08

08 After Daewoo and K-Electric, why is AsiaPak interested in Bol News?

12 The week everyone thought PIA was no longer a going concern

17

17 Reconfiguring the economy Ammar H Khan

19 Pakistan’s candy kings

26

26 Broker Categorisation: Separating the wheat from the chaff

28 Skin whitening: A lucrative business indeed, but at what cost to the consumer?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Daewoo, Thar Coal, and K-Electric. Until a few days ago this was the investment portfolio of AsiaPak Investments. That is until the company announced they had acquired Bol TV.

That in itself should raise the alarm for more people. Since its inception Bol TV has been mired in multiple scandals ranging from accusations of misconduct and bad journalism to staff protesting against the management for not paying salaries. The television channel which started off with a bang by giving politicians their own shows and hiring all the big names in the industry quickly found itself facing a credibility issue.

The fall from grace that followed was matched only by the channel’s financial woes. So why would anyone want to buy Bol out? According to Sameer Chishty, the man who will now be running the show, AsiaPak plans to gut the channel and build something new out of it.

But can they turn it around for a profit? The possibility is doubtful. Buying any kind of media organisation is a bad idea in this day and age. Journalism all over the world has suffered as a business and there is little hope in buying a television channel and making a profit off of it. Even if one pulled it off the future would be very uncertain. So what other reason could AsiaPak have to buy Bol News?

Some might say the answer is influence. After all, the only people buying television channels in Pakistan right now are politicians and businessmen that need the protection a media house can offer. Just look at Aleem Khan, the former PTI stalwart turned IPP leader who owns Samaa news. Or for that matter Blue World City, which is a real estate project that also operates a television channel by the name of Suno TV. But is AsiaPak looking for similar protection or do they have other reasons for acquiring Bol News? Profit sat down with Sameer Chishty to find out.

There are two reasons to own a television channel in Pakistan. The first is protection. People, particularly powerful people, often find it useful to have a voice that will stand up for them if they ever get in trouble. The other possibility is a more proactive approach. A sort of ‘get ‘em before they get you’ philosophy if you will. Even though the company has not disclosed the exact amount of the transaction, sources close to Chishty told Profit that the buying price and the capital injection by AsiaPak is collectively estimated to be around $27 million. That is a heavy price to pay for some protection. But when you’re dealing in even bigger numbers, sometimes it is worth it. And in recent days AsiaPak has very much been in the limelight.

AsiaPak investments, owned and run by two brothers Shaheryar and Sameer Chishty, is a private investment firm with operational assets in Pakistan and Hong Kong. The company has an expansive portfolio of prominent investments in sectors that include infrastructure, energy, power, transport, logistics and technology.

The company is the owner of Daewoo in Pakistan and has significant interests in multiple energy projects including mining rights in Block 1 of Thar Coal. K-Electric and Bol network are the newest companies the investors have acquired in recent years.

Sameer Chishty is the Executive Chairman of AsiaPak investments, a General Partner at SparkLabs Global Ventures, who formerly held the positions of Partner at Bain and Company, Senior Executive at Standard Chartered Bank, Managing Director at Merrill Lynch and Partner at McKinsey and Company. He is a seasoned investor, who invests in infrastructure and technology ventures.

“The goal really is to create not necessarily the biggest or best known channel because that’s more of a job for the existing media giants, who I have learnt a lot from and have

respect for. But we don’t necessarily want to be like them,” Sameer Chishty tells Profit.

Articulate and straightforward, Chishty asserts that he doesn’t have or want political clout. “I am an investor, I am driven by data and analytics which make me a rational decision maker. At AsiaPak we invest in areas where others fear to tread.” That has been the modus operandi of AsiaPak. They take an approach of adopting orphan assets — meaning they acquire companies which they feel have the potential to be profitable but just haven’t received the proper guidance and leadership.

He gave the example of another portfolio company Daewoo, which according to Chishty wasn’t a fashionable business when AsiaPak came in. “However we were able to build Pakistan’s biggest transport company, with inter and macro city services, as well as a cargo and logistics business. And we did this because Daewoo is a data driven business that uses new technologies, like telematics and AI to plot the routes and schedules, which did not exist in Pakistan before.”

“There is room for a tech-driven content platform, where more so than the nature of content, it is about how and to whom the content is delivered. And that is what we are doing with Bol. It is a technology play.”

He explained that AsiaPak is more interested in developing the underlying infrastructure and processes by which a piece of news, opinion or entertainment is delivered to a particular segment, in a streamlined and targeted way. According to Chishty, technology has embedded itself in most spheres of life but has yet to embed itself sufficiently in the media world. “It’s going to happen and we understand that it is risky but the rewards are going to be huge in terms of customer loyalty and shareholder value,” he concluded.

Chishty agreed that there are many channels that are owned by politically driven or self-serving individuals, but insisted that Bol is not meant to be a political platform for AsiaPak’s business interests or the owner’s political beliefs. “People shouldn’t care about what I believe in because I’m an investor

and all they should care about is how my investments can help develop a better basic infrastructure. We are in this for not the usual reasons. We want to give people what they want using technology and to create a company that can list on the PSX and be popular within the segment we want to target. The real competition is to get the most awake hours of people’s time to engage with the media we provide to them.”

When you look at AsiaPak’s investment portfolio, you will see businesses that span over sectors including infrastructure, energy, power, transport and logistics. A media network is the last thing that fits this expansive portfolio.

When Profit asked Chishty how he justifies his recent acquisition and how it relates to the existing businesses that fall under AsiaPak’s wing, he said that, “They might seem unrelated, I agree but there are uniting factors. Firstly, in all our investments, a common function is creating value through better use of technology and secondly the overarching goal is to build the country’s basic infrastructure.”

According to Chishty, Pakistan severely lacks a number of baseline services that don’t exist or are underdeveloped. He calls them the basic infrastructure, which would include electricity, water, gas data and transport. “These basic services and giant building blocks in the economy need to be bigger and a lot more robust, affordable and reliable,” he explained.

He continued, “These basic building blocks are where big opportunities lie and our

Sameer Chishty, CEO Bol News Network

goal for the past few years has been to build these basic blocks.” Chishty used the analogy of the iPhone problem to explain his point. “Imagine that you have developed a software or an app. If the iPhone or smartphones don’t exist, there will be little to no value of your application. But when you have the AppStore or PlayStore, suddenly your app has massive reach and then your job is to make that app good and offer a reasonable price.”

Chishty highlighted how a robust infrastructure with all the necessary services is easily accessible will open a world of opportunities. He believes that having scale is necessary to ensure that you get cheap and reliable services in all areas be it transportation, electricity, land or data. “That’s how we think all of these are connected and we provide a base infrastructure upon which others can build super-value-added businesses and applications, but that’s not our forte.”

With Daewoo, the company aims to fix the country’s transportation infrastructure. Similarly, with coal, they aim to solve the energy problem. “When we did Thar coal block 1, people said, “Oh my God, coal?” and I said, yes Pakistan needs cheap energy! It took us eight years, which is a lot longer than we expected, but what we delivered was 1320 megawatts of the cheapest energy into the grid. The good news is that the incremental output is much cheaper than the first set of output if you consider economies of scale and the subsequent benefits. So, if we convert all the coal power plants to Thar coal instead of imported coal, we can lower the cost of electricity.”

So, what unites AsiaPak’s investments that seem unrelated on face value, is the fact that each business comprises an important building block of the economy’s basic infrastructure, which the investment company aims to develop and improve. According to Chishty, it’s a technology business and ultimately it’s a

Let’s understand AsiaPak’s investment in Bol as a technological play, as they call it. When Chishty said that he wants to build a technology and data backed infrastructure for content creation and distribution, we had one pressing question.

Why invest in a legacy media company?

Before answering the question, Chishty recalled that when he was growing up there was one TV in their house and only one TV station called PTV but over the years, expectations have changed dramatically.

“Now, there is proliferation on the content provider’s side, in the content platform and pipeline end, as well as on the viewers side. There are millions of content providers and creators; everyone on YouTube and TikTok is a content creator. There are countless channels on Instagram that you can access from anywhere in the world, so the competition isn’t just between Channel 52 vs. Channel 53 anymore. The competition is those millions of people out there producing content on different platforms.”

He also highlighted how there is a massive increase in the platforms that deliver the content. Social media applications and digital media platforms have grown exponentially and people are not loyal or exclusive to just one platform.

“They can knit something together by using a combination of different platforms to create a brand for themselves and something much more powerful than just having a show on TV. So, all these content creators and providers mix in unique ways, and gone are the days of one production company for one TV

Now, there is proliferation on the content provider’s side, in the content platform and pipeline end, as well as on the viewers side. There are millions of content providers and creators; everyone on YouTube and TikTok is a content creator. There are countless channels on Instagram that you can access from anywhere in the world, so the competition isn’t just between Channel 52 vs. Channel 53 anymore. The competition is those millions of people out there producing content on different platforms

station into one TV,” Chishty explained.

“The screens have also grown and come in all different shapes and sizes now. One household may have multiple phones, TVs, tablets and computers. But then there are households in Pakistan where there is one, maybe two screens if they’re lucky.”

He maintained that the difference by device ownership or proxable income and affluence is just one facet. There’s also a psychographic element of what different people want, in terms of the combination of news, information and entertainment, according to Chishty. He believes that people’s expectations from news have changed, whereby news isn’t just about news anymore. “Not everyone wants to watch politicians screaming at each other anymore. There’s a segment that wants to hear political views, discussions engaging in how opinions distort news and a growing demand, especially in younger segments, those below 35, for technocratic and intelligent debates.”

Chishty shared that their research suggests that viewers prefer to know more than just news of what’s happening. “They want to know how it affects them and what it means for them, delivered to them in a simplified or clarified way. All that combined is a tall order. So, we want to provide news that’s important for people to know just so they can be functional adults in the society, but also news that they are interested in knowing, which can differ from person to person or segment to segment.”

The initial aspect of their plans involves taking a broad perspective on the entire media value chain, which is currently undergoing swift and substantial transformations. “Whether it’s in the realms of production, delivery, or consumption, this landscape is evolving at a remarkable pace,” said Chishty. “Our aim is to spearhead these technological advancements and innovations. We’ve yet to explore the profound potential of technologies like AI, limitless bandwidth, and interactive media,” he added.

It is crucial to emphasise that technology is the cornerstone underpinning this entire process and value chain.

Second is the asset itself. Chishty believes that Bol has the best technology for this job, at least in Pakistan. This involves the entire technological backend of delivering content through a channel and enabling people to consume said content on different platforms. “The studio, production, broadcast facilities, as well as the internet, the digital media and the social media teams at Bol are second to none in the country and the proof is in the

way that they have efficiently built amazing technologies in-house and adapted external technologies.”

He believes that Bol has the strongest technological platform for creating, producing, delivering and consuming media.

According to Chishty, the whole concept of a data and tech driven system of content generation and provision is to hire experts and empower them, as well as to use analytical techniques and professional management techniques to decide what content should be delivered on which platform.

“Discovering what psychographics and media preferences clusters of consumers have is the job of our marketing team and the job of our content team is to create that content and partner with production houses to produce that content. And the job of our news and entertainment channel is to put that out there and for the distribution team to make that content available to the right segments within the digital space,” he explained.

“My job is to enable all those capabilities by making sure that all the technology is available and cutting edge. We will provide the capital for the team to do all this wonderful work that they’ve successfully argued for with data and analysis, coupled with the art of their experience,” he concluded.

So, basically the media landscape has experienced a drastic change, but broadcast has so far taken a backseat to this development. AsiaPak’s acquisition of Bol involves assisting the technological development within this sector to match the technologies used by broadcast media around the world.

Chishty and his new team have big plans for Bol. Considering their past investments, one thing about the Chishty brothers is that when they take on a new challenge, they deliver. Consider the example of Daewoo, which started off as an inter-city transport service that would go to only 11 cities. It is now an inter-city and metro service that spans over 55 cities, along with an additional courier and cargo business arm, which according to Chishty will grow as the roads infrastructure also improves.

Moreover, after the acquisition of K-Electric, the company has proposed to the government an ambitious plan involving the conversion of the 660mw Jamshoro supercritical imported coal-based power plant into indigenous Thar coal for the next thirty years.

However, Bol is a whole other ball game, with its poor reputation, controversial past and the subsequently terrible brand equity. Profit asked Chishty how he plans to shed the baggage that he inherited along with Bol’s cutting-edge technology. His response suggested

that despite it being a challenging task, he is confident that they will overcome it.

Chishty proclaimed that, “I think it’s time to turn the page. I cannot comment on the past because I wasn’t here. It is important to understand there are places where change is welcome and necessary and then there are places where no change is needed. We have installed a new ownership structure, with me being the newly installed chairman and CEO. We will be announcing a new board of directors and an executive team soon.”

According to Chishty, the new executive team consists of individuals that have sterling professional credentials and he recognises that there were some people at Bol who believes to have outstanding technical skills, creativity and work ethic that he is eager to work with. He also shared that the company has received applications from promising candidates who wish to work with Bol under the new ownership. “The overwhelmingly positive response from people shows that it is time to move one from the past and focus on creating a better data and media infrastructure.”

Chishty, refusing to comment on the scandals involving the previous owners of his new company, shed light on some of the positive aspects of Bol to justify his acquisition. “Apart from all the bad things that have come to light in the past, it cannot be dismissed that Bol has a world class technology platform that the founders have built. It is not easy to build something like that. We have and will continue to make necessary changes and regear into a fresh direction but hold on to what’s valuable and has worked in the past. The idea is that with the capital we are injecting and the direction we are going in, we hope that people will see the opportunities and the value that we will be offering,” he stated.

When Profit enquired whether a rebranding is to be expected, Chishty answered, “I have been involved in 25 acquisitions as an advisor, as an executive and as an investor and I’ve learned a few things, by making mistakes, as well as by being part of spectacular successes.”

The first thing he said one does after an acquisition is to take a hippocratic oath. “This is an oath where you sincerely pledge to do no harm. There are some terrific talents inside Bol, who we have retained and want them to come to the forefront. Once we have ‘done no harm,’ then we start focusing on the value. We aim to create value by partnering with developers and content creators, some in house, some outside, some in Pakistan, others abroad, and put them in front of our audience.”

The question now remains; will Bol be able to have a fresh start and will Chishty be successful in his ambitious endeavours to revamp the network into a technological swirl pool of content generation? n

This is probably the closest time we’ve come to a solution for the carrier, we just need to decide what we want to do with it nowBy Daniyal Ahmad

Some phenomena in life are so ingrained in our minds that we take them for granted: the Earth’s roundness, the sun’s faithful journey from East to West. Likewise, in today’s Pakistan, it seems almost a self-evident fact that Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) is always on the verge of collapse. One could glance at any headline about PIA’s fortunes and be unable to tell which year of the past two decades it belongs to.

The story, from PIA’s glorious beginnings as an aviation pioneer that spawned a generation of companies to its current state of financial turmoil, has been regurgitated ad-nauseum. So much so that it’s perhaps a children’s tale at this point. It is also something that has become a quarterly tradition that floods our airwaves like clockwork when the company reveals its financial performance. However, this time the alarm bells are ringing a bit too loud to ignore.

In the past week, PIA has encountered one media calamity after another, reaching a zenith when the Government of Pakistan pronounced its verdict to jettison PIA and finally sell it off. The twist this time is that the Government is actually in dire need of cash, and might not have any tolerance for these losses anymore. The Government also has new regulatory instruments that could accelerate the sale if it so wishes.

The only hitch is, PIA contends it has finally overcome its obstacles and attained partial profitability again. It beseeches for some governmental assistance on debt resolution, vowing it could soar to new heights.

So, what’s going on?

Our story begins on Saturday, 9th September, when PIA announced on its X (formerly Twitter) account that it had secured the government’s approval for assistance with its debt. That tweet, however, mysteriously disappeared from PIA’s X account without a trace. No one knows when or why it vanished, but in retrospect it foreshadowed the events to come.

Fast forward to Monday, the 11th of September. The media was abuzz with the revelation that PIA had been compelled to ground its fleet due to a severe liquidity crunch threatening its operational viability for the ensuing months. Higher than usual flight cancellations evidenced the grounding of part of the national carrier’s fleet.

The subsequent day brought more disheartening news: PIA might possibly default on its payroll obligations for August as some of its bank accounts had been freezed.

As if on cue, on the next day, another revelation surfaced: an anonymous Director at the national flag carrier confided to a news outlet that the airline was on the brink of cessation and predicted its collapse by the 15th of September. The only glimmer of hope on the day was that it was reported that PIA’s accounts with the Federal Board of Revenue had been unfrozen, and it could subsequently process salary payments.

The icing on the cake came on the 14th of September. The Government declared it was injecting Rs 14 billion into PIA’s coffers but simultaneously announced plans to privatise the beleaguered airline. In fact, a new Federal Minister was inducted and tasked with privatising the company on his very first day.

This whirlwind of events, dear reader, transpired across a mere four-days. At the time of writing this piece, the 15th of September, PIA has not collapsed. So, what on earth happened?

“Amidst a tumultuous financial landscape, we were eagerly anticipating an influx of funds. Initially slated for the commencement of the week, an unforeseen delay served to amplify our existing predicaments,” elucidates Abdullah Khan, the Head of Marketing & Corporate Communications at PIA.

“Let me set the record straight — whispers of us halting operations on the 15th of September, or any time in the future, are nothing more than baseless rumours. PIA is a stalwart in the industry, firmly rooted in sound business principles. Should the storm continue to rage, our strategy involves a calculated reduction in operations,” Khan adds, dispelling any misconceptions.

“However,” Khan’s tone grows sombre, “the relentless onslaught of negative media speculation has sent shockwaves through our network of associated parties. It’s been akin to a snowball effect, with many succumbing to a pessimistic outlook.”

PIA is a stalwart in the industry, firmly rooted in sound business principles. Should the storm continue to rage, our strategy involves a calculated reduction in operations

Abdullah Khan, Head of Marketing & Corporate Communications at PIA

In an additional revelation to Profit, Khan categorically stated that no overseas aircrafts have been grounded. The cancelled flights were due to their ATR aeroplanes suddenly requiring unscheduled maintenance — a decision that was communicated well in advance, a full 10 days prior. And the anonymous Director who cried wolf? The Senate Committee on Aviation is hot on their trail.

So, is all well in the PIA camp? Not quite. PIA indeed needs to address their burgeoning debt issue — a fact they have openly acknowledged. The current situation is far from ideal, to put it mildly.

Let’s cut to the chase. PIA’s cash flows are in a state of chaos. A retrospective glance at PIA’s cash flows from 2017 to June 2023 paints a grim picture. PIA only managed to keep its head above water for a fleeting one and a half years. The remaining five years saw PIA grappling with negative cash flows from its operating activities. In layman’s terms, PIA was bleeding money from its core airline operations. So, how has it managed to stay afloat? The lifeline has been debt.

During the aforementioned period, it was only in the first six months of 2023 that PIA managed to repay more loans than it borrowed. That’s not to say it didn’t borrow. It did. This borrowing spree has been the lifeblood of its operations for the past six and a half years. Is this a sustainable model? Far from it.

PIA’s finance costs for 2022 alone amounted to a staggering Rs 50 billion — a record high over the past six years. Yet,

barely halfway into 2023, PIA has already incurred an alarming 74% of this cost. It is this escalating cost of finance that prompted PIA to engage the government in a dialogue for financial aid to alleviate its debt burden.

Read more: Can the Govt’s injection help PIA build on its gains in 2023?

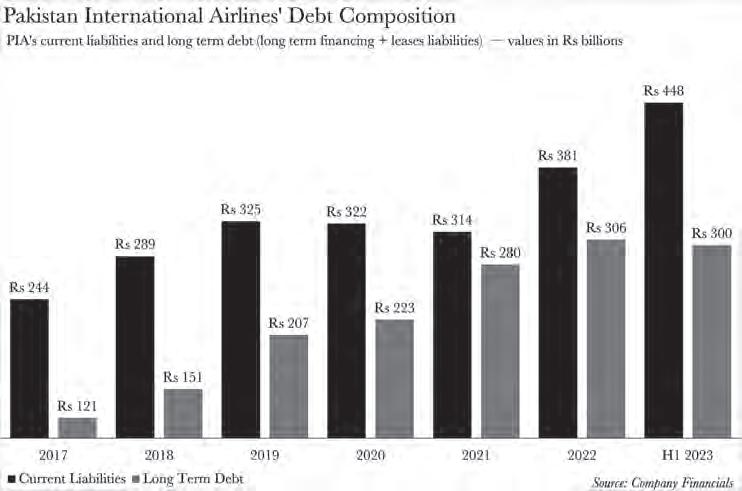

The most conspicuous reason for PIA’s soaring finance costs is perhaps the increase in the policy rate by the State Bank of Pakistan. However, PIA was bound to hit a wall eventually due to its precarious debt composition.

A closer look at it reveals a stark contrast between its short-term and long-term debt. The former has consistently outpaced the latter each year for the past six years.

If we factor in PIA’s advances from its subsidiaries and deferred liabilities (including pension obligations and vehicle redelivery expenses), its long-term liabilities do surpass its current liabilities. However, when it comes to the structure of PIA’s debt, short-

term debt takes precedence over long-term debts. This is noteworthy because ideally, debt should not be structured in this manner. The longer the maturity term of the debt, the lower the interest rate that is subsequently attached to it.

So, is PIA’s finance department manned by short term debt enthusiasts? Not really. Short term debt is the kind of debt that is most easily available to the company. Now that might sound odd upon a first read. Why are banks lending short-term debt to a company already crippled by it? Do the banks that PIA lends from not have any form of risk department whatsoever?

“All of PIA’s lenders have structured their debt against specific routes as security,” explains Nadia Ishtiaq, Managing Director (Corporate Finance) at KTrade. What does any of this mean? The revenues collected from these routes are essentially given to the lenders to repay the principal and interests in return for the funds they lend to PIA. The banks are all too comfortable with this method too.

“The lenders don’t have any problem in giving the debt because they know that they are going to get paid through PIA’s route revenue, which is essentially collateral. It’s a waterfall mechanism, but at the end of the day it doesn’t leave PIA with a lot of money,” Ishtiaq continues. Can we then fault the banks for feeding PIA’s addiction? Yes. However, many don’t want to lend PIA long-term debt because they’re apprehensive about the company’s long-term future. This, Profit confirmed with one very senior banking professional. Very senior.

So, where does that leave us? Without pointing fingers, it’s just the tale of an organisation trying to do whatever it can to stay afloat in all honesty. The only problem is that it’s a public sector company, and therefore taxpayers are also paying the price.

Now, PIA is cognisant of all of this.

Every time PIA registers a deficit, it’s akin to daylight robbery. Its debt structure is inconsequential; the sheer magnitude of the total debt stock renders it insurmountable

Yousuf Farooq, Director of Research at Chase Securities

They even have a proposal to fix the mess.

PIA’s contention, a point elaborated upon in our aforementioned article, is that a restructuring or assistance with its debt could be the lifeline that allows the company to turn a profit. It highlights the stark contrast between its operating profit and net profit in its performance for the first six months of 2023. The company outlines how it turned an operating profit, but was unable to capitalise on its gains due to its cost of finance, and subsequently reported a final (net) loss.

There is merit to PIA’s argument. Its heightened cost of borrowing is due to its debt composition. However, this presents PIA with a potential silver lining. The more funds it can allocate towards reducing its short-term debt — currently standing at Rs 448 billion — the more it stands to gain from reductions in borrowing costs.

There’s no denying that PIA has achieved the unthinkable by managing to turn an operating profit. Whether PIA can sustain its winning streak for the remainder of the year remains a mystery. However, there is potential upside to PIA going forward into the remainder of the year. The flag carrier has made progress on regaining access to its routes in the western hemisphere, which are also some of its most lucrative.

If we were to take an even more macro perspective then we could point to the International Air Transport Association’s (IATA) consultancy business plan 2022-26 for the flag carrier. The plan, touted by IATA, could transform the flag carrier into a profitable entity by 2026.

However, not everyone shares PIA’s optimism about its turnaround strategy.

“Every time PIA registers a deficit, it’s akin to daylight robbery. Its debt structure is inconsequential; the sheer magnitude of the total debt stock renders it insurmountable. It’s a veritable abyss for taxpayer money and borrowed funds, a burden that our future generations will be saddled with,” proclaims Yousuf Farooq, the Director of Research at Chase Securities.

He adds, “In its current state of operation, PIA is a sinking ship, leaving lenders in a quandary. The citizens of Pakistan are left with no choice but to bankroll this debacle until privatisation ensues.”

Now, the Government seems to be thinking along the same lines as Farooq. At least based on their most recent stance regarding PIA. However, as many times as we’ve all heard about PIA’s financial woes, we’ve also heard about how it was going to be privatised. As it stands, based on historical precedence at least, it seems doubtful the government will pull through with the decision to privatise PIA.

But let’s assume, for argument’s sake, such a deal, however unlikely, was near fruition; what would it look like?

In the realm of PIA’s potential transformation, two primary transaction models emerge as contenders: the division into ‘good company/bad company’, and the bifurcation into an Operating Company (OpCo) and a Property Company (PropCo). It is unequivocal that PIA must undergo a metamorphosis, for its survival as a singular private entity seems financially unfeasible.

Let’s start with the ‘good company/bad company’ model.

“Envision extracting the aircraft, the profitable routes, the operations yielding revenue, the skilled workforce, and all other profit centres, and amalgamating them into a single entity,” elucidates Asad Ali Shah, a former Country Managing Partner at Deloitte. “The remaining liabilities, surplus staff, and all other loss centres are then relegated to a separate entity,” Shah adds.

The fate of these two entities? The ‘good company’, now streamlined and profitable, is primed for privatisation, while the ‘bad company’ remains under governmental purview for future strategising. The government stands to gain through taxation and reduced losses from the ‘good company’, while simultaneously devising debt management strategies and severance packages for redundant staff. A similar strategy was successfully employed during K-Electric’s privatisation.

Turning our attention to the OpCo/ PropCo model, we see another approach.

“PIA’s hotels and other businesses are carved out and consolidated into the PropCo, which can then generate revenue through leasing. The objective is to segregate the core business from ancillary ones. PIA and its core aviation busi-

PIA unfurls an unparalleled opportunity for any ambitious newcomer yearning to penetrate Pakistan’s airspace, or an incumbent aiming to fortify their position

AsadAli Shah, former Country Managing Partner at Deloitte

ness form the OpCo, which is then privatised to the highest bidder,” elucidates Ishtiaq.

Ishtiaq also highlights a “pay as you earn” model, albeit one that has yet to be implemented in Pakistan’s privatisation schemes. Despite its existence among a plethora of other models, it is anticipated that the government will likely opt for one of the two aforementioned models should they proceed with privatisation.

Now that we know what a future PIA might look like, the question that inevitably arises in every mind is — why would anyone desire it? Moreover, the conundrum persists — could one possibly trade it for its fair value, especially when potential buyers are acutely aware of your desperation?

PIA is a negative equity company. Negative shareholder equity is a chilling scenario where a company’s liabilities to its investors eclipse the worth of its assets. In layman’s terms, when a company’s mountain of debt towers over the aggregate value of its assets, even after a complete liquidation, it is branded with the ominous label of negative equity.

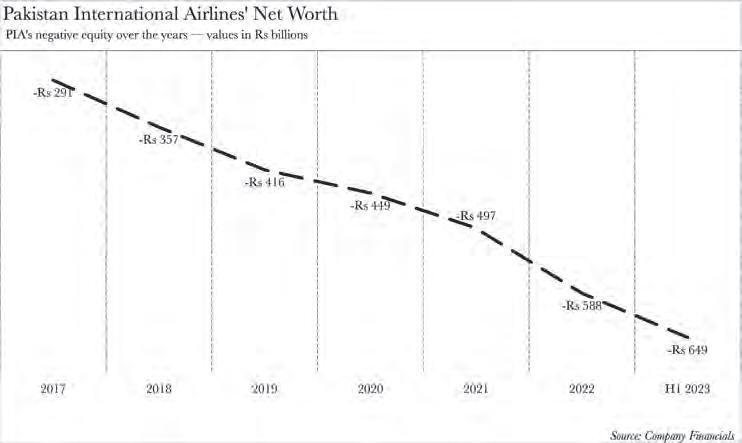

The fiscal abyss that PIA finds itself in has only yawned wider with time. The negative equity has mushroomed from Rs 291 billion in 2017 to an astronomical Rs 649 billion in June 2023. This gargantuan sum also symbolises the debt albatross that any prospective buyer would be saddled with upon acquiring PIA. Does it make sense for anyone to want to buy it? Surprisingly, yes. Shah explains with an air of optimism, “PIA unfurls an unparalleled opportunity for any ambitious newcomer yearning to penetrate Pakistan’s airspace, or an incumbent aiming to fortify their position. While the buyer would need to brace for the depreciation of the rupee earnings, they stand to reap rich rewards from the dollar-denominated earnings accrued from Pakistanis embarking on overseas journeys. Moreover, they would not only carve out a niche in the country but also tap into the vast and untapped reservoir of the diaspora,” Shah elaborates with a glint of hope.

And what about the elusive fair value? “Once a deal advisor is appointed, rigorous rounds of due diligence are set into motion. A reference price is meticulously calculated based on factors such as net asset value, future cash flows, and potential dividend streams. In PIA’s case, it will likely hinge

solely on the net asset value. However, once this reference price is etched in stone, bidding commences ensuring that the final price emerges as transparent as daylight,” Ishtiaq elucidates.

However, it’s plausible that PIA will change hands at a bargain price — a scenario that isn’t without precedent. “Pakistan is perpetually shackled by financial strain. We procure loans at sky-high interest rates and foreign exchange at premium rates. Investors seeking equity demand higher than average dollar returns due to the heightened operating risk associated with our country. This doesn’t imply that our business operations should grind to a halt,” Shah adds with a note of defiance.

In all likelihood, PIA will be sold at a discount unless the Government can miraculously make it profitable before divesting it. If that were feasible, privatisation wouldn’t have been mooted in the first place. While PIA does have a blueprint to potentially extricate itself from this quagmire, the Government appears sceptical. Simultaneously, if the Government harbours doubts about PIA’s viability, it would need to dangle enticing carrots before potential buyers. What do these incentives typically entail? Imagine selling a product priced at Rs 100 for Rs 70 to ensure completion of the transaction and asking the buyer to address any issues that rear their heads subsequently. What you get as the final amount after your carrots hinge on the base value — and PIA’s base value currently languishes at negative Rs 649 billion.

One certainty amidst all this uncertainty is that indecision carries a hefty price tag. If the rupee plummets further or if policy rates soar, exchange losses and already exorbitant finance costs will spiral out of control. The government must either place unwavering faith in PIA and fix it, or sell it outright without further ado.

While opinions may be polarised on whether privatisation should occur or not, there seems to be consensus that maintaining the current fiscal position is untenable, much to the detriment of the economy, but more importantly the taxpayer. n

The lenders don’t have any problem in giving the debt because they know that they are going to get paid through PIA’s route revenue, which is essentially collateral. It’s a waterfall mechanism, but at the end of the day it doesn’t leave PIA with a lot of money

Nadia Ishtiaq, Managing Director (Corporate Finance) at KTrade

Pakistan is stuck with an economic model that is disproportionately dependent on consumption. On a macroeconomic level, the Gross Domestic Product of a country largely comprises of household consumption, government consumption, investments, exports, and imports. With the exception of imports, all other factors add to the GDP, while imports have a negative impact, and are often adjusted against exports, and referred to as net exports. Pakistan over the last ten years has been maintaining consumption in excess of 80 percent of GDP, and more recently its contribution to GDP has been as high as 90 percent in FY-22, and 88 percent in FY-23.

Excessive reliance on consumption has led to a scenario where consumption is effectively driven by imports. GDP growth is fueled by consumption, which is inadvertently fueled by imports. The foreign currency required for funding these imports are provided by a mix of exports, remittances, and external debt. As consumption continues to take up a significant component of imports, sufficient resources are not available to utilize imports for investments, resulting in slowdown in formation of capital, or any industrial base that can catalyze any growth in exports. Consumption oriented growth results in an increase in imports, necessitating availability of foreign currency to pay for such imports. As imports continue to outpace exports and remittance, and in the absence of any foreign investment, foreign currency reserves continue to erode, eventually resulting in a position where the country does not have sufficient foreign currency to finance its imports.

In absence of adequate foreign currency, the country keeps on borrowing more external debt to fund the same consumption. The same has been happening for the last ten years where foreign currency liquidity

was easily available due to close to zero interest rates. This led to a substantial increase in external debt over the last ten years, which primarily fueled consumption, while industrial growth remained muted. As interest rates have increased globally, foreign currency liquidity has dried up, resulting in a scenario where it is getting difficult for Pakistan to raise external debt to fund its consumption oriented growth. As the world moves away from an environment where interest rates are not close to zero anymore, and as households and sovereigns across the world try to recover from an addiction to debt, ability to attain sustainable growth will remain compromised.

In the current environment, the ability of Pakistan to grow at a GDP growth rate of more than 3 percent without making any change to its composition of GDP, and its tax regime will remain compromised. Any consumption oriented growth will require foreign currency to fund the imports, which will eventually fuel consumption – in absence of industrial investments, increasing export earnings may also not be possible. It is estimated that the country would require additional external debt of more than US$ 7 billion every year, if it continues to grow at 4 percent or more, without changing its consumption oriented model. Ability of the sovereign to raise debt in an environment where it already has a debt overhang is not just impossible, but also does not bode well for the sustenance of the economy at large.

If there is any serious thought about enabling sustainable economic growth for the country, it can only be done through reconfiguration of the economy from a consumption oriented economy, to an economy that is concentrated on investment. The investment to GDP ratio in Pakistan averages in the range of 13 percent over the last ten years, whereas that for lower middle income countries is at 30 percent.

There is a dire need to invest heavily in the economy by sourcing informal capital that is sloshing around as currency in circulation and driving up prices, and accelerating an industrialization process through the same. More consumption oriented growth will not allow growth at more than 3 percent annually on a sustainable basis, which is only a few basis points higher than the population growth rate. The failure of policy makers to reconfigure the economy is pushing the population towards poverty as consumption oriented growth remains unsustainable, while ever increasing demand for foreign currency continues to depreciate the local currency.

If policies are not amended, and the structure of the economy is not amended we may get stuck in this low-growth loop for years, and even decades to come.

By Abdullah Niazi

By Abdullah Niazi

Sometimes the big guy is exactly that — the big guy. And on most occasions when the Goliath comes out on top, they don’t leave more than a few crumbs for the many proverbial Davids to fight over.

But on other, rarer, occasions the small players are not quite as small as you’d think. The picture is similar in Pakistan’s snacks and confectionery market. As one would expect, the largest players in the market are English Biscuit Manufacturers (EBM) and Mondelez Pakistan. EBM is a homegrown company that has been around for the past five decades and has produced household brand names such as Peek Freans and Modelez is the international company that owns and operates Cadbury among many other brands.

Together, EBM and Mondelez rule over the market for chocolates, confectionery, biscuits, and sugary sweets in Pakistan, which is worth just over Rs 250 billion. Since the share

of the biscuits market is the largest out of all the categories EBM is also the biggest company in this business, controlling over Rs 80 billion in total retail sales. Mondelez is fast on its heels with total retail sales worth just over Rs 70 billion. Together the two control nearly twothirds of the total pie with net retail sales of Rs 150 billion.

And while Mondelez and EBM have created brands that have brought them this success over the course of decades, there is one other competitor that is not far behind. Founded in 1988, Ismail Industries is another local player in the sugar snacks, chocolates, biscuits and confectioneries market that has made a name for itself. Under this Candyland brand name, Ismail Industries have produced some or the most popular snacks in Pakistan including Cocomo and Chilli Milli - both of which are market leaders in their respective categories.

While they are behind EBM and Mondelez it is not by much. Ismail Industries in 2022 recorded gross retail sales of nearly Rs 60 billion, indicating they have a market share of nearly one

quarter. What is perhaps even more surprising is the rapid pace at which Ismail Industries has grown and the diversification they have shown in their business.

Market analysts often lump snacks into one massive category. So in an overall snacks category, for example, EBM would be the leader with the biggest market share followed by Pepsico which has a massive share in the market off the back of its potato crisps brands. But for the sake of this story, Profit wanted to look at a more specific segment of the snacks market: sweets.

To this end we acquired data for three different segments within the snacks market that fall within the category of sugary snacks. These segments included chocolates, biscuits, and sugar confectionery such as candies and jellies. The results are telling.

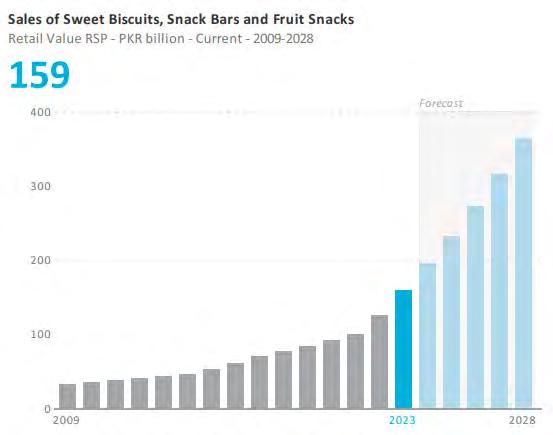

To start off with the overall sugary snacks, the market was worth just over Rs 250 billion in

EBM and Mondelez are firmly placed in their positions as market leaders. But there is one local competitor that promises to show some fight

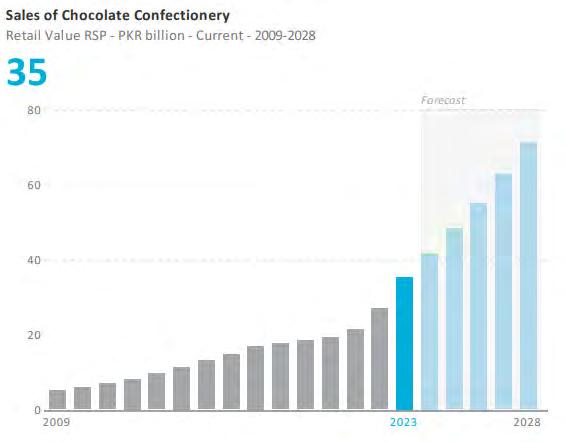

2022. According to the data acquired by Profit, the biggest segment within this is for biscuits which make up a whopping 63% of the total sugar snacks market with gross sales of Rs 159 billion last year. Candies, jellies and other sugar confectionery comes in at a distant second with gross sales of Rs 56.7 billion in 2022 while gross sales for chocolates were also far behind with gross sales of Rs 35.2 billion.

But these are just the initial numbers estimating the size of the market. Within these segments the distribution of what sells and what doesn’t tells a much larger story.

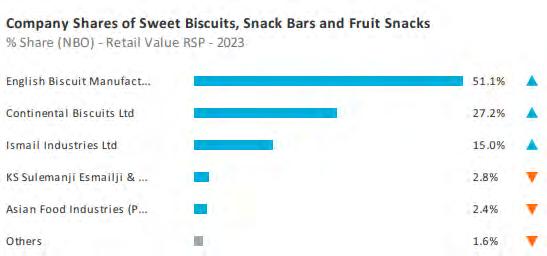

English Biscuit Manufacturers is big. In 2022 the company made gross sales worth over Rs 81 billion which makes them the single largest player in not just the sugary snacks market but in the snacks market overall. According to a Euromonitor report on the overall snacks segment in Pakistan EBM had nearly 18% of the market share in 2023. The closest competitor to them was Pepsico.

This means EBM obviously dominates the sugary snacks market as well. With gross sales of Rs 81 billion it makes up nearly a third of the entire market. What is even more impressive is the fact that EBM produces nothing other than biscuits. They have a diverse portfolio within the biscuits market with major brand names such as Sooper, Marie, Pik biscuits, and others. But outside of this, EBM does not produce any chocolates, toffees, boiled candies, or jellies.

Founded in 1966 under the name Peek Freans by Khawar Masood Butt, EBM entered a market that was mostly dominated by biscuits made in local bakeries. The reason the biscuit market in Pakistan is so massive is because of the high consumption of the sweet treats with tea. Pakistan is one of the largest tea consuming nations in the world, coming in at number four on the annual per-capita tea-consumption scale. The average Pakistani consumes tea made with 1 kilogram of processed tea leaves.

And just as tea is served in homes, offices, and dhabbas all across the country it is consumed along with biscuits. This is why the market for biscuits made gross sales of over Rs 159 billion last year. As the leader in this segment, EBM controls more than half of the market. This dominance has existed for years now and EBM has continued to grow along with the market. In 2014, according to a Nielsen survey, EBM made gross sales worth Rs 22 billion in a biscuit market that back then was a Rs 43 billion industry. Within the biscuit segment EBM’s dominance is complete. Their closest competitor is Continental Biscuits. Another homegrown company, Continental started operations in 1984 after being founded by Hassan Ali Khan in Karachi. The company controls the LU brand which has the rights to Oreo in Pakistan as well as other iconic biscuits such as Prince, Tuc, Tiger, Candi and Gala. One of the immediate

things that becomes clear is that within the biscuits segment EBM and Continental have very different areas of interest.

With their early mover advantage, EBM has focused on producing plain biscuits that go well with chai. Sooper in particular has become popular across the country in both urban and rural settings as the biscuit to be served with tea. Similarly, Marie and other plain dunkable biscuits such as the Pik biscuits have been a big part of EBM’s success. Back in 2014 it was reported that although it has a number of large brands including Rio, Gluco, Peanut Pik and Sandwiches, it is the flagship biscuit Sooper that alone accounts for almost half of the company’s revenues – Sooper is well over the Rs10 billion mark. According to recent estimates the gross sales from Sooper biscuit alone are more than the Rs 30 billion mark now.

Within this initial success they have also continued to expand their line and look towards new kinds of biscuits as well. “We have to continue to invest in Research and Development and assess consumer needs and give them products they want. We take competition seriously,” said Dr Zeelaf Munir in an earlier interview. The daughter of EBM’s founder, Khalid Masood Butt, she currently serves as the company’s Managing Director and CEO. “We had research done, showing that the market was not growing and the consumption of biscuits was low, so a range was created to compete with our own product line,” she adds.

Continental on the other hand has focused less on plain biscuits and more on sandwiched biscuits that are perhaps not as chai-friendly as the products produced by EBM. However Continental has managed to carve out a significant

Rs 43.25 billion

market for itself with a 27.2% share in the Rs 159 billion pie with gross sales worth nearly Rs 43 billion. The interesting thing about Continental Biscuits is that it is actually an affiliated company of Mondelez International and thus this part of the biscuit pie is also Modelez’s share in the

biscuits market. Mondelez is actually a relatively new player in Pakistan’s candy and sweets industry.

The company first entered Pakistan in 1993 under the name of Cadbury Pakistan. Its largest-selling and iconic brands in Pakistan include Cadbury Dairy Milk, Tang and Cadbury Eclairs. The company employs more than 200 people in Pakistan, with manufacturing facilities in Hub, Balochistan, and a distribution network throughout the country. Continental biscuits Limited (CBL) was founded in 1984 by Mr. Hasan Ali Khan. It is now a joint venture with Mondelez International with a shareholding of 50.5% and 49.5% respectively.

This is what we know up until now. The sugary snacks segment in Pakistan is worth more than Rs 250 billion and the biggest component in this are biscuits

which have a market of around Rs 159 billion. Within this biscuit segment EBM is the leader with gross sales of Rs 81 billion and Continental Biscuits, which is majority owned by Mondelez Pakistan, has sales worth over Rs 43 billion. But a quick glance at the market share breakdown will tell you that there is one more major player in the running.

Ismail Industries comes in at third place on the biscuits market with a 15% share made up of gross sales worth Rs 23.85 billion. This is a little over half of the gross sales made by Continental which is in turn just over half of the total sales that EBM makes. But as we’ve discussed earlier, the reasons behind EBM’s success has been their ability to create biscuits that sell with chai. The fascinating thing about Ismail Industries’ involvement in the biscuit market is that they have done it through a product that is not really a biscuit.

According to the Euromonitor report we have used for this story, Peek Freans is the most sold biscuit brand in Pakistan. And while Continental Biscuits comes in second in terms of gross sales of biscuits, the second most bought brand of biscuits in Pakistan is actually Bisconni. This is owned and operated by Ismail Industries which also runs the famous Candyland brand. Now, Bisconni and Ismail Industries do not have many famous biscuits. Bisconni Chocolato is a chocolate flavoured biscuit that has done well and Bisconi’s Chocolate Chip Cookies have a similar story. But according to Ismail Industries’ own estimations, the biggest seller under the Bisconni brand name is Cocomo.

Cocomo really is a bit of a cultural icon.

The small, chocolate filled, round treat is a favourite in school canteens and corner stores around the country. There are passionate debaters on social media that engage in Cocomo discourse and for the few months that Miftah Ismail was finance minister he was asked about Cocomo by almost every single person that interviewed him. In fact, Miftah was regularly hounded about the fact that a Rs 5 pack of Cocomo now contains only three cocomos in it — a matter many interviewers asked the former finance minister about to display the concept of shrinkflation.

{Note: During the course of his ministry, Profit interviewed Miftah Ismail on multiple occasions. Although questions regarding Cocomo were never officially asked, the matter was discussed off the record more than a few times. Mr Ismail was always kind enough to bear with the badgering.}

What is impressive about Ismail Industries being in third place in the biscuits segment is that they did so with a product that barely fits in the biscuit category. This points towards the wild popularity of Cocomo and Ismail Industries’ ability to understand what the consumers want. After all, the company has had a rich history of success in the sweet snacks industry particularly when it comes to candy.

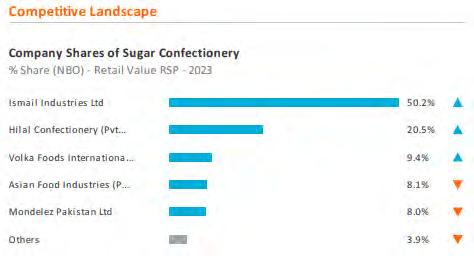

Founded in 1988, the company’s flagship brand has been Candyland. Underneath this the Ismails have remained market leaders in the sugar confectionery segment. In fact, according to a recent report, the most consumed sugary snack in Pakistan is Candyland’s Chilli Milli. They control more than half of the Rs 56.7 billion market that exists in Pakistan. The competition in this segment is not particularly tough. Hilal is

number two with less than half of the gross sales total as Ismail and Mitchells has continued to see its fortunes dip. But within the sugar confectionery sector there is one other player that is small in terms of market share but big in stature.

Coming in at number five with an 8% share of the market is Mondelez. While they only made gross sales worth Rs 4.5 billion in this segment last year off products such as Trident gum and Halls lozenges, it is clearly a space in which Mondelez has decided to stick their foot and keep the possibility of growth open. While their primary business is very much in chocolate, Mondelez has a significant stake in the massive biscuits markets thanks to their ownership of Continental Biscuits and is trying to keep the door open on the sugar confectionery market.

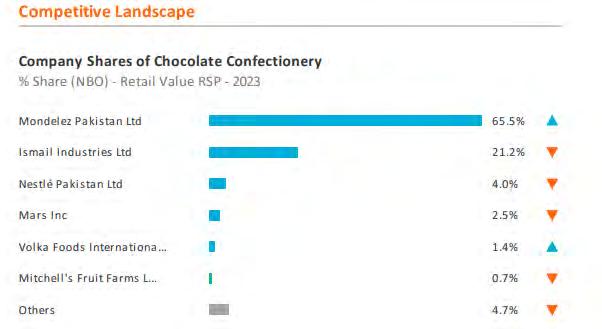

Chocolate is where Mondelez really takes the competition to the cleaners. In the world of chocolate Cadbury is King and Mondelez owns Cadbury. In Pakistan, the total sale of chocolates last year was worth Rs 35.2 billion. This is the smallest segment within the sugar snacks market in Pakistan.

But within this segment, Mondelez has everyone beat and controls over two thirds of the market with gross sales of nearly Rs 23 billion just last year. Within this, the top three most consumed chocolates in Pakistan are all Mondelez products. Cadbury Dairy Milk is the most popular accounting for nearly a third of all chocolate sales in the country followed by Cadbury Dairy Milk Bubbly and Cadbury Perk which both have around 14% and 13% of gross sales respectively.

The reason behind this is simply inertia. Chocolate is an indulgence purchase. Global trends have shown that most snack foods have faced declines in demand over the years as people have become more health conscious. But since chocolate has always been a guilty pleasure and an indulgence, the demand for it has remained relatively inelastic. It is also possible because Cadbury is the most affordable and accessible chocolate bar that is a foreign brand. Other chocolates like Mars, Snickers and Nestle’s KitKat are all acquired tastes and control 0.7% of the market share respectively. These chocolates mix other ingredients such as wafer, caramel, or nuts in it. Cadbury Dairy Milk on the other hand is a no fuss chocolate that is just chocolate without any added frills which is possibly why it is so firmly on top with over 32% of the market share.

While Mondelez is firmly on top in the chocolate industry, this is also another place where Ismail Industries has shown it is a mean competitor. Candyland Now is the fourth largest chocolate on the market in Pakistan after the three Cadbury flagships (Dairy Milk, Bubbly,

and Perk) and controls 6% of the overall market. In fact, Ismail Industries has a total market share of 21.2% with gross sales of Rs 7.46 billion. While this is not even close to Mondelez, it is worth pointing out that Ismail Industries has a significantly bigger market share in the chocolate industry than Mondelez does in the sugar confectionery segment. Ismail Industries has more than half the market share of sugar confectionery while Mondelez has barely 8% of that market. In chocolates, which is a smaller segment than sugar confectionery, Ismail Industries has nearly three times the market share that Mondelez does in sugar confectionery.

So what can we learn from all of this information? Essentially the biggest player in the sweet snacks market is EBM with gross sales worth Rs 81 billion. But because they are restricted only to biscuits their portfolio is not very diverse. Their sales are only this large because the biscuits segment is larger than the chocolates and sugary confectionery segments combined. At the same time, Mondelez is a competitor to be feared. They are clearly in the lead in the chocolates segment which is the smallest of the three but are also number two on the biscuits segment because of their acquisition of Continental Biscuits.

And then there is Ismail Industries. The case of this company is slightly different. They started off with Candyland in the sugary confectionery segment producing hard candies, boiled sweets, and in particular jellies. Their

products such as Chilli Milli and ABC Jelly have performed very well and they are firmly in first place in this segment. But they are also the only company of the three being discussed to be well placed in all three segments. In chocolates, they are behind only Mondelez and in biscuits they come out in third place behind EBM and the Mondelez owned Continental Biscuits. While their share of the market is small, the fact that they got a big chunk of it through a product like Cocomo speaks volumes to how popular their products are.

What is also quite impressive is the rate at which Ismail Industries has grown. In 2009 the company had made gross sales worth just over Rs 5.2 billion. According to their financials from last year the company made gross sales of over Rs 62 billion, indicating an increase of more than ten times in the last 15 years. But this growth has also been in line with the rate at which the

market has increased. What is more telling is the bigger increase in market share that has taken place in the last five years or so. You see, from 2004 to 2009 the increase in gross sales was from around Rs 1.4 billion to Rs 5.2 billion. But if you see the financials since 2017, the increase in gross sales has been from Rs 24 billion to Rs 62 billion. While this is a smaller percentage increase in the past five years compared to the increase from 2004-09 the increase in comparison to the size of the market is larger.

In the Pakistani market for sweet snacks the two obvious players are EBM and Mondelez. EBM carries a legacy of over six decades and has become a mainstay in Pakistani homes, offices, and cafes. Using their early mover advantage and a hyper-focus on the biscuits segment they have maintained their position as the biggest player in the market. In comparison, Mondelez was actually quite late to the party.

When they first launched as Cadbury Pakistan in 1993 they were simply entering the chocolate market and helped to expand it as well. But with international backing and a huge brand name, Cadbury was able to assert its dominance. Its acquisition of Continental Biscuits Limited soon after entering Pakistan also entrenched it as an overall player in the sugar snacks industry, not just the chocolate segment. And then there is Ismail Industries. The company that started off with Candlyland and a focus on sugary confectionery has over the years expanded its interests. It struck gold with the introduction of the Bisconni brand when they entered the biscuits segment with products like Cocomo. It has since also extended its reach into chocolates and has become the fourth largest company in the Pakistani snacks industry. Within sugary snacks, it trails only EBM and Mondelez.

What might be concerning for Mondelez and EBM is that even though Ismail Industries is a distant third, they have significant stakes in all three segments of the sugary snacks industry. With their roots firmly in place, Ismail Industries could one day threaten these two giants. n

In a move that defied expectations, the State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) Monetary Policy Committee on Thursday decided to maintain the benchmark interest rate at 22 percent.

This appeared to be quite unexpected; analysts polled by Profit as well as other publications prior to today’s meeting were majorly of the view that the SBP would hike the interest rate by 100-200 basis points (bps). After all, inflation still remains high despite declining from a record 38 percent in May. And global oil prices have been on the rise.

However, the SBP appeared to be confident that inflation would continue to decline, especially in the second half of FY24. In the monetary policy statement released after the meeting, the central bank said the impact of high oil rates was being passed on through adjustment in administered energy prices, agricultural outlook had improved, and a recent crackdown on smuggling of essential food items and illegal foreign exchange trades had “begun to yield results”.

“As such, real interest rates continue to remain in positive territory on a forward-looking basis,” it stated. In simple words, SBP expects future inflation rate to be below the 22 percent interest rate, it has decided to maintain. What exactly does this mean? Let’s say the interest rate offered by a bank on your deposited savings is 20 percent. If you kept Rs 1 lakh in that account, at the end of the year, you would have Rs 1.2 lakh. However, the annual inflation that year was 21 percent. This means that while the amount of money in your account increased, in real terms, you could buy less with that money because the cost would be Rs 121,000. This means the real interest rate was negative. If the real interest rate was positive — let’s say 23 percent — then you would have had Rs 123,000 at the end of the year.

Positive real interest rates encourage people to save and keep their money in banks as it protects them from inflation. So, raising the benchmark interest rate to a point where the real interest rate is positive means less money is going towards purchases, which decreases demand — one of the primary tools a central bank uses to curb inflation.

The SBP has raised the interest rate by

12.5 percentage points since April, mainly citing rising inflation. However, it decided to maintain the policy rate at the MPC’s last meeting in July and has stuck to its stance despite market expectations to the contrary. This means one of two things — either the SBP governor and the MPC truly believe that inflation will fall below 22 percent, or they (or whoever else influences the policy) believe there is little use in raising the policy rate as it will not control inflation. The latter view was also echoed in recent meetings of Chief of Army Staff with businessmen.

During the post-MPC analysts briefing, SBP officials asserted that inflation would decrease significantly in the second half of FY24, due in part to the high-base effect.

In response to a question, Governor Jameel Ahmad also said the MPC had factored current global oil prices as well as projections while making a decision. “One particular factor taken into account was forward-looking inflation in the next 12 months and [we] tried to keep real interest rates positive.”

This shows the SBP’s confidence. It was a “very bold decision”, according to Yousuf Saeed, head of research at Darson Securities. “Today’s decision will boost market confidence.

However, we need to keep an eye on energy prices (fuel, gas and electricity),” he commented.

While inflation may continue its downward trajectory, will it fall below 22 percent and real interest rates become positive?

“SBP believes that inflation will remain in check despite rising oil and power prices and real interest rate will be positive … We believe there is a high risk that inflation may remain higher than the SBP estimates due to rising global oil prices and adjustment in energy prices in Pakistan,” read a note by Topline Research.

Topline also revised its estimate for average annual inflation in FY24 to 23 percent from 21 percent previously. This is slightly higher than the SBP’s estimate of 20-22 percent.

Sajid Amin, deputy executive director at the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), termed the SBP’s decision “risky”, saying the central bank may have taken it based on “ad hoc” measures such as the recent crackdown which led to the rupee’s appreciation and a reduction in the prices of food items including sugar. If inflation won’t come down, then why

has the SBP not raised the interest rate? It may be because the governor and the Monetary Policy Committee believe that inflation cannot be controlled by simply hiking the interest rate.

Fahad Rauf, head of research at Ismail Iqbal Securities, commented, “I think it is a fair decision, given that there are no signs of an overheating economy, and a rate hike would have yielded little benefit in terms of curbing cost-push inflation.”

In an economy like Pakistan’s that does not work on heavy borrowing, raising the interest rate would only lead to increasing the working capital of businesses, which would then pass on the effect to consumers. This is known as cost-push inflation.

“Moreover, rate hikes would have further increased government fiscal deficit, and created a credit risk for the banking system,” Rauf added.

Independent economic analyst AAH Soomro also said the marginal utility of further hikes was negligible at best. “The market seems disappointed though. It’s clearer now that despite higher oil prices and an increase in gas and electricity prices, SBP has given clear expectations of peaking interest rates. This should comfort the borrowers – the government the most. SBP must not ruin the opportunity by letting the rupee appreciate aggressively and should increase foreign exchange reserves,” he commented.

Another view is that since Pakistan is an import-dependent economy and the SBP’s interest rate hikes cannot possibly affect global prices of oil and food etc., such increases would have no effect on ‘imported inflation’.

Of course, this is not something that the SBP governor can say out loud.

And besides, other than analysing the reason behind the SBP’s decision, another important question remains: what will the International Monetary Fund (IMF) say?

Under the $3 billion Standby Agreement, the IMF has asked for an appropriately tight monetary policy that counters inflation. If the IMF is not satisfied, the government will have to raise the interest rate similar to how it did so in an emergency meeting in June.

However, Governor Ahmed said during the briefing that the current monetary policy was tight and in line with the SBA. n

‘Unexpected’

Does the central bank really expect inflation to decline significantly or has it accepted that rate hikes aren’t effective?

Recently, there has been news regarding how many of the brokerage houses of the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) are converting into the category of ‘Trading Only Securities Broker’. What do these buzzwords mean and what does it mean for the market and investors? Profit explains.

Since the last market crash took place in 2008, there have been different lessons that have been learned by the PSX in order to better manage the risk and the assets of the clients who are active investors in the market.

To understand the crash better, read Profit’s detailed story on what led to it and its aftermath.

Two of the most important steps that have been implemented are segregation of assets and placing of securities brokers into categories. Due to these measures being implemented, it has been assured that the clients’ assets are protected from misuse and the risk associated with brokerage houses does not cause undue volatility in the market. Let’s break down both these measures further.

Let us take you back a few years on how the PSX (then Karachi Stock Exchange) used to operate in the old days. Clients or investors would go to a broker who would open a trading account for the client which was like a bank account. This account would be used to keep a record of shares and funds that the client

had invested on his own through the broker. It was a simple ledger that was kept by the broker to keep track of all the transactions that were being carried out.

As this was a time of low regulation and monitoring, many of the brokers kept the shares of the clients in their own custody account. These custody accounts are opened in and managed by the Central Depository Company (CDC).

The CDC is a company set up specifically to be a custodian of the shares of an investor or a brokerage house and has the sole responsibility to make sure shares are protected and kept with proper accounting and monitoring.

Just like a bank is a custodian of deposits of its customers, the CDC only deals in safekeeping of shares. But unlike banks, the regulatory framework at the PSX was close to non-existent at the time and brokers were able to keep the shares of the clients in the name of the brokerage house, not at the CDC, for personal use. A practice akin to stealing.

This was done while the clients were unaware of how their shares were being used and because they got no notifications from the brokers or the CDC when a movement of shares or use of funds was carried out, they were simply unaware of this daylight robbery.

As brokers were using the shares of the clients without their knowledge, this was seen as a giant breach of their fiduciary responsibility. The clients’ assets should be under the ownership and control of the clients themselves. This was not the case here.

Imagine a bank withdrawing money from the clients’ account in order to pay their expenses. Doesn’t sound right does it? The brokers were freely using the clients’ assets, both funds and shares, for their own use and when these brokers defaulted, the clients’ assets were lost as well.

The Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) and PSX made the necessary changes to laws specifically after the 2008 market crash in order to make sure clients were not disadvantaged by the brokerage houses. SECP and PSX made it mandatory for brokerage houses to ensure segregation is maintained and that all assets of the clients are separated from the operations of the business-side of the brokerage.

The SECP and PSX made sure that brokers could no longer use the clients’ assets for their own personal consumption. It was created to have a barrier to the sweet honey pot of funds that the brokers thought they could use whenever they wanted.

Brokers were kept in line through regular audits and they had to make submissions to the PSX and SECP regularly and periodically. This was the first step that was put into place to make sure the brokers were not risking the clients for their own benefit. The next step in risk management was to make sure the market was kept safe from brokers as well. This led to the categorisation of the brokers.

As the capital markets of the country have matured, measures have been taken to make sure that the client as well as the market is protected and looked after. In many of the crises of the past, the investors and the market are the ones who lost out. The SECP and PSX are constantly making sure that there is a firewall around the investors to protect them and their assets at all and any cost.

A recent step taken to solidify that firewall was to classify brokers into three separate

categories.

These categories are namely trading only, trading and self-clearing and trading and clearing. In order to understand the significance of these measures, it is important to understand what used to happen before.

When a trade is carried out at the stock exchange, it is not like a real estate or property deal. When a property deal takes place, the buyer and seller know each other and are able to exchange the property or money face to face knowing full well who all is involved in the transaction. In the stock exchange, an investor has an interaction with a computer screen interface rather than a human being. The trades are carried out between two anonymous parties.

Let’s say someone wants to buy shares from the market and is successfully able to do so during normal trading hours. The client now has to make sure that he has the required funds in his trading account to settle what he owes for the purchase of said shares. The usual settlement time in the stock exchange is ‘T+2’ or trade + 2. This means that the buyer will get the shares two days later and has to arrange for the payment in 2 days time.

Two days later, the money will be withdrawn from his account and will be deposited into the seller’s account and the shares will come into the CDC account of the buyer after they have been withdrawn from the CDC account of the seller.

But it is not as simple as that. There is a clearing house, National Clearing Company of Pakistan Limited, that is in the middle of this transaction that clears these trades and facilitates the transfer of funds from one account to another. It is an autonomous body which has been set up for facilitating trades. It has been created separately as they have access to the trading being carried out and that kit needs to be kept confidential.

The role of the clearing house is to sit in the middle of each and every transaction and make sure there are funds and shares that can be cleared or transferred from one account to another in a seamless manner. In such a case, both parties are showing that they can honour their respective commitments and the trade will be carried out.

In case this does not happen, and let’s say the buyer of shares is unable to come up with the required cash in the T + 2 settlement time; the NCCPL reprimands that side while the

one that follows through on its commitment has their trade take place. Usually, trades go through most of the time so NCCPL is able to do its job efficiently.

The role of NCCPL is important as it is able to facilitate the task of clearing or being the middleman who is responsible for clearing thousands of trades on a daily basis.

In order to make sure the brokers are able to carry out trade, the NCCPL keeps a certain amount of exposure.

This exposure is like a collateral or a fund that allows brokers to trade up to a limit. Just like collateral can be used in case of default, NCCPL can use this exposure to recoup some of the losses which take place. This can be in the form of shares or cash. Once that limit is crossed, the broker cannot trade any further. This is a fail safe mechanism that makes sure no broker is trading quantities in the market larger than it can back with capital.

It acts as a tool of risk management to ascertain the buying or selling capacity of a broker. The higher the exposure, the more their capacity to trade large quantities and clear these trades by themselves.

In order to protect the stock market from shocks created by individual brokers, the exposure limit is a mechanism that makes sure brokers are not carrying out large sized trading in their accounts. In the past, the assets of the broker were the threshold but now PSX has mandated for brokers to be broken up into three categories depending on the size of their balance sheets.

This has been done by the PSX to ensure that small brokers do not hold clients’ assets for which they do not have the necessary capital to back those assets up. If they default, the PSX wants to protect the clients and their hard earned earnings.

Trading only is the first category which means a broker can trade for themselves and carry out trades for their clients, however, they cannot clear these trades in the market. In order to facilitate the trading, there is a professional clearing member (PCM) whose task is to clear the trades for these small brokers. As a simple example, imagine the PCM as being the bouncer at the door for the small broker. The PCM makes sure that trades are only carried out when the broker and their clients have the necessary funds or shares to honour the trade.

Small brokers do not have a large amount of capital on their books and have small balance sheets. As they have a small capacity of funds, they cannot hold their own shares or the shares or the funds of his own clients as well. If the broker defaults or wants to exit the PSX, the clients’ assets are stuck in a legal limbo . Under

the new system, as the PCM keeps custody of the shares of the clients, the assets are protected.