10 minute read

Three Trajectories

Yusu Mao and Shankhadeep Mukherjee, CRU Group, present the changing dynamics of steel production in Asia and its impact on iron ore and metallurgical coal producers.

As the pandemic and ongoing trade actions radically re-shape supply chains, the pace of cyclical turns in the steel industry continue to accelerate.

Stimulus measures in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic increased both demand for durable goods and consumers’ ability to pay for them. Spend was directed towards big-ticket items over services in all parts of the world. Increased sales of white goods boosted demand for steel and, once vaccines arrived, the increased optimism buoyed demand further. Furthermore, when stalled construction projects picked up, that demand soared even higher.

Concerns around global supply chain issues caused panic buying, with end users ordering excess volumes. As idled supply took time to restart, steel prices hit the highest levels ever seen. As Figure 1 shows, this caused, albeit temporarily, prices to de-link from costs. Over the 15-year period (2006 – 2020) margins for steelmakers were around 5 – 10%. During peak COVID-19 recovery however, they crossed 50% in some parts of the world!

Today, the cycle has turned again, and steel prices are once more on a rapid decline — along with steelmakers’ margins. As global recession looms, households are concerned about inflation, and, with lower/no pandemic restrictions, services are now available to absorb discretionary spend. CRU expects this downward correction and alignment with steel production costs to continue barring any extraneous factors.

An Asian story

As developed western economies stabilise, the global view of steel markets, for the next few years, is an Asian story. As Figure 2 shows, China continues to dominate global production, accounting for up to 53% of global steel output. India, the individual country in second place, accounts for just 7%, while Japan vies with the US for third place on 5% or 6%. The combined might of the 27 EU nations are only responsible for 10% or more.

With significant finished steel production capability, China has a key influence on the rest of the world. Being close to China, this impact is usually felt most swiftly by the countries in South and East Asia, but often in quite different ways.

Steel production in these regions will follow slightly different trajectories over the next few years, as government policies, economic fundamentals, and a changing consumer base will influence production volumes in the near term.

China: A steady decline

In contrast to China’s rapid economic growth, industrialisation and global influence through the Belt and Road initiative, the outlook for the Chinese steel sector is now much weaker.

COVID-19 lockdowns fuelled economic downturn and rising unemployment rates. Though the country has issued financial stimulus packages targeting steel intensive sectors, such as infrastructure and real estate, the benefits of these packages are yet to be seen. The latest data from China shows that new floor space starts for the first seven months have been down by circa 6% y/y, while floor space completed is down by circa 23% y/y. Rising debt – particularly among construction companies and real-estate developers – is also a key concern.

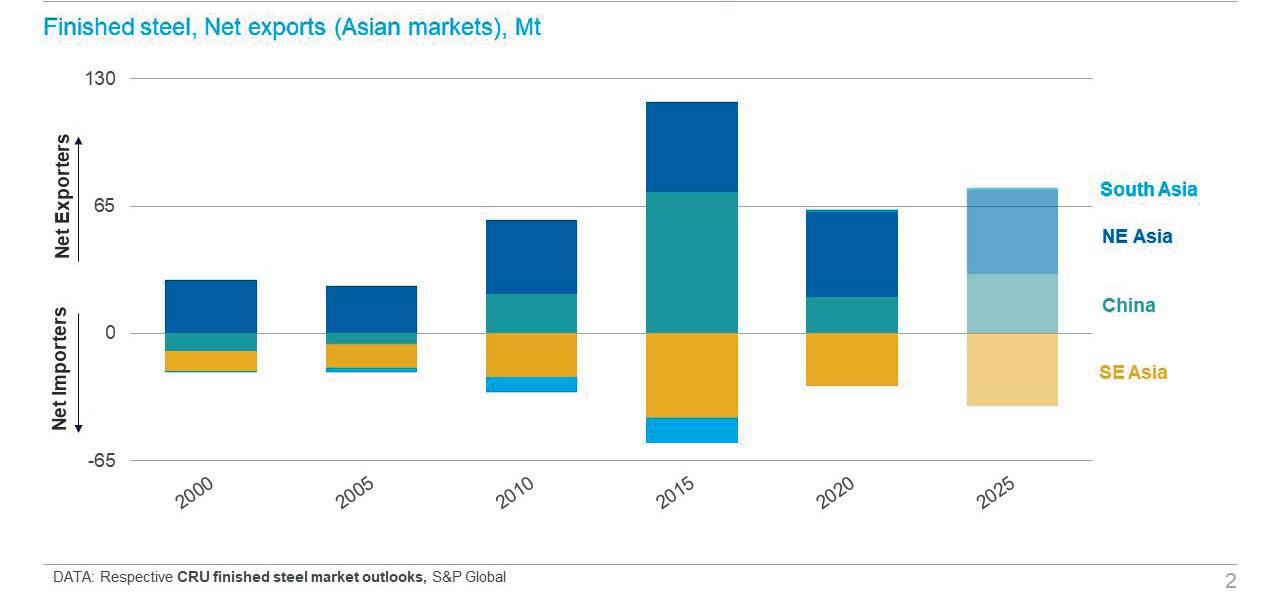

As Figure 3 shows, Chinese net exports hit a peak in 2015. It also shows the dramatic contraction between then and 2020 — the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government control on steel exports at a time when domestic demand is weak has led to negative steel margins for Chinese steel producers. CRU estimates that margins for 2Q22 will be negative for the entire quarter, with the first half of 3Q22 looking slightly better.

Costs and carbon

The obvious question from here is: what affect does the state of China’s domestic demand for steel have on the rest of the world? Five or six years ago, China was a major exporter of finished steel. More than 100 million t of Chinese steel hit the global markets at peak, putting pressure on steelmakers elsewhere and raising the spectre of tit-for-tat trade wars.

That will almost certainly not be repeated as China does not wish to be a major steel exporter. To produce steel in volumes for the export market, China must import raw material — mostly iron ore. The money that flows out of the national economy as a result, plus the high levels of carbon emissions that this amount of steel production will cause, are now seen as far too high a price to pay.

The shift in production route for China’s steel production technology is also applying downward pressure on its export capabilities. Nearly 90% of current Chinese steel production relies on the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) process. That compares to 60% in the EU27+UK and just 30% in the US, where the electric arc furnace process (EAF) is far more prevalent. In this China is not alone: most of Asia favour BF-BOF production, albeit with different drivers.

BF-BOF production, which is used to produce virgin steel, requires iron ore and metallurgical coal. Although Chinese mills import only 5 – 10% of its metallurgical coal requirements, 80% of its iron ore consumption comes from miners in other countries, most importantly Australia and Brazil, who are far more competitive than China’s domestic counterparts.

The use of coal as a reductant in the BF-BOF process means that this route produces much higher carbon emissions than EAF. The transition to EAF will therefore be an important path forward for China, both in terms of viable exports and carbon emissions. However, this is where China’s rapid growth creates a problem. EAF requires quantities of

Figure 1. Tougher times are ahead as demand falls and supply chains adjust (NOTES: Costs show the 95th percentile of the CRU Steel Costs Curve, as determined by the CRU Steel Cost Model).

The Motion Metrics Ecosystem for Mines integrates several key data solutions at every stage of the mining process. Our systems work together to create a detailed view of mining productivity and efficiency, while increasing safety and decreasing operational downtime associated with crusher jams and equipment maintenance.

A complete bucket monitoring solution for all shovels and excavators. Mitigate production loss caused by tooth breakage and improve safety. Monitor each truck on its way to the crusher by analyzing volume and oversized material.

An AI-enabled 3D vision belt monitoring solution with no belt cuts, calibration, or scaling objects required. Improve your blasting efficiency with handheld particle size analysis without scaling objects.

Monitor crusher input by accurately analyzing volume and particle size in every truck load.

Figure 2. Global carbon crude steel production by country (Mt) and market share (%).

Figure 3. Chinese influence in the Asian market expected to reduce.

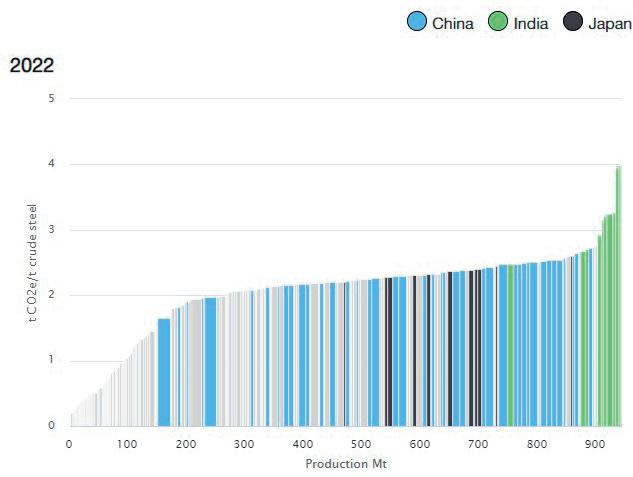

Figure 4. China, India, and Japan’s steel production-emissions profile for 2022. recycled scrap to be re-melted. China needs investments to build the necessary infrastructure to support greater use of scrap in its steel production, as well as to stockpile the quantities of scrap required, and increased recovery.

China could reduce emissions by switching to more iron ore pellets in its BF-BOF plants, but the reduction would be at most 10%. As a result, China will need to reduce its presence in the export market and produce mostly for domestic consumption.

Northeast Asia: Stability and dependability

Japan has been producing steel at high levels for decades and is also heavily reliant on the BF-BOF process, despite being completely dependent on imports of both iron ore and metallurgical coal. Besides sizeable direct exports of finished steel products, Japan has a thriving manufacturing sector, exports of which are also a key driver of steel demand in the country.

However, what happens in China very quickly affects what happens in Japan. This is because Japan is a net exporter to China. In a situation like that of China, Japan is unlikely to lift exports because of decreasing domestic production.

For Japan, the major shift in the steel industry would be capacity outsourcing. Domestic steel demand has been on a declining trend, especially now that Japan is facing large challenges from a shrinking population, which will limit steel demand growth in many end-use sectors. This will also lead to higher labour costs for the domestic manufacturing sector.

On the contrary, there has been much growth potential in the developing Asian markets. Therefore, Japanese BF-based producers have rolled out plans to cut down domestic crude steel production and re-align global capacity, by focusing more on the acquisition or investments in

overseas capacity to better serve overseas demand going forward. Therefore, CRU expects total crude steel production in Northeast Asia to fall throughout the medium term, and remain structurally lower than historical levels.

India and Southeast Asia: The upward curve

The country and region that stands to benefit from China and Northeast Asia’s reduced presence on the international stage is India and Southeast Asia. With its own rapidly expanding steel industry, India has taken great strides forward to become the second-largest producer in the world (although it still produces just over a tenth of its northern neighbour’s output). The situation is similar in Southeast Asia, where both domestic producers, as well as investors from China and Northeast Asia, are eyeing capacity expansion.

As the regions develop, there will be clear housing and infrastructure requirements. There is also a thrust to grow the manufacturing sector. As a result, the Indian and Southeast Asian steel industry is expected to continue its growth trajectory for the next few years. As Figure 3 shows, both the absolute amount of crude steel produced by India and its share of Asian BF-B0F production are set to increase by 2025. Southeast Asia, which started to move away from a predominately EAF production base, is going to witness a lot of BF-BOF investments.

In contrast to China’s raw material dependency, India is home to plenty of the iron ore used in its BF-BOF processes: more than is required by domestic producers. However, with only small quantities of often poor-quality metallurgical coal at home, it is almost entirely dependent on imports for the necessary supply. The growth in the share of BF-BOF production in Southeast Asia means that the region is also going to become a major consumer of both iron ore and coking coal.

Emissions impacts and the future

As the emissions curve in Figure 4 indicates, steel production in all three countries is at the higher end of the distribution. However, CRU does expect a change in the emissions profile as society and politicians respond to changing climate needs. The carbon-intensive nature of steel manufacturing through the BF-BOF route and China’s carbon neutrality target is a key reason for China and Northeast Asia to reduce/maintain their domestic production.

CRU expects China’s steel production will continue to decline, Japan’s to continue along a broadly straight line, and India and Southeast Asia’s steel industry to grow rapidly in the coming years. It is also likely, given the stringent focus on emissions norms, there may be some capacity relocation from China and Japan to India and Southeast Asia. As a result, the BF-BOF production route will maintain its dominance in the Asian market. Consequently, steel makers will still require large volumes of both iron ore and metallurgical coal. Focus on emissions, however, means that there will be an increasing trend towards higher quality raw materials.

Visit us! bauma, Munich, Germany October 24– 30, 2022 Hall B2, Stand 413