The latest visit of Aurangzeb to the US clears up his role as the finance minister, but who will do his actual job

By Shahnawaz AliEveryone knew that the finance ministry was going to be the toughest ministry in the upcoming term, when the government was naming its cabinet. With all the climbing debt and interest rates, an everlasting balance of payments crisis and shortage of dollars, the ministries toughest days were ahead of it. Any party who would have hence formed the government would have had to deal with tough circumstances. What has since unfolded is the unlikeliest of plans.

The PMLN has come up with a peculiar way of dealing with the country’s finances. On one hand they have the qualified, experienced and well-reputed banker, who gave up his overseas citizenship to be at the helm of the financial management team. While on the other hand they have the finance ministry veteran, Ishaq Dar.

Taking up the Finance Minister office, Aurangzeb had high hopes, however, he saw himself immediately sidelined from all the major decision making committees of the internal finances of the country. The media was quick to question what his role was going

to be as the finance minister, but that question remained unanswered, up until now. On his recent mission to the United States, the picture has become somewhat clearer.

Running a bank is not akin to running a country. The rules of public finance and corporate finance are like night and day. It is not that Pakistan has always had the precise experts running the ministry anyway but banking-for-profit is as far from public finance management as can be. Why then, would Shehbaz Sharif choose someone like Aurangzeb to be the finance minister.

The answer lies in his banking abilities.

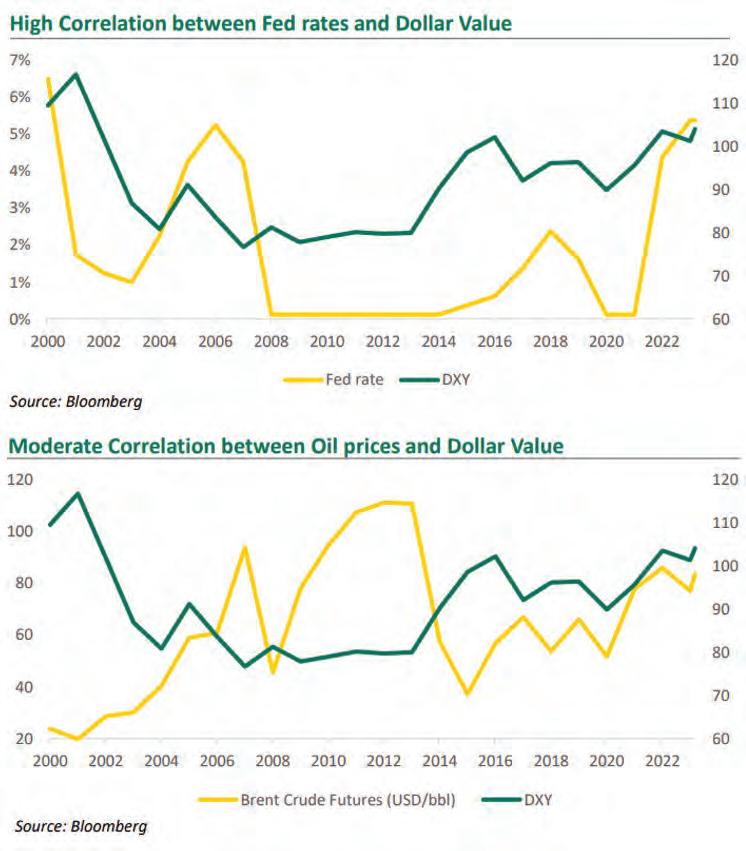

We expect minimal devaluation of the rupee following talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). solid foreign exchange reserves, a stable currency, rising remittances, and steady exports, I don’t see the need for any step change. The only thing which can be a wild card, although in our projections we should be okay, is the oil price

Muhammad Aurangzeb, finance minister

The banker may not be the ideal candidate for managing the rifts between province and centre, or designing poverty alleviation budgets.

But one thing that his recent visit to DC has shown is that he is no stranger to stakeholder management. And why would he be? With the wealth of experience that he has at his disposal, not only in Pakistani banks but also some of the biggest international banks, he is right at home dealing with important stakeholders. That is, apparently, what M Aurangzeb’s role has been reduced to as the finance minister.

It has been common knowledge that Pakistan wants to enter another IMF program, if it is to avoid another default scare. And that was exactly the task that Muhammad Aurangzeb diligently took on. The veteran banker landed in DC for a week full of meetings on Monday.

As of now, Muhammad Aurangzeb has already held a meeting with the WB chief, the IMF chief along with members of the IMF board. He has also met the chief of the Asian Development Bank and has also had the chance to meet the US state department’s infamous Assistant Secretary, Donald Lu.

In all of these meetings, Aurangzeb has been reported touting a “reform agenda”. In his meeting with the IMF Mr Aurangzeb “underscored aggressive reforms, including broadening the tax net, privatising loss-making SOEs, expanding social safety nets and facilitating the private sector,” his team said in a statement issued a day after the meeting.

None of these reforms are new and as apparent by the detailed coverage of these topics in the media, none of them have a high likelihood of being reformed or resolved in the ongoing finance ministry’s term.

What then is the Finance Minister talking about. In his meeting with the IMF, Aurangzeb also mentioned the implications of geo-economic fragmentation on Pakistan and

expressed gratitude to the IMF, multilateral development banks, and “time-tested sincere bilateral partners” for their unwavering support during trying times.

While Pakistan has always had political affiliations with the global north when it comes to global disputes, the recent language coming out of the finance and foreign ministry both indicate that the current government is leaning towards International Financial Institutions (IFIs) such as the IMF and the World Bank, and in turn the US and its affiliates in Saudi Arabia to rescue it from the storm this time.

As the birthing ground and the largest contributor, the United States’ foreign policy is always believed to have some involvement in the decisions of the IFIs. It is also important to note here that in Pakistan’s most recent balance of payments crises, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE made their aid to Pakistan conditional upon an approval from the IMF.

To kill two birds with one stone, Aurangzeb’s visit to America and his meetings with the State Department and IFIs aim to ensure Pakistan’s chances at an IMF program. But Profit’s latest coverage indicates that only an IMF program still might not be enough, what is the finance ministry doing about that?

It seems as though the finance minister has been assigned one mission only. The mission is to secure the country’s external account. With vast resources in the private market up his sleeve and a wealth of experience dealing with multilateral institutions, he is more than equipped to do so.

So then who is left to deal with the economy at home? Who is responsible for bringing in newer investments? And is that person equipped to deal with a problem of this magnitude?

In the books of PMLN, there could be only one answer to who runs the domestic economy while Aurangzeb runs the show around the world? And

that is “Ishaq Dar”. His love affair with a strong rupee has landed Ishaq Dar in quite a bit of trouble in the past. But just as in any love story, Ishaq Dar has found his own way to manage the rupee, even if it is not in the finance minister’s chair.

Just last week, news reports claimed promised gains in the rupee’s value in the coming months. Of course this could be achieved fundamentally over the course of PMLN’s term in office, provided Aurangzeb’s reforms agenda is put into practice on an immediate basis. However, if it was to be achieved in the coming months, the whole ordeal would reek of Ishaq Dar and his Daronomics.

Another interesting aspect of the current economic plan of the PMLN is that the shots are not just theirs to call. Under the new domestic finance regime, overlooked by the SIFC, responsibilities have to be shared.

Ishaq Dar, however, remains the focal person. Being the foreign minister of Pakistan, Ishaq Dar has already met the Saudi foreign minister and the Emirati Energy minister. The meetings may be diplomatic in nature, but Ishaq Dar, famously is not.

That is one of the reasons why the topic statements of not only Ishaq Dar’s meetings with the Arabs, but also the SIFC’s communication has been investment opportunities and its facilitation on Pakistan’s part.

It can hence be noted that while Aurangzeb holds down the fort at the offices of multilateral institutions, Ishaq Dar gears up to kickstart the domestic economic activity.

Of course a peculiar plan like this comes with a cost. The cost of these shenanigans, in this case, is Ishaq Dar’s primary job in the foreign ministry, but also policy continuity in the Q-block. Should the foreign minister be calling shots on key economic decisions? And more importantly, should the finance minister actually be shunned out of that decision making process? n

SUZUKI PAKISTAN IS ALL SET TO BE DELISTED AS DANKA FINALLY SELLS HIS VETO SHARES.

A BIG LOCAL SHAREHOLDER WAS IN A MEXICAN STANDOFF WITH SUZUKI PAKISTAN’S JAPANESE OWNERS. WHO FLINCHED FIRST?

Our story starts in a land far far away. In a boardroom more than 7000 kilometers away from Karachi, it was decided that Suzuki Pakistan would delist from the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) and no longer remain a public company.

The decision was a harsh one. But it simply came down to the dollars and cents. For the past four years, Suzuki Pakistan had been making significant losses. The losses weren’t necessarily indicative of any failing on the part of Suzuki. The automotive industry in Pakistan had seen a nosedive off the back of rising interest rates and auto-loans going bad in big numbers.

For the executives over the Suzuki HQ in Japan, there are over 200 countries that they need to look into. At the time, Suzuki Motor Company Japan held 73.1% shares in Suzuki Pakistan. But to delist they had to acquire at least 90% of the company and could only then take themselves off the PSX.

This meant a buyback. And that is where things get dicey. From the moment that the announcement came, Suzuki Pakistan’s stock shot upwards. The stock had been hovering at around Rs 136 and rose all the way to Rs 900. In response, Suzuki Japan said it would set the minimum share price at Rs 406. But the final price for a buyback was to be determined by the PSX, which went on to set it at Rs 609.

This was a pretty sweet deal. For anyone that had Suzuki stock before the announcement was made could sell it off at a near 500% increase. Ideally, this would have been a nice simple buyback where minority shareholders would get a neat sum and walk away. But in the middle of this buyback something happened. One of the minority shareholders, Nadeem Nisar, announced in the middle of the buyback that he had now acquired more than 10% of the stock. This meant Suzuki Japan could not do anything without his cooperation and would either have to strike a deal or go for a fresh buyback attempt. Over the months the Mexican Standoff between Suzuki Japan and Nadeem Nisar went on and on. Now, it seems Mr Nisar has sold his holdings to the company. This move signifies that Pak Suzuki will now meet the minimum 90% threshold required for the buyback to be successful. What this also implies is that Nisar may have successfully influenced the company, given the mounting pressures on Pak Suzuki to conclude the buyback before the specified deadline of April 21.

But what went on behind the scenes of this buyback, and how did it affect shareholders aside from Nadeem Nisar?

The saga started in October 2023 when Suzuki Motor Corporation, the parent company of Pak Suzuki, resolved to buy back their shares from the local bourse. The reasons given for this move were that they felt the company was facing losses and wanted to give an exit to investors who had invested their hard earned earnings into the company. The whole episode has been covered extensively in the past by Profit.

This announcement was greeted with a rally in the stock price as it soared to Rs 900. The market felt the company was worth much more due to their dominance in the small car category. The company boasted a 55% market share in the category.

Also read: Impasse persists in stalemate over Suzuki’s delisting

In order to carry out the buyback, the company felt that a price of Rs 406 was justified as it was 4 times the price that was prevailing in the market when the buyback was announced. Market participants disagreed with this notion as they felt the price should be much higher. In this moment of chaos, the Pakistan Stock Exchange had the final say and they stated that the final price for the buyback was going to be Rs 609. Many would have felt that a price 6 times to what the share price was in October was ample.

Also read: Pak Suzuki: things are not all they seem to be

Seeing that the matters would be decided and agreed upon without their input, minority shareholders, led by Nadeem Nisar, started to accumulate a position in the stock and passed the threshold of 10% shareholding. As per the applicable law, for a buyback to be successful, Pak Suzuki would need to hold 90% of its shareholding.

This meant that as long as the minority shareholders stayed together as a block, the buyback would fail and Pak Suzuki would have to offer a better price in order to exit the market. As the minority shareholders came together, they saw that they had a collective holding of 15.39% which means Pak Suzuki has to at least buy 5.39% of shares from these minority shareholders.

As a deadlock had been created, a media war began where Pak Suzuki decided to stick to their guns while minority shareholders decided to go after the company. At one end was Pak Suzuki which was looking to steamroll through the formal delisting and buyback process while on the other, were the minority shareholders looking to put any pressure in order to make the management bow down to their demands.

The minority shareholders alleged that the Japanese company had siphoned off billions from its Pakistani subsidiary which

would rationalize the lower buyback price that was going to be quoted. By using price mechanisms like transfer pricing, discounts, commissions, technical fee and royalties, much of the revenue generated by Pak Suzuki was already being transferred to Japan. Due to this, Pak Suzuki was valued much lower than what it should have been. The basic fact was that the minority shareholders were not going to bow down either.

With the validity of the buyback offer expiring on April 21, it seemed like unless some compromise is reached, the buyback would fail as the price quoted by the stock exchange cannot be revised according to its own laws and a new buyback would have to be carried out in order to allow the shares to be delisted.

This, however, is all old news. So what’s the latest development? It appears that Pak Suzuki’s persistence has paid off, but not without a considerable amount of drama surrounding its financial results and a data breach.

On the 8th of April 2024, Pak Suzuki released its annual report and by the looks of it, the company has suffered a huge loss. The company suffered its worst year yet as it made a net loss of Rs 10 billion or a loss per share of Rs 122. This is the worst performance the company has seen since it was listed on the stock exchange. The previous worst results were losses of Rs 6 billion or per share loss of Rs 77 that the company had suffered in 2022.

It comes as no surprise that the company was not able to turn around its bottom line, considering the previous year’s trend of cars becoming less affordable and the challenges faced by automobile manufacturers due to currency devaluation and plant closures resulting from weak demand.

But when a closer analysis is carried out, it can be seen that the recent quarter results are against the run of play. In short, the results should have been better.

After the end of last financial year in 2022, the company recorded a finance cost of Rs 11 billion which was contributed to markup on late delivery, demurrage charges and exchange losses.

Imports being banned, late delivery of vehicles, increasing interest rates and currency depreciation meant that these costs faced by the company increased to Rs 11 billion. For context, financial charges were less than Rs 1 billion during 2021. In 2022, rupee had depreciated by 27.2% against the dollar hitting a high of 226.5 per dollar at the end of 2022.

In the first quarter of 2023, the rupee further depreciated by 25.4% against the dollar and hit a high of Rs 284 per dollar. This led to a

further exchange loss of Rs 13 billion that was suffered by the company. This translated into a quarter end loss of Rs 13 billion. At this juncture, it seemed things were going to persist and the company was heading towards a similar fate due to factors outside its control.

However, the trend changed and results at the end of June pointed towards a better quarter. As the rupee started to stabilize, it was thought that the worst of its losses had been booked and Pak Suzuki would be able to earn better profits going forward.

At the end of June, gross profits were around Rs 2 billion and the company actually made an exchange gain of Rs 3.5 billion which led to profit after taxation to be around Rs 4.5 billion. There were signs that things were going to get better in the next few quarters.

And these expectations were seen to be real when the company was able to boost its gross profits to Rs 4.2 billion in the third quarter ending in September, leading to profits of Rs 3.8 billion. Due to amazing two previous quarters, the company was able to claw back some of the losses it had made till March 2023 and the loss per share for the 9 months ended stood at 71 which had been 157 at their highest point. With things on the up, it could be expected that the December end results and the results for the year would rebound and results of 2022 would be beaten.

Alas, this did not happen.

Even though the company was able to improve its gross profits from Rs 4.2 billion in the third quarter to Rs 8.9 billion in the last quarter of 2023, the company still ended up in the red with a loss of Rs 10 billion. But why was it that a company which was seeing better results ended up making a bigger loss than it had made last year with stellar quarterly results?

In order to understand this, a fine comb approach needs to be taken. Specifically, over some of the expenses which have jumped where they had not even been recorded in the past. In 2023, two major expenses that had been recognised by the company were provision for doubtful advances and provision for onerous contracts which amounted to Rs 1.9 billion.

The provisions were recorded because a planned new car model had to be discontinued due to low demand. This led the management to provide for the irrecoverability of advance payments made to suppliers for raw materials. Additionally, provision for onerous contracts was booked to account for potential losses claimed by the suppliers due to Pak Suzuki’s inability to fulfill the contract.

Both these expenses should be taking place in a normal course of business. What raises a few eyebrows is the fact that no such expenses have been recorded by the company

in the last 10 years atleast and suddenly an amount of Rs 2 billion is set aside from the profits for these two expenses. It boggles the mind that an expense was not recorded for such a long time and then suddenly a quarter of the gross profits are wiped off and expensed in one go. These provisions are by discretion of the management and are approved by the auditors once they are rationalized by the company to the auditors.

After considering the provisions being set aside, the company still saw a profit before tax of Rs 4 billion for the quarter ended December 2023. This shows that much of the gross profits was seen in the form of profit before tax and earned by the company.

The next item which has increased in terms of the expenses is the taxation expense. Till 2022, the company was paying out taxes worth Rs 3 billion even when it had not earned a profit. This is due to the tax code developed where taxation is charged on the turnover or sales of the company in case the profits are below a certain threshold.

Taxation accounting is a dark art where the company determines their taxation amount and then pays it off. When additional wrinkles of turnover tax, supertax, custom and duties are added, it is difficult for a company to track how much tax it owes and how much tax it needs to give.

Due to this, there is some estimation used by the company on a yearly basis. In some years, it will end up paying a higher tax and in some it will pay a lower one. For years where it pays a higher tax than it was supposed to, the company will recognize a tax asset as it has paid an amount higher than expected and will yield benefit from it in the future. This is referred to as deferred tax assets.

Something similar had happened at Pak Suzuki. Over the course of 12 years, the company had slowly accumulated a deferred tax asset which had grown to Rs 7.3 billion.

The deferred tax assets are created based on the expectation that the company would be able to generate sufficient profitability in the future to utilize these accumulated tax benefits.

However, in 2023, the company felt that all the tax assets it had accumulated amounting to Rs 7.3 billion were not sustainable based on their profitability expectations and were written off. To give some context to this figure, the total assets of the company stand at Rs 21 billion at the end of 2023. If these tax assets had still existed, these assets would have been worth Rs 28 billion.

The company wiped away a quarter of its assets with a stroke of a pen. As these assets were taken away, the profits of the company were also decreased and an expense of Rs 7.3 billion was recorded.

The reason given for transferring the assets and writing them off was that there was a reduction in sales volume caused by high inflation, interest rate and exchange rates. As the company needs to pay off its tax liabilities in turnover tax, these assets were deemed redundant.

All these provisions are created based on the discretion of the management and their expectation and the auditors have the task of scrutinizing these assumptions of the management when they audit the accounts.

In its audit report, AF Ferguson discussed the fact that the writing off of the deferred tax asset was a key audit matter indicating that it indeed required special attention during the audit process.

The report states that, “The Company has carried out an assessment to determine the recoverability of deductible temporary differences as at December 31, 2023 by estimating future taxable profits of the Company and the expected tax rate applicable to those profits. The determination of the future taxable profits is most sensitive to certain key assumptions such as sales volume, contribution margins, fixed overheads, inflation and exchange rates etc which have been considered in that determination. As a result of this exercise, the deferred tax asset amounting to Rs 7,345 million carried forwarded as at January 1, 2023 has been completely charged off to profit or loss for the year.”

The auditors also state that, “The management is of the view that this is owing to significant reduction in sales volume on account of high inflation, interest rate and exchange rate parity. Due to this in the foreseeable future the Company’s tax liability shall be based on turnover tax and the Company shall be unable to utilize the deductible temporary differences. As estimating future taxable profits require significant management judgment, we considered this to be a key audit matter.”

The auditors determined the importance of this issue and then carried out a thorough audit of this matter by making sure that the assumptions were correct and that the tax rates being applied were according to the tax legislation applicable on the company.

Accountants have their hands tied to an extent as the management is allowed to make judgments, estimates and assumptions that have an impact on the assets, liabilities, income and expenses being recorded in the financial statements. A management can make these estimates and assumptions based on past experience and factors that allow it to use their discretion.

Actual results may differ from these estimates. The estimates and underlying assumptions are reviewed as an ongoing basis. These provisions can also be reversed in the future if

the management feels that the underlying factors have changed. Just like the tax assets were created in the past and then written off, these assets can be recognized again in the future with the approval of the accountants.

In case these provisions had not been written off, the company would have made a loss of less than Rs 1 billion which would have translated to a per share loss of Rs 12. This considers only the turnover tax that the company would have had to pay and adds back the writing off of deferred tax assets and the provisions being made for onerous contracts and doubtful advances.

While we are not insinuating that Pak Suzuki has violated any legal regulations or engaged in creative accounting, the company’s current circumstances, the delisting process, and the need to persuade a group of minority shareholders create fertile ground for conjecture regarding the reasoning behind the provisions recorded that led to a record net loss, especially considering the novelty of these measures.

As one tax expert explained to Profit, there is nothing in the accounting standards that stops management from making an estimate as far as they have the proper justification ( which may be appropriately provided in the FS). An auditor just needs to go over the estimates for their rationality and it shouldn’t be a problem. Estimates can change year to year. So on the face of it these don’t seem a problem since Suzuki is already delisting. What might be a problem, however, is that they charged it off because they don’t believe they will be profitable in the future (deferred tax is recognized only where future profits are available to set it off later) But as per note 1.5 of the company’s financial statement it says the company will be profitable in the next year.

call and proposed Rs 609 per share. Seeing that the matters would be decided and agreed upon without their input, minority shareholders, led by Nadeem Nisar, started to accumulate a position in the stock and passed the threshold of 10% shareholding.

The deadlock continued with the last date of completing the buyback, 21st April, fast approaching. In the meantime, The company wiped away a quarter of its assets with a stroke of a pen reducing its value and making the situation tricky for minority shareholders.

In the wake of this, the battle was very finely balanced. On the one hand there was Nadeem Nisar. He was unwilling to sell at Rs 604 because the average price at which he got to the 10% was likely higher than this. Otherwise why would he simply not sell? But

shareholders will be chuffed by the outcome. If the buyback had been called off a lot of people would have lost their money. But even if Nadeem Nisar sold it at a higher price, at most some shareholders might be a bit annoyed. In any case, other than the people that would have bought stocks at over Rs 604 due to the frenzy, everybody will have walked away happy.

The recent developments at Pak Suzuki in the last few weeks seem to be a sequence of unfortunate circumstances. It remains unclear whether these events were orchestrated or unfolded naturally. However, it is evident that the situation affected the minority sharehold-

So here is the situation. Suzuki announced a buyback for delisting. Their share price surged to Rs 900 as the market was bullish on Pak Suzuki. The company proposed a buyback price of Rs 406 as per its own valuer’s report. PSX had the final

Suzuki had a card up their sleeve too. They could simply call off the buyback and the price of the share would come crashing down to the Rs 136 level it was at before the announcement. Anyone that had bought shares in the frenzy, in particular the group of investors led by Nadeem Nisar, could have their investment tank in a matter of minutes. So what middle ground would they reach?

The exact details of what is likely an off-market deal are difficult to understand but it seems Nadeem Nisar has struck a deal right in the nick of the 21st April deadline and sold off his holding. Did he sell it at over the average price at which he acquired the stock or did he sell it at less and simply try to cut his losses? That is not clear yet. But in any case, minority

ers, ultimately prompting them to capitulate. According to market sources, Nadeem Nisar, who held a 10% stake in Pak Suzuki and led the group of minority shareholders, has reportedly sold his holdings to the company. This move signifies that Pak Suzuki will now meet the minimum 90% threshold required for the buyback to be successful. What this also implies is that Nisar may have successfully influenced the company, given the mounting pressures on Pak Suzuki to conclude the buyback before the specified deadline of April 21. This situation may have left other minority shareholders with limited leverage compared to Nisar. While specifics of the transaction remain undisclosed, it seems to mark the end of Suzuki’s buyback saga. n

How the building of Lucky One Mall became a case study in the mistreatment of minority shareholders

Minority shareholders have no one looking out for them. Case in point, the Lucky One Mall

By Zain NaeemMinority shareholders are sometimes treated like step children in the capital markets. They are constantly ignored and are seen as being a necessary evil that has to coexist. Due to this, they have little to no voice in the corporate corridors while the regulators have few tools to resolve their issues.

A classic case of this mistreatment can be seen taking place in 2014. The Board of Directors of Fazal Textile Mills decided to sell off the Lucky One project it was undertaking. What followed can form a case study on the way minority shareholders are treated and how there is little to no regard for their rights in the corporate landscape of the country.

Editor’s Note: Profit tried relentlessly to contact any representative at the Lucky Group to reply regarding this story and questions in relation to them, however, no comments were given. This is an open invitation for anyone to come forward from the group to reply regarding this story and set the facts straight.

Let’s start from the beginning and get some facts straight. The company was one of the top spinning mills that was set up by the Lucky Group in 1962 and

was involved in production of cotton ring spun yarn on state-of-the-art machinery.

At this point in time, it is important to note that the company was primarily held by Y.B. Holdings, an associate company, which held 74.05% of the shares while the directors of the company held 18.49%. This constitutes to around 92.54% of the total shareholding leaving 7.46% shares in the hands of outside investors.

The production facility of the company was located on Plot No LA-2/B, Block 21, F.B. Area, Rashid Minhas Road. As the city of Karachi spread outwards, the production facility went from the outskirts of the city to becoming a part of it. Now that the boring part is out of the way, let’s get to the juicy part.

The company, in its Annual General Meeting (AGM) held on 8th October 2008, decided to establish a new production facility and move it towards the Super Highway, Nooriabad. What was going to happen to its existing facility? Well, as the piece of land was high in value and closer to the city, it was decided to construct a mega mall and luxurious residential towers. The existing factory was going to be scrapped.

This was going to be labelled as Lucky One Mall Project and was going to be a joint venture between Lucky Textile Mills and Fazal Textile Mills. As the company had little to no expertise in setting up such a large scale project, both companies decided to create an Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) which would be tasked

with construction, development and maintenance of the project. This led to the establishment of Lucky One (Private) Limited. This was carried out after approval from shareholders in August of 2010.

October 2008: Fazal Textiles and its shareholders decide to set up a mall in its existing production facility and move its operations to Nooriabad.

August 2010: All formalities are put into place and Lucky One Mall starts being built by Fazal Textiles and Lucky Landmark

September 2014: The shareholders of Lucky Landmark and Fazal Textiles decide to break Fazal Textile Mills by merging the Lucky One Project with Lucky Landmark (Private) Limited and the textile business of Fazal is merged with Gadoon Textiles Limited. This would lead to the Fazal Textiles being dissolved.

Does this raise any red flag yet? Well, it should. The fact of the matter is that a textile company is deciding to venture into real estate development. The shareholders who invested their money in the company seeing its stable performance were now being asked to have their investment diverged into a real estate business. It is true that shareholders get to vote the decision and approve it in the AGM, however, with a measly

shareholding of less than 10 percent, it is obvious what will come to pass.

Which it did.

The only course of action available to the shareholders at this point is to vote through their cheque book and sell their shares as their actual vote in the AGM is symbolic at this stage. The only bright spot for them at this juncture is the fact that there can be investors who are willing to invest in a company expanding into the real estate business.

Even for someone who is willing to invest in such a company, what was going to be the mechanics of setting up the project?

The project was going to be set up on the existing freehold land that the company already owned and for all the expenditure carried out, the company was going to create an asset in its own accounts classified as construction cost of the project. When the project started, the freehold land held by the company was worth around Rs. 6.6 million which included both the land for the project and the one held at Nooriabad for the new factory.

As the project developed, Fazal Textile Mill funded the project and even showed an increase in the freehold land as it increased in value due to the development work taking place. By the end of 2014, the freehold land stood at Rs. 545 million while the expenses carried out for the project were around Rs. 2.3 billion. So what happened in 2014?

On September 24th 2014, it was decided by the board members of Lucky Landmark (Private) Limited and Fazal to essentially do two things. On one hand, the real estate project of Lucky One was demerged from Fazal and merged with Lucky Landmark and secondly, the remaining assets of Fazal were absorbed by Gadoon Textile Mills. Gadoon is another company operating under the umbrella of Lucky Group since 1988.

The rationale for this move was given that as Fazal had little expertise in real estate, the company should be broken into two parts. The real estate project should be taken over by Lucky Landmark (Private) Limited while the assets related to textile should be absorbed by Gadoon. On the face of it, the transaction seems simple and might even look lucrative to investors. What is actually happening here?

Even though the transaction should make sense, there is a lack of regard or concern of the minority shareholders yet again. As we saw previously, the deci-

sion to invest in the real estate project had little to do with the interest of the minority shareholders. It seems like the same was happening over here as well. The decision to demerge the project from the company was taking place with what can be seen as arm twisting by the majority shareholders to comply with the will of the Lucky Group again. The formality of an AGM would be held and the resolution would pass yet again.

Consider an investor who had bought the shares of the company after 2008 expecting the Lucky One project to prove profitable for the company. With a stroke of a pen, they would lose their investment in the project and it would be given over to Lucky Landmark. The investment which would have seemed attractive in 2008 would be snatched away from them before they get to reap any benefits.

Again the best course of action available would have been to sell the shares and recoup their investment by selling the shares to someone else in the market. The regulators can do little to change the situation as laws on the books are not designed in the interest of the minority shareholders in the first place. The only step that can be taken is to approach the courts.

It seems that the minority shareholders would not be able to raise their concerns at any platform when the corporate sector is willing to act in their own interest. And things get worse from here. Much worse.

As the demerger was announced, it was obvious that Fazal would cease to exist as it would be merged with Gadoon. This cannot take place without compensation being given out to the current shareholders of Fazal. In such a case, it was decided to give out shares of Gadoon and Lucky Landmark as compensation to the investors who owned the shares of Fazal.

It would seem like a fair way to be compensated as investors would still have an interest in the Lucky One Project by being given ownership of shares in Lucky Landmark and in Gadoon as their investment has been broken and given to these two companies. To value the compensation to be given out, the valuation of assets and liabilities of Fazal needs to be carried out.

Can you hear that maniacal laughter in the background?

Well read on to find out why.

As explained earlier, two separate divisions were carved out from the existing operations of Fazal. The first division is focused on the Real Estate

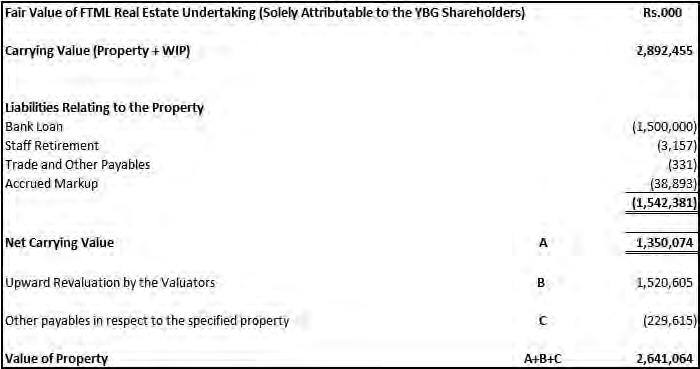

segment, which included the company’s land holdings that were to be transferred to Lucky Landmark. The valuation of this division relied on the fair value of the land determined by a valuator, while the liabilities associated with the real estate division were recorded at book value.

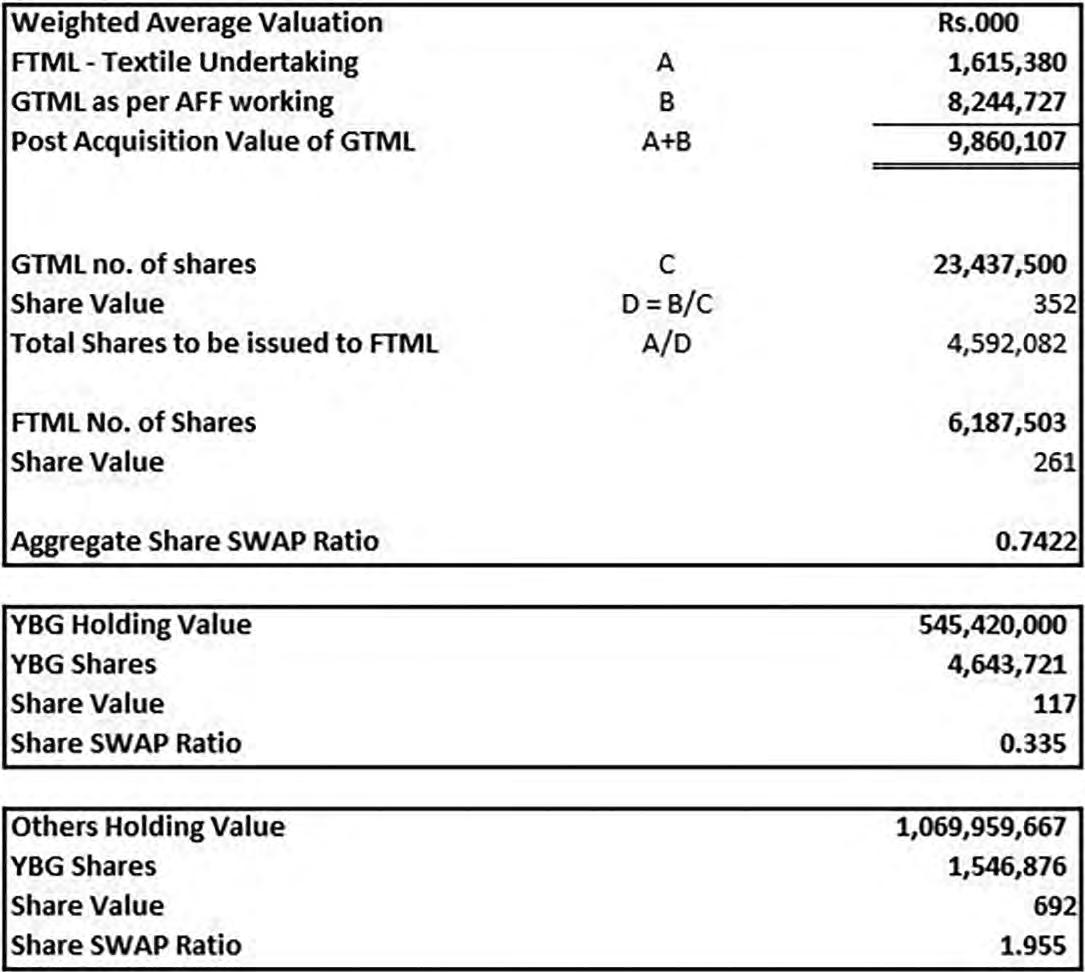

The second division encompassed the textile operations. The valuation of this division was determined by taking the weighted average results of three methods: Discounted Cash Flows (DCF), Net Assets (NA), and Market Capitalization. This division was amalgamated into Gadoon Textile.

DCF Valuations were based on the projected future cash flows prepared by the management of the company. These were discounted using an appropriate discount rate reflecting the economic, business and financial risk.

NA Valuations were based on the carrying values of assets and liabilities as per the portion of balance sheet attributed to the textile operations. The carrying values were adjusted for the fair valuation of items of property. plant and equipment based on the fair valuations carried out by the valuator.

Market Cap valuations are based on the weighted average market price of the equity shares of Fazl textile over a period of three calendar months prior to and up to the valuation date at all the stock exchanges where these are listed, based on the data reported by these stock exchanges at their web-sites, with adjustment for the value of the real estate division determined as mentioned above.

Initially it was seen that as Fazal owned the piece of land, it was its own ownership and the valuation was recorded on its initial cost. Seeing the accounts, an area of 3.4 million square feet was valued at around Rs. 6.6 million which comes to around Rs. 2/sq ft. This seems low for the land that should cost much more than that. Why was that the case?

Well accounting standards dictate that assets should be valued at cost throughout the life of the asset. If there is a change in value, they need to be accounted for in other areas. This is why the land was valued at such a low cost by the company. But when the assets were being transferred, it was seen that Lucky Landmark transferred the cost of the land into its own accounts. Effectively, it seems like the land was “bought” or “taken over” at cost.

When the transfer of assets was carried out from Fazal to Landmark, the construction cost that had already been incurred by Fazal of around Rs. 2.6 billion was transferred with property of Rs. 0.5 billion transferred as well.

This leads to the assets of the company being valued at around Rs. 3.1 billion. This fails to take into account the value of the actual land

which should have been transferred to Landmark. With liabilities of Rs. 1.7 billion that were owed, the net assets of the company came to around Rs. 1.4 billion which was to be paid as consideration by Landmark to Fazal. The land valuation and transfer was allowed to take place at its cost which is highly skewed.

How was this allowed to happen? Well, dear reader, you have reached where we were at the start of this story.

In simple words, this was a travesty. Fazal was being short changed as its land was not being given the true value at which it should have been valued at. If an outside concern was going to buy this land, they would have done so at the market value rather than the book value and considering that the book value was being used from 1962 only amplifies the unfair way Fazal has been treated. It seems like Lucky Group found a new way to disadvantage the shareholders of the company. In essence, the shareholders of Fazal are being disadvantaged as they are not getting the true value of their investment in the first place. If the land was transferred at the right price, less than 10% of the minority shareholders would have gotten a fair compensation on their investment.

Even when the compensation was given, it seems Lucky Group took a leaf out of George Orwell by creating a category of shareholders more equal than others. They did so by creating two categories of shareholders of Fazal. With a holding of more than 90%, the Yunus Brother Group (YBG) was made one category of shareholders while the other shareholders were kept separately.

What was the need for such a classification? Have a guess.

The rationale given by the company was that the real estate business was going to be separated and so Yunus Brothers would be given 2.9146 shares of Lucky Landmark for every share of Fazal that they held. Lucky Landmark was a privately held company and in order to keep their shareholding private, they were going to get shares of Lucky Landmark in exchange for their investment. In addition to that, they would only get 0.3347 shares of Gadoon in exchange for their ownership.

The other shareholders were only going to get a share in the textile assets of the company and were prescribed a ratio of 1.9555 shares of Gadoon for every share they held of Fazal. The swap ratio determined by the board was based on the fact that as the Yunus Brothers shareholders were getting all the stake in Lucky Landmark and the Lucky One Project, they could have less shares in the swap ratio as compared to the other shareholders.

Yunus Brothers was doing this all out of the goodness of their heart. Irony be damned.

(Figures are rounded to the nearest whole number)

In order to gain an understanding regarding the swap ratio decided by AF Fergusson, it is vital to understand that they separated the two business, real estate and textile, into two separate entities. The land and the capital work in progress was valued at Rs. 2.9 billion from which a total of Rs 1.5 billion was subtracted attributable to liabilities and debt owed by the project.

This left net assets of Rs. 1.3 billion which were transferred to the company. After revalu-

ing the project, an additional Rs. 1.3 billion was added and the final value of the property was considered to be Rs. 2.6 billion in total.

As there are few disclosures, it is difficult to understand whether this amount accounted for any additional or revaluation of land and what was the magnitude of that. It is important to note here that any revaluation would have gone to Yunus Brothers Group solely as they were the ones benefiting from the revaluation and swap that took place subsequently.

The valuation of the textile factory was different. It is the task of the valuator to determine the value of the assets on three metrics. The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method, the net

(Figures are rounded to the nearest whole number)

asset valuation and the market cap valuations. The market cap is considered the upper limit while the net assets is considered the lowest or lower threshold. It is the task of the evaluator to take the weighted average of these three metrics in order to determine a more realistic value.

The valuator had also divided the company in terms of its valuation as almost 75 percent of the assets went to Yunus Brother Group while they owned 92 percent of the company and 25 percent went to other shareholders who held 7 percent of the company.

Once the valuation has been carried out, the last step is to determine the swap ratios to see how many of the shares will be given to investors of Gadoon and Lucky Landmark.

Based on the valuations, the swap ratio of Gadoon Textile shares given to Yunus Brothers Group and Other shareholders is determined and given out.

What did it really mean for the shareholders?

In order to see whether the swap was justified for the investors in the Yunus Brothers Group and other shareholders, we can consider that Gadoon and Fazal were listed companies while Lucky Landmark was unlisted. As Lucky Landmark is an unlisted, private limited company, an approximation can be taken of its book value at June end of 2014 which comes to around Rs. 101.15 per share.

The calculations that had been carried out by the consultants, AF Ferguson and Co., were based on the values at the end of June 2014. As those prices are considered, it was seen that Fazal was trading at Rs. 800 while Gadoon was trading at Rs. 250. Based on those figures, the Yunus Brothers Group shareholders got 291.46 in Lucky Landmark and Rs. 83.68 in Gadoon making their investment at Rs. 375.14 while they had invested Rs. 800. This is based on book value which gives an understated value. Their actual return must be much higher.

On the other hand, the other shareholders had an investment of Rs. 800 initially which was converted to 1.9555 shares of Gadoon making their investment worth Rs. 488.88 which is a loss in value almost 40%.

No one ever told you goodness of heart can be heavy on the wallet. The help was going to come from the most unlikely of places. Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP).

Seeing the blatant and open violation of rights of the shareholders, SECP swooped in. Based on the swap ratio announced, the SECP raised an objection to the approval of this consideration. The Joint Registrar

(Figures are rounded to the nearest whole number)

of Companies at SECP, Muhammad Nasir, stated that there was a violation taking place here. The other shareholders of Fazal were not being given shares in Lucky Landmark and the methods used by the consultant had not considered discounted cash flows in their evaluation of the swap ratio in relation to the real estate undertaking.

The SECP also raised the issue that the minority shareholders of Fazal had not been considered in the principal choice of whether they

the right to pass any resolution they please and it is outside the purview of the court to dictate the workings of the company itself.

The most damning line in the judgement is that “it was further observed that the shareholders were best judges of their interest and were better informed with the market trends than the Court.”

This is a stinging rebuke for the rights of the minority shareholders who have to abide

(Figures are rounded to the nearest whole number)

wanted exposure to the real estate project meant that their voice was not heard. SECP filed these responses in the Sindh High Court where they contended that some shareholders were being disadvantaged for the sake of others.

For once the regulator stood up for the common man. Did it work?

The Court observed in this matter that the members or shareholders of the company have

by the majority shareholders to either sell their position or take whatever is being given to them. Even the last resort available to the minority shareholders does not do anything to protect them. The minority shareholder will stay the stepchild of the market. At this point, it is more likely that these Cindrellas will find their Prince Charming at a ball rather than have their voices heard.n

Pakistan’s electric distribution companies desperately need privatisation.

The DISCOs problem has been a major concern for successive governments in recent years. Will a solution ever take shape?

By Ahmad AhmadaniThere has been a lot going on in Pakistan’s electricity distribution infrastructure. For nearly a year now, there has been talk of different solutions to the problem of how power is supplied all over the country. From privatising distribution companies (DISCOs) to handing control of them over to the armed forces, this has been a major focus of successive governments.

Mostly the concern has been because of mounting circular debt and the part that losses incurred by DISCOs have played in this. A report at the start of the year on the subject of State-Owned-Enterprises (SOEs) exposes the shocking truth that Pakistan’s 31 SOEs

across eight sectors have collectively suffered a staggering loss of Rs 730 billion in the fiscal year 2022 alone. The power sector, with losses amounting to Rs 321 billion, stands as the most significant contributor to this financial haemorrhage. The remarkable aspect is that the losses solely originate from one sub-sector — the DISCOs.

The current conversation has come in the wake of a surprising admission of guilt on behalf of the federal government. Admitting the regular overbilling by distribution companies and the power division’s total ignorance about the extent of defective metres, Power Minister Awais Ahmad Khan Leghari on Thursday hinted at reviewing electricity rates for solar, industrial and tribal region consumers to revive plunging electricity demand and counter

rising capacity payments.

Of the many schemes that have been suggested to fix the problem, the latest is the suggestion by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif that there is a need to seek assistance from private sector experts and globally accepted models to improve the management affairs of the DISCOs. In particular the issue under discussion was power theft and how it can be countered. So how exactly does the prime minister plan on fixing the DISCOs issue, and how did the problem get this big in the first place?

The connotation of the word DISCO around the globe is vastly different from its designation in Pakistan. In Pakistan, ever since the 1970s,

Based on my evaluation, it is chiefly because the programme was never executed with resolve, resulting in several crucial deadlines being missed and vital institutions envisaged therein not established in time. In certain cases, we are 40 years too late

it does not conjure up any notion of leisure or entertainment. The only resemblance it bears to its international equivalent is the monetary agony one experiences when they behold the bill. This is because the word ‘DISCO’ is an acronym for Pakistan’s electricity distribution companies.

These are the companies whose name is emblazoned on your electricity bill at the commencement of every month. These are also the companies that we contact when we are deprived of electricity for interminable hours, when there is a malfunction in the wiring, or when our local transformer is defunct, among other things. At this juncture, the name of the DISCO that will have sprung to your mind will vary depending on your location throughout the expanse of Pakistan. There are presently 12, with the newest one emerging only this year, whilst the oldest one tracing its origins to the early 20th century.

The Government of Pakistan’s footprint across the power sector comprises distribution companies (DISCOs), generation companies (GENCOs), management companies, and one transmission company. Of these four sub-sectors, only one has incurred losses. Dissecting the Rs 321 billion in losses reveals that all the aforementioned sub-sectors except the DISCOs jointly generated profits to the tune of Rs 55 billion. The DISCOs, in contrast, dragged down the entire sector with their Rs 376 billion in losses.

It’s crucial to note that the DISCOs under scrutiny are those within the Central Power Purchasing Agency-Guarantee (CPPA-G) system. The report excludes K-Electric and predates the establishment of the Hazara Electric Supply Company. As such, it is limited to the ten based in Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Quetta, Lahore, Islamabad, Sukkur, Multan, and the two nestled in Peshawar. We have previously delved into the nature

of the DISCOs, their genesis, and the reasons behind their debacle. However, to put it succinctly, these are the companies whose names adorn your electricity bill at the commencement of each month. They are also the ones we reach out to when we find ourselves bereft of electricity for interminable hours, when there’s a hiccup in the wiring, or when our local transformer is out of commission.

The DISCOs are all loss-making entities. Not a single DISCO turned a profit in fiscal year 2022. Is this surprising? Not particularly. The DISCOs have generally been loss-making in the three years preceding fiscal year 2022 as well. The Tribal Electric Supply Company stands out as an exception, having achieved profitability from fiscal years 2019 to 2021. Other anomalies include the Faisalabad and Multan Electric Supply Companies, which achieved profitability in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, and the Gujranwala Electric Supply Company, which registered profits in fiscal years 2019 and 2021. From fiscal year 2019 to 2022, the DISCOs have recorded a cumulative loss of Rs 893 billion, with the accumulated loss for the aforementioned DISCOs standing at a staggering Rs 2.1 trillion at the end of fiscal year 2022.

What lies at the heart of the woeful performance of these DISCOs? The answer, in its most distilled form, is their sheer dysfunctionality. However, let us delve into the more elaborate answer.

“Pakistan embarked on involving the private sector in various segments of the electricity supply chain under the auspices and assistance of USAID and World Bank in the 1980s. Although a similar model has been successful in many countries, our experience with it has been abysmal. Based on my evaluation, it is chiefly because the programme was never executed with resolve, resulting

in several crucial deadlines being missed and vital institutions envisaged therein not established in time. In certain cases, we are 40 years too late,” explains Syed Hasnain Haider, a former Chairman of the Faisalabad Electric Supply Company.

“Continued ownership of the various companies by the government has not been advantageous to the sector; in fact, it has proven detrimental. This is evident from the monumental losses, capacity surplus, bottlenecks in transmission lines and distribution systems, scarcity of adequate managerial skills, lack of customer-centric focus, and a poor health and safety record, amongst other issues,” Haider continues.

The National Electric Power Regulatory Authority’s (NEPRA) State of Industry Report for 2022 lends credence to Haider’s assertions and lays bare the grim state of affairs for the DISCOs. In the fiscal year 2022, the average distribution losses for DISCOs stood at 17%, exceeding the permissible limit of 13%. This resulted in a financial repercussion of Rs 113 billion. Furthermore, NEPRA, in its determinations, presumes 100% recoveries by DISCOs against the billed amount to consumers. In reality, the recoveries by DISCOs fall short. In the fiscal year 2022, DISCOs managed to recover a mere 91% against the billed amount, thus incurring a loss of Rs 230 billion.

The Government of Pakistan’s footprint across the power sector comprises distribution companies (DISCOs), generation companies (GENCOs), management companies, and one transmission company. Of these four sub-sectors, only one has incurred losses. Dissecting the Rs 321 billion in losses reveals that all the aforementioned sub-sectors except the DISCOs jointly generated profits to the tune of Rs 55 billion. The DISCOs, in contrast, dragged down the entire sector with their Rs 376 billion in losses.

It’s crucial to note that the DISCOs under scrutiny are those within the Central Power Purchasing Agency-Guarantee (CPPA-G) system. The report excludes K-Electric and predates the establishment of the Hazara Electric Supply Company. As such, it is limited to the ten based in Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Quetta, Lahore, Islamabad, Sukkur, Multan, and the two nestled in Peshawar. We have previously delved into the nature of the DISCOs, their genesis, and the reasons behind their debacle. However, to put it succinctly, these are the companies whose names adorn your electricity bill at the commencement of each month. They are also the ones we reach out to when we find ourselves bereft of electricity for interminable hours, when there’s a hiccup in the wiring, or when our local transformer is out of commission.

The DISCOs are all loss-making entities. Not a single DISCO turned a profit in fiscal year 2022. Is this surprising? Not particularly. The DISCOs have generally been loss-making in the three years preceding fiscal year 2022 as well. The Tribal Electric Supply Company stands out as an exception, having achieved profitability from fiscal years 2019 to 2021. Other anomalies include the Faisalabad and Multan Electric Supply Companies, which achieved profitability in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, and the Gujranwala Electric Supply Company, which registered profits in fiscal years 2019 and 2021. From fiscal year 2019 to 2022, the DISCOs have recorded a cumulative loss of Rs 893 billion, with the accumulated loss for the aforementioned DISCOs standing at a staggering Rs 2.1 trillion at the end of fiscal year 2022.

Back to where we began from. Why have DISCOs been overcharging their customers? In a recent press conference, energy minister Awais Leghari said the distribution companies were losing Rs200bn on account of electricity units they bill but cannot recover, while another Rs360bn worth of units were lost to theft facilitated by “our officers and staff”. “It’s unacceptable,” he said.

So how does it operate? How severe is it? The essence of the matter is that metre readers essentially recorded electricity consumption readings exceeding 30 days and billed them as a 30-day bill. Is this detrimental? It depends.

The DISCOs do overbill due to various reasons — legitimate or otherwise. However, it is usually rectified in the subsequent month. Suppose that you received a bill of 110. If next month your reading is for 200

We have prepared a comprehensive roadmap for reforms in the power sector after thoroughly reviewing the loopholes

Awais Leghari, energy minister

units, then they will adjust it. Therefore, to assert that the DISCOs have overbilled customers to enrich themselves may be erroneous but surely it is done to cultivate poor results. The problem emerges when a customer’s slab is altered, and they are charged a higher rate than they would have otherwise. People who experienced a change in their slab due to the overbilling have been wronged. There is no question about that.

What does all this imply? Let us do some simple arithmetic. At 290 units, an individual’s bill would have amounted to 10,730. If you were to charge them 20 units extra and they fall into the 300 slab, their bill would have soared to Rs 13,330. Because the slab is different up to 300 units. The rate up to 300 units is Rs 37. When it goes above 300, then all the units have to be charged Rs 43. You have directly inflicted a loss of roughly Rs 4,000 on a consumer. So, will the DISCOs be penalised for this error? Unlikely, the Ministry of Energy is currently conducting its own investigation as to the validity of NEPRA’s report. Is NEPRA’s report correct? Likely, but not because NEPRA is very good but because the DISCOs have done this numerous times before.

Afew important things have happened in the last week. On the 17th of April, Minister for Power Division, Sardar Awais Ahmad Khan Leghari on Thursday warned all chief executive officers (CEOs) of power distribution companies (DISCOs) to remove ‘Kunda’ before April 23 failing which strict action would be taken against the responsible officials. Addressing a press conference, Leghari said that the government will ensure strict action against elements involved in power theft. He said concrete steps are being taken to overcome inefficiencies in the power sector which are drastically affecting the economy of the country.

“We have prepared a comprehensive

roadmap for reforms in the power sector after thoroughly reviewing the loopholes,” said Awais Leghari.

Highlighting the gravity of the situation, Leghari revealed alarming statistics, stating that power distribution companies (DISCOs) were facing an accumulative loss projected to reach Rs 560 billion by June. He attributed a significant portion of this loss, over Rs 300 billion, to power pilferers, stressing the urgent need to curb such illegal practices.

That is where the latest directives come in. Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif on Thursday directed the authorities to expedite the pace of privatisation and outsourcing of the power distribution companies (Discos) during a high-level meeting regarding the power sector. Presiding over the meeting, the prime minister emphasised the need to seek assistance from private sector experts and globally accepted models to improve the management affairs of the Discos. He also instructed the preparation and presentation of a comprehensive plan in the next meeting to improve the power system in the country.

He said that reforms in the power sector would contribute to reducing the country’s circular debt. He also pledged not to allow electricity theft and other activities to harm the country’s treasury. During the meeting, recommendations and measures to prevent power theft, reorganise the National Transmission and Dispatch Company, and implement new projects for electricity transmission were presented. The meeting was infomed that the Matiari-Rahim Yar Khan transmission line and Ghazi Barotha-Faisalabad line would be constructed to ensure power transmission from the southern part of the country. The meeting was further informed that a comprehensive strategy had been evolved for the reorganisation of NTDC to reform the power transmission system and to minimise the government’s circular debts. The PM urged the completion of all reform initiatives within the stipulated time. n

The Pakistani rupee has largely been stable in the recent months. But rising oil prices amidst war in the Middle East pose a challenge to currency

By Mariam UmarWe can’t quite track down the first genius that planted this seed, but Pakistani policymakers have long been obsessed with the health of the Rupee. The result has been a consistent pattern in which different governments have tried (and failed) to control the rate of the rupee.

Some of the aversion to letting the rupee settle at its natural rate has to do with an aversion to the basic principles of economics. So rather than improving the balance of trade, governments have tended to force and bully the rupee to adhere to artificial rates that seem good on paper.

The latest saga of trying to wrangle the rupee began somewhere around 2018 when the Imran Khan administration came to power. At the time, the rate of the Rupee was Rs 121 to the dollar. In the six years since the rupee has gone to highs of Rs 310 on the interbank and is currently settled comfortably at just under Rs 280 to the dollar.

So what exactly happened to the rupee in these six years? To cut a very long story short, international pressures such as the Ukraine War and domestic concerns such as an overheating economy and inflation demanded that the rupee weaken. At the same time, a string of finance ministers unwilling to lose political capital for their respective parties demanded that the rupee

stay stable one way or the other. At the same time, currency markets in the country practically imploded, and it took intervention of the entire state machinery to set things back in order.

Now, Pakistan might once again be at a similar crossroads. War is stirring in the Middle East, a contentious American election is to be held in a few months, global oil prices are on the rise, and there is a weak coalition government in Islamabad trying to control inflation. So what will it be this time? Will the rupee hold, and if it doesn’t, will there be someone trying to prop it up again?

This isn’t the first time Profit is covering how the exchange rate functions in Pakistan and all of its many implications.

Back in 2018 when the Imran Khan government had come to power, this publication had prescribed that if the rupee was falling, it should be allowed to crash.

The history of why this might be a good idea goes back to the first time Pakistani policy makers decided the strength of the rupee was some kind of indicator that had to be kept inflated. And it started a long time ago thousands of miles away in a stuffy room in central London.

On September 18, 1949, the Bank of England made a monumental decision that set off a series of events that has permanently reshaped the Pakistani economy. On that day, the British government announced that it would

be devaluing the pound sterling by 30%. In those days, while the US dollar had already taken over as the default currency of global commerce, most former British colonies still pegged their currencies to the British pound. As a result, when the British government decided to devalue the pound relative to the US dollar, the government of India decided to follow suit. Crucially, however, (and this, in hindsight, was a blunder of monumental proportions), Pakistan did not follow suit.

The government of Pakistan at the time felt that it did not want to devalue the rupee because it felt that Pakistan’s own macroeconomic indicators did not justify such a move. That decision, however, had a serious negative impact on the Pakistani economy.

For all the details: The rupee is falling. Let it crash.

To cut a long story short, when India devalued its currency and Pakistan did not, suddenly Pakistani goods became more expensive to produce relative to their Indian competitors, by a factor of 30%.By choosing to prioritise the absolute level of the exchange rate over the consequences for the rest of the economy, specifically the country’s nascent export industries, the government permanently altered Pakistan’s economic trajectory. Instead of integrated regional supply chains (which, by the way, survived the 1948 war just fine, suggesting that Pakistan and India can go to war and continue to trade at the same time), Pakistan is now

mostly cut off from its regional markets and has set back the development of its export industries by decades. Here is where things get interesting: the government of Pakistan did ultimately have to devalue the Pakistani rupee. In August 1955, the rupee declined by 44.2% relative to the US dollar in just one day, more than it would have, had the government decided to retain its parity with the Indian rupee and maintain its exchange rates with its main trading partners.

It wasn’t that the problem couldn’t be solved once it happened. No. The problem has been consistently trying to do the same things to manage the problem. For the first couple of decades Pakistan maintained its fixed exchange rate regime.

The situation changed when the country had to seek the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) help to manage the balance of payments position in 1981. As per IMF advice under Article IV consultation, Pakistan was asked to adjust its exchange rate significantly and gave Pakistan two options: either to make a one-time adjustment or a daily gradual adjustment.

Pakistan opted for the latter and switched to managed float in January 1982. Under this regime, the the exchange rate was set on a day-today basis, keeping in view (i) the exchange rate movements of Pakistan’s fourteen major trading partners, (ii) the exchange rate movement of 32 major export destinations of Pakistan, and (iii) the exchange rate movement of export competing countries.

Since 1982, almost every single government (with only one exception) has tried to artificially control the price of the rupee as a means of keeping inflation lower than it naturally would be if the exchange rates were left alone. Every time, the cycle is exactly the same: the government raises foreign debt as a means of securing more dollars, which it slowly sells over time so that it can create an artificially high supply of dollars in the economy and artificially high buying of the Pakistani rupee. This is obviously unsustainable, largely because the government is using borrowed money not to finance investment into future income opportunities for the economy but present consumption. Eventually, foreign lenders want their money back and are not willing to refinance, and hence the government’s ability to prop up the rupee ends, causing the currency to suddenly crash.

Pakistan followed managed float till mid-2000. After the nuclear blasts in May 1998, Pakistan switched to a dual exchange rate regime for a short time. In July 2000, Pakistan switched to a free float exchange rate regime and is officially following this regime till now. In this regime, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) intervenes in the foreign exchange market from time to time to smooth unnecessary volatility and quell specula-

tive attacks on the exchange rate.

Though the SBP officially follows a free float exchange rate and intervenes in the foreign exchange market only to curb disorderly market conditions, analysts have criticised that it is not pure free float but rather a ‘crawling peg’ – an exchange rate regime that allows currency depreciation or appreciation to happen gradually.

Perhaps nothing is as synonymous with controlling and managing the exchange rate in a bid to stay away from inflation than the name of Ishaq Dar. The four time finance minister who is now the foreign minister (and somehow still obsessed with propping up the rupee at a historic time in international relations) has created his own brand of economics based around a strong rupee. He has been responsible for plenty of disasters under his watch to do with the rupee. However, Darnomics actually precedes Dar.

And while all governments have tried to do the same things, perhaps the most egregious attempt to control both the exchange rate and inflation was in the Musharraf Administration, which sought to maintain an exchange rate of approximately Rs60 to the US dollar for nearly the entirety of its term in office. Inflation during that time averaged a relatively tame 6.6% per year, though the rate had started coming down under the latter part of the second Nawaz Administration and started creeping up in the last year of the Musharraf Administration. The full extent of the pain caused by the Musharraf government, however, was not felt until the Pakistan Peoples Party, led by then-President Asif Ali Zardari came into office in 2008. In the very last month that President Musharraf was in office – August 2008 – inflation hit 25.3% on an annualised basis. The rupee lost a third of its value in one year.

However, this was still fixable. Perhaps the only government that made almost no attempt to control the rupee’s exchange rate was the Zardari administration, which let the rupee be a truly market-based free float. But international oil prices meant there was soaring inflation from 2008-2013 as well. Despite making no attempts to control the exchange rate, inflation remained higher than the historical average, and clocked in at an average of 13.2% per year.

Which is why when Nawaz Sharif came to power in 2013, he came with the promise to regain control of the exchange rate. He came in with Ishaq Dar as finance minister, and that meant the formal inauguration of Darnomics. Even though the Zardari administration had broken the habit of controlling the exchange rate, there was no stopping Senator Dar.

The third Nawaz Administration famously tried to peg the rupee at Rs100 to the US dollar,

and mostly succeeded in doing so, though at the cost of rapidly increasing the foreign debt burden of the country. While inflation averaged just 4.9% during their tenure between June 2013 and July 2018, it is too early to tell just how much the damage will be in terms of currency depreciation and inflation, as a result of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Finance Minister Ishaq Dar’s decisions.

Dar took the helm of the finance ministry in 2013 at a time of favourable external conditions when crude oil was especially cheap in the international market between 2014-2017 going below $50 a barrel. Besides, the PML-N was fortunate to get Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus status in 2013 and managed to bring down the trade and current account deficits. These lower prices combined with a lower debt burden meant that Dar was able to loosen the government’s purse strings to catalyse growth and lower inflation in the short term.

Most of the growth was led by government spending on development projects, which raised problems of long-term sustainability. Pakistani exports dropped from $25 billion in 2013 to $22 billion in 2017, according to central bank data, stretching Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves and putting further stress on the country’s current account deficit.

By the time Nawaz Sharif was ousted by a judicial order in 2017, inflation was rising and the government needed to borrow more money to pay back its debt. From July to October of 2017 alone, the federal government obtained $2.3 billion in foreign loans, including $1.02 billion in commercial loans. The country’s official foreign currency reserves, which peaked at $19 billion, slid on the back of foreign borrowings to $13.5 billion as of November 17, barely enough to finance two-and-a-half months of imports.

A big reason for this was Dar’s insistence on pumping the market with dollars to keep the value of the rupee high. This of course caused the economy to start becoming a bubble. Because the rupee was overvalued, people went crazy on importing and the consumption-led growth continued leading to a classic case of overheating. The only recourse was going to be a sudden correction, a decrease in imports, a slowdown in economic activity and eventually an implosion.

Then Dar made a comeback to the finance ministry in 2022. He became finance minister in September 2022 and served until August 2023. Immediately after he took office, he declared the Pakistani rupee as undervalued and vowed to reduce interest rates, fight inflation, and strengthen the exchange rate. Dar was confident who during a television interview said “he knew how to deal with the IMF” since he had been doing it for decades, decided to artificially keep the price of the rupee high.

However, a few months down the lane, the reality set in as the promise of bringing down

The rupee is expected to remain stable in the near term and could continue if Pakistan’s economy remains resilient. However, external factors such as fluctuations in oil prices or geopolitical tensions could influence the currency’s trajectory. Central bank interventions and monetary policies will also be critical in maintaining exchange rate stability. Therefore, the Pakistani rupee’s current stability is a positive sign

the dollar to below the 200-mark fell by the wayside.

Soon, the country began facing a shortage of forex reserves that led to a curb of imports and skyrocketing inflation. In January 2023, Dar had to surrender to secure the last tranche of the of $1.1 billion of the $6.5 bailout package approved in 2019 and the rupee depreciated and reached an all-time low of Rs 262.6 per US dollar in the interbank market as the country abandoned controls on its exchange rate. The nosedive continued in February, as the rupee experienced a sharp decline, plunging to a rate of Rs 275.5 per dollar and causing significant disruption in the market. During this time foreign exchange reserves have dropped from $8 billion to a dangerously low of less than $3 billion.

The country was teetering towards a default. Pakistan avoided a default by securing a last-minute staff-level agreement from the IMF for a SBA on June 30, 2023. At the time, the country’s forex reserves plummeted to approximately $ 4.5 billion, covering not even a month’s worth of imports.

However, the currency market had other plans, as even after the disbursement of the much needed funds, speculators ran rampant and the rupee lost significant value, breaching the Rs 300 mark. This trend was curbed in September 2023, as a nationwide crackdown on speculators led to a sharp correction in the market.

This action was also necessitated by the fact that the IMF SBA required Pakistan to maintain the gap between the interbank and open market rates at a maximum of 1.25%. The idea behind this condition is simple: the IMF suspected that the SBP in the past has been coercing the banks into keeping the dollar rate artificially low in the interbank market. The IMF was apprehensive about this intervention, as it encouraged imports and discouraged exports, worsening the dollar reserve situation.

Therefore, post corrective measures,

the rupee gained value significantly and the exchange rate outlook remained positive in the short run. The exporters also became cognizant of the trend and ran to the forward market to hedge their risk.

The exchange rate has been largely stable in the last few months. However, recently there were some speculations of the Pakistani rupee appreciating and strengthening to Rs 220-230 against the greenback. Historically, that has been the case whenever PML-N comes into power: the Pakistani rupee has strengthened due to questionable economic practices like Dar-peg, as mentioned earlier.

However, these speculations are making rounds amidst a time when rupee has been declining against the dollar. The domestic currency has been depreciating marginally against the greenback for consecutive three days against the greenback between April 15 - April 17 2024 in the interbank market. (more on that later)

Pakistan is currently headed towards the next International Monetary Fund (IMF) Program that is crucial for the economic stability of the country. The country is stuck in a low growth and high inflation cycle. Finance Minister Aurangzeb is in Washington where he will be attending the IMF-World Bank spring meeting, and also start negotiations for Pakistan’s 24th long-term IMF bailout.

The next IMF Program is crucial for the economic stability of the country. Pakistan faces around $25 billion in external financing needs in the next fiscal year commencing from July, which is around three times the country’s current foreign exchange reserves.