18 26

18 26

10 Drug price deregulation has come to Pakistan. What will this mean?

15 The solar glut has come to Pakistan

18 The govt is becoming increasingly sophisticated about debt management. Is it too little too late?

22 Out of sight and out of mind, just like the brokers and investors like it

26 Zong had the headstart in 4G internet. How did it fall behind?

31 Toyota Indus Motors has seen a revival in demand. But is that the only reason for their rising profits?

32 Elphinstone, the startup that lets Pakistanis invest in US companies, has acquired Pakistani digital asset management company Trikl. But why?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Companies can finally raise prices, which is likely to result in higher prices, but also likely to mean fewer shortages of essential drugs

By Zain Naeem

In early 2022, there was a severe shortage of paracetamol, and of course, the blame game began as to who might be responsible. Some members of the Pakistan Young Pharmacist Association (PYPA) seized headlines, boldly accusing drug manufacturers of intentionally orchestrating a paracetamol shortage. What did they allege was the drug companies’ motive? To coerce consumers into buying a pricier, higher-dose variant of 665 mg, rather than the standard 500 mg. While the accusation may have added intrigue to an otherwise familiar dilemma, it highlighted a deeper issue in Pakistan’s healthcare: the chronic, and at times crippling, scarcity of essential medicines.

For decades, the state has attempted to keep medicine prices low, ostensibly to aid citizens but, arguably, more as a populist pitch for votes. The results of this paternalistic approach are exactly what one might expect: drugs vanishing from shelves, poorer quality substitutes, and profits evaporating for companies brave (or foolish) enough to stay in the game. Many have simply packed up and left Pakistan altogether. The result? Both consumers and producers end up as collateral damage in the policymakers’ convoluted strategy.

Drug shortages are no stranger to Pakistan. Each year, key medications become elusive, pushing patients to either seek costly imported versions or turn to black-market alternatives. A recent survey by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics found that in Rawalpindi and Islamabad alone, 48 registered drugs were absent from pharmacies, and 67 others were in critically short supply. The scarcity of medicines is not a new phenomenon; in fact, it dates back to Pakistan’s early days. During a 1954 Constituent Assembly session, members decried the severe shortages, prompting the Health Minister to promise relief through imports. Fast forward to 1976, and Arthur Homer Furnia, an American health sector analyst, noted that public healthcare facilities were suffering due to chronic pilfering of medicines.

Today, Pakistan is home to around 750 pharmaceutical plants—vastly more than the near-nonexistent capacity of 1954, or even the fewer than 100 manufacturers present in the 1970s. But despite this growth, the shortages endure. So, what fuels this perpetual drought of essential drugs?

The answer lies largely in Pakistan’s strict regulatory framework, which has had

unintended consequences. The government’s pricing policies are especially restrictive, and the nation’s dependency on imported raw materials makes matters worse. With 95 per cent of pharmaceutical ingredients imported, the industry is at the mercy of global supply chains. A disrupted global supply can easily translate into domestic shortages, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

At present, not a single one of the roughly 1,200 active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is manufactured locally; Pakistan’s dependency on foreign imports is complete. Meanwhile, the rupee’s depreciation has led to steep increases in the cost of these imports, yet government pricing policies hold drug prices—and thereby profit margins—in a tight grip. Politically, price increases are highly sensitive, and successive administrations have hesitated to adjust them. The result? When raw material costs surged, as they did recently for paracetamol, rising from Rs. 600 to Rs. 2,600 per kilogram, manufacturers found it unsustainable to keep production going. Production ground to a halt, and consumers, once again, were left at the mercy of the black market. Finally, the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) proposed an increase in paracetamol prices, yet this remedy remains stuck at the Cabinet level.

The ongoing shortage of Panadol tablets has led to peculiar scenes, such as the confiscation of 27,000 boxes in Peshawar. Media outlets swiftly blamed a so-called “drug mafia,” implying that manufacturers and distributors were colluding to create scarcity. However, while conspiracy theories abound, a sober look reveals that the driving factors are far more prosaic: outdated pricing models and the high costs of imported raw materials.

Faced with government inaction, pharmaceutical companies have responded creatively. One strategy is to shift production towards higher-dose medications, such as the aforementioned 665 mg Panadol, whose higher price can better offset production costs. Another workaround is to cease manufacturing certain drugs, only to reintroduce them under new brand names or categorise them as “nutraceuticals,” which are less tightly regulated, allowing for a broader pricing margin. Lastly, some lower-quality producers go one step further by selling raw materials at black-market prices or smuggling them—a practice vividly illustrated by the recent seizure of Rs34 billion worth of ketamine, destined for export.

In short, while Pakistan’s perennial drug shortages are often framed as a case of market manipulation, the true culprits are an outdated regulatory framework and an overreliance on imports.

Historically, Pakistan’s drug pricing policies have been tightly controlled. The entire pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan is regulated by the government under a legislative framework first created by the 1966 Drug Act, which also created the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP).

DRAP has introduced pricing policies first in 2015 and then in 2018 that were designed to ensure that pharmaceutical companies are able to continue to make profits on their products while also not increasing the prices too much for the public. Coming as it did after a 15-year effective moratorium on drug price increases, that change was considered welcome by the industry.

But the structural problem was this: the government used to set both the retail price as well as the retailers’ margins, which effectively means that gross profit margins for the entire industry are set by regulatory fiat. The manufacturer is able to receive a price between 20% and 25% below the retail price, which meant that the entire supply chain operated on margins contained in that 25% margin.

Pharmaceutical companies argued that they need both patent protection for the newly researched drugs that they have produced, as well as the ability to charge whatever prices they deem fit in order to be able to cover the cost of the research and development that goes into producing new and innovative therapies.

Critics of the pharmaceutical industry argued that pharmaceutical products are not like other products where a consumer has many other choices, including the ability to choose not to buy the product. A life-saving product is something that the person who needs it values very highly and would be willing to pay even extortionate levels of prices to secure access to something that will keep them alive. But it is in society’s interest that as many people as possible have access to the healthcare products they need, and hence they advocate for price controls.

The approach advocated by the pharmaceutical companies is one adopted pretty much only by the United States. Virtually every other country in the world has some form of price controls over and above any public health insurance program they may have. That means that most countries not only offer free or highly subsidized healthcare to their citizens, they also force the pharmaceutical companies to charge prices determined by government bureaucrats, and not the market.

In effect, this means that the large multinational pharmaceutical companies –whether they be American or European – make

their money in the United States to help pay for the research and development activities they conduct for breakthrough therapies. The United States is subsidizing the development of advanced treatment for the whole world.

Pakistan has historically been like almost every other country in the world in that it has government-mandated price controls for pharmaceutical products. And the government not only mandated the initial price, it mandates just how much they can go up each year, and how much each participant in the supply chain is allowed to keep as their profit margin.

The recent deregulation marks a significant shift. For the first time since the Drugs Act of 1976, pharmaceutical companies will have greater autonomy in setting prices for non-essential drugs. This decision, welcomed by the industry, is seen as a necessary correction to years of stifling regulation that left companies struggling with unsustainable profit margins amid rising production costs and a devaluing rupee.

Yet, the move has not been without controversy. Critics argue that deregulation could lead to skyrocketing prices, placing essential medicines out of reach for the average Pakistani. The Lahore High Court’s decision to stay the deregulation on February 22, 2024, was the predictable populist response to the deregulation. The stay order was then vacated on April 5, 2024.

The issue is emblematic of the broader challenges facing Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry. The country’s reliance on imported raw materials, coupled with high inflation and currency devaluation, has squeezed profit margins to the point where companies are forced to either cut production or absorb losses. The case of Panadol—a widely used pain and fever reliever—illustrates this dilemma. Production was slashed, leading to widespread shortages, after GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare

(GSKCH) struggled to secure a price increase in line with rising production costs.

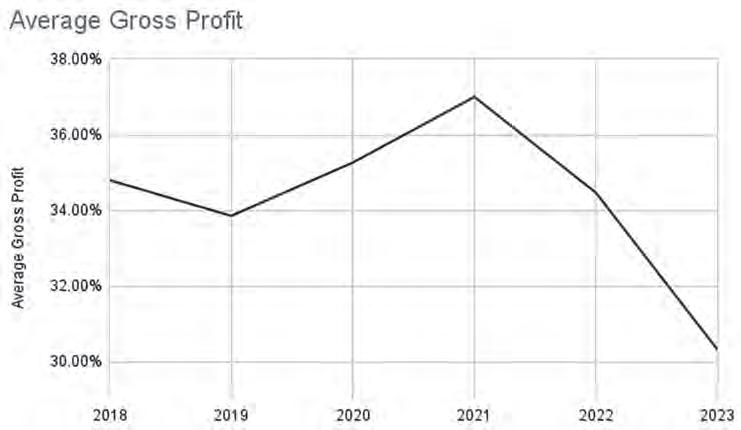

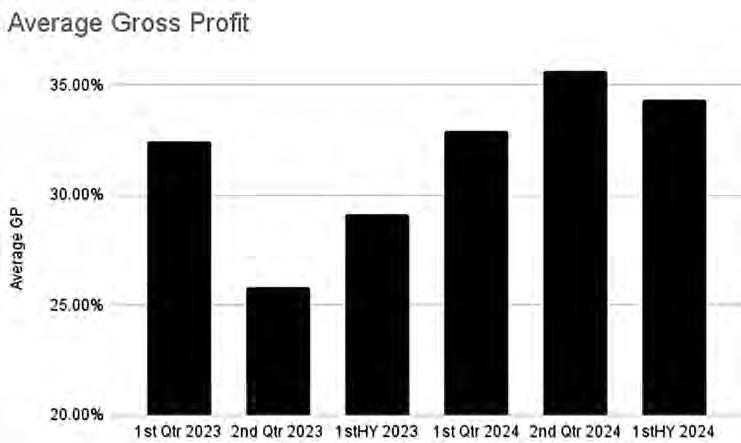

In February 2024, the government’s new policy finally allowed manufacturers of non-essential drugs to adjust prices without DRAP’s cumbersome approval process. The early results have been encouraging, with profit margins rebounding across the board. By the first quarter of 2024, the industry’s average gross profit margin had risen from 32.4% to 33%, with standout improvements from GlaxoSmithKline, which saw margins rise from a paltry 7% to a healthier 14.5%.

The real growth occurred in the second quarter, with average gross margins leaping from 25.8% in 2023 to 35.6% in 2024, fully reflecting the new freedom to adjust prices. And this, despite the fact that the rupee has not regained its strength, hovering around Rs276

to the dollar.

The positive ripple effects are being felt across operational metrics, with operating margins climbing from 7.8% in the first half of 2023 to 12.7% in the same period of 2024. Such data is manna from heaven for the industry, signalling a rare alignment of economic viability and regulatory support. Even the beleaguered Searle Pakistan, which had booked losses in the previous year, saw substantial improvements in profitability. It’s a testament to the power of deregulation, albeit within limits.

However, the government’s cautious approach—retaining control over essential drug prices—suggests an awareness of the pitfalls. Complete laissez-faire pricing in the pharmaceutical sector could be perilous, creating barriers to essential medicines for the nation’s poorer citizens. The balance, then, is a delicate one: should policymakers push further toward deregulation, prioritising industry sustainability, or focus on affordability at the risk of repeating past mistakes?

The past shows that Pakistan’s experiment with price controls has consistently failed to deliver a stable drug supply and maintain product quality. And, as every economist will attest, price controls are rarely a path to efficiency or growth. The notion that private companies will happily operate at a loss to benefit the common man is as fanciful as it is dangerous. When forced to produce at low margins, manufacturers either cut quality or leave entirely—both outcomes that hurt consumers.

The most deregulated drug prices in the world exist in the United States, a market where until recently even the government’s own insurance

programs were forbidden by law to negotiate drug prices with manufacturers, let along have price controls of any kind. Ask the pharmaceutical lobby in the United States why they push for such regulations, and their answer will be simple: the high drug prices pay for innovation.

This then raises the big question: could allowing higher prices result in more innovation among pharmaceutical products within Pakistan. The answer is – tentatively – a maybe. Perhaps it is no coincidence that earlier this year, very shortly after the deregulation of drug prices, Ferozons’ Laboratories’ subsidiary BF Biosciences has successfully launched its first human insulin drug under the brand name Ferulin. This drug is the first biosimilar to be launched in Pakistan that addresses diabetes, one of the most prevalent diseases in Pakistan.

A biopharmaceutical, also known as a biological medical product, or biologic, is any pharmaceutical drug product manufactured in, extracted from, or semisynthesized from biological sources, as opposed to other drugs that are manufactured through a chemical process.

Candidly, while some of this kind of innovative drug may become a bit more available in Pakistan after drug price deregulation, it is highly unlikely that Pakistan will become a hub of pharmaceutical and life sciences innovation for the simple reason that the global market for such innovation is highly skewed and concentrated almost entirely in the United States.

Even some of the largest, most profitable European and Japanese pharmaceutical and life sciences companies do a substantial proportion of their clinical trials in the United States and count the US launch of their products as its true global launch since America is where pharmaceutical companies sell their

products in order to actually get paid.

Pakistan deregulating is prices is a drop in the bucket for global pharmaceutical companies, and while it certainly will help alleviate the shortages problem, it is unlikely to make Pakistan a major hub of pharmaceutical innovation.

What it may do, however, is make Pakistan part of the global drug discovery and research supply chain by make it more financially viable to also conduct clinical trials in Pakistan.

We have already had a small taste of what that could look like during the 2020 global pandemic, when some of the drug trials for one of the most effective drugs against Covid-19 – Remdesivir – were conducted in Pakistan. The existence of those drug trials in Pakistan for a cutting edge drug meant that Pakistanis got access to such technologically advanced pharmaceuticals well before one might have expected Pakistan to get access to such drugs.

In this realm, one of the most important partnerships for Pakistan’s economy is that between Gilead – the American life sciences giant – and Ferozsons Laboratories, the Pakistani pharmaceutical manufacturer. Gilead develops highly innovative, but very expensive, products and is willing to market them in Pakistan for much lower than its US prices in partnership with Ferozsons.

But even though the prices are much lower than the US, they are still higher than what might have been allowed under the older, more restrictive pricing regimes. A more relaxed regime might mean we get access to better, more innovative products, faster.

What might work is a shift towards a flexible pricing model that considers inflation, raw material costs, and the rupee’s depreciation. A regulatory framework that allows prices to adjust within reason, with state intervention reserved for monitoring quality and supply, may be a more viable solution. Allowing companies to function without arbitrary pricing hurdles is, after all, essential for sustaining a high-quality pharmaceutical sector.

The financial results following the 2024 deregulation provide ample evidence that the industry can rebound if given breathing room. But there’s no room for complacency. Pakistan’s policymakers must tread carefully to avoid the past’s paternalistic pitfalls while recognising the necessity of profitability for the nation’s health sector.

For now, deregulation has indeed injected a dose of vitality into the pharmaceutical industry, reversing years of policy-induced malaise. Whether it will also prove to be the cure for Pakistan’s deeper economic ailments remains to be seen. n

By Ahtasam Ahmad

Pakistan’s power sector is a cautionary tale of economic mismanagement. Like a patient on perpetual life support, it survives only through massive government subsidies and stopgap measures, prompting renowned economist Dr. Atif Mian to label it a “zombie sector” – an apt metaphor for an entity that continues to drain the nation’s resources while showing few signs of life.

In response to this crisis, the government has reached for what it hopes will be a cure: aggressive renegotiation of contracts with Independent Power Producers (IPPs). But even as headlines focus on these high-stakes confrontations, a more fundamental transformation is quietly unfolding across Pakistan’s urban and industrial landscape. Frustrated by soaring electricity costs and persistent outages, consumers are increasingly turning to solar panels, abandoning their reliance on the national grid.

This solar exodus presents policymakers with an unprecedented dilemma. Each new solar installation, while offering relief to consumers, potentially undermines the very reforms meant to save the power sector. The government now finds itself walking a precarious tightrope – attempting to preserve grid sustainability while respecting consumers’ right to choose cheaper energy alternatives.

As this crisis deepens, one question looms large: Can the government’s efforts to resurrect the power sector succeed in the face of this accelerating solar revolution? Profit explores the ramifications of these trends on Pakistan’s energy future.

The current power sector crisis is not the result of a sudden collapse but rather a systematic failure years in the making. At its core lies a fundamental disconnect between supply and demand, exacerbated by a series of misguided policy decisions that have prioritized quick fixes over sustainable solutions. Pakistan’s

installed power generation capacity currently stands at approximately 45,000 megawatts (MW), substantially overshooting the peak national demand of around 30,000 MW - a disparity that epitomizes the sector’s fundamental inefficiency.

This mismatch between supply and demand has created what experts call a “capacity trap,” where fixed costs for unused investments, often denominated in US dollars, continue to accumulate, driving up the per-unit cost of electricity. The government’s historical approach of attracting private investment through risk transfer has led to generation costs 87-140% higher than in neighboring countries, standing at approximately $0.13 per kilowatt-hour (kWh).

Beyond generation capacity, Pakistan’s power infrastructure suffers from fundamental transmission inadequacies. The existing grid struggles with geographical disparities, dubbed the “south-north barrier,” and an aging infrastructure prone to failures. Paradoxically, while grappling with overcapacity, the country simultaneously curtails more economical renewable energy sources due to grid limitations. These transmission constraints create a bizarre situation where some regions face power shortages while others have surplus capacity they cannot distribute effectively.

At the heart of this dysfunctional system lie the independent power producers (IPPs), which have evolved from being a solution to becoming part of the problem. These private companies now constitute 55% of the country’s total power generation capacity, with merely 10 major IPPs responsible for over half of the sector’s output. However, their contribution extends far beyond mere electricity production - they have become a significant economic burden.

The IPP model, originally conceived to attract private investment in a power-starved economy, has mutated into a system that guarantees returns regardless of actual electricity generation. Capacity payments - funds paid to power producers for maintaining generation readiness - have become a primary mechanism of financial transfer, with the top 10 IPPs receiving 40% of these payments. More alarm-

ingly, these same producers account for 25% of Pakistan’s circular debt, a cascading financial challenge where unrecovered electricity costs create a perpetual economic strain.

The distribution of power generation among IPPs is notably skewed. While 10 major IPPs control 53% of the total IPP capacity, the remaining 90 IPPs share the other 47%.

Despite their significant capacity, some larger IPPs deliver only a fraction of total grid electricity sales yet continue to receive substantial capacity payments, creating an unsustainable financial burden on the system.

Recognizing the unsustainability of this model, the government has initiated a bold restructuring effort. Five IPP contracts have been terminated, with authorities claiming potential savings of approximately Rs411 billion and a projected reduction of around Rs0.72 in electricity tariffs. An additional 18 IPPs, collectively representing 4,267 MW of capacity, are under negotiation, with the government seeking to transition from a “take or pay” to a “take and pay” contractual model.

The government’s tariff reduction strategy appears comprehensive on paper. The Power Minister has outlined plans to reduce tariffs through multiple interventions: negotiations with local IPPs (targeting Rs3.5 per unit reduction), debt reprofiling of Chinese IPPs (Rs3.75 per unit), surcharge adjustments (Rs0.75 per unit), and IPP contract closures (Rs0.72 per unit). Additional measures, such as removing the television fee from electricity bills, could contribute another Rs0.16 per unit reduction. In total, these measures aim to achieve an Rs810 reduction per unit, representing a 25-30%

in the national average base tariff. However, this approach carries sig-

nificant risks. The aggressive restructuring potentially undermines investor confidence in Pakistan’s energy sector, a reputation already fragile from years of inconsistent policies.

More importantly, these cost-side reforms might be fundamentally undermined by a transformative force that the government appears to have overlooked: the solarization drive.

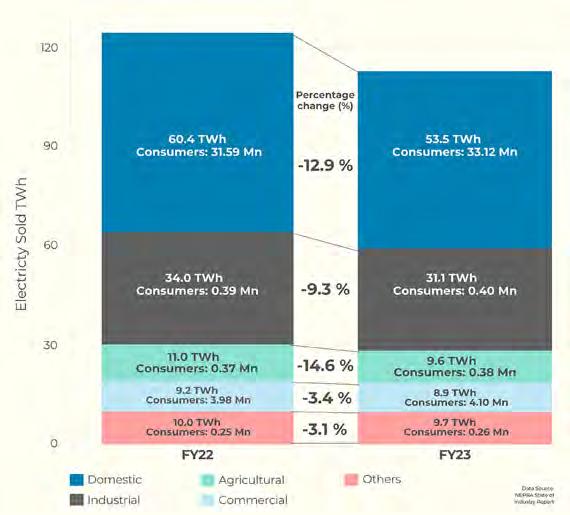

As the government grapples with traditional sector reforms, a quiet revolution is unfolding across Pakistan’s energy landscape. Recent data reveals a stunning trajectory - in fiscal year

2024 alone, Pakistan imported solar panels worth 2.1 billion dollars, with a generating capacity of around 15,000 megawatts. This represents approximately one-third of the national grid capacity, and if the trend continues, solar PV could soon approach half of the grid’s capacity.

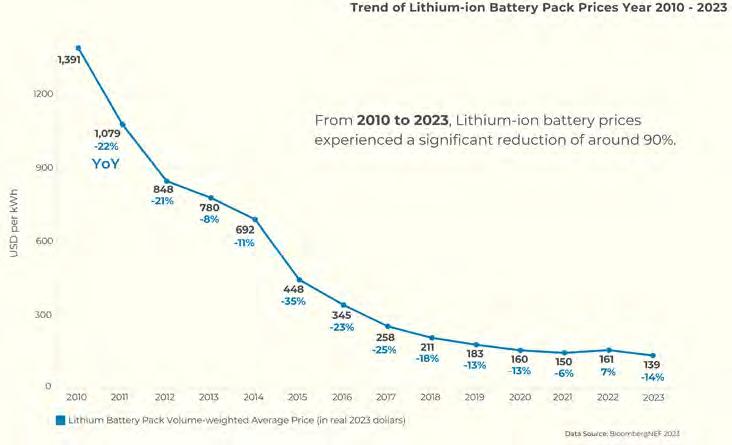

This solar surge is driven by compelling economic logic. With electricity costs continually rising (155% in the past three years), consumers are increasingly turning to alternative energy solutions. The current net metering policy, which offers a payback period of merely 2-4 years, makes solar investment extraordinarily attractive. As battery prices plummet globally and China floods the market with affordable solar and battery technologies, the grid’s traditional monopoly is rapidly eroding.

demand over the past two years has led to around Rs5 in tariff hikes. The first quarter of the current fiscal year has already seen an 8% decrease in power generation, and with the high influx of solar equipment awaiting deployment, grid electricity demand patterns are likely to deteriorate further.

As Pakistan stands at this critical juncture, the power sector’s future hangs in a delicate balance. While the government focuses on IPP restructuring and tariff reductions, the rapid adoption of solar technology suggests a more fundamental transformation is already underway. The traditional centralized power model, with its inefficiencies and high costs, is being challenged by a more distributed, consumer-empowered energy ecosystem.

The challenge for policymakers is no longer just about fixing the existing system but about adapting to an entirely new energy paradigm. The government’s cost-side reforms, while necessary, may prove insufficient in the face of this technological disruption. Success will require a holistic strategy that not only addresses historical inefficiencies but also embraces and integrates the emerging decentralized energy future.

The integration of solar power into Pakistan’s national grid isn’t just desirable – it’s imperative. With solar panel costs in free fall and battery prices following suit, the momentum behind solar adoption is becoming unstoppable. Already, net-metering policies have slashed the payback period for grid-connected solar systems to a mere two years, making the switch to solar less a matter of environmental consciousness and more one of simple economic sense.

The implications of this shift are profound and potentially devastating for the traditional power sector. The phenomenon, known as the “utility death spiral,” occurs when rising electricity costs prompt consumers to seek alternatives, which in turn reduces grid consumption, further driving up per-unit costs. IPPs themselves acknowledge a 22% fall in electricity

But rather than resist this transformation, the government needs to embrace a twopronged strategy. First, modernize the grid infrastructure through aggressive digitization and strategic battery storage deployment to handle the intermittent nature of solar power. Second, and equally crucial, address the demand side of the equation. This means both wooing back industries that have retreated to captive power generation and cultivating new sources of demand – particularly from the emerging sectors like electric vehicles.

For Pakistan, this moment represents both a crisis and an opportunity. The solar surge offers a pathway to more sustainable and affordable energy access. However, managing this transition while addressing the legacy issues of the power sector will require careful balance. The nation’s energy future will depend not on the inertia of past policies, but on the vision and adaptability of its current leadership in navigating this complex transformation. n

The govt is becoming increasingly sophisticated about debt management. Is it too little too late?

The 2024 fiscal numbers reveal a transient debt management strategy driven by enhanced liquidity. But eventual success rests on long term reforms and global economic conditions

By Mariam Umar

There are, very basically speaking, two different tools at the disposal of any government to manage the economy. The first is fiscal policy, which essentially is how the government chooses to implement and collect taxes and then spend them. It is a pretty simple operation. The government needs money, and it gets it through taxation. The more it is able to collect, the more it can spend (or save).

And then there is the second tool. Monetary policy. Economists will lecture you for hours about the importance and nuance of how a country’s monetary policy is controlled by its central bank or federal reserve or whatever terminology a state has for its banking regulator. But essentially, monetary policy is essentially a massive lever. Pulling it can either increase or decrease the interest rate, thus determining how cheap or expensive it is to borrow.

The trick that every government has had for the past century has been balancing these two sides. In countries like Pakistan, where debt obligations are overwhelming, governments often respond by trying to completely control and dominate both these tools.

Pakistan stands as a stark example of how this situation can deteriorate if left unchecked. This phenomenon has become increasingly pronounced in emerging economies where the line between fiscal and monetary policy grows increasingly blurred, often at the expense of economic stability and growth potential.

Between fiscal years 2022 and 2024, Pakistan’s economic landscape has been particularly challenging, with domestic debt forming a significant portion of the government’s total liabilities.

This predicament has forced three major consequences upon the country’s economic decision-makers:

1. Record-high interest rates to protect the currency and control inflation

2. Paralysis of the financial sector leading to private sector credit crowding out

3. A broader loss of confidence among investors and workers

The ripple effects have been felt across all sectors of the economy, from small businesses struggling to access credit to large corporations facing increased borrowing costs.

Recent developments present a contradictory picture. On one hand, interest rates are declining at an unprecedented pace, with the State

Bank of Pakistan (SBP) expected to announce another significant rate cut of 1.5% to 2%.

The fiscal accounts show promise, with Pakistan posting a substantial fiscal surplus of Rs 1.69 trillion (1.4% of GDP) and an impressive primary surplus of Rs 3 trillion (2.4% of GDP) during the first quarter of fiscal year 2025—a feat not achieved since fiscal year 2004’s second quarter. However, the SBP’s ‘State of economy report’ for fiscal year 2024 paints a more sobering picture of the previous fiscal year’s challenges. This dichotomy raises questions about the sustainability of recent improvements and whether they represent genuine structural changes or temporary relief.

Prior to 2019, the SBP directly financed government deficits, a practice that while convenient, fueled inflation. By mid-2019, direct financing was discontinued, and the IMF’s intervention in 2021 led to a permanent ban through the 2022 SBP Act. This shifted the financing burden to commercial banks, resulting in interest rates soaring from 7% in September 2021 to 22% by June 2023. The transition, while necessary for long-term economic stability, has created new challenges in terms of debt servicing costs and market dynamics.

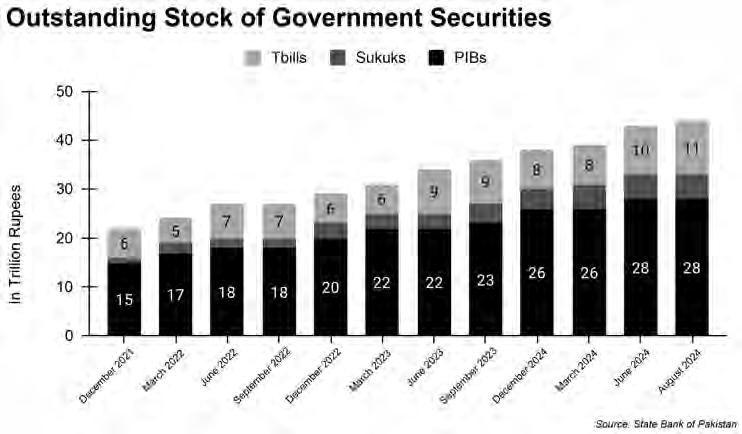

By the end of fiscal year 2024, Pakistan’s domestic debt had reached Rs 47.2 trillion, increasing by another Rs 1 trillion within the first two months of fiscal year 2025. Commercial banks have been the primary financiers, leveraging borrowing from the SBP through Open Market Operations (OMO). This has led to a significant increase in money supply, with M2 reaching Rs 36.6 trillion by June 2024. Of this, currency in circulation stood at Rs 9.2 trillion (25% of money supply), while out-

standing OMOs amounted to Rs 11.9 trillion. The rapid expansion of monetary aggregates has raised concerns about the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission mechanisms. The banking sector’s role in domestic debt financing has been particularly prominent over the past four fiscal years, with a brief exception in fiscal year 2023 due to an additional tax based on banks’ advance-to-deposit ratio. When this tax was suspended in fiscal year 2024, banks returned to heavily investing in government securities, with their funding more than doubling to Rs 8.6 trillion. This behavior has created a complex web of interdependencies between the banking sector and government finances, potentially increasing systemic risks in the financial system. The concentration of bank assets in government securities has also raised concerns about the sector’s ability to fulfill its primary role of financial intermediation and support private sector growth.

Key players in this financing mechanism include United Bank Limited (UBL), National Bank of Pakistan (NBP), and Pak Kuwait Investment Company. UBL alone accounts for one third of SBP’s outstanding OMOs, which stood at around Rs 12 trillion as of September 2024. This concentration of exposure among a few institutions presents potential systemic risks that warrant careful monitoring.

Fiscal year 2024 marked a strategic pivot in debt management as the government transitioned from shortterm, high-cost securities to longerterm investments, aiming to reduce rollover risk and borrowing costs. This shift led to increased borrowing through floating-rate Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIBs) and Sukuk, with amounts rising to Rs 6,016.5 billion and Rs 1,615.6 billion respectively, compared to the previous year’s figures. The move towards

longer-term instruments represents a more sophisticated approach to debt management, though it comes with its own set of challenges, including interest rate risk in a volatile economic environment.

As banks prioritize government bonds, their responsiveness to fluctuations in interest rates may diminish. Even in a scenario where interest rates are on a declining trend, banks may continue prioritizing government bonds in anticipation of capital gains. As a result, reductions in policy rates could lead to decreased lending, crowding out the private sector and undermining the intended impact of monetary policy on borrowing and economic activities.

The government’s recent attempts at debt management show increasing sophistication. As fiscal year 2025 progresses, strategic adaptation

through T-bill buybacks, including a recent Rs 351 billion operation, has saved an estimated Rs 11.61 billion in debt servicing costs. The average time to maturity of domestic debt has improved to 3.0 years in fiscal year 2024 from 2.8 years in fiscal year 2023, reducing rollover risk.

The trend has continued and in the latest T-bill auction, the ministry of finance paid back Rs 200 billion of T-bills which carried an interest rate of around 15% and in parallel, raised 820 billion through new issuance of T-bills at a rate of around 13%.

Due to the access to liquidity available with the central bank, the government is able to retire a large part of its domestic debt which is signified by the fact that the borrowings from domestic banks is down to around Rs 9.3 trillion from the high of 12 trillion.

These measures demonstrate a more proactive approach to debt management, though their long-term effectiveness remains to be seen.

However, the fundamental challenge remains: nearly 50% of the fiscal year 2025 budget is allocated to debt servicing. When combined with unfunded pension commitments and sovereign guarantees, particularly in the power sector, Pakistan’s economic profile remains concerning. The intricate relationship between the SBP, commercial banks, and the government continues to shape the country’s economic trajectory, suggesting that the path to recovery will be far from smooth. This situation is further complicated by external factors such as global economic uncertainties, geopolitical tensions, and the ongoing challenge of maintaining foreign exchange reserves.

Looking ahead, Pakistan’s ability to break free from fiscal dominance will depend on several critical factors: successful implementation of structural reforms, broadening the tax base, improving the efficiency of stateowned enterprises, and developing a more diverse and competitive financial sector.

The first signs of it are there. The fiscal surplus alluded to earlier was a result of the government revenues increasing by 117% year on year while the expenses being controlled as the growth was only limited to 13%. This was largely due to a couple of factors, the SBP dividend came in this quarter which pushed the revenues abnormally high and due to the freefall of the yield on government securities, the domestic debt servicing costs are down by 5%.

However the next quarter remains challenging with no abnormal revenue injection and upcoming T-bill retirements, the government is also likely to have a hard time squeezing the tax revenue out of businesses as the surge of positive sentiments due to IMF deal closure and the uptick in the activity around the stock market. However, as this short-term optimism waves off, the government would have its work cut out.

Therefore, the government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation and debt sustainability will be crucial, as will the continued support of international financial institutions and bilateral partners. The challenge lies not just in managing the current debt burden but in creating conditions for sustainable economic growth that can gradually reduce the country’s reliance on debt financing.

The experience of Pakistan serves as a cautionary tale for other developing economies about the risks of fiscal dominance and the importance of maintaining clear boundaries between fiscal and monetary policy. It also highlights the need for robust institutional frameworks that can ensure fiscal discipline while supporting economic growth and development. As Pakistan continues to navigate these challenges, the outcomes of its current policy choices will provide valuable lessons for other countries facing similar economic pressures. n

By Zain Naeem

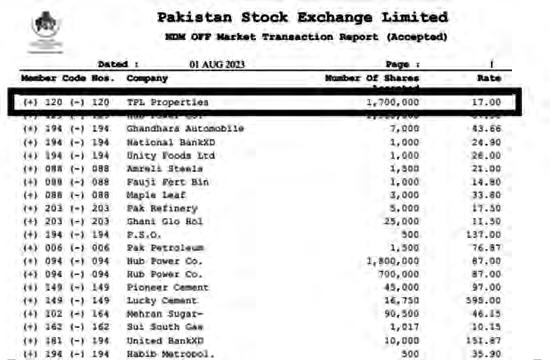

Most people, at the least, have heard of the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) and the KSE100 index. Some are even aware of the fact that there is an odd lot market and a futures market that works in parallel to the stock market itself (don’t worry if this has come as a news to you). However, even fewer people are aware of the existence of a Negotiated Deal Market (NDM) and how it works.

Let’s get some of the basics out of the way. A negotiated market is a secondary market set up by the exchange itself. The purpose of the market is to allow a buyer and seller to be able to negotiate the terms of the deal away from the market. They can carry out a trade based on the terms that are suitable to the both of them. Such a

trade can be carried out between two brokers who are operating in the market or between two clients who can be facilitated through brokers as well.

On the face of it, such trades are seen to be time consuming, require additional effort and are not transparent in their nature. The prices set for these trades can vary from the prevalent market price. Trading is supposed to be simple, clear and fast but trades carried out in the NDM market feel like they are arduous and the price discovery lacks transparency. It is this lack of transparency which makes these trades intriguing and can even give an impression of being unfair or inequitable to the market.

One of the binding conditions of such a trade is that the quantity and price that has been set has to be adhered to. That means the trade is only executed when both buyers and sellers agree

on the price and the number of shares. It is an all-or-nothing trade and if any part of the trade is not agreed upon, the trade falls through.

These trades do not have any impact on the price and volume trading in the market while they are reported separately on a daily basis on the PSX website in order to inform the investors regarding these transactions being carried out on the side.

The biggest risk of such a trade is the fact that there is counterparty risk. This can be a scenario where the buyer will not buy the shares or the seller would not provide the shares when the trade is supposed to be carried out.

In normal operations, there is a clearinghouse in the middle of every transaction carried out in the stock exchange. When a seller sells the shares and a buyer buys the shares, the clearing house in Pakistan; National Clearing Company of Pakistan Limited (NCCPL), takes the funds from the buyer and transfers it to the

seller and takes the shares from the seller and transfers it to the buyer. This is how a normal transaction is carried out.

Typically, if the seller does not hold his side of the trade and does not provide the shares that they have committed to sell, the NCCPL steps in, in conjunction with the PSX, and forces the seller to procure the shares from the Squareup market to fulfil the demand of the buyer. This procurement of the shares comes at a higher price as the squareup market mostly trades at a premium from the regular market.The seller did not honour the deal in the first place and so he has to pay a penalty.

On the other hand, if a buyer does not have the funds in their account and they renege on the deal, they are declared as defaulters in the stock market and they are not allowed to trade until this commitment is fulfilled. The trading terminals of the broker are suspended and the PSX and NCCPL make sure this non-compliance is corrected.

There is no such protection in the NDM market. There is an open risk that either the buyer or the seller can back away from a trade and not stay true to the deal that they have negotiated in the first place. When a participant is entering the market, both parties understand the risk that either party can back away from the commitment they have made and any consequences that have to be borne will impact both sides of the transaction.

In order to understand the actual utility of the market, let us consider a scenario.

In this scenario, we can assume there is an investor who is looking to sell a large amount of shares in the market. The seller knows that once he goes into the market and starts to unload a large position, the market will not be able to absorb the volume and will end up decreasing the price of the shares. As the sale quantity is released into the market, there is pressure on the price to fall precipitously and as this happens, the people who possess the same company’s shares see the value of their portfolio fall as well. This introduces more selling of the same shares in the market, causing the price of the share to fall further until a lower lock is engaged and trading is stopped.

In such a case, an interested party can step in and carry out a negotiation with the seller to give all of his holding to the buyer without going to the market. An investor who holds the share of that company would not want for their share to tumble in the exchange and commit to the seller that they will buy the whole quantity of shares in one go. The quantity and price is negotiated between the two parties and the trade is carried out. This is beneficial for the seller as they are able to

sell the whole of their position without much friction and loss of value. The buyer is able to benefit as they will be able to buy the whole lot of shares in one go while the price of the shares remains unimpacted in the market.

Similarly, the other side can be considered where the buyer wants to buy a huge quantity of shares from someone they know is willing to sell the shares. He does not want to place a huge buying order in the market which will build a rally in the market and not allow him to buy a large amount of shares at a lower price. He can shop around the market and find a seller who is willing to sell. Once he locates such a seller, he can buy these shares on the side while not disturbing the actual market.

In terms of the monitoring being carried out by the SECP, it has stated that the regulator is actively analysing trading data on a regular basis and making sure that “as a part of its mandate to safeguard interest of minority shareholders, [is monitoring] the trading activity in the shares of the listed companies.”

In terms of the market itself, the SECP clearly states that NDM is set up as a dedicated market for negotiated deals and that parties can enter flexible terms in regards to price, quantity and settlement date which is not provided in the ready or regular market.

A pre-arranged transaction being executed in the ready market is considered an offence as it distorts the supply and demand. Still, SECP states that “SECP may question the legitimacy of an NDM transaction if it is found to be a part of a manipulative scheme.”

Even though such a market is available to both the buyers and sellers, there can be cases made for these transactions being carried out from the scope of seller, buyer and a case against such trades being carried out. Take the example of Unity Foods from last year.

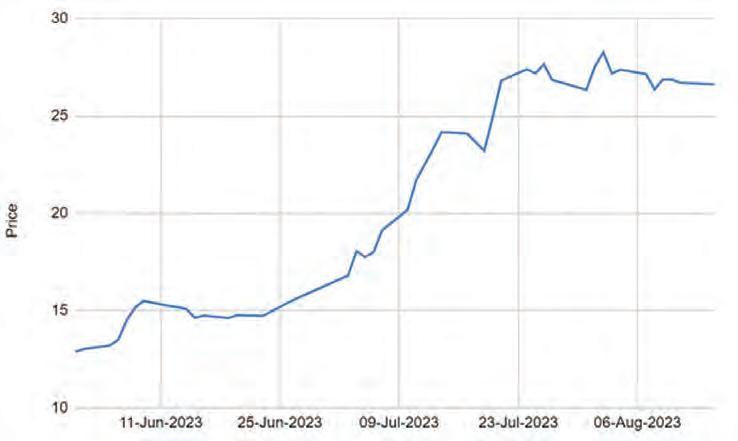

On 1st August 2023, the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) was notified that Amir Shehzad, Executive Director at Unity Foods had bought 4 million shares of the company. In terms of the information that was given, it was stated that this trade had been carried out in the NDM market. This trade was carried out at Rs. 20.32 on the 26th of July 2023 through AKD Securities Limited (TREC holder code 019).

The shares of Unity Foods Limited had been seeing a rally, in conjunction with the rest of the stock exchange, where the shares stood at Rs. 15.63 on the 27th of June and went to around Rs. 27.65 by 26th July 2023. On the day that the purchase was carried out, the share had moved between a band of Rs. 27.65 and hit a low of Rs. 27. The trade that was carried out was perfectly legal and any buyer who wants to buy shares has every right to buy shares at whatever price they see fit.

You may be wondering why the seller took such a hit when he could have easily walked away from the deal when the price had shot up to Rs 27?

Profit was unable to get a comment from the buyer, the executive director at Unity Foods or anyone from the company. The seller is unknown. But some safe assumptions can be made to answer this and in the process explain how some, not all, of these transactions are executed.

In case it is assumed that the seller was the originator of the transaction, as earlier noted, the high amount of sale taking place would have put an undue pressure on the price if this quantity was sold in the market. In many cases, the seller also has such a huge quantity and he knows that trying to sell a huge quantity might not be feasible, as there is a lack of liquidity in the market, or will impact the price for him as well.

In such a case, the seller looks

around and communicates with other parties who might be interested in buying such a huge quantity. The price differential is justified in those cases as the seller feels that due to the size of the quantity, making a deal at a lower price is attractive to a buyer and will allow him to liquidate his own position. In those cases, the price differential can be explained and justified.

In these cases, the buyer also has an incentive to not see such a large quantity to be transacted in the market as any fall in the price of the share will impact on their own shareholding and net worth as well. After all, as a director in the company whose shares are up for sale, it is his responsibility to look out for the company’s interest. He would have therefore urged the seller to do this deal in the NDM market.

On the other hand, assuming the buyer was the originator of the deal, it can be seen that they would have used the NDM market for their benefit as well. The benefit the buyer gains is that rather

than going to the market and placing such a large order, he contacted other shareholders and sealed the deal at a rate that was advantageous to them. The buyer could have gone to the market and his buying could have led to a rally in the market based on his buying alone.

Another argument that can be made is that the deal was brokered between the buyer and the seller months in advance. It can be assumed that the two parties sat together months ago and decided to carry out the transaction at Rs. 20. At that time, the market price was lower and the buyer was giving a better price to the seller. Even if the price was the same, the deal was brokered and a commitment was made.

The two parties had reached a deal and while they were in the process of putting in the formalities and resources in place, the share price increased which was not in control of the parties themselves. Once the things were in place, the market had increased beyond the agreed upon price. The two parties stayed true to their word and executed the trade at the price they had agreed upon earlier.

The other side of the coin leaves certain questions still to be asked. When such a trade is carried out at a price at such a deep discount, the market gets the wrong perception. Even if everything is above board and the transaction is carried out with all the formalities being satisfied, there are still questions that are raised.

If the director of the company is willing to buy the shares at such a low price, what signal is he sending to the market? On the day he was buying shares at Rs. 20.32, a normal investor was buying the same shares for Rs. 27. The director is saying to the market that he thinks the actual value of the shares is much lower than the one prevailing in the market.

The director can also send a better signal to the market by actually buying a large quantity of these shares in the market and create a rally in the market itself by placing such a huge order in the market. Such a large buy and that too from the director will send a positive signal to the market and the share would have reacted positively to such a buying order being placed in the regular market.

Another example of the NDM market being used for such transactions is also from last year. On the 3rd of August, NDM market showed around 4.455 million shares were traded at a price of Rs. 540 which comes to a value of Rs. 2.4 billion. All of the selling was carried out by Topline Securities Limited (TREC holder Code: 166) while the buying was carried out between Topline itself, Standard Capital Securities (Private) Limited (TREC holder code 112), Pearl Securities Limited (TREC holder code 169), Vector Securities (TREC holder code 025) and Darson Securities

(TREC holder code 090).

This was being carried out when the actual price of the share closed at Rs. 675 for the day and the trades were carried out at a discount of around 20%. Again it is pertinent to state here that this is a legal mechanism and the rationale for the price being 20% lower than the market price can be legitimate and rational based on the reasoning of the buyer and seller. However, as the process of this price discovery is not transparent, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth in terms of the fairness of the market.

Just like trades have been carried out at prices below the market prevailing prices, examples can also be found on the other side where the agreed upon prices are higher than the prices of the market. An example is TPL Properties (TPLP) being carried out by Alfalah Securities CLSA Limited. The NDM data for 1st of August 2023 shows that Alfalah Securities CLSA (TREC holder code 120) was able to carry out a client to client trade of 1.7 million shares at a rate of Rs. 17 per share. The market price for TPLP closing on that day was Rs. 13.49. This means that the trade was carried out at a premium of 26 percent. As no rationale is provided for the trade, there is a sense of sellers being hard done by who would have sold the shares in the market for Rs. 13.49 when they could have sold it for Rs. 17 if the buyer had come to the regular market rather than use the NDM market.

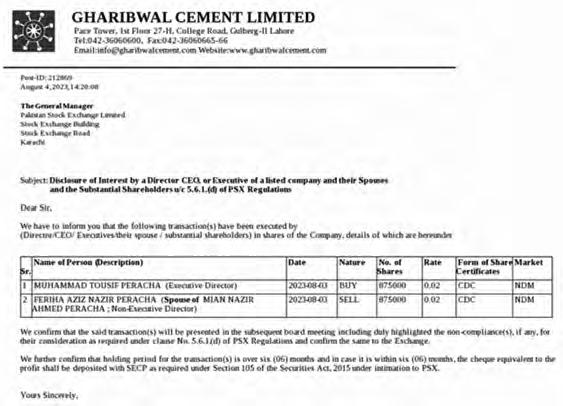

The last example that can be used in terms of the NDM market being muddled in terms of price discovery can be seen as the recent trade being disclosed by PSX in both the NDM market and a disclosure being made by one of the directors. The shares of Gharibwal Cement Limited (GWLC) were trading at Rs. 18.58 while one of the spouses of the directors was able to sell her shares for Rs. 0.02 to another director. The fact that the director was able to get the shares for pennies while the investors are buying the same shares

The NDM market is a legal way for investors to negotiate and carry out trading in a market which is not part of the main market. There is a utility and value that can be attached with this market as it allows buyers and sellers to negotiate a trade and determine the price and volume of shares to be traded which is not based on the market discovery that is being adhered to in the market. The

buyer and seller can have their own justification and rationale of such trades being carried out.

Still, having said that, there is a lack of transparency that exists in such a market which creates a sense of unfairness and gives a perception that the NDM and its process for price discovery is hidden from the investors in the regular market.

Investors who have to buy at a rate higher than one at which participants of NDM market are able to buy or sellers selling at a price lower will feel that they do not have a chance to sell or buy at a price at which they would prefer to do so.

When the NDM market is allowed to operate in such a manner, the

feeling of being hard done by will persist. A move towards better transparency and justification for the price discovery being where it is being seen in the NDM market will go a long way in developing a sense of equity in the stock exchange. n

The race to become the dominant provider of mobile broadband internet has been intense from the start, but the initial leader has given up its crown to Jazz

By Hamza Aurangzeb

Today mobile broadband has become a necessity for majority of the people in Pakistan, an essential service whose absence would make our lives an arduous task, making it difficult for us to survive. We have become accustomed to mobile broadband to such an extent that it plays a pivotal role in every sphere of our lives, be it booking a cab for travelling, ordering food from our favorite restaurants, learning new skills via online courses, or moving funds through online banking channels.

It is a technology which has enabled Pakistanis to transcend geographical boundaries and traditional socioeconomic status to realize their true economic potential. The extensive utilization of mobile broadband technology has

transformed into a giant industry of Rs372 billion, where each mobile network operator is arm wrestling one another to persuade you to utilize their network through a variety of strategies.

While there are four mobile network operators in Pakistan, each with its own strengths and peculiarities but who rules the mobile broadband market? Profit presents this story that will take you on an explorative journey of the mobile broadband industry in Pakistan.

The internet was introduced in Pakistan in the year 1993 as a UNDP-funded project named the Sustainable Development Networking Program (SDNPK), after a couple of years

in 1995, Digicom, initiated an online dial-up service in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, which offered a speed of merely 66 kbps.

Afterwards, the state-owned PTCL launched its own dial-up services during the same year. The usage of the internet during the time was extremely limited and restricted to urban areas, as the service providers offered slow internet speeds at high costs. The internet was mostly utilized in educational institutions, government departments, and businesses.

Pakistan’s telecom sector liberalized at the start of the new millennium, which led to intense competition and lower prices. In 2001, PTCL brought its Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) broadband services to the market, which provided significantly faster speeds in comparison to dial-ups. It was also the

time when private internet service providers started jumping onto the bandwagon, which further enhanced the internet’s accessibility.

The extensive availability of the internet increased the popularity of online content, email services, and early websites. Email became a popular mode of communication, while chat platforms like MSN Messenger, ICQ, and Yahoo Messenger caught the fancy of the youth. Moreover, cyber cafes mushroomed across major cities. They offered hourly internet access to customers who could nt afford to install an internet connection at their homes.

Hence, broadband services started expanding at an unprecedented rate during the mid-2000s due to increased consumption of online content, where PTCL emerged as the market leader through its DSL offerings and wireless broadband providers such as Wateen Telecom and Wi-Tribe entered the market.

However, 2014, marked the beginning of the most revolutionary era in the history of Pakistan’s internet as the Government of Pakistan decided to auction 3G and 4G spectrums to telecom companies in Pakistan. This endeavor introduced high-speed mobile broadband in the country, which not only provided impetus to broadband penetration, particularly in rural and remote areas but also enabled the telecom sector to reach the next evolutionary stage of technological advancement. This was the time when majority of the population owned feature phones and smartphone penetration in the country was extremely low, close to 10% or less. They barely had access to a stable and high-speed mobile broadband. Thus, the introduction of even 3G technology, which was introduced more than a decade ago in Japan was a notable transition for Pakistani customers.

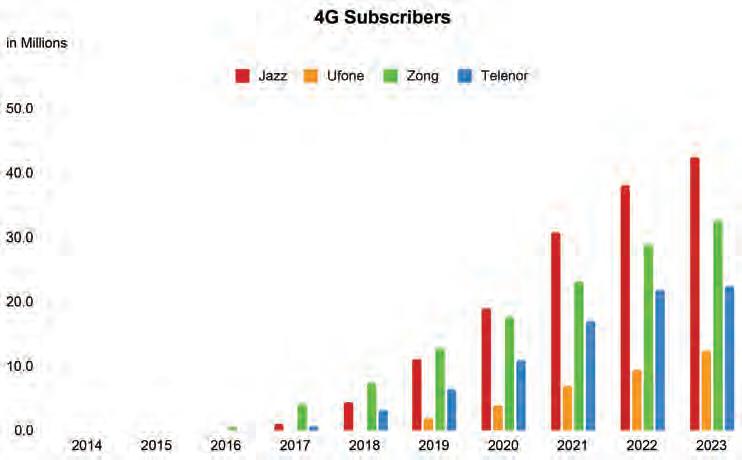

In 2014, when the government auctioned the 3G and 4G spectrums, four 3G and two 4G spectrums were offered, four major operators, namely Zong, Mobilink, Telenor, and Ufone bought 3G spectrums. Each of them bought the 3G spectrum at barely above the base price of $295 million except Zong, which paid $307 million. Every operator secured a 3G spectrum except Warid, which did not participate in the auction due to financial distress. However, Zong went one step ahead and bought the 4G spectrum as well to become the only telecom company to offer 4G services in the country.

Zong was the latest entrant in the Pakistani market, which commenced operations in 2008, after its acquisition of Paktel in 2007. The company initially controlled a negligible market share of 2% but it managed to become the third largest operator in the market by number of subscribers by 2014 through its strategy of offering services at a lower rate than the industry average.

However, the core focus of the company remained data, as it believed it to be the future of the telecom business because revenues for telecom companies through traditional streams like voice and SMS faced intense competition and yielded modest results. Hence, the company decided to go all in on data by buying a 4G spectrum for a sum of $210 million. Thus, the company spent $517 million in total on both licenses.

Soon after the conclusion of the auction, Warid revealed its plans to launch 3G

and 4G services without actually buying the spectrum, as when it entered the market in 2004, it had acquired a “technology-neutral” license from the Government of Pakistan, which allowed it to offer 3G and 4G services using its existing spectrum.

Therefore, we had two operators offering 4G services and three operators providing 3G services after the auction. As soon as Zong launched its 4G services, it took the market by storm, it attracted 4G subscribers by leaps and bounds, Zong had 105,000 4G subscribers in 2015, its 4G subscribers increased to 7.4 million by the end of 2018, where it grew at an astonishing rate of 312.2% per annum. During the first two years, it grew so rapidly that it catered to more than 70% of the 4G subscribers in Pakistan.

Zong displayed such robust growth that all the telecom operators were taken aback. Hence, as soon as the government auctioned 4G spectrums once again in 2016, both Mobilink and Telenor bought the 4G spectrum for themselves in order to avoid further damage from Zong’s ruthless march. Ufone remained the only company, which did not transition to the 4G technology and that cost the company big time as of the Rs8.9 billion of revenue that Zong took from its competitors in 2015, Rs6 billion came from the books of Ufone.

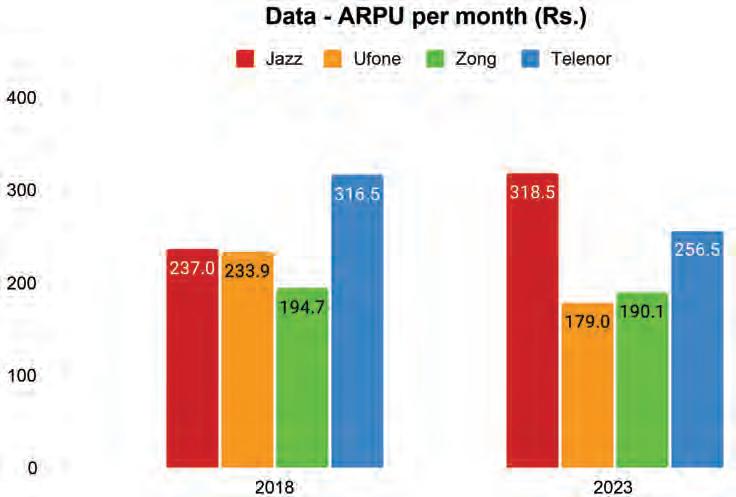

Now, Warid had launched its 4G services and was generating the highest Data - ARPU per month of Rs504 in the industry, however, it lacked the financial muscle to fully develop its 4G infrastructure. Hence, Mobilink acquried Warid in November 2015 and the new merged company was rebranded to Jazz in January 2017.

The merger of Mobilink and Warid along with the acquisition of the 4G spectrum played a crucial role in enabling the company to create space in the segment of 4G services, where it controlled around 29.0% of the 4G subscribers by 2018. The urban-based 4G subscriber base of Warid along with its great network quality boosted the 4G segment of Jazz, but Telenor was not far behind as it had 20.6% of the 4G subscribers as well.

Aslam Hayat, the former Chief Strategy Officer at Telenor, expressed his thoughts on the merger by stating that “Jazz, the leader in the mobile broadband market, received an advantage by integrating with Warid, which had a higher ARPU customers and a better network quality. Moreover, Warid’s customer base was concentrated around urban centres, which created a club effect and boosted Jazz’s market share significantly.”

By 2018, although Zong was leading the 4G segment by controlling almost half of the 4G subscribers and data usage, it was still

(Note: The market shares of 2018 have been calculated with the help of Data - ARPU per month of CMOs provided by the PTA annual report 2020, p. 62).

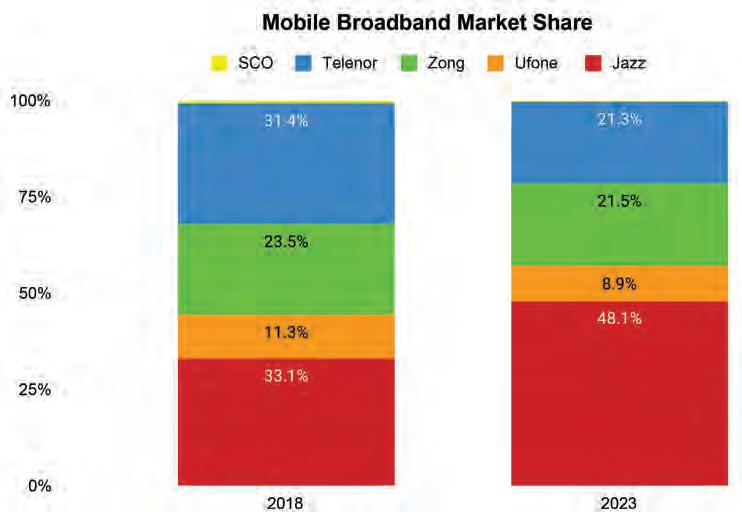

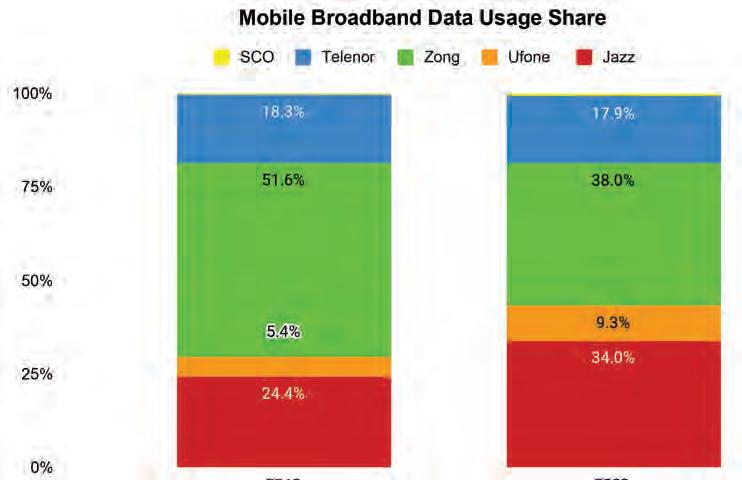

behind telecom operators like Jazz and Telenor in the overall mobile broadband market, which had larger market shares of 33.1% and 31.4%, respectively. Zong had a market share of 23.5%, whereas Ufone found itself in the last place with a market share of only 11.3%.

The mobile broadband market in Pakistan developed at a swift pace from 2018 to 2023, where the mobile broadband penetration increased from 27.0% to 52.3%, and 65% of mobile subscribers started using broadband services, whereas the number stood at only 37% in 2018.

Moreover, 90% of mobile broadband subscribers were using 4G services by 2023, which conspicuously reflects technological evolution in the mobile broadband space. This became possible due to the augmentation of BTS sites and the widespread availability of 4G-enabled data handsets. Thus, the mobile broadband market evolved with the evolving technology.

Jazz continued to expand its 4G subscriber base owing to its extensive investment in its 4G infrastructure post the merger, which allowed the company to provide greater coverage of 4G services and high download speeds. This could be confirmed by the Quality of Service surveys conducted by PTA in the fourth quarter of FY23. Moreover, 90% of Jazz users can access its 4G services across both

urban and rural areas as per Opensignal.

This great 4G network along with the introduction of a diverse range of digital services maximized the customer’s attention span on its network and increased its share of 4G subscribers to 38.0% by 2023. It overtook Zong’s share of 4G subscribers post 2019 and established itself as the emperor of the mobile broadband market. As of 2023, Jazz generated a Data - ARPU per month of Rs318.5 and controlled 48.1% of the mobile broadband market overall.

On the contrary, we have Zong whose 4G subscribers have increased substantially as well since 2018 but not at the same speed

as Jazz. The primary reason being its less impressive coverage of 4G services, specifically in rural areas, as its coverage in urban areas is exceptional. Although Zong lags behind in terms of coverage of 4G services, it offers higher latency than Jazz.

Zong has a data-first strategy, it offers the cheapest broadband rates in the country around 18.3 per GB. Its cheap data packages and high latency make it ideal for gaming, video conferencing and other real-time interactive applications which is why the network has the highest data usage of 4,163 PB (4.365 billion GB). As of 2023, Zong has a share of 38% in data usage in comparison to Jazz’s share of 34.0% but that has also not proven enough for the company to speed past Jazz as the network now possesses around 29% of the 4G subscribers, while Jazz holds around 38.0%.

It lags behind Jazz in terms of subscribers for both voice and SMS and broadband services, as although customers mostly utilize broadband services, they also require voice and SMS services. They prefer to own a sim, which could provide them the best of both worlds. Hence, Zong was only able to generate a Data - ARPU per month of Rs190.1 in 2023 despite its data-first strategy and held a market share of only 21.5%.

Mr. Hayat in an exclusive interview with Profit elaborated, “When Zong launched its 4G services earlier than everyone else, it had a first movers advantage which allowed it to expand rapidly, however, as 4G enabled handsets became widely available, and Jazz and Telenor bought more 4G spectrum, they started catching up. Furthermore, Zong’s strategic focus was on data and dongles, not voice and SMS. This data centric strategy has also adversely affected the company’s market share

as subscribers opt for networks that provide full telecommunication service, rather than just high-speed internet.”

Laggards in the 4G race, can they unite to accelerate?

Telenor had a decent market share in the mobile broadband industry initially as it immediately became the market leader in the 3G segment

when it was launched. It had 31.3% of 3G subscribers in 2015. It was neck to neck with Jazz in terms of mobile broadband market share until as late as 2018 as it witnessed a reasonable beginning in the 4G segment as well.

However, as time progressed, competition intensified, specifically after the merger of Mobilink and Warid. Hence, its Data APRU per month started declining, it went from Rs316.5 in 2018 to Rs256.5 in 2023, while its share of 4G subscribers and data usage stagnated. Its strategy of target-

ing low-income rural population in order to build a vast customer base also played a fundamental role in its decline. It acquired the 850 MHz spectrum at a mammoth cost of $395 million for its 4G services. However, the move didn’t yield the desired results as that frequency was only supported by relatively expensive smartphones, which were unaffordable for majority of its customer base. Hence, its market share declined to 21.3% in 2023.

Now coming towards Ufone, it was the only company which did not offer 4G services until 2019, when it launched 4G services with the government’s approval but without actually purchasing the 4G spectrum. Ufone was the only company which had more 3G subscribers than 4G subscribers until 2021. However, the company has upgraded its BTS sites over the past couple of years, which has enhanced its 4G tower base from 4,077 to 10,118, while its share of 4G subscribers has increased to 11.0%. Nevertheless, it still has small shares in terms of data usage and revenue, around 9.3% and 8.9%, respectively.

Having said that, one should not forget that PTCL bought 100% stake in Telenor in 2023, which will likely merge both Ufone and Telenor in the coming months, however, the completion of the acquisition is subject to regulatory approvals and customary closing conditions.

This merger will provide a multitude of synergies to Ufone, foremost being consolidating its position in the mobile broadband market and enhancing its coverage in both rural and urban areas as Telenor’s primary customer base resides in rural areas, while Ufone’s customer base is centred around urban areas.

The combined data usage of both customer bases will cross the mark of 2,951PB (3.1 billion GB), which represents around 27.2% of total mobile data usage. Moreover, it will improve the company’s Data - ARPU per month to Rs227.3, leading to a market share of 30.2%. This merger will certainly transform Ufone into a major player in the market, which would not only be able to influence the market but challenge the status quo as well.

However, Jazz remains the undisputed leader of the mobile broadband market today. It checks all the boxes and is the preferred choice for majority of the 4G subscribers, corroborated by its largest market share.

Nevertheless, one element where Zong leads the market is data usage, as it offers broadband at dirt-cheap rates with high latency, making it popular for real-time interactive applications. Notwithstanding, one can’t also underestimate Ufone as it has shown promise over the past couple of years and could mutate into a behemoth dominating the market. n

The auto assembler sees growth in sales leading to better profitability. But even as the demand rises, the auto assembler is placing a great emphasis on cutting costs

By Zain Naeem

It seems like the slump in the auto sector is coming around.

To an extent.

The latest results from Indus Motors show that the downward trend in its sales has finally turned for the better and the company has shown good performance for the first quarter of FY 2025. The car company saw growth in both its sedan classes and its Sports Utility Vehicle (SUVs) Segment in the last two years. Sedan sales increased by 40% from 3,236 at the end of September 2023 to 4,554 at September end 2024 while SUVs saw a growth in sales of 26% from 1,275 to 1,606 for the same period. This has led to the company seeing a growth in its profits as well. The news comes on the back of the recent revival of auto lending which has been seeing a downward trend for 27 consecutive months due to record high interest rates. As interest rates have declined by almost 450 basis points from 22%, the auto lending sector saw revived demand.

The results of the company show that the company has increased its revenues by 27.3% from Rs 32 billion last year for the same quarter to Rs 41.6 billion this year. The company saw record high revenues of Rs 275 billion on the back of 75,611 units that it sold in 2022. Last year the company recorded its worst year in terms of sales as it was only able to sell 21,063. The recent results point towards the fact that the company will see better end-of-year figures as well as better results by June of 2025.

The company was able to earn better gross profits which increased by almost 70% from Rs 3.3 billion to Rs 5.6 billion. This was down to better cost management as the company was able to increase revenues by 27% while its costs only increased by 22.6% for the same period. The company did see an increase in its selling and distribution expenses which almost doubled from Rs 38 crores to Rs 66 crores this quarter while administrative costs were similar. The company also saw an increase in other operating expenses which meant operating profits increased from Rs 2.2 billion to Rs 3.9 billion.

Indus Motors has continually looked to

address its finance costs which have increased in recent years. It has done so by investing in fixed-income assets which have seen a growing investment trend in recent years. Due to excess cash and liquidity at hand, the company has looked to invest these funds into income-generating assets which have supplemented much of the income being generated by the company. In 2009, the company saw Rs 72 crores in other income which have steadily grown to Rs 13 billion by 2024. The company made a decision in 2022 that it was looking to increase localization and set up a hybrid plant in the country. In order to make this possible, the company chose to invest in its fixed assets while it used much of its excess liquidity to pay off its current liabilities. The company saw its liabilities go from Rs 160 billion to Rs 62 billion in 2023. Simultaneously, there was also a decision made to invest excess funds into income-generating assets which increased other income 13 times from where they stood at in 2009. Due to other income, the company saw net profits of Rs 5 billion this quarter where they stood at Rs 3.2 billion last year for the same period. Other income generated from non operation activities stood at Rs 4.5 billion this quarter which were Rs 2.8 billion last year. If these two amounts are taken away, the company would have seen Rs 63 crores of profit this quarter and Rs 39 crores in the last quarter.

To put the performance of the company in context, the company has shown that it has earned Rs 64.77 per share this quarter in terms of its profits which was Rs 40.91 last quarter. If the other income element is taken away, the company would lose Rs 56.7 per share for this quarter leaving behind Rs 8.07 per share in terms of operations that the company controls itself. The same can be done for last year where the company would lose Rs 35.89 per share leaving behind only Rs 5 per share in terms of operational profits of the company.

The recent results show that the company is seeing an increase in its sales which is a positive sign for the company and the industry. The increase in net revenue of the company is down to the efforts of the management itself and the cost savings are also leading to better gross profits. However, relying on the growth in

earnings per share can be a little misleading as it hides the fact that the company is earning most of its profits from means and sources outside the company itself. The company has made some astute investments in the past which are reaping profits and returns for the company this year as well. There are signs of recovery and this recovery and revival needs to be built upon before the management at Indus can be credited.

There are additional aspects that also need to be considered which have taken place in recent days which put another asterisk next to the performance of the company. On the day the results were announced, the company also announced that they would be carrying out a plant shutdown. This is due to low demand that the company has been seeing in recent years. In 2024, the company only produced 19,599 units while it had a capacity to produce 66,000 units on an annual basis. Due to low demand, the company finds it economically feasible to shut down in order to limit costs rather than increase the losses it is making. The shutdowns are also a legacy of the import restriction that was placed on the industry. Most of the car manufacturers in the country are assemblers meaning they import the parts and then assemble them locally. The import ban meant that parts could not be imported which meant it was better to shut down production as the parts were not available. In the recent disclosure as well, the company announced to the exchange that it was seeing a shortage of parts due to which they were not able to meet production requirements causing them to shut down for 3 days.

It can be said that there are signs that the auto sector is seeing signs of recovery with auto sales increasing in recent years. Any definitive statement in regards to Indus Motors will have to wait for at least the next few quarters. In 2024, the company was able to sustain profits by increasing their profit margins and showing better returns. The first quarter has shown that demand is picking up as well. However, any performance improvement in the company has to take into account the fact that most of its profits are from other sources. The company needs to get back to 2022 levels where most of its profits were being generated by its own operations. n

Elphinstone,

the startup that lets Pakistanis invest in US companies, has acquired Pakistani digital asset management company

Elphinstone, the investment advisory startup founded in 2020, has made an acquisition. It has successfully acquired Pakistani wealth management startup called Trikl for an undisclosed seven-figure sum

By Taimoor Hassan

Elphinstone, the investment advisory startup founded in 2020, has made an acquisition. It has successfully acquired Pakistani wealth management startup called Trikl for an undisclosed seven-figure sum.

The acquisition marks a watershed moment for a startup that has seen highs and lows for the past four years. It was founded as a one of a kind investment advisory startup that is banking that one day Pakistanis would know that they can invest in countries like the US and earn a lucrative return.

Elphinstone targets individuals with a dollar income, such as freelancers, or savings in Pakistan. Most people do not realise government regulations allow you to invest $25,000 per person per year abroad, legally. Elphinstone provides platform and advisory services for people to do this.

The vision of creating a business that facilitates Pakistanis’ investments abroad, especially in the US stock market, has been a long-standing ambition for Farooq Tirmizi since 2009. Mr Tirmizi has an impressive resume, and is a seasoned investment professional with a background working at promi-

nent investment banks in the US. He has also worked extensively as a journalist in Pakistan, first serving as the chief financial correspondent at Express Tribune. Mr Tirmizi has also played a significant role in shaping this publication, having served as its managing editor for four years, Tirmizi has been pivotal in getting this magazine its traction and success until he left it in 2021 to pursue his passion project Elphinstone.

“I am not a startup founder because I want to be a startup founder,” Farooq Tirmizi says in an interview with Profit. “I am a startup founder because this thing should exist. Nobody else was building it so I built it.”

Things have been difficult for Elphinstone from the get-go, having faced challenges after challenges. But Elphinstone has been able to survive. And not only has it survived, it has recently acquired another wealth management startup Trikl for an undisclosed amount.

Elphinstone has carved out a unique niche in the fintech landscape by enabling Pakistani investors to access the US stock market. The company is registered with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and has already established a partnership with a brokerage