08 17

08 17

08 Daimler Truck is coming to Pakistan. Kind of.

10 Farewell, Careem Pakistan

15 Supernet’s post-connectivity pivot: doubling revenue at the cost of thinner margins

17 What the new field of bidders tells us about PIA’s privatization

20 Ittehad Chemicals: a case study in the shift away from captive power generation

22 Beco Steel: From the ashes of one rises another

27 In Bonnie Doon acquisition, Interloop seeks move up the value chain

29 Lahore High Court’s royalty decision gives Punjab’s cement manufacturers pricing disadvantage

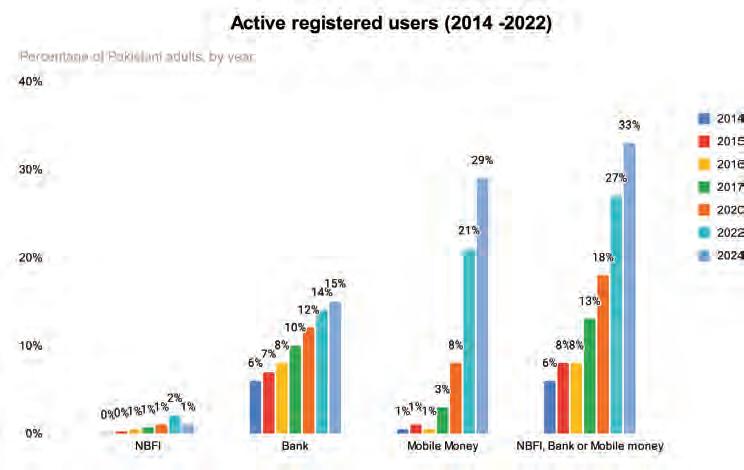

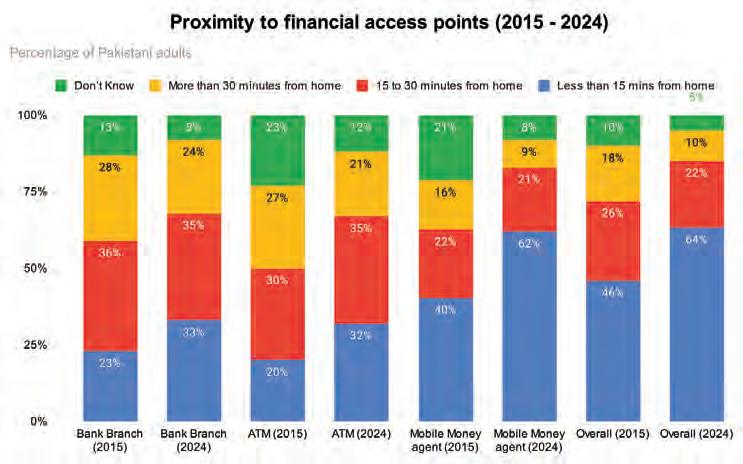

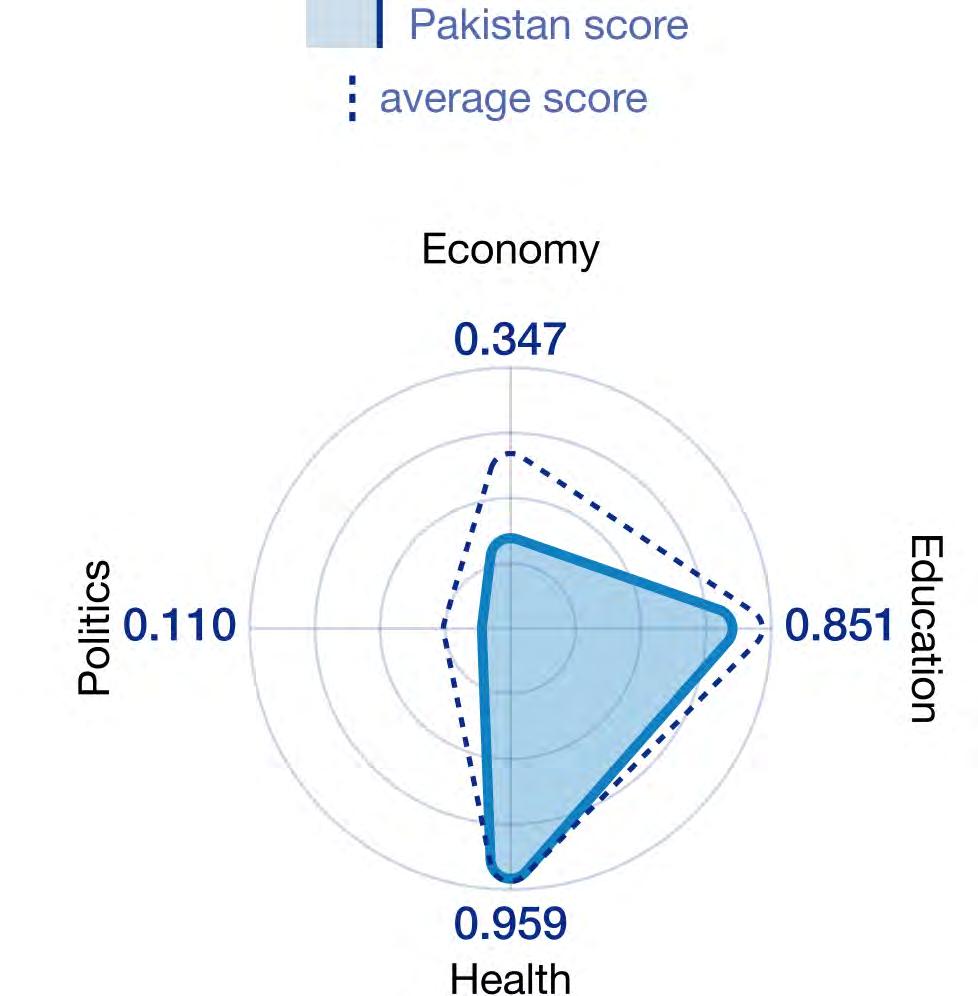

31 Pakistan has made leaps and bounds in financial inclusion, but our women continue to be left behind

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Muddasir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi)

Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

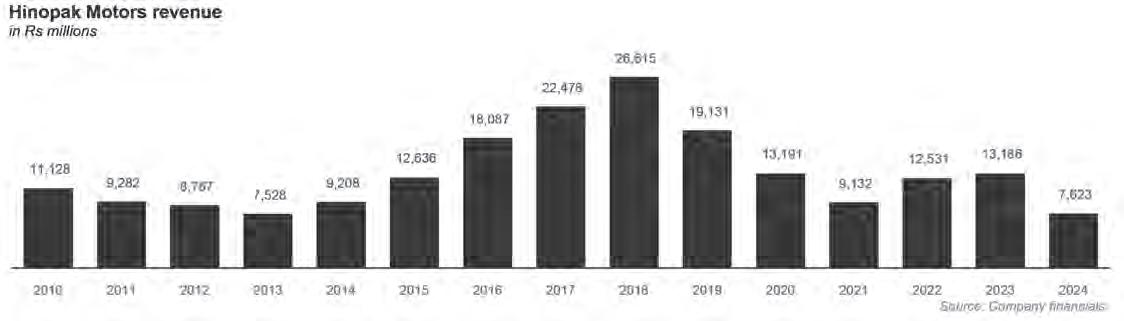

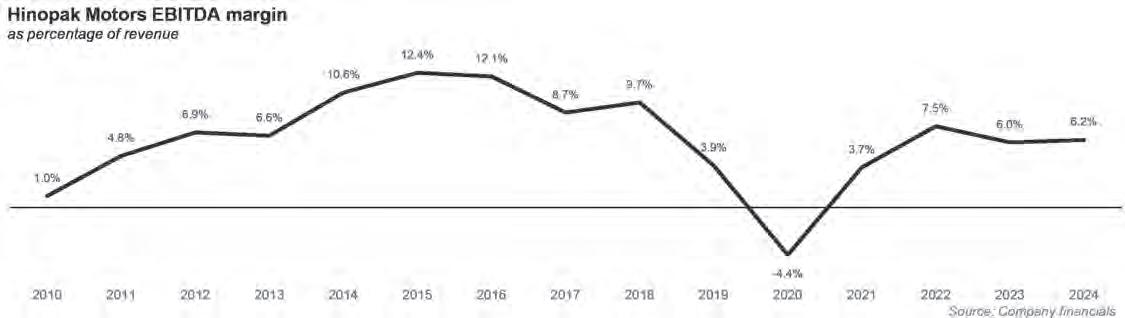

As a result of a global merger, Daimler Truck – the largest commercial vehicle manufacturer in the world – will become a joint venture partner with Toyota in Hinopak Motors

In what could be a significant development for Pakistan’s automotive sector, Hinopak Motors Ltd is set to gain a German parent company, which would be the first time any Pakistani publicly listed automotive company has had a German parent company ever.

This follows the confirmed merger of Japan’s Hino Motors Ltd and Mitsubishi Fuso Truck and Bus Corporation (MFTBC) into a new joint venture backed equally by Toyota Motor Corporation and Germany’s Daimler Truck. The move will create a unified Asian commercial vehicle powerhouse, and for Hinopak, it will mark a transformative new chapter.

The newly formed joint venture, which will house both Hino and Fuso brands under a single corporate entity, will serve as the parent company of Hinopak Motors. It will represent the first time a major German automaker — in this case, Daimler Truck — will have an indirect controlling stake in a Pakistani automotive manufacturing company.

This strategic consolidation aims to pool resources in the face of evolving emissions

standards, electrification, and global supply chain challenges. For Pakistan, the ripple effects are expected to be significant: access to broader technology platforms, integration into a more diverse supply chain, and a higher profile in international automotive circles.

Below, we explore the background and implications of this groundbreaking merger, and the legacy of the companies that form its foundation.

Hinopak Motors Ltd is Pakistan’s premier manufacturer and assembler of commercial vehicles, known for its Hino-branded trucks and buses. The company was founded in 1986 as a joint venture between Hino Motors Ltd (Japan), Toyota Tsusho Corporation (Japan), Al-Futtaim Group (UAE), and Pakistan Automobile Corporation (PACO).

Originally created to reduce Pakistan’s dependence on imported commercial vehicles, Hinopak quickly rose to dominance in the heavy- and medium-duty vehicle segments. Headquartered in Karachi, it maintains a large-scale assembly facility that has produced tens of thousands of buses and trucks for the domestic market.

Following the privatisation of PACO’s

stake in the late 1990s, Al-Futtaim and Hino Motors became the principal shareholders. The company went on to expand its product line, develop an extensive after-sales network, and become a critical part of Pakistan’s transportation infrastructure, serving logistics companies, public bus systems, and municipal fleets.

Hinopak is listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. As of 2025, it remains the country’s leading commercial vehicle brand.

Hino Motors Ltd, a Toyota Group company, is Japan’s leading manufacturer of trucks and buses. Founded in 1942 as Hino Heavy Industry Co., Ltd., the company evolved from its roots in military diesel engine production to become a major force in civilian commercial vehicles post-World War II.

The company became a dedicated commercial vehicle manufacturer in the 1950s, offering a range of light, medium, and heavy-duty trucks as well as buses. Hino Motors was officially brought under Toyota’s control in the 1990s, becoming an integral part of Toyota’s commercial vehicle strategy.

With operations in over 90 countries, Hino is known for its engineering robustness, reliable diesel engines, and expanding portfolio

of environmentally friendly vehicles. In recent years, however, it has faced challenges, including an emissions data falsification scandal in 2022, prompting major restructuring and governance reforms.

Despite setbacks, Hino remains a key player in Asia and emerging markets, especially through subsidiaries like Hinopak. The merger with Fuso is seen as a bid to revitalise its global competitiveness.

Mitsubishi Fuso Truck and Bus Corporation (MFTBC) is another pillar of Japan’s commercial vehicle industry. With roots dating back to the 1930s, Fuso became a distinct entity in 2003 following a spin-off from Mitsubishi Motors and a major equity investment by Daimler AG (now Daimler Truck).

Based in Kawasaki, Japan, MFTBC manufactures a wide range of commercial vehicles, including the popular Canter light-duty trucks and the Rosa mini-bus. It has been a pioneer in electric commercial vehicles, unveiling its first fully electric light-duty truck, the eCanter, in the 2010s. Daimler’s involvement brought a global orientation to Fuso’s operations, integrating it into the broader Daimler Truck Asia division, which includes substantial operations in India and Southeast Asia.

Fuso is well-known for its technological innovation, global footprint, and role in pushing electrification in commercial transport.

Daimler Truck AG, headquartered in Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany, is one

of the world’s largest commercial vehicle manufacturers. Created as a separate entity following the 2021 spin-off of Daimler AG’s truck and bus division, it owns globally recognised brands such as Mercedes-Benz Trucks, Freightliner, Western Star, and Fuso.

Daimler Truck operates across Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. It has a workforce of over 100,000 and manufactures vehicles ranging from long-haul trucks to inner-city buses and zero-emission electric commercial vehicles.

The company has made substantial investments in autonomous driving, connectivity, and hydrogen fuel-cell technologies. Daimler Truck’s strategic focus includes reducing carbon emissions, improving safety, and entering new growth markets.

Its joint venture with Toyota to merge Fuso and Hino represents a landmark moment in Daimler Truck’s Asia strategy and signals its intent to play a broader role in the global integration of commercial vehicle markets.

Interestingly, this is not the first time a major German automaker has flirted with establishing a manufacturing presence in Pakistan. In 2017, widespread media reports suggested that Volkswagen Group’s commercial vehicle arm, MAN Truck & Bus, was exploring the possibility of setting up assembly operations in Pakistan.

The discussions reportedly involved collaborations with local partners and even

included exploratory visits by MAN executives to industrial zones near Karachi and Lahore. The move was seen as a potentially transformative step for Pakistan’s automotive sector, given MAN’s reputation for high-quality heavy-duty vehicles.

However, despite the initial enthusiasm, the talks failed to materialise into a formal venture. Various factors were speculated to be behind the collapse, including Pakistan’s inconsistent auto policy environment, macroeconomic instability, and MAN’s internal strategic shifts.

That episode remains a notable “what if” in Pakistan’s industrial history. Today, the incoming involvement of Daimler Truck in Hinopak represents a realisation of the ambition that once swirled around MAN’s aborted entry.

With the merger of Hino and Fuso under the joint stewardship of Toyota and Daimler Truck, Hinopak is poised for a historic transformation. The German industrial presence that eluded the Pakistani market in the past now arrives through a more integrated and strategic pathway. For Pakistan’s commercial vehicle industry, this could mark the dawn of a new era — one defined by enhanced technology, stronger international collaboration, and a renewed focus on sustainability and innovation.

As stakeholders digest the implications of this merger, one thing is clear: Hinopak’s future is now tied to a broader, more globalised commercial vehicle ecosystem than ever before. n

The ride-hailing giant was an early innovator in Pakistan, and made the country one of its core markets. Now, Pakistan is just a back office for the company. How did the company cede so much market share to its newer competitors?

By Nisma Riaz

There is no sugarcoating how bad this is: Careem is leaving Pakistan – and so far, only Pakistan – and this is a reflection of just how tough it is to grow a tech business serving the Pakistani market, specifically its middle class.

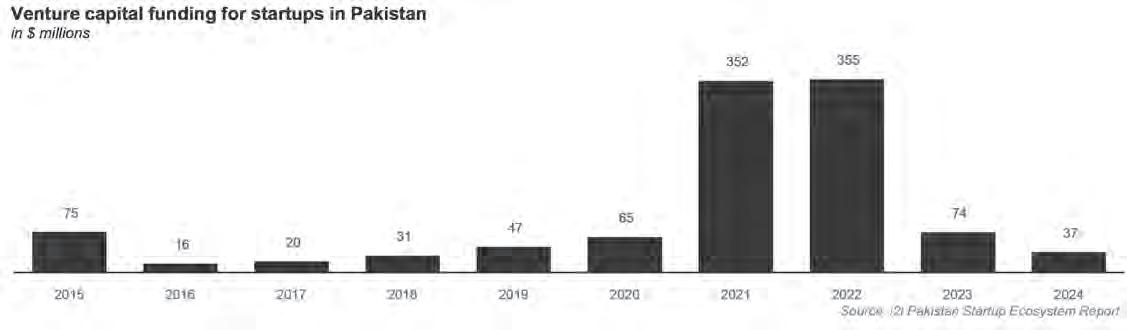

Careem is technically not a Pakistani startup, but it has a Pakistani founder and its Pakistan operations were a key part of its story. Its acquisition by Uber for $3.1 billion in January 2020 was marked as a turning point for the Pakistani tech sector: it was seen as a successful exit of a startup that also served Pakistan and helped put Pakistan on the map of global venture capitalists. The next two years saw the high-water mark for venture investing in Pakistan. Pakistani startups raised $352 million in venture funding in 2021, and $355 million in 2022.

In venture investing, however, being early is the same as being wrong, and Pakistan’s tech startup market is clearly way too early. Careem, like most tech businesses in the country, are discovering that despite the tales of a quarter billion people, Pakistan’s actual servable middle class is a tiny proportion of that massive population, and one can reach saturation very quickly.

Once you hit that point, further growth must await Pakistan’s economic take-off, which is still about a decade away. And if you are owned, as Careem is, by a foreign parent company that has many other targets for growth and claims on its growth capital, that means no room for spending resources on Pakistan.

So now, despite what appears to be a valiant effort on the part of Careem’s management in both Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates, including founder Mudassir Sheikha himself, Careem is exiting the Pakistan market for its ride-hailing business.

It will retain a presence in the country as a back office for the development of its super app for the Middle East market through Careem Technology, a subsidiary into which e& - the UAE-based telecom company formerly known as Etisalat – invested $400 million for a majority stake in April 2023.

A source who wishes to stay anonymous told Profit, “Careem’s business volume was low. I think they were running in Pakistan for sentimental reasons only for a few years, and eventually shut down.”

Yet despite this clear setback for Pakistan’s tech ecosystem – and broader economy – it is worth diving into what Careem was able to achieve in building what it did. We will then look at how it stacked up compared to its eventual copycat competitors, what caused its eventual demise, and what may come next.

In 2015, Pakistan’s public transport system, particularly in Karachi, was widely seen as inefficient, unsafe, and outdated. The city’s buses, often referred to as “mini buses,” were largely operated by a powerful and unregulated transport mafia. Despite having designated routes, these buses lacked formal stations or schedules. Commuters had no choice but to flag down moving vehicles and hop on as they slowed, often at their own risk. With the disappearance of yellow taxis, the transport landscape was dominated by buses and rickshaws, modes of travel commonly associated with lower-income groups. As a result, much of the middle class chose to distance itself from public transport altogether.

Then came Careem and revolutionised urban transport for the middle and upper middle classes, paving the way for a culture of ride hailing.

In conversation with Profit, an alumnus of Careem said, “In the past, especially five to ten years ago, women used to rely on their fathers or brothers to take them places and that was considered the ‘correct’ or ‘safe’ way. But Careem changed that for millions across Pakistan. It gave women the confidence and independence to go out on their own. It wasn’t just about transport, it was about giving access: Access to opportunities, independence, and to being part of society. People can dismiss it, but that social shift is massive. Our mothers’ and grandmothers’ generations couldn’t have imagined such freedom.”

Careem had invested heavily in safety infrastructure, including captain vetting, real-time support, and flexible in-app communication tools; features that particularly resonated with its large female user base.

Following its successful breakthrough in the country, Careem made way for giants like Uber, Yango and inDrive to take footing in Pakistan.

From being the trailblazer of ride hailing in Pakistan, soaring through a pandemic, getting acquired by Uber and tweaking its offerings and prices to compete with new entrants with big pockets, to finally giving up and exiting the market, it has been a hell of a ride for Careem.

By 2021, Careem had firmly embedded itself into Pakistan’s urban transportation narrative but not without paying a steep price. Changing consumer behavior in a low-trust, cash-heavy market like Pakistan is exceptionally hard and expensive.

While Careem enjoyed the first entrant advantage, it also dealt with its own unique set of challenges that come with being the first one to do something in a new market.

Careem’s rise was driven by calculated investments in both customer and driver incentives. This strategy was necessary to overcome the “chicken and egg” dilemma inherent in building a two-sided marketplace: riders would not use the app without enough drivers, and drivers would not join without a base of paying customers.

To solve this, Careem heavily subsidised drivers, known internally as ‘captains’, offering income guarantees, bonuses, and other perks. Between 2016 and 2019, the company spent an additional Rs12.5 billion on driver incentives, beyond the Rs43.7 billion they earned from ride shares. At its peak, 29% of a captain’s income came from these bonuses, although that figure gradually dropped to 19% as rider demand grew.

Careem’s user base saw exponential growth in its early years, rising from 118,000 in 2016 to 3.6 million by 2020. But this growth was not steady. The bulk of users joined in the first three years, primarily from affluent, tech-savvy circles in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. These early adopters required significant promotional nudges to try the service, but often became loyal customers. Growth slowed as Careem tried to expand beyond this core demographic, where fewer people could afford its service, pushing up the cost of acquiring each new user.

From a financial perspective, Careem’s customer acquisition cost (CAC) fluctuated wildly year to year, depending both on marketing spend and how many net new users joined the platform. While incentives to drivers made up nearly two-thirds of CAC, a smaller portion was directed at riders through fare discounts and digital marketing. Profit’s previous analysis of financial statements from 2016–2019 revealed an ongoing effort to keep CAC below average revenue per user (ARPU), a delicate balance critical to long-term viability.

By 2019, data showed that Careem had hit a saturation point in Pakistan’s middle class market, struggling to hit the 4 million user mark. Yes, even hitting 2% of Pakistan’s population as its active user base was massively expensive proposition. The 2020 pandemic lockdowns did not help matters.

With CAC rising and user growth slowing, the company faced a strategic crossroads; continue expanding to newer, and less profitable, user segments, or extract more value from existing ones. Careem chose the latter. Instead of chasing scale, it aimed to deepen engagement through a “Super App” strategy, offering food delivery, logistics, and financial services like Careem Pay within a single platform.

By January 2020, Careem had been acquired by Uber, and was operating in Pakistan as a subsidiary of Uber.

The pandemic of 2020 accelerated Careem’s pivot. With its ride hailing revenues declining, Careem leaned into deliveries and digital payments. Management was candid about their ambitions to increase the ARPU not by adding more users, but by increasing the ‘R’, revenue, from each user. In Pakistan’s underserved financial landscape, Careem positioned itself as a credible player in digitising payments and offering financial tools to a user base already accustomed to transacting on its platform.

Yet, the Super App model is a highstakes gamble. While the potential to become a one-stop platform is alluring, it carries the risk of feature bloat, poor user experience, and dilution of brand identity. Careem’s plan to open its app to third-party startups added complexity, making execution critical. Whether it could maintain coherence across verticals, or end up overwhelming users, depended on its ability to balance innovation with simplicity.

Careem’s story is one of audacity and strategic reinvention. It succeeded in changing consumer behaviour but then faced a new challenge; staying indispensable in a market it helped create.

When Careem first launched operations in Pakistan, it enjoyed the rare privilege of shaping consumer behaviour in a largely unregulated space. With no major competitors in sight, the company had the freedom to experiment, iterate, and set its own rules. But that era of monopoly did not last long.

As Pakistan’s ride-hailing market matured, so did the intensity of its competition. The entry of Yango, a Russian Yandex Groupbacked platform, marked a turning point. Already contending with inDrive, another Russian-origin player offering fare-bidding and deep discounts, Careem now faced a twopronged threat. The pressure mounted further when local player Bykea, with its strong delivery footprint, expanded into car-hailing and adopted similar user-controlled pricing mechanisms.

In response to this rapidly shifting landscape, Careem launched Flexi Ride in November 2023, a strategic move that allowed customers to bid on fares and exercise more control over their travel costs. This was a clear departure from Careem’s earlier pricing model, where fares were auto-generated and left little room for negotiation. While the company retained its traditional structure for those who preferred set rates, Flexi Ride was designed to appeal to a more price-sensitive and value-driven segment of the population. The product launch was not only a reaction to external competition but also a reflection of internal reassessment as macroeconomic conditions in Pakistan worsened and consumers began tightening their wallets.

Soon after Flexi Ride’s introduction, Careem revised its fare structure more broadly. The adjustments aimed to reflect the new economic realities, ensure driver sustainability, and prevent further erosion of market share.

In a 2024 interview with Profit, Muhammad Imran Saleem, Careem Pakistan’s General

Manager highlighted that pricing had become the most critical battlefield. A slight fare fluctuation could trigger user migration to a competitor app, especially as Yango aggressively undercut the market on price.

To combat this perception, Careem emphasised that its pricing model was rooted in dynamic adjustment, using real-time demand and supply data to ensure fairness for both riders and drivers. Saleem asserted that Careem was not as expensive as commonly believed. Instead, it aimed to strike a balance, ensuring customers paid reasonable fares while captains remained financially viable.

Unlike Yango, which does not show drivers the fare upfront, Careem prioritised transparency. Captains were educated on fare structures, including base rates, per-kilometer earnings, and time-based compensation. They also received detailed breakdowns before accepting rides, allowing them to make informed decisions and anticipate actual earnings, especially in cases of heavy traffic or route changes.

Beyond pricing, Saleem pointed to two core differentiators: localisation and security. Careem had long tailored its services and messaging to Pakistani cultural nuances, setting it apart from global competitors who often relied on poorly translated campaigns. Furthermore, Careem had invested heavily in safety infrastructure, including captain vetting, real-time support, and flexible in-app communication tools; features that particularly resonated with its large female user base.

Captains and commuters both agreed that Careem, despite the larger perception of being expensive, was the safest car service, and could be relied on in case of emergency, with efficient and helpful customer service and aid.

In a crowded, price-sensitive market that it had once helped create, Careem’s comeback strategy hinged on flexibility, fairness, and trust. With Flexi Ride, revised pricing, and a renewed focus on local insight and safety, the company fought to reclaim its edge, not by racing to the bottom, but by reinforcing the

value of a ride well delivered.

On the surface, Careem’s exit from Pakistan’s ride-hailing industry appears to be a casualty of worsening macroeconomic conditions. In its official statement, the company cited external pressures as the reason behind its decision to suspend ride-hailing services as of July 18, 2024, “Due to tough market conditions for the Pakistan ride-hailing industry, the difficult decision has been made to deactivate the Careem Rides services in Pakistan as of July 18. Careem Technologies remains deeply committed to Pakistan and will continue expanding as a talent hub in Pakistan, powering the Everything App across the region.”

The narrative presented is one of economic inevitability, a victim of inflation, dollar shortages, and a broader funding winter.

One theory could be that in a two-sided marketplace, if there is a conflict between what both sides want out of the marketplace, it puts the owner of the marketplace in an impossible position of picking which side to back. In the ride-hailing market, while riders largely embraced digital payments and were comfortable with dynamic pricing models, drivers preferred control; negotiated fares, cash transactions, and a more hands-on approach to pricing.

InDrive understood this and built its platform around driver preferences, allowing them to set their own prices and negotiate directly with customers. Careem, on the other hand, stayed committed to a rider-centric model with automated pricing and a push toward digital payments. Ultimately, that bet cost them. In a market where driver supply dictates platform viability, Careem backed the wrong side.

While there has been plenty of discussion around pricing models, especially the bid-offer system that allows customers and drivers to negotiate fares, its actual impact on market dominance is questionable.

“Bykea also has a bid-offer model, both in the bike and the car category,” Muneeb Maayr, founder of Bykea, acknowledged, “but you can’t really say it’s a superior model because Yango has clearly come in without it, just deploying enough capital to take the market share.”

In other words, money, not models, won the game.

A former Careem employee, however, contested the idea that digital payments were a primary operational challenge. “Electronic payments were not a problem, in fact there actually was a solution already. Around two years ago, we launched something in collaboration with JS Bank Zindagi Wallet that solved the payment issue,” they explained. Instead, they attributed Careem’s downfall to broader investment fatigue, compounded by poor macroeconomic conditions that made returns elusive.

“Digital payments was not the problem. It was just that the investment going into the market was not being returned due to macroeconomic challenges,” they added.

But perhaps the most telling factor was not external, but structural. According to the same ex-employee, the true unraveling began two years ago, when Careem’s parent company Uber finalised a split between its own operations and those of Careem Technologies. “When the deal between e& and Careem happened about two years ago, the outcome was that everything other than ride-hailing was transferred to e&, while the ride-hailing business went solely to Uber.”

This meant that Uber, while owning Careem Rides, was essentially leasing Careem Technologies’ infrastructure, finance systems, tools, even basic services like laptops and Zoom accounts. “Uber was technically paying Careem, which it owns, to use Careem Technologies’ infrastructure, all of this was adding up and becoming quite costly for Uber.”

In an era where cost efficiency is paramount, especially for tech companies with global footprints, Uber began consolidating operations. According to the insider, “Uber is now working across different markets to con-

solidate the Careem Rides app into the Uber app. The idea is to streamline operations and reduce costs network-wide.”

Pakistan wasn’t the only market impacted. “About a month and a half ago, they laid off people from markets like Egypt, Jordan, and others,” a former employee noted. “They had also informed the Pakistan team that the future isn’t looking very bright. They said that some people would be let go by June or July, and a few critical people needed for integration would be kept on until November.”

Layoffs followed swiftly. “From what I’m seeing on LinkedIn posts,” the ex-employee added, “it’s pretty clear that layoffs are happening.”

So while Careem’s public statement emphasised challenging economic conditions, the full story includes cost-cutting measures by Uber, a fractured internal structure post-acquisition, and a quiet consolidation of global operations, all of which culminated in a decision that feels as corporate as it does cold. In the end, the death of Careem Rides in Pakistan wasn’t a collapse; it was a calculated phase-out, made in boardrooms far from Karachi or Lahore.

According Maayr, despite Pakistan’s turbulent macroeconomic climate, the ride-hailing market has not just survived, it has expanded. He said that a major reason for this unexpected growth is the rising cost of car ownership, which has pushed more people toward ride-hailing and pooling services. This shift in consumer behavior has created a ripe opportunity that aggressive players like Yango and InDrive were quick to seize.

“Yango has invested tens of millions of dollars into the country,” said Maayr, adding, “This influx of capital, targeted at subsidising rides and rewarding drivers, gave Yango the muscle it needed to quickly capture a significant portion of the market. inDrive took a different but equally bold route, offering zero percent commission for the first two years, then pouring money into high-visibility advertising campaigns.”

Caught between these two aggressive plays, Careem lost ground. Yango and inDrive collectively took over most of the car-hailing market, while Bykea, with its strong focus on two-wheelers, captured the majority of the motorbike segment, particularly in Karachi. “From a timing perspective,” Maayr added, “Uber had acquired Careem’s ride-hailing business, but they perhaps were not willing to compete, in dollar terms, with the likes of Yango.”

There’s also the possibility, he noted, that Uber simply deprioritised Pakistan in its global strategy. After all, in markets where profit margins are tight and capital outflows exceed returns, companies often pull back, and Pakistan may have been no exception.

A source who wishes to stay anonymous told Profit, “Careem’s business volume was low. I think they were running in Pakistan for sentimental reasons only for a few years, and eventually shut down.”

The former part of this statement was resonated by almost all drivers Profit interviewed, who admitted that they hardly found rides on Careem and migrated to other apps by proxy.

Meanwhile, Bykea remains bullish. “In Karachi, this market nearly doubled for us in the last quarter,” Maayr shared, pointing out that their car business has now surpassed their delivery segment in volume. With a strong foothold in motorbikes and taxis, and a growing share in car-hailing, Bykea is shaping up to be one of the last serious local contenders standing.

As Careem prepares to pack up its ride-hailing operations in Pakistan, questions naturally arise about who will step in to fill its shoes. While the company exits with a legacy of trust, safety, and first-mover advantage, riders and drivers alike are already recalibrating their loyalties based on price, availability, bonuses, and service quality.

The verdict?

Well, there is no single winner, at least not yet. But user sentiment paints a complex picture of a fragmented market, in which each platform holds a different appeal depending on who you ask.

For drivers, earnings and efficiency remain paramount. Ali Raza, who has driven for all major apps, put it bluntly, “In Karachi, Careem only works for those travelling within DHA or for corporate clients. For me right now it is InDrive and Yango that bring the most work.” In his experience, Bykea offers better tax deductions but too few rides to make it worth the time.

Haq Nawaz, who drives with Yango, highlighted the company’s generous bonus structure, “Today, when I finish 18 rides, I will get Rs 1000.” Still, he was quick to add that Careem was unmatched when it came to safety and documentation, noting that, “Yango and InDrive just ask for basic details, while Careem invests in driver security and well-being.”

Other drivers appreciated Yango’s automation. “I prefer Yango because it assigns rides automatically, while on InDrive you have to bid and that wastes a lot of time,” said Jahangir Khan. However, he acknowledged that Careem paid more for business-class cars. One Careem loyalist described how the company once stood apart with its bonus structure,“Careem was offering a bonus of Rs2,700 on 16 rides. That made a big difference compared to the others.”

Even when rides were sparse, drivers still trusted the platform for its corporate clientele and strong incentives.

Still, for part-time or budget-conscious drivers, the new entrants were difficult to ignore. “I use all the ride-hailing platforms,” said Attique Akram, “but in recent times, Careem has offered the best bonuses for sedan cars.” Yet others, like Hamza Jawed, cited Yango’s affordability and broader appeal, “Most people prefer to use Yango these days rather than Careem because it is budget-friendly and has employed better marketing strategies.”

From the riders’ side, preferences diverged even more sharply. For some, affordability was king. “I prefer InDrive because the prices are low,” said Sarah, “but Careem’s business account service was really good. The call center actually helps.” Others like Maryam valued the ability to set their own price in InDrive, but acknowledged that Careem once led the pack in terms of security and support. “Careem’s prices had gotten very expensive, so I made the switch to InDrive.”

But not everyone was convinced by the low-cost alternatives. “Yango is the worst service that exists,” said Zaryab, citing poor car conditions and unprofessional drivers. In contrast, “Careem is the absolute best, no issues with drivers and it’s very efficient, but almost Rs 100 more expensive each time.” Safia echoed this sentiment after a bad experience, “After almost getting kidnapped while using Yango, I’ve stopped using it even though it’s cheap.”

For users like Sufyan Ahmed, platform preference depends on context. “I usually choose Yango when I’m going to familiar areas, since I don’t fully trust their drivers but Careem is my go-to when I need to travel far because I can rely on its customer service, better-vetted drivers, and improved safety.”

This reflects a broader theme: Careem’s strength lay not in being the cheapest, but in being the most dependable.

And yet, as Careem prepares to exit, no single competitor has managed to replicate its full value proposition. InDrive is winning on price flexibility. Yango is flooding the market with bonuses and aggressive marketing. Bykea has yet to fully penetrate the car-hailing segment. While each platform fills a gap, none fully replaces the ecosystem Careem built, one of trust, regulation, and infrastructure.

Careem’s departure is not just a commercial retreat, it marks the end of an era. As its farewell note rightly puts it, “Careem did not just build a service, it delivered significant public goods: digital infrastructure, trust, regulation, capability, confidence.” In a market still defining what ride-hailing should be, the next leader will need to offer more than just low prices, they’ll need to build confidence, inspire loyalty, and above all, earn trust. n

Supernet Ltd, the first technology company to list on the Pakistan Stock Exchange’s Growth Enterprise Market (GEM) board, has released headline numbers that show just how quickly a small-cap ICT firm can swell in size when it ventures beyond its comfort zone – and – how costly the learning curve can be. Consolidated revenue in the year to June 2024 leapt 117% to roughly Rs8.5 billion, propelled by a flurry of low-margin infrastructure contracts that management says are “foundational” for becoming a onestop digital-solutions provider. Yet gross profit fell sharply: the margin slid to 16%, down from 29% the previous year and well below the company’s three-year average of 30%.

The market response has been nuanced rather than euphoric. After touching a 52week high of Rs46.90 earlier this year, the share closed last Friday at Rs34.77 on modest volume, trimming the 2025 year-to-date gain to 92% (dps.psx.com.pk). Analysts put the stock’s trailing P/E at 27 – not eye-watering for a growth name, but sufficiently rich to demand evidence that management can rebuild profitability while still chasing scale.

Supernet’s audited accounts lodged with the PSX show unconsolidated sales of Rs7.37 billion for fiscal year 2024, up from Rs3.43 billion a year earlier – already a doubling, and one achieved before the group makes the

customary post-consolidation adjustments that lift the top line toward the disclosed Rs8.5 billion figure. Company officials say a clutch of turnkey data-centre builds, fibre roll-outs for provincial government clients and power-conditioning work for telcos accounted for three-quarters of incremental revenue.

But those same projects clipped margins by forcing Supernet to book hardware passthrough and subcontractor costs it does not face in its higher-margin satellite and microwave-connectivity franchise. The prize is the annuity stream once those facilities need upgrades, managed services and cybersecurity layers.

Founded in 1995 as a data-network operator, Supernet spent its first quarter-century selling bandwidth to corporate Pakistan. The model

delivered steady, if unspectacular, growth –enough to persuade parent company Telecard to spin off the subsidiary through a Rs475 million GEM listing in 2022, a deal that was oversubscribed 1.4 times (thefrontierpost. com). Since then, management has trumpeted a strategic pivot that echoes regional peers such as India’s Bharti Airtel or Indonesia’s Indosat Ooredoo: connectivity first, then an expanded “digital stack” of cybersecurity, cloud hosting and managed infrastructure.

The fiscal year 2024 figures show that pivot taking hold. Connectivity revenue still grew, but the real lift came from so-called “beyond connectivity” lines – servers, power, data-centre fit-outs and network-security appliances. Supernet’s recently created subsidiaries sketch the architecture:

Management says the four units together fetched Rs1.75 billion worth of fresh infrastructure orders last year, while the legacy connectivity business won Rs4.7 billion of

SuperSecure 2019 Cyber-security services Aims to export SOC outsourcing

Supernet Infrastructure (SuperInfra) 2023 IT & power-conditioning build-outs Main driver of fiscal year 2024 sales spike

Supernet E-Solutions 2020 Packaged software & integration Bundles Microsoft and Oracle workloads

Phoenix Global 2022 UAE-based offshore arm Gateway for GCC contracts

multi-year contracts and SuperSecure bagged Rs3.5 billion, taking the total order book to nearly Rs10 billion – equivalent to more than a year’s group revenue.

Supernet’s critics point out that a 13-percentage-point erosion in gross margin cannot be waved away as a one-off. The average gross margin for listed Pakistani IT service providers hovers near 25%, giving Supernet almost the thinnest spread in the peer group. Management counters that infrastructure deals carry up-front hardware flow-through that distorts the accounting line-item but not necessarily the lifetime economics.

Scaling at home is only half the battle. Supernet’s management has long argued that Pakistani labour costs give it a structural edge in selling security-operations-centre (SOC) outsourcing to overseas clients. May’s partnership with Azercosmos, Azerbaijan’s national satellite operator, is being held up as proof of concept. The non-exclusive memorandum of understanding covers satellite bandwidth, connectivity backbone and, crucially, managed cyber-defence for Azercosmos customers in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

The company is treating Baku as its bridgehead for Eurasia. The company is also exploring a tier-3 SOC in the United Arab Emirates through Phoenix Global, its Dubai subsidiary, to capture “Friday-to-Sunday time-zone synergies” – Pakistan’s analysts monitoring GCC assets during weekend downtime.

If connectivity was yesterday’s play, and cybersecurity today’s, the next leg is data-centre and server infrastructure tuned for artificial-intelligence workloads. Global hyperscalers have yet to commit capacity inside Pakistan’s borders; when they do, they will require energy-efficient racks, precision cooling and sovereign-cloud compliance –services Supernet says SuperInfra is positioned to supply.

The thesis rests on macro trends. Pakistan’s IT exports grew 28% to USD 1.86 billion in the year to February 2025, according to the Ministry of IT; officials project the figure could reach $4 billion this fiscal year as part of a national goal of USD 10–11 billion by 2030. With Islamabad scouting foreign data-centre investors to absorb surplus power from new RLNG plants, Supernet believes local integrators will have home-field advantage.

At last count the group’s signed backlog stood at Rs9.96 billion, split across four customer clusters:

1. Telco and enterprise connectivity (Rs4.7 bn). Satellite uplinks for remote mines, microwave backhaul for city-wide CCTV grids, and redundant fibre loops for banks.

2. Cybersecurity services (Rs3.5 bn). SOCas-a-service for a Karachi-based bank, endpoint detection for a defence contractor, and penetration-testing retainer agreements.

3. Infrastructure turnkey (Rs1.75 bn). Two provincial data-centre builds, a 10 MW power-conditioning contract for a hyperscaler’s Karachi edge node, and several smaller campus-LAN roll-outs.

4. Software & integration (~Rs0.01 bn).

Pre-packaged ERP deployments under E-Solutions, a line item management expects to ramp once SuperSecure cross-sells enterprise suites.

Management projects that 60% of the backlog will convert to revenue in the next 24 months, with the remainder hitting the topline by fiscal year 2029.

Supernet’s rapid scale-up has resurrected an ambition first voiced at its 2022 IPO: migrate from the GEM board to the PSX main board once paid-up capital exceeds regulatory thresholds. On 27 May 2025 the board approved a scheme of arrangement to merge the parent company into its wholly owned subsidiary, Supernet Technologies Ltd, in advance of a main-board application (profit. pakistantoday.com.pk). The transaction still requires shareholder, creditor and High Court of Sindh approval, but management targets completion by 2026.

Under the draft plan, existing GEM shareholders would swap their holdings for shares in the enlarged entity at a ratio yet to be finalised. Market watchers expect the move to broaden the investor base, improve liquidity and allow Supernet to tap cheaper equity for capex heavy infrastructure projects. Yet the migration also raises governance expectations; main-board issuers must publish quarterly earnings within 30 days, appoint a majority of independent directors and maintain higher free-float.

At the last close, Supernet sported a market capitalisation of Rs4.7 billion, or roughly 0.55x forward sales. That discount to regional digital-infrastructure integrators – Telkom In-

donesia’s Mitratel, for instance, trades near 3x – reflects Pakistan-specific risk, the illiquidity of GEM scripts and fears that margin compression could prove sticky. Nonetheless, the oneyear share price gain of 223% puts Supernet among the PSX’s top performers.

Topline Securities analysts retain an “outperform” stance, arguing that “fiscal year 2024’s pain is the entrance fee to a higher-quality earnings stream”. They model margins rebounding to 22% by fiscal year 2027 as managed-services revenue layers over infrastructure installations and international cybersecurity fees kick in. Risks include project-execution slippage, a weaker rupee inflating imported hardware costs, and slower-than-expected finalisation of the merger.

Supernet credits its agility to a lean management bench under CEO Jamal Nasir Khan, a former Telecard executive who led the GEM listing, and COO Tahir Malik, poached from Jazz to spearhead non-connectivity ventures. The company employs roughly 740 staff across Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore and Dubai; 260 of those work in cybersecurity and managed services, a figure management wants to double by 2027 – an ambition predicated on Pakistan’s abundant, low-cost stem graduates.

Anecdotally, the firm’s flat hierarchy and stock-option plan have helped retain engineers in a market where overseas remote gigs often lure talent away. Management says the average employee age is 28; the biggest single cost line after hardware is salaries, but the ratio of personnel cost to revenue fell from 33% to 24% last year, suggesting early operating leverage.

Federal policy is tilting in Supernet’s favour. Islamabad has approved three IT special-technology zones offering 10-year tax holidays; the State Bank has relaxed foreign-exchange repatriation rules for tech exporters; and an IT-export strategy unveiled last year targets USD 10 billion by 2030. Minister of State for IT, Shaza Fatima Khawaja, recently told the Senate that she expects fiscal year 2025 exports to surpass USD 4 billion, implying a 27% annual jump. If realised, such growth could float all digital boats – including Supernet’s.

Still, currency volatility, patchy power supply and a fragile macro-economy temper the outlook. Pakistan’s sovereign rating remains deep in junk territory, and external financing hinges on successive IMF programmes. A slowdown in global tech spending or another bout of rupee weakness could squeeze both demand and hardware-import costs. n

By Abdullah Niazi

The privatisation of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) is playing out like a reality television show. The first round of bidding introduced some of the biggest businesses in Pakistan trying to outbid each other for control of the national carrier. Large, serious, conglomerates like the Lakson Group and Arif Habib Ltd locked horns with newer less conventional bidders like Blue World City also throwing their hat in the ring and raising their eyebrows.

That first season ended rather dramatically. When it finally came down to bidding, all of the consortiums that had qualified for bidding stepped back and Blue World City became the only group to submit the bid. Their bid was $36 million, which fell significantly short of the $305 million floor price set by the government.

The aftermath of the failed privatisation raised questions, not because it is unusual for the first round of bidding in a privatisation to go bust, but because of the massive gap that existed between the government and the consortiums that wanted to buy PIA. This also set up season two.

The privatisation of the PIA is a requirement of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), after all. In this strange reality show, the bidders are the participants, the government is the host, and the IMF is the all seeing Big Brother voice that makes the rules. The breakdown of last year’s bidding might have to do with a lack of trust between the host and the participants. When the bidding took place almost a year ago, the government was dealing with the Independent Power Producers (IPPs) with a heavy hand, and it was widely speculated that the treatment meted out to foreign investors spooked many of the potential buyers.

For season two, the IMF and the government have both tried to introduce some new rules that might make the participants stick around to the end. The main concerns last time were debt, staffing, and limited control. Essentially, the government wanted to keep a cut of the money for itself instead of pumping it into PIA, and it wanted a seat at the table to still have a say in how it was being run. This time around they have changed their tune, promising full divestment, scrapping the sales tax on

leased aircraft that became a massive issue in 2024, and is providing limited protection from legal and tax claims. Around 80% of the airline’s debt has been transferred to the state. All if this has had the explicit approval of the IMF.

As a result, eight bidders submitted their interest once again. Of these, five have become potential buyers. The cast of characters making up these bidders is a mix of familiar faces and new entrants. Some of the consortiums have shifted around. Perhaps most significantly, after last year’s failed sale, the entries of Fauji Fertiliser and Bahria Foundation as parts of different consortia indicate that the establishment does not want another failed sale. So who are the new potential buyers, and what is it that we can learn about PIA’s future from them?

In June 2024, almost a year to the date, eight bidders submitted their interest in buying PIA. Two of those bids were rejected, leaving behind six consortiums looking to buy the airline. The consortiums included a colourful combination of bidders.

Members of these consortiums include four different airlines, power producers, chemical manufacturers, and real estate developers. For the airlines, this was a matter of survival. Fly Jinnah, AirSial, Serene Air, and Air Blue were all part of these eight consortiums. Why would they be interested in buying an airline bleeding money and weighed down by debt? Even though PIA is badly run and making losses, it currently has the largest fleet and the largest domestic and international network in Pakistan. The national flag carrier is the market leader in Pakistan’s airline industry, and control of it means having a significant advantage over other airlines.

One of two things could happen for the other airlines operating in Pakistan. The first is that a conglomerate with an airline involved could take over and automatically become the market leader. The other option would be a conglomerate without any airline involvement to take over and a new entity is born and PIA’s position stays the same. In either case, the changes will shake up Pakistani aviation.

But changes are fast afoot. One of the leading conglomerates that seemed destined to get the PIA was FlyJinnah. The airline which took its maiden flight in Pakistan in October

2022 entered Pakistan’s market at a time when the aviation industry was struggling. They presented themselves as a low-cost carrier that allows you to pick and choose whether you want meals on flights and just how expensive your ticket is going to be. They have some powerful backers. In Pakistan, Fly Jinnah was the brainchild of the Lakson Group, one of the largest and oldest conglomerates in Pakistan.

The other big partner in this consortium was Air Arabia. In fact, AirArabia was involved because it already owns 45% of FlyJinnah. During the pandemic, Air Arabia was lobbying heavily with the UAE government to be allowed additional international flights to Pakistan but failed to do so. When the lobbying did not work, they decided to enter an alliance with the Lakson Group to form Fly Jinnah. And the response from within Pakistan’s aviation industry was not particularly welcoming. In fact, it was PIA that was most up in arms. Perhaps the biggest change from last year is that Fly-Jinnah and Air Arabia are nowhere to be seen. In fact, of the publicly reported bidders that are interested in PIA, there are only two airlines: Air Blue and Serene Air. Not only has Fly-Jinnah dropped out, AirSial is also no longer anywhere to be seen among those bidders that have come forward at this stage in the public eye. AirSial, much like FlyJinnah, is a newer airline on the scene. It took its maiden flight in 2020 and is an endeavour of the Sialkot business community, specifically the roughly 400 family-owned businesses that form the core of the Sialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SCCI). It is a story of enterprising business families banding together and building an airport to keep their city connected domestically and internationally.

AirSial had been part of a consortium led by Pak Ethanol, Dharki Power, and Serene Air. With AirSial out of the picture, Serene is now part of a new consortium that is being headed by the Bahria Foundation which is run by the Pakistan Navy. This is only one of the many changes in this year’s playing field. Profit has covered the previous bidders in detail in the past.

The current field has two airlines, two organisations that have military origins, and organisations that are from the cement, power, and real estate industries.

One of the strongest bidders in the field is Fauji Fertilisers. Founded in 1978, the company is one of the many subsidiaries of the Fauji Foundation. It is very important here to understand the distinction between the Fauji Foundation and the companies it owns. The story of the Fauji Foundation actually starts with a sum of $5 million left by the British in 1945 for the Indian veterans of the second world war.

The money was left in the Post War Services Reconstruction Fund (PWSRF) for Indian War Veterans, which remained unused and was divided between India and Pakistan in 1947 at the time of partition. The civilian administration transferred control of this still unused money to the Pakistan Army in 1954.

At the time, Pakistan’s share was around Rs 1.82 crore. Instead of distributing this remaining money, the army invested it in setting up a textile mill. Why would the army do this? Because there are essentially two kinds of charitable organisations. The first kind are the ones which for the most part collect donations and funds and spend those directly on charitable endeavours. They rely on a constant stream of donations. The second type is a little more complicated. These are organisations that operate as profitable entities. They undertake business and use the profits from these businesses to engage in charitable activities.

Fauji Foundation, set up under the Endowments Act of 1870, is the latter kind of organisation. Using that initial Rs 1.82 crore, the foundation has grown into a massive conglomerate that looks after the needs of retired servicemen and their families. For example, with the money they made from that first textile mill, the Fauji Foundation set up the first 50-bed tuberculosis hospital in Rawalpindi.

It is an entirely self-sustaining entity. Over time, the business interests of the Fauji Foundation have expanded including ventures in the fertiliser, banking, food, energy, and cement industries. Almost since the inception of Pakistan, the Fauji Foundation has been a point of pride for the armed forces and has been run by them.

As such, the Fauji Foundation is a well run charitable organisation that has grown and expanded its interests and has more money to spend on its original purpose. Fauji Fertiliser is one of their star companies. So if they manage to acquire PIA, the Fauji Foundation will have a sort of indirect control over the airline, since it is the major stakeholder in Fauji Fertiliser.

has approved the submission of an expression of interest (EoI) and pre-qualification documents to the Privatisation Commission for acquiring stakes in Pakistan

International Airlines Corporation Ltd, along with a comprehensive due diligence process. They are a late entry after he government last month extended the deadline to submit EoI for buying PIACL until June 19 from June 3 deadline with all terms and conditions remaining the same.

Arif Habib is one of the bidders that has stuck around from the last season. This time around, Arif Habib has formed a consortium with Fatima Fertiliser, Lake City, and The City School.

Arif Habib, of course, is a well known conglomerate and one of the leading business groups of Pakistan. The company has an extensive and diversified portfolio across all major business sectors including fertilizer,Financial services, construction materials, industrial metals, dairy farming, and energy. The interesting thing is that they have included Fatima Fertilisers, of which Arif Habib is the Chairman and which is part of the larger conglomerate, in the consortium. The City School, meanwhile, is a chain of private schools all across the country that offer English instruction and O/A levels programmes. They also have a deep network of franchise schools by the name of The Smart School all across the country, including in tier 2 and 3 cities.

However, the most significant member of this consortium from an influence point of view might be Lake City Holdings. This is the real estate company owned and operated by Gohar Ejaz.

Gohar Ejaz wears many hats. To most of the population, he is the man that shut down cellular phone and internet services on election day when he was a caretaker minister. At the time he was also significant to the business industry because he held the additional portfolio of Commerce Minister. To the world of real estate he is the man behind Lake City in Lahore. And to the country’s textile millers, he is their patron-in-chief and strongest advocate. In fact, it is that role in which he first made his mark. Well connected, and experienced in business, Lake City will bring a lot to the table.

Last time, Lucky Cement was a front runner. Their parent company, Younas Brothers Holding, formed a consortium with Pioneer Cement. Despite not having any aviation experience, this was the second major conglomerate to be in the ring.

BH has been around since 1962 when the foundation of a trading house was laid. The establishment of the fabric trading business

house, which turned into one of the largest business groups of Pakistan in a period spanning five decades. Among its subsidiaries, the group counts Lucky Cement.

This time around, they have joined hands with Hub Power Holdings Ltd, Kohat Cement Co Ltd and Metro Ventures. The big names with the money to spend will give Lucky Cement’s new consortium more strength this time around.

Another important bidder this time around is the Bahria Foundation. Founded in 1982, this is the foundation that the Pakistan Navy has for its veterans much like the Fauji Foundation. They have a number of interests including in deep sea fishing, coastal services, and harbour services. They also have diversified interests like in pharmaceuticals, paints, and even retail operations like a bakery.

They are joined in this consortium by domestic carrier Serene Air and US-based Equitas Capital LLC also submitted documents. Serene Air, which took its first flight in 2016, was part of a consortium with Air Sial and Pak Ethanol last year.

Along with all of these consortiums, others have also expressed an interest. This includes Air Blue, which was also in the bidding last year, along with Gerry’s International. What is important here is to see whether the government stays committed to the process this time around. Last year, it was a lack of confidence in the government that led to such an abject failure.

The PIA privatization, which is for between 51 percent and 100 percent of its shares and management control, is one of the conditions of the current IMF programme. A second failure could mean the sudden termination of not just the current programme, but also the $1 billion availed under the sustainability and relief fund. It would also mean that the government would have to keep on picking up PIA’s losses. It bodes well, though, that the airline turned its first profit in two decades in the only financial result since the last fiasco.

The government should realize that it is in a marketplace, and it is a seller of what potential buyers would dismissively describe as damaged goods. Everyone knows how desperately they want to make a sale, and how the buyers, even those who took part in the previous auction, are now looking for easy pickings. PIA is a national asset, and thus represents public investment. The people have a right to expect due diligence. n

The government’s policy is having the intended effect: Ittehad Chemicals is buying more electricity from the grid, albeit at the expense of a significant reduction in profits

When Ittehad Chemicals Ltd (ICL) released its calendar-year 2024 results this week, the headline numbers looked deceptively flat: revenue was broadly unchanged at Rs24.3 billion. Yet behind the still-water line lurked a decidedly choppier earnings story. Net profit slid 24% to Rs1.39

billion and earnings per share dropped from Rs18.26 to Rs13.86 as gross margin narrowed from 21% to 20%. Management placed the blame squarely on energy costs. A presidential ordinance issued on 30 January 2025 and subsequently converted into law imposed a five-per-cent “off-the-grid” levy on the already-inflated price of natural gas and RLNG consumed by captive power plants (CPPs). At the same time, the Ministry of Energy raised the gas tariff for industrial CPPs by a further 23% in March under International Monetary Fund pressure.

For ICL, which has historically relied on its own 35 MW gas-fired plant at Sheikhupura, the new regime inverted the cost equation: it is now cheaper to buy power from the Lahore Electric Supply Company (LESCO) than to self-generate.

ICL has therefore shifted the bulk of its demand to the grid, operating its captive plant only during peak hours when grid outages threaten production continuity – a move the company confirmed during its post-results briefing. While the switch mitigates the immediate gas levy, it drags profitability because

grid electricity incorporates capacity-payment surcharges designed to underwrite Pakistan’s oversized generation fleet. The twin forces explain why Ittehad’s gross margin deteriorated even further to 17% in the March 2025 quarter despite a 26% year-on-year rise in quarterly sales.

The squeeze on captive plants is no accident; it is central to Islamabad’s new energy policy. Two macro imperatives are at play. First, domestic gas supplies are depleting rapidly, compelling Pakistan to rely on far more expensive imported LNG. The Petroleum Division estimates that indigenous production will fall to 2.2 bcfd by 2027 against demand of nearly 6 bcfd, creating a gap that the state simply cannot afford to plug at subsidised prices. By taxing CPP consumption – and threatening termination of supply for persistent defaulters – the Off-theGrid (Captive Power Plants) Levy Act 2025 aims to push high-energy industrial users off

scarce pipeline molecules and free that gas for households and export-oriented firms with no alternative feedstock.

Second, the national grid is labouring under an opposite imbalance: too much capacity and not enough offtake. Installed generation has ballooned to 45.9 GW while off-peak demand can be as low as 7 GW, leaving utilisation near 34% and saddling the exchequer with Rs2.1 trillion of contractual capacity payments in fiscal year 2024. Shifting captive loads onto WAPDA-linked distribution companies such as LESCO helps amortise those idle megawatts and, in theory, allows the regulator to spread fixed charges over a thicker customer base.

Policymakers speak of the gas levy and capacity rationalisation in the same breath. The government cannot subsidise gas and pay for empty power plants at the same time. The levy, which begins at 5% and rises in phases to 20% by August 2026, is designed to make captive generation uneconomic relative to grid supply.

The numbers from ICL’s results offer a real-time laboratory of the policy’s effects. Total energy expense leapt 31% year-on-year to Rs5.94 billion in the March quarter, dwarfing the 26% increase in quarterly sales and compressing the quarterly gross margin to 17%. Finance charges also climbed as the company drew on working-capital lines to pay higher utility bills, though a fall in KIBOR during the half offset part of the impact.

In response, ICL is accelerating a 37.2 MW biomass-fuelled cogeneration project begun in February. Management expects the plant to be on stream in 18 months and to produce power 15-20% cheaper than the captive gas unit it will replace. That timeline, however, means at least five more quarters of grid exposure.

The company is also tweaking its product mix. Caustic soda still delivers a healthy 18-20% segment margin, but Linear Alkyl Benzene Sulphonic Acid (LABSA) – crucial for detergents – yields barely half that, making it highly sensitive to input inflation. ICL plans to commission a more efficient caustic flakes unit by April 2026, targeted at export markets insulated from Pakistan’s tariff regime, and has accelerated feasibility work for rooftop solar to shave peak-hour demand.

Ittehad traces its origins to 1962, when United Chemicals set up a 60-ton-per-day caustic soda plant near Lahore. Nationalised in the 1970s and later merged with Ittehad Pesticides, the complex was privatised in

1991 and listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange in 2003. Today the company operates Pakistan’s largest chlor-alkali chain outside the Engro group, with installed capacities of 150,000 tonnes for liquid caustic soda, 70,000 tonnes for LABSA/SLES and 13,200 tonnes for chlorine.

While its Sheikhupura site is inland, the firm has nonetheless built a modest export franchise in caustic flakes, zinc sulphate and bleaching earth, shipping through Karachi. The business employs about 680 people and supplies a who’s who of downstream users, from Unilever and Colgate-Palmolive to fertiliser giant Fauji. Its agribusiness division, launched in 2012, markets crystal zinc and humic acid fertilisers to Punjab’s citrus belt.

Crucially, the company has always prided itself on vertical self-sufficiency in utilities – first through a legacy furnace-oil plant, then through the 35 MW gas turbine installed in the early 2000s. That independence is now being methodically dismantled by federal policy.

By forcing ICL and scores of peer manufacturers to migrate from gas to grid, the government is achieving both of its macro goals: reduced gas burn and higher grid utilisation. Early data from the Petroleum Division show a 9% year-onyear decline in gas offtake by captive plants in the March quarter, while LESCO’s industrial sales rose 11% over the same period. The narrative therefore differs from the usual tale of unintended consequences: this time the pain is intended, albeit temporary.

ICL’s management accepts as much. The company believes that their biomass and solar initiatives would “restore margin parity” once completed. Analysts at Chase Securities reckon the gross margin could bounce back to 22% in fiscal year 2027 if biomass savings materialise.

Yet there is a delicate balance to strike. Over-reliance on expensive grid electricity risks hollowing out the competitiveness of Pakistan’s import-substituting manufacturers. The Pakistan Business Council argues that the levy should taper once capacity-payment obligations decline through PPA renegotiations, a process that started in late 2024 under IMF supervision.

For now, companies like Ittehad Chemicals serve as case studies in transition economics: squeezed today so that the broader energy system can breathe tomorrow. Whether that trade-off ultimately pays for itself will depend on how quickly the government can retire surplus megawatts – and how effectively firms can pivot to cheaper, greener fuels of their own making. n

The steel maker took over Ravi Textile in 2021 and is seeing stellar performance in its recent financials

By Zain Naeem

The cement building of Ravi Textiles in Kasur has always looked bleak. Its grey facade against the grey winter sky was always meant to be functional, not aesthetically pleasing. What made up for the drab exterior was a bustling and noisy factory where labourers toiled over machines manufacturing yarn.

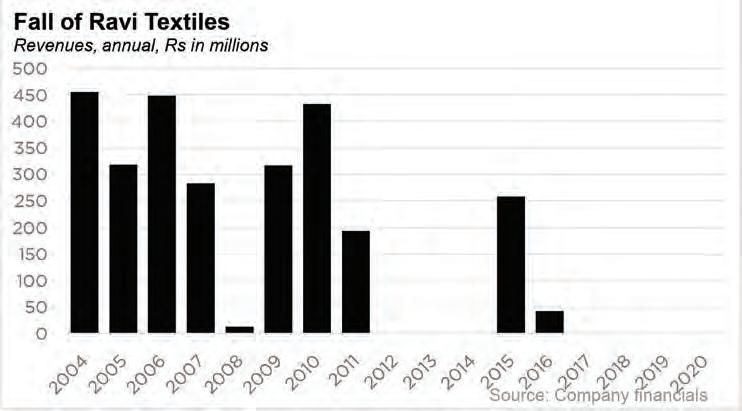

It was one of the many textile manufacturing units in the country that enjoyed a massive boom in the 1990s as Pakistan staked its claim as a textile exporting powerhouse, selling specialised products all over the world. But in 2021, when Muhammad Ali Shafique bought the company, the building had been gutted. The last time there was any activity there was in 2017, and since then Ravi Textiles was just looking for a buyer.

The rot had set in long ago. It had been struggling and running losses in the 2000s, and changed hands in 2008. That, unfortunately, was the year Pakistan went through an energy crisis which made it impossible for any new management to change things around at the textile mill. Why then would Muhammad Ali Shafique, whose family business was the booming Beco Steel, want to buy a doomed textiles company?

The textile industry was in a slump, the cost of doing business was too high and the accounts of the company were a picture of doom and gloom. Only one thing was going in Ravi Textile’s favour. It was a listed company trading on the stock exchange and Beco Steel wanted to get listed.

A reverse merger was carried out between Ravi Textile and Beco Steel which led to the creditors being paid off and much of Ravi’s assets being sold for scrap. What was left was a bare bone operation into which Beco Steel injected assets and equity in order to keep it afloat. Since 2021, it seems like Beco has emerged like a phoenix from the ashes of Ravi Textile. Today the floor of the foundry is lit by the fire and hiss of molten steel. Slowly, the company has managed to increase profits and the latest financials show that it is destined to have its biggest year yet. This is the story of how a reverse merger led to the listing of a star at the exchange.

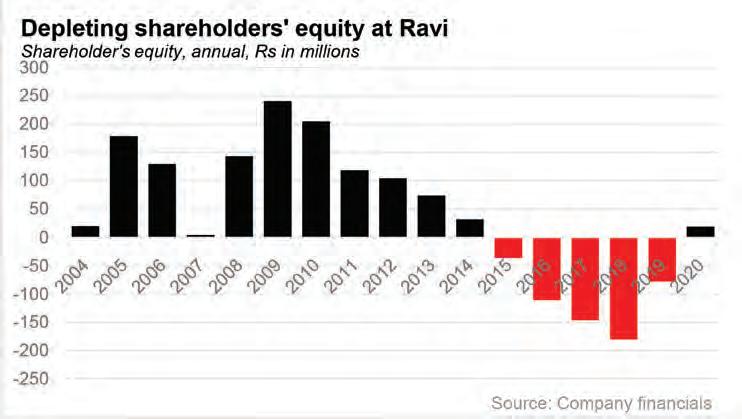

Even before the country was marred by the energy crisis of 2008, it seems like Ravi Textile was on a steady slope downwards. The earliest financials available for Ravi Textile Mills show an abysmal situation. Back in 2004, the company was earning revenues of Rs 46 crore from which it was only able to salvage gross profit of Rs 2 crores. After taking into account the other expenses, the company was making a loss of Rs 47 lakhs. This was compounding accumulated losses which

stood at Rs 10 crores. The only element salvaging a negative equity was the revaluation reserve which was Rs 4.3 crores. In order to plug in the gap caused by losses, the company had total liabilities of Rs 19 crores for an asset base of Rs 22 crores.

From 2004 to 2006, the primary focus seemed to be to generate gross profit in order to make the company viable. In 2007, this delusion was also shattered when the cost of production increased to such a degree that the company had to book a gross loss of Rs 2 crores leading to loss after taxation of Rs 7 crores. This seemed to be the last straw for the older management as the company was sold and taken over with a new management at the helm.

The first thing done by the new management was to inject more equity into the business of Rs 18 crores which provided a much needed relief to the shareholders’ equity.

The coming of the new management coincided with the energy crisis and rupee devaluation taking place. Both these factors meant that the cost of the company kept increasing. Even though direct costs were increasing, the company was able to turn a profit. The reason for this was that banks waived off long term financing of Rs 1.6 crores in 2008 while assets were sold for a profit of Rs 4 crores in 2009.

By 2009, the accumulated losses had gone to around Rs 18 crores while the revelation reserve had grown 4 fold from Rs 4 crores to Rs 16 crores. The injection of equity and revelation reserve led to the shareholders’ equity increasing to Rs 24 crores from Rs 2 crores in 2004.

The period from 2009 to 2011 was much the same as the cost of production was higher than the sales that were being made. As the losses started to pile up again, the accumulated losses went to Rs 13 crores by the end of 2011. This was the first year that the company saw its equity go into the red as its liabilities started to outweigh the assets. Due to the worsening situation, the creditors of the company did not renew the credit facility of the company. National Bank of Pakistan and Bank Alfalah also filed recovery suits against the company in the Lahore High Court.

The best course of action that could be taken was to shut down the production as it did not have the working capital to fund its operations. Even though this did not stop the losses being made, it did cut the flow to some extent and controlled some of the bleeding. By 2013, the going concern assumption also came under question and there was a high probability that the company would not be able to continue long into the future.

From 2012 to 2020, the company would see the plant restarting in 2015 and 2016, however, these years saw losses increase for the company. After the experimentation, it was decided to close down the company for good. One positive devel-

opment that did take place in 2018 was that Ravi was able to sell their fixed assets located in District Kasur to Waqas Rafique International for Rs 30 crores. These assets were also sold for a profit of Rs 11 crores which was able to improve profits in 2019 and 2020.

By the end of 2020, the accumulated losses stood at Rs 30.6 crores with shareholders’ equity of Rs 1.9 crores and total liabilities of Rs 13.5 crores. The fixed assets that had been sold were used to return the liabilities while the current assets of the company were valued at Rs 15.3 crores. Most of these assets represented cash that the company had on hand of Rs 14.8 crores. The new direction that Ravi wanted to take was to sell off assets in order to develop a new business plan that could be contemplated and executed for the future.

At this point, the only aces that Ravi Textile had in its pocket were liquid assets and its listing status. Ravi Textile was a listed company which was being traded on the stock exchange. 2021 was a year of reverse mergers where many of the defunct listed companies were being acquired by private companies. The goal of such a merger was that it would allow the unlisted company to use the listed status of the bankrupt company rather than going through the whole process of going public.

Chaudhry Steel Re-Rolling Mills and Beco Steel came to Ravi Textile and offered a price of Rs 3 crore at Rs 1.905 per share to take over the majority stake and control. Beco was able to transfer their own assets of Rs 3 billion to Ravi Textile and complete the merger. In order to raise the capital of Ravi, they would issue 101 millions shares at Rs 30 each in order to inject new equity into the company as well.

The same year saw Danish Elahi acquiring a majority in Mian Textile Industries and turning the business into a warehousing and logistics company. Similarly, Samin Textile was acquired by Waves SInger Pakistan to establish an e-commerce platform focusing on

home appliances. The objective of the reverse merger is to allow an unlisted company to become listed rather than going through the time consuming process of bringing their company into compliance and going through the Initial Public Offer (IPO) process.

Reverse merger is usually used by newly formed companies who want to get listed without having a track record behind them. Beco Steel is anything but new. The company stands at the heart of Badami Bagh in Lahore and has been a symbol of resilience and transformation. The company is currently led by Chaudhry Muhammad Ali Shafique who is the third generation steel manufacturer.

The roots of Beco Steel go back to before the partition of the country when Chaudhry Mohammad Latif built a company which represented the Muslims in the small village

of Batala. In 1932, the Muslims of Batala joined together to become self-sufficient in manufacturing the farm implements that they used. In less than 30 years, the company became Batala Engineering; going from nothing to being a behemoth that employed over 6,000 workers within it. One of the departments that was created under the company was its steel works which had a foundry, rolling mills and a machine shop.

While the tentacles of nationalization were able to take over Batala Engineering, the steel works were saved from the poisonous claws of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. The steel company was able to continue its operations while Batala Engineering was nationalized and ruined to what it has become today. The steel business passed down from one generation to the next and kept growing and gaining strength over time.

Based on the growth of the company, the logical step is to go public and become listed on the stock exchange. With a slew of defunct companies already listed, there was a shortcut available which allowed Beco Steel to buy the majority shareholding in Ravi Textile, transfer their assets and then get listed on the exchange. This was the path that was chosen in order to get listed.

By the end of 2021, many of the assets of Ravi had been sold and used to pay off liabilities that were pending. Current assets and fixed assets had been sold leaving behind a shadow of its former self leaving behind only Rs 46 lakhs of assets while much of the liabilities had been paid off leaving behind Rs 92 lakhs of liabilities. Even at this stage, the accumulated losses still racked at around Rs 30 crores which meant shareholders’ equity was negative.

As soon as the merger was carried out, the asset base of the new company expanded to Rs 4.5 billion as the assets of the steel business were added to the balance sheet. The liabilities of the new endeavour stood at Rs 1.2 billion as

well. In order to finance much of this expansion, the new shareholders had to issue new equity of around Rs 3 billion while they also provided a loan of Rs 22 crores to show their backing. The new company had a shareholders’ equity of Rs 3.4 billion and a new lease on life.

Beco steel had been a profitable business when it was operating as a private company and it could have been expected that the new company would instantly turn profitable. In its first year of existence, Beco Stell did rack up sales of Rs 6.3 billion which translated into a profit of Rs 19 crores for the company. The next two years were a struggle, however, as 2023 and 2024 saw the company making losses of Rs 20 crores and Rs 9 crores respectively.

The primary reason for this was the fact that cost of production was too high in 2023 and 2024 which saw gross loss of Rs 2 crores in 2023 and gross profit of only Rs 22 crores in 2024. Due to the magnitude of expenses that the company had to pay off, these turned into greater losses as the company was not able to maintain a good amount of margin on its products. The gross loss in 2023 and gross margin of only 7% in 2024 were not able to cover the expenses as the steel business took a dip in its initial years.

The reason behind the fall in performance in 2023 can be linked to the delay that was taking place in the approval of letters of credit which led to a sharp decline in the inventory. The situation became so dire that production had to be shut down temporarily. The economy was seeing a shortage of dollars and the government had put into place stringent measures targeting imports which impacted the sector.

Regardless of this, the confidence of the new management can be gauged by the fact

that the current assets of the new business were only worth Rs 1.5 billion in 2022 which increased to Rs 3.4 billion in 2024. Most of these were funded through current liabilities. The steel industry is a sector which is funded by working capital on a daily basis which means current liabilities are utilized in order to fund most of the working capital. The increase in current assets and current liabilities show that there is an expectation that the company will perform better in the future.

Now it seems that this confidence is paying off. The recent financials of Beco Steel is expected to have an amazing year as its nine month performance is the best in its history. Beco steel declared earning per share of Rs 1.62 for the nine months ended in March of 2025 where it had barely earned Rs 0.08 per share for the same period last year. With the year almost at an end, it can be expected that the year can be closed out at nearly Rs 1.75 per share of earnings.

The driver for the improvement in performance is the amount of sales carried out which were only Rs 2.8 billion last year and