09 CPEC isn’t quite the elixir we imagine it to be

11 Pakistan’s billion-dollar fund manager resigns quietly as SECP investigates suspicious transactions. Here’s what went down

15 Could the textile sector take their bankers down with them?

20 Greedy land developers want Pakistan’s agricultural land. Could the Supreme Court hold the answer?

27 Pakistan can become a cannabis powerhouse. The only problem is getting through the bureaucratic labyrinth

29 Secure goes for IPO, becoming first logistics company to do so

Profit

CONTENTS

09 15 27 11 27 20 Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi | Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan Shahab Omer | Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Ghulam Abbass | Ahmad Ahmadani | Shahnawaz Ali Aziz Buneri | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain Video Producer: Talha Farooqi - Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb ) Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news

CPEC isn’t quite the elixir we imagine it to be

CPEC can work for Pakistan only if it can translate all of those loans and FDI into growth, argues Rafiullah Kakar. If BRI participating countries like Pakistan don’t get their act together, Kakar cautions, they’ll just be stuck with a bill, with not much economic activity to show for it.

As if we’d hit oil.

It was - and still is - being marketed like the discovery of a massive reservoir of oil somewhere in the desert of Balochistan. Except, our proximity to China - geographical, and otherwisewasn’t exactly hidden under tonnes of dirt. But much like oil reserves, we are told, the CPEC would drag our economy out of the challenges that it faces.

The prospect of a bounty that would spill over from the burgeoning might of the Chinese economy have had the fine folks at the finance and planning divisions, not to mention the finer folk at Rawalpindi, excited since quite a while. And lo and behold, the Chinese seemed more eager than us to build

an economic corridor that would run through Pakistan.

In the very broadest of terms, it wouldn’t be unchartered territory for Pakistan. Having reaped the benefits - and consequences - of a unique geopolitical location since long, we have another, adjacent opportunity of doing the same. Except, this time it won’t be the facilitation of certain elements in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion in the 80s, or the facilitation of other elements against those earlier elements during the US invasion in the aughts. No, this time it would be trade we would be funneling through to and from The Factory of the World: China.

CPEC hysteria built up and became white-hot when the Chinese companies actu-

ally started doing civil works, with different political parties trying to take credit for at least some of the developments. Conversely, “bad-for-CPEC” also became an allegation to be lobbed at other parties.

In a bleak economic horizon, even clearly hyperbolic projected outcomes of CPEC were unquestioningly parroted by talking heads on TV.

“It does not make any financial and economic sense.”

That is Rafiullah Kakar, key policy wonk in Islamabad, urging a grand rethink about the whole thing with a frankness uncharacteristic of such a senior

9

----------------------------

Conversation with Profit

Rafiullah Kakar

planning mandarin.

Kakar says he has differences with the mainsteam media narrative about CPEC, which does not see it in it’s larger context.

That larger context: China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of which CPEC is but a part.

And, according to Kakar, the BRI is pretty much the way the Chinese regime seeks to solve four rather pressing problems, which could contribute to an infinitely serious fifth one.

The four problems?

“Number One,” says the former Rhodes Scholar, in his signature textbook manner. “China has the world’s highest foreign reserves.”

How is having more than three trillion dollars in reserves a problem?

“Because the Chinese want to reduce their dependency on the US dollar, specially in the case of any future trade war with the US.”

“Problem Two, is China’s surplus industrial capacity. China has a surplus industrial capacity in infrastructure-heavy sectors. The domestic demand for such infrastructure has almost been saturated,” he says.

That is correct. Inputs like steel, cement, the works…..well, the Chinese market isn’t gobbling up like it used to. China’s “Ghost cities” or Under-occupied Development, as the academics like to call them, are only the most visible symptom of the larger phenomenon of a slowing general demand.

Meanwhile China’s infrastructure-heavy industrial concerns are all dressed up with nowhere to go.

“Third, is China’s massive energy needs. They have a lot of external dependency for their energy security. Therefore, they want access to energy and natural resources.”

A stark problem, yes, for an economy like China’s; second largest in nominal GDP terms and largest in Purchasing Power Parity GDP terms.

“Fourth, there are certain sectors of the economy where China and Chinese products are globally competitive, so naturally, China wants access to new markets. Products like automobiles, telecommunications, these are the products for which China needs free trade.”

It needs more and more access to keep these factories humming, or else they’ll face a problem similar to that of the infrastructure industrial concerns discussed above.

The Belt and Road Initiative, Kakar argues, is a solution to these four problems.

But how?

“Let me explain. First of all, by concessional and semi-concessional lending of its surplus foreign reserves, China is diversifying the latter.”

“Secondly, so what if the demand

for infrastructure has saturated in China? There are dozens of low and middle-income countries in the world that do have a demand for infrastructure but don’t have easy access to infrastructure financing. China provides financing for these countries and creates the demand for its own infrastructure industrial capacity because most BRI contracts have a tacit condition that the contracts have to be given to Chinese companies.”

“That surplus industrial capacity,” he says, “is exported.”

Problems three and four - energy security and market access - are also addressed. If there are any natural reserve discoveries, the Chinese can be in on it, and of course, all the countries that have BRI projects would be very receptive to Chinese products.

Four solutions to four problems.

Neatly solved.

“That’s it. That’s what CPEC is there for. The Pakistani public have some grand ideas about Gwadar somehow becoming a regional trading hub, and that the Chinese are going to use this route to bring in their oil and other imports,” he says. “I don’t see that happening.”

“It’s a misplaced assumption. Number one: it doesn’t make any commercial and financial sense.”

The Heihe–Tengchong Line is an imaginary line that cuts across the map of China. It was imagined up in 1935 by Chinese population demographer Hu Huanyong, though that map, due to certain geopolitical changes, no longer holds true. In China’s current map, at the moment, 43% of China’s landmass is to the east of the Heihe–Tengchong Line and the remaining 57% lies on the west.

In 2015, that eastern 43% contained 94% of China’s population. The western portion contains a paltry 6%.

But Rafiullah doesn’t get into that; he cuts straight to the where-its-at of trade routes: industrial centres.

“China’s industrial centres are concentrated on its eastern coast. There is hardly any industrial activity towards the west.”

“If you’re going to take oil - or any other - imports through CPEC, to Kashghar, you’d have to transport that, via land, to the eastern coast,” he explains.

“That is a very expensive commercial proposition. The marine route is many times cheaper than this.”

He says that there are only two utilities of the CPEC corridor: “One, as an emergency route. God forbid, if there is some sort of third world war or China gets into some other military engagement, then for a certain number of

days, China can use it.”

“Other than that, maybe forty or fifty years from now, if western China also becomes an industrial centre, it would make commercial sense only then.”

But surely there must be some industrial centres close to the border with Pakistan?

“The closest industrial centre to Kashghar is Ürümqi. But even that is 1500 kilometres away from the border.”

Kakar twists the knife by putting it further in context: “That’s as much as the distance between Karachi and Islamabad. For just this one centre.” —-----------

Those are some sobering thoughts. If Kakar’s assessment is correct, the Chinese would have put up the money - and built through Chinese contractors - a CPEC, even if Pakistan were located on the dark side of the moon.

It’s just a place for them to park their money and give work to their infrastructure companies.

So none of that trade route traffic, but stuck with a bill to pay for? Is CPEC - and other BRI projects - a blessing or a curse?

“I think it is neither. CPEC is neither bound to become a game-changer, nor inherently going to become a curse for participating countries.”

So what is it that is going to make the difference?

“Whether the foreign investments under BRI translate into economic gains depends upon the capacity of the participating country.”

“Remember, FDI or foreign loans do not mechanically translate into economic growth. There are many steps in between that participating countries themselves have to take so that these loans and this FDI can be channeled into productivity enhancement,” he says.

What are those steps?

“Well, that depends upon a lot of context of the specific participating country, but by and large, the softer reforms, like ease-ofdoing-business reforms, governance reforms, etc. Countries that have both the capacity and the vision of complementing the FDI, so that the latter can translate into growth, for them, BRI is likely to become a blessing,” he says.

“Those who think the foreign investment is automatically going to translate into gains, the investment itself is going to become a challenge. Take a look at Pakistan’s power sector, for example. We got expensive electricity. Yes, we took care of the whole energy generation thinking very quickly. But the transmission and distribution aspect of energy and fixing the losses and inefficiencies was our responsibility. If we don’t fix that, it isn’t an inherent argument against CPEC investments.”

10

Pakistan’s billion-dollar fund manager resigns quietly as SECP investigates suspicious transactions.

Here’s what went down

The CEO of Al Meezan Investment Management Limited is not the first, nor will he be the last to be embroiled in such a controversy

11 COVER STORY

By Taimoor Hassan and Babar Nizami

It was the sort of notification you wouldn’t take much notice of unless you were from Pakistan’s asset management industry.

On the 1st of March, Al Meezan Investment Management (Al Meezan) announced that its CEO of nearly three decades, Mohammad Shoaib, was leaving. After 29 years at the top one might assume that this was like any other ‘change in management’ announcement and that Mr Shoaib was stepping down to enjoy retired life. But that wouldn’t quite add up. For someone who has been CEO of one company for so long, he is surprisingly not that old.

Shoaib graduated with an MBA from IBA in 1988. Armed with this and a diploma in banking from the Pakistan Banking Institute, he worked at the Pakistan Kuwait Investment Company for five years before becoming the founding CEO of Al Meezan. Under his leadership, the asset management company has grown to be the largest fund manager in Pakistan managing a pool of investment worth well over a billion dollars in different asset classes with a team of over 600 employees.

So why does a CEO with decades of experience, who is years away from retirement age, and running a very successful company suddenly decide to retire? There was certainly no news of a better job offer luring him away. And the initial word from Al Meezan was that he was retiring entirely for personal reasons.

The reason was vague enough, but didn’t quite pass the smell test. People within the industry and the company were also taken by surprise, which led to many speculations as to what the actual reasons behind this unexpected departure could be. Over the past few weeks, Profit has dug into what exactly went down at Al Meezan Investments. What has come to light are suspicions of front-running, letters coming in from the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), and pending investigations.

The SECP points a finger

It was still cold enough in February for the air conditioning to be off in most office buildings this year. Despite the chilly weather, one can imagine the atmosphere in the boardroom at Al Meezan’s headquarters got a little heated.

The board had just received a letter from the SECP. The subject of the letter was the CEO of their company. In the letter, the SECP noted that the CEO and his family, including spouse, son and daughter had engaged in some

personal trading of shares which contravened SECP’s regulations that aim to prevent conflicts of interest of senior employees of Asset Management Companies (AMC).

What conflict of interest?

It is quite simple really. The stock market has regulations that are supposed to ensure transparency and fairness for all players involved. Al Meezan is a massive company that controls a wide portfolio and has a lot of investors’ money to play with. An asset management company of this size investing in a particular side of the stock market could shift stock prices around. This is no problem of course. The way an asset management company works is that it pools money together from numerous investors and then invests that money in different financial assets (mainly shares of listed companies and government bonds) and distributes the profits to their clients, called unit holders, in exchange for fees.

The only problem is that these massive funds are run by people. Managers, accountants, and CEOs alike are simply people. And these people not only have access to prior information regarding investment decisions of their asset management companies but also have influence over these decisions. As such, the information they have is considered insider information. And insider information, if used for personal gains, could lead these people to making unfair gains at the expense of not just other market participants, but also the asset management company’s own unit holders.

Among stock market veterans such activity is known as front-running. It is a type of illegal insider trading but is distinctly different from the plain vanilla illegal insider trading where usually company officials trade in the shares of their own company based on undisclosed price-sensitive information. In the case of front-running, generally, a middleman uses knowledge of a large pending share trade, to make direct or indirect personal gain.

Consider an example. Assume that a brokerage house has been asked by its client to buy a very large number of shares of a company XYZ. The current price of XYZ is Rs10 per share. Now, the broker knows that entering a buy order of such a large quantity will increase the share price of XYZ. As the broker has taken the order from the client and the order is pending, he can buy 500,000 shares of XYZ for himself, before executing the trade for his client. Once the trade for the client is executed, the price ends up at Rs12. The broker can sell his own shares to either his own client or back into the market at Rs12 and make Rs1,000,000 in a risk free

manner. Front-running, which is an illegal act in almost all jurisdictions, is also considered a criminal offence in Pakistan.

So the question can be raised, against whom the crime has been committed? Well, the fact is that the client could have gotten his shares cheaper. Let’s say the client wanted to buy 1000,000 shares at any cost from the market. There were 500,000 shares being sold for Rs10 and 500,000 shares for Rs11. If the broker had been honest and had not carried out front-running, the client would have made the purchase of 1000,000 shares for Rs10,500,000. However, as the broker bought the shares at Rs 10, the client will end up buying shares at a higher cost than what should have been paid in a fair manner. The client trusts the broker and expects to get the best price in the market. The broker breaches that trust and disadvantages the very person he is supposed to look out for.

This can also happen on the sell side where the broker sells his own shares before his client’s knowing that a large quantity will be sold which will depress the prices of the stock.

How it works with asset management companies

The process is a little different, but front-running also applies to large financial institutions or asset management companies like Al Meezan. Asset management companies run mutual funds and have fund managers and fund management investment committees who meet regularly to determine whether they should buy or sell a certain shares and other financial assets. These meetings are documented and the recommendations made are scrutinised.

Once the committee makes a decision, the goal is to buy or sell the security which will benefit the fund and in the end the clients who have invested in the fund. As mutual funds combine the investment of hundreds of investors, they can buy or sell large quantities of stock over a period which could have an impact on the price of the stock.

Now consider someone who is part of the management committee or can get hold of the minutes of any such meeting. Being purview to this information that a fund is going to buy hundreds of thousands of shares of a company, an individual can buy a certain stock for themselves in their account. Once the fund executes its order and the buying has been completed, it is obvious that the share price will increase. From here on out the process of how a fund manager can take advantage of this is pretty self-explanatory.

And even though not many people

12

realise, front-running is common enough in Pakistan. In some high-profile, though not largely publicised, cases of front-running, the SECP has filed criminal cases against senior bankers, fined leading brokerage houses, and even revoked the licence of an AMC in one case. Here are some:

i) Front-running by UBL’s head of capital markets

In 2017, SECP filed a criminal case against Khalid Iqbal, head of capital markets at UBL after it found him guilty of front-running charges. It all started when SECP noticed two back to back unusual purchases by UBL. The bank had bought 6.5 million shares of Gharibwal Cement Limited, a share in which not a lot of trading is done. A few days later the bank purchased another 6 million shares.

During investigations, it turned out that Iqbal was authorising these purchases on behalf of UBL where the counterparties (sellers of shares) were his three accomplices. Essentially the scheme was that Iqbal’s accomplices would purchase the shares from the market at a cheap price and then Iqbal would get his bank to purchase these shares at a higher price.

The court found all four guilty of front-running charges stating that the accused made illegal profits, causing financial loss to UBL.

ii) BMA Capital fined Rs50 million for front-running

In 2013, BMA Capital, renowned in the investment banking sector, faced a maximum fine of Rs50 million from the SECP for front-running a foreign client. Their approach involved buying shares of Bata Pakistan from the National Bank of Pakistan and subsequently selling them to their client Bafin (Nederland) BV, a holding company for most of Bata’s global subsidiaries, at a higher price. BMA Capital was aware of Bafin BV’s intention to purchase shares of Bata Pakistan.

Instead of acting as an intermediary between its brokerage client Bafin and National Bank for the purchase of these shares, BMA Capital first directly acquired 578,000 shares of Bata Pakistan at Rs920 per share from National Bank and later, they sold 587,500 of these shares to Bafin at Rs1,000 per share.

Interestingly BMA kept changing its stance during the investigation. In the first letter sent by the firm’s CEO to the regulator BMA admitted that they were negotiating with NBP on behalf of their client Bafin. In subsequent letters, drafted by BMA’s lawyers, the company claimed that its trade was a purely proprietary one, that is, BMA was buying these shares for itself.

The SECP found that BMA bypassed its fiduciary responsibility towards its client, illegally profiting Rs46 million from the trade.

The BMA case is also an example of how even leading brokerage houses are willing to bend official rules and regulations for gains that are not very big.

iii) Dawood Capital Management’s licence revoked, CEO fined for front-running

Likewise in 2013, the SECP revoked Dawood Capital Management’s licence and fined its CEO, Tara Uzra Dawood, Rs20 million for front-running.

After a thorough nine-month investigation, Tara Dawood was found guilty of defrauding investors in Dawood Capital-managed mutual funds. This was due to her exploitation of her position as CEO and her advance knowledge of an impending writedown in the mutual funds’ value.

Dawood Capital Management, a subsidiary of First Dawood Group, had invested in corporate bonds issued by several defaulting companies, including Pace Pakistan, Maple Leaf Cement Factory, Pak Elektron, and Telecard.

During a February 21, 2012 audit committee meeting, auditors recommended a write-down on the bond investments, pending a precise determination at the April 28, 2012 board meeting. Before this meeting, between April 6 and April 26, Tara Dawood, her family, and associated companies sold nearly Rs117 million worth of units in the Dawood Income Fund and Dawood Islamic Fund, sparing themselves a combined Rs18.2 million loss.

Dawood Capital Management attempted to evade scrutiny by modifying board meeting minutes to conceal the write-down discussion. However, SECP’s request for initial drafts revealed the truth, corroborated by independent directors’ testimony, leading to their resignation.

In hearings held in early 2013, Dawood Capital Management defended the redemptions as coincidental and attributed minute falsifications to a clerical error by the CFO, Syed Kabiruddin. However, SECP deemed this explanation insufficient, resulting in the unprecedented revocation of Dawood Capital Management’s licence, a fine for Tara Dawood, and orders to dismantle the mutual funds and refund investors.

As we explain below, the case of Al Meezan is closest to Dawood Capital Management’s case back in 2013 because of the involvement of the CEO of the AMC and gains made by an individual rather than the AMC.

What happened at Al Meezan?

Let’s get down to the technicalities. According to the NBFC and notified entities regulation section 38(B), an asset management company is

required to put in place appropriate policies and procedures, approved by its board of directors, which govern trading or investment in securities by AMC employees, their spouses and dependent children.

What the regulations prevent is deriving gains using information that is generally not available and proper disclosures of trades by employees. Based on the rules outlined by the regulator, asset management companies have their code of conduct for asset managers, which could prescribe stricter rules than those prescribed by the regulator.

Both the regulations by the SECP and Al Meezan’s own code of conduct require employees of the company to not engage in personal trading in securities in which the AMC also has a pending order to trade in. Essentially an employee who is privy to the AMC’s investment decisions has to wait for 24 hours after the pending trade by the AMC is executed or cancelled before they can trade in their personal accounts. This is what is called a blackout period. This is to prevent any unfair gains made by the employee through front-running. It would seem that the SECP feels that Al Meezan’s CEO did not adhere to this rule.

As per an official close to the company, one of the things that SECP pointed out in its letter was that in some of the transactions, the CEO and his family had traded in the shares of the same companies as Al Meezan traded in. The SECP noted that in these transactions the CEO and his family had traded at a better average buy/sell prices as compared to the average buy/sell prices of the mutual funds of Al Meezan Investment, resulting in an alleged personal gain of Rs 22 lac approximately over a two year review period.

This would mean that the CEO and his family members were trading at the same time Al Meezan was making investments. Coupled with the fact that Shoaib was privy to investment decisions by the company because Shoaib was a member of the investment committee at Al Meezan as per the company’s annual accounts for 2023, front-running can not be ruled out. It is even possible that the counterparty in the trades carried out by the CEO and his family could have been Al Meezan itself, the family making gains for themselves at the expense of Al Meezan’s investors.

The same regulations and code stipulate that even outside of the blackout period, trades by the CEO and his family are to be reported immediately to the board of directors, internal compliance head of the company as well as the SECP. There is also a requirement to report personal holding position at the end of each quarter.

The official source close to the company told Profit that in his capacity and for his

COVER STORY

spouse, Shoaib had been reporting trading transactions that were carried out to the board quarterly and only failed to do so for his adult children, which the source thinks could be a genuine oversight or a different interpretation of regulations.

Upon initiation of a review by Al Meezan’s board, the CEO offered to resign to carry out an impartial investigation of the matter. “The board approved his resignation,” said the official source.

However, two sources, one a high-ranking official at the SECP speaking to Profit on condition of anonymity confirmed that the CEO did not resign voluntarily and was asked to resign by the board based on charges by SECP.

When contacted, a senior official representing Al Meezan’s board informed Profit that SECP’s observations do not relate to investment/fund management and financial reporting of Al Meezan or the Funds managed by it.

“SECP has shared certain observations relating to personal shares trading by family members of the CEO with the Board of Directors of Al Meezan and the board is reviewing the same. The CEO has decided to resign from his position,” the statement from Al Meezan Investments read.

It is important to note that as per Al Meezan’s code of conduct for asset managers, a violation of company’s trading policy for employees requires them to forfeit any gains made through such transactions.

Where will the investigation lead?

What could have possibly transpired in Mohammad Shoaib’s case? Shoaib would certainly be privy to a lot of information about trade transactions that he could have used to his benefit but as one investment professional puts it, “if he had to carry out front-running, he could have used better proxies than his own wife and children. Knowing also that since he’s been around at the company for about three decades, he would obviously know the rules governing such transactions and the consequences of violating these rules”.

On the other hand, a source in the industry argued that the CEO being lax about oversight for two years felt out of touch, and reflects badly on the board and is an issue on its own.

For now, the fate of this case rests in the hands of the investigating officers of the SECP, and only time will tell what conclusions they come to. We can, however, take an educated guess based on similar investigations that the securities and exchange commission has carried out in the past. When it comes to front-running, if found guilty, Al Meezan’s former CEO can definitely be penalised. But that isn’t all. Because of the CEO, the asset management company itself can be caught in the crosshairs too.

In its official response, the regulator did not disclose details about the investigation and said, “To perform its regulatory functions, SECP regularly carries out inspections, inquiries, and investigations and takes other regulatory actions, per its administered legislation.”

“However, on account of SECP’s operational SOPs and relevant laws, unless a matter is concluded, we cannot either confirm or deny initiation of any purported action or proceedings against any regulated entity or person.”

“Any conclusion, decision, or enforcement action, if any, is made public through placement on SECP’s website for public information, subject to the policy of the Commission and permissibility under the law.”

When reached out by Profit, Muhammad Shoaib decided not to respond. n

14 COVER STORY

Snapshot of 38B NBFC Regulations

Could the textile sector take their bankers down with them?

High financing costs are impeding the ability of multiple sectors to maintain debt servicing

By Ahtasam Ahmad and Mariam Umar

The strategy from Pakistan’s banking sector has been pretty clear over the last couple of years. As the economy has gone through the process of overheating during dangerous political turmoil and the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has maintained consistently high interest rates due to inflation, commercial banks have taken the easy approach to surviving and thriving.

A bank’s business is to accept deposits from customers and lend it to other customers. It’s a pretty basic model at the heart of it. But with inflation hitting record highs and interest rates still capped at 22%, businesses haven’t exactly been lining up for credit. So what do

the banks do? They lend to the one entity that does constantly need money no matter what: the government.

By lending with minimal risk and earning a favourable spread between borrowing and investment rates, banks have achieved impressive profits in hard economic conditions. Commer¬cial banks posted an impressive 83 percent earnings growth during 2023, with almost all banks recording historic profits.

The allure of these rich rewards have been the subject of discussion within the country’s financial circles. Economists have been concerned that while unprecedented interest rates yielded higher profits for banks, they were overburdening the economy because of costly borrowing. Private businesses have made similar complaints. Interestingly enough, however, there are those within the banking

sector as well who are concerned by the current predicament.

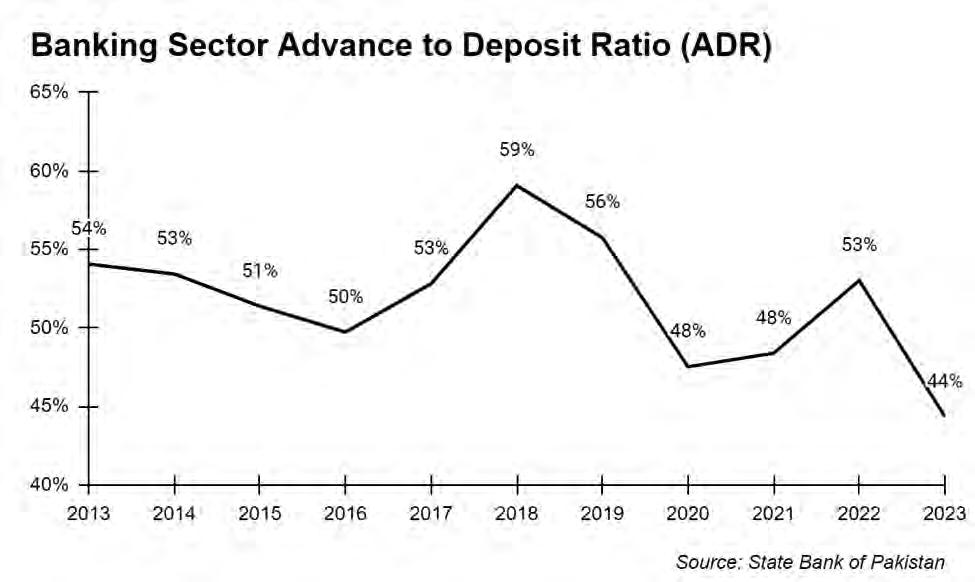

Lending to the government is profitable at a time like this. But it severely impacts private sector credit. The inherent risks associated with engaging in lending operations, particularly in the current high-risk environment, have also constrained the growth of the banking sector’s credit portfolio.This is reflected in a low Advances-to-Deposit Ratio (ADR) of only 44% as of the end of 2023. This means Pakistan’s banks lent Rs 0.44 for every rupee they received from their depositors in 2023, reflecting a poor state of affairs in private credit.

But this is also the conundrum part of the equation. You see, banks do want to lend to the private sector. Why would they not? They can make money from the government

15 BANKING

A monetary tightening cycle generally invites concerns over asset quality of banks and potentially large provisioning expenses. This cycle, which has witnessed a 1,500 bp expansion in Policy Rate (22%) in past 3 years, is no different when it comes to similar concerns

Amreen Soorani, head of research at JS Global Capital

too but private credit is a lifeline. The problem is that some borrowers in particular are fast becoming very high risk. Take, for example, the textile sector. Their business has plummeted because of the ongoing economic crisis. In such a scenario, will they make good on their loans or could lending more give banks a lot of non-performing loans on their books? After all, this also wouldn’t be the first time the textile industry gives commercial banks a big hit. Profit investigates.

Not the first time

The year is 2005. Pakistan’s textile industry is thriving. It is one of the largest textile operations in the world. Thanks to the textile industry, cotton farmers in the country are also thriving and the production for that year was 15 million bales. Similarly, banks are having a field day lending to what has become a reliable sector of the economy.

And then the energy crisis hit. From 2005 onwards Pakistan had a dire lack of electricity both for domestic and commercial consumers. The machines could no longer run and over the next 10 years over 10% of mills in the country would shut down. In fact, here is a sobering statistic. Two decades ago Pakistani textiles were in demand globally. However over those 20 years, countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have all surpassed Pakistan. In 2003, when Pakistan’s textile exports were $8.3 billion, Vietnam’s textile exports were $3.87 billion, Bangladesh’s were at $5.5 billion. Now Vietnam is at $36.68 billion and Bangladesh is at $40.96 billion, while Pakistan is struggling to hit $20 billion in 2022.

The fall of the textile sector has sent ripples throughout the economy. Our exports have teetered, cotton has been decimated as a crop, and back in the aftermath of the energy crisis Pakistan’s banking sector was also facing a reckoning.

Because the industry was so mas-

sive, when mills started defaulting on loans the banking sector was suddenly facing a crisis. Around the peak of the crisis in 2008-09, the government had to step in and try to mend relations and negotiate a solution. A one year moratorium was given by the State Bank of Pakistan, while restructuring of outstanding loans and interest rates were to be settled with commercial banks for which multiple committees were being formed.

Perhaps nothing covers the dire atmosphere better than this Dawn article from 2009:

“Yet another committee is being formed by the government to bring depressed and demoralised textile tycoons and concerned and worried bankers on one forum to discuss repayment schedule of outstanding loans, interest rate and other related issues.”

Dejavu?

For a while, the banking sector learned from its mistakes. But around 2020, things were picking up for the textile industry once again. There was a significant increase in textiles and apparel exports from 2020 to 2022, growing by 54%. The

industry experienced a decline in exports to $16.5 billion in 2023, down from $19.3 billion the previous year, attributed to the economic crisis and the removal of export facilitation measures.

But this was a small blip. The textile industry has encountered various challenges in recent years. The sector is currently struggling to return to its pre-crisis export levels, facing obstacles such as uncompetitive energy prices, liquidity shortages, and delays in tax refunds. Limited investment in manufacturing capacity has also hindered export growth, with the sector’s annual export capacity estimated at around $25 billion.

The textile sector’s health, in particular, is a significant concern for many banks due to their considerable exposure to businesses in the industry.

“Any downturn in the textile industry could lead to a surge in Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) for banks, as the textile sector constitutes a significant portion of banks’ credit loan books, its instability poses a substantial threat to the overall financial health of the banking sector directly affecting their profitability,” remarked Saad Hanif, deputy head of research

16

Any downturn in the textile industry could lead to a surge in Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) for banks, as the textile sector constitutes a significant portion of banks’ credit loan books, its instability poses a substantial threat to the overall financial health of the banking sector directly affecting their profitability

Saad Hanif, deputy head of research at Ismail Iqbal Securities

at Ismail Iqbal Securities.

“With many textile companies heavily reliant on bank financing for working capital and expansion, adverse market conditions, such as fluctuating cotton prices, energy shortages, or global demand shifts, can strain their ability to service debts, thus increasing default risks. Moreover, the interconnectedness of the textile sector with various ancillary industries amplifies the ripple effects of any downturn, potentially worsening asset quality across the banking sector.”

Banks on the receiving end

Let us for a second step away from textiles and look at what the banking sector has been doing recently. Over the past decade, Pakistani banks have experienced a significant transformation in the delivery of services and the range of products offered to customers. The introduction of digital banking services stands out as a notable example.

Given the advancements in technology, one might expect a corresponding evolution in the lending profile, with a larger portion of the

portfolio directed towards the private sector. However, this expectation has not materialised. In fact, the situation has taken a turn for the worse.

Since 2013, the ADR has consistently remained above 50% with the exception of three years and reached its highest point in 2018 at around 59%. However, it currently stands at an all time low of 44%. Notably, the years in which the ratio fell below 50% were 2020, 2021, and, obviously, 2023. The downward trend in the ADR would likely have persisted in 2022 if the government had not opted to penalise banks with ratios below 50% by imposing additional taxation.

The current macroeconomic headwinds make it extremely difficult to maintain the quality of the loan book especially after the prolonged monetary tightening cycle.

“A monetary tightening cycle generally invites concerns over asset quality of banks and potentially large provisioning expenses. This cycle, which has witnessed a 1,500 bp expansion in Policy Rate (22%) in the past 3 years, is no different when it comes to similar concerns,” writes Amreen Soorani, head of research at JS Global Capital, in an analyst note.

“Moreover, in midst of these concerns,

the sector faced regulations discouraging a lower ADR by penalising the same via higher taxes, which were later exempted for the year 2023, but currently remain in place for 2024 and beyond. This exemption for 2023 led to banks moving away from loan disbursements this year, reducing ADR from 53% to 44%, as lending demand also reduced amid higher borrowing cost, coupled with the banking sector cherry picking blue-chip borrowers to shield its asset quality,” she adds.

The concerns raised by Soorani in her analysis have also been echoed by Pakistani businesses. Recent reports indicate that corporate clients of commercial banks are feeling the effects of the record-high policy rate.

Key sectors affected include textiles (specially spinning and weaving), steel rebar manufacturers, and poultry feed mills. These sectors are not only grappling with high financing costs but also contending with the impact of demand-suppression measures which have significantly impacted their revenues.

While the repercussions of declining asset quality may pose a threat to banking profitability, institutions have implemented certain safeguards to prevent a sudden increase in loan losses on their books. The primary measure involves recording timely provisions for indicative asset quality deterioration. How well the banks are shielded in case of an adverse event can be gauged through the coverage ratio, a measure of the adequacy of a bank’s provision reserves relative to its NPLs, calculated by dividing reserves by NPLs. A higher ratio means better coverage for potential losses.

While the cumulative coverage ratio exceeds 100% for major banks in the sector, the results are skewed due to some outliers as pointed out by Soorani in her analysis. “Among our banking universe, while Coverage Ratios for only half of the banks surpass the 100% mark, the sample average also went beyond 100% this year, skewed by Meezan Bank’s 179% Coverage ratio.

BANKING

Banks further expanded coverage though General provisioning this year, with a growth of 40% YoY. Overall coverage under General provisions clocked in at 15%, with 86% covered through Specific provisions.”

However, that’s not all there is to it. The decline in the sector’s asset quality coincides with the implementation of IFRS-9 by Pakistani banks, potentially resulting in the recognition of accelerated provision losses by these institutions.

The IFRS-9 Conundrum

Before delving deeper, it is important to understand a few financial jargons. First is the application of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These, as the name suggests, are global standards that set the rules for drafting financial statements. The standards are adopted by many countries including Pakistan, to ensure the uniformity of financial reporting to allow for comparability of financial statements and investor reliance.

Now the specific standard under question is the IFRS-9. The standard essentially governs the treatment of financial instruments including assets and liabilities.

For the purpose of this story, we will be explaining a certain section of that standard which is the Expected Credit Loss (ECL) Model and its impact on the loan portfolio. The standard, under the ECL Model, requires that the outstanding loan portfolio should be

assessed periodically, and an expectation must be developed of its recoverability. If a portion of it is deemed unrecoverable, an appropriate provision should be recorded or in simple terms a loss should be booked.The quantum of the loss depends on the stage of the assessed credit risk. So, initially the loans are placed under stage 1 which doesn’t imply a significant risk of default. However, if there is a significant increase in credit risk like amounts being rescheduled or categorised as NPL, the loans are moved to stage two and three, and additional amounts are provided for.

As per Hanif, “under IFRS 9, banks are

required to assess the credit risk of sectors they have exposure to, considering various factors i.e. macroeconomic conditions, industry trends, and specific sectoral risks. In the case of Pakistan, where macroeconomic conditions and economic headwinds have posed challenges to multiple sectors, it is likely that several sectors would fall into higher-risk buckets under IFRS 9.”

This implies that banks would need to evaluate and assign ratings to sectors and obligors individually, which would then form the basis of their provisioning assessment.

The outlook

As per BMI Research, the research arm of Fitch Solutions, which is also the parent company of Fitch Credit Ratings, in 2024 stronger economic growth and improved business sentiment are expected to drive private sector loan growth in Pakistan, particularly in the manufacturing sector. Despite a decline in manufacturing loans in 2023 due to challenges in textiles and chemicals, the rebound in agricultural and industrial output is anticipated to positively impact manufacturing subsectors such as food products and textiles in the upcoming quarters, leading to a rise in manufacturing lending in 2024.

However, securing additional funding from the IMF by increasing tax revenue may pose risks to business reinvestment rates, household purchasing power, and subsequent credit demand, potentially limiting client loan growth compared to historical trends.

Moreover, a lot depends on the revival of demand for key products in sectors such as textiles and the initiation of a monetary easing cycle to alleviate financial cost pressures for private businesses, thereby enhancing their debt servicing capacity. n

18 BANKING

20

AGRICULTURE

By Abdullah Niazi

Pakistan has far too many housing societies. Take a drive around Lahore and its outskirts and you’ll see exactly what we mean. It seems at times that at every corner, every turn, every bus stop there is a new one. An endless expanse of residential real estate projects with names like XYZ Cooperative Society, ABC Gardens, 123 Villas, Al-Something-or-the-Other Town, and Mountain/River/Ocean City.

And this isn’t just the case in Lahore or other large urban centres. All around the country ridiculous amounts of money have been pumped into real estate projects that have very little economic or social utility. The reason it has been so easy to do so is because for decades the business of land in Pakistan has operated like the Wild West. Developers have followed set strategies that have allowed them to acquire, market, and sell land as real estate projects with seemingly very little regulation. It has been absolutely free for all.

Until now. The party, our dear real estate developer friends, might finally be over. During the proceedings of a recent case regarding the land for a housing society in Rawalpindi, a three member bench of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (SC) expressed shock over “flagrant violations” of the law committed in the acquisition of the land for the housing project nearly 20 years ago.

The case in particular being heard by the three-judge bench headed by Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa emerged from complaints moved by a number of people who were deprived of plots despite making payments in the society. Surprisingly enough what irked the court more than the complainants was the acquisition process through which the project got its land. Apparently, the land being developed had been “converted” from agricultural to real estate. It has been a common enough practice within real estate development over the decades, but one that has come under scrutiny.

A decision is still some ways away in this particular court case. But one important development has been that the SC has framed a list of eight questions that will determine what the conditions are to use agricultural land for non-agri related commercial activities. These questions could become central to what regulates and rules how land acquisition and transfer processes work. Essentially, it might mark the first time real estate developers really have to contend with serious restrictions in starting such projects. But to really understand and get to the bottom of what this means, we need to start

at the beginning. By looking at the process of how these societies come into existence in the first place.

Residential real estate galore

Without getting into the intricacies of why Pakistanis invest so heavily in real estate and whether or not that is a good idea, we can safely say that real estate investments have worked out for money. A few years ago Profit compiled an index to show average returns across asset classes in Pakistan from January 1, 1999 through the end of June 2020. What we found was that real estate was the third-best performing asset class available to ordinary Pakistanis, behind the stock market and gold.

Take, for example, the Defence Housing Authority (DHA) — an organisation that is synonymous with residential real estate in Pakistan. The first and the oldest DHA in Karachi was initially a private housing society formed in the 1950s. In the decades since it has gone from going under the control of different core commanders to being institutionalised as an Act of Parliament. Over time owning a plot in DHA has become almost an aspirational matter. People save their entire lives to buy plots here and secure their investments. And over time, DHA has expanded.

Lahore, for example, is now on to its ninth phase of DHA where development has taken place and people are using it as a residential area. They have also done extended projects such as DHA Rahbar, which itself is on its fourth phase. In fact, DHA represents a whopping 25% of Lahore. What was initially 34000 kanals has now been stretched to cover a whopping 3 Lacs 12000 kanals.

This success has been replicated. As a result far too many have tried to become real estate developers. The only problem with this is that land is limited and the developers seem to be unlimited. Now, normally the process of land acquisition is quite clearly set out. Before a developer can apply for an NOC for a project, they need to submit their documents to the relevant development authority (the RDA in case of Rawalpindi for example). For this, the first step is that they need to have land.

In case a person already possesses land and wants to construct a project on that the process is pretty simple. But if an investor is coming in from the outside, they need to find a way to acquire this land. The correct procedure is to approach a land provider who negotiates with local landowners in the area. These can be both private land owners as well as different government depart -

ments that might have land in this area. The developer can purchase this land, which is supposedly unproductive, either in exchange for cash or as a barter agreement. What this means is that a developer could say to a land owner that he will take 2 acres of his land off his hands, develop it and return it to him in the form of a 2 Kanal plot that will be worth a lot more than the barren land he currently has.

Once this process is complete, the developer creates a masterplan. This is privately owned town planning essentially. They need to create maps, blueprints, identify roads, sanitation, electricity infrastructure as well as figure out population requirements like how many hospitals, schools, shops and other such places are needed. These plans are then submitted to the relevant authority which gives the developer and NOC and they begin marketing and selling their project.

Fraud aplenty and court interventions

But this is rarely ever how it goes. Acquiring this much land is an expensive and risky business. Usually when a developer launches a new project they don’t want to go all in on it by buying the required amount of land. What they do then is go on a marketing campaign in which they announce a new housing scheme, often getting celebrity endorsements and pasting huge advertisements all over the cityscape. They sell people files, certificates, and all manner of marketing gimmicks that make them think they are buying a plot in the future when in fact they are at best placing a bet on the success of said project.

What they are doing instead is getting together enough capital from these ‘advance bookings’ to actually be able to buy the land required for the project. The people investing are told their plots are still in the development stage and they will only be told where their plot is once the technical aspects of mapping and zoning are figured out. The truth is that the land has not yet been purchased by the real estate developer.

It is a story we have seen plenty of times. Investors in the hopes of making money or having savings for their future invest in these housing societies. They trust them because the societies run massive marketing campaigns with callous disregard for the truth. They also trust them because the project is backed by large groups and famous business families who hire celebrities as ambassadors for their projects. We have seen it happen before in Gujranwala and in Chakri and in so many other places.In the end, after the investor has surrendered their money, they are flippantly informed that the project

22

“Right now we are instead focusing on real estate. What no one seems to realise is that while building a house generates immediate economic activity, once it is finished everything in that house is imported. Everything from the tiles and the fixtures in the bathroom to the car that will be parked in the garage and the chargers that will be plugged into the socket is imported. On top of that the land can also not be used again. If we had spent the same amount of money and energy on agriculture that would have a much bigger impact”

Ali Tareen, farmer

is pending approval and given some halfbaked excuse, leaving them to the dogs.

This is where the court cases usually come in. On the one hand you have people that bought files complaining that they aren’t getting their promised plots. On the other, you have those few that actually provided the small bits of land that these developers acquire. They have been promised developed plots too. The developer, meanwhile, is out of funds and has done some sort of half-hearted development. The plots are stuck in a state of limbo and so are all the affectees. The rot goes deep enough that on some occasions even government departments have had a hard time recovering their land from real estate developers because someone has built a few houses over it.

Glaring examples

It really has become a bit of a predictable mess. But the reason for going into such detail was because real estate development is also a threat to Pakistan’s agricultural land. This is vastly problematic because Pakistan already faces a severe crisis in agriculture where yields are falling and so is the patience and belief in farming as a profitable business and lifestyle.

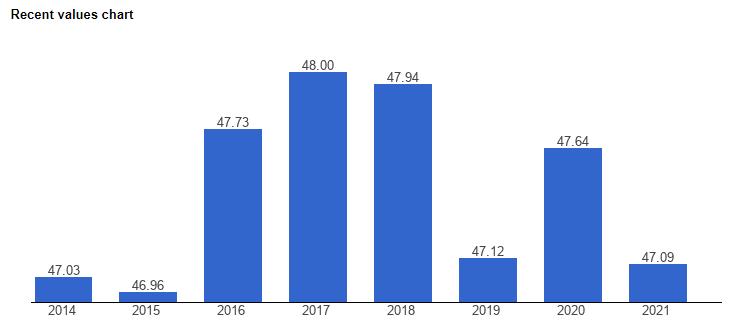

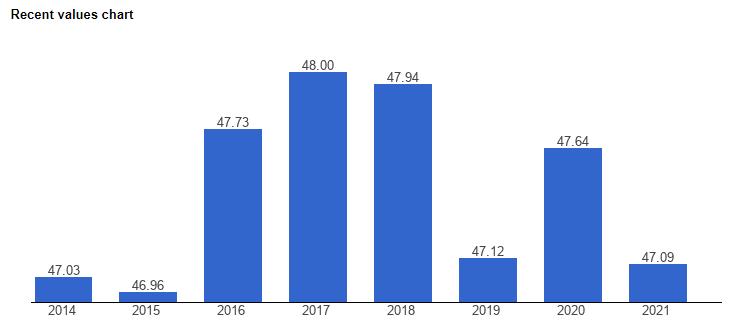

Data compiled by Profit using statistics from different departments such as the central bank and the PBS shows that Pakistan in 2021 (which is when the latest figures were available for) had just over 47.09% of its land under cultivation. Data from 1961 to 2021 shows that on average this number has been around 47.6%. What is glaring, however, is the eight year period between 1982 and 1990. In 1982 this area had actually risen to around 49.95%, but had fallen to 45% by 1990. This is of course due to a number of factors.

Area under cultivation is a precious commodity. After all, the amount of land is not going to increase in any country. What we can increase are our yields, farming techniques, farm economics, and the quality of the agricultural inputs we use.

Pakistan has a dire need to invest in its agriculture. Last year, the country became a net importer of food. For an agrarian economy, that is an abysmal state of affairs. Yet despite this we continue to put money into real estate development, going so far as to convert existing agricultural land into commercial real estate and play with the very existence of entire rivers.

“Right now we are instead focusing on real estate. What no one seems to realise

is that while building a house generates immediate economic activity, once it is finished everything in that house is imported. Everything from the tiles and the fixtures in the bathroom to the car that will be parked in the garage and the chargers that will be plugged into the socket is imported. On top of that the land can also not be used again. If we had spent the same amount of money and energy on agriculture that would have a much bigger impact,” explains progressive

AGRICULTURE

farmer Ali Tareen.

The one thing we cannot afford is for the amount of land we use to grow crops to also fall. That is exactly what the Supreme Court expressed concerns regarding in the recent case as well. The fear is not unfounded. There are many examples of agricultural land being used for residential real estate purposes instead.

Back in 2014, for example, the then provincial revenue minister and current chief minister of the province, Ali Ameen Gandapur, told the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa assembly that he total agriculture land in the provincial capital was 109,883 acres in 200102, which shrank to 106,576 acres in 2013-14. He said the data compiled by the office of the deputy commissioner showed a total of 3,037 acres reduction in agricultural land due to rapid urbanisation. Gandapur said like other districts, agricultural land in Nowshera, too, was under pressure due to construction of housing schemes and commercial activities. He said the farmland in Nowshera measured 289,094 acres and that the houses had been built on the 6865.5 acres of it since 2000. The minister admitted that it was a serious issue but the government was unable to stop construction on private agriculture land.

The reason he gave for the government’s inability to curb this? There was no law to restrict construction on agricultural land. Gandapur said the government could only prevent construction or other activities on the state owned agricultural land in the province. He said the planning and development department was chalking out a policy to stop utilisation of agricultural land for commercial or residential purposes.

In more recent times, farmers have also been vocal in their protests against such development. Back in October 2023, climate activists and agriculturalists banded together to voice their demand for an end to the development of housing societies and commercial structures on agricultural lands.

Under the Pakistan Kissan Rabita Committee (PKRC) banner, protestors gathered, denouncing profit-driven agricultural practices and urging governmental intervention to halt the conversion of farmland into commercial properties. They emphasised the critical need to safeguard food access amidst escalating climate change impacts. “We call upon the government to intervene and halt real estate developers from converting valuable agricultural lands into commercial ventures,” asserted PKRC General Secretary Farooq Tariq. He underscored the dire consequences of such conversions, highlighting their role in exacerbating climate instability, threatening food production, and undermining national food security.

“We call upon the government to intervene and halt real estate developers from converting valuable agricultural lands into commercial ventures,”

Farooq Tariq, PKRC General Secretary

The recent court case

The Supreme Court was right to be irked at the land acquisition process of different housing societies in the country. The particular case that the three-judge bench is hearing has to do with the Revenue Employees Cooperative Housing Ltd (RECHS) in Rawalpindi.

RECHS acquired more than 2,830 kanals of land in 2005, subsequently transferring it to Bahria Town Ltd (BTL). BTL then conveyed the land to the Defence Housing Authority (DHA) in 2007 for the development of Askari 14 in Rawalpindi. This transfer occurred despite opposition from then-Punjab cooperatives minister Malik Mohammad Anwar, as indicated in a written statement. However, former chief minister Chaudhry Parvez Elahi overruled Anwar’s objection.

Expressing concern, the court questioned the conversion of agricultural land for residential or commercial use. CJP Isa requested concise statements from BTL and DHA elucidating this conversion, along with a site plan.

According to court proceedings, an agreement between Bahria Town and retired Colonel Abdullah Siddiq, the administrator of RECHS, was signed on Feb 17, 2005, resulting in the transfer of society land to Bahria Town. BTL subsequently transferred the land to DHA through another agreement in 2007. The CJP expressed dissatisfaction with the nature of this agreement. Punjab Advocate General Khalid Ishaq admitted that the RECHS administrator lacked authorization to enter into such an agreement after his tenure expired. He also noted that the former Punjab chief minister did not possess the authority to override the objections of his minister regarding the land transfer.

Moreover, the agreement between Bahria Town and RECHS was drafted on Bahria Town letterhead. Additionally, it was executed before the expiry of the five-year membership period for society members. Advocate Hassan Raza Pasha, representing Bahria Town, pledged to address the grievances of affected petitioners.

The eight all important questions

All of this has created a bunch of ruckus around what the appropriate way to transfer and acquire agricultural land for any purposes other than agriculture. For this purpose, the Supreme Court has set a list of eight questions that need to be answered in this particular case.

The questions, simplified for language, are as follows:

1. What are the benefits of turning farmland into residential or commercial areas for the province/country?

2. Do people who invest in building societies but don’t use the land help create jobs, economic activity, and taxable income?

3. Does converting land for other purposes reduce the availability of farmland, impacting food security and increasing reliance on food imports?

4. Who has the legal authority to approve changes in land use and projects?

5. Is there a provision for offering land to low-income individuals by providing smaller plots?

6. Should decisions about such important matters be made by elected representatives?

7. Do large-scale land conversions contribute to environmental harm, pollution, and climate change?

8. How do laws like the Transfer of Property Act, Registration Act, and Stamp Duty Act apply to these situations?

These are the questions that will determine the future of agricultural land and real estate development in Pakistan. For some years now, the government has been working towards discouraging the use of Green Areas for residential real estate development. However, as Ali Amin Gandapur expressed a decade ago as revenue minister of KP, there is no law in place that can help tackle it.

The ideal solution to these problems is through legislation. But in the absence of this, depending on the answers the SC finds to these questions, a precedent could be set. This would mean that in the future if a project begins on agricultural land, the matter could be taken to court and the developer would have to answer the questions. It might not be an ideal situation, but it is very much a start. n

TEXTILES 24 AGRICULTURE

Pakistan can become a cannabis powerhouse.

The only problem is getting through the bureaucratic labyrinth

It is high-time Pakistan reaps the benefits of the hemp crop. But what exactly is the potential of growing this crop and what has been standing in the way?

By Shahnawaz Ali

The plains of South Asia, due to their geographical advantages, provide irrigation opportunities for many crops. Some of these crops hold a staple food status while others are essential for industrial activity. But one crop that perhaps has great uses in the industrial pharmaceutical sectors, is not only considered sinister, but invokes larger debates on a social, religious and most importantly regulatory level. That plant is Cannabis.

In recent years, the debate surrounding cannabis legalisation has swept across the globe like wildfire, igniting passions, sparking contro-

versies, and challenging long-held beliefs. Yet, in Pakistan, a nation steeped in tradition yet eager for progress, the discourse takes on a unique flavour—one shaped by a complex interplay of history, politics, science and economics.

However, the former President of Pakistan, Dr. Arif Alvi, in one of his last acts in office, gave his approval for the Cannabis Control and Regulatory Authority Ordinance 2024. The ordinance allows for the cultivation, extraction, refining, manufacturing, and sale of cannabis derivatives for medical and industrial purposes. While the ordinance is promised to expand horizons for Pakistan’s export sector, it is important to dive into what those horizons are and why has it taken Pakistan so long to realise that Cannabis can be grown.

What is Cannabis?

Cannabis, often referred to as marijuana or hemp, unlike its reputation, is an immensely versatile plant. This plant has been cultivated for thousands of years. Belonging to the Cannabaceae family, cannabis is known for its distinct leaves, serrated edges, and iconic five-leaf arrangement.

It comes in several varieties, each with its unique characteristics and properties. The two primary species of cannabis are Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, with Cannabis ruderalis considered a third, lesser-known species.

Cannabis sativa: Known for its tall stat-

27 AGRICULTURE

ure, narrow leaves, and long flowering cycles, Cannabis sativa is typically grown in equatorial regions with ample sunlight and warm temperatures. Sativa strains are prized for their energising effects, making them popular among recreational users.

Cannabis indica: In contrast, Cannabis indica is characterised by its shorter, bushier stature, broader leaves, and shorter flowering cycles. Indica strains are often cultivated in cooler climates and mountainous regions, where they thrive in environments with shorter daylight hours. Indica varieties are valued for their relaxing and sedative effects, making them sought after for medicinal and therapeutic use.

With rich landscape having access to equatorial plains and towering altitudes, Pakistan is a country, who’s soil is conducive for the growth of both the Indica and the Sativa varieties.

Why Cannabis?

Apart from the well-known recreational use, the cannabis plant offers a plethora of byproducts and uses, ranging from medicinal and therapeutic applications to industrial and commercial purposes.

Cannabis contains a myriad of compounds known as cannabinoids, including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), which interact with the body’s endocannabinoid system to produce various effects. Medicinal cannabis products, such as oils, tinctures, and capsules, are used to alleviate symptoms of conditions such as chronic pain, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and nausea, among others.

Beyond its medicinal and recreational uses, cannabis has a long history of industrial applications. Hemp, a variety of cannabis with low THC content, is valued for its fibrous stalks, which can be processed into textiles, paper, building materials, and biofuels. Hemp has been used in textile production for thousands of years due to its versatile and durable properties.

Hemp fibres are extracted from the stalks of the cannabis sativa plant and processed into yarns or threads. These fibres can then be woven or knitted into various types of fabrics, ranging from lightweight and breathable materials to heavier, more durable textiles.

Pakistan currently relies mostly on cotton to run its fabric industry. Once the crown jewel of Pakistan’s agriculture industry and the backbone of our textile export economy is now barely making its ends meet. This makes hemp-textile an option all the more explorable in the recent past.

Hemp seeds are also rich in protein and essential fatty acids, making them a valuable

ingredient in food products such as hemp milk, protein powder, and cooking oil.

Why not?

So with so many apparent business use cases, what has stopped Pakistan from growing hemp?

For starters, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961 categorises cannabis as a Schedule I controlled substance, subject to strict controls and regulations. Article 28 of the convention specifically addresses the cultivation of cannabis, stating that parties to the convention must limit the cultivation of the cannabis plant to licit purposes, such as medical and scientific research, and ensure that the illicit cultivation of cannabis is prohibited and penalised.

As a signatory of the treaty, Pakistan has had a similar stance regarding the treatment of cannabis. However, one can note that article 28 clearly states that the cultivation for licit purposes is not prohibited. Why then did Pakistan never think about growing hemp?

Before answering this question, it is important to note that the question refers to the state regulating the growth. Pakistan- as a region has been growing cannabis for more than thousands of years, a tradition often unaffected by international treaties. From the religious significance of the substance for various minorities to the recreational abuse, Pakistan has seen it all, except for the monetary benefits. According to UNODC’s National drug user survey, more than 4.5 million people are completely dependent upon drugs.

Another reason for a hushed silence regarding the cannabis regulation is Pakistan’s historically maintained strict anti-drug laws, which have hindered the legal cultivation of cannabis. While the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961 allows for regulated cultivation for medical and scientific purposes, the interpretation and implementation of these provisions within Pakistan’s legal framework, of criminalising possession and cultivation poses challenges. Cannabis has also long been associated with drug abuse and illicit activities in Pakistan, leading to cultural and social stigma surrounding its cultivation and use.

Why now?

The story of Pakistan’s cannabis renaissance does not trace its roots far back. It was as recent as 2020 when Fawad Chaudhry, the PTI science minister dared to come forward with an opportunistic future. As Minister for Science & Technology, he became a champion of the cause of production of industrial cannabis/ hemp. Since the hemp plant could be harnessed for everything from textiles to medicine, the science minister assumed jurisdiction.

However, like most of PTI’s endeavours, Chaudhry’s vision was not without its detractors. With the government of PTI out of office in 2021, the science ministry still eyed the cultivation of hemp. Around this time, Nawabzada Shahzain Bugti, the minister for narcotics control approached Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif saying that hemp relates to marijuana and his ministry should be the regulator of hemp trade and cultivation.The Ministry of Narcotics Control, wary of the plant’s association with its domain, had already stood as a formidable obstacle, threatening to stifle the nascent green revolution before it could even take root.

And hence the federal cabinet decided to shift the mandate of the hemp issue from the science ministry to the narcotics ministry in December, 2022.

The ministry of science pushed on, rallying for support from like-minded individuals within the government and beyond. Their efforts bore fruit in the form of the “National Industrial Hemp and Medicinal Cannabis Policy,” a groundbreaking document that laid the groundwork for Pakistan’s journey into the world of cannabis regulation.

This document was prepared by the ministry of science and was shared with the anti narcotics, food and commerce ministries. The federal cabinet in the PDM-tenure made a committee making both the science and narcotics control ministers, chairmans of the committee.

With the document released in early 2023, and the Ministry of Narcotics Control on board by mid 2023, the policy hit another bump in the road when the ministry of food came looking for a share in the cannabis pie. The issue was however resolved as the policy saw its final stamp of approval on 26 February. With its passage, Pakistan signalled its commitment to international conventions on narcotics control while charting a course towards a more enlightened approach to cannabis regulation.

A Global Perspective

Pakistan’s cannabis renaissance is not just a local affair—it is part of a larger global movement towards legalisation and regulation. As countries around the world grapple with the social, economic, and political implications of cannabis legalisation, Pakistan stands at the forefront of this paradigm shift, offering lessons and insights that resonate far beyond its borders.

As shared by the initial ministry of science report to the cabinet, the global cannabis industry is expected to grow by almost $100 billion by 2026, making it very difficult to ignore. With the favourable climate that Pakistan has, experts feel that this should have been on the country’s agenda years ago. n

28 AGRICULTURE

Secure goes for IPO, becoming first logistics company to do so

The company will be the first logistics based company to be listed on the stock exchange

By Zain Naeem

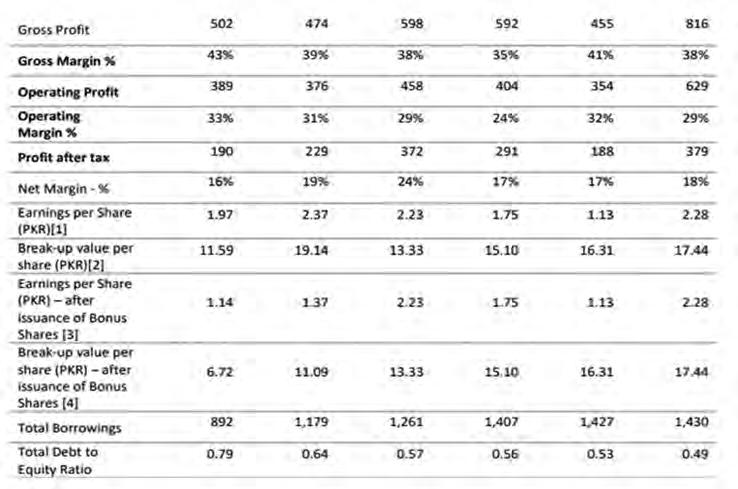

In what will be a first for the sector in Pakistan, a logistics company in Pakistan is set to be listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX). The book building process of Secure Logistics Group completed and the strike price decided for the Initial Placement Offer (IPO) is at Rs. 12 per share with a subscription of 50.7 million shares being subscribed.

The book building process took place on 27th and 28th of March 2024. The company wants to issue 50 million shares and raise Rs. 600 million from the public offering which will make up 18.27% of its shareholding after

the IPO is carried out. The base price for the issue was set at Rs 12 per share after which the book building process has determined the actual strike price at which the IPO will be subscribed.

It is important to note that the company had filed for a listing back in 2022 for nearly 56 million shares at a floor price of Rs 27 per share. In the older prospectus, the company was looking for more than double the investment which has been revised downwards in the latest prospectus. The previous request for listing was revised and a new prospectus was approved by the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) to go for an issue of a smaller size and value.

So what is Secure Logistics, what does it do, and why are they going public now?

Secure Logistics Group

Secure Logistics Group Limited, formerly Asia Capital Partners (Private) Limited, is a company which is involved in the logistics industry and specializes in transportation of goods in long-haul category. The company is an umbrella corporation which owns SecurLog (Private) Limited, Secure Track (Private) Limited, Fist Security (Private) Limited and TDM (Private) Limited. These entities are involved in logistics, asset tracking, vehicle fleet management, security services and commodity trading businesses. The company considers long haul services its major revenue generator as more than 90% of its revenues come from this category.

At this point in time, there are no listed companies which are associated with this sector and most of the industry is characterized by high levels of competition with the leading companies having a market share of less than 2%. The landscape is primarily made up of family run and owner owned businesses which have an average fleet size of 70 to 100 vehicles. Some of the leading names in the industry are Allied Logistics, BSL (Private) Limited, DHL Global Forwarding Pakistan (Private) Limited, TCS (Private) Limited and National Logistics Cell.

Purpose of the IPO

The company’s current objective is to deleverage significantly by using the proceeds from the IPO to pay off its debt obligation. This strategy aligns with the goal of shielding the company from the financing costs associated with the historically high interest rates. The loan to be repaid is owed to its sponsors, while the amount owed to one of the sponsors, Karandaaz Pakistan, is to be converted into equity worth Rs 237 million. Additionally, a portion of the funds will be allocated towards upgrading the fleet, enhancing human resource capacity, marketing, and expanding the company’s market outreach.

Recent consolidated results show that the company has improved its sales and revenues with the recent year expected to cross Rs 2 billion in terms of revenue.

Apart from the interest rates, one of the biggest risks that the business is exposed to is a potential rise in fuel costs. As an expense, the company considers 55% of its cost only

29 STOCK EXCHANGE

associated with fuel charges with toll expenses and depreciation coming in at 20% and 15% respectively. This means that any change in international oil prices will pose a threat to the company’s bottomline.

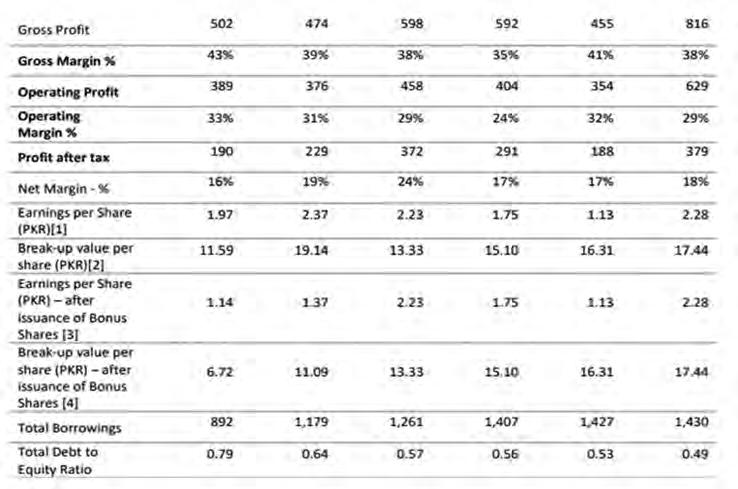

However, Secure Logistics is able to deal with these costs by transferring the impact on to their customers. Due to this, the company enjoys a high gross profit margin allowing it to retain around 40% of its revenues as profits. The operating profit margin and net profit margin are also healthy and shows that the company earns, on average, 30% in terms of operating profit margin and 20% net profit margin.

Industry experts

As this is a new sector that is being ventured into, many of the brokerage houses are not covering the company or the sector as a whole. Still a general sentiment is that due to the slowdown in the economy, high energy cost and load axle implementation, the sector is facing difficulties.

In company specific analysis, even though the track record of the company seems to be consistent, industry experts feel that the industry is saturated to an extent. The logistics industry is seen as being fragile while operating in a volatile economy. They also point towards the fact that the company is looking to pay off its debt and deleverage itself by spending more than 85% of the proceeds on debt servicing which could be better used by expanding and improving the fleet. There is also a concern that the current fleet of the company is 37 vehicles which is far less than the industry average of 70 and needs to be supplemented to enhance revenue potential.

There is also a word of caution in terms of the risks that the company will face as this is the first IPO in the market of a logistics company and a comprehensive understanding of all the risk factors will need time to surface.

Mohammad Aitazaz Farooqui, Head of Research at Providus Capital, feels that the company is asking for a multiple that is five times its floor price which is based on past IPO share subscriptions. “I think the lucrativeness of the scrip is low given the cheap valuations available in the market. Plus the purpose of the issue is to pay off debt rather than invest in the business.” He points towards the fact that investors would be comfortable with a mix of debt and equity to

I think the lucrativeness of the scrip is low given the cheap valuations available in the market. Plus the purpose of the issue is to pay off debt rather than invest in the business

Mohammad Aitazaz Farooqui, Head of Research at Providus Capital

amplify their return, however, the company is prioritizing debt payment currently.