• AI and nonviolent communication

• Dispatches from Moldova, Cameroon, Brazil, Pakistan, and Serbia

• Awards honor top peace journalists

• AI and nonviolent communication

• Dispatches from Moldova, Cameroon, Brazil, Pakistan, and Serbia

• Awards honor top peace journalists

Cover--At the Thessaloniki summer media academy, Prof. Sherri Hope Culver (top), Social anthropologist and photojournalist Dimitrios Bouras (botton left), and participant Priya Shaw (bottom right, center of photo). Top, left photos by Giannis Triantafyllidis.

The Peace Journalist is a semiannual publication of the Center for Global Peace Journalism at Park University in Parkville, Missouri. The Peace Journalist is dedicated to disseminating news and information for teachers, students, and practitioners of PJ.

Submissions: We are seeking shorter submissions (600 words) detailing peace journalism projects, classes, proposals, etc. We also welcome longer submissions (1200 words) about peace or conflict sensitive journalism projects or programs, as well as academic works from the field.

Deadlines: March 3 (April edition); September 3 (October edition).

Editor: Steven Youngblood, Director, Center for Global Peace Journalism, Park University

Proofreading: Ann Schultis, Park University emerita faculty

Contact/Social Media: steve.youngblood@park.edu

Twitter/X- @PeaceJourn

Facebook- Peace Journalism group

14 PJ showcase

From Uganda: Tech, deaf citizens

16 Serbia

18 Ukraine

20

24 Kosovo

Peace Journalism is when editors and reporters make choices that improve the prospects for peace. These choices, including how to frame stories and carefully choosing which words are used, create an atmosphere conducive to peace and supportive of peace initiatives and peacemakers, without compromising the basic principles of good journalism. (Adapted from Lynch/McGoldrick, Peace Journalism). Peace Journalism gives peacemakers a voice while making peace initiatives and non-violent solutions more visible and viable.

A number of valuable peace journalism resources, including curriculum packets, online links, as well as back issues of The Peace Journalist can be found at www.park.edu/peacecenter.

The Center for Global Peace Journalism works with journalists, academics, and students worldwide to improve reporting about conflicts, societal unrest, reconciliation, solutions, and peace. Through its courses, workshops, lectures, this magazine, blog, and other resources, the Center encourages media to reject sensational and inflammatory reporting, and produce counter-narratives that offer a more nuanced view of those who are marginalized—ethnic/racial/ religious minorities, women, youth, and migrants.

“Incorporating the principles of peace journalism and nonviolent communication into AI is essential for a more harmonious and empathetic future. Peace journalism encourages AI to prioritize balanced and constructive reporting, steering away from sensationalism

and bias. This shift in focus can help reduce tensions and promote understanding, fostering a more peaceful society.

Nonviolent communication principles, emphasizing empathy and effective dialogue, can be integrated into AI systems. By embracing these principles, AI can contribute significantly to conflict resolution and peacebuilding. In summary, infusing AI with the values of peace journalism and nonviolent communication is vital in building a

Dr Vedabhyas Kundu (page 10) is the Programme Officer in Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti, New Delhi, India. Munazah Shah (right) is a Senior Broadcast Journalist based in Hyderabad, India.

more empathetic, informed, and harmonious world, where technology supports rather than hinders...peace and understanding.”

What are we to make of this passage, written by the AI application Chat GPT?

Honestly, it’s not bad, though the writing is a bit wooden. It does hit the main point, which is that AI needs to “align with human values” and reflect the principles of nonviolent communication. That’s the same point made by our human writers on page 10. I hope this is possible, but fear that the technology will do the opposite, empowering divisiveness, partisanship, and hate speech. We shall see.

--Steven Youngbloodtion, Oil and Gas, Agriculture and Technology, innovations and renewable energy.

Dr. Nikos S. Panagiotou (page 4) is Associate Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Media Communication, Aristotle University. He has been a visiting Professor at APU University, Japan and a visiting professor at Deutsche Welle, visiting professor at Sabanci University.

Steven Youngblood (page 6, 24) is editor of The Peace Journalist, director of the Center for Global Peace Journalism at Park University, and 2023-24 Fulbright Scholar in Moldova.

Marcelle Chagas (page 8) holds a Journalism Master degree in Communication from Universidade Federal Fluminense. She is the eneral coordinator of the Network of Journalists for Diversity in Communication

and of the Gender, Race and Territoriality Observatory in Science.

Dr. Maha Bashri, (page 12), who holds a journalism Ph.D. from the University of South Carolina, is an Associate Professor of Communication at the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU). Her research delves into political communication and digital technology.

Willy Chowoo (page 14) is a Uganda’s Multimedia and investigative Journalist working with Choice Fm Radio in Gulu City. Chowoo

Simona Mladenovska (page 16) is Balkans Civil society Development Network’s Policy and Advocacy Officer. She leverages her MSc in New Media and Social Networks and BA in Political Science to drive the network’s extensive research and

analysis efforts focused on the civil society enabling environment in the Balkans.

Lorenzo Fiorito (page 18) (left) is a lawyer and human rights advocate in London, UK. Combining practical and academic experience with the UN, WTO, and the World Bank. Dr. Senthan Selvarajah (right) s Co-Director at the Centre for Media, Human Rights and Peacebuilding, UK, CEO at the Gates Foundation, UK, an Academic Tutor for Unicaf and Liverpool John Moores University, UK. reports majorly about Climate Change,

conserva-

Lubna Jerar Naqvi (page 20) is a journalist, social media expert, social media security for journalist trainer, women rights activist, gender and harassment trainer, and media trainer in Pakistan. She advocates for human rights, focusing on women’s and children’s rights.

Rose Obah Akah (page 21) is the national coordinator for the Cameroon Community

Media Network, and a trainer and specialist in peace journalism.

Andrea Muraskin (page 22) is a freelance journalist based in Boston. She is the producer of the Making Peace Visible podcast with War Stories Peace Stories, and writes about health for NPR.

The evolving dynamics at both the global and local levels underscore the pressing need for continuous education among journalists. In an era where journalists increasingly find themselves tasked with covering crises and conflict zones, the demands of the public have also evolved.

Media professionals now find themselves navigating various platforms to convey information effectively to their audience. But in the midst of these changes, how can journalists stay abreast of developments while retaining their integrity and objectivity?

For the seventh consecutive year, the Thessaloniki International Media Summer Academy (THISAM) has played a pivotal role in addressing these challenges. This year’s program, titled “New Trends in Communication, Media, and Journalism,” brought together a diverse and passionate community of individuals dedicated to the transformative power of journalism. Participants included early-career journalists, students, media entrepreneurs, scholars, NGO leaders, and industry luminaries.

Over the course of the week, THISAM fostered an environment of innovation, idea sharing, and the development of novel business strategies. This was achieved through mentorship and collaboration across career levels, emphasizing a hands-on, interactive, and interdisciplinary approach.

Participants had the unique opportunity to receive training on diverse topics and explore new practices and approaches. Upon program completion, they crafted articles and podcasts based on THISAM’s teachings. Those who successfully submitted their projects earned 3 ECTS from the

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, with these projects being showcased on the program’s official website (www.joursummerschool.org).

The spotlight was cast on marginalized groups and the principles of peace journalism through two documentaries from Canada and a European program.

Concordia University (Canada) Professor Aphrodite Salas presented details about a groundbreaking documentary project she and her students completed with an Inuit community in Inukjuak, Canada, which is 1,472 km from Montreal. In partnership with the indigenous community, they produced two 12-minute documentaries, one in the voice of an elder detailing the group’s mistreatment at the hands of the Canadian government, and the other about a hydroelectric project that will end the community’s dependence on environmentally-unfriendly diesel fuel.

Then, THISAM featured a presentation about the “Invisible Cities” project, which is a collaborative project involving journalism departments from Greece, the Netherlands, Belgium, Georgia, Croatia, and Romania. This

cross-border endeavor captures the stories of city dwellers who often go unheard due to societal perceptions and labeling. Termed ‘Invisible people,’ their histories remain unknown to us. Guided by their professors, students from the aforementioned universities interviewed residents of Antwerp in 2019 and Thessaloniki in 2022. Through journalistic narratives and multimedia content, they shared the personal experiences of these ‘different’ individuals within the city and society.

The impact of images and their influence on audience perceptions was a central topic of analysis. Participants delved into the interpretation of images from conflict zones, gaining insight into how these images are instantly, and often subconsciously, interpreted. Through hands-on exercises, their skills were honed, prioritizing the selection of photographs aligning with the principles of Peace Journalism.

Throughout the program, significant attention was devoted to how events are covered, content structuring, and word selection. Peace Journalism principles served as the guiding

ethos of THISAM in this context. This effort culminated in presentations by Professor Steven Youngblood, who explored transnational issues such as international conflicts and population movements.

The PJ sessions included a discussion about how peace journalists should commemorate the past, especially painful or contested events. Youngblood tasked the participants to come up with a plan on how they would advise Greek media commemorating the 50th anniversary in 2024 of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. One emotional participant said she could not be objective about this, since the invasion displaced her family. Other participants said that they would avoid bloody images and sensational wording when commemorating this anniversary. To these sound tactics, Youngblood advised to remember the past but not dwell on it, and to look forward rather than only looking backward.

The discussions about media and refugees triggered another passionate student who said she’s mad about the way media marginalize refugees and the way refugees have been treated by governments. We discussed the tragic sinking of the refugee boat off of the coast of Greece, and the dearth of coverage this received compared to the contemporaneous implosion of the submersible exploring the wreck of the Titanic. (See page 13).

Other expert presentations delved into the vital aspects of debunking and source verification within journalism. Emphasis was placed on the necessity of fact-checking and comprehensive source examination. Reporters were encouraged to challenge official propaganda and seek information from a multitude of sources.

Year after year, THISAM prioritizes media literacy and the role of journalists in public education. Media literacy

is regarded as a tool for peace, as an informed public can contribute to constructive, peace-oriented communication in times of conflict.

Another key theme at THISAM was the integration of new technological developments and AI in newsrooms. Examples were provided, and workshops conducted to equip journalists with the knowledge and skills to harness these technologies effectively.

The program also delved into media systems and their influence on the work of media professionals. Initiatives and tools from NGOs and journalists’ associations were presented, offering practical solutions to everyday challenges.

The safety of journalists and communication professionals, both in

At the sumer media academy, Prof. Aphrodite Salas discusses empowering indigenous storytellers (top), while students simulate listening to a podcast.

physical and digital realms, remained a paramount concern. Participants received expert training in encryption, secure file sharing, and safeguarding electronic devices from potential cyber threats.

THISAM’s collaborators included universities from Greece, South Korea, China, and Serbia. The academy also enjoyed support from the European Parliament Office in Greece, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Greece & Cyprus, Freedom House, CISCO-International Center for Digital Transformation & Digital Skills, the Macedonia-Thrace Union of Journalists, Univ. of Macedonia Press, and Xanthi Tech Lab.

From 5-12th of July 2024, we eagerly anticipate the next Thessaloniki International Media Summer Academy.

--Nikos S. PanagiotouWorldwide, the challenges faced by media are similar. The latest research on these challenges, and how they can be overcome by media, were at the top of the agenda at the Global Media and Culture conference on July 13 in Thessaloniki, Greece.

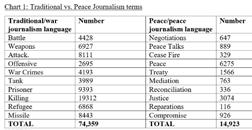

within the “Russia Ukraine War” results for a word or term like “battle.”

(See chart).

Prof. Nikos Panagiotou of the Aristotle University, the sponsor of the conference, laid a foundation for the days’ discussion by presenting media trends and challenges. Among the insightful statistics he cited: On average, consumers spend 8 hours and 10 daily on digital media; and social media consumption rose 61% between 2012 and 2020. He also laid out challenges for the media, including news avoidance (53% avoid news altogether or turn the channel when news comes on) and negativity bias in news reporting. Dr. Panagiotou finished by discussing antidotes to what ails media, including collecting better audience data and changing media delivery

Other presentations included:

--Prof. Christoph Schmidt (DW Academie), who enlightened the conference about constructive journalism, which he defined as “yes we can journalism” that includes elements that empower audiences. He discussed his survey of international media leaders on CJ, who indicated their preference for CJ-style stories that present information of “high importance” to society. Respondents said this makes CJ media more sustainable than traditional media.

Carolyn O. Arguillas of Mindanao, Philippines, was awarded the 2023 Luxembourg Peace Prize in the catagory of peace journalism.

Arguillas has emerged as a visionary leader in the field of Peace Journalism. She served as Editor-in-Chief of MindaNews until June 1 this year and now heads its Publications, Archives, and Library. She also serves as its Special Reports Editor.

With her unwavering commitment to journalism ethics and her contributions to constructive and inclusive media coverage, Arguillas has become an influential figure in the pursuit of peace in the Philippines.

Prof. Nikos Panagiotou of the Aristotle University opens the media conference in Thessaloniki.

models. This, of course, could include peace journalism.

I presented research I conducted on peace journalism content in Russia-Ukraine war reporting. I analyzed the words used in thousands of stories, looking for usage that would indicate either PJ or its opposite, traditional journalism. I found that traditional war language (missile, attack, killing) outnumbered PJ/peace language (reconciliation, treaty, negotiation) by 5 to 1.

The research wad done on the Nexis Uni (formerly LexisNexis) database. I analyzed the prevalence of violent, emotive, inflammatory language, and peace language, in news content, specifically newspapers, magazines/journalists, newswires/press releases, and broadcast transcripts for the month of March, 2023. For example, a search was done for “Russia Ukraine War,” then a second search done

--Profs. Cheng Chen Ching (Hallym University, South Korea) and George Athanasopoulos (Aristotle University), who discussed their study about how well university students in 4 countries understand fake news. The takeaway: students lack an operational definition of fake news, leading to a wide divergent of often poorly informed opinions. Especially interesting were statements made by Chinese students during the study’s focus groups. These statements include:

“There is no fake news. If you believe it, it’s true.” “Propaganda is actual, factual news.”

“Russia must have had a justified reason to start the war.”

--Evlambia Angelou (interpreter, independent researcher), who presented about translation in journalism and its important role in building meanings for audiences.

--Ionnia Georgia Eskiadi (PhD candidate, Aristotle University) presented about the movement from social media to immersive media (social gaming, virtual worlds, etc.), especially among young people. She said this has implications for new providers, although they have largely failed to make a large impact yet in this area. (The NY Times has dabbled in virtual reality, Eskiadi noted).

Conference attendees included students, academics, and journalists from South Korea, Kosovo, China, Netherlands, U.S., Canada, Serbia, and Greece. The full conference program is at https://joursummerschool.org/images/programs/THISAM_Conference_programme.pdf .

--Steven Youngblood

Over the past two decades, MindaNews under her leadership has earned recognition for its constructive coverage of peace efforts, fostering an environment of dialogue and understanding. It has played a significant role in achieving milestones in the country’s peace processes, including the signing of a peace agreement between the Philippine government and the Moro people in the southern part of the country and the passage of the Bangsamoro Organic Law.

Arguillas’s contribution to peace journalism has helped shape the media landscape towards a better reporting and understanding of Mindanao. Her commitment to responsible reporting combined with her unwavering dedication to peacebuilding, has made her an influential figure in the pursuit of a more inclusive society.

“Peace is a process and not a mere event. In reporting peace and conflict, knowing history and upholding human rights and justice are a must,” she said.

The award was presented at European Convention Center in Luxembourg on June 14. The prize is sponsored by the Schengen Peace Foundation.

--Luxembourg Peace PrizeNyongamsen Ndasi has been named the Peace Journalist of the Year during the Victoria International Media Merit Award -Viimma 2023 on Saturday August 12, 2023 in Limbe, Cameroon.

Ndasi said that the winning article was first published by The Peace Journalist. It was titled, “Peace Clubs Launched in Cameroon.” It was published later in The Post Newspapers and titled, “Peace Journalism: Cameroon’s Armed Conflicts, Hate Diatribes May End Tomorrow.”

On his Facebook feed, Ndasi writes, “This marks my third award that acknowledges and recognizes my contributions in Peace Journalism. This is dear to me for the fact that, the selection and vetting process were extra professional, tight and rigorous. The jury constituted journalism professors/PhD’s and internationally recognized journalism and media (members).”

While studying at the National Polytechnic University in Bamenda, Cameroon, Ndasi said he concentrated on three areas: Reporting to enhance peace, culture, and agriculture. He writes, “As Editor-in-Chief of The Cameroon Report newspaper, I focused the news angling on stories that spotlighted peace, culture, and agriculture.”

Ndasi notes that the beginning of his peace journalism career didn’t go smoothly. He writes, “I remember how my journalism colleague ‘attacked’ and criticized me. By practicing and promoting Peace Journalism, they accused me of armbushing Journalism...Today, the same colleagues who criticized my Peace Journalism works are now believers in Peace Journalism. The menaces of the armed crisis in the North West and South West Cameroon continue to expose the need for Peace Journalism.”

--Nyongamsen Ndasi

Data released from a study on gender inequality in journalism, produced by the Reuters Institute, indicate that of the 240 journalistic organizations in 12 countries, on average, only 22% of the leadership positions analyzed are held by women in 2023. This number drops to 13% in Brazil. With regard to race, Reuters also indicates a low presence of black and non-white ethnic journalists in leadership positions around the world. Only 23% of editors in the top 10 online and offline outlets in countries like Germany, the UK, South Africa and the US. are black or of other ethnicities. In Brazil, as in 2022, all the outlets in the sample have a white journalist as their main editor.

Known for its wide ethnic diversity, Brazil is made up of 56% of the population that identifies as Afro-descendant. However, despite this numerical representation, this portion of the population faces persistent social and economic inequalities resulting from a history of discrimination and exclusion. The legacy of structural racism is visible in areas such as education, health, employment, housing, and social justice, and is reflected in the field of communication.

Journalism is an important tool in the construction of social reality, and it is also a reflection of racial inequalities present in society. The way news is selected, produced, and presented can be influenced by unconscious bias and prejudice, and thus reinforces stereotypes, which can lead to a distorted representation of the reality of black communities. One of the main issues is the under-representation of black journalists in newsrooms and in prominent positions in the media.

The lack of diversity in newsrooms implies an absence of diverse perspectives and experiences, which

can contribute to limited journalistic coverage (in peace journalism terms, ignoring the voice of the voiceless) that is distant from the realities of black populations.

Given this scenario, the Black Journalists Network for Diversity in Communication, also known as Black Journalists or JP Network, has been formed to promote perspectives of a more inclusive and representative media through a collaborative system of action with the pillars of education, representation, opportunity, and advocacy as a strategy used to promote social, political, and legal changes in the communication field in negotiation with the Government of Brazil.

In 2018, Brazil held presidential elections that were highly polarized. Jair Bolsonaro, a former military man and far-right deputy, and Fernando Haddad, of the Workers’ Party (PT), faced each other in a second round, after being the most voted candidates in the first round. Bolsonaro was elected president, taking office in January 2019. During Jair Bolsonaro’s government in Brazil, there were several episodes of verbal aggression and attacks on journalists by the president himself and members of his government. These actions were widely criticized by press freedom organizations and raised concerns about respect for press freedom in the country.

The former president and members of his government frequently discredited the press. Bolsonaro made several offensive and insulting statements against journalists and media outlets. Furthermore, during the Bolsonaro government, a significant increase in the spread of misinformation and false news was also observed, especially on social media. Such practices

have raised concerns about the health of democracy and the fundamental role of the press in society.

Coming from a peripheral region in Rio de Janeiro, journalists followed with concern the narrative dispute that was strongly established during that period and that did not include the black population and their demands. Thus, through a group of messages, the Black Journalists were born. It was formed by black journalists from all over the country with the objective of making communication more diverse and representative. The group has more than 250 members (in 2023), and has developed guidelines to avoid ethnic and racial bias in reporting as well as collected a list of sources useful to black journalists.

To develop the organization, it was essential to have a team made up mostly of women from different parts of the country, including Aline Araújo (Rio de Janeiro), Sandra Roza (Minas Gerais), Maria Eduarda Abreu (Bahia), in addition to Eddie Júnior (São Paulo). All coordinate the management of reporting, social networks, diversity and inclusion efforts.

In the same year, the organization became the only representative of Brazil in the Panafrican Caucus of Journalists, an initiative of the State of the African Diaspora that brings together journalistic projects from around the world that are involved in promoting diversity and Pan-African values while ensuring that voices from the diaspora can be heard. In 2020, black journalists took a low-investment digital strategy course to qualify unemployed black journalists and members of civil society belonging to minority groups to develop their professional activities via the internet during COVID-19.

Continued on next page

The following year, the organization initiated the creation of the international conference of journalists from the African diaspora, which annually brings together journalists from underrepresented groups from around the world to discuss innovation in journalism. The event featured more than 30 journalists from Brazil, the United States, France, Cameroon, Burundi, the Caribbean, and Liberia.

The second edition of the conference had a hybrid format and took place in the East Zone of São Paulo, a periphery with communities that face challenges such as lack of adequate access to health, education, public transport, and security. Despite the lack of financial support, the conference is held with the aim of raising reflections and returning to society the rescue of the role of the press, the importance of journalistic credibility, the creation of new opportunities for global action among professionals, in addition to proposing new communication concepts that utilize inclusion.

The Black Journalists Network in 2023 joined the Clinton Foundation’s emerging leadership team. The program is highly sought after for its track record of training leaders and change agents in diverse sectors around the world. The organization is called a network of journalists because it refers to the practice of uniting efforts and knowledge between different individ-

uals, organizations or groups with the aim of achieving a common goal. The network of journalists has contributed to employing black journalists, helping with their qualification and helpingnew journalists in the job market. The Clinton group also promotes a prominent role for Black journalists in international conferences. Among its main impacts are also the production of research with updated data about Brazil, having directly contributed to the preparation of the research, “Race and gender in the press: Who writes in the main newspapers in the country?” This research was completed through a partnership with the State University of Rio de Janeiro.

In 2022, the Journalists Network began a mobilization that culminated in the creation of the Articulação Pela Mídia Negra, bringing together historically relevant organizations for the formulation of public communication policies that utilize diversity and inclusion. These efforts were coordinated by the Commission of Journalists for Racial Equality (Cojira); the Quilombação Network; the National Commission of Journalists for Racial Equality (National Federation of Journalists); and the Center for Latin American Studies on Culture and Communication (University of São Paulo). The action brought together 55 organiza-

tions led by black communicators and journalists who produced a document listing with 59 demands that was delivered to members of the Lula Government at a meeting held at the Ministry of Communications, in Brasília, in July 2023. This meeting included different actors from the federal government and civil society leaders. Among the main demands identified is the promotion so that the black population can develop and implement their communication actions successfully, considering that the black population is already impacted in different ways by social inequality.

The development of public policies in partnership with the federal government is extremely important to face common challenges that transcend geographic and administrative borders, as is the case with communication. The meeting was attended by representatives of the Ministry of Racial Equality, the Secretariat of Communication, the Ministry of Culture, and the Ministry of Communication and the Ministry of Human Rights.

Collaboration with the federal government is expected to ensure integrated development needed in this era of disinformation in the country. It is necessary to demand actions to guarantee the quality of information and the strengthening of democracy.

Today’s hypertechnological digital civilization is witnessing the advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its applications in every sphere of our lives at a speech which is beyond the comprehension of a vast majority of citizens across the world. Digital technologies have invaded all our private spaces, micro-managing our choices on what we should purchase, what we should consume, and what we should do. These are monitoring us, even though we may be unaware of it. We are under surveillance.

There is no doubt that AI is playing significant role in different fields like medical sciences, businesses, criminal justice systems and forensic sciences, innovation, and research. But its misuse in different forms is a matter of concern for the entire human civilization. For instance, its use in developing violent online games has serious impact on youth worldwide. Further, it can be misused for spreading hatred and magnifying violence. In fact, AI-enabled hate speech and propaganda are the critical challenges for communicators today. This serious concern was expressed by senior Gandhian scholar Natwar Thakkar who emphasized that the biggest challenge before communicators today was to develop counter-narratives (like those encouraged by peace journalism-Ed.) to those spreading racism, xenophobia, intolerance, and hatred. (Kundu, 2018 & 2020).

The concerns are real as it is not very difficult to make fake videos or deepfakes which can be used to create rift between communities, misinformation, spread intimidating and divisive messages, and propagate unethical actions. The problem is the complexity of detecting deepfakes as deep fake creators continue to use superior technologies, making it difficult to detect them. Further, there could be a situation when AI creators develop killer robots or robots which are especially created to promote intolerance in an already fractured world.

It is in this backdrop, Thakkar (Kundu, 2018 & 2020) argues for the need to promote nonviolent communication literacy amongst the citizenry across the world. We have delved on this significant issue in our chapter, ‘Man is supposed to be the maker of his own destiny’ arguing on the need to integrate Gandhian values in the age of Metaverse and Algorithm. (Kundu & Shah, 2022). The argument was on the ‘need to bring in creativity and new innovations in our understanding of humanism and human values and how

Image generated by AI on picsart.com. Prompt: “AI spreads hate speech.”

AI from Pg 10

area on the economic benefits of nonviolent communication and its assimilation for greater well-being needs to be promoted.

For instance, we would like to stress that the principles of nonviolence and altruistic tendencies like compassion, empathy, kindness, and gratitude, which are all elements of nonviolent communication, could be described as important elements of higher human intelligence. So a global movement could be initiated wherein AI systems which incorporate the principles of nonviolence and the altruistic traits can be described as ‘truly intelligent.’

join forces and build trust for peace and security.” (https:// news.un.org/en/story/2023/07/1138827)

--Vedabhyas Kundu and Munazah Shah

References

1. Kundu, Vedabhyas (2018). Nurturing Emotional Bridge Building: A Dialogue with Nagaland’s Gandhi. Peaceworks, 8 (1), June 2018. Retrieved from https://peaceworks.in/ issuepdf/76573Peaceworks_Vol8_Issue1_2018.pdf

to integrate these in the virtual world innovatively.’ The thrust was to promote humanization of our communicative efforts using elements of Gandhian nonviolent communication which necessitates practicing nonviolence in all aspects of communication. (Kundu, 2022). This is all the more important as big AI companies like OpenAI (the creators of Chat GPT), Google, Microsoft, and Nvidia jostling with each other in the race for supremacy in AI development. With the increasing human-AI interaction, there is a strong argument that our communication and the language we use with other human beings are becoming increasingly machine-oriented. It seems bereft of the human touch and can be described as ‘frozen’ and lacks the emotions which describe human interactions. It is in this context that we need to promote human-centric communication as a goal which integrates the values of compassion, empathy, kindness, gratitude, love and respect. Therefore, efforts should be made to make nonviolent communication, which is a holistic communication approach, the language of AI systems. (Kundu, 2022). The goal of nonviolent communication is to encourage soul-to-soul interactions which can be a panacea to rising mistrust and acrimonies among different peoples across the world.

In our exploration with researchers and thinkers on the issue of why nonviolent communication has to be an important pillar in the framework of digital technologies, we would like to argue that all those involved in peace and nonviolence movements need to engage with AI developers and engineers. While even if we wish, we cannot stop the intrusion of AI into our lives, so the challenge would be to motivate AI engineers to develop systems that integrate the principles of nonviolent communication. Talking to few researchers on AI, it was felt that in a market-driven world it may be challenging, but not impossible. A whole new

Continued on next page

Further in our chapter, ‘Man is supposed to be the maker of his own destiny’ (Kundu & Shah, 2022), we discussed the need to promote the idea of nonviolent footprints using Gandhian principles of nonviolence that enable us to measure ourselves through self-reflection and self-introspection on how nonviolent we are. The same concept can be used in the case of AI systems where the efficacy of the system can be measured in terms of its nonviolent footprints. For instance, in the case of gaming industry, online games which promote nonviolent behavior and attitudes amongst young people who are using these games could rank the highest in terms of their nonviolent behavior. Those AI developers creating violent games with harmful content should be ranked zero in terms of their contribution to a global culture of peace. It’s even possible that those involved in peacebuilding and working to promote nonviolence could create awards on nonviolent footprints.

While efforts are already being made to develop AI systems which can detect hate speech, AI developers need to be encouraged to developed AI-based peace and nonviolent chatbots. Such chatbots can aid interventions of peacebuilders and those who are working to promote nonviolent communication. In fact, such systems which use the tools of nonviolent communication can be used in a big way as counter narratives to trends of xenophobia and languages of divisiveness and intolerance. Further, as a counter to deepfakes, the aim could be to promote ‘deepnonviolent videos’ which promote the idea of nonviolence as a practical strategy that needs to be nurtured in our daily lives.

This is all the more relevant against the backdrop of comments made by UN Secretary General António Guterres. He recently said at the UN Security Council that if “AI became primarily a weapon to launch cyberattacks, generate deepfakes, or for spreading disinformation and hate speech, it would have very serious consequences for global peace and security.” Guterres stressed, “We must work together for AI that bridges social, digital, and economic divides, not one that pushes us further apart. I urge you to

2. Kundu, Vedabhyas (2020). Exploring the Indian Tradition of Nonviolent Communication. International Journal of Peace, Education and Development, 8(2): 81-89, December 2020. www.mkgandhi.org/articles

3. Kundu, Vedabhyas & Shah, Munazah (2022). Pathways to Global Transformation: Conversations with BAPU; New Delhi Publishers.

4. Kundu, Vedabhyas (2022). Exploring the Gandhian Model of Nonviolent Communication and its Significance; Gandhi Marg. 44 (1), April-June 2022. Retrieved from https://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/Gandhian-model-ofnonviolent-communication.html

5. Kundu, Vedabhyas (2022). Nonviolent Communication for Peaceful Co-existence. In L.R. Kurtz (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict, Vol. 4. Elsevier, Academic Press.

” “ (The) economic benefits of nonviolent communication...needs to be developed.

The media wields immense power in shaping our perception of worldwide conflicts. Yet, a closer look reveals a concerning pattern: coverage often mirrors the viewpoints of political elites, rather than offering a more balanced view. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Global South (encompassing Africa, Asia, and Latin America), where conflicts tend to be overshadowed by those affecting Western powers.

Ever since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, news outlets worldwide have bombarded us with updates on the conflict. The attention given to the victims of this war dwarfs coverage of other humanitarian crises across the globe. The rationale? The geopolitical and economic impact of Ukraine’s conflict is deemed globally significant. Stories about Ukrainian victims stand out as narratives of real individuals impacted by the conflict. In contrast, victims of other crises are often portrayed as faceless groups (if they are portrayed at all), making it difficult for us to connect with their stories. This lopsided coverage raises the question: Whose suffering truly counts? Is one group’s pain prioritized over another’s?

This study dives into how the U.S. media tackled three recent massacres connected to Russia: those in the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, and Ukraine. Despite Russian links to all three crises, media attention on the Ukrainian tragedy far surpassed that of CAR and Mali. The research aims to unravel this discrepancy through the lens of U.S. foreign policy.

In contrast (to Ukraine), victims of others crises are portrayed as faceless groups.

Take the Aïgbado massacre in CAR and the Boura massacre in Mali, both executed by the Russian paramilitary group Wagner in early 2022 amid ongoing civil strife. In both cases, victims were painted with a broad brush, lacking individual context. The stories didn’t delve into the historical backdrop of these conflicts. In sharp contrast, the Bucha massacre during Russia’s Ukrainian invasion gripped U.S. headlines. Media narratives focused on individual victims and the moral imperative for peace talks.

When it comes to June’s twin tragedies of the implosion of the Titan submersible (5 lives lost on June 18 while exploring the wreck of the Titanic) and the loss of a boat carrying migrants (600+ lives lost on June 14, 47 miles off the coast of Pylos, Greece), the media lost all sense of proportionality, and fairness to the victims.

In 2022, three documented massacres unfolded in conflict zones around the globe. Two of these tragedies struck Africa – one in the Central African Republic (CAR) and the other in Mali. The third occurred in Ukraine. Humanitarian reports point to Russian involvement in all three incidents.

The research contends that this skewed coverage arises from Africa’s lower priority on the U.S. foreign policy agenda. While Russia’s global interventions are seen as threats, media outlets often echo policymakers’ greater concerns, particularly those related to Ukraine. Ukrainian suffering is humanized, while African crises tend to be marginalized. This discrepancy has far-reaching consequences, since media attention directly influences where humanitarian aid flows.

The study’s foundation lies in content analysis findings from two major news sources, the New York Times and the Washington Post, after these massacres occurred. The Aïgbado massacre, predating Russia’s Ukrainian invasion, received only a single mention in the New York Times and no coverage in the Washington Post. The Boura massacre fared slightly better, with four New York Times articles and one Washington Post piece. In stark contrast, the Bucha massacre garnered a staggering 55 New York Times articles and 77 in the Washington Post.

Coverage of the Ukrainian tragedy wasn’t just more extensive; it also explored a wide range of themes. The Washington Post primarily delved into the conflict’s repercussions for Ukraine and the world (38%), as well as the conflict itself (27%). These pieces often featured insights from Washington politicians, unsurprising considering that foreign policy stories frequently cite such officials. The New York Times, on the other hand, focused on the conflict’s aftermath (28%) and the human-interest angle (25%) of the massacre. Human-interest stories centered on Bucha’s individuals who suffered due to the massacre, leveraging

Continued on next page

The five submersible lives lost included three wealthy businessmen, a billionaire’s son, and a deep sea explorer. The 750 on the fishing boat were poor migrants primarily from Pakistan and the Middle East, trying to reach Europe. An estimated 100 survived.

While these tragedies are in no way comparable, the press reported about them as though the five lives lost far outweighed the hundreds of drowned migrants. A Google News search for the month before and after both tragedies (6/7 to 7/7) showed 15,800 hits for “Greece Migrant boat,” but an overwhelming 234,000 hits for “Titanic submersible.” (Similarly, “Greece refugee ship” had 7,930 news hits, while the search for “Titan submersible” got 187,000).

“We saw how some lives are valued and some are not,” Judith Sunderland, acting deputy director for Europe at the group Human Rights Watch, told The New York Times. “I don’t think it was wrong to make every effort to save (the submersible). What I would like is to see no effort spared to save the Black and brown people drowning in the Mediterranean.” The Times also reported comments from former President Barack Obama, who said of the submersible, “The fact that that’s gotten so much more attention than 700 people who sank, that’s an untenable situation.”

I agree with the president. The ratio of almost 15 Titanic submersible stories to 1 migrant boat story reflects something deeply wrong with traditional media that values only Western, white lives while ignoring or marginalizing others. Part of the problem as well is that reporting about migrants (unless they are from Ukraine) often suffers from “compassion fatigue” since, sadly, deaths among migrants are commonplace. No matter how routine, we must never forget that each incident of this type is still a tragedy.

Peace journalism offers a better approach to reporting about migrants by, first, giving their stories equal or greater weight when merited by

local sources for authentic coverage. These stories conveyed individual suffering, quite different from the collective narrative. Both newspapers emphasized attributing the massacre to Russian troops that invaded the city.

In stark contrast, coverage of the humanitarian crises in CAR and Mali not only remained limited but primarily fixated on the conflict’s impact on West Africa, sidelining global implications and Russia’s expanding role in Africa. Even within this restricted coverage, victims were addressed as a group, rather than as individuals whose lives were disrupted or cut short. Remarkably, no individual victims were featured in interviews, despite journalists being on-site during the massacres.

--Titanic sub destroyed in ‘catastrophic implosion,’ all five died

--What could be the real cause of the sinking of the Titanic sub

Everything to Know About the Titanic-Bound Sub

The unsettling days after the Titanic submersible’s demise

-Migrant

-Around

the facts. Better migrant reporting humanizes individuals while providing context that illustrates larger statistics or trends. A peace journalist would reject language or images that rely on or reinforce stereotypes, racism, sexism, or xenophobia, and instead offer counter-narratives that debunk stereotypes, challenge exclusively negative narratives, and provide background about the desperation that drives individuals to risk their lives boarding overcrowded boats.

--Steven YoungbloodWhile Russia’s growing presence in Africa poses threats to U.S. interests, the continent still occupies a lower rung on the policy ladder. Historically, reporting on conflicts in the Global South, especially Africa, has fallen short in recognizing the intricate socio-cultural forces at play, limiting the narrative to fit policymakers’ perspectives. The result is inadequate media attention that fails to capture the human side of humanitarian crises. This situation is dire, considering that media coverage directly correlates with the funds allocated for aid.

Indeed, the politics of representation holds the power to determine whose lives matter and whose are dismissed.

--Maha Bashri“Some lives valued, and some are not”boat disaster: What to know about the tragedy 350 Pakistanis were on migrant boat that sank off Greece

From time to time, The Peace Journalist features exemplary peace journalism artuckes from around the world. This story, which gives a voice to a frequently marginalized group while empowering them to fact check and fight disinformation, certainly qualifies. --Ed

The world today is undergoing digital transformation, where almost every sector is being digitalized. This is due to the advancement in technology and growth in Internet. Globally, there were 5.18 billion internet users as of April 2023, representing 64.6% of the world population, according to Statista.

The SLI’s are being trained with the skills to record videos with sign language and edit with their smartphones, and produce contents for the deaf community in Uganda.

“We are equipping them with skills of multimedia content production , so that they are able to produce those messages timely for the deaf people as we try to offer digital inclusion for them,” Tito Okello Lutwa, technology officer at CT Media Uganda, explains.

Uganda’s Internet penetration rate stood at 24.6 percent of the total 46.7 million population at the start of 2023 and the Internet users were 11.77 million in January 2023. Information and Communications technology (ICT) is now Uganda’s fastest growing sector and contributes significantly to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The World Health Organisation estimates that currently there are more than 1.5 billion people (nearly 20% of the global population) who live with hearing loss; 430 million of them have disabling hearing loss. Deaf people make up close to 3.4% of Uganda’s population and are one of the most excluded minority groups in the country.

The digital transformation has made the deaf and hard-ofhearing people the losers as they are left out of the equation because there is no clear policy like Digital Uganda Vision, which provides a framework to uphold the national Vision 2040 through building a digital society that is secure, sustainable, innovative, and transformative, to create a positive social and economic impact through technologybased empowerment.

The deaf community uses sign language to communicate, yet there are few mainstream media outlets in the country that provides that option, and even though are largely providing unverified content through social media. In Africa, only four countries, Kenya, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Uganda, have recognized sign language as an official language. The World Health Organisation (2021) estimates that Africa has 136 million people with some degree of hearing loss, and it is anticipated that the number may reach 332 million by 2050.

A Uganda Multimedia Organisation, CT Media Uganda, is currently embarking on bridging the gap by training the sign language interpreters (SLIs) on digital content production to communicate with the deaf people effectively.

The recorded video messages are then shared with the deaf and hard-of- hearing people on social media platforms such as WhatsApps, YouTube, Facebook, and Tik Tok among others, so they are able to get timely information. The messages are about service delivery, climate change, health, disease outbreaks, market and commodity prices, elections, agriculture, etc. In Uganda, the deaf community hardly gets any information without the aid of interpretation because many cannot afford a television. There are also challenge of late identification of hearing loss among children, and low deaf awareness in families, schools, and even the health system.

The SLI’s are also being trained on how to fact check digital content which is misleading in nature such as misinformation and disinformation, and counter it using recorded video messages to stop it from spreading among the deaf community.

The deaf community is particularly vulnerable to disinformation because they may have difficulty accessing accurate information due to lack of accessible media, the prevalence of disinformation-spreading social media, and

lack of awareness about fact-checking resources.

This is due to a number of factors, including the fact that deaf people are more likely to use social media than hearing people. This can make them more susceptible to misinformation and disinformation that is spread on different digital platforms.

“We want to stop the spread of disinformation among the deaf community in Uganda. They are consumers of disinformation because they may not be aware of the resources that are available to help them verify the accuracy of information,” Tito Okello adds.

Ocen Dominic, the chairperson of Gulu District Deaf Association, spoke at the conclusion of a one week training for SLI’s in Gulu City. He described the trainings as heavenly sent. “During the COVID-19 lockdowns, we lost our member in Agago district to the security personnel because they could not get message about the lockdown, but this will help to bridge the gaps,” Dominic noted.

Dominic adds that the deaf people are often left out. “Nobody cares about us,” he said. “Thank you for coming to our rescue. We hope this will help bridge gap in digital inclusion in Uganda.”

The SLI’s have now created a ‘Deaf WhatsApp group’ with more than 300 members to help share important information, and verify claims and news which are misleading.

“By creating this network of community fact-checkers, we are not only fighting the spread of disinformation among the deaf community, but also for every member of the

society,” Tito notes.

Abalo Sandra, one of the trainees and a sign language teacher with Amuru District Disabled Persons Union, says the WhatsApps group is helping deaf persons to communicate easily using the skills they acquited during the training. “For example, recently the Uganda Meteorological Authority announced there would be El Nino in Uganda, but the deaf were not aware. We recorded this message in sign language and we shared with them on WhatsApp.” The SLI’s are being trained together with radio journalists to become agents of community fact-checkers in Uganda so that they are able to debunk disinformation that could spread among the deaf community.

The journalists are being trained so that their media houses provide content that is accessible and can be understood by the deaf people, and also to use sign language interpretation in their digital content.

CT Media Uganda has trained 17 people as the first cohort of Uganda Sign Language Project, with the aim of providing digital inclusion and fight the spread of disinformation among the deaf society in Uganda with funding from Empowering the Truth Global Summit. Empowering the Truth is part of Disarming Disinformation, run by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), with lead funding from the Scripps Howard Foundation.

--Willy Chowoo

Coinciding with World Press Freedom Day, May 3, in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, a mass shooting in a primary school in the center of the city took place. The way the regional media covered this event, and my dissatisfaction with it, is the main motivation behind this article. Once, while I was attending a peace journalism training, after explaining the basis of the concept of peace journalism, our lecturer declared: “So if you are thinking that peace journalism is just good journalism, you are right.” Having that in mind, let’s analyze this story of bad journalism.

The cold-hearted facts

On the morning of 3 May 2023, a 13-year-old child, a student of the Primary School “Vladislav Ribnikar,” entered the premises carrying firearms. He used the weapons to shoot and kill eight of his fellow students and the security guard of the property.

Nothing about this case is close to an ordinary Wednesday in this part of the world. Even though the Western Balkans is part of the route of illicit weapons trafficking and endures the presence of illegal firearms, the ownership of lethal weapons is fairly regulated. The traces of the old socialist regime in former Yugoslavia have left their mark in the active legislation of the countries of the region, making gun control fairly advanced compared to other parts of the world.

Having in mind the local and regional context, many questions should have been covered by the media after the shooting. And many were. Sadly, not the right ones.

The first available information

The first information made available was written ignored the fact that the wrongdoer was a minor. In the

first days after the event, questions on how did 13 years old boy get his hands on the guns, how did he manage to get into the school unnoticed, did the boy suffer a history of abuse, was he in need of professional help, etc. were deemed irrelevant by the press. Although the reporting was lacking substance, it did not however lack sensationalism in any way.

The text of one story reads (Serbian to English as translated by the author):

“The night before bloodshed, Kosta (the shooter) was at his friend`s, and after that, he went to a party, while the rest of his free time he has been playing violent video games...As the portal Republika discovered, the night before the bloodshed, Kosta has been at his friend`s place, and after that, he went to a party, where they, as suspected, consumed narcotics.

“Let us remind you that it is not known whether Kosta was under the influence of psychoactive substances during the bloody feast at 8:30 in the morning. However, during the arrest, he uttered only one sentence: ‘I shot because I am a psychopath!’”

As noted, none of the information presented in the text can be viewed as relevant, and even less as crucial for keeping the public well informed on the developments and safe from additional harm. On the contrary, the image created in this case is much more harmful to the minor wrongdoer, as well as for youngsters due to the irresponsible scattering of epithets that build an unequivocally negative image of children with certain characteristics and interests.

While profiling is a regular practice, in cases such as hit and run or escaped criminals, when implemented it mostly focuses on physical attributes which would potentially help the law informant to spot the wrongdoer. This case

is completely lacking such context.

The text names and profiles the 13-year-old wrongdoer as a “bloodthirsty junkie gamer,” stripping him from any human attributes while completely turning a blind to the fact that the wrongdoer in the case is quite literally, a child. Such profiling deprives the individual of any empathy needed for the process of recovery and reintegration into society. While the reporting is inconsiderate to the wrongdoer himself, it also puts targets on other kids who fit in the general description painted by the media. Such portrayals may lead to further isolation from the communities and to social exclusion, and can potentially create new victims due to such exclusion.

While respect for privacy and anonymity have been completely neglected as a principle, cautiousness regarding the motive of the wrongdoing is also lacking in this case. The media did not even refrain from using graphic imagery additionally amplifying the collective trauma. The excessive coverage, as suspected, brought about two of the least desirable side effects: glorifying the violence, as well as one case of the so-called copycat crime. Luckily, both cases did not culminate with any action or deaths, so both were assumed to be and dismissed as acts of rebellion.

Peace Journalism Principles (Mis)fit “Peace Journalism is when editors and reporters make choices that improve the prospects for peace. These choices, including how to frame stories and carefully choosing which words are used, create an atmosphere conducive to peace and supportive of peace initiatives and peacemakers, without compromising the basic principles of good journalism.“ This is part of the definition of peace journalism, as defined in the online resources available at the base of Park Univer-

Continued on next page

sity (www.park.edu/peacecenter) and it will serve as a baseline to assess the alignment of the reporting done on this event with the 10 principles of peace journalism. In the very beginning of this statement, it has to be noted that we are looking at the principles as a concept, and in the context of the event.

1. PJ is proactive, examining the causes of conflict, and looking for ways to encourage dialogue before violence occurs. Although media outlets at some point started discussing the issue of peer bullying as a possible trigger for the wrongdoer to take this radical step, the manner of the reporting has not been proactive in the sense of examination. Social media playing the role of media outlets, on the other hand, were able to encourage dialogue on mindful parenting, internet use and misuse, and mental health issues amongst the youth.

2. PJ looks to unite parties, rather than divide them, and eschews oversimplified “us vs. them” and “good guy vs. bad guy” reporting In this particular case, this principle is not directly applicable since there are no opposing groups. It did anyhow spark a debate on “good vs. bad” parents whose kids would(not) be prone to commit such acts.

3. Peace reporters reject official propaganda, and instead seek facts from all sources. This is probably the principle of peace journalism that is most applicable. The majority of the media followed up on the irresponsible and politically motivated profiling carried out by officials of public institutions.

4. PJ is balanced, covering issues/suffering/peace proposals from all sides. In this particular case, this principle is not directly applicable.

5. PJ gives voice to the voiceless,

instead of just reporting for and about elites and those in power. In this particular case, this principle is not directly applicable

6. Peace journalists provide depth and context, rather than just superficial and sensational accounts. This principle has been followed only by media outlets dedicated to quality journalism that were, in fact, critics of the media’s sensationalism. But it has to be noted that the debate on the problems of bullying in schools and the mental well-being of the youth got new momentum after the event, and those initiatives have been fairly covered by the media.

7. Peace journalists considers the consequences of their reporting. This would be the second most violated principle of peace journalism. Clickbait titles and yellow page-like contents have been offering an abundance of attributes assigned to the wrongdoer, as well as deeply disturbing details on the last moments of the lives of the victims that completely neglects the effect they might have on the families, the survivors, and in the end, on the re-integration process of the wrongdoer.

8. Peace journalists carefully choose and analyze the words they use, understanding that carelessly selected words are often inflammatory. This principle is violated through the utilization of sensationalist and disturbing language that lacks sensitivity and consideration for its potential

impact on various parties involved.

9. Peace journalists thoughtfully select the images they use, understanding that they can misrepresent an event and/or re-victimize those who have already suffered. The principle of responsible image selection is violated in reports about the shooting through the use of graphic imagery and negative epithets to describe the minor young wrongdoer. The immediate disclosure of the 13-year-old boy’s identity, along with the widespread distribution of his arrest photos, videos, and personal social media content through various media outlets, showcases a disregard for responsible and empathetic reporting, thereby violating the principles of peace journalism.

10. Peace Journalists offer counternarratives that debunk media-created or perpetuated stereotypes, myths, and misperceptions. Most of the reporting contradicts the principle of providing counternarratives by propagating damaging stereotypes, myths, and misconceptions about the 13-year-old offender. The portrayal dehumanizes and lacks understanding, potentially leading to social exclusion and further victimization, rather than challenging established negative narratives.

Just bad journalism or politicallypowered machinery?

What presents an even more worrying sign for society than the poor level of

Continued on next page

Do media narratives create worthy victims?

And what impact do these narratives have on intertnational bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC)?

These questions were addressed in a July 2023, MDPI Open Access article, “Media, Public Opinion, and the ICC [International Criminal Court] in the Russia-Ukraine War,” as part of its Special Issue on the Role of the Mass Media and Digital Media in Contemporary Armed Conflict.

The article arose from the “International Conference on Xenophobia in the Media,” held at Sakarya University in Türkiye, in May 2022. Dr. Selvarajah was a key organizer. At this conference, Fiorito presented on the topic of how media narratives regarding “worthy victims” in armed conflicts seemed to be a key predictor of whether international courts, such as the ICC, paid attention to crimes committed against those victims. After the conference, we began to collaborate on turning the ideas we had discussed into a fully researched hypothesis and a search for empirical evidence to support or refute that hypothesis.

On 28 February 2022, ICC prosecutor Karim Khan announced that his office would investigate potential war crimes in the conflict in Ukraine. This announcement came on the fifth day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “Last Friday, I expressed my increasing concern, echoing those of world leaders and citizens of the world alike, over the events unfolding in Ukraine,” Khan noted at the beginning of his statement. Khan thus underlined public opinion as

from Pg 17

the execution of the journalistic calling is the possibility that the excessive and sensationalistic coverage of the event was politically motivated.

Many of the articles about the shooting used character defamation wording that has been taken from an official statement of the Minister of Education of the Republic of Serbia.

In the statement, official Branko Ružić notes how the “Western values” are the core reason for the tragedy. Тhis narrative, which glorifies what it considers to be traditionally patriarchal values typical of an OrthodoxChristian country with a history of traditionalist-right-wing tendencies, continues to spill over into many subsequent articles. Even those articles

part of his reasoning for opening the investigation. This situation highlights that information was processed and mediated between world leaders, global citizens, and the International Criminal Court.

Since it was instituted in 2002, the ICC has frequently been criticized for the way it applies justice. Our article highlighted that issuing an arrest warrant against Russian leader Vladimir Putin marked a significant departure from an overall trend, where the ICC appeared to be primarily concerned with issuing warrants for, and trying, African leaders. Furthermore, Russia has not submitted to the jurisdiction of the ICC. Finally, it is an open question in international law as to whether a sitting head of state can be subject to arrest and prosecution.

Despite these credible potential obstacles, the ICC found a pathway to open an investigation into the situation in Ukraine by the fifth day of the Russian invasion. That investigation found that the ICC had jurisdiction to arrest Putin. Justice for many other situations, in which international crimes appear to have been committed, seems extremely slow by comparison.

Comparing the speed with which the ICC acted, in the case of Ukraine, with allegations coming from other regions, indicates that the ICC considered this invasion a high priority. Khan’s statement also shows that the ICC drew, in part, on

that seem to call for empathy and attention to children, there is a serious presence of anti-liberal rhetoric and a call to return to “traditional values.”

The Aftermath:

A continuous source of click-bait

It has been over 3 months since the shooting in the “Vladislav Ribnikar”

Primary school, but the topic is still omnipresent. This would have been a good thing if what happened was talked about as a trigger for legislative change, mental health among young people policy-making, or even gun safety education.

However, most of the content is clickbait with provocative titles, telling no meaninful story. Many of the recently

public opinion in favour of taking legal measures against Russia and its leader. Such public opinion appears to have permitted the ICC prosecutor a freer rein to interpret international criminal law in a way that justified the arrest warrant for Putin and one of his lieutenants.

This creates a hypothesis that extensive international media reporting, in the first five days of the war, may have created a media discourse conducive to the ICC’s announcement that it would investigate Russia’s alleged war crimes in Ukraine. For example:

• Charlie D’Agata, CBS’s foreign correspondent, a day after Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, said on TV: “This isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades… This is a relatively civilized, relatively European—I have to choose those words carefully, too—city, where you wouldn’t expect that or hope that it’s going to happen.”

• David Sakvarelidze, the former deputy prosecutor general of Ukraine, said in a BBC interview that, “It’s very emotional for me because I see European people with blue eyes and blonde hair being killed” by Russia’s assault. The BBC anchor who interviewed him did not challenge this comment.

• On NBC, correspondent Kelly Cobiella said, “Just to put it bluntly, these are not refugees from Syria, these are refugees from neighbouring Ukraine. That, quite frankly, is part of it. These are Christians, they’re white, they’re very similar people.”

These news stories compare Ukrainian victims with victims from other regions and classify them as “worthy” and “unworthy” based on ethnicity, skin color, and eye and hair color. This categorises refugees into “civilized” and “uncivilised.” Similarly, Article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice states that being “civilized” is a precondition for a nation to contribute to the principles of international law. Ukraine is “civilized;” thus, it receives quick justice at the ICC. By contrast, Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan are not like Ukraine, and thus, they have not received quick justice. Media is front and centre in shaping these narratives about the worth of human lives under the law.

Continued on next page

published content is re-sharing social media posts by the parents. It is not a rarity to come across some contents diving into details on how the minor wrongdoer has been responding to the therapy he receives and his overall mental health state, without a cited source of information.

The text in one article reads: “‘Are they talking about me, am I the king of the social networks?’ Republika finds out that this is one of the questions that Kosta Kecmanovikj, 13, asks the employees of the Clinic of Neurology and Psychotherapy for Children where he has been accommodated after he put to death eight school friends.”

--Simona Mladenovska• Similarly, the BBC’s Peter Dobbie compared Ukrainian refugees to other refugees in a comment. “What is compelling is that just looking at them, the way they’re dressed. These are prosperous, middle-class people. These are not obviously refugees trying to escape areas in the Middle East that are still in a big state of war. These are not people trying to escape from areas in North Africa. They look like any European family that you would live next door to,” he said.

• Journalist Philip Korb on BFM, one of France’s mostwatched channels, said on air, “We’re not talking here about Syrians fleeing the bombing of the Syrian regime backed by Putin, we’re talking about Europeans leaving in cars that look like ours to save their lives.” The Poland correspondent for British broadcaster ITV commented, “This is not a developing third world nation. This is Europe.”

• In the Telegraph, Daniel Hannan wrote, “They seem so like us. That is what makes it so shocking. Ukraine is a European country. Its people watch Netflix and have Instagram accounts, vote in free elections and read uncensored newspapers. War is no longer something visited upon impoverished and remote populations.”

Legitimate questions arise as to whether the five days of media reporting could have created a public opinion strong enough to influence the ICC and, even if there had been such a public opinion, whether the ICC could have conducted due legal process with such extraordinary speed by prima facie principles. Nevertheless, our article explains the analytical framework, hypotheses, and empirical data which support the basic premises that we have outlined here.

In our analysis of eight major English-language newspapers from four Western Anglophone countries, we see an elitedriven media propaganda strategy in the first five days of the war. This strategy portrayed the problem as Putin’s alleged commission of war crimes in Ukraine; and its solution as sanctions, a war crimes inquiry, and a trial at the ICC.

The media strategy we identified as taking place in the first five days of the Russia-Ukraine war and ICC Prosecutor Khan’s announcement at the end of those five days, strongly appear to be related to one another. While the media strategy itself is probably not solely responsible for causing the ICC’s announcement, these two phenomena are likely to be effects of a cause that originates in realpolitik.

Although our paper identifies the tendency of ICC decisions to be manipulated by elite-driven media propaganda, it highlights the need for the media to adhere to Peace Journalism, a proactive and peace-oriented reporting that gives voice to other people than elites, to avoid this malpractice.

--Lorenzo Fiorito and Senthan SelvarajahOur paper identifies the tendency of ICC decisions to be manipulated by...media propaganda, and highlights the need for peace journalism.

Recently, Pakistan has seen a surge in abuse, violence, rape, and even murder of children. In the past, their stories would have been restricted to a small column in the corner of a page or not aired by the channel for a shortage of time or interest, as assumed by editors supervising media. Now, these stories are run as “breaking news” by the same channels.

Last month, Pakistan was once again shocked when the news of two consecutive horror stories emerged involving two minor who were maids in different parts of the country.

One child was beaten so badly that for a long time, it was touch and go as she lay battered with almost every bone in her body shattered. She had to be kept in intensive care for some time but is now recovering, although she is still in critical condition.

The other case was that of a maid child given into the custody of a local pir (spiritual leader) who raped the child and left her to die as he left to go to sleep on his bed a few feet away from the withering body of the child.

His crime was caught on a CCTV camera. The footage went viral on social media and incriminated him. The pir knew about the camera but he continued his barbarism, probably safe in the knowledge that he was a revered spiritual leader and his followers and his wife would overlook this crime even though it was not his first.

All hell broke loose when the video hit social media and went viral. People watched the crime enacted with apathy in the video as rage and horror intensified.

The outcry spilled over many different social media platforms, forcing the traditional mainstream media to take

note. This led to police action and the criminal being arrested. If social media hadn’t raised this issue, the pir would have just moved on to his next victim –available in surplus as his devotees leave their children to serve him.

It was amazing to see the reaction on social media and the pressure that was put on the authorities to take action. In the past this would not have been possible and the victim would have just been another dead body and no one would have paid heed to the maid child who had been robbed of her life by a monster.

For many years, Pakistan has seen how social media has played a pivotal role in getting stories onto the mainstream media which have been ignored or underreported for years.

Like other countries, cases of violent crimes against children and women have largely been consciously or unconsciously ignored and kept out of the media. Such crimes are the underbelly of a conservative social setup that prefers to look away when crimes against women and children are committed instead of confronting them and taking steps to stop them.

But when social media arrived and common people got a chance to speak up, more and more crimes against the marginalised began getting noticed. The frequency and the impact increased as the audience realised that social media was a very powerful tool to disseminate the story and to get a reaction from society and action from the authorities.

Social media has many aspects and all of them are fascinating for many who are not social media natives. Several amazing aspects of social media include its impact of an image or word, the immense, immediate reach of a post, and the reaction to the post. It is unimaginable for any other kind of media that has existed.

In the heart of Central Africa, Cameroon has been grappling with a protracted crisis that has left communities shattered and families torn apart. Amidst this turmoil, a growing need is emerging, one that advocates for the power of non-violence as a means to address conflict and heal wounds. As the nation stands at a crossroads, the idea of embracing non-violence is gaining momentum as a promising alternative to the cycle of violence that has plagued the country for years.

And if that is not enough, social media is a vast ocean of information that provides a vast array of content, including news that was never seen before. It is hard to control and regulate. This helps the common people report on issues that would otherwise would not make it to the headlines.

The impact of citizen reporting has changed the media landscape in Pakistan. Channels reluctant to deviate from their normal streaming mainly of political news has been forced to keep an eye on social media trend and follow up on anything that is viral.

Social media, where posts from common people proliferate, may lack the finesse of the mainstream media, which is mostly run by professional journalists, but it has become a force that can and has changed the tide of the news available and consumed by hundreds of thousands inside and outside of Pakistan.

Pakistani media seems to be controlled by reverse psychology as it is shaping its news output under the influence of viral trends and content on social media.

Continued on next page

The Cameroon Community Media Network (CCMN) across the country has as one of their main missions