PSBA SCHOOL LEADER

fall 2025 Informing and engaging Pennsylvania’s public school leaders

fall 2025 Informing and engaging Pennsylvania’s public school leaders

fall 2025 Informing and engaging Pennsylvania’s public school leaders

BY KENDAL KLOIBER

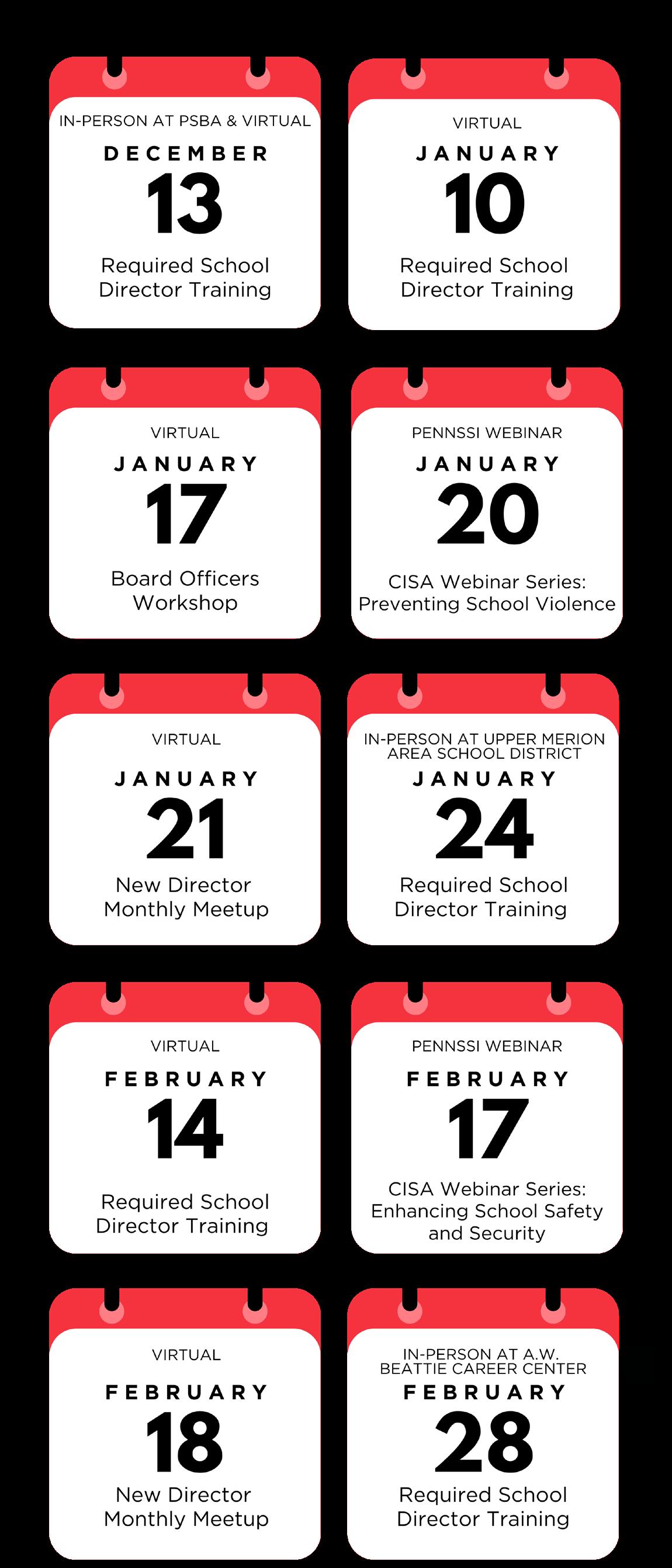

When the Franklin Regional School District began discussing artificial intelligence, the conversation could have gone in several directions. As district leadership talked through the possibilities, one priority quickly rose to the top: protecting student data. That focus mirrors a national concern.

BY JIM PATERSON

Experts say that one of the critical things for superintendents as they onboard to a new job is developing multiple new relationships – and school board directors are a priority and great source for other connections.

BY ANGELA CONIGLIARO

Across Pennsylvania, 4,500 school board directors volunteer their time and talents to serve students in the Keystone State. While their role may not always be visible to the public, board secretaries are instrumental in ensuring smooth operations, accurate documentation and well-run meetings.

BY SEAN RUCK

Ashlie Crosson is a lesson in firsts. Years before she became the first National Teacher of the Year from the commonwealth, where she was also named State Teacher of the Year, she became a first-generation college grad, earning a bachelor’s degree in English and language arts.

BY SARAH ERDMAN

Q: What motivated you to become involved in board service?

I have always beenpassionate about serving my community, particularly in the field of education. When my daughter entered high school, I saw an opportunity to make a positiveimpact by running for a position on the school board.

BY AMANDA COOK

Amanda Cook, board president at the Susquehanna Community School District, shares how her board fosters positive collaboration with the superintendent and discusses some new district projects.

PSBA President Allison Mathis discusses post-election board collaboration and PSBA CEO Nathan Mains discusses the hallmarks of impactful leadership.

Amanda Cook, board president at the Susquehanna Community School District, shares how her board fosters positive collaboration with the superintendent and discusses some new district projects.

How can we clarify the role of the school board to help prevent misconceptions among the public?

Johnsonburg Area School District’s “Lenny’s” programs support learning by meeting the needs of the whole student.

Get answers to frequently asked questions about board governance, from PSBA’s available resources.

One great moment in the life of our public schools.

Sen. Nick Miller shares the educational issues most important to him and his thoughts on public school advocacy and charter school reform legislation.

Learn tips for how to safeguard your schools against cybersecurity threats.

Take a look at public schools’ average expenditures and revenue sources for the 2023-24 school year.

Review the Right-to-Know Law risks of social media for school directors.

GOVERNING BOARD

PRESIDENT

Allison Mathis, North Hills SD

PRESIDENT-ELECT

Sabrina Backer, Franklin Area SD

VICE PRESIDENT

Matt Vannoy, Sharon City SD

TREASURER

Dr. Karen Beck Pooley, Bethlehem Area SD

IMMEDIATE PAST-PRESIDENT Mike Gossert, Cumberland Valley SD

STAFF

Nathan G. Mains Chief Executive Officer nathan.mains@psba.org

Jackie Inouye Editor jackie.inouye@psba.org

Mackenzie Christ Editor mackenzie.christ@psba.org

Erika Houser Senior Design Manager erika.houser@psba.org

www.psba.org

(717) 506-2450 (800) 932-0588 Fax: (717) 506-2451

PSBA SCHOOL LEADER BULLETIN: (ISSN 01623559) is published four times a year by the Pennsylvania School Boards Association, 400 Bent Creek Blvd, Mechanicsburg, PA 17050-1873. Tel: (717) 506-2450. Periodicals postage paid at Mechanicsburg, PA and additional mailing locations. Subscriptions: $60 per year (members), $150 per year (nonmembers). Postmaster: Send address changes to PSBA Bulletin, 400 Bent Creek Blvd., Mechanicsburg, PA 17050-1873. EDITORIAL AND ADVERTISING

POLICY: The granting of PSBA Partners and the acceptance of advertising in this publication do not necessarily constitute an endorsement by the Pennsylvania School Boards Association for products and services offered by the advertisers. Official positions and services endorsed by PSBA will be clearly stated and noted in this publication. Opinions by authors do not necessarily reflect positions of PSBA. © 2025 Pennsylvania School Boards Association.

By Allison Mathis, president

Phew! We made it through the 2025 election cycle. School board elections bring energy, opinions and, sometimes, tension. Candidates campaign, communities make their voices heard; often, new leadership takes shape. But when the ballots are counted and the yard signs come down, the real work begins.

When I first joined my local board, I thought everyone would be excited about the energy, expertise and fresh perspective I brought. I had ideas, a parental point of view and a real desire to make a difference. (Spoiler alert: not everyone was excited about me.) I quickly learned that school board service isn’t just about what you think you bring — it’s also about how you take the time to build trust and relationships, especially after a tough election season.

Since joining the board, I’ve been through several election cycles. I’ve watched them become increasingly polarized. I’ve seen negative rhetoric, usually online. But I’ve also seen what happens when people choose to work together despite their differences. After one particularly difficult election, I made it a point to help re-center our board by encouraging open conversations, listening more than speaking, and reminding us all to focus on the work, not the wounds. Four years go by fast. You don’t want to waste that time. Something as simple as inviting a new school director out for coffee can go a long way. It sets a tone of collaboration and shows you’re on the same team now. My advice is to get any awkwardness out of the way early, preferably prior to the reorganization meeting.

Of course, there will still be hard moments. About three months into my first term, our board began debating the formation of a school police force. It was a sensitive, divisive issue in our community. But serving on a

board means staying at the table — even when it’s hard. And taking time right after an election to establish relationships with new school directors makes staying at that table a little easier. Elections shape boards, but they shouldn’t define them. Let’s enter 2026 leading with integrity, learning from one another and keeping students at the center of every decision.

By Nathan Mains, chief executive officer

As fall unfolds across Pennsylvania, school boards are already looking ahead to a pivotal moment: December’s reorganization meetings. These gatherings mark a time of renewal — when newly elected directors take their seats, returning members reaffirm their commitment, and districts prepare for the year ahead.

In this issue of the School Leader Bulletin, we explore the many ways leadership takes shape in our schools. From the onboarding of new superintendents to the essential work of board secretaries, we see how trust, preparation and collaboration form the backbone of effective governance.

We celebrate Ashlie Crosson, Pennsylvania’s first National Teacher of the Year, whose story reminds us that leadership begins in the classroom. We also examine how districts are navigating the promise and complexity of artificial intelligence — balancing innovation with the critical responsibility of protecting student data.

Each of these features reflects a core truth: leadership is not a title, but a practice. It’s built through relationships, sustained by transparency, and strengthened by shared purpose.

At PSBA, we’re proud to support school boards through every season of change.

As you prepare for reorganization and the new year, we hope this issue offers insight, encouragement and practical tools to help you lead with confidence.

By Jackie Inouye, director of communications

As your school board prepares to welcome new members and complete the reorganization process, it’s a natural time to think about team building. What opportunities do you have to help new directors adjust to their role while encouraging fresh ideas? From what foundation is your team growing? Review the Principles for Governance and Leadership for a framework that guides board to greater effectiveness.

Boards supporting a new superintendent face unique opportunities and challenges. On page 22, see how one board navigated the transition successfully and gain insights from the administrator perspective on what superintendents need most during this time.

The Team of 10 is the core governing body – but what about adjacent roles, such as the recording secretary or school solicitor? Understanding how these individuals interact with the board and what responsibilities they have can help your board work more efficiently. This issue kicks off a new series of features highlighting these key positions.

On page 26, go behind the scenes with two district employees who are leaders in PSBA’s School Board Secretaries Forum. Learn about their many tasks and how they impact the board’s performance. In the following issue, we’ll offer some tips on working effectively with the school solicitor and highlight a new PSBA guide on the topic. If there is a supporting role that you’d like to learn more about, contact me at jackie.inouye@psba.org.

For the latest news, click on the Stay Updated tab on myPSBA, and check out the Resource Library under the Gain Knowledge tab.

Now in its 41st year, the Honor Roll recognizes school directors with certificates and other awards at five-year service intervals, starting at five years and continuing every five years thereafter. See the complete Honor Roll list for 2025 now on myPSBA.

School directors dedicate their time and energy to strengthening public education year-round. January is designated as a time to honor them and highlight the valuable service they provide to their schools and communities. Find resources to help your schools celebrate on myPSBA, including sample press releases and posts, customizable certificates and more.

Celebrate school boards, school leaders and teachers who are going the extra mile for their students and public education! Video interviews with all PA Education Innovation Award winners and the William Howard Day Award recipient are available now at psba.institute.

Members of the 2026 Governing Board, PSBA Sectional Advisors and other elected officers were announced at the Delegate Assembly on October 21 and in the morning newsletters. Photos and bios for Governing Board members will be available in the special insert of the Bulletin coming in February.

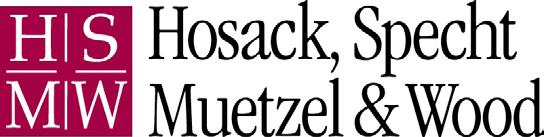

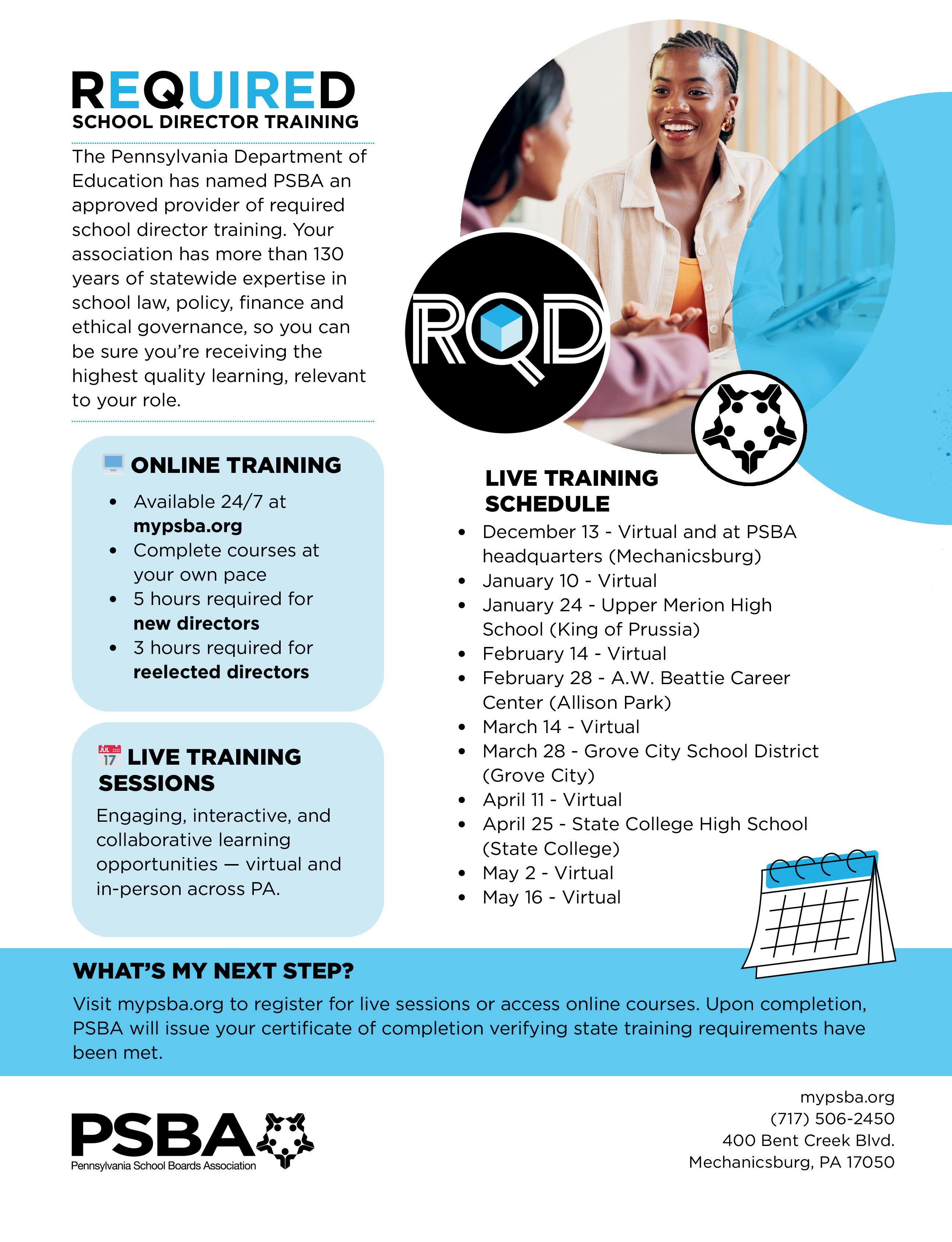

According to the PA Public School Code, all newly elected/appointed school directors must complete five hours of training during their first term of office. Reelected/ appointed school directors must complete three hours of advanced training. PSBA is a PDE-approved provider of the required training and offers in-person, live virtual and online asynchronous options. Learn more at myPSBA.org/rqd.

PSBA’s Essentials of School Board Service: A Guide to Effective Leadership provides a quick reference on the basics of board service, including a glossary of common education terms and a list of frequently used acronyms. Essentials of Parliamentary Procedure: A Guide for Pennsylvania School Boards helps school directors fulfill their role in board meetings confidently and effectively. Essentials of School Board Secretary Service assists those navigating this key position within the district. Plus, we’ve just added Essentials of School Board Committees to support Pennsylvania school boards in establishing and maintaining effective committee structures. Access these new and newly updated guides in the Professional Development section of the myPSBA Resource Library.

The Great PA Schools Learning Lab is bringing hands-on learning for public school district leaders, administration and students to schools statewide! See greatpaschools.com for details on how to host the mobile lab at your school entity.

In thanks for all our members do to educate students, PSBA donated a copy of Remarkably You by Pat Zietlow Miller to all member school districts this fall. The beautifully illustrated hardcover book celebrates individuality and the importance of sharing our unique talents with others. Also, newly elected school directors should check their mailboxes for a PSBA welcome packet coming soon with resources to support them in their new role.

Hundreds of school leaders gathered in the Poconos for learning and networking at the 2025 PASA-PSBA School Leadership Conference. Get a recap, including drawing winners and recipients of the PA Education Innovation Awards on the conference website, paschoolleaders.org, and mark your calendar for next year’s event on October 18-20, 2026!

PSBA and the PA School Board Solicitors Association (PSBSA) held a successful education and networking event for solicitors in Bedford Springs this summer. Attorneys should mark their calendar next year’s symposium on July 16-17, 2026, back at the newly renovated Nittany Lion Inn.

PSBA has launched a new 30-minute video show! Airing on Pennsylvania Cable Network (PCN), the first episode on September 24 took a multifaceted look at school safety and security, including interviews with legislators, school leaders and local law enforcement. New episodes are released monthly and are also available on PSBA’s YouTube channel.

PSBA has released an updated Year of Learning guide – a comprehensive catalog of events and webinars available throughout 2025-27. Access it at https://edin.fo/yol2527.

Prepare now for your board’s organization meeting during the first week of December. For an overview of the basics, choose the Annual Board Organization microcourse from the myPSBA Store.

Or visit the myPSBA Resource Library to access our new three-page School Board Organization Guide and Chapter 5 of Essentials of School Board Secretary Service, which includes procedural steps and a sample script.

As your board welcomes newly elected school directors this fall, encourage them to attend New Director Monthly Meetups in the new year. Offered each month from January to June, directors can connect with colleagues, learn about the support PSBA provides to our members and ask questions of veteran school board directors during these hour-long virtual meetings designed to foster new board directors’ success. Learn more on myPSBA.

Additional cohorts of the Foundational AI for School Leaders certificate program offered by the PSBA Institute and Millersville University are now open. Gain the tools you need to make smart decisions on this key emerging technology. For details and registration dates, visit psba.institute.

Join us for the winter AI Symposium on December 11 to learn more about how artificial intelligence is transforming teaching, learning and institutional operations. Register on psba.institute.

The first Bulletin issue of 2026 will focus on newly elected school directors, with features on board basics and advice from experienced directors. What advice helped you most as a new member of the board? What do you wish someone had shared with you about board service? What resources have been helpful to you? Please send your thoughts (about 150 words) to jackie.inouye@psba.org for consideration to be included in this issue.

PSBA recently received three APEX Awards – an Excellence Award for the Winter 2025 Bulletin and the microcourses/microcredentials on myPSBA plus a Grand Award for PSBA’s Advocacy Guide! We’re proud to continue our tradition of providing resources of the highest quality to our members.

Jenna Behringer is PSBA’s newest policy coordinator. With a bachelor’s degree in public policy from the Penn State School of Public Affairs, Jenna brings a dynamic background spanning the environmental nonprofit sector, information technology and the music industry. In her spare time, she loves kayaking, hiking, volunteering, traveling, and performing and enjoying live music.

Rachel Gedid Peternith recently joined PSBA as the senior director of legal services. Before joining PSBA, Rachel served as a senior attorney in the Office of the General Counsel at the U.S. Department of Education and clerked for the PA Supreme Court in the office of the Honorable Justice Thomas G. Saylor. She holds bachelor’s degrees in both economics and interdisciplinary studies from The American University and a juris doctorate from The William & Mary School of Law in Virginia. A South-Central PA native, Rachel is thrilled to be back in her home state with her husband, two sons and dog.

Crawford Gingrich brings nearly 30 years of experience in law enforcement, military service and security operations to his role as director of school safety for the Pennsylvania School Safety Institute (PennSSI). He has served in key positions

with the Hampden Township Police Department and is a U.S. Army veteran. He holds degrees in cybersecurity analytics and operations and criminal justice from Penn State University (PSU). He is a season ticket holder for PSU football and loves to travel the globe, cook, golf and scuba dive in his free time.

Crystal Roesner, senior accounting manager at PSBA, is a certified public accountant with 30 years of experience in the field and a bachelor’s degree in accounting from Bloomsburg University. Outside of work, Crystal volunteers in the finance office of the Silver Spring Ambulance and Rescue Association. She enjoys spending time with family, cooking, and running marathons – she has completed more than 50!

Michelle Zettlemoyer, PSBA’s new director of services, is focused on advancing the development and delivery of innovative service solutions for PA school districts, including ConnectED PA and PSBA Health Services. Michelle brings more than 30 years of experience in human resources, over 20 of which were in public education as director of human resources at Cumberland Valley School District from 2003 to 2025. She holds a bachelor’s degree in personnel administration from Shippensburg University and a master’s degree in business administration from Kutztown University. Outside of work, she enjoys spending time with family and friends and renovating an older home in Delaware.

Encourage your outstanding students to apply now for the PSBA Trust's 2026 Student Leader Scholarships, which provide a one-time award of up to $2,500 or $5,000 to graduating seniors from PSBA member districts who have demonstrated ongoing leadership and meet the criteria for one of four available scholarship categories. Applications for the 2026 scholarships are due by March 13, 2026. Visit psbatrust.org to apply.

Opened in 1836, Central High School in the School District of Philadelphia was Pennsylvania's first high school. Construction followed the signing of the Free School Act of 1834, which established school districts and school boards. It is the second oldest continuously operating public high school in the U.S.

Schedule

Ensure

By Nir Eyal

Published by BenBella Books

Reviewed by Jessica Portz

Take a moment and listen to the surrounding sounds. Distraction is all around — notifications from cell phones, alerts from watches, someone talking in the distance and dings from computers are all encompassing. In Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life, author Nir Eyal offers solutions and strategies to stay focused in this noisy world. Though the book is more focused on personal productivity and corporate environments, by utilizing and following the guidance set forth in Indistractable, school board directors and administrators can lead with purpose, clarity and focus while improving decision-making skills.

Eyal explains that there are two types of distractions: internal and external. To lead an “indistractable” life, people must first learn to notice their internal triggers before they can address the distractions they create. Internal triggers are tied to uncomfortable emotional states, such as boredom, negativity bias, stress, anxiety or rumination, to name a few. What kind of discomfort comes before distraction occurs? Write down that trigger and explore it with curiosity and self-compassion. During meetings, school board directors can work on recognizing these impulses in order to avoid distractions like checking emails, pushing irrelevant issues or speaking over colleagues, and establish new norms that reduce interruptions.

While internal triggers can be more difficult to place, external triggers are easier to see and hear. The best thing to do is “hack” back those external triggers. With the technological advances of today, the same devices that are set to be a distraction can be manipulated to eliminate some of those triggers. Ask yourself: Is this external trigger serving me, or am I serving it? This will

help separate the useful triggers from the unhelpful ones.

School board directors’ time is limited, so it is important to make the most of it. Eyal introduces the concept of “timeboxing” – deciding what to do and when to do it –because as Eyal states, “If we don’t plan our days, someone else will.” This can be transformative for volunteers because meetings, reading agendas, attending events and reviewing important board documents can all be timeboxed to ensure that they are given the proper attention. Adequate and intentional time management can help prevent burnout and allow school leaders to be more present and effective in the boardroom.

Indistractable emphasizes precommitments, stating that they “are powerful because they cement our intentions when we’re clearheaded and make us less likely to act against our best interest later.” Precommitments can be used for accountability purposes. School board directors can set public goals to show transparency. Or, they may implement a self-identity pact to promise to be a focused, thoughtful, student-centered and committed leader.

Everyone has the power to be indistractable. By adopting the principles set forth by Eyal, school board directors will have the tools to lead more effectively, master internal triggers, gain traction of their time and honor precommitments. This means they can focus on the things that truly matter and cultivate an educational environment where students thrive. In a role where each decision helps shape a child’s future, being indistractable is not just a personal advantage, but a professional necessity.

“Labeling yourself as having poor selfcontrol actually leads to less self-control. Rather than telling ourselves we failed because we're somehow deficient, we should offer self-compassion by speaking to ourself with kindness when we experience setbacks.”

Recent highlights and happenings in public education.

PA received a “Meets Requirements” determination from the U.S. Department of Education, the highest level that the federal government awards to states under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Fox Chapel Area School District

Superintendent Dr. Mary Catherine Reljac has been named the recipient of the first-ever Reflective Leadership Award from Leading Now, a nationwide organization that supports superintendents.

Tony Cattani, principal of Lenape High School in Medford, NJ, was named National High School Principal of the Year by the National Association of Secondary School Principals.

The White House initiated the Presidential AI Challenge inviting students and educators to submit entries that use artificial intelligence (AI) to address community challenges or focus on creative approaches to teaching or using AI in K-12 learning.

Elyse Minder, a math teacher at J.P. McCaskey High School in the School District of Lancaster, was named a finalist for the federal Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching.

Over half of the states have passed legislation restricting the use of cellphones by K-12 students during school hours.

PIAA passed a measure allowing students at faith-based schools to participate in sports in their home districts if the school they attend does not offer those same sports.

In the Penncrest School District v. Thomas Cagle decision, the PA Supreme Court agreed with PSBA’s position — joined by PSAB (boroughs) and PSATS (township supervisors) — that determining whether a school board director’s personal social media posts are public records under the Right-to-Know Law requires a fact-sensitive analysis.

PA budget impasse stretched into the fall, causing financial concerns for many school districts.

School bus driver shortages continued to impact schools at the state and national level.

OpenAI, creator of ChatGPT, unveiled a new “study mode” feature designed to guide users through the process of finding answers, rather than simply giving users the answers.

The White House Task Force on AI Education, comprised of government officials and ed tech leaders, met for the first time.

More than a quarter of respondents of an annual survey conducted by State Educational Technology Directors’ Association said AI was their most pressing issue.

A study by the PennEnvironment Research & Policy Center suggested Pennsylvania schools could reap major financial and environmental benefits by adopting solar power.

Recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results showed grade 8 scores fell four points since 2019, while grade 12 math and reading scores dropped three points in the same period.

A RAND Corp. report estimated that about 22% of students across the U.S. were chronically absent in 2024-25.

A survey by cybersecurity company Sophos suggested that K-12 schools had improved in responding to ransomware attacks, with 50% of K-12 schools globally reporting they had recovered from attacks within a week, up from 30% in 2024.

Streamline

Powered by

It is time to take your superintendent evaluation to the next level! An effective performance evaluation helps drive school improvement and student achievement, develops a positive relationship between the board and the superintendent, demonstrates district accomplishments, and sets annual priorities. The evaluation process is a cooperative effort — ongoing and dynamic.

Visit Board Services under the Our Services tab on myPSBA to learn more.

BY KENDAL KLOIBER

“The more I dug into the exposure that schools have, the more imperative it became to act,” says Eshelman Ramey. “Whether it’s through formal policy, raising awareness or building safeguards, privacy has to be central.”

When the Franklin Regional School District began discussing artificial intelligence, the conversation could have gone in several directions. Like many districts, some voices worried about the risks: loss of creativity, academic dishonesty or simply moving too fast with a tool few fully understood. Others saw opportunity – a chance to prepare students for a world where AI will be embedded in everyday life.

But as Superintendent Dr. Gennaro “Jamie” Piraino and Board Vice President Dr. Traci Eshelman Ramey talked through the possibilities, one priority quickly rose to the top: protecting student data.

“The more I dug into the exposure that schools have, the more imperative it became to act,” says Eshelman Ramey. “Whether it’s through formal policy, raising awareness or building safeguards, privacy has to be central.”

That focus mirrors a national concern. The 2025 National Student Data Privacy Report from the Consortium for School Networking (CoSN) found that while technology use in schools is accelerating, many districts have yet to establish even the most basic data governance practices. PSBA Policy Service members can use Policy 830.1 Data Governance - Storage/ Security issued in the Policy News Network (PNN Vol II May 2023) and the correlating administrative regulation to support the school board’s commitment to sound data governance in protecting the integrity and security of the data collected, maintained, stored and managed by the district.

“There are fundamental privacy practices that have been norms for decades – establishing what data you will collect, how you will use it, why and how you will share it, how you will protect it, and how long you will keep it,” says Linnette Attai, privacy consultant and project director of CoSN’s Student Data Privacy Initiative. “Those don’t change just because there’s a new technology. But without them, you can’t create effective AI policy.”

The state of privacy in schools

Attai notes that AI-specific rules are important, but they must rest on solid ground. Yet CoSN’s national survey revealed gaps that cut across geography, size and budget. Almost three-quarters of those responsible for student data privacy do not have it in their job description. Just over half of districts have basic policies on data retention and protection. Many technology leaders have never been trained in privacy, and some pay for their own training.

“The instinct is to reinvent the wheel every time new technology comes along,” she says. “You don’t need to reinvent the wheel –you need to make sure the wheel is solid.”

Without a solid foundation of technology policy, questions about AI, such as whether a generative tool is “school ready” or “student ready,” can’t be answered with confidence. “Generative AI isn’t inherently built for K–12,” Attai says. “The question for boards is whether a given tool meets your standards for privacy and educational value.”

For boards looking to build that foundation, CoSN offers practical starting points. Its Student Data Privacy Toolkit walks districts through legal requirements, vendor partnerships and community trust-building. The Trusted Learning Environment (TLE) Seal

program goes further, outlining 25 key practices in leadership, business, data security, professional development and classroom implementation.

Districts meeting these standards report stronger governance, more consistent vendor vetting, and higher levels of parent and community confidence, says Attai. In states like Illinois and Indiana, groups of districts are now working through the TLE process together, sharing ideas and policies in real time. This is proof, Attai says, that privacy readiness is achievable when it’s treated as an ongoing, systemwide priority rather than an isolated tech issue.

“Privacy doesn’t care what technology you’re using,” Attai says. “It’s about the data. Once you have strong privacy practices in place, you can adapt to any tool, including AI, with confidence.”

Franklin Regional’s policy journey

For Franklin Regional, these lessons underscored the need to approach AI with both innovation and strong governance in mind. The district's approach began with a structural change: merging its curriculum and technology committees into a single body.

“Curriculum and technology can’t be separate anymore,” Eshelman Ramey says. “Curriculum needs technology, and technology needs to understand what curriculum is doing.”

From there, the district formed a multistakeholder AI task force. Members included board directors, administrators, teachers, the IT director and community members. They brought a wide spectrum of views, from those advocating caution to early adopters eager to experiment.

Piraino describes it as a cultural norm at Franklin Regional to seek multiple perspectives before setting policy. “We pride ourselves on being future-focused, but also on developing responsible citizens,” he says. “That means engaging students, staff, parents and industry leaders in real dialogue about AI.”

The policy they’ve drafted, set for board review this fall, takes a broad approach. It doesn’t treat AI as a one-off issue but as part of a larger framework for any new educational technology. The district will require all tools to go through a standardized vetting process – using a rubric that brings together curriculum experts, technologists and end users – and to meet baseline compliance with federal privacy laws such as FERPA, COPPA, CIPA and HIPAA before being considered for adoption.

Other elements include ongoing professional development — already shifting mindsets in the district. Teachers who initially pushed to block AI have become proficient in using it for activities such as providing feedback on writing assignments or helping students brainstorm ideas. English and speech teachers have been among the first to find productive, ethical classroom applications.

“Our teachers have been fantastic at figuring out when and how AI can make learning more powerful,” Piraino says. “It’s not about replacing critical thinking; it’s about using the tool to deepen it.”

As districts explore artificial intelligence, policy decisions will shape how – and whether – these tools support teaching and learning while protecting student privacy. Keep these five principles in mind:

1. Build on a strong foundation. AI policy is only as good as your existing privacy framework. Before adopting new tools, ensure you have clear, enforced policies for data collection, use, protection and retention.

2. Vet every vendor in writing. Contracts should clearly state who owns the data, where it’s stored, how it’s secured and when it will be deleted. Avoid vague clauses and make sure your district controls consent requirements.

3. Keep a human in the loop. AI can support grading, assessment or personalized learning, but it should never be the sole decision-maker. Require human review to catch errors and address bias.

4. Treat policy as a living document. Technology will change faster than your governance documents. Schedule regular reviews – at least annually – to update policies, address new risks and incorporate lessons learned.

5. Teach responsible use. Blanket bans may limit innovation without reducing risk. Equip students and staff with the skills to use AI ethically and effectively, so they’re prepared for life beyond the classroom.

*Considerations for general interest. Not intended to be taken as legal or policy advice.

Visit the PSBA Institute’s Center for AI in Education website at psba.institute for more resources and to register for the Foundational AI for School Leaders certificate program, which has been approved for Act 45 credit.

"We pride ourselves on being futurefocused, but also on developing responsible citizens,” Piraino says. “That means engaging students, staff, parents and industry leaders in real dialogue about AI.”

Attai agrees that a blanket ban is rarely the answer. “You’re better off teaching students to be responsible users. That’s how you prepare them for the real world.”

And because the technology will inevitably change, agility is written into the policy. “We have to acknowledge that this is going to change tomorrow,” Eshelman Ramey says. “You can’t set it and forget it.”

The legal imperative

While no federal law is written specifically for AI in schools, existing student privacy laws still apply. FERPA, IDEA, HIPAA, COPPA, CIPA and the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment all impose requirements on how student data can be collected, shared and stored.

“Every single one of these laws could come into play when you use AI,” says Attorney Jonathan Huerta of KingSpry Attorneys & Counselors. “The biggest risk is loss of funding. Many of these laws are tied to federal or E-Rate dollars. But you can also face discrimination claims, reputational harm and parent backlash if something goes wrong.”

Huerta advises school boards to make vendor vetting a high priority. Contract terms should specify the jurisdiction for any legal disputes, avoid overly restrictive limitation of liability clauses, and clearly state who owns the data, where it’s stored, and when it will be destroyed. Vendors often push the responsibility for obtaining parental consent onto the district, so boards should know whether the consent required is active (opt-in) or passive (opt-out) and ensure it’s well documented.

He also warns of potential pitfalls when AI tools are used for assessment or grading.

“If there’s implicit bias in how an AI system evaluates work, that could open the door to discrimination claims,” he says. “And from a practical standpoint, boards should remember that no AI system is infallible. There has to be a human in the loop.”

Both Huerta and Attai stress that AI policies must remain agile.

“It’s tempting to think of policy as a box to check,” Attai says, “but privacy is never done. You’re constantly improving, auditing and adapting.”

Huerta recommends at least annual reviews – if not more frequent – to align with evolving laws, tools and political priorities. This includes monitoring changes at the federal and state levels.

Under the Biden administration, federal guidance emphasized oversight and educator-focused resources, including a detailed AI implementation handbook for schools. More recent policy statements from the Trump administration have shifted toward deregulation to promote innovation, with fewer direct resources for K–12.

“The political environment matters because it can change the guardrails – or the perception of them – very quickly,” Huerta says.

In Pennsylvania, PSBA has already issued a model policy for AI in schools, encouraging districts to establish cross-functional teams, provide ongoing training and conduct regular

reviews. Likewise, PSBA released a policy guide (Policy 815.1) to members of its Policy Service, which sets the board's expectations for the proper management and responsible use of generative AI in schools. “The policy is the start,” Huerta says. “It’s the review and enforcement that make it work.” (See more on PSBA’s Policy 815.1 on page 17 of the Fall 2024 issue of School Leader Bulletin.)

As Franklin Regional prepares to bring its AI policy to a board vote, Piraino and Eshelman Ramey both emphasize that this is the beginning, not the end.

“AI policies must be sustainable and agile, ready to shift when the technology does,” Eshelman Ramey says. “At its foundation, viewing privacy as a shared responsibility – no matter what the next innovation may be – is vital.”

For boards across Pennsylvania, that mindset may be the most important takeaway. AI will continue to evolve, and so will the tools schools use to teach, assess and manage student learning. The challenge –and the opportunity – lies in ensuring that innovation and privacy advance together.

“Privacy doesn’t care what the tool is,” Attai says. “It cares about the data. Get the fundamentals right, and you’ll be ready for whatever comes next.”

“Privacy doesn’t care what the tool is,” Attai says. “It cares about the data. Get the fundamentals right, and you’ll be ready for whatever comes next.”

PA.

BY JIM PATERSON

Soon after Dr. Dan Potutschnig took the superintendent’s position at the PhilipsburgOsceola Area School District, he and his wife purchased the home they loved, but they felt it needed a new floor. With a background in the trades, he knew he could add the hardwood flooring himself, perhaps with some help. “I just wasn’t expecting where the assistance would come from,” he says.

After a few meetings with school board director Richard Wood, they began discussing the flooring – and Wood volunteered to help. “So that was my introduction to the district – working with Woody on the floor in my house. It was a great way to start our relationship and learn about the district – and it’s a relationship that has paid off many times over.”

Potutschnig was lucky to have that bond develop early in his stint at his district, which straddles two counties in the center of the state. Experts say that one of the critical things for superintendents as they are onboarded is developing multiple new relationships – and school board directors are a priority and great source for other connections.

Wood, a veteran of the board and now the president, made sure not only that he and Potutschnig got to know each other, but that the new superintendent met people throughout the district. “He fit right in,” Wood says. “This is a blue-collar region, and Dan is from the area and has a background in the type of work a lot of people do here,” he added, noting that Potutschnig is a trained machinist and taught the trade before getting on the administrative track and working as a superintendent at the Millersburg Area School District.

Dr. Sherri Smith, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators, says the way the board helped connect Potutschnig with various sectors and the work he did on those relationships is a critical part of onboarding new superintendents to set them up for success. “You need to build that Team of 10 with the board,” she says, “and that takes time and the building of trust. Then you have to focus on relationships with everyone else inside and outside of the schools.”

It is particularly important now, she says, noting that superintendent turnover is high. That means boards are more likely to be working with new administrators and finding it necessary to create an atmosphere right from the start where they can succeed.

In Pennsylvania, about 20% of superintendents in its 500 school districts are leaving their positions each year, Smith says. On the national front, the rate of superintendent turnover has remained high post-pandemic, with Education Week reporting leadership changes at 1 in 5 school districts in the 2023-24 school year, among the nation’s 500 largest districts.

Experts note that the process of making connections for a new superintendent can begin even before the person is on the job, through communications to the public and staff describing their qualifications and why the board chose them.

Smith suggests each board director have responsibility for a certain part of the transition plan. Elements of a cohesive plan might include: a prioritized description of existing district goals and plans; platforms for communications (news releases, social media accounts); a superintendent webpage with relevant material; a primer for the new superintendent about the budget; school facilities or collective bargaining issues; and even a tip sheet about key players on the staff or in the community. Because hiring is a collective decision made by the board, individual directors should make a point

“We see ourselves as more of a support group as he gets to know the district and what is needed here and then undertakes the work,” Wood says. “We don’t want to be micromanagers flying all over the place and doing too much, even early on.”

of supporting the process, and the final hiring decision, despite how they may have personally voted.

At this stage, Smith says, it is also valuable to make a connection between the district’s goals and that person’s strengths, which can give the community an idea about where the new superintendent will focus.

In Potutschnig’s case, Wood early on arranged a visit to the DiamondBack truck cover company, which has grown to be a major employer in Phillipsburg with a strong reputation for involvement in the community and support for education. “I knew that Dan could speak their language and that he’d appreciate what they had built here. I also knew that connection with DiamondBack would be helpful to the district,” Wood says. Potutschnig notes that the firm has offered the district mini grants and been a sponsor for a steady stream of school and community events.

Jack Silva’s experience as the recently hired superintendent at the Bethlehem Area School District has been different than Potutschnig’s, in part because the Philipsburg-Osceola district has about 1,600 students while Bethlehem has about 14,000, though both jobs are complex and present many of the same challenges. But Silva also had been the assistant superintendent at Bethlehem for 13 years prior to being named superintendent in July 2023.

“We were very fortunate because we had a long-time superintendent, and when he says was going to retire, we then had an incredibly qualified person to fill the position who was well-known to us and was very familiar with the district and the work we were doing,” says Karen Beck Pooley, a school director at Bethlehem for 10 years and a PSBA Governing Board member.

She says that meant not only did Silva have that familiarity with the schools, community and school leaders, but the district did not have to undertake a superintendent search.

and could move the transition along more quickly, particularly since the existing superintendent gave the board notice around six months in advance, and they could name Silva.

“We bypassed a superintendent search, which is not easy now, and we gained valuable time,” she says. But Silva says there was still an adjustment. “I had an opportunity to have a rich and personalized transition during that period, but there is a big difference between being a superintendent and assistant superintendent. There was a lot to learn, but I had good relations to build on and great support.”

It meant Silva still felt compelled to fully introduce himself to the community, including sharing the strengths and ideas he thought he would bring to the role. He also initially focused on listening to members of the board, staff and community. He was pleased to find the board helped in that process, while his familiarity with Bethlehem, where he grew up, also made it easier.

“Jack knew the district, and we encouraged him to use that background and those connections. And he showed up in all types of venues,” Beck Pooley says.

Silva says he got to know not just people in the district but the roles various people had in the schools and the community, and began to better understand the key issues and goals more thoroughly. “I also really focused on the board, too, and developing that Team of 10,” he says.

And Beck Pooley says the key “outward facing” role of the superintendent was different than the role of the assistant, and that’s something school directors could assist with.

The transition, Smith says, involves a willingness to listen and accept various viewpoints, which school directors can encourage. “If someone disagreed with me when I was a superintendent, I’d just tell them ‘Ok, that is good to know. Thank you.’ And then I would bring them data about that issue to have a fuller discussion,” Smith says. “Many times, they would have a valid point, and I would learn something. That approach is something board members can encourage, especially with a new superintendent.”

She stresses that the superintendent and the school board directors should take that positive approach – assuming that members have something to offer and valid concerns – but can disagree. And then the board should reach a consensus and move forward, allowing the superintendent to implement the decision that has been arrived at.

Right from the start, Potutschnig sought the perspective of the board on a variety of issues. And in keeping with best practices, school director Wood says his board focused on providing support and governance while looking to Potutschnig to handle the day-to-day operations of the district. “We see ourselves as more of a support group as he gets to know the district and what is needed here and then undertakes the work, Wood says. “We don’t want to be micromanagers flying all over the place and doing too much, even early on.”

Potutschnig felt it was important to reach a consensus on key issues immediately facing the superintendent. “In the first six months as new superintendent I thought it was important for the school board and I to be as closely aligned as possible,” he says. “If the voices and messages can be aligned, then, as much as possible, the superintendent will have a clearer path and be able to focus on agreed-to priorities.”

Wood and Potutschnig both stressed that initially they prioritized listening to various views and gathering input, including through surveys and open-door policies that allowed any stakeholders to meet with them.

Building the relationship with the board takes a very intentional effort on both parts and to some degree establishing systems for working together, including what Silva says was an agreement to implement the PSBA Principles for Governance and Leadership as a fundamental guide about how operations by the board and superintendent should unfold.

That includes developing a structure for communications to the staff and the public. “It helps when the ‘hot potatoes’ come. When you have an HR issue that is in the newspaper or a controversy about a student, it is important that you have a way of providing an accurate, clear message.”

Smith emphasizes school directors have to be patient. “The best gift a board can give a new superintendent is the gift of time. It is a very challenging, chaotic position,” she says. “It’s not like making chocolate bars, especially early on when there is so much to learn. Boards have to provide guidance and information and give new superintendents time and space to develop.”

She suggests that the onboarding really lasts three years, with the first dedicated to learning and building relationships. She also suggests boards encourage superintendents to get professional development. Silva says that the information he and his board received in professional development programs from PASA and PSBA was invaluable.

In the second year, the new superintendent begins to more completely take charge and better understand what the district priorities should be and what they want to do. “In that second year, I think you can really build your executive team and assess the strengths and weaknesses,” Silva says. “I think of it as the “nuisance year,” Smith adds. “All those more challenging issues you began learning about the first year you must tackle now. It’s also a time to assess things for a longer-term plan.”

Then in the third year, Smith says, the superintendent should work with stakeholders to develop at least a five-year plan and begin to implement it. “Have a plan for the onboarding process,” Smith says. “Be collaborative and be patient.”

“You have to give them time and space,” says Beck Pooley.” A big part of their initial work is getting to know the administrative team, the teachers and the people and organizations in the community – and who are big players in the work of the district. Boards have to recognize that time pays off.”

“Behind every meeting there are hours of unseen preparation. Meetings don’t simply run smoothly on their own — they do so because a secretary has prepared with precision.”

BY ANGELA CONIGLIARO

Across Pennsylvania, 4,500 school board directors volunteer their time and talents to serve students in the Keystone State. While their role may not always be visible to the public, board secretaries are instrumental in ensuring smooth operations, accurate documentation and well-run meetings. Their attention to detail and organizational skills help boards function efficiently and stay focused on their mission. Their job influences every part of school board governance.

Behind every meeting there are hours of unseen preparation. Agendas must be drafted, public notices posted, rooms prepared and countless details coordinated. Meetings don’t simply run smoothly on their own, they do so because a secretary has prepared with precision.

In Pennsylvania, every public school district is required by law to have a board secretary, sometimes called a recording secretary. Typically appointed by the school board for a term of one to four years, this individual is responsible for keeping the official records of the board.

“In Pennsylvania a board secretary can be a paid district employee or a voting member of the school board who is elected by the board to serve in this role,” says Jessica Portz, PSBA leadership engagement manager. “According to the School Code, who is qualified to hold the role depends on the district’s community population size.” She explains that for districts with a population of fewer than 30,000 (Third or Fourth Class), the board secretary may be either a voting member of the school board or a district employee. A majority of Pennsylvania’s 500 school districts – about 360 – are in this

category. However, in those districts with a population of 30,000 or greater (Second Class, First Class and First Class A), about 110 school districts, the secretary cannot be part of the elected board.

Because some board secretaries are volunteer members of the board and others are paid employees, there can be a difference in the scope of the work for which a board secretary is responsible. However, certain tasks are appointed to this role by the PA Public School Code.

For those in paid positions, the role could be full-time or part-time depending on the size of the district. In larger districts, the secretary is often a professional administrator. In smaller districts, it may be someone who wears multiple hats, like a business manager or central office employee.

At the Shikellamy School District, veteran board secretary Bethanne Zeigler sums up her role, “I am responsible to be the historian, part event planner, part compliance officer and part communication hub, ensuring the board’s work is both efficient and transparent.” As a district employee, she works closely with the school board, although she is not a voting member. With 27 years at the helm, Zeigler has become an expert in balancing responsibilities. She describes herself as “the quiet architect of order, trust and continuity” a fitting title for someone whose work ensures school governance remains strong.

Ask Jody Brahosky what she does as a school board secretary, and her answer is surprisingly simple: “I am the central point

"The hard truth is that I am expected to be a historian, legal compliance officer, project manager and peacemaker all at once – and to do it flawlessly, because any misstep can affect the board’s credibility and legal standing.”

of contact for the board.” But as anyone who has worked, volunteered or spent time in public education knows, there is so much more to the role. Brahosky has been employed as board secretary at the Greater Latrobe School District for the past seven years. She is responsible for recordkeeping, managing documents, and making sure that policies and decisions are communicated to staff, school directors and the public. She is both a behind-the-scenes organizer and a frontline communicator.

In addition, secretaries act as the official liaison between the school board and the Pennsylvania Department of Education. They manage election certifications, handle financial reporting, and ensure that the board follows state laws and local policies. All of these responsibilities form an architecture of school governance, ensuring meetings operate smoothly, records are accurate, and school districts are compliant at the state and federal levels.

The average person may not understand the importance of compliance or the role the board secretaries play. “Most people don’t realize that I play a huge role in keeping the district compliant with regulatory state, federal and district policies,” Brahosky says. It’s not only recording the votes and meeting minutes, but also making sure those decisions are legally sound and properly documented.

One example where compliance is key is at the board organization meeting, says Portz, who

serves as liaison between PSBA and its affiliate, the School Board Secretaries Forum. “The School Code requires boards to hold their organization meeting during the first week of December, and there are specific procedures for what must take place at the meeting. The board secretary often handles each step, making sure the board is compliant and able to conduct business going forward,” she says. The meeting is especially key in an election year when new directors are officially seated during organization.

For taxpayers, compliance means stability, ensuring budgets are used as intended, hiring decisions hold up to scrutiny and policy changes follow procedures. Board secretaries watch the details, providing accountability for the work of the board and impacting the community’s trust in the district.

When you spend so much time with the board, the secretary often becomes the keeper of institutional memory. “I remind the board of past decisions, policies and legal precedents that impact current discussion,” Zeigler says. “When leadership changes or veteran members leave, I provide the historical data to keep things moving.” In addition to the paperwork, board secretaries often manage meeting technology too, making sure microphones work, the livestream is functioning, and school directors’ devices are charged, turned on and ready to go.

Zeigler also manages confidential and sensitive information, and coordinates training for new school directors. “The hard truth is that I am expected to be a historian, legal compliance officer, project manager and peacemaker all at once – and to do it flawlessly, because any misstep can affect the board’s credibility and legal standing.”

So much preparation goes into a board meeting, sometimes weeks earlier. A week before the Greater Latrobe School District’s meetings, Brahosky begins the agenda. She looks back at prior years to make sure recurring approvals are not being missed, and works with the superintendent to

gather contracts, supporting documents and review drafts. When it’s ready, the agenda is posted, in accordance with Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act – another duty that falls under the purview of the board secretary. The Sunshine Act requires open and transparent board meetings, and highlights the board secretary’s importance in posting notices, preparing accurate agendas and keeping public records (see sidebar).

Shikellamy’s school directors arrive at each meeting to find a comprehensive board packet including prior minutes, contracts, reports and supporting documents. This helps ensure the board is prepared for the meeting and has all of the necessary items to do its job.

Anyone who has attended a school board meeting knows there can be a lot of information in a short amount of time. This is why Zeigler pre-fills minutes using templates she has created over the years. She says this process allows her to speed up documentation after the meetings.

Of course, even with the best preparation, there can always be surprises. “Sometimes just before a meeting, I’m advised by the superintendent or solicitor that a change needs to be made,” Brahosky explains. “It may be something that comes out of executive session. That gives me only minutes to prepare additional resolutions.”

Zeigler agrees that flexibility is key. Seated between the superintendent and business manager during meetings, she keeps an eye on the clock and notifies them if discussions are running over time, passing notes when adjustments are needed and ensuring communication flows smoothly.

As technology has advanced over the years, so have the tools utilized by board secretaries. Now, Google Docs helps Greater Latrobe employees collaborate in preparation for meetings. Shikellamy schools use the paperless BoardDocs system in conjunction with PSBA Policy Services to help manage agendas, policies

and compliance tracking. But no matter what technology is used, the fundamentals remain the same. “I do my best to know the agenda inside and out,” Zeigler says. “Templates and preparation are key.”

In an era when school board meetings are often livestreamed or scrutinized on social media, transparency has never been more important. For Brahosky, that means ensuring accurate records, accessible documentation and constant reminders to school directors about confidentiality and compliance. “We make it a point to remind our school directors of the importance of adhering to student and employee privacy laws, the confidentiality of executive sessions, and the safety and security measures of the district,” she says.

Zeigler takes a similar approach, ensuring that public notices are posted correctly and that executive sessions are properly announced. She sees herself as a bridge between the board and the community. “I ensure things are posted and provided to the public in a timely manner,” she says. “That’s how you build trust.”

For Brahosky, the hardest part is navigating community engagement during controversial times. “Respectful discussions” can be difficult to maintain when passions run high, and she must remain steady and professional even when the room is tense.

Zeigler points to the challenge of gathering information from multiple stakeholders. “I’m relying on people with different priorities and timelines, and I need everything to line up by a certain deadline,” she says.

Despite the demands, ever-changing challenges and growing scrutiny of public school boards, Brahosky finds her job rewarding, especially when the decisions support putting students first. “We are all

here to do what is best for students and to be fiscally responsible,” she says. “I take great pride in knowing that my work has helped do that.”

Zeigler finds meaning in building relationships across all levels of the district. “I work closely with the board, superintendent, administrators and the public. I often have a hand in helping new directors feel oriented and confident.

Neither Brahosky nor Zeigler planned to become a school board secretary, but both found their way into the role through a willingness to take on responsibility. Brahosky first joined the Greater Latrobe School District a decade ago, initially helping to create the Child Accounting and Central Registration Department. In addition to her work, she also serves as a member of the PSBA School Board Secretaries Forum Steering Committee and as a mentor in the association’s Mentor Program. Zeigler has spent nearly three decades at Shikellamy. She is currently serving as president of the PSBA School Board Secretaries Forum and the Affiliate Council representative on the PSBA Governing Board.

School board secretaries may not all have a vote or microphones during debates, but their fingerprints are everywhere in the work of a school district. They ensure the public’s right to know, maintain the historical record of decisions, and orchestrate the logistics that allow boards to focus on policy rather than paperwork. They embody the principle that effective leadership requires groundwork for decisions to be made wisely and help foster trust between the board and the community.

Through their dedication, precision and professionalism, Jody Brahosky and Bethanne Zeigler exemplify a role that is vital to the success of public education.

Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act requires school boards to operate with transparency and accountability. Below is a refresher on the basic requirements for boards under the act. Learn more in PSBA’s A Practical Guide to the Pennsylvania Sunshine Act, available for purchase.

1. Public notice

a. Meetings must be advertised in advance in a newspaper of general circulation and posted at the district office and website.

2. Open meetings

a. All deliberations and official actions must take place in public.

b. Meetings cannot be conducted outside of the public view unless permitted by law.

3. Executive sessions

a. Private sessions are allowed only for specific reasons, such as personnel matters, collective bargaining, legal consultation with the solicitor, real estate negotiations or sensitive security issues.

b. The board must announce the reason for the closed session in public.

4. Public participation

a. Citizens must be given a reasonable opportunity to speak on matters before the board takes action.

5. Minutes and records

a. Boards must keep official minutes of all meetings, including date, time and place; names of members present; the substance of all official actions and votes, along with the names of citizens who appeared and the subject of their testimony.

Compliance with the Sunshine Act isn’t optional, it’s the law. For school board secretaries, ensuring these requirements are met is one of their most critical responsibilities.

Angela Conigliaro is a public school communications professional and freelance writer in the Allegheny region.

BY SEAN RUCK

Ashlie Crosson is a lesson in firsts. Very few teachers get recognized at the national level for their abilities. Fewer still have been recognized as the National Teacher of the Year hailing from Pennsylvania. Ashlie Crosson is among the latter group, which, counting Crosson, totals ... one. Since the initial award was given back in 1954, there was never an honoree from Pennsylvania until Crosson’s accomplishment.

Years before she became the first National Teacher of the Year from the commonwealth, where she was also named State Teacher of the Year, Crosson chalked up another first that was even closer to home. She became a first-generation college grad, earning a bachelor’s degree in English and language arts.

After earning her bachelor’s degree in 2011, she took a teaching position with the Bellefonte Area School District and went on to pursue a master’s degree in educational leadership from Penn State. By 2020, Crosson went full circle, taking a position teaching high school English in the same district she attended as a teen.

According to Principal Kelly Campagna, Mifflin County High School serves grades 10 through 12, with an enrollment of about 1,000. A little more than half of students are socioeconomically disadvantaged based on free and reduced lunch data – just 5% higher than the national average. Campagna says for Ashlie’s department, they try to limit class size to 22.

With these circumstances, Crosson has a fair foundation from which to work her classroom magic, but there is a little more to the story. As a countywide school, the sending region for students is large. “Our superintendent will tell people – and this is fact – that our buses and vans travel on any given day between the morning and afternoon runs, about 10,000 miles a day,” says Campagna. “We’re not the largest though – we’re probably in the top 10 or 15. I think we’re roughly 367 square miles.”

Long bus rides equal early rise times for students, and sleepy students can be hard to motivate. Still, Crosson manages to provide the energy to jumpstart the class and dive in.

According to Crosson, she entered college as a journalism major, encouraged by her own high school journalism teacher. “He had a profound positive impact on me and that was the route I was pursuing,” she said. Soon though, she realized that while she loved journalism, and did keep it as a minor, she also had a great number of teachers who had a positive impact on her schooling experience and life. “I quickly decided I wanted to change my major and I decided if I could give to another generation what was given to me by my teachers, it would be a really beautiful way to spend my career,” she says.

This year, her 15th in teaching, looks very different from the past due to her role as a National Teacher of the Year ambassador. In September when this article was written, she was just over two months into the new experience. “For me, I didn’t realize how much talking about my community, and about my students and about my school, was going to be this bittersweet experience because I miss it 10 times more,” she says. “There’s a great irony – you’ve become National Teacher of the Year and then leave the classroom for a year so you can complete this year of service. So, it’s been a really good reminder of why I chose to teach, why I chose to teach where I teach, and why my community and my students are so integral and valuable to my identity as a teacher. I wasn’t necessarily expecting this very public role to bring so much personal introspection. It’s difficult. Everyone is

gearing up for back to school and what that looks like for me is very different. It really reminded me I have to make the most of every moment of this experience because I’ve traded it for all the tremendous experiences I get in 180 days of teaching,” she said.

When it came to the announcement, Ashlie said she was sitting on the couch in her living room when she got the call that informed her she had been named National Teacher of the Year. And then, dead silence for 45 seconds – on Ashlie’s side. “I just was really in disbelief. Pennsylvania never had a National Teacher of the Year, and my district never

had a state Teacher of the Year. Every step has been more than I thought or had imagined.”

Campagna was surprised after the announcement as well. “After Ashlie won, we met with representatives from the organization and they shared a slideshow with us and some facts about the honor. When the person presenting the slideshow shared with us that Ashlie was the first-ever Pennsylvania National Teacher of the Year, that was a big moment. I knew it was already a big deal, but to be the first honoree from our state makes it a big deal not only for Mifflin County High School, but also for the state of Pennsylvania.”

Ashlie said after she was informed of the honor, she went through a lot of doubts and questioning, wondering if she was the best person to represent a whole profession. “I don’t think anyone is ever going to answer ‘yes’ to that. And so learning to be secure and grow into this role was really overwhelming for me at first. But then I looked at it like how I look at my classroom – I want students to grow into their roles. I want them to feel like they can accomplish something they never thought they could.”

As she explained, it’s important to practice what you teach. Having taught before, during and after COVID, Crosson and her colleagues in education have already had experience growing into new roles, accomplishing things in the face of adversity and overcoming obstacles seldom seen in education. All that has been made more difficult because it’s easy to see the impact the pandemic had on students too.

“What’s interesting is we’re four or five years out now. So every year, the ‘COVID year’ for my students is a different grade,” Crosson explained. “What’s been very interesting to me is to see how that has impacted a learning gap for growth for students. Because now for me, my students were probably in fifth grade when they went through COVID.”

Crosson pointed out that fifth grade is instrumental in ushering in more extended writing practices – moving between sentences and paragraphs and essays. Having disruption at that critical time can be problematic. “You can start to see how pieces of that are a little bit more challenging. They feel different from my previous students. As

educators ... every year, you have a different thing you have to address or teach or circle back to, based on what year was [the students’] COVID year. I would say that’s the same for every teacher in every grade level even going down to our elementary students, who would have been in preschool, and what social learning was different for them.

“The other thing I would say is I talked to a lot of teachers and so many of them said last year was the first year that started to feel normal again, to feel like they could build the same level of rapport and engagement with their students. It’s so hard thinking we really had a long-term challenge from this and we’ll be addressing it for an entire generation, but it does make me happy to think this upcoming school year is going to be top of the mountain for kids and teachers. I think we’re all coming into this in a really good place. That’s my hope and I feel encouragement from a lot of my colleagues.”

Ashlie’s optimistic and perceptive extrospection are likely just some of the attributes that earned her the national accolade. Her teaching skills and approach certainly played a strong role as well. “In terms of teaching style, I’m pretty big on the idea that you get what you give,” she said. “I want my students to feel comfortable asking questions, taking risks, feeling like they have room to grow, and it’ll be ok if it’s a little wonky or doesn’t go the way they thought it would.”

In accordance with her “walk the talk” approach, Ashlie said it’s important for her

to admit mistakes too, if they come up. “My philosophy of teaching is that it’s important for students to know their teachers are human too, and it’s the first time we’re living this life. When something doesn’t go right, or we’re reviewing a test, students can question or challenge. So much of my class is very open dialogue with students so that their learning is authentic to them and there’s very much a sense of community and transparency between us as we can within a classroom that really needs to maintain a pretty high level of productivity and expectation, but also a pretty high level of grace.”

With her new title of National Teacher of the Year, it may be harder for her students to see her as human, or at least, as fallible, but they’ll have time to adjust to the idea. “In April and May when I was a finalist, they were like, ‘Oh, it could be you, it could be you!’ there was all of this excitement.” Crosson recalled. “And then I was named, and I came back to school and they’re like, ‘Wait, does this mean you won’t be here?’ But that was important for students too. I want them to know their learning is in their control. Sure, we thought we were going to have class together and I was really, really looking forward to it and maybe they were too, but this isn’t going to stop them from having a tremendous year of growth and learning. They get to have that ownership, it doesn’t belong to me.”

Read more about Crosson and the Teacher of the Year awards at the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) webpage, ntoy.ccsso.org.

With Ashlie Crosson just beginning her time as the National Teacher of the Year (NTOY), the Bulletin turned to someone who could offer some hindsight about the experience. Missy Testerman was the 2024 honoree. We asked her what the most surprising aspect of her time in that role was. Here is her response:

“For me, the most surprising aspect of my experience as the National Teacher of the Year was that educators and schools all across this country are facing a lot of the same challenges. Until I was a State Teacher of the Year and had the opportunity to network with all of the amazing teachers in my 2024 State Teachers of the Year cohort, I honestly thought the challenges I saw in my school, my region and my state were specific to Tennessee or the Southeast. What I saw and learned as the NTOY is that mental health issues, funding challenges and concerns about an ample supply of well-qualified teachers were taking place all over the country. Whether it was in urban cities in California or rural towns in North Carolina, districts and educators were facing the same issues. What did not surprise me, however, was how invested teachers were in their students and helping them to be prepared so they had every opportunity to create successful futures for themselves. That was universal, no matter where I went.”

SARAH ERDMAN BOARD DIRECTOR, MIDD-WEST SCHOOL DISTRICT

What motivated you to become involved in board service?

I have always been passionate about serving my community, particularly in the field of education. When my daughter entered high school, I saw an opportunity to make a positive impact by running for a position on the school board. During my four years of service, I was able to support students and families by helping address any issues that arose and by working to ensure a positive learning environment for all.

What issue in public education is most important to you right now?

The two issues that concern me most are mental health and the teacher shortage. Students are facing increasing levels of stress and anxiety, which directly affects their ability to learn and thrive. At the same time, the ongoing teacher shortage places additional strain on schools, impacting both student support and educational quality. Addressing these challenges requires investing in mental health resources for students and staff, as well as creating stronger support systems and incentives to attract and retain qualified educators.

What is your biggest passion outside of board service?

I am beginning a journeyto become a court-appointed special advocate (CASA) volunteer. I’m passionate about supporting children who need a strong voice and advocate in the court system. This role aligns with my commitment to helping young people overcome challenges and ensuring that every child has the opportunity to feel heard, valued and supported.

What is a board-related accomplishment you would like to share?

One of my proudest accomplishments was serving the board as the PSBA liaison. I was chosen to present a Mental Health Matters workshop at the 2023 PASA-PSBA School Leadership Conference, where I was able to share strategies and resources to support student well-being. Another deeply meaningful moment was presenting my daughter with her high school diploma this past May — an experience that represented both a personal and professional milestone in my service on the board.

Are you interested in being a Member Spotlight in an upcoming issue of the Bulletin? School directors from PSBA-member districts may email jackie.inouye@psba.org for consideration.

AMANDA COOK BOARD PRESIDENT, SUSQUEHANNA COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT

What practices or procedures does the board have in place that foster a good working relationship with the superintendent and/or other administrative staff?