In

Founded in 1993 by Dr. Susan Weber, Bard Graduate Center (BGC) is a research institute in New York City dedicated to studying the human past through objects, from those created for obvious aesthetic value to ordinary things that are part of everyday life. It grants MAs and PhDs in the field of decorative arts, design history, and material culture. Its academic programs, gallery exhibitions, research initiatives, publications, and events explore new ways of thinking about the decorative arts. A member of the Association of Research Institutes in Art History, BGC is an academic unit of Bard College. bgc.bard.edu

Michele Beiny-Harkins, Vice-Chair for Nominations Nicolas Cattelain Brandy S. Culp, Secretary Hélène David-Weill Nancy Druckman, Chair Philip D. English Holly Hotchner Fernanda Kellogg

Dr. Arnold L. Lehman Martin Levy David Mann

Dr. Caryl McFarlane Dr. Steven Nelson Jennifer Olshin

Melinda Florian Papp

Lisa Podos

Ann Pyne Linda Roth

Sir Paul Ruddock

Gregory Soros Luke Syson

Dr. Charlotte Vignon

Shelby White

Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Philip L. Yang, Jr.

Dr. Susan Weber, ex-officio

Dr. Leon Botstein, ex-officio

Dr. Christian Ayne Crouch, ex-officio

TBD Director’s Welcome

TBD Dean’s Introduction

TBD Projects

TBD Cultures of Conservation

TBD Conserving Active Matter

TBD

Richard Tuttle: What Is the Object?

TBD Playing an Active Part in Conserving Active Matter

This is a hopeful moment when it seems perhaps the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic may be behind us. Flowers are blooming and trees are in leaf all over the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where Bard Graduate Center makes its home. For the first time since 2019, our MA students are preparing to travel to Paris for a ten-day study course, led by professor Jeffrey Collins and organized as part of an ongoing exchange with the École du Louvre. This will be followed by a two-week archaeological field trip to Greece led by professor Caspar Meyer.

As sad as we were that the 2020–21 academic year had to take place almost entirely online, it taught us a great deal about our capacity for adaptability and resilience. We have put those lessons into productive use in 2021–22, incorporating digital tools to make BGC research and exhibition experiences available all over the world.

I want to offer special recognition to BGC students who demonstrated an impressive ability to thrive under the difficult circumstances of the pandemic: launching new ways of presenting their research online; producing videos of fascinating object biographies; leading virtual and in-person tours of our critically acclaimed exhibitions; participating in conversations and trainings about racial justice, diversity, equity, access, and inclusion (DEAI) across our fields of study; and giving essential feedback for our new course, “Unsettling Things: Expanding Conversations in Studies of the Material World.” I’m very proud of their achievements. I’m also thankful to the generous donors whose ongoing support allowed us to offer PhD candidates an additional year of funding to complete their dissertations after their research was delayed during Covid.

The BGC faculty adapted and rose beautifully to the challenges of the past two years: teaching and speaking at conferences on Zoom, planning exhibitions and completing publications, launching new courses and online initiatives, bringing diverse voices and research into their work, and continuing to nurture the sense of community that students tell us makes this place so special.

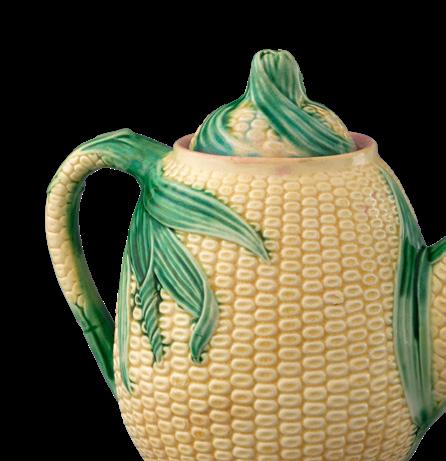

On a personal note, BGC curators Earl Martin and Laura Microulis, many other staff members, and I devoted years of work to the exhibition Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915. Postponed twice because of Covid, it was wonderful to see it reopen the BGC Gallery in fall 2021. I’m also very proud that the accompanying three-volume catalogue was awarded the 2021 Historians of British Art Book Prize for an outstanding multi-authored book on the history of British art, architecture, and visual culture. The exhibition has continuing impact with installations at the Walters Art Museum, March 13–August 7, 2022, and the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stokeon-Trent, England, where so many of the objects in the exhibition were created, October 8, 2022–January 29, 2023.

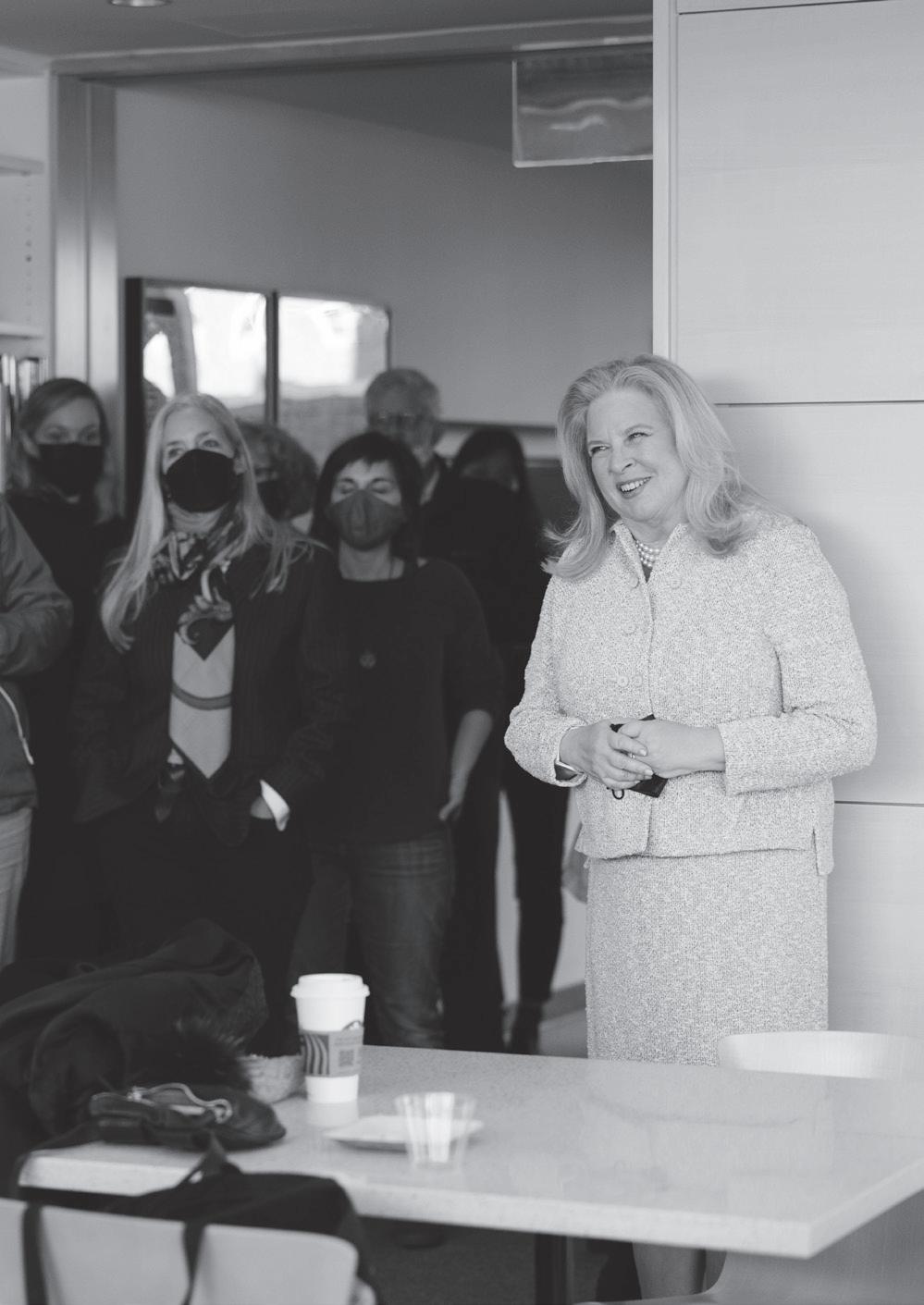

Susan Weber. Photo by Da Ping Luo. Director’sTwo excellent exhibitions opened in the BGC Gallery in February: Conserving Active Matter and Richard Tuttle: What Is the Object? Conserving Active Matter and its corresponding publication and events represent the culmination of BGC’s ten-year project Cultures of Conservation, which was made possible by the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Richard Tuttle: What Is the Object?, encourages visitors to pick up, hold, and interact with the objects Tuttle has collected over five decades. We are honored that many of these objects will become a permanent part of the BGC Study Collection where they will provide opportunities for examination and research by generations of future students.

BGC owes a debt to its alumni, who reached out in the summer of 2020 to urge us to do more and move quickly on DEAI initiatives. Although there is much more work to do, we are making progress. Since 2021, Dean Miller and I have been meeting regularly with BGC alumni who have shared their wisdom and experience in curation and exhibition-making with us. They have also offered career advice to graduating students. Seemingly every week, I learn of a significant award won, position landed, publication or paper written, exhibition curated, or another entrepreneurial or creative project undertaken by a BGC alum. That alumni continue to care deeply for BGC and its current students even as they achieve such remarkable professional success fills me with pride and gratitude.

With luck the 2022–23 academic year will take place entirely in person. I want to thank BGC students, faculty, and staff for surmounting the difficulties of the past two years. Together we will meet whatever challenges the new academic year may bring and continue BGC’s essential work of exploring new ways of thinking about decorative arts, design history, and material culture.

Susan Weber Founder and Director

Susan Weber Founder and Director

People often ask me, “what’s next at BGC?” This question always reminds me of the glorious medal designed by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) with his image and motto: Quid tum What then? Or, as it’s often translated, what next?

Over the past two years, we have made visible and some less visible steps toward the future. We have brought our decade-long Andrew W. Mellon Foundationsponsored Cultures of Conservation initiative to a resounding conclusion with the exhibition Conserving Active Matter, the two-day conference Conservation Thinking in Japan and India, and a second MacArthur x BGC series, What Is Conservation? We created a new seminar, Art and Material Culture of Africa and the African Diaspora, and a new post-doctoral fellowship in the arts of Africa with the Brooklyn Museum. We re-launched our public events in the second year of the pandemic, emphasizing week-long residencies to make the most of our time with visiting speakers. And, like so many institutions, we dramatically augmented our digital offerings, infrastructure, and aspirations.

The changes to the institutional structures supporting this work were less visible. In 2021 we created the Department of Research Collections to unify BGC’s book, object, digital, and archival holdings. This was undertaken with an eye to the steady expansion of the study collection and the institutional archive. This reorganization will facilitate access to an innovative digital recuration of past and newly archived BGC exhibitions. Few activities are more future-oriented than creating an institutional archive, only superficially about the past. In 2022 we initiated Public Humanities + Research, or PH+R, to bring together all BGC events in a more efficient delivery system and align our entire output of programs with the institution’s mission to do research at every level and present it at every turn. PH+R will reach into the classroom, too, training our students to develop events and serving as a test bed to build upcoming BGC programming, whether for the gallery or the lecture hall.

What we have not yet gotten to—the real Quid tum— is the next step towards consciously integrating the various things we do into a more project-based approach. We already run multi-year research projects; we call them exhibitions. We have worked to integrate them more fully from start to finish into the academic program. However, what if we planned the academic program around these projects and others we took on? What if we accepted doctoral students who wanted to work on them? What if we thematically planned publishing and public events around them? The answer is that we would be unlike any other North American graduate research institute—and exactly like the European Research Council’s grantees. Maybe that’s too big a stretch for right now. The advantage of this exercise in thinking is to reveal how close we are to that unique situation.

need Peter’s signature

Peter N. Miller Dean and Professor

The Cultures of Conservation initiative, a ten-year project generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, modeled new approaches to integrate the insights of objects conservation and materials science with those of the human sciences (anthropology, archaeology, art history, history). It brought Bard Graduate Center’s cross-disciplinary perspective on objects into conversation with conservators’ study of materials, techniques of making, and practices of use and re-use, as well as scholarly studies of materials and materiality. It further explored the meaning of active matter for the field of conservation through the lenses of materials science, history, philosophy, and Indigenous ontologies that never assumed matter was inactive.

As part of the Cultures of Conservation project, BGC offered students new courses devoted to conservation perspectives, augmented existing courses to link the study of materiality directly to conservation, and created a new faculty position dedicated to teaching conservation science. These changes transformed BGC’s curriculum and provided a model of how other higher education institutions might do the same.

Over ten years, Cultures of Conservation supported the publication of five books; the creation of three exhibitions; the appointment of six research fellows, one visiting professor, and one full professor; the development of nineteen new courses; the presentations of thirty-nine guest speakers in thirty-four BGC courses and 145 scholars at fifty-two events; and the evolution of a local steering committee of New Yorkarea conservators and professors that met annually to review progress towards the project’s goals and consider new possibilities of inquiry.

The project culminated with the exhibition Conserving Active Matter, a book of the same title, and a range of events. Information about these concluding activities is given on the next page.

Conserving Active Matter and Richard Tuttle: What Is the Object? are Focus Exhibitions. Bard Graduate Center faculty members and postdoctoral fellows propose and lead these projects in collaboration with interested students. Each exhibition originates with faculty research and is developed through seminars, workshops, and “In Focus” courses that proceed from broad issues of conception and definition through the specific challenges of selection, layout, and interpretation in two and three dimensions. Students are involved from genesis through execution and contribute substantively to each project’s form and content.

March 25–July 10, 2022

Curated by Soon Kai Poh and Peter N. Miller

Conserving Active Matter is part of Cultures of Conservation, a multi-year initiative generously supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. More information about the initiative can be found at bgc.bard.edu/cultures-of-conservation. The exhibition and publication are generously supported by donors to Bard Graduate Center.

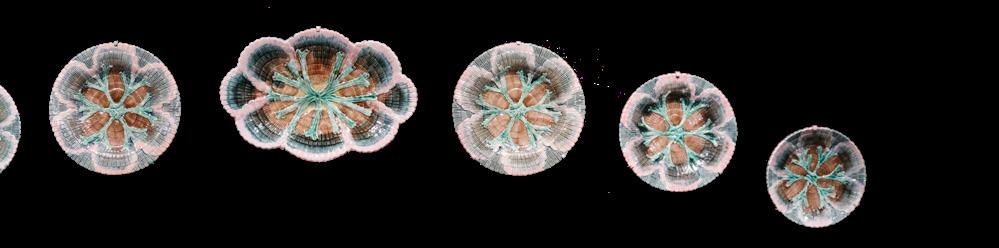

Conserving Active Matter has occupied the first two floors of the Bard Graduate Center Gallery this spring and summer, where it presents conservation as a form of inquiry in four parts: What is conservation? How is matter active? Who acts on matter, when, and why? And where is the future of conservation? The exhibition explores the activity of matter through items that span five continents and range in time from the Paleolithic to the present. The exhibition’s online companion site mirrors its organizing questions and allows visitors to engage indefinitely with the research on which the exhibition was built.

A book, also titled Conserving Active Matter, draws together the main lines and interim conclusions of Cultures of Conservation’s effort to reimagine the relationship between conservation knowledge and the humanistic study of the material world. A wide range of events have been programmed to deepen our engagement with the exhibition’s foundational questions, including film screenings; conversations with artists, scientists, and humanists about conservation; repair days; a discussion about the preservation and exhibition of human remains; and a two-day symposium focused on conservation practices in India and Japan.

March 25–July 10, 2022

Curated by Richard Tuttle and Peter N. Miller

Curated by Richard Tuttle and Peter N. Miller

Many objects in Richard Tuttle’s collection will be donated to Bard Graduate Center. They will form the “Richard Tuttle Study Collection” to be used for teaching and exploration by students, faculty, and staff.

Support for Richard Tuttle: What Is the Object? was generously provided by Agnes Gund with additional support from David Kordansky Gallery, Scully Peretsman Foundation, and Peter Freeman and Lluïsa Sàrries Zgonc, as well as donors to Bard Graduate Center.

Support for the publication was provided by pacegallery.com

Bard Graduate Center Gallery has paired Conserving Active Matter with Richard Tuttle: What Is the Object?, an exhibition of seventyfive objects from the contemporary artist’s personal collection along with a series of nine of his new works that are on view for the first time. Tuttle, along with his co-curator and Bard Graduate Center Dean Peter N. Miller, invites visitors to a multi-sensory engagement with Tuttle’s objects that provides a rare glimpse into the relationship between an artist’s collection and his work. An index card created by Tuttle accompanies each object and outlines his original encounter with it, how it entered his collection, and his thoughts about it. Tuttle invites visitors to reflect on the question, What is the object?, by looking closely at the items in the exhibition, exploring them through touch, and viewing them from all sides; by imagining their origins, how they were designed and crafted, and how they were intended to be used; and by thinking about what they mean and how that meaning is assigned. Tuttle’s exploration extends to the exhibition furniture he designed, which resembles sculptures he has made throughout his career and provokes the questions, Is this furniture the object? Or are objects limited to those things that rest upon it? The result is an exhibition that Will Heinrich of the New York Times called “an expansion of Tuttle’s longstanding practice of juxtaposing incongruous elements in a way that highlights the precariousness of beauty and meaning.”

Belgian book artist Luc Derycke designed the catalogue, a ‘book as object’ that further explores the meaning of objects. The volume was edited by Peter N. Miller and includes his essay about Tuttle’s art as the pursuit of a kind of philosophical exploration, an interview with Tuttle, and an analysis of objects in poetic non-fiction by Renée Gladman, as well as poems and a short surrealist tale by Tuttle about his objects. Bruce M. White’s beautiful photographs of Tuttle’s collection and its accompanying index cards illustrate the catalogue.

The exhibition inspired an online companion site and a wide range of events, including a discussion on the power of puppetry with theater artist and puppeteer Lake Simons, punctuated by short puppet performances that made use of objects in the exhibition; a reading group led by poet Anselm Berrigan with texts chosen to inspire participants to reflect on their relationships to objects; a symposium featuring Claudia Rankine, Ann-Sophie Lehmann, Tomashi Jackson, K. Anthony Jones, and Francey Russell; and tours led by the artist and verbal description tours for people with low vision and blindness.

This past March, I attended the opening of Conserving Active Matter, Bard Graduate Center’s exhibition exploring the activity of matter and a variety of human responses to it. Walking through the galleries, I passed by familiar acquaintances: there was the ibis mummy, the shattered silk dress, the marble Ganesh, and Vladimir Nabokov’s annotated copy of The Metamorphosis. Having taken the first of two “In Focus” courses related to the exhibition, seeing these items together and in-person for the first time was especially rewarding. I knew how much thought had gone into their presentation as this was the culmination of work the curators, designers, my classmates, and I had done over the past year.

I signed up for the “Conserving Active Matter” class in the latter half of my first year as an MA student (spring 2021), eager to take a course in which I’d be able to actively participate in mounting an exhibition for the BGC Gallery. Taught by the exhibition’s curators, Soon Kai Poh and Dean Peter N. Miller, the course began with expansive discussions of conservation that touched on everyday repairs, Indigenous ontologies, connoisseurship versus scientific analysis, and appreciation for the aesthetics of decay. Conversations around these topics had taken place throughout BGC’s ten-year-long initiative, Cultures of Conservation, and led to the development of questions around which the exhibition is organized: What is conservation? How is matter active? Who acts on matter, when, and why? Where is the future of conservation?

In February, each member of the class chose four objects from the exhibition checklist for which to write labels and catalogue essays.

From the items included in the “What is conservation?” gallery, I chose a piece of contemporary art the BGC had commissioned from Mark Dion for the lobby of 38 West 86th Street: The Conservator’s Cupboard. As a fan of Dion’s work, I looked forward to learning how this large cupboard crammed with instruments and materials spoke to the themes of our exhibition. From the “How is matter active?” section, I selected a faux tortoiseshell vanity set— an example of deteriorating, early twentieth-century plastic— with the intention of examining its activity from a scientific and aesthetic point of view. From the “Who acts on matter?” gallery, I chose a marble figure of Ganesh from India, partly because I’d developed an affinity for the Hindu deity when I was a child and because I wanted to explore how the statue could be activated by worshipers or museum visitors. Lastly, for “Where is the future of conservation?,” I selected a biodegradable collar made by contemporary designer Aniela Hoitink for its connection to cultural and environmental conservation issues.

For the next several months, I researched these items, gaining valuable insights from makers, curators, and conservators. I chatted with Dion about how his early career as an art restorer informed the objects he included in The Conservator’s Cupboard and his willingness to accept a certain amount of activity in the piece; I consulted American Museum of Natural History curator Laurel Kendall and accession documents from the museum’s digital archives on the figure of Ganesh; and I interviewed Cooper Hewitt conservator Jessica Walthew about her work on early plastics. These conversations were fundamental to writing the labels and catalogue essays.

As I walked through the exhibition, I noted transparent room dividers, objects suspended from the ceiling, the different colors of each room (deep blue, white, grey, light green), and I recalled the inspiring conversations my classmates and I had with David Harvey, the exhibition’s designer, who encouraged us to think about the physical space of the gallery, how to guide the visitor’s perception and path, and how to tell a story through visual design. To evoke the feel of an exhibition, Harvey creates mood boards. He asked the

class to do the same for Conserving Active Matter and visualize each of the exhibition’s themes. This highly enjoyable assignment engaged our creative brains, and, gratifyingly, these digital collages now flash across screens installed in each of the galleries.

Wanting to stay connected to the project after the class ended, I applied for a digital fellowship through which I could help construct the show’s companion website. In doing so, I got a behindthe-scenes look at how director of digital humanities and digital exhibitions Jesse Merandy and art director Laura Grey designed the site to visually align with the physical exhibition and added supplemental features including a clickable checklist that sorts items by their material and place of origin, essays written by conservation scholars and BGC faculty, and audio clips of students’ interviews with conservators. The digital exhibition in itself can be seen as a form of conservation in that it will preserve the show online, making it accessible to the public long after it closes.

Through participating in various aspects of the show, I gained a better understanding and appreciation of its many moving parts. I’m thankful to have had the opportunity to receive such a multi-faceted introduction to the exhibition-making process; it has certainly activated my interest in this kind of work.

September 24, 2021–January 2, 2022

Curated by Susan Weber, Founder and Director, Bard Graduate Center, and Jo Briggs, Jennie Walters Delano Associate Curator of 18th- and 19th-Century Art, Walters Art Museum Project Directors: Earl Martin and Laura Microulis

Special thanks to the Majolica International Society

Support for the Majolica Mania website was generously provided by Joseph Piropato and the Lee B. Anderson Memorial Foundation, with special thanks to Ann Pyne and the Sherrill Foundation.

Majolica, the popular nineteenth-century pottery, provided the subject for Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915 Graduate Center’s largest exhibition to date, as well as a catalogue and a book of and a host of virtual events. The project represented the culmination of a multi-year international research project that continued BGC’s tradition of identifying underrecognized and undervalued areas of scholarship in nineteenth-century decorative arts.

The exhibition presented more than 350 objects drawn from major private collections in the United States and leading public collections in the U.S. and England, including the Maryland Historical Society, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Royal Collection, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Barrymore Laurence Scherer’s review in the Wall Street Journal called Majolica Mania “a joyous show [that is] so engaging and so memorable.” The exhibition continues to attract visitors from all over the world with additional stops in Baltimore at the Walters Art Museum, which organized the exhibition with BGC, and in Stoke-on-Trent, England, at the Potteries Museum.

The Majolica Mania catalogue won the 2021 Historians of British Art (HBA) Book Prize for an outstanding multi-authored book on the history of British art, architecture, and visual culture. According to the HBA announcement,

“the three lavishly illustrated volumes of Majolica Mania offer a visual fantasia that is as fascinating and comprehensive as its scholarship. … Majolica’s historiography, design, production, uses (from architectural decoration and sculpture to hygienic dishware), iconographies, relationship to design reform, promotion through exhibitions, and more are explored in this major research undertaking, which definitively establishes the importance of these ceramics for our understanding of nineteenth-century culture, and offers serious delight while doing so.”

the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society of America. One of the site’s most advanced features presents virtual recreations of objects in the exhibition using a process called photogrammetry, in which thousands of photographs of one object are digitally “stitched together” to create a three-dimensional, virtual model that can be manipulated by viewers on their computers, as if they were picking the object up, holding it, and rotating it to view it from different perspectives.

Events included an online symposium that explored the influence of French artists on English majolica; a lecture delivered to the Potteries of Trenton Society; discussions of representations of race in majolica; the chemical properties of its rich, saturated hues; and an exploration of the hazards of working with lead-based glazes, one of the factors in the decline of majolica’s popularity.

Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915 was made possible by Deborah and Philip English, the Bernard Malberg Charitable Trust, the Abra and Jim Wilkin Fund, and the Gary Vikan Exhibition Fund, with the generous support of Marilyn and Edward Flower, Amy Cole Griffin, Darci and Randy Iola, James and Carol Harkess, Maryanne H. Leckie, the Lee B. Anderson Memorial Foundation, the Thomas B. and Elizabeth M. Sheridan Foundation, Inc., the Robert Lehman Foundation, and the Women’s Committee of the Walters Art Museum, with additional support by Carolyn and Mark Brownawell, the Hilde Voss Eliasberg Fund for Exhibitions, Joseph Piropato, Ann Pyne, Lynn and Phil Rauch, George and Jennifer Reynolds, the Sherrill Foundation, Carol and George E. Warner, Michael and Karen Strawser / Strawser Auction Group, Laurie Wirth-Melliand and Richard Melliand, the Dr. Lee MacCormick Edwards Charitable Foundation, Drs. Elke C. and William G. Durden, Joan Stacke Graham, Wanda and Duane Matthes / Antiques from Trilogy, Robin and Andrew Schirrmeister, Karen and Mike Smith, William Blair and Co., and other generous donors to Bard Graduate Center and the Walters Art Museum.

February 29–March 10, 2020, and October 13–28, 2020

Curated by Cloé Pitiot, Curator of Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Contemporary Design at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Organized by Centre Pompidou, Paris, in collaboration with Bard Graduate Center

Project Directors: Cloé Pitiot and Nina Stritzler-Levine Curatorial

Assistant: Emma Cormack

Support for Eileen Gray was generously provided by Phillips with additional support from the Lily Auchincloss Foundation, the Selz Foundation, Edward Lee Cave, and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. The exhibition was supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

The exhibition was made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Support for the exhibition catalogue was provided by Elise Jaffe + Jeffrey Brown and Furthermore: a program of the J.M. Kaplan Fund. Special thanks to the National Museum of Ireland.

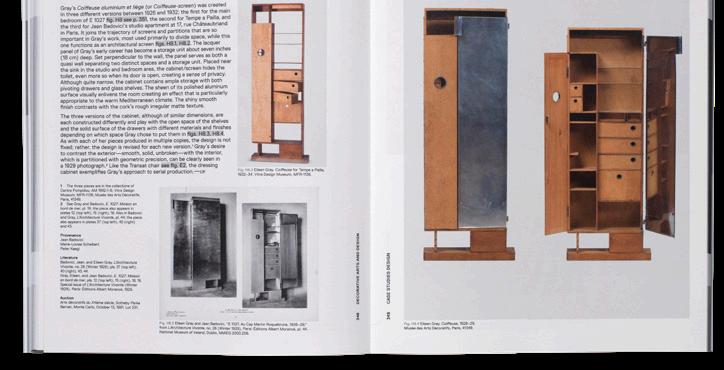

The abrupt closing of the Eileen Gray exhibition due to the Covid-19 pandemic spurred Bard Graduate Center’s Nina Stritzler-Levine, Emma Cormack, and Jesse Merandy to quickly create an online exhibition that included a video tour of the galleries led by Rachael Schwabe (MA ‘20), a flipbook of Eileen Gray’s portfolio, installation photography, texts from the exhibition catalogue and gallery interpretation, in-gallery interactives, digital media, materials for educators including content developed by BGC MA and PhD students, and many other innovative features.

The site preserves and makes accessible the intellectual and creative labor of curators, researchers, educators, and designers. It constitutes a rich resource for scholars and visitors that will remain on BGC’s website indefinitely. Successfully capturing the essence of the exhibition, the online version also enabled the team to move beyond

what was possible in BGC’s physical gallery space. It continues to serve as a hub and repository for institutional content, creating a vibrant and extended life for the exhibition.

The online exhibition won praise and extensive recognition in the press; attracted tens of thousands of visitors, including all of its overseas lenders; and demonstrated how BGC can serve a much larger audience, including people across the globe and local neighbors with limited mobility. Indeed, with periodic updates publicized through institutional mailings, newsletters, and events, the site has attracted more than seven thousand visitors to date from more than eighty countries to learn about Eileen Gray.

Fortunately, lenders were willing to extend the loan period for the objects in the gallery exhibition, and it was able to reopen for a short time in October 2020 with strict measures in place to protect visitors and Bard Graduate Center faculty, students, and staff from Covid-19. Jason Farago lauded the online exhibition in the New York Times, writing, “I’m impressed with Bard’s conversion of this major show for the web; click on any of the chairs or credenzas in the installation shots, and you’ll discover higher-resolution photographs and thorough contextual materials about her work process and commercial ambitions.” And Martin Filler’s review in the New York Review of Books declared Eileen Gray “a ravishing installation of two hundred objects, many of them great rarities [that] will be long remembered because of its catalogue, admirably edited by Cloé Pitiot and Nina Stritzler-Levine in a tour-de-force of exhaustive research and insightful interpretation.” The publication recently received the Society of Architectural Historians’ 2022 Exhibition Catalogue Award.

In summer 2022, Bard Graduate Center launched its first field school in archaeology and material culture on the Cycladic island of Antiparos. Working across a small channel on the adjacent island of Despotiko, students participated in a project to excavate and rebuild the sixth-century BCE Sanctuary of Apollo using ancient craft ways.

Paros and Antiparos exported marble to centers like Athens— some of the earliest statues from the Acropolis were made of Parian marble—and current work on the site bears directly on our knowledge of the material’s enduring cultural significance. Professor Caspar Meyer, who has been working on the site since 2017, leads the new field school. Since its discovery in the early 2000s, the sanctuary on Despotiko has produced an uninterrupted string of finds, including votive deposits under the temple floor and domestic buildings pre-dating the sacred structures. The site has become key to understanding the connections between seafaring, craft, and religion that shaped Greek culture for centuries.

All first-year BGC students have the opportunity to add the field school to the existing BGC travel program to Berlin and Paris. This year, thirteen students participated in the new program. Professor Meyer and the students first spent two days visiting important ancient sites in Athens and then traveled to Antiparos for six days of work and study. Mornings were devoted to the dig and evenings to discussions led by Professor Meyer.

The purpose of a field school is to take students out of the classroom so they can test what they have learned there against practical, first-hand experiences. Excavation and conversation make powerful teachers.

The Fields of the Future Institute (FFI) is a new initiative at Bard Graduate Center that expands the sources, practices, perspectives, and audiences of interdisciplinary humanities scholarship. It explores how our intellectual landscape should change by posing new questions, suggesting new ways to answer old questions, and bringing new voices into the scholarly conversation. FFI explicitly aims to bring more Black, Indigenous, and people of color into the fields of decorative arts, design history, and material culture and to elevate their voices through fellowship opportunities, a podcast, and a fund to support student and alumni projects that reflect the values of the FFI. In addition, FFI expands BGC’s focus to include summer programs for undergraduate students that offer early career scholars access to graduate-level resources and provide opportunities to gain skills in the public humanities.

In summer 2021, Bard Graduate Center welcomed twelve students from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) for a week-long intensive seminar held on Zoom. This was one of several summer programs organized by the Alliance of Museums and Galleries of HBCUs; others were hosted by the University of Delaware / Winterthur Museum, Yale University, and Princeton University. The course, “Research and Conservation in the Human Sciences,” introduced these students to the role and meaning of humanities-based research. It focused on conservation as a key research tool for working with material culture, integrating research into artistic practices, and research developed in tandem with collecting institutions like the library, archive, and museum. The program introduced students interested in art history, theory, and practice to a range of professional applications for these interests, including graduate-level research. This program will take place every two years.

Bard Graduate Center launched its Undergraduate Summer School in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture in 2021. Open to advanced undergraduates and recent college graduates, the program draws on resources at BGC and around New York City to provide an intensive, two-week program on material culture studies. The topic for 2021 and 2022 was “Re-Dress and Re-Form: Innovations in the History of Fashion and Design, 1850 to Today.”

The course introduced students to the history of design and fashion in the United States and Europe from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day, with a focus on how conceptions of race, gender, and class have shaped the world of goods as we know it. Led by faculty members Michele Majer and Freyja Hartzell in 2021 and by Hartzell and PhD candidate Pierre-Jean Desemerie in 2022, the summer school combined small seminars and behind-the-scenes access to collections. Thirteen students from around the country participated in 2021; twelve students participated in 2022.

In fall 2019, Bard Graduate Center reconceived its research fellowship program to promote work that reflected the values of the FFI. The Fields of the Future fellowships support scholars exploring and expanding the sources, techniques, voices, perspectives, and questions of interdisciplinary humanities scholarship. Fellows receive a monthly stipend, housing in New York City, and a workspace in BGC’s Research Center for a semester. See the list of fellows on pp. xx-xx.

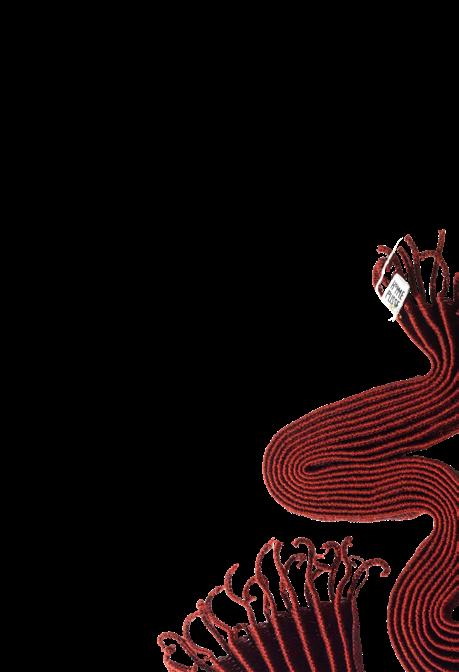

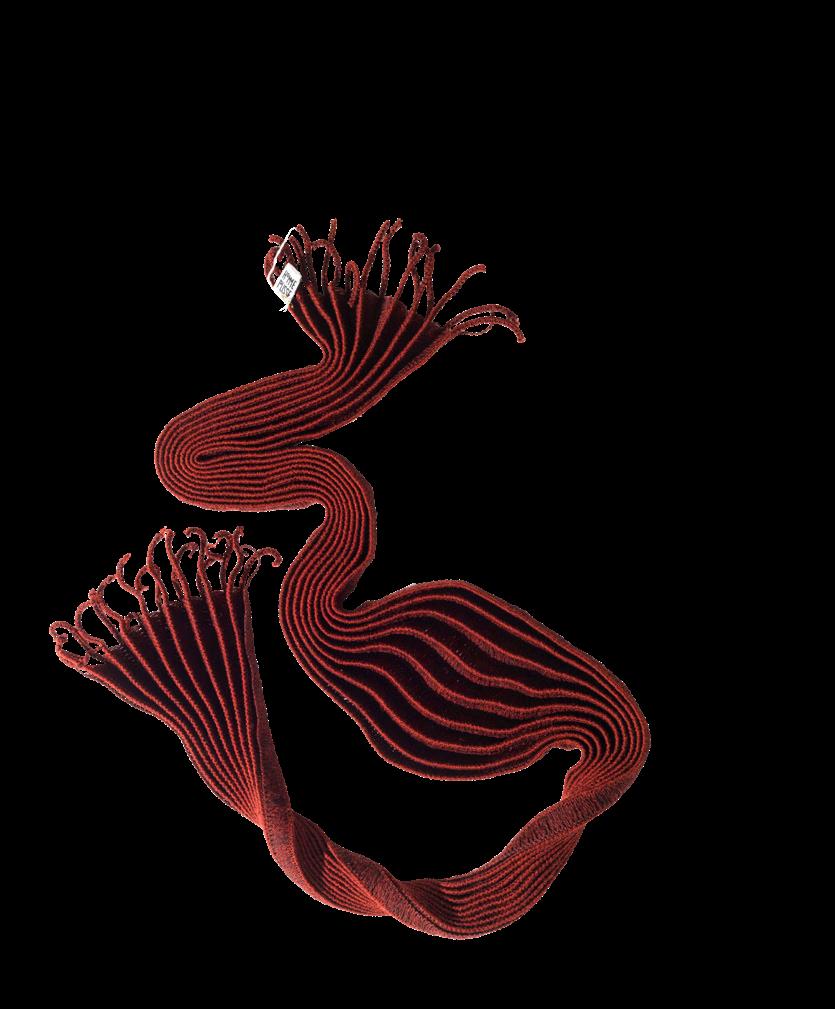

Bard Graduate Center established the Fields of the Future Fund for BGC Students and Alumni in fall 2020. This fund provides financial support for students and alums pursuing projects that bring new voices and narratives into the study of decorative arts, design history, and material culture. In spring 2021, MA student mary adeogun received support from the Fund for a multimedia project that

explored two textiles linked to four sisters, all of Yoruba heritage. Combining photography, video, and brief interviews with each individual, the project tells a story about the sisters’ collaboration and shows the liveliness of their textiles and garments. The Fields of the Future grant helped cover expenses associated with the project’s production, such as renting high-quality camera and audio equipment and hiring a small team. The interviews, photography, and video were created in the summer of 2021. Post-production and editing took place in the fall of 2021. Portions of this project were shared privately with advisors at Bard Graduate Center and with the sisters. In spring 2022, the fund made awards to MA alumna Rachael Schwabe for a project entitled “Crafting Empathy” and to PhD student Kate Sekules for her project, “Repair.”

BGC’s Fields of the Future podcast was conceived to amplify the voices and highlight the work of scholars, artists, and writers injecting new narratives into object-centered thinking. It launched in fall 2021 with a nine-episode season produced by BGC staff members Laura Minsky and Emily Reilly. Each episode brought a BGC fellow or faculty member into conversation with

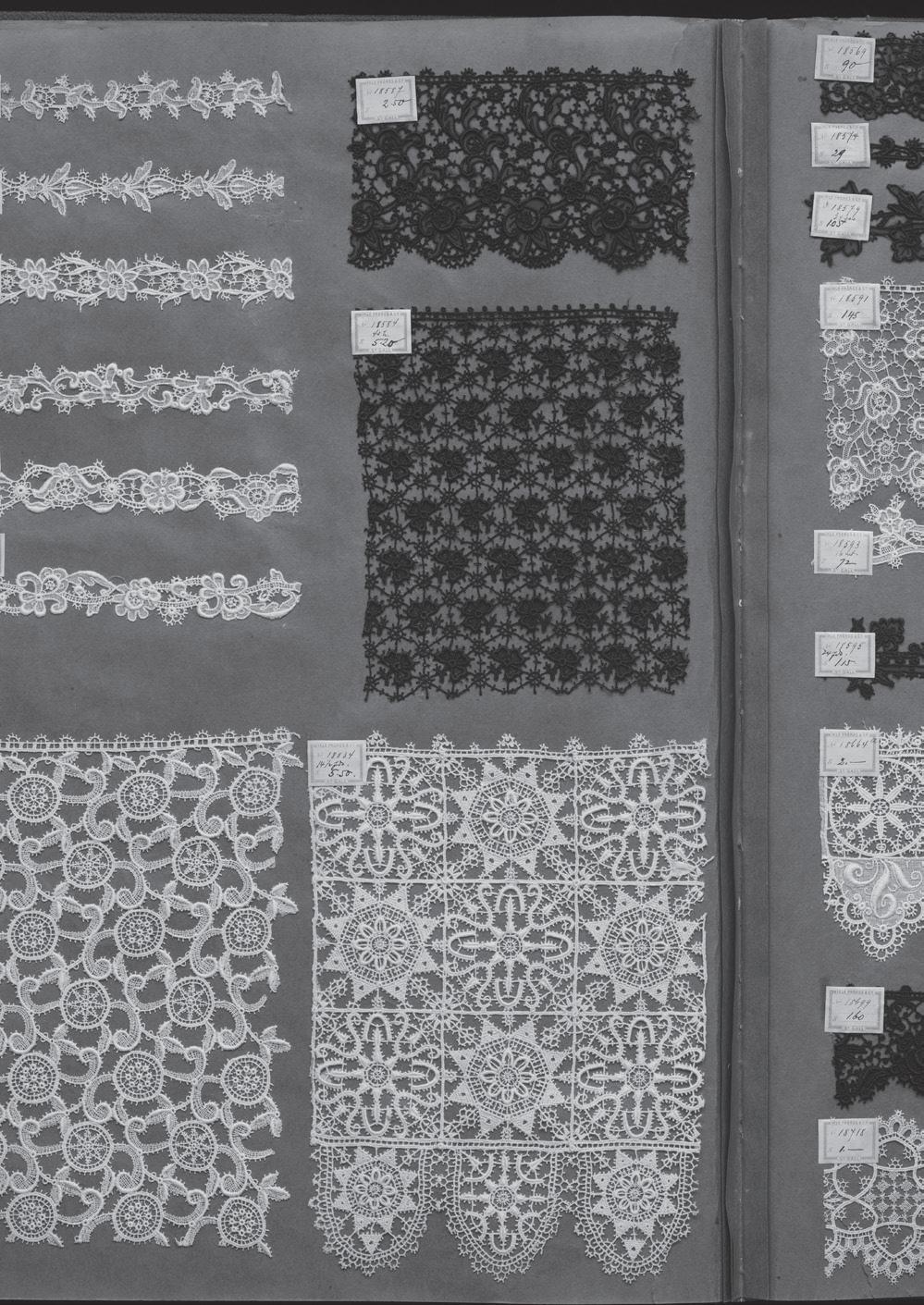

a scholar, artist, or writer of their choosing. Two additional seasons are in production and will be released in fall 2022. The first, produced by BGC alumnae Juliana Fagua Arias and Jessie Mordine Young, includes conversations with Indigenous textile artists and its release will coincide with the launch of the Shaped by the Loom: Weaving Worlds in the American Southwest online exhibition. The second, produced BGC alumna mary adeogun to accompany the exhibition Threads of Power: Lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen, considers lace in Nigerian culture through close examination of a few laces and includes conversations with historians, researchers, dressmakers, lace mills, and fashionistas.

In the summer of 2021, Bard Graduate Center partnered with the Alliance of HBCU Museums and Galleries to offer a one-week course focused on research through objects to undergraduate students and recent graduates of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The course, which was held virtually, centered around presentations from and discussions with a variety of visiting professionals, including conservators, artists, scholars, curators, and archivists. mary adeogun (MA ‘22) and Elizabeth Koehn (MA ‘20, PhD candidate) worked as teaching assistants for the course. In October 2021, they reflected on the curriculum, the students, and their experiences as first-time TAs. A complete version of their discussion appears on the BGC website.

With thanks to the Alliance of HBCU Museums and Galleries, Bard Graduate Center, and each student who participated in the program: Amanei, Barriane, Jade, Janelle, Justin, Kaelin, Kadeer, Kaleizhanae, Meaghan, Shamica, Shon and Torri.

Elizabeth Koehn (EK): Hi Mary! In looking back over my notes from HBCU summer school program, it’s really awe-inspiring to see how the students took the central topic of the course—which was the concept of research—and spun it off into so many interesting dimensions of their own. … They went above and beyond simply connecting the content of the workshops to their chosen objects. They were proactively taking the day’s themes and applying them to a wide variety of larger topics and issues relating to their own interests and work.

It was a good decision to kick the course off with the BGC publication, What is Research? (the published transcripts of three conversations that Dean Peter N. Miller moderated in 2020 between scientists, artists, and humanists, all MacArthur Fellows) because it really set the tone for how diverse the scope of research, as we were looking at it, was going to be.

mary adeogun (ma): Having as loose a topic as research really allowed people to kind of run in whatever direction interested them. And we saw that in the program, where some students responded to specific topics more than others. Do you remember the session we had with botanists, curators, and researchers from the New York Botanical Garden?

There was a moment where one student was completely in the zone. Based on his line of questioning, the conversation took multiple directions: from the different plants they preserve in the herbarium, to plants as a healing and spiritual tool, with psychedelics being used to treat PTSD and depression. There was a similar response from a few students who are artists to the Artists Doing Research talk, which included Tomashi Jackson, Richard Tuttle, and Vanessa German. They talked about their work—what it’s responding to in this world and how research informs it.

EK: That was such a special session—Vanessa opened her part of the talk by going through the list of participants and giving voice to every single person’s name. That really set a tone for everyone. I think you could see that they felt that sense of reciprocation with the speakers. All of the speakers throughout the program are experts in their fields, doing such amazing things, and they were so generous and willing to engage with the students. They took their questions seriously. There was a lot of respect going both ways, and I think that contributed to making it a successful program.

ma: For sure. And that also sometimes meant questioning the information being presented.

For example, in the investigative journalism session with Nicholas Lemann from Columbia’s journalism school. There were a lot of questions from students, especially around the more undefined boundaries of journalism. Some of the students were wondering, can anyone just say anything?

EK: That’s a good point about the journalism session, because I remember that was one area where we, as TAs, actually felt it was important to push back on some of the student responses— I remember students in our evening session expressing a lot of skepticism about notions of journalistic truth. I think a lot of that stemmed from the recent political discourse around what constitutes “fake news,” but I also think they applied some of the critical points raised by historian Marisa Fuentes, in her session from earlier that day—where she discussed absences in the archival record—to their understanding of journalistic objectivity. Students really responded to the ideas that she raised about narrative construction, how it is contingent on the information that is preserved, and how you always need to be aware of the facts and perspectives that are left out of the record. So even if that emphasis on criticality that she raised took a direction in our group discussion

about journalism that we felt we needed to correct a bit, it was still interesting to watch how the students were synthesizing and drawing points of connection between the various topics and approaches raised by the different speakers throughout the week.

ma: Fuentes made it very clear that she does not make things up. I love that she stressed not running away with the idea of creativity in the archives as we imagine things that weren’t documented. It’s a rigorous exercise of understanding the possibilities given the bounds of the archive, and then connecting the dots. But also, when you don’t have enough information, letting the silence linger, while still acknowledging that something was there. That’s powerful. The topic and the scholarly attention paid to archival silences is so pervasive and important in academia, especially in relation to communities, groups, and histories that don’t fit cleanly into a Euro-American academic version of archive.

There are many possibilities within and outside of that. That’s why I really enjoyed Mpho Matsipa’s talk on our final day about research as a way to destabilize EuroAmerican claims to knowledge about African cities and public spaces. For example, the project

African Mobilities being a scholarly portal where theorists and creative practitioners across the continent can come together, access their histories, and imagine their futures on their own terms.

EK: That’s such a good point. It brings to mind our visit from Tammi Lawson, from the Art and Artifact Division of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Some students said, “I didn’t think that would be in an archive.” That visit was such an important way to alert people to the fact that various types of archives exist, and that if they haven’t in the past, people are working to remedy or reorient our notion of what should be preserved.

ma: The expanded understanding of archives, and the bodies of knowledge that are within archives, was explored by so many of the speakers. Memory is a really powerful archive, and that concept resonated with me, because it made me think of oríkì, which is a Yorùbá concept of a being or family’s story, their epic, that is passed from generation to generation, often orally. In Yorùbá Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art, scholar and art historian Rowland Abiodun notes that oríkì is not passive, but active. Pronouncing an oríkì invokes or summons the subject into action. And though I refer to

oríkì that’s spoken, it can also be invoked through art, spaces, dance, and so on. An oríkì can be recorded on an audio device or in writing, but it doesn’t necessarily have a history of being passed down in that way. To me, it’s one of the most precise archives because to speak it correctly and pass it down to the next person, you’ve got to have that thing down pat. It always struck me that among this community it’s considered archival, but among other communities, it’s not.

I think over the course of the week, it was striking to see the connections in what we each recognize as “archive” and how a lot of these lecturers in their practices have either defined that on their own terms, or found ways to address the gaps in whatever definition of archive they’re working with.

EK: That point you raise about different forms of knowledge and specifically archival knowledge, and how information can be passed down through families and oral histories rather than being recorded in official documents, I think that was reflected also in many of the objects that the students chose to research. I’m thinking of a few students who chose to research family heirlooms, such as a grandmother’s jewelry box, Guyanese gold bracelets

passed down to firstborn daughters, or a pillow made by a mother for her baby.

So many of them were objects that were deeply embedded in their familial histories and relationships. And I think that point you raise about the validity of these different forms or sources of knowledge is so important in this regard. It emboldened a lot of the students in the final conclusions that they were making about their objects: “Yes, this is a story worth telling, even if it wasn’t written down in a newspaper. This is my family’s story and it’s expressed, not through text, but through this object that I now have in front of me and I’m looking at and I’m holding and I’m asking questions about.” For me, watching the students expand their notion of research, whether that meant broadening their understanding of the kind of sources worthy of being consulted, or how to look critically at those sources, or reassessing the types of subject worthy of research, was the most fulfilling part of being a TA.

ma: I hear that.

EK: I also want to shout out how amazing these students were, because this was an extremely rigorous curriculum. They were in class from 9 am until noon, hearing speakers but also engaging in good,

rich discussions. Then there was a lunch break, and a second session with speakers and discussion in the afternoon. Then they met for an hour on their own to rehash the day (no professors or TAs allowed), before taking a dinner break, and then they met with us for an hour in the evening to go over questions and reflections on the day’s presentations. And of course they also were doing the reading and prep work for the following day’s seminars. They were unbelievably active and engaged throughout an extremely intense week.

ma: This was my first experience as a TA, too, and I learned so much from the students, including through the constructive feedback they gave us when the program had wrapped up. I’m curious. Did you do any preparation? How were you thinking about being a TA?

EK: I was mostly just trying to get over my sheer terror at being in a position of authority, which I’m not used to. And it was really important to me, as a teacher, to be honest about my intellectual background, and the things that I know but more importantly the things I don’t know. For me, that’s a really radical, feminist act, of acknowledging what your limitations are, and not feigning authority for the sake of preserving that teaching role. In that regard, it was really helpful

for me to be in an environment like this, where students were so willing to engage one-on-one. It validated for me that that is a legitimate way to approach teaching: not as an authoritarian, but as someone who really can go in learning from other people, as much as they can learn from you. Obviously, I wanted to make sure people were getting what they needed and point them to resources that I knew of that they could use. But working with these students affirmed for me that teaching should be more of a dialogue than a unidirectional vector. What about you? How did you prepare?

ma: I’m also not very experienced when it comes to teaching, but as a student, I find that when I am able to participate in a learning experience that feels more dialogical, I gain so much.

And so, to answer your question, “How did I approach it?”, I started out very nervous and scared. I think I didn’t want to say the wrong thing. I did not want to send anybody in the wrong direction. But to your earlier point, that incorrectly assumes that students don’t already have their own processing power to filter through what’s BS and what’s real. When I started working with the students, it calmed me down a bit. At the end of the week, I’d learned

so much—from the lecturers and administrators, from the students, and from the experience of being a TA.

mary adeogun (MA ’22) studies textiles, garments and dress culture. For the past four years she has focused on Yorùbá dress culture and textile practices from her family heritage, relying on conversations with stylish aunties about their lace and aṣọ òkè, interviews with àdìrẹ collectors and scholars, and brief apprenticeships or workshops with practicing textile artists. Other interests include fiber and dyeing science, how clothes are displayed, American dress culture, and everyday dress habits. She is grateful to the many loved ones and teachers in her life that make this learning possible.

Elizabeth Koehn is a PhD candidate at Bard Graduate Center who is currently researching pneumatic furniture designs of the 1960s and 70s in relation to the concept of utopia. She completed her MA at BGC in 2020 with her qualifying paper, Designing Destruction: Archizoom Associati’s Superonda Sofa as Radical Critique, in which she examined the formal and material qualities of Archizoom’s 1966/67 seating design in the context of the group’s theoretical projects, essays, and archival materials questioning the relationship between design and consumerism. In 2019, Koehn interned in the design, architecture, and digital curatorial department at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where she worked directly with the museum’s Rapid Response Collecting curator on new acquisitions. Prior to her studies at BGC, she held positions working with artists at the New York-based galleries Gavin Brown’s Enterprise and David Zwirner after earning her BA in history and art history from Oberlin College in 2009.

2020–22 was unlike any other time in Bard Graduate Center’s history. It was certainly the most challenging, as the Covid-19 pandemic forced our institution into remote teaching and research in 2020, followed by a concerted effort to return to on-site education. Despite its many difficulties, the institution continued to thrive because of the dedication of our students, faculty, and staff.

I finished the William Watt (1834–85) entry for the Dictionary of British and Irish Furniture Makers, 1500–1914. He was best known for his Aesthetic furniture designed by E.W. Godwin, the subject of my doctoral dissertation. I discovered unknown biographical facts and rounded out the details of his London cabinet-making and upholstery business. Another Godwin-related subject that I revisited was the life and work of George Freeth Roper, an understudied Manchester architect and designer who worked in Godwin‘s office at the beginning of his career. His furniture was often confused with Godwin’s. I worked up my preliminary research into a Brown Bag Lunch talk entitled “George Freeth Roper (1843–92): Slavish Imitator or Undervalued Architect/Designer.”

Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915, finally opened

in the Bard Graduate Center Gallery in the fall of 2021. Its three-volume catalogue, which I edited, won the 2021 Historians of British Art Book Prize for an outstanding multi-authored book on the history of British art, architecture, and visual culture. The show subsequently traveled to the Walters Art Museum, where it opened in March and received ongoing positive reviews, including from the Wall Street Journal and the National Review. It will remain at the Walters through August 2022 and then transfer to the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stokeon-Trent, England, where it will be on view from October 2022 until January 2023. BGC’s curatorial and development teams worked closely with the Potteries Museum staff to ensure that our exhibition would have a showing in Stoke-on-Trent, where so many of the objects in the exhibition were created.

In addition to my work on Majolica Mania, I completed and presented a paper on “Sèvres Majolica Production under the Second Empire” in September 2021 for the BGC symposium on French influence on majolica production in England. The research period was particularly problematic since the French archives were closed to visiting scholars. I wish to thank director Charlotte Vignon and her archivists for assisting me in accessing the papers of the Sèvres majolica atélier.

In 2021 I also began research for the upcoming 2026 BGC exhibition on Philip Webb, Arts and Crafts Architect and Designer. It will showcase the many talents of Webb, ranging from remarkable buildings to beautiful furniture, stained glass, glassware, and book bindings.

As for teaching, in 2020–21, I led a year-long seminar for two first-year students on the history of the chair. We examined royal thrones from the ancient world to contemporary mass-produced seating forms. Questions of connoisseurship, materials, ergonomics, construction, hygiene, and affordability were all part of our lively weekly discussions. We used chapters from Witold Rybczinski’s Now I Sit Me Down: From Klismos to Plastic Chair (2017) to frame our sessions. Students led the study of twentieth-century seating forms with a series of presentations.

Starting in fall 2020, I assisted Deborah Krohn with graduate admissions and convened both the fall and spring semesters of “Objects in Context” as part of a thorough revision of our first-year core curriculum undertaken with Catherine Whalen. With Andrew Morrall, I co-taught the field seminar “Readings in Early Modern Visual and Material Culture,” exploring both established and

40 2020–22 in Review

emerging approaches to objects and related images in Europe ca. 1500–1800.

On my own, I offered seminars on “The Grand Tour”—an appropriately virtual form of travel during a pandemic—in which participants followed specific travelers with special attention to the material, educational, and experiential aspects of moving around Europe in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. A further seminar on “Fire! Staging the Hearth in Eighteenth-Century France,” began laying the groundwork for a forthcoming Focus Exhibition on French eighteenth-century gilt bronze firedogs, scheduled to open in February 2027. In May 2022, after a two-year hiatus, I led eleven BGC MA students on the intensive, tenday Bard Travel Program in Paris, organized in conjunction with the École du Louvre.

On the research front, I contributed a chapter entitled “Winckelmann et la peinture: construire le sens d’un art disparu” (Winckelmann and Painting: Making Sense of a Lost Art) to the volume Winckelmann et l’oeuvre d’art: Matériaux et types (Winckelmann and the Work of Art: Materials and Genres), edited by Cécile Colonna and Daniela Gallo and published in May 2021 by the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art in Paris. My essay traced the Prussian scholar’s changing approach to understanding and evaluating

ancient painting in the face of a disjuncture among the slender physical evidence, largely from the Roman period, and the dictates of an aesthetic theory predicated on white marble sculpture understood to be Greek. Two further essays appeared in the Bloomsbury

Cultural History of Furniture, edited by former BGC research fellow Christina Anderson and published in March 2022: a chapter on visual representations of furniture for the volume covering 1500–1700, and a chapter on furniture in the public setting for the volume on the eighteenth century.

In fall 2020, I taught “Curatorial Practice and American Art at the Metropolitan Museum.” A different curator from the American Wing joined the class remotely each week. In spring 2021, I was attached to the Bard Graduate Center Research Institute and worked on a book project entitled Museum Values. My fall 2021 courses were “History and Material Culture: New Directions” and (with Soon Kai Poh) “In Focus: Conserving Active Matter.” In the former, every contributor to the Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture joined the class remotely, three each week. In spring 2022, I taught “University Museums: Collections in Academia and their Uses.” Each week a museum director or curator from universities in North America and Europe talked

remotely with the class. With Soon Kai Poh, I also taught “Damage, Decay, Conservation.”

As was the case for everyone, the pandemic radically affected my activities in the academic years 2020–21 and 2021-22. I could not take up my usual residence in Göttingen as a permanent fellow of the Advanced Study Institute in either summer or deliver the typical number of lectures. I presented papers online at the American Society for Aesthetics annual national conference in fall 2020 and its eastern division conference in spring 2021. My spring 2021 fellowship at the Centre for Advanced Study of the Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich, was postponed due to the pandemic, but I presented a paper in the fellows’ inaugural workshop online in May 2021. I gave a paper remotely in June at the Advanced Study Institute, Göttingen. In November, I contributed a paper online at a symposium held in Madrid on Hans Heinrich Thyssen as an art collector.

Owing to the illness of the chair of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Advanced Study Institute of the Georg-August University, Göttingen, I was elected to the chair in the fall of 2020 when the Institute was threatened following cuts in funding. Despite an international campaign in fall 2021, the university closed the Institute. The director and the Scientific Advisory

Board of the Central Collections of the Georg-August University, Göttingen, of which I am a member, were successful in securing a large grant from the German federal government for the building and operation of the Forum Wissen (Knowledge Forum), the future central collections facility for the university that opened in May 2022.

My publications between 2020 and 2022 include “Living or Dead,” in Luca Del Baldo’s The Visionary Academy of Ocular Mentality: Atlas of the Iconic Turn (De Gruyter, 2020); “Harvard, History, and a House Museum,” in LaurelX: A Non-Traditional Festschrift in Celebration of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, ed. Christopher Allison, John Bell, and Sarah Ann Carter (Harvard University Archives, 2020); “Cracking Up with Piet Mondrian,” in Proceedings of the 34th World Congress of Art History, Beijing, 2016 (Beijing, 2020), Vol. 3; “Active Matter: Some Initial Philosophical Considerations” (with A.W. Eaton) in Conserving Active Matter, ed. Peter N. Miller and Soon Kai Poh (University of Chicago Press, 2022); “Toward an Aesthetics of Degradation” (with A.W. Eaton) in Conserving Active Matter: Essays (Bard Graduate Center, 2022:); “New Galleries of Dutch and Flemish art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” The Burlington Magazine 164, 2022; “Göttinger Dämmerung,” Merkur, March 17, 2022; and “The Brutish Museums,” West 86th online, April 6, 2022.

42 2020–22 in Review

My co-editor Sarah Anne Carter and I received the 2021 Allen G. Noble Book Award for best-edited publication from the International Society for Landscape, Place, and Material Culture for The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture (Oxford University Press, 2020).

The anni horribilis of 2020–22 were dominated by Covid-19 and, for me, three other big “C”s: colonialism, cannibalism, and conservation. In the middle of this period my new book, Writing the Hamat’sa: Ethnography, Colonialism, and the Cannibal Dance, was published by UBC Press in July 2021. Bard Graduate Center hosted an online book launch later that fall. I’ve since given talks about the book at the University of Connecticut, for Nanaimo Ladysmith Public Schools, and at the 2021 American Anthropological Association conference. With BGC colleagues, I continued curatorial work on the exhibition Conserving Active Matter by helping select global Indigenous materials for loan and editing the companion volume’s section on Indigenous ontologies. Additionally, I published two essays for the project (one for print, one for the website) on the notion of Indigenous ontologies of active matter.

After a fall 2020 residency in BGC’s Research Institute, I co-taught two spring 2021 courses: “Objects of Colonial Encounter in North America” with BGC/American Museum of Natural History Postdoctoral Fellow Hadley Jensen, and “Unsettling Things: Expanding Conversations in Studies of the Material World” with Meredith Linn. The latter is an ambitious new course bringing together BGC faculty and visiting speakers to explore diverse forms of critical material culture scholarship; I coordinated this course again in spring 2022 with Caspar Meyer. This academic year, I also taught “The Social Lives of Things: Anthropology of Art and Material Culture” and “Exhibiting Culture(s): Anthropology in and of the Museum.”

Over the past two years, I participated in numerous online conferences and international workshops, including People: A Global Dialogue on Museums and Their Publics at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Putting Theory and Things Together: Conversations about Anthropology and

Museums at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History; and The Museum as Archive: Using the Past in the Present and Future at the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture, University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand. I also delivered lectures to classes at Columbia University, NYU/IFA’s Conservation Center, and University of Alaska. In the realm of public scholarship, I was interviewed for a documentary film about the photographer Edward S. Curtis, and I produced two podcast conversations related to Indigenous art: one for SmartHistory and the other for BGC’s Fields of the Future series.

During the 2020–21 academic year, my ongoing research on glass and transparency in modern design was published in peer-reviewed journals and edited volumes: “Cleanliness, Clarity—and Craft: Material Politics in German Design, 1919–1939,” in the Journal of Modern Craft (December 2020);

“Enemy of Secrets: The Invisible Force of Interwar Glass,” in the Journal of Design History (May 2021); “Empty by Design: Transition, Transformation, Transparency,” in I Am All of Glass—Marianne Brandt and the Art of Glass Today (Jovis, 2020); and “Experience, Poverty, Transparency: The Modern Surface of Interwar Glass,” in Surface and

Apparition: The Immateriality of the Modern Surface (Bloomsbury, 2021).

“The Emperor’s New Glass: Transparency as Substance and Symbol in Interwar Design,” was recently published in Material Modernity: Innovative Visual and Material Work in the Weimar Republic (Bloomsbury, 2022), and “Dürer, Goethe, and the Poetics of Richard Riemerschmid’s Modern Wooden Furniture” appeared in Design and Heritage, edited by Rebecca Houze and Grace LeesMaffei (Routledge, 2022). My first book, Richard Riemerschmid’s Extraordinary Living Things, will be released in October 2022 with the MIT Press. The publication of this book has been supported by a production grant from the Graham Foundation. Related material, “Holz: Wood and the German Werkbund in 1933,” will be included in a special fall 2022 issue of the Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, devoted to the significance of nature in material and visual culture during the Third Reich.

A new course that I taught for Bard Graduate Center students in spring 2021, “Doll Parts: Human Forms in Material Culture and Design History,” has shifted my research focus: I am currently developing this topic both for my second book and for my 2025 Focus exhibition. I will be teaching my first exhibitionrelated course, “In Focus: Welcome to the Dolls’ House,” in the fall of 2022, while simultaneously

44 2020–22 in Review

pursuing this research as the fall semester’s Faculty in Focus. MIT Press has invited me to submit a proposal for the related book—Doll Parts: Designing Likeness—which I will be constructing this summer in conjunction with research at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York.

With travel and research on hold in 2020–21, it was the ideal time to put the finishing touches on various projects. I submitted final versions of two book chapters: one on a sixteenth-century French book of poems about the household and various furnishings for an anthology called Spaces of Making and Thinking edited by Colin Murray, Sophie Pittman (BGC MA ‘13), and Tianna Uchaz; and a second called “Verbal Representations of Furniture in Early Modern Europe” for A Cultural History of Furniture in the Age of Exploration, to be published by Bloomsbury. I also drafted a book that will appear in conjunction with a Bard Graduate Center exhibition, Staging the Table in Europe 1500–1800, that will open in February 2023. In fall 2020, I delivered a paper at an online conference sponsored jointly by the Newberry Library and the Folger on “Food and the Book, 1300–1800.” Perhaps most exciting, I was fortunate to appear alongside restaurateur and cookbook author Yotam Ottolenghi in a documentary

called Ottolenghi and the Cakes of Versailles, filmed during an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in summer 2018 for which I served as historical advisor. Though movie theaters were closed, the film was available on various platforms. I participated with the director and producer on numerous Zoom programs that followed screenings of the film for neighborhood and community groups all over the country.

In 2020–21, I was involved in several new teaching, writing, and resource creation projects. I co-created, co-organized, and cotaught the summer 2020 Lab for Teen Thinkers program with Carla Repice, Bard Graduate Center’s then-senior manager of education and engagement, and PhD student Tova Kadish. In response to the pandemic, we doubled the number of teens involved and shifted from an in-person to an all-online program. With the assistance of Jesse Merandy, I also created an extensive online resource of readings for the teens. With Catherine Whalen, I compiled a shared list of resources for the study of African American and African diasporic history and material culture.

In fall 2020, I co-taught “Approaches” with Freyja Hartzell and designed and taught a

new course called “Medical Materialities.” With Aaron Glass, I co-designed and co-convened the new “Unsettling Things” course in spring 2021, inviting many BGC colleagues and outside scholars to present their research and engage in conversations about applying critical perspectives to expand the study of objects. I also supervised Tova Kadish’s independent study about landscape analysis using geographic information system mapping.

Also in 2020–21, I established a new BGC internship with the Furniture History Society in collaboration with Adriana Turpin and again supervised the MA student internship process in the role of director of master’s studies. I also gave guest lectures in courses at the CUNY Graduate Center and City College and for BGC’s 2021 summer school for students of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. For my BGC Work-in-Progress talk in fall 2020, I presented part of a paper about nineteenth-century patent medicines that I drafted for a special issue of the journal Historical Archaeology. During the 2020–2021 academic year, I co-authored, with Nan Rothschild and Diana diZerega Wall, a chapter about Seneca Village for the book Advocacy and Archaeology: Urban Intersections, edited by Kelly Britt and Diane George and to be published by Berghahn Books. Additionally, I edited nine chapters contributed to Revealing

Communities: The Archaeology of Free African Americans in the Nineteenth Century, a book to be published by BGC based on the symposium of the same name I convened in the spring of 2020.

In 2021–22, I continued to work on the Lab for Teen Thinkers program, which ran as a hybrid program in the summer of 2021. Carla Repice and I also created three and ran two Seneca Village professional development workshops, collaborating with Marie Warsh of the Central Park Conservancy, Alice BaldwinJones, a food anthropologist and member of the Advisory Board of the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History, and graduates of the previous year’s teen program. Additionally, I worked with BGC student Laura Mogulescu to develop a flexible lesson plan about foodways and food-related artifacts at Seneca Village. The workshops and lesson plan were part of a project to create an exportable Seneca Village curriculum.

For BGC students, I taught two courses in the fall of 2021: “Excavating the Empire City” and “Archaeology of African American Communities.” The latter was a new course I designed with the goal of centering the work of African American scholars. This academic year, I supervised one dissertation defense (Rebecca Matheson), one PhD qualifying exam (Emma

McClendon), two dissertation proposals (Adam Brandow and Tova Kadish), and one MA qualifying paper (Pim Supavarasuwat).

This spring, I have given several guest lectures in courses at Columbia University, the CUNY Graduate Center, and New York University, and one at the Irish Consulate for the African American and Irish Diaspora Network. This semester, I have been on pre-tenure sabbatical, revising my monograph about illness, injury, and healing among Irish immigrants in nineteenth-century New York City and pulling together the last chapters of Revealing Communities: The Archaeology of Free African Americans in the Nineteenth Century.

I spent 2020–21 socially distancing at home with my family in New Jersey. I offered two courses on Zoom: “Foreign Luxuries and Chinese Taste” and a new course on the art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (ca. 250 BCE to 8 CE), in which my students and I familiarized ourselves with the rich archaeological finds and scholarship of the past twenty years. At the end of the 2020–21 academic year, I concluded my tenure as director of doctoral studies, which meant that I was able to offer four courses in 2021–22: those consisted

2020–22 in Review

of an immersion into tenth- to thirteenth-century archaeological materials of the Liao and the Song dynasties. These were followed by spring classes on gardens and on Shang and Zhou ornament. I gave talks on Liao archaeology at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and on the Belitung shipwreck at Yale University. My 2003 article, “Shaping Symbols of Privilege: Precious Metals and the Early Liao Aristocracy,” was republished in 2021 in the fiftiethanniversary volume of the Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. Another article, “Metal Objects on the Tang Wreck,” has been translated into Chinese as part of the Chinese edition of the catalogue The Tang Shipwreck: Art and Exchange in the 9th Century. The book is edited by the Asian Civilisations Museum

in Singapore and will hopefully be printed later this year. I am currently revising an article on “Qianlong’s Jue Tripods and Pre-Antiquarian Learning.”

In 2020–21, I taught “Modes and Manners in the Eighteenth Century” and “Nineteenth-Century Fashion,” which provided a welcome distraction from the strangeness of the times. Both classes were mostly remote, but in spite of this less-than-ideal situation, the journeys through these two centuries were stimulating and rewarding. Over the course of that year, I enjoyed getting to know two first-year students in Bard Graduate Center’s recently introduced “tutorials,” both of whom were in my fall 2020 and spring 2021 classes. In December 2020, I had an Instagram Live conversation with BGC alum Leigh Wishner (MA ‘04), now at Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising, about one of my idols, Esther Williams. That month, I was also given the task of acquiring at auction a number of wonderful nineteenth-century garments on behalf of BGC for its Study Collection. In February 2021, I moderated the Modern Design History Seminar Series evening with guests Christopher Breward and Michelle Tolini Finamore. In spring 2021, I advised two secondyear students’ qualifying papers

and one of my doctoral students, William DeGregorio, successfully defended his dissertation, “Materializing Manners: Fashion, Period Rooms, and Gentility at the Museum of the City of New York, 1923-1958.” Since October 2020, I have been working with Emma Cormack (BGC) and Ilona Kos

(Textilmuseum St. Gallen) as cocurator for an exhibition that will open at the BGC Gallery this fall, Threads of Power: Lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen. I’m very excited to be involved in this project, which will take me through—and slightly beyond—my retirement from the BGC faculty in June.

In June 2022, Bard Graduate Center (BGC) assistant professor Michele Majer retired after eighteen years of teaching the history of dress and textiles. Several BGC alumni mentored by Majer (Emma Cormack MA ’18, an associate curator at BGC who is currently working on the Threads of Power: Lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen exhibition with Majer; Billy DeGregorio PhD ’21, a freelance researcher and one of the authors of a two-volume set about the collector Percival Griffiths, forthcoming from Yale University Press; Kirstin Purtich MA ’15, wardrobe manager at Garde Robe, the luxury fashion storage company; and Leigh Wishner MA ’00, the digital media and content manager for Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising in downtown Los Angeles who is currently at work on a book about twentieth-century American textiles and their design significance) recently discussed her impact and shared their memories of studying and working with her. Here are some excerpts from their conversation; you can read the full transcription on bgc.bard.edu.

Emma: I showed up to BGC as a pretty freaked out and overwhelmed twenty-three-year-old. Michele’s class was the first one of my whole BGC career. And I was really nervous beforehand. She was so welcoming, and I felt comfortable to say whatever was on my mind, even if it wasn’t correct. And then I took every class that she offered, and eventually, we took a trip to Cora Ginsburg, which was so amazing. And then I came back by myself a different time, and Michele and Titi [Titi Halle, owner of Cora Ginsburg] brought out a silk moiré gown and a little spencer and were like, here you go. And then they left the room, and I was stunned. I could study and write about them … And Michele would connect me with past students. Her network of people is huge, and she’s so generous with making those connections. Everyone’s very happy to be connected with another “Michele person.” And working on this lace project (Threads of Power) has been amazing. Making an exhibition is so much work, and you spend so many hours sitting together and traveling together, and I feel so lucky that I’ve been able to do it with Michele.

48 2020–22 in Review

PHOTO CREDIT / CAPTIONBilly: I would say the two things that stand out for me about Michele are patience and trust. When we started working on Staging Fashion, she had already collected binders of postcards, and we started to bond when I volunteered to transcribe all the postcards. And we would just sit for hours saying, “What do you think this word is?” And you know, they were all in French. We’d ask, “Should we transcribe the printed material, the copyright date?” It was the minutia of minutia, and she was always patient and game to entertain the questions.

Michele and Titi taught me how to dress any silhouette and various mannequin and photography tricks. That’s where the trust comes in. The community that studies actual clothing is small, and you very quickly get the sense of who you can trust: either they know how to touch an old dress or they don’t. And I’m glad that they trusted me. I also took every class Michele taught while I was there and did an independent study with her, and in addition I got to learn and discover on my own, with her guidance.

Kirstin: Michele was the first person who made me realize that fashion history was a pursuit in and of itself. I think my class might have been the first to have the “Approaches to the Object” methodology course. And after the fashion history lecture, it was so obvious to me that that was what I wanted to do. I think Michele brought some 1820s gown from Cora Ginsburg, and it truly was the first time I’d gotten to handle anything like that and see it up close. I had done costume design in college, but I’d never done research in a formal way. … I appreciated that Michele remains so intellectually curious. She would incorporate new research into her lectures and in individual conversations, and nothing was ever stagnant. She kept her classes fresh and engaging with new scholarship.

Leigh: I remember Michele handed each of us a document of eighteenthcentury silk to take home. We asked, “Are you sure we’re allowed to?” and she said, “Yes, and I expect you to take them out. I expect you to look at them, to touch them and feel them and examine them.” I don’t remember the actual assignment. I just remember coming home with something precious and feeling like my world had changed. And the field trip to Cora Ginsburg … We passed around shawls and corsets, we were looking at a lot of things, and we were able to touch them and feel them. It’s always about the primacy of the object. I could go on for hours. I love Michele so much and I owe her so much.