Americans at the Poles Poems 1982-2023

Kris Piepenburg

Kris Piepenburg has lived in Palatine, Illinois, a northwest suburb of Chicago, all of his life. He is an associate professor of English and literature at Harper College, also in Palatine.

He is also the author of Crossing the Border, published in 1993 by the White Eagle Coffee Store Press, Cary, Illinois.

A postcard from American poet laureate Philip Levine (2011 - 2012), in response to the author’s earlier work Crossing the Border:

Americans at the Poles Poems 1982-2023

Kris Piepenburg

Americans at the Poles Poems 1982-2023

by Kris Piepenburg

Copyright © 2023 by Kris Piepenburg

All rights reserved.

Except for the purpose of quoting brief passages for review, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. For permissions or other inquiries, or to order books, please contact the author at krispiepenburg@att.net.

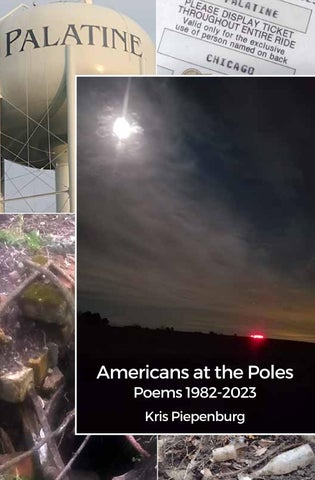

Photographs appearing on the covers and within the pages of this book are the work of the author.

Published in the United States of America

by

PAPILIO BOOKS LLC

Des Plaines, IL 60016

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Piepenburg, Kris, 2023

Americans at the Poles

Poems 1982-2023

First Edition

ISBN: 979-8-9890930-0-7

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am very grateful for the assistance of Papilio Books LLC for making production of this book possible, and for the patience, time, understanding, and support of family, friends, and colleagues as this book has been completed. I am also extremely grateful for the efforts and patience of anyone who takes the time to read the poems in this book.

Slightly different versions of the following poems appeared in Crossing the Border, published in 1993 by White Eagle Coffee Store Press, Cary, Illinois: “The Flaming Head”; “Palatine Hills Golf Course, 1984”; “The Cost of Living”; “Image Bindery: Beer Commercials”; and “The Old Men.” Also, different versions of the following poems appeared in issue number 4 of Fresh Ground: A Poetry Annual, in 1996: “Desire,” “Dome Light,” and “Last Week at the Bindery.”

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

For each poem in this book, a date of composition appears in parentheses at the end of the text. The year indicated for each poem is the year in which the composition of a poem began, and during which the primary material for a poem was created and gathered. The assembly of this collection during the spring and summer of 2023 required evaluation of notebooks of material that were filled with writing as long ago as thirty or forty years, followed by editing and revision of the selected material. During the editing and revision process, the goal was to maintain or preserve the original intent or impulse of the writing, while refining and improving its expression. In these revision efforts, I tried to avoid imposing new ideas, perceptions, or criticisms from my 2023 self onto material I had composed or gathered when I was much younger, but the experience of having lived, read, and written for additional decades naturally influenced the editing of these poems. Some older poems, however, were necessarily left alone, for the most part, as expressions of an earlier time.

Americans at the Poles Poems 1982 – 2023 Kris Piepenburg Papilio Books LLC Des Plaines, Illinois

9 Contents Desire 13 The Flaming Head 14 A Poem on the Underground Wall 15 A Dream of a Real Poem 16 An Old Couple on the Jefferson Park Platform 20 Graffiti on a Train-Car Seat 21 A Dream of Being White 22 Real Commuters of Chicago Suburbs (1982) 23 Real Commuters of Chicago Suburbs (1983) 24 Real Commuters of Chicago Suburbs (1986) 27 Dawn in Chicago 29 Club Disc Jockey 30 Costs 31 Jury Duty 32 At a Mopar Junkyard 33 How Did This Happen 34 How Does a Person Go There 35 A Dream of Being a Woman 36 I Will Live Better This Way 37 Interruption of Clarity 38 Fixed 39

10 The Old Shed 42 Passing Beside My Sister 44 Above Ground 45 Four Generations in the Bay Area 49 Grief 53 East Troy Railway Museum 58 Springfield 1: Exploring The Air Line 60 Springfield 2: Party on The Air Line 61 Dome Light 64 The Folding Table in Fox Lake 66 Long Valley Apartments 67 Cut Off 68 Palatine Hills Golf Course, 1984 72 The Cost of Living 73 Second Grade, Palatine Public School 74 Fake Writing 77 Hall Monitor at Conant High School 78 Image Bindery: Beer Commercials 79 Last Week at the Bindery 81 The Old Men 82 The Right One 85 Independence Day 88 The Capodimonte Crown 93

11 Americans at the Poles 94 How Much Longer Manhattan Island 98 On the Inside 102 The Northern Lights 105 Lunar Eclipse 2008 107 Another Lunar Eclipse 112 First Covid-19 Vaccination, April 2021 115 A Mundane Dream of What Humans Became 116 Investment 117 Café Fourteen 119 The Man in My Charge 123

12

Desire here on this muddy hill: scrape if you will, if not the string’s simple drone, a hoarse cry, some valved horn’s uneven blast

(1984)

13

The Flaming Head

Torched by lightning in damp night air, my head split into fire. By day I wear a hat, stagger in heat and smoke from under the brim. Nights, a breeze stirs the bare embers into tongues, when I walk streets,

The Flaming Head of Palatine, Illinois. (1984)

14

A Poem on the Underground Wall*

It was a mystery, the poem on the underground wall, and I kept the volume down, when anyone was home. What I envisioned then, a wall like the ones in my house but underground, incomplete, worn, a partial foundation, and somehow I was there in the ground, could see the red brick, the gray mortar, crumbling dirt. The damp tambourine splashing along the words, their music, their rhythmic wet sibilance, and the idea of a poem, the impossibility of a poem, words written on a wall, underground: bent in stillness to the sound, what I’d found, my sister’s music but my own, a secret, a rosary, a litany, these words unknown, a poem on a wall underground— the movement, deepness, dampness, darkness of it, what I felt and understood of it. I asked no one, told no one anything. The words were my mystery, and only mine, and the song was mine, and only mine, and what I felt and saw was mine, and only mine.

(2021)

*The title of the song written by Paul Simon, performed and recorded by Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel and released in 1966 on the album Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme.

15

A Dream of a Real Poem

for Ralph J. Mills, Jr

Surface and texture, three dimensions, moss and rocks, tree roots exposed below as when a stream undercuts the soil; and a recess in the dirt, a tunnel, a river going underground. This tunnel: you’re communicating with those down there, or you’re in there, or you’re writing from there. His fingers run through moss, absorb water, texture. (1984)

16

19

An Old Couple on the Jefferson Park Platform

Cold, he spits onto the ties, and it lies there, steaming, still living. Turns to his wife, you worry about things that sometimes never happen. (1983)

20

Graffiti on a Train-Car Seat

John Lennon Lives was scratched into the metal seat back, and others added who cares and in the graveyard (1982)

21

A Dream of Being White

Scores of young black men rove a whole city block. A chalk line is drawn along the curb, and I am forced to walk on one side of it only, down the middle of the street. I ask someone who smiles if this didn’t end a long time ago.

(1984)

22

Real Commuters of Chicago Suburbs (1982) Inbound, Northwest Line

Their morning platform friendship has been long: two thin trench coats, one dark blue, another light gray, hems flapping, and one heavier overcoat, light brown, hanging with weight. They sway with articles of personal use— the battered attaché, folded umbrella, plaid thermos— and step slowly onto the exhaling train, in the rhythm of decades, for their sons, daughters, wives, homes, cars, lawns, clients, companies— the oldest limping, wearing a wrinkled wool hat, an inverted bowl, grabbing the handrail, another white-haired, pink-skinned, the third, kinky black hair, dark eyebrows, glasses, reddish face. As they file in to sit in different areas of the car, alone, the dark-haired to the upper level, I hear see you tonight, Ed, from under the wool hat settling near me and okay, Burt from behind an opened newspaper held out firmly there already. (1982)

23

Real Commuters of Chicago Suburbs (1983)

St. Patrick’s Day Afternoon, Outbound, Northwest Line

A big, heavy guy wearing a green hat and standing holds court from near the exit door, facing the whole train car of seated people— this radio still works—I’m surprised— I dropped it twenty times before I left Chicago—

Then with an unlit cigarette in his mouth picks out a darker-skinned man, tanned, relaxed, leaning back in his seat, maybe 60 years old, aims himself at him— y’know, they’re thinking of changing the alphabet. From twenty-six to forty—

I’m next to the seated guy, taking notes, waiting— he plays along—

my opinion is that we have enough trouble with 26— 26 what? Girls?— letters of the alphabet—

y’know, you look like you’ve been through a lot of Hell yourself. What do you do, besides nothing? I try to get along— smart man—y’know, I was a prisoner in that Vietnam War—they fuck people up, that’s what they do— they destroyed my fuckin’ mind— I’m scared—it’s gonna be Hell—

24

why should I be shot, when a fuckin’ prick like you should live? I served my country with honorable discharge and everything—what do I get, a kick in the fuckin’ ass—yep, a kick in the ass—god damn, they fucked me up so good I don’t know if I’m comin’ or goin’—

A pause, at Cumberland Station, some passengers leaving the train, a few taking seats— hey—you want a half dollar?

He whips it over to the man, who puts up his right palm, catches it deftly— pretty good!

The man gets up, hands it back to him— it could be your lucky day— lucky day? Well, I got a rope in my bag. I’m thinkin’ about hanging myself. I don’t know what to do. I thought you were a psychiatrist or somethin’—

I’ve seen things from many point of views—I’ve seen things from many points of view—

I found this radio in the garbage can— I bent the antenna when I dropped it when I was drunk—it still works— I dropped it twenty times—I’m going into the world of the unbelievable—

25

(1983)

it’s better to believe—

I love God, I’ll tell you that. it’s a good place to start. yeah, I don’t love God, I worship him— you must be a psychiatrist or something. What’s your occupation, anyway?

I’m a manager. what?

I’m a warehouse manager. nah, not the way you’re dressed— well, that’s just a point of view— nah, you can’t fool me—you’re a psychiatrist— well, I know about being sick— you were sick once, too? You’re a good man. How come you can smile all the time when I can’t find one? the price is right

26

Real Commuters of Chicago Suburbs (1986)

Outbound, Northwest Line

when they quit workin,’ what are you gonna do all of a sudden?

I think there’s certain things that have to be decided—I get done with breakfast, there’s some dishes to do—it’s agreed, Joan does the dishes—I’m gonna pay the bills, I say—she says, let me pay the bills— she finally got up and did the dishes— the thing with Nancy is, I don’t trust her— yeah, I don’t trust Joan to do bookwork— you gotta love her, though, when it comes to cards and a stamp— certain things can stick in your craw— we remember what mom did and stuff—

I don’t want sandwiches two nights in a row— my wife cuts the grass sometimes—but I’m worried about her feet going underneath the mower—maybe I oughta buy a tractor mower—

sometimes I wish we didn’t have a TV, I really do—she’ll watch anything— yeah, in the evening sometimes we go through the channels—but our life is work—if we’re not cleaning something, like cleaning out the sideboard, or cabinets, we’re not doin’ nothin’—we’re not sittin’ in the living room— yeah, Nancy does a pretty good job cleaning out the cupboards—and cleaning the bathroom—

27

the shower stall—the bathroom cupboards—

I couldn’t believe these guys I hired to put in a new shower door—I had to tell them where— this is the showerhead, and the door goes right here—you know, that’s gotta be done right, the seal’s gotta be, the seams gotta be smooth, otherwise you can’t get in there when you clean, you get that buildup—

yeah, I know, the last thing you need is that mildew—you use a fan?

oh, yeah, it doesn’t even build up steam in there—

well, keep an eye on those corners—the last thing you want is that wallpaper bubbling—and new wallpaper, what that costs—you’ve got a business to build up—

oh well, you can’t get everything in life— no new car until 50 Gs in your account— then you can breathe—

(1986)

28

Dawn in Chicago

the restaurant parking lot here is swept at five am by dark-faced men wearing caps backwards and untucked brownish-beige button-down work-shirts with stitched-on nametags, laboring at dawn, crunching the debris, the broken glass, scattered loose gravel into arrangements of mounds, then leveling them with a scrape and slide of a shovel, draw of a broom, lift and tilt into a bucket, moving quickly, purposefully across painted yellow lines

29

(1982)

Club Disc Jockey

The car salesman talking to me, he wants to fuck that girl. Asks me do they put out here. I say yeah, yeah, there’s some nice girls here— yeah, nice girls— do they put out—. He’ll never learn. Going bald. Just over the space of months, looks older each time he visits, more desperate. Sold stereos before, now selling cars. Want to be a DJ?

30

(1982)

Costs

Denny’s restaurant, noon, the restaurant manager weighing portions for a line cook: is that four ounces? Now that looks like four ounces. This one looks like seven ounces. Right on the nose, he says, right into my notebook. Still going on about four ounces versus seven ounces: I’m not trying to embarrass you. Heavy burgers versus light burgers. We’re looking at our costs today. We’re determining where we’re running high. The cook, bushy dark hair under a green cap, rubs his left temple, hears about the French fries: and if you don’t throw ‘em on the floor, we’ll save even more.

(1994)

31

Jury Duty

Two retired white guys bond on a big day out of the house for them, downtown in a room of hundreds who heeded the mailed summons, Cook County residents come to serve—the stuff they flush down toilets to kill tree roots blocking the pipes, the ten-year-old sedans with low mileage that they find, the taxes they pay when they buy them, the medications they take, the Cubs. In earnest, across a wood table, their hands moving, bright eyes open to each other, backs straight, virtues of good hard-working men, lunch buddies in this room who might agree on a verdict, as they agree on life—maintain, fix things, buy things, keep moving, keep the shit flowing through the system, catch a ballgame.

(2005)

32

At a Mopar Junkyard

The rotted Plymouth Fury rises high, steeply away on a forklift, pushed to the sky, then lowers in jerks, shakes earthbound, hood and trunk wings flapping, the whole body sagging, showering flakes of rust. A guy with a Chrysler 300 wanted to see under the Plymouth, the suspension and frame, but he couldn’t use it, now it’s back down, and he still wants a look under the hood. This man loves cars, all stories of cars, wonders what he could get for his Chrysler. The forklift operator says the only thing I have a choke on now is my snowblower. The guy with the Chrysler says or on your wife, you know, you put a choke on her when you want to play with her. We don’t laugh, and neither does his son, standing beside him. (2006)

33

How Did This Happen

In the weeds, the laying down came easily. Behind here, the mired foundation of a house, and a woman’s things strewn: cosmetics, cooking utensils, a tin of cinnamon, romance novels and a water-rippled copy of Rich Man, Poor Man—and an old mattress, refrigerator, clothes dryer. Your question, how did this happen, goes unanswered, and you close your eyes on the bright sky above and clench the dark stubble of last year’s growth, beneath new green weeds. (1984)

34

How Does a Person Go There

It is too soon after winter to be comfortable out here, walking a fragment of an old wagon road that appears most clearly in early spring in these woods, when the ground is first thawed and soft. Small streams of water on either side of the old route, downhill through trees and brush grown in its path. I am here again too early, impatient for warmth, life, in stinging chill, late afternoon, gray light nearly gone, about time to go home, but tracing familiar points along known lines— trails, swamp edges, the wagon path gradually blending with the forest, wondering how a person goes there, to a blended state, abandoning the lines, the things, the names, maybe by sinking into the past years’ black leaves and sleeping, breathing their dampness deeply— how does a person go there—

(2006)

35

A Dream of Being a Woman

Breasts flap and point, brown nipples I fondle, amazed to have become a woman. Between my legs is also different, sensitive, moist to touch. As a new woman the first thing to do is masturbate.

(1984)

36

I Will Live Better This Way

The swamp grass bends with the shirt where I’ve thrown it, after pulling it over my head. The pants wrinkle and drop to the dried reeds and water, a pantleg at a time going dead and hollow without me as I lift one limb, then another, unhooking the waist off my toes. The underwear slides down, a bare wisp of fabric foot-flung to the water. Now I squat down, press my asshole, balls, and heels into the mud and shrink.

I am now a frog. I will live better this way.

37

(1997)

Interruption of Clarity

an interruption of clarity— a bright green katydid lands on the globe of the kerosene lantern and wags antennae over the lighted, heated glass—

(1982)

38

Fixed

Opening the car door in a small woods, I heard the song of a strange bird, saw it hopping branch to branch in a leafless screen of bushes, silhouette in a mesh. The door hanging open, my leg halfway out and stopped, thought and breath suspended, waiting and watching, all for a moment fixed. (1992)

39

41

The Old Shed

In Reedsville, he built the church: and before the steeple went on, he stood on his head where the spire would go, waggled his legs all around, through fierce blue eyes saw the town and people spread out below, weaving upside down. With this it began, and from there they went, forty miles north to empty land in Gillett, where in winter the snow blew through cracks in the small shed that stood on that land, dusted my grandfather and younger brother as they slept, small children dreaming, maybe of the home they’d left for the old shed, before their father built a house, a barn, before one of them lost his young wife to exhaustion in Chicago, remarried and in middle age sought perpetual motion in gears and pipes in the garage, running them off the car’s rear axle—and before the other drifted on ships, tended lighthouses, gardened on the White House

42

grounds, before his nephew read Tom Swift and built radios in his basement all his life, in lead solder fumes and tobacco smoke, colored my air with bullhorn dogma, endlessly black or white, German or Jew, before I became small, before I became tall, before my daughters.

Clarence, the other, now years rejoined and resting with your brother under the snow, I should have asked you if your old man born 130 years ago beat the hell out of you 80 years ago and strutted and spewed miserably alone, and if you carried it around the world with you and returned much later to your family home, as I have to mine, to try to live there, still cold as in the old shed.

(1994)

43

Passing Beside My Sister

Five am, end-table lamp glares in barest dawn and cigarette smoke, bits of yarn on the floor, pieces of a rug kit, humped-up rumple of blankets on the couch, a mug with a trace of milk rippling into skin.

She sleeps with the light on sometimes, in a room where she dreamt our father stuck his head through the heating grill, the ventilator, as she put it, to talk to her. Daytime, the kitchen table, pack of Winstons, and I often ask if she’s eaten. We live here still, with our parents.

I thump to bed up the staircase our father finished when I was so small I had to squat to go down the steps. Birds are chirping in the beginning daylight. I’ll be sleeping a lot of the day.

Our lives run parallel, meet at narrow moments.

(1982)

44

Above Ground

Driving Milwaukee Avenue again in November, the trees stripped, leaves swirled around and settled along fences. In nice clothes and shoes, overcoats, for a funeral, southeast, gently downhill again, houses alongside looking emptied, flattened, suburban shacks scattered across dirt and rock, a blank place passed through so often, television aerials and one-story roof after one-story roof behind long wooden back fences, at the dirty grass edge of Milwaukee Avenue, full of rags, crumpled bags, empty cans, bottles thrown years ago sunken into their own little hollows, grassed and silted over, words on street signs once pronounced carefully, silently, wondered over with each passing now gone to tiny scraps in a deeper horizon, small names of small places where someone can spend some time— Glendale, Burning Tree, Pima, Dearlove, Thornberry, mistaken years ago for Throneberry, a thin white tag tilting in space,

45

black letters blankly stating a nonexistent tree or bush for this thrown-together place—yards crowded with sheds and toys, little clusters in flat dirt plains, where people stay warm for a while. Oconto, Octavia, O’Dell, Oliphant, Oriole, Ozanam, Ozark—names clicked off in the mind by a child learning to read, every time, secretly, silently, and loved for themselves, their sounds, the inlets off Milwaukee Avenue, of small lawns and awnings, rooms in six-flats holding something for someone for a little while, as names hold something for someone for a longer little while.

The cemetery roads curve, circle, braid, lead nowhere but back onto themselves, flowing, branching, re-branching— a place spaced off and spared, well off Milwaukee Avenue. Here, visitors will not abuse their wives, will not swear at the driver ahead, will not criticize a husband’s driving, will not chew out a sales clerk, will not shoplift, will not floor the gas pedal, will not throw

46

garbage out the window, will not blast radios, will not flip up middle fingers or smoke tires, will not slide and careen into violence, will not be sickened with more visual memory, the familiar slow four lanes, traffic, and buildings, amorphous rubble all the way down the old glacial lakebed, will not sort through the clutter for heart, pink-lighted signs flickering at night, White Horse

Motor Inn Vincent’s North—Fountain

Creations Vegas Motel Superdawg

Go to Blaze’s

fail in listening, will not fail in thinking, will consider another.

All those weekend miles down the Avenue, stopping at the bakery but not once at Ridgewood here to remember our grandfather

47

will not will not will not will not will not

dead thirty-five years. When they’re buried, they’re gone, and we never return, unless to bury someone else. Then, we circle the roads, go and look, connect again, look cautiously around at the members of the group, each one alone in grief, in view of Milwaukee Avenue beyond the evergreens and fence, staring away or looking down. Standing alive above ground, we’re gone, dead before a stone.

(1995)

48

Four Generations in the Bay Area

August Piepenburg, music teacher and member of the Grand Army of the Republic, was found collapsed, dead of a heart attack in an outhouse behind a tavern he owned, Oakland, California, 1889, 48 years old, leaving a wife, two daughters, two sons. August’s son John was six years old when his father died, finished eighth grade, had a business called Piepenburg and Kearley Jewelers, with a neon sign my father Martin remembered seeing from an Oakland streetcar during the 1940s, his Merchant Marine years. John and his wife Mary had one son, Galen, a pipe organist and music teacher, never married, played at the wedding of his sister Virgil Jean, known as “Bunny,” graduate of The California College of Arts and Crafts, married in their Oakland home to Dalton Wrixon, had a long career as a commercial illustrator for the Oakland Tribune and as a freelance artist, and a daughter, Gale Wrixon, graduate of Piedmont High, 1958, attended San Francisco State and the Pasadena Playhouse, employee of KPIX, the San Francisco Chronicle, staff writer for the television department, married late to much older Howard Sutton, his second wife, no children. The other three

49

children of the dead patriarch never married, so here this line ended, April 30, 2009, graveside services for Gail Wrixon, Mountain View Cemetery, 5000 Piedmont Ave, Oakland, with donations to Guide Dogs for the Blind or other charities in lieu of flowers, four generations’ art, beauty, music, interaction with thousands around San Francisco Bay and Alameda County finished. My father Martin’s second cousin Chester Piepenburg, now 95 years old, son of Albert Herman Piepenburg, died 1941, one of six children of my father’s great-uncle Anton, died 1888, whose family settled in Exeter, California, remembered picnics somewhere in Oakland where he was told Galen and Virgil were his cousins, but no one explained how, and no one knows, still. Dad’s first cousin Lyle Piepenburg recalled in the late twentieth century how Lyle’s father Reinhold, Ford dealer in Reedsville, Wisconsin, remembered his father Frank, of Rantoul Township, Calumet County, speaking of an uncle, Gottlieb’s brother, a phrase my father spat out often, in compulsion, retelling this story, trying to sort out his own, fancifully imagining a farmhouse porch, men talking in the evening (remember Gottlieb’s brother?), though this brother was most likely Gottlieb’s son, Frank’s older half-brother,

50

from Gottlieb’s first family, left in Germany, 1856, come to America but not long for Wisconsin, gone into family legend, possibly, the Civil War, a tavern at 1161 Seventh Avenue in Oakland, then through the door of an outhouse, still three generations of life ahead.

(2023)

51

I am too old to be the child of parents anymore, nodding along to their stories

my father’s mother’s death at age 28, he has carried and told all his life, in details fixed from the age of five some are new for me in this telling, his eighty-eighth year, the room’s light darkening with evening—

she had a problem with miscarriages, he says, and I remember her walking around carrying something on a piece of tissue—this was three months after my sister was born, and you remember my younger brother Roger only lived ten days—

he had my father’s wavy hair, nothing like mine—yes, I remember Roger, seeing his grave, or tombstone,

as my dad would’ve put it, in the Reedsville cemetery, and the shock of his existence to me, at nine years old, and at the fact

53

Grief

of a child’s death—yes, I remember Roger— and how a fearful thing flooded into me then, sudden, swelling into my eyes, trembling into my face— and how I turned my head, stayed quiet as we walked, then drove away—

yes, I remember Roger, just one of two or three who do, and I don’t anyway really remember his ten days in a body, ten days,

or what those days and weeks and months and years may have been for his mother and father—this is the best we’ll do,

talking about it, the best he can, the best he ever has, probably, because he knows I’m the keeper

of all that he remembers, all that he tells me—at fifty, I am too old for this, cannot listen anymore, but cannot not listen—I never knew my mother as a person, he says, but I remember when she was

in the hospital, her getting up from

54

the bed to go to the bathroom, and the funniest thing, I remember the line of green tile that went around the room, along the wall, and Grandma Otto was there, and Aunt Adeline, and Aunt Adina, I don’t know how they got there, maybe Grampa Otto drove them to Milwaukee and then

they took the train to Chicago—still remembering, imagining, constructing— what his child’s eyes must have seen—

his comprehension, incomprehension, this was his mother getting up to go to the bathroom some days

before leaving this world, leaving him, her infant daughter, husband, parents, sisters, all forced into early

abandonment, adjustment, the grief of a close farming family, their American children growing too soon,

leaving home, moving to cities, dying there way too young to have

55

known much but beginnings and suffering, cold, rented houses, the realities of young marriage, male ambition, single-mindedness, the wife a helpmate, home-body, bearer of children, griefs and losses

Martin’s got wires running everywhere, the only actual spoken words of my 28-year-old grandmother that survive

in her now ancient son’s memory— she’d been speaking to Grampa and Grandma Otto, her parents, when they visited Chicago,

of her husband’s mania for radio, one of the new excitements of the world, another way to hear different voices and music, more sounds of life— (2011)

56

57

East Troy Railway Museum

This railway memory begins like others, with the ankles, coarse quartzite ballast crunching underfoot--up the tracks to a snow-domed leaf-green trolley car, not sure of our luck this early April, with the wet snow, the cold, the museum closed, but the empty car here and warming, the door folding open for us, the plate above the steps rising. In the cold coach, worn woven seats, smells of old cloth, rubber. Two men work the aisle, front cab to back, heavy coats and boots. The car stalls right after it starts, lurches, grinds, shudders, whines at iced spots in the power lines. Rough clothes rub and brush along the aisle, the boots tromp and thud in snow-slush and rubber, the slubber, the gritty slobber of spring and winter mess, loud voices calling OK from car front to back at every stop, grind, and jerk, overhead lights spurting

58

on, out, toes cold in my shoes, feet seeking heat under the seat ahead, my father’s stiff back sideways against me, his talk, his continual expressions, head-turns, hunches and glances, pointing, satisfied as we squeal out into a smooth run, whirring, whining, clicking and clunking along, snow-dusted black-barked branches bursting powder at the windows, the view opening into the brightness alongside a highway, the four of us lit up and alive, really moving, feeling the sun, motor humming, now we got some heat, he yells, and then back into the trees, to the end of the five-mile line and smoothly returning, a test run in the early spring. In a restaurant in Elkhorn later that day he told me I’m glad you like bumming around.

(2001)

59

Springfield 1: Exploring The Air Line

You’ve done it again, my brother— taken me down a railroad line left as prairie, rails and spikes rusted, signal wires cut, ties dried and split, trestles unsafe, to imagine a train on a line that hasn’t smoked or whistled since Eisenhower built German highways. You’ve taken me to taverns of friends drinking, smoking, hollering along with Folsom Prison, and at home, we’re up late with music, memory, talk, creating steam coal smoke and soot trailing above railside scrub, out and through life and towns, joyous time and space.

I wake shaking with the Chicago-Alton line, in the press of the dark, the only passenger, blank-eyed as the places and stations erased,

Huffaker Prouty

Knapp Rees Station Cockrell Yeomans Clements

the tiny names alive in just their sounds now, the places nameless foundations, pointless junctions, dirt mounds until Murrayville.

Today, how we found the Chicago-Alton’s Air Line to Kansas City—purple quartzite rustling, shifting under our weight, rails visibly rippled in the long out-bending curve, pinching together, trees on either side closing down, all growing smaller, blue sky filling in, sleeper cars and coaches, our imaginations reaching into the sun.

(1998)

60

Springfield 2: Party on The Air Line

From the bars, they loaded up with cigarettes and coolers of beer, headed by the hundreds to where a crane had pulled and dangled the cut rails and ties of the Kansas City Air Line from a Southern Pacific switch. They brought their guitars and shouted on down the line, stomping and singing, vibrating, shaking, telegraphing to Kansas City 400 miles away, bringing a light shimmering low at the horizon, a corona just above the rails, growing slowly larger, more true, more round and strong, beaming joy down upon them scattering, sliding down the rocks, fists in the air, whooping and hugging in the gulleys, that their bringing so much life to the party could allow the dead to pass in return.

(1998)

61

63

Dome Light

baseball of interest this evening in the parked car that won’t run right

and now it’s three to nothing and Whitaker winds up at second base and Davis continues to have problems in Chicago

once again out on the mound, talking to the righthander—

that leadoff walk’ll burn you every time now this is it now a four to nothing ballgame, Detroit Sheridan with his forty-seventh run batted in of the year

got the dome light on in the Mercury Comet and this is it

relief pitcher Joel Davis, destined for short career, serves up familiar leadoff walk and the announcer serves the warmed-over maxim that leadoff walk’ll burn you every time

64

after a hit and another opposing run scored the disgust rises through now a four to nothing ballgame

and this is Pat Sheridan’s forty-seventh run batted in of the year, if anyone is keeping a notebook (1988)

65

The Folding Table in Fox Lake

whenever I drive through Fox Lake and see the Dairy Queen on the west side of Route 12, I remember the time I sat in the driver’s seat of our parked family car on a side street, waiting for my wife and children who were getting ice cream, and I watched behind me and uphill for quite a while the passing and repassing geometry, the contorted drama in my inside rear-view mirror—two or three older women making multiple attempts in different ways and arrangements of themselves to put a folding table in the trunk of their car

(2023)

66

Long Valley Apartments

I just want to fucking die, she said, in their basement apartment, and I heard her, from the firstfloor apartment, where I wanted to fucking die, too, and where I wondered what she’d seen in the red-faced sun-worn alcoholic carpenter who was fucking her cousin when she wasn’t around, and what had happened for them in Louisiana before ending up married here. Her wealthy old aunt and uncle would roll up sometimes, slowly in a long white sedan, from Arizona, the trunk lid popping, goods being lifted out, stuff for their pretty blonde niece, who was no idiot, took college courses, read literature, the man gave me an A, she said to me once, but she just wanted to fucking die, with her two young daughters there, the love and life she had made, what she wanted or thought she’d wanted and the results of that, or what he wanted or thought he did, both of them just wanting to fucking live, what I wanted then, too, not realizing it that way or that I already was and knew very little about what that meant.

(2021)

67

Cut Off

a stop sign on Stark Drive, in dark heat, full-leafed maple shade, thick air a round shadow turning in a living-room window

the woman in red pajamas at her second-story window, raising it, blurred television bubbling color on the dresser

black arms, rhomboid bodies of backhoes in a clay field like an abandoned mine, lighted new Monopoly houses strung along behind

the two paintings of heaped bowls of fruit, side by side on a living-room wall on treeless Home Avenue, giant grapes and lemons for those who live there, stuffed toys poking from a box on a second-floor closet shelf

the frosted glass panes framing an entryway on MacArthur Drive, Willow Wood subdivision, gold jelly glow lets nothing in or out

68

my eyes headlamps fire-holes draining in, respirating light and dark, pedals cranking, near flight, two flaming wheels, body lit and burning the puke-star in the Denny’s parking lot, caseous splatter, crater rays of chunky white

the group of five middle-aged men and women in a ring booth at Denny’s, mouths moving in Os and hearts, heads turning, here after something, talking

the Office Warehouse workers unlocking their old cars in the dark, the Office Warehouse manager locking the fortress doors, pulling on the handles

the promise of searchlights beaming golden into the sky at Laredo Plaza shopping center, stores closed, nightclub open

69

bare yellow octagons of light stairwell windows at Baldwin Green apartments, three per building, buttoning up the brown oblongs, balconies of grills, toys, bikes a voice from behind a board fence, Windhaven Apartments, calling to a window Hi, Destiny Hi, Destiny

the guy with flapping shirt and drag-ass pants, waddling and shoving to the huge dark windows of Home Depot, stubborn steel worm of shopping carts a massive erection at his hips

his Indian partner at the lot perimeter, walking fast, hurry and worry in his eyes— whatever could his job be, out here, now the rush and low flight of a kildeer brought up from curbs, clay, weeds, my wheels trembling through the asphalt to its home, built on the ground

70

tying my shoe under a parking lot lamp, then standing, surveying the mile of closed buildings, stores, like looking at a canyon vista, braced for discovery, still with the stance and breath for it the round pale watermelon moving up the rubber check-out belt, wobbling slightly, bought late by a lady in the grocery store’s aching light

the thin father, pale face and oversized blue eyes like coins, belt yanked too tight and high, bored, tired, and waiting

the small girl kneeling on the floor near the exit, tracing her pink finger along the Lucky Rings inside the glass 25-cent toy machine, looking around for her parents

71

(1997)

Palatine Hills Golf Course, 1984

Dug up a skeleton today, in dense woods bordering the golf course, deep shade of staghorn sumac and scrub, downhill rills in the clay filled with early atomic age garbage—soaked, stacked newspapers, three decades old, the Sunday comics still bright in color, horror of the bomb and former President Truman in thick black headlines rising with the gas of damp and earth, over the ribs and vertebrae of a mammal, some ruststained soda bottles. A pause, a decision, with this skeleton. Golf balls are here, too, white hard post-nuclear mushrooms sliced in from the third tee, scattered over dead branches and leaves, bare clay where not much grows, so dark in this dry shade, in this garbage. The brightly dressed men out there in the sun raise clubs on the fairways and greens, gesture to each other, sweat, talk, swap bets and stories, ride quiet carts from tee to tee, hole to hole, then have drinks with lunch.

(1992)

72

The Cost of Living

The past few years, this town has been a maze of streets where I jerk awake, becoming my father: the post office, the doctor, the paint store, mechanic’s, the lumber yard, hardware, pharmacy, gas station, village hall, destinations all for getting somewhere else. I want to touch it, put my legs down hip deep in the swamp behind the old town dump and wade, I want to break off the cattails, eat them, storm through in my soaking pants, a monster, swamp creature with letters to mail, roll down the cemetery hill and walk like a dog around this town, eat dirt, smell the hydrants, where people have been. My breath smokes out the rolled-down window. I mail in the bills and drive home, in my steam. (1992)

73

Second Grade, Palatine Public School

So moving to see or remember children assigned responsibility, feeling important, wanting to do things right when given jobs, respecting adults, still too young to ridicule, oppose, question the need for public systems, contributing quietly, reverently serving an afternoon snack to the classroom, second grade. In 1968, a half-pint of white milk in the afternoon was an option for children’s parents who would pay, and a new milk boy and girl were chosen for the week to go downstairs to the cooler, load cartons onto a tray and each take an end, balance the milk up the stairs and down the hall to Room 2. Married that week, hushed and serious together, blonde Judy Milas and I carried the tray, with efficiency made the deliveries to each desk, straws and small cartons the same style the entire year, not peaked roofs but flat—little red, white, and blue square wax-coated milk-filled cardboard blockhouses with American presidents’ pictures on their sides—Washington, John Adams, William Henry Harrison— and I knew Harrison died a month after being elected, I knew that then, knew

74

the presidents’ faces and names through Eisenhower, had studied my oldest brother’s stamps before I could read, but the stamps were old, so I did not know of Kennedy or Johnson but learned of Nixon, Humphrey, and Wallace in other ways that year, had heard my brother saying McCarthy. Nixon won in Miss Zender’s Room 2 mock election, with seventeen votes, Humphrey had eight, and Wallace one, and though at dinner my dad had shouted his hatred and banged his love for Wallace, that vote was not mine. We took the mock election seriously and quietly, as seriously and quietly as we carried the milk up the stairs and passed out the cartons, and I don’t remember anyone not receiving milk— there would be no poem about that, there and then, in Palatine, and we did not know places where children did not get milk. At Christmas time, we sang carols for elderly women brought to school from the nursing home, and we dressed nicely, formed up, straightened up to sing, politely ate sugar-sprinkled cookies afterward with the seated women of the nineteenth century, and we spoke softly, answered questions and behaved maturely, the women probably moved as I am by children singing, serious

75

children serving. Had we been called on as seven- and eight-year-olds to know of other things, to serve in other ways, I have faith we would have done so, then, with our seriousness and respect, because it was the right time in our lives, but five years after John Kennedy, months after his brother and Dr. King, we were taught nothing of them, felt nothing about them in school, had to feel that very faintly through older brothers or sisters, if we had them, or not at all, and we studied the Apollo astronauts, gathered in reading groups, sat at our desks, learned to write, to add, subtract, to be organized, respectful, to work alone and together, and though it was never put to us this way, and I doubt Miss Zender, Mrs. Hans, Mrs. Richardson thought of it this way, white men would walk on the moon very soon. (2023)

76

Fake Writing

you called it fake writing— the third-grade state of Illinois prompt, why school uniforms are good, not good fake writing you called it— thank god my daughter

I love you, your amused and righteous disgust, already, third grade (1995)

77

Hall Monitor at Conant High School

In the pale-green cinder-block halls of the second floor, I hear the astronomer talking of the sun’s angle at Antarctica as the Earth spins, and the history teacher, by the time of the Philadelphia convention, and the massive fire doors of the hallways are propped open strongly on this warm Friday afternoon for the flow of young people that will pass through quickly. (1997)

78

Image Bindery: Beer Commercials I

Here’s to you, McLean twins and Standiford brothers, overgrown kids I worked with one summer, you got drunk every lunch as a group, worked the vacuum sealer, the silkscreen machine, the round-corner drill, the glue table, pounded rivets to put rings into binders, shouted around in roar of machines. Yes, we went to the same public school, you’d seen me, didn’t know me, never did, never will. You quit, Mark, in disgust, after seeing Dan kiss Jack’s ass for that supervisor job. Took you a while, but you quit, surprised everyone, Dick the owner in shirt and tie even came out said we’ve been glad to have you work for us and if you ever need a job. I was there for the handshake and pat, was just getting to understand you, big dude who could lift more than anyone, drink more than all of them, told a story about a girl’s hair sucked up and caught in the glue machine rollers, the machine bouncing off the floor until Dan shut it off, got the scissors. Here’s to you.

79

That riveter, they called him, bearded and beat-up, told us about a girl he took home threw up all over everything, she had a Whopper for dinner, and clean young Jack leaned in, the owner’s son-in-law, to his scars and pocks: let’s have less talk and more work. Drove up to the rear dock door a week after being fired, head out the window of a throbbing green Pontiac idling oil smoke in the alley, told the story, got a job at the silk-screen place down the way, got a good reference from here, but couldn’t talk less or work more to suit them. Fred, you made that rich suburban jerk of a kid feel right at home here, the kid they put out sawing wood in the alley his first day, the one the McLeans and Standifords couldn’t believe was dicking that girl, the neighbors’ beautiful blonde older daughter, Spinnaker Cove, even encouraged his catching some rays bullshit. You were cooler than that.

80 II

(1992)

Last Week at the Bindery

the shift boss dragged a drumful of residue, old glue, halfway to the loading dock, slipped, said shit, went hip-down and sideways, lost his glue all over the floor, got a mop and wheelie-bucket, pushed it to the janitor’s sink, put the water on full, stuck the dry mop in, ran to get rags, the sink overflowed, he said shit again, it went down the drain from there

81

(1992)

The Old Men

Please allow yet one more banging of the table in honor of old men: nothing much more beautiful than Frank along the shoulder of 14, in gravel, bottle caps, cigarette butts, from the nursing home on a new warm day to step between air rushes of cars to the other side, the cool cement floor and breeze blowing through the northsouth doors of the produce stand. Or Charlie, from his farmhouse by the shopping center, to push-broom cornsilk into a moist pile, lean on the handle. I visit you often, Frank, Charlie, in these places I leave to, harder each day to find you. Your house is closed, Charlie, wooden slats over the porch windows, and a man hung himself in the basement, left his essence flickering down there and over your untilled land.

Behind a cinderblock wall, shielded from customers, the worn wooden cashbox: I see my hands there with bills, counting, and you angling there,

82

Frank, your head turned down, chin on lapel, a dried, worn face the same every time, a scowl, a smile. Then, watching the action— muskmelons and white corn are in. You don’t know my name, some new kid late in your life here. From here to the supermarket drugstore and back to here, packages of pipe tobacco, cigars— Joe? Joe?

Everyone’s Joe. Frank is Joe. That’s the Hardy Boys, y’know? Who are they? A little man rocking on his feet, doing a little dance, white hair short to a fuzzed scalp, then in the soft squeeze of a play headlock, in the arms of big, thick Stein, you rap your pipe on his skull, what kinda stuff you smoke in that, Frank? Your grumpy muttering— you knew what you were saying, sounded good to me. Stein did some time, I heard, and time does me, the orange fire drops behind the pipe-legged Palatine water tower, pale green blimp gone black over greenhouses, creek, creek-loving line of trees,

83

a field for sale with a number to call, a realtor on the school board, highway frontage, will build to suit. You stand with me here, old men, as time does me, in the gravel parking lot, downhill from the stand, uphill from the creek, the marsh, evening trilling of redwings. I dance, old men, in a circle, arms out and loose, one leg up, bending at the knee, calf rising behind, then the other, a huge slow shorebird flapping wings here in life, beating the air, stomping the ground in the dusty flat,

I am here, I am here and if I do this long enough, beat it in, work it in, I may then be.

(1992)

84

The Right One

She nags him— put your hat on— go back to the car and get your hat— then turns to me among the trees—

he used to be a big man had most of his stomach removed if he gets a cold it could kill him and I don’t know it could be our last Christmas together I just want to get the right one

puffing and red, baseball-capped, his jacket a mattress, he returns, at every stake his wife asking sharply whaddya think of this one?

More than once, my gloves deep in the boughs of a balsam, knife at the twine, about to cut through, but they change their mind, I wave my arms, talk and sell—

No Canadian balsam this year, nope, a few Douglas fir over there, though. The Scotch are from Michigan and Wisconsin, white and balsam are from Wisconsin, too, Fraziers are from

85

the Carolinas. They’re real nice this year, nice and full, real nice, hold their needles real well, of course you’re always going to lose a few, no they don’t spray ‘em with anything but they shear ‘em in the field to get the Christmas tree shape.

Breath flashing out, heads turning, eyes darting, theirs to mine, to a tree, a Scotch, a white pine. In the raw wind, they walk away, they go see, they cover the lot slowly in the snow, up and down the rows, checking for gaps, holes, thickness of the trunk, no curves, will it fit in the stand, as though this was the way every year, respecting the task, themselves, each other.

I’m not going in to get warm.

I stamp the needle-covered ground, the icy mud and gravel, frayed pieces of old rope. I swing my arms, tighten my hood, wipe my eyes,

86

watch the whipping lines of light bulbs and the clock at the bank across the street, and drift, remembering the summers working here, how after 3:30 time passes more quickly, you wind down, sweep up, a broom against carrot fronds, limp in the dust, scrape of a dustpan. Then six o’clock, all of us at the awning ropes, eager to go home, shutting out the last cars, Bob holding out sweet corn through a gap in the canvas to some Mexican men, his son at the last rope, ready to bring it down—

the knife slits through, the tree tips over, I grip the trunk, lift and grunt to their quick words about the warming house, and through the forest, they’re gone.

It’s a small balsam for their last one together, thirty-four dollars. I thank them now, tie it down, wave them on. Bundled up, buckled in, they drive away, smiling and talking together, making vapor in the car.

87

(1992)

Independence Day

A simple cart at the corner, a metal tank on four wheels in the full sun, bottles in icy water under lift-open doors, near the Fourth of July fair. You have seen children doing this. Some hunch toward truth has brought me here, with vendor’s license, hand-painted signs, to wheel this cart, sell sixteen flavors of soda. I wish for the heavy vendor’s truthful bellow, the truth of this cart, the truth of this work, of these thick glass bottles, their stunningness in sunlight, their liquid colors, their sun-sparked colored crowns.

I am third behind the summer’s top freaks: a raspberry-faced woman, thighs overspilling a pink Stingray bike, knees banging the bars, spends all night on a tennis-court bench, and a guy they call her husband, careening around downtown, waving from a circus seat, highest-riding bicycle on these streets, paper crown tilted, two handlebar pinwheels spinning in his face. He slides around the corner now, big grin and waving hand, there’s the pop guy, yeah, yeah, yeah.

A sweating heavy umpire, blue uniform and hand full of mask, fishes for change

88

in a jangling pocket, chirps peach through his tombstone teeth, the pioneer graveyard of his mouth. A worn bill, a dripping bottle, a damp quarter, we have something of each other. The next in line orders lime. Motions repeat. Explain flavors, listen for choice, lift bottle out of icy water, take money, put money in pocket, open bottle on bottle opener, hand bottle, give change.

The bright heat of day gone to colored carnival lights in darkness, we settle down, her bike thrown behind bushes, the king off his throne, clowning, acting a robot, a doll’s pursed mouth and eyes, children jeering from the grass. Behind my cart, I grow tall as The Zipper before me, the vertical focus of this closed-off street. My eyes flash, blinking light bulbs, my bright signs join me to the world. The ride’s lights swell outward, shrink inward in bright lines, zippers themselves. The ride jerks and clanks, children scream, cages swing, the frame tips, they descend one side and ascend the other, whip over wildly and rock, catch breath and stomach below

89

together. Cages flip, coins and pens fly out, the ride circles some more, then stop, bounce, jerk, unlatch, giddy kids unloaded and running, new ones bolted in. In a car of my own, I ascend and descend.

Late the next afternoon, burnt and dry. I pull the cork, meltwater spatters out the petcock. No, sharply turning woman, I am not peeing on the sidewalk. I push the cart home to the heartbreak of Sunday evening, of hopes shrinking to dinner, the trash to the street, the weak pleasure of a finished week, our time and our selves consumed. My children gather, hang on me, sit on my knees this afternoon, the only security I provide, and I feel their warmth, the power in their legs, as I melt into this evening, surely less now than ever, my axle wobbling, my orbit wandering. I’m nuts. All that works is truth, the complex simplicity of pure carbon diamond, the honest mess of coal’s dried-up old soup. When that is all that works, next to nothing works. And most of what I do is all anyone does: read the newspaper, drink coffee, have some hunch about truth and not heed it, throw it away with breakfast, turn to what works because of its closeness: safe work, gardening, lawn cutting, sports viewing, light carpentry, care of children, cooking on the grill, bills, talks with neighbors, gatherings at the curb around the garbage.

90

About 7:30 pm July fourth, they began to take the park. Strollers, wagons of children, their swollen parents, grandparents edging along with lawn chairs, teenagers slouched, slumming, pierced, multicolored, wearing sports caps, lipping cigarettes. Large brown-skinned families dressed up, black and red, young girls pushed up and pushed out, moving in rhythm of growth, the boys loose and glowing. Blankets rippling over grass, a massive encampment, the outside now an inside, the orders doubling, tripling, two strawberry one cherry two cherry cola one lemon three lime, some served warm. Leaving the line, they hold the bottles up before the diminishing sun, bathe their eyes in color, put crown tops to lips, bend back, drink deeply, return smacking, shaking their heads, looking at me, where do you get this stuff? I talk, I stand and bend, I talk, I stand and bend, crack of my ass to them all like never before, dipping for cherry, lemon-lime, black cherry, orange, ginger ale, grape, root beer, raspberry, in the whirling— carnival rides spinning, lights flashing, children screaming, ice cream trucks chiming, distant musics bursting crazily over all, throbbing under all, blurred bills shoved damp into my pockets, change also given damp, the cooler doors slamming and slamming, then, the sky flashing, silent lightning shifting around, gold behind the gray lens of the sky, and thunder murmuring low with the flickering, close strands of clouds passing swiftly over

91

up-turned heads, then splattering rain, cold, thick drops raising street dust and steam, parents calling for children, scattering all ways for cars, eaves, porches, shelter, blankets abandoned and chairs tipped over, and I continue to sell, rain and sweat in my eyes, the cooler lid lifting and dropping, bills soaking, crumpling, some down in the dirt, flavors running out, empties returning.

I pant in the van, lay with the bottles, crates, ice, coolers, the truth of this: simple goods, small amounts of money, dirty sweaty pants half down my hips. To dip down to the icy water, bring up the cool juice, give it to someone, sit later, write this down, give it away again.

Thank you, ice cream truck drivers for fighting it out next to each other on the curb, one putting up a cardboard sign, “lowest prices,” and thank you especially younger driver who traded me a snow cone for a soda, young man in baseball cap, shorts, sandals, who did it so naturally and said it so clearly, I don’t care if he gets mad, when I asked him about his sign and the other driver.

(1997)

92

The Capodimonte Crown

that woman I would not bargain with at a garage sale, over a capodimonte crown she badly wanted, who finally agreed to my price, ten dollars, and left me to later confront the space where another item had been ripped down from display, a child’s Disneyland apron stolen in rage while I packed her crown in a box—she would get what she wanted, at any cost, though what she wanted was nothing, and I wanted and had nothing, too, licking my lips, shuffling the bills, selling things that had passed into my hands from other hands, my family’s, and into hers

(2022)

93

Americans at the Poles

1: A Trader’s Mission

My cousin has been up here in the high Arctic since the 1920s. We visit him in his shed. It’s a trader’s mission! He goes out to talk with my wife, and I begin moving the stuff on his shelves around, filling bags with bottlecaps— Orange Crush from the 1920s, Jumbo Grape, Cherry Crush—

I pick them from the dirt floor, below his shelves, from behind boxes, keep loading bags. These I will keep, these I will trade, these I will sell. And old cans, soda and beer, some newer, crumpled, of aluminum—

I fill a paper grocery bag. These were in the high Arctic! Here’s more caps down by the crack, where the wall meets the ground, with rust

94

covering most of the writing—

I keep them anyway. These must have been from General Hazen! My cousin comes back, sees me shifting stuff and loading, and I promise him, as I begin pushing the bags together on the floor, that I will bring him more when I come back next time.

2. Convincing Richard Byrd to Leave the Outpost

We’ve been here for days, trying to make him go, enduring his stony antics—his uneven breathing, blank wandering outside, face a pale mask of sores, eyes sunken, old furry gloves slopping together. Finally, I hit on it. We follow him in a circle around the shed, on his walk. Look, Dick, let’s just leave the stuff here and take back what’s important. Let’s just leave the rest and get out of here. He stops, gazes severely, falls to the ground on his stomach, raises himself on his elbows, looks over. Dick, look, I’m just trying to be as real as possible

95

with you. He looks at my partner, then me, and we nod, confirming this. I keep going—Think about it. When this ice starts moving or breaking up, and this stuff drifts, and people find it thousands of miles from here, think of it! You’ll be famous! You’ll be like Amundsen, Nansen, Frobisher! This causes him to think, and roll onto his back, still propped on his elbows. Yeah, and when people come here, Dick, to this site, think of it! They’ll find your stuff!

3.

They’ve opened the only Antarctic volcano to tourists. The plowing of the paved road ends at a service road intersection. In our ’81 Continental, we keep moving through. Others have gone before, and one lane of the pavement is clear. We want some frozen magma. Up a slight rise, a hill of snow by the road is striped black. We crumble black

96

Franklin’s Snow Shovel

chunks of rock out of the snow. I pile a few of them, some still with snow, onto the carpeted floor of the Lincoln. My wife discourages me: Honey, you’re taking too many! It’s ok, just a couple more. One of my daughters complains. My wife backs us down the curve, to the plowed road, where we stop, idling, looking at a guy in a blue parka shoveling snow at a roadside map and rest area. The pan of the old shovel is made of a rusted wire mesh, with a thick wooden handle. Confusing explorers, I dash out, leaving the door open, shouting, Hey! That’s got to be Franklin’s snow shovel! Other tourists in ski suits hear me, walk over to confirm it. The man stops his work, stands with the shovel, looks at us.

97

How Much Longer Manhattan Island

How much longer the young woman reading Hebrew to herself on the subway from Brooklyn, her lips moving, how much longer? How much longer the still red-haired grandfather hugging, kissing, tickling his red-haired grandchildren all the way from Flatbush to Manhattan, how much longer? How much longer the coolers full of plastic bottles of water dragged up the Brooklyn Bridge promenade, swirling baths of ice and water, how much longer, how much longer? How much longer the evening density of taxis, the dinner crowds, the broadshouldered young white tourists in backpacks and shorts converging on Greenwich Village to drink, how much longer? How much longer the drive to be there, to be here, to rent, to chase, to live, to document, how much longer, how much longer? How much longer the great hole in the ground at Church and Courtlandt where two solemn streams pass, tourists gazing inward, others facing outward, doing business, heading for the new subway trains down in the hole, how much longer, how much longer? How much longer the trash cans filled with empty Poland Spring water bottles, the sidewalk carts filled with bagels and Gatorade, the window air conditioners hanging from the sides of buildings, the unsteady fire escapes straight up, how much longer the men smoothing new concrete in 100-degree humidity for the path of the concerned, the driven, in Columbia University, how much longer the girl

98

sunbathing in a burgundy bikini in a rectangle of grass, how much longer her smooth skin bared, how much longer the electronic passage of millions down filthy sweaty stairwells, walkways, plazas, down one level, down another, and another, then journeying on noise, and up, out, holding the guardrail, under the low ceiling of the longest, steepest escalator of the twenty-first century, to dodge hundreds more in the space of ten seconds in low-ceilinged mid-level plazas of aluminum and concrete? How much longer the journey, the grime, the steps, how much longer, how much longer the maps, the machines, how much longer with no place to sit, no place to piss, the millions on the march holding things in, how much longer the miles of pipe and wire, the ganglions and aneurysms behind plastics and drywall, under hardwood and tile, how much longer, how much longer? How much longer the handbags, the hospitals, the fabrics, the plastics, the compounds and fluids, the metals and blood, the cemeteries, the fuels? How much longer the recycled dramas, shows, music, dancing, how much longer the money, how much longer? How much longer the fixed points of reference, twentiethcentury touchstones, this culture, how much longer?

(2006)

99

101

On the Inside for James Anzell

You told me you thought I was there, the auto parts store in Palatine, where your uncle brought you years before, maybe for the four-door Ford Taurus you drove last week from Uptown to a commuter parking lot, Arlington Park, where you got down to the worms burning alive on the platform asphalt and coaxed them, edged them, moved them to the grass, when placid afternoon commuters and uniforms surrounded you. I want to leave, you declared in therapy, removing your hospital socks, placing them in a neat pair on the tile, gently stamping them with your feet, affirming your desire to the group. In your stuttering monologue to yourself, you project the recitation of your brain— Genesis Book 1, to not eat animals, eat only the tree food—in your eyes a wide, worn brownness, on your skin the wear of hard years, your balding

102

graying head of wild curling hair a monk’s cap, and in your face, an old friend, Billy Jones, childhood classmate of softness, baseball, kindness. The fragments of your speech sort into coordinates, a bare coherence— lived and worked in Lisle town, at a sheet metal stamping plant on Ogden, your apartment near Rohlwing Road and Maple Avenue—living now at Kenmore and Granville, Uptown Chicago, a shelter or apartment, I can’t tell, and the question’s ignored, but you think you met me before, I’m just like a guy named Reedy, maybe the last friend you had, the last one who asked questions and tried to listen, bring your mind to something here, outside the rhythm of thought inside, outside your electrified spirit, raw, invaded, steady voltage telegraphing the same message, a repeating circuit, eat the tree food, not the animals. Like a murmuring priest, you recount your family tree, the Stawinskis, Bacinos, Purdys, an uncle named Seith, men married to sister mothers, one named Gladys,

103

no, Alice, a brother named Louis, greatgrandparents named Santa Claus and Claussie, where the line always reaches in the three times you have told me the story, a fitting place for it to end, can’t tell if you’ve imagined this childhood legend as your supreme ancestor, creator, or if maybe Claussie was a nickname, and by extension, the old man became what he did. You seem to remember your birth, in 1954, when many, many babies appeared in your sister-mother’s arms, or maybe your consummation, as the male night nurse openly and frankly reveals your birth year, 1955. Whoever your mother and father were, they created a man who first read the Bible in 1987, 32 years old, now 62, didn’t want to come here, wants to leave, but here again, anyway, trapped, caught bent over rescuing dying worms at a railway station on a warm spring day, a sensitive man who says simply on another day in group I hope I will do good.

104

(2017)

The Northern Lights

after a decade, a decade and a half, intersections here have new traffic signals, patterns, pavement, clusters of services, gas, drink, food, what is all this shit runs through my mind, might have spoken it to myself out loud, alone and chasing a rumor here, the Northern Lights, at a dirt dead-end, Racine County, the bright full moon risen large through elongated swirls of clouds, and the planes are slowing, lowering into Milwaukee, into the spirals and slight glow, the city horizon— an ambulance passing on a distant road, siren stirring coyotes and dogs, red light a flashing jewel above the massed plants of the field—blooms of Queen Anne’s lace cupping, curling, the first cold night, September—and at the Iron Skillet truck stop, the moon huge over the southwest corner of the building, a lit dead rock in the dark out there, anchoring the slippery contents of our lives, the miracle, what spreads and lives, the divinity here on Earth—and inside

105

the truck stop, more certainties staying true—chairs upturned on tables, a carpet sweeper, the warm home of the cook and late-night waitress— at the end of the road, I tried to see what I came to see, the colors I saw once moving and swirling one cold night thirty years before, burgundy, red, dark green, but retrieve here instead something forgotten, what my mother told me I was seeing beyond the high pine trees of the back yard, faint trails of white light in the dark sky, there’s the Northern Lights, she said, as I looked out the kitchen door at what might or might not have been something matching the rumor that had traveled through school, that day, and I believed her, took it on faith that they were, because I could believe anything she told me, and everyone could believe anything she told them, the most rational, honest person I’ve ever known

106

(2017)

Lunar Eclipse 2008

the cold of this day in February Chicago 2008 has set things— no wind to stir the layer of fine snow over the frozen ground, the smooth expanses from porch to dark street— everyone’s inside—

the full moon glows orange in total eclipse, a star and a planet angled to either side, another star below, like a tail— kite-shaped, it seems to hover over all, foreboding, a sign of flight, a sign of what, a sign of nothing—

107

what to make of alignment, position, symmetry, when it is unintentional and large, beyond what hands and minds can do— I have run up and down the stairs twice to look at it, pulled the living-room shade way up, the panes edged with frost, the light wobbling through the imperfect glass—the first time, tried to photograph it—useless— the second time, a black shadow ebbing to a dark, soft cap over the bright moon face, I tried to look at it, and look at nothing—and look at it all—the small, thin white pine down the slope of lawn, frozen in a foot of snow, still—the wavy bands of light and dark on

108

the snow—the lit windows of a few homes—the tiny bright dot of a lighted doorbell across the street, a pinpoint strong as the moonlight, now nearly full— my bed rotates with the Earth, between the sun and the moon— so small, I am, at my living-room window, a stick figure in a square— raising the shade for a few minutes, gazing, lowering the shade, then doing it again—in a darkened house, casting no shadow— I have no depth— what I think and what I know does not depart much from the visual, the simple—it was shaped like a kite, or a ship, somehow foreboding, over a dark, cold night, here, at this place on Earth, marking it—

109

or it was warm, like a woman, somehow, the gold moon a beginning, a glowing child in the womb, the light forming at the center, Saturn and a bright star angling out her hip points, the lines dropping sharply to the lower star, the vulva— foretelling conception, a birth—

this human, at 46 years, at the window between the sun and the moon— between my beginning and end— alignments of birth and death, and a moonchild forming in the sky—

and I think of the woman I love, who would gaze quietly with me, who would talk softly, talk less, raise the shade perhaps once, look longer, lower it much later, say less of all of this—

110

I live in simple humanity— birth, death, love, life, appearance, disappearance (2008)

111

Another Lunar Eclipse

for Patrick and Michael Plumb

He’s 58 years old, in a nursing home on the east coast somewhere, seems to have had an accident, posting messages from his bed, from the box he cannot escape, about his love for dogs, his mother’s cooking, his grandmother’s candy dishes, pot roast recipes, other food he misses, his roommate shitting himself at night, and this morning, four o’clock, don’t miss the eclipse tonight. Out a front window, can’t find it, out the back, there it is, blurred through the glass of two doors, then just through one, it’s in focus, round, dark orange, nearly black in the lower left corner. I shut the door on it, empty dishes from the sink, throw receipts and papers away, hang clothes, clear the table, wipe the table, stop, open the door again, put my face up to the glass and breathe, see it there, the dark orange moon straight out my back door, about 35 degrees above

112

horizon, dark, quiet, cold outside, and it’s a gift to stand here nearly naked at the cool glass. He says from his bed, his box, if I ever get out of here, writes about Jesus, his savior, and then the tooth he pulled from his own mouth, his past sobriety, ninety pounds lighter now, or then, I can’t tell when, calls himself the fat man, blesses me and my family, now and forever. What happened, I’m afraid to ask, have not spoken in 35 years, last time, the death of his mom, and his brother Pat so drunk there, blasting fumes, loud, shushed by his daughter. His brother is dead now, too, and Mike wants to get the hell out of one bed, one box, and into another, and I am in this box, my house, staring dumbly at the moon, lit, orange, and dead out there, part of my short forever, part of our human forever. I think of the movement of the Earth later that day in a parking lot and the eclipse again this evening 36 hours later in another box,

113

my car, as the moon “rises” again in the east, low, large, pinkishorange, my mind tethering one surface to another, registering the visible facts of motion and light, here in this box knowing next to nothing of anything, of gravity, tides, physics, hydrogen, helium, space, light rays, the moon’s geography, the names given to craters, even, or what happened to Mike. Don’t miss the eclipse, he said, to anyone who might read or listen, and I didn’t, opened the door shut the door multiple times to look out from the box, my house, a human being feeling himself acutely in body and home, his perception the center of his universe, aware and not of the motion that moves him on his clay pedestal, puts him in position, sometimes, to be part of what blocks the sun, bodily casting a shadow of his physical existence in time.

114

(2023)

First Covid-19 Vaccination, April 2021

thanks, Morlan, she said, to the serviceman who collected the facts of my being, then with her slim height looked straight, hard, and steady into my eyes from under her camouflage cap and above her mask, one or two seconds of wide unflinching gaze, checking, registering something, whatever it is in me that was not gathered at the other stations

115

(2021)

A Mundane Dream of What Humans Became

Inside a standard circular spaceship, typical ceiling height, a round column down the middle of the interior, carpeted, with windows, about a dozen people on board, of different ages, my grandson transmitting at a computer screen, people on board occasionally dying— an old man drops through an ejection gate in the floor—a teenaged boy seems to know most about how to run things, finds a power pack along the wall, installs it into the ship circuitry. People on board realize the ship is changing direction, and a guy in his fifties, older hip dude, mostly bald, starts to slip away from life in his chair. Then, we realize the ship is descending, returning home to Earth, finally, and upon landing, a small door opens, and some current people of Earth enter, barely recognizable as humans. They have heads, faces, upper half-bodies, but plastic attachments below, no legs or arms, and there seems to be a recording coming from a grill on one’s robotic face—an account of what might have happened, or what humans became. What they had been is gone, and these are what is left—broken, repaired, unreal.

116

(2022)

Investment

I drove here without excitement, but with a plan—lunch and a hike on a railway, Barrington, early spring, a section of the EJ&E west of town curving south—but it’s too cold, didn’t wear enough, and I’m unsure where to park, scuffle down through the bare brush. Commercial real estate here sits empty, security cameras on it, warning signs, not sure who owns the old Pepsico headquarters now, but people with investment are waiting. The railroad tracks are out there, back of the closed truckyard, and further south, large colonial-style houses befitting this town, nice lots backing to the tracks, a cul-de-sac hanging over the slope. Alongside the edge of the cemetery, clay fill, gravel have been dumped, making more space, correcting the pitch, the drainage—new narrow roadways have been cleared, three new tiers of grave space, no stones, no markers,

117

plots maybe sold, more people waiting, preparing—the land is full of investment. I check the embankment, steeply downhill, if there’s barbed wire, the density of branches, and I hear myself say out loud, the first surprise of the day, there’s a trail down there, a line of bare dirt to the left, to the right, along the tracks, but I can’t park here, leave a lone truck at the edge of the cemetery, and I decide, I don’t want to do this, anyway.

(2023)

118

Café Fourteen

If this is the last time I will be in this restaurant, I have to admit it, I am still here in midwestern suburban America, where I was born, lived, never left, and somehow died— and Sister Golden Hair still plays throughout the place, ugh, God, closing down my line of days, years, hours I seldom thought about as I lived them, the waiters and cooks speaking Spanish through the kitchen window, a language I have never learned, how lazy I’ve been these last years of my life, eating in restaurants like this, booths, soups, salads, dressings, entrees, iced tea, coffee, water refilled here by Manny recently promoted to waiter to work alongside Adrian, they know me here, a weekly visitor, like John knew me, greeted me and others by name, shaking hands, a firm squeeze for the triceps, a pat on the back, how you doing, young man. He’s gone, left in the numb haze of the thousand or two thousand calendar days’ passing across the past five years or so,

119

on the number line, something running across school blackboards during the previous century in towns like this, where people like me from suburban families were awakened, fed, clothed, sent to school, grew taller, heavier, marked and measured by their doctors, gym instructors, humans growing moreso daily, with just a little more food, more vitamins, more hormones, a little more of everything each day, growing invisible. A lot of people pronounce bruscetta wrong, they say bruschetta, it’s brusketta— the waitress Jeannie here, retired high school teacher, her husband now gone for years—and Adrian standing at a table’s edge, politely listing the beverages, no, we don’t have the root beer, but he’ll check on the flavors of Jarritos. This last time here, I can finally see, and breathe. The weight is lifted, people and places are finally visible, the stink of fish from the kitchen drawn in not

120