Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor

Sub-Editor:

07

07

07 This is the fastest growing sport in the world. Can it take root in Pakistan?

07 As Interloop’s year-on-year profits surge, do the recent quarter’s hiccups indicate a shift in trajectory?

10 Pakistan owes a lot of money to the world. Can it be paid back in time?

11 A policy abyss Ammar H. Khan

14

14

14 Time of Death: Pakistan’s Super-App Dream

14 The rate cycle has pulled the plug on private credit. Is there any recourse?

16 How inflation killed Retailistan

18 Pakistan’s precarious financial state: debt levels surge to unsustainable levels

19

19 Productive policies or PR fluff — How useful were the interim government’s IT initiatives?

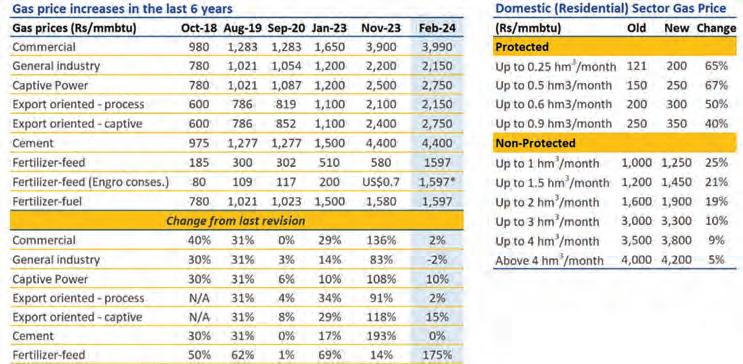

22 Rifts in cabinet, vested interests, and arm twisting — Inside the IMF directed gas price hike

23 Need raw materials? Zaraye hopes you’ll turn to them

24 The magic pill for the pharma sector

Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani

Amir

CON TENTS

Multimedia:

Basit Munawar - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi | Fawad Shakeel

#1 business

- your go-to source for business, economic and financial

profit@pakistantoday.com.pk Profit Profit CONTENTS

Business Reporters: Daniyal Ahmad | Shahab Omer | Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Ghulam

|

Shehzad Paracha | Aziz Buneri | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Urooj Imran | Shahnawaz Ali | Meerub

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Sohail Abbas (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Pakistan’s

magazine

news. Contact us:

22 18 10 10

As Interloop’s year-on-year

profits surge,

do the recent quarter’s hiccups indicate a shift in trajectory?

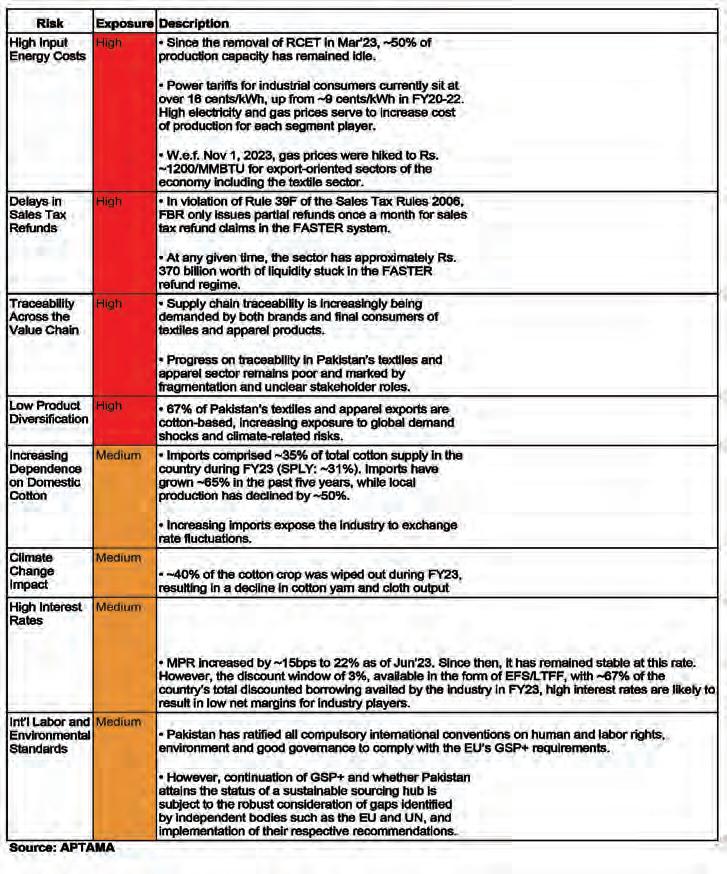

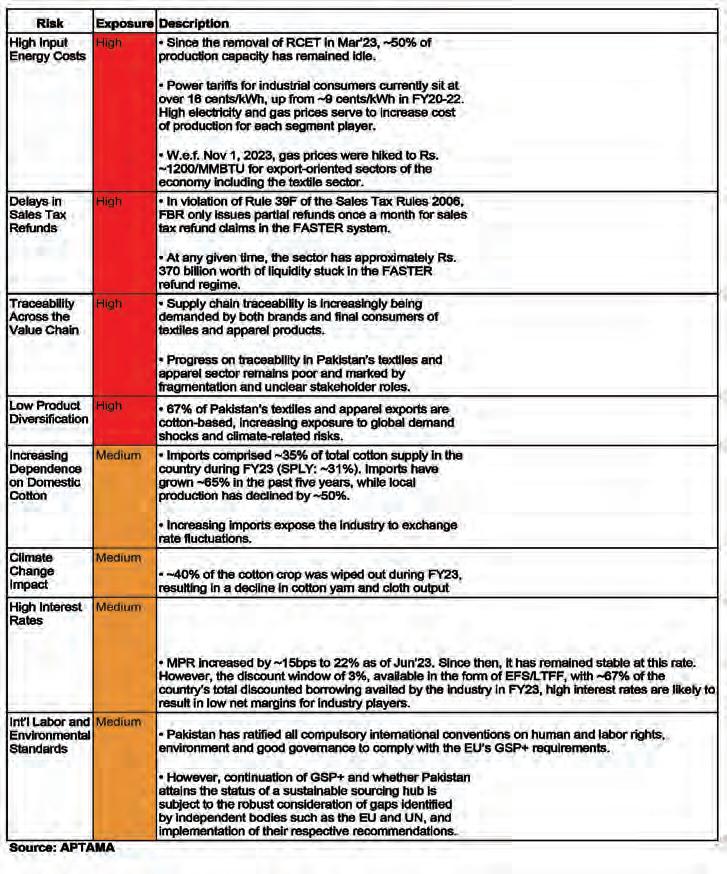

High energy costs and the appreciation of the Pakistani Rupee took a toll on the export giant’s performance

By Saneela Jawad

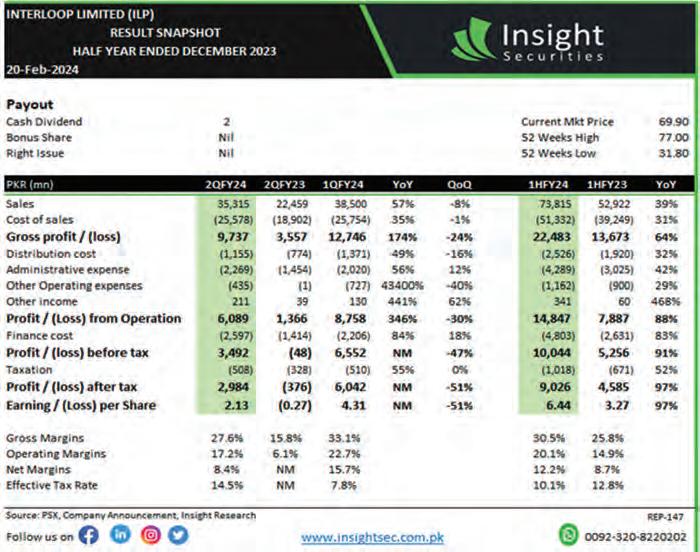

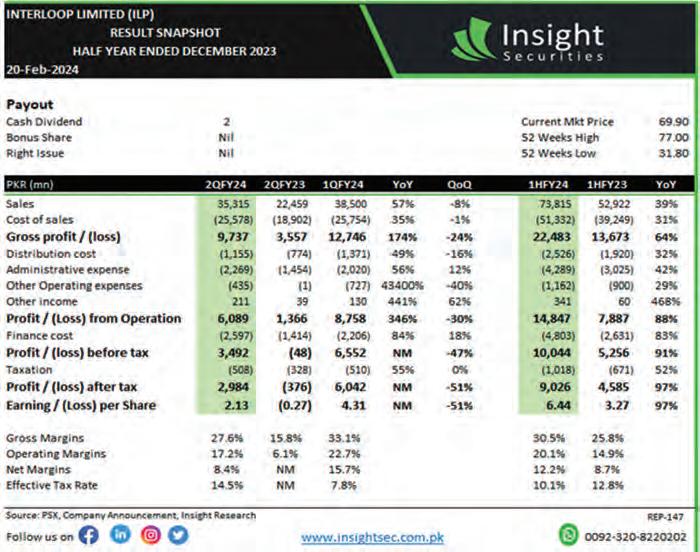

Interloop Limited, a leading textile enterprise, has reported its impressive half-year financial results for financial year (FY) 2024, ending in December 2023. The company has showcased a remarkable surge in net profits, nearly doubling from Rs 4.6 billion in FY 2023 to Rs 9 billion in FY 2024.

Interloop has five distinct business segments each catering to specific markets and needs. The hosiery segment produces 796 million socks annually for global brands like Nike and Adidas.

The denim segment, renowned for its eco-friendliness, currently produces more than 500,000 sustainable garments monthly with plans to expand by 2025.

Apparel, attracting brands from various continents, features a new eco-friendly facility with advanced machinery and sustainability features, producing 22 million garments annually.

The activewear segment has a capacity

of 4 million pieces annually, utilising advanced machinery and a dedicated design team. Finally, the yarns segment spins 32 million pounds annually, using recycled and sustainable fibres. Over 50% is used internally: while the rest is supplied to other manufacturers.

Previously, Interloop Limited defied a turbulent global and domestic economic landscape to deliver strong results in FY 2023, showcasing its resilience and adaptability.

“The global economic slowdown further dampened prospects, impacting Pakistan's GDP growth and causing a decline in textile exports. Pakistan's textile industry, in particular, faced a 14.6% drop in exports, with knitwear, readymade garments, and bedwear experiencing significant declines,” read the company’s director report for 2023.

The recent half-year financial report highlights a significant uptick in sales, soaring by 39% from Rs 53 billion in FY 2023 to Rs 74 billion in FY 2024. Correspondingly, the gross profit experienced a substantial leap of 66%, escalating from Rs 14 billion in FY 2023 to Rs 23 billion in the current financial year.

This upswing in revenue and profit can be largely attributed to Interloop's acquisition of a majority stake, 64% shares, US firm Top Circle Hosiery Mills, consummated in December 2023. The acquisition aligns with Interloop's strategic vision aimed at augmenting shareholder value, fortifying its global market presence, and bolstering its long-term sustainability, as reported by Profit earlier.

Despite the substantial increase in revenue and profit, expenses witnessed a marginal escalation in the first half, attributable to the burgeoning inflationary pressures in the economy. Distribution costs surged from Rs 1.9 billion in FY 2023 to Rs 2.6 billion in FY 2024, while administrative and operating expenses rose to Rs 4.4 billion and Rs 1.2 billion, respectively, in the current financial year.

Nevertheless, the operating profit doubled in the first half of FY 2024, scaling from Rs 7.9 billion to Rs 15.7 billion. With the company registering an overall profit, the earnings per share surged to Rs 6.4 in the current financial year from Rs 3.3 in the preceding year.

Delving into the quarterly performance,

7

the data reveals a deterioration across key metrics. Sales fell by 8%, from around Rs 39 billion in the first quarter of financial year 2024 to Rs 35 billion in the second quarter. Similarly, the gross profit declined by 24% in the latest quarter, falling from Rs 12.8 billion to Rs 9.7 billion. Profit from operations plummeted by 30%, from Rs 8.6 billion to Rs 6.1 billion.

The appreciation of the rupee eroded export competitiveness while rising gas prices added another layer of pressure on production costs. This, coupled with persistently high finance costs led to a decline in earnings in the recent quarter. Resultantly, quarter on quarter profitability suffered as net profit margins were down from 22.7% to 17.2%.

Challenges and beyond

Interloop and the broader textile industry face a complex situation marked by promising growth, erratic gas supplies, and a looming cotton shortage.

While grid power is available, the indus-

try relies on gas-fueled captive power plants for electricity generation due to the unreliability and high cost of government supply. However, the industry is facing a challenge

with reliance on imported Regasified Liquefied Natural Gas (RLNG) and declining domestic reserves, which is impacting its captive generation capabilities.

As per Wasi Haider, a research analyst at an energy think tank based out of Islamabad, “The textile sector has relied heavily on affordable gas to fuel its captive power plants due to concerns about the government grid's reliability. Additionally, energy obtained directly from the government is relatively costly, making textile exports less competitive.”

“Following 2022, the RLNG crisis escalated, leading to a rise in the weighted average cost of gas as expensive fuel was integrated into the local mix. Consequently, the substantial impact on cross-subsidies disproportionately affected export-oriented sectors like textiles. As a result, major textile industry players are now confronted with an energy dilemma, with revised gas prices resulting in nearly 45% of cross-subsidies,” he added.

Despite these challenges, the industry has seen positive developments. The depreciation of the Pakistani rupee in the first half of the year made exports cheaper, boosting competitiveness.

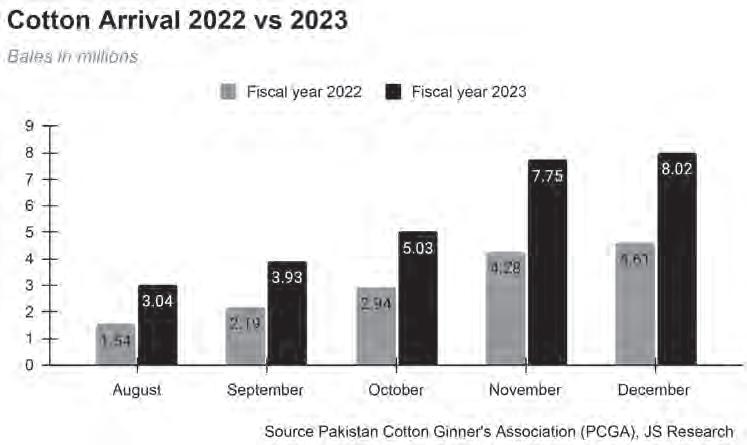

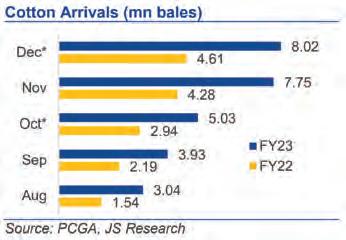

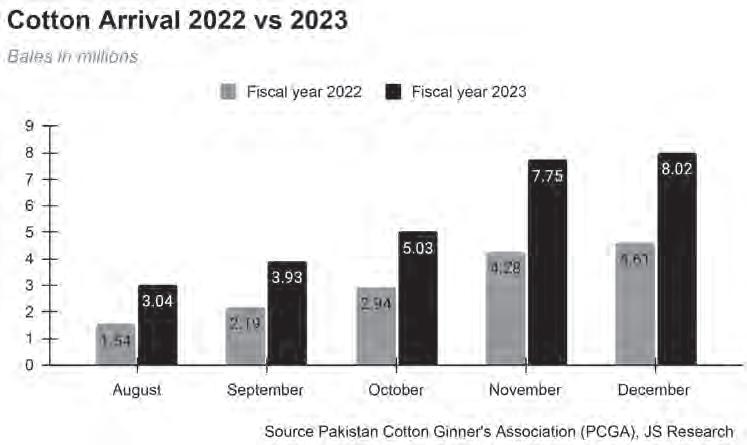

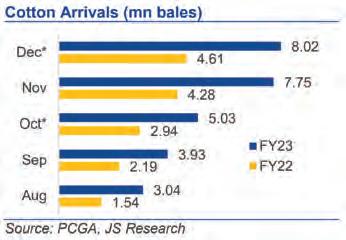

The recent cotton harvest surged by 67% compared to the previous year. Additionally, lower cotton prices initially benefited mills, and significant operational expansion in the past year increased production capacity. However, domestic demand exceeds current production, necessitating imports.

As per an analyst note by JS Global Capital, “Pakistan remained as one of the cheapest sources of cotton, when compared to regional exporters. Local prices have reached $0.73/pound compared to last month's average of $0.75/pound. When compared to the global producers, Pakistan remained the cheapest source of origin compared to $0.9 for benchmark Cotton A Index. Global prices

8

“Following 2022, the RLNG crisis escalated, leading to a rise in the weighted average cost of gas as expensive fuel was integrated into the local mix. Consequently, the substantial impact on cross-subsidies disproportionately affected exportoriented sectors like textiles. As a result, major textile industry players are now confronted with an energy dilemma, with revised gas prices resulting in nearly 45% of cross-subsidies

are expected to remain soft on weaker global demand when compared to last year, lower imports by Bangladesh, Pakistan and Turkey will be slightly offset by higher volume in China and Brazil.”

Similarly, the record-high cost of borrowing and the phasing out of the export refinance scheme by the State Bank at the request of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have continued to put pressure on the bottom line.

The JS analysis also emphasizes that the rise in short-term financing rates (due to the gradual phasing out of Export Finance Schemes - EFS) and the increase in working capital requirements resulting from year-onyear higher procurement needs will continue to weigh down the bottom line for textile players. The EFS rate, previously fixed at 3% until March 2022, was later linked to the benchmark policy rate with the spread

gradually reduced to minus 300 basis points by December 2022. In accordance with IMF recommendations, the EFS rate will gradually align with the benchmark rate.

This, in particular, also impacts Interloop due to the high levels of leverage it carries on its books. As per the company’s 2023 audit report, Interloop has significant amounts of borrowings from banks and other financial

institutions amounting to around Rs 60 billion, accounting for 73.9% of total liabilities.

For Interloop, however, strategic acquisitions and diversification played a crucial role in the past two quarter’s performance. The company expanded its international presence and tapped into new markets, mitigating risks associated with any single region. Furthermore, a steadfast commitment to sustainability and innovation helped Interloop differentiate itself in a competitive landscape. In August 2023, Interloop made an investment of $100 million towards sustainability and expansion in circular knitting capacity. This move is accompanied by ambitious Science Based Targets (SBTi) approval for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 51% by 2032.

This made Interloop the first large-scale Pakistani textile company with SBTi-approved targets. The company is committed to reducing both direct and indirect emissions, investing in clean energy and process improvements. The report also stated that the expansion plans include opening a new high-tech apparel plant in Faisalabad which will produce 50 tons of fabric and 3 million garments monthly.

Additionally, Hosiery Plant VI is planned for the 2023-24 financial year. The company plans to further expand its international presence and explore new markets, while staying committed to responsible manufacturing practices.

Following the acquisition of Top Circle Hosiery Mills in December 2023, Interloop has successfully diversified its revenue streams, thus mitigating the adverse effects of inflationary pressures on its operations. This strategic move underscores the company's commitment to sustained growth and resilience in an ever-evolving market landscape.

While promising opportunities exist in the form of recent export orders and anticipated rate cuts, challenges like gas supply issues, cotton sourcing, and volatile currency fluctuations demand pose a threat to the company’s performance. n

Wasi Haider, Research Analyst at an energy Think Tank based out of Islamabad

10

By Shahnawaz Ali

Nobody really wants to be prime minister right now. Well that isn’t strictly speaking true. We’re almost certain that Anwar ul Haq Kakar or any other number of technocrats would love to swivel around in the PM’s chair and jet to and from different countries. What we mean is that no serious politician with any concern for their future in public service would find the current climate less than ideal to get in the driving seat.

There are many reasons why of course. Pakistan is at a corner where the country desperately needs nation building and reconciliation. There is political and social turmoil. The democratic process is broken and Pakistan’s position in the diplomatic world is hazier with every passing day. But perhaps the biggest problem we have is the money. Pakistan owes a lot of money to a lot of different lenders. And while domestic debt and be wiggled out of one way or the other, when international partners come knocking the sweat glands start doing overtime.

But what exactly does Pakistan owe? And how are we planning on paying it off?

How we got here

It is a question of bad habits really. Just look at the past 15 odd years. In 2008 democracy returned to Pakistan and the PPP surged to power. This was the start of Pakistan being on its own after an era of geopolitical significance due to first the cold war and then the war on terror.

In the last 15 years, each party has used different techniques to balance the country’s deficits, by using external finance, one way or the other.

The PPP government in 2008 came into office on the verge of a global financial crisis. The situation warranted them to go on a liberal but necessary borrowing spree. Fortunately for them, not many people were out lending money, especially commercial creditors. During their tenure the government debt increased from Rs 6.44 trillion to Rs 15.1 trillion. This was a 135% increase in a five year period. As a percentage of the GDP, government debt had increased from 62.8% to 67.2%.

For the PML-N government coming in around 2013, the silver lining was that the PPP’s borrowing policy relied more on domestic than external borrowing. Much of this had to do with the prevalent economic conditions around the world, where the Great Recession significantly reduced the ability of economies like Pakistan to borrow money from the international bond market. This meant that the total government external debt increased

by only 22pc between 2008 to 2013, going from $42.8 billion to $52.4 billion.

The PML N government when they came to office in 2023, did not have an ideal environment, yet the international market had recovered from the 2008 financial crisis and Ishaq Dar, with the right mix of borrowing and spending, could steer Pakistan in a better direction. Dar’s immediate priority became securing loans from multiple bilateral partners who obliged. During this time Pakistan was also able to secure an IMF program that helped steady the ship.

Over the four years that PMLN spent in office, Pakistan’s external account went up from $60.49 billion to $77.9 billion. Pakistan saw a period of growth but both the commercial and bilateral loans saw a spike. These 4 years more or less had the oversight of Ishaq Dar, PMLN’s long standing finance whizz and someone who is famous for his compulsive control of the economy.

Come the PTI government, Pakistan’s external account saw a meteoric rise from $77.9 billion to $128.92 billion till they were eventually ousted in 2022. During this tenure, the PTI government also tried a number of candidates for the position. Starting with Asad Umar, the long marketed maestro who turned the Engro Corporation around, the PTI government was quick to toss the hat around to Hammad azhar, Imran Khan himself and eventually the same Shaukat Tarin who served in the PPP government as well.

During this period Pakistan received not only multilateral but a lot of bilateral and commercial loans. In particular short term loans saw a rise that proved to be a shot in the foot for Pakistan.

Where we stand

Over the last two years, Pakistan has grappled with twin deficits—a rising fiscal deficit and a surging current account deficit—leading to an increased reliance on debt. This has shot up Pakistan’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 60% to over 75%, as per the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The domestic debts themselves have reached an unsustainable level, with just the interest payments constituting more than 40% of the fiscal budget.

However, a greater threat looms in the form of the persistent foreign exchange liquidity crisis, worsened by the substantial burden of external liabilities.

External debt of Pakistan refers to the total amount of financial obligations that it owes to foreign creditors. This debt includes borrowings from various sources outside Pakistan, such as other countries, international financial institutions, and commercial lenders.

Funds acquired through external debt

are deployed to finance development projects, meet budgetary requirements, and address balance of payment deficits. Components of external debt may include bilateral and multilateral loans, bonds issued in the international capital markets, and other forms of borrowing. Hence, any failure to timely disburse external debt has far reaching repercussions on any country.

The government closely monitors and manages external debt to ensure the country’s financial stability and economic development. With a new government about to step into the office, Pakistan’s external account needs to be steered with more care than ever. To look at it in more detail, it is important to look at the external account numbers.

Where do we stand?

One thing that makes the external debt profile harder to predict is the lack of available data. While it is known that Pakistan’s total external debt and liabilities as of December 31st stood at $131.16 billion, we have little to no details on the schedule of the maturities. However, one can obtain quite a snapshot to make sizable estimates of the country’s financing needs for the servicing of external debt, through various reports from the State Bank, the IMF and other sources.

During the State Bank of Pakistan’s latest Monetary Policy Statement briefing, while responding to a question the SBP governor, Jameel Ahmed stated that Pakistan has already paid off a sizable part of its external debt for FY24. According to Ahmed, Pakistan’s external debt payments for 2024 amounted $ 24.5 billion, of which around $3.8 billion was interest payments. He further stated that of this amount, almost $10 billion is due to be paid, of which $5 billion is expected to be rolled over by the respective creditor.

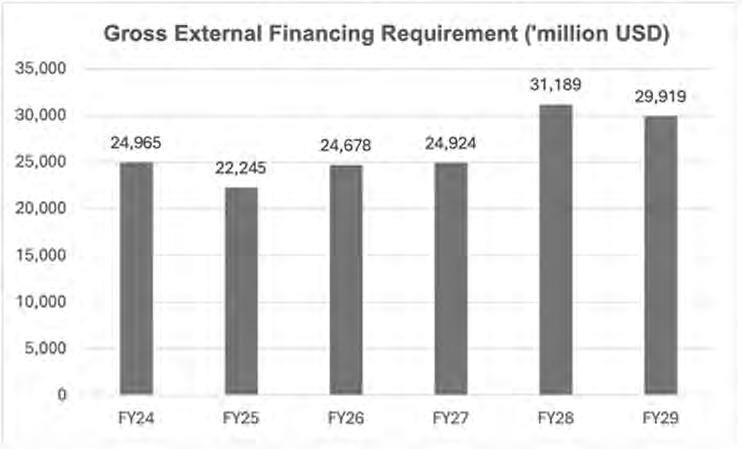

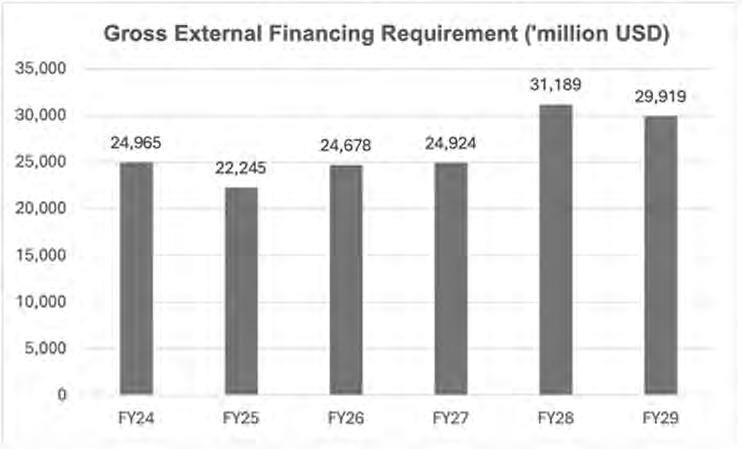

Pakistan’s external financing need has also been thoroughly covered in the latest IMF 1st review under the Standby Arrangement. While we have an idea for what amount of dollars Pakistan will need to conclude this year, as shared by the State Bank. Based on various growth and repayment indicators, the IMF predicts Pakistan’s external financing requirements for the upcoming years as follows:

As a percentage of GDP, Pakistan requires an average >6% of its GDP to only meet its external financing needs. While analysing the external account of Pakistan, the IMF staff commentary states that, “Pakistan’s external debt is predominantly to bilateral and multilateral creditors. Although the maturity structure is set to lengthen over the projection horizon, the high share of short-term debt poses risks to debt sustainability and will require timely disbursements from these creditors.”

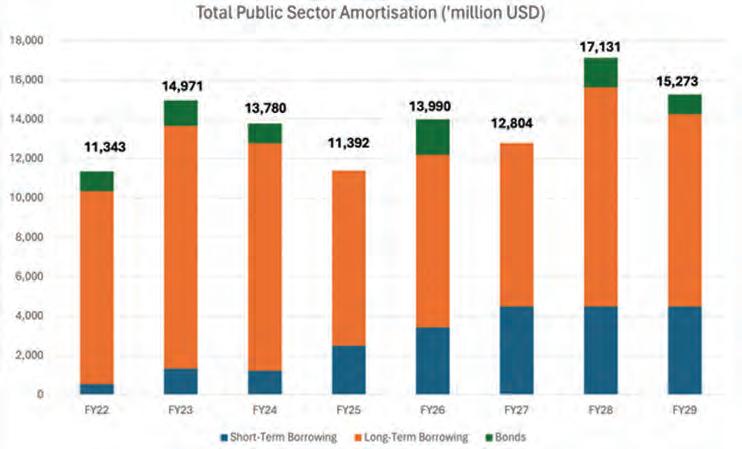

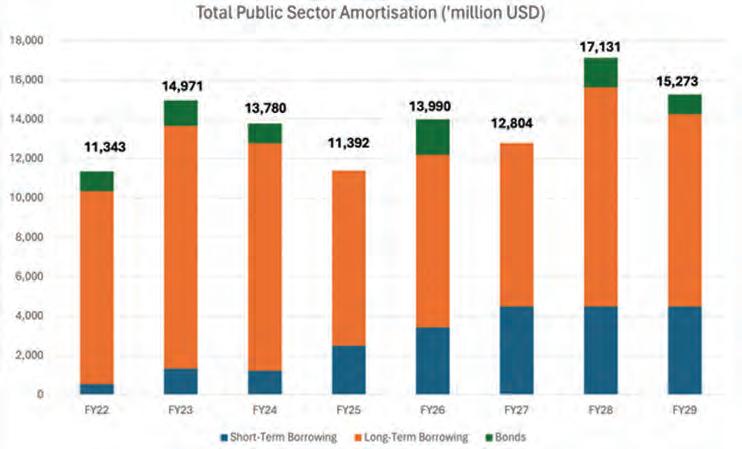

Following is the schedule of projected

COVER STORY

amortisations of Pakistan’s public sector debt. It can be seen that the short term debt obligations increase periodically over the next 4 financial years, causing repayment concerns. Moreover, as mentioned in the earlier SBP briefing, Pakistan is looking to roll over, not just a significant portion of this year’s obligation, but expects similar facilities from bilateral partners in the coming years. That increases the amount of amortisation for the subsequent year, and also raises interest payment significantly.

Source: IMF review

government. This move might not prove to be sustainable provided that Pakistan will have to let the imports flow once the manufacturing market equilibrium is restored. Pakistan might hold off on it for this year, but shrinking the size of trade up until 2028 would raise a completely different kind of problem.

Another reason why the external debt outlook is grim is because Pakistan currently stands at its historically highest ever level of external debt. Even after an optimistic IMF estimate, the figure is expected to go up, almost

bilateral and multilateral creditors extend their full support in the form of rollovers and program loans in the coming years. The report also assumes a Foreign Direct Investment number in excess of $1.5 billion owing to privatisation receipts that have been ensured by the current caretaker government.

External Debt projections

Even though the IMF finds some respite in Pakistan’s ability to secure high amounts of short-term loan, project loans, and other funds, one thing that still remains questionable is the sustainability of this “financing”. After all this is also borrowed money and comes with a deadline. In fact, the IMF projects Pakistan’s total external debt and liabilities at $147.7 billion by FY28, 20% higher than the current level.

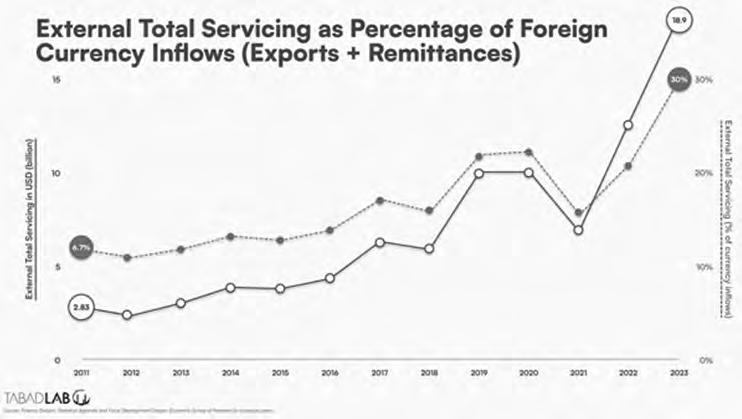

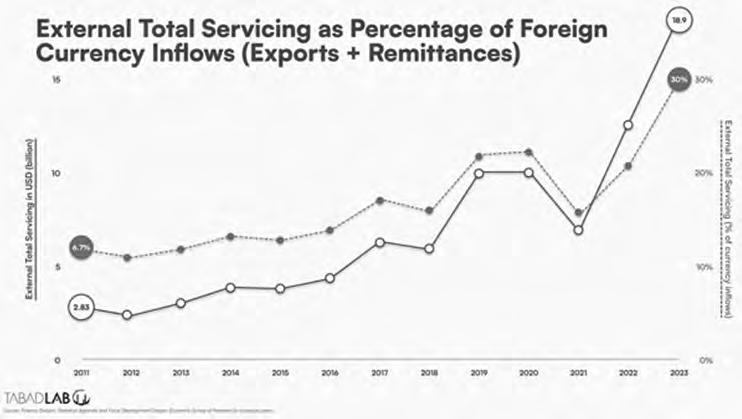

A recent report by Tabadlab, an Islamabad-based think-tank, points out this pattern calling it “a raging fire” in their latest report. Ammar H. Khan, an independent economic analyst and the lead author of this report states that, “We are essentially stuck in a low-growth trap, with our reliance on import-financed consumption oriented growth not working anymore. Perpetual fiscal deficits will keep fueling more inflation, as the sovereign continues to borrow to bridge its deficits. To grow at 4%+ annually, we need incremental debt of $15bn+ every year. This can’t go on for long, till we retool the economy from consumption oriented, to investment, and export oriented growth.”

CAD management

The amortisation of debt, however, is just one aspect of the external account. The developed world does not rely on external finance, but rather its own current account to meet its forex needs. The simplest way to do it is by increasing revenue (Exports, remittances etc).

Source: IMF review

Since the IMF report is for the end of September 2023, as the year progresses, it becomes clearer that the graph above presents an optimistic picture of the economy. The IMF estimates come from a rather miserly estimate of the current account deficit, based on a controlled import regime during the PDM-led

10% faster than the GDP growth itself, increasing Pakistan’s debt to GDP ratio above 80%.

It is important to note that these projections are done on the basis of some crucial assumptions; that current account numbers remain optimistic, and that Pakistan gets into another long term IMF program and that all its

Over the last two years, Pakistan has been able to manage its current account deficit, by controlling imports. This ensures low volatility in currency value and subsides a balance of payments crises. However, as a result of quashed imports, the exports have not been able to grow even to their 2021 levels. While this is seen as a standard response under an economic slowdown of 2022-23, the IMF expects Pakistan to fall back to its older importing habits once some stability is restored. As of now Pakistan’s cumulative imports for the first half of FY24 is $25.25 billion, an amount considerably lower than the IMF projections.

Recently the IMF asked Pakistan to increase the imports by 45% for the disbursement of its final tranche. The fund is expected to maintain its liberalised imports stance, for

12

any future programs. As per estimates, Pakistan badly needs to be in an IMF program to be able to meet its financing needs, not just from the funds but by its bilateral partners. Failure to comply with any condition set forth by the fund could hence put a dent in these already bad numbers.

The only way out of the “Raging Fire,” as mentioned in the Tabadlab Report, is to boost the country’s income potential. A graph from the aforementioned report clearly shows how Pakistan’s forex inflows have become insufficient for even paying off the external debt requirements. The requirements that are expected to rise meteorically, as discussed above.

assess its future repayment capacity under revised terms.

If one is to look at sovereign debt restructuring, it can be categorised into three kinds as a policy measure; Strictly Preemptive, Weakly Preemptive (likely for Pakistan), and Disorderly Default.

The process itself consists of initiation, negotiation, and implementation stages, with the government seeking assistance from the IMF for a Debt Sustainability Analysis in the initiation phase.

Negotiations then take place with major creditors such as the Paris Club, World Bank, China, Saudi Arabia, and commercial credi-

The task of controlling the balance of payments through the current account may seem tedious but right now it stands as Pakistan’s most viable option.

Is a restructuring on the cards?

Another possible way of solving this crisis is by restructuring debts.

This would offset Pakistan’s public amortisations to a point in the future, allowing for more breathing space in the coming years. However, restructuring external debts is not as easy as restructuring domestic debts. It is important to note that domestic debt restructuring itself is no piece of cake.

Sovereign debt restructuring is a multifaceted process involving a government’s plea to lenders for principal reduction, lowered debt servicing costs, or extended maturity dates. If such a scenario were ever to emerge in Pakistan, this process will be initiated by the economic advisory committee and cabinet, conducted discreetly to prevent market disruptions.

Lenders typically seek exemption from restructuring, and the country must carefully

tors, with the guidance of established bilateral frameworks like the G20 Common Framework. During this stage, all creditors must be offered comparable treatment as urged by the G20’s framework, and a committee of creditors is also formed. Lastly, implementation of the restructuring process can take time, 2 years and counting for example, in Zambia’s case. During this time, multilateral institutions like the IMF may provide additional financing to keep the country afloat. However, multilateral creditors are generally given preferred creditor status and are not a part of the restructuring

arrangements.

However, past commentary by the finance division states that Pakistan might not be looking at the option. As per the Finance Minister’s media interaction at the end of last year, the majority of Pakistan’s external debt, 44%, is held by multilateral agencies and cannot be reprofiled due to their “preferred creditor” status.

Commercial debt makes up 14% of the external debt, and restructuring this portion is challenging due to the involvement of numerous stakeholders and a cumbersome process. Bilateral debt represents 35% of the external debt, and the government has already benefited from the payment moratorium G-20 debt relief initiative following the COVID-19 pandemic.

This means that while restructuring is one option, it is not being looked at as the go to option for Pakistan’s external debt.

The calm before the storm?

As the caretaker government steps out of the office claiming to have effectively managed Pakistan’s debt portfolio, the country enters a highly crucial phase of economic management. A latest Bloomberg report confirms Pakistan’s need for a long-term IMF program, worth $6 billion, once the elected government comes into office.

The economy, and in extension the external account, requires extreme management in the next 5 years with an adequate finance minister that salvages the growth potential while navigating the challenges.

Only a messiah well-poised and disconcerted from political point-scoring can now steer Pakistan out of this upcoming storm. A person well-versed in fiscal consolidation and well reputed at the IMF, if Pakistan were to enter, and carry out another IMF program.

While we do not have the name for who this messiah is likely to be, a majority of Pakistan stands clear on who it should not be. As put by former finance minister Miftah Ismail in a podcast interview, the ideal candidate for the finance minister seat is ABD (Anyone but Dar). n

COVER STORY

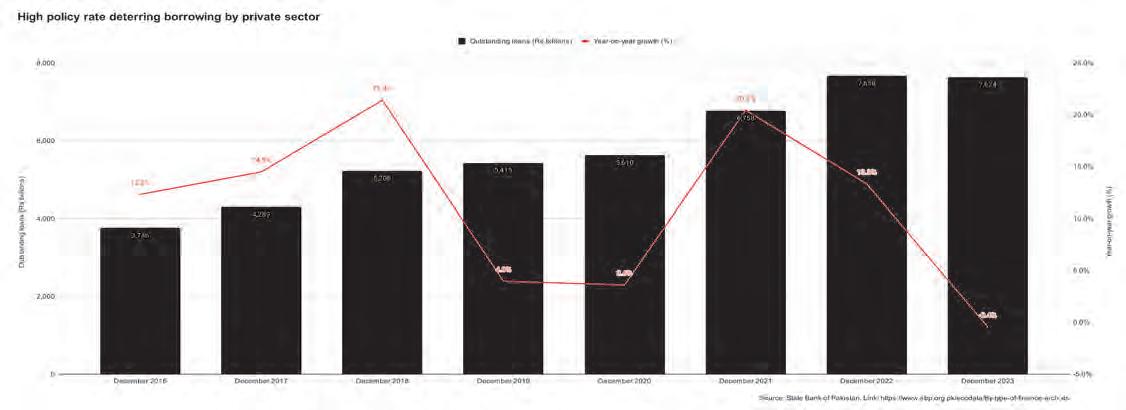

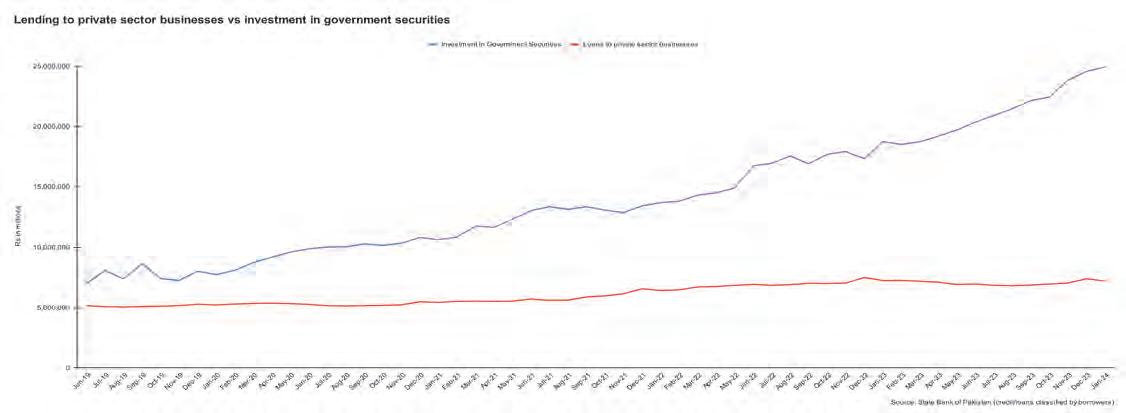

The rate cycle has pulled the plug on private credit. Is there any recourse?

High policy rate deter private sector borrowing while banks divert liquidity towards government securities

By Mariam Umar

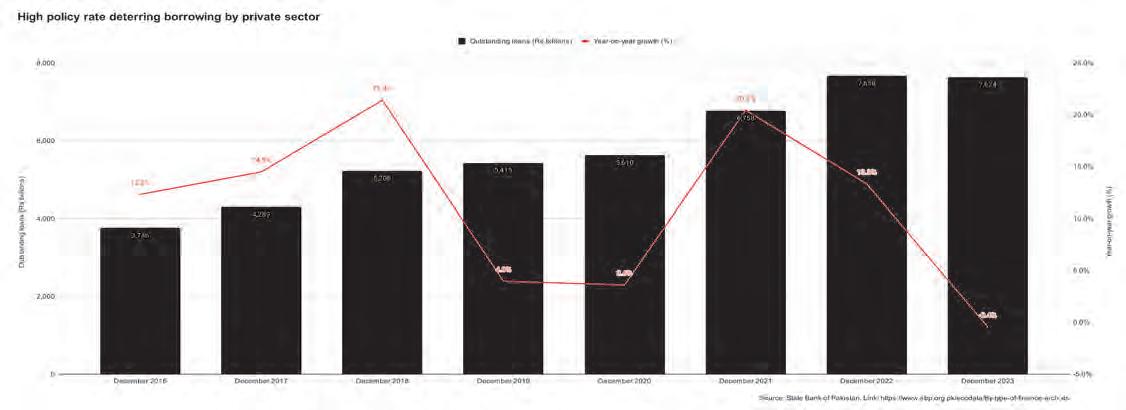

Amidst the flourishing profits of commercial banks, driven by rising interest rates, a narrative of stark inequality emerges, leaving private businesses and individuals struggling with the tightening grip of limited borrowing opportunities.

Interest rates in Pakistan soared to an all-high level of 22% on June 27, 2023, as the government scrambled to make last-minute changes to secure a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Since then, the policy rate has remained at the elevated level.

In a previous conversation with Profit,

Mustafa Pasha, chief investment officer at Lakson Investment Limited bemoaned the waning enthusiasm of banks to extend credit to private enterprises. “Private-sector borrowing costs have gone up due to high interest rates. Financing availability from banks has been reduced because banks are less willing to lend to the private sector and prefer lending to the government. Demand and supply for financing have gone down, squeezing private-sector credit. This also means that greenfield projects and new investments have decreased while working capital requirements have increased.”

While analysts anticipate rate cuts in the coming monetary policy meetings, an elevated inflation rate remains a challenge.

The country has been fighting a losing battle with inflation, leading to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) maintaining interest rates at unsustainable levels. One of the conditions set by the IMF is to maintain a tight monetary policy to bring down inflation which means that a rate cut will only be possible if the inflation rate falls below the prevailing interest rate.

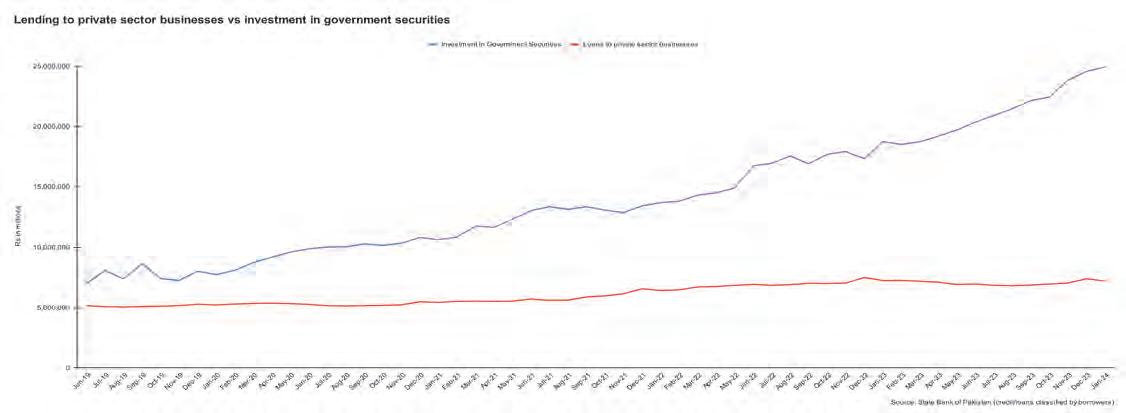

Given the persistently high interest rates with no sign of reprieve, commercial banks continue prioritising investment in secure government securities, over riskier private sector. At the end of December 2023, investment to deposit ratio stood at 91%. This means that the majority of the deposits with the banking sector are being lent to the

14

Private-sector borrowing costs have gone up due to high interest rates. Financing availability from banks has been reduced because banks are less willing to lend to the private sector and prefer lending to the government. Demand and supply for financing have gone down, squeezing privatesector credit. This also means that greenfield projects and new investments have decreased while working capital requirements have increased

Mustafa Pasha, chief investment officer at Lakson Investments

government, resulting in crowding out of the private-sector.

To explain the underlying trend in private credit, Profit reached out to Navid Goraya, Chief Investment Officer at Karandaaz Capital, a vehicle of Karandaaz Pakistan

that promotes access to finance for micro, small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs).

“Banks have become more cautious in lending to the private sector to avoid asset quality deterioration and have instead channelled available liquidity to government securi -

ties. Investment in government securities increased by 42% during 2023 to Rs 24.5 trillion,” explained Goraya. He attributed the squeezing out of private sector financing to a high policy rate. “In almost over a decade, we have first-time

BANKING

We are seeing stress across the SMEs as they are more sensitive to high-interest rates. Businesses are trying to grapple with the increased borrowing costs and many SMEs are using own-source funds to settle their commercially priced loans

Navid Goraya, Chief Investment Officer at Karandaaz Capital

witnessed a decline in advances to the private sector which fell by 0.4% year-on-year in 2023. Historically, there has usually been a double-digit growth in advances to the private sector.”

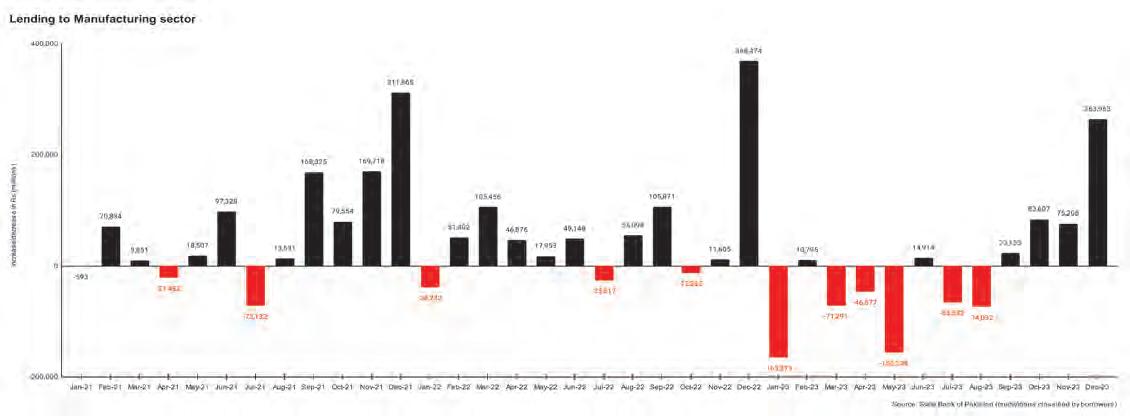

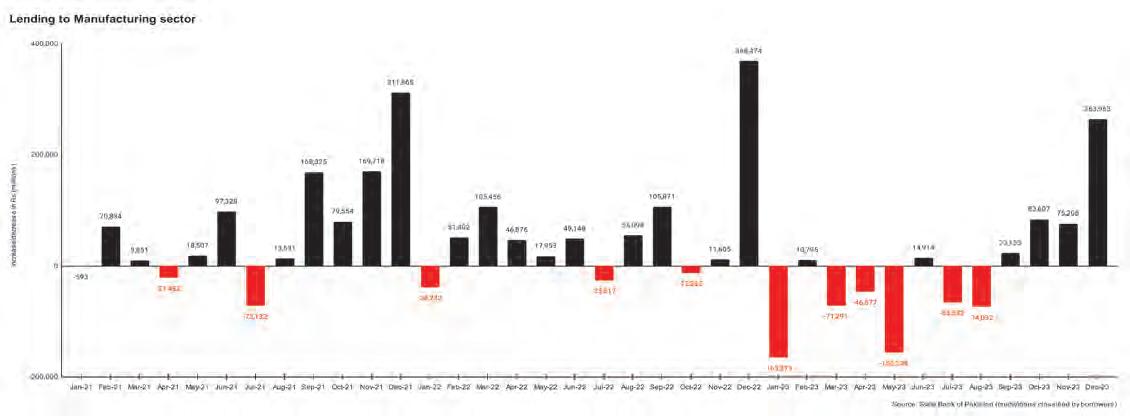

Within private sector lending, the manufacturing sector accounts for around 65-66% of total loans. Lending to the manufacturing sector declined by Rs 106 billion from Rs 4,955 billion in December 2022 to Rs

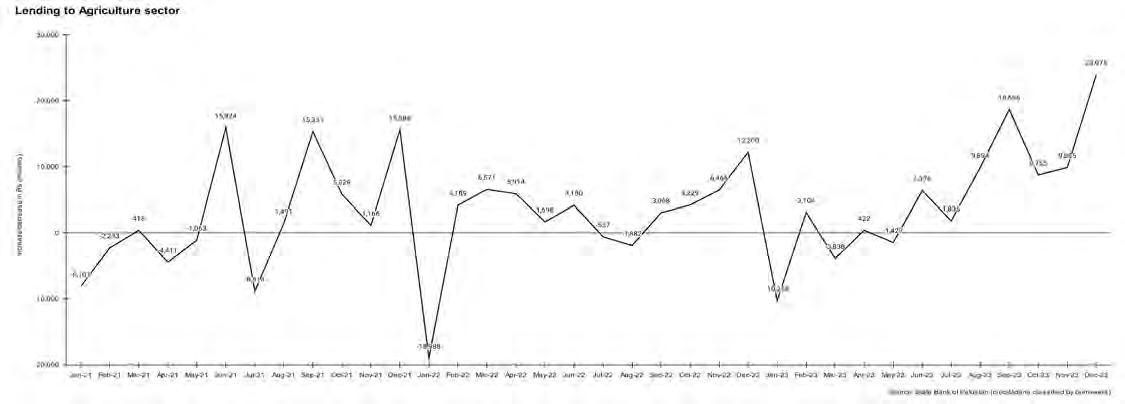

4,848 billion in December 2023. As the following chart shows, lending to the manufacturing sector declined for much of 2023, only picking up pace in the last quarter of 2023.

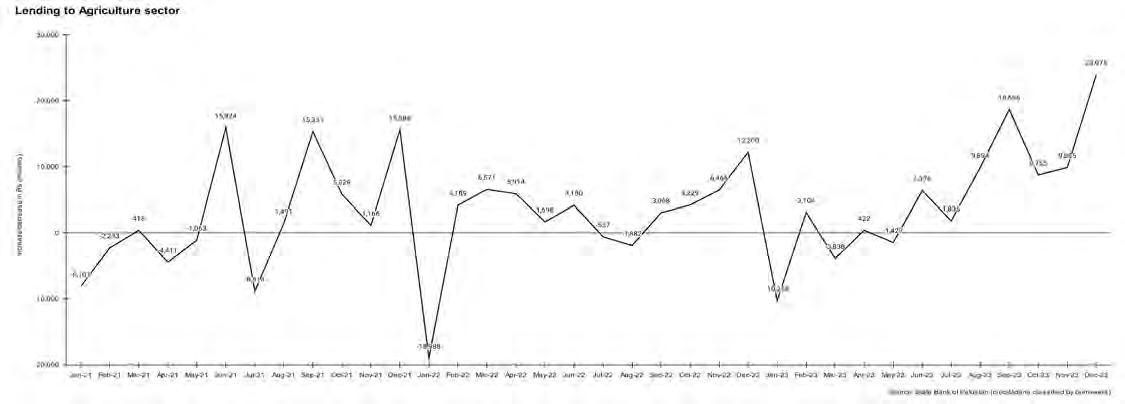

On the other hand, lending to the agriculture sector, which accounts for 6% of total lending to the private sector, increased in the second half of 2023. Overall, lending to agriculture increased by 19% from around Rs 350 billion to Rs 417 billion.

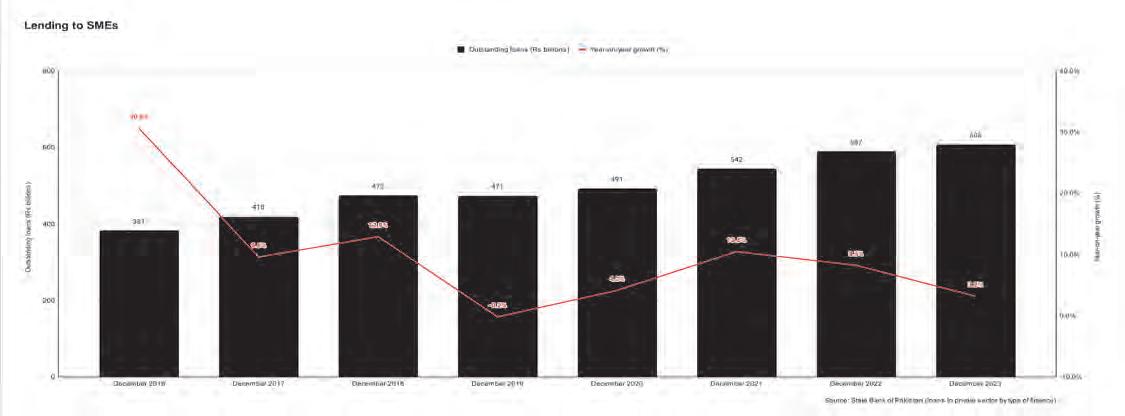

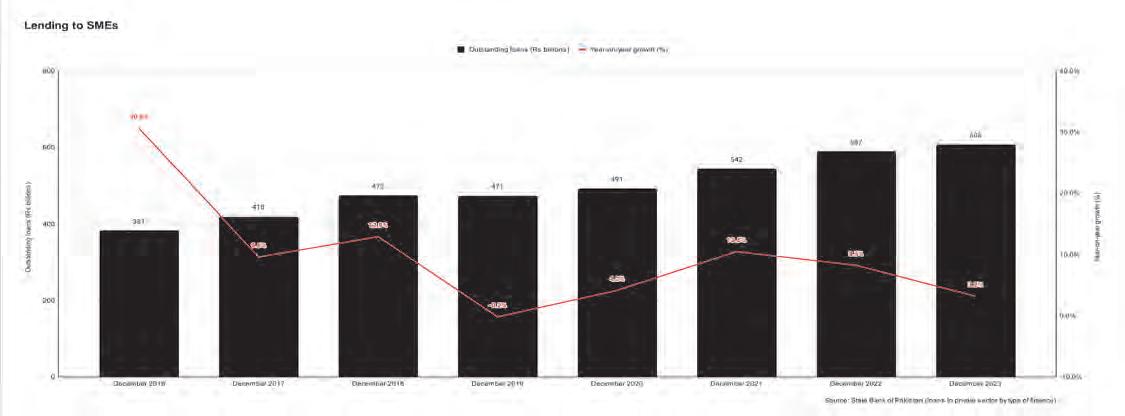

Loans to SMEs grew nominally by 3% from Rs 587 billion in December 2022 to Rs 606 billion in December 2023. Goraya voiced apprehensions regarding the impact of elevated interest rates on SMEs, noting, “We are seeing stress across the SMEs as they are more sensitive to high-interest rates. Businesses are trying to grapple with the increased borrowing costs and many SMEs are using own-source funds to settle their

16

commercially priced loans.”

At the same time, he advocated for increasing lending to SMEs. “While the subsidised SME Asaan Finance (SAAF) Scheme has cushioned SME lending, the overall size of the pie is still substantially low given there are more than 5 million SMEs in Pakistan.”

Goraya added that lending to SMEs accounts for less than 8% of overall private sector advances whereas their GDP contribution is around 40%.

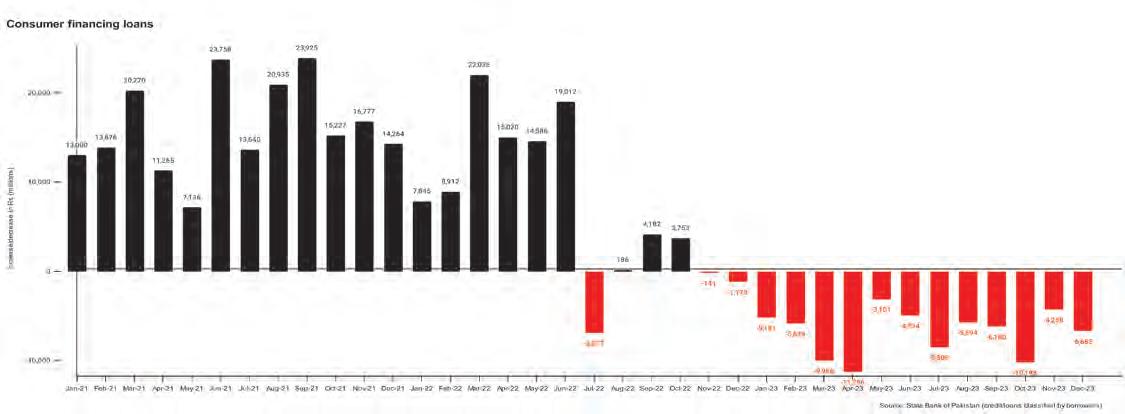

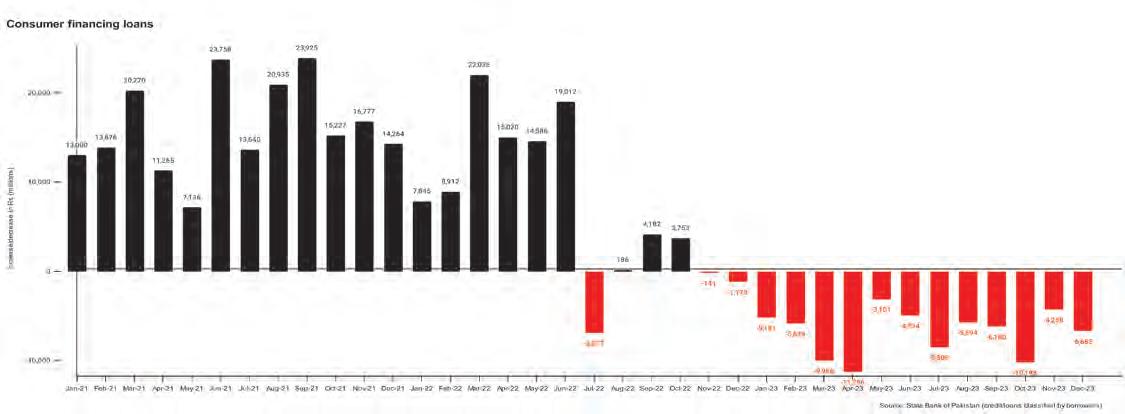

Much like private sector businesses, borrowing by individuals has also plummeted. Personal borrowing declined by Rs 22 billion in 2023 from Rs 1,143 billion in December 2022 to Rs 1,120 in December 2023. However, lending to bank employees has risen by around Rs 60 billion. On the other hand, consumer financing decreased by 9% year on year from Rs 900 billion in December 2022 to Rs 818 billion in December 2023.

In January 2024, consumer financing declined by another Rs 4.3 billion. While the overall trend in consumer financing

loans is on a downward trajectory, there is a contrasting surge in credit card usage. This increase in credit card usage could potentially be attributed to the inflationary pressures prompting individuals to rely on credit cards to finance their purchases.

The prohibitive costs of borrowing have dissuaded the private sector from seeking funding for investment and expansion endeavours. “The IMF also recently downgraded Pakistan’s GDP growth estimate for fiscal year 2024 to 2% from October’s estimate of 2.5%,” warned Goraya. However, Pakistan is at an economic crossroads. While a rate cut would make borrowing affordable for the private sector, a premature rate cut could lead to higher consumption and thus inflation.

Recent signals from the T-bill auction on February 21 indicate a potential delay in the interest rate cut cycle. In the T-bill auction that happened on February 21, market participation in three-month T-bills was the highest with bids worth Rs 649 billion

received, exceeding the 12-month paper for the first time in four months.

The three-month treasury bill yield bumped up by 126 basis points reaching 20.6998%. Similarly, the yield on the 12-month paper increased by 25 basis points to 20.33% while the yield on 6-month t-bills remained unchanged. “We witnessed major investor participation in the 3-month T-bill auction, most likely driven by expectations of a possible delay in the interest rate cut cycle, contrary to the previous market anticipation of such a cut in the March 2024 policy,” explained Sana Tawfik, deputy read of research at Arif Habib Limited in a note.

Analysts believe that higher inflation expectations in near future, political uncertainty, along with the upcoming last review of the stand-by arrangement (SBA) with the IMF, scheduled for March 2024, are the reasons behind the change in rate cut expectations. Hence, even though a rate cut is desired by the private sector, its timing and magnitude hinge on inflation’s trajectory. n

BANKING

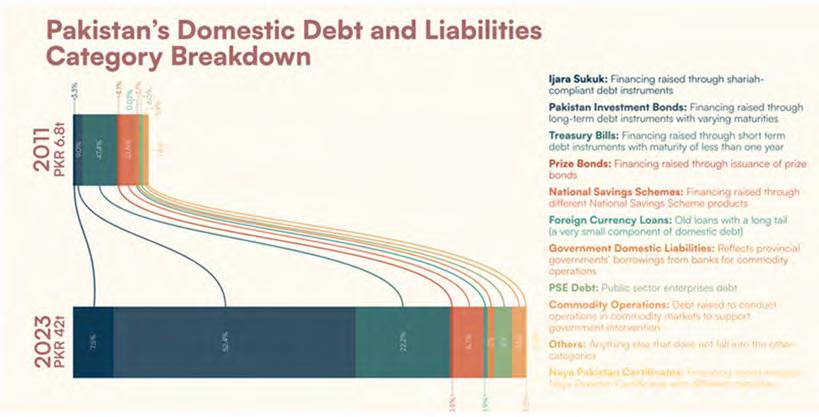

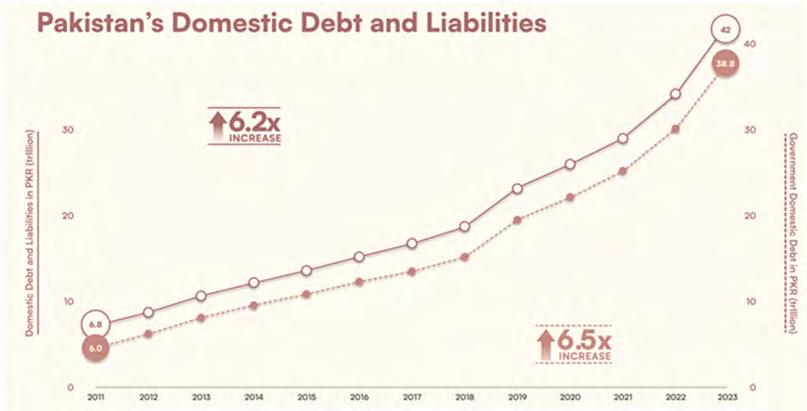

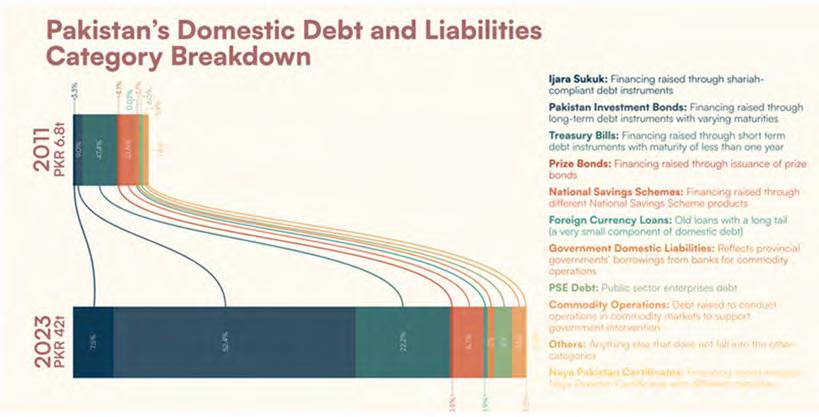

Domestic debt has increased by more than 6 times between 2011 and 2023

By Mariam Umar

By Mariam Umar

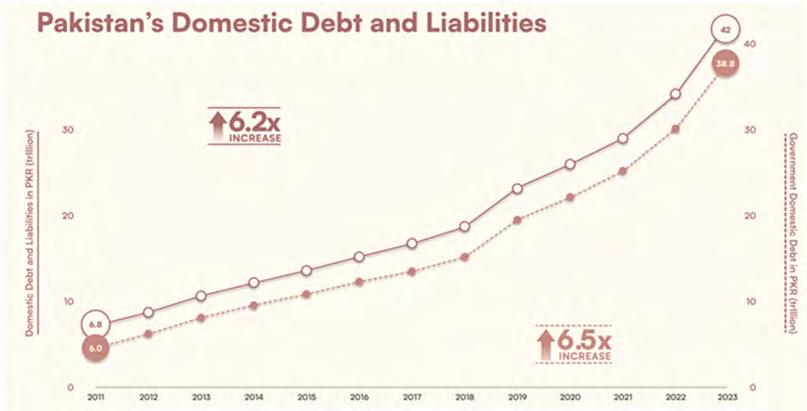

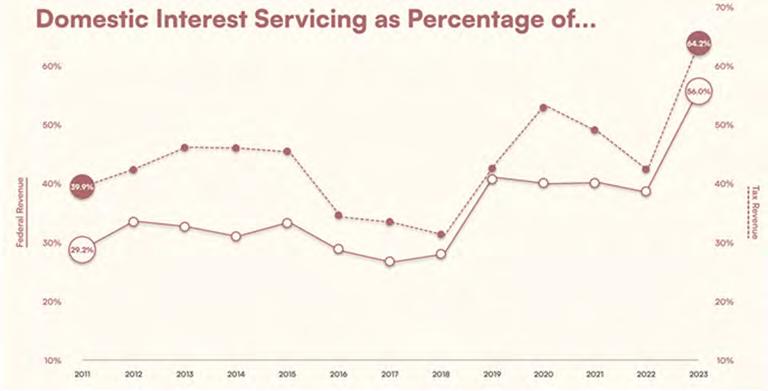

The debt dilemma in Pakistan has worsened as its borrowing has reached unsustainable levels. The escalation in debt, especially domestic debt, has been significant, surging by 6.5 times from 2011 to 2023. The details have been reported in a recent report by Tabadlab authored by Zeeshan Salahuddin and Ammar Habib Khan which describes the situation as “a raging fire.”

A matter of greater concern is that Pakistan’s debt burden is growing at a pace faster than the expansion of the economy’s net output (gross domestic product or GDP). This imbalance limits the economy’s ability to boost output. “This is unsustainable. It demands transformational change. Unless there are sweeping reforms and dramatic changes to the status quo, Pakistan will continue to sink deeper, headed towards an inevitable default, which would be the start of the spiral,” read the report.

The government frequently engages in

substantial borrowing from both domestic banks and international institutions to fund various expenditures, including ambitious infrastructure projects such as motorways. Domestic debt refers to the portion of debt owed to domestic creditors, primarily commercial banks. According to the think tank report, domestic borrowing is predominantly allocated to bridging the fiscal deficit, which arises from the disparity between government expenditure and revenues generated from taxes and other sources.

As per the report, in the last thirteen

18

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

by the Ministry of Finance on 22nd February 2024, the government was able to achieve a reduction of borrowing through government securities via the banking sector by 67% compared to the preceding period. The successful retirement of short-term Treasury Bills amounting to Rs 1.6 trillion further reduced the government’s gross financing needs.

years, Pakistan has had a fiscal deficit every year. “Low tax-to-GDP and high revenue-to-debt-servicing numbers serve as the root causes for reduced revenues, and increased expenses, both of which contribute to the fiscal deficit.”

However, the government has surpassed the revenue target set for the first half of the current fiscal year. Despite this achievement, the fiscal deficit has been on the rise due to increased federal expenditure. According to the January 2024 report of the Ministry of Finance, the consolidated fiscal deficit stood at 2.3% of GDP (Rs 2407.8 billion) in the first half of fiscal year 2024 against 2% of GDP (Rs 1,683.5 billion) last year.

What explains this is the meteoric rise in the price levels. Average inflation in the first seven months of fiscal year 2024 has been hovering at 28%-29% which has increased spending as well, forcing the ministry to increase borrowing from banks. As per the Finance Ministry’s January 2024 report, total expenditures surged by 45% to Rs 9,261.8 billion in the first half of fiscal year 2024, compared to Rs 6,382.4 billion the previous year. This increase was primarily driven by a 41% rise in current spending (dayto-day operational expenses).

Pakistan’s domestic debt

At the end of fiscal year 2023, the government’s domestic debt stood at Rs 38.8 trillion. According to the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) latest debt statistics released on February 13, 2024, the government’s domestic debt stock has increased to

Rs 42.6 trillion in December 2023, implying an increase of 10% in the first six months of the fiscal year 2024.

The government’s significant appetite for deficit financing through short-term domestic borrowing, coupled with record-high interest rates, has resulted in a dual crisis of elevated interest expenses and short maturity terms. Over the past year, the government has strategically focused on borrowing through T-bills and floating investment bonds (PIBs). Both options have led to substantial costs of debt servicing due to the prevailing high interest rates over the past year.

However, to address this issue, it appears that the government is now transitioning towards issuing longer-term bonds, which has been made possible by positive bids from market participants who anticipate forthcoming interest rate reductions.

According to the statement released

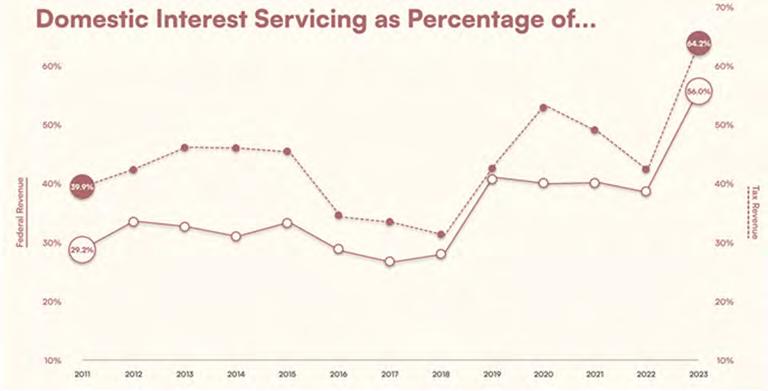

Additionally, the caretaker government shifted its domestic borrowing to long-term debt securities, focusing on floating-rate securities while borrowing fixed-rate instruments at rates averaging 3- 4 % below the policy rate. This strategic move increased the average time to maturity of domestic debt to around 3.0 years by January 2024, aligning with targets set in the Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy. However, domestic debt servicing consumes over half of the federal budget, resulting in a significant fiscal burden. As per the report by think tank, in fiscal year 2023, domestic debt interest servicing as a percentage of federal revenue and tax revenue stood at 64.2% and 56% respectively.

This means since debt servicing is prioritised, other sectors that need focus are often ignored. Similarly, “Climate financing takes a back seat to domestic debt servicing, further deteriorating climate vulnerability profile,” read the report.

Who is responsible for high domestic debt?

The roots of this debt escalation trace back to previous administrations. In the last fifteen years (2008-2023), domestic debt has cumulatively

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

MACROECONOMY

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

being the largest lenders to a bankrupt borrower will also have to bear the burden of this pain. The reduction of this debt will require a gradual approach, involving a combination of negative real interest rates, a moratorium/suspension of interest payments for, say, two years, an extension of the maturity period and even some writedown of its face value.”

He added that a substantial reduction in face value might erode the equity of banks, whose restoration will likely require loans to them at concessional rates and/or a short-term relaxation of the State Bank’s prudential regulations on capital adequacy.

What else can be done?

grown at the rate of 18%.

Following the victory in the 2008 general elections, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) assumed governance in late March 2008. By the conclusion of fiscal year 2008, the domestic debt amounted to Rs 3.26 trillion. However, by the end of the PPP’s tenure in fiscal year 2013, this figure had surged to Rs 9.5 trillion, (almost 60% of the GDP) reflecting a substantial growth of 23.9% over the span of five years.

In June, the reins of government were handed over to the Pakistan Muslim LeagueNawaz (PML-N). By the conclusion of their governance in fiscal year 2018, the domestic debt had reached Rs 16.4 trillion. This indicates that during the PML-N’s tenure, the domestic debt experienced a growth of 11.6%.

The difference in debt pattern was explained by economist Uzair Younus in an earlier article for Dawn. “The PPP’s borrowing policy relied more on domestic than external borrowing. Much of this had to do with the prevalent economic conditions around the world, where the Great Recession significantly reduced the ability of economies like Pakistan to borrow money from the international bond market,” wrote Younus.

Following the victory in the 2018 general elections, the Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf (PTI) assumed governance in August 2018 until April 2022. During this time period, domestic debt increased to Rs 31.1 trillion, a cumulative growth of around 17% in four years.

Following the ousting of Imran Khan, the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) took charge. During their tenure, domestic debt escalated by 25% in just one year, rising from Rs 31.1 trillion in June 2022 to Rs 38.8 trillion in June 2023.

By the end of September 2023, domestic debt had reached around Rs 39.7 trillion,

indicating a 7% increase under the caretaker government within four months.

Unfortunately, the bulk of debt accumulation has been used towards perpetuating a consumption-oriented economy with insufficient investment in productive sectors or industrial development.

Restructure domestic debt?

Experts believe that the country lacks the capacity to effectively manage the economic consequences of domestic debt restructuring.

In a previous conversation with Profit, economic analyst Ammar Habib Khan opined that the chances of domestic debt restructuring remain low. Instead, according to Khan, the government will be content with inflating away the debt due to gradually reducing the real value of domestic borrowing through the impact of high inflation.

Khan emphasised that the primary challenge does not lie in the current debt, but rather in the pressing need for liquidity to bolster reserves and support economic growth.

Similar sentiments were echoed by Yousuf Farooq, director of research at Chase Securities who opined that domestic debt restructuring is not required. In fact, he believes that domestic debt restructuring would permanently damage the financial system. Farooq emphasised on taxing untaxed sectors like agriculture and real estate instead of debt restructuring with the banking sector which already pays heavy taxes. The banking sector of Pakistan is one of the highest-taxed sectors in Pakistan, with effective tax ranging between 40-50% on average.

Shahid Kardar, former governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, wrote in his article for Dawn that banks might suffer as a consequence of domestic debt restructuring: “Banks

As suggested by Tabadlab in its report, the government needs to ‘de-risk the business environment’ to attract investors by bringing a stable legal framework to reduce risk. This entails implementing fiscal reforms to address the sovereign’s risk, which is exacerbated by uncontrolled spending and reliance on debt. Demonstrating the capacity for fiscal discipline is essential to lowering overall risk and fostering investor confidence. Similarly, maintaining policy consistency is vital, as investment tends to gravitate towards environments offering higher returns adjusted for risk. Political volatility and fluctuating policy decisions heighten risk levels.

Government discipline through prudent spending, prioritising public investments, and resource efficiency holds the key to mitigating the fiscal deficit. Another frontier is to expand the direct tax net and include retailers and wholesalers in the tax net while simultaneously increasing property taxes.

Analysts at Tabadlab also stress the importance of privatising State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Similarly, expanding public-private partnerships with rigorous governance can help combat inevitable elite rent-seeking behaviour. Doubling down on its efforts, the government should also consider establishing an export-oriented industrial policy, reducing trade barriers, and incentivizing the redirection of credit and capital to local firms to enhance productivity, boost exports, attract increased foreign direct investment, and improve the current account balance.

While all the suggestions from the think tank are valid and supported by sound analysis, implementing even half of them would necessitate a firm and decisive approach from the government. However, in the current political climate where questions persist regarding the clarity of mandates, the feasibility of carrying out such measures seems like a distant prospect.

20 MACROECONOMY

Rifts in cabinet, vested interests, and arm twisting — Inside the IMF directed gas price hike

Everyone is cribbing and complaining about the price increase except one voice from within the fertiliser industry

By Abdullah Niazi

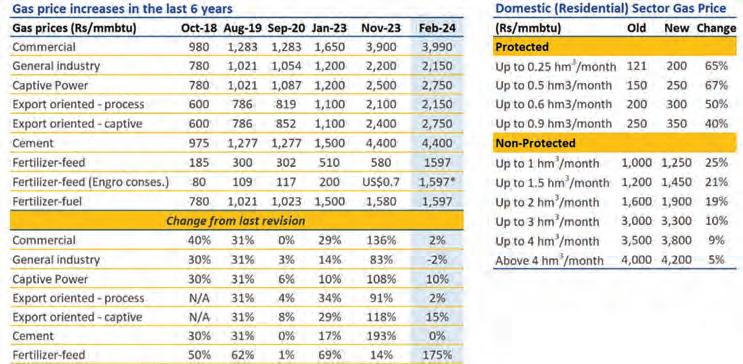

Tensions were running high at the Economic Coordination Committee meeting on Tuesday the 13th of February. The query on hand that was raising the temperature of the room was a proposal to increase the price of gas for domestic and industrial consumers by up to nearly 70% in some cases.

One could say that reaching consensus on the agenda item had gone past its deadline. You see, the IMF had instructed the government to revise the price of gas for different kinds of consumers by the 1st of February. The caretaker cabinet, perhaps too busy managing the load of the 2024 election, conveniently forgot to make a notification announcing the increase. The IMF then sent a gentle reminder that an announcement should be made by the 15th of February. Not only that, the fund specified that the increase in gas prices would be effective from the 1st of February even if the actual prices were announced on the 15th. Meaning that for all intents and purposes consumers using gas for the first half of February were doing so with no clue as to what rate they were buying it at.

But what choice did the government have? The IMF is dangling a vital $1.2 billion tranche over Pakistan’s head. And if the price of gas is not increased the fund will not be happy with Pakistan’s progress and not release the money. Despite the urgency of the matter, the ECC meeting on the 13th failed to reach consensus on what should have been a relatively simple decision.

So what was going on? According to a source privy to the meeting, at least four members of the ECC either opposed the proposal to increase the price of gas or wanted to delay the decision. At least two of those opposing

the proposition raised objections about the increase in prices for domestic consumers. Our source from within the cabinet claims that some of the members opposing the increase in price were those that had interests in industrial connections of gas as they were themselves industrialists.

The meeting was adjourned without a resolution, and another meeting of the ECC called on Wednesday the 14th of February to finalise the gas price hike. This second meeting ended up finalising the price increase which will be counted effective from the 1st of February.But what final shape did this increase take?

The increase has hit industrialists and in particular the fertiliser industry. But as the details become more apparent, it is clear that some in the fertiliser industry are more directly affected than others. Companies like Engro and Fatima Fertilizers will be affected more directly compared to Fauji Fertiliser. So how does this work?

The increase in question and circular debt

There is a reason the IMF wants to increase gas prices in Pakistan. Very briefly put, Pakistan does not have a lot of gas but we use it like we do. The IMF, as part of the ongoing programme, wanted to increase the price of gas for all domestic and commercial consumers.

You see, Pakistanis have gas cross subsidised. This means that the natural gas we produce is given to different consumers at different rates. There is one category of protected consumers which get it at the cheapest possible rate. These are small domestic consumers that use gas below a certain amount and tandoors that make rotis. Even within this protected

category there are slabs and everyone is charged differently based on how much they consume. Essentially, bigger consumers end up subsidising smaller consumers.

And while this is a people friendly policy and popular for political decision makers, it is also unproductive. Because we don’t have a lot of gas available, the IMF and other bodies such as the World Bank have always felt that gas should be used by industries for productive purposes rather than by domestic consumers to power stoves and heat water. This particularly becomes a problem in the winters, when the domestic need for gas increases, governments end up cutting it to industrial users.

The gas industry circular debt is a relatively new situation caused by rising LNG costs and delays by the government in announcing the new and higher tariff consistent with the international gas price hikes. Another contributing factor is the government’s inefficient utilisation of this commodity coupled with untargeted subsidies.

The fundamental cause of the circular debt is the unpaid government subsidies intended for residential and export-oriented consumers for the consumption of LNG. This has hampered Sui Northern Gas Pipelines (SNGPL) and Sui Southern Gas Company’s cash flows (SSGC) as they are not able to recover the actual cost of importing LNG from their respective customers.

To make the point clear, LNG costs a lot more than domestically produced gas, therefore naturally the price should be set at a level that would allow the recovery of the costs. But that is not the case as the government diverted the expensive LNG to domestic consumers which cannot afford to pay for it. This has resulted in ballooning receivables from the twin gas distributors on the balance sheets of energy exploration corporations, primarily the Oil and Gas Development Company (OGDC) and

22

Pakistan Petroleum Ltd (PPL). To summarise it, the government has not paid up the subsidy amount it owes to SNGPL and SSGC for providing gas at lower rates than what it actually costs. The debt is parked within other state owned enterprises, as is the common practice of the government.

The new rates

The IMF ideally wants gas to come to its original price instead of being cross subsidised, which might result in domestic consumers in particular switching to electricity. In fact, one of the most ideal scenarios for the IMF and indeed for industrial consumers is that domestic consumers switch from using gas to cook their food and heat their water to using electricity. The only problem is that domestic consumers are used to cheap gas. Electric cooking ranges, for example, are a rarity in Pakistan. Similarly electric geysers and water heating systems have simply not developed. This is despite the fact that at their real prices, and particularly with solar solutions, electricity is much cheaper than gas.

The gas price hikes reflect this. Just take a look at how the prices have increased. Domestic protected consumers and tandoors have had their rates hiked by up to 70% in some cases. Similarly the non-protected category has seen an increase in prices of up to around 25%.

But the real shift is in the subsidies that were being provided to industrial consumers. The first round of gas price increase took place back in November 2023. Back then commercial connection rates were raised by 136%, and the biggest increase was in the cement sector which saw a hike of around 193%. The fertiliser industry was still protected, however. This particular price hike has been gentler on these sectors and has instead focused on the fertiliser industry which has seen an increase of 175% in gas prices.

The ECC Chairman and Finance Minister Dr Shamshad Akhtar stated in the meeting that gas prices should be rationalised for the fertiliser plants that were availing the subsidy being

paid by bulk, power, industrial, cement and compressed natural gas (CNG) consumers. The subsidy of Rs 39 billion on feed and fuel gas for Engro Fertilisers was withdrawn and the ECC approved a new rate of Rs1,597 per mmbtu.

At the same time, certain quarters also complained of the price hike. The Chairman All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) North Kamran Arshad has strongly opposed the proposed increase in gas price for Export Oriented Units (EOUs) from Rs2400 to Rs2950/ MMBTU, saying that this increase would be disastrous for the textile industry. He was addressing a hurriedly-called press conference at the APTMA Lahore office on Wednesday. He was accompanied by Senior Vice Chairman Asad Shafi, Former Chairmen Adil Bashir, Rahim Nasir and Secretary General APTMA Raza Baqir. Chairman APTMA said that the gas tariff was Rs1100/MMBTU in January last year which was uplifted to Rs2400/MMBTU in November 2023 and is now expected to be raised to Rs. 2950/- MMBTU from the current month.

The fertiliser sector and Engro’s good fight

And then there is the other Big Kahuna that has experienced a major price hike. This revision sees the removal of subsidies for fertiliser manufacturers using gas from the SNGPL network, affecting 60% of the industry’s production capacity. The new policy raises the feedstock gas price from Rs580 per million British thermal units (mmbtu) to Rs1,597 per mmbtu, marking a significant increase in production costs for the affected manufacturers.

What does this mean? Well, the first thing to understand is that the fertiliser industry runs on subsidies from the government. The government provides the industry with cheap gas so they can produce cheaper fertiliser and the benefit is passed on to farmers. But this subsidy on Urea is often unproductive.

For example, since it is given through fertiliser manufacturers, large farmers and landowners end up getting more benefit from it than smaller farm owners that need it more simply because they can buy more.

There has long been advocacy that this subsidy should be restructured and possibly given directly to smaller farmers, and that fertiliser manufacturers should be given gas at the regular rates (WACOG as it is known in the industry) and they should be allowed to raise their prices. Smaller farmers would simply be given cards that would allow them to buy directly at subsidised rates.

That is why perhaps Engro was quick to express its happiness at the revision of gas prices even as other industrialists complained. In a press release issued by Engro Fertilisers, it is stated that ”Pakistan’s current financial position is distressed, it is in a debt crisis, with the debtto-GDP ratio already above 70 percent and more than $27 billion of foreign debt to be repaid by November 2024. The country cannot afford further fiscal pressures or half measures that do not go all the way in solving Pakistan’s problems. The dependence on government subsidies must end, for Pakistan to really move forward and break away from the vicious cycle of debt.” But there is a big problem here. You see, Pakistan’s fertiliser industry gets its gas from a couple of different sources. There is, of course, the SSGC. This is the natural gas that everyone gets and it is the price of this Sui gas that has been so increased. But then there is another source of gas for the fertiliser industry: Mari.

There are 10 fertiliser plants in Pakistan, and six of them receive dedicated supplies from Mari’s network. The six fertiliser plants on Mari network include three plants of Fauji Fertiliser Company (FFC), one old Engro fertilisers plant, one plant of Fatima Fertiliser, and the Pak-Arab Fertilisers Limited plant.

Essentially what this means is that Mari provides gas majorly to Fauji Fertiliser and in some small capacity to Fatima and Engro. The Mari gas is cheaper, and the government is yet to notify an increase in gas price for the six plants that are connected to Mari. This will unduly give Fauji Fertilisers a boost.

Engro Fertilisers has highlighted the partial nature of this policy change, noting that the remaining 40% of the sector’s capacity, which relies on gas from the Mari network, continues to benefit from the previous subsidised rate of Rs580 per mmbtu. The company argues that a complete removal of subsidies across the entire fertiliser sector is essential for the financial health and autonomy of the country. “With this complete removal, the government is expected to collect Rs 50 billion, which can then be used for targeted agricultural projects and initiatives that generate economic activity and growth in the country.” the company says further. n

Will the deregulation in drug pricing policy prove to be the long awaited cure for the pharmaceutical industry?

By Zain Naeem

There is a time and a place for government interference in private business. Even the most stringent advocates for the free market admit that there are scenarios in which the government should act as a regulator for industry. And in some cases, they even say it might be alright for the government to become a part of setting prices.

Take the pharmaceutical industry for example. If a private company invents a miracle drug that can solve a major health

epidemic, but they price it exorbitantly, is that when the government should step in? The involvement of the government in the free market is a delicate balance. The problem is that in Pakistan the government’s role is often that of a very incompetent micromanager.

Just look at the recent decision of the caretaker government to deregulate the prices of medicine for non-essential drugs. Up until this point, medicine prices in Pakistan had been strictly regulated. While this might seem like a good idea, it has often led to shortages on the supply end of the equation. The proposal of the caretaker government based on the recommendation made by the Ministry of

National Health allowed companies to adjust the prices of medicines which are deemed as being non-essential. This allows the pharmaceutical industry to set the prices which were regulated under the Drugs Act of 1976 and the Drug Pricing Policy of 2018.

Under the Drug Pricing Policy of 2018, the prices of pharmaceutical products could only be linked to the Consumer Price Index and companies had to give a 30 days’ notice to the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) which would lag the increase in prices. Just how monumental was this decision? Suffice to say, it was the much needed change that was being asked for by the pharmaceu-

24

tical sector. The drug companies were happy and it seemed a step (albeit a small one) in the direction of deregulation.

Despite the seemingly logical nature of this step, the deregulation has faced harsh criticism in the media. The matter became enough of an issue that the Lahore High Court stayed the deregulation from coming into effect on the 22nd of February 2024 seeking clarification from the Federal Government on why the deregulation was put into place.

The policies of the past saw many foreign investors and companies enter and leave the market seeing that their voice was not being heard. Even as recently as 2023, the government had to give a dispensation to manufacturers and importers to carry out a one time increase in their prices in order to make their business model sustainable.

The last two years have seen imports being curtailed, rupee devaluing, high levels of inflation and an across the board increase in cost of raw materials. This led to the companies facing severe pressure in terms of their margins and profits and some of this pressure had to be alleviated.

In normal circumstances, companies would have been allowed to change their prices in order to maintain their margins and profits but due to the regulations being in place, this option was not available. Now with deregulation being carried out, it can be expected that the companies will be able to have a say in their own pricing. So now the question arises, who will end up paying the cost of this change in policy? Profit debates the merits of the policies of the past and the impact of deregulation.

A history of regulation

The drug policies that were put into place in the past revolved around the fact that as the product being provided by the industry was in the interest of the people, the government should have an overarching control over the pricing based decisions. This meant that from the licensing to the manufacturing and pricing of the drugs, all aspects were heavily regulated and supervised by the government.

Drugs Act 1976

There have been three key regulations that have been promulgated categorized as the Drugs Act of 1976, the DRAP Act of 2012 and Drug Pricing Policy of 2018. The Drugs Act of 1976 was brought in under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the goal was to make sure that the medicines were affordable and maintained a quality standard. The Act specifically gave the government the

power to fix the maximum price that could be placed and mandated that a portion of the profits be put away for research by the company. In many aspects, this legislation is still applicable to the pharmaceutical industry.

One of the biggest drawbacks of this legislation was that no provision had been made in terms of developing a formula to be used by the government in setting the prices and the prices were fixed rather than have any allowance for inflation. The aftershocks of this policy were that there was a price freeze that was placed on the industry which meant many of them had to struggle to earn a profit as costs increased and margin diminished.

Due to this policy, there was an exodus that was seen in the last two decades where the number of multinational pharmaceutical companies in the country went from 48 to 22. As the companies had no control over their own prices, the rising production costs made operations unsustainable. Companies like Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol Myers Squibb, ICI, Roche Pakistan, Merck Group, Eli Lilly and Johnson & Johnson are some of the marquee companies which have divested their interest and left the country.

DRAP Act 2012

After the passing of the 18th Amendment, there was increasing pressure from the pharmaceutical industry to look into the regulation of the industry. This led to passing of the DRAP Act 2012 which allowed the establishment of DRAP which would oversee the industry in terms of licensing, approval and pricing. Even though the distribution and sales of the sector came under the purview of the provinces, DRAP still maintained control over many of the key aspects.

One of the functions of DRAP was to constitute a Drug Pricing Committee (DPC) which will formulate the drug pricing strategy and it was tasked with recommending a price which would be approved by the Federal Cabinet. One of the positive aspects of this committee was that there were representatives from the pharmaceutical industry and consumer rights on the board which meant that all stakeholders had representation in the pricing policy being proposed.

Drug Pricing Policy 2018

The last policy that has been made in regards to drug pricing is the Drug Pricing Policy of 2018. The policy looked to divide drugs as National Essential Medicines List and others. Under the new policy, DRAP sets the maximum retail price (MRP) for all drugs based on the

average price for the same drug in the region.

The policy also allowed manufacturers and importers to increase the price of their drug based on certain conditions. For essential drugs, prices could be raised up to 70% of the increase in CPI provided that it does not exceed 7% of the original price. For other drugs, firms could increase price by the amount equivalent to the change in CPI as long as it is not more than 10% of the original price. Regardless of the price increase, it had to be approved by DRAP before being implemented.

The policy is a nutshell

The recent example of Panadol shortage is the whole drug pricing policy in a nutshell. On 21st of October 2022, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare (GSKCH) announced that it would be suspending the manufacturing of Panadol which is a generic drug used for alleviation of pain and fever. This generic pill is used extensively for the cure of dengue as well.

Even before production had been shut down, the market had seen long periods of shortage as GSKCH had asked for the price of the drug to be increased only for their demands to be rejected. As the company was already seeing a rise in cost, they wanted to make sure they were not making a loss on a product. The company had asked DRAP and its Drug Pricing Committee to consider increasing the price as early as January of 2022 and this was rejected. Then in August, the company asked for an increase in its price in line with the change in CPI which it did but the increase was not equal to the cost of production which had increased by a greater amount.

In 2022, it was expected that the PTI-led government was going to allow the company to increase its price further but after the Vote of No Confidence, the increase was scrapped. The company has a capacity to produce more than 400 million tablets of the drug in a month but as its costs were increasing, they decided to cut their production by a third.

This coincided with the onset of dengue and massive floods in the country after the Monsoon season which led to an extraordinary spike in the consumption of the drug. As production had been cut, the market started to see shortages take place. In the face of the shortage crisis, the Federal Government stated that they would not look to increase prices and that there was abundant supply of Panadol in the market. There were whispers in the corridors of power that GSKCH was trying to blackmail the government to increase their prices.

The government even raided a warehouse in Sindh which was owned by Connect

PHARMACEUTICALS

which is a subsidiary of GSKCH tasked with distribution. The government was able to seize 48 million tablets and stated that the company was using hoarding tactics in order to reduce supply in the market. The company responded by saying that it was following standard operating procedures and it was holding 30 day safety stock at its warehouse.

The matter was solved on 26th of October after the company was allowed to increase its price to Rs 2.35 per tablet from Rs. 1.87 per tablet which is only half of the price hike that they had asked for. The company had originally asked for the price to be set at Rs. 2.67 per tablet.

This whole episode shows that companies have no option but to cut down their production when faced with rising prices. As the government has set the prices and does little to change them, the production halt leads to a shortage in the market. Rather than having to bear the burden of a small increase in price, patients are not able to have access to the drug and end up paying a higher price regardless as the drug is in short supply. This suffering is only alleviated once the company sees a hike in price and the supply goes back to normal.

Populism in policy

Like many of the policies that have been placed in the country, the drug pricing policy is also rooted in populism. Just like the country is reeling from the after effects of low priced energy being provided to the country in the form of circular debt, the pharmaceutical sector has also suffered based on the same rationale. Elected governments have tried to amend and change policies at different points of time in the past only to face backlash and then reverse its course.

The latest round of these changes saw public outcry over price increases taking place in January 2019 when prices had to be revised. When the price increase was announced, the government was attacked by the media and led to the ouster of the then Federal health minister for being complicit in the price increases. When the new minister, Dr Zafar Mirza, was appointed; he was tasked with reversing the prices within 72 hours.

Even in 2013, the Nawaz Sharif government faced the same reaction when it tried to increase prices as well. Any move to allow for prices to be left on the devices of the industry have been seen as detrimental to the health and wellbeing of the people. It is feared that allowing prices to be free would leave the people on the mercy of the manufacturers and importers.

Due to the vulnerability of the masses to such a move, it is seen as political suicide and government tries to make sure no such room is given to the industry. The deregulation law

has been passed by the caretaker setup and would have little to no political consequence, however, the reaction of the next government would show how the people have been impacted by such a move. Even when the merits of the deregulation are being debated, the Lahore High Court has already stepped in and stopped any implementation of this law.

Reaction of the industry

Many of the manufacturers have tried to circumvent the measures that are put into place by the government. Initially, when manufacturers start producing in such an environment, they set very high initial margins in terms of their prices as they are aware that over time, the government will put in controls which will chip away at these profits. This means that they are able to extract higher profits in the beginning and as the costs rise to the level of the prices, the company has been able to extract a large chunk of its profits.

Another ploy that is used in the industry is that as medicines become more expensive to manufacture, the company stops production of those drugs and starts using lower quality raw materials which leads to a considerable deterioration of the product. In the last few years, as inflation has risen to unprecedented levels and cost of manufacturing has increased as well, manufacturers have been left with little choice than to either stop manufacturing or demand an ease in price control.

The impact on people

It is evident that even though the policy is consumer oriented, the effects of the policy have been mixed to say the least.

Yes, people do benefit when prices are controlled and monitored by the government but there is little assurity that the drugs people are getting will be of high quality and that the company will keep manufacturing them even when the cost of production keeps getting higher.

In a speech made by the caretaker Prime Minister Kakar admitted that hoarding and smuggling of drugs was being carried out and people were paying three to five times for drugs which were not available in the country. As the manufacturers have to make a choice between manufacturing at a loss or not manufacturing at all, they choose not to do so which creates a shortage of drugs in the country. With life saving drugs being in short supply, people have no option but to turn towards smuggled drugs at a higher price.

The impact of the price controls falls solely on the consumers who either have to turn towards a lower quality product or no

medicine at all and have to suffer worse health effects. Patients can see complications in their medical conditions or longer treatment times due to the lack of potency of the medicines in the first place.

Will it be free for all?

Now that the prices are being deregulated, will it mean that the drug prices will be expected to skyrocket? Will the examples of the United States be seen in the country where medicine prices are allowed to be whatever the manufacturer wants them to be? Will there be a Martin Shkreli school of thought prevailing?

Well not exactly. It does not need to be one extreme or the other. The country cannot go from all controls to no controls at all. There needs to be a balance that needs to be put into place. The goal of any drug policy has to be three pronged. First of all, drugs need to be priced at affordable rates based on the fact that patients are able to get them. Secondly, drugs have to maintain a certain standard and lastly the drugs need to be available all across the country.

The policy that was being followed before meant that even though prices were guaranteed, there was no assurity that drugs would be readily available and that they would be of good quality. With deregulation for prices, it can be expected that DRAP can now make sure all three aspects of a good policy are maintained.

If tomorrow Panadol is being sold for Rs.100 a tablet rather than Rs. 3 per tablet, DRAP can send a notice to GlaxoSmithKline Pakistan asking them for a rationale for the sudden price increase. This will make sure that the price increase is justified and if the company is trying to game the price, they can be penalized and punished. Similarly, now that the price is under the purview of the company, DRAP can mandate that the quality of the product is maintained and that there is ample supply of the drug all over the country.

This way DRAP can make sure that the drug is available in the market at a low price and the company is maintaining quality. In case a price increase does take place, the burden will fall on the company to prove that the price hike is justified. The new policy will also incentivize the companies to continue production and to maintain a high quality product as they can rationalize it with a price hike and they will have a profit motive to pursue while serving its patients. The sense of populism needs to be eradicated from the drug pricing policy and DRAP needs to be mandated to look out for customer interest while allowing drug manufacturers to have control over their own prices. n

26 PHARMACEUTICALS

By Mariam Umar

By Mariam Umar

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab

Source: Tabadlab