SEPTEMBER 2025

Boston Ballet School is dedicated to creating an inclusive environment that empowers all students to make discoveries, grow artistically, and express joy.

Explore our range of expertly designed classes for students ages 16-months to 18 years* at all four studio locations. Enroll for the 2025–2026 school year today!

Pediatric

Wesley Barton, DMD

Bahar Houshmand, DDS

Ava Ghassemi, DMD

Mahdieh Beheshti, DMD

Jessie Tsai DMD

Dentist

Orthodontics

Roger Taylor, DMD

Shahrzad Khorashadi, DMD

Orthodontist

Boston Parent

841 Worcester Street Suite 344 Natick, MA 01760 • 617-522-1515

info@BostonParentsPaper.com Visit us online at BostonParentsPaper.com

ADVERTISING

We asked and you told us who your New England favorites are, in droves! Boston Parents received over 200,000 votes from you guys! Awesome! We have your places to vacation, museums to visit, restaurants, schools, medical, special needs and the list goes on and on! Plus, you can find all of the categories online at BostonParentsPaper.com. Mark your calendars! The voting for 2026 Family Favorites starts March 1, 2026.

How to make the transition easier.

Feelings of anxiety are expected for children going through transitions such as going back to school. Over the summer, routines have changed and worries of the unknown may begin to stir as the school year approaches. There are ways to recognize anxiety in your child, as well as interventions that can help relieve those feelings. Some behaviors that may indicate your child is having anxiety surrounding the return to school are irritability, change in sleep patterns, continually seeking reassurance or asking repeated questions, and in some cases complaints of headache, fatigue and stomach ache. It is important for your child to attend school to learn that their fears can be overcome, as prolonged absence can worsen your child’s fears.

One of the best ways to make the school transition easier on your child is to acknowledge their anxiety. This can be done by listening to your child’s feelings and encouraging them to speak to you about how they feel. It is important to validate their feelings and not dismiss them. Demonstrate confidence that your child can handle the situation.

Practicing school routines is another way to prepare your child for school. This can include practice walks to the bus stop, evening routines of packing the backpack and picking out

their clothes, or routines that begin when they wake up such as breakfast, getting dressed and traveling to school. Having a school tour prior to the first day can be a great way to introduce the new environment, as well as finding a new friend or neighbor who will be at the school prior to the first day. During the practice runs, it’s helpful to support your child as they think through difficult points of their day such as changing classrooms.

Another way to provide relief for your child is modeling the calm behavior you would like to see. This can feel difficult in situations where you feel stressed, rushed, or anxious yourself. To work through your own feelings, think of taking deep breaths and remind yourself that your child’s behavior is being driven by anxiety.

Another method to set your child up for success for the new school year is ensuring enough sleep based on their age. The new wake-up schedule for school may need to be slowly implemented 1-2 weeks ahead of the first day. Feelings of fatigue can enhance your child’s anxiety.

After the school year begins, if your child continues to display signs of anxiety such as tantrums, problems sleeping, and/or refusal to attend school or activities, speak with your primary care provider about further interventions. Y

We all know living in our great state is pretty awesome! A recent study by WalletHub confirmed it. WalletHub compared the 50 states across 52 key indicators of family-friendliness measuring data set ranges from medium family salary to housing affordability to unemployment rates. It is no surprise that Massachusetts came in at the top as the best state for families, again! Rounding off the top 10 are Minnesota, North Dakota, Nebraska, New York, Illinois, Wisconsin, Maine, and Connecticut. To see all the results, go to www.wallethub.com.

What better way to keep track of all the preschool and private school’s admission events than this handy tool! With over 50 entities participating, check out the Online Open House & Admissions Calendar on BostonParentsPaper.com. Look for the School Open Houses button on the main header bar and tap. Don’t forget to tell them you saw their event on https://bostonparentspaper.com

Playgrounds are a fun and stimulating environment for kids to play and burn off energy. Although playgrounds can be fun, each year more than 220,000 children under age 14 are brought to the emergency room for playground injuries. Most injuries are a result of falling from equipment. This can include broken bones, cuts, bruises, sprains, concussions, and internal injuries. The most common injured body part is the arm.

Depending on how high the child is and the way they fall will determine what injuries they may face. This can also happen on monkey bars or swings. Children may lose their grip on monkey bars and fall as a result. Moreover, on swings, children may try to jump off of them midair. This could result in them trying to break their fall incorrectly and cause numerous injuries.

Children can also get injured if the playground area and equipment are not maintained. This can include if a slide, seesaw, swing, etc. has an exposed sharp edge. Children may not see it at first and then be playing and cut themselves. Children may also come into contact with trash or other unsafe objects that were not cleaned up in the playground, causing injury or illness.

The playground is a great place for social interaction for children and a great place for exercise. Parents can keep their child safe and allow for them to have a great time by following these simple precautions!

By Alex Ellison

In 2019, I wrote a blog entitled How Latchkey Kids Became Snowplow Parents. I wanted to explore how a generation of kids that was largely left to its own devices in the 90s became a generation of parents raising kids addicted to smartphone devices and completely content staying home with their parents. By smoothing away all obstacles and protecting their kids from the world that exists outside of their phones, Gen X parents might simply be responding to what their kids want; or they may be decelerating a Generation whose internal time clock ticks a little slower. While their Gen X parents couldn’t wait to accelerate into young adult life (Fast Times at Ridgemont High, anyone?), Gen Z has pleaded with society to grow up more slowly. This “Peter Pan” generation may even be afraid of growing up.

Jean Twenge, the preeminent author and researcher on generational trends says Gen Z is driving later, drinking later, having sex later - and much less when they do - getting married later, and signs are pointing to postponing having kids. While their parents started having sex and drinking at a shockingly young age, teens today actually find that behavior disturbing. Generally, these are good trends. Less risky behavior means fewer accidents. They are a proof of the slow-life phenomenon that is a product of safer times (yes, despite what the news might have you think) and of a high-tech age that makes it possible to grow up at a slower pace (more can be done behind a screen and out of the elements). But this isolated generation isn’t necessarily safer. According to Twenge, “For Gen Z, the dangers of the in-person “meatworld” have faded, while the maladies of an indoor, less active, screen-filled life - both mental

and physical - have accelerated.” Teens today might say they feel unsafe and stressed out by the world “out there” but they are their own worst enemies.

The world around us, with the 24hour news cycle and rapid technological innovation, seems to be moving at a blindingly quick pace, yet the barrage of new technologies has also allowed us to grow up more slowly. It’s a strange juxtaposition: a slow-paced life in a fast-paced world.

It’s this contradiction that may be partly why teens are so anxious: they feel they have less agency in an uncertain world, and they don’t feel ready to address the complexities of life.

A resource-motivated generation obsessed with safety, security, and predictability.

When I first started counseling, I thought I was on a mission to help free the American teenager from oppres-

sive, boring, and antiquated education. I was a fan of Seth Godin’s Stop Stealing Dreams, and Sir Ken Robinson’s The Element, and A.S. Neil’s Summerhill. I almost launched an alternative school for teens and I was a frequent visitor to the education-innovation conference, SXSWedu (giving a talk there on the topic of Gen Z’s early signs of bizarre practicality). I thought this would be the generation that would challenge the rising cost of tuition, forge a new, more interesting path to higher ed, look for alternatives to outdated expectations, and question conventions. The reality has proven to be much different. With only 5 more years of Gen Z teens still to go (the youngest were born in 1995 and the oldest in 2012), trends have shown a generation that is decidedly risk-averse, money-motivated, and practical.

The trend has continued with Gen Z being perhaps the least fanciful generation in history. Their heads are out of the clouds and their feet are solidly on the ground. Humanities majors are down; business majors are up. Dreams are out; real life is in.

Before the late 70s, American teens went to college to “develop a more meaningful philosophy of life.” By 1980 this meaningful life nonsense was outpaced by another, more practical incentive: financial well-being. The trend has continued with Gen Z being perhaps the least fanciful generation in history. Their heads are out of the clouds and their feet are solidly on the ground. Humanities majors are down; business majors are up. Dreams are out; real life is in.

that spare bedroom into a workout room because these kids won’t be back after college! Right?

If we’re living to 100, maybe we don’t need to get a job at 15, graduate college at 22, start a family at 25, and be retired by 65.

When I survey new students whom I counsel, What class do you wish you had in high school? I rarely see responses like sculpture, creative writing, video game design, extreme sports, or the life of Taylor Swift. Nope…. Personal finance is their top pick. That’s right. They want to learn how to balance a smart budget and do their taxes.

These sound like the kids every parent hopes for: well-adjusted, independent, tax-paying citizens. Go ahead and turn

Maybe not. Their slow-life strategy is causing them to put off adult life longer than previous generations. They may rely on their parents later into adulthood because it will take them longer to graduate (maybe with multiple degrees), get a job, buy a house, and get married. In fact, being in a committed relationship is less of a priority for Gen Z than it was for their parents, so they may very well stay attached to the families that raised them rather than raise their own.

So even though Gen Z talks about finance classes and adulting, sensing they need to know about these things, they feel underprepared for and stressed about the future, so they are clinging to what sound like safe plans. When a student tells me what they would love to do “just doesn’t pay well” it’s hard to say how much parents, peers, and social media are influ-

encing them, but it’s likely a combination of all of these. I can’t help but wonder if their bleak life goals are causing them to be less excited about the future. The class of 2024, heading to college this month, was the least excited to graduate and go off to university of any graduating class I’ve counseled.

These are “good” kids. Instead of teens worrying about their parents catching them smoking pot or swearing, it seems to be parents who are worried about their teens catching them. But good isn’t the same as enthusiastic. Most of the high school students I work with are suffering from stress and anxiety, sometimes missing school for mental health reasons; they just want the world around them and the expectations put on them to slow down, to match their slow-life strategy. And maybe this isn’t such a bad thing; if we’re living to 100, maybe we don’t need to get a job at 15, graduate college at 22, start a family at 25, and be retired by 65.

After the initial scare of the COVID pandemic in March 2020, anxiety actually fell in the early days of summer that year. Everything slowed down; teens weren’t on the performance treadmill, trying to compete in what they perceived to be an increasingly competitive world. For a brief blip, the bar was lower, the pace was slower; they could just be for a minute. My most sincere hope is that we can give teens the gift of a slower pace and in doing so, grant them permission to dream again. Y

Reference: Twenge, Jean M., 1971- author. 2023. Generations: the real differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents--and what they mean for America’s future / Jean M. Twenge, PhD.

Alex Ellison runs a college and career guidance practice, Throughline Guidance, which serves clients around the globe. She writes and lectures extensively on the subject of careers and college readiness and has been a featured speaker at SXSWedu and TEDx. She is the author of Go Your Own Way: 7 Student-Centered Paths to the Best College Experience and the creator of the Go Your Own Way Student Archetype Quiz used in schools and by individuals to jump-start their college search. Her forthcoming book, Your Hidden Genius: The Science-Backed Strategy to Uncovering and Utilizing Your Innate Talents hit the shelves in January 2025.

By Katy M. Clark

Dear Car,

Let me be the first to say, “Welcome to the family!” We are very pleased that you have joined us. You are very much loved and wanted and we looked long and hard for you.

You were the right combination of price (cheap), condition (as good as possible) and safety (not exactly Fort Knox on wheels, but we tried).

Car, I hope you have thick skin, I mean, paint. That’s because you will hear some adults whispering about how they never had a car when they were young and how you are an extravagant purchase. You might hear some people pass judgment on our family because you are in our lives now. Don’t listen to them. They don’t know how much you are needed. Nor do they know just how old and tired you are or how many miles you have seen.

You know, I am old and tired, too. I’ve also seen a lot of miles. However, I think we both still have a lot of life left in us!

Car, I’m reaching out to you because you have a very important role in our family.

You see, you will transport my teen driver in the coming years. I hope that you will function as promised, and when you can’t, that you’ll let me know promptly. In return, I promise I’ll fix you to the best of my ability and my wallet’s ability.

Car, there will be times my teenager will be less than careful with you. I apologize in advance. His father and I have told him over and over and over again how he is supposed to drive. He has passed two segments of driver’s education demonstrating how he is supposed to drive. He has logged 50 hours of supervised time behind the wheel driving how he is supposed to drive.

But, I know how I am supposed to eat and that doesn’t stop me from indulging every now and then (curse you, Olive Garden breadsticks!). So when my teenager indulges in a stop too suddenly or he turns you too sharply, even though he knows he shouldn’t, please take care of him.

Car, not only do you have the responsibility of keeping my teen safe and getting him to and fro, but you will also provide much needed transportation for my younger child.

That’s right, you will carry two of my babies as they go to school or practice.

I beg of you, keep my babies safe.

You will also meet some of my teen’s friends and I hope that you get them safely where they need to go. And yes, there may be some things spilled, said, or done by my teenager and his friends that both of us don’t want spilled, said or done.

Hang in there. I’m saying that for me as much as for you.

I also want to apologize for the stinky sports equipment that is about to make its second home in your trunk. I know it doesn’t smell pretty. If it’s any consolation, I’ve been toting it in my trunk to various practices and games for a long time. You’ll be okay. Stinky, but okay.

I’ll look out for you, Car. I’ll watch for scrapes and dents if my teen or the school parking lot treats you too rough. I’ll make sure he washes you and gets your oil changed. I know you’ll need new tires sooner rather than later (can we try for later?). Rest assured that I know how important your job is in the family and he and I will do our share to help you carry it out.

Thank you for waiting for our family. It seemed like we would never find you, but then we did.

I’m hoping this is the start of a long and beautiful relationship.

Love, Mom

Katy M. Clark is a writer and mom of two who embraces her imperfections on her blog Experienced Bad Mom.

By Jill Plantedosi

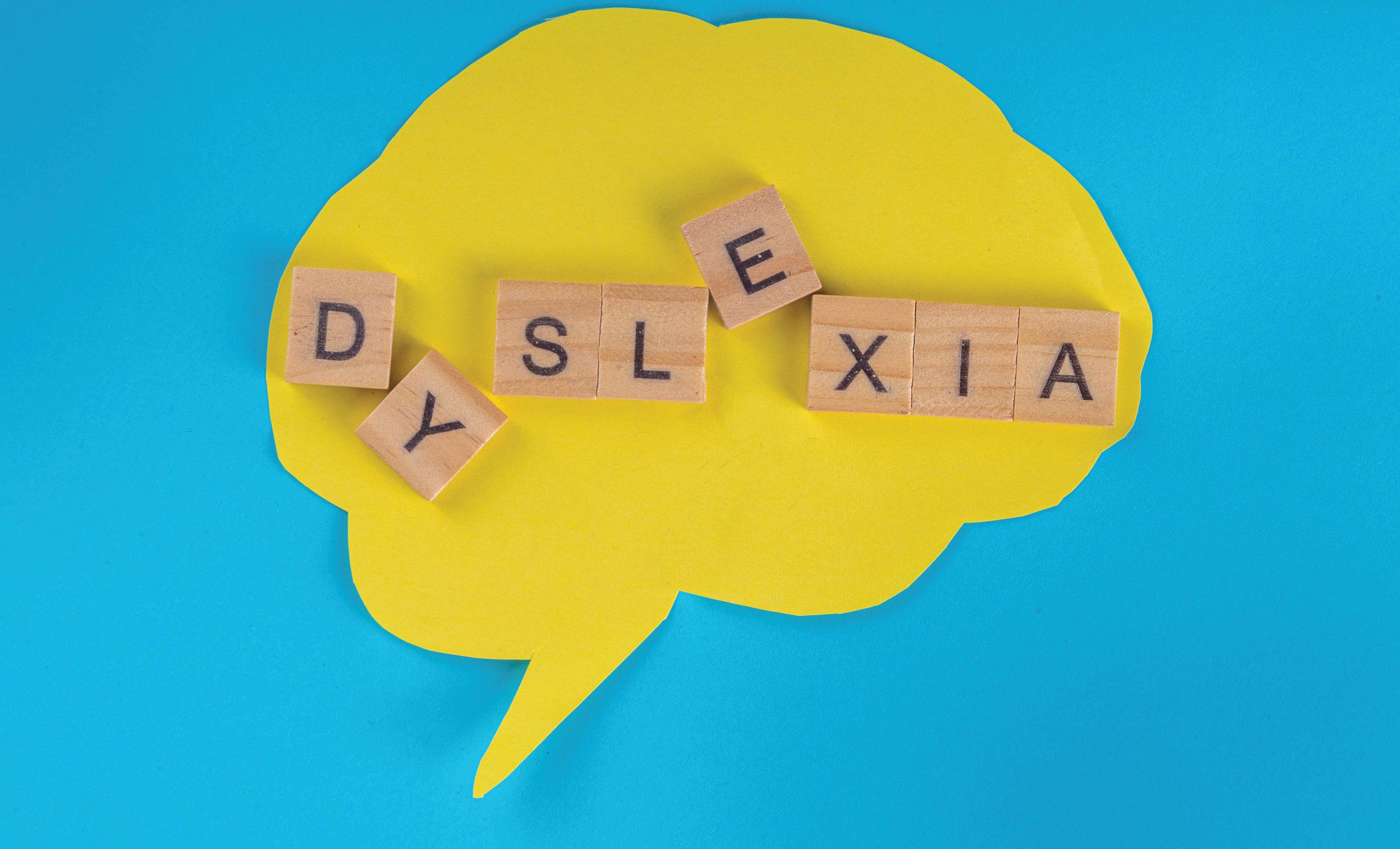

In speaking with numerous teachers and parents I have worked with over the past 25 years, a consistent question that I am asked is, “how do I know if my child or student is dyslexic?”

According to Drs. Shaywitz from the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, dyslexia effects 20 percent of the population and represents 80-90 percent of all those with learning disabilities.

Teachers have become increasingly concerned about diagnosing dyslexia as early as possible in order to put together a roadmap for success. Educators need to identify children who are at risk for dyslexia and catch them before they fall. So many children are not getting a definitive diagnosis of dyslexia, but are given a checklist of strengths and weaknesses, stating only the word “learning disability” on their evaluation. Success begins with identifying this complex problem and knowing the best interventions to put into place. The dyslexia guidelines posted on the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s website, provides a set of screening recommendations for all students, as well as a framework for intervention. These guidelines can be quite helpful in providing information needed to support students with dyslexia.

Dyslexia is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities.

According to the International Dyslexia Association, (www.interdys.org), “Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.” (Adopted by the IDA Board of Directors, Nov. 12, 2002)

The basic deficit in dyslexia, is the result of persistent difficulties with phonological processing. If your child has a phonological impairment, and struggles with the individual sounds of spoken words, he/she may have problems with:

• Spoken language linked to a child’s phonological skills, (Either delayed early on and/or word retrieval later on).

• Phonemic awareness (understanding by the child that spoken words are made up of smaller units of speech)

• Difficulties with pronunciation of words

• Rapid automatized object naming

• Identifying letters of connecting letters to sounds

• Ability to use expressive language

• Decoding difficulties that impact accuracy

• Hearing and repeating rhyming sounds

• Encoding sounds into letters and spelling

• Learning the sound system of a foreign language

• More boys than girls are dyslexic-Dyslexia affects comparable numbers.

• Dyslexia will be outgrown-Dyslexics will be able to learn to read accurately, but will continue to struggle with fluency and automaticity.

• Intelligence is related to dyslexia- Dyslexics often have a high IQ.

• Dyslexia is a vision problem-Dyslexic children are no more likely to have vision problems than non-dyslexic children.

• Mirror writing is a symptom of dyslexia-This is very common in all children at the early stages, as young children commonly reverse letters.

• Dyslexia doesn’t show up until elementary school-Dyslexia can show up in preschool. Often these preschoolers were late talkers and had difficulty with rhyming words.

• Dyslexic children need to try harder-Effort has nothing to do with reading success, as the brain functions differently in a dyslexic child.

• There is no way to accurately diagnose dyslexia-We can now accurately identify those at risk as early as preschool and children who are dyslexic by first grade.

• Dyslexia only happens in the English language- Dyslexia is prevalent in all languages.

• Trouble with learning nursery rhymes

• Struggles to learn and remember the names of the letters in the alphabet

• Difficulties recognizing letters in his/her name

• Mispronouncing and confusing familiar words

• Difficulty producing individual speech sounds

• Struggles to blend the sounds in words

• Not recognizing rhyming words and patterns

• Having a family history of reading difficulties

• Does not associate letters with sounds

• Reading errors and miscues that show no connection to the sounds of the letters

• Difficulty reading one-syllable words

• Difficulty separating sounds in words and does not understand that words come apart

• Struggles to blend sounds in words

• Difficulty getting to the individual sounds of spoken words

• Difficulty with word retrieval

• Slow progress in acquiring reading skills

• Rarely reads for pleasure

• Complains about how hard reading is and how tired they get

• Slow reading, often pausing during reading

• Trouble reading unfamiliar words

• Difficulty getting to the individual sounds of spoken words

• Stumbling when reading multisyllable words

• Difficulty with word retrieval

• Poor fluency and prosody

• Oral reading is full of substitutions, omissions, and mispronunciations

• Avoids reading aloud

• Confuses words that sound alike

• Struggles to finish assignments

• Difficulty learning a foreign language

• Poor spelling

• Reading comprehension often superior to accuracy and speed

• Slow progress in reading skills

• Rarely reads for pleasure

The Massachusetts Dyslexia Guidelines provides for all students from kindergarten through at least third grade, to be screened for reading. They use a valid, developmentally appropriate DESE approved early literacy screening instrument. If your child’s screening results are below benchmark, the student’s parents or guardians will be notified within 30 days. There will be a discussion about what actions will take place within your child’s education program. Remember that a screener is not a reading assessment, but a way to help identify those students who may be at risk for dyslexia.

parents

take if they feel their child is at risk for dyslexia

• Review the screening assessment with your child’s teacher and discuss what plan of action will be put in place.

• Listen to your child read aloud at home, and make a

list of your observations and concerns. Bring your list to the meeting.

• Have your child placed in an intense early intervention reading program taught by a reading specialist, and have his/her progress monitored.

• Set up regular meetings with the teacher to discuss your child’s progress.

• If your child is not making progress and you still have concerns, ask to have a full diagnostic reading assessment done.

• Have your child taught with a scientifically—based reading program that supports his/her strengths and weaknesses.

• Your child’s reading program should include the following components: Phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

• Set aside a designated reading time in your home to read together. Let your child select books of his/her choice and practice with repeated readings.

• Be cautious about computer-assisted instruction.

• Use every opportunity to expose your child to literacy activities

Remember that dyslexia is a reading impairment, not a thinking impairment, and that the essential of a successful reading intervention is:

• Early screening

• Early diagnosis

• Early intervention

October 2 has been designated in Massachusetts as Learning Disability Screening Day in order to raise awareness of the necessity of screening for reading disabilities and promoting an understanding around dyslexia and other reading disabilities. Y

Jill Piantedosi is an adjunct professor for American International College, where she teaches graduate students who are pursuing an advanced degree in reading. She has worked as a reading specialist at both the elementary and middle school level for over 30 years. She holds an M Ed. in education and an advanced CAGS degree in reading. Jill is nationally board certified in English Language Arts 6-8 and holds a Massachusetts reading certification K-12.

References

Shaywitz, J. P. & Shaywitz, S., (2020). Overcoming Dyslexia.

New York: Vintage Books

Sousa, David, (2014). How the Brain Learns to Read.

California: Corwin Book Company

Websites

Florida Center for Reading Research – www.fcrr.org

International Dyslexia Association – https://dyslexiaida.org

International Literacy Association – https://www.literacyworldwide.org

KidsHealth - Understanding Dyslexia – www.kidshealth.org/parent/medical/learning/dyslexia.html

Mass Department of Elementary and Secondary Education –https:www.doe.mass.edu/instruction/screening-assessments.html

National Center for Learning Disabilities – https://www.ncld.org

Parents as Teachers – www.parentsasteachers.org

Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity – http://dyslexia.yale.edu

PCD provides children of all abilities with a solid foundation for life-long learning through our educational and therapeutic programs.

MyPCD.org

Anderson School is a comprehensive approved private special education school for students ages 3-12 who have multiple disabilities, or significant, complex medical needs.

Early Intervention at PCD is an integrated developmental program offering evaluation and therapeutic services for children under age 3 who are not reaching age-appropriate milestones, or are at risk for a developmental delay.

Sibshops at PCD provides young brothers and sisters (age 6-13) with peer support and information in a lively, recreational setting. For enrollment in the 2023-24 sessions, email sibshops@MyPCD.org

Parents want their kids to have an active and healthy lifestyle and many sign them up for team sports hoping to help them develop healthy lifelong habits and a love for physical activity. While there are many benefits to team sports, they aren’t always the best fit. Individual sports can be a great alternative to playing on a team especially for kids who have ADHD, sensory processing disorder, or struggle with socialization disorders. Individual sports help kids stay active while building self-esteem and focus. They also learn to set personal goals, and have the opportunity to work one-on-one with the coach. Here are some great individual sports to try and the benefits for your child can gain by participating in each of them.

Hand-eye coordination, speed, agility, gross and fine motor skills, and strong cardiovascular exercise makes tennis a great option for kids who like to keep moving, are quick on their feet, and want the individual attention that comes from one-on-one coaching.

Kids who want to learn discipline, respect for others and themselves, balance and coordination, self-control, and work on their listening and focusing skills should consider trying martial arts. This can also become a family sport as all ages are welcome in this activity.

Gymnasts are known for their strength, coordination, flexibility, and discipline. Your child may never become an Olympic gymnast but the confidence and agility they will learn from participating in gymnastics will stick with them.

By Sarah Lyons

Swimming is a great source of cardiovascular exercise. It also promotes strength, stamina, balance, better posture, and teaches water safety. Swimming, like martial arts, is a sport for all ages. A love of a sport like swimming can turn into a lifetime source of exercise and enjoyment.

While running sports typically start in late elementary school or middle school, it is never too early or late to enjoy. Besides a great cardio workout, running helps develop physical, mental, and personal development as kids overcome challenges and set new goals in distance or time.

If none of the above sports are of interest, you may also want to research fencing, wrestling, cycling, dance, diving, or golf. Many of these sports allow kids to compete on an individual basis while contributing overall to a team. For example, kids competing in gymnastics will receive an individual score but the points go to an overall total for the team. This gives kids the support from teammates without the pressure of having to play on a team. Kids will learn to set and exceed their personal goals and also have the camaraderie that goes along with a team sport. If you notice your child is feeling pressure or frustration from participating in team sports, give an individual sport a try. Y

Sarah Lyons is a freelance writer and mom of six kids including triplets. She enjoys reading, writing, and spending time outdoors with her family.

Small Classes • Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion • Sense of Community • High Academic Standards Dedicated Teachers • Afternoon Programs • Performing/Visual Arts • Athletics • Experiential Learning

Join these Greater Boston independent schools for open houses this fall.

Meridian Academy Boston11–18y(5–12) 9/11, 6–8 p.m. and 10/14, 6–8 p.m.

meridianacademy.org

Atrium School Watertown 4–14y (PK–8)9/25, 7–8:00 p.m. (virtual), 10/19, 10 a.m.–1:00 p.m. atrium.org

The Rivers School Weston 11–18y (6–12)9/28, 12–2:00 p.m. (US), 3–5:00 p.m. (MS); 11/20, 6–8 p.m. rivers.org

Boston University Academy Boston 13 –18y (9 –12)9/28, 12:30–2:30 p.m. and 12/2, 6:30–8:30 p.m. buacademy.org Riverbend School S. Natick18 mo–14y (tod–8)10/4, (toddler–preK)11 a.m.–12:00 p.m. and 12/11, (k-8th) 6:30–8:30 p.m. riverbendschool.org

The Roxbury Latin SchoolWest Roxbury12 –18y (boys 7 –12)10/4, 9:30 a.m. –1:30 p.m. and 11/2, 12 –4 p.m. roxburylatin.org

Commonwealth School Boston 14–18y (9-12)10/6, 6:30–8:30 p.m. and 11/16, 2:30–4:30 p.m. (both virtual) commschool.org

The Learning Project Boston 5–12y (K–6)10/9, 11/13, 12/11 and 1/8 8:30–10:30 a.m. 11/1 9–11:00 a.m. learningproject.org

St. Sebastian’s School Needham 12–18y (boys 7–12)10/9, 5:30 p.m. and 11/18, 5:30 p.m. stsebs.org

Thacher Montessori School Milton 18 mo–14y (tod–8)10/9, 6–7 p.m. (virtual) and 12/10, 11:30 a.m.–1 p.m. at Thatcher (RSVP) thacherschool.org

The Woodward School Quincy 10–18y (girls 6–12)10/9, 6–8:00 p.m. and 12/6, 10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m. woodwardschool.org

The Winsor School Boston 10–18y (girls 5–12)10/15, (LS) 6:30 p.m., (US) 7:30 p.m. (both virtual) winsor.edu

Beaver Country Day SchoolChestnut Hill11–18y (6–12)10/16 and 11/6, 6:30–8:30 p.m. bcdschool.org

The Fessenden SchoolWest Newton4–15y (boys PK–9)10/16, 8:30–10:30 a.m. and 11/20, 8:30–10:30 a.m. fessenden.org Pingree School S. Hamilton14-18y (9-12)10/18, 11 a.m.-2 p.m. pingree.org

Boston Trinity Academy Boston 10–18y (6–12)10/18, 12 - 2 p.m. and 11/18, 6-8 p.m. bostontrinity.org

Noble and Greenough School Dedham 11–18y (7–12)10/18, 8:30–11:30 a.m. (MS) and 10/25, 8:30–11:30 a.m. (US) nobles.edu

Concord Academy Concord 13–19y (9–12)10/18, 9 a.m. concordacademy.org Dexter Southfield Brookline 4–18y (PK–12)10/18, 9 a.m.–12 p.m. (PreK–5) and 11/15, 9 a.m.–12 p.m. (grades 6–12) dextersouthfield.org Thayer Academy Braintree 10–18 y (5–12)10/18, 9:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m. (US) and 8:30 a.m.–11:30 a.m. (MS) thayer.org Montrose School Medfield 11–18y (girls 6–12)10/19, 1–3:30 p.m. and 11/12, 6–8:30 p.m. montroseschool.org Brimmer and May SchoolChestnut Hill4–18y (PK–12) 10/19, 10 a.m.–4 p.m. brimmer.org Belmont Day School Belmont 4–14y (PK–8)10/19, 9 a.m.–1 p.m. (in person) and 11/15, 9–10:30 a.m. (virtual) belmontday.org Park Street School Boston2–12y (tod–6)10/20, 6–8:00 p.m. and 11/5, 9–11:00 a.m. parkstreetschool.org Dedham Country Day School Dedham 4–14y (PK–8)10/24 and 11/6, 8:30–10:30 a.m. dedhamcountryday.org Meadowbrook School Weston 4–14y (Jr. K–8)10/24, 2:00 p.m. (LS), 10/28, 9:30 a.m. (MS) meadowbrook-ma.org Falmouth Academy Falmouth 12–18y (7–12)10/25 and 1/24, 9:30–11:30 a.m. falmouthacademy.org German International SchoolBoston3–18y (PS–12)10/25 and 11/22, 10 a.m.–12 p.m. (Preschool - Grade 3)gisbos.org Fayerweather Street School Cambridge 3–14y (PK–8)10/25, 10 a.m.–12 p.m. fayerweather.org

The Cambridge School of Weston Weston 14–19y (9–12)10/25, 9 a.m.–12 p.m csw.org Waring School Beverly 11–18y (6–12)10/25, 9–11:30 a.m. and 11/11, 10:30 a.m.–12:30 p.m. waringschool.org

The Chestnut Hill SchoolChestnut Hill3–12y (PS–6)10/26, 10 a.m.–12 p.m tchs.org Ursuline Academy Dedham 12–18y (girls 7–12)10/26, 11 a.m.–2 p.m. and 12/4, 6–8 p.m ursulineacademy.net

The Newman School Boston 12–19y (7–12)10/26, 9–11:30 a.m. (MS) and 12:30–3:00 p.m. (US) newmanboston.org

Kingsley Montessori School Boston 2–12y (tod–6)10/30 and 11/19, 8:30 a.m. kingsley.org Dana Hall School Wellesley 10–18y (girls 5–12)11/1, 1–3:30 p.m. and 1/8, 5:30–7:00 p.m. danahall.org

Tenacre Country Day School Wellesley 4–12y (PK-6)11/1, 10 a.m.–12 p.m. and 11/20, 7–8:15 p.m. tenacrecds.org

International School of Boston Cambridge 2–18y (PS–12)11/1, 10–12 p.m. (all school in person) & 11/13, 1–2p.m. (virtual) isbos.org

Milton Academy LS and MS Milton 5–14y (K–8)11/1, 2–4 p.m. (LS and MS) milton.edu Fay School Southborough 5–15y (K–9)11/2, 1–3 p.m. fayschool.org

Newton Country Day SchoolNewton10–18y (girls 5–12)11/2, 1–3:00 p.m. newtoncountryday.org

Shady Hill School Cambridge4–14y (PK–8)11/2, 1–3:00 p.m. (all school) and 11/20 5:30 –7:00 p.m. (MS)shs.org

The Park School Brookline4–14y (PK–8)11/2, 10 a.m.–1 p.m. parkschool.org

Lesley Ellis School Arlington2.9–14y (PS–8)11/2, 2–4 p.m. (all school) and 11/18, 7–8 p.m. (MS) lesleyellis.org Jackson Walnut Park SchoolNewton18 mo–12y (tod–6)11/6, 9 – 11:30 a.m. and 12/9, 6:30–8:00 p.m. jwpschools.org

The Fenn School Concord9–15y (boys 4–9)11/16, 10 a.m. fenn.org

The Rashi School Dedham4–14y (PK–8)2/4, 6 p.m. rashi.org

Visit school websites for details.

The schools listed above do not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, national origin, disabilities, sexual orientation, gender identity, or family composition in their admissions, financial aid, or educational policies.

By Cheryl Maguire

Igot detention for forgetting my book three times in a row,” read Michael’s text. His mother wasn’t surprised. Michael was diagnosed with ADHD when he was eight years old, and she’s received other messages saying he misplaced or even forgotten to do his homework. His mother hoped that he’d be more organized by 13, and she wonders if this is typical teenage behavior or if it’s due to his ADHD.

“Everyone has ADHD behavior at times,” says Dr. Sarah Cheyette, a pediatric neurologist and author of the book, ADHD & The Focused Mind. Cheyette says the difference between a person with ADHD and other people is that the person with ADHD is unfocused too much of the time.

“There are differences between a child and a teen with ADHD,” Cheyette says. When a younger child has ADHD, parents tend to be more forgiving and helpful with their unfocused behaviors. A teen with ADHD may want their independence but lack the skills to focus and control their impulses. This can lead to more severe consequences than when they were younger. But parents can help their teens with ADHD improve their focus.

When a teen is interested in doing a particular task, it will be easier to accomplish. “Most people become more focused when they decide they want to do something,” says Cheyette. “If you say to yourself, I don’t feel like doing this, then you probably won’t.” For example, if your teen doesn’t like doing homework, encouraging them to change their mindset can help improve their focus. Reframing the negative thought (“I don’t want to do my homework”) in a more positive light (“Finishing my homework will make me feel good about this class”) can help a teen become more focused and complete the task.

There are differences between a child and a teen with ADHD. When a younger child has ADHD, parents tend to be more forgiving and helpful with their unfocused behaviors. A teen with ADHD may want their independence but lack the skills to focus and control their impulses.

—Dr. Sarah Cheyette

Emily, a parent of a 14-year-old son diagnosed with ADHD, has found that choosing the right environment helps her son’s mindset. “I encourage him to stay after school to do his homework,” she says. “This way he doesn’t become distracted by things at home, like his phone, and he can receive help from his teachers.”

Cheyette also stresses the importance of a healthy lifestyle for improving and maintaining focus. Eating healthy, getting enough sleep and making time to exercise can all contribute to improved focus for teens with ADHD. Sleep problems can lead to issues with memory and impulse control for any child, but especially kids with ADHD.

Jen, a parent to a 12-year-old daughter diagnosed with ADHD, agrees with Cheyette about the importance of eating healthy and getting enough sleep. Her daughter experiences intense mood swings and an inability to deal with stress when she doesn’t eat or sleep well.

Cheyette says that setting goals can help teens with ADHD improve their focus and achieving their goals will help them feel successful. As a parent, you may be tempted to provide directions or nag your child to make sure they are working towards their goals, but it’s important for teens to actively set and own their goals. But you can still help them. “Make observations and ask questions,” Cheyette recommends. “If you notice your son’s backpack is a mess, instead of saying, ‘You need to organize your backpack,’ try saying, ‘It must be difficult to find your homework when your backpack looks like this’ or ‘How are you able to find your homework?’”

Once you’ve framed the problem, she says, “Ask questions such as, ‘How can you help yourself?’ or ‘How can you act differently next time?’ to allow your child to think about and own their behaviors.

Like younger kids, teens can benefit from medication. Amy, a parent of a 15-year-old son diagnosed with ADHD, bought her son a trampoline to use after school to help him release his energy. And the exercise was helpful. But she saw the most improvement when her son began taking medication. “Once he was medicated, he could use self-regulating strategies,” she says. “Before that, he wasn’t able to learn these strategies since he couldn’t pay attention.”

Cheyette wants to remind parents that you are your child’s best advocate and the parents interviewed here agree. “The best advice I can give other parents is to tell them that there may be really bad times, but your child needs to know that you are in their court,” Jen says. “When your child feels like a failure or has no friends, or school is horrible, they need to be able to come home to you and release their frustrations and emotions.” Y

*names have been changed for privacy

Cheryl Maguire holds a Master of Counseling Psychology degree. She is married and is the mother of twins and a daughter. Her writing has been published in The New York Times, Parents Magazine, AARP, Healthline, Grown and Flown, Your Teen Magazine, and many other publications. She is a professional member of ASJA. You can find her at Twitter @CherylMaguire05

When a teen is interested in doing a particular task, it will be easier to accomplish. Most people become more focused when they decide they want to do something.

By Jan Pierce

Our children have had a rough several years of learning due to the pandemic and now it’s time to re-focus on classroom interactions. Some younger children haven’t had time to experience the way a classroom normally works. How do they behave in a large group? What if they need help? What if they make a mistake? How responsive will the teacher be to individual needs? Parents can help children take optimal advantage of their learning environment by teaching some basic learning skills. Your child doesn’t have to be top of the class to enjoy learning and be a thriving, healthy part of his or her classroom.

Here are some tips to help your child be a proactive, happy learner:

Teachers notice when children come to school prepared to learn. They have the right supplies; they’ve eaten breakfast and have had enough sleep. They brought back the permission slip for the field trip and they have their lunch money.

Yes, it’s a lot of work for parents to keep up with all the activities at school. And at some point children need to take responsibility for those things themselves, but not yet. Not when they’re in grade school and are just learning how to manage responsibilities. Be the parent who takes care of business and put your child in the best position to receive approval from the folks at school.

The best student in the world can’t be on high listening alert all day long. But successful students know when to listen carefully and that is one of the most important skills a student can learn. You can explain to your child that it’s vital to listen carefully when a teacher is giving exit directions before independent work times. These times

usually come when the entire class is gathered and a new subject is introduced. Just before the children move to work independently the explicit directions are given. Good teachers usually leave written directions where students can refer to them as they work.

Practice listening skills with your children. When are the times you need them to listen and remember? Help them see the difference between casual listening and focused listening when they need to act on the directions given.

It may seem easy to adults, but children often don’t know how to follow directions. Most directions are sequential: “Get your paper, write your name at the top, then do problems one through ten.” For some children all the words get jumbled up and they fail to do the first thing correctly. You can practice following directions at home and teach coping skills if the child forgets. Listening and following directions are key skills in learning and the earlier children can perform in these areas, the better they’ll do on classroom assignments.

Continued next page >>>

Play a game in which you give two directions: “Go to the door and tap on it three times, then stand by the coffee table.” When the child can do two directions correctly try for three. Keep adding until a mistake is made. Children can become quite adept at following directions using this method.

Here is a typical conversation in a first grade classroom: Teacher: Does anyone have any questions before we start our work? Student: “My hamster had babies last night.”

This little interchange may bring smiles to adult’s faces, but it highlights the fact that many children don’t know the difference between statements and questions. And, they don’t understand the difference between appropriate questions and those that are off-task. Asking questions at the appropriate time and about the topic at hand is absolutely one of the most important skills a learner can master. It’s good to ask questions when we need information or clarification. It’s smart to ask good questions. But a child

Success in the classroom is more than achieving high marks on assignments. Just as in all of life, being a responsible, kind and caring person is just as important as being the best at what we do.

who hasn’t really mastered the art of asking will be lost, and without the information they need to do a good job. Practice asking clear, concise questions. “I understand how to write complete sentences using these words, but I don’t understand how you want me to change the action words. Vague questions like “How do I do this?” or statements like “I don’t get it.” leave the teacher wondering where to begin. Say to your child, “What, exactly do you need? And then prompt until the question is clear.

Not every child will earn straight A’s. Yes, there are average students in every classroom. And that’s okay if the child is working to his or her potential. But some children seem more adept at building relationships and maintaining friendships than others. This is the child who notices when a friend is sad or needs to borrow a pencil. This is the child who shares with others and takes turns. He plays fair. She notices when a friend needs encouragement.

Don’t underestimate the value of social skills when it comes to success in the classroom. Your child may not solve every math problem correctly, but if he is a good friend and a kind, caring person, you’ve got a lot to be proud of and the classroom is enriched. Help your child notice when others seem sad. Guide them to ways to help or share or show they care.

Practice: “Did you notice that Katie seemed sad today? I wonder if we could do something to cheer her up?” Or, “I like the way you shared your Legos with your friends. Being a good friend is really important in our family.” Success in the classroom is more than achieving high marks on assignments. Just as in all of life, being a responsible, kind and caring person is just as important as being the best at what we do. Give your kids a boost by teaching them to master good classroom skills and watch them soar. Y

Jan Pierce, M.Ed., is a retired teacher and the author of Homegrown Readers and Homegrown Family Fun. Find Jan at www.janpierce.net

By Sarah Lyons

s kids pack up their new backpacks, sharpen their pencils, and try on their new fall clothes, most start to get excited about the first day of school. While the beginning of the school year is an exciting time and represents a new start, some kids may feel anxious about the unknown. A new teacher, new classmates, or a new school can cause a lot of stress and anxiety. Using some simple strategies, parents can help prepare their children for the first day and ease their concerns.

When children are well rested and have full tummies, they are better prepared for a busy day. Start adjusting bedtime and wake up times a week or more in advance so the child has time to adjust to the new school routine. A healthy and filling breakfast starts children off on the right foot. When these needs are met, parents and kids can work together to tackle school anxiety.

Allow your child to talk about his feelings. Help him list the specific things that he is worrying about. Instead of brushing aside worry, let him know it is natural to be nervous and you will help him adjust to a new school. Try reading some age appropriate children’s books about the first day of school jitters.

Walk your child through what she can expect on the first day. Discuss her transportation and daily schedule at school. If the child has specific worries, try to address when that will happen during day. For some, role playing can help them feel more comfortable. Begin the day as you would a typical school morning. Prepare breakfast, get dressed, and pack bags as if you are going to school. Act out the child’s day and “play school”. Take turns being the teacher. Making it a game can make the child more comfortable when the real day approaches.

Walk your child through what she can expect on the first day. Discuss her transportation and daily schedule at school.

Encourage your child to meet other children in the neighborhood that will be in the same class.

Often parents are just as anxious about their child going off to school as the student. Focus on the positive when you talk to your child about school. Make it exciting by having your child pick out a new backpack, school supplies, and an outfit for the first day. Encourage older siblings to help by talking about the fun things they will experience at school. Ask your child what they are excited about. Watch your own anxiety on the first day and try to behave in a calm and positive way.

Focus on the positive when you talk to your child about school.

If the school has a “Meet the Teacher” night, take advantage of this time to show the child the classroom, become familiar with the surroundings, and introduce them to the teacher. This will allow the child to feel more comfortable in their surroundings on the first day.

When a child recognizes a friendly face in the classroom, it can make them feel much more at ease. Encourage your child to meet other children in the neighborhood that will be in the same class. Host a playdate or a class picnic for the kids.

If anxiety persists after the first few days of school, contact the teacher and share your concerns. She may have some suggestions on how to deal with a student’s anxiety and will be aware of the situation. Oftentimes, a teacher who knows a child is dealing with anxiety will give them extra support in the classroom.

The first day of school can be a stressful time. Reward your child for their bravery with a small toy, a special dessert, or a trip to their favorite park. It takes a lot of courage to try something new and it should be recognized. Y

Sarah Lyons, mom to six children, loves all that goes along with a new school year. This year she will send her daughter off to kindergarten and both are experiencing a little anxiety and a lot of excitement.

ONE IN 36 CHILDREN HAS AUTISM. WE CHANGE LIVES ONE CHILD AT A TIME.

FOR NEARLY 70 YEARS, MAY INSTITUTE HAS PROVIDED EXCEPTIONAL CARE TO AUTISTIC CHILDREN AND THOSE WITH OTHER SPECIAL NEEDS.

OUR SER VICES ARE B ASED ON APPLIED BEH AVIOR AN A L YSIS (AB A):

Special edu cation schools for autism and developmental disabilities

Center-based services for to ddlers and you ng children

Early intervention servi ce s

Home-based services

Supportive Technology services