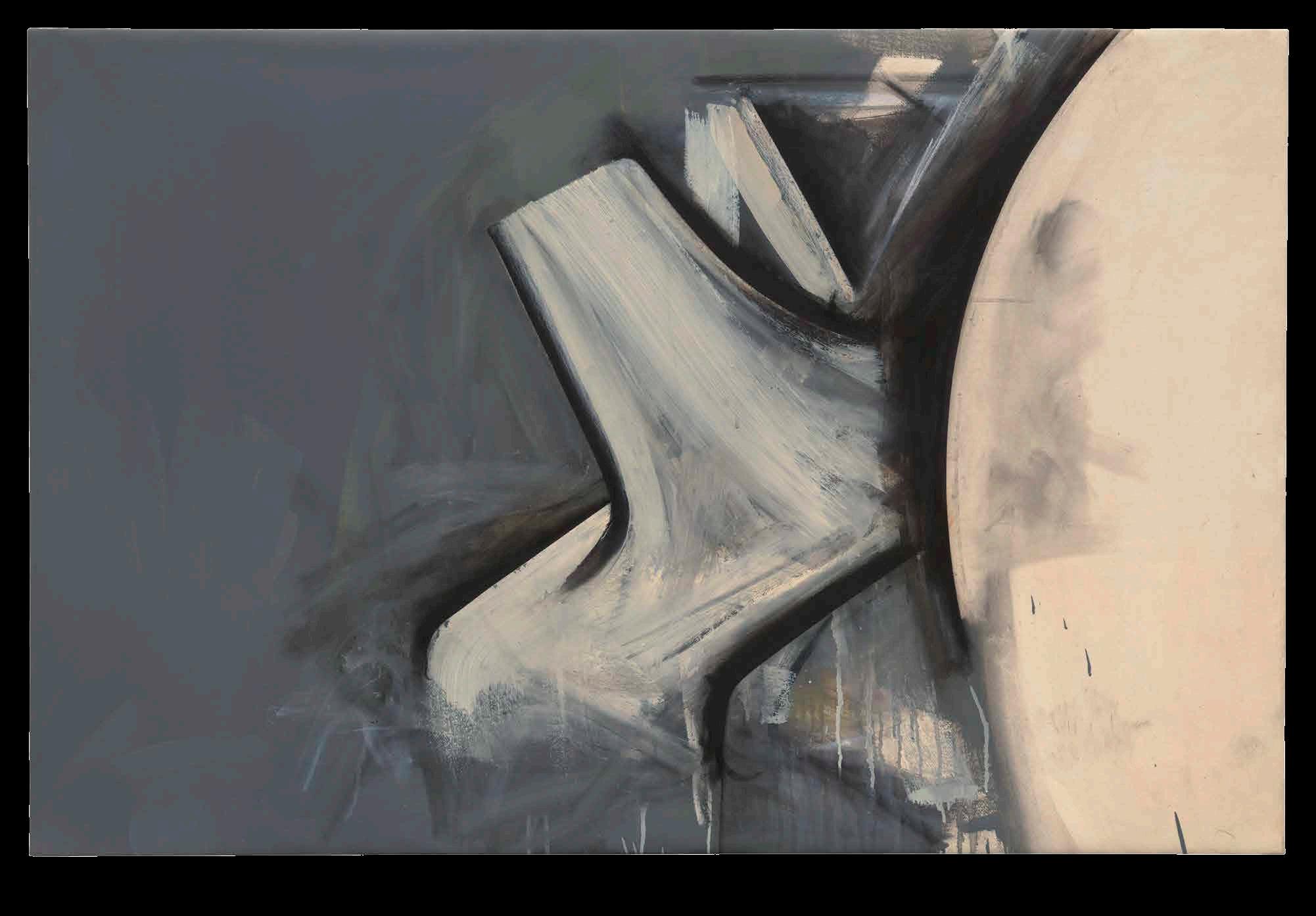

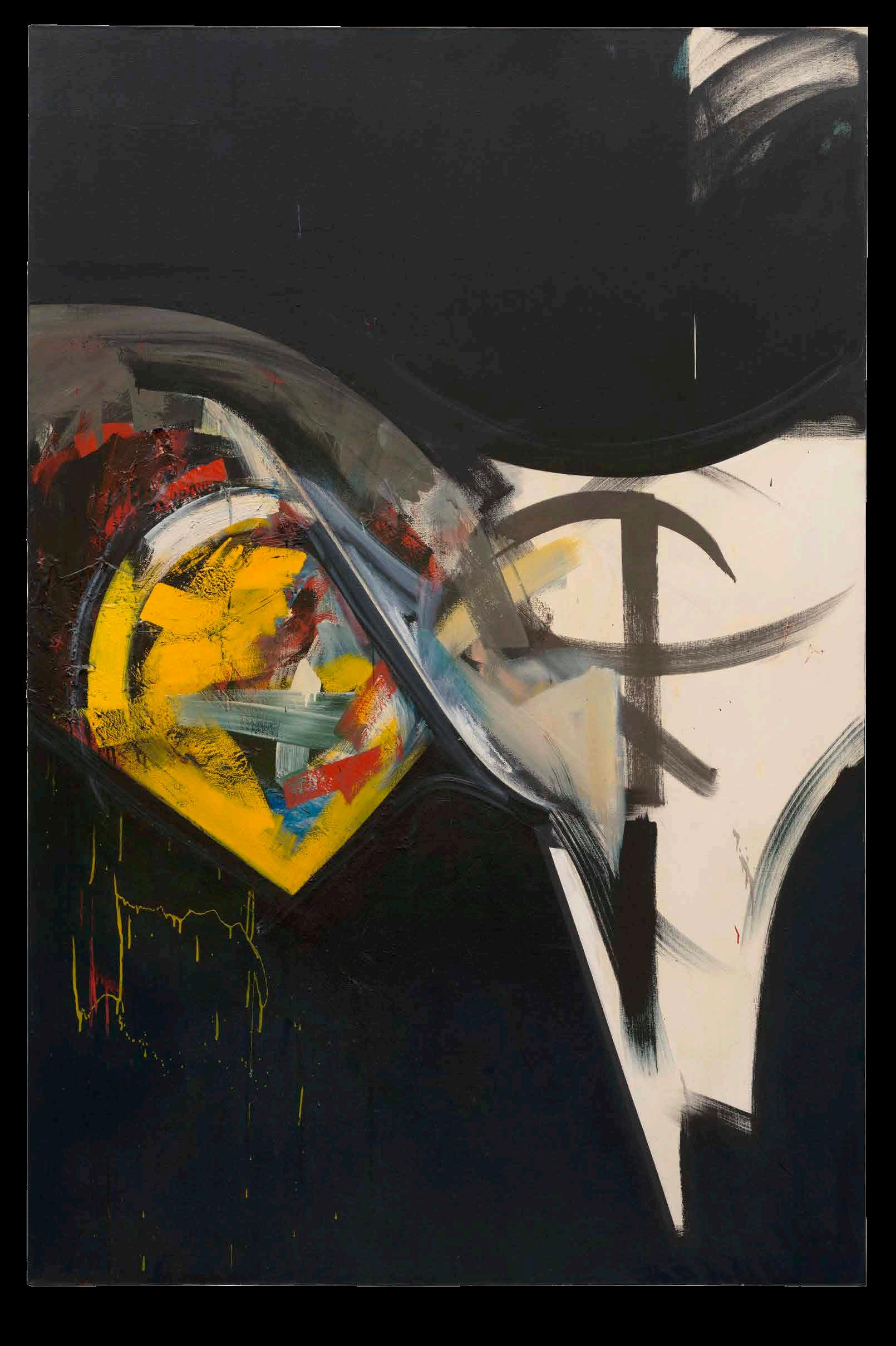

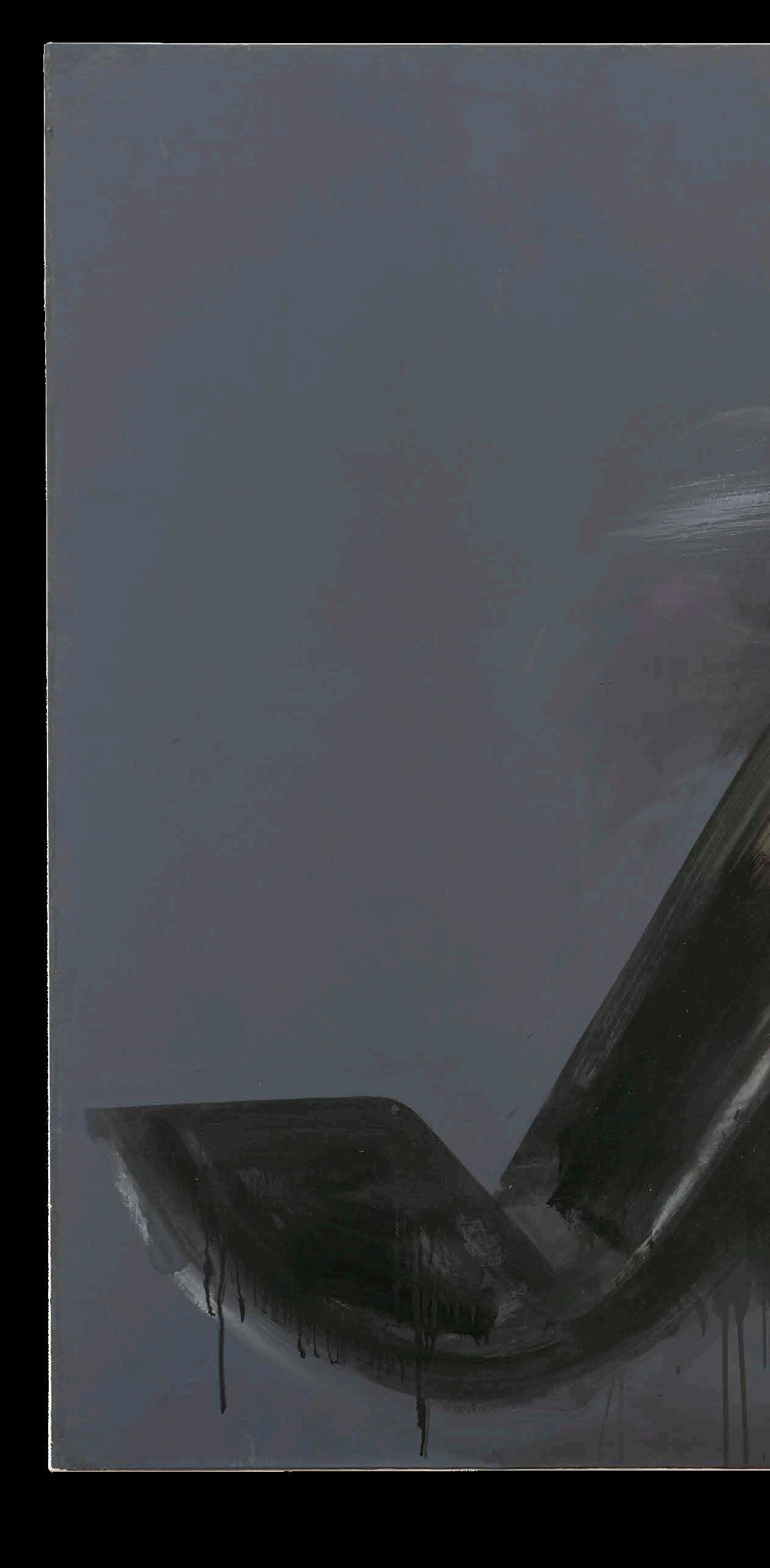

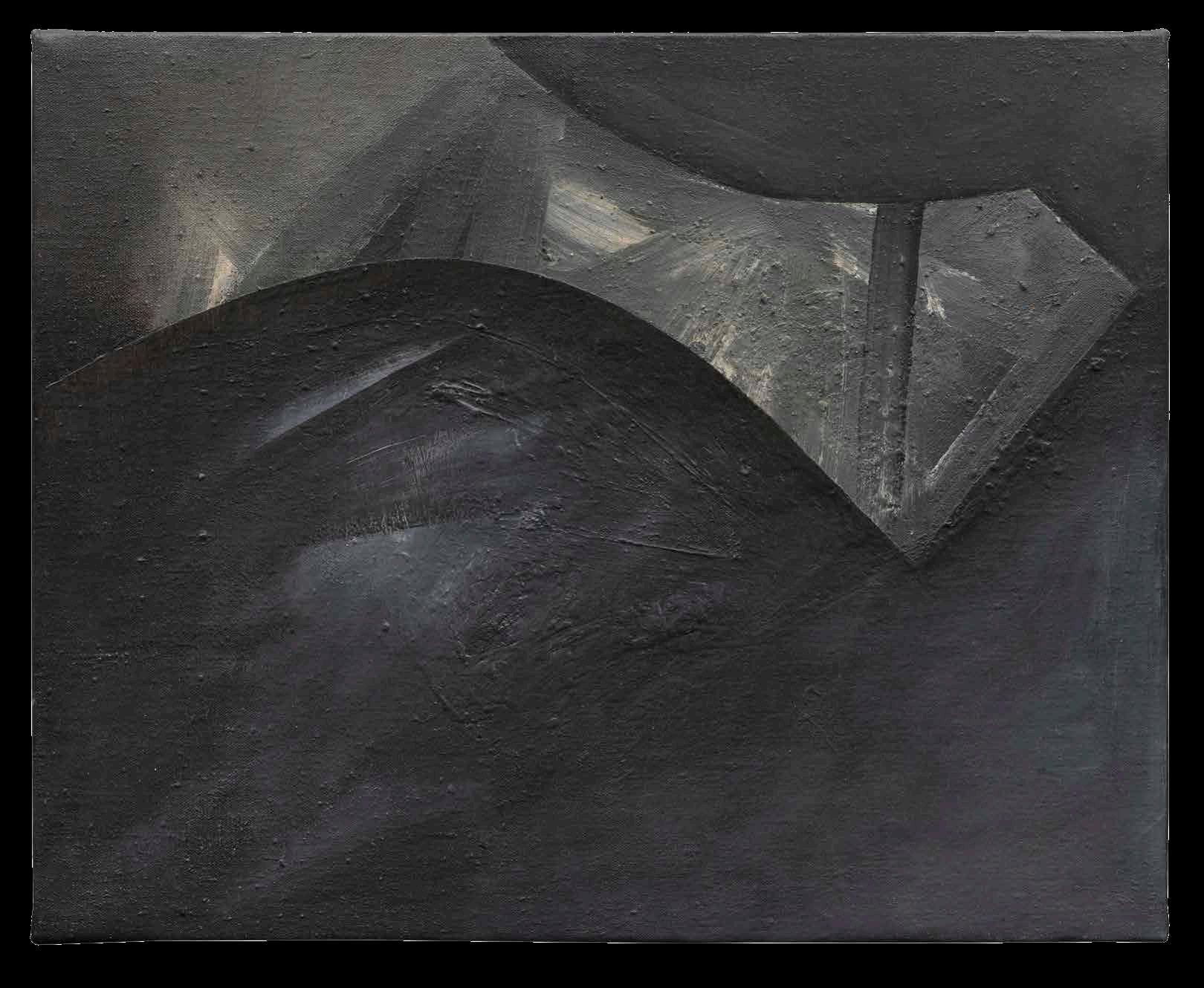

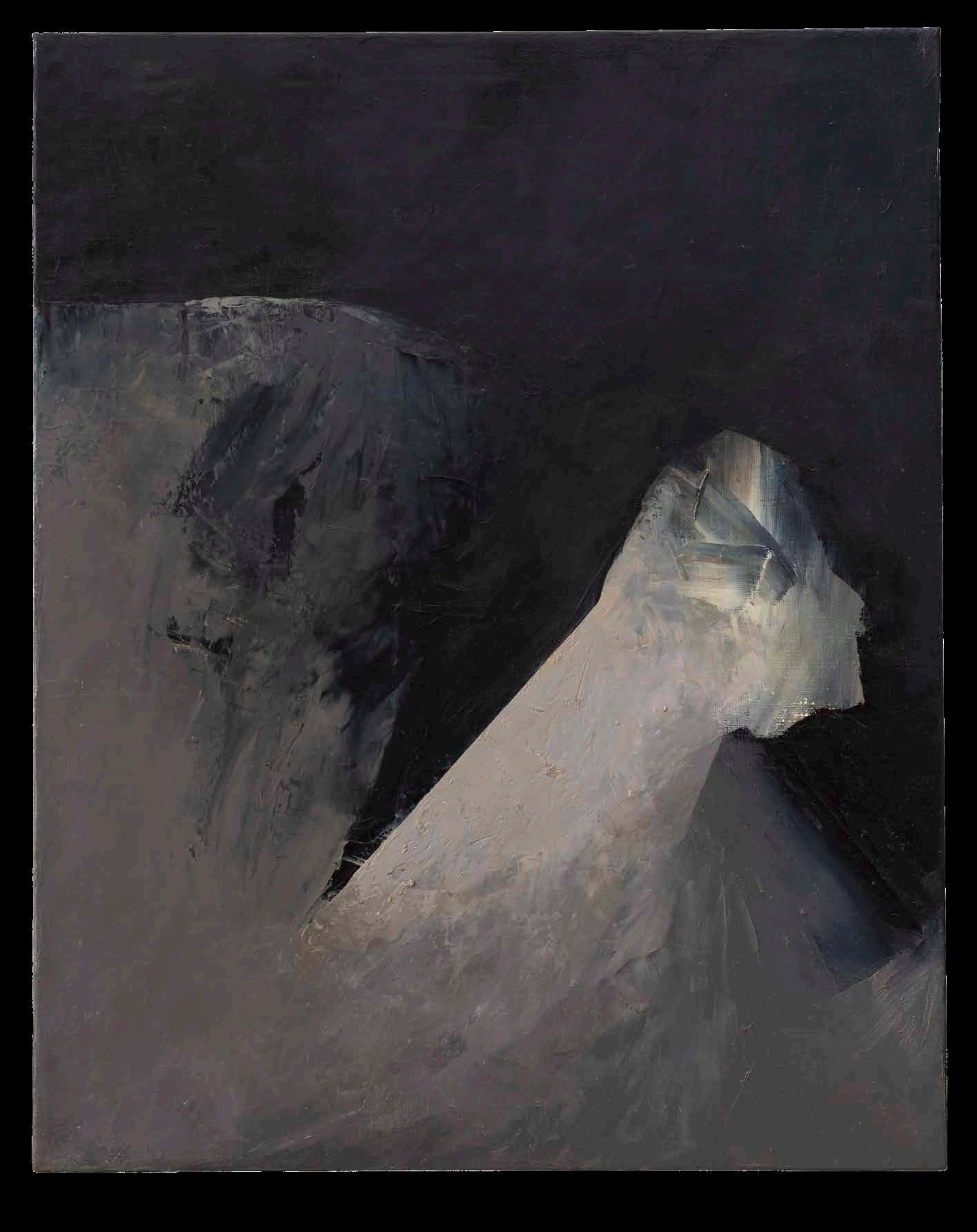

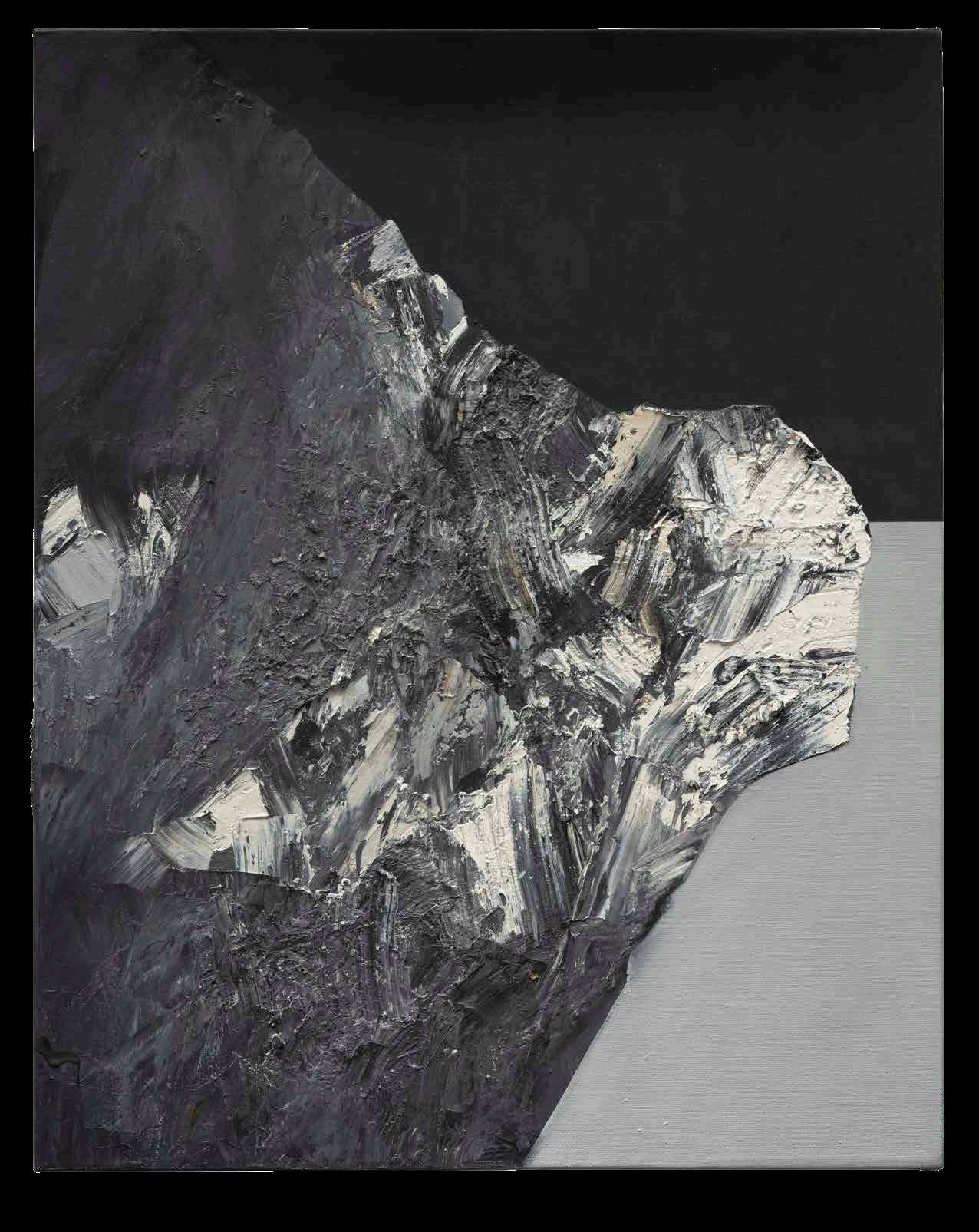

A painting called The Assignment, from 1983 (fig. 2; study, right), is emblematic of the era. It carries the mysterious clarity of turn of the century Theosophical watercolors, abstractions linked to particular emotional states like Upward Rush of Devotion or The Intention to Know. The central form is a boot-like “J,” which also resembles a goblet made of fabric, or a shirt sleeve as an urn. A dark, gray wind has blown the form straight into the frame. In fact, all central forms in the works on view explode or emerge from a uniform background, like garnets on a boulder. (Neatly, garnets — essentially a wide-variety of gemstone — are often found on rocks that transform under intense heat and pressure, but don’t melt. They don’t melt.) Depending on its valence, the title of the painting toggles between the casual and divinatory. Either way, the work plainly holds a belief in the power of painting as a site for honest seeing, and embodies what may be the bedrock ethos of DeFeo’s Delphic approach to art-making: catch it if you can.

In a 1984 interview DeFeo notes that once a viewer recognizes a subject in her work, “they lose sight of what I’m attempting to do; that is, portray the esthetic harmony

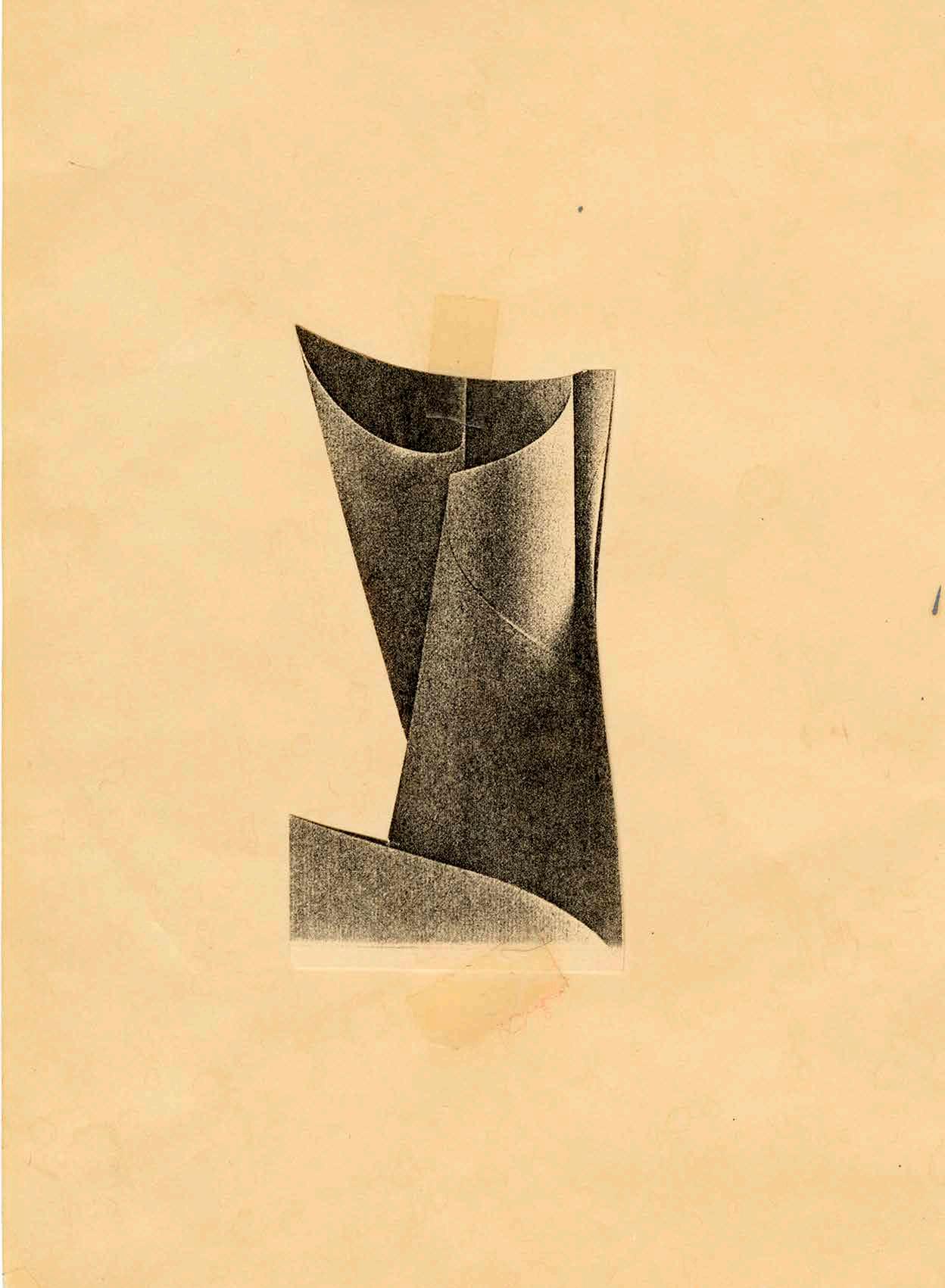

Jay DeFeo, Untitled , 1982 (detail ). Cut photocopy taped to paper, 81/2 × 11 inches (21.6 × 27.9 cm)

The cut photocopy, made from a Herman Miller advertisement in an architectural magazine, was the source for The Assignment

resulting from the uniting of the geometric and organic forms.” The thought appears in two parts: initially, she makes clear that identifying a recognizable thing in her work is off the mark. This is not an airplane. Beyond the semicolon is a one-sentence articulation of what she thinks she’s trying to do, and the noteworthy thing is that it’s rather bland in the face of what she’s actually doing. To unite the geometric — regular and precise — with the organic — irregular and varied — is worth a shot, but can it really be the defining characteristic of her work?

I live in San Francisco, but I’m staying at a friend’s apartment in the East Village this week. I’m half-surprised to see Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind on her bookshelf — its author, Shunryu Suzuki, was a founder of San Francisco’s Zen Center, which is about six blocks from my home. I’ve had the book for years, and whereas I’m a fairly determined person, I’ve yet to move past its introduction. I was flipping through last night, thinking of Jay. If a student sticks with meditation, Suzuki writes, “you will obtain a wonderful power. Before you attain it, it is something wonderful, but after you obtain it, it is nothing special.” Nothing special. Is this the “esthetic harmony” she’s talking about? He goes on, cementing the paradox of his thought: “[I]t is nothing. But yet it is not nothing. Do you understand?” I look back at DeFeo’s quote, quietly stunned by the tremendous implications of integrating the predictable and unpredictable across the arc of a life.

“I maintain a kind of consciousness of everything I’ve ever done while I’m engaged on a current work,” DeFeo said in 1978, and I get the sense she was always working, even as she slept, the gristmill of her mind breaking down Scientific American illustrations and the color of televised snakes. The title of this show comes from a small painting on view from 1989 (fig. 17), and The Jay DeFeo Foundation only recently learned it was borrowed from a poem written by her friend and former Fillmore Street neighbor, Michael McClure.

In other words, there is no airplane, but there is a sound. Where does it come from?

—Jordan Stein

Works in the Exhibition

1. Verdict No. 1, 1982. Oil with tape on canvas, 84 × 60 inches (213.4 × 152.4 cm)

2. The Assignment , 1983. Oil and charcoal on linen, 66 × 48 inches (167.6 × 121.9 cm)

3. Grey Profile , 1983. Oil and charcoal on paper mounted on canvas, 343/8 × 521/4 inches (87.3 × 132.7 cm)

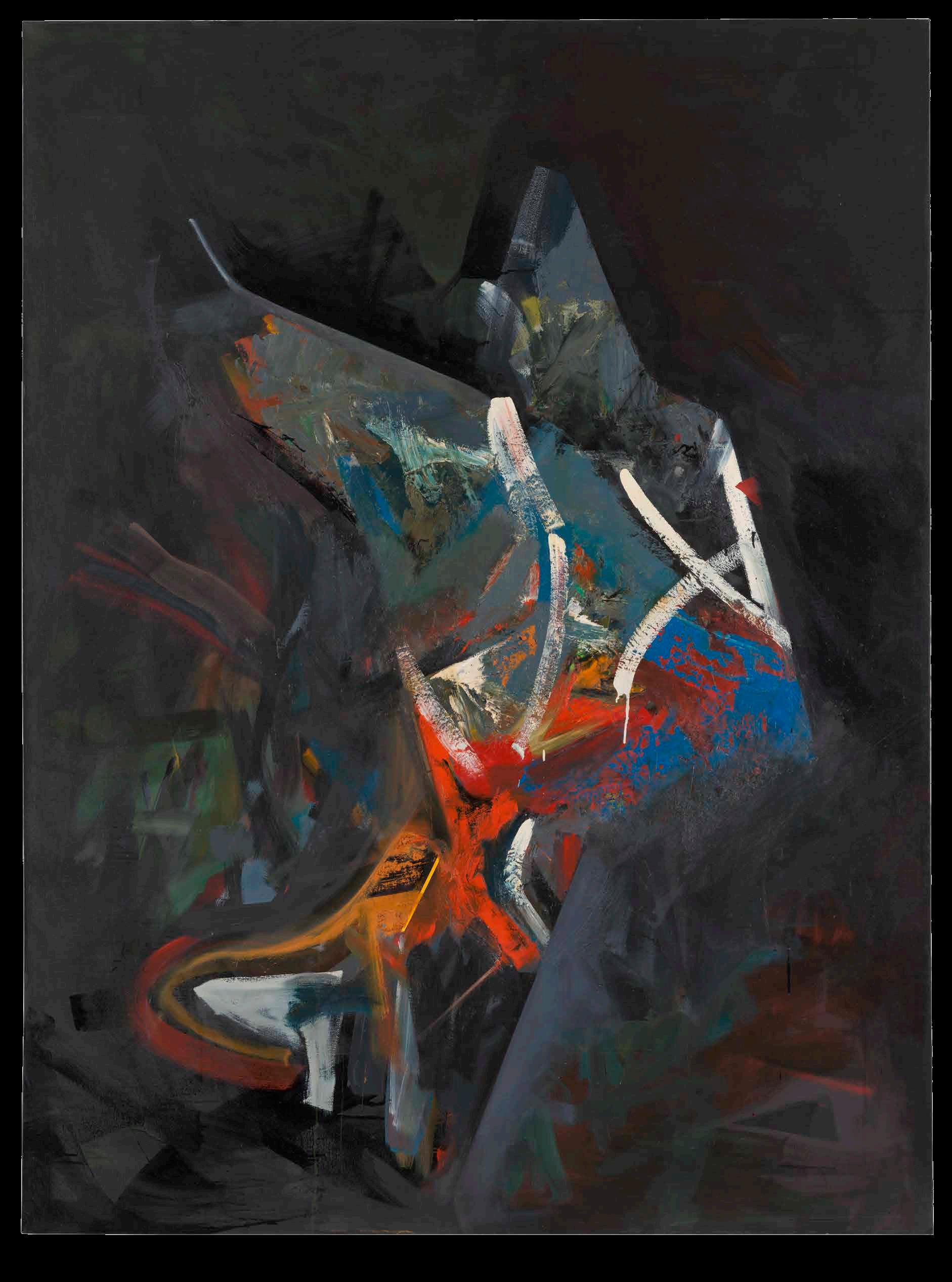

4. Hawk Moon No. 1, 1983–85. Oil on canvas, 84 × 60 inches (213.4 × 152.4 cm)

5. La Brea , 1984–85. Oil with tape on canvas, 96 × 72 inches (243.8 × 182.9 cm)

6. Geisha II , 1984 / 1987. Oil with tape on canvas, 90 × 601/8 inches (228.6 × 152.7 cm)

7. Bride , 1986. Oil with tape on paper mounted on canvas, 591/4 × 801/2 inches (150.5 × 204.5 cm)

8. Untitled ( Reclining Figure), 1986. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 593/16 × 805/8 inches (150.3 × 204.8 cm)

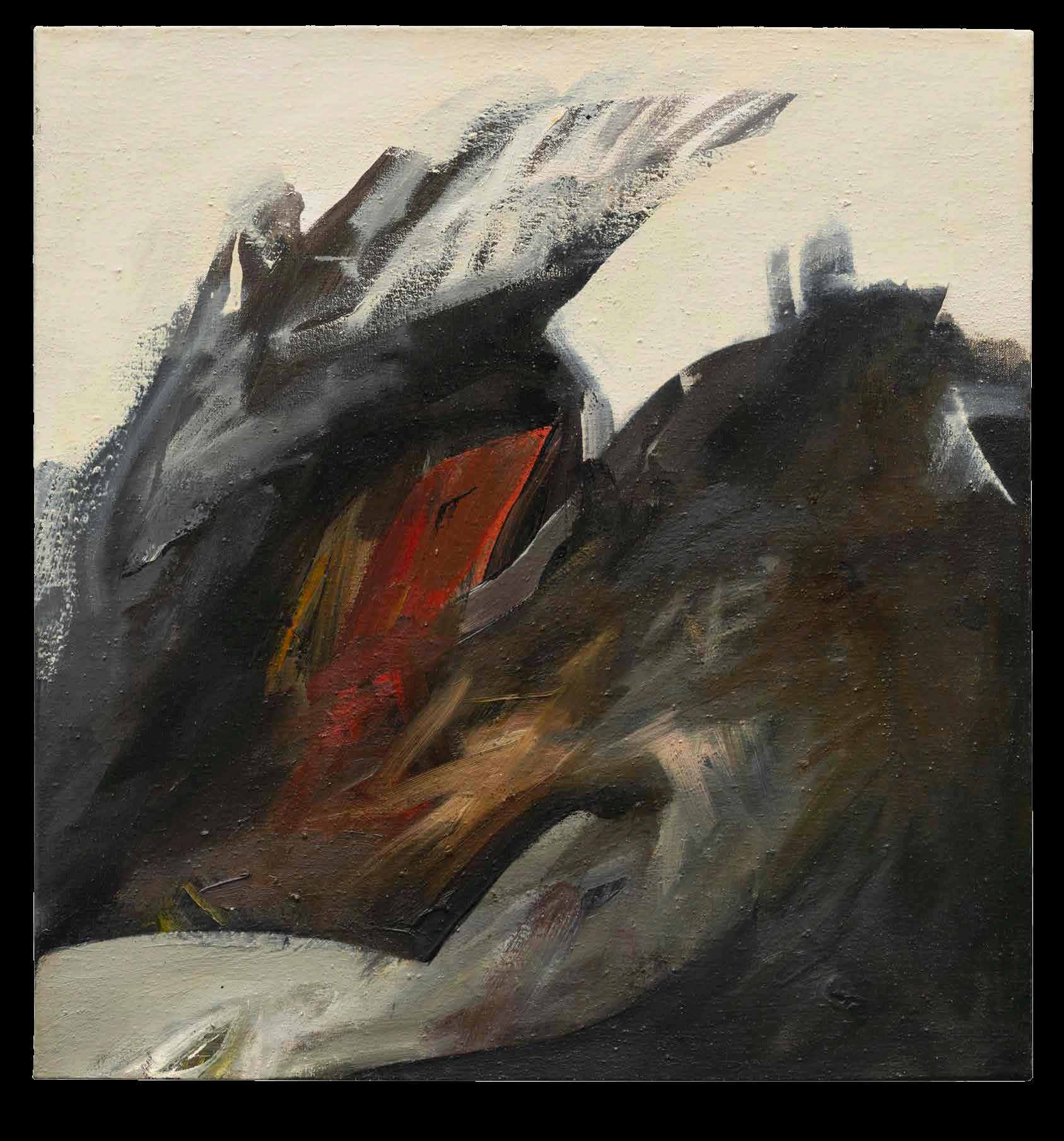

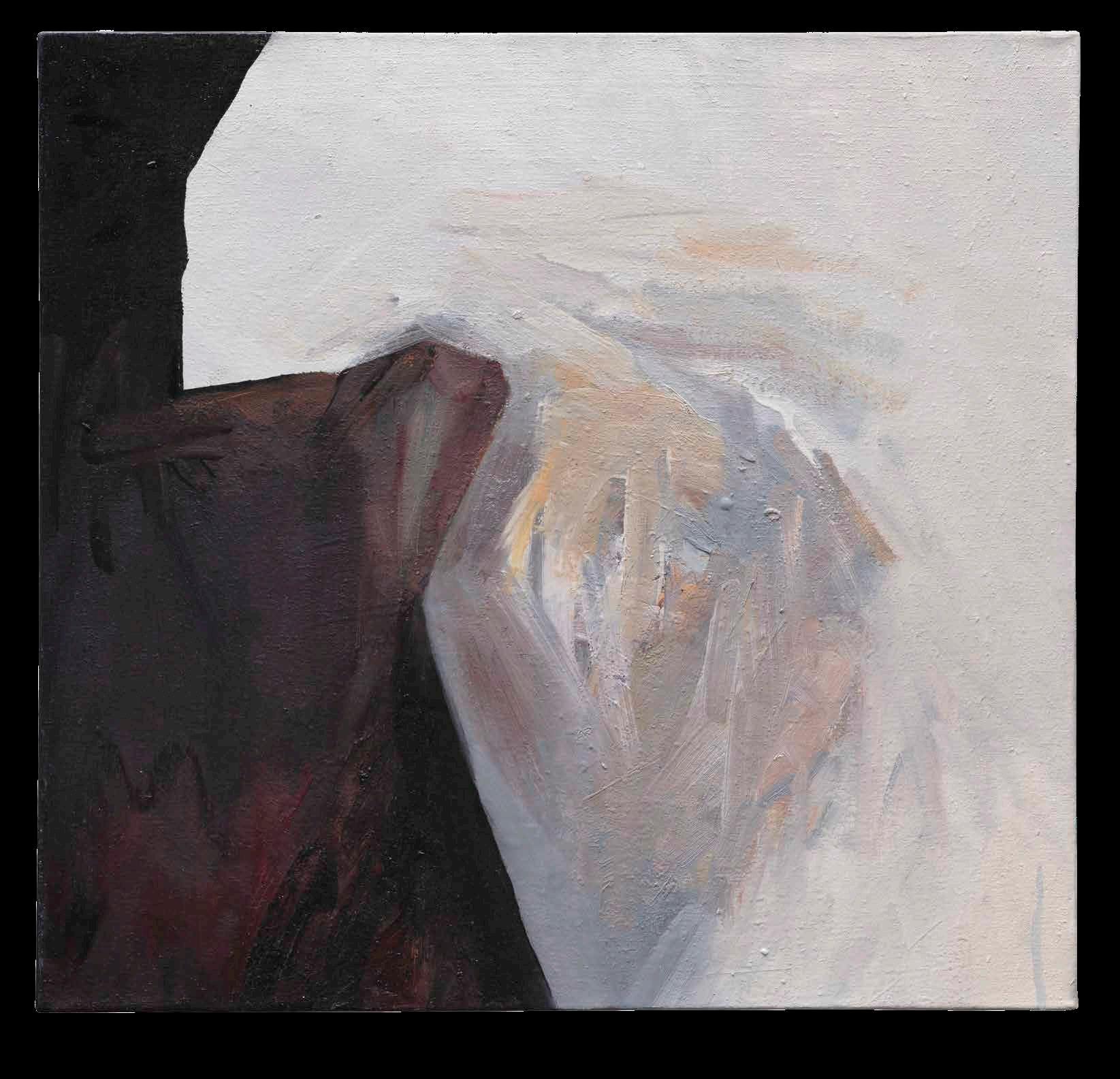

9. Alabama Hills No. 2 , 1986. Oil on linen, 12 × 15 inches (30.5 × 38.1 cm)

10. Alabama Hills No. 3 , 1986. Oil on linen, 121/4 × 15 inches (31.1 × 38.1 cm)

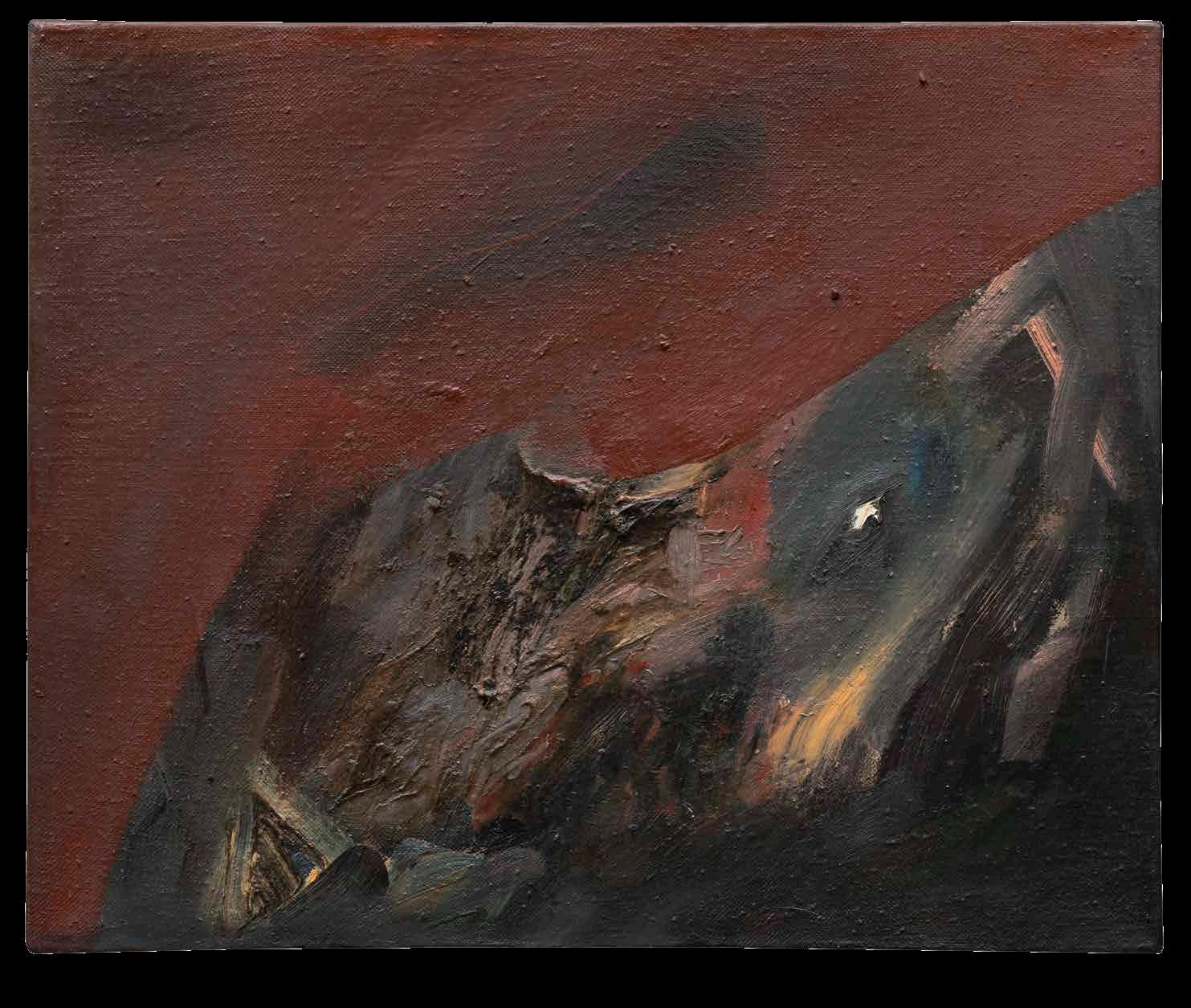

11. Alabama Hills No. 7: Jungle Sunset , 1986. Oil on linen, 10 × 121/4 inches (25.4 × 31.1 cm)

12. Alabama Hills No. 10 , 1986. Oil on linen, 20 × 19 inches (50.8 × 48.3 cm)

13. Alabama Hills No. 11, 1986. Oil on linen, 16 × 17 inches (40.6 × 43.2 cm)

14. Alabama Hills No. 15 , 1986. Oil with string on linen, 101/4 × 13 inches (26 × 33 cm)

15. Alabama Hills No. 20 , 1987. Oil on linen, 17 × 20 inches (43.2 × 50.8 cm)

16. Smile and Lie , 1989. Oil on linen, 20 × 16 inches (50.8 × 40.6 cm)

17. Garnets on the Boulder, 1989. Oil on linen, 16 × 12 inches (40.6 × 30.5 cm)

Jay DeFeo (1929–1989) made a rich body of highly original paintings, drawings, collages and photographic works, expressed through the broad parameters of unorthodox materials and a personal “visual vocabulary” that referenced both the geometric and the organic.

Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, DeFeo grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. She received a bachelor’s degree in 1950 and a master’s degree in 1951 in studio art from the University of California, Berkeley. Through a post-graduate fellowship, DeFeo spent a seminal fifteen months in Europe absorbing prehistoric and classical art, architecture, and post-war abstraction.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, DeFeo became a central figure within the vibrant community of San Francisco artists and poets. In 1959, she received national recognition when her work was featured in Sixteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. She began working on The Rose , “an idea that had a center to it,” completing the painting almost eight years later, in 1966. A monumental artwork created with so much paint that she called it “a marriage between painting and sculpture,” The Rose was first exhibited in 1969 at the Pasadena Art Museum and is now a key work in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In 1966, DeFeo moved to Marin County, north of San Francisco. There, through the 1970s, she became deeply involved with photography and photocopy work as well as inventive applications of materials new to her, including acrylic paint. Often her object sources in that period were domestic oddities from which she created series of works that transcended the images from which they were derived. After accepting a position teaching painting at Mills College, DeFeo moved to a large studio in Oakland, California, in 1981. She returned to working with oil paint for the first time since completing The Rose , creating large and small glowing canvases as well as a range of works on paper. These works reflect her exacting exploration of shape, form, and texture, while still inviting chance intervention. DeFeo was diagnosed with lung cancer in the spring of 1988 but continued to work prolifically until the last months of her life. She died on November 11, 1989, at the age of 60.

Garnets on the Boulder: Jay DeFeo Paintings of the 1980s 2025

Published in the U.S.A. by PJC, New York, on the occasion of the exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, October 30 – December 13, 2025

Artworks © 2025 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Publication © Paula Cooper Gallery, 534 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10011 www.paulacoopergallery.com

isbn: 979-8-218-81076-4

Front cover: Geisha II , 1984 / 1987 (detail )

Jordan Stein would like to thank The Jay DeFeo Foundation and Paula Cooper Gallery.

Special thanks to: Leah Levy, Carly Sitko, and Dawn Troy of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Jordan Stein, and Daisy Charles.

Artwork photography by Ben Blackwell

Page 2: Jay DeFeo in her studio in Oakland, California, 1986 © 2025 M. Lee Fatherree

Previous page: Photograph of Jay DeFeo, 1985 © 2025 James Kelly Estate

Designed by Tony Morgan/Step Graphics

Printed in an edition of 500 copies by Meridian Printing

Sources of Jay DeFeo quotes in essay: Jay DeFeo, journal entry, August 13, 1984. Archive of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.

Jay DeFeo, letter to James Kelly, c. March 10, 1982. Archive of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.

Original in the Jay DeFeo Papers at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Jay DeFeo, quoted in “The Prize Rebirth of an Abstractionist” by Al Morch, San Francisco Examiner, April 23, 1984.

Jay DeFeo, letter to Henry Hopkins, Director, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, June 21, 1978.

Archive of The Jay DeFeo Foundation, Berkeley, CA.