PESTICIDE NEWS

An international perspective on the health & environmental effects of pesticides

Can UK food safety regulaters be trusted?

Investors must engage with the pesticide industry

Insecticide safety tests are failing bees

An international perspective on the health & environmental effects of pesticides

Can UK food safety regulaters be trusted?

Investors must engage with the pesticide industry

Insecticide safety tests are failing bees

By Professor Erik Millstone, University of Sussex

By Professor Erik Millstone, University of Sussex

The safety of the UK’s food supply is as important to UK citizens as availability and affordability. But we can only be confident that our food is safe if we are able to trust that farmers, food processers and traders follow the rules set by regulators. Ultimately, we need to be able to trust that regulators prioritise the protection of public and environmental health over commercial interests and that the regulators’ rules are effectively enforced.

In July 2022 YouGov published a report titled the UK’s Trust in Food Index: a report on the nation’s trust in the food it consumes. It concluded that: “Overall, trust in UK institutions has gone down in the past year. Trust in food has seen the second greatest drop of eight per cent, with only gas and electricity supplies losing more trust.”

The UK has left the EU and is no longer reliant on the European Food Safety Authority and regulations set by the European Commission. The responsibilities of the UK’s advisory and decision-making system are far greater and more important than they were pre-Brexit. Motivated by our long-standing concern with food safety in the UK, Prof Tim Lang and I recently focussed on the issue of how far UK food safety regulators can be trusted.

We scrutinised the published declarations of conflicts of interest provided by many of the main actors in the UK food safety decision-making system. A rule in the UK requires all agricultural and food safety expert advisors, as well as the members of Food Standards Agency’s Board, to provide declarations of ‘conflicts of interests’ (CoIs). These are published on their institutions’ websites. We not only gathered up-to-date figures, we also tracked developments over time. Our findings were published in Nature Food

What are conflicts of interest? Conflicts of interest arise whenever individuals are in a position to prioritise their personal interests, including their financial interests, over their responsibilities to their employers, or to the organization with which they work. Such conflicts of interest seriously threaten standards of public and environmental health because they can transform organisations that were set up to protect the public interest to become subordinated to commercial interests, and succumb to what is called ‘regulatory capture’.

Right to science in the context of toxic substances, a recent report to the UN General Assembly from the UN Human Rights Council, said: “In order for the science that forms the basis of policy to be trusted, conflicts should be avoided rather than simply managed through disclosure processes.” The UN HCR’s recommendation was eminently sensible. Requiring that CoIs are declared is not sufficient to ensure that those conflicting interests cease to influence the judgements of the individuals and the bodies of which they are members. CoIs can and should be avoided.

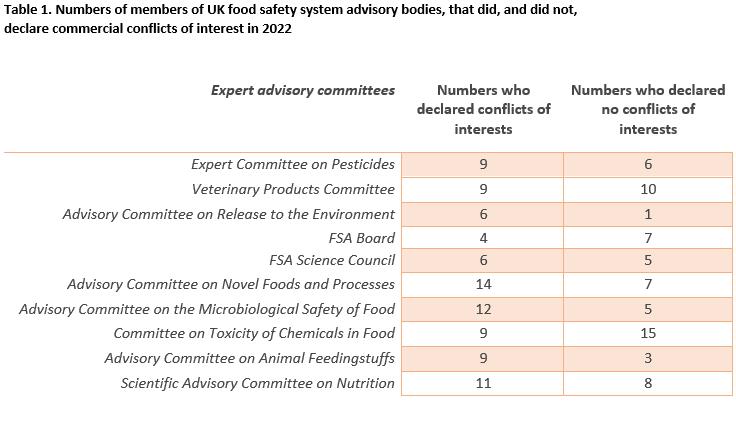

We only counted those CoIs that were explicitly included in the officially published list of declarations. We know of several other CoIs that had not been declared, some because the rules are not sufficiently tight, but also some declarations have been incomplete. We looked at nine expert committees that advise the Department for the Environment Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Food Standards Agency (FSA), as well as the FSA’s Board. All of those bodies and their members have key roles in deciding 1) which food and agricultural products and processes can lawfully be used and sold in the UK, 2) which are restricted and how, and 3) what is prohibited.

All the committees have, and historically had, members who have declared CoIs. Two of the three committees that report to DEFRA have majorities declaring CoIs. The Expert Committee on Pesticides consists of sixteen members, ten of whom declared CoIs while six did not.

Those ten declared CoIs with a total of nine industrial companies. The Advisory Committee on Releases to the Environment, which advises on GM crops, includes six declaring CoIs, and just one who did not. One of the six has declared commercial links to seven companies. The six collectively have commercial links with a total of sixteen companies.

The proportion of FSA Board members declaring conflicts of interests peaked in 2008, but subsequently declined. In 2022, three out of nine declared CoIs. Of the FSA’s five topic-focussed committees, all have had majorities of people declaring CoIs at some stages. These findings provide sound reasons for being sceptical about the trustworthiness of the UK’s

agricultural and food safety regulatory system. All of the components making up the regulatory system include people who are not solely focussed on the protection of public and environmental health. They have commercial interests in the economic well-being of the companies whose products they judge.

Erik Millstone is an Emeritus Professor of Science Policy at the University of Sussex. He has been researching the causes and consequences of innovation and technological change in the agricultural and food sectors since the mid-1970s. He has also analysed the structures and operations of the institutions responsible for setting agricultural and food policies, including safety standards. Access 'An approach to conflicts of interest in UK food regulatory systems' in Nature Food

In a first-of-its kind study, researchers found children exposed to the controversial herbicide were more likely in early adulthood to have a collection of symptoms that increase risk of heart disease, diabetes and stroke.

Over the last decade, Dr. Charles Limbach noticed something strange in his family medicine practice in East Salinas, California. Kids between 5 and 15 years old showed elevated levels of liver enzymes, a sign of liver inflammation.

Limbach ordered a panel of medical tests on each patient and repeatedly saw the same result: fatty liver disease.

“When I trained in family medicine here in Salinas about 30 years ago, fatty liver was never even mentioned,” Limbach told Environmental Health News (EHN). Now, a hundred kids in his practice have fatty liver disease, characterized by excess fat stored in the liver, which can lead to long-term liver damage.

Limbach read research led by Paul Mills, family medicine and public health professor at UC San Diego. Mills' study showed a link between fatty liver disease in adults and exposure to glyphosate, the world’s most commonly used herbicide, and the active ingredient in Roundup. “This bell rang in my head,” Limbach said, noting that many of the kids in his practice ate cereal products from crops treated with glyphosate.

Fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome, a collection of symptoms that increase risk of heart disease, diabetes and stroke, are rising among children and young adults in the U.S., and new research published in Environmental Health Perspectives helps explain why. Spurred by Limbach’s observations, researchers at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health found that childhood exposure to glyphosate is linked to liver inflammation and metabolic syndrome in early adulthood. These conditions can lead to liver cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Glyphosate has also been linked to cancer. Bayer (the company that acquired Roundup's manufacturer, Monsanto, in 2018) is embroiled in hundreds of thousands of cancer-related lawsuits. Glyphosate use in the U.S. has skyrocketed in the last two decades, so while the study population lives in Salinas, California, an agricultural community, the findings have national implications.

Lead author Brenda Eskenazi, director of UC Berkeley’s Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health, and her team used data from a study Eskenazi initiated two decades prior. From 2000 to 2002, the researchers enrolled pregnant women and babies born in the Salinas Valley, nicknamed “America’s salad bowl” and producing nearly half the country’s lettuce. From birth to age 18, Eskenazi’s team collected hundreds of thousands of biological samples, health records and glyphosate exposure data from 480 mother-child pairs.

In their newly published study, the researchers analyzed urine samples from the pregnant mothers and their children at ages 5, 14 and 18. High concentrations of glyphosate and AMPA, a derivative of glyphosate, in children’s urine was linked to liver inflammation and metabolic syndrome at age 18. The researchers observed this association independent of body size, even though the study participants were more likely to have high body mass indices.

Robin Mesnage, molecular biologist at King’s College London, told EHN that “the impact of glyphosate on mitochondria causes an oxidative stress,” an imbalance of reactive oxygen-containing molecules, “which can have downstream effects on many tissues.”

Furthermore, Eskenazi’s team found that childhood proximity to glyphosate use predicted metabolic syndrome at age 18. Since 1990, California has required full, detailed disclosure of all pesticide use. Eskenazi’s team used those data to estimate the amount of glyphosate applied within one kilometer of each study participant’s home, from birth to age 5.

Glyphosate use near participants’ homes was low during their early childhood, but higher when they reached ages 14 and 18. Indeed, during this time, as crops genetically engineered to tolerate herbicides came on the market, glyphosate use skyrocketed across the country. From 1995 to 2014, annual agricultural use of glyphosate in the U.S. increased from 27 million pounds to a peak of nearly 250 million, according to Charles Benbrook, executive director of the Heartland Health Research Alliance.

But risk of glyphosate exposure is significant even in urban areas, and crops treated with glyphosate are distributed throughout the country. “Eighty percent of the typical dietary exposure to members of the public in the U.S. that aren't handling or spraying a glyphosate-based herbicide come from wheat, oats, barley and edible beans,” Benbrook told EHN. These findings are relevant for children everywhere; the levels of glyphosate and AMPA among the Salinas community are within the range reported for the general U.S. population, Eskenazi said.

Glyphosate may be necessary for some agricultural applications, but “it's not essential for lawns and golf courses,” Eskenazi said. The Environmental Protection Agency reports that glyphosate poses no human health hazard, and Roundup and other glyphosate-containing herbicides are available over the counter. But Eskenazi advocates for limiting glyphosate use until we know more. It will also be important to regulate use of paraquat, another dangerous herbicide linked to Parkinson’s disease, so that paraquat is not simply swapped for glyphosate, Benbrook told EHN.

Scant research explores glyphosate effects in humans, especially among vulnerable groups like children. Eskenazi and her team have plans for deeper investigation. Since 2000, Ezkenazi has been collecting health data on neurodevelopment, respiratory disease, hormones and puberty, among other metrics in the Salinas population. “We need to follow up with the whole cohort and see what associations we see not only with metabolic disease but other health outcomes as well,” Eskenazi said.

Find the original article written by Kate Raphael, publishd in Environmental Health News here. Find the study by Eskenazi et al . published in March 2023 in Environmental Health Perspectives here

Mainstream agricultural systems are now almost completely dependent on the use of pesticides and many farmers have abandoned several equally effective, non-chemical weed management methods. Herbicides, particularly glyphosate products, are applied every day to fields and their surroundings, putting human health at risk and negatively impacting biological processes and ecosystem functioning.

Herbicides have a wide range of non-target impacts including direct toxic effects on soil organisms and many invertebrates and vertebrates, but also reducing weeds removes vitally important food and ecological resources from farmland ecosystems. The 2017 United Nations (UN) report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food also highlights the adverse impacts of pesticide use on human rights and human health (workers, their families, bystanders, residents, and consumers) and reveals that intensive agriculture based on pesticide use has not contributed to reducing world hunger. Not only do herbicides have many negative impacts, they are also increasingly failing to work due to evolved weed resistance.

Herbicides are used in agriculture and horticulture to combat weeds that, above certain thresholds, compete with crops and pasture for nutrients, water and sunlight. There is also widespread use in no-till and reduced tillage systems where herbicides, principally those based on glyphosate, are used to kill all vegetation postharvest and before crop establishment. Thirdly, they are used to ripen and desiccate grain and seed crops before harvest.

Non-agricultural uses include the management of public areas, for aesthetics or reducing hazards (e.g., sidewalks, pavements, and railways), or for weed control in private gardens.

The new report Weed Management: Alternatives to the use of glyphosate produced by Pesticide Action Network Europe outlines the wide range of nonchemical alternatives to herbicides that are already available and used by organic farmers and those practising integrated weed management (IWM). It highlights the critical need for mainstream farmers and growers to make much wider use of these tools, and the need to expand and improve current nonchemical tools, while also developing novel approaches.

Using glyphosatebased herbicides as a reference, the guide presents a wide variety of weed management approaches that achieve highly effective weed control without the use of herbicides.

Paraquat has been responsible for thousands of deaths annually and is banned in over 67 countries. New research, led by Pesticide Action Network UK (PAN UK) debunks the myth that paraquat is needed for agricultural productivity and food security, with scientists urging the listing of paraquat under the UN Rotterdam Convention.

The study, published in Environmental Science and Pollution Research, compared United Nations crop production data covering six to eight years prior to, and following, paraquat bans in eleven countries. In nine of the countries, researchers identified no observable decline in aggregated crop yields or key individual crop yields following paraquat bans, and found yields increased in several countries. Combined with complementary literature reviews and consultations with voluntary industry sustainability standards, retailers and regulators, the study indicates that eliminating paraquat will save lives without reducing agricultural productivity or food security.

The research casts doubt on the justifications put forward by countries that have blocked the global community’s ability to better control imports of the pesticide under international law.

In June 2022, India, Argentina, Paraguay, Guatemala and Indonesia cited paraquat’s perceived importance to food security when opposing the chemical’s inclusion in Annex III of the UN’s Rotterdam Convention, preventing use of the agreement’s Prior Informed Consent Procedure, which helps countries to control imports of paraquat.

The research also found that integrated weed management techniques not involving paraquat are instrumental in ensuring strong yields in post-paraquat agricultural systems, including those used by over 1.25 million farmers working to voluntary sustainability standards that exclude use of paraquat.

Dr Sheila Willis, PAN UK, says: “Misconceptions and false narratives have prevented stronger regulation of one of the most harmful pesticides in international trade. Debunking the myths should help ensure paraquat is finally listed in Annex III of the Rotterdam Convention at the next Conference of Parties in May 2024. This does not mean a ban, but it will alert countries to paraquat coming into their country and help them to prevent it if they wish. We also hope that this evidence will support pesticide regulators to replace paraquat with safer alternatives”.

By Alicja Witwicka, Queen Mary University of London

By Alicja Witwicka, Queen Mary University of London

A recent study by researchers from Queen Mary University of London has found that the impact of insecticides on bees may be more complicated than previously thought. The study reveals that there is a surprising amount of variation in the neural receptors that are targeted by insecticides, which makes the effect of exposure to these chemicals difficult to predict.

The decline of bee populations is a growing concern worldwide, as bees play a vital role in pollinating crops that are essential for human food production. Insecticides are commonly used by farmers to protect crops from pests, but they can also harm wild bees and other beneficial pollinators. In recent years, there has been increasing evidence linking the decline in bee populations to the use of insecticides. As a result, there have been calls for more comprehensive testing of the safety of insecticides, and for policymakers to reconsider the safety assessments of these chemicals before they are released into the environment.

A study from Queen Mary University, published in Molecular Ecology, sheds new light on why it is so difficult to accurately measure and evaluate the effects of insecticides on bees and other insects. The most commonly used insecticides, including neonicotinoids, target the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), a neural receptor that is present in all animals and plays an important role in the nervous system. nAChR is composed of five distinct parts. The researchers used high-resolution molecular techniques to study which parts are used in different tissues and developmental stages in bumblebees and honeybees and found that bees use different parts to build these receptors in different scenarios.

Differently built receptors have different functions and properties. This means that the effects of an insecticide depend on how the receptor is assembled.

Variations in the receptors may explain why insecticides have such diverse effects on bees and other insect pollinators. We already knew that the insecticides harm beneficial pollinators by affecting their behaviour, memory, dexterity, immunity, and their ability to reproduce. The new research indicates a potential explanation for how these processes may be affected at the molecular level.

The study's findings have serious implications for the safety assessments that are conducted before insecticides are sprayed onto crops. These assessments typically examine one or few measures of toxicity in one or few species and attempt to extrapolate those findings into general risks for the thousands of other pollinator species that could be exposed.

The study highlights that the current testing practices lack the power to predict the impact of harmful compounds released to the environment at growing rates. The unexpected variation in the target neural receptors in various scenarios makes it impossible to apply the results of exposure experiment from one species to another.

Because the impact of insecticides on bees is more complicated than previously thought, the authors urge stakeholders and policymakers to revisit the existing protocols and emphasise the promise of using high-resolution molecular approaches to better understand how insecticides impact the health of pollinators.

Alicja Witwicka is a PhD candidate in Professor Yannick Wurm's lab at Queen Mary University of London, where she studies how various insect species react to insecticide exposure. Her research utilises molecular and statistical methods to provide valuable insights for policymakers and insecticide manufacturers, ultimately working towards better safety assessments and protection of insect pollinators.

By Eve Gleeson, ShareAction

By Eve Gleeson, ShareAction

A new briefing from ShareAction highlights why pesticide companies, and their investors, must urgently address the industry’s contribution to biodiversity loss.

Food production today has drastic impacts on nature. The food and agriculture industry is one of the biggest contributors to pollution and land-use change, such as deforestation and wetland clearing which are two direct drivers of the biodiversity crisis according to International Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Pesticides are at the heart of this system.

Pesticides damage nature’s innate ability to provide services we all rely on, such as pollination and fertile soils. In the UK alone, neonicotinoids– a class of pesticides– have been shown to reduce bee reproduction by 44 percent. It’s more clear than ever that our food system is hooked on pesticides.

Enormous volumes of pesticides are used to grow crops that are not destined for our plates. Countries like China, the United States, Brazil and Argentina, which use the highest volumes of pesticides, are using them to produce land-hungry crops like soy and maize. The vast majority of those harvests is destined for animal feed, highly processed food products and biofuels.

We have equally effective and more sustainable solutions such as agroecology and precision technologies that, if scaled up properly, can still allow us to produce enough food to feed a growing population while reducing impacts on nature.

Companies, and their investors, must be a part of the transition away from this deep-seated reliance on harmful synthetic pesticides toward more sustainable alternatives. In fact, other key stakeholders including regulators are already working to jumpstart this transition. At the global level, the recently agreed Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework explicitly includes a target on reducing the risks pesticides pose to biodiversity by half by 2030 (Target 7).

National legislation is on the way to implement this target, which we hope will specify exactly how this risk can be reduced. We anticipate that national legislation addressing this target will also align with the Framework’s Target 15. This expects companies and financial institutions to assess and publish how their activities impact on biodiversity, and how dependent their businesses are on the services that nature provides.

In fact, regional and national policymakers are already starting to regulate companies and financial institutions on the issue of pesticide-related biodiversity loss. For example, the European Union has several regulations explicitly targeting companies, such as the EU Prior Informed Consent (PIC) Regulation. The regulation requires corporations to disclosure their exports of banned pesticides. Meanwhile, countries ranging from Colombia to South Africa have developed robust Green Taxonomies to crack down on greenwashing in financial institutions that contribute to pollution caused by pesticides.

Yet pesticide companies most at fault for consistently lobbying against legislative efforts to restrict dangerous pesticides are the very same ones that dominate the pesticides market: BASF, Bayer, Corteva, FMC Corporation, Syngenta and UPL, who control 70 percent of global pesticide sales. All six of these companies continue to produce harmful pesticide products and neglect to adopt effective biodiversity strategies.

Over 2,000 investors hold shares (worth over US$10,000) in at least one of the industry’s five largest publicly traded companies, with 89 investors holding shares in all five. Debt investors like banks and asset managers regularly provide loans and invest in bonds to support the ongoing operations of these companies. Because they finance the activities of these companies by holding shares and providing them with debt, investors can demand that the companies they invest in change their behaviour.

If they are serious about change, investors need to start taking action on pesticiderelated biodiversity loss, including expanding their biodiversity strategies, advocating for improved regulation of the pesticides industry, and engaging with all pesticide companies to push for essential changes.

Over the next few months, we aim to attend the annual shareholder meetings of all publicly listed target companies - including BASF, Bayer, Corteva, FMC Corporation and UPL. At these meetings we will demand that companies start addressing the severe impacts of their pesticide products on biodiversity. Due to their market dominance, change within these companies will drastically reduce the overall impact of the pesticide industry on biodiversity. As owners and financiers of the most dominant pesticide companies, investors must urgently step up to demand this change.

Eve Gleeson is the Research Manager for ShareAction’s Biodiversity Programme. She leads research and report writing on financial sector action on biodiversity and the pesticides industry. Prior to ShareAction, Eve was a research fellow at Food Tank, a non-profit focusing on sustainable food systems, where she researched and wrote about various issues relating to the global food system. Eve formerly worked in threat intelligence for a political risk consulting firm. Read the briefing 'A Growing Problem' here.

The Chocolate Scorecard analyzes the cocoa supply chain of companies selling chocolate around the world for their performance on policy and impact in ending poverty, child labor, and destruction of the environment.

Sustainability claims made by companies are defined narrowly to refer only to their own programs, which may foster sustainable practices but do not refer to the actual status of their cocoa nor necessarily improve the actual living conditions of cocoa farmers.

Only 11% of the chocolate companies that participated in the Chocolate Scorecard have traced their cocoa to its origin. Further, on average 40% of cocoa is purchased indirectly, meaning the buyer doesn’t know who they bought from or where it came from. Without knowing where cocoa comes from you can’t possibly claim it is sustainable.

For the well-being of people, the planet, animals, and particularly cocoa farming communities, it’s critical that the industry encourages greener, cleaner ways forward. We have already lost 80% of the world’s insects – largely due to use of chemicals.

Did your favourite chocolate retailer receive a 'Good Egg Award'? Find out here.

We are the only UK charity focused solely on tackling the problems caused by pesticides and promoting safe and sustainable alternatives in agriculture, urban areas, homes and gardens.

We work tirelessly to apply pressure to governments, regulators, policy makers, industry and retailers to reduce the impacts of harmful pesticides to both human health and the environment.

Find out more about our work at: www.pan-uk.org

ISSN 2514-5770

The Brighthelm Centre North Road

Brighton BN1 1YD

Telephone: 01273 964230

Email: admin@pan-uk.org