10 Has UBank cracked the code to making a microfinance bank profitable? 18

18 Pakistan is fishing for LNG suppliers again. But why does no one want to bite? 22

22 A terminal of Karachi Port has been sold to Emirati investors. How does it work and could there be roadblocks? 28

28 The battle for 10 lakh acres

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today' Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

For the past few months, Asif Ali Zardari has been camped in Lahore. And he hasn’t been sitting idly twiddling his thumbs at his desk deep inside the Bilawal House compound in Bahria Town. No. The former President has instead spent his time rubbing shoulders with leading businessmen and advocacy groups for Pakistan’s major industries.

In the past three weeks alone Mr Zardari has met with members of the business community on three official occasions. The last one was a discussion with a delegation of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) — one of the most important industrial bodies that exist in Pakistan.

With Minister for Industries and Production Syed Murtaza Mahmud and Senate standing committee on finance and revenue chairman Saleem Mandviwalla on either side of him during most of these meetings the message the former head of state is trying to project is very clear: the solutions to Pakistan’s economic problem lie with the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP).

The posturing is a clear tactic for upcoming elections. In the absence of the bruised and beaten PTI, the PPP is positioning itself to emerge as a contender in Punjab’s politics and a possible leader of a coalition government. The only problem is that the PPP has long had an image problem when it comes to the economy. Every party has a few ‘finance guys.’ The PML-N has Ishaq Dar chiefly, but they also have other options such as Ahsan Iqbal, Musadiq Malik, and briefly Miftah Ismail. The PTI had Asad Umar, Hammad Azhar, and Taimur Jhagra. But the PPP has no strong candidate for the position of finance minister. They have instead relied on technocrats like Abdul Hafeez Sheikh and Shaukat Tarin to guide sensible but uninspiring economic decisions.

Now, the biggest question on everyone’s minds is the economy. Will the IMF agreement pull through? Will Pakistan default? How will the inflation and cost of living crisis be managed? Everyone is thinking

along these lines and Asif Ali Zardari has judged the country’s temperature perfectly. That is why he is now pushing ahead to try and portray himself and the PPP as bearers of economic reform — a reputation the PPP has not had since the time of its founder.

And by all indications the strategy is working. Business leaders and industry associations have grown tired of the brash behaviour and unending empty promises from Ishaq Dar. That is why they have been more than happy to listen to Mr Zardari and imagine him in charge of the economy. It must be said that the PPP has played this entire matter very shrewdly.

It is clear to most that follow Pakistani politics that the biggest winner from the vote of no confidence that ousted former prime minister Imran Khan from power and all the events that ensued has been the PPP. Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has enjoyed international exposure and good press from his stint as foreign minister, a position once held by his illustrious grandfather. The party has also benefited from changes in accountability laws and have had their legal woes cleared up.

The PPP has at the same time avoided blame for the economic crisis in the country since all the guns have been pointed towards the prime minister and his fiance czar.

This has created a situation where at the same time that Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has been calling Ishaq Dar “my Uncle Dar” in parliament Mr Zardari has been running a shadow finance ministry and offering solutions to get Pakistan out of this economic quagmire. It was always apparent that whenever elections took place the parties that had banded together under the banner of the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) would go their separate ways. The purpose of the PDM ended the very day that Imran Khan was removed from office and Shehbaz Sharif’s continued occupancy of the prime minister house has simply been by the grace of Mr Zardari. With elections approaching, Mr Zardari has managed to bring his party into an enviable position.

The microfinance industry has been at the centre of some intense debate lately and have been labelled as “zombie banks.” They are different from commercial banks in terms of minimum liquidity adequacy requirements, collateral and the size of loans they can make. Their customer base is also very different from conventional banks and most, if not all, run a branchless operation. This and more, has made microfinance banking a very tough business in Pakistan. Barring a few, all microfinance banks are loss-making entities. However, it seems a new approach to microfinance banking may have worked, at least for the time being. An overly aggressive approach.

This is where U Microfinance Bank (UBank) comes in. Not only has UBank managed to achieve profitability, but it has also seen its balance sheet grow threefold in the year 2022. In the midst of the industry’s turmoil, UBank managed to navigate the challenges, and have thrived. But is it fair to call it a microfinance bank?

The microfinance industry has been hitting some rough patches lately, and let’s just say that the picture looks…. bad. Most of the microfinance banks are grappling with capital adequacy issue.

All commercial banks and microfinance banks, governed by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), are required to maintain a certain ratio between capital invested and risk exposure of different asset classes. This is called the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR). CAR for the Microfinance banks is 15% whereas for the commercial banks, it is 12.5%. The reason for having a higher CAR for microfinance banks is because microcredit has high risk. In other words, the customers of microfinance banks have a higher probability of defaulting on loans because they belong to a more disadvantaged socioeconomic group.

The State Bank of Pakistan has specified minimum capital levels (free of losses) for all banks and microfinance banks to keep their engines running depending on their scale of operations. A national-level microfinance bank is supposed to have a minimum capital of Rs 100 crore, provincial level microfinance bank is supposed to have a minimum capital of Rs 50 crore, regional-level microfinance bank is supposed to have at least Rs 40 crore as its capital, and finally, a district level microfinance bank is required to have at least Rs 30 crores as its capital.

Coming back to the microfinance banks, Apna microfinance bank reported negative capital of Rs 404.7 crores at the end of 2022. Despite capital injection of Rs 35 crore by sponsors, it still made a substantial loss of Rs 450 crore in 2022. To bring new capital, in early 2023, they announced consideration of a merger with FINCA Microfinance Bank (FINCA) which is also in the same boat, struggling with capital adequacy issues.

FINCA reported a net loss of Rs 150 crore in 2021, following which the auditors flagged out uncertainty over going concerns. FINCA does not have enough assets to pay off its liabilities. The latest period for which FINCA’s financial statements are available is for the first quarter of 2022 in which it reported a sparse profit of Rs 26 crores. The bank hasn’t released the subsequent period’s financial statements, which indicates the bank’s continued bleak capital adequacy issue. However, recently both microfinance banks have decided to not merge.

It doesn’t stop there. NRSP Microfinance Bank Ltd, the subsidiary of the National Rural Support Programme, reported a jaw-dropping loss of Rs. 400 crore in 2022. Advans Microfinance Bank? They’re not doing any better either, reporting losses of more than Rs 10 crore in the same year. Even the big players like Telenor Microfinance Bank and Khushhali Microfinance Bank took a hit, reporting a net loss of Rs 670 crore and around Rs 300 crore in 2022 respectively.

Now if we look at the microfinance banks that reported profits, these are handful namely U-Microfinance Bank, Sindh Microfinance Bank, LOLC Microfinance Bank (formerly known as Pak Oman Microfinance Bank), Mobilink Microfinance Bank and, lastly, HBL Microfinance Bank. UBank took the lead with the highest profit clocking in at a staggering Rs 220 crore followed by HBL Microfinance bank and Mobilink Microfinance Bank which reported a profit of Rs 120 crore and Rs 96 crores respectively. LOLC Microfinance Bank reported profit of Rs 11.5 crores while Sindh Microfinance Bank reported a meagre profit of Rs 4.1 crores.

When we add up all the losses, the industry as a whole reported a gut-wrenching loss of more than Rs 1800 crores in 2022. The profits reported during the same period only added up to Rs 450 crore. That’s a net loss of Rs 1350 crores! It is safe to say that the microfinance industry is in a pickle.

Let’s take a closer look at the power players in the microfinance industry. Out of the 11-12 organisations in the mix, there are five that dominate the

scene.

Of these five, three are subsidiaries of telecom giants. We’re talking about Telenor Microfinance Bank, Mobilink Microfinance Bank, and U-Microfinance Bank. Telenor Microfinance Bank is jointly owned by Telenor Group and ANT Group. Mobilink Microfinance Bank is a subsidiary of VEON, a global digital operator that provides mobile connectivity and services and sister company of Jazz. Finally, U-Microfinance Bank is a wholly owned subsidiary of Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL) – Etisalat Company.

Other two include Khushhali Microfinance Bank and HBL Microfinance Bank which are subsidiaries of commercial banks, with United Bank Limited (UBL) holding a 30% stake in Khushhali and Habib Bank Limited (HBL) holding over 70% in HBL Microfinance Bank.

If we look at the strategies and approaches of two telecom-based key players in the microfinance industry namely Mobilink MFB, and Telenor MFB, both of these organisations have set their sights on branchless banking. By the end of 2022, Telenor MFB and Mobilink MFB had 61 and 109 branches respectively. Mobilink MFB has its digital platform called Jazzcash, while Telenor MFB has Easypaisa. These platforms have allowed them to bring banking services directly to the fingertips of their customers, making transactions and financial management more convenient and accessible than ever before.

According to the annual report of 2022, Easypaisa had 14 million monthly active users. The mobile wallet recorded around 1.4 billion transactions whereas Jazzcash reported 16.4 million monthly active users and recorded 2.1 billion transactions in the same period.

Telenor MFB decided to steer towards branchless banking when it unearthed massive employee fraud back in 2019. This incident prompted them to reassess their approach and move away from bullet lending in the agriculture sector. Instead, they decided to pivot towards a digital-first strategy, integrating their microfinance banking and branchless banking businesses into one cohesive unit. Mudassir Aqil, speaking to Profit , explained, “We made the entire bank on a digital-first strategy.”

In contrast, UBank opted for a distinct approach, adopting a conventional, brickand-mortar strategy. Kabir Naqvi, CEO of U Bank, told Profit , “We did not try to turn it into a telecom company. We said that this is a bank, and its mission is microfinance. Just like a bank, its balance sheet will grow. It will have liquidity, strong cash reserves, a treasury function, Islamic banking, digital banking, and even conventional microfinance. It will also have an urban unit responsible for deposit mobilisation. If all these elements are in place, (only then) will this institution thrive and last for the next hundred years”.

“Credit also goes to our shareholders, who understood our perspective and had faith in us. Simultaneously, we will continue pursuing our agenda in branchless banking,” he added.

Naqvi further elaborated that they have been cautious about engaging in loss-making activities. They have prioritized profitability and sustainability. “If making an interbank fund transfer (IBFT) transaction is generating a monthly loss of Rs 400 million, I did not let that happen at UBank,” he explained.

In the microfinance industry, the practice of bullet lending to the agriculture sector has proven to be a double-edged sword. Telenor MFB, recognizing the pitfalls of this approach, made the strategic decision to exit this type of lending after experiencing significant writeoffs. The move was prompted by the realisation that such loans were not yielding the desired

results for the bank. Similarly, most of the microfinance banks that report losses and have been writing off massive non-performing loans reference these loans.

Interestingly, UBank has also engaged in bullet lending, but with remarkably different outcomes. UBank has managed to navigate the treacherous terrain of bad loans and write-offs. How? Unlike other microfinance banks, UBank has chosen to secure around 60% of its loan portfolio with gold.

Note: The cap on collateralizing loan portfolio against gold is 35% as per regulator. We were unable to get a response from U bank in time explaining how it has managed to take this up to 60%, as indicated by them in our initial reporting.

This means that UBank issues most of its loans against gold collateral which serves as security against risk of defaulting on loans.

While this decision provided a safeguard against potential defaults and minimised the risk associated with unsecured lending, it restricted the size of UBank’s loan book compared to other microfinance banks like Khushhali MFB and HBL MFB, who chose not to secure their loans.

“Theirs may be around Rs 8000 crore while mine is Rs 6000 crore. (Though) in relative terms, UBank’s loan book is bigger as they (Khushhali bank and HBL microfinance bank) have been around for 23 years, whereas UBank has been in operation for 7 years”, said Naqvi.

Naqvi also shared the criticism that he and UBank received when they started gold-

backed loans. Critics initially raised concerns that UBank’s gold-backed loans deviated from the spirit of microfinance. However, Naqvi strongly defends this approach, highlighting the win-win situation it offers. “If someone has a dead asset lying in their home which can be monetised and can also help leverage our capital adequacy. And (in return) they are receiving locker services and getting a better interest rate, isn’t it a winwin situation? Why should we not do it?”, retorted Naqvi

Naqvi further emphasizes that goldbacked loans have an added advantage. “Gold carries sentimental value, which reduces the likelihood of defaults whether the price of gold goes up or down,” he added. However, better sense has prevailed as other microfinance banks have also recognized the benefits of gold-backed loans and have started issuing gold-backed loans.

It is an odd proposition, the handing over of your gold to your banker to raise finance, but it is the only way MFBs can collateralise their lending. SBP has issued detailed guidelines on how MFBs are supposed to handle and store the physical gold. This ranges from the valuation and authentication process to the storage, return or auctioning of the gold.

One industry expert, who wished to remain anonymous, put the concerns surrounding gold-based lending in two categories. The theoretical and the practical. Theoretically,

“We did not try to turn it into a telecom company. We said that this is a bank, and its mission is microfinance. Just like a bank, its balance sheet will grow. It will have liquidity, strong cash reserves, a treasury function, Islamic banking, digital banking, and even conventional microfinance. It will also have an urban unit responsible for deposit mobilisation. If all these elements are in place, (only then) will this institution thrive and last for the next hundred years”

Kabir Naqvi, CEO of UBank

microfinance banks are supposed to provide de-collateralized credit and therefore taking gold as collateral to lend goes against the spirit of microfinance banking.

From a more practical perspective, there is the argument that it disempowers women.

“The type of gold in question here is biscuits or raw gold, it is mostly processed, jewellery and all. And this is mostly owned by women who inherit it or receive it at their wedding for example. The lending that is being done is mostly, if not only, to men and in many circumstances the women might not want their only asset ‘the gold’ to be put at risk for a project they most likely will have nothing to do with or benefit from”, he added.

Apart from these valid concerns, there is the problem of security i.e. physically securing and handling the gold. Not only does it add to the administrative expenses but there is the added risk of pilferage and theft. Some instances of missing gold from the possession of banks have been reported.

“This is why UBank charges close to 43% for gold-backed lending. Because their cost is so high, close to 22%”, commented a senior MFB executive on condition of anonymity.

Naqvi however disagrees and believes this is the only way to do business and is investing heavily in this side of his business: lending against gold.

“We have spent a lot of time and money on security and administrative measures to

make sure that the gold entrusted to us is safe”, Naqvi explains.

Microfinance banks can now lend up to Rs 30 lakhs which is a significant increase from the previous limit of Rs 5 lakh. Moreover, 35% of the loan book can also be consumer finance like low-cost housing loans which are loans of up to 20 years. Microfinance banks have also expanded into the MSE (micro small entrepreneur) segment that offer commercial vehicle loans which include tractor financing and are extended for up to 5 years. Essentially, UBank is mirroring the services provided by commercial banks to their SME customers as Naqvi proudly declares, “I think calling us a Microfinance bank is a misnomer. These are retail challenger banks if you ask me.”

“The microfinance industry is going through a metamorphosis and it is one of the reasons why UBank is experiencing growth,” claimed Naqvi.

UBank undertook a strategic overview of its balance sheet and business model two years ago. “We used business model canvas to break down our business into different verticals. The first canvas is of microfinance core. We named it ‘Rural Retail’. The lending in this vertical accounts for most of the

Rs 5900 crores of advances you see in our financial statements.The next vertical we recently created, an in-progress initiative, is ‘Urban Retail’. Under this vertical, we are opening new branches in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad urban cities and hiring commercial bankers to run these banks. This vertical is to mobilise deposits and increase the deposit base”, Naqvi told Profit. Other business units include Islamic Banking, Digital Banking, Corporate Banking, and Corporate Finance & Investment Banking.

As mentioned earlier, instead of going digital, UBank has prioritised brick-and-mortar format and have been expanding their branch network. Number of branches in 2021 was 207, which increased to 303 by the end of 2022. UBank plans on adding another 100 branches to reach 400 branches by the end of 2023. That’s an increase of approximately 100 branches per year. Assuming that there are 260 working days, UBank has opened a new branch every 2.6 days!

So why is UBank opening so many branches? Usually it is to enhance proximity to its customers. The closer the microfinance banks are to their borrowers, the easier it will be for the borrowers to approach it for borrowing more money and timely servicing

their loans.

Here is the catch: UBank has been opening new branches in urban cities like Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. So why is UBank adamant on adding these many branches in cities who are not the primary customers? “These branches will mobilise our deposits”, responded Naqvi.

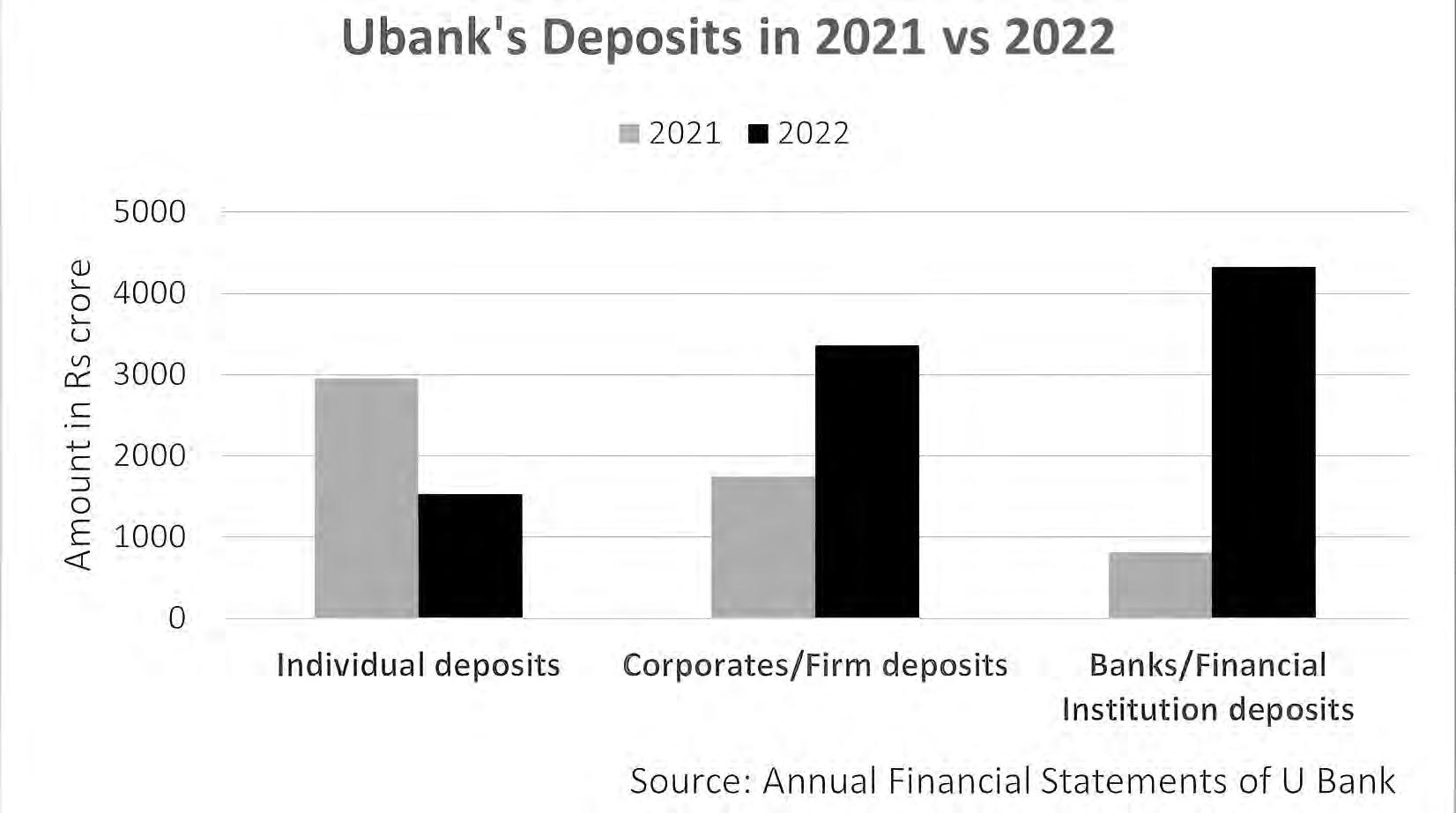

Did the deposits increase? Overall, deposits increased by 1.7 times in 2022 as compared to 2021, clocking in at Rs 9,200 crores. However, the increase is not coming from individual depositors but rather from banks and financial institutions.

Collectively, Banks and Financial Institutions have placed Rs 4,300 crores with UBank in 135 accounts. It is all the more impressive considering that the balances kept by banks and financial institutions with UBank were just Rs 800 crores in 2021. That is a fivefold increase in deposits in one year. In other words, banks and financial institutions have placed an average of Rs 35 crore per account. On the other hand, the amount deposited by individual deposits have actually gone down from around Rs 2950 crore in 2021 to around Rs 1530 crore.

There is one more catch to these big-ticket deposits by banks and financial institutions: these are high-cost deposits. As one senior investment banker told Profit, big-ticket deposits earn higher interest rates. If these deposits are in microfinance banks, then the interest rate can go up to 21% i.e. interest rate set by the State Bank of Pakistan. Microfinance banks can offer a higher rate

because their lending portfolio is also priced very high as interest rates on loans range between 31% to 40%. Besides, unlike retail deposits which can be sticky, these institutional deposits are like hot money which can suddenly flow out when circumstances change as we have seen recently in Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

This is not the case with other telecom based microfinance banks who have been able to attract low-cost deposits (low to no interest deposits). Mobilink MFB’s deposit pool of Rs 65 billion is predominantly fueled by individual depositors, who contribute a whopping Rs 50 billion, making up a staggering 78% of the total deposits. Similarly, Telenor MFB had about Rs 47 billion of deposits in fiscal year of 2022 of which Rs 42 billion were fueled by individual depositors. That’s almost 90% of the deposits.

So on one hand Naqvi criticises the approach of other microfinance banks that they are indulged in loss-making activities and on the other hand it itself is plagued with high-cost deposits.

It is a no brainer that UBank would want to attract low-cost deposits and it is also fair to say that increase in branches has not yielded much result as not only has UBank failed to attract individual deposits but the deposits have actually decreased. Naqvi attributes this phenomenon to the relative novelty of the bank’s branches, which were established in the last two quarters of 2022. However, he is confident that the results of these branches will become apparent soon. “Our

branches are fairly new right now. These were opened in the last two quarters of 2022. You will see the result in the next year or two.”

However, deposit mobilisation in major cities such as Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad is going to be no easy feat. These cities already have a multitude of well-established commercial banks with stronger presence and reputation. Considering the tarnished image of microfinance banks in general, will UBank entice customers by offering higher profit/ interest rates? Moreover, will individuals be inclined to open deposit accounts with UBank when alternative options exist?

Remember UBank’s deposits increased to clock at Rs 9,200 crores (a whopping increase of Rs 3700 crore)? One would assume that advances (loans) would have increased by almost the same amount because that’s what banks are supposed to do. However, UBank’s lending grew by only Rs 2500 crore. So where did the incremental deposits go?

If we look at the other significant movements on the asset side of the balance sheet to see what the increased deposits are financing, we see a major increase in investments. The deposits were more than the advances by Rs 1200 crore. So the difference should have been used to make investments. But the increase in investments is Rs. 9100 crore between 2022 and 2021. And this investment is not being

financed by equity as net assets have actually decreased. Rather, the increase in investment is being financed by increased borrowings. Both investments and borrowings increased three-fold over the last year. The investments increased by Rs 9700 crores to Rs 13,700 crores which was financed by an increase in borrowings of Rs 7900 crores which amounted to Rs 11,600 crores.

So what has happened here? UBank used its deposits to purchase money market mutual funds (MMFs) or government securities (T-bills/PIBs). Then, it pledged those very PIBs to the same banks or even a third-party bank, allowing UBank to borrow additional funds through repos with a small margin. With the borrowed money in hand, UBank repeated the process of purchasing more Tbills/PIBs. This cycle continued, spinning a web of financial manoeuvring so much so that while the size of assets increased from Rs 10,458 crore in 2021 to Rs 22,130 crore in 2022, net assets have declined from Rs 749 crore in 2021 to around Rs 709 crore in 2022, a decrease of Rs 40 crore.

Naqvi explains this increase with its newly added treasury and corporate finance vertical. Through this vertical, UBank aims to be the first microfinance bank with an active treasury just like commercial banks. “It will provide UBank with arbitrage opportunities,” Naqvi said. The bank has formed beneficial alliances with multiple banks. The borrowing activities of UBank encompass syndicated loans, bilateral loans, and bonds, he calls it a “beautiful bouquet”. Initial borrowing was secured against the loan book, while subsequent borrowing was supported by pledged investments, fostering stronger relationships with banks.

“On the investment side, government securities consist mostly of floating PIBs which account for Rs 5600 crore of the total investments. These securities are repriced every two weeks. We have taken short exposure of 2 weeks to 1 month because we can endure this much exposure only”, Naqvi further added.

Ironically, while UBank criticises other microfinance banks for straying from the microfinance realm and becoming telecom companies, it appears to be following a similar path. It is engaging in practices that commercial banks have been criticised for, such as investing in government securities to earn riskfree interest income instead of actively lending to the private sector. In essence, UBank has enhanced its profitability not by increasing lending, which is expected of a microfinance bank, but by capitalizing on income generated from government securities. “Income from lending is taxed at 32% while income from investment securities is taxed at 15% which has improved our net income”, Naqvi high-

lights this advantageous tax treatment as a contributing factor to their improved financial performance and higher profit.

UBank is essentially managing risk. We will have to look at three main heads to understand what exactly they are doing: deposits, borrowing and investments.

Of their total deposits amounting to Rs 92.2 billion, only Rs 15.2 billion is attributed to individual depositors, the remaining Rs 77 billion is from institutional depositors i.e. banks and corporates. These deposits are not sticky meaning any bank; say ABL or a corporate like Engro can take this money elsewhere at any time.

According to its 2022 financials, UBank’s deposits increased by Rs 37 billion year-on-year, which is more than the increase in advances for the same period, Rs 25 billion. UBank therefore more than covered the increase in advances, which would conventionally mean it had no need to borrow. But it cannot rely on non-sticky institutional depositors money to remain parked with the bank, it therefore had to borrow to cover the risk of any liquidity problems.

UBank’s total borrowing from banks amounted to Rs 116.1 billion in 2022, which more than covers its advances book. This is fully-secured borrowing – why else would commercial banks lend so easily to a microfinance bank? What this means is that UBank has to buy government-backed securities with the borrowing it is doing from banks and pledge those securities to the bank. And this brings us to the investment side of the equation.

UBank’s investments stood at Rs 137 billion for the year ended 2022, reflective of the terms of borrowing from commercial banks. But wait. Isn’t this a bad deal? Commercial banks won’t lend at a loss, so they will charge interest, at KIBOR plus-X. T-bills and PIBs don’t pay more than that as they are closer to the discount rate. So what is UBank doing? Booking a loss? Not quite

“We borrow at 6M KIBOR+1 and most of my investments are of a lesser tenor than that, one to three months. So I lock my interest rate for 6 months and in an economy where the interest rate is increasing, I actually turn a profit because the earning on my shorter term investments (T-bills and PIBs) will be higher” Naqvi explained.

To simplify, if one borrows at 6-month KIBOR + 1, that rate is locked for all interest payments to be made for the next six months. If the discount rate increases within these six months, it will not impact those interest

payments. On the investment side however, the same party has invested in a shorter tenor instrument, a 1-month T-bill perhaps. It will therefore be able to take advantage of the interest rate hike as it will immediately be reflected in the market price of the T-bill.

It is widely expected that interest rates will start to fall in the coming months as inflation recedes. In an economic environment where interest rates are falling, UBank will do what any other commercial bank treasury will do, start borrowing shorter term and invest in longer tenors.

What UBank under Naqvi is doing is building and managing a money market book. “All banks have treasuries. There is no restriction on microfinance banks to run a treasury. So that is what we have done”, he added.

There is nothing wrong with what is being done at UBank. It’s just an aggressive approach to microfinance banking that no one else is taking. To mitigate his advances book risk, Naqvi has borrowed heavily from banks and by actively managing the necessary investments his bank has to make to borrow, he is also earning on the interest.

And even if he does make some loss on his treasury operations due to unforeseen economic circumstances for example, his board and shareholders should still be happy as he has successfully secured the bank against a liquidity crisis.

“I am building relationships with banks. And overtime, they will start lending to me against my advances rather than government-backed securities. One or two banks are already comfortable enough with us to start doing this”, Naqvi added.

While on the surface UBank has managed to steer itself away from losses, it has also been steering away from the realm of microfinance banks. In other words, the primary business of a microfinance bank was extending advances (microlending) to people who otherwise did not have access to financial services because commercial banks did not want to cater to this audience. But instead of increasing proximity with its target audience, UBank has been steering in the direction of a commercial bank and doing exactly what commercial banks are criticised for.

But there is no restriction to what it is doing. It is all within the confines of the allowances its microfinancing banking licence makes. It is just unconventional, but if it is working, which it apparently is as per its P/L, then it is perhaps something its competitors should be looking at. However, there are some significant risks being that only time will mitigate and whether or not UBank makes it to that stage in its journey as an ‘industry defining’ bank, relatively unscathed, remains to be seen. n

Prices of LNG have gone down on the global market, but Pakistan is still facing problems. What does this indicate for the winters to come?

By Urooj ImranThe news stories hit like clockwork every year. As the winters approach, different industries start complaining that there is not enough gas to run their operations resulting in reduced output. Countrywide blackouts ensue. Gas load shedding for domestic consumers makes the headline and there is a sense of doom and gloom.

Whether this will happen again this year became a question last week after it emerged that Pakistan failed to receive any bids in its latest attempt to procure liquified natural gas (LNG) from the spot market. Pakistan has not tried to procure LNG for a while. So what gives now, and why is the country finding it hard to buy the product?

The Pakistan LNG Limited (PLL), a government subsidiary that manages the entire LNG supply chain from procurement to distribution to the end user, issued a tender on June 13, seeking six cargoes for delivery in October and December. The quantity sought

was 140,000 cubic meters of LNG per cargo. The tender’s outcome was keenly watched as it was issued almost a year after a previously unsuccessful attempt in July 2022 when the PLL received zero bids. However, shortly after the new tender closed on June 20, the PLL shared that once again, no bids were received.

And here arose the concerns. Pakistan relies heavily on LNG for fulfilling its energy needs; nearly a third of its power is generated using Regasified LNG (RLNG). However, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24 and the resulting sanctions, European countries started buying out LNG cargoes on fears of loss of Russian supplies.

Since Russia was sanctioned, the global supply of gas was affected and European countries rushed to plug shortages by procuring it from suppliers elsewhere. This not only created a global energy crisis, threatening the energy security of countries such as Pakistan but also crowded them out of the spot market.

Due to the increased demand, prices in the Asian spot market went up to a record high of $70 per million British thermal units (mmBtu) in August 2022. Coupled with the rapidly

devaluing rupee and low foreign exchange reserves, Pakistan either failed to attract any bids or the ones received were too expensive for the cash-strapped nation. Between March 2022 and June 2023, Pakistan issued 11 tenders for procuring LNG from the spot market, the last of which is set to close on July 14.

Pakistan received seven bids for a tender issued in March 2022, the lowest of which was $33.53 per mmBtu. It received 10 bids for the next tender in April, with the lowest priced at $24.15 per mmBtu. However, the number of bids started declining after that, with the country receiving only one bid for a tender issued in May. It failed to attract any bids in another tender, this time in July. The country also tried to procure LNG for a six-year period via a tender issued in October last year but again failed to attract any bids.

While Pakistan procures LNG from the spot market to cover its energy needs, the country has two long-term deals with Qatar, totaling 6.75 million metric tons per year, and an additional contract with ENI for 0.75 million metric tons per year.

Amid the volatile global situation and its worsening economic crisis, ENI canceled

the delivery of scheduled cargoes to Pakistan multiple times. The company has a 15-year deal with Pakistan to deliver one LNG cargo a month till 2032. However, it canceled deliveries and said disruptions were caused due the supplier not fulfilling its obligations. While ENI claimed it did not benefit from the situation, Bloomberg cited a report from two non-profits — Sourcematerial and Recommon — which stated that the company earned $ 550 million by canceling scheduled cargoes between

late 2021 and early 2023, and reselling them. These shortages, combined with the surge in oil prices due to the Russian invasion, exacerbated Pakistan’s energy crisis. Power production was affected, tariffs and inflation increased and there was prolonged loadshedding. However, as the global supply started stabilizing later, the prices declined with the Asian spot market rate falling below $10 mmBtu. This was one of the reasons the response to Pakistan’s tender was being watched closely as

it might have indicated the global energy crisis has eased. The failure to attract bids, however, appears to be unrelated to the global energy crisis, and more to Pakistan’s economy and the government’s measures.

An energy professional who spoke to Profit said the major factor behind zero bids was the government’s deal with Azerbaijan.

The Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) recently gave the go-ahead to the PLL for executing a framework agreement with the State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SOCAR), under which Pakistan will receive one LNG cargo a month.

Under the terms of the agreement, which is initially valid for a year, SOCAR will offer Pakistan one LNG cargo every month 45 days before the delivery window to be paid for in USD. The PLL will compare the price with spot market rates and consult the power sector to evaluate affordability. If it accepts the offer, PLL will issue letters of credit (LCs) from local banks and pay the amount within 30 days of receiving the invoice.

The energy professional said that Pakistan’s available capacity was one LNG cargo a month. Following Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s visit to Baku and extensive publicity about the LNG deal, traders were aware that the tender was being issued for “price discovery” since the deal gave SOCAR the opportunity to match the lowest bid offered in the spot market.

Since the price was not pre-agreed with SOCAR, the government now needed to find out the spot market price. However it got the timing wrong, he said.

Since SOCAR already had the option to match the lowest price, global LNG suppliers would have effectively sent a bid into the tender only for the Azeri company’s benefit, the energy professional added. “If there were any bids in the opening, they would not have been

The energy supply this winter would be better than last year’s as more coal-fired power plants had come online and Pakistan would be receiving one LNG cargo from Azerbaijan every month compared to 2022 when it had no options due to the elevated prices and lack of bids

Ammar H Khan, Independent macroeconomist

honored. Instead, the government would go to SOCAR and ask it to match the lowest price.”

When asked whether the lack of bids was related to the ongoing economic crisis and difficulties in opening LCs, he said that it wasn’t.

However, Pakistan’s critically low foreign exchange reserves — $ 3.54 billion as of June 16 — and the resulting difficulties in opening LCs may also be a factor behind the tender’s failure. Pak-Kuwait Investment Company’s Head of Research Samiullah Tariq shared that LNG suppliers had said LCs could not be confirmed.

Lakson Investments Chief Investment Officer (CIO) Mustafa Pasha said the main issue for Pakistan was the spike in its credit risk because of uncertainty regarding the International Monetary Fund (IMF) program’s revival. “We have about $ 10+ billion of debt repayments to make in the next six months (July-December) out of which $ 6 billion have to be paid. And given that reserves are under $4 billion, it obviously creates doubts in the minds of banks and other financial institutions who will be part of the transactions in terms of LCs.”

He also noted that LNG prices had declined from record highs reached last year and the demand from Europe — which stockpiled LNG supplies after the Russia-Ukraine war began by outbidding everyone else in the market — had declined. Besides this, long-term

deals were being signed, including a 20-year deal between US and German companies and another 27-year deal between China and Qatar, he pointed out.

“So it’s not a question of whether there are no supplies in the market which is why Pakistan is being rejected. It’s a Pakistan-specific issue. People are not willing to take the credit risk on Pakistan for that October-December period because there is very little certainty about Pakistan’s going concern status in that time period.”

An accounting term, going concern in the context of a country such as Pakistan would mean it has enough money for financing and repaying debts.

Profit reached out to Minister of State for Petroleum Musadik Malik several times, both for a comment on the tender as well as reports that senior PML-N leader Shahid Khaqan Abbasi quit the ECC over the Azerbaijan deal, but he did not respond. Profit also reached out to Abbasi but the former prime minister remained unreachable.

Reasons aside, will the failure to attract bids lead to an energy crisis similar to the one last winter where there were prolonged power outages and gas was only available for certain hours during the day?

Independent macroeconomist Ammar H. Khan said the energy supply this winter would be better than last year’s as more coal-fired power plants had come online and Pakistan would be receiving one LNG cargo from Azerbaijan every month compared to 2022 when it had no options due to the elevated prices and lack of bids.

Separately, Tariq also commented, “It will not be as bad as last time because we have alternate power generation sources; Thar coal and nuclear power plants have come online, because of which power supply is better. We already receive eight cargoes of LNG, these can be diverted towards industry when there is a shortfall. There will be a shortfall. It will, however, not be severe.”

Earlier this year, Minister for Power Khurram Dastgir had told Reuters in an interview that LNG was “no longer part of Pakistan’s long-term plan”. Instead, the country would quadruple the electricity it generated from coal to reduce costs, he had said.

According to the Pakistan Economic Survey FY23, three coal-fired power plants with a total capacity of 1,980 megawatts and a nuclear power plant of 1,100 megawatts became operational during the current fiscal year.

Pasha said that there would be gas and power shortages this winter just like in previous years if Pakistan failed to receive bids — another tender for delivery of three LNG cargoes in January will close on July 14.

“But this is something we’ve been seeing happening for a while. So, if Pakistan doesn’t get these LNG tenders ... there will be a deficit in [energy] supply,” he added.

On the other hand, State Minister for Petroleum Musadik Malik has claimed that the LNG deal with Azerbaijan will “end the gas crisis soon” and domestic consumers, in particular, will not face any problems in the winter.

Tariq said the long-term solution to ending the gas crisis is to focus on and improve policies to increase indigenous gas production. Even with reduced prices, importing gas puts pressure on the country’s fragile balance of payments, he noted. n

We have about $ 10+ billion of debt repayments to make in the next six months (July-December) out of which $ 6 billion have to be paid. And given that reserves are under $4 billion, it obviously creates doubts in the minds of banks and other financial institutions who will be part of the transactions in terms of LCs

Mustafa Pasha, Chief Investment Officer Lakson Investments

LNG is no longer part of Pakistan’s long-term plans. Instead, the country will quadruple the electricity it generates from coal to reduce costs

Khurram Dastagir, Energy minister

Abu Dhabi Ports is set to takeover operations from the PICT. But will the dicey law used to make the transaction go through prove to be a problem?

It happened fast. Surprisingly fast. Suspiciously fast almost. This is what went down.

A delegation from the UAE visited Karachi and met with Faisal Sabzwari, Federal Minister for Maritime Affairs on the 18th of May. The group contained delegates from AD Ports and Kaheel Terminals — both companies engaged in the development and management of ports around the world. It became clear during the meeting that the Emirati investors wanted in on Karachi port and the cash starved government was more than happy to oblige for any chance to get their hands on foreign exchange.

Things moved quickly and a memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed between the investors and the government. Just over a month later, on the 19th of June, the Cabinet Committee on Inter-Governmental Commercial Transactions created a negotiation committee to draft an agreement for the handover.

The committee worked fast. Three days later, a company by the name of Karachi Gateway Terminal Limited (KGTL) was created to manage, operate and develop berths 6-9 at Karachi Port’s East Wharf. A joint venture between AD Ports and Kaheel Terminals, KGTL claimed it would spend the next 10 years developing the port terminals and increasing its capacity. Overall, the immediate investment coming into Pakistan would be worth over $220 million —- a precious sum for a forex starved country.

There are a lot of questions regarding the agreement and the birth of KGTL. What parts of Karachi Port will be handed over to the new company? Who are these investors willing to take a bet on Pakistan at a difficult time in its history? Will they be able to make any money off this? Could the proposed expansion to the container terminals have any benefits for Pakistan?

But perhaps the most pertinent question is how this entire transaction happened so quickly. The answer lies in the Inter-Governmental Commercial Transaction Act (2022), a piece of legislation conceived to expedite and streamline the transfer of public assets and services to foreign entities. Essentially, the law grants overreaching powers to the finance minister and cabinet which can unilaterally enter business agreements with foreign investors that are not subject to regular checks, balances, and regulations. In theory it can be a good idea to increase the ease of doing business. But legal experts fear it could be setting a dangerous precedent and might require the involvement of the courts of the land.

But before we get into any of that. Let’s start right at the beginning. Who exactly is investing in Pakistan right now, and what in the world are they getting in exchange for their hundreds of millions of dollars?

The company in question is Abu Dhabi Ports Group. Now who is that you might ask? The Abu Dhabi Ports Group (AD Ports Group) is the exclusive developer and regulator of ports and related infrastructure in Abu Dhabi. It was established in 2006 and is owned by Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company (ADQ). ADQ itself is an investment vehicle for the government of the UAE. AD Ports is thus owned indirectly by the government of the UAE through its ownership by ADQ. AD Ports has five integrated business clusters: Digital, Economic Cities & Free Zones, Logistics, Maritime, and Ports.

It is this AD Ports which came to Pakistan along with another Emirati company called Kaheel Terminals. Both of these companies entered into a JV which is now the KGTL which will manage Karachi’s port terminals. The terminal berths 6-9 are set to be handed over to KGTL from Pakistan International Container Terminal (PICT) — the company which was managing the port’s container terminals up until now.

AD Ports Group is set to acquire control of the private container terminal on Berths 6 to 9 from PICT. The deal is valued at an estimated $220 million, and is being conducted entirely in dollars and does not involve local currency. The four berths will be leased for 50 years and managed by the Karachi Gateway Terminal Limited (KGTL).

But why would the Abu Dhabi Group make such a large investment in Pakistan and that too in the ports business? The important thing to understand is that ports are massive and there are many players that dot the map of any port. Security, terminal management, warehousing are all done by different companies. In this case, the group is looking only to take over

control of port terminals.

Container terminals, along with container ports as a whole, are a crucial part of the supply chain network. They play a vital role in a country’s growth and development, and contribute to economic, political and trade relations around the world. A container terminal’s main function is to allow for the transfer of shipping containers and cargo between ships and other modes of transport, such as trucks and trains. Terminals also act as a checkpoint where ships are inspected, loaded and unloaded.

Generally, terminals are a profitable business. In a statement given after the deal was struck, the AD Ports Group said that the Karachi Port terminal “has been generating revenue of around $55 million and EBITDA or around $30 million annually.” Karachi overall has three container terminals. The one in question is located at Berths 6 to 9. The second one is Karachi International Container Terminal operated by Hutchison Port Holding. This one is at Karachi Port too. The third one is Qasim International Container Terminal at Port Qasim, and is currently managed by DP World. What’s the takeaway? Private entities managing terminals is fairly common practice contrary to widespread speculation and media conjecture.

{Editor’s note: EBITDA is net income (earnings) with interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation added back. EBITDA can be used to track and compare the underlying profitability of companies regardless of their depreciation assumptions or financing choices.}

The problem, however, is that in recent years the port and terminal business has needed more money. Ships are getting bigger and that means larger ports and terminals need to be built to accommodate this. The AD Ports Group has come in with the hope of expanding the Karachi Port terminals and reaping the benefits. In the earlier mentioned notification, the AD Ports Group said that “The JV will undertake significant investments in infrastructure and superstructure over the next 10 years, with the bulk of it planned for 2026. The development works will include deepening of berths, extension of quay walls, and an

increase in container storage area.”

“As a result, the terminal will be able to handle Post Panamax class vessels of up to 8,500 TEUs (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units) and container capacity will increase from 750,000 to 1 million TEUs per annum. This expansion and enhancement will further cement the Terminal and Karachi’s position as a key player in the maritime industry,” it reads.

This is where it gets tricky. The Inter-Governmental Commercial Transaction Act (2022) was approved by the National Assembly in August 2022. This legislation empowers the federal government to establish a Cabinet Committee on Inter-Governmental Commercial Transactions. The committee’s primary mandate is to negotiate and enter into inter-governmental agreements, facilitating state-owned enterprises from both countries to embark on commercial ventures in Pakistan or abroad. This is the cabinet committee that has now entered an agreement with the Emiratis.

The committee also possesses the authority to expedite procurement of services from transaction advisors or consultants and make crucial decisions for the swift execution of commercial transactions. What does all this mean?

“It’s essentially a three-page act that permits exemption from regulatory and other requirements under numerous other statutes that would typically apply to a commercial transaction, such as the Privatisation Ordinance and the Securities Act, among others,” Mayhar Mustafa Kazi, a partner at RIAA Barker Gillette, puts succinctly.

“The Act furnishes an expedited avenue for the sanction and realisation of commercial transactions between the Government of Pakistan or any state-owned entity and an entity designated by a foreign government,” Kazi elucidates. “The Act envisages a government-to-government accord or a frame -

It’s essentially a three-page act that permits exemption from regulatory and other requirements under numerous other statutes that would typically apply to a commercial transaction, such as the Privatisation Ordinance and the Securities Act, among others

work agreement under which a commercial contract can be executed and actualised. A Cabinet Committee can advocate exemptions or relaxations from regulatory adherence under other statutes. These encompass statutes mandating public bidding, compulsory tender offers, and public disclosures, among others,” Kazi adds.

“What it envisages is that initially, you can have a government-to-government accord or a framework agreement,” Kazi expounds. “This is going to be an agreement between two governments in which they establish the broad parameters of the understanding regarding a commercial transaction.”

“That’s going to be followed by a commercial transaction which will take place in accordance with whatever is agreed in the government-to-government accord,” adds Kazi. “The counterparty for that transaction has to be a foreign entity that is either controlled by the foreign government or in which the foreign government has any shareholding,” Kazi continues.

There’s a lot to unpack here. However, let’s go back to PICT and why they might have a problem with the Act and the speed at which the transaction has been carried out.

This is where the PICT comes in. This is the company that has up until now been managing these terminals. It was established as part of a $33.8 million project (Rs 9.7 arabs at a spot rate of $1: Rs 287) to establish a common user container terminal on Berths 6 – 9 of Karachi Port. This was accomplished under a 21-year Implementation Agreement between the Trustees of the Port of Karachi and Premier Mercantile Services on a Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) that lapsed on June 17.

Now, normally when any company wants to buy rights to something like a port terminal, the existing company has a right to refuse that agreement or match their price. This is a general legal principle. However, in the case of deals struck by the cabinet committee set up under the 2022 Act, this is not necessary. Essentially, the PICT can be thrown to the curb with no consequence. And that is where the legal gymnastics begin.

“This act will override any right of refusal which may exist as per contract, creating cause for PICT to sue if it is interested and has such a clause which stands vitiated,” explains Abdul Moiz Jaferii, Senior Partner at HWP LAW.

Would PICT be interested in taking up the matter? A glance at their website and earning reports may reveal their stance. “The establishment of a Negotiation Committee with the UAE for the transfer of operation and control of Karachi Port Terminals, pursuant to the Act, while PICT’s right of first refusal remains in effect, will result in an unnecessary dispute and consequent liability,” warns Sarjeel Mowahid, partner at a prominent law firm.

“The legislation should have perhaps addressed the right of first refusal,” asserts Mirza Moiz Baig, an independent legal expert. What will the Courts do? Anyone’s guess really.

“The Act possesses far-reaching implications and its stipulations and ramifications have yet to undergo judicial examination. When the opportunity presents itself, the Courts will undoubtedly interpret the provisions of the Act with due consideration to the overarching effect of the Constitution, which guarantees fundamental rights and delineates the legislative competence and executive powers of the Federal and Provincial Governments,’ explains Kazi. However, Kazi does not actually divulge what sort of verdict to anticipate.”I anticipate that the Courts will be circumspect,” Baig supplements.

The reality is that courts do not always specify every minute detail, so this can of worms will still be harder to close. Furthermore, what guarantee exists that the courts even want to become entangled in this mess? The Courts’ resolution to abstain from involvement in the recent matters of Reko Diq and this year’s privatisation petition concerning K-Electric exemplifies a court that is considerably less inclined to partake in regulating commerce. What transpires if it then proceeds to international arbitration?

“Once arbitration commences, the international arbitration regime is structured in a fashion that favours investors. It is biassed against State Governments,” elucidates Baig. Will the severity match Pakistan’s experi-

The establishment of a Negotiation Committee with the UAE for the transfer of operation and control of Karachi Port Terminals, pursuant to the Act, while PICT’s right of first refusal remains in effect, will result in an unnecessary dispute and consequent liability

Sarjeel Mowahid, Partner at a prominent law firm

This act will override any right of refusal which may exist as per contract, creating cause for PICT to sue if it is interested and has such a clause which stands vitiated

Abdul Moiz Jaferii, Senior Partner at HWP LAW

ence with Reko Diq? “I do not believe this is a repetition of Reko Diq,” declares Baig. “Nonetheless, it is intriguing because if it advances into arbitration, two foreign parties will be implicated. It will not solely involve the Pakistani government. It will encompass the Pakistani and UAE governments, and the PICT,” Baig muses.

Is a potentially costly legal battle all that is wrong with this Act then? It’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“Disregard the legal validity or invalidity of the first right of refusal,” asserts Jaferii. “Merely the concept of enacting legislation for such a financial fire sale and proclaiming that the SECP is inapplicable due to its role as guardian of companies’ interests. No competition commission applies because its purpose is to regulate monopolies. No regulator complies because their mandate is to regulate shareholders’ interests,” he explains. “When such notions are committed to paper, what message is being conveyed?” he questions. “Essentially, it is an admission of desperation and disregard of proper form and procedure,” lambasts Jaferii.

A counterargument to Jaferii’s statement would posit that foreign entities are already reticent to invest in Pakistan and require some form of enticement. Revisiting Etisalat’s acquisition of PTCL, it still mired in pursuit of $800 million (Rs 229.6 arab at a spot rate of $1:287 Rs) for some properties to this date. Had that transaction been monitored by this Act, Etisalat might have entirely circumvented the entire debacle.

However, since that transaction was governed by the Privatisation Commission Ordinance, public bidding ensued. Bidders included other behemoths such as China Telecom and Singtel. Etisalat did not initially have the highest bid but increased their bid to emerge victorious. Had that transaction fallen under the purview of this Act, none of these public bids would have transpired.

“The law should have perhaps mandated that the Cabinet Committee first conduct market research to ascertain that the price being met by the counterparty is commensurate with the market price,” states Baig.”There’s no obligation on the guarantor to first confirm the appropriate amount. It’s essentially the Cabinet’s word. The Cabinet’s word is treated as the gospel,” he explains.

“While foreign investment is indispensable, it’s paramount to ensure that national assets are not being compromised and that they are not being undervalued,” asserts Baig. He also poses another inquiry: “I can fathom the necessity for investment, but if there is a local investor willing to meet the price, would

they have a prerogative of first refusal or any preferential treatment?” Baig ponders.

Returning to Jaferii’s critique. “If you acknowledge the regulator as an impediment to even the government wanting to negotiate with another government then surely the solution is to rectify that regulator?, Jaferii questions. “The solution isn’t to halt its application to that particular transaction. It is instead to amend your regulators so they cease being forces of obstruction to everyone. If there was proper progressive thinking along the lines of reform then you would desire the regulator to ease up on everyone, and not to not apply to this one transaction because you require money expeditiously or are trying to appease a purchaser,” Jaferii elaborates.

You would think this would be the end, right? Like there’s nothing more wrong legislators could do when drafting something of this nature? If only. There is also a final point to talk about in regards to the Act. It just so happens that it is also the elephant in the room.

You’re probably wondering in this entire legal tirade why this Act is even that important? Legislation is passed all the time. That is why we have a Parliament after all. This is perhaps even a one-off transaction. In a clash with other legislation, all parties can probably sit down and sort the mess themselves. Right? Normally, yes. Only, like we said at the beginning in trying to be efficient, the Government might have just become too efficient and possibly created something they themselves have no clue about.

“There is a non-obstante provision. In law, we call provisions like Section 10 of this Act a non-obstante provision, whereby the Act prevails over other statutes and instruments having effect by virtue of any law,” explains Kazi. “If there’s any inconsistency between this Act, and another, this Act

will apply because of that non-obstante clause,” Baig adds.

“When you insert a non-obstante clause stating nothing will apply. It’s facile to say, but those rules and regulations and laws which are being nonchalantly ousted exist for a reason. They exist to police, they exist to safeguard, they exist to regulate, they exist for betterment, for safety, for standards, for industrial progress,” elucidates Jaferii.

“If you’re merely whisking them away then your intent of doing so will be called into question. You can’t just wish away the competition commission or the SECP. It does not function like that. You can’t just paint laws black and white in this manner,” Jaferii laments.

“There also exists the intriguing question of the ramifications of any commercial agreement or transaction executed in pursuance of the Act on the rights of parties under extant leases, concessions and other contracts,” muses Kazi. Herein is the main question. What happens when more deals are struck under this Act? There might be a legal landmine even if some amicable agreement is reached with PICT if the use of this Act becomes commonplace in its current iteration. Because it will.

“When there’s a public-private partnership, they will utilise the existing laws but when there’s just a we need money and we’ll give you whatever it takes then they’ll use this law,” Jaferii adds.

“I can comprehend the necessity for a law like this, but I think the problem with a law like this is that law appears to have passed surreptitiously and hastily,” Baig ponders. “It’s about the fallout of legislating in desperation,” laments Jaferii. n

Once arbitration commences, the international arbitration regime is structured in a fashion that favours investors. It is biassed against State Governments

Mirza Moiz Baig, Lawyer

On 21 June 2023, an attempt to allow the Pakistan Armed Forces to take control of and develop over 10 lakh acres of state owned farmland for corporate agriculture was struck down by a landmark judgement of the Lahore High Court (LHC).

So what is going on? Essentially, the Pakistan Army was proposing that it be handed over these vast tracts of unused state land in Punjab to develop for agricultural use. The profits from this venture would be split between the Pakistan Army and the Government of Punjab.

While plans had been underway since the start of the year, the matter first came to prominence in March 2023 when a notification marking the first transfer of land was floated publicly. Almost immediately the joint venture between the army and the provincial government was challenged in court over two basic points: can a caretaker government take such decisions and what interest and relevance does the army have in corporate farming?

The case went to the LHC and was struck down. While Justice Abid Hussain Chatta’s verdict nips this venture in the bud, the judgement is subject to further appeals and the matter could go to the Supreme Court of Pakistan. With the final decision over the agricultural development of such vast tracts of government owned land still up in the air, it is worth looking at what this whole case is about, and what the economic aspect of corporate farming can be.

Let us take a step back and look at how the courts arrived at this judgement. Back in February this year, Geo reported that the director general strategic projects of the Pakistan Army had written to Punjab’s Board of Revenue requesting access to 10 lakh acres of unused agricultural land owned by the government.

The letter claimed that the Pakistan Army had experience in developing barren land, and wanted to utilise this unused land given the rising cost of basic food commodities such as cooking oil which is largely imported into Pakistan. The idea was that the military would start farming on unused land and improve Paki-

stan’s food security problem — a very real issue particularly considering the country is now a net importer of food despite having vast agricultural potential.

Now, the government of Pakistan does not really farm. Despite being heavily involved in the agricultural sector in different ways, such as by setting targets and providing incentives and support prices, the government’s own participation in the agricultural sector is slim. Because there are no government owned farms to speak of, the drive to promote research and development is low and bureaucratic understanding of how farming works as a sector and its unpredictability

Besides this, Pakistan also has a deep rooted problem of land ownership. Five per cent of bigwigs possess 64% of Pakistan’s farmland while 50.8% rural households are landless. Theoretically, it would not be a bad idea for the state to run some farms if just to better understand the issues plaguing the largest sector of the economy. However in this particular case the government was handing over land to the armed forces to develop and use for corporate farming.

But there were also a number of jurisdictional issues with this request of the Pakistan Army. Punjab’s Board of Revenue is responsible for increasing production and money making enterprises in the province. The understanding between the Punjab government and the army was that 10,000 to 15,000 acres of irrigated land would be released immediately for the military to take control of, followed by one lakh acres by March 1 and then the rest of the 10 lakh acres by April.

The lease would be for a period of 20 years, and 20% of the profits used would be put back into research and development while 40% and 40% of the overall profits would be split between the Pakistan Army and the Government of Punjab. This is where the problems start.

The first part of the issue was that the Board of Revenue is an instrument of the provincial government and its chair is a provincial minister. Since Punjab is currently being run by a caretaker setup, the constitutional mandate of this government is limited. The second issue of course was whether the armed forces could request the allotment of such land for a profitable purpose such as corporate farming.

Corporate Agriculture Farming is a practice usually undertaken by large companies looking

to enter the agricultural sector. They purchase or lease land on a grand scale and then develop farms for experimentation and sometimes to grow products that they might need for their other businesses. A manufacturer of cornflakes, for example, might want to grow corn.

However, corporate farming itself can have many drawbacks. Primarily it is a profit making enterprise. Back in 2013 the then President of the Society for Conservation and Protection of Environment (SCOPE), Tanveer Arif, had explained at an event how corporate farming was initiated in Pakistan during former President Pervez Musharraf’s government which was against the rights of farmers. “Some Gulf countries had purchased lands in Pakistan, particularly in Sindh and Balochistan, that would cause water scarcity and deprive local farming communities of their rights.”

Up until around March 2023, the entire venture was still theoretical so not quite subject to any legal challenges. Then came a notification from the General Headquarters Lands Directorate in Rawalpindi titled “Corporate Agricultural Farming (CAF) Handing Over of State Lands.” The document heralded the decision of handing over 45,267 acres of land from Bhakkar, Khushab and Sahiwal to the Pakistan Army as the first phase of this plan.

“While signing the JV Management Agreement on 8 March 2023, it was decided that State Lands immediately required for the project be handed over to Pak Army,” read the notification. The land allotments mentioned in the notification include 23,027 acres of a protected forest called Rakh Goharwala, a land of rich biodiversity and a range land with plentiful presence of the black buck.

In response to the notification, a writ petition opposing this decision was filed by lawyers at Public Interest Law Association of Pakistan (PILAP). Advocates Ahmad Rafay Alam, Fahad Malik and Zohaib Babar represented PILAP. Ahmad Rafay Alam, an environmental activist and a prominent lawyer who has been involved in several public interest litigations in the past, told Profit that it was a viral social media post coupled with a Dawn article published on 17 March 2023, on the basis of which he and his colleagues built the argument for the case.

“This petition took from one week to ten days to file because by law, you can not file a pe-

A joint venture between the Punjab Government and the Pakistan Army to farm 10 lakh acres of barren land has been struck down by the LHC. What does it mean?

tition against the army or name any members of the armed forces in your petition. And so finally the hearing was set for 29 March 2023 and that is when Justice Abid Hussain Chattha issued a stay order against any further transfers ordered by the federal or the provincial government,” he said.

The notification raised many eyebrows and questions against this joint venture. However, it must be noted that during the proceedings of this case it was revealed that this notification is a part of a much larger joint venture management agreement which had already received the caretaker cabinet’s approval by 9 February 2023.

Ironically, the Joint Venture Management Agreement, signed on 8 March 2023, was issued under the “Colonisation Act” of 1912 which was first put in place by the British Raj of the 20th century subcontinent. “This act is the reason we all live in Punjab, it is how the British inhabited this region. This act means that a part of Punjab’s land can be taken up by the government and a policy for its use can be issued. But it can also result in large-scale displacement of people, as it did in its application during the construction of the Mangla and Tarbela dams, or it can result in land ownership for small farmers through policy small holdings schemes, depends on how it is deployed” said Alam, commenting on the essence of this legal framework. “Essentially, it gives an absurd amount of power to the provincial

government to be able to do with the land as they wish.”

During the case proceedings it was also revealed that the government had proposed to initiate a CAF agreement with the army back in 2021 when the Colonies Department of the Board of Revenue, Punjab submitted a summary to the elected government on 25 June 2021 proposing a Statement of Conditions (SOCs) for this joint venture. These SOCs were discussed by the government in a meeting on 28 February 2022, under the agenda point titled “Conditions for Corporate Farming under CPEC”. This is when Usman Buzdar was the chief minister of Punjab.

Commenting on the association of this venture with CPEC, Alam said “CPEC is not just about giving Pakistan energy infrastructure but also developing agriculture for the Chinese markets. In 2021, the government was considering ways to allow for Chinese investment to pour into the country. Although this joint venture would allow for companies incorporated in Pakistan to be given leases on auction, the court highlights that the necessary procedures for such a decision were not carried out.”

The judgement concludes and Alam concurs that the ministerial committee created for the finalisation of this joint venture never met and the minutes of this meeting were suspicious-

ly never recorded. The government was unable to furnish any evidence in court to prove that this meeting did happen. In fact, when Justice Abid Hussain Chattha specifically inquired into the matter, he was told by the government’s counsel that Raja Basharat, then Minister for Cooperative Environment Protection and Mohsin Leghari, then Finance Minister attended the meeting however the former forgot to sign the attendance sheet and later Leghari expressed forgetfulness about the meeting.

The judgement held that the initiation of any agreements drawn up under this venture are “unlawful” and “of no legal effect and are set aside, accordingly.”

In his judgement, Justice Abid Hussain Chattha highlighted that all state land shall be reverted back to the government. Additionally it said, “It is declared that the Caretaker Government lacks constitutional and legal mandate to take any decision regarding CAF initiative and policy in any manner whatsoever, in terms of Section 230 of the Elections Act.”

“It is declared that the Armed Forces including the Pakistan Army and/or its subordinate or attached Departments/ offices lack constitutional and legal mandate to indulge and participate in CAF initiative and policy in terms of Article 245 of the Constitution.”

In short, the judgement very clearly declared that not only does the caretaker government have the mandate to allot land for such a venture, the armed forces do not have the constitutional and legal mandate to indulge in corporate farming.

Celebrating the win, Advocate Fahad Malik tweeted “The honourable Court held that taking such major policy decisions was beyond the scope of powers available to a caretaker government under the Constitution and the Elections Act. The honourable Court was also pleased to hold that the Armed Forces of Pakistan cannot undertake ventures such as [CAF] being beyond their Constitutional and legal mandate.” n

“This petition took from one week to ten days to file because by law, you can not file a petition against the army or name any members of the armed forces in your petition. And so finally the hearing was set for 29 March 2023 and that is when Justice Abid Hussain Chattha issued a stay order against any further transfers ordered by the federal or the provincial government”

Ahmad Rafay Alam, lawyer

“The honourable Court held that taking such major policy decisions was beyond the scope of powers available to a caretaker government under the Constitution and the Elections Act. The honourable Court was also pleased to hold that the Armed Forces of Pakistan cannot undertake ventures such as [CAF] being beyond their Constitutional and legal mandate”

Fahad Malik, lawyer