08

08 Managing Expectations: The latest dollar value conundrum

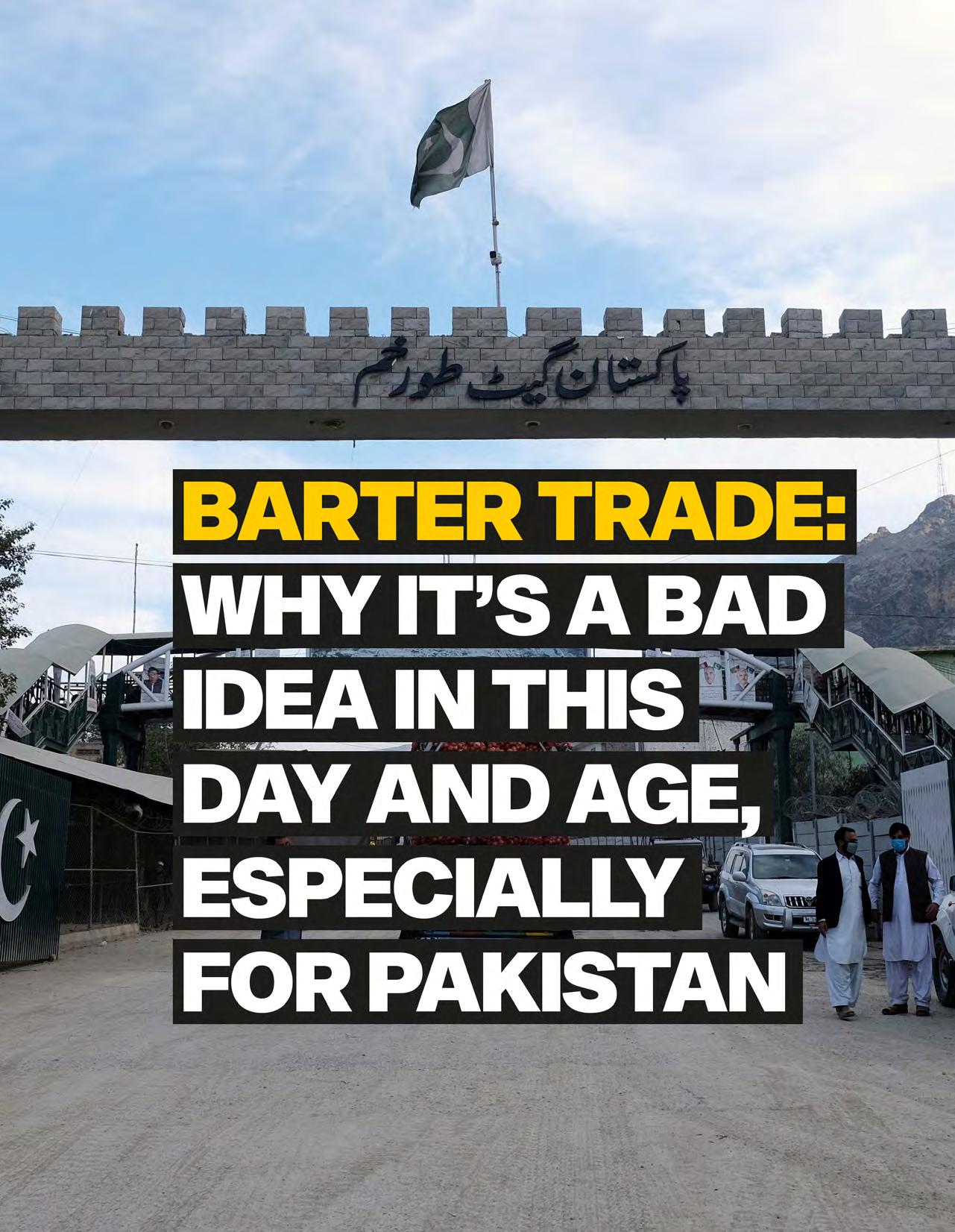

10 Barter trade: Why it’s a bad idea in this day and age, especially for Pakistan

18

18 Another year, another wishy washy budget for the agri sector

22 Another hair-brained idea or a workable solution to our dollar woes?

25

25 Shahzada and Suleman Dawood

27 Solarizing household energy

28 How a crippled economy is forcing a valuable part of the workforce to leave their motherland

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

It is tough to be in the State Bank’s shoes right now. Some argue that it is always tough to be in such a position. But what is the challenge this time?

The Bank has to cover more than three ends at once with a reserve that is close to its worst ever. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has clearly communicated the condition that the rupee should maintain its actual value. However, there is debate about what exactly that actual value entails. Market intervention and government control of the exchange rate are viewed unfavorably by the Fund.

At the same time, for the country’s survival, proper management of the current account is needed. The removal of import checks is necessary to enable consumption and subsequent export.

Last but not least, there is a government in office that wants to control the currency, improve the value of the rupee, and leave office on a high note before the next elections. The Finance Minister, Ishaq Dar, has openly favored undervaluation and considers a strong local currency one of his key objectives. In such a situation, what is the State Bank doing? Why is it doing that? And what does it mean for the future of the dollar against the rupee?

By definition, foreign currency is not supposed to be a yield-generating investment. However, in the case of Pakistan, it has somehow outperformed the money market and the stock market. As a result, our peers “invest” in dollars whenever they get the chance. Why is that? Because for them, the

dollar is a one-way bet.

Until last month, people believed that the country would fail to secure external financing. They thought that the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility would go down the drain and Pakistan would default on its debt obligations. In such a scenario, the only way to protect their money from devaluation was to hold an asset that would not lose value. For many Pakistanis, that asset was the dollar.

This creates a demand for dollars, not just as a currency but as a store of value. No amount of dollars is enough to satisfy that demand because once people have some, they want more. While this was happening, various stakeholders were playing games with the dollar. Arbitrary caps were removed, and selling was done in the black market or at enormous spreads. The State Bank has been tackling these issues as they arise.

But over time, with growing fears of default, the demand for dollars continued to increase. On June 27th, the majority of the market went home with a long position, meaning they held onto their current stock, anticipating the interbank rate to reach around 300. During this time, people left for Eid, markets closed, and businesses halted. Suddenly, the country received approval from the IMF, and sentiment changed. People started second-guessing their decisions. The market, which had a collective long position on the dollar, began to falter.

With the IMF deal in place, it was expected that trading would resume at its closing value before Eid. However,

when the banks opened on July 4th, the dollar plummeted by a whole 15 rupees at the start of the session. How did this happen?

The answer lies in sentiment. Although there were payments to be made, it was the 4th of July, a day when New York is closed. Normally, payments don’t occur on such days. An importer can come and perform an exchange transaction at the sales desk, but dollars won’t be provided, even if the bank has them. So the payment would be executed on July 5th. Consequently, the importer did not come to the bank, and the speculation of IMF inflows appreciated the rupee.

Another reason is the flow of remittances and export proceeds. While markets were closed for Eid in Pakistan, they were open worldwide. This meant that whatever remittance and export proceeds were sent during the Eid holidays were processed on July 4th. The sense of availability triggered some players to sell, creating a mild sense of panic.

Saad bin Naseer, the Director of Mettis Global, pointed out that individuals hoarding dollars would likely panic once foreign exchange reserves begin to increase. Consequently, there may be a surge in remittances through official banking channels, as the risky hundi-hawala system may become less attractive.

Later in the day, the exchange rate rose again by a few rupees and has since been increasing, reaching around Rs 277. Interestingly, there are still very few sellers in the market. People believe that this is a temporary correction, and as the country will inevitably return to its usual state of financial and political instability, dollars will become more expensive.

As part of the Stand-By Arrangement with the IMF, there is a letter of intent. This letter includes various commitments from Pakistan to the IMF, but most importantly, it contains the commitment by the State Bank governor to allow the free flow of imports, enabling the rupee to reach its real value.

Over the past 10 months, the State Bank has exercised administrative measures on imports. Whenever someone wants to import something, their bank must obtain prior approval from the State Bank of Pakistan. As a result, the import bill has been reduced significantly. In fact, Pakistan has been able to run consecutive current account surpluses for the first time this decade.

Imports decreased by 31% in FY23 to $55.29 billion, from $80.13 billion in FY 22.

Ideally, a surplus should decrease the value of the rupee, even if the surplus is fundamentally questionable. Because in any case the amount of dollars in circulation has now increased. But why hasn’t the value of the rupee increased? The reason is the State Bank’s buying. To ensure that the rupee-dollar rate reflects its actual value and to accumulate dollar reserves, the State Bank of Pakistan has been a net buyer in recent weeks.

According to sources, the State Bank has deliberately kept the rate high to prevent significant discrepancies between the open market and interbank rates. It’s important to note that the central bank has the prerogative to buy from the open market. In fact, the IMF prefers the central bank to be a net buyer rather than a net seller in a given month. With limits to its intervention, the State Bank is entitled to make purchases and sales to avoid excessive volatility.

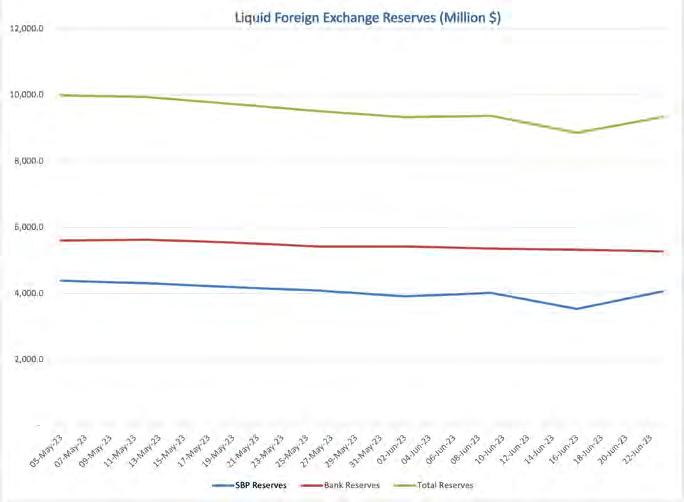

The fact that the State Bank has been buying from the banks periodically, can be seen in the graph below, indicating marginally lower bank reserves for every consequent week. Currently, it is believed the State Bank has negative real reserves, with short-term obligations exceeding its available funds. To prioritize stability, it is crucial for the SBP to build reserves whenever an opportunity arises.

However, the status quo can be jarring. Credible sources have revealed that despite committing to freely flowing imports to the IMF in its letter of intent, the government and the State Bank do not intend to allow imports to flow freely.

This is not open defiance but rather a loophole. Banks do not print dollars; they either buy them from the interbank market or receive them directly from overseas. It has been revealed that the State Bank has instructed

banks to maintain their Net Open Position, square. This means that banks can only spend as much as they earn, keeping their inflows and outflows equal. Consequently, imports are substantially limited automatically. Especially for larger banks that have an importer-heavy clientele.

Not only does this mean that the State Bank is controlling the amount of imports again but this has a direct impact on the currency.

This move indicates that even though the State Bank cannot let the open market operators create discrapancies between open market and interbank rates, it still cannot let the dollar go upwards of a certain limit.

Another source privy to the treasury market developments has even suggested that the State Bank is still exerting unofficial control over the opening of Letters of Credit (LCs). If this is true, it could pose a threat to the much-needed IMF program. The State Bank of Pakistan has been contacted for comment on this matter, but no response has been received.

While the entire picture is murky. A few things are certain. The rupee is currently a little below its real value. Ishaq Dar, even with his questionable credibility, is right in saying that the rupee is undervalued. Talking to a private TV channel, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar stated, “Based on the real effective exchange rate (REER), the rupee-dollar parity should be Rs244 to a dollar”. He said this on the back of a statement by Ankur Shukla, South Asia Economist for Bloomberg Economics. He said that, “Pakistan’s

rupee is undervalued by about 14%, according to our model.”

The State Bank’s buying position is understandable. With record profits and dwindling foreign reserves, the central bank needs reserves more than ever. And the market needs stability. In fact, one of the reasons why the dollar rate went up after plummeting on the first day of trade after Eid, was because of the State Bank’s buying. But if the imports are indeed, being indirectly controlled, the dollar rate is not representative of the market forces.

The government realizes that the dollar rate needs one last push before it corrects itself for good. It could be in the form of physical inflows or a mere green signal by the State Bank. This makes it risky for banks to hold dollars in their own reserves, so they are now going to be having a short position on dollars. This makes it perfect for the SBP to limit imports through square NOPs.

As of now they are milking the situation for best possible effect. One little nudge to the downside and all the exchange companies, exporters, hoarders and speculators will run to sell. If they do, the rupee goes soaring up. Politically this would be huge for the ruling party but what is on the other side?

Imports would have to start again at some point. For real. The banks cannot be infantilized with their LC operations forever? With properly resumed imports, all the effect created by the orchestrated current account deficit can erode. Who is to say that the value of the dollar might once again go beyond 280. It’s a standoff, a decision theory conundrum.

The bottom line is that there is a shortage of dollars in the market and we stand one panic spree, or one import clearing notification away from a freefall, in either direction. n

Pakistan remains in a precariously tough economic position. Even with the finalization of the $3 billion IMF deal last week, fundamental problems and underlying weaknesses will remain to evolve into larger issues down the line. We have a crippling balance of payments issue that will only be resolved if somehow we manage to increase exports and FDI, both of which are long term time consuming undertakings that we neither have the time nor structural capacity at the moment to achieve.

The country has cut its trade deficit by a whopping 43% to $27.55 billion in FY 2023, down from a daunting $48.35 billion in FY 2022. This is largely owing to administrative measures such as the restrictions on imports. Imports decreased by 31% to $55.29 bil lion, from $80.13 billion the previous financial year.

But exports also contracted by nearly 13% to 27.74 billion, from $31.78 billion in FY 2022. Therefore, the drop in imports is how the government has managed to achieve the drop in trade deficit. With all import restrictions removed, a reversal is likely to begin because as things stand, there is no likelihood of an immediate increase in exports.

As such, the government continues to manage matters on a more immediate term, day-to-day basis. Restricting the import of ‘nonessential’ goods is one example (SBP has recently allowed the import of all goods to satisfy the IMF, but restrictions had be en in place for close to a year prior).

More recently, an option of barter trade with neighboring countries has been explored. Early this month Pakistan passed a special order to allow barter trade with Afghanistan, Iran an d Russia for certain goods, including petroleum and gas. The move is claimed to be an option to ‘ease the demand for dollars’ as Pakistan’s government is desperately trying to manage a balance of payments

The recent agreement with Iran, Afghanistan and Russia to engage in barter trade might be great marketing for an economically struggling government, but remains impractical

The import and export of goods in exchange for goods is quite difficult

Usman Qureshi, Joint Secretary Ministry of Commerce

crisis and bring inflation under control after it hit a record of nearly 38% last month.

The government order, called the Business-to-business (B2B) Barter Trade Mechanism 2023 and dated June 1, lists goods that can be bartered.

Although the Barter Trade agreement (BTA) signed by Pakistan is being portrayed as a big achievement to boost exports and enhance bilateral trade, there is a lot that remains unexplained and does not make a lot of sense. In this story we attempt to explain the mechanics of what has been proposed and whether or not it is implementable in the presence of modern day trade and.

In short, it is a very difficult mechanism to implement effectively enough to make the gains that the government has claimed it will make through this agreement, which is to reduce the dependence on USD for trade and arrest the increasing imbalance in trade with other countries.

Much of the procedure under which this trade will take place has been defined in an SRO issued on June 1, 2023. It is evidently not dissimilar to conventional trade rules and regulations with the text saying, ‘The trade has to comply with Import and Export Policy Orders and meet all relevant regulatory requirements, including permits, licenses, certificates, and quotas specified in the IPO and EPO’ and ‘applicable duties, taxes, fees, and charges are levied on imported and exported goods’.

The process is defined as “import before export”. ‘Pakistani traders are responsible for netting off the value of goods within 90 days after receiving authorization’, the relevant section of the SRO goes on to say.

The SRO doesn’t tell us much. It is difficult to understand and problematic to

implement. Let’s say an Iranian pulses trader and a Pakistani wheat trader want to make a deal. According to the SRO, the Iranian trader will export an X amount of pulses at an agreed upon rate first. Within 90 days, the Pakistani wheat trader will send what he owes to his Iranian counterpart in equivalent volume.

Under what circumstances would a wheat trader in Pakistan find a pulses trader in Iran in search of wheat for his pulses, or vice versa? It is highly unlikely.

But let’s assume such a deal is struck. How will the two equate volumes to reach a fair deal with the price of both commodities already established for that particular day in their respective countries, wheat and pulses price in Iranian Rial for Iran and the prices for the same in Pakistani market in rupee? Will both commodities be priced in USD? There is not much clarity on this.

Lastly, a lot can happen to the prices of both commodities in 90 days, in either country. Will the deal be renegotiated if such a price movement occurs? Isn’t Iran, the exporter at the first stage of the transaction who will later become an importer of wheat as payment, at an obvious disadvantage? The pricing mechanism is so far unclear.

Profit spoke to Joint Secretary Ministry of Commerce, Usman Qureshi who is dealing with the barter trade initiative to get some clarity on the matter.

“It is the responsibility of the local importer/exporter to make arrangements for both the importing/exporting goods and all deals with his/her partner in another country (of the three countries)”, he added.

While researching for this story Profit came to the conclusion that the only plausible mechanism through which barter trade could be done effectively was the inclusion of a third party, a middle man, on both sides of the border.

Qureshi concurred, stating that the role of a third company may be needed for those interested in barter trade to deal with the difficulties in the exchange of goods.

“Trading companies may be consulted by traders for this business”, he added.

There would technically be two layers to this sort of cross border trading. The first would be the actual buyers and sellers of specific goods. But as mentioned earlier, it would be impossible for them to exchange those different goods with each other. This is where the second layer comes in, the middleman, on both sides of the border.

Let’s demonstrate how this would work using an example. In Pakistan, there is a wheat mill owner (company A) looking to take advantage of the BTA and a Russian oil refinery (company B) wishing to do the same. However, as already established, the wheat miller has no use for Russian oil and vice versa. This is where the middleman comes in.

Company A will engage a local trader (middleman A) dealing in multiple commodities and company B will do the same in Russia (middleman B). As far as the companies are concerned, they are only selling their goods to

Oil purchases could rise to 100,000 barrels per day (bpd) if the first transaction goes smoothly

Musadik Malik, Minister of State

their respective middlemen and receiving payment at an agreed upon market price, minus the commission the middleman will charge for his services.

The middlemen’s task is a bit trickier. Middleman A needs to find a buyer of Russian oil in Pakistan. Similarly, in Russia, middleman B has to find a buyer of wheat. Once both middlemen connect, they will negotiate a price for the commodities they have already bought; wheat in Pakistan against oil in Russia.

Middleman A strikes a deal in Pakistan with a local refinery for 10 barrels of Russian crude oil at the rate of $100 per barrel; a total cost of $1000. He proceeds to convey this demand to middleman B in Russia, perhaps he keeps a small margin as well. Middleman A then conveys that he has wheat to sell for the oil he requires. Middleman B agrees to take the wheat after locating a buyer in Russia. He negotiates a price for wheat in USD that has to be equivalent to $1000. Let’s say this is agreed at $10 per kg of wheat, which would mean a 100 kg of wheat going across the border to Russia to middleman B.

What happens as a result is that goods of equal value are exported and imported from each country, which is what the government wants out of this deal; balanced trade.

Complicated? Yes. Workable? Perhaps. But this is the only conceivable way in which what is being proposed and marketed by the

All trade in Pakistan in the formal economy is done through the interbank, which means through commercial banks. All trade is therefore done in terms of US dollars, both imports and exports. Those dollar reserves everyone keeps talking about; they are made up of two main components: net reserves with SBP and net reserves with banks. Currently these stand at $4.46 billion and $5.28 billion respectively. The latter is the amount of USD present in the interbank, or with commercial banks, collectively. These are the dollars that are used for trade. There are inflows (exports, remittances, FDI etc.) and outflows (imports, dividend payments to foreign companies etc.). As Pakistan is a net importer of goods and services, it is alway strapped for dollars, which is typically defined as a ‘shortage of dollars in the interbank market’. The reserves with SBP are primarily made up of loans and deposits made to the federal government of Pakistan (inflows) and loan repayments and interest payments (outflow). Because Pakistan is usually a net borrower, our reserves with the SBP are usually insufficient, hence the need to borrow more to settle existing liabilities i.e. a debt trap.

commerce ministry can work. And as evident from the example, a lot needs to be just right for such deals to be executed effectively. No wonder then that the joint secretary at the commerce ministry said that the import and export of goods in exchange for goods is “quite difficult”!

To begin with, even though multi-commodity traders will be involved in the process, they will be hard pressed to locate a similar trader from another

country who is in the market for what the former is selling. This would be a universal problem for traders in all three countries.

What may happen as a result of this search for ‘buyers across borders’ is the inclusion of more than one middleman within each deal. This will almost certainly lead to squeezed margins and perhaps as a result, the deals may not remain as profitable for the middlemen. Volume of barter trade would reduce as a consequence and not contribute enough to trade to remain sustainable.

There is also some ambiguity over the scale and what sort of importers and exporters

Milk, Cream, Eggs, and Cereals

Meat and Fish products

Fruits and Vegetables

Rice

Confectionery and Bakery items

Salt

Pharmaceutical products

Essential Oils, Perfumes, Cosmetics, Toiletries, Soaps, Lubricants, Waxes, and Matches

Tanning, Dyeing Extracts, and Miscellaneous Chemicals products

Plastics and Rubber Articles

Finished Leather & Leather Apparel

Articles of Wood

Articles of Paper & Paper Board

Textiles (Intermediates)

Readymade Garments, Textile's Made-ups, and Carpets

Footwear

Iron and Steel

Copper and Articles thereof

Aluminum and article thereof

Tool and Cutlery

Electric Fans and Home Appliances

Electrical equipment

Motorcycles and Tractors (excluding components)

Surgical Instruments

Furniture Items

Sports Goods

the government has kept in mind when preparing this multilateral trade policy. According to Qureshi, the barter trade agreement is mainly designed or proposed for those doing small trade at borders or already involved in business across the border (of the elected countries).

On the other hand Minister of State Musadik Malik is on record stating that “oil purchases could rise to 100,000 barrels per day (bpd) if the first transaction goes smoothly”.

Keeping aside the clear confusion and ambiguity within the commerce ministry over who the BTA is targeted at for a second; there are technical problems with both statements.

Why would small traders already engaged in trading, presumably falling under the informal trade category, be interested in barter trade that brings them within the formal economy? Why would they disrupt relationships built over years of doing business with these countries to participate in a move that is fundamentally a bandaid over a gunshot wound for a government that keeps shooting itself? It would also not make much sense for most of these smaller traders to change their entire system of trading with currency without seeing any tangible benefit in switching to barter trade.

As for Mr Musadik’s anticipation of ‘100,000 bpd’, things become a lot more complicated when dealing with larger ticket items such as oil and petroleum products. What Pakistan has on offer to exchange is much cheaper in dollar terms and therefore a lot more of it will have to be exported. Additionally, Russia would be under no obligation to trade oil under a barter system if Pakistan is a willing buyer. They would much prefer to go through conventional channels, similar to how Russian oil was imported last month.

As per Qureshi, an exercise to educate various traders, exporters and importers is still underway, even though the SRO has been issued. Clearly, this step should have been completed before the launch of the barter trade option.

But it seems even those meant to educate the traders are unaware of how this type of trading will work effectively at the level of importers and exporters.

One concern that arises from such trade is the shortage of goods domestically. In an attempt to trade eggs, wheat and sugar for oil, won’t Pakistan face a domestic shortage as a lot more of the former will have to be exported to import the latter?

That’s what quotas are for. Right? But

The 10 items to be imported from Afghanistan are included:

Fruits and Nuts

Vegetables and Pulses

Those Items to be imported from Iran included:

Fruits, Nuts, and Vegetables

Spices

Spices

Oil Seeds

Minerals and Metals

Coal and its Products

Raw Rubber Items

Raw Hides and Skins

Cotton

Iron & Steel

surprisingly, according to Qureshi there is currently no limit or quota fixed for the import and export of agricultural items under the barter agreement. He added however that if a domestic supply issue arises the relevant authorities may restrict and impose a ban on such goods in the same way the government practices in existing normal trade.

Pakistan is already prone to domestic supply issues owing to various reasons. The sugar and wheat crises under the PTI government were a direct result of too much of both commodities being exported. Is it not unwise to create additional avenues for such shortages to spring up and, as per the joint secretary’s statement, ‘deal with it later’?

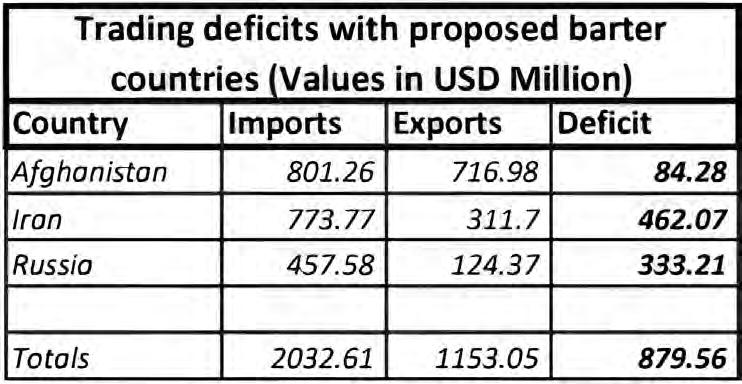

Pakistan runs a trade deficit with all three countries proposed in the barter trade agreement. As of FY 2022, Pakistan runs a $84.8 million trade deficit with Afghanistan, $462 million deficit with Iran (export figure based on Iran custom’s data) and a $333.2 million deficit with Russia.

Minerals & Metals

Coal and its Products, Petroleum

Miscellaneous Chemical Products

Fertilizers

Articles of Plastics and Rubber

Raw Hides and Skins

Raw Wool

Articles of Iron & Steel

Barter trade would not improve these figures as in every deal under the agreement, an equal dollar value of exports and imports would be taking place; there would be no new imbalances being created.

This is beneficial and preferable to free trade agreements (FTA) that Pakistan has previously had with countries like China for example. Being a net importer of most goods and services, under FTAs Pakistan tends to import more than it can export, creating a greater outflow of precious foreign exchange reserves and creating greater deficits with trading partners.

The BTA would help in maintaining the deficits at their current levels while continuing trade. However, the primary issue still remains; it does not seem to be implementable on the scale that would be as beneficial as being marketed.

There is more clarity on the customs front since this element of trade is not particularly associated or involved in the technicalities of how goods are bought and sold between trading TEXTILES

There would be 11 items identified to import from Russia under the barter system:

Pulses

Wheat

Coal & its Products, Petroleum Oils (including Crude), LNG and LPG

Fertilizer

Tanning and Dying Extracts

Articles of Plastics and Rubber (In primary form)

Minerals and Metals

WeBOC is a web-based computerized clearance system, providing automated customs clearance of imports. It is a portal through which the Customs valuations of various goods and services can be determined based on historical data of invoices being posted there by importers. These valuations change according to data to remain valid and current.

The same valuations and procedures will be used to determine the duty to be charged on goods being traded under the BTA as with conventional trade. As per multiple customs officials who spoke with Profit on the matter, customs officers present at the borders will calculate and determine the payable duty.

Articles of Wood & Paper

As per the SRO, any export and import good valuations differing from the WeBOC system values will be allowed a ‘onetime tolerance’ of 20 percent.

Chemicals Products

ters news report from May of this year, Pakistan Petroleum Dealers Association (PPDA) claims that 35% of diesel sold in Pakistan had arrived illegally from Iran.

The same report mentioned that the federal energy ministry had asked security forces to clamp down on fuel smuggling from Iran as diesel sales had slumped “more than 40%” due to smuggled products.

This practice will continue unless a strict top-down crackdown takes place. According to Ministry of Commerce officials barter trade would enhance existing smuggling from these countries, especially from Iran, Afghanistan. This makes sense as anyone already thriving in the smuggling business, as is the case with Iranian oil at least, will not delve into a well-monitored system of trade looking for more innovative ways to smuggle more.

While the barter trade agreement signed by Pakistan with Iran, Afghanistan, and Russia aims to address economic challenges and foster closer ties, it is evident that this agreement has significant procedural issues that need to be addressed before any deals can take place. Problems that will prop up once a basic understandable and workable mechanism is in place are also serious in nature and plenty.

The potential risks associated with such arrangements, including the complexities of non-monetary exchanges and the effort and resources that have already and will be put in to execute such an undertaking in the future, highlight the importance of conducting a thorough review and further analysis of this agreement.

Articles of Iron and Steel

Items of Textile Industrial Machinery

parties and will be following already established and defined procedures.

According to the SRO issued for the BTA the procedure for assessing the valuation of the products is defined as ‘the assessed value of goods used to calculate the monetary limit of the authorization, ensuring compliance. ‘Import and export values should not exceed the authorized monetary value entered in the WeBOC system.’

Speaking to Profit Member Customs Operations Mukarram Jah Ansari clarified that the general proposed process in barter trade to first import and then export up to the value already imported. However, if at some point, the value of export is greater than import, then flexibility of up to 20% would be allowed on a one time basis.

The BTA is unlikely to resolve or add to the smuggling at borders. Iran, which is part of the B2B barter trade agreement, is involved in massive smuggling of oil into Pakistan. As per a Reu-

It is crucial for policymakers and stakeholders to address these drawbacks, identify potential solutions, and ensure that the barter trade arrangement can be sustained in a manner that is beneficial to long-term economic stability. And if such a possibility does not exist, going forward with it just for the sake of it would be ill-advised. Bilateral trade of this nature does not take long to evolve into full-blown diplomatic issues that can also lead to international litigation. Such an outcome would be most unfortunate and costly.

On the face of it, it sounds like a good idea. But in modern economic times with well-developed IT based trading systems in place, the case for a barter system is very weak. It seems like more of a political gimmick for a cash-strapped net-importer like Pakistan to stave off some of the attention and pressures of being responsible for a failing economy than an actual solution to serious problems. n

This year’s budget was presented under tense circumstances. With an IMF deal still not secured and political turmoil reaching a boiling point there was little on anybody’s mind except what measures the budget would impose and whether it would manage to steer Pakistan away from default.

Yet outside of this immediate concern, one of the most prevalent conversations taking place at the Prime Minister’s office and within cabinet was the question of the country’s agriculture. As an agrarian economy, Pakistan has long relied on the fact that it is capable of producing enough food to fulfil the caloric requirements of its own population, and then have enough leftover to be an exporter.

Historically this has been true. It also means that no matter what happens the country’s population can reasonably be fed and taken care of without any reliance on imports — at least that is theoretically correct. Over

the past few years, the country has emerged as a net importer of food.

Which is why in a major huddle before the budget that took place on the 1st of June, the prime minister vowed to give priority to the agriculture sector by offering incentives to growers to improve production and rural economy. The talking points were the same as always — better subsidies, better support prices, and more assistance from the government.

That, of course, is well and good. However, subsidies and support prices are short term solutions that temporarily boost agriculture in the country. These are the same solutions and promises that have been made before earlier budgets too.

The reality is that agriculture is the largest real sector of the economy and one of our most major products. A concentrated effort is required to make it bigger, better, more profitable, and export oriented. So what does this year’s budget look like for the agriculture sector? In short it looks like things will stay much as they have in years past.

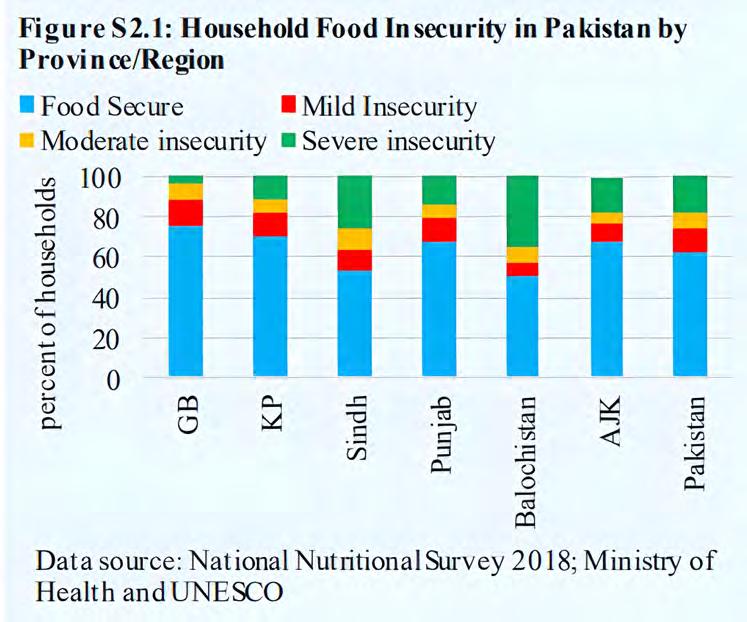

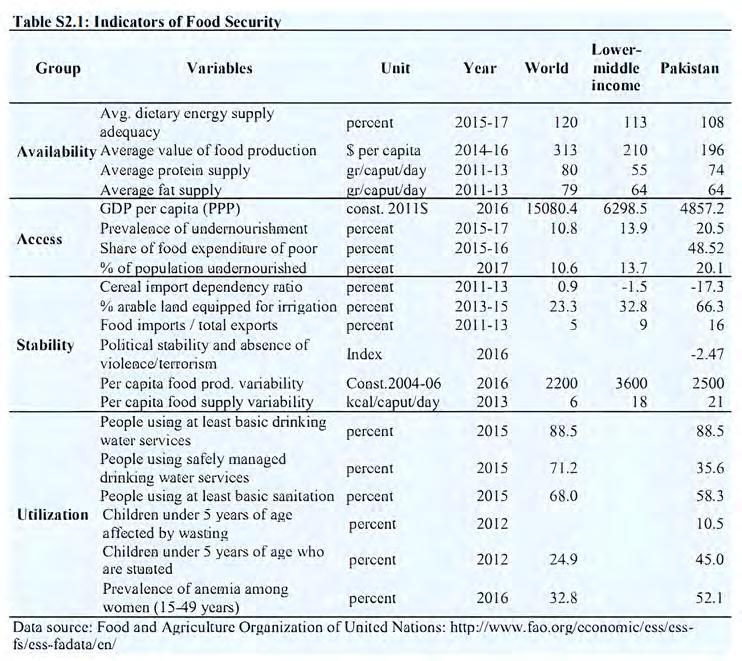

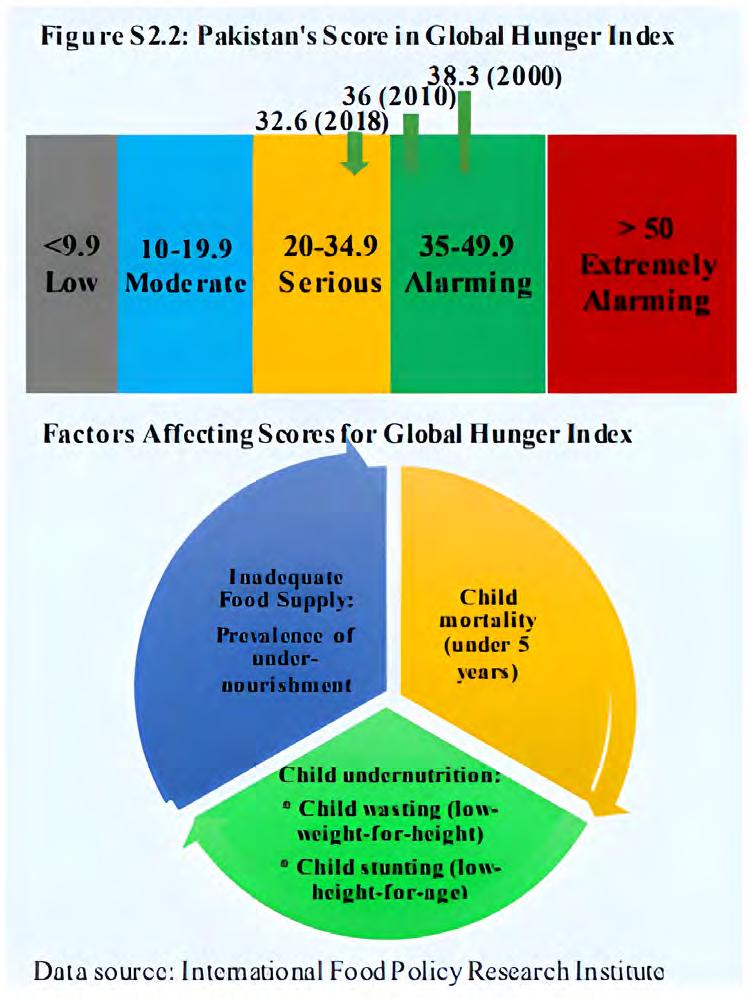

Food security is possibly one of the biggest problems facing Pakistan right now. n an international ranking of the Global Hunger Index (GHI) this year, the country ranked 92 out of 116 nations, with its hunger categorised as ‘serious.’ Pakistan currently faces a scenario in which it is largely food sufficient but not food secure.

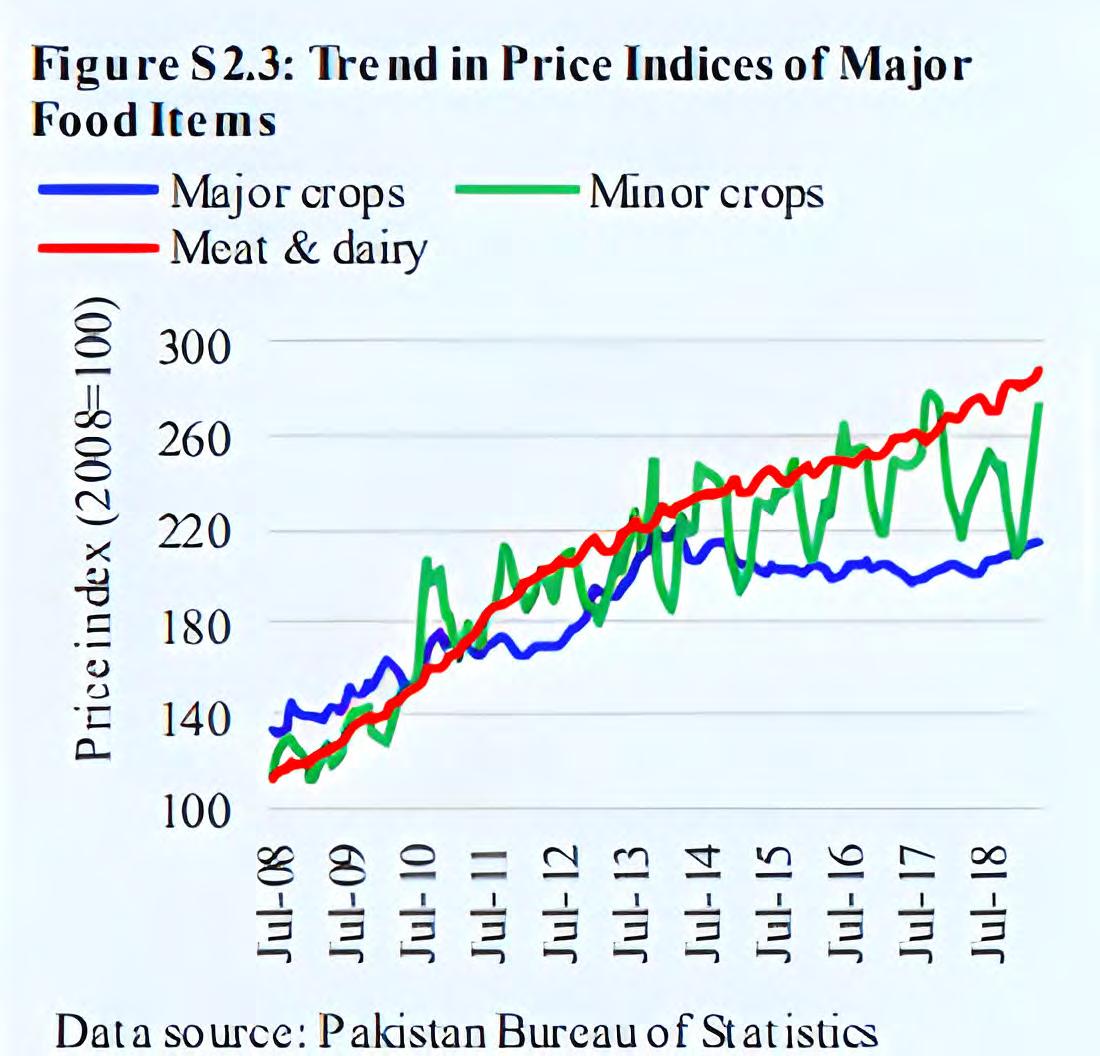

Despite Pakistan being ranked 8th in producing wheat, 10th in rice, 5th in sugarcane, and 4th in milk production, a 2019 report of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) showed that nearly 37% of households in Pakistan are food insecure. In the four years since the SBP’s report, matters have only worsened. Food price inflation in Pakistan has been in double digits since August 2019. The cost of food has been 10.4-19.5% higher than the previous year in urban areas and 12.6-23.8% in rural areas, according to figures published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

Subsidies and support prices are well and good, but the agriculture sector needs a dedicated effort to pull it out of its misery

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the concept of food security is flexible, but is widely believed to “exist when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

In short, for a country to be considered food sufficient it does not just have to produce a sufficient amount of food, but that food should be easily available, affordable, and of a quality that meets basic nutritional requirements. For a reliable level of food security, it is vital that the access and affordability of food is not affected by shock events such as floods and economic crises that result in inflation.

The concept is not difficult to grasp, but it is so simple that it often gets lost in the cracks. Food is the most basic building block of human life. The quality and quantity of caloric intake of a population affects its overall productivity, standard of living, and most importantly happiness and satisfaction.

While access to food is a basic, fundamental human right there is a way to put an economic cost on food insecurity. The lack of food security has strong economic implications. According to a special section of the SBP’s annual report from 2019-20, the state of food security has strong linkages with the state of human capital in the country. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the

United Nations has also estimated that a high rate of malnutrition can cost an economy around 3-4% of GDP. In the case of Pakistan, estimates suggest that malnutrition and its outcomes cost the economy 3% of GDP (US$

7.6 billion) every year.

To put this in very mathematical terms, malnutrition and food insecurity manifests in the shape of high child mortality rates, prevalence of zinc and iodine deficiencies, stunting, and anaemia, which lead to deficits in physical and mental development that weakens labour productivity and loss of future labour force in the country.

On a much more human level, however, the lack of food security means a whole lot of misery, hunger, and anguish. According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report for 2020, prevalence of undernourishment in Pakistan is 12.3% and an estimated 26 million people in Pakistan are undernourished or food-insecure. Pakistan’s children have suffered and are continuing to suffer. Malnutrition from an early age results in consequences that last entire lifetimes.

Add on top of that a high population growth and unfavourable water and climatic conditions and you have a scenario that threatens to spill over and cause mayhem. Pakistan is barely maintaining its current food security level of just over 60%. According to the SBP report mentioned earlier, “of the 36.9 percent of the households in Pakistan labelled as “food insecure”, 18.3 percent face “severe” food insecurity.” Concerns over food security may increase at an alarming rate over the next two or three decades. This will also mean that the overall fiscal and balance-of-payments cost will also escalate just to maintain the current level of food security in the country.

There are of course reasons behind this. So how does a country with one of the largest agrarian economies in the world find itself unable to sufficiently provide food for nearly 40% of its population? For decades, agriculture has been neglected and people’s earnings have been hit by one economic crisis after another. On top of this, particularly in the past decade or so, climate change related disasters and changes in the environment have resulted in our already neglected agriculture becoming less competitive.

One of the most important things to understand is that as the world’s population has grown, more land has had to be brought under cultivation to meet humanity’s caloric needs. And as the world has progressed, this has required a serious scientific approach. Research in the field of agriculture has led to mechanisation of farms, the development of seeds that give higher yields and are more resistant to different weather conditions, and areas before thought uncultivable have been turned into rich sources of food. The primary role of agricultural research is to heighten knowledge and improve technology. It heightens understanding of the interactions and interdependence between production systems and farming communities. This requires a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to problem identification, analysis and solution-finding.

This has been entirely missing in Pakistan. A major reason for the food price inflation in recent times are increasing input costs for agriculture over the past two years. Higher fuel prices and the devaluation of the rupee have led to a rise in costs in both fertiliser and seeds. Prices increase more in rural areas

because commodities are diverted to cities due to higher profit margins, and because of the higher cost of imported items such as pulses and cooking oil.

On top of this, land is disproportionately owned in the country. This has led to a vast misutilization of the subsidies and support prices that the government very regularly

offers. On top of this, the effects of climate change have been devastatingly clear.

According to UNESCAP, Pakistan could lose more than 9% of its annual GDP due to climate change. Severe heat waves and untimely rains have also severely impacted Pakistan’s agricultural production. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that the frequency of such extreme weather conditions will increase in the future, causing a severe risk to Pakistan’s food security. The Asian Development Bank projects sharp declines in key food and cash crops (such as wheat, sugarcane, rice, maize, and cotton) in the coming years due to rising cultivating costs and climate change.

The 2023-24 budget really doesn’t do much to solve any of these deep rooted issues. The federal government has allocated Rs21 billion in the budget for 2022-23 under a three-year Growth Strategy for improving the output of crops and livestock, countering climate change impact, promoting smart agriculture, value-addition and agro-processing. It has also announced Rs11bn for the provision of the latest machin-

ery, laser land-levellers and quality seeds for the agriculture sector and enhancing exports of farm produce.

In terms of relief, the government has abolished sales tax on tractors, other agriculture tools as well as seeds and has made customs duty zero on import of agricultural tools, irrigation systems, harvesting machines, greenhouse farming and for agro-based industries.

It has increased subsidies for fertiliser plants from Rs6bn in the outgoing year to Rs15bn for the year 2022-23, a 150pc hike. A separate allocation of Rs6.0bn has been made as a subsidy for urea compost import. The government has apportioned Rs10bn for agriculture relief initiatives without giving any details in the budget documents.

Among the steps announced by Finance Minister Ishaq Dar on Friday is a significantly large increase in loans for farmers — from Rs1.8tr Rs2.2tr — the allocation of Rs50bn to shift 50,000 tube wells to solar power, the withdrawal of duties on seed import, and duty exemption on the import of combine harvesters.

The talking points have all been the same as well. The government promised to ensure direct provision of subsidy to farmers on fertilisers, timely loans, and direct support prices. However, the measures must go beyond years. Last year when the prime minister had just come into power, his response to the catastrophic floods in the country had been announcing the Kissan Subsidy Package.

Under the package, the government will give Rs10.6 billion loans to small farmers across the country while small farmers of flood-hit areas would get loans worth Rs 80 billion. In addition to the interest-free and subsidised loans, subsidies will also be given on farm imports such as fertilisers, electricity, seeds, and even tractors.

This was necessary in the face of devastation. If implemented correctly, packages such as this have a wide-reaching impact in helping farmers affected by this year’s floods back on their feet. But that is as far as they can and should go. The scale of the problem faced by our agricultural sector will not be fixed by any subsidy package. At most, any subsidy will provide temporary relief. For too long the state has allowed the country’s agriculture to suffer and have offered only stop-gap solutions such as subsidy packaged. We have been papering over the cracks for so long that our entire agrarian economy has grown dependent on subsidy packages.

For decades Pakistan has been falling behind on agricultural competitiveness. While the rest of the world has developed through research, mechanisation, and technological advancements we have lagged behind. On top of that now our farmers are facing the harsh and unpredictable realities of climate change.

Pakistan’s own neighbours like China and India have managed to specialise in certain crops and become the leading producers of those crops in the entire world. Meanwhile Pakistan has lost its edge in the global markets. Simply take a look at our cotton production as an example. Between 2015 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined by nearly 35%, from nearly 14 million bales in 2015 to just over 9 million bales in 2020.

And while our cotton production and quality have gone down, countries like Egypt have used the latest genetically modified seeds to get more yield per area with better quality fibres as well. At the same time, they have also industrialised and set-up the processing of these crops domestically. With no focus on value-addition or research, Pakistan’s agriculture is down and out for the count on many

fronts. For almost all of our major produce, we have low crop yields, soil infertility, outdated farm practices, and extremely low mechanisation. Already dogged by these problems, our beleaguered farmers now face a serious threat from climate change as well. Weather patterns are wild and erratic, going from drought to flood within a matter of months.

If Pakistan is to move forward on the agricultural front, which it must if it wants to maintain food security, we will have to shift our focus from subsidies to actual research and development. Agriculture is still the largest component of our economy, and fixing it will take persistent, daily, dedicated, single-minded focus. It is the need of the hour, and with the effects of climate change knocking on our doors there has never been a more urgent moment in time to try and fix it. n

The last few years have experienced a rise in magic and mysticism in Pakistan’s political landscape with election results and policy decisions allegedly reliant on wizardry and spellwork. However, the recent announcement of the Federal Budget of 2023-24 depicted an unorthodox version of political sorcery when a financial document that was meant to aid Pakistan’s economic development magically turned into a proclamation of friendship.

On June 9th, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar presented the Federal Budget for FY 2023. Amongst other things, the budget included abolishing the 2% final tax on the purchase of immovable property for overseas Pakistanis with the intent to boost remittances through formal channels amid dwindling foreign exchange reserves and a potential default situation. To investigate the validity of this clause, we spoke with Dr. Ali Hasnain, Head of the Economics Department at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, and Dr. Ikram Ul Haq, an international tax lawyer and contributor to the International Bureau of Fiscal Documentations (IBFD). So far unrigged, the results are heavily in opposition to the government.

The government has removed a final tax on overseas real estate investors. Will it create more problems than it is meant to solve?

It is undeniably true that Pakistan’s current economic situation is terrible.

It is also true that our foreign exchange reserves have almost entirely run out, which, as highlighted by the aforementioned exemption clause, must be solved. Unfortunately, this acknowledgement is the limit to the clause’s usefulness for our economy.

The reality is that Pakistan has an import to GDP ratio of about 17 percent which is surprisingly in the same ballpark as India and Bangladesh. The damage lies in the ratio of exports of goods and services to GDP which for India stands at over 21.4 percent whereas for Pakistan only a little over a concerning figure of 9 percent. This becomes even more alarming with the realization that the size of Pakistan’s entire economy is $370 billion USD while our external debt is close to around $121.75 billion USD. This could have been less of a problem if Pakistan’s economy was not expanding at a leisurely annual rate of 0.3% (from June 2022 to July 2023).

Dr. Ali Hasnain was thus able to highlight that there are two solutions to this magnanimous problem: first, increase Pakistan’s export-capacity and second, increase foreign direct investments in the country. Interestingly, by encouraging investments in real-estate,

an unproductive sector of the economy, removing the 2% final tax on immovable property achieves neither of the two.

To understand the solutions suggested by Dr. Hasnain, it is integral to first understand the basis of our economic conundrum. Why is Pakistan a dollar-poor economy?

“This is a slightly complicated conversation because in order to deal with the balance of payment constraints, we often have to take decisions that damage long term growth rates. For instance, Gonzalo Verala says Pakistan has an anti-export-bias, well I say we also have an anti-expert-bias.” The Economist further adds, “The problem is that Pakistan has tried to artificially keep the dollar cheaper whenever it could manage to do so, sustaining a huge trade deficit and suffering long term exchange rate explosions…”

And so, overtime, Pakistan has accustomed its elite to build their interests around cheaper US dollars. Therefore, as the dollar value decreases, the purchasing power of the elite increases which in turn sustains import positive policies.

But how is this linked to the 2% final tax

exemption?

This is because the exemption doubles up on precisely the strategy that has landed us here. The real-estate sector is a sector that adds little to no stimulus to the economy, and is heavily import reliant, which means that it does not help create dollars for a dollar-poor country, but instead absorbs huge amounts of foreign reserves. Simply put, construction materials for real estate are rarely domestically produced, therefore, this exemption shifts our industrial posture further away from import substitution.

“If you are an investor, to join an export-led business you must be a tax compliant citizen ready to face the legal hindrances put forward to disincentivize exports. On the other hand, the real estate sector does not even require official receipts, let alone tax filing investors. It is also a sector in which the government has successfully diminished competition and entry barriers.”, added Hasnain.

Therefore, the repercussions of another tax exemption are huge. In the past, they have signaled to Pakistan’s industrialists that they no longer need to create speculative bubbles on their lands running risky yet productive industries, but that they should rather focus on real estate development. Packages Mall built on factory land in Lahore is a prime example of this. Currently, these exemptions signal to overseas investors that Pakistan’s businesses and other financial assets, except for the real estate sector, are useless to invest in. They also signal to local residents that the real estate sector is a viable investment.

Zaidi, former Chairman of the Federal Board of Revenue, being asked by then Chief of Army Staff, Gen Bajwa, to discourage real estate taxations.

Up until last year’s pre-budget meetings, current prime minister Shehbaz Sharif exclaimed that the real estate sector was unproductive and therefore, should be taxed more in order to disincentivize its investments. What changes have been made since, again, can only be speculated.

Nonetheless, Mancur Olson’s logic of collective action comes to mind wherein he says that the losses of some things are diffused in small quantities to the whole society and the benefits are flooded to only a few individuals. Yet, despite the net losses being more than the benefits, since they are diffused, there is little political salience and action.

him. “The amount of investments that this exemption will bring depends entirely on the amount of black money Pakistanis want to turn into white money.”

In a debilitated economy with hyperinflation and severe devaluation, Dr. Haq raises a pertinent question as to why overseas investors would want to invest money in Pakistan’s land? Not only that, but repatriating money for overseas investors from real estate property has become increasingly difficult. With both these factors in question, it seems unlikely that this clause in the federal budget will bring in the dollars to Pakistan’s foreign reserves that Ishaq Dar expects.

Mohammad Shabbar

One aspect of this answer is purely speculative. The speculation, however, rests strongly on precedents, such as Syed

This is perhaps the most important segment of this entire discussion.

Dr. Ikram Ul Haq explained it plainly when we reached out to

On the other hand, Dr. Haq predicts that there is no such expectation in the first place. Similar to the proposed provisions in the Finance Bill earlier this year to allow $100,000 to be brought into the country without disclosing the source of income, he said this clause is purely an effort to re-route illegal or non-taxable income of Pakistanis from abroad. This is interesting because it also enables the current government to present this recycled income as positive “investments” under their new policy.

However, beyond the evident problems with this exemption, which is that it validates and strengthens the positions of the rich and the landed elite, it may also create speculations within bigger international players like the IMF and the FATF. By entitling potential black money as remittances coming into the country, the FBR may not have the opportunity to gather relevant information related to the transactions that happen under this clause.

Conclusively, the consistent formulation and implementation of policies by the government that are explicitly against Pakistan’s economic requirements is the equivalent of a first aid worker further suffocating a dying patient instead of resuscitating him. n

“The problem is that Pakistan has tried to artificially keep the dollar cheaper whenever it could manage to do so, sustaining a huge trade deficit and suffering long term exchange rate explosions

Dr. Ali Hasnain, Head of the Economics Department at LUMS

The amount of investments that this exemption will bring depends entirely on the amount of black money Pakistanis want to turn into white money

Dr. Ikram Ul Haq, International tax lawyer

Shahzada Dawood, a British Pakistani businessman from the affluent Dawood family was among the five people aboard a submersible diving deep into the Atlantic to view the Titanic. In a tragic turn of events, the vessel imploded during its descent to the ocean floor, authorities said on 22 June. Shahzada Dawood was 48. And he was not alone. Shahzada was accompanied by his 19-year-old son, Suleman who also passed away as the submersible imploded.

Shahzada Dawood was the Vice Chairman of Engro Corporation, a business conglomerate based in Karachi, renowned for its businesses in agriculture, energy and telecommunications. The Dawood family is recognised as one of Pakistan’s wealthiest business families. Shahzada Dawood’s work focused on renewable energy and technology.

Shahzada Dawood was born on 12 February, 1975, in Rawalpindi. He studied Law as an undergraduate at Buckingham University in Britain and later received a master’s degree in global textile marketing from Philadelphia Univer-

sity, now part of the Thomas Jefferson University. In 2012, he was named a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum. In December 2020, he also joined the Board of Trustees of the SETI Institute, an organisation devoted to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

His son was a business student at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow and had just completed his first year. Like his father, he was a fan of science fiction and enjoyed solving Rubik’s Cubes and playing volleyball, according to a statement from Engro.

Mr. Dawood is survived by a daughter, Alina, and his wife, Christine.

The most prominent attribute of Shahzada Dawood was his innate spirit of curiosity and an unrelenting desire to learn about the world and its mysteries. According to a close friend of Shahzada Dawood, “He would make a daily call at 3 pm,

which was 10 am in the UK where he was based. In this call, the family would discuss mysteries of the universe. Questions such as why Black Holes appear, would dominate the discussions. There would hardly be talk about work in these calls. Shahzada always encouraged us to expand our minds and be more perceptive as human beings.”

The journey to the Titanic was also reflective of Shahzada’s spirit of curiosity and adventure. Hussain Dawood, father of Shahzada and grand-father of Suleman said, “Both of them were so excited to see the Titanic. This is a pure exhibition of Shahzada’s high spirit of exploration.”

“We had a beautiful holiday in Lithuania, and were looking at the pictures this morning, remembering all the beautiful interactions we had shared,” Hussain Dawood recollected during the memorial. “Shahzada was all about experiencing life. He had been to Antarctica and he wished for his parents to visit there as well. Both Shahzada and Suleman had convinced us to accompany them to Antarctica this year. This exploratory side of them we cherish the most,” he continued.

Shahzada Dawood’s Instagram profile is like a memory book of his love of travel and nature; it is inundated with photos of birds, flowers and landscapes, including a sunset in the Kalahari Desert, the ice sheet in Greenland, penguins in the Shetlands and a tiny bird in London with the caption “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.”

Another salient aspect of his personality was his empathy. According to close friends and family, Shahzada always stepped in at times of crisis and looked after the emotional well-being of those around him. His friend added, “Shahzada expressed a genuine concern for the people around him. He always emphasised the assessment of impact on people, whether this was related to business or learning in general.”

This was central to his conduct as the Vice Chairman of ENGRO as well. His friend reminisced, “He was never a boss, but a friend to the people who worked around him. And he always had a knack of making people happy and excited about the things that he was interested in.”

“Because of Shahzada’s self discipline and his passion to contribute to the society, he proved himself to be a leader. This came from the humility he had, when he interacted with colleagues and family,” added Hussain Dawood.

In his role at Engro, the company statement said, Mr. Dawood advocated “a culture of learning, sustainability and diversity.” He was also involved in his family’s charitable ventures, including the Engro Foundation, which supports small-scale farmers, and the Dawood Foundation, an education-focused nonprofit.

Above all, Shahzada was known to be a family man. In his memorial, his friend shared that Shahzada would always be in a rush to return home to his family. He had profound love and respect for his parents. Amongst nephews and nieces, he was popular as the “cool uncle.” He also had deep pride and fondness for his two children, Suleman Dawood and Alina Dawood.

“The character they (Shahzada and Suleman) displayed, the elegance of their personalities, their good manners, my God! Any family that has this will realise we had the best,” Suleman Dawood said. “Shahzada prioritised the wishes of his parents. He never upset us, and never brought any shade of unhappiness.”

Suleman Dawood was also known to be “operating at a level much ahead of his age.” A seamless mix of intellect and vulnerability made him highly endearing to the people he would interact with.

Christina, Shahzada’s wife and Suleman’s mother, also shared some heartwarming stories about the deceased. “The first time I met Shahzada was in 2000 at a university barbecue. It was loud and smoky, so both of us had stepped out to get some fresh air. I was highly drawn by his curiosity. He wanted to know everything about Germany from a German. I had no idea about Pakistan at the time, but this changed soon after. Two years later, we got married in Lahore. Shahzada was so grumpy that day because he hated being the centre of attention. Yet, he braved through and developed his “shaadi” smile, which was basically a fake smile,” smiled Christina.

“When Suleman was born, Shahzada waited in the corner while the family cooed and fussed over the baby. But when he held the baby, his eyes expressed that he had found a long lost companion,” Christina recounted.

“Suleman was an old soul. When he was four years old, we went for a holiday in Malaysia. I was resting because of an upset stomach. Suleman kissed me, then dug through his toy box, placed toys randomly over my body. Then he looked at his handiwork with his tongue sticking out and gleefully announced, “mama, you’re fine now.”

Basically, he had placed toys on all the chakras, and I was floored by his generosity and intelligence,” Christina reminisced.

“As the children grew older, Shahzada became younger. He walked our children through the garden and explained nature to them- soil, bugs, flowers, everything. Our children loved sitting around him, discussing everything into depth,” she continued.

Mufti Menk, a renowned Islamic scholar was invited to pray for the departed souls at the memorial. Menk prayed, “On this day of Arafah, we have gathered to engage in prayer. I will seize this beautiful opportunity to mention that I have lost a brother and a son, and I felt it the moment that it occurred. Yet, I asked Allah to give me the ability to accept what happened and moved on. Good and bad, faith and destiny, everything is in the hands of Allah. We should realise this and endure such losses with patience. The deceased will be happy to see that we have accepted the decree of the Almighty.”

“This is the plan of the Almighty. We come on to the earth and leave. Death is painful because we miss the deceased souls. But we must ask the Almighty to help us overcome the pain and support each other in times of grief and despair,” he continued.

“Many times, we are told that we have a family that really is just a gift from the Creator, and He has a right to take the gift back whenever He wants. The real challenge comes when one actually experiences this. Can one truly accept this, the will of the Creator? That will be my struggle,” grieved Hussain Dawood.

“Shahzada’s favourite sentence was “fighting na karo, love karo.” That is exactly how we were as a family. We spent our lives loving each other, and being curious about life, nature and its many mysteries. In this spirit, these two best friends embarked on their last voyage. These past few days have been incredibly challenging for our family. Emotions shifted from shock to hope, to finally despair and grief. In the time to come, your tremendous support and love will help mend my broken heart a little bit. In the meanwhile, please remember to pray for Shahzada and Suleman, and the souls lost with them too,” sighed Christina.

As the memorial neared its end, Shahzada’s friend sighed, “I will miss Shahzada- the darwaish, the malang, the bohemian visionary and above all- my friend.” n

Electricity tariffs for lifeline customers have increased by 70 percent over the last five years. During the same period, electricity consumption per capita across the board has largely remained flat at 650 units. Increase in electricity prices has effectively led to a scenario where consumption has stayed flat, as electricity is simply not affordable for households. On the flip side, the government has spent more than a trillion rupees in energy subsidies, further deepening an already precarious budget deficit.

An increase in electricity consumption per capita is a leading indicator of a prospering society. A scenario where consumption has stayed flat suggests that incomes have stagnated across the board. An increase in electricity prices further discourages any electricity consumption as price elasticity of demand is kicked into action.

Lifeline consumers are defined as households that consume up to 200 units (kilowatt-hours) of electricity. Most subsidies provided by the government are used to support these lifeline households. However, despite the subsidies, an inefficient transmission and distribution infrastructure often leads to a scenario where these households are disproportionately affected by power outages, through load shedding. As energy consumption is partially dependent on imported energy, inability of the government to import energy leads to a scenario where there are power outages, despite availability of surplus capacity.

It is estimated that roughly 55 percent of residential consumers in the country are lifeline consumers. It is entirely possible to shift consumption of some of these households towards solar. It is possible to make these households producers of electricity, who can consume the electricity they generate, while selling surplus electricity to the grid. This can effectively result in creation of mini-grids, wherein rooftop solar installations in an area can pool together to sell electricity to the grid, effectively netting it off against their consumption.

For example, in the case of Punjab, there are roughly 10.7 million households that can be categorized as lifeline consumers, from a total of 18.6 million households as per data from 2021. Assuming prevailing costs

of solar systems, even if all households (which is not possible) opt for such a scheme, a 25 percent down payment that the government can fund would still be less than the amount of energy subsidy allocated on an annual basis for supporting lifeline consumers.

Currently, rooftop solar is mostly used by affluent households who have the necessary upfront capital required for installation. Instead of doling out annual subsidies, a case can be made here that the government facilitates financing of rooftop solar for lifeline consumers at concessional, or preferential rates. It is estimated that a lifeline consumer can partially meet its requirements with a 1 or 2 kilowatt solar system, depending on its historic consumption. Assuming a down payment of 20 percent to get access to the equipment, the government can pitch in half of the same, while half can be pitched in by the household. The remaining amount can be financed by a financial institution at a concessional rate, such that the monthly payment associated with the equipment largely aligns with the monthly electricity bill of the household.

This can ensure that the monthly bill actually stays predictable, and can be adjusted as the household produces electricity, and sells to the grid. Furthermore, within a few years, the household can fully pay off the solar installation, massively benefiting through increased disposable income. Moreover, this reallocates existing subsidy allocation to capital investment that can sustainably generate renewable electricity while significantly benefiting households in terms of better cash flow management, and uninterrupted access to electricity.

Electricity distribution companies can play a pivotal role here. Each electricity distribution company knows precisely what consumption of a particular household is, and its repayment behavior. Through availability of consumption, and repayment metrics, it can do credit assessment of existing households. On the basis of credit assessment, financing can be extended to eligible households.

Before such an ambitious scheme can be rolled out, it will be essential to upgrade the distribution infrastructure of the electricity distribution companies that continue to suffer due to operational inefficiencies, and heavy losses. A transfer of distribution companies to provinces, can potentially trigger development of a provincial solarization scheme.

Rooftop solarization is an ambitious plan, but something that has been successfully executed in many other jurisdictions. Existing pool of subsidies can be reallocated to create a more stable, low-cost, and renewable source of energy for the most vulnerable households. This will certainly require heavy investment in grid infrastructure, but the potential economic and social divide the scheme can generate can potentially far outweigh financial costs that are already being incurred in the form of blanket energy subsidies. To serve the people, the government can either take an easier inefficient way out, or reallocate capital in a manner that enhances welfare of households across the board. n

Two cousins, Imran Wazir, 23, and Abdul Salam, 25, declared to their families that they had decided to leave their village in northeastern Pakistan and pay an exorbitant sum of money to smugglers to reach Europe. According to relatives, they felt deprived of viable options at home.

Mr. Wazir had felt increasingly burdened as the family’s breadwinner, and Mr. Salam had practically been attached to his cousin’s hip since childhood. Late one night in

Excruciating poverty at homes leaves people with little choice, and sometimes they risk their lives in search of greener pastures abroad

The working conditions are tough here also. Most people want to get public jobs. However, only 8-10% are able to acquire those. What do the remaining 90% do? If they have access to foreign jobs, that’s actually a huge plus. I would see it

Taimur Jhagra, Former KP Finance Minister

March, they bid farewell to their families and embarked on this arduous, seemingly endless journey through land, air and sea across four countries, in the hopes of reaching their destination.

According to a New York Times article by Christina Goldbaum, Mr. Wazir and Mr. Salam were two of the 104 Pakistanis who met their demise when a fishing boat, inundated with nearly 750 migrants capsized in the Mediterranean last month. The ship that capsized, Adriana, had set sail from eastern Libya and was bound for Italy. This has been reported as the “deadliest shipwreck” in the area for a decade.

In December 2022, data released by Pakistan’s Bureau of Immigration revealed that more than 832,339 people had registered abroad for employment last year. That marks a more than 300% increase in the number of Pakistanis leaving the country to find greener pastures abroad.

In a country teetering dangerously close to default, the term looming over our economy was ‘brain drain’ — an economic phenomenon where highly educated individuals from developing countries go to already developed countries to find better compensation for their services as well as better living and working conditions. Of the 832,339 people that migrated from Pakistan for work, only around 92,000 were doctors, engineers, IT specialists, accountants, and other ‘highly skilled’ workers. The rest were mostly traveling to the Gulf to work as laborers, masons, drivers, and other blue-collar positions. That more than anything points towards a different problem: poverty.

However, with borders tightening across the world and restrictions soaring with legal immigration, many people resort to illegal border-crossings with the help of smugglers. And this route is obviously dangerous. Yet, excruciating poverty at homes leaves people with little choice.The situation has become so desperate that people are willing to gamble with their lives- and the Greek boat tragedy is a reflection of this.

Of the 104 Pakistanis present on the ship, around 28 came from the hometown of Mr. Wazir and Mr. Salman, Bandi, a picturesque valley alongside the border with India, in the Pakistani-controlled part of Kashmir. The village is now enveloped with a cloud of grief and anger.

“I have not seen such a sad day in the village in my 60 years of life,” said Muhammad Majeed, a shopkeeper. “It’s like doomsday — the village has lost so many young, hard-working sons.”

The area, with a population of around 10,000 people, has a long history of men migrating abroad. It’s common for a family to have at least one son based in the Gulf or Europe, sending a portion of their salaries back home each month.

At the stranglehold of violence between India and Pakistan, Bandi has been the centrestage for frequent cross-border shelling, which has destroyed homes and taken lives. Migration is perhaps the only means to escape violence and provide for families. Combined with Pakistan’s intensifying economic crisis, this trend has continued to rise. There are negligible prospects of decent jobs at home, and stories of people making it to Europe have inundated social media, amplifying the aspiration to migrate.

Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have also long been a hub for human trafficking. The rising cost of living, skyrocketing inflation and ubiquitous unemployment have aggravated the dire situation.

Around 80% of the people moving abroad are unskilled or semi skilled laborers struggling to make ends meet at home. According to the Ministry’s report for 2022, out of the 832,339 emigrants, only 1,902 were highly qualified and 2,777 were highly skilled. In contrast to this, overwhelmingly 24,445 were unskilled.

“Pakistan has a high rate of unemployment. People are simply unable to find work here, especially the unskilled and semi

skilled labor force. You’ll mostly find the working classes, employed as basic technicians, electricians, drivers and construction workers abroad. In most cases, they’re working in the Gulf countries (around 97%)- you’ll barely find such people working in Europe, Canada or the USA,” says Dr Muhammad Saleem, an economist.

“The jobs are not highly salaried there either. You’ll typically find laborers earning PKR 35,000-45,000 per month, which is very less. It’s barely enough to provide for food at home. Most people working in Saudi Arabia earn 600-700 riyals per month. This is hardly equivalent to the minimum wage in Pakistan after deducting the living costs.”

This unmasks the excruciating tragedy that people can’t even make this much for themselves at home. “Alongside this, the living conditions for laborers are gruesome in the Gulf countries. People are cramped in tiny spaces to save costs,” adds Dr. Saleem.

Taimur Khan Jhagra, the former Provincial Minister of KP for Health and Finance, disagrees with this however. “The working conditions are tough here also. Most people want to get public jobs. However, only 8-10% are able to acquire those. What do the remaining 90% do? If they have access to foreign jobs, that’s actually a huge plus. I would see it as a positive sign.”

KP has a particularly high percentage of people moving abroad for work. KP only constitutes 18% of Pakistan’s population. However, 32% of the laborers traveling for overseas employment come from KP. This is a jarring figure, nearly double its share of Pakistan’s total population.

People feel “there is no future and certainty in Pakistan anymore,” said Toqeer Gilani, a political leader in the Pakistani-administered part of Kashmir. “That has been gradually taking hold among the youth.”

This is where the question of remittances comes in. The common perception is that the foreign migration of labor forces is disastrous for the

as a positive sign

local economy because of bright minds and capable hands suddenly being fewer in circulation. The real situation is more nuanced than this simplistic worldview. As a matter of fact, the human development statistics from KP indicate that both education and healthcare have been improving over the last two decades.

According to Dr. Saleem, this is predominantly attributed to foreign remittances. “The income levels have slightly improved due to their influx. This has contributed to some local development. After winning the general elections in 2018, the PTI government promised to empower KP. In reality, it doesn’t have anything to do with the rising income levelswhich are mainly credited to foreign remittances. In general also, political governments have not had any substantive role to play in facilitating economic activity in the province.”

Jhagra also elucidates the bright side of this phenomenon.

“This is actually a matter of pride for Pakistan. It has significantly contributed to the local economy in the shape of remittances being returned to the local community. Pakistan owes a debt of gratitude to these workers” asserts Jhagra. “We shouldn’t worry about the proportion of people migrating overseas for work. Rather, the challenge is to upscale them so that they may find work beyond the blue collar jobs.”

“Annual remittances worth PKR 40-50 million come from the Pashtun diaspora alone. As a former minister in the KP government, I would think of strategies to further upscale this population. Even within blue collar jobs, they should ascend to higher levels of pay and eventually enter into the service economy. I have spent many years of my life in the Gulf. Yet I have never walked into Starbucks and seen a Pakistani employee. These workers should eventually make it there.”

“However, this is not to posit that blue collar jobs abroad are not important. They’re adding considerable value to our economy. Their counterparts here are sitting as clerks in

the government. The culture of paper-pushing is rampant in Pakistan.In fact, foreign remittances is one of the few areas wherein Pakistan has some advantage in terms of its population size.”

This nevertheless presents a paradox. On the one hand, foreign remittances substantively contribute to local development. On the other hand, they are productive only because the national economy is unable to sustain the local population. Instead of reaping the benefits of foreign remittances, should the government create more employment opportunities within the country?

“It’s not as simple as that,” exclaims Jhagra, “the moment it becomes disadvantageous to work abroad, people won’t go there. Despite the 18th amendment, the conditions required to foster economic prosperity are not in place. The central government including the bureaucracy is complicit in this. The KP government for example has no comparative advantage in facilitating economic growth. KP produces the bulk of Pakistan’s electricity and gas. Yet, it pays the same rate for electricity and gas as the other provinces.”