09 The battle for TRG is raging. Will Zia Chishti get his way again?

12 Can the miracle called SIUT be replicated?

18 Naveed Anwar – Our man at Citi 21

21 How soaring prices, low agri demand, and import constraints set OMC sales back by three years

22 Will Bank of Punjab’s lucrative rates be enough to attract dollars back into the banking system? 25

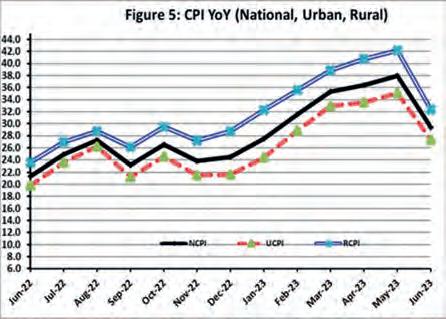

25 In rural Pakistan, the inflation problem is even worse

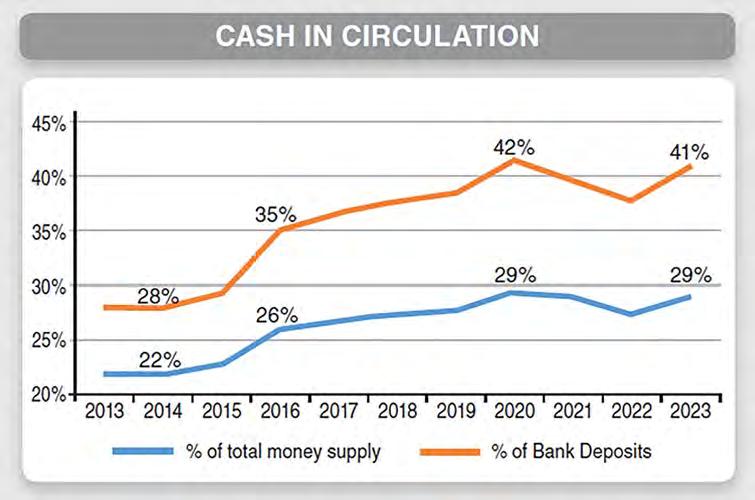

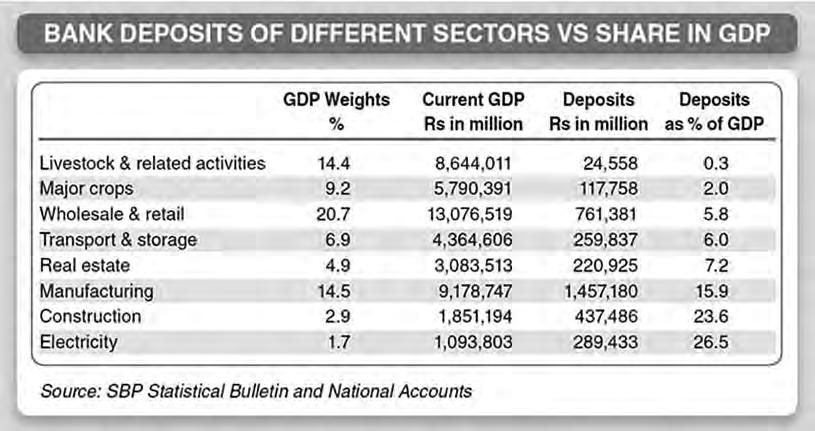

27 Transitioning away from a cash economy

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Sohail Abbas (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Nearly two years after its founder and CEO fell from grace following allegations of sexual assault and misconduct, one of the most traded companies on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) in the midst of an all out war.

The saga to wrestle control of The Resource Group (TRG) has reached the grappling on the floor stage with the company’s former CEO Zia Chishti issuing full page advertisements in newspapers targeting the company’s incumbent directorate and pleading with minority shareholders to pressure them to call an Extraordinary General Meeting (EOGM).

What does Chishti hope to achieve with these tactics? As the largest single shareholder in TRG Pakistan it seems he wants back in at the helm of the company and is rearing for a hostile takeover. As of now the company’s board of directors are managing to hold back

the onslaught. But armed with the largest individualistic stake in TRG Pakistan and the support of other shareholders, will Chishti be able to wrest back control? For now the matter has gone to the Sindh High Court (SHC) which has put an end to any immediate EOGM being called. But how did matters get to this point for TRG?

In the summer of 2021, things could not look better for TRG Pakistan. Its shares were some of the most traded on the PSX and as a company TRG was going from strength to strength having just announced a dividend of 44% or Rs. 4.4 in the third quarter of FY 2020-2021. The dividend was followed by the company showing earnings of Rs. 47.4 per share for the year and then gave out another sizable dividend of Rs. 4.4 per share in the first quarter of FY 2021-2022.

Talk to any leading investment company

or brokerage house in the country and they would tell you that TRG was a great investment specifically in the technology sector as it was expanding and growing at a rapid rate. The man behind this success was Zia Chishti. Born to an white, American convert mother and a Pakistani father, Chishti started his career as an investment banker he went on to invent Invisalign braces and founded the company Afiniti. Initially a call-center operator, Afiniti started to identify itself as an AI pioneer, saying its software could supercharge the efficiency of call centers by matching customers with agents most likely to solve their problem or make a sale around 2017. On the back of this pitch and at a time when technology companies were getting the lion’s share of new investment, it seemed nothing could stop Afiniti.

Due to his Pakistani origins, Chishti kept some of his investments in his father’s home country. Afiniti is partly owned by TRG (The Resource Group) Pakistan, which was created in 2002 specifically to act as the global holding

With newspaper ads and angry shareholders abound, a hostile takeover could be on the horizon

company for all of TRG’s investments. It was listed on the then Karachi Stock Exchange in July 2003. TRG was the original company that Chishti had founded out of which Afiniti had grown.

The ownership structure of TRG is highly complex and consists of several layers of holding companies. TRG Pakistan is the overall holding company, but it does not own the entirety of TRG International, which in turn does not necessarily own the entirety of the shares in its portfolio companies. At each stage, there are minority investors who own significant stakes, which makes it difficult to track exactly how much the overall portfolio is worth, and how much of it is owned by the shareholders of the publicly listed company on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

What we do know is that Chishti is the majority shareholder in TRG Pakistan and as an umbrella holding company for TRG’s investments TRG Pakistan is important for Chishti to control his empire.

For most of its existence, TRG Pakistan’s subsidiary was TRG International, which is a British Virgin Islands-incorporated holding company that in turn owns stakes in most of TRG’s portfolio companies. However, in June 2020, TRG Pakistan’s share in TRG International changed from 57.16% to 46.03%. It is no longer a subsidiary, but is instead, technically, an affiliated company. And while this means that control of TRG Pakistan does not mean control of the international company, it does give Chishti (who also has shares in the other affiliated companies) significant sway over these investments,

Because of all this Chishti was flying high in Pakistan. He was honoured with government awards and was jetting to and from Pakistan. His company was highly respected and he was a star for Pakistani investors. Until he wasn’t.

It is no secret why Chishti was ousted from Afiniti and then TRG as well. In November 2021, Chishti was accused of sexual assault by a former employee during a congressional hearing in the United States. The house of cards started tumbling almost immediately. Chishti stepped down as the CEO of Afiniti in the United States on the 19th of November and as CEO of TRG Pakistan soon after. He immediately came to Pakistan where an EOGM was called for TRG Pakistan. Despite his best lobbying attempts, Chishti was unceremoniously booted from the company’s board of directors on the 11th of January 2022 bringing an end to his control on his own investments.

By this point it seemed clear that Chishti was out and he would go into relative obscu-

rity. But he did not take the ouster kindly. Events since his ouster from the board of directors of TRG Pakistan show that Chishti is still looking to get his company back and is willing to be hostile to do so.

Essentially what we have now is an attempt at a hostile takeover, and it isn’t the first time TRG Pakistan has faced one. In fact, it was Chishti who had tried to engineer one back in October 2022 in what was his first attempt at regaining control of his companies. The October putsch was in conjunction with the JS Group which has significant shareholding in TRG Pakistan.

As a result, a petition was filed by the company in the Sindh High Court in October of 2022 which stated that Chishti, in cooperation with Jahangir Siddiqui & Company Limited with 12 other individuals, was looking to acquire shares of the company in order to take over the board of directors.

In order to take over the company, the lawsuit alleged that the JS Group was working with its partners to take over TRG Pakistan. According to laws, a group of investors can join together and buy shares of any company that they want. Associate companies, companies who have close ties to the listed company, need to disclose when they buy even a single share. JS Corporation Limited is an associate company for TRG Pakistan

Once the acquiring company buys more than 30% of shares of a company, they need to make a public offer to the market.

The public offer brings to light the fact that the acquiring company, in this case JS Group, should have made a public offer to acquire more shares which would have to be announced to the whole market. The lawsuit stated that the whole group had acquired 34% of the shares, crossing the 30% threshold, and had not made a public offer. They had acquired the shares in a surreptitious manner and had not disclosed it.

Once the lawsuit was filed, the Sindh High Court restrained the JS Group from exercising any voting control in excess of the 30% they had acquired unlawfully. The lawsuit alleged that Chishti and his group were finding ways of taking over the company by circumventing the laws and were also involved in disrupting the affairs of the company by launching social media based campaigns and filing complaints to the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP).

The crux of the matter lies in the fact that TRG Pakistan accused the “Chishti Group” of holding more than 34 percent shares of the company while not making a public offer or proper disclosures as they are required to. It stated that JS Group owned 13.8 percent,

Chishti with his wife owned 19.7 percent while DGM Securities and Al Habib Capital Markets, brokers for Chishti’s wife, held 0.8 percent collectively.

After this move was thwarted, another move was made in January 2023. Court filings again show how an attempt of a hostile takeover was thwarted. The company disclosed to the PSX that the Sindh High Court had passed an interim order on 7th January 2023 to restrain the same parties from creating a third party interest by using the shares of Chishti and his wife. Campaigns against the company itself.

Chishti has not been sitting meekly in this entire time. And while his attempts to regain TRG Pakistan have been somehow thwarted up until now, he has had the company’s current management under fire.

TRG has had to take out notices at regular intervals denying any social media campaign that is being run against the directors of the company. In order to ramp up the pressure, Zia Chishti filed a defamation suit against the company which led to bailable arrest warrants being issued for the directors of the company. The directors got the warrants suspended in February 2023.

The defamation suit that was filed has also been suspended with a stay order passed by the Sindh High Court on 20th of March 2023.

The battle for the company is not only being fought against Chishti but also from within the company itself. One of the directors, Mr. Asad Nasir, has filed complaints against the company to the SECP based on the matters that were voted in December 2021 prior to the elections being held after Chishti’s ouster.

The company came into focus again when an ad was taken out in the leading publications of the country. The ad goes into detail to make a case regarding the malpractices of its directors and how they are destroying the company from the inside.

Accessing the links given in the ad showed that there was no such website and there is no name or contact information in the ad itself. The site being referenced has come online much later with a group being made on Facebook. We now know, based on a court order filed by TRG Pakistan, that the ads were an attempt by Chishti to unite the shareholders and ask for an EOGM to be called.

The ad that has been published accuses the current CEO and a director at the company with two other directors of destroying the value of the company

while they pursue their own interest. It alleges that Mr. Hasnain Aslam, the current CEO of the company, is concealing his sexual harassment at Afiniti which is one of the companies TRG Pakistan has a stake in. The ad goes on to say that Mr. Aslam with Mr. Mohammad Khaishgi and Mr. John Leone, two other directors, have little stake in the company and have taken “illegal” control over the company’s affairs.

The ad is targeted at the shareholders who are being made aware that the company has been damaged due to operational mismanagement and that Afiniti, considered the crown jewel for TRG Pakistan, has actually seen a collapse in its revenue and equity value. Ibex, a subsidiary of the company has seen its share price crash by 50% from its peak while the company is using its cash reserves to buy its own shares using an opaque subsidiary of TRG International called Greentree Holdings Limited to allow these directors to maintain their position. Under the leadership, the revenues of the company have halved, even though the dollar has increased in value which should have been beneficial for the company. TRG Pakistan repatriates the income earned from foreign sources from dollars which should have seen an increase as the rupee depreciated.

The ad also takes aim at the other shareholders who are allowing these directors to stay in their position while the company is suffering due to mismanagement.

It has been claimed that on September 25th 2023, Mr. Zia Chishti, the largest shareholder of the company, looked to remove all the members on the board of directors and amend the Articles of Association in order to improve the governance at the company. The ad is phrased from the point of view of the shareholders of the company who are demanding for an extraordinary general meeting to be held to vote on the matter in relation to the board of directors. The ad ends with the request to join the effort in order to save the company and to share proxy votes in order to vote the present directors out.

The letter ends with making a case for holding of an EOGM by the company itself and a special agenda item can be added which would allow the directors to be retired and new directors to be elected. The goal of the meeting would be to take control away from the directors currently running the company and bring in better directors who can take the company back to its past glory.

Specific allegations being made against the directors state that the directors did not bring back $120 million in cash and $70 million in securities into Pakistan as dividends and used them to park this money into Greentree Holdings Limited which is not controlled by TRGP.

Additionally, it alleges that TRGP’s voting interest in TRGI has been decreased to 45.3% even though it has an economic interest of 68.8% in the company which is not being disclosed to the shareholders. The company has given away some of its control over the board of TRGI which takes away some majority control that TRGP has over TRGI. The matter of $190 million worth of dividend was left parked at GreenTree Holdings Limited without the approval of shareholders of TRGP. Lastly, it alleges that the company withheld information of any litigation that was filed against which should be known to the shareholders.

The solution to these issues that has been given in the letter is to call an EOGM and to relieve the current directors from their posts. It claims that the current board of directors is not able to manage the situation and is allowing the three directors to mainly run the company on their behalf. While the directors need to be removed, it is also stated that articles of association need to be changed to bring the corporate governance framework of the company in compliance to Companies Act 2017. The company has not done so and follows the provisions of Companies Ordinance 1984 which has been repealed.

In response to all of this, TRG has tried to once again put out strong statements against the possibilities of Chishti regaining control of the company. On the 4th of October, the company said in a statement that “any association with Zia Chishti would be highly damaging to the value of the company’s underlying assets, and it is engaged in multiple lawsuits involving unlawful attempts by the ex-CEO to regain control of the company.”

“This is with respect to newspaper advertisements published by Muhammad Ziaullah Khan Chishti attempting to requisition an extraordinary general meeting of TRG Pakistan Limited, with the agenda involving the removal of 9 out of 10 directors of the Company, as well seeking amendments to the Articles of Association of the company,” read the notice to the bourse.

According to laws of Pakistan, a limited company registered with the SECP has to carry out an Annual General Meeting (AGM) on a yearly basis. The purpose of this meeting is to vote on certain issues and agenda items. Usually, these meetings deal with issues like appointing an auditor for the next year, pass the minutes of any pending AGM and to hash out other pending issues. As a shareholder, investors

have an opportunity to put different items on the agenda which can, in their view, benefit the company.

Zia Chishti, as a substantial shareholder, tried to add an addendum to the AGM by looking to make M/s. Grant Thornton Anjum Rahman, Chartered Accountants, the new auditors and the Central Depository Company (CDC) the share registrar for the company. This addendum was filed on 18th October 2022 for a meeting that was announced for 25th of October.

At this point of time, a letter had been attached from M/s. Grant Thornton Anjum Rahman themselves which showed that they were interested in being appointed as auditors. It seems like Mr Chishti had gotten his way. The company was mandated to hold the AGM and had to put these agenda items to be passed or rejected at the AGM. The company outwitted Chishti by filing a request at the Sindh High Court to adjourn the meeting from being held. The Court agreed with the company and restrained the company from holding the AGM till any future notices or orders were issued. On 26th October, M/s. Grant Thornton Anjum Rahman also withdrew its consent to be the auditors for the company.

As TRG Pakistan is a listed company, one of the main battlefields that has been used by the two sides is that they have looked to accumulate shares of the company in different forms. Chishti group has looked to acquire the shares of the companies by using the JS Group and his wife’s accounts to accumulate shares. This has been thwarted at different stages by the Sindh High Court due to petitions filed by the company itself. On the other hand, TRG Pakistan is using Greentree Holdings Limited. As of June 30 2021, the company did not hold even 1 share of the company. Fast forward to June end 2023 and it holds nearly 156 million or 28.54 percent of the total shares of the company.

The shareholding is a very important aspect of this battle as both sides know that holding the shares gives them power to vote on the board of directors and the general direction the company is going in. TRG Pakistan knows that an attempt was made in the earlier elections held in 2022 where Chishti wanted to be elected to the board of directors. At that time, due to the damage done to his reputation, the move might have been criticised. Now Chishti feels that he needs to get a hold of greater shareholding in the company to make an impact. Directors in Pakistan are elected for three years. The next election will be held in 2025 and it seems that this tussle will continue till then. Only time will tell what happens until then. But for now Chishti is unrelenting and the TRG management is barely holding him at bay. n

In a country where the illegal kidney trade is rampant, SIUT offers a glimmer of hope. Can anything close to it ever be done again?

It was a big week for urology in Pakistan but in a decidedly bittersweet manner. On the one hand there was the news that the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT) was interested in buying the Regent Plaza — a sprawling five star hotel near the Jinnah International Hotel in Karachi. The proposed acquisition of the hotel could be worth nearly Rs 4 billion, indicating the success that the SIUT has had not just as a dedicated, philanthropic, patient care facility but also as a financially savvy charitable organisation.

In a country with abysmal medical outcomes and crumbling healthcare infrastructure, SIUT is a miracle. But the dizzying high of its sustained success was short-lived with the news that the government of Punjab had busted a gang trafficking kidneys to wealthy foreign clients. The initial police reports suggest that the gang was led by a single doctor, Fawad Mumtaz, who, assisted by a car mechanic as an anesthesiologist, has admitted to conducting 328 illegal kidney transplants in Pakistan.

What makes the situation worse is that this is the sixth time Mumtaz has been arrested. His practice as Punjab’s top-most illegal kidney operation doctor has been well-documented since at least 2009. Every time his arrest has been followed by release thanks to the many political and bureaucratic connections he has made over these years through his lucrative business.

The kidney trade has plagued Pakistan for many years now. In fact, up until at least 2017, Pakistan was perhaps the largest hub of illegal kidney transplants in the world. Within the country Punjab was the hotspot for such procedures. One of the reasons for this has in fact been that the presence of SIUT in Sindh has seen a significant decline in kidneys for sale.

The question is, can SIUT be copied elsewhere in the country? As a charitable organisation the institute has provided care and treatment to countless people and has become a standard bearer in the healthcare industry. But how much of this success is practically replicable, particularly in a country whose healthcare system is struggling with problems as basic as illegal kidney transplants? Profit investigates.

The story of SIUT is synonymous with the life of Dr Adib Rizvi. Nine years old at the time of partition, Dr Rizvi moved to Karachi with his family from Jaipur. This is where he got his initial education. As part of the first generation

of Pakistanis, Dr Rizvi was one of the many young doctors, lawyers, civil servants, soldiers, farmers, businessmen, and political leaders that were native to Pakistan. Their efforts were to determine the course the fledgling nation would inevitably chart.

As a medical student in the late 1950s at Dow Medical College in Karachi, Rizvi’s batch was one of the first in the country to be trained in the use of penicillin. Clearly this was a time of great change for medicine and with the expansion of medical philosophy opportunities in medicine were opening up. Many Pakistani doctors were going to the United Kingdom in particular to pursue services in the National Health Service (NHS).

This is the route that Dr Rizvi took after graduating in 1961. At the UK’s NHS, he undertook a fellowship in surgery for much of the decade. This is where he developed his early vision for what healthcare, in particular public healthcare, should look like. As a taxpayer funded healthcare system the NHS has often served as a n example of what government

that year’s devastating floods. Soon Naqvi had joined Rizvi at Karachi’s Civil Hospital and the two began curating an established team that continues to work with him. Over the next five decades Pakistan’s population grew from 70 million to 185 million, the country underwent two military coups, two massive earthquakes, the war on terror, and then finally the country’s first democratic transfer of power. Negligence in healthcare remained constant through all of this.

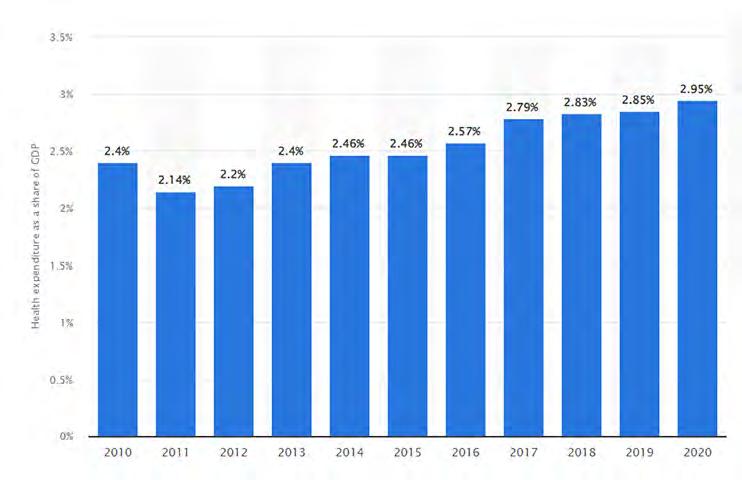

Government spending on healthcare currently is dangerously low, and between 2010-2023 has hovered between 2.4% to 2.9% of the country’s gross domestic product. This is far less than what is required in a country facing the kind of problems Pakistan is facing. These include, in no particular order, some of the highest rates of maternal, foetal, and child mortality in the world; a shortfall of around 200 000 healthcare workers; and the stubborn persistence of polio (only Pakistan and Afghanistan remain endemic for the disease).

provided healthcare facilities should look like. Which is why when Dr Rizvi returned to Pakistan at the end of his fellowship in 1970, he gravitated towards the public sector. “I began to think that healthcare should be the basic right of every human being—a birthright, like education,” he was quoted by the British Medical Journal as saying.

In 1971 Rizvi, by then an assistant professor of urology, took over the eight bed genitourinary ward at Karachi’s Civil Hospital. At the time the government was spending around 0.7% of the country’s gross domestic product on healthcare. In 1973, Dr Rizvi met Anwar Naqvi. Both were serving at a medical relief camp set up for victims of

More specifically speaking, this means that 46 babies died before the end of their first month for every 1000 babies born in Pakistan making it the most risky country for newborns, ahead of even sub Saharan African countries and Afghanistan.

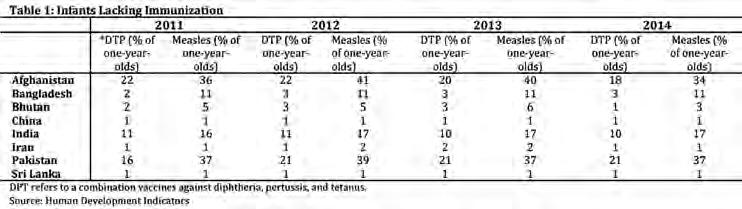

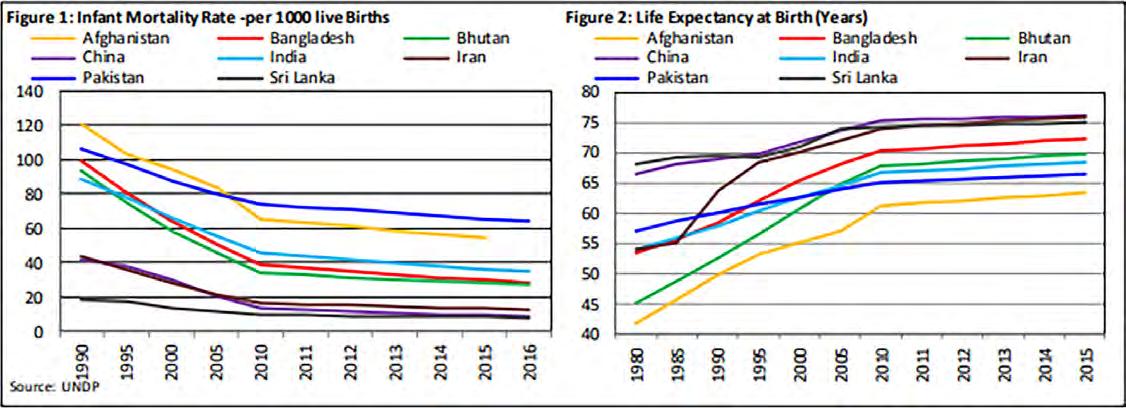

In reference to Immunization Indicators, Pakistan is being recognized as one of the few remaining countries with widespread polio. In terms of Infants Lacking Immunisation, the status of Pakistan is quite alarming given the effects of infectious diseases on economic growth in literature. Number of infants lacking basic immunisation is not only far below than other regional countries but also deteriorated over the years

According to a more recent report by the journal Scientific Report, 44% of children less than five years in Pakistan were found stunted. Close to 31% were found underweight and 15% were found wasted. In addition, according to the National Nutrition Survey (2018) of Pakistan, 40% of children under five years of age were found stunted, 17.7% were wasted and nearly one-third of children were reported underweight (28.9%).

The earlier mentioned report of the SBP points out that the unsatisfactory performance for most of the targets may be attributed to suboptimal allocation of budget by government to health sector, internal and external economic and non-economic challenges. As a result of these terrible health statistics, Pakistanis are more susceptible to disease than the citizens of other countries. On the urology front alone, according to a report of the British Medical Journal, around 25 000 Pakistanis have renal failure every year. About 10% of these patients can obtain dialysis, a session of which costs $20-25 in the private sector, and less than 5% can obtain a kidney transplant, the cost of which ranges from $6000-10 000. Specialists are in short supply. Pakistan has no more than a few dozen nephrologists and even fewer transplant surgeons.

It was with these constraints that Dr Rizvi launched his mission. His argument was that the government was severely exhausted and unable to cope with a country the size of Pakistan. Remember, this was also well before

2008 so Pakistan’s ‘democracy’ was far from developed and devolution was a distant concept. From his experience in the UK Dr Rizvi argued that healthcare should be a partnership between the public and the government.

“We have to create a partnership between the community and the government,” he explained. The Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, which grew out of the eight bed ward, is such a partnership.

The SIUT was born as an eight-bed surgery ward in Karachi’s Civil Hospital in 1972. The confidence of the administration and the people that Dr Adib Rizvi won by his zeal for the methodical care of indigent patients facilitated the small unit’s recognition as the Department of Urology and Transplantation in 1986. Five years later, it became an autonomous institution under a Sindh act and became functional as the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT) in 1992.

This was perhaps one of the biggest decisions that Rizvi could have made in regards to what direction SIUT would take. As the leading light of the institution Dr Rizvi was also the person interacting with most donors and his credibility was a huge pull when it came to the hospital’s funding. But instead of opting to create a private charitable hospital, he sought to develop instead a government health facility’s capacity for delivering up-to-date medical care to the people, especially the poorest among them, without any cost to them and without compromising their dignity. In the

words of the late I A Rehman, “this approach reinforced the principle of the state’s obligation to respect the citizens’ right to health. At the same time, it demonstrated a public health facility’s capacity to deliver if it had the right people to run it and if political authority was not blind altogether.”

The institute now takes care of nearly a million patients per year, and specialises in providing emergency services, major and minor surgical procedures, lithotripsy and dialysis sessions, transplants, radiology tests and laboratory investigations by extraordinarily skilled professionals. Since 1985 surgeons at SIUT have performed almost 5000 kidney transplants, including Pakistan’s first cadaveric and paediatric transplants. The institute has treated around 10 million patients since its inception. Several satellite branches are dotted around Sindh. There are also advanced plans for a dedicated paediatric urology, nephrology, and cardiology unit that will be named after Philip Ransley, a paediatric urologist from Great Ormond Street Hospital who has often visited the institute to teach and perform complex reconstructive surgeries.

Now all of this is well and good. The SUIT is an incredible organisation with an inspiring story that should be emulated in other regions of the country. The only problem is where will the money come from and who will lead the efforts?

A glance at some of the largest healthcare related charities in Pakistan will reveal that each has a dynamic, dedicated, and charismatic leader. For decades Abdul Sattar Edhi along with his wife Bilquis Edhi ran the Edhi foundation — one of the largest ambulance networks in the world. Part of the reliability of the foundation was Edhi’s own spartan way of life and rejection of luxury. His personal

honesty made him trustworthy and thus the darling of not just large but more particularly small, everyday donors. Similarly, Imran Khan played and won a world cup on the back of the dream of building Shaukat Khanum. In what proved to be his second innings in life Khan successfully fundraised and made the hospital a reality with two more chapters in Karachi and Peshawar. While his fundraising with the general public was less successful than Edhi but his big personality made him a popular figure amongst the elite where he gained some of his bigger donations.

In both cases there is a solitary leader that embodies the organisation. Dr Adib Rizvi and SIUT fall somewhere in between these two philosophies of philanthropy. While he is a well known figure, particularly in recent years with his distinctive white hair and heavy-set glasses, he is by no means a celebrity in the same way that Abdul Sattar Edhi was or Imran Khan is. One can neither imagine Dr Rizvi lifting a world cup trophy nor being the subject of an iconic photograph sitting in a white Suzuki Bolan the way Edhi was. Instead, Dr Rizbi relies on a mix of popular support for SIUT and big donor funding particularly from overseas Pakistanis. He is also media shy, and upon Profit’s inquiry for an interview, this correspondent was very politely told that the good doctor does not give interviews but all of his views and statements were readily available on the internet and shared promptly by his team. He is by all accounts a figure more suited to medicine rather than fundraising but has had to become good at the latter.

So where is the money coming from exactly? For starters the organisation is a public hospital. SIUT’s 750 bed facility in Karachi is provided by the government of Sindh and as such the hospital has many of its operational costs subsidised. In this way the SIUT receives around half of its funding from the government. This in itself solves a major problem which is a glittering example not just for Pakistan but all of South Asia. It is difficult to speak of surgery in this region of the world with any great pride. The rate of surgery, meaning how many patients get operated upon, in rural Pakistan is 124 out of every one lakh patients according to a different study of the British Medical Journal. In comparison, the rate of surgery in rural towns in the United States is 8345 patients out of one lakh. The same study, which is from 2004 and is somehow still the latest data available on this, points out how even back then “SIUT in Karachi is an example that can be emulated. It conducts 110 renal surgeries a year with internationally comparable results.”

While the government of Sindh does contribute in this way to the funding of SIUT, much of its donations come from either the general public or SIUT North America — a charitable organisation formed in the United

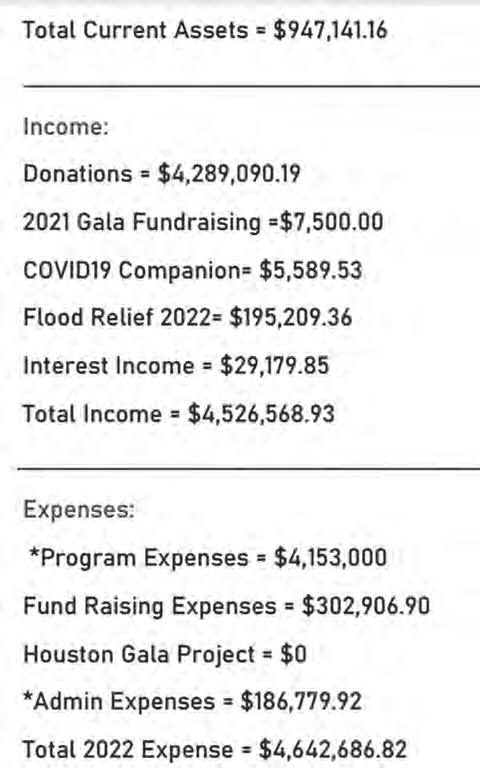

States in the year 2000 meant to be the main donor for SIUT in Pakistan. Most large donors send their donations to SIUT through SIUT North America. A look at SIUT North America’s annual report for 2022 shows that in 2022 alone they raised over $4.5 million for SIUT Karachi through campaigns for Sadqah, Zakat, Flood relief, and Covid-19 relief. And these were just the cash donations. SIUT has prided itself on maintaining the latest technology in its facilities. Since 2019, SIUT North America has donated equipment and technology to the tune of $15 million.

“Medicine is dynamic, and technology is changing rapidly; to survive as an institution, you have to keep pace with new modalities and breakthroughs,” said Dr Rizvi in an earlier statement. “We started with urology, we added nephrology, transplantation, radiology, an oncology department, and a bioethics unit— we continue investing. This model can very well be replicated. There are really only three conditions. You have to be committed because the facility must run day and night; every effort should be made to be on the cutting edge of technology; and you should be transparent and accountable to the government and the community at large”.

What is perhaps the most impressive in this is that SIUT spends most of the money it makes on patient care and a significantly smaller portion on administrative expenses. Of the $4.5 million raised in 2022, SIUT spent $4.15 million on program expenses. Only $187,000 were spent on administrative expenses. Of these expenses too, salaries and wages only accounted for around $131,473. This, of course, is the data available for the publicly listed SIUT North America and not the doctors, nurses, healthcare workers and administrators working at SIUT in Pakistan. The data for this is not publicly disclosed but a similar philosophy reigns.

This is what it all boils down to. What we started with. SIUT is clearly an organisation that commands respect and demands replication. But why on earth are they buying a hotel? As we’ve clearly seen the organisation very much has the fundraising capacity to be able to afford the hospital. According to a recent report in Dawn, at the going market rate of Rs 220.04 per share, a 100 per cent

acquisition of the hotel business should be worth Rs 3.96 billion.

As a business the Regent Plaza is relatively stable. A lot of hotel businesses were terribly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic and many have either gone under. Some of the older hotels in particular could not sustain the losses of that period because they were already in a state of disrepair. The Regent Plaza on the other hand actually made a profit for the year 2023 of more than Rs 4.4 crore according to their annual financial statement. This was, however, down from 2022 when the hotel made a profit of Rs 4.7 crore.

Now, what many people do not understand is that philanthropic companies are not a simple equation of donated money going to a simple end cause. For example if you donate money to a hospital it is not necessary that the money is spent directly on the care of a patient. In fact it is entirely likely that it could be spent to buy a new photocopy machine that the hospital desperately needs as an administrative expense. That is why a lot of donations either come to particular fundraisers (like for a new piece of equipment or a new ward) or are made out to specific causes within a charitable organisation. Similarly, a charitable organisation can also run a business on the side for profit. The profits then get funnelled back into the

original charitable cause.

Now, SIUT could very well be doing this if they acquire the Regent Plaza. But what is more likely, and what they claim is the case, is that they wish to convert the building into a hospital. The apparent reason for the possible acquisition of the hotel by the SIUT Trust is its prime real estate with a built-up structure that can easily be converted into a hospital with only a few architectural tweaks. Regent Plaza Hotel and Convention Centre is located on main Shahrah-e-Faisal on an area of 13,200 square yards. The total covered area of the multi-storey building is 47,034 square yards.

The plaza is owned by a publicly listed company by the name of Pakistan Hotels Developers Ltd (PHDL). This company is what SIUT would be acquiring. Now the PHDL also possesses two other pieces of real estate with a collective area of about 14 acres located in Thatta. The latest annual accounts show the company has valued its main real estate at Rs 8.9 billion. Its hotel building is valued at Rs 93.9 crores.

So on the one side we have SIUT. It has been run for nearly half a century by a doctor that is perhaps one of Pakistan’s most legendary. It has treated millions of people free of cost and has given a model of not just how a good charitable organisation can work, but how healthcare can be provided on a government level. How patients can be

treated as deserving of care rather than being blessed to receive it.

But unfortunately its example is singular. Attempts have been made to provide similar facilities. The Pakistan Kidney and Liver Institute (PKLI) is one attempt to emulate something similar but it too fell to politicking and bureaucracy. In 2018, the Supreme Court actually appointed a former judge of the SC, Justice Hameed ur Rehman, to run PKLI. He was to be assisted by a committee that consisted of a former health secretary, a member of Nepra, a retired three-star general, and exactly one doctor. In 2019, when a professional doctor was finally appointed as director of the institute, he was also dismissed and eventually placed on the ECL when the government changed.

On the other hand doctors such as Fawad Mumtaz are able to run massive and lucrative businesses with the help of political patronage. A recent report in Dawn said that the notorious surgeon has become a ‘test case’ for the criminal justice system and the law enforcement agencies, especially for the Punjab police.

“Mumtaz has been booked and arrested several times by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) and the Pu¬¬¬n¬jab police, but each time, he has managed to obtain bail and continue his illegal transplant racket. According to his criminal record, Mumtaz has been running the largest-ever illegal kidney transplant racket across the country, especially in Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Azad Jammu and Kashmir since 2009.”

The kidney trade in Pakistan is in fact rampant. A detailed investigation conducted

by Reuters Thomson Foundation in 2017 reported that kidneys were being sold in Pakistan at a rate of sometimes just $1,000. There is no official data on the number of people who have sold their kidneys in Pakistan, but some officials estimate that there could be at least 1,000 victims every year. It is mostly foreign clients coming to the country for transplants. People selling these kidneys get a few lakhs out of this and risk their lives at worst and leave with life long complications at worst.

Even now, the latest arrest of Fawad Mumtaz came after a Jordanian woman died during one such illegal operation for a kidney. The biggest hub of this business in Pakistan is still Punjab. Why has it not caught on as much in Sindh in particular? According to the British Medical Journal, Dr Rizvi’s advocacy was instrumental in the practice being criminalised. The Sindh Institute is focused on renal disorders—60% of surgical interventions at the institute are for kidney stones—but it also offers services for those with gastrointestinal or liver complaints (it was the site of Pakistan’s first liver transplant).

This is the sort of impact a good, dedicated, government facility can have not just on people’s lives but on the larger state of things. SIUT has not just been a beacon in terms of healthcare but has proven to be a bastion for human rights and the basic dignity of life. With the state of brain drain in the country, such replications are unlikely. But one can only hope that SIUT continues to thrive and many more titans such as Dr Rizvi are around to raise walls in which lives are saved. n

There is a special place in every Pakistani banker’s heart for Citibank. Despite not being the biggest foreign bank in Pakistan by any estimation bank has had a disproportionate impact on financial leadership in the country. In both Corporate Pakistan – as well as the government – it means something special to be able to call oneself an “ex-Citibanker”, more so than any other financial institution.

The bank’s alumni in Pakistan include two former federal finance ministers – Shaukat Aziz and Shaukat Tarin – one of whom (Aziz) went on to become Prime Minister. They also include two provincial finance ministers – Murad Ali Shah of Sindh and Hashim Jawan Bakht of Punjab – one of whom (Shah) went on to become provincial chief minister.

That, of course, is the place of Citibankers within Pakistan. Now imagine a Pakistani that is not just a Citibanker but is one of the institute’s leaders on a global scale. That is the unique place that Naveed Anwar holds. Born and raised in Lahore, Anwar is currently the driving force behind Citibank’s global digital strategy in a tech world where Pakistani talent is sparse.

How did this happen? Anwar’s career trajectory is a compelling story of transition and adaptation. His career started in the tech hub of Silicon Valley, with his formative experiences in major tech companies like Netscape and AOL, which provided the essential building blocks for his subsequent move into the fintech sector at PayPal. Subsequently, he challenged himself by venturing into the banking sector, starting with Capital One and eventually landing at Citi - a global bank with a presence in more than 90 countries where he works as the managing director, global head of digital and data platforms in the treasury and trade solutions division.

It all began in 1993. A younger Anwar had just completed his Fsc from FC College in Lahore, and was now faced with a monumental decision: join the Pakistan army or venture abroad to the United States for studies. The allure of the U.S. beckoned, leading him to the University of Wichita, Kansas, where he initially pursued industrial engineering. But an electrical engineering class caught his attention, shifting his academic trajectory, as he switched his degree from industrial engineering to electri-

cal engineering.

Two years later, he ventured to UC Berkeley for a brief but transformative summer school. It was here that California’s allure, with its burgeoning tech scene, captured his heart, diverting him from Wichita State.

Thus, Anwar’s academic journey took him through three different schools, starting at Wichita State, meandering through UC Berkeley and ultimately, San Jose State, where he completed a degree in electrical engineering and computer science.

Anwar’s professional journey kicked off as an intern at Netscape, a web browser company. He worked as a quality assurance engineer focusing on internationalisation and localisation.

As a quality assurance engineer, he had been breaking and testing products to shape product experiences with different teams. “There would be bug reviews where we would sit together with the product, engineering, design and quality assurance teams, and I would have debates over how a feature should be built”, he recalled.

That’s when something happened. It was a senior vice president who saw his potential during one such heated bug review session and encouraged him to explore the world of product management.

“One day,” Anwar narrates, “as I was having a heated bug review session one of our VPs asked me to stay back afterwards” – a moment he feared might lead to his dismissal. “To my surprise, he asked, ‘Have you ever thought about product management?’”

“What is product management?”, I asked in response. “What you are doing now”, he replied. That vice president was Marty Cagan, a well-known industry expert in product management.

This marked the beginning of a journey that would define Anwar’s career. “I transitioned into a role where I defined requirements, crafted customer experiences, and guided the product’s development. From that point forward, I never looked back”, he said.

The unexpected transition to product management led him to oversee technology products for platforms at Netscape. Later, Netscape was acquired by AOL (America Online) in 1999. Netscape’s acquisition by AOL marked the start of his 12.5-year chapter devoted to security, safety products, parental controls, and authentication products.

Anwar joined another major technology company in 2009, pivoting to PayPal where he was entrusted with the developer platform and technical integrations. This chapter spanned over six years. Subsequently, he joined Capital One, where he was tasked with spearheading agile data and digital transformation.

And then, in 2021, he made the leap to Citi. Since joining in November 2021, his role has evolved to oversee digital and data platforms for trade and treasury solutions globally.

Anwar’s career has mostly been at tech giants like Netscape, AOL, and PayPal, which were operating in an unregulated environment. In this domain, innovation soared without the

constraints of regulation. However, this is not the case with the banking sector, as it is one of the most highly regulated industries. So what prompted Answer to switch to banking, of all sectors?

He recalled, “I asked myself a question: Could I replicate the same scale of innovation in a regulated environment?” The prospect of taking the same principles of innovation but applying them in a regulated setting and at scale was what pushed him to take up this challenge.

“You might wonder, did I ever question my decision? Indeed, there were days of challenges. Yet, it was fulfilling. Changing the hearts and minds of regulators and educating them about the transformative potential of technology-based solutions was a rewarding pursuit.”

He added that in this era of rapid technological advancement, regulators worldwide are also recognizing the importance of embracing innovation

In his current role, Anwar is laser-focused on innovation. He and his team constantly seek ways to improve the client experience, make processes smoother, and provide valuable insights.

One significant change he and his team have introduced is design-led research. Instead of diving straight into coding, they begin by thoroughly understanding the business problem and conducting user research. “By involving design, product, and engineering experts, we ensure that we are solving the right problems in the best way possible. Our strategy revolves around assessing industry trends, competitors, and what our customers truly need”, he added.

Anwar and his team are focused on enhancing client experience. He believes that corporate clients deserve a consumer-like experience. One major focus is on speeding up the onboarding process. They achieve this by automating repetitive tasks using machine learning and simplifying user interfaces. “We are asking ourselves the big question: How do we digitise non-digital processes? How do we automate the digital ones? And how do we make it instantaneous?”, he said.

The team is now using machine learning to automate the experience by simplifying the documentation process, obtaining client information from public sources, and pre-filling forms. “This way, clients can get to business faster without the hassle of tedious form-filling.”

But Naveed Anwar’s story is not just about his journey alone. The fact is, he is the global head at a bank that just so happens to have an outsize impact on

Pakistan’s banking sector.

What makes Citi unique is the fact that – among the major global capital markets players in the world – it has been in Pakistan for more than six decades. Citi opened its first branch in Karachi in 1961 and has continuously maintained its presence in the country since then.

It is also the only major global investment banking franchise left in the country. That cannot be said of other global financial institutions, most of which have all left Pakistan by now, with very few exceptions. Chase Manhattan left in the 1980s, Bank of America in the 1990s, and JPMorgan and Credit Suisse tried in the early 2000s, but gave up within a few years.

So if the federal government wants to issue dollar-denominated bonds to investors outside the country, the only bank with a local office it can talk to is Citi. And this is not just a theoretical capability: it is one that Citigroup has actively cultivated, having served as the government of Pakistan’s investment banker on nearly all global bond issuances, and several privatisation transactions as well.

Citibank plays a crucial role in Pakistan’s financial ecosystem, facilitating local subsidiaries of multinational companies, e-commerce companies, shipping lines, and more in conducting cross-border payments, trade financing, and cash flow management.

It is not just its ability to offer global investment banking services in Pakistan that has given the institution an outsize level of influence in the country. It is also the fact that a majority of innovation in Pakistani banking has come from Citi.

In the early 1990s, Citibank revolutionised consumer banking in Pakistan by introducing products like credit cards, and auto loans, and expanding the mortgage market. Additionally, it localised its offerings. For instance, Citibank was the first bank in Pakistan to start issuing cheque books in Urdu. It created Pakistan’s first 24-hour customer service centre. It basically invented the concept of “priority banking” for high-net-worth clients in Pakistan.

While Citi initially focused on revolutionising consumer banking in Pakistan, it later exited consumer banking in 2012 and shifted its focus back to corporate and investment banking services for large global clients, local financial institutions, state-owned enterprises, and the government.

(Read: “Citibank Pakistan scaled back and became bigger than ever” to learn more about why the bank scaled back)

Anwar shared his vision of Citi. “At Citi, we have set an ambitious goal – to bank a billion people as an ‘invisible bank.’ We aim to embed our financial capabilities and experienc-

es into various platforms, including enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, treasury management systems, and e-wallets, to power the digital economy. Take an example: you take an Uber ride and pay Uber. Then, Uber needs to pay the driver – that is where Citi comes in. Our mission revolves around connecting people and creating value in this thriving digital economy”, he elaborates.

How does Citi accomplish that? Citi has several digital products under its belt, of which two are also available in Pakistan - CitiDirect and CitiConnect.

CitiDirect is akin to a user-friendly web portal. Just like a mobile bank application or a web application that enables customers to make daily transactions, CitiDirect empowers treasurers and chief financial officers to manage corporate finances efficiently. It simplifies tasks such as making payments, checking payment statuses, and even supplier financing. It’s a dashboard of financial control that echoes the convenience of consumer banking but for corporates.

So let’s say you are a multinational corporation that wants to avail transaction banking services with Citi because Citi, owing to its network in more than 90 countries, enables you to operate payments internationally. The first step is simple – opening an account, much like you would as a consumer. Once the account is open and funded, you can begin to transact globally, and see all your account information in an easy-to-use, streamlined and intuitive experience.

On the other hand, CitiConnect offers the same functionality but through seamless API (application programming interface) integration. (API is a set of rules and protocols that allows different software applications to communicate and link with each other).

Companies like SAP, and Oracle have provided ERP systems for the finance or treasury departments to manage their day-to-day operations. In CitiConnect, the Citi experience is woven into these systems through APIs. Picture this: you are sitting at your desk, using ERP, and you need to pay a supplier. Instead of taking a detour to the CitiDirect portal, you do it right here, within your ERP.

In other words, you click pay on your ERP system, and the payment is made through your Citi account in the background. You could even set up a recurring payment schedule for your supplier. Every month, like clockwork, the specified amount effortlessly transfers from your account. You are instantly notified of the transaction, allowing you to maintain a firm

grip on your financial transactions.

Let’s make it more relatable. Think of when you are shopping online, say on Daraz, and you decide to pay using your Jazz Wallet. You do not open your Jazz Cash account to make payment, instead, you enter the required information on Daraz’s payment gateway, and the amount is deducted from your JazzCash account. CitiConnect provides the same convenience but to the corporate world.

One of the recent initiatives launched under the leadership of Anwar is tokenization (tokenization is digital versions of coins or bills that represent real money).

Imagine a massive ship approaching a port by the border of Pakistan. Before the ship can park and unload its cargo, it has to make sure it pays all the fees required for entering the harbour. Now, envision a smarter way – powered by tokenized deposits and smart contracts. (Think of a smart contract as a digital agreement that does things automatically when certain conditions are met).

Here is how it works: as the ship reaches the shores, a special digital agreement (smart contract) with a tokenized deposit comes into play. This digital agreement is like a virtual handshake. It’s programmed to do specific things automatically. It triggers a chain reaction of automated payments.

First, it checks if the ship has paid all the necessary fees. If it has, the port authority gets its money right away as soon as the ship docks. But it doesn’t stop there. The smart contract also takes care of other payments, like when the ship needs to be cleaned. It makes sure that the people who clean the ship are compensated promptly, too. With each pivotal point, payments flow effortlessly, and the beauty of it lies in transparency and traceability. There is no need for someone to carry invoices and engage in lengthy processes including bank guarantees for the payments. Besides, these payments are recorded on a secure digital ledger, like a digital notebook. This ledger shows every step of the process, and it’s really hard for anyone to mess with it. It is transparent and easy to trace. “This is the future of financial transactions where every step is seamlessly tokenized, payments are automatic, and the entire journey is recorded on a secure ledger”, declared Anwar.

Apart from these solutions, Citi also empowers its clients’ decision-makers through data. “Data is the currency of the digital age,

and at Citi, we recognize its profound value. In today’s digital economy, mere transactions no longer set banks apart; it’s the intelligence we derive from data that truly empowers our clients,” explained Anwar.

Citi empowers its clients by providing insights like in a given month, these are the types of transactions you engage in. Consequently, you should maintain this specific balance in your account. It’s not just about the past; it’s about shaping the future with data-driven decision-making. It offers real-time insights and guidance.

“But we don’t stop there. We elevate your financial prowess with predictive billing. We don’t just tell you what’s in your account; we anticipate your needs. We reveal that, based on your typical cash balances, these are the liquidity levels you should aim for when conducting certain transactions. It’s a tailored, personalised approach, transforming data into actionable insights,” he added.

Despite his prolonged absence from working directly in Pakistan, his optimism about the country’s future remained unwavering. He pointed to the transformative impact of the gig economy, exemplified by platforms like Uber, on Pakistan’s job market and the concurrent rise in digital payment adoption. Moreover, he highlighted initiatives like Raast, which provided secure payment solutions, and the evolution of 1Link, originally an ATM network, which enabled utility payments.

“We have come a long way from the early days of the internet. Now, we are entering a new era – the internet evolution of financial services,” he remarked.

Anwar’s perspective extended beyond current advancements; he envisioned a new era in financial services driven by technologies such as distributed ledger and tokenization. This paradigm shift could potentially revolutionise the concept of money itself. He believed that central banks’ adoption of digital currencies could expand financial access, lower costs, and open new economic avenues, potentially reducing the size of the informal economy.

However, to realise this vision, Anwar emphasised the need for public-private partnerships, stressing that Pakistan was positioned to harness the benefits of the global digital economy. “Pakistan is standing at a pivotal juncture, armed with a burgeoning young generation that has grown up in a digital world. With over 190 million mobile phone users and growing penetration of smartphones, Pakistan is ripe for innovation” he said. n

Pakistan’s oil sector was dealt a significant blow in September, marking its lowest point since the Covid lockdown in March 2020.

The Oil Companies Advisory Council’s data for the month

paints a grim picture, revealing a staggering 34% year-on-year decline in petroleum product sales, dwindling to a mere 1.06 million tonnes. The culprits behind this collapse in sales are the soaring prices of petroleum, a reduction in overall demand, and increased pressure on the capacity of oil marketing companies (OMCs).

Furnace oil sales took a precipitous plunge, dropping 72% year-on-year to a scant 0.08 million tonnes. Similarly, sales of motor spirit (petrol) and highspeed diesel also suffered, decreasing by 18%

and 24% year-on-year, respectively, to 0.52 million tonnes and 0.39 million tonnes. On a month-on-month basis, cumulative petroleum sales contracted by 28% in September 2023, with furnace oil, petrol, and diesel sales all diminishing by similar percentages.

Q1FY24 saw total petroleum sales slump by 16% year-on-year to a disappointing 3.77 million tonnes — a stark contrast to the robust 4.49 million tonnes recorded in the same period last year. All product categories witnessed reductions — petrol, diesel, and furnace oil off-takes registered at 1.85 million tonnes, 1.44 million tonnes, and 0.35 million tonnes, respectively.

Acompany-wise breakdown reveals that Pakistan State Oil’s (PSO) offtake declined by a significant 37% year-on-year in September 2023 due to falling sales of petrol, diesel, and furnace oil by 13%, 23%, and an alarming 94%, respectively. Similarly, Hascol, Attock Petroleum, and Shell’s dispatches also decreased by 12%, 13%, and 30% year-on-year, respectively. On a cumulative basis for the Q1FY24 petroleum sales of PSO, Shell, and Attock Petroleum depleted by 19%, 16%, and 7% year-on-year, respectively. In contrast, Hascol’s off-take demonstrated a healthy growth of 35% year-on-year.

By the end of Q1FY24, PSO’s market share had slipped by 1.7% to 50.8%, compared to 52.4% in the same period last year. Shell’s market share remained static at a modest 7.2% year-on-year. Attock Petroleum and Hascol’s market shares rose to 10.8% and 2.7%, respectively. The cumulative market share across the remaining OMCs remained steady at a substantial 28.5%.

In conversation with Profit, Omar Shafqaat, Chief Operating Officer at Taj Gasoline, and Zeeshan Tayyeb, Group Chief Operating Officer at Gas & Oil Pakistan, identified the price of petroleum to be the stand out reason for the industry wide reduction in sales.

Pakistan saw the price of petroleum products reach their highest in September. Diesel rose by 12% from Rs 293/litre in August 2023 to Rs 330/litre in September, whilst the price of petrol rose by 14% from Rs 290/litre in August 2023 to Rs 331/litre.

Tayyeb, observing the decline in personal usage, underscores how consumers have curtailed their travel to only the most essential journeys. The spell of rains that swept across the nation in September further hampered mobility, exacerbating the already dampened

demand.

Turning our attention to the commercial usage of petroleum, Shafqaat elucidates, “Revisions in commercial freight typically span five to seven days. During this interim, truck owner-drivers predominantly operate on shorter routes, thereby impacting diesel sales.” He further expounds on the subject of diesel, stating that “the agricultural demand for diesel, which usually surges in Sindh around mid-September, has been delayed and is anticipated to rebound by mid-October.” However, Tayyeb remains sceptical about whether agricultural demand will be able to drive sales to levels comparable to the previous year.

The fluctuating nature of the price changes has also contributed to the dwindling sales. Petroleum prices witnessed a double increment in September. However, whispers of an impending decline were already circulat-

ing before the month concluded, with prices projected to plummet on the 1st of October. Shafqaat explains, “The volatile nature of the price changes led dealers to stock up at the month’s onset and reduce inventory towards the end. Consequently, both the beginning and end of the month saw significantly lower upliftments.” Contrary to expectations, neither Tayyeb nor Shafqaat attributed the smuggling of Iranian crude as a significant factor for the sales collapse. Shafqaat suggests that this aspect has simply been integrated into their industry estimates. There is also the final argument that the industry is actually constrained in selling petroleum products as well.

“Trade financing requirements have nearly doubled over the past year for the oil sector with letters of credit keeping pace. This inhibits the ability of the sector to sell even if it wants to” explains Tayyeb. n

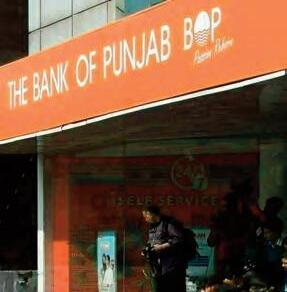

Last week, the Bank of Punjab (BoP) made an announcement that made anyone holding US dollars at their homes, or in their bank lockers pause: people could book a foreign currency term deposit and get returns as high as 9% per annum.

The rates announced by the BoP are much higher than what other banks are offering for the same product; in fact, they are the same as those offered on Naya Pakistan Certificates (NPC), which are available exclusively to overseas Pakistanis or residents with declared assets abroad. In fact the BoP

offer is even better in one aspect — while the minimum amount for the Naya Pakistan Certificates is $5,000, the BoP has no such requirement.

Why does this matter? Because when the NPCs were launched by the PTI government in 2020, there was significant criticism, including in this magazine.('Naya Pakistan Certificates are ridiculously attractive for investors. But here is why that is bad for Pakistan').

The NPCs were unfair to resident Pakistanis - the lucrative rates were unjustifiable considering the state of interest rates elsewhere in the world back then. They were and are available only to expatriates and not to an ordinary Pakistani who actu-

The Bank of Punjab is offering returns of up to 9% per annum on dollar term deposits, which are the same offered to those investing in Naya Pakistan Certificates

ally lives, works, and pays taxes.

So, for BoP to offer rates akin to the NPCs to Pakistani who do reside in the country is a major development.

Before discussing the BoP's offering, let's discuss what certificates of deposit, such as the NPC, are. A certificate of deposit or term deposit is a product through which people can earn interest on an amount deposited for a fixed time period. They usually offer a higher interest rate compared to savings accounts to make up for the loss in liquidity; in savings accounts, people can withdraw their money but with a certificate of deposit or term deposit, they cannot withdraw the money without paying a penalty or losing interest.

The Naya Pakistan Certificates were launched by the PTI government in 2020. They were aimed at shoring up foreign exchange reserves and financing the budget deficit.

The rates offered were extraordinarily lucrative. And some overseas Pakistanis and banks managed to leverage them to earn much higher profits (more on this later). Even for resident Pakistanis, the returns were great; according to Topline Securities, investors holding dollar-denominated NPCs made gains of 36% in rupee terms, making the certificates the second-best performing asset in 2022, one spot below gold at 41% and above the dollar at 28%.

In September 2020, when the NPCs were launched, the five-year US Treasury bond had a yield-to-maturity of approximately 0.27% per year. The Naya Pakistan Certificate was paying a yield of 7% — 6.73% above a comparable US Treasury bond. That difference in the spread between comparable US bonds and the government of Pakistan’s debt was staggering.

– than a typical government bond. Liquidity typically means that investors are willing to pay a higher price, and thus get a lower yield, for a fixed-income investment like a certificate of deposit. That is why certificates of deposit typically tend to have lower yields than bonds of similar risk and tenor.

So, the Naya Pakistan Certificates should have had considerably lower interest rates than they did.

The fundamental problem was that the government of Pakistan was raising financing at rates akin to a distressed debt investment, which only makes sense to investors when the entity raising that debt promises to fix the structural problems that got it into that distressed financial situation in the first place.

The certificates of deposit are backed by loans to the government of Pakistan. These are general-purpose bonds, meaning they are used to finance the government’s budget deficit rather than any specific projects.

Here is what that means: the government is borrowing at high interest rates in US dol-

lars to pay for mostly consumption expenses that it has undertaken in rupees. It will then have to pay back these loans at a time when the rupee will have likely depreciated, meaning the effective rupee interest rate on these loans is quite high.

The government’s rupee-denominated rates for the Naya Pakistan Certificates assumed an annualised rupee depreciation rate of 4%, when in fact, the historical average has been between 6% and 7% a year, depending on which time period one examines. Since 1992, the rupee has depreciated by an average of 6.7% per year. It depreciated by 28% in fiscal year 2023.

So, the effective interest rate the government is paying on the Naya Pakistan Certificates is much higher than it would otherwise be from any other borrowing source.

But then there is the fact that the Naya Pakistan Certificates are not – strictly speaking – bonds, but rather certificates of deposit. More specifically, they are (almost) no-penalty certificates of deposit, meaning there are no penalties for early withdrawal if one withdraws after the first three months.

That means that the depositors’ assets are more accessible – liquid, in finance parlance

Beyond the fact that the Naya Pakistan Certificates are a likely less competent way of implementing a bad policy objective, there is a more fundamental problem with them: they are unfairly generous to expatriate Pakistan and, by implication, render resident Pakistanis second-class citizens in their own country.

Aside from the accessibility for resident Pakistanis and no minimum deposit, what sets apart the BoP's term deposit from the NPC? For starters, while investors can prematurely

That, in itself, was a red flag.

encash NPCs after a period of three months, the rate of return will be equivalent to the nearest shorter maturity. For example, if the investor decides to encash it in the 7th month, he will get the rate of interest applicable on the six-month tenure. If he encashes it before three months — the shortest tenure — he will not get any profit.

On the other hand, the BoP's shortest tenure is one month. The bank also allows premature encashment. While no penalty will be charged on the principal amount, the investor will get the bank's savings rate for the number of days the deposit is held with the BoP.

Another major difference is that investors cannot pledge the BoP's term deposit with a bank to get a loan. However, under NPC Rules 2020, the certificates can be pledged to get a loan from an international bank.

Overseas Pakistanis (and the banks they were using) exploited this to earn returns that were more than double those being offered by the government. For example, an overseas Pakistani would invest $1,000 in NPC at a rate of 9%. He would then pledge it to a bank such as Standard Chartered Bank or Samba Bank and borrow $900 at a rate of 5%. He would reinvest it in NPC (again at a rate of 9%). This means he would get a return of 9% on the $100 and 4% — 9% profit from NPC minus the 4% he would have to return to the bank — on the $90. After repeating the process multiple times, the overseas Pakistani was able to get a return of up to 2.5 times. This is something an investor would not be able to do with BoP's term deposit.

BoP's term deposit offering is unique as the rates offered for smaller amounts — less than $100,000 — are much higher than other banks. For instance, one large bank is offering around 2% on deposits of $50,000 and higher, while another large bank is offering around 5.5% on deposit tenures six months and longer. How is the BoP offering such attractive rates?

The BoP said this is because other banks have large foreign currency deposits in low-interest-rate accounts. If they were to offer higher interest rates on term deposits, this might result in "cannibalisation" of their current low-rate accounts, i.e., customers might move their money from the low-interest-rate accounts to the higher ones, which would cost the bank more money. In addition, this would result in a much higher overall cost on their liability portfolio. Compared to such banks, the BoP is better positioned to offer higher interest rates because it has a smaller foreign currency deposit base.

"That is why the BoP is trying to capitalise on the current high demand for liability

products and build up its individual foreign exchange deposit; hence, the offering of this product and rates. For that, we will even operate on a cost-to-cost basis if required," the BoP stated.

For now BoP is the only bank offering high rates to retail customers, however, other banks are also known to offer similar rates on dollar deposits to their high net worth customers. So a customer of say Habib Metropolitan Bank with $100,000 to deposit may also be able to negotiate a rate of 9% without having to go to BoP.

For it to make financial sense for the banks to pay 7-9% return on dollar deposits, obviously they must be able to deploy these dollars at an even higher rate. They can not park these funds in US treasuries as the offered rates would be much lower. So what do the banks do then?

In general, banks deploy foreign currency deposits in US Treasury bonds and Pakistani government securities. The latter is done through foreign currency swaps with the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP).

The bank sells the US dollars to the SBP at a pre-agreed exchange rate. In return, the SBP provides the bank with rupees that can be invested in government securities. It charges a fee - let's say 5-6% - for the swap. Under the agreement, the bank will buy back the dollars from the SBP at a later date. If the return on government securities is 22% and the fee is 6%, the bank still makes a profit of 16%. If the bank is offering a rate of 9%, the bank will still earn a spread of 7%. The foreign currency swap is still a profitable bet since the SBP returns the dollars.

As stated earlier, investing in NPCs was limited to overseas Pakistanis and residents with declared assets abroad. In comparison, the BoP's USD term deposit is aimed primarily at ‘ordinary’ residents.

And it comes at an opportune time, according to officials at the BoP. In a written response to Profit's questions, the bank said, "With the recent crackdown on USD cash holdings and transactions, there is a need for avenues that can be provided to the holders of foreign exchange cash deposits — who are keeping them for saving purposes — to deposit them in a safe environment with decent returns."

Following a crackdown on the open market and suspension of the licences of exchange companies that were suspected of being involved in manipulating the exchange rate and engaging in 'off-the-books' deals, the rupee has appreciated in recent weeks. Since September 5, the rupee has gained Rs 23.48 per dollar in the interbank market and Rs 40 per dollar in the open market.

Atlas Asset Management CEO Muhammad Abdul Samad said given the recent appreciation, there would be pressure on people holding hard dollars to deposit them in banks and get returns. "It is a good initiative from a financial inclusion perspective," he said.

But while the BoP's rates are much higher than what other banks are offering and without a cap on the minimum amount, other banks may also offer comparable rates if the amount of dollars deposited is large (in the several hundreds of thousands). This means the BoP is specifically targeting retail investors who are presently not part of the banking system. It also means the BoP may be offering even higher rates to high-net-worth individuals.

But people hold dollars at their homes or in lockers for two reasons. First, the dollars were acquired with money that was not declared, or the dollars were bought through informal means, ie, the people concerned do not have a valid receipt from a licensed exchange company.

Second, people do not keep their dollars in foreign currency accounts because they are afraid they may be frozen if the country defaults, similar to what happened in 1998 following the imposition of sanctions by the US on Pakistan for nuclear tests in the 90s.

In January 2023, when there were already reports of shortages of physical cash dollars in the banking system, then Finance Minister Ishaq Dar said in an interview that the country's foreign exchange reserves stood at $10 billion — $4 billion with the SBP and $6 billion with commercial banks. And that both were "Pakistan's deposits." This created a bit of panic with the depositors. While Dar later clarified that his statement was taken out of context and the government would not take over foreign exchange reserves of commercial banks, this raised fears that the government might again freeze foreign currency accounts. The fears were exacerbated by the economic situation at the time; foreign exchange reserves dwindled to a critical level and a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a crucial bailout was in limbo.

With better macro economic optics now, will the BoP's high returns be enough to entice these people into keeping their dollars in bank accounts again? You will have to wait a few months for our follow-up story to find out. n

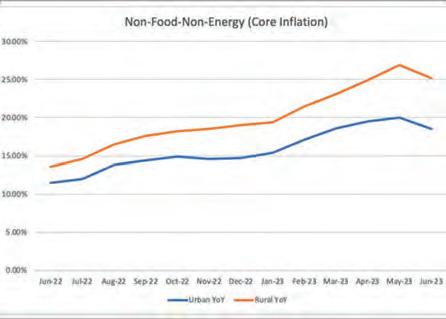

The inflation rate in September 2023, went up by 31.4% on a year-on-year basis. The CPI at the end of September 2023 stood at 2% higher than August 2023. While this is an alarming statistic in itself there is something that deserves a little more attention.

For the last few years, Pakistan’s rural areas face a higher value of inflation. The effect trickles down significantly even in core inflation, something that was not the case a few years ago. In a country where rural areas have historically had a higher food security and less reliance on energy, why is the inflation higher?

As some perceptive readers may already know, inflation is the rate of change in the prices. Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a widely accepted “bucket of goods” that is used to measure this change.

However, as seen in recent times, exogenous shocks such as international fuel prices or the shortages in supply of a certain commodity can have a huge impact on inflation. In fact most of the inflation that happened in Pakistan in the last 2 years, can be attributed to increase in taxes and oil prices in the international market (underscored by the falling value of the rupee) which makes imported fuel expensive, increasing the cost of production and eventually cost of living.

But what is core inflation and why is the calculation of core inflation important? Core inflation is crucial because it provides a stable measure of an economy’s underlying price trends. By excluding volatile components like food and energy, it helps policymakers make informed decisions about monetary policy, guides financial planning for businesses, shapes inflation expectations, and aids in risk assessment. It offers a clearer picture of persistent, structural inflation pressures, ensuring that economic policies are well-targeted and that individuals can

better navigate their financial landscapes. Coming to our scope, it was interesting to note that core inflation was also recorded at a higher level in rural areas than in urban areas. At the end of September, core inflation in rural areas increased by 27.3 % and in urban areas the increase was recorded at 18.6%. Similarly, core inflation for urban and rural regions, at year end- FY23 was at 18.5 % and 25.2% respectively. In the graphs below, it can be seen how rural inflation has differed from urban inflation over the course of the year.

So if the changes in the prices of fuel due to the rupee value or an increase in levy is not the reason for the price increase, then why is rural inflation higher?