21 29

21 29

10 Bookme takes big leap with $20mn revenue target and acquisition talks at over $100mn price tag underway

14 What’s all the fuss about Green Financing?

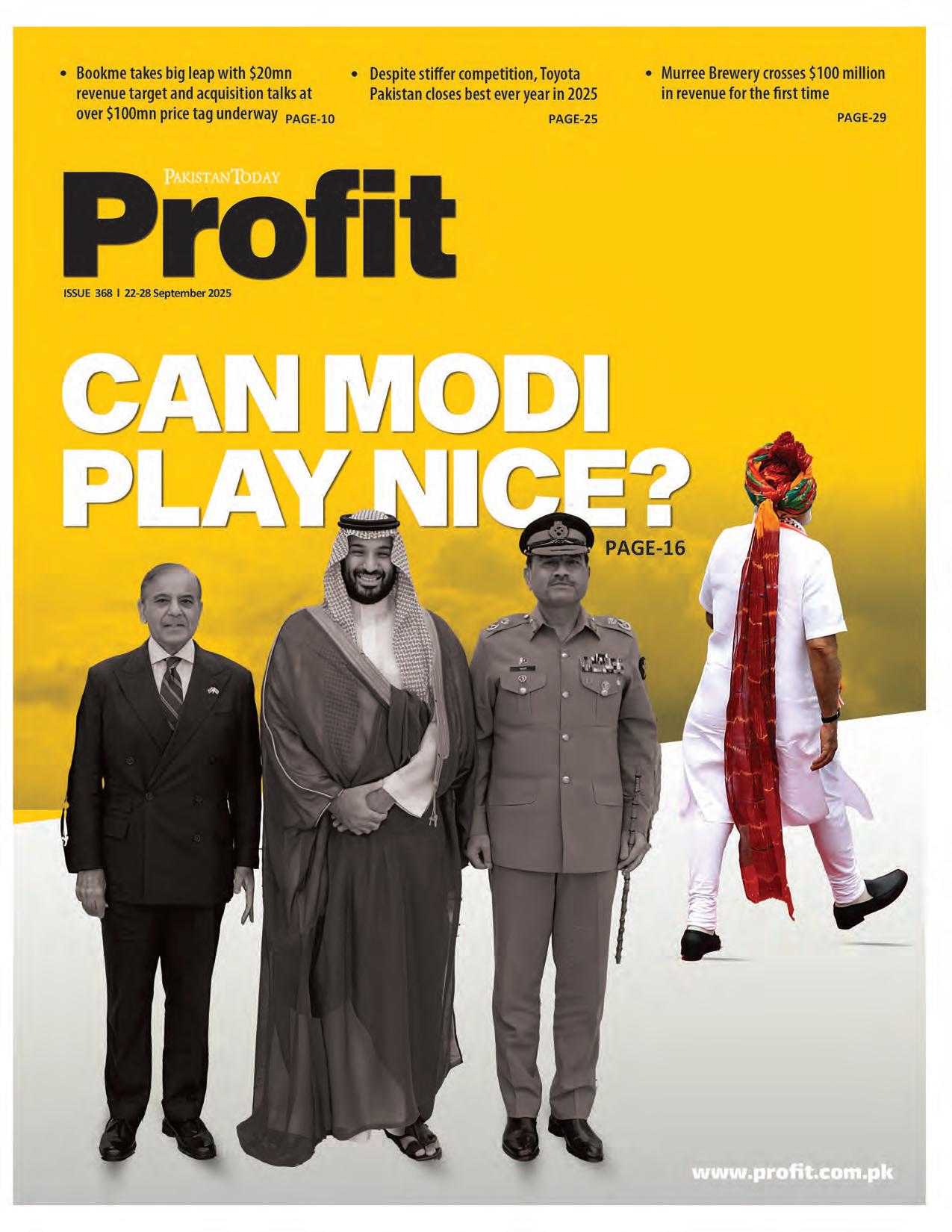

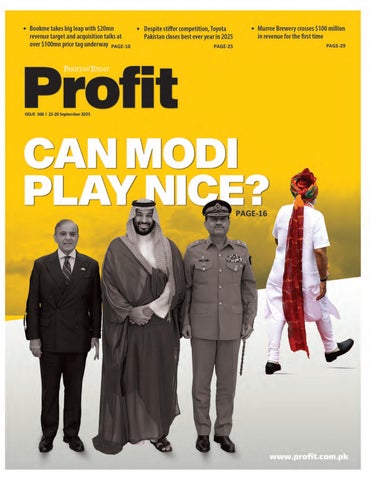

16 Could the Saudi-Pak Defence Pact force Modi and Islamabad to play nice?

21 Millat Tractors’ revenues tank over 43% in annus horribilis for Pakistani farmers

23 Declining production hits PPL’s bottom line

25 Despite stiffer competition, Toyota Pakistan closes best ever year in 2025

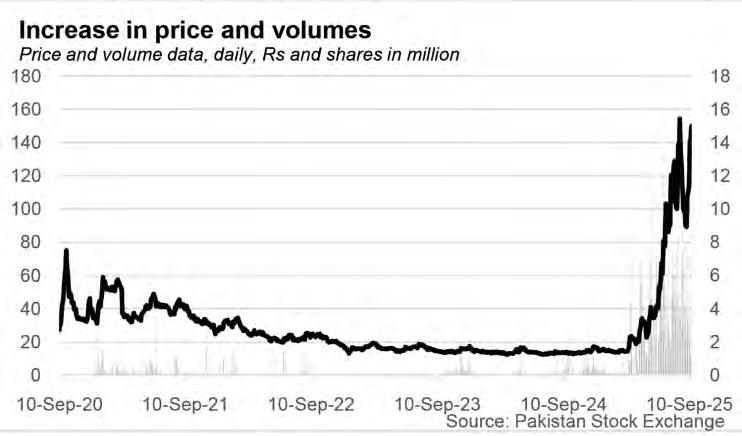

24 Bank of Punjab has been stable for a while. It took interim dividends for the market to notice.

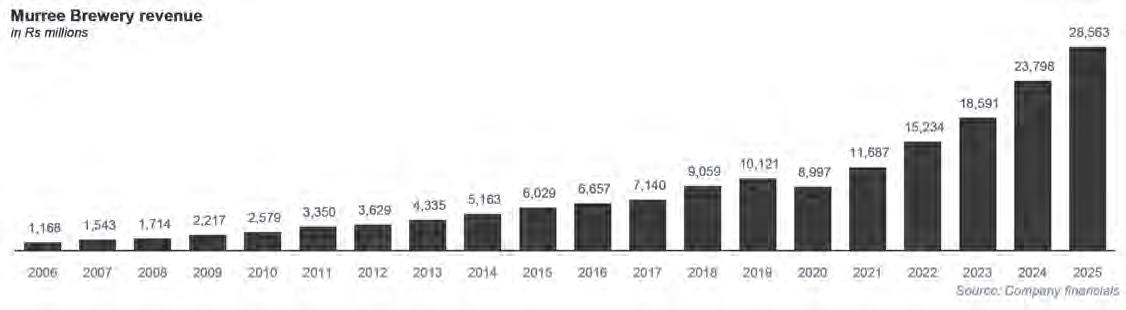

29 Murree Brewery crosses $100 million in revenue for the first time

32 Do Pakistani business groups know how to diversify? Asif Saad

34 Will Bunny’s rise?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Muddasir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi)

Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

takes big leap with $20mn revenue target and acquisition talks at over $100mn price tag underway

The Pakistani ticketing startup was launched in 2014. More than a decade later it is looking to expand beyond Pakistan and has found potential markets

By Mah Rukh Bodla and Taimoor Hassan

When you open Bookme’s website today, the most obvious change that you will notice is in its brand identity: what was once Bookme.pk is now Bookme. This rebranding reflects a shift in outlook. The company, which began as a domestic ticketing platform, is positioning itself for recognition in multiple markets rather than being seen only as a Pakistani service.

Over the course of a decade, Bookme grew from a small startup to Pakistan’s most widely used digital ticketing platform. Its app and website cater to millions of users, offering everything from bus reservations and cinema tickets to flight bookings and event passes. For many urban Pakistanis, especially young travelers, students, and families on the move, Bookme became the quiet solution to an everyday problem of saving time. Today, the company’s ambitions stretch far beyond bus terminals and box offices. In fact, Bookme is now actively reshaping its identity, transforming from a domestic ticketing service into a global digital travel player.

In this journey, Bookme has received an acquisition offer, rejected it and is currently reviewing another. It has cemented partnerships across borders as it looks forward to an era of exponential growth.

When Faizan Aslam first set out to build Bookme in Lahore back in 2014, few could have predicted just how quickly it would become a household name. At that time, Pakistan’s digital landscape was still finding its feet. Internet usage was limited, eCommerce was little more than an experiment, and banks clung to paper-based systems as though the digital revolution was still decades away. Yet, in the stubborn gaps of an underdeveloped digital economy, the CEO of Bookme saw a possibility. That of expanding Bookme’s footprint abroad.

That pivot took a decisive turn when the company received an invitation to a major conference in Saudi Arabia. Having seen an earlier death after a short stint in Myanmar, Faizan says he was wary of expanding into the Middle East but did so eventually because of an offer for partnership. One that would have

made their entry into the Middle East easy and cost effective. In fact Bookme is now expanding into the region using partnerships as a go-to-market strategy to even expand into the African market.

The decision to enter into the Saudi market was difficult. One would even question whether this is a sensible decision given that Bookme’s current market, Pakistan, is still unconquered. Bookme’s user base in Pakistan is around 15 million. Different organisations have attempted to solve the question of how many internet users there are in Pakistan. Most agree that it is somewhere between 38-54%. That would still mean a vast market is still untapped. On the other hand, the Saudi population is only 36 million people, with local competition like Almosafer and Almatar having strongholds in the country. Bookme still chose to expand.

“It was one of those moments when you realize the curve you’re standing on,” Aslam explained in conversation with Profit. “In Pakistan, adoption of online services is still slow. People hesitate, few banks still remain traditional and digital transactions make up barely twenty percent of all activity. But in Saudi Arabia, more than 90 percent of the population is already comfortable transacting online. For us, the question wasn’t if we should expand, it was how fast we could integrate.”

The Saudi connection began not only with the conference but also with strategic networking. Bookme’s leadership met with top executives, including the CFO of a major Saudi company, and quickly recognized the opportunities available in the Kingdom’s tech ecosystem. From there, partnerships began to take shape and agreements that would anchor Bookme in one of the Middle East’s most digitally advanced markets.

The contrast between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia could not be starker. In Pakistan, Bookme operates in a massive consumer market where the net margins in digital ticketing remain razor thin, ranging between 2%-3%. In Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, the population may be smaller, but the margins are healthier, between 7 to 9 per cent, and digital trust is already built into everyday life. This divergence is precisely what has convinced Aslam and his team that Saudi Arabia can serve as a launchpad for broader international growth.

Bookme’s credibility abroad is not being built from scratch. At home, the company has already demonstrated its ability to integrate with traditional financial systems. More than 25 banks, mobile wallets or fintech compa-

nies are connected to Bookme in Pakistan, a remarkable feat in a financial sector often described as “old school.”

Many banks continue to limit themselves to basic services, but Bookme carved a niche by offering seamless connectivity and smooth transaction pathways. For Aslam, this history matters. “If we could manage integrations in Pakistan, with all its legacy systems and limitations, we can do it anywhere. That’s why we feel confident about Saudi banks and, in time, financial institutions beyond,” he says.

“In the beginning, when we had no investment but wanted to reach millions, we

If we could manage integrations in Pakistan, with all its legacy systems and limitations, we can do it anywhere. That’s why we feel confident about Saudi banks and, in time, financial institutions beyond

Faizan Aslam, CEO of Bookme

looked at China and drew inspiration from WeChat and Alipay. Over time, we managed to onboard most of the banks in Pakistan and only then did we realize something surprising: banks in the rest of the world still didn’t offer the kind of services we had built inside Pakistani banking apps. Whether it was the GCC, Africa, or even Europe, those integrations simply didn’t exist. That realization opened our eyes to a much larger opportunity. What started as a scaling strategy in Pakistan has now become a blueprint we believe can transform digital transactions globally. And very soon, you’ll see Bookme taking this model into other parts of the world.”

Technology is another area where Bookme has worked quietly but ambitiously. The latest version of its app is more than just a booking tool, it is an intelligent platform that detects a user’s location through IP address and defaults its offerings to the country they are in. For a traveler arriving in Riyadh, the app automatically highlights Saudi inventory. For someone opening it in Karachi, Pakistani routes and services appear.

The move into Saudi Arabia has already taken concrete shape. Bookme recently partnered with flyadeal, the Kingdom’s budget airline. Even more significant is Bookme’s collaboration with Mrsool, one of Saudi Arabia’s most popular super apps with over eight million users. Known primarily as a delivery platform, Mrsool has been expanding into lifestyle services, and Bookme’s integration fits neatly into that model.

By embedding flight and hotel booking options inside Mrsool, Bookme gains access to a vast, digitally engaged audience, while Saudi users enjoy the convenience of managing deliveries and travel from a single application.

Another name on the table is Resal, another super app where early-stage collaboration is underway. Mrsool has just started to roll out Bookme services to Mrsool App users and in less than 2 weeks the entire Mrsool

customer base will have access to them. “These partnerships are at the beginning, but they represent the future of how services will be delivered,” Aslam observed.

Resal is a rewards company and very popular in Saudi Arabia. Each time a Saudi customer uses the Resal app, they accumulate points. With its integration in the Resal app, these points can be redeemed by purchases on Bookme.

Still, success in Saudi Arabia is not only about numbers. For Bookme, it is also about credibility. By demonstrating its ability to partner with major players in the Gulf, the company sends a clear signal to potential partners in other regions and that is part of the bigger story.

It is currently in the process of expanding into Africa as well. In fact one of the main benefits of moving into the Middle East is the region’s affinity with the African markets. The Middle East and Africa usually come in business discussions together. Being closer, when any of Bookme’s Saudi partners expand into Africa, they will automatically allow Bookme’s expansion into Africa. For now, Bookme is in the process of entering Africa by partnering itself with a massive global conglomerate. Announcement in this regard is expected soon. If played well, it will usher in an era of exponential growth for Bookme.

Numbers testify to this. Together with Pakistan. its new partnerships are expected to bring $20 million GMV this year for Bookme. In three years, this number is expected to reach the $100 million mark - a feat few startups are able to achieve.

For Pakistanis, this transformation is noteworthy. A decade ago, the idea of a local tech company competing in regional travel markets would have seemed fanciful. Today, Bookme is not only competing but positioning itself as a bridge between South Asia and the Middle East. The company’s new app, its partnerships with Saudi super apps and its proven ability to integrate with conservative banking systems all point toward a conclusion that Bookme is no longer just a national service but an international contender.

Bookme’s rise has attracted the attention of global heavyweights. At one point, Bookme received a buyout offer at a $100 million valuation cap from a global ride hailing giant. Tempting as the number was, the management of Bookme politely declined. If they had gone with the $100 million offer, a few years down the line, if the company had reached a valuation higher than $100 million, the acquirers would still have paid a $100 million price for the company. The company holds bigger potential than that, and Faizan’s instinct in this regard has played out in his favour.

The company has expanded abroad, quietly setting up operations in international markets, proving that its model can “travel”. And while Bookme was taking its model abroad, a new suitor stepped forward. A global travel powerhouse with deep pockets is currently in conversation with Bookme for an acquisition at a price north of $100 million this time.

For now, negotiations continue behind closed doors but one thing is certain: what began as a local ticketing service is no longer just a local story. It is a case study which attracts attention and intrigue. What began in Lahore as a ticketing solution has now become a platform that promises to reshape cross-border travel experiences. For a country still finding its digital footing, Bookme’s journey is a reminder that innovation often comes quietly but leaves behind sweeping change. Bookme’s foray into Saudi Arabia reflects both the promise and the challenges of Pakistani startups going global. While its strong user base and banking integrations give it credibility, the company will need to prove that it can thrive in markets where competition is sharper, margins are higher, and consumer expectations are uncompromising.

If Bookme can translate its local resilience into international agility, it may well set a precedent for Pakistan’s tech ecosystem to look beyond borders. If it struggles, however, it may also expose the limitations of models that work locally but stumble under global competition. n

a

akistan stands at a critical crossroads. Identified by the World Bank as one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change, the nation faces mounting environmental challenges that threaten its agricultural backbone and economic stability. Yet within this vulnerability lies unprecedented opportunity, a chance to transform Pakistan’s economy through sustainable business practices and green finance.

A comprehensive new report from ACCA (Association of Chartered Certified Accountants) and the Pakistan Business Council (PBC) reveals how the country can build a robust case for green business, turning climate challenges into competitive advantages through strategic sustainable investing and enhanced corporate reporting.

The numbers paint a stark picture. A Boston Consulting Group study estimates that by 2050, South Asia faces the highest climate risk exposure globally at 15% of GDP if current policies re-

main unchanged. For Pakistan specifically, this translates to a funding gap of 16.1% of GDP, significantly steeper than the global average, to achieve sustainable development goals.

“According to the World Bank Group, Pakistan is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change,” notes the report, citing factors including geographical diversity, exposure to climate hazards, and heavy dependence on agriculture and water resources.

This vulnerability in turn is driving innovation. The report reveals that 71% of surveyed Pakistani businesses already disclose environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information in some form, signaling widespread recognition that sustainability is no longer optional, it’s essential for survival and growth.

The economic argument for sustainable business is gaining strength globally, and Pakistan is well-positioned to benefit. McKinsey research highlighted in the report shows that products making ESG-related claims averaged 28% cumulative growth over five years, compared to 20% for traditional products. In emerging markets, consumer preference for sustainable

products appears even stronger.

The green energy sector exemplifies this opportunity. According to the International Energy Agency, the global green energy market could exceed $2 trillion by 2035, rivaling the crude oil market. For context, this goes beyond even the $1.7 trillion global fashion industry.

“Capital markets are an important conduit for connecting investments to businesses,” the report emphasizes, noting that publicly traded sustainable finance products reached $7 trillion globally in 2023, four times their 2018 valuation and representing 5% of the global bond market.

Perhaps no development is more significant for Pakistan’s green transformation than the recent adoption of international sustainability reporting standards. In January 2025, Pakistan’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SECP) announced the phased implementation of IFRS S1 and S2 standards for listed companies, beginning with reporting periods from July 2025.

This positions Pakistan among the global leaders in sustainability disclosure. The IFRS

Foundation reports that 30 jurisdictions representing 57% of global GDP have decided to use or are implementing ISSB standards.

“The value that transparent and standardised reporting brings to these companies is something which they have to realise as a business case for themselves,” observed a policymaker during the report’s research roundtable.

Pakistan’s policy framework for green finance has evolved significantly. The State Bank of Pakistan’s 2017 Green Banking Guidelines embed environmental considerations into the banking sector, while 2021 guidelines for green bonds provide frameworks for sustainable investment vehicles.

The report identifies a particularly promising avenue: the synergy between Islamic finance principles and sustainability goals. Over half the surveyed businesses cite Shariah compliance as a factor in investment decisions, suggesting untapped potential for Islamic sustainable finance products.

This alignment isn’t coincidental. Research by the CFA Institute and Principles for Responsible Investment shows that Islamic finance promotes ideas reflecting UN Sustainable Development Goals priorities, including equality, social justice, and shared economic prosperity.

Policy frameworks are already yielding results. In 2021, the Water and Power Development Authority issued Pakistan’s first Green Eurobond, raising $500 million for hydroelectric projects. The “Indus bond” attracted $3 billion in subscriptions, six times the target, demonstrating strong investor appetite for Pakistani green investments.

More recently, 2025 saw Pakistan’s first PKR-denominated green bond, the Parwaaz Green Action Bond, mobilizing Rs 1 billion for environmentally sustainable projects and becoming the first green bond listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

The transformation isn’t without obstacles. The report identifies key challenges including limited comparability across sustainability reports, preparation costs particularly for smaller

organizations, and the risk of greenwashing undermining stakeholder trust.

To address these issues, the report emphasizes four critical enablers for successful sustainability reporting: digital technology and AI integration, leveraging accountancy and finance professionals’ expertise, comprehensive capacity building, and enhanced collaboration across organizational departments.

“The roundtable session highlighted the continuing importance of training and development at all levels,” the report notes, pointing to Pakistan’s incorporation of sustainability education into director training programs for listed companies.

The report concludes with specific recommendations for three key stakeholder groups. Investors should demand stronger green finance policies, prioritize investments with tangible sustainability impact, and integrate climate risks into valuation models while holding businesses accountable for transparent reporting.

Businesses must prepare for mandatory sustainability reporting through capacity building and system upgrades, align strategies with Pakistan’s Green Taxonomy, and strengthen

internal collaboration to foster sustainable practices. Regulators should support capacity building for climate risk reporting, ensure independent assurance of sustainability reports, provide financial incentives for green investment, and expand green bond regulations.

The report paints a picture of a country ready to embrace its green transformation. With strong policy foundations, growing business awareness, and emerging success stories, Pakistan has the tools needed to turn climate vulnerability into competitive advantage.

“No one can do everything, but everyone can do something,” ACCA Chief Executive Helen Brand observed during the research process, a sentiment that captures both the collaborative spirit needed and the individual responsibility each stakeholder bears.

As Pakistan implements its National Economic Transformation Plan with its focus on sustainable development across multiple sectors, the timing couldn’t be better for this comprehensive roadmap toward green business leadership. The question isn’t whether Pakistan can afford to invest in sustainability, it’s whether it can afford not to.

The green business revolution in Pakistan has begun. The only question now is how quickly the country can scale it to meet the magnitude of both the challenge and the opportunity ahead. n

India’s economy relies heavily on the Gulf for remittances, trade, and oil. As the US pressures Modi to abandon Russian crude, Pakistan’s new relationship with Saudi Arabia could force the Indians to rethink their strategy on Pakistan

It is difficult to overstate the importance of this agreement. This is the first official mutual defence pact between two Muslim countries. Yes, there has been deep military cooperation within the Muslim world since modern nation states emerged after the second world war. But even at the height of the Ummah fervor of the 1970s no official agreement was signed declaring an attack upon one would be considered an attack upon the other. (Egypt and Syria did briefly form the United Arab Republic, but that lasted all of three years.)

By Abdullah Niazi

The Gulf Arab Countries are threatened. Nothing indicates this more than the speed with which the oil-rich leaders of the Arab world have been rushing to Pakistan for protection after Israel launched missile strikes on Doha. It barely took a week after the attack for Saudi Arabia, the beating heart of the GCC and Arab-American cooperation, to sign a mutual defence agreement with Pakistan.

The defence pact is probably Pakistan’s most significant military and diplomatic initiative of the past half century.

It is important enough that even the leadership of the Pakistan Tehreek i Insaaf, one of the largest parties in the National Assembly, has come out in support of it. For anyone that has been watching Pakistani politics since 2023, that alone signifies how important this pact is. It is an achievement that has a mandate and is being widely celebrated not just in Pakistan but also in Saudi Arabia and, to a lesser extent, in other parts of the Muslim world.

The alliance will also be closely watched

by the rest of the world. Already Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have indicated that they would be more than open to other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members either joining their pact or signing similar agreements with Pakistan. Perhaps no country will be watching this more closely or with more trepidation than India. It has just been over four months since India launched attacks into mainland Pakistan, launching a four day military engagement that was only stopped by the intervention of the Trump Administration.

The Indians, to their detriment, learned that Pakistan can put up a fight. That lesson was the only thing they walked away with from the conflict. But India’s concerns about Pakistan’s defence pact with Saudi Arabia will not be military. It will be economic. Pakistan has proven it is capable of defending itself from Indian hostility. The true strength of this pact for Pakistan will not be Saudi jets or military assistance but rather the economic pressure Saudi Arabia and indeed the larger Gulf region can exert upon the Indians.

And when it comes to the Indian economy, the Gulf Arab States have considerable leverage.

This is the single most important military and diplomatic initiative in the past 50 years, after the Lahore Islamic summit. It is the first defence deal between two muslim countries, and Saudi Arabia is not just any muslim country but one of the richest countries in the world, with a strong diplomatic influence

Mushahid Hussain, former senator

The role of the Gulf countries in the Indian economy is massive. The GCC is India’s single largest trading partner with volumes of $161.23 billion in 2024 according to India’s Ministry of Commerce. India actually maintains a trade deficit with the GCC largely because they are dependent on Gulf crude for their oil supply.

India’s second largest trading partner is the EU, but the single country with which they have the largest trade partnership is the United States. In 2024 India’s total goods exports to the United States were over $88 billion and their total imports were just over $43 billion. India’s relationship with both the GCC and the EU can only be described as stable. The relationship with the United States has been more troublesome. For months now President Trump has been attempting to strong-arm the Modi government, hitting them with a 25% tariff across all goods. The Indians have been scrambling to fix this problem ever since. One of the overtures they have been making is to cut down on their imports of Russian oil.

India’s trade relationship with Russia is fascinating and relatively new. Russian oil accounted for barely 2% of India’s total crude imports before 2022. Then came the Ukraine war. The EU and the United States sanctioned Russia. This left Russia without a market to sell its crude to. India has been filling that gap. In the year 2024-25, Russian crude made up 35% of India’s total crude oil imports with India importing 1754 barrels of Russian crude a day.

These imports have been serving India well. In 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine and the world hit them with sanctions, the global prices of oil shot up. India, the world’s third biggest oil consuming and importing nation, spent $119.2 billion in 2021-22 , up from $62.2 billion in the previous fiscal year, according to data from the oil ministry’s Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell (PPAC). This means India’s crude oil import bill nearly doubled as energy prices soared globally following the

return of demand and war in Ukraine. Oil from Russia has helped ease some of this inflationary pressure.

The second largest source of crude for India is Iraq, which provides around a thousand barrels a day. India has long looked for strategic partners to provide it with cheap oil. Imports from Iraq also increased exponentially after the 2003 invasion when Iraq had been ravaged by the Bush-Blair project.

But the GCC is no small player in this. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE combined provided more crude oil to India than even Iraq at nearly 1200 barrels a day. For all intents and purposes India’s oil supply is currently divided between three players: Russia, Iraq, and the GCC. While this has worked well for them in the past three years, India’s dependence on Russia is proving to be a vulnerability.

With US tariffs weighing heavy on them, President Trump has been insisting no tariffs will be eased on any countries continuing to

buy Russian oil until a ceasefire is achieved in Ukraine. While India has resisted pressure on this topic, last month, their state refineries stopped buying Russian Crude. India is increasingly feeling the pressure to switch from Russian oil. The switch will have to be towards the Gulf. Historically, the Middle East has been India’s biggest supplier and if Russia is out of the equation they will have to go back to buying more from the GCC.

“India

Place all of this information in context and India emerges in a delicate position. The Modi Administration reacted to increasing global oil prices by buying cheap Russian oil. The Americans are not having it anymore. Unless India stops buying crude from Russia the United States, which is their biggest trading partner, will double down

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have long shared a security-partnership and trade relationship. Pakistan has helped Saudi Arabia militarily for many decades now. Most people know that Pakistani SSG Commandos participated in lifting the siege of Makkah in 1979, but that was not where the cooperation ended. Tens of thousands of Pakistani troops remained in Saudi Arabia during the Iran-Iraq war, with most recalled in 1988, though a smaller contingent stayed. In 2015, Pakistan’s parliament rejected Saudi’s request for troops in Yemen, but the relationship remained intact. Pakistan still provided some naval support, and both countries held joint military exercises. Former Pakistani Army Chief Raheel Sharif later led the Saudi-led Islamic Military Alliance, and Saudi troops participated in Pakistan’s 2017 Day Parade. In February 2018, the Pakistani military sent a brigade to Saudi Arabia.

This latest defence pact is the formal declaration of the relationship the two countries have maintained over the years. Its timing is meant to be a signal to Israel.

For their part, the Saudis are also pulling out all the stops. The visuals of the Prime Minister’s aircraft being escorted by Saudi fighter jets upon entering the Kingdom’s airspace have gone viral for a reason: such protocol has been unheard of before this. It became immediately clear why this was the case when the two leaders signed an agreement of mutual defence. Very simply put, the agreement binds Pakistan and Saudi Arabia to act in each other’s defence. An attack on one is to be treated as an attack on the other.

on 25% tariffs against Indian products. The only option the Indians have is to turn once again to the GCC. Historically, they have had a very good relationship with the Gulf, but Saudi Arabia has just signed a defence pact with Pakistan.

“India is in a state of shock, they are taken by surprise,” says former Senator Mushahid Hussain in a recent interview. “This is the single most important military and diplomatic initiative [by Pakistan] in the past 50 years, after the Lahore Islamic summit. It is the first defence deal between two Muslim countries, and Saudi Arabia is not just any Muslim country but one of the richest countries in the world, with a strong diplomatic influence,” he explains.

The current scenario has very much been shaped by the United States economic policy. The Trump Administration is unique in American history. Its foreign policy objectives have been similar to those of previous administrations. Trump wants an end to expensive wars, he has unequivocally supported Israel, and despite fears that he would be an isolationist, he has maintained the American appetite for global domination. His approach to achieving these goals, however, has been significantly different. Trump has been far less trigger happy

The United States’ role as a security guarantor has come under scrutiny as of late, and its credibility has been severely damaged

Maliha Lodhi, former permanent representative of Pakistan to the UN

than even his democratic predecessors, particularly the Obama Administration. In his last year in office, President Obama dropped nearly 27,000 bombs in over seven countries including Pakistan. And this was at a time when the drone attacks were winding down.

President Trump, on the other hand, seems more interested in throwing America’s economic weight around to get his way. The gravitational pull of the United States economy can be as potent a threat as its military might. He has been able to wield the threat of economic ruin to stop, as he claims, six wars in six months including between nuclear armed India and Pakistan.

The one situation he has not been able to wrangle has been Israel’s brutual attack on Gaza, which is now being described by the United Nations as a genocide on four counts. So much so that it has not been able to protect allies like Qatar from direct Israeli attacks.

Trump’s inability to control Israel is what has put Saudi Arabia firmly in Pakistan’s camp. “The United States’ role as a security guarantor has come under scrutiny as of late, and its credibility has been severely damaged,” says Maliha Lodhi, former permanent representative of Pakistan to the UN. “At this point, it is clear that Pakistan has taken up the role of a security provider, not just for Saudi Arabia but for the Middle East. It is important to take into consideration the timing and the context of this agreement, since in the aftermath of Israeli aggression against Qatar, Arab countries have started to look elsewhere for security guarantees,” she said in an interview.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was the first Pakistani leader to really try and position Pakistan as a defender of the Muslim world. The historic OIC summit held in Lahore in 1974 was an important moment in this positioning. This was the first time the leaders of Pan-Arabism were joining with the Muslim countries of Asia and North Africa to try and revive the concept of the “ummah.” It was a historic pipe-dream that has never come to fruition. Even though your friend from college that joined the Jamat Islami might tell you a common Islamic currency or even a joint army was right on the edge of creation when Zia ul Haq’s plane came crashing down, this was never the case. Nawaz Sharif’s plans to be known as “Amir ul Momineen” also never really caught on. But even as the Arab World drifted away from the idea of Muslim unity, it did not stop Pakistan from positioning itself as the muscle of such a unified front.

This offer of protection has been at the heart of Pakistan’s relationship with the rest of the Muslim world, particularly with the Gulf. It is part of the reason Pakistan survived the

Pakistan has always used the term ‘strategic assets’ for its nuclear & missile programs. Most likely, Pakistan will now be able to buy US weapons it needs, with Saudi money, which the Trump administration seems willing to sell

Hussain Haqani, former Ambassador to the US

possibility of default in 1999. When the US imposed sanctions on Pakistan following the nuclear tests, the Saudis kept rolling over money we owed them for oil shipments and eventually wrote them off for all intents and purposes. It is why the Gulf states have regularly bailed Pakistan out one economic crisis after the other. On some level it has been understood that when push comes to shove, the Gulf will be able to call upon Pakistan.

That is the debt Pakistan is now returning, and it seems the leadership is cognisant of exactly what they have promised Saudi Arabia and what they want to promise the rest of the Gulf. According to Hussain Haqani, former Ambassador to the United States, the terms ‘Strategic Mutual Defense Agreement’ implies that the treaty covers nuclear and missile defence. “Pakistan has always used the term ‘strategic assets’ for its nuclear & missile programs,” he says. “Most likely, Pakistan will now be able to buy US weapons it needs, with Saudi money, which the Trump administration

seems willing to sell.”

Pakistan must not be under any illusions. This agreement with Saudi Arabia is not some sort of Ummah pact. In fact, it would not be a stretch to say the concept of the Ummah no longer exists among the leadership of the Muslim world. Palestine has always been the core issue that has united the Muslim World. Pakistan wanted Kashmir to be a similar issue. The Arab states have adopted a policy in both cases of doing business with India and Israel while giving diplomatic support to the Palestinians and the Kashmiris. If any desire for a united Muslim front was possible, it would have been mobilized in the defence of the Palestinian people.

What we have in the shape of the Pak-Saudi Defence Agreement is the cementing of Pakistan’s position as the defender of the Gulf. It will complicate our relationship with Iran, but all in all it is a cause for confidence in Pakistan.

There are many benefits to Pakistan from the agreement with Saudi Arabia. The Saudis will now be more invested than ever in Pakistan’s economic stability. Pakistan also has deep interests in the security of the Gulf considering how many Pakistanis have property parked in the UAE and the amount of remittances that workers send back home from the Gulf countries. Pakistan is also a big importer of oil as well as gas from the GCC.

It is not unimportant in this context that Israeli officials have been mentioning Pakistan by name through different diplomatic channels. The country’s main defence of their attack on Doha was to point towards the US opera-

imports

tion in Abbottabad which found and killed Osama Bin Laden. Pakistan’s representatives to the UN have been responding robustly to such claims. However, it is clear that Israel is baiting Pakistan on some level. The impunity with which Israel has successfully operated will only embolden them further. That is why the Gulf Arab states are looking to diversify their security guarantees.

The biggest benefit, however, will be how this affects Pakistan’s relationship with India. India does not just rely on the GCC for oil.

“With India’s markets in the US and Europe clouded by possibilities of higher tariff walls and other issues, New Delhi possibly needs to think afresh to renew its engagement with the Gulf countries. This zone, which has witnessed significant growth in recent years due to its geographical proximity, complementary economic structures, and shared interests in technology and innovation, promises new trade growth possibilities,” write D Dhanuraj, Chairman of Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR) in India, and Gazi Hassan, a Research Scholar of International Politics, in a joint article for The Secretariat.

well-thought-out FTA is the need of the hour, which will solidify the partnership, unlocking new opportunities for mutual economic growth. Additionally, the nine-million-strong Indian expatriate community forms the backbone of the GCC’s labour force, particularly in construction, healthcare, and IT.”

“Amid global trade uncertainties, India needs to up its game in the GCC zone. A

India’s current position in the world requires that they not just maintain their relationship with the GCC but expand. At such a moment, India’s great rival has signed a mutual defence treaty with the beating heart of the GCC, Saudi Arabia, with other GCC members indicating their interest in signing similar agreements. What will Modi do in this scenario? His rhetoric before, during, and after the military conflict in May indicates his opinions on Pakistan are unlikely to change any time soon. Besides, hoping for better ties or trade between the two countries would be too much to ask for from the BJP government. What we can hope for is quiet. If the treaty with Saudi Arabia can convince India to simply not engage with Pakistan militarily, that will be enough. The true success of this agreement will be if it is not tested in the first place. The hope from both Saudi Arabia and Pakistan will be that the agreement will be enough of a deterrent for both India and Israel. However, if push comes to shove, both countries must remember that the first instance where one is harmed will be crucial. If Saudi Arabia is attacked, for example, a rapid response from Pakistan will let the world know this partnership means business. n

Even before the floods hit the country, Millat’s revenues and profits were drowning

Millat Tractors Limited

(PSX: MTL) has posted one of its most difficult years in recent memory.

For the financial year ended 30 June 2025, unconsolidated net sales fell to Rs52.1 billion, down 43.0% from Rs91.5 billion the previous year, as demand for farm machinery softened across the country. Profit after tax slid 38.0% to Rs6.37 billion, with earnings per share at Rs31.9. The company did keep a tight hold on costs and pricing – its gross margin rose to 26.6% from 23.4% – but that improvement could not offset the shock to volumes and revenues. These figures are taken from the company’s statutory filing to the Pakistan Stock Exchange, where the statement of profit or loss sets out the declines in revenue and

profit clearly.

Brokerage analysis helps explain the mechanics of the downturn. According to Arif Habib Ltd (AHL), Millat sold 18,580 tractors in FY25, down 38.0% from 30,203 in FY24. In a note issued to clients, Arif Habib Ltd’s analysts highlighted an industry wide trough in orders, even as the company eked out a stronger gross margin on the back of pricing, mix and procurement discipline.

The pain was visible quarter to quarter. In 4QFY25, revenue fell 45.0% year on year to Rs12.1 billion and slipped 3.0% quarter on quarter as volumes contracted to 4,062 units (down 43.0% year on year and 8.0% sequentially). Gross margin for the quarter softened to 25.0% (from 28.3% in 3Q), a reminder that fixed cost absorption becomes harder when the assembly line slows.

What makes the year more sobering is timing. The revenue collapse unfolded before

Pakistan’s latest monsoon devastation hammered the farm economy in July and August. OCHA’s situation reports and UNICEF’s September update describe Punjab’s worst flooding in decades, with all three major rivers – Sutlej, Chenab and Ravi – running exceptionally high, millions affected and large swathes of cropland inundated. The Associated Press reports 2.6 million people displaced in Punjab and 2.5 million acres of farmland damaged. In other words, Millat’s FY25 contraction came ahead of a climate driven shock that could further weigh on mechanisation budgets in the months that follow.

Even in the gloom, a couple of line items show managerial response. The company trimmed distribution costs year on year, kept administrative expenses in check relative to inflation, and lifted cash generation to support the dividend. AHL’s exhibit shows distribution expense down 14.0%, other expenses down

23.0%, and an effective tax rate easing to 21.0% from 39.2%, cushioning part of the operating hit. Still, profit before tax halved to Rs8.06 billion, an unambiguous reflection of the sales drought.

Millat’s story is inseparable from the history of agricultural mechanisation in Pakistan. Founded in 1964 (as Rana Tractors and Equipment) to import and market Massey Ferguson tractors, the company began assembling tractors from semi knocked down kits by 1967. Following the 1972 nationalisation drive, the enterprise – renamed Millat Tractors Limited – worked under the Pakistan Tractor Corporation to assemble and market tractors from completely knocked down kits. By 1982, Millat had inaugurated the country’s first tractor engine assembly line, expanding machining capacity by 1984 to localise critical components.

The pivot that defined the modern company came in 1992, when Millat was privatised through an employee buyout, followed by the inauguration of a new assembly plant and a deliberate strategy of deep localisation supported by a cluster of allied companies. The group’s structure built resilience – Bolan Castings for foundry needs, Millat Equipment for gears and shafts, and Millat Industrial Products for batteries – reducing import dependency and enabling cost control. The company’s own corporate and annual report timelines track these milestones, from the licensing arrangement with AGCO (Massey Ferguson) to investments in quality systems and energy efficiency.

Today, Millat is based near Lahore and is one of the two dominant tractor manufacturers in Pakistan, operating under a licensing arrangement with AGCO for the Massey Ferguson brand. Over decades, the company has combined assembly with component manufacturing and vendor development to achieve localisation levels often cited above 90.0% on several models, a point underscored by industry coverage and analyst briefings. The strategy has delivered scale in good years and a cost buffer in bad ones.

From the investor’s perspective, Millat is a long standing industrial name whose fortunes rise and fall with farm incomes, credit availability and public programmes to promote mechanisation.

The backbone of Millat’s revenues is a stable of Massey Ferguson tractors spanning roughly the 50–85 horsepower range, with two wheel and four wheel drive variants positioned for different crop belts and haulage needs. Familiar model names – MF 240, MF 260, MF 350 Plus, MF 360, MF 375 and MF 385 – make up much of the installed base, with extensive parts availability and a network of dealers and workshops. The company’s own spare parts portal and product guides list model wise parts, implements and attachments, under-

scoring how the after sales ecosystem supports the brand.

Beyond tractors, Millat has long sought to diversify by offering forklift trucks (under a licensing arrangement), diesel engines, diesel generator sets, and a range of allied agricultural implements. Company materials and mainstream press describe this wider portfolio, which provides counter cyclical niches in construction, warehousing and power backup even when tractor sales are soft. The group’s engineering arms – Millat Equipment and Bolan Castings – feed the tractor line while also giving the company industrial heft.

The power solutions line has become more visible in recent years, with Millat promoting diesel generator sets for industrial and commercial clients. While the power business does not approach tractors in scale, it rounds out the product mix and keeps workshops utilised when agricultural demand is weak. The official product pages highlight the offering and service support, positioning it as a reliability play in an economy where grid instability remains a fact of life.

Exports – mainly of tractors and components – are now a defined, if still modest, part of the mix. Company and media statements through FY24 pointed to 2,500–3,000 units exported to destinations such as Afghanistan, Africa and parts of the Middle East, with official communications celebrating an FY24 milestone of $17 million in tractor, engine and component exports. That push both validates local manufacturing quality and gives Millat a lever that is less tied to Pakistan’s farm cycle.

If FY24 showcased a recovery, FY25 was a stress test – one that is shaping Millat’s current strategy on several fronts.

Millat’s long running localisation drive – frequently cited above 90.0% on many models – remains the first line of defence when exchange rate swings and import bottlenecks threaten margins. Analyst briefings last year connected the dots between localisation, vendor development and resilience, noting how the company’s in house machining and the group’s foundry and gear making arms help stabilise costs. The stronger 26.6% FY25 gross margin alongside a bruising fall in volumes suggests pricing power and localisation combined to cushion, but not eliminate, the pain.

A pivotal step in late 2024 was the merger of Millat Equipment Limited into Millat Tractors, approved by the Competition Commission of Pakistan. Strategically, the move folds a key supplier – gears, shafts, hydraulic pumps – into the parent, promising procurement synergies, shorter lead times and a cleaner capital structure. In a low volume year, those micro efficiencies matter.

The company continues to lean on non tractor lines – generators, forklifts, implements

and spares – to ensure workshops, dealers and service technicians remain engaged even when farmers delay tractor purchases. The company’s own site and press coverage reinforce this multi product posture as central to smoothing cash flows and maintaining channel health through the cycle.

Millat’s parts portal and product literature illustrate the depth of its after sales franchise. In a downturn, parts and service keep dealers solvent and sustain brand equity in rural markets. That infrastructure will be central to any FY26 recovery, especially as flood affected districts repair equipment and resume fieldwork.

Tractor demand in Pakistan is acutely sensitive to credit conditions, input prices and public programmes. The Punjab Green Tractor Scheme, which ran a first phase in late 2024 and opened Phase II registrations in mid August 2025, can lift near term orders for qualifying models – but the monsoon flood emergency complicates delivery schedules and farmer cash flows. Government portals and notices confirm Phase II’s launch and balloting, yet the humanitarian situation across farm districts may delay actual purchases. For Millat, execution will mean aligning production slots and dealer financing with the pace of subsidy disbursements and post flood rehabilitation. FY25 ended on 30 June, before the full force of the monsoon crisis. OCHA and UNICEF report widespread devastation through July–September, with Punjab enduring some of its worst flooding in decades and millions affected nationwide. AP’s field reporting underscores the agricultural toll – homes and 2.5 million acres of farmland damaged. For a tractor maker, that means a complex near term demand path: some farmers delay capex to rebuild, while others may require new equipment to replace damaged assets once relief and credit arrive. Millat’s response – ranging from after sales support in flood hit districts to flexible production planning – will be decisive.

Where does that leave investors and industry watchers? With a pragmatic checklist. Watch the cadence of Punjab’s Green Tractor disbursements and the pace of rehabilitation across flooded districts. Track how Millat integrates Millat Equipment and whether those synergies show up in working capital and margin lines. And look for signals that farmer sentiment is stabilising – harvest linked cash flows, input price relief, and improving credit availability.

For now, FY25 reads like an annus horribilis for Pakistani farmers and the companies that serve them. Millat’s task is to ensure it is also a turning point, not a lasting trend. Its long history suggests it knows how to endure; the next few quarters will show whether it can also rebound. n

Net income fell 19% due to a combination of falling production and falling prices

Pakistan Petroleum Ltd (PPL) has posted a weaker set of full‑year numbers after a year marked by falling field output and softer crude prices – an uncomfortable combination for an upstream com‑ pany that earns on barrels and molecules lifted. For the twelve months to 30 June 2025, profit after tax fell 19.0% to Rs92.0 billion, translat‑ ing into earnings per share of Rs33.8 versus Rs42.0 a year earlier. Full‑year sales slipped 16.0% to Rs242.5 billion as both oil and gas production nudged lower across the portfolio. The company paired its announcement with a fourth‑quarter cash dividend of Rs2.5 per share, bringing the FY25 payout to Rs7.5.

The core operational story is straight‑ forward: production declined. PPL’s average oil output fell 10.0% to 10.2 k barrels per day, while gas output also dropped about 10.0% to 480 mmcfd. Layer on a weaker crude tape –Arab Light averaged $75.8 per barrel in FY25 against $87.0 in FY24 – and the top line was always going to be under pressure. Nash eed Malik, an analyst at Arif Habib Ltd, an investment bank, attributes the 16.0% revenue contraction largely to this dual hit of lower volumes and lower prices, a pattern that is also

evident in 4QFY25, when revenue fell 19.0% year‑on‑year and 19.0% quarter‑on‑quarter to Rs51.8 billion.

Margins narrowed as fixed costs met fewer produced units. Gross margin for FY25 slipped to 62.6% from 65.6%, with 4QFY25 clocking an even lower 57.4% as output soft‑ ness accelerated into year‑end. Management contained parts of the cost base: exploration expense fell 18.0% to Rs15.7 billion for the year and was down 43.0% in the fourth quarter, helped by the absence of a dry well charge that hit the comparable period last year. Even so, the operating decline was steep enough to drag profit before tax down 13.0% to Rs139.1 billion.

The balance‑sheet picture underscores the tightrope PPL continues to walk between investing for the long term and marshaling cash in the near term. Trade receivables –largely the energy sector’s chronic payables to upstream producers – stood flat at roughly Rs592.4 billion at year‑end versus the previous quarter, a reminder that circular‑debt dynam‑ ics still bind. Cash and short‑term investments totalled about Rs80.0 billion, down from Rs112.0 billion twelve months ago, a decrease Malik, the analyst at Arif Habib Ltd, attributes primarily to a Sui lease payment. Put different‑ ly, liquidity that could have gone to the drill bit or compression projects was partly diverted to

unavoidable obligations.

Quarterly dynamics offered a small silver lining. 4QFY25 EPS of Rs7.1 was 8.0% higher year‑on‑year, even as it fell 11.0% sequentially, suggesting that treasury income and a lighter exploration charge helped the bottom line relative to last year’s fourth quarter. But the sequential decline – aligned with the 19.0% quarter‑on‑quarter drop in revenue – speaks to the near‑term challenge of coaxing more output from ageing domestic fields while the price deck remains middling.

The result in one sentence: FY25 was not a bad year for costs, but it was a poor year for barrels and molecules – and that is what ultimately shows up in profits.

PPL is one of Pakistan’s oldest industrial names, a company whose identity is insepara‑ ble from the discovery and long stewardship of Sui, the gas field that underwrote the coun‑ try’s first great wave of urban and industrial growth. It began life in the early years after Independence as a stewardship vehicle for exploration in the country’s onshore basins, and over seven decades has evolved into a state‑controlled, publicly listed operator that straddles Balochistan, Sindh, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with a portfolio of producing fields, development projects and exploration leases.

That dual identity – majority gov ernment‑owned, yet answerable to public shareholders – has shaped PPL’s operating philosophy. On the one hand, it carries a public mandate: keep gas flowing from mature reservoirs that still serve as the backbone fuel for households, fertiliser and industry; keep investment steady in basin‑opening prospects whose rewards, if they come, are social as much as financial. On the other hand, it is assessed on private‑market metrics: production growth, reserve replacement, unit operating costs, dividend policy, and the ability to turn a rupee of sales into cash, rather than an IOU trapped in the power‑and‑gas receivables maze.

The company’s portfolio reflects those tensions. Much of PPL’s output today comes from brownfield assets – long‑producing gas fields with natural decline curves that can be mitigated but not eliminated. The engineer ing toolkit is familiar to upstream operators worldwide: workovers, infill drilling, artificial lift, compression, and increasingly, enhanced recovery techniques adapted to the geolo‑ gy of Pakistan’s onshore basins. Alongside those efforts runs a pipeline of near‑field and step‑out exploration prospects that aim to add incremental molecules close to existing infra structure. The advantage of such prospects is speed to market and capital efficiency; the risk is that they rarely deliver the material uplift that resets a decline trajectory.

As a company, PPL is also a deeply Pakistani institution. The workforce pipelines talent from engineering schools in Lahore, Karachi and Quetta into field postings in often remote districts. Corporate social responsibil ity spending tends to be concentrated in host communities around producing assets, with a focus on health, education and livelihoods – a pragmatic approach that reduces friction and, in some districts, improves security conditions for field operations. The company’s base in Ka‑ rachi keeps it close to regulators, offtakers and capital markets, but its operational heartbeat is inland, where the wells are.

Financially, PPL’s dividend posture has always been a calibration between cash generation and the realities of the energy value chain. FY25’s Rs7.5 payout was higher than last year’s Rs6.0, an increase that speaks to the cushion provided by other income even as operating performance slipped. But until production turns, payout growth will continue to be a function of treasury returns and the pace at which trade debts are monetised. Trade receivables of Rs592.4 billion show how accounting profit can diverge from cash in the energy complex.

To understand PPL’s FY25, it helps to situate it in a national exploration context. Pakistan’s onshore gas system is mature. The big, basin‑defining discoveries of the last

century have been on decline for years. Around them, a constellation of smaller fields has provided incremental supply, but rarely the kind of volume pulse that can keep national output flat, let alone growing, for long. Against that backdrop, FY25’s 10.0% drops in oil and gas production at PPL are not an anomaly –they are a sharp expression of a broader trend across the upstream sector.

In such a world, the health of the explo‑ ration and development pipeline becomes de‑ cisive. PPL’s exploration expense fell 18.0% in FY25, and 43.0% in the fourth quarter, thanks in part to the lack of a dry‑well charge that had burdened the previous year’s quarter. That is good news for the income statement but can be a warning for the reserve‑replacement equation if sustained for too long. The company’s note does not imply that drilling has stopped; it implies that the mix shifted to lower‑risk, low er‑cost activity in the period and that dry‑well risk did not crystallise in 4QFY25 the way it did last year. The challenge will be to lean back into a drilling calendar robust enough to add new barrels and molecules at pace.

Industry‑wide, operators – PPL, OGDCL, Mari and a handful of smaller private players –have been emphasising near‑field exploration and appraisal as the quickest route to mar ketable volumes. In practice, that has meant step‑outs from known reservoirs, recomple tions to tap bypassed pay, and – where geology permits – fracture stimulation programmes to coax more gas from tight sands. The trade‑off is familiar: near‑field prospects carry high‑ er technical success rates but rarely deliver step‑change volumes; true frontier exploration tends to be capital‑ and risk‑heavier and, in Pakistan’s onshore basins, has not produced a basin‑opening discovery in years.

Then there are the cash constraints. The upstream sector’s working capital is entwined with the power and gas value chains via circular debt, which delays cash collection from offtak‑ ers. PPL ended FY25 with trade receivables of roughly Rs592.4 billion. That is not just an accounting curiosity; it is real cash that cannot be deployed to fund an ambitious drilling slate, to book drilling rigs for longer campaigns, or to invest in compression and gathering infrastruc ture that can sustain plateau levels in maturing fields. In this sense, other income’s 42.0% uplift to Rs24.2 billion – thanks to short‑term invest ments that reached Rs74.2 billion mid‑year – is a double‑edged sword: it shows treasury acu‑ men, but also the absence of enough immediate, high‑return projects to absorb that cash in the field at acceptable risk.

Another cross‑current is price. FY25 saw Arab Light averaging $75.8 against $87.0 the year before. For crude‑linked barrels, that is a direct hit to revenue. For gas, pricing is governed by policy formulas and contracts

that have periodically been revised to improve investor returns, particularly for tight and deep fields. Policy efforts do matter; they can tilt economics enough to green‑light prospects that would otherwise stay on paper. But policy cannot repeal geology or the time it takes to drill, complete and hook up wells in challeng ing terrains.

An often overlooked trend in Pakistan’s upstream is the quiet shift in portfolio eco‑ nomics. As mature gas declines and domestic demand stays high, the energy system leans more on imported LNG to bridge the gap. That raises the value (and the urgency) of domestic molecules, but it also sets a reference price that can skew policy debates around gas pricing for new discoveries. PPL and its peers have argued – sometimes publicly, more often in rooms with regulators – that a predictable, bankable price framework for tight, deep and offshore gas is essential if the country wants explora‑ tion risked and funded at scale. That argument is unlikely to fade in FY26.

Finally, there is the spectre of one‑off hits. FY24’s fourth quarter carried a dry‑well charge; FY25’s did not. Exploration is lumpy by nature; a quarter that looks clean can be fol‑ lowed by one with substantial write‑offs. The art for management is to smooth the drill‑bit enough that successes and failures distribute across quarters and the income statement does not whipsaw investors. The 4QFY25 exploration cost of Rs4.1 billion, down 43.0% year‑on‑year, shows what a quarter without a dry‑well looks like. It should not be mistaken for a new normal.

PPL’s FY25 is a study in how unforgiving upstream arithmetic can be. Oil at USD 75.8, gas at 480 mmcfd, and oil at 10.2 k barrels per day – all down from the previous year – flowed into a 16.0% revenue drop and a 19.0% fall in earnings, even with other income doing heavy lifting. The dividend nudged higher to Rs7.5, a signal of confidence and a nod to treasury gains, but the company’s equity story remains what it has always been: production.

There are positives to build on. Costs were controlled. The exploration line was lighter. Cash still sits on the balance sheet even after the Sui lease outflow. But the trade‑debt overhang of Rs592.4 billion is a structural constraint, and the geology of Pakistan’s ageing onshore fields is indifferent to good intentions. If FY26 is to look different, it will be because PPL slows declines in its base, executes a denser near‑field programme, and – if policy and partners align – takes intelligent shots at prospects with the potential to move the company’s needle.

Until then, the most important sentence in the FY25 report remains the plainest: pro duction was lower. For an upstream company, there is no more consequential line of text.

Net income rose to record levels even as Kia and Chinese automakers gained a significant foothold in the market

Indus Motor Company (IMC), Toyota’s publicy listed arm in Pakistan, has delivered the most profitable year in its history – despite a dramatically more crowded forecourt. For the year ended June 2025, profit after tax surged to Rs23.0 billion (EPS Rs292.7), up 53.0% year on year, while the board signed off on the company’s highest ever dividend at Rs176.0 per share. Even with South Korean and Chinese nameplates now firmly embedded in showrooms – and nibbling at niches from subcompact SUVs to pickups – Toyota’s Pakistan business expanded margins and volumes to close a record year.

The operational gears all turned the right way. Net sales climbed 41.0% to Rs215.1 billion, and operating profit more than doubled to Rs25.3 billion, as the gross margin improved to 15.0% from 13.0% a year earlier. EBITDA was up 84.0% to Rs31.5 billion, and net margin a full percentage point better than FY24. Profitability in the second half of financial year 2025 was materially stronger than the prior year half, underscoring that the step up was not confined to a single quarter.

Volumes were the story behind the story. Including both completely knocked down (CKD) and completely built up (CBU) units, Toyota’s shipments in FY25 grew 60.0% to 33,757 vehicles, outpacing an auto market that rose 40.0% to 223,799 units. In other words, Toyota did not just ride a cyclical upturn; it took share in the recovery. That achievement matters because the market it faced in FY25 was unlike any of the preceding five years –Kia entrenched in passenger cars, a clutch of Chinese SUV and pickup entrants, and an on again off again wave of used imports. Against that backdrop, Toyota still delivered its best year on record.

Management has been frank that tailwinds could fade. Flood damage across wide

swathes of the country will likely dent demand in coming months, and any liberalisation of used car imports – extending the permissible age from three to five years and allowing commercial imports – would pressure local assemblers. IMC warned that such a policy would risk “de industrialisation”, prompting a rethink of the local assembly model in favour of imports if the economics turned unfavourable. The caution is not idle; the company is preparing operational efficiency measures to defend margins if volumes soften.

Still, the record year affords financial resilience. The 2HFY25 EPS of Rs166.1 – versus Rs128.7 a year earlier – suggests momentum that can absorb shocks. The product mix also helped: within the combined Yaris/Corolla portfolio, Yaris accounts for about 70.0% of units and Corolla 30.0%, while institutional sales of all models are roughly 10.0% – a base of fleet demand that tends to be less rate sensitive than retail. That mosaic of buyers, from middle income city families to corporate and government fleets, cushioned the year’s ups and downs in affordability.

For shareholders, the headline is simple: record earnings, record dividend. For the industry, the subtext is more complicated: Toyota proved in FY25 that scale, distribution and a disciplined product cadence can trump the sheer novelty of new badges – at least for now.

Toyota’s presence in Pakistan is channelled through Indus Motor Company, a publicly listed joint venture assembler and marketer that has spent more than three decades localising production, deepening vendor capability and building a dealer network that reaches well beyond the big cities. The company’s identity is often reduced to its flagship Corolla, but in truth Toyota’s local portfolio now spans multiple price points and use cases: Yaris for the mass urban buyer; Corolla for families and fleet; Hilux for agricultural, construction and security customers; Fortuner

for the premium SUV bracket; and the Corolla Cross to bridge the SUV leaning middle. That multi segment footprint – anchored by robust after sales support – has been central to Toyota’s staying power through cycles of currency stress, rate spikes and policy zig zags.

Critically, Toyota’s model in Pakistan has not been to import and sell, but to assemble and localise. Management’s most recent briefings place localisation at around 60.0% for Yaris, Corolla and Corolla Cross, and 40.0–45.0% for Hilux and Fortuner – a candid acknowledgement that larger, lower volume ladder frame vehicles are harder to localise fully. Local content at these levels matters because every sharp rupee slide raises the cost of imported kits; each incremental domestic component softens that blow. It also feeds a broader industrial ecosystem of stampers, moulders and machinists that rises and falls with auto sector health.

The company’s public comments over the past year also show a manufacturer that sees itself as a stakeholder in policy outcomes. On the National Tariff Policy (2025–2030), for example, IMC has warned that a cut in CBU tariffs to 15.0% would make local CKD assembly uneconomic, forcing a pivot to imports. Whatever one’s view on consumer welfare and competition, the industrial calculus is straightforward: if tariff and tax structures reward imports over assembly, investment in tooling and vendor development will ebb. Toyota’s messaging has been that a vibrant local industry – competing against new entrants and imports alike – needs a predictable policy spine.

The upshot is a brand whose local history is as much about industrial habit as it is about consumer trust: invest in local parts where volume and tooling justify it; defend price and residual value with strong after sales; and keep the portfolio refreshed enough to meet the buyer where tastes are drifting.

The topline of FY25 was unmistakable:

Toyota grew faster than the market and did so with firmer margins. Management attributes the outperformance to three overlapping forces – portfolio breadth, a methodical product cadence, and pricing discipline compatible with a maturing competitive field.

Portfolio breadth first. Toyota’s range allowed it to straddle buyer segments that behave differently as conditions change. As management told analysts, Yaris carries the middle class urban story; Corolla and Hilux track rural and construction income; Fortuner sits at the premium end. That meant the company felt the flood impact across categories rather than in a single line, but it also meant no single model held the P&L hostage. Within the Yaris Corolla pair, the 70.0/30.0 mix leaned towards the more accessible Yaris, which likely aided volumes as rates stayed elevated for much of the year.

Product cadence was the second leg. The Yaris facelift – which management called a “major update” – drew a strong consumer response, refreshing the mass market anchor at a time when rivals were adding trims, screens and safety suites to win showroom comparisons. Meanwhile, the Corolla Cross broadened Toyota’s SUV reach. The company emphasised that the Corolla Cross, Yaris and Corolla are each localised around 60.0%, an important statistic given the hybrid leaning spec of the Cross. Toyota has been explicit that the market is sedan heavy today but will tilt toward subcompact SUVs over the next five to six years, mirroring global trends and underscored by used car data. In that arc of preference, the Cross is Toyota’s wedge – local, hybrid, and pitched squarely at buyers trading up from a sedan.

Pricing discipline – neither chasing share at any cost nor ceding ground to premiums – was the third piece. Gross margin at 15.0% and operating profit up 126.0%, evidence that Toyota defended profitability even as it lifted throughput.

Competition sharpened notably in pickups and SUVs. Management name checked new entrants such as JAC T9 and GWM Cannon, and acknowledged that Isuzu’s D Max and other Chinese models are intensifying the fight in double cab territory. Rather than retreat, Toyota pointed to market expansion: the overall pie is getting larger, and Toyota intends to keep its slice by improving efficiency and sustaining product freshness.

Even with strong demand in FY25, IMC is planning for a less forgiving FY26 if floods sap disposable income in affected districts. The company’s message is pragmatic: hold margins with operational efficiency, calibrate output to real time bookings, and resist a rush to discount that might undermine resale values – a key part of the Toyota proposition

in Pakistan.

A final note on policy and imports: management has been vocal about the risks of further used vehicle liberalisation. Extending the age limit to five years and allowing commercial imports, they argue, could unleash a wave of used CBUs that would undercut local assembly economics. The company says that if the ground rules change, it will adapt – even if that means pivoting toward imports. The subtext is clear: Toyota prefers to build here, but only under a policy framework that rewards building.

Ask any dealer principal and you will hear the same refrain: four variables dominate car buying behaviour in Pakistan – income visibility, interest rates, fuel economics, and product fashion. FY25 put all four on display, and Toyota’s numbers read like a case study in how they interact.

Income visibility matters most for first time buyers and for upgraders who stretch for a higher trim or body style. Toyota’s breadth across price bands meant it could harvest demand where income was less disrupted –urban salaried households for Yaris, fleet and government procurement for Corolla, and rural and construction linked buyers for Hilux. The company disclosed that institutional volumes are about 10.0% of sales, providing ballast when household budgets wobble. That mix helps explain why Toyota’s volumes rose 60.0% against a broader market up 40.0%. When some parts of the economy slowed, others stepped in.

Interest rates shape affordability directly through auto finance instalments. Much of FY25 was lived at high rates; easing came late. Toyota’s growth in that context suggests a high share of cash buyers in certain segments, and a product/brand proposition strong enough to keep conversion rates healthy even when monthly payments pinch. The company’s caution for FY26 – especially after the floods – is telling: if rates ease but incomes in affected districts sag, bookings can still slip. That is why management emphasises efficiency first, price action second.

Fuel economics are the quiet revolution beneath the bonnet. With petrol prices volatile and urban commutes lengthening, fuel efficient trims and hybrid options command a premium that buyers are increasingly willing to pay. Toyota’s bet here is the Corolla Cross, marketed with its hybrid credentials and a localisation level around 60.0% that helps contain sticker shock. The pitch is classic Toyota: pay more up front, spend less every month, and own a model with strong residuals. As the rupee and fuel prices move, that total cost of ownership story becomes more persuasive.

Product fashion is the fourth driver –and it is shifting. The company expects Paki-

stan to follow global patterns as subcompact SUVs become the default family car over the next five to six years. Used car imports already show the tilt; new car launch calendars will accelerate it. Toyota has both defensive and offensive pieces on the board: Yaris defends the sedan mainstream with a fresher face, Cross introduces hybrid SUV ownership at scale, and Hilux/Fortuner protect the higher end. If the SUV shift gathers pace, Toyota aims to be positioned to catch the wave rather than be caught by it.

Beyond these four, policy signals and supply frictions influence buyer psychology. Each announcement about used car rules triggers a pause as buyers decide whether to wait for more choice; each rumour of CKD part shortages nudges shoppers to book early to dodge delivery delays. FY25’s relative calm on supply – and Toyota’s ability to scale output – helped shorten queues, which, in turn, supported conversion and reduced the “own money” premium phenomenon that often mars the new car experience.

Finally, there is brand risk management – the promise that the vehicle will hold up, parts will be available, resale will be strong, and the company will stand behind the product. In a year of new entrants, those old fashioned virtues still mattered. Toyota’s consistency on warranty, service intervals and parts availability is part of the reason it could earn more while selling more; fewer surprises mean fewer discounts and a healthier used car halo, which loops back into new bookings.

By any measure that counts for investors – profit, dividend, margin or share – Toyota’s Pakistan business had a banner FY25. The company posted record earnings and the richest payout in its history even as rivals expanded line ups and used car imports loomed as a structural threat. It did so by leaning into a product pyramid that covers the mass market and the premium, by refreshing models with enough cadence to keep buyers engaged, and by defending profitability rather than chasing every marginal unit.

The task now is to hold the gains in a tougher operating environment. Floods will test demand. Policy may tilt towards used car liberalisation. Competition will keep sharpening, particularly in pickups and the subcompact SUV space that is set to define the next half decade of Pakistani motoring. Toyota has telegraphed its response: improve operational efficiency, stay close to consumer preference (especially the hybrid curious family buyer), and fight for a policy framework that rewards building over shipping.

FY25 proved that an incumbent can still set records in a noisier market. FY26 will show whether those records were a culmination – or a new floor. n

The bank is a long way from the major hole in its balance sheet that came from the 2008 financial crisis; it now believes it can predictably generate shareholder returns

or years after the 2008 financial crisis, the Bank of Punjab (BOP) has quietly stitched together a sturdier balance sheet and a more predictable earnings engine. The market finally sat up when management crossed a psychological Rubicon: policy backed, recurring cash dividends – paid in year – and an explicit intent to make them a habit.

At its mid year results briefing, BOP announced its first ever interim cash dividend of Rs1.0 per share, a watershed for a bank listed since 1991 but historically conservative about mid year payouts. Management framed the step as the natural outcome of a more resilient capital position and a business mix that throws off steadier income. They emphasised that interim payouts would continue and that quarterly dividends are now a live option –subject to board approval and the cadence of profits. That is a marked cultural shift in how the lender majority-owned by the government of Punjab thinks about capital return.

The numbers supplied the confidence. Second quarter CY25 earnings climbed sharply – management highlighted an EPS near Rs1.5, up around 55% year on year and 175% quarter on quarter, taking 1HCY25 profit to Rs6.5 billion, up 38%. In parallel, deposit funding reached a record Rs1.9 trillion by June, up 23%

since the previous June, with a meaningful improvement in low cost deposits and current accounts now at 24% of the total. Those gains matter because they lower the bank’s cost of funds and make dividends easier to sustain.

Why did earnings step up at just this time? Roughly a quarter of the uplift in net interest income (NII) came from the removal of the minimum deposit rate floor for non individuals – a change in central bank policy that allowed banks to re price corporate and public sector deposits more flexibly from 1 January 2025. The remaining three quarters of the NII gain came from the hard yards of banking: cheaper mix (more current accounts), systematic term deposit repricing (with 64% of deposits repriced by June and 87% by August), and better yields on the loan book. Management’s maths suggests that as the last 13% of term deposits roll over, spreads can still inch higher. The backdrop for all of this was a rate cycle already edging down, which the bank believes could deliver a further 1.0–1.5 percentage points of cuts in the months ahead.

When banks promise recurring cash, valuation tends to follow. Sell side estimates place BOP at a forward price to book near 0.6 times for CY25–CY26, a discount to peers that drew attention once the bank paired earnings momentum with a payout blueprint. The stock has been hovering near its 52 week high in recent sessions – an implicit vote that a bank once known mainly for steadiness is now being

priced for repeatable shareholder returns.