08 Pakistan’s political turmoil might derail the country’s tech ecosystem 12

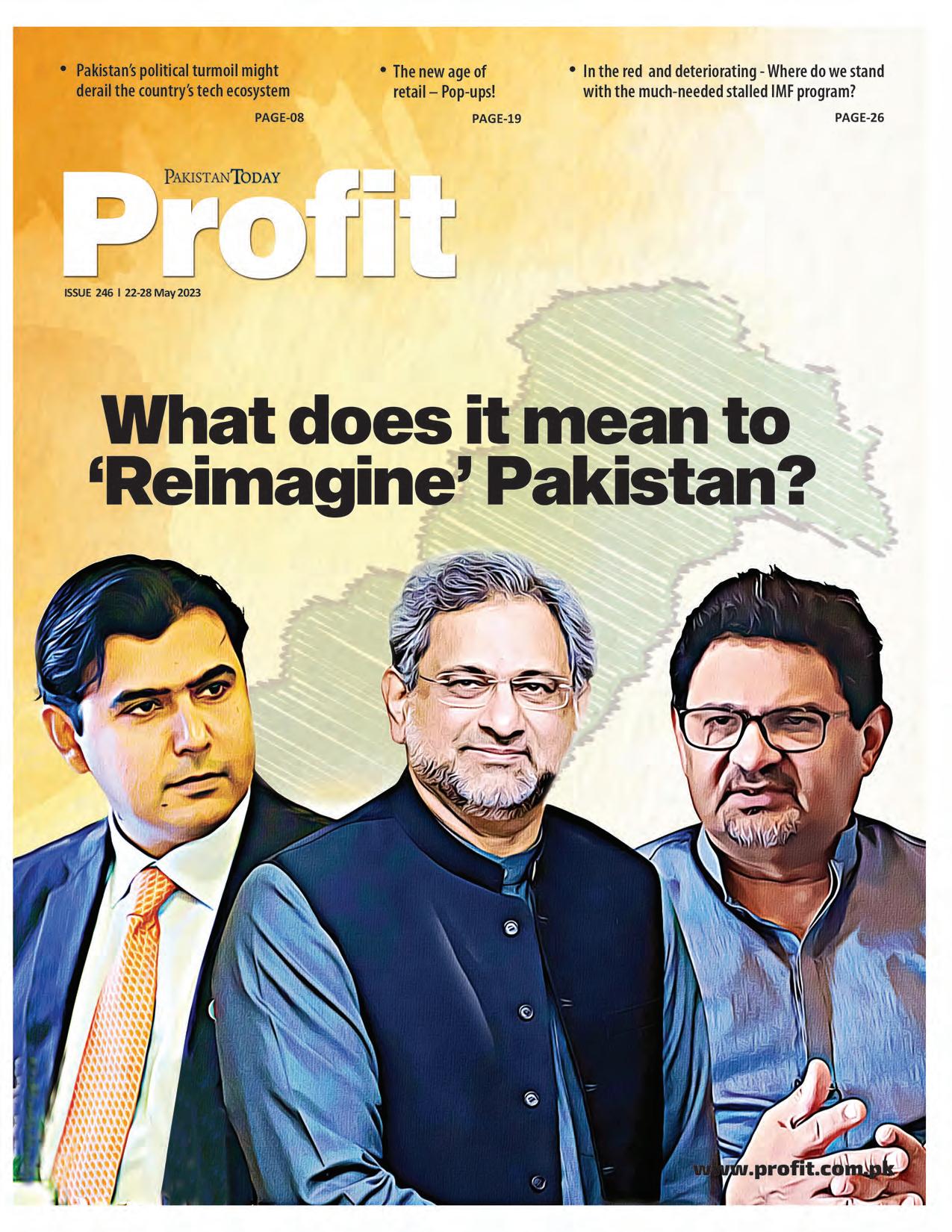

12 What does it mean to ‘Reimagine’ Pakistan?

19

19 The new age of retail – Pop-ups!

24

24 Demographic liability Ammar H. Khan

26 In the red and deterioratingWhere do we stand with the much-needed stalled IMF program?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Nisma Riaz and Daniyal Ahmad

By Nisma Riaz and Daniyal Ahmad

What makes the perfect pitch deck for a Pakistani startup? It’s a delicate balance of statistics, and storytelling. On one hand, you have the impressive numbers - 220 million people, while on the other, there’s a young population bursting with potential, cheap mobile data, and high internet penetration. In a perfect world, all these features of our local market make for a highly persuasive pitch, causing investors to quake in their seats with uncontained excitement. But there’s a catch.

Underneath the shiny surface, there are challenges that come with being a developing country. What happens when the internetthe lifeblood of any tech startup - becomes a bargaining chip in political power plays?

Of course, a leaf from the perfect pitch tree withers and falls to the ground.

Navigating Pakistan’s tech landscape

is no different than playing a game of Jengaone wrong move and everything could come crashing down. Last week’s political drama just made the game even harder. Within just a day of former prime minister Imran Khan’s arrest, its resultant violent protests, and suspension of mobile internet; point-of-sale transactions fell by around 50%. When cash payments become the country’s only mode of transaction for over a week, it can hardly be considered an attractive region for venture capitalists (VC) to invest in. Profit hit up local and foreign VCs, and startups to get their insights on how this new development is affecting their investment decisions.

Profit has compiled a list of startups eager to share not only their thoughts on the recent mobile Internet blackout, but also the numerous challenges they faced while striving to keep their businesses

running without the crucial tool they rely on. These were their responses.

Kassim Shroff Co-Founder and CEO, Krave Mart

“During challenging times, one might have expected a surge in orders. However, our business and growth prospects were adversely impacted by the outage, causing disruptions to our operations. Our riders heavily rely on navigation services, and faced prolonged connectivity issues with support and customers.

To combat this, Krave Mart assigned additional rider support agents to enhance the delivery process. Meeting the increased demand without escalating costs proved to be quite challenging. We consistently sought ways to optimise operations, priori -

tise rider safety, and support our customers. A founders committee was also formed to strategise corrective measures for future crises.”

Representative from the ride-hailing industry

Aspokesperson from the ride-hailing industry stated that, “The suspension of mobile internet services severely impacted ride-hailing businesses. We were saddened that we were unable to serve our customers and drivers who relied on us for their daily travel and to earn their livelihoods. We hoped we could return to serving them as soon as possible. A reliable, functioning internet service is vital to a functioning and prosperous economy.”

Halima Iqbal Founder & CEO, Oraan

Founder & CEO, Oraan

e are in the B2C business and were severely impacted by the internet blackout. On the operations side, our members struggled to pay their dues due to the inability to conduct digital transactions. On the growth side, new customers found it difficult to take up the product. Our numbers were down by 40%!”

“We received expressions of concern from both current and potential investors. Internet access is a fundamental requirement for conducting our business, and any disruptions to it are of great concern. However, we remain optimistic that common sense will prevail and that such incidents will be avoided in the future.”

“The mobile broadband suspension significantly affected Foodpanda’s operations. The suspension caused disruptions in the delivery process, leading to significant inconvenience to our customers and degradation of the customer, rider and vendor experience due to failed orders, delays and cancellations.

We continued to work with our partners to improve access to internet connectivity and leverage our own infrastructure, but the resumption of mobile broadband was critical for a return to business as usual. If the suspension had persisted for an extended period, it could have resulted in continued financial losses for all stakeholders engaged on the platform.”

These comments are tell-tale of the fact that mobile broadband suspension has thrown the operations of several tech companies into disarray. Despite their efforts to proactively power through this crisis, it has been impossible to protect their revenues from taking a hit. There is only this much one can do, when the most essential paraphernalia for their business gets snatched away from them, without so much as a heads up.

Surviving tough times is one thing, but the internet blackout hit where it hurts. We’re talking about the gut-wrenching panic and uncertainty that comes when tech companies operate in a country like Pakistan, but are answerable to investors who are worlds apart from Pakistan and its never-ending political and economic chaos.

“WThese were the sentiments of some tech startups Profit reached out to.

Muneeb Maayr Founder, Bykeaven though no concerned investors inquired about the situation, everyone has been talking for a few months about the devaluation of the currency impacting their dollar investments. Pakistan is increasingly being looked at as a risky destination to invest in. Investors invested in USD, but with revenues in rupees, their dollar return on investments looks bleak with a rupee that has devalued almost 100% over the past year.”

Saud Rashid COO, Cheetay“Stability — political and economic — is something that investors are always concerned with, but that is weighed against potential. In our view, Pakistan has great potential and we share that vision with investors. However, it is much easier to engage with people who are familiar with Pakistan than those who have only heard negative news. Our investors were aware of the situation in the country and were mindful of the hindrances it could have caused our business if it was not resolved soon.”

“At present, we are not actively seeking capital and have not made any pitches to new investors. However, in light of the shutdown, we recognised that addressing this issue will be a significant challenge in any future pitches. We are also aware of our dependence on telecommunications companies and internet service providers in the country; thus, our reliance on their uptime and digital services will remain substantial.”

“T“Ehe current geopolitical situation presents challenges in promoting Pakistan’s startup potential. Two years ago, our story catalysed investment in frontier markets. We believe Pakistani startups have the potential to attract billions of dollars in investment, create jobs and advance the economy. However, we now face lower valuations and longer investment timelines. Despite this, Pakistan still offers attractive returns and its story will resurface once the political situation stabilises.”

What we gather, from the looks of it, Pakistan is like a child from a broken family — bursting at the seams, with undeniable potential but lacking the stability to actually do something with it. As it stands, Pakistan’s tech industry has come this far because it offers a promising future, nonetheless, it remains a highly risky market, which might deter riskaverse VCs from investing.

To run a business in this market is one thing, to raise capital and piling it into startups knowing the risks is another. It’s not for the faint of heart to say the least. However, what goes on in the mind of someone who knows their capital could either strike them gold or go down the drain, if those they bet on fail to navigate the chaos?

Profit reached out to local, and international, VCs to ask just that.

enture funding in Pakistan, like all emerging markets, is influenced by both domestic and international factors. Rising interest rates and global macroeconomic uncertainty have increased the cost of capital for startups and caused international investors to retreat to their home markets. This has been compounded by Pakistan’s domestic economic and political instability. However, we believe that now is an opportune time to develop transformative solutions, as both consumers and businesses face challenges that can be addressed through technology. The long-term investment opportunity in such a large market that is rapidly transitioning from offline to online is attractive. We remain committed to supporting our existing portfolio companies and new investments through these short-term challenges.”

Mattias MartinssonCIO & Founding Partner, Tundra

Fonder AB

Fonder AB

he internet blackout raised concerns among local partners, but thankfully fixed lines remained mostly operational. The investment climate is dependent on the normalisation of the political situation and the holding of elections. The uncertain political climate has had a negative impact on investor interest, funding and valuations. Venture capital funding is diminishing due to the added uncertainty arising from political risks. Predictable economic management and the maintenance of democratic processes are necessary to attract more funding.

“VThe macroeconomy and political climate play a significant role in investment decisions. Many Pakistani companies have weathered recent troubles well, but the current investment climate does not encourage new investments. Investors require predictability and are likely to adopt a wait-and-see approach until this is achieved.”

Additionally, the time it takes to close a funding round has increased.

These are all factors that founders should consider when deciding whether to raise funds in the coming year. They should allow for the time it will take to raise funds, be conservative in their pricing and broaden their pool of potential investors, knowing that many may decline.”

Shehryar Hydri Managing Partner, Deosai Ventures

ncertainty and a global economic squeeze harm the ecosystem. Money leaves emerging markets first, causing a slowdown. Socio-political cracks make even risk-taking investors apprehensive. However, venture capital is high-risk and our market can deliver outsized returns. Investors with dry powder and appetite can find deals with asymmetric risk profiles, but they are few. Founders report sharks offering bad terms due to tough times and scarce capital. Startups must cut costs, strategize smartly, and avoid painful bed-mates to survive and grow.” “International emerging market investors know the risks and potential upside of markets like Pakistan. The internet is essential for growth and development.”

“TKalsoom Lakhani

Co-Founder

& General Partner, I2i Venturese have experienced a significant decline in international venture capital funding. I anticipate that this will worsen due to Pakistan’s political and economic instability. Although funding rounds will still occur, they are likely to be smaller on average, with lower valuations.

“O“Uur local partners in Pakistan were concerned about the impact of the internet blackout on investment and operations. As a Pakistan-focused fund, this affected us significantly. 90% of foreign investors left due to the market slowdown and the change of government in 2022. They plan to return when conditions stabilise, but rash decisions such as this can damage our global reputation.

The investment climate is uncertain, with recent arrests and the targeting of the PTI causing investors to pause major investments. Some may exit or relocate operations outside Pakistan, while others will adopt a wait-and-see approach. Despite venture capital’s resilience to risks, funding in Pakistan is diminishing due to the global slowdown and political instability, indicating a pessimistic long-term outlook. We had hoped that we would only lose 1-2 years, but unfortunately it now appears that recovery will be a 3-5 year process.”

“WRabeel Warraich Founder & CEO, Sarmayacar

“The internet blackout had a negative impact on operations and will also have a negative impact on fundraising. Companies such as

We are in the B2C business and were severely impacted by the internet blackout. On the operations side, our members struggled to pay their dues due to the inability to conduct digital transactions. On the growth side, new customers found it difficult to take up the product. Our numbers were down by 40%!

Halima Iqbal, Founder & CEO, Oraan

At present, we are not actively seeking capital and have not made any pitches to new investors. However, in light of the shutdown, we recognised that addressing this issue will be a significant challenge in any future pitches. We are also aware of our dependence on telecommunications companies and internet service providers in the country; thus, our reliance on their uptime and digital services will remain substantial

Qasif Shahid, Co-Founder & CEO, Finja

Bykea operated at reduced capacity due to the lack of mobile broadband, while other startups struggled to acquire customers due to blocked platforms. This hinders growth and jeopardises investment rounds. The investment climate in Pakistan will remain challenging until stability returns. If internet blockages persist, attracting new investors will be difficult.

Globally, venture capital funding has decreased. Pakistan’s elevated risk means it is losing out to safer destinations. However, we knew this would not be a permanent situation. Pakistan’s demographic dividend and low penetration of venture capital funding offer attractive investment opportunities. We must navigate the current environment with resilience and capital discipline in order to capitalise on future opportunities.”

Ahsan Jamil Managing Partner, sAi Ventures

t goes without saying that the impact was quite detrimental. It reinforced the negative perception that political uncertainty has an adverse effect on business, which is worse than the transactional disruption of the past few days. In the short term, both global macroeconomic factors and domestic political uncertainty are likely to affect investment inflows.

Rather than focusing solely on international and foreign investment, it would be more pertinent to examine why local investment is not supporting technology to a greater extent. When local capital oversubscribes to an opportunity despite local macroeconomic conditions, international capital is likely to follow suit.”

Salaal Hasan Director of Venture Capital, at JS Groupakistan’s growing digital economy attracts venture capital and foreign investment due to its large population of cellular and internet users. The IT and IT export services industry can address economic issues such as inclusive growth, dollarised exports, investment attraction, and job creation. However, internet bans hinder innovation and contribute to brain drain.”

“The investment climate in Pakistan is fragile due to high interest rates, inflation, lower liquidity, and currency devaluation. Mixed signalling and lack of clarity on initiatives like the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) impact investor confidence. As global markets correct in 2024, policy makers must support entrepreneurs and investors.”

“IVCs walk a tightrope, balancing risk and reward. Their concerns and anguish are on full display. They must have nerves of steel when their money’s on the line. The nerves may be a facade or false bravado, but they know they’re in it for the long haul to make a return on their investment. They’ve told us as much. Yet, they’re painfully aware that their lives have been made harder through no fault of their own.

Saad Saleem, Co-Founder and Managing Director at Nayatel, divulged that “On May 9, mobile internet and specific social media sites were blocked. Mobile internet services were restored on Friday night, May 12; however, social media sites remained restricted. Access to blocked social media sites resumed on May 16.”

“Despite users lamenting the sluggish pace of the newly restored broadband,” Saleem continued, “sources revealed that there was no throttling when internet access was restored.

The only disruption was in social media sites that remained blocked and could only be accessed through a VPN. However, there is an explanation for the subpar quality of internet connection across the country after its temporary suspension.”

“PSaleem further elaborated that “There can be side effects of this blocking because many sites embed content from different media sites. Ad insertions and video embeds from different media sites can cause issues. For example, if a site has a YouTube video inserted in its web page, it might cause the page to load slowly or timeout on the video links.”

Saleem shared additional reasons for the subpar service after restoration. “The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) installed a web management solution (WMS) device to monitor traffic and surveil internet activity. The device crashed due to high traffic after restoration, causing sporadic connections and interruptions for users.”

It seems that the penny has finally dropped: the internet is kind of a big deal for keeping an economy afloat. So, when decision-makers get trigger-happy and sever mobile internet connections, the fallout can be a real doozy. One can hope our leaders have learned their lesson and won’t make the same blunder again.

“The internet is the backbone of most technological applications that startups rely on. Curtailing internet connectivity was not responsible, given the cost benefit to disruption of an already challenging economic landscape” Bawany tells Profit

Pakistan does not come without baggage. With never-ending political challenges, outdated policies and several overarching macroeconomic challenges, we make for a market that proves to be a far riskier playground for investors. All of which is now aggravated by a trigger happy State that can’t decide whether it wants the startup, and VC space to triumph or tumble?

Whilst we don’t know whether the State ponders over this decision, founders and VCs alike will just have to fatten their deck with a slide on internet outages. n

There is little reason to be surprised by how quickly the Pakistan Tehreek i Insaaf (PTI) has disintegrated. At the end of the day it took one firm push from the powers that be to corner Imran Khan, put the party’s top brass behind bars, and send its rank and file ducking for cover.

What is surprising is that it took this long. Almost immediately after he was sent packing through a vote-of-no-confidence Imran Khan and his PTI positioned themselves as the anti-establishment party. Initially, the PTI managed to hold its own. Many politicians otherwise famous for party-hopping stuck around behind Imran for two reasons — The first being it was apparent he commanded popular support and PTI tickets would be a valuable commodity in any upcoming elections (something that became crystal clear in ensuing by-elections where the PTI swept the polls). The second was that a change was due in military leadership.

Six months after this change of guard in the high-command, the regular culprits are fast deserting the party with the events of the 9th of May proving to be the final straw. The result is clear — even if elections take place any time soon the PTI will be severely hamstrung giving their political opponents an edge. However there is a bigger crisis that seems to have been forgotten in the ruckus of this political tsunami.

The economy has almost entirely collapsed. Today, Pakistan once again stands dangerously close to default. Negotiations with the IMF have dragged on for months, the government is fighting a losing battle on the economic front and is governing with a sword hanging over its head because of the political uncertainty that continues to plague the country. April saw more of the punishing inflation characteristic in the last couple of years, with a record 36 percent rise year-on-year. The month’s increase was 2.4 percent, and the year-

on-year inflation last month was 36 percent, marking the 11th month since last June that inflation was above 20 percent.

On top of this, doing business has become near impossible and every human development indicator points towards a country that desperately needs the reset button. Tough decisions need to be made and that requires level-headed governance with the guarantee of political will.

Who can provide that? The PTI, which would have easily been frontrunner for any election taking place in the country right now, is handicapped with its leadership either in jail or in flight and its rank and file terrorised by the force of the state. The PML-N, PPP, and other parties part of the PDM government are deeply unpopular. That leaves a political vacuum that needs to be filled. Space for a ‘fourth’ option so to speak.

What form could this new political force take? Some might point towards the Reimagining Pakistan platform launched at the beginning of 2023 by former prime minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, former finance minister Miftah Ismail, and former PPP senator Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar.

On the surface the ‘Reimagining Pakistan’ platform is a series of seminars and talks meant to initiate a conversation about pressing economic and governance issues facing the country. Yet, this trifecta of political mavericks are doing more than a simple exercise in political consensus building. Miftah, Abbasi, Khokhar and the crowd of moderate, mainstream politicians that are riding the Reimagining Pakistan wave have come to represent a side of Pakistani politics that appeals to the educated, urban audience looking for stability and steady thinking.

There have been rumours, of course, that the Reimagining Pakistan platform is an attempt to gain enough steam to launch a new political option — an enlightened ‘fourth’ option so to speak. In conversations with Profit, the leaders of the platform as well as senior politicians have not denied this possibility. Largely, however, it seems to be resistance to

the status quo coming from within the traditional political elite. The question is, how far can they go without the support of their parties? And in the current political climate is the concept of consensus reaching for the stars?

In June 2022, Miftah Ismail was running the most important negotiation of his life. No business transaction in his career as a Seth or any budget he presented in his first tenure as finance minister held as much weight or significance as the hard-fought deal he was trying to strike with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The task that Miftah faced was gargantuan. Pakistan was close to default and negotiations with the IMF had been stalled because of the expensive fuel subsidy that the PTI government had put in place to keep the price of petrol at Rs 150 per litre.

By July, the negotiations bore fruit and the IMF released the pending tranche of money that Pakistan desperately needed to keep its economy running. It had been an up-hill battle but Miftah persevered and it seemed the storm had passed and the economy was under relatively safe stewardship.

By September 2022 he was out of office. There were many challenges and obstacles in Miftah’s way during his brief but important time as the main man in Q-block. But the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune he was constantly ducking and weaving away from were not just from the opposition or the IMF – they were coming from home.

From the very beginning, Miftah was a man abandoned by his own party. In the first few days of the PDM government coming into power, Miftah made it clear that his plan was to cut the fuel subsidy and bring petrol up to its actual price for consumers. Despite this being a major sticking point in negotiations

I am very disappointed with the country’s political system which has failed to address public problems in the last seven decades. The nation has to choose between rotten thinking and changing the destiny of Pakistan. That is what we want to do with this forum. To pool our resources to get a conversation started

Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, former prime minister of Pakistan

with the IMF, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif dragged his feet on the issue. And even while talks were reaching a critical juncture, there was a constant effort from one side of the PML-N that was promoting the replacement of Miftah Ismail by the now finance minister Ishaq Dar. The party’s supremo, Mian Nawaz Sharif, reportedly left a zoom meeting after Miftah raised the price of petrol products and Dar had been on a mission to see himself back in the finance minister’s chair from day one.

And he was not the only one facing such treacherous waters in his own backyard. Former prime minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, Miftah’s friend and the man in whose cabinet he first served as finance minister, had similarly had a falling out with the PML-N when Maryam Nawaz was appointed to the post of Senior Vice President of the party — an office that Abbasi formerly held. There was also Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar of the PPP, who had resigned as a senator in November over his ‘principled’ political stances that had gone against party policy.

Together, these three joined forces and founded the Reimagining Pakistan platform. Reliably placed sources close to all three have confirmed that their aim was to very quickly announce the formation of a new political party that would carve out an 8-10 seat mandate for itself in any upcoming election. Their target was to be the ‘rational’ party that the urban, educated, moderate Pakistani could get behind.

It seems, however, that at different points Mr Abbasi has gotten cold feet in taking the plunge and the moment may have passed given how volatile the political situation has become. The question is, what could a hypothetical political force such as this have to offer? The answer, perhaps, lies in the term ‘reimagining.’

“Where did the name come from? Well it started with a simple conversation really. Mustafa and I were discussing how our governance and management structures need rethinking. How we have abandoned 99% of the population for the benefit of the 1% and that’s when Mustafa suggested our platform should be called ‘Reimagining Pakistan,” Miftah Ismail tells Profit.

But what does it mean to reimagine? As a term it has been used ad nauseam. Thinkers, scholars, academics, public intellectuals, and talking heads have all attempted to ‘reimagine’ everything from the internet to the wheel. But it cannot simply be a matter of reverse engineering a problem and going back to square one. In its essence, to reimagine is to rebuild from the beginning on a new foundation.

“What we are suggesting is radical change. Pakistan’s entire system of governance and economic management is broken. Its very foundations are weak and crumbling. That means making sure we make moves that we can realistically implement and cut down on our spending,” says Miftah Ismail. “Humay apne paer chadar dekh kar phelanay chahiay hain” he adds.

But there is a problem with this narrative. There is nothing particularly radical about the interventions being discussed. In the shortterm they suggest cutting down expenditure and in the long-run the suggestions include civil service reforms, implementation of local governments, stepping away from foreign aid, increasing exports, and increasing the reach of the tax net particularly by taxing agricultural and real estate land holdings.

None of these are ideas that have not been suggested before. So what is there to reimagine in Pakistan? “I am very disappointed with the country’s political system which has failed to address public problems in the last seven decades,” said former prime minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi. “The nation has to choose between rotten thinking and changing the destiny of Pakistan. That is what we want to do with this forum. To pool our resources to

get a conversation started.”

And that is essentially what this entire reimagining exercise comes down to. For the past 76 years Pakistan has been stuck in a rut. The architects of this state have failed to create a nation that is self-sufficient and just. So what has been the legacy of this country since 1947?

Pakistan today is an undeniable reality and an inextricable part of the global world order. This longevity was not always guaranteed, and at least for the first decade the very existence of the world’s first independent Muslim state was doubtful. Yet, beyond this very obvious exercise in perseverance, there is little else to show for. Democracy has failed to take root, with military rulers exercising de facto and de jure rule for 32 years. More than half of the country was lost in 1971 with the independence of Bangladesh. Social turmoil, a bad relationship with debt, a boom-and-bust economy, and a tired political system have all been part of the package.

The successes have been few and far in between. Isolated moments of individual brilliance such as the 1992 cricket world cup or Nobel prize laureates such as Dr Abdus Salam and Malal Yousafzai have been a source of pride. There have also been notable political victories, such as the passing of the 1973 constitution and the 18th amendment to that constitution in 2008. The lows have been abysmal and regular.

Pakistan’s Human Development Index value for 2021 is 0.544— which puts the country in the Low human development category—positioning it at 161 out of 191 countries and territories. Between 1990 and 2021, Pakistan’s HDI value changed from 0.400 to 0.544, a change of 36.0 percent. The great irony of this, of course, is the fact that this index on which Pakistan finds itself slipping fast was in fact developed by a Pakistani — Dr Mahbub

What we are suggesting is radical change. Pakistan’s entire system of governance and economic management is broken. Its very foundations are weak and crumbling. That means making sure we make moves that we can realistically implement and cut down on our spending. Humayapnepaerchadardekhkar phelanaychahiayhain

Miftah Ismail, former finance minister

ul Haq, who created HDI in 1990. The index was then used to measure the development of countries by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

On the Gender Development Index (GDI), which measures gender gaps in achievements in three basic dimensions of human development: health, education, and standard of living, Pakistan shows a massive gap. The 2021 female HDI value for Pakistan is 0.471 in contrast with 0.582 for males, resulting in a GDI value of 0.810, placing it into Group 5, making it part of an unenviable group of countries that includes Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Afghanistan. Meanwhile on the Gender Inequality Index, Pakistan ranks 135 out of 170 countries.

In 2021, the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index ranked Pakistan 130 out of 139 countries. Pakistan ranked second-last in South Asian countries behind the likes of Nepal, Sri Lanka, India, and Bangladesh. Only Afghanistan was ranked lower. In particular, the report showed Pakistan doing badly in the areas of corruption, fundamental rights, order and security and regulatory enforcement.

On the economic front Pakistan faces a crisis the likes of which it has not seen before. The country has been hanging on by the skin of its teeth to avoid falling into the abyss of default. Most affected by this have been the most vulnerable segments of the population whose purchasing power continues to plummet.

At a recent Reimaging Pakistan conference hosted by Government College University Lahore, Miftah Ismail made a surprising admission. He said that in the past 15 years, successive governments of the PPP, the PML-N and the PTI had all failed to fix the ills plaguing Pakistan despite making their best possible efforts.

This in itself is rare in Pakistani politics. Democracy in Pakistan is stunted because it has never been allowed to bloom or take root. As a result, political parties in the country are not ideological. Largely speaking, Pakistan’s economic management has been left to rightof-centre bankers and economists that have failed to break the country’s dependence on foreign aid. Pakistan has been living beyond its means for decades leaving successive governments to go from one fire to another with little opportunity to implement necessary reform. Think of it this way: during the PTI’s recent tenure in office, Abdul Hafeez Sheikh and Shaukat Tarin both served as finance ministers

Military budget and pensions: We need to reduce all of our expenditures. The biggest problem is how the NFC award is structured. We need to reduce the percentage that is going to the provinces because at least 60% of the tax the centre collects goes to the units while their own tax collection is very low. The debt servicing is near Rs 6000 billion. Defence budget is around Rs 1500 billion and pension bill is around 650 billion and within the next six years the pension bill will be higher than the defence bill at this rate. We need to increase taxation and reduce these expenditures. There is a separate issue of losses being made by state owned enterprises that are not even counted in the budget but eventually hit the government. These losses of mismanaged companies end up increasing our debt which goes in the debt servicing budget and that means going towards privatisation.

Banking sector: Privatisation is needed in banks as well. The National Bank is not giving better lending rates than private banks. The only reason keeping these banks around, particularly banks like the Bank of Punjab, is rent-seeking and corruption. The government should not be owning any banks at all. These banks have the highest number of non-performing loans because they are not profit oriented and the government has to re-capitalise them every few years.

Agriculture: We cannot make more land. In fact, land is shrinking because it is going towards housing and real estate. At the same time you are seeing 55 lacs new children born every year and the population rising by 45 lacs every single year. To feed these people you have to import more food. Already we import almost all of our edible oil from Malaysia and Indonesia. That is a $5-6 billion expenditure every year. We import lentils, cotton and very basic crops. We need new regulation in the agriculture industry. We must use GMO seeds wherever it is possible and provide better harvesters and planning. The farmers need to be incentivized to increase their productivity.

Investment: There is very little foreign investment in Pakistan. We get around $2 billion and didn’t even get that in 2023. Even this little investment comes from companies that want to sell products to Pakistan. We need investment where investors come in, setup industries in Pakistan, manufacture products that are then exported. We need investment that then goes outside. Until we cannot fix the law and order situation, foreigners will not invest in Pakistan.

to prime minister Imran Khan. Both men had also served in the same office under the PPP’s Gilani administration from 2008-13.

Whether Pakistan needs social democracy or aggressive capitalist expansion is a debate the country is not ready for. And as Miftah Ismail explains, the first course of action is to address the rabid inequality and governance problems in the country.

“Let’s take two examples. The first one is the issue of tax collection. No matter who has been in government they have failed to increase the tax net. We have suggested that instead of further burdening existing taxpayers, there need to be taxes levied on things such as real estate and agricultural land which is often unproductive,” says Miftah Ismail.

“Even if you come into government with the right ideas, implementation is blocked by many hurdles. As finance minister you can

walk into the office and be given a finance secretary that had only up until a few months ago been serving as health secretary. How can this person have any hope of serving in the finance ministry?”

There is a pretty clear direction that those behind Reimagining Pakistan have. These are the mainstream politicians that are tired of Pakistan’s political system. They have been in government and come to the conclusion that very little can actually be done in Pakistan. Tired of this, they are trying to create a space in which consensus can be developed over major issues that make governance and economic management difficult. “These are not original solutions we are proposing,” Miftah admits. But what we are doing is presenting and pushing our own ideas. That said, we are happy to hear other solutions and begin a dialogue.”

The platform’s critics, however, are not amused. Former KP finance minister Taimur Khan Jhagra tells Profit that while there are some good points being made through Reimagining Pakistan, the platform is flawed because it is not truly apolitical. “I think they make some sensible points but the platform is not apolitical as they claim,” he says. “The gentlemen that have been my colleagues seem to only be focused on the problems and are not providing sophisticated solutions to this. They conveniently change positions and maintain ties with their parties. If they really want to make this work, they must burn their bridges.”

That much is true. Out of the three leading lights of Reimagining Pakistan, only Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar seems to have severed ties with the PPP. Both Shahid Khaqan Abbasi and Miftah Ismail continue to maintain their party membership. However, the peace that seems to exist between them and the PML-N is a tacit one. Miftah’s statements have regularly been

thorny towards finance minister Ishaq Dar and Abbasi’s recent tirade about corruption in the free wheat distribution scheme both point towards serious fault lines.

“There is nothing wrong in creating a new political party,” says Miftah Ismail when asked about the possible development. “However, that is not our intention with this platform at all. Abbasi sahab and I have both been offered ministries but we must admit that we are tired of how the governance structures of this country operate.”

There is the old adage that in the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king. The Reimagining Pakistan platform is a flawed and incomplete concept. To be very fair to the men that are running it, they have neither claimed they have all the answers and nor have they made any

political intentions known.

What they have done is tried to start a conversation and provide necessary if old ideas for how to address Pakistan’s many ailments. Miftah Ismail, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, and Mustafa Khokhar are all traditional politicians and bear the baggage that comes with this. They are all also well-intentioned and honourable.

In the current political crisis that Pakistan faces, we will need every resource that we have which is why there may be room yet for the Abbasis, Miftahs, and Khokhars of Pakistani politics. Whether Reimagining Pakistan turns into a political party or not, it has become abundantly clear that a power vacuum is fast developing that needs to be filled. Given the state of the economy and the helplessness of the people of this country, one can only hope it is filled with competent people with lofty ideals rather than with generational politicians that go from King’s part to King’s party.

I think they make some sensible points but the platform is not apolitical as they claim. The gentlemen that have been my colleagues seem to only be focused on the problems and are not providing sophisticated solutions to this. They conveniently change positions and maintain ties with their parties. If they really want to make this work, they must burn their bridges

Taimur Jhagra, former KP finance minister

In the Urdu language, the word mela is synonymous with the word jashan. A strict dictionary definition might describe the mela as the coming together of performers and traders that create temporary encampments. It is the coming together of shopping and entertainment. A travelling mall on wheels so to speak.

But the implications of the mela go beyond just an exercise in commerce. It is a celebration that involves an entire community shedding inhibitions and coming together in a space for joy and merriment. Once relegated only to small towns and villages, the mela is making its way into the heart of Pakistani retail.

You see, during the pandemic there was a massive change in how we shop. Lockdowns and social distancing meant that retail stores

suddenly found themselves down for the count and e-commerce got a massive opportunity. This led to the emergence of an extensive online retail ecosystem.

And now that the pandemic is over, many of these online retailers that made it during lockdowns now seek the advantages of physical space. Perhaps nothing has best characterised this than the growing trend of pop-up bazars.

These are small festivals where retailers can sign up for two or three day events and display their work. People from around the city can join these pop-up bazars to look at these products they would otherwise only find online and buy them in-person. Along with this, the pop-up bazars organise food and entertainment to make it a well-rounded experience. While events like Haryali in Lahore or the Creative Karachi Festival are far from the Bakhtinian Carnival, they do still rely on the

essential elements of the mela.

At this point, farmers’ markets, retail pop-ups, and shopping festivals are as ubiquitous as the latest viral TikTok dance craze. So what transpires when you amalgamate the realm of retail shopping with the exuberant spirit of a mela and present it to a new demographic possessing the purchasing power to indulge at an elegant bazaar?

So do take a comfortable seat - ergonomically designed, of course - and allow Profit to illuminate the potential of pop-up bazaars and how they have taken Pakistan’s retail scene by storm.

If you’re from Karachi, you’ve definitely heard of The French Festival at Alliance Francaise, Karachi Eat, or the Creative Karachi Festival. Makers’ markets and

A strong retail community has emerged in Pakistan over the last few years, providing a physical presence to online brandsRizvi,

carnivals have always been around, but they’re growing and getting more popular than ever.

Profit spoke with Sitwat Rizvi, founder of The Commons Karachi, to find out how she got the idea to bring the mela to an upper-middle-income demographic. “Lots of people have been hosting similar events and markets, as well as panels and talks,” Rizvi said. “They’re not just shopping events, but the market aspect has always been a big part of it.”

“The Commons Karachi changed things up by altering the aesthetic and vibe and making it a pure marketplace. Karachi Eat is obviously a big player in this area, but it’s more focused on food. Our interests were slightly different, so we thought of a makers’ market.”

When asked about her vision for The Commons and why she decided to organise such an event, Rizvi revealed: “The idea came to me because I had access to a school during Covid. The Commons started as a space for community experiences where we would host brunches. My husband and I initially worked with a friend who has a food business. We pivoted because I wanted to do a makers’ market and find these small brands that I had seen online. Lots of people had started side hustles and e-commerce shops. I curated 20 of my favourite online brands and that’s how The Commons market came about.”

For Rizvi, starting The Commons wasn’t some grand plan - it was just a way to deal with feeling lonely and isolated during the pandemic. But her attempt to bring people together and find a sense of community in the midst of all the craziness led her to something way bigger than just having brunch with friends.

Hassaan Khan, head of digital strategy and content at Mashion (you’ve probably heard of them), told Profit that hosting Mashion Bazaar was totally inevitable for them. They had all the ingredients for a successful market. Khan was like “The idea has been brewing since Mashion’s inception. Our original plan was to be an e-commerce platform for smaller brands. But over time, we evolved into this super popular lifestyle platform for Paki-

stanis, creating content across fashion, beauty, food, and wellness. A huge part of what we do is promoting smaller women-owned businesses and entrepreneurs in general. And with our million-plus followers and access to experts, artists, and influencers, an event at scale was a no-brainer for us.”

And speaking of bazaars, there’s one that we often forget about: The Farmers Market.

While The Commons started as a way to cope with Covid blues and Mashion was all about using their resources, what’s the deal with Islamabad’s Farmers Market?

According to Qasim Tareen, co-founder of Islamabad Farmers Market: “I was inspired by the prairies and the person pushing a cart full of veggies and fruits through residential areas in cities. In rural areas, everyone would grow and share food with their neighbours. So I was like, why can’t we have that in the city?”

Tareen had a vision for a farmers market born out of necessity. He ran a small farm near Islamabad and craved a place to sell his organic produce, instead of wasting it for a bargain at a wholesale market. “The farmers market took off in 2013, in a humble community centre called Kuch Khaas. Their team kindly lent us that space and helped us organise a market that has blossomed tremendously over the last decade.”

“The entire population is starved of recreational avenues. People have nothing to do, and public spaces where families can have a delightful outing are limited to malls, so it was a no-brainer to realise that our middle class would love such an event,” Khan declared.

“I think it is safe to say that the idea is a smashing success if you look at the large numbers of people (approximately 10,000) that flock over two days.”

The seed for the idea of these bazaars were all sewn differently, but bloomed into markets not so different from each other. Do they have

such greatly dissimilar business models too? Well, not quite.

Khan walked Profit through the process of how they brought Mashion Bazaar to life. He said, “Mashion already works with huge multinationals on digital campaigns, but in this case, we have just taken those partnerships offline to build a unique event that caters to our target audience, benefits the vendors due to our huge digital reach and can provide our sponsors with 10x the talkability they would get on a digital campaign.”

He continued, “The business model involves generating revenue through a combination of vendor fees, sponsorships, ticket sales, and any additional revenue streams, such as merchandise sales or advertising. As of now, a significant chunk of the money goes into event set up and management, where sponsors really help. The revenue goes towards event expenses and future events.”

Rizvi detailed a similar business model, however, with much less entrepreneurial vigour and much more passion project excitement. She told Profit that, “The business model is fairly simple. Whereas previously we would reach out to businesses, now the Commons has grown so much that businesses reach out to us. We provide them with all the information regarding the space we have, the costs associated with booking a slot at our market and then we use most of the money from vendors to set up the event, which includes rental costs and set up costs for the tents and infrastructure that we have, plus the marketing and advertising. We as a company rely on ticket sales and any sponsorships we get to make our own revenue.”

She elaborated by sharing that it has always been about the experience and the community for her. “Surprisingly, even in the first marketplace, which we had only advertised on Instagram and just within our social circle, without any proper marketing or promotion, we had about 400 people show up. They loved the space and the way we had created it. More than the market itself, I believe it was the experience, which was so festive and fun, with a certain kind of aesthet-

The Commons Karachi changed things up by altering the aesthetic and vibe and making it a pure marketplace. Karachi Eat is obviously a big player in this area, but it’s more focused on food. Our interests were slightly different, so we thought of a makers’ marketSitwat founder of ‘The Commons Karachi

ic and music.”

Rizvi remembered how the vendors at the first ever Commons marketplace had amazing sales and how they still claim that the kind of money they made at that market with just 400 people was better than they had done at any other market after that.

When asked how she ensures that her vision for Commons is accurately implemented, setting them apart from other similar bazaars, Rizvi relayed that, “I think it’s a combination of the kinds of vendors you have, as well as the kinds of consumers and their spending power you’re able to attract. I would say that the idea has become wildly successful and a lot of others have tried doing what we’ve been doing. After us, there are countless examples like Mashion and Locate, who are replicating a similar concept. I would say everybody kind of brings their own flavour to it.”

“I believe the commons stands out because a lot of what we do has been done with the intention of creating and putting together a really great experience. While, the monetary aspects and the business model remain key elements, regardless, our primary focus is that the vendors and audience all leave feeling like their time and money was well-spent. That’s the core and heart of Karachi Commons because it was not about how this is easy money to make. It is not easy to pull this off at all actually.” Rizvi concluded.

So, the business model of both these shopping festivals is similar. What else is the same, other than of course, their revenue generation channels, vibrant pop-ups and star-studded guest lists?

Well, exclusivity! Both Mashion Bazaar and the Commons Karachi admit to being highly selective and strict when choosing their vendor.

Rizvi disclosed that, “Our entire company exists mainly on instagram, so when we are considering what brands we select, we make sure they have a good online presence and have been selling for a while. There are

exceptions, where we allow newer brands to participate, as well, but for the most part we want businesses that are established.”

“There’s a certain quality that we look for because our customers have certain expectations when they come to Commons and we make sure we deliver that. There is no point in me covering my profit by getting 8000 people in when only 200 of them will actually buy anything and the vendors won’t really benefit. The focus is on getting our vendors the right kind of crowd and similarly, the right vendors for the attendees. So, our PR, invitations and brand collaboration are all focused on attracting the right crowd.”

Stressing upon the strategic selection of vendors, as well as conscious marketing and branding to also attract a strategic audience, Rizvi concluded by saying that, “We tap into a certain demographic through our PR. We send PR bags to a very select few influencers, and it’s quite strategic how we do it. Instead of reaching out to someone with 200,000 followers, we will reach out to someone with 7000 followers but who has the kind of community that we want at our event. So, the right type of people is more important than just getting a huge crowd. Over time, through word of mouth and social media more and more people are aware of what the commons is and our market is growing but at the core it is still very niche, and that is the positioning that we want to continue to take forward.”

Khan enlightened us with Mashion’s selection criteria and lo and behold, it is as selective as that of Commons! However, where the focus of Commons was on quality and aesthetic, Mashion has a greater inclination towards women-led businesses and smaller newer brands that are still in their premature phases of growing but exhibit great potential.

Khan told Profit that they are proud to feature a highly curated selection of vendors, with a special focus on women-led businesses. He said, “We believe in supporting and empowering women entrepreneurs, which is why we’ve taken great care in selecting ven-

dors, who are not only exceptionally talented and creative, but who are also women-owned or operated.”

“We believe that the success of our event depends on the quality of our vendors, which is why we take a highly selective approach to vendor selection. And while brands that are well-established also take part, the majority of our vendors are up and coming direct to consumer brands.”

What would you say is the best way to promote an event that mainly brings together an online retail community in a physical space? Well, get those who rule the internet to talk about it!

And what’s the best way to make someone talk about you? Of course, send them a gift basket.

Most of the promotion for events like the Commons, Mashion Bazaar, Haryali Market and Karachi Eat happen on Instagram, through influencer marketing.

Profit invited Multimedia Journalist and Social Media Influencer Sabah Bano Malik to share how organisers approach her to attend and promote their event and why she thinks they are worth engaging in.

Malik told Profit that, “An invite will include a PR package, which has brands that will be present at the event and this works in a number of ways, 1) I get invited 2) it’s nice to get some merch and 3) when we share and tag the brands in our stories on social media, we are not just promoting the event but also the brands that will be there as well.”

“Almost always the invitation will include hashtags of brands that are in the PR box and sometimes even brands that aren’t but will be featured at the event. And the expectation is for us to tag them. It’s a crossway engagement, wherein our followers

As women in these spaces, we do tend to know one another and it’s about being supportive and wanting to get this off the ground. Many of the businesses present are also women owned or oriented. So, on one hand as an influencer they engage in that way but on the other hand it’s just women supporting women and when you get engaged you find out about these things happening through word of mouth as well

Sabah Bano Malik, multimedia journalist and influencer

will also see these brands and their instagram accounts or social media pages.”

Malik shared what spikes her interest in partaking in these events, by telling Profit how a lot of these markets, specifically Commons and the ACF fundraiser, are owned and operated by women. “As women in these spaces, we do tend to know one another and it’s about being supportive and wanting to get this off the ground. Many of the businesses present are also women owned or oriented. So, on one hand as an influencer they engage in that way but on the other hand it’s just women supporting women and when you get engaged you find out about these things happening through word of mouth as well.”

Needless to say that influencer marketing and digital promotion is a highly successful strategy, especially for events that aim to unite online communities in a physical space, in real time.

Aesthetics, recreation and revenues aside, what makes these events so important for our economy? Yes, it supports and bolsters the local small business community, especially online brands, who make great stuff but lack the privileges of having a physical store.

Profit asked some vendors, who attended the Commons Eid Milan market this year to share how they got one of the highly coveted spots at Commons, as well as their experience of participating in the event.

A spokesperson from Klimt told Profit that getting a spot at one of these bazaars can be very competitive and you need to stand out in order to get in. “The process of getting a stall can be kind of tedious. I had been trying for a while but everytime I would just miss out because it sells out very quickly. So, you have to also keep track of when what is happening and sign up immediately. My label had some recognition already, since people liked it and some celebrities have worn it, so they were interested to have a good brand come on board. I feel like if I was completely new and it was my first time it would be more difficult because they are kind of picky.”

So, we get that bagging a spot at the Commons is not easy but then again, good things never come easy.

You might have attended the Commons before Eid, or strolled through the carefully curated stalls at Haryali market and had great fun, but you probably did not realise the utility of these bazaars goes way beyond you having a good time.

According to Aisha Latif, creative director at Inclusivitee, these markets are very

beneficial and extremely important for the online retail community. “The first commons I attended was phenomenal. I was at a point in the business where I had only started a few months ago and I wasn’t sure if it was something I wanted to pursue. What the Commons did for me, specifically, was to give me a proof of concept in real time, so I got to meet people, hear their opinions, see their reaction to my product, which is hard to do if you are an online brand.”

Latif says that it was very helpful for her as a business owner, but the impact of it for the brand was also tremendous. It gave her the chance to interact with people in a way that she did not have access to as an e-commerce business.

Our source at Klimt had a similar response. They said, “The markets really help in terms of reach. We definitely had some celebrities who dropped by, I’m pretty sure a few influencers also came in and bought some stuff. I got the recognition that I’d been lacking for the work I have been putting in for the last few years. In terms of foot traffic and exposure it was very very good, we made a lot of new customers and I’d definitely go for it again.”

Apart from attracting the right crowd and making good sales, there is a greater function that these markets serve for business owners. Oftentimes when we buy things online, we forget that these stores are run by people, who have a vision and a mission.

But when we interact with the business owners and their products in real-time, it’s a more meaningful two-way exchange that helps us humanise the business owners. It’s easy to complain about price tags when you can detach yourself from the creative process and the time and energy it takes to materialise it. Pop-ups and maker’s markets help small online businesses combat this issue.

“The number one issue with being an online store is that digital marketing is extremely saturated and expensive. There is an art to it because you are trying to figure out what your niche is and where you can find our customer through specific targeted ads, so that’s a very challenging part. It is hard to tell your story through these digital channels or create a personality for your brand and what these bazaars help with and get the feedback that’s necessary to grow your business.” Latif shared.

Latif continued to list other benefits of attending the Commons, “The sales you would make in 3 weeks can be made in 1 weekend. Apart from sales, it also creates a nice momentum for the next few weeks after the event because there’s usually a lot of inquiries in the weeks following and you get a lot more exposure, as well.”

Klimt resonates with this idea, sharing

that, “Commons was really good for us financially. We were one of the few stalls that were very busy. It was difficult to manage all the foot traffic because I never want it to be a quick transaction thing, I like to talk to people and tell them why I’m doing what I’m doing. I went to Commons with very shallow expectations but it turned out to be great. We were able to recoup the money that we invested in the stall and we got some good customers who would keep returning. Plus it helped us build a better network, which will eventually help us scale up the business.”

Malik also pointed out a few ways in which she believes these bazaars are transforming Pakistan’s retail scene and providing an excellent avenue for empowering women, allowing businesses to collaborate and creating a safe space for people to have fun, without getting harassed.

“It means that I get to, for the first time in many cases, touch the products and interact with the products that I primarily see online. Majority of these brands tend to be on Instagram or online stores because the expenses of having a brick and mortar store are insane. Many times there is a no return policy for things you get from an online store, so you can either exchange or you are stuck. I think it’s a great way they have dealt with that.”

The advantages of shopping festivals are far-reaching, paving the way for creative marketing strategies and exciting collaborations that you don’t see often. “It is also great how everyone comes to work together. So, you’ll see candle companies and clothing companies and makeup companies and jewellery companies cross-branding and working together, working on each other’s products and doing limited collections together. That’s really really cool to see. And in general it’s fun to have an experience where you can check out so many places in one go and it becomes kind of a social thing.” said Malik.

Malik elaborated on the utility and potential of marker’s bazaars by sharing that, “The safe space thing is pretty incredible, you get to go and shop. I’ve been to Commons twice and Winterfest in Islamabad thrice and in my experience so far,no one’s leering at you, gawking at you or following you around. You feel safe and you get to shop and feel normal for a day.”

So, not only do these markets help us come together and have a good time, with delicious food, tasteful music and immaculate vibes, but also helps boost the economy in unprecedented ways. It gives online brands the chance to interact with their customers and tell their story, while gaining greater traction. Meanwhile, the customers who are wary of buying things online, can shop from online brands in person, while enjoying a safe and carefree shopping experience. n

There are more than 34 million children in Pakistan who can be deemed as malnourished, or 33 percent of the country’s population of children, more than 44 percent of whom are less than five years old and are stunted, and 15 percent of the same are wasted – suggesting that roughly 12 million children are stunted. The decently conducted population census suggests a population growth rate of 2.48 percent, which is amongst the highest globally. As the population continues to grow at a rapid pace, the state continues to fail in enabling access to basic nutrition to its most vulnerable population segment. Even education takes a backseat at this stage, when access to affordable nutrition is not guaranteed, or not made available.

A country can never achieve sustainable economic growth, if it cannot feed large swathes of its population. A demographic dividend, which is a function of the country’s youth bulge is rapidly turning into a demographic liability, as the state has failed to address critical areas of malnutrition and stunting. Economic growth is a function of labor, capital, and productivity. An economy like Pakistan can capitalize on its population base to enable broad-based economic growth. However, if the same population base is not trained, or educated, it cannot effectively contribute, or benefit from that broad-based growth.

More importantly, if a significant portion of that population is malnourished, or stunted, it cannot even be educated, or trained, such that any long term gains productivity can be realized through education, or human capital development. Simply put, the physiological need of hunger needs to be addressed first for survival, before education can be imparted.

Food inflation in the country has exceeded 50 percent on a year-on-year basis, making access to nutrition more difficult. Millions of children are already out of school, and more are expected

to leave school, as budget constraints can either allow for access to nutrition, or education. Even when food is available, it may not be dense in nutrition required for the development of children.

According to the School Age Children, Health and Nutrition Survey (SCANS), 2030, more than 90 percent of children have inadequate quantity of iron in their diet, with iron deficiency being among the most critical reasons for malnourishment for children aged less than five years.

Similarly, more than 80 percent of children do not have sufficient intake of calcium, zinc, and Vitamin A relative to recommended intakes, in their diets. In the case of macronutrients, almost two-thirds of children have inadequate protein intake, relative to the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

Given a rapid increase in food prices, particularly protein, the macronutrient, and micronutrient intake will decrease, further affecting millions of children across the country, further increasing the incidence of malnutrition, and stunting in the country. Absence of a coherent agricultural policy that prioritizes access to nutrition, and optimized macronutrient, and micronutrient intake is pushing the country towards a demographic disaster. Recovery from such a disaster would be extremely difficult, or impossible if we subject a full generation of children to malnutrition.

Malnutrition has direct medical, and indirect economic costs. Direct medical costs include greater hospitalization, and greater stress on an already fragile healthcare system. Having the right interventions in place can relieve the burden on the healthcare system. Indirect economic costs include restricted physical and cognitive development of children, which hinders their ability to acquire education, while restricting them from acquiring more advanced education at the same time thereby hindering productivity gains, not just at individual, or household level, but also on a macro level.

Pakistan is going through a polycrisis right now, from political, to economic, to energy, and so on. All of these can be fixed with the right interventions, and fixed in a relatively short period of time. A demographic crisis is an existential crisis. It is a crisis that pushes millions of children towards a darker future, if the right interventions are not made today. This is a crisis that can pose an existential threat to the country.

A coherent national nutrition policy needs to be in place, that enables access to affordable nutrition, whether that be animal protein, vegetables, or other grains, etc. – in a manner that makes access affordable, rather than being subject to price volatility. Fixing agricultural supply chains and incentives is crucial in enabling the same.

On a more accelerated level, it is critical that food is fortified for early childhood intake, such that nutritional quality of available food can be improved, and micronutrient deficiencies can be addressed. These are minor, low-hanging, and low-cost interventions that can generate high value outcomes. The state has continued to fail in successive generations. As the population increases, so does the scale of that failure. It is extremely important that the state starts caring about nutrition and its effect on future generations, else we will have successive lost generations, with only ourselves to blame. n

By this time, you must have heard chatter about Pakistan drawing closer to default. Whether it’s a newspaper analyst, your “knowit-all” uncle or a work colleague, Pakistan’s imminent default is undergirding the conversation these days.

This conversation was triggered by the arrest of former Prime Minister Imran Khan on May 9, which sparked political unrest across the country. The persisting political instability poses obstacles for the ongoing International Monetary Fund (IMF) deal, and chances are that it might get delayed further.

In 2019, Pakistan had signed a $6.5 billion bailout package with the IMF, the

Extended Fund Facility (EFF). When Imran Khan became the Prime Minister of Pakistan in 2018, he initially sought friendly loans from China, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to prevent tough IMF conditions. However, when the economic situation worsened in 2019, his government reached out to the IMF. The loan was negotiated on IMF conditions which involved hike in energy tariffs, removal of energy subsidies and increase in taxation. The PTI government had difficulty fulfilling commitments made to the Fund. Soon after the party’ popularity took a hit due to the deteriorating economic conditions, the IMF became secondary to political capital. When it became clear that the government was going to be removed, a Rs 10 fuel subsidy, in direct contradiction

to one of the IMF’s fundamental conditions, was announced. It was perhaps the last major decision the PTI federal government took before Imran Khan was removed from office in April 2022.

With the new Shehbaz Sharif government in place, Finance Minister Miftah Isamil was able to secure a $1.1 billion tranche from the IMF in August of 2022, in addition to increasing the EFF size to $6.5 billion from $6 billion. This was the last tranche the Fund released to Pakistan.

After continuous delays and setbacks, including the replacement of Miftah with Ishar Darm an agreement was reached in February 2023 as part of which the IMF agreed to release another tranche of $1.1 bn to prevent Pakistan from default, given that Pa-

kistan would abide by IMF conditions. Those conditions have so far not been met.

In the context of political turmoil, “it looks increasingly difficult for Pakistan to avoid a default in the absence of fresh funding support coming in,” said Eng Tat Low, an emerging-market sovereign analyst at Columbia Threadneedle Investments in Singapore.

“I am also growing more skeptical whether an IMF deal is going to come through. Their heavy debt amortisation against precarious reserves would suggest default is imminent,” he informed The Business Standard.

According to Columbia Threadneedle, external debt service is estimated at about $22 bn. Furthermore, dollar bonds due to mature in 2031 declined to the lowest since November on May 17,

Given the crisis, it’ll be worthwhile to revisit the developments related to the IMF bailout package, negotiations for which have been ongoing since February. Profit traces a timeline of these events.

In early February 2023, after much deliberation Pakistan reached an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to restart the stalled EFF. The agreement entailed conditions as part of which the IMF would release about $1.1 billion in financial aid to Pakistan- critical aid to prevent Pakistan from economic collapse.

In 2019, Pakistan had signed a $6 bn bailout package with the IMF, with an additional $1 bn added to the programme later that year. However, the first payment of $1.1 bn had been stalled since December as Pakistan struggled to meet targets set by the lender .

In August 2022, the IMF board approved the seventh and eighth reviews of Pakistan’s bailout programme, which would release $1.17bn in funds to the cash-strapped economy. Miftah Ismail, the finance minister at the time, played a key role in the negotiations.

The new agreement followed months of deeply unpopular belt-tightening by the government of Shehbaz Sharif, who took power in

April 2022 and eliminated fuel subsidies and introduced new measures to widen the tax base. According to Ismail, the government’s “corrective” measures had saved Pakistan from default.

However, Ismail handed in his resignation in September 2022. His departure came after months of speculation that Nawaz Sharif (PML-N leader) and Ishaq Dar (leading PML-N politician) had been unhappy with some of his salient decisions, especially the fuel price hike.

Mr Ismail said, “My job was to save Pakistan from default and I did that. With the floods, the situation has become more challenging but I have faith that we will not be abandoned by the international financial community. I hope the gains made and the fiscal space created will be retained in the long run.”

After assuming power, Dar, the new Finance Minister said, “we will try to make sure that Pakistan completes its second IMF programme in its history.”

He assured that the government would implement fiscal measures demanded by the IMF, including raising Rs. 170bn ($627m) through taxation. Additionally, commitments to increase fuel taxes would be completed with diesel levies to be doubled to Rs5 per litre on March 1 and again on April 1 in 2023.

Other measures demanded by the IMF included reversing subsidies in the power, export and farming sectors, and raising the key policy rate.

By February 16, the government of Pakistan had tabled a Rs 170bn ($643m) finance bill to help the cash-strapped economy secure funds from the IMF and avoid default. These measures included increasing the general sales tax by 18% and following hikes in the price of fuel and gas earlier that week to meet the IMF conditions of the release of $1.1bn loan, originally due in November 2022.

The bill’s approval was expected to unlock IMF’s $1.1 bn installment and provide and encourage Pakistan’s allies to provide it with the much-needed external financing. The delay in securing approval had wreaked havoc on the

economy however.

Pakistan continued to battle an economic meltdown, aggravated by a balance of payment crisis, record inflation and currency devaluation. Inflation skyrocketed to 27.5%, the country’s highest in nearly 50 years.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif lamented that the economic situation had become “unbearable.”

The crisis was compounded by catastrophic floods in 2022 (June-October), which had caused damage worth $3obn and raised concerns about food security. The ensuing political chaos added more fuel to the fire.

Consequently, Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves declined to $2.9bn during the week ending February 3. Experts stirred alarm that reserves would last less than 20 days and a delay in an IMF payout could have dire repercussions.

Economist Haris Gazdar informed Al Jazeera that “political commitment” was necessary for the IMF to confer its advantage upon the government of Pakistan.

“IMF conditions are not unfamiliar to Pakistan, which has entered into more than 20 such programmes with the global lender since 1958,” said Gazdar.

“What they (IMF) have asked of us include revenue collection, non-interference with exchange rate etc. Since the relationship between these variables and actual economic outcomes is never precise, there is room for genuine disagreement on targets that must be met,” he added. “So, negotiation is part of the deal. But how much space Pakistan gets in the end is partly political.”

Sajid Amin Javed, a senior economist associated with the Sustainable Development Policy Institute in Islamabad further reinstated this, “the overarching problem behind the failure to prevent the IMF programme sooner was the lack of political stability in the country.”

The political instability followed the Prime Minister Imran Khan’s removal through a parliamentary vote of no confidence in April 2022.

Pakistan has to pay $3.7bn in amortisation debt repayment and $400 million in interest payments within the next two months. So by October 1, we’d probably have less than $2bn. How long we can survive after that, only Allah knows. Things will get very difficult for Pakistan in the time being

Miftah Ismail - Former Federal Finance MinisterDr Hafeez A Pasha - Economist

On March 9, Dar announced that Pakistan was “very close” to signing a staff level agreement with the IMF. This could offer a critical lifeline in tackling the balance of payment crisis.

The Pakistani government began formal negotiations with the IMF on February 1, 2023, to discuss a plan to rescue the economy. They sought to negotiate funds which were part of a $6.5 billion bailout package that the IMF had approved in 2019.

The IMF deal would pave the way for other critical bilateral and multilateral financing avenues for Pakistan.

According to a report from Reuters, Islamabad had met most of the lender’s demands to clear the review. The last one left to be fulfilled involved an assurance on external finance to fund Pakistan’s balance of payment gap for the present fiscal year, which ends on June 30.

Only China had announced the refinancing of a $2 bn loan, and Pakistan’s central bank had already received $1.2 bn of that demand.

On March 24, it was announced that the agreement will be signed after the completion of a few remaining conditions, which included a fuel pricing scheme.

This time, the latest issue was a plan announced by the Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to charge affluent consumers more for fuel. The money raised would subsidise prices for the poor, who had been deeply affected by inflation. The plan involved a difference of around Rs100 a litre between the prices paid by the rich and poor, according to the petroleum ministry.

The IMF demanded an explanation for this. Esther Perez Ruiz, IMF’s representative resident in Pakistan said that the government had not consulted the fund about the scheme.