PENNY SIOPIS

AND THE MANY JOURNEYS OF SKOKIAAN

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO 2019

TEXTS

BHUTOLEZWE KGOSI NYATHI FOREWARD

DIRECTOR

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

CLIFORD ZULU INTRODUCTION

CURATOR

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

OLGA SPEAKES

CURATOR

PENNY SIOPIS AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY

MOVING STORIES

AND TRAVELLING RHYTHMS

PENNY SIOPIS A MUSIC WHOSE DARK SIDE IS CLOSE TO THE SKIN

ARTIST

TAFADZWA GWETAI NOTES ON THE WORKSHOP:

ARTIST & WRITER

DIALOGUES WITH PENNY SIOPIS

3

National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo

BUTHOLEZWE KGOSI NYATHI DIRECTOR NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo

BUTHOLEZWE KGOSI NYATHI DIRECTOR NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

Since 1974, the National Gallery in Bulawayo (NGB) has established an indelible mark in promoting art and artists’ growth in the south western region of Zimbabwe. As the foremost visual arts institution, the NGB has the unique role and mandate of preserving and promoting the visual heritage of the region.

In line with the policy of opening up the NGB to regional and international artistic exchanges, the NGB was delighted to host Penny Siopis for her site responsive exhibition “Moving Stories and Travelling Rhythms: Penny Siopis and the many journeys of Skokiaan”. Bulawayo has a rich history and we were delighted for Penny to explore the city’s musical heritage through the lens of August Musarurwa’s hit song Skokiaan from the 1950’s. The exhibition proved that indeed heritage can be a source of contemporary creativity.

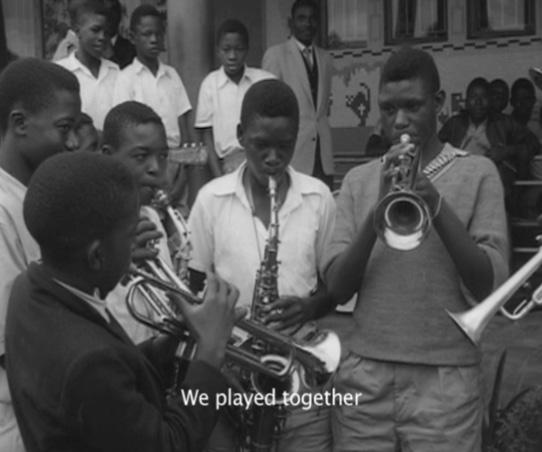

The general public in Bulawayo enjoyed the exhibition as it brought to the fore the musical exploits of August Musarurwa. 1 Young musicians in the city particularly patronised the Gallery during the exhibition as they sought to derive inspiration from the story of a since departed local musician who achieved global recognition.

As a public cultural institution, the NGB desires to expand its scope of reach and influence in Southern Africa and beyond. It is through exhibitions by artists such as Penny Siopis that resident artists at the NGB and in Bulawayo in general get to have their creative horizons widened.

Committed to pushing artistic frontiers in the city, the NGB is receptive to conceptual and experimental work. Through cultural exchanges, a diversity of cultural expressions is enhanced.

At a personal level, Penny’s exhibition is of great significance. It was the first exhibition by an international artist that I presided over upon assuming leadership as Regional Director of the NGB. I joined the NGB in May 2019 and the exhibition opened in June 2019. Further intriguing for me was the presentation of the subject matter – a mix of mediums namely paintings in ink and glue and a video artwork. The depth of research and creative expression was the ideal depiction of the intellectualism of the visual arts that I yearned to see on the walls of the NGB.

5

OLGA SPEAKES

CURATOR

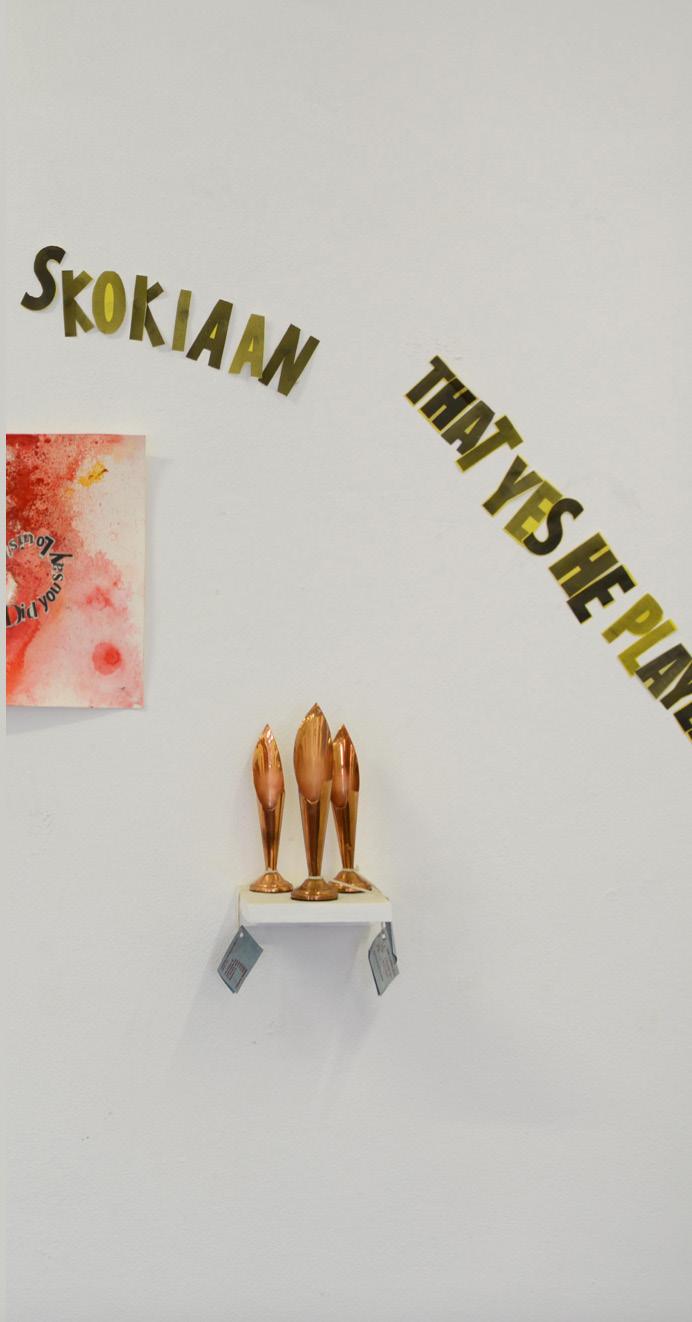

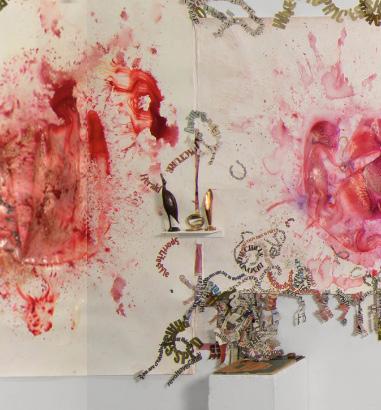

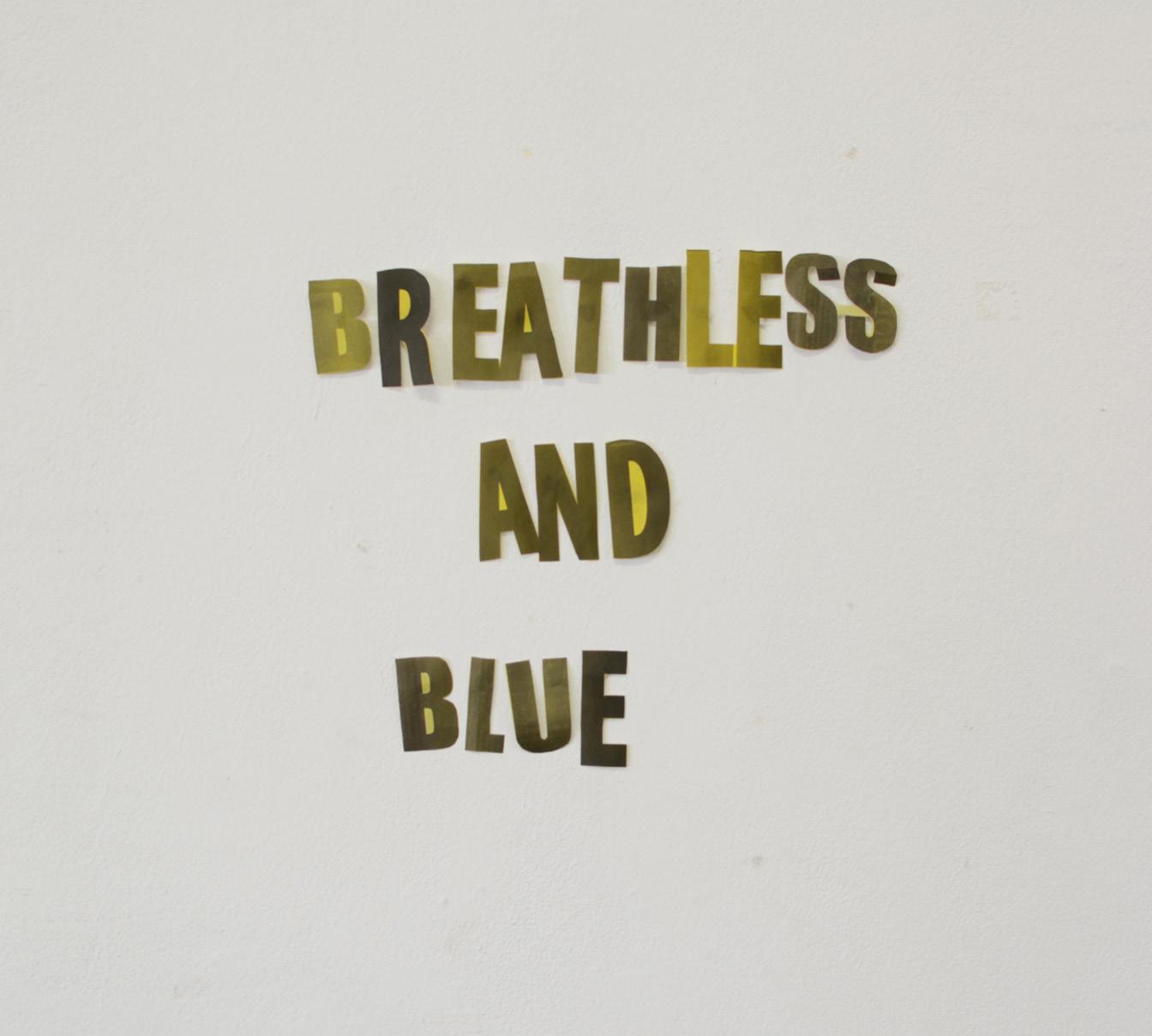

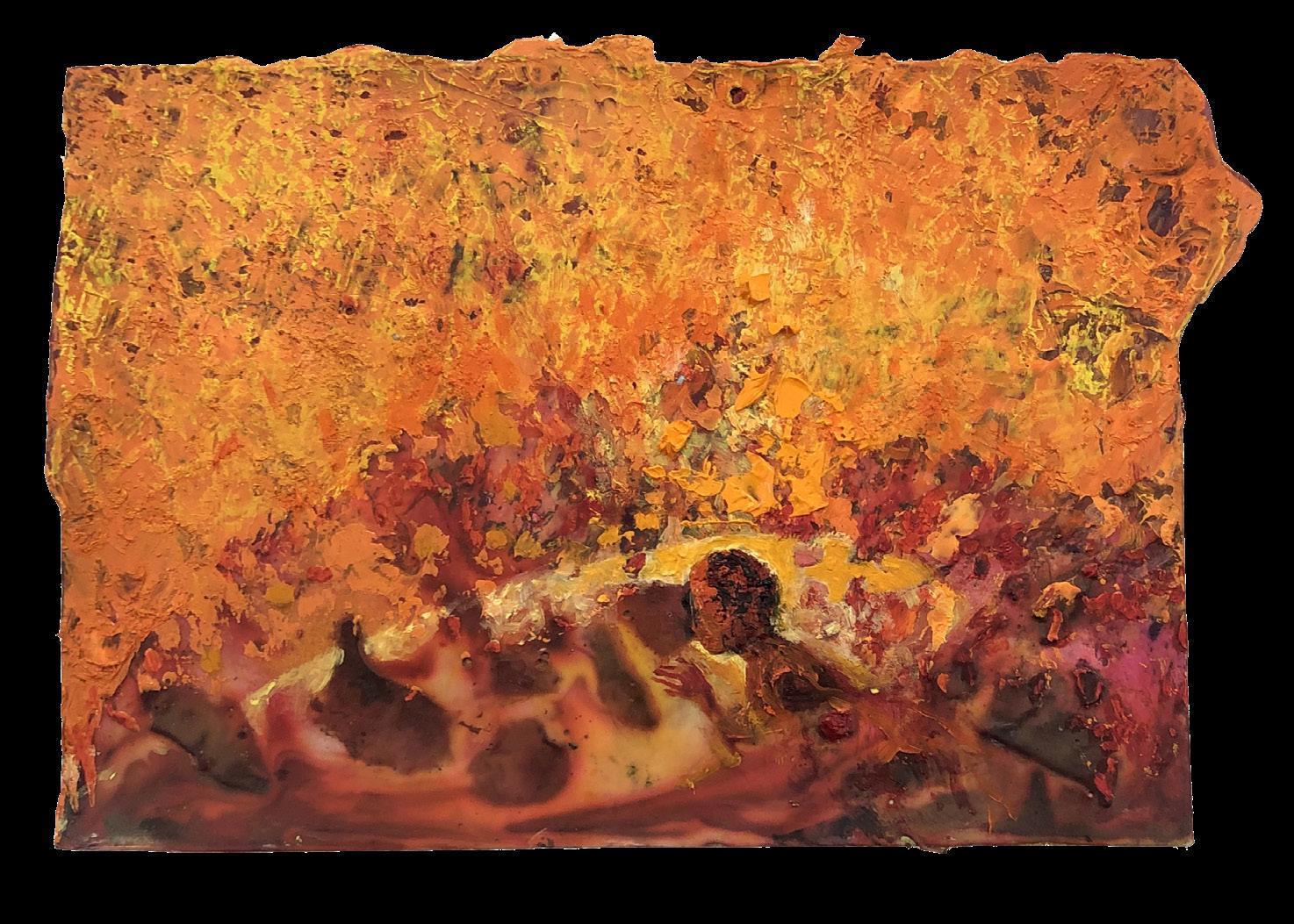

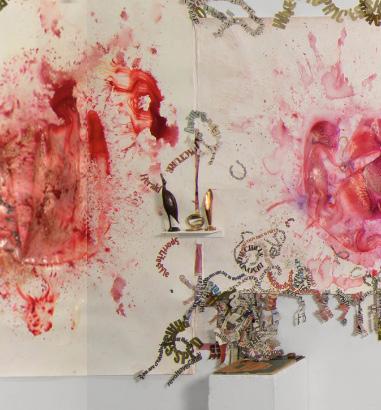

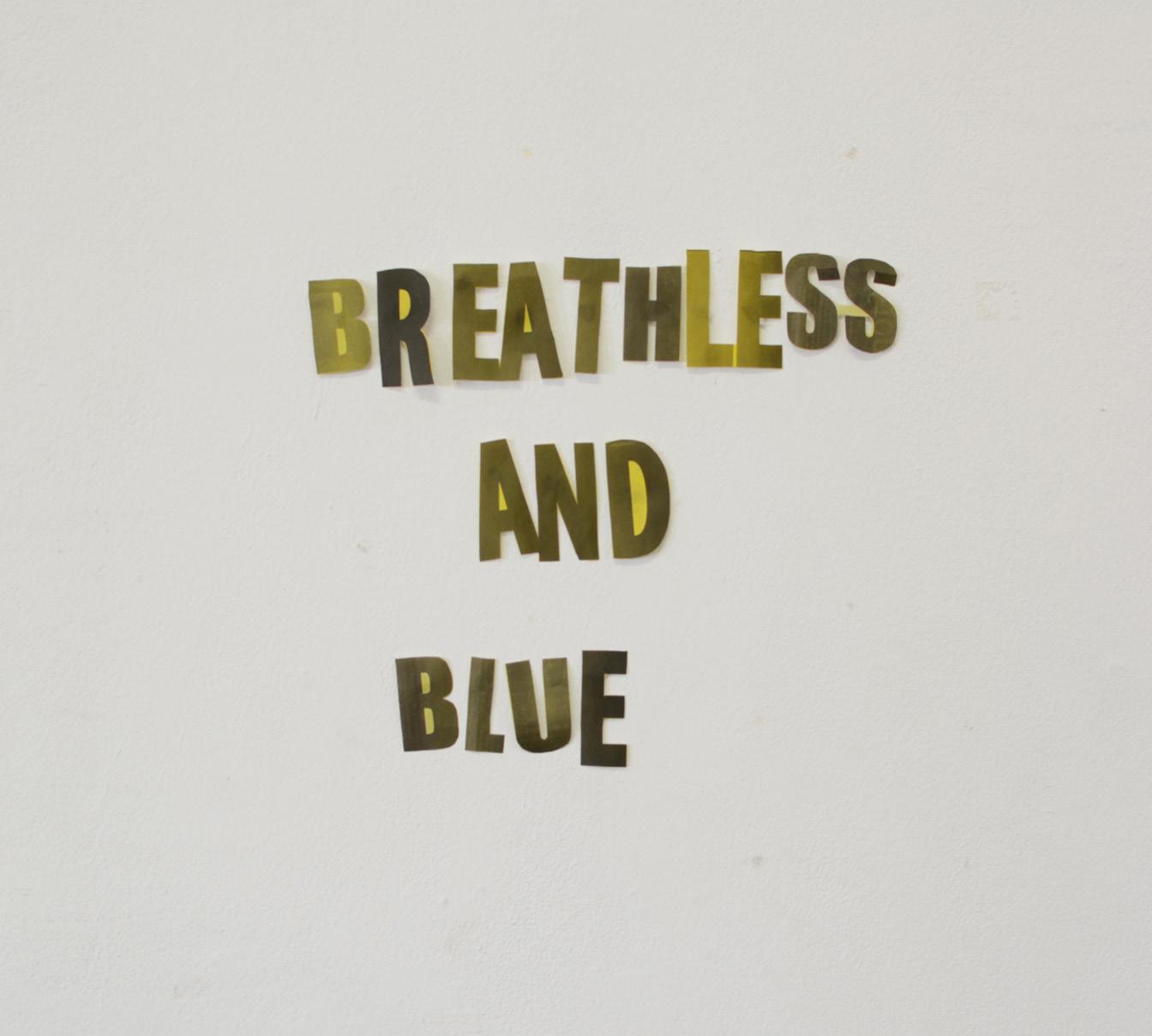

A sprawling site-responsive installation of drawings, newspapers and found objects, entitled Tuning Time, extending across the curvatures of spacious walls; Breathless and Blue, a set of small paintings in ink, glue and oil paint inhabiting the opposite wall; a video artwork Welcome Visitors! in the next room filling the air of the gallery with familiar melody; a documentary film 2 exploring the histories of township jazz in Zimbabwe – all these elements are brought together in the historic rooms of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo as part of the exhibition that sets in dialogue the many narratives and memories, fictional and documentary accounts that were inspired by the story of Skokiaan. 3

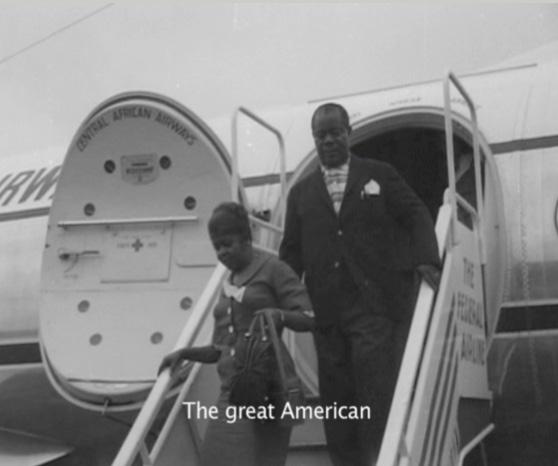

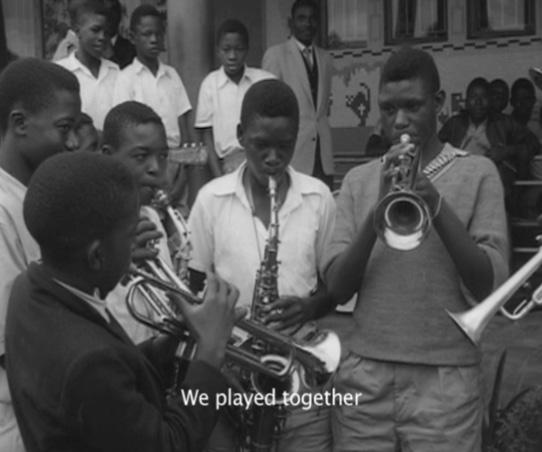

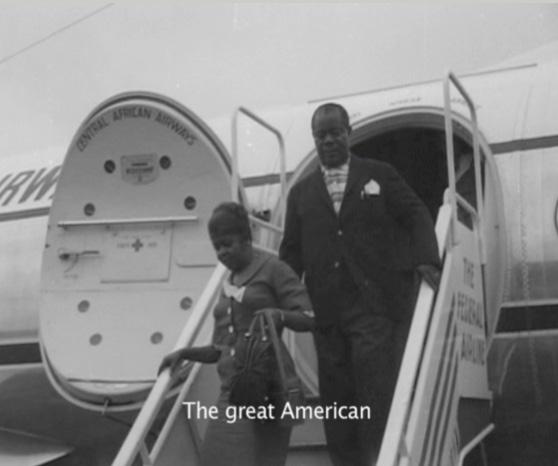

This piece of music was composed in the nineteen forties by Zimbabwean August Musarurwa and played by his band Bulawayo Sweet Rhythms It was later performed around the world by many musicians, including Louis Armstrong, who visited the country in 1960 and met Musarurwa.

Penny Siopis’s video work Welcome Visitors! uses montage techniques to combine found footage – anonymous home movies of the sixties and some media sequences of Armstrong’s visit to Africa – with text and music, creating a narrative that speaks beyond the specific historically documented circumstances of the encounter. The installation pulls together many threads that emerge from the story and follows them, through the materiality of the objects and associative connections,

all the way into the present moment; the use of newspapers locates the work on the steps of the gallery where newspaper sellers continue to write history every day with their news headlines.

The documentary by Joyce Jenje Makwenda on the history of Zimbabwe

Township Music provides a wider context for the narratives explored in the artworks through many personal interviews of those who keep history alive in their memory. It draws attention to the journeys of migrant workers that connected Bulawayo with Johannesburg and the wider history of jazz music that moved across borders and beyond restrictions imposed on people by colonial regimes on the continent.

The voices of the artist and the historian are echoed by the voices that animate the pages of Yvonne Vera’s famous novel The Stone Virgins These voices reclaim their own memories of Satchmo 4 and Skokiaan from histories that excluded them. Their words, which Siopis uses in her installation, and Vera’s intense, lyrical and rhythmic style, which Siopis invokes in the materiality of her paintings and their title, form another thread that weaves itself into the exhibition where journeys between memory, history and the present moment never cease to reveal new truths that could not be defined as either fact or fiction.

Welcome Visitors! single-channel video, sound 10 min 17 sec 2017

9

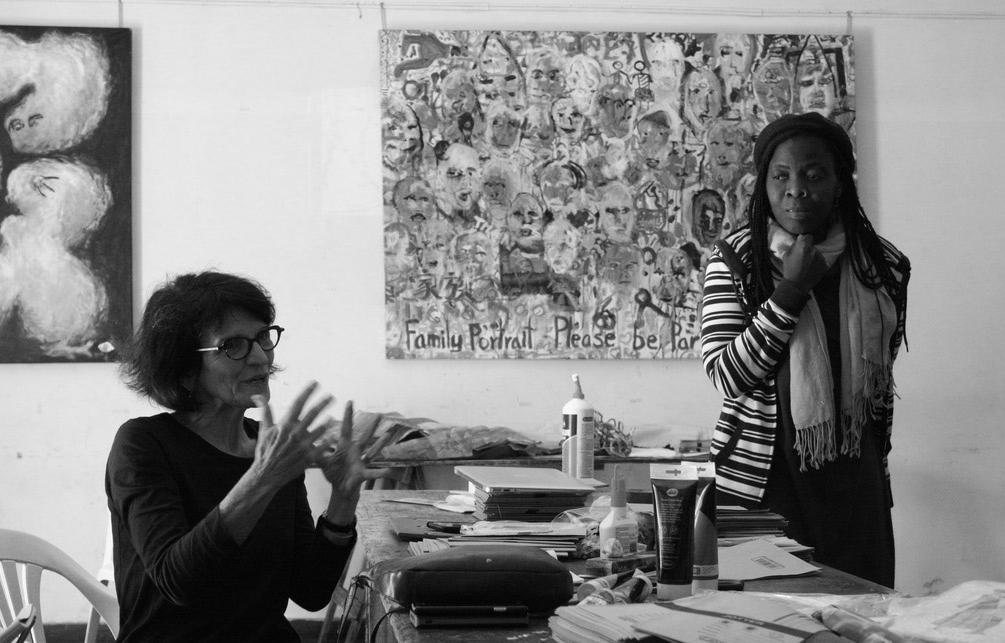

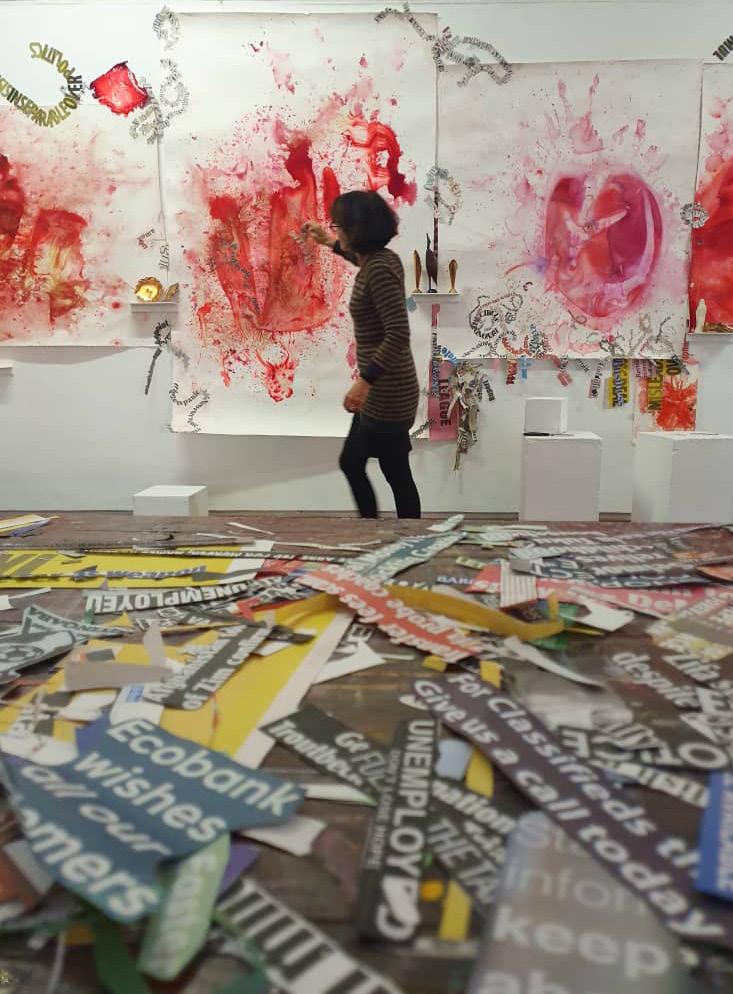

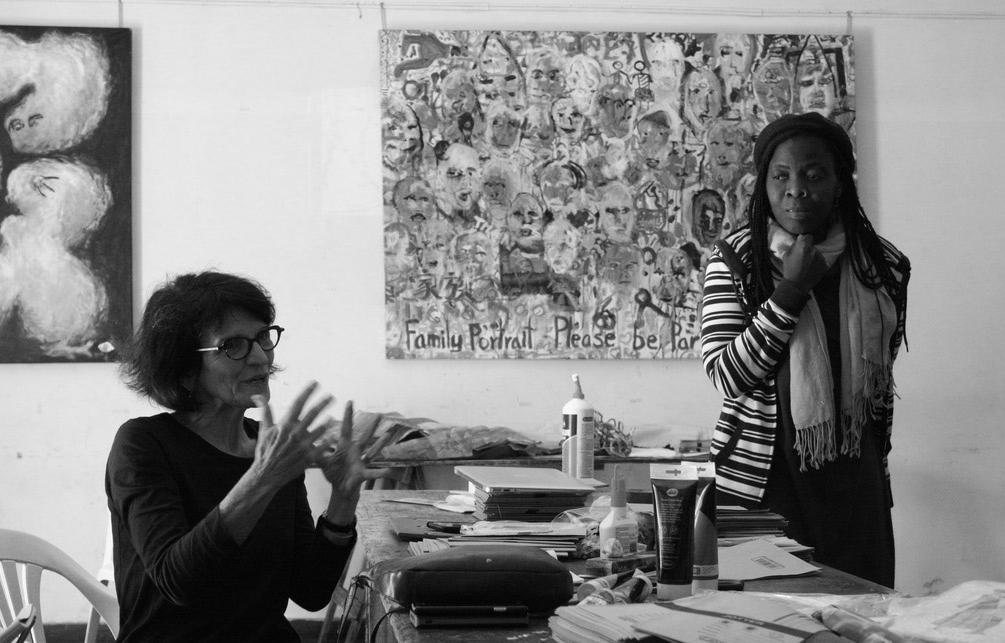

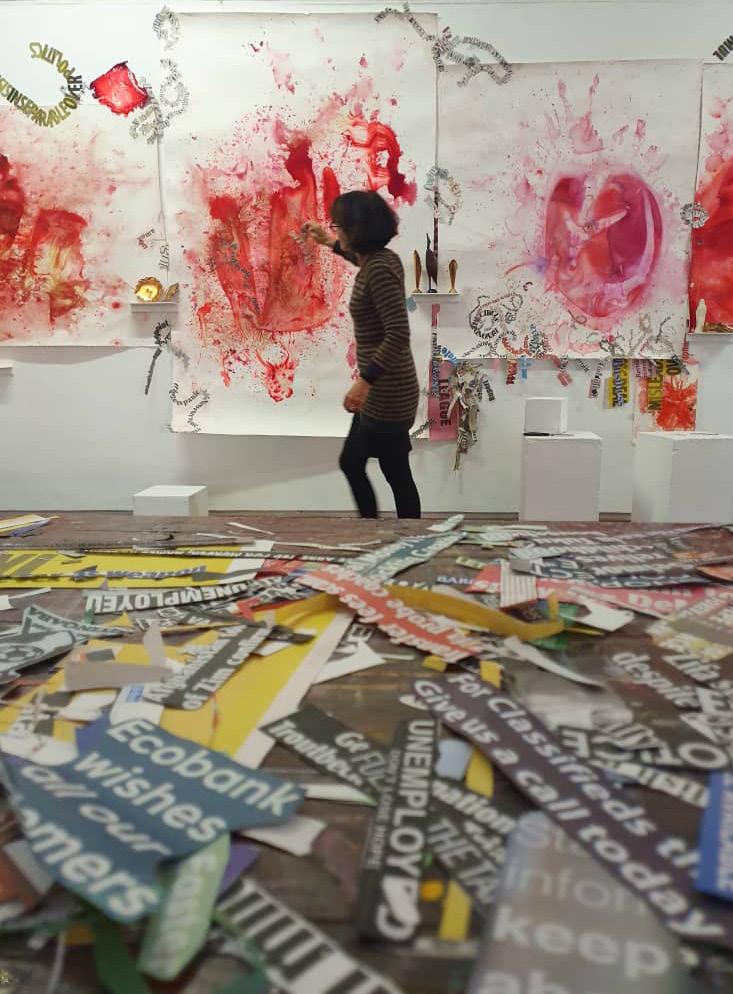

Penny Siopis making Tuning Time Tuning Time (detail) site-specific installation 2019

PENNY SIOPIS AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY IN BULAWAYO: THE STORY OF SKOKIAAN

CLIFORD ZULU CURATOR, NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

Zimbabwean art has had its fair share of frustrations and triumphs in the past twenty years. Navigating the expectations against realities of the local and international gallery standards has been a roller coaster. At the time when the majority of Zimbabweans were beginning to appreciate contemporary art practice in Zimbabwe, many factors have come to play and the consumption and appreciation of the arts has suffered the most.

To the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo (NGZB), the residency 5 programme established in 2017 ensures that we are providing services most conducive to the artists’ creative process. Instead of articulating the impact, it is essential to encourage greater investment and opportunities for artists to develop new work. The interest and participation in the residency programme by a South African artist, Penny Siopis, was a welcome surprise to everyone, at a time when many people were not so keen on the country. To the NGZB, this was an honourable opportunity to assess the capability to host an international award winning artist in a residency in Zimbabwe. For the administration of the residency, it was a lesson about the importance of research, planning and being organised. The exploration of the story of Skokiaan in the project titled “Moving Stories and Travelling Rhythms: Penny Siopis and the many journeys of Skokiaan” was a powerful awakening to the importance of archiving.

The residency was structured in two parts, with the first part in April being a research trip by the artist, Penny Siopis, and the curator, Olga Speakes, with whom she was working, to prepare for the exhibition, the talk and the artists’ workshop. The trip also sought to identify materials for Siopis’ site-specific–installation, that would reflect the nature of the exhibition site being in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, where the music composition Skokiaan was conceived and performed for the first time by a legendary Zimbabwean jazz musician, August Musarurwa.

Other objectives included getting to know the space for the installation, meetings with a Zimbabwean music archivist and researcher Joyce Jenje Makwenda and the screening of her documentary; establishing contacts with locals who may have known Musarurwa or had attended Louis Armstrong’s concert that took place in 1960 at the McDonald Hall 6 in the Mzilikazi district in Bulawayo. The initial research trip also sought to invite the local community who may be interested in the project.

The second part of the residency that took place a few weeks after the research phase was more hands on, putting into practice and working towards creating work for the exhibition, setting up and running a three day artists’ workshop with local Zimbabwean artists 7 from different parts of the country and conducting an artist’s talk by Penny Siopis for the local art community.

Key to the production of the exhibition, with the opening marking the its end, the residency managed to bring together various artists from Zimbabwe to a creative and intellectual environment that resulted in working together and sharing ideas and experiences across cultural and creative politics between Bulawayo and Harare.

The results were astonishingly powerful and marked the beginning of sharing spaces and working collaboratively between artists in the south and the north of Zimbabwe.

The Visiting-Artists-in-Residency Programme is the National Gallery of Zimbabwe’s response to the challenging environment that makes it hard to maintain visibility and keep the visual arts in the country alive. The residency has been nurturing some of the most promising creative work today, offering a platform for inspiration and support to local and visiting artists at a time when outcomes are ambiguous and hard to quantify.

The residency encourages a fragmented society to celebrate creative people and creative process; it values experimentation and the exploration of new ideas. Enabling freedom to create in a new space is necessary for all creative accomplishment. It is more important now than ever for artists to have the freedom and support to develop work without expectations of immediate material outcome. But supporting artists and their creative development is a risky business, it is not easily measured by its impact or income generated, results often emerge months or years after a particular project. The greatest impacts - on the individual artists themselves, on their communities and audiences – are not always tangible. But they do have a cumulative impact over time. Perhaps, the critical question is how the gallery and stakeholders assess the impact of the residency programme.

A MUSIC WHOSE DARK SIDE IS CLOSE TO THE SKIN PENNY SIOPIS ARTIST

I first visited Bulawayo around 1995. I had come to deliver the opening address for an exhibition of a Bulawayo artist who had been my student at Wits. 8 It was then that I met Yvonne Vera just as she was about to take office as Director General of the National Gallery - a position she held for five years. In April 2019 I returned to the city, this time for a site visit for my own exhibition Moving Stories and Travelling Rhythms . The building held the same grandeur as it had done in the nineties, and the polished wooden floor still creaked under my step. The difference was that I had since met Yvonne Vera the writer, whose words had filled me with so much more knowledge of the city. And her presence filled the gallery.

Two months later I returned to install my show. That’s when I met Vera’s mother, Ericha Gwetai. We had tea in her home. We looked at photographs, spoke for long. The afternoon light faded. There was no electricity in Bulawayo. When we could no longer see each other, Ericha fetched a portable radio which had an internal light. She turned down the sound.

writer who could turn on her history, explore trauma, violence and taboo subjects like rape and infanticide. 9 She was self-reflexive, and her work asked questions about the responsibility of art, of the artist, and all in the most poetic prose. But even when the sensuousness of her non-narrativity, the texture, colour, tone and fluidity of her form was embraced, this discourse still left me wanting. For what?

I am not sure. I seemed to need another way of ‘reading’ her, away from academic constraint and product; more in tune with provisional forms of expression. There is so much movement in her ellipses. And her imagery has the paradoxical mutability of ancient still imagesthey animate when called up, they sing. I wondered about her actual process of writing, how she engaged in the act, how things came together. I imagined she improvised, drawing on all of her life and what came before.

It was my own improvisational way of working that brought me back to Vera. In 2016 I was researching the jazz composition Skokiaan in making my film Welcome Visitors! 10 The tune, famously covered by Louis Armstrong, was composed by Zimbabwean August Musarurwa.

I first encountered Vera’s work in an academic context, framed within post-colonialism and feminism. Here was a gifted African woman

The work was to become the heart of Moving Stories and Travelling Rhythms, sparking the other works on the show - an installation,

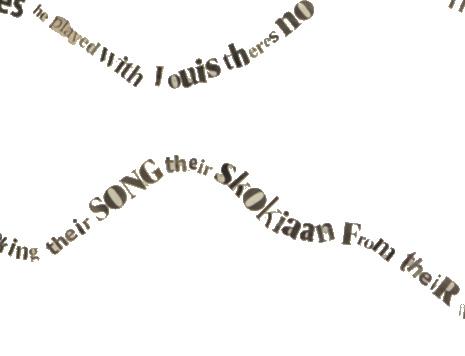

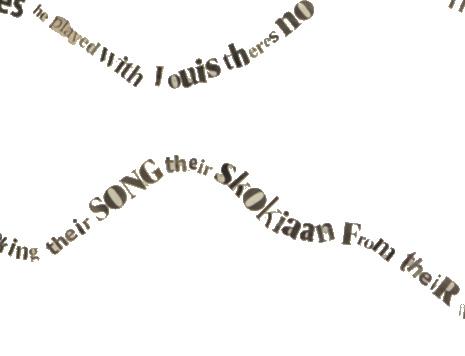

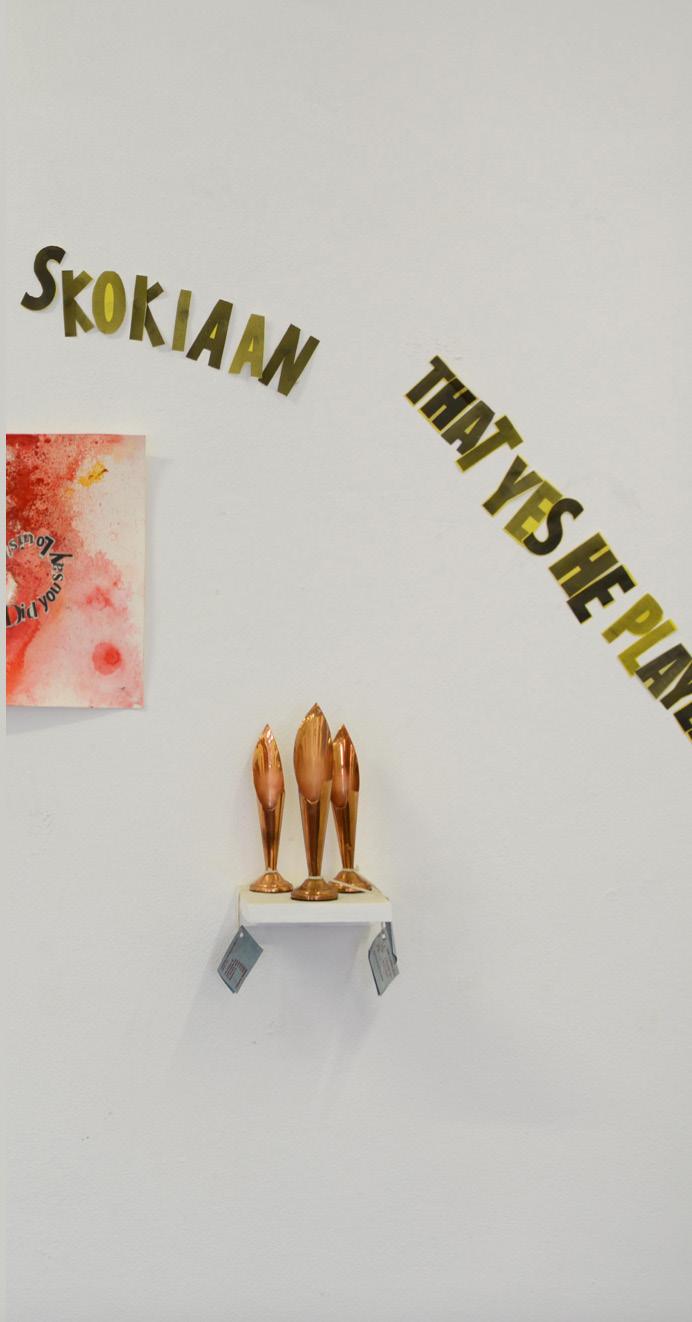

Tuning Time (details) site-specific installation

Tuning Time, and paintings Breathless and Blue Tuning Time was improvisational, site-responsive and ephemeral. Both works reference Vera’s words, the installation doing so quite literally in its intermingling of her phrases (as paper cut-outs) with images and objects, and with the paintings in more opaque ways, dwelling in their viscous, scored and coloured surfaces. Writing is not painting. Painting is synoptic, its temporality not sequential. But text has a

body in and of the book. It is imprinted on the page. It has a look, shaped by its format. A visual rhythm. Texture. Usually black ink. A graphic code like musical notation where you can imagine the sound you read. Vera often speaks of images as ‘frozen’, and sees them as entities beyond their material reality; as, say, photographs. If you repeat the ‘frozen’ moment you get movement, rhythm, like film, like music.

2019

Her words:

I’ve always been visually oriented… When I’m writing – for example, when I was writing WithoutaName (published 1994) – I start with a moment – visual, mental – that I can see, and I place it on my table, as though it were a photograph. In Without a Name, I had this ‘photograph’, or series of photographs, of a woman throwing a child on her back. This photograph is a very familiar scene in Africa. If you walk down the street, you’ll see it – a certain style and movement, a certain familiarity. And this moment came to me, how it’s done: the child is thrown over the left shoulder onto the mother’s back, she pulls the legs around her waist. Then I change it in one aspect: that the child is dead. But the mother performs the same action. So, I take this series of images, and I put them on my desk, so to speak, as I write. This moment, frozen like that, is so powerful that I can’t lose sight of it, visually or emotionally. 11

Putting your imagination on your desk, as if it were a photograph - this says so much about embodied imaging, how body archive works, how you might know an image before you see it. And you don’t know why you know. Historian Terence Ranger, a close friend of Vera’s, reflects on this, telling of an occasion when he showed Vera a photograph on display at the National Archives in Harare. 12 There Yvonne saw for the first time the enlarged version of the photo of African men, captured in 1896, hanging from a tree. 12 She was astonished that the photograph fitted so exactly with her description of hanging men at the beginning of Butterfly Burning , 13 the sense of the men swimming in the air, being as vivid as in the book.

And music?

Music is everywhere in Vera’s writing. And, as noted earlier, it was music – my tracking Skokiaan to its Zimbabwean origins - that brought me back to Vera. Skokiaan plays a small but important part in The Stone Virgins 14 I had not noticed it when I first read the novel, being bound too strongly perhaps to the content of the narrative, too much on that side of emotion. Or perhaps it was my immersion in the music that opened the way.

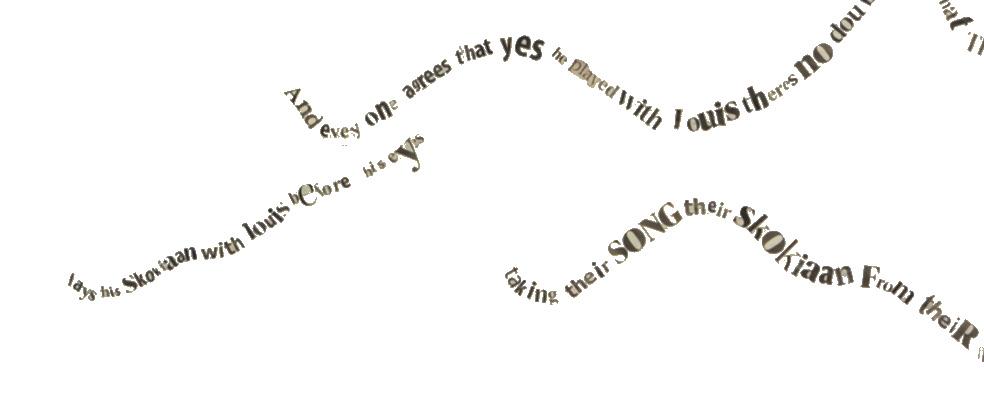

How did Skokiaan feature in The Stone Virgins? In the opening chapter there is old Bulawayo. A half-lit bar at the Selbourne hotel in Selbourne Avenue – the road that Vera says is ‘like an umbilical cord’ 15 joining Bulawayo and Johannesburg, going straight to the gold mines. The hotel is still there. Selbourne Avenue is now Leopold Takawira Avenue. Here are Vera’s words:

In a secluded bar black men recite all they can remember about that time when Satchmo was suddenly in their midst, taking their song, their song ‘Skokiaan’, from their mouths and letting it course through their veins like blood, their blood. The wonder of it. The enduring wonder of it. The love of it. The Bulawayo men play it again in their half-lit bars, wondering if their memory is true, if indeed, they have touched the arm and sleeve of that glorious man, that Satchmo? 16

There is more:

The band leader sits back in his pale blue shirt and his navy blue trousers and his sky-blue tie and his deep blue voice and softly says Did you say Louis… Louis Armstrong… He rises. He plays a trumpet. Plays his Skokiaan with Louis before his eyes, as far as he can imagine to the left, under that dimming lamp and smell of kerosene light

Tuning Time (detail) site-specific installation 2019 17

And everyone agrees that yes, he played with Louis, there is no doubt about that.

He is Satchmo

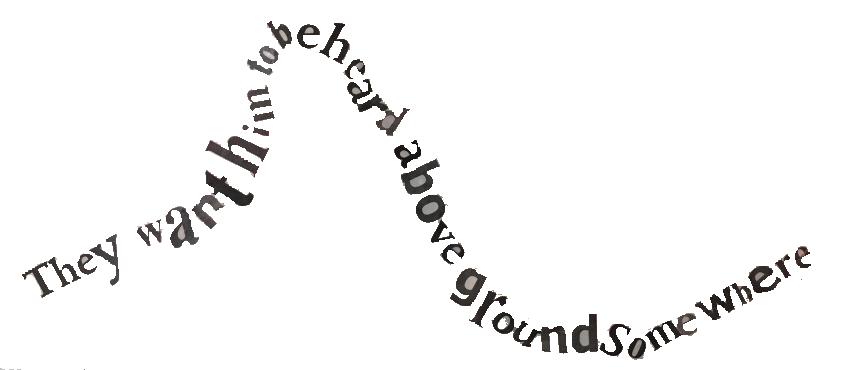

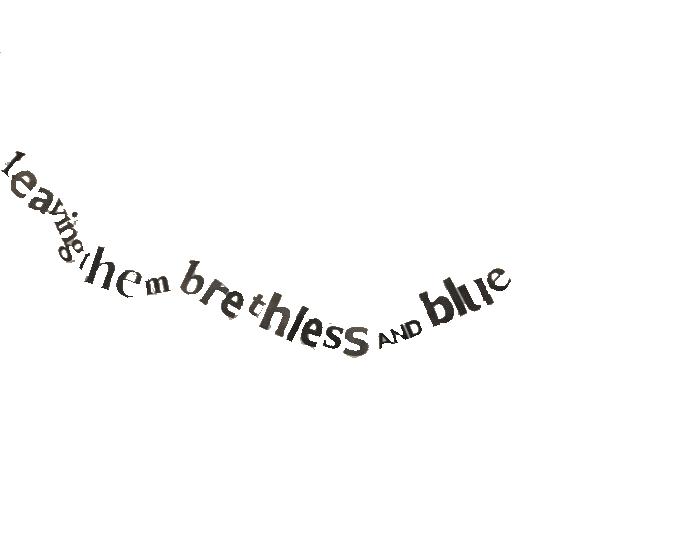

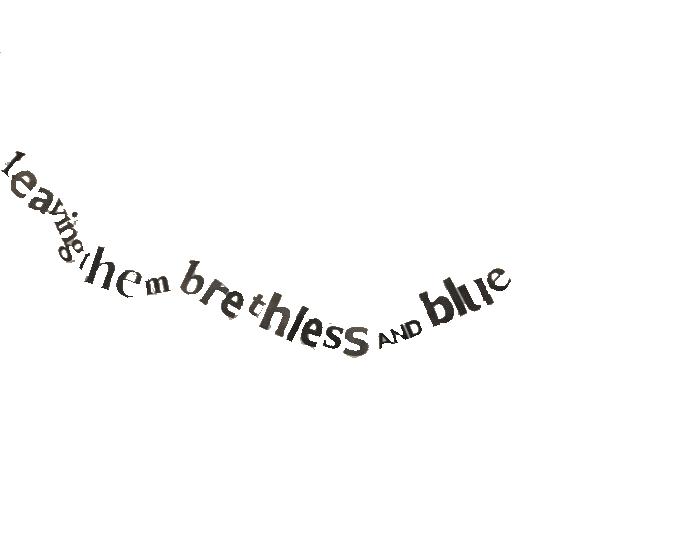

They want him to be heard above ground – somewhere. This is the day they are all waiting for. Not for Satchmo to come, and go, and play their ‘Skokiaan’, leaving them breathless and blue, but for this man to carry their own desires above ground –somewhere… All they want is to come and go as they please… 17

Armstrong recorded two versions of Skokiaan, one vocal, nicknamed ‘Happy Africa’, with its exoticising lyrics. In a take on its significance in The Stone Virgins from a literary perspective, Ann Elizabeth Willey reflects:

negotiate every day. “Skokiaan,” with its lyrics about the happy black man in his jungle bungalow, has in fact not escaped the discipline of the South African colonial regime, has been sent down into the mines with the male migrant workers. […]The anxiety about the competing modernities of the colonial order vs. the implicitly male nationalist resistance invites another question, the question of the gendered spaces of modernity. Here again, there is a critical consensus that one of the key concerns of The Stone Virgins as a novel is to imagine female ways of occupying the spaces of Bulawayo and, metonymically, the new Zimbabwean nation.18 The interpretation resonates, as it does with Welcome Visitors! where there is symmetry and asymmetry with Satchmo 19 and the men who invoke him. Vera’s words triangulate the scenario. But she is supple, impossible to pin down.

Vera’s use of Skokiaan in the first chapter opens up multiple spaces for a critique of this diasporic flow as necessarily empowering. […] In describing the crowd as “breathless and blue,” Vera leaves open the possibility that while they might be breathless with wonder, they might also be breathless with outrage over the missed opportunity to voice their desires, to take their desires into the open. Instead, their desires are covered over with the same racist discourse they must

Music is everywhere in Vera. Butterfly Burning is full of kwela 20 . In life she loved many a song with favourites being Nina Simone’s To Be Young Gifted and Black and Bob Marley’s Redemption Song 21 She tells, in her short story Dead Swimmers, about the song Furuwa:

It is the story of two lovers sitting on the crest of a wave. The music of the waves is their music, and they are swallowed by crystal showers and the clearest sand where water meets land. Then a deep foam surrounds them. They disappear, beneath it, in the music of their love.

They die a happy death. They die like stars falling from the sky. They have been accepted by the great water spirit which blows upon the shimmering fabric of the sea and makes the water ripple in a violent whiteness, then wave flows wave. Neither my mother nor I have ever been to the sea. However, we have no doubt that Furuwa is a good song. 22

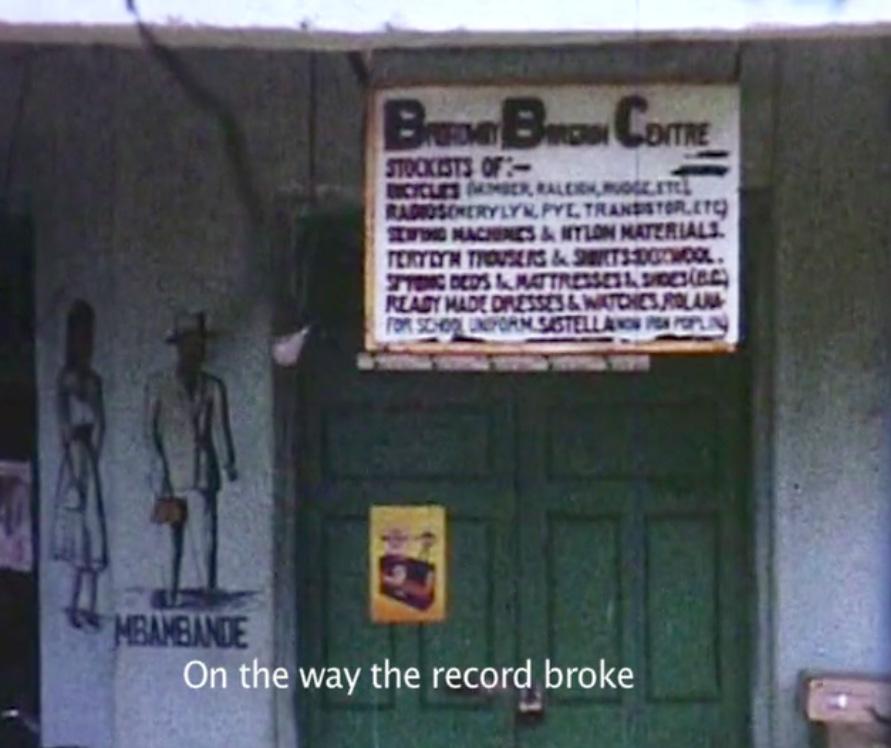

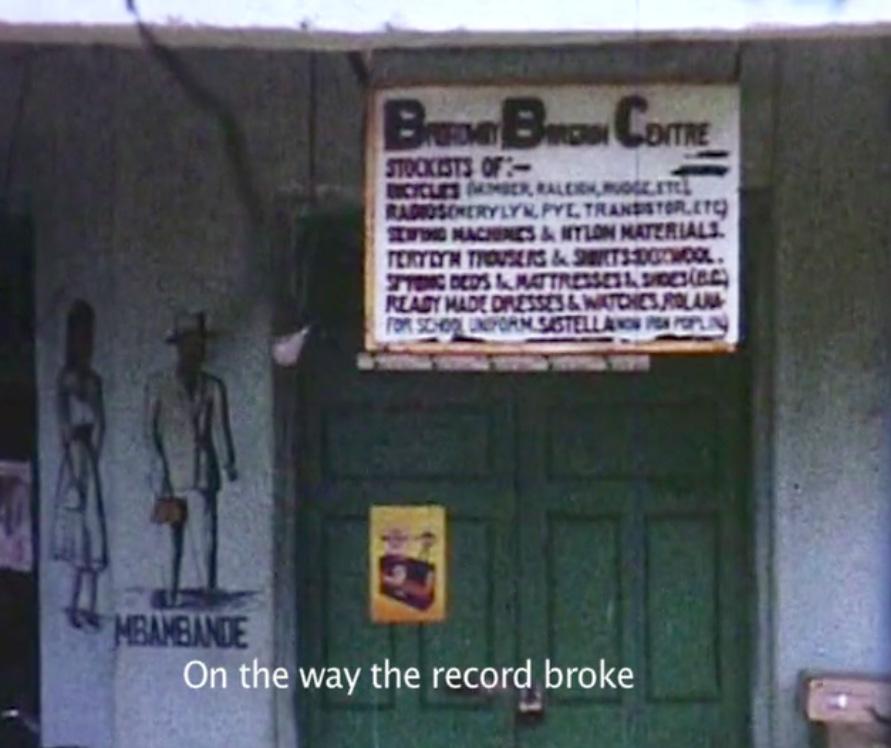

The story goes, her mother sent her the record – the writer was at boarding school. The record broke on the way. She spoke to her mother, the story continues:

Thank you for the waves. The waves have been broken’. I could hear my mother’s cry as I wrote that. Her sound was louder than that of the waves. I thought perhaps if I have a child I will call her Furuwa 23

Vera’s mother writes in Petal Thoughts 24 that Furuwa was a favourite of mother and daughter, and they danced to it at Vera’s school graduation. Later she sent the record to Vera when she was living in Canada.

‘I posted a record of Furuwa to her because I knew she missed the song.’ 25

The record broke into pieces. Again, she reflects:

‘I sang the song Furuwa to Yvonne when she was lying on her deathbed in April 2005.’ 26

Vera muses:

I am still discovering my music … I spent years without a music system, just reading. I am musical in my writing… I think if I could play the mbira, I would have great spiritual harmony. It is a music whose dark side is so close to the skin … It is our most poetic music yet I feel getting into it might shatter me. I feel that about things that are too beautiful [… ] However I do not

19

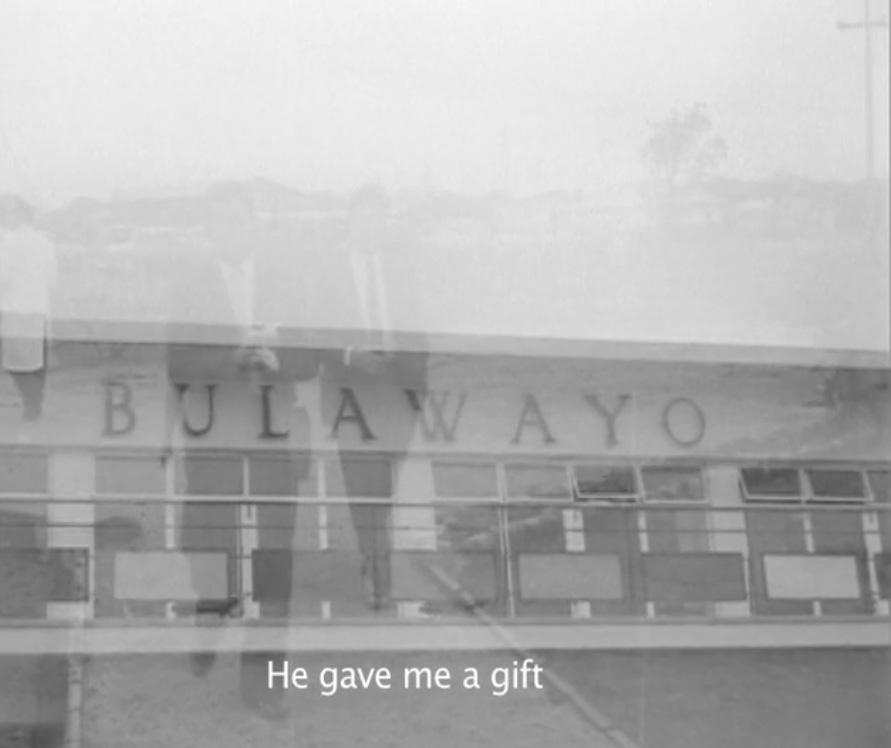

Armstrong features in Welcome Visitors! in the bits of documentary footage of his 1960 visit to Zimbabwe. 28 The footage is mixed with old 8mm home movies of that time, of which I have a large and ever-growing archive. These are films that I find in thrift shops. I have no idea who shot them, or of the people and places caught in the sweep of the camera. I cut sequences and combine them with texts that I write from archives and my imagination. The text appears in the form as subtitles, which says something about translation but is really about what happens in the head when music and image merge with reading. The film is projected, the beam of light making its own impress on the acts of reading, looking, listening. Vera talks about light in art. In film. In painting. Especially Van Gogh. She reflects that painted light is also the absence of light. 29 She is right. Unlike photography painting is the illusion of light. But the ambient light in which it is seen has sway - especially if the surface is textured – as the light plays on it, catches it. This is not the capture of light that creates the frozen image of the photograph. Movement is always there. I digress.

I made Welcome Visitors! for a group exhibition in New Orleans in 2017. Titled The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp, 30 the show explored cultural syncretism and the global South. The curator 31 asked me to reflect on the links between Southern Africa and the American South, and arranged a site visit to the city as a starting point. I had no preconceived ideas, but my head buzzed with jazz and images of music migrating across the Atlantic. As my plane landed in New Orleans, the sign LOUIS ARMSTRONG appeared - the name of the airport. A world opened up for me. The next day I visited a charity shop. There I found a significant object, a decorated coconut that linked back to Armstrong, and led me to Skokiaan. The coconut had ZULU inscribed on it in gold. ZULU, I learned, was short for Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club, an African American fraternal organisation in existence in New Orleans since 1916. 32 Its members parade at Mardi Gras every year. The coconut is a popular gift thrown to the crowd from the floats. ZULU has a complex history which involves adopting ‘a Zulu identity’, controversially expressing ‘Africa’ in ways including blackface. All in the spirit of resistance to the very stereotype. Armstrong was a member of ZULU. Every Mardi Gras ZULU chooses a king to crown the float. Armstrong was king in 1941.

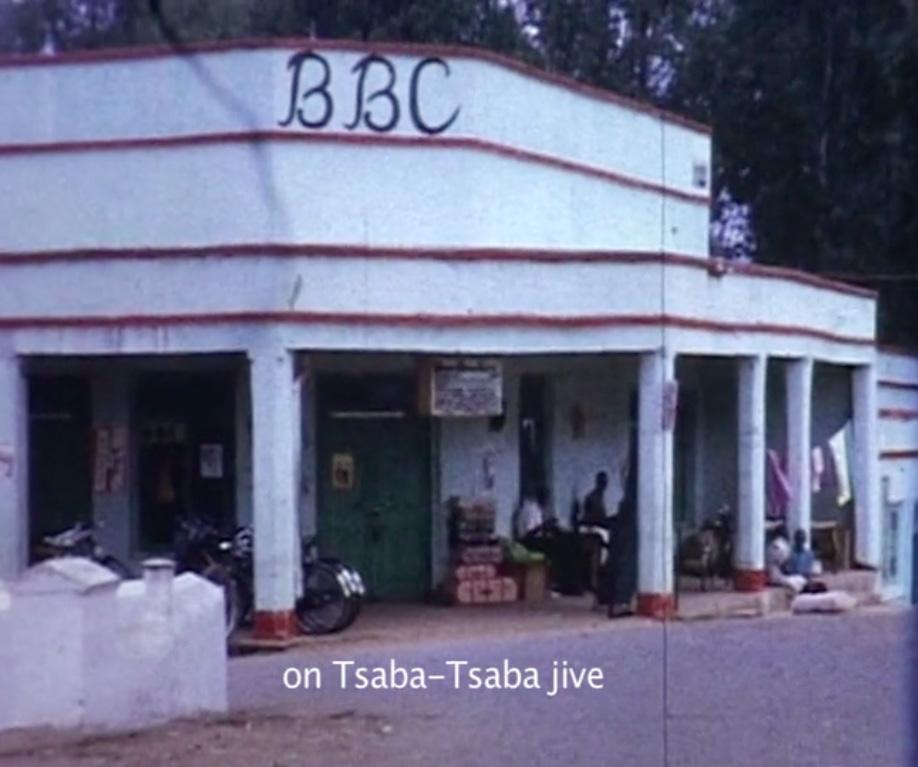

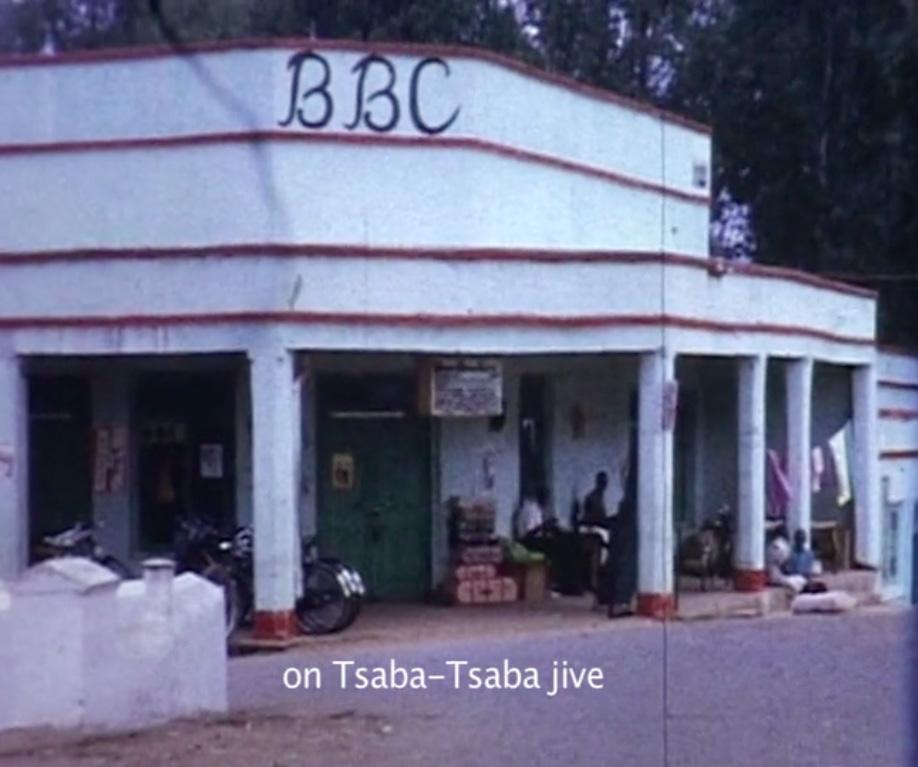

I had always thought that Skokiaan was a South African song. One record label said as much. But it was also labelled a Zulu song. Musarurwa first recorded Skokiaan in 1949 with his band, ‘The African Band of the Cold Storage Commission of Southern Rhodesia’. The composer also played the sax in this recording and the one that followed, but by then the band’s name had changed to ‘Bulawayo Sweet Rhythms Band’. Skokiaan was a hit in the United States. The record had cracked on its journey across the Atlantic, but the Americans could hear the song through the crack, and loved its tsaba-tsaba jive. 33

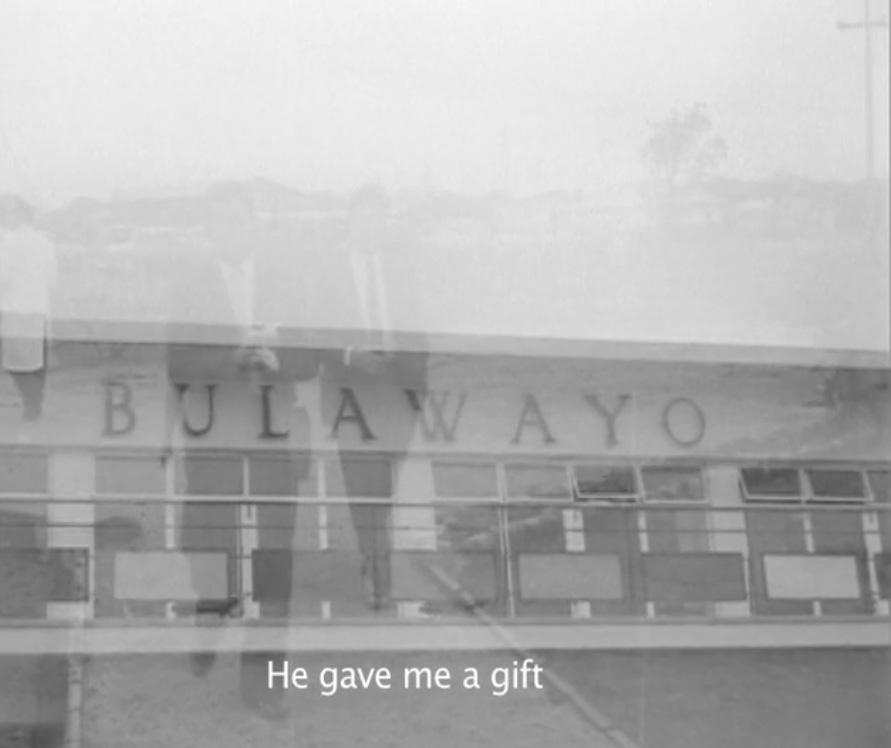

Armstrong recognised the greatness of Musarurwa and, in 1960, on his tour of Africa, came to Zimbabwe to meet the composer. In Welcome Visitors! there is a great shot of him on the runway of the old BULAWAYO airport.

Most Zimbabweans know Skokiaan, and that it is named after an illicit brew made by Africans in defiance of the colonial authorities who outlawed the drinking of any beer other than that purchased in official beerhalls. Playing Skokiaan loudly in the townships was a way to warn people that the police were coming. It was also a tune to dance to. To enjoy.

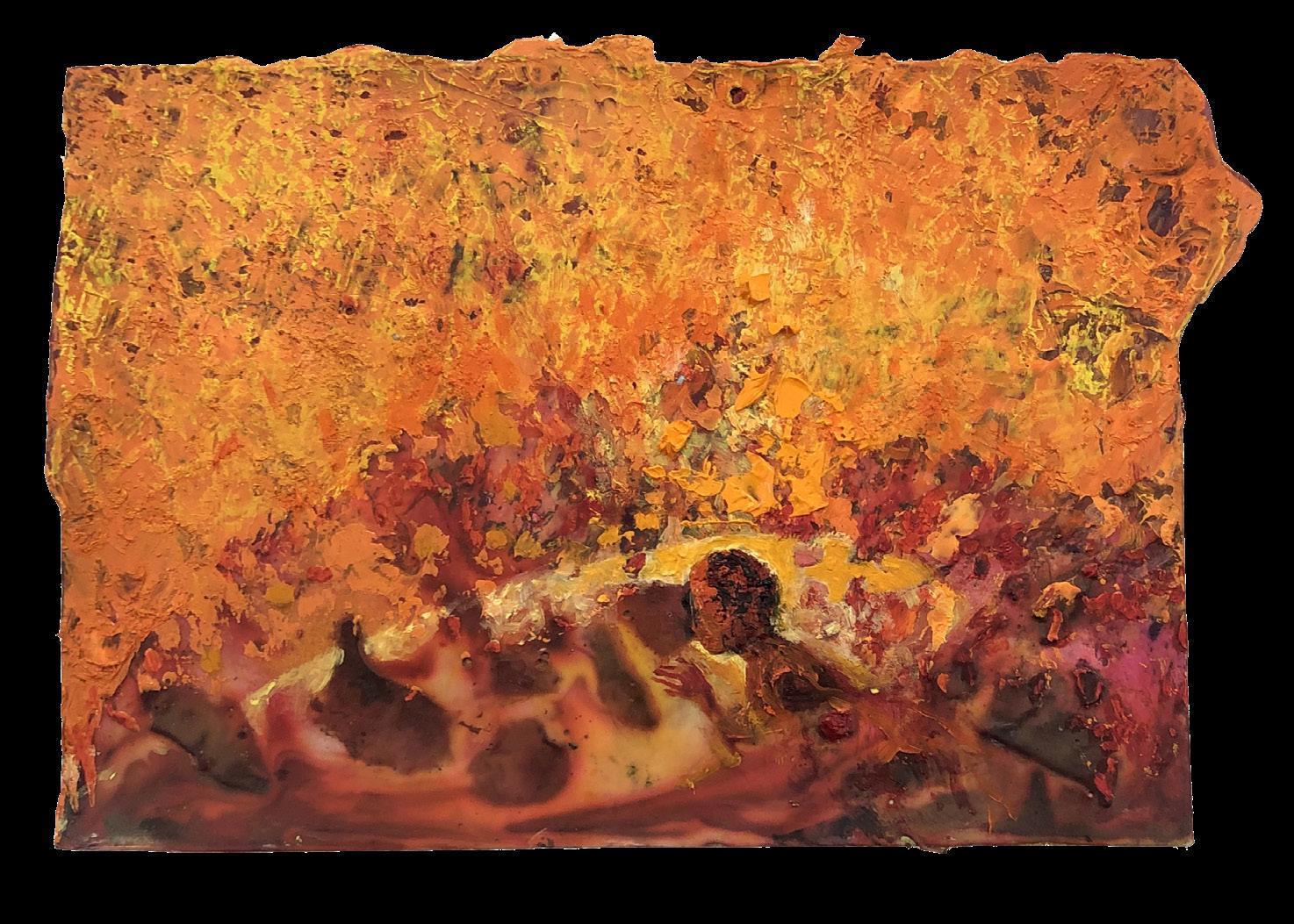

While Vera’s Skokiaan doesn’t feature in Welcome Visitors! in a direct way, it is present in the material traces of the film and its montage effect which is full of gaps ready to be filled. Montage shapes narrative through putting together fragments from disparate sources, and things only cohere in the spectator’s mind in the moment of viewing, reading. It is in Tuning Time 34 the huge installation made in-situ in the gallery, that her words are pictured. It takes up the whole wall. Welcome Visitors!, screened in the room nearby, makes Skokiaan the sound to see it by.

Tuning Time is a collage of ‘splashes’ of ink and glue on paper of varying sizes, cut-outs from newspaper headlines, small sketches and found objects. The medium of glue and ink becomes an image through a chemical reaction, where the white glue mixes with the pigment. It becomes transparent through the drying effects of the air. Gravity pulls it into shape. Setting the conditions for something to happen on a horizontal plane, the materials react to eachotherimprovisation takes over.

Welcome Visitors! single-channel video, sound 10 min 17 sec 2017 21

Tuning Time is a collage of ‘splashes’ of ink and glue on paper of varying sizes, cut-outs from newspaper headlines, small sketches and found objects. The medium of glue and ink becomes an image through a chemical reaction, where the white glue mixes with the pigment. It becomes transparent through the drying effects of the air. Gravity pulls it into shape. Setting the conditions for something to happen on a horizontal plane, the materials react to each other - improvisation takes over. 35

Some newspaper cut-outs are encased in the viscous surface. Others roam free on the wall. Some phrases are illegible, others not. Some fuse with images; lines join lines, make circles, crosses. Some of the

time we read what isn’t there because we know the source – the newspapers. Many are large headlines, sourced from the newspaper sellers outside the gallery, the posters on the street. Public history, as it happens. Cut, letter by letter, from the printed page, they make Vera’s words physical – her lines on Skokiaan from The Stone Virgins. This is where the visual mass on the wall becomes more legible, transforming into single lines, single sentences that curve into one another on its edges.

There are objects too. Some sit on white shelves. Others rest on sculpture plinths. Still others are nailed directly into the wall. Most are found in Bulawayo, in thrift stores or in the souvenir shop down

the road. Many are copper, ornaments from another time.

On the other side of the gallery are the small paintings. Their ground is a membranous glue surface with oil paint on top. It is ideal for sgraffito, 36 scratching through a layer to reveal its underneath. Sgraffito is the earliest form of drawing and writing, those engravings found in caves where pigment rubbed in so long ago still stains the stone.

I think of Vera’s words about her childhood memory of scratching into her skin, writing, drawing; the time she ‘discovered the magic’ of her body ‘as a writing surface’.

She writes:

The skin over my legs would be dry, taut, even heavy. It carried the cold of our winter. Using the edges of my fingernails or pieces of dry grass broken from my grandmother’s broom I would start to write on my legs. I would write on my small thighs but this surface was soft and the words would vanish and the words would not stay long, but it felt different to write there, a sharp and ticklish sensation which made us laugh as though we had placed the words in a hidden place. 37

This seems more like bleeding, not writing. It was important to write.

23

Breathless and Blue

Series of 12 paintings

Ink, glue and oil on canvas

2019

The little paintings suggest scenes, but things are not clear. The surfaces are too physical and their crustiness catches too much light. Strange. Something seems buried in them, but also exposed. Is that a hole in the ground, or a hole in the paint skin? Is that someone in the hole? Or a stone. Is that orange fire? An insect burning? A swollen blue form looks like water. But it’s too solid, too hot to be sea. It bleeds out of the picture plane, loses its rectangle.

What more can I say? People asked if I was making a political statement in the installation, by using newspapers. And all that red ink and visceral glue.

I recall reading somewhere how Vera thought that sometimes you cannot escape the times you are living in.

Vera again,

People forget that writing is not just about issues [ ... ]

My first commitment is to the act of writing. [ ... ]

I always feel, with each paragraph I write, I have to be at a new threshold [ ... ] Paragraph by paragraph, I feel transformed. And I always feel at the end of the day, when I manage to write, I panic, my heart beats, and I think, if l had not written today, I would not be where I am right now, right now, this moment. But people don’t know that, you know. They just read, sometimes, and they just know the theme, they think everything is [decided] in advance, you know, of the act [of writing] ... But it isn’t. 38

25

DIALOGUES WITH PENNY SIOPIS AND CHARMED OBJECTS

TAFADZWA GWETAI ARTIST / WRITER

It was a gathering of artistic energies from all over Zimbabwe to engage in dialogue with world renowned artist from South Africa, Penny Siopis. An Honorary Professor at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town, she is represented in South Africa by Stevenson Gallery. The time: Wednesday, 12 June to Friday, 14 June 2019. The place: The National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo.

Penny Siopis is a painter, video and installation artist. Her creations are highly conceptual and have layers upon layers of meaning. Watching the exhibition Moving Stories and Travelling Rhythms come together allowed for a dialogue with Penny that allowed insight into her thinking and creative process. At the same time the dialogues revealed truths about each of our art practices. As artists we are often caught up in the curatorial demands where we mainly focus on the concept of the artwork. In the dialogues with Penny, we focused on the creative process and its significance to our final product. Penny finds a way to transform the creative process as an art form in itself. This gave the invited artists a chance for introspection; an opportunity to reflect on how and why and where they created their work.

Penny’s creations explore key questions of the human condition as she carefully weaves the relationship between living and inanimate objects. She explores this through issues of memory, imagination, migration and spirituality. Her objects are carefully selected to create her installations. She describes these objects as being “charmed” or as objects that are charged with an energy - an energy that is present via the former owner, or an energy that is bestowed by the artist.

Workshop

Workshop

27

Artists from Harare and Bulawayo 2019

Penny’s dialogue led us on a journey that was filled with the music and literature that brought her to Zimbabwe and Bulawayo. It was the story of ‘Skokiaan’, the famous musical piece composed by August Musarurwa in the nineteen forties, which was also a local illegal alcoholic brew. ‘Skokiaan’ found its way to America and inspired Louis Armstrong, who visited Zimbabwe to share his love for the music.

That special ability of artists to give meaning and purpose to objects was the core aspect of our workshop that Penny supervised. We were given a limited and selected amount of materials to experiment with. As artists we took to the challenge with no fear and tonnes of curiosity. New forms were born with new meanings for our eyes and minds. We worked with man made objects, repurposed objects, that, as Penny would say, ‘became charmed and charged with a certain power’.

I was fascinated by her reference to these random objects as being ‘charmed’, 39 to have a hidden strength or potential energy. In our artistic agenda with Penny the charmed potential has a magical quality to it. A magic that is within the identified object and how we redefine this object’s purpose. Other definitions of the meaning ‘charmed’ extends into the quality of ‘luck’ or ‘good fortune’ being bestowed upon an inanimate object.

Our (artists) ability to assign meaning to the ‘charmed’ object allows for the birth of new layers of debate and dialogue. What is necessarily a group of unrelated objects such as European or African objects could find themselves juxtaposed together to spark thought or to deliberately antagonise. An object comes with charm that has historical meaning that may have its own colonial baggage, or an object that could be charmed by virtue of its former spiritual purpose.

The found objects we use as artists in our work, have travelled great distances just like the music of ‘Skokiaan’. Penny’s video montages are an accumulation of objects from the past, rejected things, forgotten memories, familiar tunes, hard and good times. The fluid and spiritual nature of music as an art form enabled the Bulawayo ‘Skokiaan’ narrative to travel as far as America and was able to ignite artistic partnership and friendships. This abstract quality flows into into Penny’s accompanying ink drawings, works that possessing a spiritual energy that appears intangible, similar to the music of ‘Skokiaan’. These drawings with collaged text have a natural flow, ‘charmed’ by the creator. This is where one gets to realise the extent, to which Penny immerses herself in the process and the process in turn becomes part of the artwork.

The culmination of the workshop that took place between 12-14 June, 2019, was the exhibition of the works made by the participants. Installed in the adjacent rooms of the National Gallery, the exhibition was open to the public alongside Siopis’ solo show.

Open Studio Workshop continued the tradition of workshop as a mode of creative exchange and artistic community building in Zimbabwe since 1988 through the Pachipamwe International Artist Workshops. The second workshop, organised by David Koloane and Chis Ofili among others, was held at Cyrene Mission in 1989. The works in the small exhibition by the participants of the 2019 workshop entered into a conversation with the artworks made in the previous workshops, donated to the National Gallery and installed once again in 2019 to continue the cultural dialogue that filled the rooms of the National Gallery in Bulawayo

31

Artwork by Chris Ofili alongside workshop participants 2019

A special thanks to the fellow artists and participants from Bulawayo as well as Village Unhu and First Floor Gallery in Harare :

Shamilla Asha, George Masarira, Mavis Tauzeni, Talent Kapadza, Amanda Mushate, Charles Bhebe, Wadzanail Tirimboyi, Takunda Regis Billiat, Tafadzwa Gwetai, Olivia Botha, Epheas Maposa, Neville Starling, Berry Bickle and Evans Tinashe Mutenga

THANK YOU TO THE MANY GENEROUS SUPPORTERS OF THE EXHIBITION, WORKSHOP AND PUBLICATION:

33

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE, PENNY SIOPIS, OLGA SPEAKES, HAEFELIS, LUCKYBEAN, NEVILLE STARLING, CLIFORD ZULU, ERICHA GWETAI, JOYCE JENJE MAKWENDA, PAMELA BENTLEY, VALERIE KABOV AND MANY MORE

1 Zimbabwean musician and composer of the 1950s hit tune Skokiaan.

2 Zimbabwean Township Music Documentary 1930s-1960s, produced and directed by Joyce Jenje Madwenda,1992

3 Skokiaan (Chikokiyana in Shona) refers to an illegal self-made alcoholic beverage typically brewed over one day that may contain ingredients such as maize meal, water and yeast, to speed up the fermentation process

4 Nickname for American musician Louis Armstrong

5 Open call for local and visiting artists and curators wishing to present new ideas and projects in the context of the Bulawayo gallery space and emerging independent curators committed to developing their professional practice to submit proposals for exhibitions

6 Building in Bulawayo known for cultural significance and place of congregation for its people, a significant location during the liberation struggle.

7 As part of Penny Siopis’ residency, she welcomed artists from the capital Harare to join Bulawayo artists for the workshop that precluded the exhibition.

8 University of Witwaterstrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

9 The crime of a mother killing her child within the first year of birth

10 Penny Siopis, Welcome Visitors!, Single channel digital video, sound, 10mins, 17secs, 2017.

11 Interview: Vera Yvonne by Jane Bryce, 1st August 2000, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe published in Sign and Taboo, Weaver Press, Harare, 2002.

12 Terence Ranger in Petal Thoughts, Mambo Publishers, Gweru, Zimbabwe, 2008 p 90

13 Yvonne Vera, ButterflyBurning, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 2000. p 10 -11

14 Yvonne Vera, StoneVirgins, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004, p7.

15 Yvonne Vera, StoneVirgins, Weaver, 2002.

16 Yvonne Vera, StoneVirgins, Weaver, 2002. p 7

17 Yvonne Vera, StoneVirgins, Weaver, 2002. p8-9

18 Ann Elizabeth Willey, Engendering modern spaces: female voices, male nationalisms, and cosmopolitan counter-modernity in Yvonne Vera’s The Stone Virgins, Journal of the African Literature Association, 2016.

19 Nickname for musician Louis Armstrong

20 Yvonne Vera, ButterflyBurning, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 2000. p

21 Ericha Gwetai, Petal Thoughts, Mambo Publishers, Gweru, Zimbabwe, 2008. p74

22 Yvonne Vera, Dead Swimmers in Gods and Soldiers: The Penguin Anthology of Contemporary African Writing,ed Rob Spillman, Penguin, 2009.

23 Penny Siopis in conversation with Ericha Gwetai, 11 June 2019.

24 Ericha Gwetai, Petal Thoughts, Mambo Publishers, Gweru, Zimbabwe, 2008.

25 Penny Siopis in conversation with Ericha Gwetai, 11 June 2019.

26 Penny Siopis in conversation with Ericha Gwetai, 11 June 2019.

27 Vera , Yvonne, Sorting It Out, WorldView Fall, 1999, 47 – 49

28 Louis Armstrong and his band embarked on their second tour of Africa in 1960, including Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

29 Vera’s Van Gogh reference

30 Prospect 4, Lotus in Spite of the Swamp, New Orleans, 2017.

31 Curator of Prospect 4, 2017 - Trevor Schoonmaker

32 Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club (founded in 1916) - a fraternal organisation in New Orleans, Louisiana which puts on the Zulu parade each year during Mardi Gras. The club is a regular feature of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival

33 Tsaba-tsaba jive : A style of dance music popular in the 1940s, combining traditional African melody and rhythm, particularly those of focho, with jazz and Latin-American dance rhythms.

34 Penny Siopis, Tuning Time, mixed media site-specific installation, 2019.

35 Penny Siopis, Material Acts, Stevenson, 2018.

36 Sgraffito: (Italian: “scratched”), in the visual arts, a technique used in painting, pottery, and glass, which consists of putting down a preliminary surface, covering it with another, and then scratching the superficial layer in such a way that the pattern or shape that emerges is of the lower colour.

37 Yvonne Vera, StoneVirgins, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004, p59.

38 ThePlaceoftheWomanisthePlaceoftheImagination. Yvonne Vera inter viewed by Ranka Primorac, SAGE Publications, Vol 39(3), 2004. P 165

39 Penny Siopis, Gerrit Olivier, Installation and Collection, in Time and Again, 014. p109-126

40 Village Unhu : A profiect space cultivating a community of artists in Harare, Zimbabwe

41 First Floor Gallery : independent artist-led gallery in Harare founded in 2009 dedicated to supporting international career development of the emerging generation of contemporary Zimbabwean artists.

Notes

THANK YOU TO NEVILLE STARLING AND TAFADZWA GWETAI FOR MANY OF THE PHOTOGRAPHS IN THIS PUBLICATION

35

National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo

BUTHOLEZWE KGOSI NYATHI DIRECTOR NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo

BUTHOLEZWE KGOSI NYATHI DIRECTOR NATIONAL GALLERY OF ZIMBABWE IN BULAWAYO

Workshop

Workshop