Public Care Infrastructure and Political Economy

My research in care infrastructure such as kitchens, laundromats, and community gardens studies the relationship between the technologies, knowledges, and practices of daily life and state-making in the Global South. I study this relationship primarily from two perspectives. First, I explore the struggles and mechanisms of the feminist movement and civil society for positioning care, unpaid housework, and emotional labor within the political agenda of the state. Second, I theorize that once care is within the state, it not only proposes a new policy realm but also other moral economies, ways of relating, types of expertise, materialities, and temporalities that radically transform states and democracies. My research in care infrastructures thus contributes to new theories of the state and civil society from the Global South.

In recent years, care infrastructure has rapidly moved away from the domestic sphere into the public realm, especially in Latin America. For example, between 2013 and 2017, Uruguay, Perú, México, Guatemala, El Salvador, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Colombia began measuring care time as an indicator of economic activity. Between 2021 and 2025, México, Colombia, and Chile developed nationwide networks of care infrastructure, known as “systems of care,” to reduce, redistribute, and recognize unpaid housework. Between 2019 and 2021, during El Estallido Social (“Social Outburst”), kitchens across Latin American cities were moved from private households to public streets to feed protesters. These “ollas comunitarias” (community pots) became the heart and epicenter of protests and kept them ongoing for weeks, even months. The chant “el estado no me cuida, me cuidan mis amigas” (“the state does not care for me, my girlfriends care for me”) has become a feminist anthem among Latin American social movements. Motivated by these and other case studies, I argue that there has been a care turn in the political economy of states, particularly in the Global South. My research asks how “care” or unpaid housework has become a policy concern. Further, what is this emerging care infrastructure doing not only to its beneficiaries but also to the state?

I take an interdisciplinary approach in my research, utilizing policy analysis, environmental design, and feminist science and technology studies (FSTS). My research projects all feature a creative ensemble of mixed methods, such as ethnography, econometrics, geographic information systems (GIS) analysis, and photography.

Thanks to the public-interest nature of my research, I have had the opportunity to collaborate with, work with, and present my work to at least 13 different organizations, including government agencies, NGOs, and academic institutions, during my Ph.D.1

1. Care Within the Post-Technocracy

I am currently working on a book project titled Disorienting the State: Care Infrastructure and the Post-Technocracy in Bogotá. The project is a one-year multi-site ethnography of a public policy: the Bogotá System of Care led by the Women’s Affairs Office (WAO) of the Bogotá City Hall. This policy aims to dismantle patriarchal culture by reducing, redistributing, and recognizing unpaid housework through laundromats, soup kitchens, and a sui generis school of care for men, among other public care infrastructure. The System of Care is one of the largest social policies in Bogotá, with an investment of over 1 billion USD between 2019 and 2022 about 5% of the city’s budget. Throughout my fieldwork as a volunteer with the WAO, I have followed the

1 I have collaborated with the Women’s Affairs Office of Bogotá, United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) in Barcelona, the New York City Health and Hospitals, the New York City Mayor’s Office of Climate & Environmental Justice, the International Rescue Committee (IRC), and the Allegheny County Department of Human Services (DHS). I have presented my work at the International Sociological Association forum in the Urban and Regional Development Committee, the International Conference of Urban Affairs, and the Krueckeberg Doctoral Conference in Urban Studies, Urban Planning, and Public Policy. My research has received funding from the Zolberg Institute on Migration and Mobility, the Graduate Institute on Design Ethnography and Social Thought (GIDEST), the Robert L. Heilbroner Center for Capitalism Studies, and the Tishman Environment and Design Center at The New School.

operations, bureaucratic procedures, and indicators of the System’s care infrastructure. I interviewed twentyone workers, from policy makers and high-ranking officers to street-level bureaucrats. I also analyzed the indicators used to develop and implement this policy. Extending my focus beyond the effects of the System of Care on citizens and beneficiaries, I ask: How did the neoliberal and patriarchal local state in Bogotá end up developing a feminist and popular urban system of care to redistribute, recognize, and reduce unpaid housework? And what is this new care infrastructure doing to the local state in Bogotá?

I begin by tracing the genealogies of the feminist movement, technocracy, and public infrastructure in Bogotá I describe how feminist activists are infiltrating strategic positions within the state’s technocratic apparatus (taking over expertise roles, indicators, and infrastructures) to promote alternative temporalities, proximities, and moral economies in governance, such as those related to care, housework, chores, and emotional labor. I propose the concept of a post-technocracy to describe a sophisticated technical system of governance that no longer pretends to be apolitical and does not aim for the typical technocratic goal of streamlining rational decision-making. Instead, the feminist post-technocrats of the Women’s Affairs Office in Bogotá explicitly seek to vindicate feminist discourses, expand the state’s political sensibilities, transform the political coordinates of governance, and disorient longstanding “productive” state plans in light of emerging daily “re-productive” needs. Analogously to how caring about someone often involves not only doing something for that person but also being in a constant state of awareness for new needs and rapidly adapting to them, I show that the care-focused state suspends itself in a continuous state of awareness and rapid adaptation to any shift in its population’s needs. In Spanish, this state of awareness of “caring about” is called being pendiente: waiting, or pending, without certainty of when or for what purpose you will be called.

Each chapter of the book describes a technical mechanism through which care unfolds within the state.

(1) “Rehearsal infrastructure”: government buildings that improvise, develop, and repeat their care services and spaces depending on emerging daily necessities.

(2) “Care expertise”: knowledge that expands or constrains the nation-state production frontier to include or exclude activities and notions of value within the economy. For example, if housework is an economic activity, what exact practices fall into this new jurisdiction of work? Should calling your parents to check in on how they are doing be considered trabajos de cuidado no remunerado (“unpaid care works”, as the Women’s Affairs Office calls them)?

(3) “Smuggling bureaucrats”: activists who work for the state and inscribe emotional considerations, inclusive language, daycare service, and other care practices within typically dry bureaucratic procedures.

(4) “Refracted metrics”: care indicators that change their assumptions and meanings depending on political conjectures, producing images of populations and territories that are ambiguous and less flat.

These concepts and mechanisms deepen our understanding of infrastructure, expertise, bureaucrats, and indicators within the state, and they also showcase models through which social movements effectively shape the state’s architecture and operations.

Throughout these chapters, I show how care within the state suggests other temporalities of state behavior (e.g., improvising due to unexpected care needs), proximities (e.g., the state teaching men how to tie a ponytail for their daughters), and moral economies (e.g., care beyond kinship, markets, or state protection) that are transforming the relationship between the state and civil society. Therefore, my thesis concludes that care infrastructure disorients the state by proposing new political coordinates. This is not necessarily about a regime change (though it could lead to that), but about adding nuances, dimensions, or axes to the current political landscape, which makes the state see everything differently

For example, in Bogotá, a city with a population of eight million, treating domestic care activities as work or production rather than leisure or consumption led the local state to suddenly recognize two million new fulltime workers, mostly women. All the “housewives” and “stay-at-home moms” were now considered productive workers. Under this revised view of the population, the state became disoriented and had to reconsider all its social, economic, and cultural policies under these new assumptions. I show that this revision was not just a one-time matter but is a permanent aspect of care infrastructure, which, rather than only proposing a new political order, continually questions the existing one

Alongside thick descriptions, I present a critical revision of the conventional readings of care as a tool for the state to reproduce, sustain, repair, and socially protect its territories and populations. Through these analyses, I reveal how the emerging care infrastructure operates as a terrain of political struggle, vindication, and imagination, with kitchens and laundromats serving as creative and productive spaces rather than exclusively reproductive ones.

The importance of this research lies in presenting a model from the global south on how nation-states can leverage care infrastructure to learn and adapt during times of political disorientation. This ability to adapt is especially important during times of globalization, pandemics, and climate change, when the unfamiliar, outof-place, and unexpected are not the exception but the norm.

The public laundromat provides free drop-off, laundry, and folding services. A registration list opens once a week to reserve a time slot. People can bring up to 20 kilograms of clothing, but underwear and bed linens are not permitted. The laundromat is situated inside a community center that also offers around 50 other care spaces and services, all at no cost. There are 25 such centers in Bogotá.

In addition to developing a social science theory of the relationship between the state and public care infrastructure, this book also serves a descriptive aim, depicting a series of unfamiliar and queer scenes in governance:

• A maid as a vice-president of a country.

• Domestic workers as policy experts.

• A new ecology of indicators devoted to measuring housework, chores, and emotional labor

• Feminist activists in bureaucratic positions.

• Inclusive language in state services.

• New typologies of public and popular infrastructure, such as soup kitchens and public laundromats.

• New public institutions, such as a school of care for men that teaches them how to do a ponytail, sew a shirt, or talk about difficult emotions with their sons.

• A government office with hundreds of experts, bureaucrats, and politicians all of them women.

This project has been funded by the Graduate Institute of Design, Ethnography, and Social Thought (GIDEST) and the Robert L. Heilbroner Center for Capitalism Studies at the New School for Social Research.

2. Geographies of Care and Immigration

My second research project is titled “Geographies of Care and Immigration in New York City (NYC) ” This research is motivated by three characteristics of NYC. First, the city’s intensive use of space fosters the overlap and concentration of care infrastructure. Second, New York is exceptionally multicultural and globalized, with more than 160 languages spoken within its urban perimeter meaning it also hosts numerous ways of caring and care relationships that extend beyond national borders. Third, during the COVID-19 pandemic a care crisis that both deepened and disoriented our sense of geography the city performed poorly compared to others worldwide, and immigrant neighborhoods were disproportionately affected by this crisis. In this context, I ask: What is the spatial distribution of care within New York City (supply, demand, and infrastructure)? (ii) How do these multiple and multicultural layers of care relate to each other? and (iii) How did immigrant families navigate these geographies during and after COVID-19?

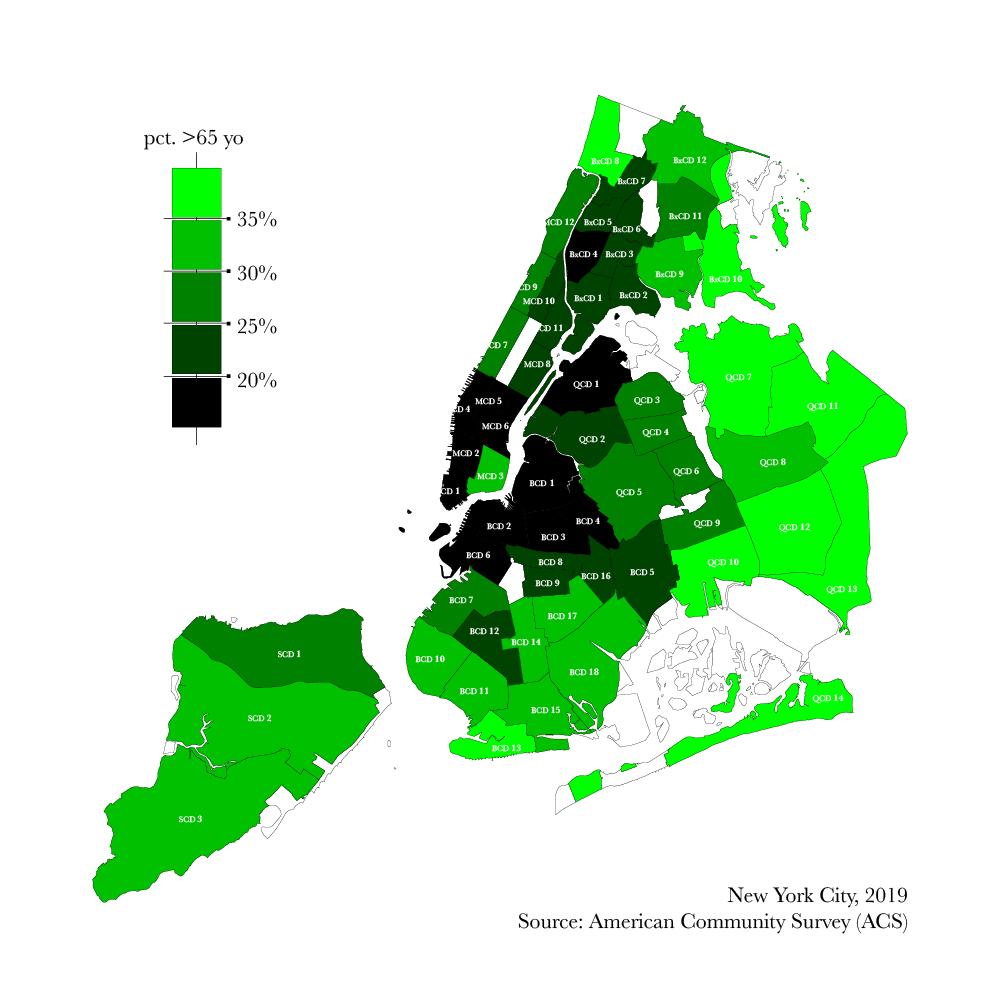

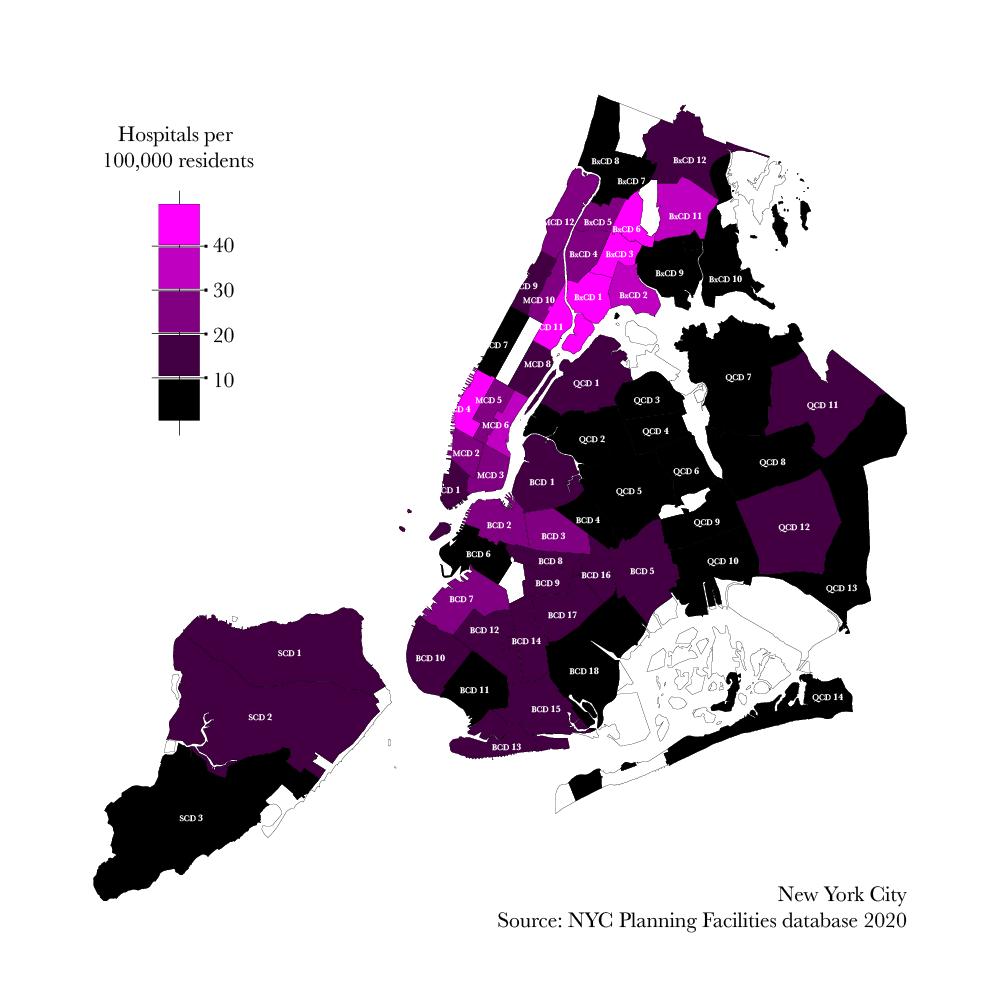

Together with my coauthor Oscar Sosa López, we conducted two years of fieldwork in New York City (NYC). We collected over 1,200 surveys from mostly Hispanic NYC residents about their care spaces and routines. Using the American Community Survey and the NYC Facilities Information, we created a geographic information dataset that includes care infrastructure (public schools, hospitals, libraries, and residential units), care demand (children and older adult populations), care supply (care workers’ residences, such as nurses, maids, and schoolteachers), and immigrant communities (foreign-born residents). Finally, we conducted 20 semistructured interviews with immigrant caregivers to explore their experiences with housework, childcare, healthcare, and the pandemic.

We are preparing three articles for submission to Cities, the Journal of Urban Affairs, and the Zolberg Institute Working Paper Series, respectively. The first, “Geographies of Care, Immigration, and COVID-19: A Spatial Contradiction in New York City,” focuses on the spatial distribution of care and immigration. We describe a phenomenon we call a spatial contradiction of care: the city’s care infrastructure depends on immigrant labor yet systematically neglects immigrant neighborhoods, leaving the city vulnerable to recurrent care crises. We identify specific areas of the city care black holes that consume most of the city’s care infrastructure and labor, threatening its sustainability.

The second article, “Entangled Care in Immigrant Queens: A Lexicon for Care Dynamics in the PostPandemic,” explores complex scenarios where a myriad of care practices and ethics concentrate spatially and temporally. Instead of concentrating on a taxonomy of the different care spaces, we focus on understanding the relationships among them what we call care-to-care interactions. We describe the circumstances under which care spaces conflict, complement, or supplement each other. This helps us identify the factors and conditions that contribute to a healthy care system or its burden.

households

Notes: QCD3 and QCD4 are the two community districts known as Immigrant Queens, characterized by a high proportion of older adults and low hospital density. Community districts, such as MCD4 (Hudson Yards’ area), are what we call care black holes characterized by a low proportion of care demand (older adults) but a high proportion of care infrastructure (hospitals).

The third article examines the care routines among Hispanic families in Queens, NYC. We describe and explain interesting phenomena, such as new moral economies of care that go beyond kinship and market logics, and an apparent decrease in the gender gap of housework distribution.

This project has been supported by NYC Health + Hospitals and Zolberg Institute on Migration and Mobility at The New School for Social Research.

3. Research Agenda

My goal is to continue expanding the field of political economy of public care infrastructure. In this final section, I share some of the new research avenues I am currently pursuing.

Public bathrooms, olfactory landscapes, and the new public Between 2020 and 2022, as a policy practitioner, I was responsible for Bogotá’s Public Bathrooms Policy. In this role, I developed a public dataset characterizing around 350 public restrooms in the city, interviewed dozens of government workers responsible for cleaning and managing these facilities, and developed urbanist interventions for making the bathrooms more accessible. Since then, I have been intrigued and concerned by the myriad of phenomena that intersect in this scarce infrastructure: police brutality against the homeless population; olfactory landscapes in the city; imaginaries of the public and the intimate; notions of dignity, right to the city, and fundamental rights; street vending and gig economies; gender-based violence; and class-based and racial segregation in the city. Therefore, I am studying What role do public bathrooms play in modern cities? And what do they reveal about public space imaginaries?

Caring like a Man: Masculinities, Social Inequalities, and Climate Change. In a previous project, “Who Cares for the Environment? Recycling and Composting in Bogotá,” I showed that men are more likely to engage in environmental household activities such as recycling, composting, and taking out the trash (wastemanagement-oriented) than in other domestic tasks like cooking, cleaning, or washing dishes. Since then, I have been intrigued by the paradoxical relationship between hegemonic masculinities (which view care as feminine) and environmental housework (like gardening, recycling, composting, or walking a dog) By studying masculinized environmental care jobs, such as waste pickers and recyclers in Colombia and gardeners in the U.S., I aim to analyze how environmental care has become a masculine practice and how gender roles may be reconfigured within non-human care relationships.

Post-humanities, Cybersecurity, and Care. Dr. Chitra Marti (an economist) and I are studying the political economy of cybersecurity in digital care markets (dating apps, medical records, and AI relationships), with an emphasis on the relationship between care markets and cybercrime. To do so, this project bridges the literature on industrial organization, technology and operations, surveillance capitalism, and feminist science and technology studies to explore the dialectical relationship between “care” and “security” in times of big data and artificial intelligence. Our initial guiding question is: How do “care” and “surveillance” intersect within the digital marketplace, where care is commodified and enabled by large-scale data collection?