08 24

08 24

08 In Pakistan, the platform economy’s labour problem is as strong as ever

13 Making a killing: Who are the highest paid executives in Pakistan and are they worth the hype?

15 This company is about to get a licence to buy local gas to sell to corporations privately. Not everyone is happy

18 PSO wants a loan-to-equity swap against its debt. How well thought out is the plan?

24 The economy is in the dumps. What asset classes have stood the test of time?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Pakistan’s platform economy is big, but the realities of gig work in a country without labour protection are often chilling. A new report sheds light on this

By Nisma Riaz

Do you remember waking up to your mother banging your door on a Sunday morning because she wanted you to run down to your neighbourhood store to buy eggs for breakfast? Or begging your brothers to drop you to a friend’s house because you can’t drive yet?

Life of such dependency feels like a lifetime ago, now that you can Pandamart your groceries within an hour, book a safe ride through Careem and even have a waxing lady show up at your doorstep within minutes.

As digital penetration continues to increase country-wide, Pakistanis, previously dependent on others, have started using online platforms and applications to perform daily tasks, such as travelling, grocery shopping, and even getting household work such as plumbing. The service industry of Pakistan has drastically changed since.

However, despite how easy the platform service industry has made our lives, it is not that same for those who provide these services. The platform economy in Pakistan is not

only a highly unregulated one, but also quite exploitative.

Profit explores the many problems platform and gig workers in the country face. And potential lessons we can learn from other industries around the world, to make ours a more sustainable and humane one.

Pakistan ranks third globally in the online gig work industry, following India and Bangladesh, with about 12% of the market share according to Oxford University’s Online Labour Index. The Pakistan Freelancers Association estimates around one million IT-related freelancers in the country. Additionally, desk research suggests at least 700,000 individuals work in location-based platform services like ride-hailing, professional services, and delivery.

Despite a booming industry, the platform economy faces significant challenges. The number of digital labour platforms has decreased recently, leading to monopolistic

conditions in sectors like food delivery and ride-hailing. Pakistan’s economy is under severe strain with high inflation (around 38%), a large informal economy (over 80%), and increasing youth unemployment (around 30%). This environment is pushing platform workers to either leave their jobs or accumulate debts due to negative incomes.

An example of this is the four-day internet shutdown in May 2023, which affected over a million platform workers across the country.

Research by the Centre for Labour Research, involving around 300 interviews with ride-hailing and delivery workers, highlights several issues that platform workers in Pakistan battle with daily. Workers are often unaware of their contractual terms, as many are registered by platform representatives without clear information. Many workers exceed legal working hours, with over 50% working more than 12 hours per day and 75 hours per week, far beyond the legal limits of eight hours per day and 48 hours per week. So, while platforms promise flexibility, the reality is often excessive working hours and a lack of traditional employment benefits leaving work-

ers exploited in more ways than one.

The flexibility of platform work often leads to extended hours due to financial pressures. This results in significant physical and mental health issues, eroding work-life balance and leading to burnout. Despite working over 48 hours a week, many platform workers face financial hardships. Only 10% earn above the living wage, and only 20% earn more than the minimum wage. The phenomenon of negative income, where workers’ costs exceed their earnings, traps them in a cycle of debt, reflecting poorly on both the economy and worker rights, making the platform economy of Pakistan a toxic one for those who uphold it.

The most common feature of exploitation is lack of awareness. When workers are unaware of their own legal rights, it becomes much easier for them to fall prey to below minimum working standards and for platform companies to manipulate them. Although some platforms offer accidental insurance, most workers lack awareness and coverage, leaving them vulnerable. This gap in protection highlights the need for better transparency and proactive measures to ensure worker safety and rights. Platform workers appreciate the autonomy but desire access to basic workplace rights, such as regulated working hours, social protection, sick leave, and paid annual leave, however, they struggle to demand these rights. National employment legislation does not protect them, exacerbating their precarious position.

Research conducted by the Centre for Labour Research shows that Post-COVID-19, the ride-hailing sector was faced with supply-demand imbalances, reduced fare rates, and disappearing driver bonuses. The rise in fuel prices further continues to burden drivers, contributing to negative income situations and reflecting the disturbing interplay of market dynamics and worker livelihoods. Drivers report inaccurate maps causing delays and frustrations, impacting their ratings. Additionally, platforms’ automated disciplinary systems, which can block workers’ IDs based on ratings, are seen as unfair, when failing to factor in external conditions and reasons for poor ratings. While appeals processes exist, the reliance on algorithmic governance remains a widespread concern among these platform workers.

To date, platform economy workers in Pakistan have largely been overlooked by regulatory frameworks, despite significant growth in both

traditional and digital platform-based work.

The legal landscape has struggled to keep pace with this expansion. Although attempts by the governments of Punjab and Sindh in 2017 to restrict ride-hailing platforms focused primarily on competition and corporate law issues, these efforts did not address worker rights directly and were quickly resolved through private negotiations.

It is important to involve those directly affected by the issues that plague this industry, in order to come up with solutions that will actually work. However, unfortunately most gig workers in Pakistan are deliberately or due to regulators’ oversight, are left out of these conversations.

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly’s introduction of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Transportation by Online Ride Hailing Company Bill, 2022 marked Pakistan’s initial legislative effort targeting platform work. This bill seeks to regulate online ride-hailing services, emphasising safety guidelines and general rights for drivers, albeit classifying them as service providers rather than employees.

Pakistan’s Constitution guarantees fundamental rights such as freedom from slavery and fair working conditions, though these provisions lean towards civil and political rights rather than socio-economic protections. As such, supplementary federal statutes cover employment contracts, termination procedures, working hours, paid leave, and wage payment, but are insufficiently applied to platform workers.

Most platform companies in Pakistan classify workers as independent contractors rather than employees, which restricts their access to essential benefits like minimum wage, decent working hours, social security, and collective bargaining rights. Despite legal battles elsewhere, companies like Uber continue to classify drivers similarly in Pakistan, exacerbating the vulnerability of workers in an increasingly dominant market position post-acquisition of Careem.

The concept of “decent work,” as endorsed by international bodies like the ILO and enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals, applies universally but is unevenly implemented in Pakistan’s digital labour platforms. Existing labour laws, such as the Industrial and Commercial Employment (Standing Orders) Ordinance, 1968, and the Punjab Minimum Wages Act, 2019, theoretically encompass platform workers due to their broad definitions of workers and wage regulations.

Efforts to utilise consumer protection laws as a workaround to enforce worker rights have seen limited success, given the primary focus on consumer rights rather than labour protections. However, provincial con-

sumer protection acts could potentially hold platforms accountable for fair wage practices and service disclosures affecting workers. Legal ambiguity persists despite existing laws that could potentially safeguard platform workers, including Acts regulating minimum wages, occupational safety, and protection against harassment. The lack of specific judicial interpretations or cases involving platform workers further complicates the application of these laws.

Looking forward, the approval of the Islamabad Protection of Home-Based Workers Bill suggests a growing recognition of online platform workers and a willingness to extend social security benefits. However, clear and enforceable regulations tailored to the unique dynamics of platform work are urgently needed to protect the rights and welfare of Pakistan’s burgeoning digital workforce.

The regulation of platform economies is a complex, evolving challenge faced by national legislatures and courts worldwide. However, there are examples of some diverse policies and legal approaches that offer valuable insights when taken from a comparative perspective. Even though these initiatives are not ideal, having several loopholes, they are a step towards achieving a better future for platform workers.

In the UK, courts have played a crucial role in safeguarding platform workers’ employment rights. The judiciary has expanded the interpretation of existing employment laws to include many platform workers under social security protections. Notably, Section 230(3)(b) of the Employment Rights Act defines a ‘worker’ broadly, encompassing those under any work contract that isn’t explicitly an employment contract. Significant cases, like Pimlico Plumbers and the 2021 Supreme Court ruling on Uber, have underscored that the practical realities of the worker-platform relationship warrant protection under employment legislation. These legal decisions grant platform workers essential rights such as minimum wage, rest breaks, and protection against unlawful deductions.

However, litigation alone is insufficient for industry-wide reform. It often benefits individual litigants without compelling companies to alter contracts for all workers. Additionally, focusing on contractual documents can lead to legal loopholes, prompting calls

for statutory presumptions of worker status to reduce the need for frequent litigation. Effective enforcement and proactive regulation are essential to extend protections broadly and address disparities for self-employed individuals not covered by current laws.

In the US, platform worker status remains contentious, with no unified federal standard. Employee classification, which offers significant protections, varies widely across states and is subject to tests like the Control Test and the Economic Realities Test. These tests focus on factors such as the right to direct tasks and the economic dependencies of workers, but their application is inconsistent and often inconclusive for platform workers.

California’s Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) introduced the “ABC” test to address worker misclassification, aiming to reclassify many independent contractors as employees. However, Proposition 22, a ballot measure passed in 2020, allowed companies like Uber and Lyft to exempt their drivers from AB5, though it faced legal challenges and partial invalidation. The Biden administration’s proposed rules seek to define an “employee” based on economic dependency, but the outcome of these regulations remains to be seen.

The EU has taken steps to regulate platform work through directives like the 2019 Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions, which enhances transparency and predictability for workers in open-ended forms of employment. It includes measures to address ‘bogus self-employment’ and ensures protections for on-demand platform workers. However, it leaves a loophole for purely freelancing or self-employed individuals.

Spain’s “Rider Law,” passed in 2021, presumes employment for delivery workers under digital platforms and mandates transparency in algorithmic management. The European Commission’s proposed Directive on Platform Work, expected to influence member states, aims to clarify employment status and enhance protections for platform workers, including transparency and human oversight in algorithmic decision-making.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has acknowledged the need for an international labour standard for platform work. During the 347th Session of the ILO Governing Body in March 2023, it was decided to discuss this issue at the 113th Session of the International Labour Conference in June 2025. This initiative aims to establish decent working conditions for platform workers globally by 2026, addressing the unique challenges of the platform economy and setting a benchmark for national regulations.

No country has been able to create a platform economy that is completely fair, however, efforts to reduce exploitation and increase labour protection have been made to move towards a fair system. Regulation of the platform economy is a burgeoning area worldwide, offering valuable examples that could inspire reforms in Pakistan.

In China, the Ministry of Human Resource and Social Security issued guidelines in 2021, introducing a concept of “less-thancomplete employment relationships” to extend minimum wage rights to platform workers. Indonesia’s BPJS allows self-registration for work injury benefits, accessible to platform workers. India’s Social Security Code, pending implementation, mandates platform contributions to provide various benefits. Rajasthan’s 2023 bill establishes a welfare board for gig workers, mirroring South Korea’s 2020 amendments granting insurance benefits to platform workers. Chile and Colombia are making strides with legislation requiring employment contracts and social security for platform workers, while South Africa extends anti-discrimination laws. The Philippines’ POWERR Act seeks to classify gig workers as regular employees. Brazil mandates COVID protections and accident insurance, Uruguay allows digital social security contributions, and Spain enacted the Rider Law for delivery worker protections. New York set minimum pay standards for food delivery riders, and the EU proposed a directive enhancing algorithmic transparency and employment presumptions.

In the UK, Uber drivers gained worker status in 2021, entitling them to minimum wage and benefits. Italy and France have enforced sectoral agreements and social responsibility for platform workers, respectively, while Greece established trade union rights and contract transparency. These global initiatives showcase diverse approaches to regulating platform work, offering a spectrum of strategies Pakistan could adapt to protect its growing gig economy workforce.

In order to empower platform workers in Pakistan, it is necessary to make their digital ratings portable, allowing them to demonstrate career progression and

utilise new opportunities. Proper licensing and tax enforcement for foreign companies like Uber and Careem are essential to prevent exploitation and ensure fair market practices. Legislative reforms should offer all workers a minimum safety-net of social protection, including insurance for accidents, injury, sickness, and redundancy, most of which are offered by Careem but neglected by others. This could involve creating a benefits fund to distribute social security burdens across platforms.

There is a pressing need for regulators to utilise the same data-driven technologies as platforms to ensure efficient and precise regulation. One proposition to counter this issue is collaboration between platforms and regulators, incentivized by lower taxes, which can help maintain economic progress while enforcing fair practices. Another issue is the lack of collective bargaining rights and unionisation, which could give platform workers a voice and strengthen their position in negotiations and litigation in Pakistan.

Effective enforcement agencies are crucial to implementing reforms. The government should empower institutions like the Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource Development to create and enforce a national plan of action, supported by provincial labour departments. Strict fines for companies evading laws can reduce the need for complex litigation. Developing adaptive regulatory frameworks requires robust consultations with platforms and workers to understand their needs and conditions, ensuring comprehensive and effective regulations.

To address the adaptation challenges of platform work, it is essential for Pakistan to form committees and technical working groups comprising platform workers and stakeholders. These groups should develop tailored policies for specific sectors. Governments can experiment with regulatory sandboxes to test different approaches and determine appropriate employment classifications for platform workers. Enhancing institutional capacities and social protection measures will create adaptive and inclusive regulatory frameworks that safeguard workers’ well-being.

Pakistan currently lacks specific legislation for platform work, leading to the misclassification of workers as independent contractors and depriving them of labour law protections. Therefore, standalone legislation is necessary for effective regulation. The Centre for Labour Research, in collaboration with the Wageindicator Foundation and Fairwork, has proposed the Platform Workers Protection Bill 2023 to protect platform workers’ rights. The bill defines key terms and establishes criteria for determining an employer. n

Silently and almost in obscurity, Premier Villas has become popular in a location where the real estate market seemed dead. Here’s how it happened

By Shahab Omer

Astrange sight is emerging in a small corner of Lahore. In the area of Lahore’s Walton Cantonment Board, where development work has ground to a halt, roads languish broken and neglected, cleanliness is a daily challenge, and encroachments are a common sight, an unusual development has taken place.

Right off main Walton Road is Premier Villas. The little gated society bordering Defence Housing Authority’s (DHA) Phase 1 has quietly and swiftly come alive. The area in which the housing society exists is not particularly big. In fact, most of the plots being sold (and yes, plots are being

Quietly and swiftly, a housing society has sprung up on a small piece of land bordering the Defence Housing Authority (DHA). Despite the surrounding chaos, plot buying and selling have already begun, and the society is selling plots ranging from 3 to 10 marlas at rates of Rs 20-22 lakhs per marla. How is this little parcel of land developing so quickly in an area of the city where land disputes and confusions have caused real estate development to slow down to all but a stop?

The reason is Seth Abid.

Premier Villas is being marketed and sold by dealers as a project of the legendary

gold smuggler and Lahori property developer. And despite the fact that Seth had passed away more than three years ago in January 2021, his name carries enough weight that the society is selling plots. But who is behind it? After all, Seth Abid’s family is scattered after a series of tragic events. Premier Villas was a plan he had made a long time ago. Who is carrying it out now? It would seem that enterprising middleman and land managers are behind the project which is running with complete freedom.

Seth Abid was once one of the richest men in the country, and rumoured to at one point be the single largest real estate property owner in Pakistan. But in the years following his death, his legacy seems to have fractured.

This publication has covered the late Seth in great detail on multiple occasions. Taking his start from a small trading family that migrated from India, Seth Abid got his start smuggling gold across Kasur from India and selling it in Lahore and Karachi. He eventually began smuggling from the Middle East through sea routes and eventually shifted his attention towards the property business, parking a lot of his money in major projects such as Eden Gardens and Eden Villas in Lahore.

Much of the land he acquired was around the region that is now DHA. As such, his property was valued highly and he ran many projects that were quite successful. He developed most of his land in his lifetime, but there are still significant parcels of it remaining.

The problem has been there was no clear heir to Seth Abid’s fortune upon his death. Sure, his family inherited his wealth but no single person emerged as a contender to take the place of Seth as head of the family and run the show. For many years Seth had been grooming his eldest son, Seth Ayaz Ahmed, to take over the family business. When he was gunned down in 2006, Seth Abid withdrew from public life and his business activities also slowed down. For a while it seemed his daughter Farha and her husband, Mazhar Rafiq, would be the successors. But in 2017, Mazhar Rafiq fled the country pending a NAB investigation after swindling a large number of people out of their savings. Five years later, Farha would be killed by her own son in a family dispute.

Which is why after his death, internal sources have informed Profit that most of Seth Abid’s land remains in the hands of his administrators. This lingering control over his properties adds a layer of complexity to his legacy, intertwining his name with both the opulence of his achievements and the unresolved affairs that continue to unfold.

This story takes us back to the days when Lahore’s DHA was in its early stages of development. The surrounding areas were lush with villages and greenlands, a stark contrast to the urban sprawl we see today. This area, now known as Super Town and Rifle Range Road, was once famously called Korey Pind. Even now, the revenue records list this area as Mouza Kora.

In those days, there was a route that led into this area before one could enter DHA. Developers saw an opportunity here. They realised that this land, being so close to DHA, and easily accessible from Walton Road and DHA’s main boulevard, had great potential. They believed that selling land and starting housing projects in this vicinity would be relatively easy.

In this area, Eden Developers made their mark by establishing a housing society named Eden Cottages. They built two phases in the area once known as Kora Pind. However, what began as a promising venture soon turned controversial. According to records from the Mouza Koraa Patwari’s office, much of the land Eden Cottages occupied actually belonged to the Punjab Liquidation Board.

Eden Developers, in collusion with Patwaris and government officials, included this land in their housing project and sold it illegally. As is often the case, the higher authorities of the Liquidation Board only realised the gravity of the situation when it was too late, and they hurriedly obtained a stay order to halt further sales.

But by then, the damage was done. The land belonging to the Liquidation Board had already been sold. Among the plots on which Eden Cottages was built, about eleven Khasras

were claimed to be owned by the Liquidation Board. Even today, transactions in this area are conducted through stamp papers, with no official Fard e Bai (land document issued by patwari for the sale of land by original owner) issued by the Patwari. This lack of legal documentation has resulted in significantly lower property prices in this area compared to its surroundings. While a ten-marla house in a non-disputed part of the area might cost around 30 million rupees, a similar house in Eden Cottages could be bought for half that price.

leaving the land in limbo. Consequently, the land remains empty, serving as a grazing ground for locals’ buffaloes, sheep, and goats.

Seth Abid also made a bold move by purchasing a large tract of land in this area. His intentions, known only to him, seemed promising, but the advice he received before acquiring the land appeared flawed in hindsight. Undeterred, Seth Abid launched an ambitious housing project named Fort Villas. The first phase saw the construction of over two hundred homes of varying sizes, but the second phase never materialised. Instead, the land for Phase II remains vacant to this day.

The undeveloped land for Fort Villas Phase II is strategically connected to DHA, sparking rumors that DHA intended to buy this empty piece of land. This speculation perhaps explains why no further development was undertaken. Instead, the area was enclosed with a boundary wall and gate, left untouched. According to the Property agents of this area, this vacant land spans over fifty acres.

There were also speculations in the market that during Seth Abid’s lifetime, the Fort Villas administration sought to secure an access route through DHA for the second phase. However, DHA’s administration refused to grant passage through their blocks or roads,

In the midst of all the speculation, a few DHA officials, who requested anonymity, confirmed a long-standing rumour. They confirmed that Fort Villas’ management had indeed hoped to secure an access route through DHA’s W Block. However, the layout of W Block was meticulously designed to prevent any new pathways. If approximately a hundred homes were built on Fort Villas’ undeveloped land, and their residents began using the W Block route, it would create significant inconvenience for DHA residents.

Furthermore, these officials dismissed the market rumours that DHA intended to purchase the land or that there was any pressure on Fort Villas’ management from DHA regarding its acquisition. They explained that DHA had completed this phase a long time ago and had since moved on to new projects in different locations. The idea of buying such land to start a project with no clear structure or plan made no sense to them.

As the officials put it, DHA was focused on future developments, leaving the unresolved past of Fort Villas’ land in the shadows, with no intentions of revisiting it.

However, during that era (in the life of Seth Abid), when land prices were remarkably low and Seth Abid had ample financial resourc-

es, he decided to acquire another large tract of land near the Fort Villas project. It seemed like a promising investment at the time, given the affordability and potential for development. However, this purchase proved to be less than wise. The crux of the issue lay in the main access route to this new piece of land. As per some officials of Patwar Khana, the only way to reach it was through a narrow bazaar adjacent to Walton Road. While vehicles could navigate this bazaar, they often did so with great difficulty. The narrow passage and the increasing congestion due to the rising population made the route far from ideal.

As a result, this access route became a significant drawback. The narrow, crowded bazaar did not offer the kind of appeal needed to attract buyers willing to pay a premium for plots on this land. Despite Seth Abid’s vision and financial clout, the challenging access and lack of allure meant that this piece of land failed to achieve the desired success. This is why the land has remained undeveloped for over three decades.

The trouble began when efforts were made to develop a housing society called Premier Villas on the land and put it up for sale. According to a local resident, the real problem started when a portion of the boundary wall of Eden Cottages was broken down to create an access route. The administration of Premier Villas then stationed their private security guards at this newly created entrance, effectively taking over the route by force. This new access point wasn’t a main road but merely a narrow street lined with houses.

The same resident told Profit, the administrative matters of Eden Cottages have historically been managed by a committee of local residents. Some years ago, during the lifetime of Seth Abid, a station commander approached the committee with a bold request. He wanted a portion of the boundary wall to be broken down to create an access route to a piece of land owned by Seth Abid.

The committee members were taken aback and strongly resisted the idea. They informed the station commander that the boundary wall had been constructed by the Walton Cantonment Board (WCB), making it untouchable by anyone. Despite the pressure, they stood their ground.

During this tense period, Seth Abid’s administration, through WCB officials, tried to sweeten the deal. They offered to repair and maintain the roads and improve the sewage system, ensuring a smoother living experience for the residents of Eden Cottages. It seemed like a fair trade, but the committee remained firm.

The residents of the street where the boundary wall would be breached had their own condition: they demanded two million

rupees each as compensation. This was a price Seth Abid’s administration was unwilling to pay. The standoff resulted in a stalemate. The proposed deal fell through, and the ambitious plans to create an access route were shelved, leaving the boundary wall intact.

When inquiries were made to the WCB regarding the situation, the relevant officers proved evasive. They hid behind the guidelines of the Ministry of Defense, repeatedly claiming they were not authorised to provide any information. However, after persistent questioning, one officer agreed to share some details on the condition of anonymity.

According to this officer, the Walton Cantonment Board never constructed the boundary wall of Eden Cottages, nor were they aware of any deals involving it. Eden Cottages is a private society responsible for its own boundary wall. They built it themselves, and any decision to provide an access route was made solely by Eden Cottages’ administration.

Another officer shed more light on the situation, revealing that the current chairman of the Eden Cottages committee had granted the permission. There must have been terms agreed upon by both parties for this arrangement to proceed. Without the chairman’s consent, the Premier Villas administration would never have been able to secure an access route through Eden Cottages.

The current chairman of the Eden Cottages committee is Yasir Khan Niazi, whose father also served as the committee chairman during his lifetime. However, some residents of Eden Cottages claimed that the current chairman is self-appointed, having taken the position forcibly without any elections.

Though Seth Abid is no longer with us, who is developing a housing society on his land? To uncover the details, Profit visited the sales office of this new development, situated right on the same land. A sales representative explained that the project was progressing swiftly.

“Only a few plots are left,” she said, “as many have already been sold or booked.”

Premier Villas, the name of this new housing society, boasts nearly 200 plots of various sizes. They are being sold at prices ranging from 2.2 million to 2.5 million rupees per marla. Beyond the residential plots, the society also plans for a park, a commercial plaza, and a mosque, aiming to create a self-sufficient community.

Curious about the access routes to these plots, Profit inquired further. The sales representative clarified, “The primary access route is from Walton Road. However, there will be two additional routes through Eden Cottages. One of these routes is already in place, and the

second one is expected to be completed in the coming days.”

The promotional brochure for the society shows that both access routes are connected to the boundary wall of Eden Cottages. One access route had already been carved out by breaking through the boundary wall on Street 2 of Eden Cottages. The second route was planned to cut through Street 7, similarly linked to the same boundary wall.

What struck observers as particularly intriguing was the silence surrounding the transactions. Sales were being conducted with remarkable quietude. The promotional material did not name any developers, nor did it provide a website that might offer clues about who was behind the project.

Digging deeper, it was revealed by the same sales representative that the project was a collaborative effort. One of Seth Abid’s daughters and a private developer were selling the plots. The developer, a company named South Bay, had teamed up with BDL Company, which was represented by Seth Abid’s family, to bring this project to life.

Adding another layer to the tale, the brochure listed the location as Abid Hussain Road, Walton Road. Yet, the map inside showed two access routes through Eden Cottages in addition to the main Abid Hussain Road. The sales representative also proudly mentioned that Premier Villas had received approval from the Walton Cantonment Board. The Walton Board officials remained tight-lipped about the situation, reluctant to provide clear answers. It was only after persistent questioning that one official, under the condition of anonymity, gave a rather evasive response. He explained that only societies registered under the Society Act are considered approved, meaning their layout plans and locations are formally sanctioned. However, if someone decides to plot their private land and sell the plots, there isn’t much the Walton Board can do. They can name their scheme anything they want. The official’s response left the registration status of the new society ambiguous.

This ambiguity, some in the property market argue, often misleads buyers into making poor decisions. They believe the Walton Board should clearly indicate the legal status of such projects on its official website. Instead, many illegal projects are openly marketed on Walton Board’s commercial sites through billboards and flex signs.

Although the land in question belongs to Seth Abid, none of his family members have publicly confirmed that they are selling it. This lack of transparency adds another layer of mystery. Interestingly, even many local property dealers are unaware of the buying and selling activities surrounding this land. n

This company is about to get a licence to buy local gas to sell to corporations privately.

EGas collects natural gas produced during oil extraction and transports it in special trucks to bridge gas demand. But what is the controversy behind their renewed licence?

NBy Ahmad Ahmadani

ormally, Pakistan’s Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (OGRA) renewing a company’s licence is not a particularly notable event. But it seems the licence renewal of EGas Private Ltd is becoming a bit of a bone of contention.

Founded in 2010, EGas is a virtual pipeline company. Their business model is to collect, transport, and sell natural gas that would otherwise be wasted in the process of oil extraction. Since its

inception, the company has been operating in the Kabir and Dhok Sultan gas fields, leased by the government to energy exploration and production company Pakistan Petroleum Limited (PPL), and are on the verge of having their licence (which expired after the Covid-19 pandemic) renewed.

But the opposition to this licence renewal was recently brought up in a public hearing of OGRA, where a claim was put forward that Petroleum Division was unduly favouring EGas, pointing towards a history of payment defaults and working unlicensed based on unauthentic letter on the part of EGas that should, according to these critics, make renewing EGas’ licence a problem.

EGas denies these claims, attributing financial discrepancies to the unprecedented disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these challenges, EGas says it remains committed to fulfilling its financial obligations and resuming normal operations. The ongoing application for a new licence is seen as a crucial step towards stabilising the company’s operations and continuing its contributions to Pakistan’s energy sector.

EGas was established in 2010 to address the issue of flaring natural gas at various oil fields. When oil is extracted from oilfields, natural gas is also released in the process. Oil companies are there to get their hands on, process, and transport oil. Ideally, they would also be able to collect and transport the gas, but this often proves to be cost ineffective.

The infrastructure needed to transport

the gas — pipelines — is either too distant or the volume and pressure of the gas are insufficient to justify the expense of a pipeline.

So what happens to the natural gas that is released? Well, if you’ve seen images from an oilfield of massive oil rigs and drills, you might have noticed there are massive chimney like structures in the background that periodically release huge flashes of fire.

The process of gas flaring is horrible for the environment, with a recent NPR report suggesting it actually releases five times the methane emissions originally calculated. It is also a waste of a scarce natural resource, especially in a country like Pakistan where there is a shortage of natural gas. Historically, companies extracting oil from wells, such as the Oil and Gas Development Company Limited (OGDCL) and Pakistan Petroleum Limited, have resorted to flaring due to logistical challenges associated with setting up a pipeline to transport such gas.

That is where EGas comes in. Recognizing the environmental and economic inefficiencies of this practice, EGas approached OGDCL in 2010, offering a solution: EGAS proposed purchasing the gas that was being flared, thereby reducing waste and emissions, and helping overcome gas shortages in the country. It is the Plains Bison approach: For the most efficient use of resources, you can’t discard anything and must find a use for it. EGas had found a similar model implemented in Italy.

Pakistan has been grappling with a severe gas shortage for several years, which has had significant implications for both domestic and industrial consumers. The shortfall in natural gas supply has led to frequent load

shedding, forcing households to turn to alternative and often more expensive sources of energy for cooking and heating. The industrial sector, particularly the textile industry which is a major contributor to Pakistan’s economy, has also been heavily impacted. Many factories have had to reduce their operating hours or shut down entirely due to the lack of reliable gas supply, leading to loss of productivity and economic output.

For example, in the winter of 2022-2023, Pakistan experienced one of its worst gas crises in recent history. The government was unable to secure sufficient liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargoes, which are crucial for meeting the country’s energy demands during the colder months. As a result, domestic consumers faced prolonged gas outages, and industries reported significant production losses. This recurring problem has underscored the urgent need for innovative solutions to bridge the supply-demand gap.

To implement its solution, EGas imported specialised trucks and created a business model around transporting the gas which would otherwise be wasted through flaring. They developed trucks equipped to clean, dehydrate, and compress the gas, making it suitable for transport. These specialised trucks then delivered the gas to EGas-owned CNG stations and private buyers like Kohinoor Textile Mills. The success of this model attracted other oil and gas companies, including Mari Petroleum, to partner with EGas. This innovative approach not only maximises resource utilisation, but also contributes to environmental sustainability by significantly reducing flaring.

Over time, EGas has worked on six to seven fields using this approach, all under a licence from OGRA. However, these fields, being relatively small, have a finite lifespan and eventually deplete. Before COVID hit, EGas signed up two more fields, Kabir Oil Field in Sangar and Dhok Sultan Oil Field, both operated by energy producer Pakistan Petroleum Limited for which they were going to buy the gas from these oil fields under a licence. But a mix of unfortunate happenings including the Covid-19 disaster which upended production and a fallout with its partner PPL led to EGas’ old licence becoming obsolete. Now, they have been asked to get a new licence which will most likely be granted to them but it is going to come with some unhappy faces.

EGas is currently facing allegations that it is being unfairly favoured by OGRA, the regulatory authority, which is poised to grant the company a new licence. How is it being favoured? Because it

has allegedly been a payment defaulter of PPL in the past and has operated without a licence in its arrangement with PPL to purchase gas from Kabir Oil Field. These allegations were levelled in a public hearing by OGRA, which conducts these hearings to ensure that no one’s rights are infringed during the licence awarding process.

OGRA conducted this hearing regarding EGas’ licence on June 24 during which grievances were aired that EGas had previously operated without a licence and had also been a payment defaulter of PPL, defaulting on Rs 33 crores owed to Pakistan Petroleum. EGas says it never defaulted on any payment and rather technicalities in contracts that were four years old were being misrepresented by a competitor, Ghiyas Paracha, the chairman of All Pakistan CNG Association and founder and CEO of Universal Gas Distribution Company, to damage EGas’ reputation and eventually stall the licence awarding process. EGas also says that the permission to work without the licence was granted in the interim by OGRA on the request of PPL, while its licence request was being processed. The said licence was eventually presented to PPL.

How had the events unfolded? Matters date back to 2020 when EGas first received its licence to purchase gas from PPL from Kabir Oil Field. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, EGas had successfully obtained a licence from OGRA for the Kabir Oil Field. But before it could completely secure a licence, it was allowed to transact with PPL and purchase gas while its licence was being processed. As per Hassan Raza, a director at EGas, PPL had directly requested OGRA to allow sale of gas to EGas even though EGas’ licence was being processed and was not issued yet. PPL weighed that while the licence was being processed, gas was going to be wasted if EGas could not buy it because its licence was not there yet, which would have led to a revenue loss for PPL.

That request went to OGRA from PPL and in response, OGRA issued two letters pertaining to each field, allowing PPL to start selling gas to EGas from Kabir Oil Field as well as Dhok Sultan Oil Field. Documents from that time available with Profit show that one of the letters turned out to be unauthentic. Allegedly, the person whose signature was on the documents said that he had signed one but not the other. It was the document pertaining to PPL starting to sell to EGas at Kabir Oil Field which turned out to be unauthentic, received by PPL in the mid of March 2020.

EGas says that they were allowed to transact with PPL for both fields on an interim basis as per OGRA’s permission, and if a document in that regard

turned out to be unauthentic, it wasn’t done by EGas and was a matter between OGRA and PPL. EGas says that when it got the licence, it presented that to PPL. Documents available with Profit show that EGas received the licence to purchase gas from Kabir Oil Field in May 2021.

Soon after, the pandemic led to a shutdown of everything including the fields. The Covid-19 disruption came with contractual problems compounded by the “take or pay” agreements in place, which obligated EGas to pay for the gas regardless of whether it could be sold in the market or not because of the lockdowns.

In face of the situation where lockdowns meant EGas could not sell gas, EGas invoked the force majeure clause in its contracts, a legal provision that frees both parties from liability or obligation when an extraordinary event or circumstance beyond their control prevents one or both parties from fulfilling their obligations. This move was essential for EGas, as it legally suspended their payment obligations due to the unforeseeable and uncontrollable global crisis. But EGas owed a big amount to PPL for the time it was working with, leading to a creation of Rs 33 crores in receivables from EGas to PPL. PPL even took EGas to court to recover this amount and asked the court to even liquidate the company for recovery of what it owed to PPL. The receivables that were stuck formed the basis of complaints during the OGRA hearing that EGas had defaulted on this amount, when in fact EGas settled this amount through bank guarantee and cash payments in April of 2024.

EGas emphasises that the financial receivables created during the lockdown were a direct result of these unprecedented conditions and were not due to any financial mismanagement or default on their part.

When the lockdowns were lifted, and operations began to resume, PPL requested EGas to obtain a new licence to continue purchasing gas and settle the amounts that it owed to PPL. Documents available with Profit show that EGas settled the amount via cash payments and bank guarantee in May 2024.

“The amount that was payable to PPL was settled out of court following mutual understanding of both parties to do so,” says Hassan Raza, who runs EGas.

EGas has reiterated its commitment to fulfilling its financial obligations and has taken steps to secure the necessary guarantees and payments as directed by the Ministry of Petroleum. The company maintains that its efforts to clear outstanding dues through direct payments and bank guarantees demonstrate its reliability and commitment to resuming normal operations. The current application for a new licence is part of this effort to normalise

“The amount that was payable to PPL was settled out of court following mutual understanding of both parties to do so”

Hassan Raza, EGas

operations and contribute to the energy sector, not an attempt to receive undue favour from OGRA.

The settlement was carried out pursuant to permission of the Petroleum Division granted in January this year to Pakistan Petroleum Limited to reallocate gas from Kabir gas field to EGas, allowing it a quota of 1mmcfd.

The approval is contingent on several conditions which includes PPL ensuring that the sale and purchase transaction with EGas is free from any legal encumbrances and that all necessary due diligence is conducted to ensure the commercial prudence of the transaction. Furthermore, EGas must obtain a licence for the sale of gas from OGRA, and the existing Gas Sale and Purchase Agreement (GSPA) between PPL and EGas must be amended to reflect the revised terms and conditions. Lastly, PPL must seek approval from its Board on these conditions before proceeding further, considering the legacy issues and PPL’s commercial stake in the transaction.

Separately, EGas Private Limited had applied for a new licence to sell flared gas from Kabir Oil Field which they are expected to get now.

Interestingly, during the hearing, a concern that was raised was that Rafhan Maize Products Co. Ltd, which EGas said was its gas customer, was not a customer of EGas. Hassan Raza agrees that Rafhan Maize is not a customer because there can’t be an agreement with Rafhan Maize until there is a licence. So technically they are not a customer yet. However, they do have a Letter of Intent (LoI) signed with Rafhan Maize Products to commence sale and purchase of gas once EGas receives its licence from OGRA.

Further, MOL Pakistan, an oil Exploration & Production (E&P) firm operating in Pakistan since 1999, also raised concerns over granting a licence to EGas, stating that EGas was their defaulter and had not cleared its dues. Hassan Raza said that the matter with MOL Pakistan was subjudice and OGRA officials during the hearing also told representatives from MOL Pakistan that if the matter was in the court, the public hearing was not the right forum to discuss it. n

PSO wants a loan-to-equity swap against its debt.

How well outthought is the plan?

With circular debt ballooning out of control, out of the box thinking is being used to address it. Sadly, it won’t work.

By Zain Naeem

Circular debt. It’s one of those terms everyone seems to use when talking about problems in Pakistan’s energy sector, and there aren’t a lot of solutions out there. The roots of the problem can be traced back to the way energy is provided in the country which has only compounded the problem further. The issue needs to be addressed with targeted reforms that need to be put into place. With a lack of initiative and political will, no such reforms are being implemented.

With the issue of circular debt so deep, there was an interesting idea pitched recently from within Pakistan State Oil (PSO), regarding how they could manage their rising circular debt problem. Of course, PSO managing its circular debt would just be one part of the puzzle, but it is worth looking at the proposition. The suggestion is for PSO to swap its debt for equity. Essentially, PSO wants to pass off its debt to another company and offer that company shares in return. Easy peasy, right?

Not quite. While it is an idea (we’ll give it that), it would be like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic while the country is careening towards the iceberg. Profit takes a look at what exactly is the proposed solution that is being promoted, and could it be effective?

The energy supply chain in the country is mostly controlled or operated in some capacity by the government. The government and its entities aVre the buyers of gas and electricity in the country. They are also the ones who are responsible for setting the prices for electricity and gas. The electricity prices in particular are charged on a cost-plus basis which means that the end price of the utility is charged once the cost has been accounted for. This means that the pricing mechanism is not grounded in economic reality or economic use. This is also prevalent in the gas provision and gas pricing as well. What ends up happening is that electricity and gas is sold at a fraction of the cost it should be selling it.

The price being charged for the two utilities ends up being much lower than the one that needs to be charged. The govern-

ment rationalizes this behavior by providing a subsidy and debt which is able to fill some of the gap that exists between the cost of providing the services and the cost charged to the consumer.

In simple terms, the government keeps kicking the proverbial can and debt down the road and the circular debt keeps accumulating. The nominal impact of this debt is that entities end up owing each other and as the payments are not being settled, the debts keep increasing over time.

In normal circumstances, the debts would be paid off in time and the company would be able to generate the necessary cash flow in order to meet their operational needs. As the receivables are not paid off, the companies have to experience bloated receivables while they end up funding their own operations through bank loans and borrowings. The rotting impact of the circular debt then extends into the banking sector and private credit market of the country as well as these funds are being taken with little scope of these being returned in the near future. The private debt market gets crowded out as well as the private sector has lessened access to these funds.

The caretaker government wanted to decrease some of the impact of the circular debt by injecting funds from one end of the debt cycle which would pass through the whole system and would be funneled back to the government in some form. The basics of the measure would have been that Rs 710 billion would be given to the power production companies who would end up paying their debt to the gas distribution companies which would then make their way to exploration and production companies in the end.

Some of the leading exploration and production companies are Oil & Gas Development Company and Pakistan Petroleum which are listed on the stock exchange and who have a huge chunk of their shareholding held by the government. As these companies would get some of their receivables, they would announce dividends which would make their way back to the government’s coffers. The government would also earn revenues in the form of tax that would be charged on the dividend income.

Due to the complications in the deal, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) rejected this measure and stated that funds could not be utilized in this manner. In essence, this was a short term solution that was being put

into place where a far reaching and impacting solution was required. These far reaching solutions are dime a dozen and need political will and ambition in order to be put into place. With a government looking to keep all stakeholders, there is little that can be expected in the near future.

So what else could be done?

Pakistan State Oil (PSO) is one of the companies that is on the frontline and facing this crisis head on. In recent years, the company has faced growing receivables on its balance sheets which are not being paid off. From 2007 till now, PSO has seen its sales revenue grow from Rs 411 billion to Rs 3.6 trillion in 2023. As the sales increased by more than 9 folds, it is obvious to expect that the company would see its trade receivables to increase as well. The magnitude of the increase is the shocking part. The trade debts of the company went from Rs 13 billion in 2007 to Rs 505 billion in 2023. This shows an increase of more than 37 times. As sales are high and receivables are low, there is a gap that is created that needs to be financed by short term borrowings. Short term borrowings were only Rs 9 billion in 2007 which grew to Rs 452 billion in 2023. The company has been taking more and more debt in order to fund the gap that is created. The company is not able to receive the payments that are due and has to go to the bank in order to finance the gap. The company also uses its creditors in order to finance this gap. Creditors only were around Rs 41 billion for the company in 2007 which increased to Rs 342 by the end of 2023.

This means that PSO is not only suffering from the circular debt but also becomes an active participant in the problem. Companies which are buying from the company are not making the payments due on them to PSO. This causes PSO to not be able to pay its own creditors which only adds to the circular debt problem.

On the face of it, these might seem like just numbers but to give them some context, the company has fixed assets of only Rs 60 billion while its trade debts are around 10 times that. This means that all the infrastructure and fixed assets the company has, the receivables are 10 times more than its fixed assets.

The situation becomes even more alarming when the recent trend in its earnings and share price is seen. The market price of a share is the reaction of the market participants to the fundamental performance of a company. Market price gauges what the buyer is willing to pay for a company based on the performance of the company. One of the biggest indicators of a company’s performance is the price to earning multiple or ratio. Lets say a company is earning Rs 10 on an yearly basis. An investor might be willing to buy this share for Rs 100. The price to earnings multiple becomes 10 as the investor can expect to make back his investment in 10 years if the company keeps performing in the same manner.

Normally, the price to earnings multiple shows how a company is performing and gives a metric by which its performance can be measured against other companies trading and operating in the market. PSO usually trades at a multiple of 5 and in years of low profitability, this ratio increased to around an average of 8. The biggest blip took place in 2022 when the company had a price to earning multiple of 0.94. This meant that the company earned a profit of Rs 184 per share and the market was not even willing to pay Rs 184 for such a share. Imagine investing Rs 184 in a company which is expected to earn the same amount in that one year. The market was not even willing to do that.

How could that be possible?

The market price of a share is a reflection of the perception that the company carries and investors felt that even though the company was earning a healthy amount of profits and revenues, the trade debts were a huge concern. There were chances that the company might never see the recovery of its

trade debts which meant investors were not willing to pay the price that was prevailing in the market.

So it is evident that the receivables are accumulating at an alarming rate and something needs to be done in order to address this issue.

In the face of the deepening crisis, a solution has been proposed by the Managing Director at PSO. Syed Muhammad Taha feels that the receivables of the company can be wiped out by turning the loans to equity. This is what is known as a debt-to-equity swap. So how does it work?

Let’s say there is a person who needs a loan in order to start their business. The person is a friend of mine and in order to help him, I lend him Rs 100. The friend himself

invests Rs 100 of his own. The business is set up and it starts to operate. It is expected that I will get the loaned money back in due time. But rather than being successful, the business starts to make a loss. The friend has no other choice but to invest more money. The friend starts to sell off his personal assets to finance the losses his company is making. In order to keep the business afloat, he invests another Rs 100 in the company bringing his share to Rs 200 in the capital. Seeing the state of affairs, I reach out to my friend and tell him not to worry. Rather than paying me back, he can turn my loan into equity and he can pay me a part of his profits once his company turns a corner.

This is essentially what a loan-to-equity swap is. A loan that was supposed to be returned is turned into part of the equity and the creditor becomes a shareholder in the company. The original investor or owner of the company is willing to give up a share of his company in order to facilitate this. Once my loan is turned into equity, I will become owner of 33% of the company and hence its profits and assets going forward.

Based on the ground reality, this might seem like a good option. In the words of Taha himself, the only viable option that needs to be considered is to settle the circular debt amounts as the government and its entities have little interest in addressing it. The solution was given in May by the MD and has been solidified in the recent corporate briefing of the company. The management of PSO feels that the government can give some of its assets in order to pay off the receivables.

At this juncture, the idea proposed can be seen as having two primary prongs. On one hand, the government can act in a manner where it sells some of its own assets to PSO. The idea is to sell off shares in companies like Oil & Gas Development or give a portion of

projects like the Nandipur or Guddu power plants. As PSO gets ownership in the new government owned projects, they can write off some of the debt against the new assets that they end up acquiring.

Shankar Talreja, Director Research at Topline Securities states that “PSO management has been recommending a share swap with the ideology of getting shares of government owned companies against receivables, however, we have not seen development in this regard. Further, the government is planning to issue a minority stake in the oil and gas sector to GCC(Gulf Cooperation Council) based strategic investors. So, how practical this share swap agreement is, is yet to be seen.” Topline is the company which helped PSO conduct the corporate briefing session for the market recently.

Getting a share in the assets of the government does make sense. The government will be handing over ownership of some of their priced assets to PSO which will address the issue that the company is facing but the problem will still remain that the government will be taking over the debt onto its own books. Plus, the government wants to attract foreign investment into the country so selling some of its best assets to foreign interest will take precedence. The idea has no legs to stand on once the solution is scrutinized to an extent.

So what if one of the biggest debtors of the company looks to use their own shares to pay off this debt?

As of June 2023, the biggest debtor for PSO was Sui North Gas Pipeline

Limited (SNGP). According to estimates, SNGP owes around Rs 500 billion to PSO that it needs to pay back. Even if the interest on its loan is taken away, the company still owes more than Rs 300 billion as part of its debt. What happens in vanilla loan-to-equity swap is that when such a transaction is carried out, both companies have to carry these transactions through their balance sheets. In this case, PSO will end up getting shares which will be an investment that the company holds. As shares are issued, it will increase one of its assets while its receivables fall. The net result would be zero in terms of total assets. On the other hand, SNGP currently shows the debt as part of its liabilities. Once the debt is paid off, its liabilities will fall. In order to make sure the accounting equation still balances, the equity of the company would need to be increased.

Seeing how this will impact SNGP’s balance sheet, the share price of SNGP is Rs 65 right now. In order to pay off most of its principal, the company would need to give 5 billion shares in order to pay off the debt. The problem? SNGP has total outstanding shares of 634 million shares. Out of these, the government owns around 32% of the shares. When the new shares are issued, the government will see its shareholding go from 32% to 3%.

The solution that has been proposed by the MD might seem beneficial to PSO but it is obvious that it will fail to even get off the ground based on the consequences it can have on the shareholding of the government and other shareholders of SNGP. A loan-to-equity swap dictates that new shares need to be issued.

Another solution can be that the government sells all of its shareholding in SNGP to PSO and then the funds raised can be used to pay off the debt as well. In case the government looks to sell off its shares to PSO, it will be able to generate Rs 13 billion from the transaction which is peanuts compared to its total debt. It will only pay off less than 3% of the loan while the problem will still exist and now the government has lost all its shareholding in SNGP.

The circular debt problem is one that needs to be addressed sooner rather than later and any solution which can contribute in the addressing of the problem needs to be considered. However, rather than coming up with fancy and out-of-the-box solutions, there needs to be concrete steps that need to be taken to address the circular debt problem once and for all. These solutions being proposed might seem flashy and attractive but they will prove to be a band aid on a gaping, rotting wound. n

With the economy faltering, what is the best place to park your money? We assess multiple asset classes to unveil the return patterns

By Hamza Aurangzeb

Recent economic headwinds and the latest fiscal budget may have left you feeling anxious or even distressed. However, amidst this turmoil, a surprising development emerged: the Pakistan Stock Exchange became the world’s best-performing bourse in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024.

The benchmark KSE-100 index delivered an impressive 89% annual return in rupee terms during FY24, with an even more remarkable

94% return in dollar terms.

This news might have many scratching their heads, given that the economy was struggling with uncertainty, political instability, and a foreign exchange crisis all these months.

While a detailed timeline of the national bourse’s performance would be interesting, we’ll save that for another time. Instead, we’re more intrigued by a different question: Have stocks consistently been the best-performing asset class in Pakistan, or is there more to the story?

To answer this, Profit presents a primer on the performance of various asset classes over multiple time periods, aiming to determine

which has truly stood the test of time in the country.

Pakistan offers a diverse range of investment opportunities across various asset classes, each with its own distinct features, potential returns, and associated risks. Before delving into the performance analysis, let’s provide a concise overview of the most prominent asset classes available in the country.

If you’re already familiar with these, feel free to skip to the next section.

Equities, traded on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, offer potential for high returns but come with significant volatility. These represent ownership in public companies across 38 sectors, ranging from essential goods with inelastic demand to more volatile sectors. For equity investments, diversification and a long-term approach (minimum five years) are recommended to balance risk and reward.

Fixed income investments provide a more stable option, offering regular payments with lower risk. This category includes government-issued Pakistan Investment Bonds and corporate Term Finance Certificates. These instruments are ideal for investors with a shorter investment horizon of less than five years, providing a steady income stream while preserving capital.

The money market offers highly liquid, short-term investments such as Treasury Bills, typically issued by the government with maturities up to one year. These low-risk options are suitable for risk-averse investors or those looking to park capital for a short period. Both fixed income and money market returns are influenced by the policy rate. Gold presents an interesting investment option, often outperforming during high inflation periods but lacking income generation. It’s suggested as a diversification tool during economic instability, despite its volatility and storage challenges.

Real estate, while potentially lucrative, requires significant capital and is largely dominated by institutional investors. However, retail investors can access this market through more liquid Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).

Lastly, foreign currencies, particularly the US Dollar, are popular due to their liquidity and role in international trade. The dollar’s prominence in global reserves (58.41% as of 2023) makes it a desirable asset for many investors looking to preserve value.

Your investment strategy should be tailored to your individual circumstances and goals. Several key factors influence the most suitable choice of asset classes.

Age plays a significant role in determining risk tolerance. Younger investors generally have a higher capacity for risk, allowing them to consider more volatile assets like equities and gold. As you approach retirement, it’s often prudent to shift towards safer options such as fixed income or money market instruments.

Your investment horizon, or the length of time you plan to remain invested, significantly impacts asset allocation. Longer investment horizons typically allow for riskier asset classes,

as they provide more time to weather market volatility.

Income level often correlates with risk appetite. Higher income generally allows for

performance, we’ve compiled a comprehensive table and accompanying graph that illustrate the average returns for each asset class.

Note: The returns of the 6-month T-bill

greater risk-taking capacity, as you’re better positioned to absorb potential losses.

Your specific investment goals, whether saving for retirement, education, or a major purchase, should guide your asset selection. Longterm goals like retirement may favor equities for their potential growth, while shorter-term goals might be better served by more stable, lower-risk options.

The broader macroeconomic environment plays a crucial role in investment performance. High interest rates may favor fixed income and money market instruments, high inflation periods might make gold more attractive, while low inflation and interest rates often benefit equities.

Now, let’s move to the business end of things. We’ll examine five major asset classes - equities, fixed income/ money market instruments, gold, real estate, and foreign currency - over various time horizons. To provide a clear picture of their

and its reinvestment have been assumed while calculating returns of fixed income. The real estate returns were calculated by assigning weightages to Zameen indices for major cities in proportion to their areas, while the long term CAGR of Real Estate (2011 to 2024) was utilized to estimate the returns from 1999 to 2011. However, before we put our verdict out, it’s important to clarify that this is an analysis of historical data and an assessment based on that, not investment advice.

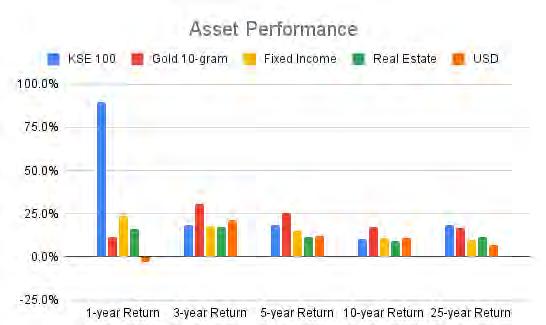

Alook at the performance of these assets over the past one year, and we have a clear winner in equities, having generated a return of 89.8%. While fixed income gave a return of 23.7%, real estate provided a return of 16%, gold produced a return of 11.8% and US dollar generated a return of -2.8%.

The equities have managed to perform quite well over the past one year due to subdued inflation, resurgence of foreign investors, and the stable exchange rate of the Pakistani Rupee.

When examining the performance of various asset classes over the past three years, a contrasting pattern emerges.

Gold stands out as the top performer, delivering an exceptional return of 30.7% per annum, significantly outpacing other investment options. The US Dollar also showed strong performance, yielding a 21.4% annual return, largely due to the substantial depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee during this period.

Fixed income instruments and equities demonstrated nearly identical performance, with returns of 18.2% and 18.3% per annum respectively, highlighting their resilience and attractiveness in Pakistan’s economic climate.

Real estate in Pakistan also proved to be a solid investment, generating a return of approximately 17.6% annually. This period was marked by high inflation and rupee devaluation which played a critical role in the spectacular performance of gold and dollar.

Gold superseded all the other asset classes in the five-year investment horizon as well, it generated a return of 25.2% per annum, equities produced returns of 18.3% per annum, fixed income’s return was recorded at 14.9% per annum, while real estate posted returns of around 11.6% per annum and USD’s return stood at 12.0% per annum.

Once again, high inflation combined with high interest rate environment coerced investors to flock towards gold which resulted in sharp upsurge in its price.

In the ten-year investment horizon, gold’s reign over the top spot continued, it generated a return 17.4% per annum, fixed income managed a return of 11.2% per annum, US Dollar posted a return of 10.9%, equities produced a modest return of 10.2% per annum, while real estate gave a return of 9.5% per

annum. The ongoing fiscal and monetary issues that have resulted in low foreign investment and sluggish growth post-2017 somewhat justify these investment return patterns.

These obstacles which hindered the growth of the Pakistani economy propelled gold to become the best performing asset class in three investment horizons. It serves as a save haven for Pakistanis, who wish to preserve their purchasing power.

The Pakistani equities despite their stellar performance during the past one year are trading at historically low multiples. They have immense potential which could transform them into a juggernaut in the coming years, however, this assertion is contingent upon favorable macroeconomic conditions and political stability.

The historical data of the past twenty five years corroborates the potential of equities in Pakistan, as they outperformed all the other asset classes and generated a return of 18.8% per annum, gold secured the second spot with a return of 16.8% per annum, fixed income fetched 10.1% per annum, real estate posted a return of 11.5% per annum, and the USD generated a return of 7.0% per annum.

The following tables and graphs would give you an idea about the worth of your investment, considering different time horizons. This analysis assumes that you had invested PKR

100,000 at the beginning.

Our comprehensive analysis of Pakistan’s major asset classes reveals that equities are the most suitable option for investors with a longterm horizon of around twenty-five years.

Historical data over this period not only supports this conclusion but also demonstrates that equities have consistently outpaced inflation and outperformed other asset classes.

For these long-term investors, allocating a portion of their portfolio to gold can provide a hedge against high inflation and economic instability, potentially boosting overall returns.

On the other hand, more risk-averse investors, those requiring steady cash flow, or those with short-term investment goals should consider fixed income and money market instruments. These highly liquid investments generally beat inflation and offer the flexibility of redemption at any time.

For investors seeking consistent returns, optimized risk, and maintained liquidity, a balanced portfolio approach is recommended.

This strategy involves allocating capital across equities, fixed income/money market instruments, and gold. The specific allocation to each asset class should be tailored to the investor’s goals and risk tolerance.

Ultimately, the key to successful investing lies in understanding one’s financial objectives, risk appetite, and investment timeline. By aligning these factors with the characteristics of different asset classes, investors can create a robust portfolio designed to weather various economic conditions and achieve their financial goals. n