08

08 A Year of Surging Trends for the Banking sector

14 TERF wars 20

20 How much ‘more than a bank’ can a bank be?

23 Startup failures in Pakistan and the role of founders Ovais Zaidi

26

26 No Man’s Land — How Islamabad’s Katchi Abadis came to be

29 How Pakistani corporates can maximize their CSR impact: The Engro example

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Mariam Umar

By Mariam Umar

In the middle of a tumultuous year for the economy and a highly unstable socio-political environment, Pakistan’s banking sector managed to have a year of relative financial stability in 2022. In a new report the PWC has reported that most benchmarks have signified a sustainable year.

On the balance sheet side, both assets and liabilities grew moderately. Profitability also increased by more than 20%. We will look at each of these indicators in detail. But there were also very particular anomalies and unique trends in the banking sector’s 2022 performance. So what were the findings of the report and what are the future challenges and opportunities that need to be navigated?

On the liabilities side, deposits have recorded steady accretion over the last five years. In 2022 there was a modest rise of 8% which is the smallest increase in the last five years. In the preceding

years, the increase in deposits had been in double digits. The small increase can be attributed to the Advance to Deposit ratio (ADR) tax that was levied on the banking sector. Banks were supposed to maintain an ADR of at least 50%, failing to do so would result in higher taxes.

Theoretically, there were two ways through which the banks could improve this ratio: by either increasing advances (loans to the private sector) or decreasing deposits. Hence for the first time in the last twenty-one years (prior data is not available), in the

Despite its challenges and shortcomings, the banking sector remained financially stable

last month of a financial year, banks opted to decrease their deposits. This also marks a break from the traditional pattern where banks would artificially hold onto deposits to meet performance goals and inflate their deposits in December, only to release them in January was a first.

This is also evident from the graph below where deposits increased by only 8% in 2022.

The customer deposit mix remained broadly consistent, with low-cost deposits i.e. current account deposits and saving deposits accounting for 78% of total deposits. Current account made up for majority of deposits at 41%.

Advances are loans extended to the private sector. Advances (loans) exhibited year-on-year growth of a whopping 16% in 2022.

For the past five years, there has been a consistent trend in the allocation of loans, with approximately 70% of them consistently directed towards corporates. The financing type for corporates is as follows:

Banks seem to be tactfully handling their exposure by being cautious with loan financing in fixed investment, which exhibits a higher Non-Performing Loan (NPL) ratio of 9.2% as concentration of loans for fixed investment has decreased by 200 basis point. On

the other hand, it appears that trade finance is constrained, possibly as a response to the import restrictions imposed in the latter part of 2022. However, in response to changing circumstances, there has been a noticeable shift in funding towards working capital, which carries a relatively lower NPL ratio of 7.4% as the concentration of loans for working capital has increased by 300 basis points.

The credit portfolio of the banks is predominantly allocated to a select group of industries, which together make up more than 50% of the portfolio. These key industries include textile, energy production and transmission, individual borrowers, agri-business, and financial services.

The allocation of loans to priority segments, namely Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) and Agriculture, has been relatively low, accounting for less than 8% of the total loans. Specifically, SME loans constitute 4.2% of the portfolio, while Agriculture loans account for 3.6%. Moreover, these penetration levels have been witnessing a decline over the past several years. This declining trend highlights the need for attention and support to bolster lending in these crucial sectors to foster their growth and development.

The state of SME credit intervention in Pakistan, when compared to certain regional

economies, is disheartening, presenting a significant untapped opportunity. A mere 4.2% of loans have been directed towards SMEs in Pakistan, making it the lowest among its regional counterparts. This concerning situation has seen a gradual decline since 2007, attributed to

various factors.

Among the primary reasons for this contraction are the historical experiences with Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) that have influenced risk perceptions, as well as limited credit appetite and capabilities. Additionally, the

lack of access to reliable and credible data has hindered effective decision-making in lending to SMEs.

Nevertheless, there are promising examples in the industry where innovative approaches have led to successful service of SME and agri segments. Niche business models, tailored risk assessments, skilled workforce, and advanced technology integration have proven effective in catering to the needs of these segments. Recently, the emergence of collaborations with fintech and agritech companies has also contributed to improved access and support for SMEs and the agricultural sector. These partnerships leverage technology to bridge the gap and address the challenges faced by SMEs and agri-businesses, potentially paving the way for their growth and prosperity.

In the current precarious economic climate, where credit risks may be heightened owing to ever-increasing policy rate which increases costs for businesses and other business costs, banks would have to improvise their credit appetite and readiness to lend to such segments and work on real capacity augmentation for effective penetration.

To improve lending to SMEs and agri-businesses, some major enablement support is required to create the right ecosystem in relation to SME and agri lending.

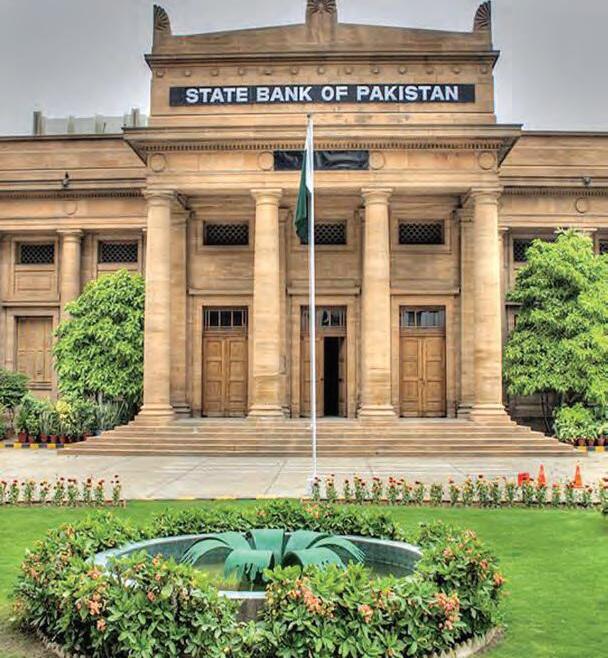

Mr. Salim Raza, Former Governor State Bank of Pakistan has expressed his insights on the subject “In Brazil, China, India, Turkey and other major emerging jurisdictions, development finance is also fueled by public sector development banks. For example, in India there is a separate institution for SMEs and another one for agriculture. Our development banks are very small with next to zero contribution. To rejuvenate priority segments, we need to have a fully functional Planning Commission and a priority-sector led industrial policy with clear objectives for next 3-5 years, vitalisation of special enterprise zones and specialised banks to deal with SME and Agri,” he says.

“Another key imperative is to support data enabled credits/ digital credits. For this, a national level collaborative effort has to be

In Brazil, China, India, Turkey and other major emerging jurisdictions, development finance is also fueled by public sector development banks. For example, in India there is a separate institution for SMEs and another one for agriculture. Our development banks are very small with next to zero contribution

Salim Raza, former SBP governor

put in place for big data/ registry, with the intervention of Government, regulators, banking and all industry stakeholders who can enable/ contribute alternate data for optimum credit bureau infrastructure.”

Consumer finance posted a modest growth of 9%. It accounted for 7.1% of total advances which is a slight decrease as compared to the preceding year figure in 2021. Notably, mortgage finance witnessed remarkable traction, soaring by approximately 50% during the year. Additionally, the credit cards portfolio experienced a significant boost of 32%. However, auto loans experienced a contraction, declining by 5% during the same period.

The lending to the private sector in Pakistan, amounting to 15% of GDP, is notably lower when compared to certain other jurisdictions. As previously discussed, adopting a more inclusive credit strategy targeted towards priority sectors and segments could play a pivotal role in elevating this crucial benchmark to a more reasonable level in the medium to long term. By strategically focusing on priority areas, such as SMEs and agriculture, and implementing supportive policies and measures, the potential for a substantial increase in lending to the private sector becomes feasible. This not only fosters economic growth but also enhances financial inclusivity and stability, ultimately contributing to the nation’s overall prosperity.

“With Pakistan’s private sector credit to GDP ratio of 15% (as of Dec-20) and ADR at 50% (as of Dec-22), its positioning relative to certain emerging economies reflects large untapped potential to scale development finance.” explains Salim Raza

It is a sentiment echoed by others. According to Muhammad Aurangzeb, Presi-

A deeper sector understanding is required to penetrate the SME and agriculture space. Banks have historically been inclined to a collateral based lending model. This approach warrants a complete transformation towards more interactive, cash flow based lending to better serve these sectors

Muhammad Aurangzeb, President and CEO of HBLYousaf Hussain, President and CEO of Faysal Bank

dent and CEO of HBL, as a front-runner the banking sector has to rethink and revamp business models. “A deeper sector understanding is required to penetrate the SME and agriculture space. Banks have historically been inclined to a collateral based lending model. This approach warrants a complete transformation towards more interactive, cash flow based lending to better serve these sectors,” he says.

The enhanced performance in managing Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) indicates that banks have adeptly navigated the current challenges by exercising cautious financing on a limited scale. However, it’s important to note that credit allocation to vulnerable sectors remains minimal.

“The prevailing economic situation in the country suggests that while banks may be inclined towards lending and expanding their balance sheets, an initiative incentivised by support from SBP, they may be confronted with the challenge of NPLs over the next couple of years,” commented Mr Yousaf Hussain,

Investments usually refer to investments in government securities like Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIBs) and Treasury bills (T-bills). Investments surged by 25% with ~90% concentration in government securities. Investments in government securities offer risk-free returns which incentivises banks to place funds, resulting in a lower ADR. Another reason for the high IDR is the government’s reliance on domestic debt.

Consequently, Investments to Deposits Ratio (IDR) has been rising. IDR in Pakistan is the highest as compared to other regional countries like Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India. According to the recent data released by the State Bank of Pakistan, as of June 2023, IDR stands at 82%. On the other hand, ADR has been decreasing consistently. ADR decreased from 70+% in 2007 to 50% in 2022. According to the recent data released by the State Bank of Pakistan, as of June 2023, ADR stands at 48%.

Borrowing increased dramatically in 2022, an increase of 1100 basis points. A striking upward trend in borrowings has been observed, particularly evident in the last two years. Notably, there has been a remarkable exponential increase of 63%, amounting to Rs. 7.5 trillion, compared to Rs. 4.6 trillion as of December 2021. These borrowings were most probably to finance investments in government securities.

Profitability, Return on Asset (RoA), and Return on Equity (RoE) amplified sharply on the back of higher spreads and non-funded income from different avenues. However, it is worth noting that the TEXTILES

The prevailing economic situation in the country suggests that while banks may be inclined towards lending and expanding their balance sheets, an initiative incentivised by support from SBP, they may be confronted with the challenge of NPLs over the next couple of years

positive trajectory of baseline profitability was somewhat dampened by tax charges. These tax implications had a disproportionate impact, moderating the overall profitability growth, despite the other favourable factors contributing to the amplified financial performance.

As the following graph shows, profit before tax increased from Rs 451 billion in 2021 to Rs 696 billion in 2022, an increase of more than 50%. However profit after tax in 2022 was only Rs 331 billion, which is approximately 50% of the profit before tax figure. This means that banks paid almost 50% of their profits in taxes.

For FY22, tax rates were raised from 35% to 45% (effective tax rates jumped to 49% from 39% in 2021). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, an additional tax on income from federal government securities, linked with ADR was also introduced which increased the tax burden on the banking sector. Nevertheless, the sector was still able to maintain its profitability.

Mark-up income is the interest based income. It is the core income for the banking sector. Mark-up income increased considerably to Rs 3.4 trillion, at the back of rising policy rates. Below provides a comparison of mark-up income from advances and investments, along with SBP policy rate and one-year KIBOR as of Dec-22 vs. Dec-21.

Policy rate further increased to 21% in April 2023, in the backdrop of economic uncertainties and rising inflation, generating a cumulative impact of 1,400 basis points since June 2021.

The policy rate in Pakistan as of Dec-22 is much higher relative to certain other economies, even higher than that of Sri Lanka. This resulted in improved earnings for the banking sector.

Operating expenses registered an increase of 25% in 2022, which is the highest increase as compared to relatively lower variations during the last few years. However, with a strong revenue base (75% growth in mark-up income), the industry’s cost-to-income ratio improved to 48% compared to 53% in Dec-21.

The banking sector in 2022 demonstrated remarkable resilience and growth. Despite taxation challenges, the sector’s adaptability and strategic focus on key areas are key drivers of its continued success. n

It started quite inconspicuously. At a regular meeting of parliament’s Public Accounts Committee (PAC), the committee’s chair called for a probe into a unique facility that the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) had provided back in 2020.

Within days the term TERF — which stands for Temporary Economic Relief Facility — was on everyone’s mind. Camps were set up, battle plans were readied, and lines were drawn.

On one side are the architects of the scheme like former State Bank Governor Raza Baqir and former finance minister Shaukat Tarin. They are joined by industrialists, large investors and others who feel the facility achieved many of the objectives it had been created for. On the other side are critics who feel the facility was dead on arrival and it ended up being just another scheme where industrialists got to enrich themselves with free money.

The reality is that the investigation initiated by the PAC was little more than a political witch hunt. The Noor Alam Khan led committee was more interested in sniffing around and trying to dig up some dirt on the financial team that was running the show during the Pakistan Tehreek i Insaaf government and the TERF scheme seemed to be a good place to start.

But to understand entirely what the entire fuss was about, it is important to understand what TERF was. Launched in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, it was essentially a facility launched by the SBP with the help of the government that provided nearly interest free loans to businesses so they could keep the wheels turning and not lay off their employees. Over time, more than 600 businesses took advantage of this facility and the SBP lent over $3 billion for this purpose. Major businesses took them up on this offer, including giants such as Interloop, Nishat, the Lucky Group, Ismail Industries, and many others.

The question here is not whether there was something shady going on with TERF as the PAC has tried to claim (hint: there isn’t). The real question is that outside all the mud slinging and shrieking about corruption, how was the TERF scheme on merit as an attempt to keep businesses afloat and unemployment low?

Profit investigates.

Let us start at the beginning. In 2020 the economy was tanking. The Covid-19 pandemic had hit Pakistan and the rest of the world and halted most businesses. According to a report, “Special Survey for Evaluating Socioeconomic Impact of

COVID-19 on Wellbeing of People”, the labour market of Pakistan dropped by 13 percent in the April–June quarter of 2020.

According to the Economic Survey 202021, prior to Covid-19, the working population was 55.7 million. During the pandemic, this number declined to 35.04 million which indicates that 20.71 million people either lost their

jobs or were not able to work.

With falling demand some businesses found themselves reeling worse than others. Retailers were closed down, malls barred their doors, and demand was in the dumps. The government was facing an unprecedented crisis in which people were losing out on jobs as well as on business. This is where TERF was introduced. This was a facility provided by SBP in order to promote investment and expansion of industrial capacity of the country.

The time this facility was introduced, the pandemic was ravaging the world with lockdowns being announced on a daily basis. It was feared that the pandemic would slow down economic growth and a facility was provided by the SBP to SMEs and industries to borrow at low interest rates. In a time where economic uncertainty was high, no one would be willing to invest and the scheme was a way to incentivize investment.

The mechanism which had been used by the SBP was to allow banks and DFIs to carry out financing across all sectors. The banks had the ability to carry out their own due diligence and scrutinise the companies themselves before granting a loan under this facility. The facility was to be used to either purchase imported or locally manufactured plants in order to complement existing projects or set up new projects from scratch. Later the scope of the loan was also expanded to include Balancing, Monitoring and Replacement (BMR) to be carried out.

These funds could be used to finance all Letter of Credit that had been established after the announcement of the scheme from March 17 till March 31, 2021. Banks were allowed to give a loan of Rs. 5 billion per project and the rate that would be charged was 7% a year which was later reduced to 5%. The SBP charged a refinance rate of 1% while the remaining 4% was charged by the banks as the spread above the refinancing rate. The period of the loan was set to be 10 years with a grace period of two years.

According to SBP’s own record, it can be seen that the bank has a record of 626 borrowers still left in its books with Rs. 398 billion disbursed and Rs. 19 billion already repaid. The program has seen an increase in employment by nearly 200,000 workers directly and it is expected that the program will see export potential increase by $12 billion and import substitution by $3.5 billion.

One of the pertinent questions that needs to be asked at this stage is where does the $3 billion come in. The loans that had been given out

to the investors were worth Rs. 436 billion according to the records of SBP at the end of Mar 2021 when the facility was supposed to expire. Mr. Chairman Noor Alam Khan seems to be considering the dollar against Pak Rupee as it stood at March end 2021 which would make this figure true to a certain extent that loans of $3 billion were granted.

The problem with the figure is that it is being presented as an amount that has been given away by the government. The $3 billion amount has been portrayed and amplified as being the loss that the government made while the industrialists were able to use this facility to get away with these funds. That is not true. These are loans and these loans have to be paid back by the companies when they mature in 2032 or even before that. Once these loans are paid back, the $3 billion would be returned and interest of 1% would be earned back by the SBP.

Granted the State Bank will be making a loss compared to earning a higher interest rate and that criticism has its merit but the goal of these loans was to boost investment. To state that these funds have been wasted or handed out is a blatant lie. The goal of the statement was to parade around the $3 billion figure as a loss to the country and create a ripple in the political discourse of the country which it has sadly done.The PAC was going to go on vacation in mid July and the government would be ending its tenure in mid August which would have made this probe futile in itself. This all was known well in advance and the PAC was able to create a political storm in a teacup.

This issue might have a political motive behind it but the question still needs to be asked who is actually paying the cost and what the cost is. The scheme was introduced in March of 2020 and interest rates had fallen from 12.5% to 7% within 3 months by June of 2020. The government had initially given these loans at 7% but seeing the base interest rates fall, the rates were revised to 5%. As the refinance rate was 1%, banks that had given the loans were able to earn a spread of 4% with these loans.

The initial model seemed sound enough as the interest rates remained steady for more than a year when they were increased by 25 basis points in September 2021. The rates have significantly ramped up since then and stand at 22% in June 2023. There are borrowers who were able to use the facility and are paying a measly 5% interest on these loans while the rest are borrowing at 22% and higher. The banks are still earning their spread on a principal that they did not have to put up and it is free money for them as well.

These loans are being refinanced by the SBP and the central bank was able to fund these loans through money supply. The central bank has the power to print money and using this ability, they have been able to make these loans. Based on this, it is evident that SBP and ultimately the people of the country are the ones bearing the cost of TERF. At the time when funds were being allocated to create such a loan, SBP had little concern for inflation and printed the money to stimulate the economy.

Due to the act of printing money, the economy would have gone through inflationary pressures which have cost the people in the end. One of the contributing factors for the interest rates to be at 22% was the fact that large scale borrowing was carried out at low rates and there should have been some foresight by the SBP to make sure that the inflation that once inflation started to become a concern, there were measures in place to counteract it. The real cost of this program resulted in inflation in the economy and that cost has mainly been ignored in the debate that has been carried out around this issue.

The people who support the scheme state that the goal of the facility was to allow businesses to carry out their investment plans without any delays. Raza Baqir, the Governor of SBP during the pandemic, has stated that the SBP was under pressure from the business community to lower the interest rates and TERF was seen as a welcome relief to the worrying industrialists. “Ultimately, the institution won the hearts of many industrialists and businesses,” he said.

The loans were initially for green field and expansion related projects which were later tweaked for BMR projects as well. Proponents of the scheme state that the project was a success as the country was able to expand exports and create new job opportunities which might have seen unemployment and loss in economic output if the facility was not present.

Overall, the scheme is seen as being positive for the country and a much needed boost to the investment. It led to generation of tax revenue which would not have been possible without the program. The design of the scheme was to give the banks the authority to carry out the due diligence and assess the creditworthiness of the businesses which meant that SBP was not involved making the process fair and equitable to every business.

The SBP made sure the loans were to be provided to SMEs and businesses alike as the program was supposed to be sector agnostic. It was felt at that time that carrying out extensive imports of machinery would

What they got and what they spent it on:

The major textile player used a facility of around Rs. 1.5 billion TERF and Rs. 47 million as ITERF (Islamic TERF). The company used it to establish a Hosiery Division number 5 and Fabric Dye House with expansion in its Spinning Unit. It took the money from the Bank of Punjab and National Bank of Pakistan. A similar arrangement was made under ITERF secured with MCB for additional capex requirements to be met.

What it did to employment:

From 2020 to 2021, the number of employees increased from 20,000 to 22,789 and has grown to further 29,524 by the end of 2022. The TERF facility was further utilized by the company with an additional loan being taken in FY 2021-22 as the total facility being utilized went to Rs. 2.7 billion with different banks.

Other schemes:

It has to be noted that the company was already using the LTFF facility given to exporters by the SBP and SBP renewable energy facility as well. Based on the investment made, the company made an EPS of Rs. 2 for 2020 which grew to Rs. 7 for 2021 and to Rs. 13.76 for 2022. The company did see its exports grow from Rs. 33 billion in FY 2020 to Rs. 50 billion in FY 2021 and FY 2022 saw exports grow further to Rs. 84 billion which shows that the TERF facility was successful for Interloop.

What they got and what they spent it on:

Nishat Mills used the TERF facility by asking for Rs. 761 from Bank Alfalah, Rs. 843 million from Habib Metropolitan Bank and and Rs. 1.86 billion from United Bank Limited bringing the total of TERF facility being used to around Rs. 3.3 billion. These were used for the establishment of an open end yarn unit and a project of 130 wider width looms to increase production capacity.

Based on the facility, the company saw its number of employees increase from 18,558 to 22,935 from 2020 to 2022. The company used this facility further in FY 2022 where it increased its utilization to Rs. 4.8 billion.

Other schemes:

The company was also utilizing the SBP schemes under LTFF for exports and renewable energy facilities. Based on the investments made, it was seen that the company saw its EPS go from Rs. 10 in 2020 to Rs. 16.84 in 2021 and Rs. 29.33 in 2022. In terms of exports, the company

saw export sales at Rs. 45 billion in 2020 to Rs. 46 billion in 2021 and Rs. 75 billion in 2022.

The company entered into ITERF and TERF agreement with Habib Bank Limited - Islamic, MCB Islamic Bank Limited, Bank Alfalah - Islamic, Faysal Bank Limited - Islamic, Habib Metropolitan BankIslamic, United Bank Limited - Islamic and National Bank of Pakistan under the Temporary Economic Refinance Facility (TERF) by the State Bank of Pakistan. Loans taken amounted to around Rs. 2.6 billion with different banks. The company was also able to get additional facilities under LTFF for exports and for renewable energy facility of SBP. These facilities were used for expansion and establishment of projects by the company.

What it did to employment:

By FY 2022, the company had expanded the use of the facility to around Rs. 4.9 billion. Lucky Cement did not see a huge change in the number of its employees as the company saw its number of employees go from 2,523 in 2020 to 2,542 by 2022. In terms of the EPS, the company earned Rs. 10 in 2020 to Rs. 43.5 in 2021 and Rs. 47 in 2022. In terms of exports, the company saw exports of Rs. 12.3 billion in 2020 to Rs. 13.9 billion in 2021 and Rs. 10.4 billion in 2022.

What they got and what they spent it on:

Ismail Industries used this facility with Rs. 242 million from Habib Bank Limited, Rs. 21 million with MCB, Rs. 199 million and Rs. 131 million with Habib Metropolitan and Bank of Punjab respectively. In addition to that, Rs. 442 million from National Bank of Pakistan as TERF and Rs. 43 million under ITERF from MCB Islamic Bank. This brings the total of the facility to around Rs. 1.1 billion. The facility was further increased to a total of Rs. 3.9 billion in 2022. Ismail Industries also utilized the LTFF and renewable energy facility given by SBP in conjunction with the TERF facility.

What it did to employment:

In terms of employment, the company had 2,525 employees in 2020 and had 2,718 by 2022. The company saw its EPS go from Rs. 14.5 in 2020 to Rs. 26.7 in 2021 and Rs. 38.4 by 2022. Initially, the exports of Ismail Industries stood at Rs. 4.5 billion in 2020 which increased to Rs. 6.7 billion in 2021 and Rs. 15.1 billion in 2022.

have put undue burden on the import bill of the country but once the economy rebounds, it was felt that it will be on the back of these TERF funded investments which will enhance the long term growth of the country. They defend the fact that most of the borrowing was carried out by the textile sector as the industry forms the backbone of the country and would carry out export-led growth for the country in the long run.

The textile industry benefited most from the program as they were able to expand and upgrade their plants and export to new markets. Supporters of the program do admit that there were inefficiencies in terms of placing and monitoring limits on the borrowing and

keeping them sector relevant.

The detractors of the scheme feel that the program was lopsided and that it primarily failed to achieve the goals it had set out itself. They highlight the fact that most of the loans that were provided under this facility were given to industrialists at the expense of SMEs. This was an inherent flaw in the design of the facility that was provided by the SBP they claim.

The decision making ability to provide the loans was given to the banks themselves

after their due diligence was satisfied which meant that the banks would favour established and running businesses over SMEs who had little track record or collateral against the loan they were able to get. The industries which attained most of the funds were textile, sugar, chemical and automobile sector just to name a few which shows that these loans were extended to established industries. The goal of this program was to benefit businesses of all shapes, sizes and industries, however, banks are always going to prioritise loans to bigger established companies. This flaw became apparent as banks were not mandated to follow any sector or size related financing and were given free reign for the decision making

process.

Only 7% of the facility was utilised by non-manufacturing industries which amount to around Rs. 10 billion while 45% of the funding went to some form of textile related industry. There are also concerns raised over the fact that SBP had the final right of approval of all the loans granted by the banks and that SBP could have been more vigilant when approving these loans which they failed to do. There are also claims of preference in regards to certain business groups which benefited the most from these loans and SBP could have made sure that this did not happen where business groups were able to crowd out most of the funding for themselves.

The SBP also mandated that these companies did not carry out any downsizing or firing of staff after they took these loans which was not followed through either which shows that the state bank was not looking to implement the rules it had set out itself. There could also have been a system where these business groups or companies could have been taxed higher in later years in order to offset some of the benefits they would have gotten due to the lower rates of interest that was levied on them which was not put into place either.

Another aspect that has been criticised is the fact that many companies looked to finance their long term projects with these low rates loans and the benefits of which will accrue years into the future.The goal of the facility was to allow for industries and small enterprises to carry out investments without any delay and these projects had to be executed in the short term. The SBP did not place any temporal limitations which meant companies could carry out large scale investment in projects which would take years to complete before providing any economic benefit. As these loans were at low rates and rates were not going to be revised upwards, they could bear the miniscule costs these projects were worth and could take advantage of output in the future.

Critics have said that the SBP allowed companies to carry out capital expenditures at low rates, however, operating expenditure financing that is needed by the companies has to be funded by higher rates prevailing in the economy. They state that once the production capacity was increased, there was a need for similar financing to operate the business and use this capacity which was not provided for. This claim can be shot down by the fact that the central bank did

mandate the PFIs to “ensure that the working capital facilities in respect of the new project are adequately secured/agreed to, preferably by a financing PFI or one of the member of the consortium, prior to the approval of financing under the facility, so that project does not suffer due to lack of working capital facilities in future.”

The central bank did put into place certain checks which would have meant that operating expenditure of the future could also be met once the capital expenditure had been carried out. Again, mandating PFIs to make sure this financing was available and was carried out at a long term low rate could have been put into place and made sure TERF was successful in the long run. The fact remained that the interest rates grew to 22% which was not foreseen by anyone and once the rates did get so high, there was a lack of liquidity of funds. This led to an increase in capacity of the business which could not be utilised properly. Rather than something that could have been a feather in the cap of SBP, this ended up being a burden with financing being crowded out and the potential benefits of the scheme not being realised fully. However, the SBP did put in measures to make sure operating expenditure was provided for.

One of the biggest plus points of a scheme like TERF was the fact that it was a long term loan which does not exist in a country like Pakistan. From the government to the private sector, there is little to no scope of a medium term debt or borrowing market where borrowers can borrow for a substantially long time without risk or revision or changes. From the T-Bill market to the unmatured bond and sukuk market, no bank or institution is willing to commit funds for a long term of time. TERF changed this scenario. It was the first time that a loan was being given for a period of 10 years with a grace period of 2 years. This was a game changer for a country like Pakistan where stability is scarce and needed in order to bring some modicum of certainty in the business environment of the country. This was a good aspect that needs to be kept in mind when future facilities or programs are designed.

One huge criticism of the program was the fact that big industrialists and groups had taken over the scheme by procuring most of the loans. This is something that needs to be looked into and SBP needs to develop sector and business related restrictions to make sure that certain elements of the business community do not end up taking advantage of the facility. Banks supplied TERF related financing to the same companies multiple times which benefited only a few groups. The SBP was re-

sponsible for refinancing the loans and should have done more in order to make sure the spirit of the facility was honoured. Banks, when given a choice to lend to an established business and SME, will always lend to an established business and SBP should have enforced its own rules and regulations in a better manner to make sure the facility was open to a larger group of people and businesses. The SBP could have asked the banks to apportion a certain amount of loans to SMEs in order to balance the risk of lending to industrialists and that could have been implemented more stringently which did not take place.

Another tweak that could have been made would have been to peg the interest rates of the TERF program to the interest rates prevailing in the market. They could have been set at KIBOR minus a certain percentage which would have meant that once the interest rates would have increased, the interest on these loans would have changed as well which would have lessened the losses on the central bank. SBP provided liquidity in the market by handing out these loans at lower rates and printed money. This ultimately means that the cost of the project could be seen in terms of inflation that was suffered by the country and that cost needs to be weighed when the benefits of the program are counted out. By pegging the interest rates, the bank could have recouped some of its cost and would have been acceptable by industries as well.

The SBP has the power and the authority to investigate the abuses that are being highlighted by the critics and it would have retained the secrecy of the clients with the matter staying between the banks, the central bank and the borrower. Any misuse of the funds can also be recouped from the banks accordingly even if the borrower does not release the funds and this is something that should be looked into to quell the feeling of unfairness that exists in the minds of the critics of TERF. An institution like the SBP should look to investigate claims of abuse and misuse and carry out investigations of these claims in order to alleviate the sense of unfairness that exists around these loans. This is an opportunity for the SBP to save some face for itself and look to investigate the blatant abuses of funds that have been carried out. This would help alleviate the feeling of gouging and helplessness that the people feel and will bring some perception of fairness and shed light on the success of the program itself. The businesses and industries which took money from the government need to be held accountable and even punished. n

How much can one organisation do for the greater good?

It really depends on the organisation.

Take HBL for example.

As Pakistan’s largest bank HBL is in a position of power where they can

have a real world impact on Pakistan’s economy and its people. Recently announced as one of three Domestically Systemically Important Banks (D-SIB), HBL is large enough that when it moves thousands of lives move with it.

At an event in Karachi to mark the launch of HBL’s Impact and Sustainability report for the year 2022, HBL’s senior leadership including its President and CEO spoke freely

to the small gathering of bankers, clients, and journalists at the bank’s main offices at Clifton. The topic was what HBL had done and more importantly how the bank imagined itself.

In the report, HBL proudly displayed how they had directly spent over Rs 4 billion over the past decade for the social uplift of Pakistan along with detailing their many internal and external actions and interventions

HBL’s latest report shows that large organisations have the ability to do good and must start treating it as part of their duty

that they think will directly impact the lives of everyday Pakistanis and help uplift them, the economy, and the natural environment of the world we live in.

Many might take HBL’s report and claims with a grain of salt. Banks, afterall, get a bad reputation. These are the very same profit hungry institutions that parents warn their children to never trust and stay away from along with lawyers, real estate agents, and the scoundrels of the print media. But despite this bad press, the reality is that large organisations can be vehicles for good.

In particular, the largest bank in any country can do more than its fair share in uplifting a country and its people. For starters, good banking products and a hunger to build a client base can bring large chunks of the unbanked population into the fold of formal financial institutions. Loans targeted towards SMEs and important sectors of the economy can help bring many out of poverty and boost economic activity in the country.

In its recently released report, this is exactly what HBL says it wants to do. The operative word here is ‘wants’. Effective communication can go a long way and on this front HBL is successful. All of their messaging indicates that being a force for good and betterment is not something they feel they have to come across as but something they actively want to be.

You see there is a vital difference between responsibility and duty. While the two are inextricably linked there is a certain passiveness in being responsible that is trumped by the pro-activeness of being dutiful — particularly in a corporate setting. You see responsibility is a burden. It is something you feel the need to address. It is a cheque you begrudgingly cut to keep up appearances. It is a weight that pulls you down. Duty, on the other hand, is a force that pushes you forward. An organisation feels the burden of responsibility but a sense of duty fuels its actions.

By releasing its Impact and Sustainability report, HBL wants to firmly set itself in the latter category. This is something that regularly happens to large organisations. As time passes they want to position themselves as forces beyond just what their initial purpose was. That is now what HBL is trying to do — to be “More than just a Bank” as its senior leadership tells us over and over again. But just how much can a bank do?

Let us break this down to a very simple level. There are really only two things that a bank like HBL can do. The first is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) projects. These are causes that are either directly charitable or ones where money

is being directed towards a certain end. These are things such as assistance with flood relief or sponsoring a sports tournament. And then there is the real work — building products that can change a country.

As we’ve mentioned before, there is a lot a bank can do and especially in a country like Pakistan. The unbanked population is massive and in particular there is a dire need for women to be brought into the formal financial sector. Access to money for farmers, small businesses, and SMEs can also change the economic map of an entire country.

So what does HBL want to do? “At HBL, sustainability is not merely a buzzword, but a fundamental pillar of our operations which includes integration of sustainable principles and practices across all facets of our organisation, from operations to supply chain to financial services and stakeholder management,” says Muhammad Aurangzeb. The origins of the report came from HBL’s recent decision to complete its commitment to achieving net zero emissions and green funding.

“In pursuance of HBL’s commitment to inclusion, sustainability and community development, the Bank is pledged to: reducing its own emissions; expanding our Green Banking portfolio; expanding our women customer base to over 4 million; and contributing to the communities in which we operate by supporting healthcare, education, arts, and social development initiatives,” he adds.

The ethos behind this, as per HBL, comes from its parent company — the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development. “Upholding the ethos of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), HBL’s good governance and Corporate Social Responsibility is not confined to charitable giving, but also directed at conducting our daily business and living our daily lives with constant care for our physical and social environments. As the country’s largest banking group, we can foster positive change by example, leading with our walk as well as our talk,” said Sultan Ali Allan, Chairman of HBL, in his message on the occasion.

So what has HBL done? According to the summary of the report that they provided, HBL has contributed over Rs 4 billion - spread over a decade - for the social uplift of Pakistan. In 2022 alone, the Bank contributed over Rs 580 million.

There are many initiatives that HBL has launched that fall within the ambit of traditional CSR. On the one hand there are those that would insist large businesses are not responsible and forget the impact that they can have on a society. On the other hand whenever an organisation does try to do something

for the greater good, their efforts are often dismissed either as marketing attempts or bare-minimum CSR work.

One such example is how HBL partnered with the Government of Pakistan and the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) to assist flood-affected families through Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) and disbursed Rs 54 billion in relief to flood affectees. The bank has also funded the building of two purpose-built villages, comprising 100 homes each in Qamber Shahdadkot and Larkana in Sindh. The cost of these prefabricated villages that are equipped with solar panels is over Rs 264 million. In an internal move, aimed at supporting its experienced workforce and promoting job security, HBL extended its staff service age from 60 to 65 years in 2022.

And then there is the next part. There is a lot that the HBL does in terms of CSR. There is still more they do on a larger scale such as being the sponsor for the HBL PSL which has helped bring cricket back to Pakistan. But the most important thing that Pakistan’s largest bank can really do is create products that will bring financial inclusion and access to money to people that need it.

“The HBL Microfinance Bank has contributed tremendously to ensuring that we are the single largest provider of microfinance and SME services in Pakistan. As the country’s largest banking group, we can foster positive change by example, leading with our walk as well as our talk,” read the bank’s statement following the release of its report.

“Our unwavering commitment to sustainability is enabling us to play a leading role in developing the agricultural sector and promoting food security through investing in relevant learning and infrastructure.”

As part of the HBL’s Development Finance initiative, the Bank has completed 17 pilot projects, supporting 550 farmers through in-kind financing for crops spanning over 45,000 crop acres. The bank has also developed its own Green Taxonomy (GT) which will facilitate directing capital flows to green projects. With a 27% increase in funding, HBL Foundation has deepened its contribution across key areas of need, ranging from health to education.

All of these moves from Microfinance to reaching out to farmers goes a long way for an organisation like HBL but also helps Pakistan. If the country’s largest bank is indeed to fulfil its desire to be “more than just a bank” it must continue on this trajectory — both for its own ambitions and for the sake of the country. n

philosophy they are trying to espouse

with PFM find it even more difficult to reach follow-on rounds. Had the funding environment not changed so drastically, some of the startups that have failed or are going to fail in the next 12-18 months would have been able to raise the capital to either reach the fit or still die a natural death. Failure is an integral part of the startup ecosystem and founders will either make a lot of money or learn some valuable lessons. Remember, success is a lousy teacher and failures tend to teach you a lot more lessons.

Ever since the demise of Airlift, failing startups have served as gossip fodder in this ecosystem. However, the recent string of news has turned the gossip into outright vitriol.

I have recently seen Aman Nasir (Sarmayacar), Kalsoom Lakhani (i2iv) and Sheryar Hydri (Deosai Ventures) come out and defend the fallen startups and their founders. They have presented very valid points but I thought perhaps my perspective as a founder who has seen both success and failures in his journey, may help some of the critics see things in a different light.

We need to understand the background of the failures. Pakistan for the first time had become an interesting emerging market where international and regional VCs had started taking interest. Unfortunately Pakistan only caught the tail end of the great funding wave and the party was over soon after it started. Most of the local and international VCs are finding it challenging to raise new funds.The dry powder (existing funds) they have are being preserved for the existing portfolio companies.

Many startups that received funding were not able to establish themselves. With scarce funding opportunities, companies struggling

Please understand that failure already has an extremely negative connotation in our society. When entrepreneurs march forth with their ideas, there are umpteenth rejections on the way, from prospective employees to investors and customers. An entrepreneur takes a plunge while putting a career on hold or leaving a well paying job. The uncertainty and challenges of the venture itself take a huge toll on the mental well being of the person. Despite all the effort and pain, if the venture fails, the added pain of public accusations of wrongdoing is something that can put someone over the edge.

Like many have pointed out, it's not public money and the founders are not answerable to you. They are liable to answer to their customers, employees and investors and unless you are one of them, please refrain from passing half baked judgements on the matter.

The aftermath of a failed startup can have a profound impact on the founders, leaving emotional, financial, and professional scars that may take years to heal.

The emotional toll of startup failure can be immense. Founders invest not only their time, money, and effort into their ventures but also their dreams and aspirations. When the venture collapses, they experience a sense of loss, disappointment, and even shame. The fear of judgment from others and the feeling of letting down supporters can lead to anxiety and depression. The psychological burden can be overwhelming.

Founders like myself pour their personal savings into the startup. The financial implications of a startup failure can be devastating, leaving founders in dire straits.This financial burden can extend beyond the founders, impacting their families and relationships as well.

Considering the attitude of our society in general, a failed startup can seriously damage the professional reputation of its founders. Potential investors, partners, and employers may view the failure as a reflection of the founder's capabilities and decision-making skills. Rebuilding trust and credibility in the business community can be an arduous process, and some founders may face difficulties

My perspective as a founder who has seen both success and failures in his journey may help some of the critics see things in a different light

securing new opportunities or funding for future ventures.

For many founders, their startup becomes an integral part of their identity. In startup circles, my introduction is usually with my startups’ name depending on which city I am in (some are more popular in one city than the other). When there is such a close association between our startup and us, the failure of the venture can lead to a crisis of identity, leaving the founder wondering who they are outside of their entrepreneurial pursuit. Letting go of the startup and its vision can be emotionally wrenching, leaving founders to redefine their goals and purpose in life.

The pursuit of a startup often demands significant time and energy, which can strain personal relationships. Founders may neglect

family, friends, and even their own well-being in the quest to make their venture succeed. When the startup fails, these relationships may suffer further, as the founder grapples with guilt and regret over the sacrifices made.

The fear of failure can become a significant obstacle for founders who wish to embark on new entrepreneurial ventures. Having experienced the pain of startup failure, some may hesitate to take risks again, even if they have a brilliant idea and the necessary skills. This fear can inhibit growth and creativity, preventing founders from realizing their full potential.

Despite the pain and challenges, startup failure can also be a valuable teacher. Founders who have weathered the storm gain a wealth of experience and insights that can prove invaluable in future endeavors. Resil-

ience, adaptability, and the ability to learn from failure are traits that can set a founder up for success down the road.

In the end, I will say that the journey of a startup founder is not for the faint hearted. While success stories often make headlines, the reality is that most startups fail, leaving their founders to grapple with the aftermath. The emotional, financial, and professional toll of failure can be overwhelming, and it takes a significant amount of courage to pick up the pieces and move forward. However, when one is struggling with the shame and guilt of losing the venture and letting family, friends, employees, investors, customers down - the last thing a founder needs is baseless accusations from people who have no idea of the struggles and challenges one has faced. Learn to be and let people be, kindly.

“The authorities destroyed everything we had. Is the home we have lived in for 40 years not our own?”

– An evictee of Islamabad’s most populated slum settlement

We’ve all seen it.

Photos and videos on social media of bureaucrats proudly standing by and watching as bulldozers and policemen clear government owned land and save it from encroachment. The problem, however, is that there are no big, bad, real estate developers or kabza mafia being thrown

to the curb. Instead, these anti encroachment drives focus either entirely on slums and shanty towns or on small shack or cart businesses that do not have proper ‘permits’.

According to the 2020 UN Habitat report, 56% of Pakistan’s entire urban population lives in slums. This means that if in 2020 , Pakistan’s recorded urban population size was 84 million then approximately 47 million Pakistanis reside in informal settlements. To illustrate the significance of this number, it would take 4 cities the size of Lahore to house 47 million people. However, not only do our state authorities not recognize the existence of these housing settlements but they also continuously label them as illegal encroachments, leading to a spree of demolitions and widespread displacement.

Perhaps one of the places where this is best illustrated is Islamabad. With no encroachment protection laws passed on a federal level, such demolitions are a free for all in the country’s capital. But why are our bureaucrats so happy to bulldoze and displace hundreds of people at a time? The answer lies in the very master plan of Islamabad and the bigotry that is built into the Capital’s bones.

The central premise around Islamabad’s master plan and urban layout, as decided by Greek architect Apostolos Doxiadis, was meant to

Inside the misplaced and disproportionate focus on ‘encroachment’ drives

be exclusionary. The extent of this exclusivity is expressed in Doxiadis’s refusal to let the builders of the city be housed within the city. It was this refusal that led to the construction of precarious labour camps in Islamabad’s periphery– later turned into the Katchi Abadis that we know today.

It is this very legacy that underpins the reality of the anti-encroachment drives in Islamabad today. The legality of these settlements is not necessarily a question of legislation or an absence of documentation but rather a determinant of an anti-poor bias within the country’s governance. In our interview with Umar Gillani, a partner at the Law and Policy Chambers as well as a legal consultant at UNDP, he expressed that he recently filed a petition against the unlawful impris-

onment of a street vendor in Islamabad. Mr. Gillani shared that this vendor, an old man, had been selling Kulfis in the same spot in front of Faisal Masjid in Islamabad for the last 30 years. However, the CDA had taken notice earlier this month and entitled his presence as an encroachment for which he was presented in front of a magistrate and punished with 5 months of imprisonment for his crime. The lawyer explained that such depictions of arbitrary governance reveal a deeper ideological power play within our state departments and their evident intentions to only safeguard and appeal to the urban elite.

In Islamabad this is shown through Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar congratulating the police forces and the CDA on its successful demolition of Katchi Abadis. In Lahore this is shown through Firdous Ashiq Awan calling the New Lahore Ravi project, which would demolish the sprawled housing to create a more “developed” community, as a dream come true for Pakistanis. And in Karachi this is shown through the Mayor of the city Waseem Akhtar explaining that the culture of Pakistan is not depicted through the textiles and spices sold in the Express Market, but rather through “modern” recreational projects like parks that were to replace the Market itself.

Therefore, this is an old pattern of bigotry that resurfaces frequently. In order to put a halt to this reinforced narrative, a proper policy defending the right to dignity and housing ideally expressed in the constitution– in addition to Article 38– would perhaps protect these “illegal” informal settlements which actually provide wage-laborer populations with the housing that the state has failed to provide from being conveniently and randomly perched just outside legality whenever the state deems necessary.

The beginning of the mission to protect the country and its people from the contagious evil of the slum settlements can be traced back to a bizarre turn of events in Islamabad’s High Court almost a decade ago.

Amin Khan, a resident of the G-11 Katchi Abadi (informal settlement) filed a petition before the Islamabad High Court in 2014 against the Federation of Pakistan and the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) requesting the issuance of a computerized national identity card (CNIC). Although originally from FATA, Khan had included his G-11 address on his CNIC request which sent alarm bells ringing for senior Justice Shaukat Aziz of the Islamabad High Court who directed the case to the Ministry of Interior, demanding they explain the presence

and legitimacy of Katchi Abadis in Islamabad. This was perhaps the first switch in the chain reaction that ensued.

The following year, in June 2015, the Capital Development Authority (CDA) submitted a four-phase plan for the removal of 42 illegal slums in the capital to the Islamabad High Court. In their pre-operations activities, the authority proposed the disconnection of all the allied facilities of the Islamabad Electric Supply Company (Iesco), Sui Northern Gas Pipelines (SNGPL) as well as the issuance of FIRs against the slum dwellers for having illegal connections.

For the swift execution of this fourphase plan, the assistance of 700 CDA employees, 20 reserves of the police, one company of the Rangers amongst many other officials was also sought.

The following month, in July 2015, a single-judge bench consisting of Justice Shaukat Aziz Siddiqi, for whom the ringing had apparently still not stopped, heard the petitions seeking CDA allotted land to be vacated from slum dwellers. The Islamabad High Court subsequently ordered for the removal of the I-11 Katchi Abadi on the grounds that Katchi Abadi inhabitants had encroached upon green belts and around 150 developed plots that had been allotted to people by the CDA in 1985 who were still awaiting possession of their land.

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) the I-11 Katchi Abadi was home to 864 families and 8,000 people in 2013. The process of this court mandated removal, therefore, witnessed dozens of residents being arrested, 1000’s having FIRs registered against them under the Anti-Terrorist Act, and over 15,000 residents being made homeless overnight.

It is integral to note that this tremendous 30 year lapse of time would have rendered this eviction process illegal in Sindh, Punjab, KPK and even Balochistan after 2017 because each of these provinces have passed a Katchi Abadi Act that protects against such arbitrary and unjust demolitions. According to these Acts, principles of longevity of stay and the size of the informal settlements are considered before ordering for their removal. This means that if an informal settlement housing a large number of residents has existed in an area for more than three decades which can be proved through any documentation of electricity bills, lease agreements, or unemployment benefit registrations, their settlement would be protected by law. However, while the Capital Territory does have a Katchi Abadi Community DataBase and efforts have been made by the CDA to now recognize these settlements, merely 11 out of an approximate 55 slum settlements have been recognized so far. n

The idea of social change is a tempting one. And even more tempting is the idea of institutionalized social change. Ask a fresh graduate, trying to get a well-paying sales position, in their favorite consumer goods company, and you will not hear the end of how their profitable enterprise is making the world a better place. They will throw a list of the CSR projects that their company overtook in the last year to prove how they are an integral part of social justice.

But what is CSR? How does it work? Does it even work? And how much of it is needed?

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), (which can also be named anything else based on how privy a company is to jargon) is a company’s voluntary expenditure on social causes. Its donations, charity and so on. It serves as a tool for companies to stand true to their mission statements and their values.

On the face of it, CSR sounds like a no

brainer, much like charity. But there is an existing debate that surrounds the topic, not only making it controversial, but also making it a head scratcher for policy makers around the world.

In recent years, the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has taken center stage in the business world, sparking intense debates among industry experts, activists, and stakeholders. As companies face increasing pressure to address social and environmental issues, the discussion around CSR’s merits and drawbacks has intensified. Let’s have a look at what this discussion entails

There is no doubt that CSR serves a greater purpose. Any influx of cash for social causes is an addition to the existing pool. But that is not all the benefits that CSR has. But that is not all the benefits that CSR provides. It can be beneficial

to companies too in more ways than one. Embracing CSR initiatives can bolster a company’s reputation, leading to increased customer loyalty and positive word-of-mouth. Consumers are more likely to support brands that are actively contributing to social causes. This indirectly translates in terms of sales and revenue for the company. It gives a company the sort of PR that could reel in a whole different share of consumers. Knowing that one brand is likely to change the world with your money, is a good incentive to choose that brand over others.

A strong commitment to CSR can also attract skilled and socially-conscious employees who want to work for organizations aligned with their values. This could lead to a motivated and dedicated workforce.

One would wonder how something as selfless as charity be misconstrued? For starters it is but an issue of consent and representation. A company has many shareholders. These shareholders

CSR is a contested subject between shareholders and companies, but how can it be tamed to only be a force for good

buy a share in the companies with the hope of making financial gains and obtaining returns.

And here is the catch. When a company undertakes CSR projects, it involves the input of its board and senior management. But a minority shareholder might have close to no say in the expenditure. For someone only concerned with the profitability of their own stock in a company, any additional burden on the profits is essentially a portion of equity lost. It can especially be financially burdensome for smaller companies, diverting resources from core operations.

So apart from putting financials under crunch, it becomes an issue of representation. What if the minority shareholder is already content with the amount of charity that they allocate from their pool of wealth? Where is their say in the company’s undertaking additional social responsibility at the behest of their equity.

Then there comes the issue of greenwashing. What if a company is not doing as much good as it would project? Critics have long argued that CSR is more of a marketing stunt than it is a will to bring social change. In greenwashing, a company would reap the PR benefits of being associated with social change without really making a dent in the status quo. This would translate more into their balance sheet in terms of revenue than it would set it back with the mere peanuts that they threw in as emotional bait.

A company could also be seeking an escape from its internalized problems with CSR. While it may be money for societal good, it could be to divert the focus from its internalized problems like labor exploitation and unethical supply chain practices. Apart from these questions there is another part of the debate.

The answer to this question varies from country to country. For the first world, one company could have the profits to solve the majority of the problems while in the third world, the collective profits of all the companies could not make even a dent in the social system.

For a country like Pakistan, it is almost impossible for one, two or even many companies to solve the collective problems. And this is how companies get to decide what they want to contribute to. Something that resonates with their brand’s image. Their mission statement or their collective sentiments. And it can be surprising, how much a company can achieve on one front, if it dedicates its efforts. Let’s take the example of one of the biggest corporations in Pakistan and how its dedicated efforts brought about a change in athlete development.

When most companies would rather spend on education, human rights and gender rights in Pakistan. Engro Foundation, a CSR arm of Engro corporation, also decided to invest in the country’s athletes. Pakistan, a country that has given birth to a number of great athletes in various disciplines still has not been able to place itself on the global sports map, other than cricket.

A fair example of that is volleyball. Volleyball is “arguably the second most popular game of Pakistan apart from cricket.” as per the assistant coach of the Pakistan volleyball team. Whether it really is the second most popular game is debatable but there is no doubt in the fact that volleyball is a popular game.

Despite being so popular, and despite having the sixth largest population of the world, the Pakistan Volleyball Federation (PVF) has no accolades to show for it. It is sad how the immense talent in Pakistan is deprived of the opportunity to compete at the world stage. With lack of sponsors and funding, the PVF has forever been reliant on pennies sent its way by the already financially strapped state of Pakistan.

“The financial struggle used to be to a point where our last Federation Chairman had to sell one of his properties to send the team to compete at an international tournament.” says Muhammad Saeed the Assistant coach of the Pakistan volleyball team. However, with a much needed cash injection and a sponsorship provided by Engro, Pakistan team has been able to change its fortune. The team now has international coaches, a streamlined process of talent scouting, and access to world class training facilities, along with proper health and nutrition management.

Therefore the raw talent of Pakistan has been turned into players that eventually won the Central Asian Games in 2022. “We are now eyeing a spot in the next international volleyball world cup and the 2028 olympics and it has all been due to the help of engro.” says the Pakistan team captain, Mubashir Raza.

But this is just one of the many causes that the Engro foundation serves and as we will later find out how money spent on volleyball might just be less than 0.5% of Engro’s profits. Imagine what could be achieved if companies, especially big ones, were to spend only a fraction of what they were earning towards one particular cause.

Now that we know what CSR can achieve, what about the debate over CSR.

There is more to CSR than meets the eye. A country like Pakistan that has overheads to doing business, changing political climate and extraneous risks, would always pose a threat to the company’s bottom line. Therefore what a company is comfortable in committing throughout its operational cycle for it to still turn out as a profitable entity at the end of the year, raises questions.

Far-sighted policy makers of the world recognized the problem with CSR long ago. And have since developed a mechanism for making it easier to bring corporate money into non-profitable causes.

Countries such as China, UK, Indonesia and even India, have put up a mandatory CSR threshold. This way, CSR, no longer remains the prerogative of the company, rather it becomes an imposition, much like taxes.

Not only that, this standardizes the process of CSR expenditure. The Companies Act 2013 of India mandates it upon companies to spend 2% of their 3 year declared profits on CSR. Companies can go above and beyond that limit and they have.

If we compare that to Pakistan, a country that is in no way any less socially downtrodden than India, even companies with vast CSR portfolios barely touch this 2% mark. Engro, for example, barely spent 2% of its 3 year profits on CSR, in the last 3 years. To put that number in context, their 2% amounted to around Rs 2.96 billion, while their profits were Rs 142.8 billion from the last 3 years. But engro is considered a CSR heavy, almost a benchmark for CSR in Pakistan. The same percentage for a company like Nestle, another huge company, stood at 0.19%, which amounts up to Rs 73 million out of its cumulative profits of 36.7 billion in the last 3 years.

Pakistan is a country of charitable people, and so is the essence of our constitution. There is a strong case for a mandatory CSR share but for that to happen, the state must be able to ensure baseline security to operations. Otherwise at the current pace, companies will not think twice before faltering on such a mandate.

As the world evolves, so will the debate around CSR, as businesses continue to navigate the delicate balance between profitability and meaningful social impact. Even with voluntary CSR, the key lies in transparent reporting, genuine commitment, and long-term vision, ensuring that CSR initiatives deliver tangible benefits for society and create a more responsible and sustainable corporate sector. n