0–Personal Statement1

0–Personal Statement1

By Carlos J Celis, celic265@newschool edu 12/18/2023

In this project, I focus on informal caregiving spaces. On the one hand, with caregiving, I refer to all the activities performed to sustain life: cooking, cleaning, dishwashing, taking care of kids, recycling, composting, gardening, etc. On the other hand, with informal, I refer to its unpaid character. The following paragraph points out some helpful care definitions to frame this problem space:

"Berenice Fisher and I defined it [care] some time ago, 'in the most general sense, care is a species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue, and repair our world so that we may live in it as well as possible That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment [emphasis added], all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web '" (Tronto, 2015, p 3)

“Research on care jobs to date has defined them in terms of an occupation/industry overlap consistent with services that develop human capabilities, often requiring personal interaction (England et al. 2002; Budig and Misra 2010; Duffy et al. 2013). Direct care jobs have been defined more specifically as jobs in which the quality of the service provided is likely to be affected by the care provider’s concern for the well-being of the care recipient Indirect care jobs entail provision of services necessary for direct care (Folbre 2012)” (Folbre & Smith, 2017, p 3)

“ key set of social capacities: those available for birthing and raising children, caring for friends and family members, maintaining households and broader communities, and sustaining connections more generally” (Fraser, 2016, p 99)

I find Tronto's (2015) definition intriguing since it highlights a particular type of care I would like to explore in this course: environmental care. According to her definition, environmental care refers to all those activities performed to maintain, continue, and repair our environment For instance, recycling, composting, gardening, etc. This typology of care permits discussing care epistemologies, ethics, and praxis in uncommon scenarios I want to call attention to four of those particularities of environmental care:

• In many Western patriarchal societies, care is performed within the household. The house provides the infrastructure and the space required to perform this labor. For instance, a kitchen has pots, food, and gas that enable cooking In contrast, most environmental care is performed in outdoor spaces: streets, community gardens, parks, etc.

• Nuclear family paradigms are very influential in human direct and indirect caregiving practices. Caring for an elderly adult is usually the family's responsibility–sons or daughters. Not having a family or close relatives puts the elderly adult in a context of vulnerability In environmental care, the care recipient can be the pigeons in a park or a tree in the street. It is not that clear who is responsible for providing care This opens the doors to other logics and scales of care, for instance, community care labor.

• Taking care of a park requires various labors and types of knowledges: mowing the grass, taking care of flowers, planting trees, building a greenhouse, etc. In this context, care is required to be collective instead of individual. Coordination between caregivers becomes essential.

• Global warming is an urgent multidimensional matter to attend to. However, it remains under the knowledge and expertise of environmental studies. Environmental care builds an interesting bridge between the climate crisis and health and care affairs

Informal caregiving labor is an urgent matter to address (1) There is an enormous gender gap–women mostly perform it. (2) It is an essential activity for productive labor but remains unpaid. Nancy Fraser (2016) describes it as capitalism “free-riding” care. (3) There is a huge worldwide demand for care, “in 2015, there were an estimated 2.1 billion people worldwide in need of care, predominantly children (the overwhelming majority) and the elderly” (Dowling, 2021, p. 4)–not including environmental care demand. (4) Grassroots caregiving systems are under constant threat. For instance, Mindy Fullilove (2004) describes how urban renewal policies affect community care systems in the United States Silvia Federici (2012) presents the case of the World Bank and IMF structural adjustment programs undermining care systems in the Global South. (5) Global care chains, the commodification of care, the list is long…

The previous elements are part of what scholars have called the care crisis. I intend to add those elements to the well-known list of concerning elements of the climate crisis: deforestation, production of waste and trash, affectation of wild nature in urban environments, etc (environmental

3 care crisis?). In this context, I want to address the following design question: How might we maintain, continue, repair, and strengthen environmental care systems?

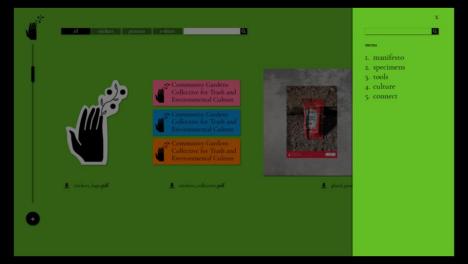

The ‘Community Gardens Collective for Trash and Environmental Culture’ is an initiative that aims to identify and connect community gardens in New York City The collective has two main objectives: on the one hand, transforming New Yorkers' daily interactions with the trash so they produce less and recycle more. On the other hand, recognizing and strengthening Community Gardens' capacities for trash management, for instance, by doing compost or environmental education.

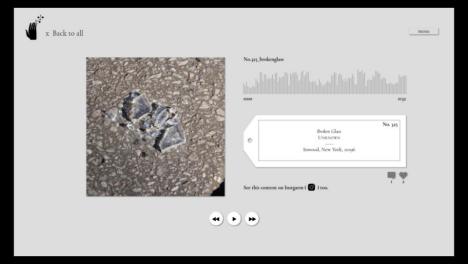

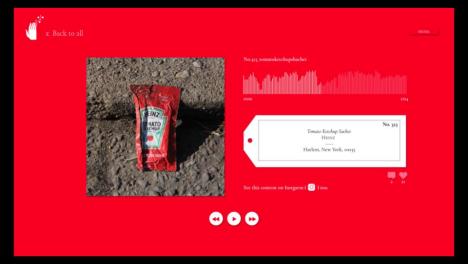

To achieve its objectives, the collective works on five dimensions: (1) a “manifesto” that presents and shares the principles and values for healthier and more caring relationships with trash and community gardens in New York City; (2) a collection of stories (audio and photography) that reveal how rich, complex, and relevant are the trash ecosystems; (3) a library of tools and methods for community garden’s volunteers who are interested in performing “care for trash” activities: composting, recycling, and repairing; (4) spreading the culture of taking care of trash trough graphic design items: stickers, pictures, and illustrations; lastly, (5) mapping the community gardens that are working on trash management (composting, recycling, or repairing) and sharing their contact information, so they can reach new volunteers.

Community gardens in New York City are small ecosystems that contain a myriad of caring relationships: bees pollinating plants, older adults watering plants, intergenerational groups composting and weaving friendship relationships, community organizations working for environmental justice, siblings reading a book, or neighbors taking a rest for breathing and contemplating the birds. Arguably, these gardens operate out of the market logic–as most public care infrastructure (public libraries, parks, or community centers). Of course, they are related and affected by markets, but the connection is not direct. This means they are not selling products or raising

profits.

2 Adapted from the final video’s script 3 Adapted from the Research Proposal Assignment 09/28/2023 4

It also means the private property logic does not apply directly to them. The flowers in a garden do not have an owner. The neighbors who bring food scraps for compost do not pay for the service, and the compost is not for sale. These dynamics are among the reasons why community gardens are rich in caring relationships Nevertheless, they also represent significant challenges for their sustainability: they depend on voluntary work, donations, articulation with the government, and establishing social and informal agreements with the community and neighbors

Therefore, I want to understand how community gardens interact with their constitutive outside How do they get new volunteers? How do they reach agreements with the neighbors? and how do they establish the spatial limits of the garden?

The research process is based on a study case. I am working with a community garden in Harlem: William B Washington Memorial Garden, 321 W 126th St. As mentioned, my focus is on the edges of the community garden. The places and spaces where the socio-technical infrastructure of the community garden interacts with the outside: neighbors, the government, other gardens, etc. As an entry point, I am interested in the fences of the garden: this infrastructure defines the physical limits of the space; it serves as a place for informing the community about the operations of the garden (the name of the garden, the schedule, the activities, etc.); and represents a barrier to access–most of the time the community garden’s fence and entry are closed with locks.

Besides the mentioned research question, a design question emerges from this context: How might we design new infrastructures for the edges of the garden that nudge new caring relations and sustain/strengthen the existing ones?

To data collection methods were secondary sources, semi-structured interviews, ethnography, and community engagement activities Table 1 presents the protocol for interviews, and Table 2 describes the community engagement activity.

Table 1. Protocol Semi-structured Interview

4

I am Carlos Celis, a designer and Ph D student at The New School I am researching community gardens in Harlem, NYC I am motivated by acknowledging the relevance of community gardens as caring community systems: a place for socialization, a space for taking a breath and rest, a playground for kids, and more. I'm interested in the stories, concerns, expectations, and visions for community gardens in Harlem. In this sense, I would ask you some open questions

regarding this issue It would be a conversation of at most 30 minutes If you feel uncomfortable with questions, you can always stop the interview or skip a question If you allow me, I would like to record this conversation This would help my process of analysis of the information The discussion will always remain private, and I am the only person accessing the recordings The recordings will be transcribed using a pseudonym, stored, and erased after one year. Fragments of the transcript using a pseudonym may appear in a final report.

INTRODUCTION

(1) Tell me about you (2) Tell me about your story in Harlem

MEMORIES

(3) Could you tell me about a meaningful memory that involves a community garden, park, patio, or urban green area? (4) Where is that garden? (5) Why is it meaningful? Why do you care about this garden? (6)What element of the garden do you remember the most? And why?

PRESENT

(7) Tell me about community gardens in Harlem (What do you know about them?) (8) Do you visit any of them? How often? Why? (9) What are your biggest concerns about community gardens in Harlem? (10) Have you noticed any conflict/tension/problem between the gardens and the neighbors? (11) What do you think is the role of community gardens in Harlem?

VISIONS

(12) How might community gardens become more valuable and meaningful? (13) How might we care for community gardens in Harlem? What should we do? (14) How might community gardens care for us? What should they offer us?

ACTIVITY

Informal conversation with friends, neighbors, and pedestrians near the garden I ask them if they have trash/garbage in their pockets or bags Then I ask them the following questions:

(1) What is it?

(2) Where did you get it?

(3) What is its story?

(4) Why do you want to get rid of it?

ACTIVITY #2

Informal conversation with friends, neighbors, and pedestrians near the garden.

(1) Showing a picture of trash

(2) Asking “What do you think is the story behind it?”

Regarding the interviews, I talked with: Judy, the leader of the William B. Washington Community

Garden (WBWCM); Caren, my friend and volunteer of the WBCCM; Andrew, who works on connecting farm markets with community gardens; and Carlota, my friend, and a trash collector in Brooklyn.

The following paragraphs summarize the insights of the research process, they are organized under four titles: ‘Fragmented Ecologies,’ ‘Enrolling: alone vs with friends,’ ‘The thin line between care and protection,’ and ‘Maybe littering is not a bad thing…’

Insight #1, Fragmented Ecologies: In the same street, there are three community gardens W Washington, CEP, and Saint Nicholas Miracle. They are home for similar activities: gardening, leisure, composting; and similar challenges too: littering, requiring volunteers for maintenance, and lack of 6 resources There are some connections from the management perspective (for instance, sharing gardening tools); however, they are disconnected spaces from the neighbor's point of view. Insight #2, Enrolling: alone vs. with friends: Friendship is relevant for enrollment and permanence of volunteers It provides a social motivation for performing care labor, which sometimes is difficult–composting is physically demanding. Hence, people who enroll alone or does not already have a connection with a garden member have a more difficult experience This represents a barrier for enrollment.

Insight #3, The thin line between care and protection: For the volunteers and garden members, caring for the garden represents labor, time, and resources. This effort invested in the garden creates an affective bonding with the space and a sense of responsibility for it. This relationship can quickly end up in protective behaviors—affecting potential new relationships with neighbors.

Insight #4, Maybe littering is not a bad thing… Of course it is bad, but currently, it seems to be the only interaction most neighbors have with the garden. The space only opens to the public a few moments of the week and participating as a volunteer is open to anyone; nevertheless, it demands time and commitment (so it is not available to everyone).

Table 3 presents a design opportunity for each of the insights

Title Design opportunity (how might we questions)

Insight #1, Fragmented Ecologies How might we build connections between the gardens and provide a expanded experience to the community?

Insight #2, Enrolling: alone vs with friends

Insight #3, The thin line between care and protection

Insight #4, Maybe littering is not a bad thing…

How might we connect the gardens with already existing groups so people do not enroll alone? How might we design a volunteer enrollment experience that guarantees social connections, even before day 1?

How might we shift from protective behaviors to caring behaviors?

How might we make the only interaction with the garden (littering) meaningful and caring?

As mentioned in the first section of this document, to illustrate how the ‘Community Gardens Collective for Trash and Environmental Culture’ operates, I designed a website that includes the five key dimensions of the collective.

5–References

NYC Planning (2023). Community District Profiles, Central Harlem. https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/manhattan/10

Dowling, E. (2021). The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How Can We End It? Verso Books.

Federici, S (2012). Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle PM Press

Folbre, N., & Smith, K. (2017). The wages of care: Bargaining power, earnings and inequality. Working paper series, 430, 1–42.

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1306&context=peri_workingpapers

Fraser, N. (2016). Contradictions of Capital and Care. New Left Review, 100, 99–117.

Fullilove, M. (2004). Root shock. How tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America, and what we can do about it. New York: New Village Press

Herrero, Y. (2020). Ecofeminismos para tiempos de crisis. Pabellón 6 Editorial. Tronto, J. C. (2015). Who Cares? How to Reshape a Democratic Politics. Cornell University Press.