20 23

20 23

08 In conversation with inDrive’s Daniil Petin

11 Why have MNCs left Pakistan? And what will it take for the Saudis, Chinese and the others to stay? Asif Saad

14 All hail Jazz, the technology company

20 A carbon tax on petrl would appease the IMF, and possibly decimate the salaried classes. Here’s why it may be our best bet

23 From profitable highs to equity injection calls, what went down with U Microfinance Bank in 2023?

27 When it comes to financial inclusion, women and SMEs continue to be the key

29 Babar Azam is the premier brand ambassador for an English sports manufacturer. Here’s why they don’t and can’t sell in Pakistan

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi)

Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

In conversation with

What does Pakistan’s mobility space hold for tech companies, and how does inDrive plan to grow?

In tech circles and between consumers, the conversation usually centers on ride-hailing and how it has been a hit in Pakistan. But inDrive thinks that in logistics, ride-hailing is not the sole end, but also a means to start launching other services with similar potential to ride-hailing. At inDrive, these are referred to as mobility services and include freight, intercity travel, courier delivery and, of course, ride-hailing.

On March 14, inDrive announced that it had secured a $150 million investment to boost its plans to expand within the mobility market.

In Pakistan, the executive overlooking this segment is Daniil Petin, who joined the company as the vice president of mobility in 2022. Daniil is responsible for driving the growth of the company’s mobility services, which include inDrive. Freight, inDrive. Couriers and inDrive.City to City.

Before joining inDrive, Daniil held several executive positions in global tech companies focusing on strategy, business development, growth management, product development and entrepreneurship.

In conversation with Profit, Daniil outlined inDrive’s plans for Pakistan’s mobility space, and what the country holds for segments other than the frequently discussed ride-hailing service.

The potential that Pakistan has in terms of mobility - so, in ride-hailing, last-mile courier delivery, freight, and intercity - is huge. And we are not talking only about 2024 and 2025; the potential is long-term – because if you get into the market at an early stage, you havean enormous advantage in the long game. This is what we are dealing with in the countries where we are very successful, and one of these countries is Pakistan. In some cities, we are ahead of our competitors, and in general, the annual growth of our ride-hailing business is double-digit, around 45-47%.

Mobility is growing even faster. While there is a lot of room in the ride-hailing business, at a certain point you have to compete more, and the available niches in ride-hailing become less feasible. On the other hand, in terms of intercity, courier and freight, we have grown 2-3x year over year. We still have a lot of opportunities in this segment: eCommerce is booming, while ity-to-city trips are new to this market, so we are investing a lot in this product. This applies to all our products: we have started actively investing in building stronger teams and marketing, as well as in user acquisition.

Another factor to consider is that with improvements in the Pakistan economy, we are expecting that in 2025-26, people will be more willing to spend on eCommerce, which will consequently boost logistics.

Will ride-hailing always remain the mainstay of inDrive in Pakistan?

If you think of some of the other players – a good example is Uber, which started as a ride-hailing company – at some point, they said, “why don’t we deliver food?”. The eats business now probably has a share similar to ride-hailing at Uber. Grab’s business is essentially larger than their ride-hailing. So nothing is certain in the startup world.

We are investing in these new businesses, but will we remain a ride-hailing-centric company in the long run? We’ll see.

After ride-hailing, which other mobility segment is inDrive focusing on?

I would say it is very region-specific. In some markets, we are focusing on our intercity service. In other markets, we see a large demand for last-mile courier delivery; for example, in Latin America, we have made very nice progress in some cities in terms of couriers. And with freight, there is 5x growth year-on-year in Pakistan. There is demand and there is supply. All we have to do is match those guys.

What kind of resources is inDrive allocating for Pakistan, and how are you allocating these resources across different mobility segments?

If we see a particular market showing us great results and there is a product-market fit, it will get additional money. It is similar to investing in startups: If some guys are successful and there is a product-market fit, and they are showing good traction and good unit economics, you want to give them money because they are ultimately going to grow and become successful. This is the approach I am trying to implement in the services.

Also, when we know that we need to fix something in the product and there is a product-market fit, we may invest more money. This is an iterative process. While inDrive is a big company now, it is very important to stay fluid and entrepreneurial, to try figure out how we can move faster in terms of product development and experiments.

For example, historically, our courier and delivery service focused only on peer-to-peer segments, where an individual sends a package to another individual. At some point, businesses started coming to the platform. What we are doing now is fine-tuning our app to address the needs of those businesses.

When do you believe a mature product would be out in the market for other segments?

It depends on how you define maturity. At the moment, we are operationally profitable in terms of our mobility businesses. There might be headwinds and there will be experimentation.

It’s in inDrive’s DNA to always try to test and experiment – we never stop. Even in ride-hailing, yes, the markets are pretty mature; but in some markets, we are still iterating and trying new things, like going cashless. We have never been cashless before in the history of the company.

What frictions do you see in building the product in the current economy?

While Pakistan is going through a turbulent time, the growth in 2021-2022 was quite substantial – around 6% year-on-year. That’s tremendous growth. So regardless of these momentary issues, the economy will stabilize and is going to improve.

And I have heard that Pakistan is doing a lot to improve the situation. I see the trend, and we want to be on top of it, which is why we are investing now. This is going to give us results later on.

Is inDrive planning on investing in or acquiring companies in Pakistan?

So far we have done just one deal; we acquired technology for inDrive’s business delivery offering, and it is currently operating in Kazakhstan. This was done in 2023, and gave us the technology to work with enterprise clients there with the potential of global expansion.

inDrive’s team traveled to Pakistan at the beginning of the year to meet the local startup community. There are some companies that we have good synergy with, but no specific plans as yet.

How has inDrive grown their ride-hailing business in Pakistan and what’s the growth like in other verticals?

For Pakistan, our ride-hailing growth last year was 45%, and we are quite positive about 2024. inDrive.Couriers grew at an amazing rate of 2.6x in terms of orders. Our base is low, but there is a lot of growth. Freight grew fivefold from 2022 to 2023 –this is the growth you usually get in some startups in their early stages.

Our intercity service grew faster than our ride-hailing, so we doubled the business in 2023 as compared to 2022. And I would say we have very similar targets for 2024.

Who is inDrive’s biggest competitor in Pakistan’s market, in all verticals?

We don’t have a single biggest competitor. Competition in the market is quite intense, and more and more global players are looking into Pakistan and seeing opportunities here.

This proves our point – that this market is very lucrative.

How does inDrive plan to penetrate the low-tier cities of Pakistan?

It depends. What we’ve seen in other countries is that the trend to use urban mobility

services comes to smaller cities, for sure. To begin with, not many people in these cities had heard about digital taxis and using an application to call them; everyone was calling a guy they knew to come and pick them up. Within a few years, it changed. People started to adopt this technology and they realized it was quite useful.

This applied to drivers as well: they started to earn more money, and now it is pretty normal.

Coming back to Pakistan, we need to understand not only the size of cities, but also their economic power. For example, Karachi is home to just 8% of Pakistan’s population, but it forms 20% of Pakistan’s GDP. That is huge. We need to consider that while making decisions about our expansion strategy.

Of course, we like the blue ocean strategy, where you go to less competitive places and are the first one there. We often focus on doing that; that investment will yield a lot.

We go into these cities and keep investing, and then if we see an opportunity, we invest more.

How is the Pakistan market different from other markets?

One of the things we’ve noticed is that Pakistan has a very young population in general. That means they will adopt the habit of digitalization soon, if not now. For example, currently, there are some drivers who prefer a more traditional way; they may use WhatsApp, but not applications. This is one of the challenges in the Pakistan markethow do we engage people who are not very familiar with this technology? There are a few markets where we have this issue.

Another thing that stands out in Pakistan is that word of mouth is very powerful. People start telling their friends, colleagues and other merchants that this is a nice service. This means very low-cost organic growth.

But it also requires a specific approach to product and marketing to speak to the audience in their language. A lot of people use English on their smartphones, so for us it is important to create advertisements in both Urdu and English. Sometimes it is better to communicate with the drivers in Urdu, while English works better for communicating with passengers.

How is inDrive going to fund its operations in Pakistan?

Just recently, inDrive secured an additional $150 million from General Catalyst. This is for global investment in product improvements, expanding our service offerings, and entering new markets, and we are very pleased that we achieved this. n

Why have

And what will it take for the Saudis, Chinese and the others to stay?

As I look at the business headlines these days, they are full of potential investors from countries like Saudi Arabia and UAE flocking to Pakistan. A few years earlier, it was the story of the Chinese finding business opportunities in the land of the pure. Perhaps we can also add a few Turkish and Korean ones to the list.

My mind can’t help returning to when my generation started our respective careers. Those were the days of the multinational corporation (MNC). Foreign-owned businesses operating in Pakistan were mainly Western – from the USA, UK, Europe and Asia was represented by a handful of Japanese organisations. What happened to these companies? Some of them may still be around but most went away. Where did they go and why? And if this has anything to do with persistent conditions in Pakistan, what makes these new investors think they will stay for long?

The reasons the multinationals cited for their exits were all

The writer is a strategy consultant who has previously worked at various C-level positions for national and multinational corporations

too familiar: failing or inexistent infrastructure, consumer markets with limited buying power, struggling institutions, and corruption. In effect, what they experienced in Pakistan was a disabling environment for business–as opposed to an enabling one.

This is in line also with the general impression we get from drawing-room conversations–that the adverse law and order and poor governance that has prevailed in Pakistan for many decades is the main reason we do not attract foreign investment. We regularly read or listen to newspaper writers and television anchors beating their chests for the shoddy performance of various governments and state institutions. Not that I am defending that performance as woeful as it is. But are those the only reasons for MNC exits?

To answer this, we must first try to understand the evolution of the Western multinational corporation itself. To a large extent, the MNCs of the 80’s, other than the banking institutions, were engaged in manufacturing – chemicals, pharmaceuticals, paints, agrochemicals, fertilizers, consumer goods and other similar industries. Globally, since then, most of these industries have undergone significant changes in their structures and ownership resulting from either break up of diversified businesses or acquisition by new owners.

Many of the older companies, such as ICI (where I started my career) do not exist anymore, after having divested or shut most of its businesses. Likewise, many of the pharmaceutical and chemical industry giants of yesteryears as well as banks have shut their doors globally. Their exit from Pakistancould therefore be attributed to the evolution of industry structures in their immediate spheres.

Second, and more importantly, is the business model MNCs deployed in developing countries like Pakistan. A majority of their investments were based upon protection offered via government assurances for import tariffs or lower tax and other concessions. However, this model was found to be unsustainable as soon as markets were opened to competition and state grants became unfeasible for the government.

It is critical to keep this in mind for Pakistani policymakers as they try to woo the next breed of potential investors. Any future investments tied into rent-seeking of any sort are detrimental to the country as well as to the investors. We have seen the adverse impact of concessions offered to the plethora of energy businesses recently.

Third, the advent of China as a manufacturing hub became a deterrent for production to be done in Pakistan. Most MNCs requiring enhanced production capacities,invested via joint ventures in China as they could cater to the large Chinese market as well as have the scale to

competitively ship their products to Pakistan and other similar markets. The liberal import environment in Pakistan naturally supported this phenomenon.

What about the ones which have stayed – thus far at least? We see some large FMCG, Sugary drinks and food businesses staying and thriving mainly based on the large population which continues todemand these products. I cannot recollect any other industrial sector to have any significant MNC presence.

How do we learn from the above - to prevent new investments suffering from the fate of the older MNCs? We need to look at this from both perspectives –as a country, we need foreign investment to help us achieve economic growth – as well as with the lens of foreign investors who need to grow their businesses and make decent returns on their investments.

As Pakistanis, policymakers should pay attention to the basic fact that capital seeks returns from businesses. The best measure of business viability is the size and strength of the market and in this case – the attraction of the domestic Pakistani market.

We have a sizeable population albeit with low purchasing power and until this is enhanced, we need to offer our population

products and services which complement their purchasing power.

In the past, this has not been so, with investments in sectors such as real estate and automobiles andsimilar sectors encouraged for the consumption of the few. The policy design this time around must showcase viable markets instead of rents from the government.

Affordable and accessible transport and medical care, good education and availability of nutritious food are some basic needs that most people in Pakistan still find missing. Anyone investing to solve these problems and provide even half-decent products and services in similar areas will find long-term viability.

The onus is really on the foreign investors themselves - the new ones should realize that Pakistan is not a country where quick returns can be made. It will require patience and a long-term commitment to creating markets for their goods and services.

More specifically, they will need to reduce the barriers to consumption by offering lower costs, enabling consumers to access the product or service with ease, making it simple to use and reducing the time required.

They should deploy innovative technologies and processes and create new value net-

works while still providing adequate returns and a path to profitability for their businesses.

One of the great services that the older MNCs provided to Pakistan and similar countries is the development and training of management talent. This not only built the capability for Pakistani management to undertake leadership roles globally but in doing so, created prosperity for themselves and their families.

In this regard, any future investors (local or international) must continue to invest in cultures which build high-performing management teams, that in turn, provide the building blocks for the future success of their businesses.

Last, but not the least, new investors must again be warned against accepting government incentives as the “raison d’eter” for their investments. Any business built on rent-seeking and not on viable markets is unlikely to succeed.

The Saudis and the Chinese, as well as any other foreign investors, need to look hard at the type of international businesses which have stayed and prospered in Pakistan. Without this critical analysis, we will be talking about another mass exodus of global investors and their companies from Pakistan in ten years or so. n

As telecom revenues face the threat of macroeconomic challenges and the rise of OTT platforms, Jazz is creating its presence in low-cost, high margin services beyond telecomBy Taimoor Hassan

In 2017, Jazz made a mistake. In the face of the rising threat of tech to the telecommunication industry, they launched an application by the name of Veon, which is also the name of Jazz’s Dutch parent company.

The concept was simple. The Veon app would be what is known as a Super-App. Sort of like WeChat in China, which does everything from ride-hailing to payments, entertainment, and anything else under the sun. The experiment failed.

Now, they’re back to trying the same thing. In addition to the news that Jazz would be going public and listing on the stock exchange, the company is on a mission to once again step away from their telco routes and get into the digital game.

Except this time they’re doing things a little differently. Instead of trying to create one big Super-App, Jazz is launching a number of different applications. These apps, ranging from messaging platforms to entertainment, will break down the Super-App into more digestible pieces.

Why is Jazz doing this? Easy. Telcos the world over have over the past decade faced a harsh reality. The business has low-margins for starters. On top of this, they provide mobile broadband data at cheap rates in competitive environments which people then use to operate apps like Whatsapp. This is the very same application that is the competitor for telcos because of its easier interface for calling and texting.

But will they manage to pull it off this time around?

Jazz was ahead of the game. The first 3G and 4G internet being provided by telcos hit the markets back in 2014. Up until this point, the main mode of telephonic communication for most people was through phone calls and SMS. But with the advent of this new technology, the adoption of different messaging services was very quickly adopted. Initially, Viber became popular in Pakistan before a larger shift to Whatsapp was seen. These applications offered seamless calling and messaging for free as long as you had internet. With 3G and 4G available, people were moving towards using these “free” services much more than regular telco calling and messaging. This meant that these telcos

were now providing the broadband data that was helping to cannibalise their calling and messaging business.

Jazz picked up on this quickly. Owing to this threat Veon was launched by Jazz in October 2017 as a multipurpose app with the vision of becoming Pakistan’s version of WeChat. They essentially figured out that if Pakistanis were switching to broadband based messaging, they would provide the platform to them along with the broadband internet. Aamir Ibrahim, Jazz’s CEO, had emphasised the necessity of innovation, stating that the risk of not taking the leap into app development was far greater than the risk of failure.

This initiative aimed to integrate various functionalities, such as messaging service, news feeds, self-service mobile top-ups, and cellular bill payments, into a single platform. By creating an all-in-one app, Jazz hoped to attract a large user base, subsequently generating revenue through service sales and advertising. The concept was to offer a seamless digital experience to Pakistani users, much like how WeChat operates in China.

But it wasn’t going to be easy creating a Pakistani WeChat. The success of WeChat is largely attributed to the Chinese government’s stringent internet policies, which restrict foreign competitors and allow domestic apps to flourish. WeChat’s comprehensive features and integration into daily life have made it an indispensable tool for Chinese users, encompassing everything from communication to financial transactions. This ecosystem approach has turned WeChat into a dominant player, deeply embedded in the digital lives of its users.

Veon, of course, would still be cannibalising the calling and texting revenue of Jazz. But as Amir Ibrahim said back then, it was better that their own app was doing so than any other competitor such as Whatsapp. The service was offered free for Jazz sim owners but had a charge for users from other telcos. Not only would this have lured customers from other networks over to Jazz, the users on the app would have generated revenue through selling services as well as through ad revenue.

Veon’s road was laden with obstacles. For starters, they quickly found out Pakistan’s digital environment is not comparable to China’s. Unlike China, Pakistan does not impose strict restrictions on foreign apps, which means global giants like Facebook, WhatsApp, and Google dominate the market. Veon struggled to compete against these established platforms, which already had a vast

user base in Pakistan. Additionally, operational challenges, such as changes in partnerships and strategic missteps, further hindered Veon’s ability to gain traction.

Aamir was candid enough to then say that the company had tried to do too many things on a single app and that the initial Veon platform was not strong enough, leading to a response that was not up to the expectations of the management. In a later interview with Profit, an official from Jazz disclosed that the Veon app had technological issues because of which users couldn’t place calls or the sent messages wouldn’t be received which resulted in the app’s failure.

Veon’s failure highlighted the risks Jazz faced in trying to diversify beyond traditional telecom services. The attempt to replicate WeChat’s success without a similar regulatory environment and existing user behaviours proved overly optimistic. Jazz had to contend with the reality that while their infrastructure supported innovative applications, the competitive landscape was not conducive to a homegrown super app displacing established global players. This experience underscored the necessity for Jazz to focus on more viable growth areas, such as JazzCash, which showed greater potential in the local market.

Veon’s launch was a bold step, especially given the competitive and regulatory landscape. Jazz’s strategy of offering Veon services for free to its customers — regardless of their credit balance — raised concerns among competitors. This move had the potential to attract users from other networks, further intensifying competition. And the competition did not just idly stand by and watch. Zong, for instance, responded by offering unlimited access to WhatsApp services, highlighting the aggressive tactics adopted by competitors to counteract Veon’s influence. Despite these competitive pressures, Jazz remained committed to its vision. The company’s CEO, Aamir Ibrahim, emphasised the necessity of adapting to the changing market to avoid becoming obsolete. And the challenge wasn’t just going to be Whatsapp or other messaging services anymore.

Veon did not catch on. Its downloads in Pakistan were low, adaptability proved difficult, and customer acquisition never really caught on. At the same time, Jazz had other things to focus on. They had launched Jazz Cash in 2012 and

continued to grow the fintech enterprise.

It became clear over time that the competition was not just platforms like Whatsapp and Viber. It was also other platforms such as Instagram and Facebook which provided entertainment as well as messaging. People were using their data watch and scroll content on these platforms. In 2019, after the failure of the Super App dream, Veon was shelved.

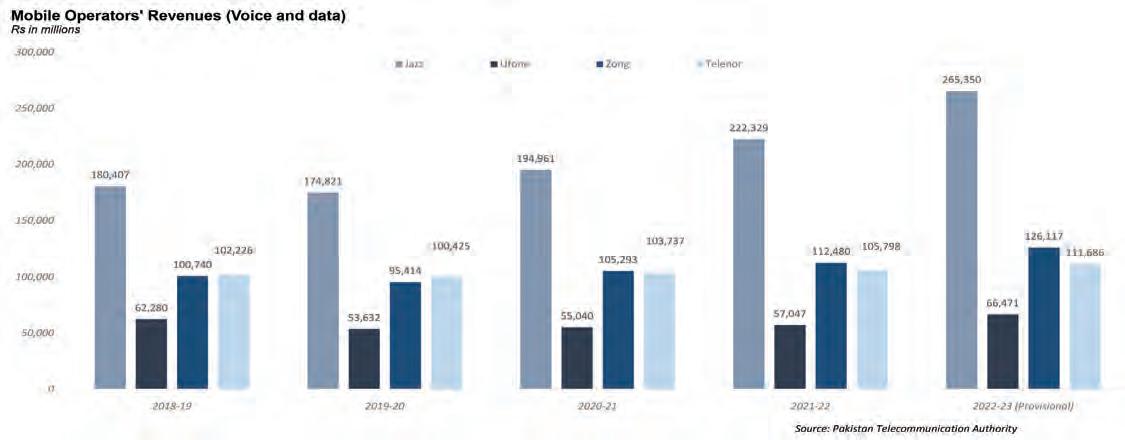

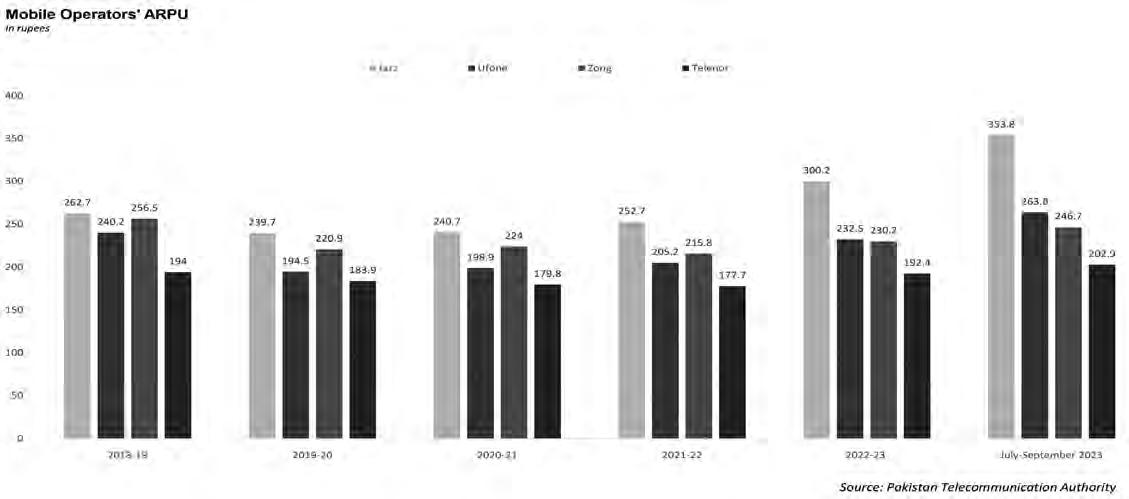

During this time, profitability for telcos fell overall. The way this industry calculates its earnings is through a system known as ARPU — average revenue per user. Earlier this year, Telenor exited Pakistan citing the fact that they had a persistently low ARPU of around $1. For them to be viable, the company needed to raise this number to at least $1.5.

The main problem for all telcos has been that they operate in an environment with multiple competitors and very low margins. The market is oversaturated with three players even after the exit of Telenor. On top of this, inflation has meant consistently rising costs of doing business.

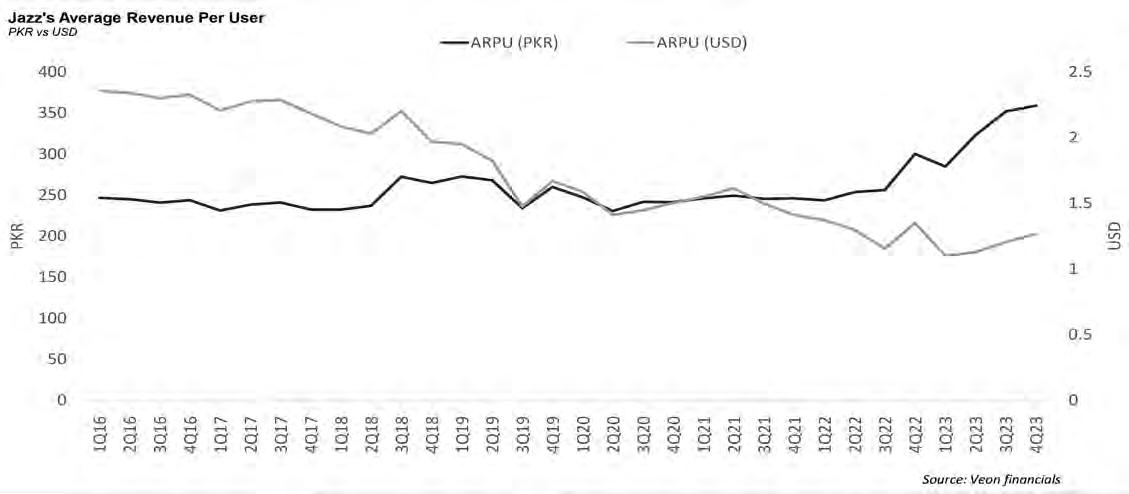

Just take a look at how Veon has performed in recent times. In 2023, their total revenue grew by nearly 20% and EBITDA grew by 4.9%. But multinationals like Veon (Jazz’s parent company) evaluate the performance of their local subsidiaries in dollars and this is also the currency in which the subsidiaries will be valued so any significant devaluation of domestic currency would have ramifications for local subsidiaries. This is exactly the case with the Pakistani rupee and Jazz.

Thus in dollar terms, the revenue in Pakistan was down by 12.9% in 2023 compared to 2022, and the EBITDA was down by 23%.

Further, the ARPU in dollars also paints a contrasting picture when compared to the same in rupee. While the ARPU in rupees has been growing consistently, and Jazz has the highest ARPU growth compared to others, the

growth in dollar terms is not proportionate.

But Jazz never really gave up on the Super App dream. It just changed how it wanted to implement it. It began what it named its “Digital Operator 1440” strategy, also being implemented by its parent company VEON in other markets such as Bangladdesh and Ukraine. The name comes from the 1440 minutes that are there in a day. The goal was for Jazz to gain the attention of its users for as many of these minutes as possible.

Jazz’s recent investment of over Rs5.3 billion in the first quarter of 2024 reflects its commitment to fortifying its digital presence and the increasing focus towards becoming a tech company. Additionally, Jazz’s recent issuance of a Rs15 billion Sukuk marks a strategic move to bolster its financial liquidity, enabling further development of its digital services portfolio. This transition to digital not only mirrors the shift from conventional telecom to services that people want to spend their data and time on (OTT services is the technical term). The idea is that because OTT services are available over the internet it leads to an increase in data consumption of telcos. But if a telco itself has multiple applications and the telco is able to keep users engaged on these apps, not only could this counter the threat from OTTs but would also incrementally increase revenue from selling data. That is besides, these apps have their own sources of monetization as well.

As part of this new strategy, Jazz is launching a number of new apps. Some of them are challenging existing platforms for consumer attention. These are apps that offer messaging services, entertainment, and other facilities. And then there are other new business streams Jazz is launching. These include streams that do not have anything even remotely to do with their initial telco operations.

The following is an overview of what each platform is meant to do and what challengers it hopes to take on.

Perhaps more than anything, Tamasha represents what Jazz is trying to achieve. The platform has emerged as the largest digital cable service in the country, offering over 75 TV channels, video-on-demand (VOD) options, and some international content. Its extensive coverage includes 20 cricket tournaments, generating 8 billion minutes of viewing time. With 12-13 million monthly active users and 2-2.5 million daily active users, 40% of whom are non-Jazz customers, Tamasha has become a significant player in the OTT space. In 2023 alone, it attracted Rs 600-700 million in ad revenue, highlighting its commercial viability.

On Tuesday, Jazz announced that it had secured digital streaming rights for ICC cricket tournaments in 2024 and 2025 for Tamasha app. This has allowed the app to gain many initial users, something it failed to do with the Veon platform. But there are some problems with this. There are a few ways for platforms such as Tamasha to make money, and the key is content. The first method is to be like Youtube, which allows consumers to upload their own content and then runs ads for revenue. The second method is to be like Netflix, control their content, and ask for money for subscriptions.

Ideally for Tamasha, what they would do is create their own content such as television dramas or even news and run ads to make money. As things stand right now, Tamasha is only picking up content from others. And the day they cannot win the bid for digital rights to cricket, their business model would fall flat.

So far, its mainstay for monetization includes streaming of live cricket and that could be a problem. There are multiple other options for watching live cricket, one of them being tele-

vision channels which are the dominant mode for watching sports. Digital streaming rights are also not awarded for life which means that as soon as these rights go to some other OTT platform, the revenue stream gets in trouble.

While Jazz has produced exclusive content, the volume is small. But executives say they are on track to produce more as well. The competition in this space is also very tough with the formidable presence of Youtube that allows outside creators to post exclusive content, as well as competition from other OTT platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime. Local platforms such as Begin and Tapmad, as well as Daraz which recently ventured into streaming live cricket are also rising. On top of this, Jazz currently does not have a team of creatives for content on the Tamasha app.

This is perhaps the biggest success story Jazz has. The app that needs no introduction has become an integral component of financial inclusion in Pakistan. JazzCash is among the top apps, ahead of many of the banks. The jewel in Jazz’s crown with 44 million wallets, JazzCash allows its users cash-in and cash-out services through a network of branchless banking agents, in app payments transactions, and disbursement of loans from the books of Mobilink Microfinance Bank. All of this makes JazzCash a lucrative venture and the top app under Jazz’s DO1440 strategy.

As Jazz moves forward with its strategy, it plans to further solidify JazzCash’s position in the digital financial services segment by making it an embedded finance app. Other than increasing their focus on lending, the products that Jazz plans to introduce on JazzCash include insurance, wealth management, and the

investment products such as in gold and real estate via tokenization.

This one is a case of trying to use every piece of the cow. Simosa is the rebranded version of JazzWorld. It offers users a platform to manage their Jazz accounts, access faith-related content, read news, and play games. As a lifestyle app, Simosa is designed to serve as a one-stopshop for multiple needs and sells digital ad space. The idea is to make Simosa an everyday app and give enough functionalities that users start spending a considerable time on the app. The problem, however, is that the app is pretty much something users would use once a month to recharge their accounts.

The road to monetization is going to be rough for the Simosa app, given that Simosa is primarily an app for Jazz customers to manage their accounts such as managing packages, activities that are not done on a frequent basis, weekly or monthly. Though the platform could be opened for other telcos as well and is in works, it is going to be a challenging task to have competitors on the app that is owned by the largest telco. The other functionalities such as faith have established competition from apps like Islam360 that offer more functionalities than Simosa’s faith section.

Rox, an app similar to Simosa that caters to a younger audience, also offers a range of services designed to cater to the diverse needs of its users. These services include telecom offer -

ings such as voice and data bundles, along with an array of digital perks. By partnering with leading lifestyle brands like foodpanda, Careem, and Bookme, Rox provides users with exclusive deals and discounts, enhancing their digital lifestyle.

This one is a shot in the dark. BiP is a messaging app. The problem is it seems difficult to compete with Whatsapp, which has slowly become the default messaging platform for Pakistanis. BiP is a Turkish messaging service owned by Turkcell and Jazz has launched it in Pakistan in partnership with its Turkish counterpart. Its development aligns with Jazz’s strategy to capture a share of the messaging app market by offering a locally-tailored alternative.

The chances of BiP working in Pakistan understandably look slim because of the dominant presence of WhatsApp which is popular even in the lowest strata of the country. It could work if regulators in Pakistan decide to limit WhatsApp functionalities in Pakistan just like regulators in countries in the Middle East have done, or ban WhatsApp altogether. On top of WhatsApp, there is also a presence of services like Zoom, Google Meets, Teams and Skype, leaving less room for another messaging app to become successful.

But Jazz could have something up the sleeves: in a potentially disruptive move, BiP, an internet-based service, could call on your landline or cell phone number on any network. There is still a big number of feature phones in Pakistan which can not use any internet dependent OTT services. About 40%

of the phones in Pakistan are still feature phones. Smartphone users that use BiP could call feature phone users through this option which is not available on WhatsApp or any other app. For Jazz users, BiP could be functional even without the internet if they are near a Jazz tower.

While calls like these are technically possible, this would have to clear any regulatory bottlenecks before it could be launched. With this function, BiP would have the chance to become a success. There is also another possibility. If the government of Pakistan at any point decides to ban Whatsapp (as it has done with Twitter currently and Youtube in the past), Jazz could have an opening with BiP. But that is something entirely out of their control.

This is where we get to the part where Jazz is introducing business vertices that are not in the slightest to do with any of their previous business interests.

Launched after Pakistan’s Cloud First Policy was introduced in 2022, Garaj not only hosts Jazz’s suite of apps but also provides services to businesses in different sectors forming a new revenue stream. Serving 300 customers and targeting specific sectors like financial services and healthcare, Garaj exemplifies Jazz’s innovative approach to leveraging cloud technology for business growth.

Launched in November 2023, Quantica allows telcos to monetize the vast amounts of data generated by their networks. By anonymizing and

aggregating this data, Quantica provides valuable insights to its business customers, allowing them better decision making. Quantica offers two primary services which help solve business problems through a combination of customer data and insights generated from Jazz’s data, thus enhancing business decision-making.

Jazz is trying to do a lot here. One might even say they are getting a little desperate with it. But that desperation is good. Jazz is perhaps the only telco not just realising the problems that exist in their industry, but are very actively doing a lot to try and fight back.

The years to come might prove to change Jazz entirely. Currently, the telco business and Jazz Cash are the biggest businesses they have at their disposal. But it is entirely possible if even one of their new ventures or attempts takes off, that it becomes the identity of Jazz a decade from now.

What do the numbers say about how they are doing currently with this new strategy? Seemingly, Jazz is on the right trajectory. In the first quarter of 2024, Jazz showcased significant growth across its digital and fintech services, reflecting a strong performance trajectory. The total revenues soared by 28.7% year-over-year (19.2% in USD terms), primarily fueled by an increase in 4G user adoption and strategic inflationary pricing adjustments.

This growth strategy led to a 30.3% increase in average ARPU. Particularly impressive was the performance of Jazz’s

fintech service, JazzCash, which saw service revenues skyrocket by 98.0% YoY, demonstrating robust growth in this segment.

Jazz continued to enhance its digital services portfolio, evidenced by a 25.5% YoY increase in multiplay customers who engage with offerings such as JazzCash, Simosa and Tamasha.

These multiplay customers now constitute 28.9% of Jazz’s monthly active consumer base, significantly contributing to the operator’s revenue — accounting for 56.6% of B2C segment revenues. Furthermore, the expansion of JazzCash was highlighted by its massive customer engagement, with 7.9 million digital loans issued and a gross transaction value of Rs6.6 trillion, marking a 47.1% increase YoY.

But the problem at the end remains: if the growth does not translate into a meaningful growth in ARPU, it which still hovers around $1, becomes increasingly difficult to sustain. High-ranking executives from Jazz have also told Profit in background conversation that ARPU remains the biggest concern for the telco and that despite the launch of multiple digital services, ARPU was not growing promisingly.

Perhaps it is because Jazz digital services still form less than 15% of the company’s revenues. As this revenue grows, more ARPU could be expected but that remains uncertain because monetizing the apps would remain a challenge as explained above. What is certain is that Jazz’s transformation towards becoming a technology company has begun and there could come a time when revenues from digital services could match or possibly exceed revenues from telecom services, changing Jazz’s distinction as a telecom company permanently. n

A carbon tax on petrol would appease the IMF, and possibly decimate the salaried classes.

A carbon tax on petrol makes good economic sense for the federation. It does not, however, fall in line with the Pakistani government’s Santa Claus mentality. Which argument will prevail?

By Abdullah NiaziIn what can only be described as a rare cosmological event, the government of Pakistan might have had a good idea: A carbon tax on petrol.

As a state, Pakistan has never really learned how to collect taxes. There are long, tedious explanations for why this is so, but to cut a very long story short, taxation is centralised. That means the federal government through the FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award

leaving the federal government with very little spending money.

The proposed carbon tax would make life much easier for the federal government. For starters, it would give them revenue that they wouldn’t have to share with the provinces. It would placate the IMF, which has been on Pakistan’s case to rationalise petrol pricing and move towards a Value Added Taxation (VAT) system to price petrol. It would also allow the government to show off how green it is to international lenders, enabling the issuing of green bonds and e-bonds, and gaining access to all sorts of funds cheaper from multilateral financial institutions.

What the tax definitely won’t do, of

course, is make petrol cheaper. Normally, the purpose of a carbon tax would be to discourage the use of petrol. But alternatives to using petrol are next to non-existent in Pakistan. Electric vehicles are unaffordable and often non scaleable. Public transport is in shambles. In this particular case, the government of Pakistan would be imposing a carbon tax less to be a green government and more as a clever bit of accounting that would allow the federal government to pocket taxes through the sale of petrol.

But that isn’t quite the problem one might think it to be. Petrol prices are going to rise no matter what. Pakistan is currently on a mission to enter a much larger IMF facili-

ty than the one that just ended. The IMF is playing hard to get and the government knows it has no other choice. The only thing they are changing is how they increase the price of petrol and gain benefit from it. The only thing stopping them is political will.

Every government that has ever come and gone in Pakistan has had to deal with the politicisation of petrol. If the prices are high, the opposition cries foul. If they fall, the government takes credit for every rupee. A commitment to a carbon tax would mean a commitment to keeping petrol expensive, even when there is an opportunity to decrease them. And as has become clear to Profit over the past few days, the opposition to this is already rolling in.

It might seem like a non-event, but it goes to the heart of everything wrong with taxation and fuel policy in Pakistan. On the 16th of May, the government of Pakistan announced it was cutting petrol prices by Rs 15, bringing them down to Rs 273.10 per litre.

Petrol prices in Pakistan are determined by a number of factors. The main input is the international price of crude oil, which is imported into the country by oil refineries which then process it and turn it into fuel. The price of fuel after processing is what is known as the ex-refinery price. But then other things get tagged along onto this. A margin is added to make sure the price is uniform throughout the country and not cheaper in areas close to the refinery, distributors naturally take a cut, and then dealers and petrol pumps also charge their own service premiums. On top of this, the government also takes a cut. Petrol is currently subject to a petroleum levy of around Rs 40 per litre.

Ex-refinery price — The cost at which refineries sell petrol to oil marketing companies (OMCs) like PSO, Shell, and Total. IFEM — This is added to ensure a uniform price across the country. Without IFEM, petrol prices in cities far from refineries would be much higher than in cities close by. Distributor margin — The government sets the maximum margin that OMCs can earn per litre of petrol Dealer commission — Similar to the distributor margin but for petrol pump owners

Petroleum levy and other taxes — As charged by the government

As we mentioned at the beginning, the government is not good at collecting taxes because there is only one tax collector with not enough infrastructure to keep an eye on everything. So the levy is charged to the end consumer and directly transferred to the FBR.

The IMF has long held, and correctly so, that this is a counterproductive system. The fund’s argument is that a VAT system should be implemented in which the value added at each stage of a product getting to the end consumer should be taxed. Without getting into too many details, this would mean the refinery would be charged a tax first, then the transporters, then the distributors and so on and so forth until the final price hits the markets and the tax is passed on to the consumer. This would not just mean that the tax on petrol would not be arbitrarily set (as the petrol levy is right now), it would also help document the economy better.

As part of this, the IMF wants the government to increase the sales tax on petrol at different stages. In the previous budget, the fund had recommended 18% GST be charged on petrol products. But this poses a problem for the government. One of the biggest earners for the federal government is in fact petrol. The government actually budgeted in a way that it expected to collect nearly Rs 900 billion from the petroleum levy. But the sales tax on petrol would be subject to the NFC award, which means the government would have to share the spoils with the provinces.

This is where the carbon tax comes in. A carbon tax is a tax governments around the world can impose on industries that produce and release carbon dioxide into the environment through their business endeavours. Theoretically a carbon tax could be implemented on any industry that burns fossil fuels. The tax is calculated in proportion to their carbon content.

So if an industry produces 1 unit of carbon, the government can charge a certain percentage of their production. In the case of a carbon tax on petrol in Pakistan, the easiest way to go about this would be to charge the oil refineries. Remember, oil refineries are the companies importing oil into the country. The government can calculate an average rate of how much carbon is emitted per every barrel of crude imported. This would directly tax the refinery which would help in documentation, thus fulfilling the IMF’s objective of wanting a VAT system.

On top of this, it would also mean goodies for the government of Pakistan. The government, as per sources, is hoping that the imposition of a carbon tax would help Pakistan convince the IMF to give them a better deal through their Resilience and Sustainability Trust, which is a pool of money they to help

low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries build resilience to external shocks and ensure sustainable growth, contributing to their longer-term balance of payments stability. It complements the IMF’s existing lending toolkit by providing longer-term, affordable financing to address longer-term challenges, including climate change and pandemic preparedness.

As reported earlier by Dawn, carbon tax was one of the measures being deliberated that could also help garner international financial support for newer aid instruments, including green and e-bonds and cheaper loans and grants from multilateral institutions. The future development programme is already being aligned with climate public investment management benchmarks, the sources added.

Now here’s the rub. The government of Pakistan is not quite considering this carbon tax with the purest of intentions. In normal circumstances, the goal is to decrease carbon emissions by discouraging the use of whatever product is being taxed.

This would not be the first time that petrol was taxed on an emissions basis anywhere in the world. Europe is a very good example, where a study of 26 countries found that fuel taxes have a moderate impact on general road emissions and, in some cases, also on passenger car emissions. The study also found that while increasing fuel prices was a challenge politically, governments should stress the growing economic affordability of fuels and the negative consequences of car transportation.

It would be foolish to discount entirely an effect that such a carbon tax would have in Pakistan. The demand for petrol has fallen due to inflationary pressure over time. In the first half of the fiscal year 2024, the government made record breaking revenues through the petroleum levy. However, sales of petrol have gone down 6.6% year-on-year in the first half of the fiscal year.

And while inflationary pressure can reduce petrol usage, it can never really be enough. In the case of petrol in Pakistan, however, the demand is very much inelastic. There is no infrastructure either for electric vehicles or for public transport that can easily convince the public to switch from using cars and motorbikes. People need to buy fuel to get to work and to commute in their daily lives. Reductions could come from workplaces giving more work from home days or people with cars switching to bikes and those with multiple cars cutting down the number of their vehicles. However, the changes will only ever be nominal.

This is where we stand. The IMF wants the government to implement an increased sales tax on the purchase of petrol of around 18% which is standard in the rest of the country. The government is hesitant to do this because the money collected from those taxes would be subject to the NFC award and distributed to the provinces. A carbon tax allows the government to tax refineries directly at a set rate and earn revenue that they can keep for the federal exchequer.

The IMF, in its definition of a carbon tax, explains that its purpose is “addressing climate change by reducing greenhouse gases, carbon taxes can also generate more immediate environmental and health benefits, particularly by reducing deaths that result from local air pollution. They can also raise significant revenue for governments, revenue they can use to counteract economic harm caused by higher fuel prices. For example, governments could use carbon tax revenue to ease the burden of taxation on workers by lowering personal income and payroll taxes. Carbon tax revenue could also fund productive investments to help achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including reducing hunger, poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation.”

But this will pose a problem to the politicians running the government. Petrol prices, as we mentioned before, are highly politicised. Governments want to reduce the prices as much as they can and one of the major reasons that led Pakistan to its current economic climate is in fact the misguided subsidy first implemented by the Imran Khan administration and then continued by the PDM government. Through a petroleum levy, the government can easily change the price of petrol when it feels it is politically expedient.

However, if a carbon tax is imposed, the government will be beholden to it. The tax will pass on to the consumer and the government cannot risk removing it because that will risk alienating the international financiers that Pakistan is hoping to access through its green policies. It will also risk trouble with the IMF and not be eligible for the green bonds and e-bonds they are currently eyeing.

Implementing the carbon tax will require political will that the government may seriously lack. A GST system would help the provinces. The PML-N coalition partner, the PPP, would be interested in getting this revenue for Sindh and the prime minister’s own niece is in power in the Punjab. In addition to this, Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar sits on the Council of Common Interests where the finance minister does not currently have a seat. Here, matters of

the NFC could be discussed. The Deputy Prime Minister is already well known to favour cuts in petrol prices to gain political capital, which will make the idea of a carbon tax even more difficult to implement.

All in all, while it may not exactly be aimed at going green, the carbon tax is a good idea that can have a win-win effect. The federal government will collect money it desperately needs and the IMF will also be happy, as well as give access to green financing. Petrol prices will go up in any case, whether it is through GST, international oil markets, or through a carbon tax. But the last option gives Pakistan the opportunity to make the best of a bad situation.

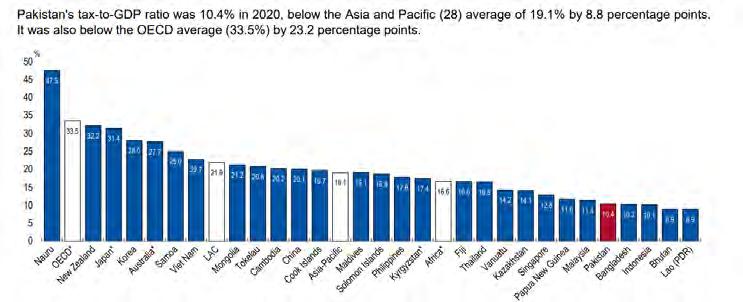

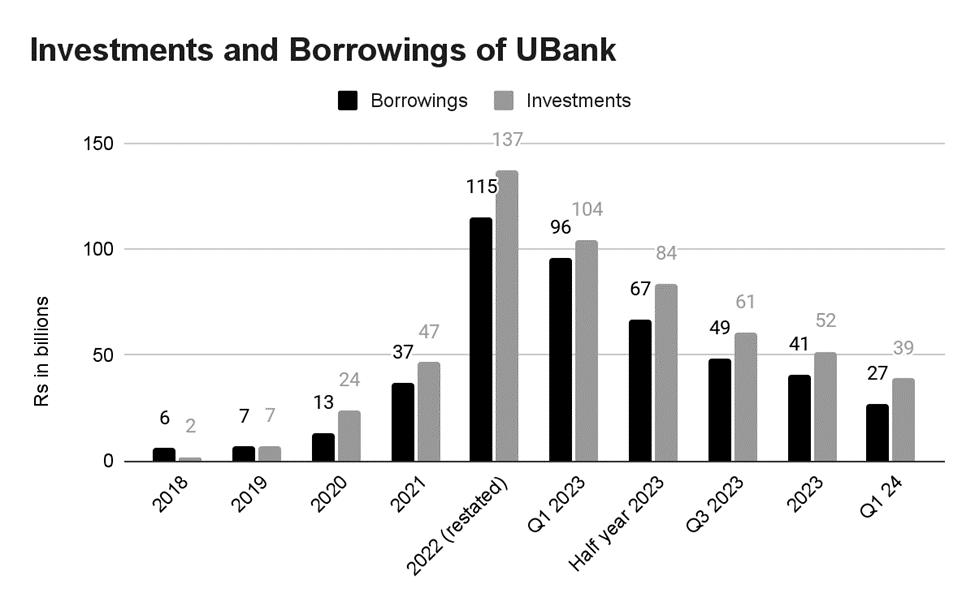

This is something we’ve said before and will continue to say again and again. The real problem is that Pakistanis are taxed unfairly and those that should be paying the lion’s share end up paying nothing. Just take a look at Pakistan’s tax structure. Tax structure refers to the share of each tax in total tax revenues. The highest share of tax revenues in Pakistan in 2020 was derived from value added taxes / goods and services tax (39.8%). The second-highest share of tax revenues in 2020 was derived from other taxes (33.3%).

In comparison to Pakistan, countries in the Asia-Pacific region only collect about 23% of their taxation from goods and services taxes — meaning Pakistan’s average is almost double. Why is this the case? The biggest reason

of course is that taxation in the country is centralised. The FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award leaving the federal government with very little spending money. In an earlier interview former Finance Minister Dr. Hafiz Pasha, while talking to Profit, lamented that, “We as a country have failed to implement the beautiful 18th amendment. The implementation has been slow and weak.” Since the share of the provincial governments, under the NFC awards, over the last few years has been increased from 40% to around 57%, it has provided the provinces with very little incentive to develop their own revenue sources. Despite having access to the two biggest cash cows, services and agriculture, the share of provincial tax revenue is close to 1% of the GDP.

The solution of course is right in front of us: devolution. More than just being a third tier of democracy, having a local bodies system means having a new economic process. In essence, it is not just a new administrative stratification, but also involves the dispensation and spending of money. Things such as education and health that people automatically look towards the provincial government for would now be handled by local representatives. Perhaps most crucially, the ability of local governments to collect taxes and release their own schedule of taxation allows them to make their own money and spend it on themselves rather than waiting for the benevolence of the provincial or federal government. n

calls, what went down

The bank’s profitability has taken a hit post corrective measures initiated on SBP’s behestBy Mariam Umar

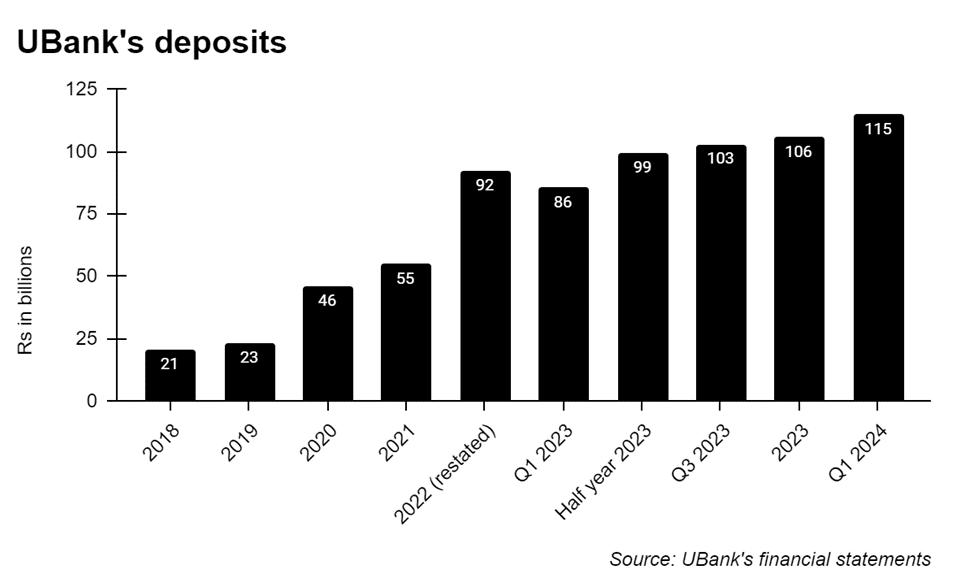

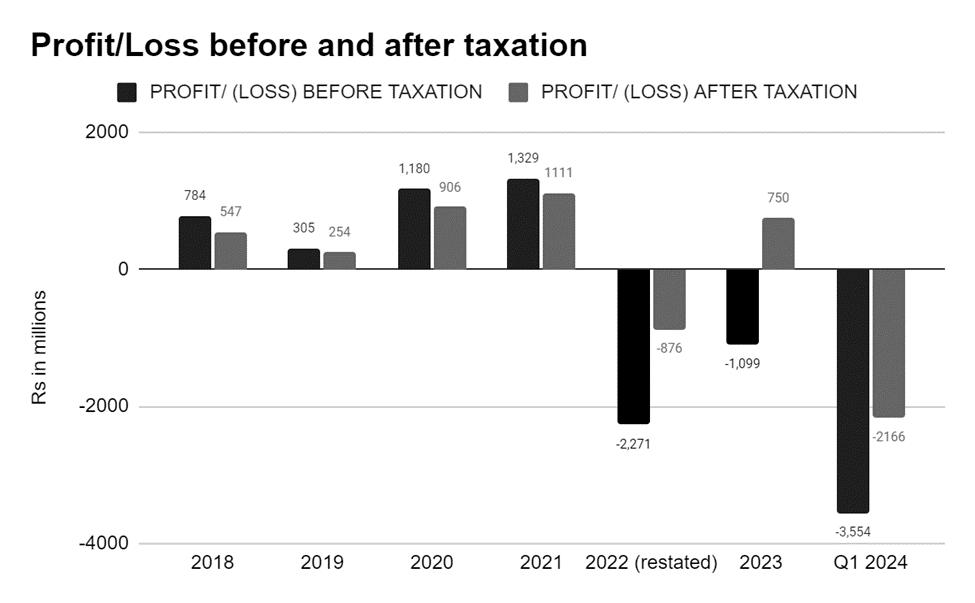

In June 2023, Profit delved into U Microfinance Bank's (Ubank) operational strategy, highlighting its remarkable financial performance. While numerous microfinance institutions floundered in the post-COVID environment, Ubank distinguished itself by not only tripling its balance sheet but also securing a profit of Rs 2.25 billion in 2022. In our story, we commended the bank for achieving a positive bottom line, which is a rare sight in the microfinance sector, especially for industry players that have adhered to conventional business model.

At the same time, the publication also lambasted the bank for achieving this feat by engaging in non-microfinance activities which essentially meant that the bank was operating similar to a leverage hedge fund, investing heavily in government securities. Little did we know that the bank would be at the centre of unexpected turbulence a few months down the line.

By late 2023, dramatic shifts in leadership unfolded with the resignation of CEO Kabeer Naqvi and the delayed release of the bank's mid-year financial statements. Sub -

sequent revelations suggested these changes stemmed from allegations of artificial growth tactics, including questionable applications of IFRS-9 standards that painted an overly optimistic picture of Ubank’s financial health.

The turmoil reached a peak when rumours about the bank's negative equity began circulating, sparking a rush among depositors to withdraw their funds. In response, PTCL Group, the parent company of Ubank, quickly intervened with a press release to quash these speculations. Ultimately, Ubank's financial statements for the first nine months of 2023 were released, showing a downward adjustment in equity to Rs 5 billion, a significant drop from the previously reported figures. The adjustments were part of broader corrective measures mandated by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), including a capital injection by PTCL Group to address potential statutory shortfalls. As 2023 concluded, Ubank disclosed these adjustments in its annual financial statements, reflecting a more transparent and regulated approach to its fiscal management. As of March 2024, equity has further declined to Rs 3.5 billion.

Profit reviews the bank's 2023 financial report to see what went down.

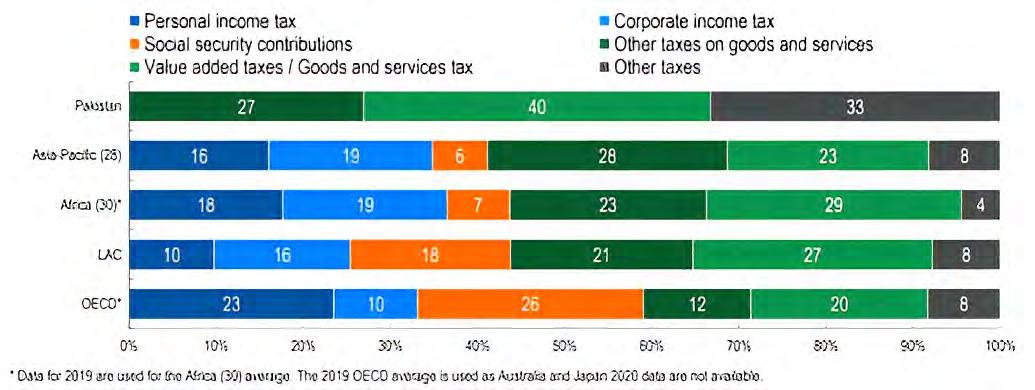

Previously, we reported that UBank seemed to have discovered a method to inflate its balance sheets. In 2022, UBank’s balance sheet grew by threefold. How? The bank used its deposits to purchase money market mutual funds (MMFs) or government securities (T-bills). Then, it pledged those very government securities to the same banks or even a third-party bank, allowing UBank to borrow additional funds through repurchase agreements with a small margin.

With the borrowed money in hand, UBank repeated the process of purchasing more T-bills. This cycle continued, spinning a web of financial manoeuvring so much so that the size of assets increased from Rs 104 billion in 2021 to Rs 221 billion in 2022. At the same time, however, net assets declined from Rs 7.5 billion in 2021 to around Rs 7.09 billion in 2022, a decrease of Rs 0.4 billion (Rs 400 million or Rs 40 crore).

Moreover, UBank essentially sourced a major chunk of its deposits using a quid pro quo arrangement as most of the deposits were from banks and other financial institutions. These deposits were in a sort of give-and-take

arrangement, where any funds received from a financial institution were funnelled right back into the same institution or its associated asset management company. Furthermore, these deposited funds were heavily concentrated, ranging from 25% to a staggering 77% of the fund’s assets.

This growth in assets was majorly from a surge in investments from Rs 47 billion in 2021 to Rs 137 billion in 2022, which was financed through leverage (borrowings increased from Rs 37 billion in 2021 to Rs 115 billion in 2022).

Essentially, UBank was playing a high risk game. In other words, it became a highly leveraged bank, as it had accumulated a lot of government securities. In case of a change in interest rates, the bank could have incurred significant mark-to-market losses.

However, in 2023, UBank made a u-turn from this aggressive growth strategy as both borrowings and investments declined by 64% and 62% respectively.

Naqvi, who was the CEO of UBank then, clarified UBank’s investment approach, emphasising the utilisation of shorter-term instruments to capitalise on increasing interest rates. By borrowing at a fixed rate for a longer duration and investing in shorter-tenor instruments, the bank aimed to leverage interest rate fluctuations to their advantage.

UBank’s method, while aggressive and unique in the microfinance banking sector, aimed to mitigate advance book risks by borrowing heavily from banks and actively managing their necessary investments.

And even if the bank made some loss on treasury operations due to unforeseen economic circumstances, for example, the logic was that his board and shareholders should still be happy as he was successfully securing the bank against a liquidity crisis.

However, 2023 saw a significant change in UBank’s strategy. The bank seeming-

ly reversed its highly leveraged approach, experiencing a substantial decline in both investments and borrowings. The growth

engine (leveraged investment portfolio) was unwound at a fast pace. Investments have more than halved from Rs 137 billion in 2022 to around Rs 52 billion in 2023

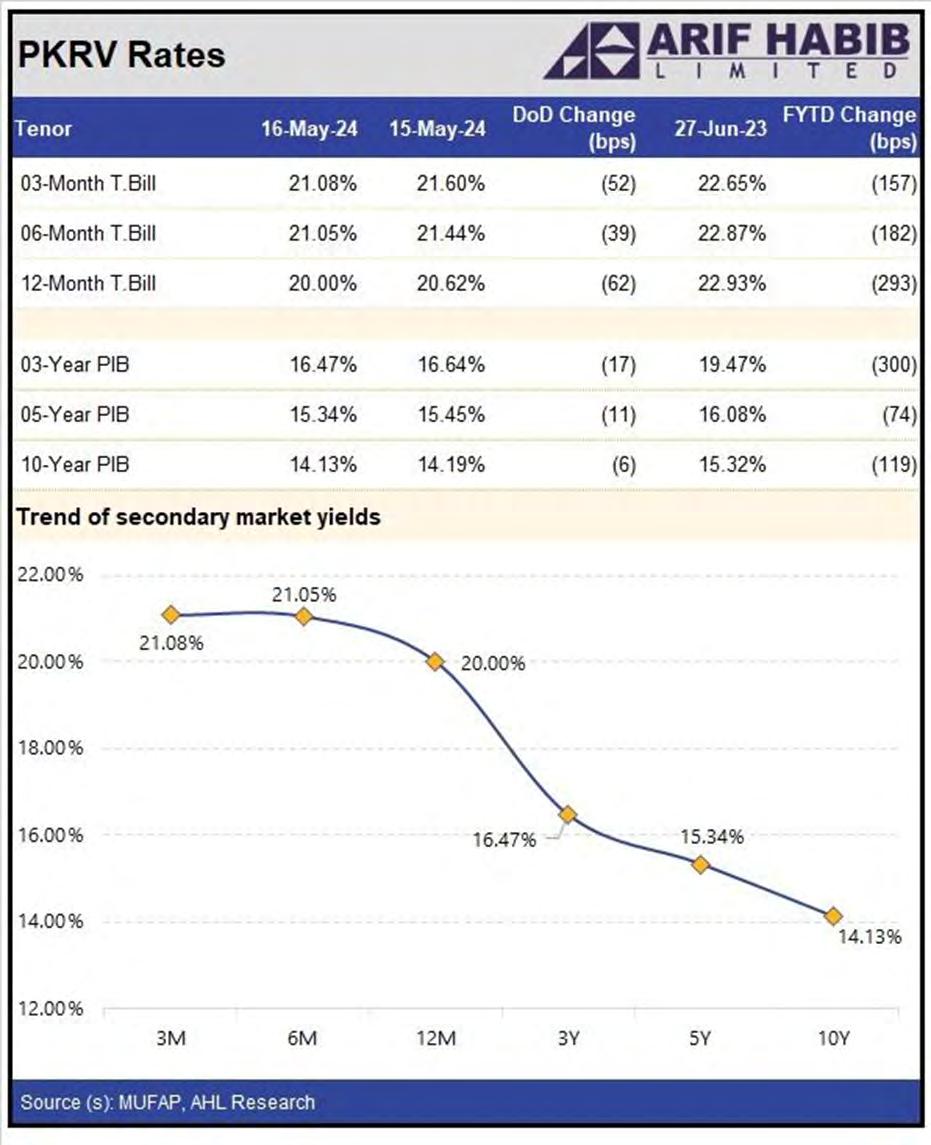

It is only logical for UBank to make this U-turn given that borrowings to invest in government securities is becoming a costly endeavour for the overall banking sector. Yield on investments have declined while cost to finance these assets, i.e. the rate on deposits and borrowings has remained constant.

The cost of borrowing and the interest paid on deposits held with banks are linked to the policy rate. On the other hand, returns on banking assets; investments and advances, are influenced by secondary market sentiments, as demonstrated by the Karachi Interbank Offered Rate (KIBOR) and the secondary market yields on T-bills and PIBs. Although government treasuries are also significantly impacted by the policy rate, they are also influenced by sentiments in the secondary market. Yields in the secondary

market have been below the policy rate since November 2023 as market anticipation of rate cut increased as macroeconomic indicators improved.

While yields for shorter-tenor securities have inched up. However, the market has factored in rate cut for longer tenured instruments.

Hence, it was only logical that UBank reduced its portfolio of government securities along with borrowings to improve profitability and reduce risk.

For any bank, deposits serve as an important source of funding. Low-cost deposits from individuals are a holy grail especially in the current high interest environment. Microfinance banks are no different. To mobilise and attract low-cost deposits, Ubank had been growing its branch network to urban cities. The bank had added around 100 branches in 2022. This expansion spree continued in 2023, as UBank’s branch network increased by 90 branches.

This in contrast with other big telecom-based microfinance banks (Telenor Microfinance Bank and Mobilink Microfinance Bank) that had set their sights on branchless banking and were moving towards digital.

In a previous interview with Profit in June 2023, Naqvi said, “We did not try to turn it into a telecom company. We said that this is a bank, and its mission is microfinance. Just like a bank, its balance sheet will grow. It will have liquidity, strong cash reserves, a treasury function, Islamic banking, digital banking, and even conventional microfinance. It will also have an urban unit responsible for deposit mobilisation. If all these elements are in place, (only then) will this institution thrive and last for the next hundred years.”

These new branches were essentially to bring in low-cost deposits.

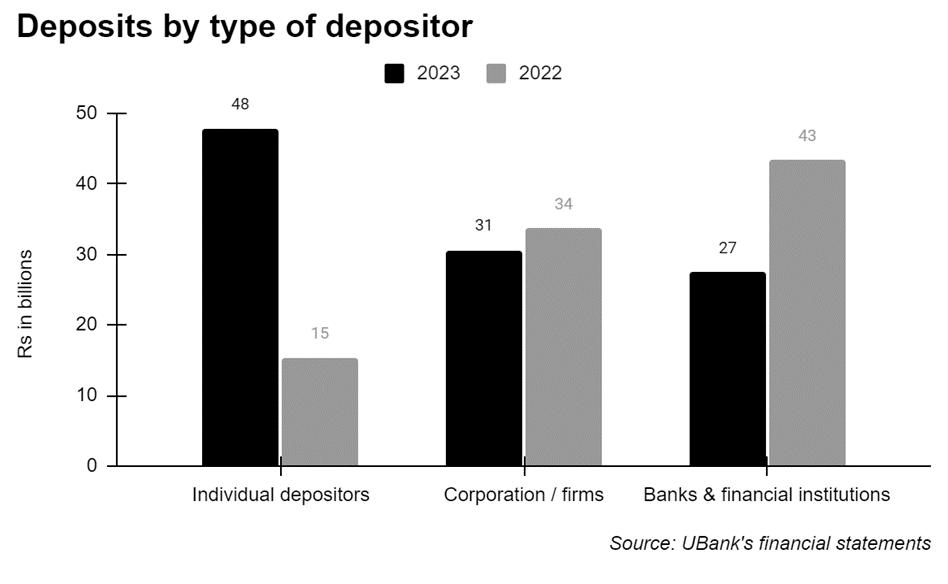

However, despite the expansion efforts, most of the deposits were from other institutions, with the top five depositors contributing a whopping 38% of the total deposits, and the top 10 accounting for nearly half.

Such deposits are not sticky retail deposits but are hot money. These deposits were in a sort of give-and-take arrangement, where any funds received from a financial institution were funnelled right back into the same institution or its associated asset management company.

In our previous story, we predicted that deposits of UBank could decrease significantly owing to the bank’s equity concerns or the PTCL Group will restore confidence in UBank, and any deposits that left the bank would return.

In 2023, UBank’s deposit continued to

grow. Deposits grew by 15% from Rs 92 billion in 2022 to around Rs 106 billion in 2023.

What’s even more remarkable is that the increase in deposits is mainly from individual depositors which shows that expansion efforts are paying off. Besides, institutional deposits have decreased by 37%, almost the same as we predicted earlier.

In the revised financial statements of 2022, there is a notable decrease in net advances (loans) by Rs 4.3 billion, dropping from Rs 59.3 billion to Rs 55 billion. In 2023, net advances increased by around 50% to Rs 82 billion.

This was primarily due to the revised implementation of IFRS-9 under which certain loans were reassessed on the basis of their probability of default.

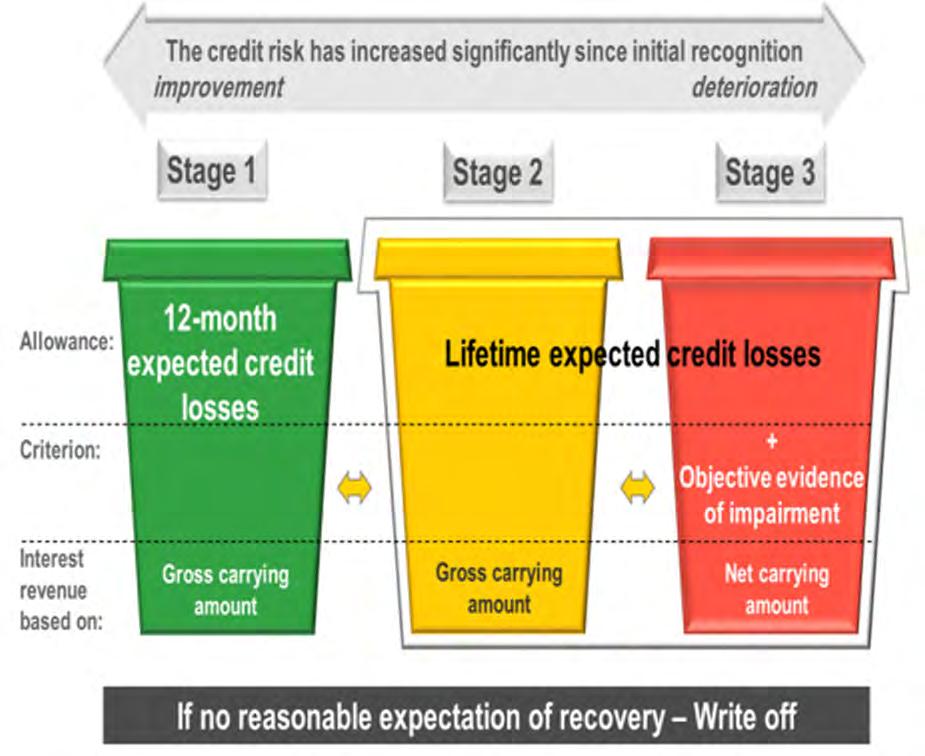

Before delving deeper, it is important to understand a few financial jargons. First is the application of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These, as the name suggests, are global standards that set the rules for drafting financial statements. The standards are adopted by many countries including Pakistan, to ensure the uniformity of financial reporting to allow for comparability of financial statements and investor reliance.

Now the specific standard under question is the IFRS-9. The standard essentially governs the treatment of financial instruments including assets and liabilities. For the purpose of this story, we will be explaining a certain section of that standard which is the Expected Credit Loss (ECL) Model and its impact on the loan portfolio. The standard, under the ECL Model, requires that the outstanding loan portfolio should be assessed periodically,

and an expectation must be developed of its recoverability. If a portion of it is deemed unrecoverable, an appropriate provision should be recorded or in simple terms a loss should be booked.The quantum of the loss depends on the stage of the assessed credit risk. So, initially the loans are placed under stage 1 which doesn’t imply a significant risk of default. However, if there is a significant increase in credit risk like amounts being rescheduled or categorised as NPL, the loans are moved to stage two and three, and additional amounts are provided for.

Now for Ubank, as detailed in the financial statement notes, it reduced its gross advances (loans) in stage 1 from Rs 54.9

billion to Rs 47 billion, marking a difference of approximately Rs 7.9 billion. Simultaneously, there’s been a Rs 7.3 billion increase in gross advances in stage 2. Additionally, gross advances in stage 3 have declined by around 40% from Rs 1.95 billion to Rs 1.18 billion. Moreover, UBank has made adjustments to its credit loss allowance for stages 1 and 2: the allowance for stage 1 has surged significantly, tripling from around Rs 254 million to Rs 819 million, while for stage 2, it has nearly doubled from Rs 2.5 billion to Rs 5.3 billion. However, the credit loss allowance for stage 3 has decreased by 46%, moving from Rs 943 million to Rs 511 million.

Finally, in our previous analysis based on the 2022 annual financial statements, UBank was one of the few profitable microfinance banks.

However, recent reports reveal that this was not the case. UBank reported a loss of Rs 2.3 billion before taxation in 2022. With tax reversals, the loss amounted to Rs 876 million. The bank’s losses continued in 2023 as UBank recorded a loss before taxation of Rs 1.1 billion, and a profit after tax of Rs 750 million following tax reversals. This number is a far cry from the figures released by the bank in the nine monthly financial statement where the bank recorded a profit of Rs 1.7 billion. The bank’s accumulated losses amount to around Rs 1.9 billion which shows that UBank, which was touted as one of the profitable microfinance banks, is in the same league as other undercapitalised microfinance banks.

Resultantly, the Bank’s capital adequacy ratio fell below the regulatory threshold of 15% to 13.86% at the end of 2023. Interestingly, as per the subsequent financial statement released for Q1 2024, the ratio fell further to 9.4%. This isn’t the first time this has transpired in the microfinance industry and there are remedies in place.

And Ubank is exactly moving towards that.

The Board of Directors of PTCL convened on April 18, 2024, and agreed to support the bank's capital structure through the following measures:

a) Conversion of PTCL preference shares into ordinary share capital of Rs. 1,000 million.

b) Conversion of PTCL subordinated debt of Rs. 1,200 million into ordinary share capital. c) Additional cash equity injection of Rs. 1,200 million.

These capital enhancements would have increased the bank's total capital adequacy ratio to 15.4% as of March 31, 2024, and to 16.6% as of December 31, 2023.

Amid the significant buzz Ubank has generated in recent years about its performance and its ambition to evolve into a commercial bank-like microfinance institution, it appears to have encountered significant challenges similar to those faced by its peers in the post-COVID landscape.

The future trajectory of Ubank remains uncertain. However, there's potential for a strategic pivot, particularly towards digital banking, mirroring the path taken by other telco-backed microfinance banks.

A potential area for strategic consolidation following PTCL's acquisition of Telenor could involve considering the acquisition of Telenor Microfinance Bank and its digital assets like Easypaisa. Given that the bank was previously available for sale a few years ago, exploring this opportunity might be a plausible next step for Ubank to consider. n

When it comes to financial inclusion,

Mobilink Bank wants to increase the proportion of female borrowers to a minimum of 50 percent within the next three years

If nothing else, the past few years have seen a definite recognition of the importance that financial inclusion holds for the future of banking in Pakistan. It is a pretty simple equation.

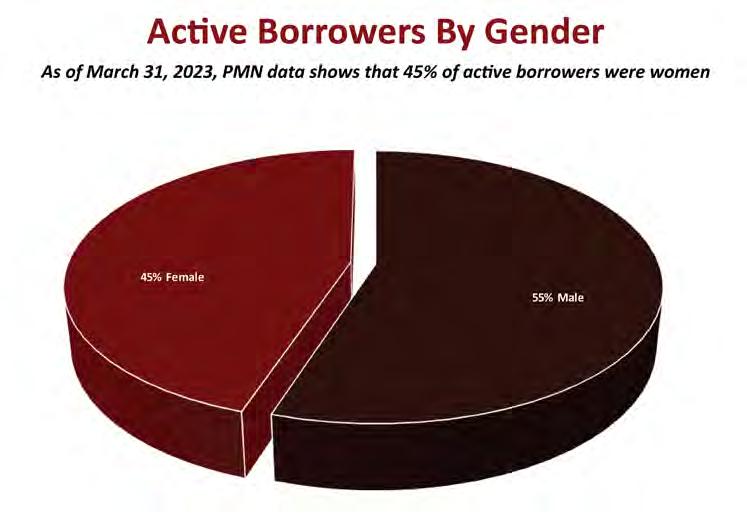

Women make up for nearly half of the population and their access to financial institutions is vital to ensuring sustainable development.

The numbers reflect this too. Just look at Mobilink Bank, which recently announced 38% growth in its women’s loan portfolio during 2023. This would indicate an encouraging upward trend in financial inclusion and access to finance for Pakistani women.

It was, as the Bank’s COO and Interim CEO Haaris Mahmood expressed, proof of the growth potential of Pakistan’s microfinance sector and the financial inclusion of all the citizens. But what exactly does it indicate to us?

Financial inclusion has been a stated mission for the state of Pakistan for some years. In the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) 2015, the goal was to achieve universal financial inclusion by 2020 by bringing 50% of the adult population into the fold of financial inclusion. However, it missed the target by miles. According to the World Bank’s Global Findex, only 21% of adults in Pakistan were financially included by 2021, compared to a global average of 69%, with a persistently wide gender gap.

As per the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Pakistan’s gender finance gap currently stands at 34 percent, which indicates the distance the country still has to cover. Reassuringly, Pakistan’s microfinance sector has been working to deliver on the government’s vision, mainly by employing digital and financial

solutions like mobile money and digital wallets that are accessible to anyone with a smartphone and internet connection. Microfinance institutions have found immense acceptance amongst small-scale borrowers and enterprises looking to expand and enhance their incomes.

What is more important than anything else is consistent effort from financial institutes in ensuring financial inclusion. Just take a look at Mobilink Bank. According to the bank’s yearly financial results, its total loan portfolio stands at nearly PKR 59 billion, a majority of which goes to the country’s agriculture sector. A significant lot of women borrowers also belong to the agro-sector and essentially to the rural economy. In 2023, the Bank disbursed 22 percent of loans to the agriculture sector, of which 16 percent of borrowers were women or

women-led agro-businesses.

“Mobilink Bank’s steadfast commitment lies in empowering the backbone of Pakistan’s economy: women, farmers, and SMEs,” explains Haaris Chaudhary. “We are overjoyed by the resounding success of our initiatives, witnessing a 38 percent surge in our women’s loan portfolio in 2023 alone. Notably, the proportion of female borrowers has escalated to 25 percent, a figure we’re determined to elevate to a minimum of 50 percent within the next three years.”

“The robust growth in our women’s loan portfolio is the fruition of years of hard work to empower women entrepreneurs,” Haaris M. Chaudhary explains, “Our women empowerment program, ‘Women Inspirational Network (WIN)’ has been instrumental in fostering their economic participation and banking nationwide. The program imparts valuable digital and financial skills and knowledge to thousands of women entrepreneurs and borrowers nationwide to help them invest their loans prudently and drive their businesses toward sustainability and resilience,” he stated, further adding that the loans disbursed to women are remarkably high-performing and have impressive return track record.

The Bank witnessed 41% growth in SME portfolio in 2023. Despite its immense growth potential, Pakistan’s SME sector is mired by the country’s macroeconomic situation, which fails to present any encouraging prospects for new investment and entrepreneurship. However, experts believe the sector can enhance its growthsignificantly by adopting digitalization and operating sustainably.

“Sustainability is key to business resilience. Otherwise, new enterprises will crumble in the face of challenges,” says Haaris. “Businesses can foster sustainability and agility through digitalization, saving costs and enhancing operational efficiency and profits. For instance, agro enterprises can expand their customers, reduce time to market, and eliminate middlemen by going digital.”

Mobilink Bank also facilitates conversion to clean energy to promote financial and environmental sustainability of small and medium enterprises. A significant portion of

the bank’s loan portfolio is dedicated to funding solar-powered energy solutions for SMEs. The Bank’s current solar financing portfolio stands at more than 1.7 billion rupees and is poised to grow exponentially over the years. Affordable solar energy solutions can be a game changer for Pakistan. The country has been grappling with chronic power shortages, gravely affecting both enterprise and domestic users, not to mention the adverse effects of fossil fuels that erode the country’s safeguards against climate change. Hence, there is pressing need for effective and timely facilitation from the government and relevant authorities to speed up the country’s conversion to clean and green energy solutions, as sustainable energy will enhance the resilience of small-scale businesses, especially across disaster-prone regions, to protect the livelihoods of low-income and vulnerable segments. Experts also highlight the need to enhance digital infrastructure to connect remote regions that lack a physical banking footprint. Individuals and small-scale businesses across remote rural regions rely on mobile money and digital wallets alone to fulfill their financial needs.

The significance of these fintech solutions

can be gauged from the fact that Mobilink Bank’s mobile money platform, JazzCash alone, operates with a nationwide network of nearly 250,000 agents and serves more than 44 million account holders, of which nearly 30 percent are women. Women also hold 15 percent of the share in its overall deposit base, which stands at PKR 64.6 billion in total. In the first quarter of 2024, JazzCash facilitated more than 560 million transactions valued at more than PKR 2.4 Trillion at a daily rate of 6 million, with an average transaction valued at PKR 4,288.

“With enhanced democratization of digital technology, affordable smartphones, and internet, we can swiftly close the existing gaps in financial inclusion,” Haaris states, “Digital wallets can bring the entire bank to your mobile phone. It doesn’t matter if you are based in Khunjerab or Karachi as long as you have a smartphone and an active internet connection. It benefits individual users and small and medium enterprises looking to make necessary transactions like sending or receiving payments, paying utility bills, or recharging their mobile phones,” he said.

Digital financial services are particularly useful for Pakistani women, a majority of whom have limited mobility for cultural considerations, and giving them access to smartphones and the internet will open up a plethora of growth opportunities.

“Women in Pakistan are an underserved yet highly influential segment with immense growth potential. They await their moment, which probably awaits a digital conduit to be delivered,” Haaris concludes. “It is up to the government, stakeholders, and digital and financial players to help marry the talent with the opportunity to transform the future of this country.” n

Babar Azam is the premier brand ambassador for an English sports manufacturer.

One of the leading sports good manufacturers of the country is locked in a bittersweet quandary