08 Fauji Fertilizer wants to be the only Fauji Fertilizer company. How will the chips fall going forward?

12 Education in Pakistan: Not good, but getting better

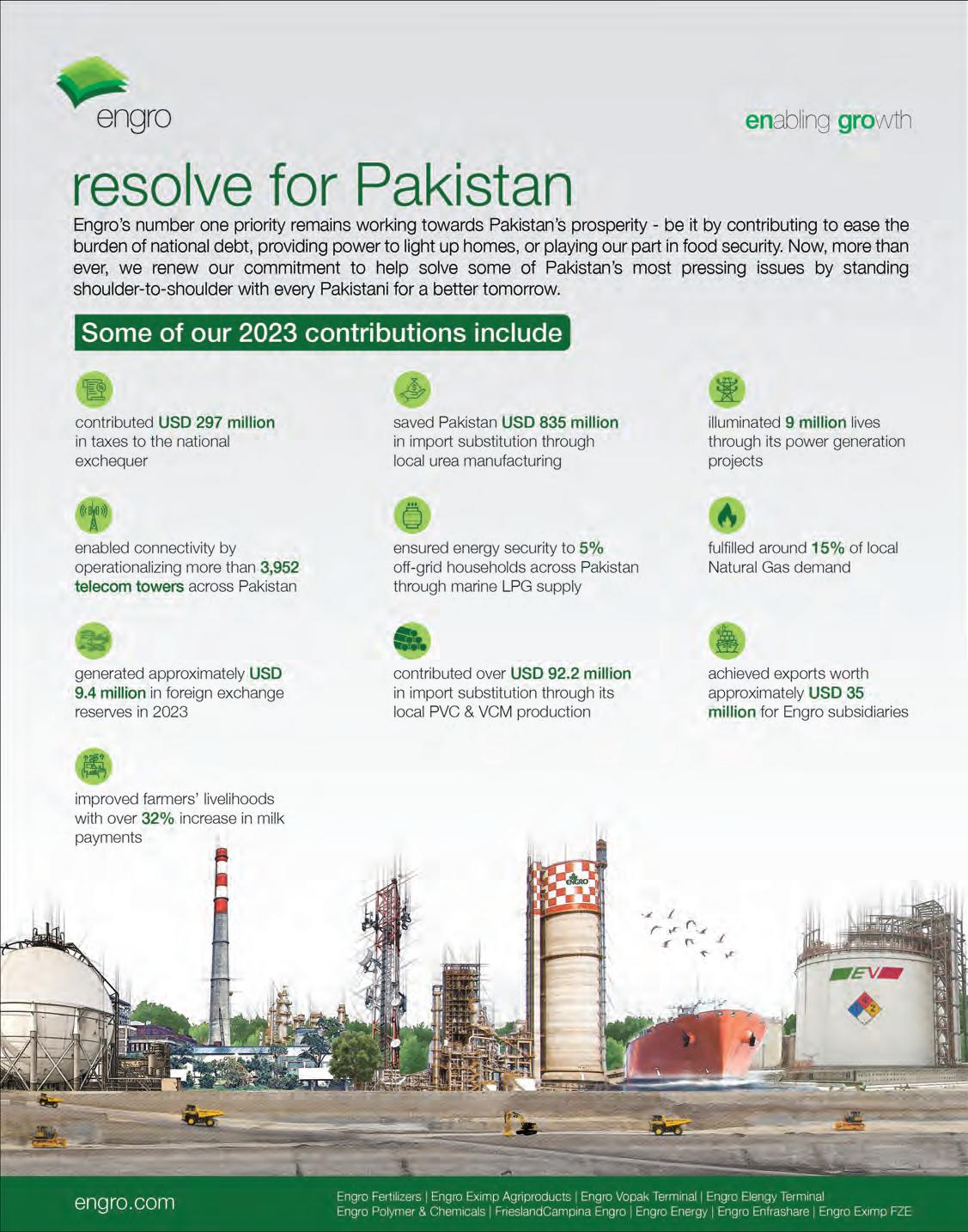

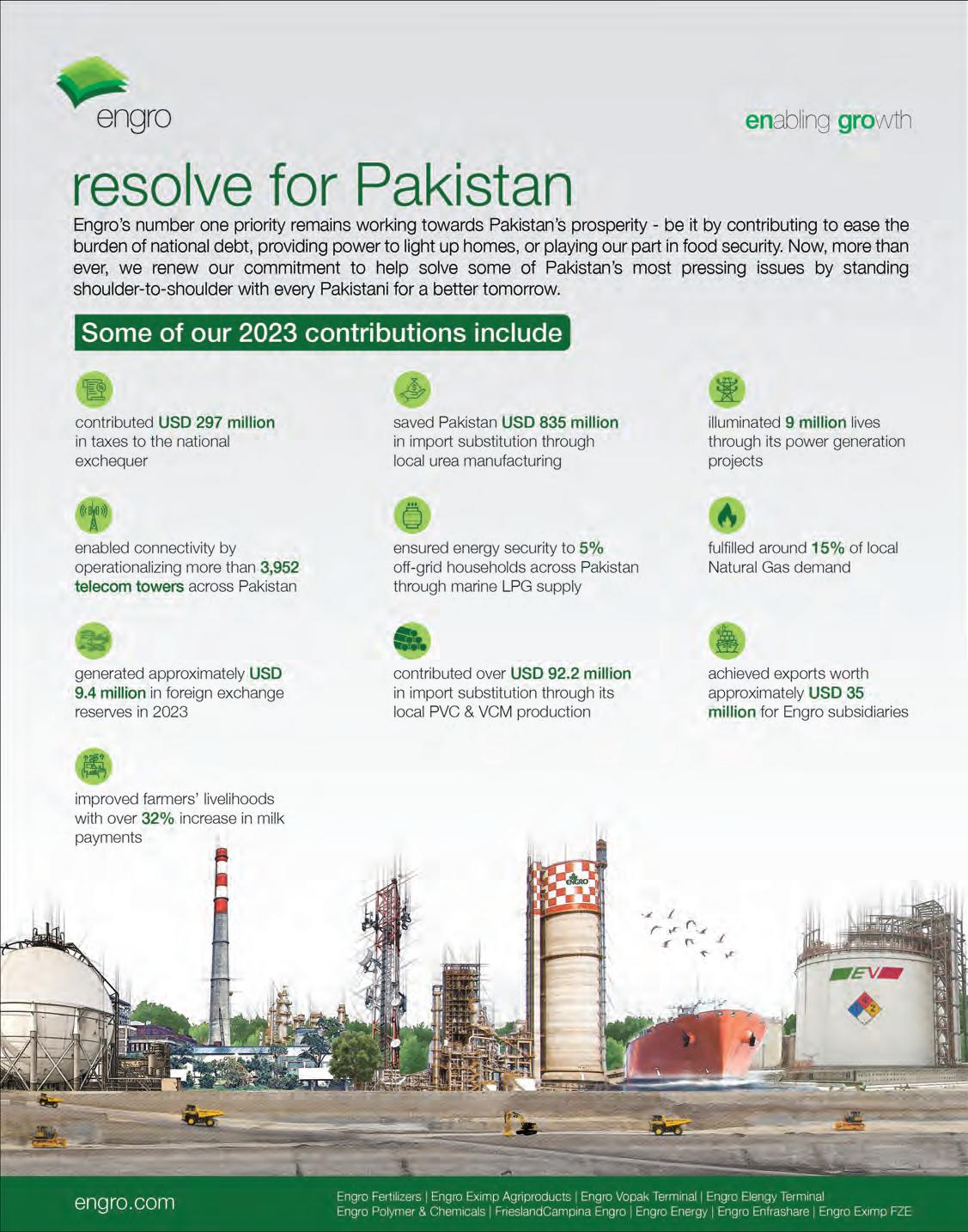

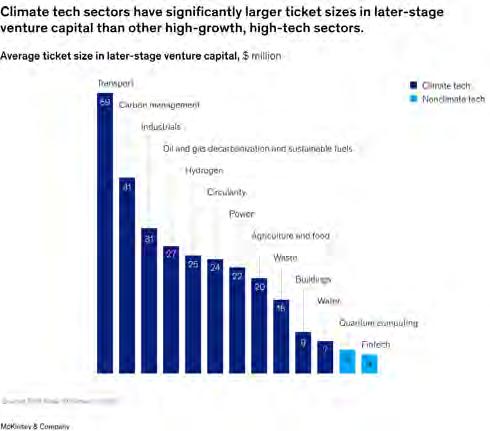

17 Pakistan’s cleantech conundrum: Scaling the tech in an economy that is a wreck

19 Can the government finally seal the deal on the privatisation of FWBL?

24 Retailers cry betrayal as FBR’s Tajir “Dost” scheme takes a new turn

28 A few select startups made the funding needle budge slightly. Are there any lessons to be learned?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Fauji Fertilizer company is looking to merge Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim into the main company. What will be the impact?

By Zain Naeem

On the face of it, it might seem a little strange. Fauji Fertilizer Company (FFC) is looking to take over Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim (FFBL). The former is a grand old

company set up in 1978 that has become one of the leading fertiliser manufacturers in the country. It is owned by the Fauji Foundation, which is as old (and by some measures older) than Pakistan itself. The latter is also a fertiliser company owned by the Fauji Foundation founded in 1993. It is an independent entity owned by the Fauji Foundation and Fauji Fertilizer.

Fauji Fertiliser actually played the leading role in setting up the Bin Qasim plant. The plant was planned and executed to cater to increasing demand. Fauji Fertilizer started with a production capacity of 570,000 metric tons which has steadily increased to 3.4 million metric tons where it stands now. Currently, the company holds around 49.88% of Bin Qasim and is the major shareholder.

The point of not acquiring it entirely was to keep it a separate entity that can be listed individually on the stock exchange where investors can buy a stake in the company and its profits which are exclusive to the profitability of the parent company. The advantage to Fauji is that it is able to generate funds for the plant by issuing equity shares in the company.

That original decision seems to have changed. There is a move to merge Bin Qasim completely into the parent company. What would Fauji Fertilizer gain from this move and what will the investors in Bin Qasim get in exchange for it? Profit tries to parse through the intricacies of this deal

The history of Fauji Fertilizer starts in 1978 when the company was incorporated as a joint venture between Fauji Foundation and Haldor Topsoe of Denmark. The culmination of this venture was the setting up of the first plant in Sadiqabad in 1982. The annual capacity of the plant was around 570,000 metric tons initially which was increased to 695,000 metric tons. The primary goal of the company was to produce urea to be used by the farmers of the country.

As the company saw expanding demand, it set up its second plant and commissioned the Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim plant in 1993 with the cooperation of international and national institutions. In 2000, the company also took over Pak Saudi Fertilizers Limited situated in Mathelo after it was privatised by the Government of Pakistan. The company is currently involved in the production of various types of fertiliser to cater to the local market. The company is considered the largest fertiliser marketing company in the country and boasts production of 3.4 million metric tons on an annual basis including production carried out by Bin Qasim plant.

Bin Qasim by itself has also been a successful company on its own. The company started with an initial capacity of 551,000 metric tons of urea and 445,500 metric tons of DAP. Recent results show that the company crossed the Rs 200 billion mark in terms of revenues and earned Rs 33 billion in terms of gross profit alone in 2023. The company has 56% of the market share in terms of DAP sales.

In its board meeting held on 19th of July, Fauji Fertilizer announced that the board had granted an approval to evaluate the amalgamation of Bin Qasim

into Fauji Fertilizer based on a scheme of arrangement. The actual breakdown and the numbers were not shared as the board had only approved the idea of the merger. At this point, the company is considering the due diligence to be carried out in order to formalise this deal. The rationale behind this move is to allow for synergies which will add value to the combined company once the amalgamation is carried out. It can be expected that the deal will unlock additional value for Fauji Fertilizer which will be accrued to the shareholders of the company.

Both these companies are part of the Fauji Foundation group and Fauji Fertilizer already owns 49.88% of Bin Qasim due to its initial investment in the project back in 1993.

The board of Bin Qasim has also agreed to the decision and has stated that they are looking forward to the scheme of arrangement that will be designed in order to finalise this proposal. Based on the performance of the company, it can be expected that the scheme of arrangement that is announced is beneficial to the investors who currently hold the shares of Bin Qasim. An amalgamation would mean that Fauji Fertilizer would own 100% of Bin Qasim and investors who currently hold the shares of Bin Qasim will get an equivalent shareholding in Fauji Fertilizer. But what can be considered equivalent?

Based on a simple back of the napkin calculation, it can be seen that the market price of Fauji Fertilizer is around Rs 167 per share while for Bin Qasim it is around Rs 42.5. A rough calculation would mean that for an investor who holds 100 shares of Bin Qasim, he will get 25.5 shares of Fauji Fertilizer. The swap ratio of 3.92 shares of Bin Qasim will be converted to 1 share of Fauji Fertilizer. It does seem like a good proxy but such an estimate is based on market prices of the two companies currently.

The Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) dictates that in any such transaction, fair value has to be determined which can be an average of four distinct methods of valuation. By taking four different methods, all aspects can be seen of the two companies and a more holistic approach can be implemented rather than using only one method. The methods that have to be used are net worth method, market value method, discounted cash flows and comparable transaction method. The simple calculation done earlier only encompasses the market value approach. To evaluate this transaction, at least three methods need to be applied and weighted accordingly.

In order to see the mechanics of this transaction, it is important to note another transaction that was carried out in the recent past. Askari Cement Limited was merged

with Fauji Cement Limited just a few years back. In that case, the swap ratio for the two companies was based on discounted cash flow, net worth and market approach. Based on this, the auditors determined that 5 shares of Fauji Cement would be swapped in exchange for 1 share of Askari Cement. The swap ratio was determined and announced within a month of the announcement being made by the board but the process took a painstaking seven months, as regulatory approvals were required from Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) and had to be sanctioned by the High Court. The proposal being made here will also be expected to go through the same process as two companies are merging horizontally. In the face of this, there can be an expectation that it can hinder the market share and monopoly that the amalgamated company will have in the market. There are checks and balances that are placed along the way where first CCP will scrutinise the deal to make sure that the market is not being disadvantaged by the bigger company. The last step is to get the approval of the High Court in order to make sure that the swap ratio that has been determined by the auditors is fair for the shareholders. If they do feel that they are being exploited, they can approach the SECP who will step in to get a more amicable deal for the shareholders.

Due to a lack of comparable transactions being carried out, three approaches will be used in order to determine the swap ratio that might be suggested. The final authority on the actual swap ratio lies with independent evaluators who will carry out their own valuation which will subsequently be approved by the boards of the two companies.

According to the market valuation, Fauji Fertilizer is valued at Rs 253, which is a sum of the parts of the major components being carried out. Around 61% of this value is derived from the fertilizer business of the company while 39% is attributable to the portfolio of companies that it owns. In terms of the same valuation of Bin Qasim, it is valued at around Rs 75 per share which is made up of 62% from its core operations while the rest is from its portfolio companies. Based on the market values, the swap ratio that should be used comes to around 3.36.

In terms of income or net worth approach, it can be seen that the valuation of Fauji Fertilizer comes to Rs 271 per share which is primarily based on its fertilizer business. Similarly, Bin Qasim gives a value of Rs 74.5 per share. Based on these two values,

the swap ratio comes to around 3.59. Lastly, when the breakup value is considered, it gives a book value of Rs 121 for Fauji Fertilizer based on its assets and liability while it is Rs 37 for Bin Qasim. This yields a swap ratio of 3.26 shares. This gives a band of swap ratios ranging from 3.26 to 3.59 with an average value of 3.39.

In order to understand the benefit that will be enjoyed by Fauji Fertilizer after the proposal is accepted, we can consider the latest annual accounts and combine the results of the two companies into one. This will provide a basic guideline to understand how the combined company would have performed if the deal had been carried out before the year ended in December of 2023. The combined results will also be compared to the results of some of the other companies producing fertiliser in order to provide some context to the scale and performance of the new entity in comparison to the industry. The standalone accounts of Fauji Fertilizer will be considered for this analysis as the consolidated accounts will have some earnings and profits from Bin Qasim as the company has a large equity investment in Bin Qasim.

The total assets of the new entity will stand at Rs 370 billion compared to Rs 231 billion of assets held by Fatima Fertilizer and Rs 161 billion held by Engro Fertilizer. One of the major issues that Fauji Fertilizer faces is the fact that more than half of its liabilities is made up of trade and other payables making up Rs 107 billion out of Rs 139 billion. Bin Qasim is also impacted by similar issues as half of its liabilities constitute this. In order to improve the efficiency of the company, one area that needs to be addressed is to cut down on these payables in order to make the new company more efficient going forward. Being a bigger player in the market, the company will be able to enjoy favourable credit terms accordingly.

In terms of combined revenues, the merged company would see revenues of around Rs 353 billion which is 1.5 times more than Fatima or Engro clocking in at Rs 233 billion and Rs 224 billion respectively. In terms of gross profit, the number would be around Rs 97 billion before any efficiencies and cost reductions are taken into account. Fatima and Engro both were able to earn Rs 72 billion for the same period. The result of any cost reductions will only be seen once the merger goes through and the company carries out its operations accordingly. Still,

as a minimum threshold, the company can at least expect this amount of revenues and profits as a conservative measure.

The new Fauji Fertilizer will also see a profit before taxation of Rs 68 billion where its closest competitors earned just below Rs 50 billion in the last financial year. It is evident that in terms of revenues and profitability, the new company will see better results owing to economies of scale and better cost management. As duplication of roles will be eliminated, there may also be layers of the organisation chart which will be removed which will further add to the cost benefits of the merger. Lastly, the new organisation would also be able to get better credit terms from banks going forward which will also lower its finance cost.

As already mentioned, Bin Qasim already has 56% market share in the DAP fertiliser market. Once this deal is carried out, it can be expected that the new company will have 43% of the market share in the urea market and 60% combined market share in the DAP market. This can be a point of contention that can be raised by CCP as the new company will have a larger market share and could impede on the competition in the industry. Assurances will have to be given by Fauji that they will not be involved in price gouging and that they will not start to exploit the market share they have in order to maximise its profits.

While the details of this deal are being hashed out, the half year results for Fauji Fertilizer and Bin Qasim have been announced and they show that both companies are performing on an upwards trajectory.

Fauji Fertilizer saw its sales increase by 60% compared to the half year performance of last year valuing at Rs 116 billion. The company enjoys a lower rate on its gas provision which means that it is able to maintain a higher gross profit margin. The company retained Rs 48 billion in gross profits compared to Rs 31 billion last year. Due to rising finance costs, distribution costs and other expenses, the operating profits did not grow by the same amount as sales. The company earned operating profits of Rs 29 billion compared to Rs 19 billion a year before.

One of the biggest increases was seen in the other income generated by the company. Other income was around Rs 6 billion last year which increased to Rs 16 billion this period. The end result of this was that the company recorded net profits of Rs 26

billion which was double than what it earned last year. Seeing such amazing results, the company also gave out ite biggest interim dividend of Rs 10 per share.

In terms of the performance of Bin Qasim, sales of the company increased by 50% which was due to higher productivity carried out owing to better gas supply and availability. This was translated into better gross profits where the company earned Rs 20 billion this period compared to Rs 6.6 billion in the year. Even though expenses doubled, the company was still able to earn Rs 15 billion in terms of its operating profit which was only Rs 4 billion for the same period of six months last year.

Due to record high interest rates and rupee depreciation, the company saw finance costs of Rs 5.3 billion and exchange losses of Rs 4.6 billion. This year, however, the company was able to cut down finance costs by nearly 60% with better working capital management coming in at around Rs 2 billion. Similarly, as the currency was stable during this period, the exchange losses decreased to Rs 0.2 billion. The company has also made some short term investments which has meant that other income earned by the company has increased from Rs 3.4 billion last year to Rs 8.7 billion this year. This has helped dampen the impact of increase the company has seen in terms of its other expenses which have increased from Rs 92 million to Rs 1.5 billion this year.

The net result of this has been the fact that a loss before tax of Rs 3 billion last year for the same six month period to Rs 19 billion this year. After taxation, the net profit earned by the company this year was Rs 10.6 billion which had been a loss of Rs 5 billion last year.

One caveat that needs to be placed here is that gas is the major raw material used in the manufacturing of fertiliser and the gas pricing policy of the country has been haphazard in the past. What this has meant is that Fauji was able to see much lower cost of production compared to some of its competitors. This led to higher gross margins for the company. Recently, the gas pricing policy is being shifted on a weighted average cost of gas (WACOG) basis which will place a uniform gas price on the industry. Fauji will be a company that will be adversely impacted due to the upward revision in its cost. Fauji is looking to consolidate its position and some of the benefits of the merger will dampen the impact of this policy decision.

Based on the merger going forward, it can be seen that the new company will have better results going into the future as the sum of parts will perform better in the long term. n

Each successive generation is better educated than the one that came before it; democracy and the 18th Amendment help

By Farooq Tirmizi

It is somewhat ironic that one of the best known political satire plays in Pakistan is called Taleem-e-Balighan, set at an adult literacy center in the 1950s. Such centers existed in many parts of Pakistan and were meant to increase the then-abysmal literacy levels in the country, but had almost no meaningful impact on the country’s literacy rate.

If one even tries to talk about Pakistan’s population as an asset, as this newspaper did two weeks ago, the first thing one gets hit with is: “yes, but the people aren’t educated, so they are still a liability.” That illiterate people are economically a liability is not quite accurate, but even leaving that quibble aside, Pakistanis view of just how much progress we have made in improving literacy and education levels in our population is at least partly outdated.

This article is the third in our “optimism about Pakistan’s future” series, and in this one, we will make it a point to concede to the pessimists: they are correct in noting that the state of education in Pakistan is not good, and it is

not improving at a rapid enough pace for us as a nation to be satisfied with. What we will argue, however, is that what we have achieved thus far – and what we are on track to achieve over the next decade – might be “good enough” to achieve industrialization.

We can summarise the analysis of Pakistan’s education sector in the following way:

1. Pakistan lags behind not just developed countries, and the East Asian tigers but also its own regional peers and is uniquely bad in terms of any educational metric across any grouping of countries that could reasonably be described as Pakistan’s peers.

2. Despite woefully inadequate management of the sector, the country has managed to make significant progress in improving literacy and numeracy: the literacy rate among children born in any given year has continued to rise almost uninterrupted over the past several decades.

3. While the government has made some progress in improving the quality of public education, the majority of the increase in Pakistan’s educational attainment levels

has come from household incomes rising – and household sizes falling – to a point where private education became a more viable option for more families.

4. Overall educational attainment levels – measured in the number of years of schooling completed per student – are rising, but very slowly.

5. Economic research indicates that adult literacy rates exceeding 70% are required to begin industrializing (along with several other factors, which we have and will discuss in other articles); and while Pakistan is not quite there overall, it has already hit that level in its urban areas, and will likely hit that level nationally some time over the course of the next decade and a half.

For this story, the data we analysed was taken from the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey (PSLM), published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the latest of which was the one for the year 2020, and the Pakistan Education Statistics reports put out by the Pakistan Institute of Education.

In this article, we will not spend a lot of

time explaining just how far behind Pakistan is relative to its regional peers. That story has been told better by others. Instead, we want to focus on a part of the story that rarely ever gets told: what is Pakistan’s rate of improvement, and are we doing enough to progress as a nation?

First, the good news: every successive generation of children is better educated than the generations before them, and the progress is by and large steady enough that it is measurable from year to year: children born in 2006, for example, were more likely to grow up to become literate than children born in 2005, and so on. Across both urban and rural areas, Pakistan is now able to consistently educate at least 70% of its children to be literate and numerate.

This is a significant improvement over the past several decades. As recently as the 1990s, a literate person in Pakistan was not only part of the minority of the country, but so completely surrounded by illiterate people that it was hard to escape the fact that to be literate meant to be a fortunate minority in Pakistan. Now, it is possible to go several days without encountering an illiterate person under the age of 30 in urban areas in Pakistan.

The patterns for how this progress has happened have been reported elsewhere, but nonetheless bear repeating: men are much more likely to be literate than women (70% of men, and 49% of women, as of 2020); residents of urban areas much more than rural areas (74% urban literacy versus 52% rural literacy), and the young are more literate than older adults (72% for the youth between the ages of 15 and 24 compared to 57% for the overall adult population).

Young men in cities in Pakistan are

approaching close to universal literacy and numeracy (85% across Pakistan). Optimistically, the gender gap is narrowest among young people in cities (urban female youth literacy is 82% across the country).

All of this points to a simple fact: anyone in Pakistan who can get educated chooses to do so. The lack of education appears largely a question of access, not willingness. For all the popular culture references to useless degrees, revealed preference indicates that Pakistanis firmly believe that education itself, and educational credentials in particular, carry value.

Implied in the above picture, however, is a bit of bad news, to which we alluded at the beginning of this article: adult literacy efforts in Pakistan are effectively non-existent. If a Pakistani reaches the age of 18 and has not learned to read or write, they probably never will.

Interestingly enough, however, there is a significant number of Pakistanis who never learned to read and write, but over the course of their adult lives learned to do just enough basic mathematics that, when asked by a surveyor, can correct perform basic arithmetic sums without a calculator. This is not a small population, either. By our estimates using PBS data, we think that as many as 25% of Pakistani adults can be characterized as illiterate, but sufficiently numerate.

This makes sense if you give it some thought: you may have met several illiterate people this past week, but when was the last time you met an adult to whom you gave cash and they could not count how much you gave them or, more importantly, how much you need to give them?

While part of this progress is certainly driven by improvements to the government’s own infrastructure, measured

purely by proportion of the increase in student enrollment, the private sector has contributed just under 75% of the total growth in enrollment between 2009 and 2022, according to enrollment estimates published in the Pakistan Education Statistics reports published by the Pakistan Institute of Education. The public sector accounts for the remaining 25%.

In other words, Pakistanis are not waiting around for the government to fix the schools (even though the government is making some progress on that front). They are simply going ahead and paying for private schools themselves as soon as they have the ability to pay.

This phenomenon helps explain why the fastest progress in terms of increasing literacy happened in the decade after Pakistan’s dependency ratios – the ratio of prime working age adults to the number of children under the age of 15 and retirees over the age of 65 – peaked.

The dependency ratio peaked in 1995, and that year also represented the an inflection point in literacy improvements: for every year after that, the 10-year progress towards improving literacy kept on rising at a rising pace (the second differential was positive) for the next decade.

What does that mean? It means that once families started to find that they had a bit more spare cash to spend (with dependency ratios declining after 1995), they started investing that spare cash into private school fees for their children, especially in urban areas, and especially in the urban areas they did so at nearly identical rates for their sons and daughters.

Having spent the lead up to 1995 being increasingly cash strapped, the first thing that Pakistani families did when the pressure on their cash flows eased a bit was to invest in the future economic productivity of their households by educating their children. And in perhaps a scathing indictment of how bad the public schools were, they did so through

private schools even when public schools were available in their areas.

This increased investment led to the fastest expansion in literacy rates in Pakistani history. Children born in 2004 have a literacy rate of nearly 72%, which is a full 18 percentage points better than children born in 1994. That 18 percentage point increase took place over just 10 years, the fastest 10-year increase at any point in Pakistani history.

Since this increase became possible in large part due to the decline in fertility rates, and through the increased willingness to spend scarce household resources on private school fees and not the heavily subsidized private schools, we are led to the rather extraordinary conclusion that the government of Pakistan’s most effective contribution towards improving literacy in the country was not through the Education Departments of the provincial governments’ building and managing schools but rather through the Population Welfare Departments’ efforts to help with family planning.

Nonetheless, there do appear to be limits to how much improvement the country has been able to achieve over the past few decades in terms of educational attainment levels.

While literacy has been improving relatively consistently, what has not improved by much is the quality and quantity of education made available to the median student in the country. Measured by the average number of years of schooling completed, there has been some progress to be sure in terms of the number of years a given student spends in the classroom, but this progress has been painstakingly slow.

The median Pakistani who attends school is able to at least get to Class 10 (Matric), and in a good year may even pass. The proportion who go on to higher levels has been rising somewhat, and the population of Pakistani college students has quadrupled in the last decade. But that proportion is not enough to have made a meaningful dent in the overall educational attainment levels of the country.

Matric being the point of highest drop-off from the schooling system is interesting: firstly, the fact that Class 10 is conducted across Pakistan’s education system like a terminal diploma

program (the government issues an actual certificate for pass Matric that it does not for previous levels) makes it feel like a natural drop off point. It is also a point that the median student achieves sometime after the age of 15, which is the age where the trade-off between continued schooling and entering the workforce as a literate young adult starts to become meaningful. And in another instance of revealed preference, it appears that the median Pakistani family believes in education enough that they feel the need to spend money to ensure that their children are literate and numerate, but investing beyond that level is not seen as being worth the cost of having a 15+ year old child of theirs continue to be a cost center rather than an income generator.

This is despite the fact that, post-Matric, the educational options available to Pakistani students start to become skewed towards public education, meaning it may actually end up being cheaper for a family to send their child to a postClass 10 educational institution than the fees that they paid to get the child to the Matric level.

Despite two decades of rising private sector enrollment, two-thirds of Pakistani students who go on to Higher Secondary (Intermediate) education do so at government institu-

tions. And nearly 85% of university students in Pakistan attend government universities. Both of these levels of education, at government institutions, are heavily subsidized, and yet these are also the levels that most students are choosing to not pursue.

The picture of the education sector in Pakistan, therefore, is clearly a mixed bag. It is not as uniformly bad as the public conversation around it might have you believe: literacy rates are clearly rising across generations and our still-young population means that the effect of educated children on our adult literacy rates will likely be quite rapid.

On the other hand, it is abundantly clear that educational standards in Pakistan are so low that we do not even bother to compare outcomes in Pakistan to those of globally competitive economies, whether in our own region or further afield. And on this front, progress – though unmistakably occurring – has been far slower. We are getting more children into school but not really doing much to keep them in longer, or teaching them much better than in decades past.

In short, what we have in terms of education is certainly not good.

But is it “good enough”? What would even constitute “good enough”?

It is our contention that while Pakistan is unlikely to become the kind of country that leaps from third world to first in one generation, a la Singapore, we might be able to make decent progress towards at least second world status in one or two generations.

Pakistan’s educational attainment levels are clearly not enough to become a high-tech manufacturing hub, or even a large services economy. But have we done enough to at least

start industrializing with basic and intermediate level industries? The answer to that question is: most likely, yes.

Economists who have studied early industrialization among major economies around the world have come to the conclusion that, while universal literacy would certainly be great to have, an economy at the earlier stage of its economic development can make do with as little as 70% adult literacy rates, a number that Charlie Robertson, economist at the London-based hedge fund FIM Partners, calculated for his book The Time Traveling Economist.

Pakistan is clearly short of that number, currently at close to 60% adult literacy rates. In urban areas, we are already past 70%, however, and in all of Pakistan 10 largest cities, adult literacy rates approach or exceed 80%.

The common retort to these statistics is: yes, but what good is basic literacy? Our response: good enough for our current stage of economic growth.

The median Pakistani worker does not need to compose a complicated report on macroeconomic trends in Pakistan’s trading partners, or write code for a new large language model (LLM). They need to be able to read enough to know that the clothes they just stitched at the textile factory they work at need to be placed in the box marked “Germany”, not the one marked “America”.

Is that level of skill and manufacturing how you build a globally competitive economy? No, but that is first step on the ladder to get from where we are right now to that globally competitive economy. In an ideal situation, we would have spent much more of our national resources on education and, far from being a byword for a biting satire on state failure, Taleeme-Balighan would have referred to how Pakistan educated its people out of poverty.

But we are not that country, so we must make do with what we have. The attitude Pakistanis seem to have is that if the change will not have in one generation, it is not worth pursuing, and we would suggest that this is at least a

two-generation project in any country not led by Lee Kwan Yew.

If you view Pakistan’s education system from the lens of the question: “is this coming generation of workers educated enough to compete with workers in America, Germany, or even Mexico?”, the answer you will arrive at is “no”. But if you ask the question: “is this coming generation of workers educated enough to start working at the kind of basic industries that will increase their incomes five-fold in one generation and allow them to afford to educate their children to become the generation that competes against the best in the world?”, the answer to that question might be “yes”.

(The lack of investment in education, by the way, is why Ayub Khan’s much-vaunted Second Five Year Plan failed. The South Koreans studied that plan and implemented many of its components, but added one crucial difference that the Ayub Khan Administration did not: an insistence that every single illiterate adult attend school at night to learn how to read and write.)

A retort to the above assertion that Pakistan’s catch-up economic growth will take longer might be that any goal is easier to achieve if you redefine it downwards. We would submit to you that even making steady progress towards achieving middle income country status would result in more uplift in the material wellbeing of Pakistanis than we have ever achieved in our history.

It is a goal “good enough” to ensure that our fellow citizens no longer live in abject poverty, even if it means that Dubai will continue to feel expensive to our upper middle class when they visit. More importantly, it is a goal “good enough” to not require our national leadership to spend their days dreaming up cockamamie schemes like CPEC or the next hare-brained idea to get the Americans to give Pakistan more money and instead focus on an endogenous engine of economic growth.

Now that may well be a goal that is not just good enough, but also just plain good. n

The fallout of climate change is upon us and the startup space is rising to it with innovation

Cleantech is having a moment in Pakistan’s startup scene. From energy initiatives to sustainable agriculture solutions, innovative ventures are sprouting up across the country at an unprecedented rate. But what’s driving this green revolution in the entrepreneurial landscape?

Recent months have seen a flurry of activity in the sector. The Climate Finance Accelerator (CFA) conducted an investment roadshow, while USAID’s Private Financing Advisory Network (PFAN) also showcased its cohort of cleantech SMEs to potential investors. Meanwhile, the likes of Accelerate Prosperity are ramping up support for eco-friendly startups, particularly in Pakistan’s underserved regions.

This surge isn’t limited to funding opportunities. Incubators and accelerators are increasingly focusing on climate-related innovations. The National Incubation Center (NIC) Faisalabad now brands itself as an agritech incubator, Innovate 47 has launched a dedicated climate accelerator, and New Energy Nexus recently announced its partnership to support clean energy ventures in Pakistan.

The urgency behind this trend is clear – Pakistan is grappling with the intense fallout of climate change, as evidenced by the recent devastating monsoon rains. But beyond the ‘why,’ this article aims to explore the burgeoning landscape of cleantech startups in Pakistan.

What unique challenges do these ventures face? And more importantly, how can they overcome these hurdles to create lasting impact?

But before answering this question, let’s get two things out of the way. First, while ‘climate tech’ is the globally preferred term for such initiatives, ‘cleantech’ remains more commonly used in Pakistan. For consistency, we’ll use ‘cleantech’ throughout this article.

And the segments included within this definition are carbon tech, industry, sustainable foods, low-carbon mobility, dispatchable energy sources, clean fuels, built environment, land use, intermittent renewable energy sources, grid infrastructure and agritech.

Now let’s take a look at what’s been happening in the global funding scene. It’s been a rough couple of years for investors in cleantech, to say the least. Geopolitical chaos, valuations taking a nosedive, inflation creeping up, and interest rates climbing. It comes as no surprise that private markets across the board have taken a hit. Resultantly, total venture and private equity investment, as per PwC, dropped by a massive 50.2% compared to last year, bottoming out at $638 billion in 2023. Now, cleantech startups didn’t get hit quite as hard, but they still took a pretty big knock – funding fell by 40.5%. To put that in perspective, the funding levels for the vertical are back to where they were five years ago. But there’s a silver lining. The fact that cleantech didn’t fall as hard as the overall market is an indicator there’s still some fight left in this sector.

Additionally, investors have shown growing interest in this sector, with dedicated funds gaining momentum. In 2022, dedicated VC funds successfully raised a record $18.7 billion in capital. While the levels plummeted in 2023, there was a notable resurgence in 2024. Adding to this tally is Bill Gates-backed climate VC, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, that has secured $839 million to raise its third flagship fund.

The writer is an Editorial Consultant at Profit and can be reached at ahtasam.ahmad@ pakistantoday.com.pk

Pakistan is a key signatory of the Paris Agreement. Under its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the country aims to reduce emissions by 50% by 2030. However, progress toward these goals is lagging, largely due to a massive climate financing gap. Current funding for mitigation projects is only about one-fifth of what’s

needed, while adaptation projects are receiving just 6% of required financing.

Cleantech ventures could help address this gap in two ways: By attracting international investments and climate financing and by reducing overall funding needs through cost-cutting innovations and local solutions.

To gauge the state of Pakistan’s cleantech ecosystem, it’s crucial to view it within the broader startup landscape. The overall startup scene hit funding peaks in 2022, but faced a slowdown in 2023, with 2024 shaping up to be even tougher.

This downturn hits the cleantech sector particularly hard, given its already modest footprint. Cleantech has accounted for only 2-3% of total startup fundraising over the past five years, with investments primarily focused on e-mobility and agritech. Moreover, the average deal size in the sector is less than half that of the overall startup ecosystem.

Now, that in itself is a problem. Cleantech businesses usually are more capital intensive and need higher capital injections (explained later) at multiple stages compared to conventional ventures. A trend that has been identified globally.

Nevertheless, the sector in the country presents significant untapped potential, as emphasized in the study “Cleantech Ecosystem of Pakistan” by USAID-PFAN. Key areas primed for growth encompass: Renewable energy - the escalating power tariffs are paving the way for solar and wind energy options.

E-mobility - the substantial fuel import expenses are fueling the demand for electric vehicles and associated infrastructure. Circular economy and carbon tech - the increasing emphasis on sustainability solutions is creating avenues in resource efficiency, waste minimization, and carbon capture.

Cleantech ventures face a unique set of challenges compared to conventional startups in the tech ecosystem. These challenges stem from the nature of the industry and the specific context of Pakistan’s market.

Firstly, cleantech startups typically require more time to develop their minimum viable products and bring them to market compared to other tech-based solutions. This extended timeline can strain resources and test investor patience.

Secondly, Pakistan faces a significant shortage of specialized human capital, such as engineering talent for electric vehicles, and lacks the necessary infrastructure like specialized manufacturing facilities.

Many entrepreneurs in this sector tend to focus heavily on technology development, sometimes at the expense of building a viable business model around their innovations. This imbalance can lead to impressive technical solutions that struggle to gain market traction.

the commercial stage due to these compounded difficulties.

Furthermore, the niche nature of some cleantech solutions, whether due to cost or limited appeal, can restrict their market potential.

This limitation often discourages venture capital investment, as VCs typically aim for returns of 3x to 10x their initial investment—a target that’s extremely challenging to achieve within a confined market segment. A challenge that the e-mobility segment in the country is currently facing.

Source: World Bank

The high upfront costs associated with cleantech solutions present another hurdle. Customer adoption often depends on affordable financing options, which are currently scarce in the market. Solar energy systems and e-mobility solutions are prime examples of technologies facing this challenge.

Moreover, there’s a general lack of awareness and resistance to adoption among potential customers.

This hesitancy can slow market penetration and growth for cleantech startups. These ventures also typically require significant component imports, inventory, and working capital. Unlike software or other asset-light businesses, these startups need substantial capital in their early stages and generally take longer to break even and scale up. These challenges culminate in a critical issue: limited opportunities for market expansion. Many cleantech startups struggle to progress from the MVP stage to

While challenges abound, solutions are within reach. Funding remains a critical issue, but impact funds like Acumen Pakistan’s GCF-anchored initiative offer a promising alternative to traditional venture capital.

Policy support is gaining traction, as evidenced by recent government allocations for electric bikes and energy-saving fans. These interventions, coupled with targeted monetary incentives for innovators, could significantly boost cleantech adoption.

Education and infrastructure development are equally crucial. Investing in specialized incubators, accelerators, and climate-focused curricula will build much-needed expertise.

Meanwhile, creating testing facilities can bridge the current knowledge gap, fostering more efficient technology development. Localization presents another key strategy. By developing ancillary industries and focusing on local production, costs can be reduced for both businesses and consumers, making cleantech more accessible and economically viable.

Despite economic headwinds, Pakistan’s cleantech sector shows promise. With proactive measures, it stands poised to drive both environmental sustainability and economic growth. n

Can the government finally seal the deal on the privatisation of FWBL?

Founded in 1989, the bank has been up for sale before. This time with the IMF watching, how will things be different?

By Hamza Aurangzeb

It is 2024, and Pakistan’s government is on a mission to Marie Kondo its possessions.

On the advice of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the government is attempting to privatise

at least 25 state-owned companies. Why? The fund believes this will help tighten the belt on spending and kickstart the economy. On the chopping block are some national institutions, perhaps the most famous case study being Pakistan International Airlines (PIA). But there are other storied national companies that are undergoing a massive change.

Take the example of the First Women Bank Limited. Founded in 1989 by Benazir Bhutto, the FWBL was meant to be a haven for Pakistani women looking for financial independence, and a way to increase financial inclusion in the country. But over its 35 year journey, the bank has at times faltered and this would not be the government’s first attempt

The fragmented research conducted by the First Women Bank Limited on the female market segment limited its effectiveness in incentivizing women to utilise its financial services and mobilise funds for women-led ventures in Pakistan.

As a result, it underperformed and did not fully achieve its goal of financial inclusion of women in

Pakistan

Naveen Ahmed, an investment banking professional

to sell it. So what is the deal this time and how will this attempt be different?

The First Women Bank Limited was set up on November 21, 1989 by Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, the first woman to become head of government of a Muslim-majority nation, with much fanfare. “Let the Women’s Bank be a pioneer in helping Muslim women secure economic independence and career satisfaction, within the cultural ambiance and social values of an Islamic society.” she said, at the bank’s commencement on December 2.

Cultural pandering aside, there was always a need for an institution like FWBL in Pakistan. Pakistan has one of the largest unbanked female populations in the world. Currently, if you are a woman in Pakistan and have a bank account that makes you part of only 39% of the female population that has access to formal banking facilities. And that is according to a very loose definition of “banked” set by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). The SBP is counting women that have signed up for digital wallets such as JazzCash and Easypaisa. They are also conveniently not taking into consideration data that shows the patterns of how these female participants in the formal economy behave. In December 2022, only 62 lakh women in Pakistan owned debit cards, accounting for only 19% of debit cards in the country. Put another way, only 36.2% of the scheduled banking accounts of women had a debit card, compared to 55.3%c for males. So even when women have a proper bank account — not a digital wallet — they are far less likely to get something as basic as a debit card. And according to a 2023 report, while the SBP might claim 39% of women in Pakistan are banked, the World Bank puts this figure closer to 11.5%.

And these are numbers that have risen over the past four years, a time in which the

central bank to their credit has pushed for female financial inclusion. In 2020, the SBP’s estimate of the banked female population was an embarrassing 17% compared to the South Asian regional average of 64%. In 2008, that number stood at a paltry 8%.

One needs to understand that the FWBl was an entirely different machine in 1989. This was a time when women had not joined the white-collar workforce in the numbers they have now and banking institutions were weak. As such, the goal was to provide as much access to capital as possible for the average woman.

The FWBL quickly got to work. The premise of the bank was simple: it would cater to women at all levels of economic activity, including micro, small, medium and corporate. It was the first commercial bank to launch microcredit in Pakistan.

The bank’s credit lending policies encouraged asset ownership among women as it lent to institutions, where women held 50% shareholding, women were the managing director or women made up more than 50% of the employees.

FWBL was set up with an initial paidup capital of Rs. 10 crores, where 90% of the capital was provided by five banks namely, the National Bank of Pakistan, Habib Bank Limited, MCB Bank Limited (formerly: Muslim Commercial Bank), United Bank Limited, and Allied Bank Limited, all of which were stateowned at the time; while the rest of the 10% were provided by the federal government of Pakistan.

As of today, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) holds about 82.64% stake in the bank, whereas, HBL and MCB both have a 5.78% stake each, ABL has 1.94%, and NBP and UBL both possess 1.93% each.

The bank commenced its operations in 1989 with five branches spread across the country, rapidly expanding to 23 in a span of four years.

However, after that, the bank only managed to increase its count to 38 branches until 2010, and now as of 2023, the bank operates only 42 branches across 24 cities of Pakistan. It is conspicuous that women in Pakistan are desperate for access to credit and formal financial services even today. Only one percent of the women in Pakistan have the resources to start new ventures, this represents the stark gender disparity in the entrepreneurship domain of the country.

Furthermore, there is a humongous gap between men and women who hold a financial institution account. As we’ve mentioned earlier, women make up only 4.9 crores of the total 17.7 crore accounts in the country. However, only 2.9 crore individual women, or 43% of the female adult population, are associated with these 4.9 crore accounts. Admittedly, while these numbers are low, they have been worse. Adult female account ownership stood at 4% in 2008 and 18% in 2020, but it has increased to 43% as of 2023.

A more granular look into the data reveals that 3.23 crores out of these 4.9 crore accounts belong to the segment of branchless banking, which is provided by digital mobile wallets like JazzCash and Easypaisa. However, such wallets only provide limited financial services. This indicates that although Pakistan has made progress towards establishing a pluralistic system cognizant of the financial needs of women but far from reaching its goal. These historical numbers make the abysmal performance of FWBL apparent.

Most of the women entered the financial system in recent years with the help of SBP’s policy interventions like Banking on Equality and the growing footprint of digital mobile wallets rather than the initiatives of FWBL.

Therefore, in 2016, FWBL diverged from its original philosophy and reformulated its strategy by adopting an inclusive approach that embraced both men and women. They not only commenced serving men but

The government of Pakistan has historically believed that it is facilitating its citizens by operating businesses. However, government-led institutions like the First Women Bank Limited typically lack the incentive to maximise shareholder value. This results in an inefficient allocation of funds and resources, the burden of which is eventually borne by the taxpayers it intended to assist

Yousuf Farooq, Head of Research at Chase Securities

also appointed them to senior management positions.

The bank’s inability to fulfil its objective of women empowerment, while remaining profitable compelled it to reorient itself. This rearrangement assisted the bank in reducing its infection ratio, constraining its non-performing loans, and growing deposits to a certain extent but its revenue and net income worsened.

FWBL, an institution with an ingenious vision that had monumental potential to enhance the status of women across the domains of commerce and entrepreneurship failed to live up to its expectations. It could have become a globally renowned bank for women and expanded to regions like the Middle East and Central Asia, but it wasn’t meant to be. The bank is now in shambles, as revealed by its financials, and left at the mercy of the privatisation commission.

“The fragmented research conducted by the First Women Bank Limited on the female market segment limited its effectiveness in

incentivizing women to utilise its financial services and mobilise funds for women-led ventures in Pakistan. As a result, it underperformed and did not fully achieve its goal of financial inclusion of women in Pakistan,” remarked Naveen Ahmed, an investment banking professional based out of Karachi.

In 1993, the FWBL was lauded by the international media in 1993 with the headline “Pakistan’s Profitable First Women’s Bank Carves New Niche” and it performed decently throughout the decade of the 2000s. We analysed the financials of the bank from 2001 to 2023. FWBL achieved a revenue of Rs. 26.7 crores in 2001, which increased to Rs. 99.6 crores in 2011, growing at a rate of 14.1%, primarily due to its great outreach to female borrowers in rural areas. Approximately, 76.7% of FWBL borrowers were females from the micro credit segment.

This impressive outreach became possible only because of the cooperation of NGOs and mobile credit officers in rural areas. However, gross advances of the bank failed to keep up pace as they only grew at a rate of 4.3% from 2011 to 2021 in comparison to 25.2% from 2001 to 2011. Furthermore, the declining interest rate exacerbated the situation for FWBL, the policy rate went from 13.5% in 2011 to only 5.75% in 2016. Hence, the bank’s revenue stagnated after 2011 and expanded at a snail’s pace to reach Rs. 109.2 crores by 2021. Nevertheless, the bank’s revenue increased once again and doubled to Rs. 218.5 crores in just two years primarily due to high interest rates in 2022 and 2023. While inspecting the profitability of the bank, measured through return on equity (ROE), it is clear that the bank had satisfactory profitability ratios during the epoch of 2000s, where the highest rate was observed at 24.8% in 2003, while the lowest rate stood at -7.3% in 2009. After 2011, the bank’s ROE started to dwindle and reached negative territory. There were two primary reasons for this, firstly, the non-performing loans of the bank shot up significantly. They went from Rs. 52.3 crores in 2011 to Rs. 1.99 crore in 2018. The bank, adhering to its objective of women empowerment, continued to advance loans to females with limited credit history. Along with this, lending to customers with political influence drove up non-performing loans. Secondly, the banks’ margins were slashed considerably, as the SBP cut the width of the interest rate corridor in a low interest rate environment. This resulted in banking spread falling to multi-year lows adversely impacting the markup income of FWBL. However, the bank made a brief comeback in 2019 and 2020 as its ROE turned positive before crumbling to its lowest point of -44.7% in 2021. The bank’s profitability improved once again, delivering an ROE of 6.8% in 2022 and 17.2% in 2023, respectively. This improvement was driven

by strengthened net interest income and reduced non-essential expenses.

Another important metric incorporated into the analysis was deposits, which represent the trust of the customers in the bank. The bank racked up deposits from 2001 to 2012, as they increased from Rs. 616.7 crores to Rs 1919.3 crores (Rs 19.19 billion) at a rate of 10.9%.

However, as technology advanced and financial inclusion of women improved in Pakistan, competition for the deposits of women intensified. FWBL simply failed to distinguish itself from other traditional or modern digital banks with top-notch services. Hence, the bank’s deposits declined at a rate of 1.1% to Rs. 17,71 billion in 2019.

Further, interest rates in Pakistan have remained elevated since 2019 for the majority of the time, which has encouraged customers to deposit money in savings accounts, leading to a surge in the bank’s deposits once again post-2019. The bank’s deposits expanded at a rate of 15.3% to reach an all-time high of Rs. 31.32 billion in December 2023.

The First Women Bank’s gross advances continued its upward trajectory at a steady pace of 22.7% from 2001 to 2013, they went from Rs. 83.2 crores in 2001 to Rs. 966.9 crores in 2013. Afterwards, they ran out of steam and crept at a rate of 2.8% from 2013 to 2021 to reach Rs. 12.5 billion.

During 2022 and 2023, the bank’s gross advances contracted further and stood at Rs. 844 crores as of 2023. This was primarily driven by the diminished lending activity of the bank and the degraded credit risk in the bank’s portfolio, which created a tempestuous operating environment for the bank.

A trend evident in its infection ratio is that it has been increasing since 2006, but it remained below 10% until 2013, after which

it escalated to 15% from 7.9% in a year. The situation deteriorated further in 2016 as its infection ratio increased to 20.7%. The banks’ infection ratio has remained above 15% ever since 2014, and currently sits at 24.6%, the highest in its twenty-year history. It is discernible from the financials of the bank that it maintained a healthy bottom line from 2001 to 2011, its net income increased from 10.1 crores in 2001 to 25.8 crores in 2011 at a rate of 9.9%. It is quite an impressive performance considering its clientele was limited to women-oriented enterprises.

However, the bank’s net income plummeted after 2011, as it either incurred massive losses or remained marginally profitable until 2018. This was driven by a large stock of non-performing loans, a narrow spread, and modest growth in gross advances.

Acting President Naushaba Shahzad

turned around the bank’s performance after 2018 through business development, product innovation, and enhancements in internet banking. Additionally, she established a 24x7 call centre and relocated several branches to augment the bank’s brand identity and amplify its visibility.

Although the strategy pivot in conjunction with a high interest rate environment ameliorated the financials of the bank during 2019 and 2020. However, this revival proved to be ephemeral and fizzled out as soon as the management changed and high interest rates left the scene. Afterwards, the bank’s capricious performance continued; it reported a loss of Rs. 141.6 crore in 2021, but posted a profit after tax of Rs. 16.8 crores and Rs. 52.3 crores in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

These profits were fundamentally generated by the bank’s investment in government securities, which not only prevented capital erosion but also provided stable returns.

Our perspicacious analysis reveals that all major metrics of the bank began moving south during 2011 and 2012 and continued to do so until 2018. FWBL’s revenue declined by 13.2%, deposits shrunk by 4.3%, net income plunged by 276.6%, return on equity contracted to -13.8% from 15.0%, and the infection ratio jumped from 6.6% to 18.5% during this period. This appalling performance of the bank persuaded the government to initiate the privatisation of FWBL in 2018.

Historically, various governments on multiple occasions have contemplated privatising the bank, particularly in the years 1994,

1996, and 2015, however, on October 31, 2018, the Cabinet Committee on Privatisation (CCoP) put FWBL on the Active Privatisation Programme, which was later sanctioned by the federal government on November 1, 2018. Hence, the Privatization Commission (PC) disseminated a Request for Proposals (RFP) on October 18, 2019 for technical and financial proposals.

Once the technical and financial evaluation of the bids concluded, the syndicate of MIS Bridge Factor & National Bank of Pakistan were chosen as the Financial Advisor for the privatisation transaction of the bank by PC on December 27, 2019. The Financial Advisory Services Agreement (FASA) was signed on January 27, 2020.

The due diligence report of FWBL was filed in June 2020 under the supervision of the Ministry of Privatization, while the Cabinet Committee on Privatisation approved the Transaction Structure on August 21, 2020. Nevertheless, due to the unavailability of audited accounts (FY 2018 to FY 2021) later steps could not be fulfilled such as Expression of Interest (EOI)/Request for Statement of Qualifications (RSOQ).

Although the FASA was signed for only two years, it was extended twice, first for another fifteen months till April 26, 2023, and then for another two years till April 25, 2025, as per the approval of PC.

The government of UAE communicated its interest in acquiring 82.64% shares of the federal government in FWBL through a formal agreement, congruent with relevant laws and regulations. The federal government has authorised the Privatisation Commission (Government-to-Government Agreement Mode, Manner, and Procedure) Rules, 2023,

conducive for such transactions under the Inter-Governmental Commercial Transactions Act, 2022.

The financial advisor has commenced the valuation process for the government’s shares in FWBL utilising methodologies embedded in the above-mentioned rules. The federal cabinet approved the privatisation commission’s recommendations regarding FWBL, which are essential for scrutinising the UAE government’s proposal.

The following steps encompass instructing the Privatization Commission to move forward with the bidding process or referring the transaction to the Cabinet Committee for the constitution of a Negotiation Committee, ratification of the price discovery mechanism, and reference price, as per the Inter-Governmental Commercial

Transactions Act, 2022, and associated rules.

“The government of Pakistan has historically believed that it is facilitating its citizens by operating businesses. However, government-led institutions like the First Women Bank Limited typically lack the incentive to maximise shareholder value. This results in an inefficient allocation of funds and resources, the burden of which is eventually borne by the taxpayers it intended to assist. Hence, the government should focus solely on acting as a regulator,” elaborated Yousuf Farooq, Head of Research at Chase Securities.

Although the government of Pakistan has ventured out numerous times to privatise FWBL, it has never been able fulfil the task at hand because of no compulsion urging the government to offload the bank.

However, this time the circumstances are a bit different, the government has been obligated by the IMF to abandon numerous SOEs, including FWBL, to abate its fiscal deficit. The government complying with the demands of the IMF has expressed its determination to expedite privatisation by unveiling a five-year Privatisation Program 2024-2029.

As per the program, FWBL is supposed to be privatised by the end of fiscal year 2025, which appears to be more likely than ever as the government finds itself in a tight spot with no other viable options. The sooner this white elephant is sold to a well-reputed investor, the better it will be for all stakeholders, including the government, the bank, and the taxpayers. n

Business owners sceptical of indicative incomes under the Taajir dost scheme; how just is their plea?

Shahnawaz Ali

Most salaried individuals in Pakistan look at business owners with some level of contempt. To them, these business owners that deal in cash and avoid taxes are why the tax burden keeps increasing on those already documented.

In some parts it makes sense. Business owners in Pakistan do often go under the radar of the tax hounds, but the reality of the problem exists with tax collection in Pakistan and the FBR continuing to deepen their tax net instead of widening it.

And they are justified in their claims. Business owners in Pakistan have since long avoided the tax net. A large number of them are either not registered with the FBR, or even if they are, they have the luxury of under-reporting their incomes, due to lack of scrutiny.

The constant criticism in this entire time has been the FBR continues to bring the hammer down on the salaried classes and fails to capture tax revenue from these businesses. Recently, in an effort to change this, the FBR tried to reinvent the wheel. They announced a scheme in six cities meant for retailers to voluntarily sign up to. Providing them with easy access through mobile apps and benefits of early registration, the FBR was aiming to bring all the businesses inside the tax net.

The first was introduced as a pilot project in a limited number of cities to test its feasibility and impact. It was aimed at understanding the challenges and opportunities associated with bringing a diverse and largely informal retail sector into the tax net. The pilot phase involved extensive consultations with stakeholders, including trade unions, business associations, and retailers, to design a tax regime that is both fair and easy to comply with.

While only a few retailers reportedly signed up for the scheme, the “success” of the pilot phase, coupled with the pressing need to increase tax revenues and formalise the economy, led to the decision to expand the scheme nationwide. In reality, the FBR has put its foot down on retailers, wholesalers and business owners, in which everyone from a kiosk owner to a tier 1 retailer is required to register themself and pay monthly advance tax on their income.

The complication comes in how this advance tax will be determined. For this determination the FBR has come up with a term called “indicative income”. To find out more about the indicative income we need to first learn about the whole system that is already in place.

Before the introduction of the Tajir Dost Scheme, businesses in Pakistan, particularly small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and retailers, were subject to a more complex and traditional tax regime. This system involved various types of taxes, compliance requirements, and administrative challenges that often led to underreporting of income, tax evasion, and a large informal economy. Here’s businesses were paying their taxes before the Tajir Dost Scheme:

The primary legislative framework governing income tax in Pakistan is the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001. This ordinance outlines the tax obligations of individuals, associations of persons (AOPs), companies, and other entities.

Any businesses wishing to pay income taxes were required to register with the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) and obtain a National Tax Number (NTN). This registration was often viewed as cumbersome, requiring extensive documentation and interactions with tax authorities.

Upon registration, these businesses were subject to multiple types of taxes, including, Sales Tax, Withholding Taxes, and Advance Income Tax.

The advance tax, more commonly known as the income tax, had to be paid by businesses in quarterly instalments based on their estimated income for the quarter, and in turn the whole year.

The tax rates varied based on the type of business entity and the income slab. For example, corporate tax rates for companies could range from 29% to 35%, while individual and AOP tax rates were progressive, depending on the income level. These taxes, while progressive in theory and higher on paper in terms of percentage when compared to salaried class, did not often yield the desired results. The problem was that any business, slightly informal, had to come up with a sales figure for themselves, proof that income level and pay the tax on that income.

Businesses would do this when filing their annual income tax returns, declaring their income, expenses, and tax payable. The process was often complex, requiring detailed financial records, something that informa businesses willingly do not possess.

While the FBR conducted audits to verify the accuracy of the tax returns filed. Audits could be random or targeted based on risk assessments. The general view was that these assessments were largely corrupt and did not capture the entire picture.

In case of discrepancies, the FBR could issue assessment orders, determining the correct amount of tax payable and businesses had the right to appeal against these assessments but the

incidence of this happening was often seldom.

The traditional tax system was often seen as complex and burdensome, especially for small businesses with limited resources. A significant portion of the economy operated informally, with businesses avoiding registration and compliance to evade taxes.

High compliance costs and perceived corruption led many businesses to underreport income or not file returns at all and frequent interactions with tax authorities, audits, and disputes increased the administrative burden on businesses.

Retailers, in particular, faced challenges due to the informal nature of many small shops and the difficulty in tracking cash-based transactions. Many small retailers did not maintain formal books of accounts, making it hard to assess their true income. Small and medium enterprises often struggled with the lack of professional expertise to manage complex tax filings and compliance requirements. It is surprising that ever since 2001, this system has been in place. All the aforementioned discrepancies have been mentioned, more or less, by the FBR itself in its bid to install the new Tajir Dost Scheme. For a long time the government has been scratching its head, as to how to conquer these problems. It would occasionally introduce tax amnesty schemes, allowing businesses to declare undisclosed income and assets without facing penalties.

Quite recently the FBR started integrating technology to simplify tax filing processes, such as online tax returns and e-payments. The introduction of the POS scheme is a notable one in this regard. However, none of this seems to have worked on the common retailer. Your everyday kiryana store owner. The problem becomes a huge one when large scale distributors also hide under the cloak of that “kiryana store” owner, saving themselves from a huge tax liability.

The introduction of the Tajir Dost Scheme aimed to address these challenges by simplifying tax compliance, broadening the tax base, and formalising the retail and SME sectors. The scheme’s key features are fixed monthly taxes based on shop valuation and reduced administrative burden. The FBR claims that they are designed to encourage voluntary compliance and reduce the informal economy’s size.

By offering a more straightforward and predictable tax regime, the Tajir Dost Scheme seeks to create a more conducive environment

for businesses to operate within the formal economy, thereby increasing government revenues and promoting economic stability.

But here is the twist. How will the FBR determine the fixed monthly taxes based on shop valuation? Which valuation will they use? The FBR valuation?

Enter the indicative income! The concept is simple. Indicative income refers to an estimated income level determined by the tax authorities based on various factors such as the rental value of the property, its location, and its fair market value. This income estimate is then used as the basis for calculating the advance tax that a retailer must pay. The article will elaborate further on what indicative income entails later.

So based on what area the business setup is in, the business owner will now pay a fixed amount of tax in advance, every month and will file an annual tax return, adjusting for other advance taxes paid during the year such as electricity and other utilities.

Let’s assume there is a shop in the MM Alam Road Area of Gulberg, Lahore. Let us also assume another shop of a similar size in the Moon Market of the Allama Iqbal town of Lahore. The indicative income determined by the FBR for the former is around Rs 28 lakh per year while that for the latter is 22 lakh. This makes the advance tax liability for an MM Alam road business owner close to Rs 45 thousand per month, while the same liability for the Moon Market business owner becomes Rs 30 thousand per month.

What the scheme does is, it offers a simplified tax regime with fixed monthly taxes based on the fair market valuation of shops, making it easier for retailers to comply without the complexities of traditional tax filing. It also reduces the burden of detailed assessments of those taxes by the regional tax collector’s office. The Special Rules 2024 provide specific criteria and exemptions for certain retailers, making that a whole different case.

Non-compliance with the regime can lead to penalties, including shop sealing and imposition of default surcharges. While this serves as a strong deterrent against remaining outside the formal tax net such penalties have always been in place. The FBR, now has the authority to seal a shop for 7 days on first incidence of non-compliance and 21 days for consequent non-compliance.

According to the recent SRO 1064(I)/2024, income tax authorities now also have the power to impose penalties and enforce compliance measures, which could include prosecution proceedings if the non-compliance breaches a certain threshold.

The mandatory elements of this scheme are that retailers are required to pay advance tax monthly. Failure to do so can result in the aforementioned penalties. The collaboration between

FBR and trade unions further streamlines this registration indicating a move towards making registration almost unavoidable.

Specific provisions for small shops and exemptions for those with existing tax filings encourage broader participation. For example, a kiosk owner, more intuitively known as a “thela” will have to pay a fixed tax of Rs 1200 per year or Rs 100 per month.

The system might definitely be able to achieve the goal of higher tax revenues however, there is obvious concerns

Let us go back to the example of MM Alam Road and Moon Market. What is it that drives profitability and income for business? Is it its presence in an expensive area or is it volume of sales? A food shop at MM Alam road that serves stale food, for example, would make much less in terms of profits and revenue as opposed to a cloth shop in Moon Market that has a good reputation.

So much so that their incomes become starkly different from each other and their respective indicative incomes. Now the TDS way might be good to take out at least a minimum share of tax from a business that was not paying any tax otherwise but is ideal when it comes to righteous estimations of income?

More importantly, if the business is in loss and does not make as much as they are expected to make according to the FBR’s estimations how will they pay the subsequently excessive advance tax? The FBR of course has a provision for appeal, in case of businesses that have a discrepancy like that but that brings us back to the initial problem of interacting with the authority and attempts of bypassing and sometimes dealing with bureaucratic red tape.

Therefore there is an obvious concern that the indicative income may not accurately reflect the actual earnings of a business and the reliance on factors like rental value and location may lead to overestimation or underestimation.

It is important to understand that each business is unique, and a standardised approach may fail to account for specific circumstances affecting a business’s profitability. Some businesses like the wholesale business, work on a small profit margin yet higher volumes, while others remain hugely profitable despite having a lower volume of sales.

Talking to profit, a senior tax professional on the subject of anonymity said that the scheme is primarily a tool for the FBR to collect data. However, in the same breath this expert suggests that the discretionary power given to tax authorities to determine indicative income could lead to corruption and favouritism. Retailers may be subject to undue influence or pressure and that becomes another cause of concern, not very different from previous concerns.

While a lot of tax burdened Pakistanis may not agree, the burden of tax on small businesses, especially those operating on thin margins can be massive. They may find it challenging to pay taxes based on an inflated indicative income and lead to potential closures.

But the biggest fear that the FBR needs to consider is a fear of being assessed at a higher income level than actually earned might discourage small retailers from registering under the scheme, undermining its goal of broadening the tax base.

The new system may also lead to an increase in disputes between retailers and tax authorities over the accuracy of indicative income assessments. This could result in a backlog of appeals and increased administrative burden. While the FBR has revised its system of appeals, to a more swift one, concerns regarding that have already been brought up by Profit magazine.

A macro impact, as pointed out by experts, is the reliance on rental value and location for tax assessments. It might distort market dynamics, as businesses in prime locations could face disproportionately high tax burdens regardless of their actual profitability. This leads to another problem of retailers seeking to underreport their rental values or shifting their business activities to avoid high indicative income assessments, leading to inefficiencies in the market.

While the concept of indicative income under the Tajir Dost Scheme aims to simplify tax compliance and increase revenue collection, it raises several concerns regarding accuracy, fairness, transparency, and impact on small businesses.

The FBR seems to have made their job easier by introducing these provisions but that is about all they achieve. The potential for arbitrary assessments and lack of individual consideration could undermine trust in the tax system and hinder the scheme’s effectiveness. To address these issues, it is crucial for the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) to ensure transparency, provide clear guidelines, and establish robust mechanisms for appeals and reviews to foster trust and compliance among retailers.

Will the FBR do that? Evidence suggests that status quo is not often changed at the board, and defaulters mostly find a way to reinvent their wheel of non-compliance. The only way forward, as suggested by experts, is formalising the informal sector of the economy.

Now one could view the current form of TDS, as a way of formalising this sector before coming down on them with more righteous measures like sales taxes, but the scepticism in the Board’s ability to do so is not unjustified. n

A

The startup sector has seen a $ 6 million surge in one month after raising only $1 million in the first six-months. Is it a blip or something more?

By Nisma Riaz