08

08 The Walled City Exodus

12 Has the 'Peoples' Bus Service fallen prey to the people's representatives?

18

18 Crop talk: China wants our Cherries. But will Pakistan rise to the occasion?

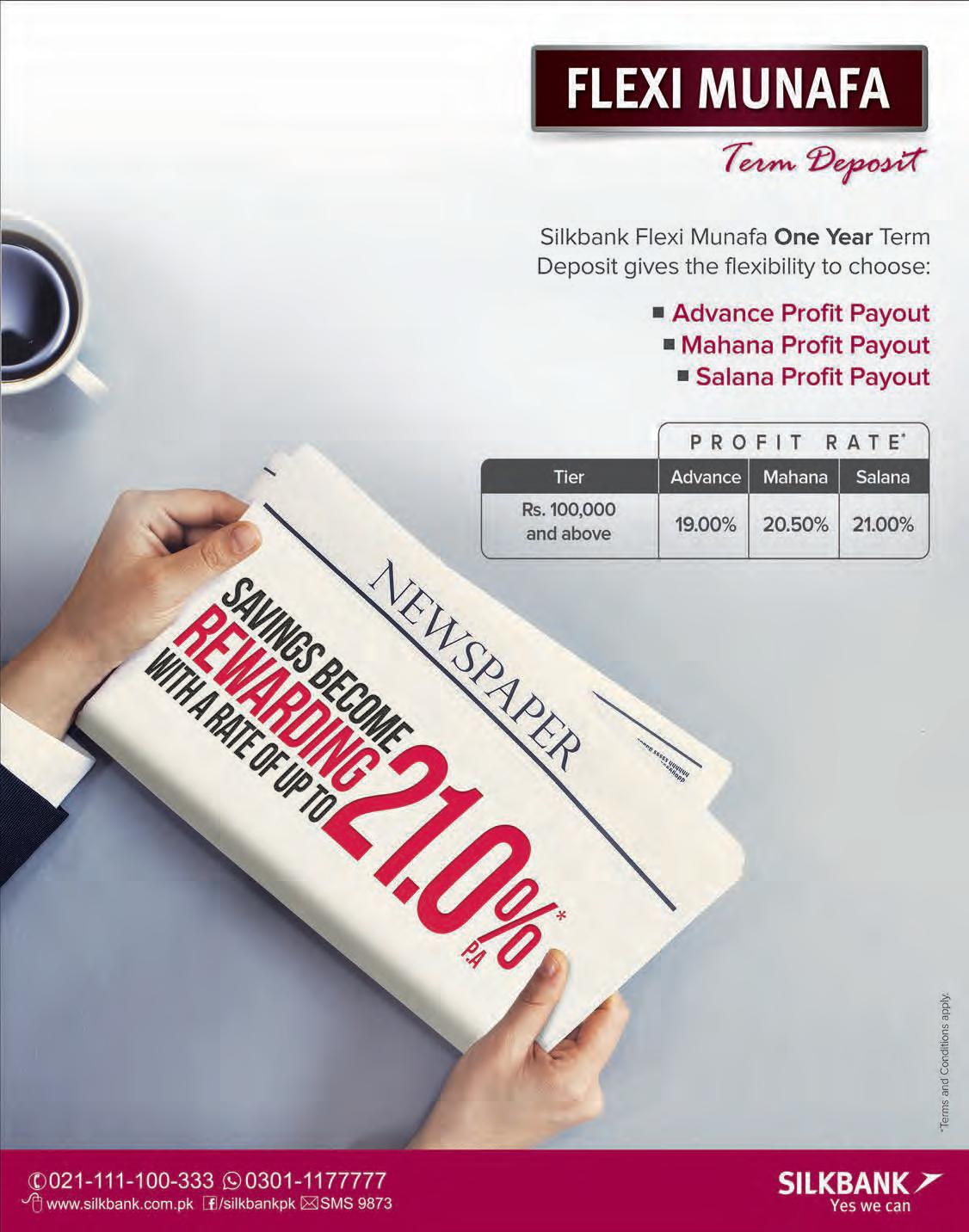

21 Price Fixing Ammar Habib

22

22 Pakistan’s cellphone industry: A prospective $15 billion exporter or another automotive-style catastrophe

28 The gloomy fate of our State Owned Enterprises

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Cramped real estate is lying wasted in the Walled City of Lahore that no one wants to take. Why is this so?

The drawing room is lavish if not tasteful. “Be careful walking through here, it’s a little slippery,” says our host pointing towards the glistening black and silver tiles beneath our feet. “They told us it’s Italian marble, it’s the best in the world, but honestly I’ve never quite felt safe walking on it.” Middle-aged, genial, and fussy Mrs Shah* leads us to a drawing room the size of which elicits a cartoonish double-take.

What it lacks in taste it makes up for in lavishness.

{The name of the interviewee has been changed on request to maintain anonymity.}

In the background, the slight buzz of the central air-conditioning confirms why the room is so crisply cool in April. “Sorry about the noise, the air conditioning has been bothering us this year. Of course, back in the old house we never really needed air-conditioning. I still remember spending summers there as a kid and all us cousins would put our charpais in the courtyard and sleep all day. That’s what you’re here to talk about, right? The Mochi Gate house?”

That is indeed. A few years ago, Mrs Shah was the last hold out on selling a 1-kanal property in the middle of Lahore’s Walled City deep inside the Mochi Gate. For context, a kanal inside the walled city is a massive place — a grand old haveli really. “Property prices here are nothing like you would expect. Most people think they cost less here as compared to places like DHA or Bahria Town. However, I have seen one marla house sell here for Rs 50 lakh recently,” says one property dealer that works in the Walled City. “The problem is that there aren’t a lot of buyers and the rates are very high. A lot of families have moved out of here but it will take years before all the shareholders in a single property agree to sell it and more years before the place actually sells.”

The Walled City of Lahore is in a strange world of its own when it comes to the real estate market. Prices are high but demand is very low. Despite this, the past few decades have seen almost a complete exodus of wealthy families that used to live and conduct their business in the Walled City. And it isn’t just this area. Once considered central locations, places like Ichra, Mall Road, Krishannagar and even areas such as Shah Jamal and Shadman have become undesirable, with wealthier families regularly selling their old family homes here and shifting to places like Defence and Bahria Town and less wealthy ones moving to places like

Johar Town.

Sitting alone in the center of her drawing room, Mrs Shah looks withdrawn. She has not lived in the old family house at Mochi Gate for over 40 years now, but until a few years ago it was still in the family. That was until her father passed away. A wealthy man, he left behind a bustling business with over 2000 employees that is a household name in Pakistan. “All my siblings wanted to sell the house. No one was living there anymore in any case. The only problem was that I didn’t want to sell,” she explains to us. “My father didn’t come from much. I remember him telling us how our grandfather had a soap shop in Mochi Gate, and that he took a loan from his brother-in-law to open it. The day after he opened it, the monsoon rains kicked off and all the soap in his store was washed away into the streets.”

There is a quiver in her voice. Mrs Shah never knew her grandfather, but she tells us how her own father would tear-up every time he mentioned this story. “He loved that house. He loved that area. Even towards the end when he was very old and sick, if anyone visited from Mochi to come see him he would find the strength to talk to them.”

“Why did we move? Oh well it was also a horrible place to live in,” she says when asked. The family started moving away from Mochi as early as 1985, and by 1995 everyone had settled in either Defence, Model Town, or Garden Town. “There were no facilities there and everyone that lived there slowly moved away. Businesses still remain there. My family still owns many shops and a couple of plazas in that area but we don’t live there anymore. All the good schools and places to go out are far away from the old city and everyone has shifted from there.”

That is a problem. Once upon a time, the Walled City was home to many of Lahore’s ashrafiya. So long as they lived here, they advocated for the upkeep and maintenance of the area and kept it a living, breathing, residential area. “The only people that live here now are the ones that have no option but to live here. They have no other option,” explains another property dealer. Because of this, the Walled City has become a strange slush of economic necessity, glowups done by the Walled City Authority of Lahore and absolute desolation.

This is the problem we find ourselves with. Property prices in the walled city average at around Rs 20 lakh per marla in some areas, rivaling very posh locations. However, there is no

distinction between commercial and residential real estate and the land deeds in this region are confusing and messy. Ownership documents are sometimes from colonial times. And most importantly, the place is uninhabitable.

“A lot can be learned from the history of this area. The commercialisation of the area began when the railway station was built adjacent to the Delhi Gate. The station was built during the colonial era in 1860, at the intersection of Empress Road, Allama Iqbal Road and Circular Road. Later, a bus station opposite the railway station was opened and made operational. As a result of these infrastructural developments, the eastern side of the Walled City saw the rise of commercial activities. Overnight, bazaars started emerging and spread like wildfire throughout the inner city. Another key point of commercialisation was the Shah Alam Muhalla, and therein, bazaars began penetrating inwards,” explains a senior director at the Walled City Authority.

This fascinating history elucidates that transportation has been indispensable to the area’s commercialisation. With the construction of the railway station and bus adda, the Walled City became the jugular vein, regulating the flow of traffic in various directions. These conditions made the space ripe for commercial activities.

This brings us to a key question: How did commercialisation affect local residents?

“In the Walled City, the average size of a house is between 3-5 marlas. You have small houses, clustered in narrow alleys. When commercial activity developed along the streets, these houses skyrocketed in value,” our source from the WCLA says.

As scope of business increased, the population census depicted that the old city’s population decreased, and this trend is still prevalent. Due to commercialisation, the land prices have become exorbitant.

“People are able to sell their 2-3 marla house, and buy a bigger house in a modern housing society at essentially the same price. People are actually eager to sell their cramped makaans and shift to more spacious houses.”

Whereas population increase at a given area is typically perceived as a problem, the situation is inverted here.

“Here, the residential population has been steadily decreasing which is a problem faced by the local inhabitants. As the residents leave for greener pastures in the modern areas of Lahore, outsiders start filling their space. For example, recent years have seen an influx of Pashtun migrants in the area. Now, they don’t share a relationship with the local abaadi. This ends up affecting the entire social fabric.”

“There are many dimensions to how the Walled City’s profile is changing. How the city’s residential areas are changing their character mirrors, the changing psychographics. People coming from different backgrounds set different cultural parameters once they settle here. This is often difficult for the locals to adjust to,” added Nadhra Shahbaz, Professor of History at LUMS.

The local abaadi is mainly concentrated around the Taxali Gate area and Bhaati gate areas. Akbari Mandi, Shia Muhalla and Mochi Darwaza also house considerable local abaadi.

While the area is coveted as a tourist destination, the actual living conditions are extremely difficult. Mobility is restricted as cars can’t pass through narrow streets, making the Walled City only suitable for bikers and pedestrians.

“Moreover, basic amenities such as health hygiene and clean drinking water aren’t available. Facilities for modern living are simply not accessible in the inner Walled City. Coupled with traffic congestion, most residents dream of relocating to modern areas of the city that are equipped with such amenities,” our source detailed.

There is no hard data regarding the ownership and migration patterns from the walled city of Lahore to newer residential areas. What is clear from anecdotal and testimonial evidence however is that people want to move away from the area. The problem is in finding a fine balance between making the area liveable and also protecting its cultural heritage. For that, the government would need to figure out a plan to rehabilitate the area and renovate it in large chunks either without displacing local populations or after providing them with fair compensation.

The WCLA is taking steps to protect the cultural heritage. For example, “high architecture merit buildings” are marked out. Construction on them or in their vicinity is banned. Furthermore, they can’t be sold, demolished or used for commercial purposes.

Nevertheless, commercialisation has incurred a deep impact on the local infrastructure and heritage. According to Nadhra Shahbaz, a History Professor at LUMS, “there is a continuous movement of people between developed parts to lesser developed parts in a place. Migrations are forever. People are not stationary.”

Shahbaz said that in Lahore’s case, the shape of the city is still changing based on colonial patterns. The presence of utilities such as water and electricity, along with the emergence of new societies have been governing the movements of people within the city. “People put up with this unless they have a choice to move out, and this is predominantly based on financial conditions,” indicated Shahbaz. n

“Why did we move?

Oh well it was also a horrible place to live in. There were no facilities there and everyone that lived there slowly moved away”

Mrs Shah, former Walled City resident

There are many dimensions to how the Walled City’s profile is changing. How the city’s residential areas are changing their character mirrors, the changing psychographics. People coming from different backgrounds set different cultural parameters once they settle here. This is often difficult for the locals to adjust to

Nadhra Shahbaz, Professor of History at LUMS

The airconditioning was off and even by Karachi standards it was a particularly hot February afternoon. At the office of the CEO of the Sindh Mass Transit Authority (SMTA), tempers were flaring up. Brows were furrowed, thinly veiled insults were being traded, and beads of sweat were likely running down the back of the many necks in the room.

On one side sat Sohaib Shafique, GMSouth of the National Radio Transmission Company (NRTC) and on the other side was Zubair Chann, the CEO of the Sindh Mass Transit Authority (SMTA). As tensions rose, so did the voices until Chann and Shafique found themselves in a full-blown shouting match. Others present in the room had to intervene and stop the altercation from getting physical.

But wait a second. What would propel the CEO of a provincial mass transit authority to almost come to blows with the chairman of a federally owned company responsible for the manufacturing of telecommunication equipment in Pakistan?

The answer: Over 250 buses in Karachi that have the potential to help solve the massive public transport problems that exist in the city of more than 15 million people.

Launched by the PPP government in June 2022, the People’s Bus Service in Karachi and Larkana was supposed to operate just over 250 buses. It was a pretty simple matter. The Sindh Government would set aside a budget for the project and the SMTA would then procure buses, plan routes, figure out pricing and revenue collection, hire staff, and launch the project. Instead, the project was sub-let to the NRTC — a company that has no competence or relevance to public transportation.

That’s right, a federally owned company that produces telecommunication and electrical equipment has been awarded a contract for the running of a provincial bus service. So what is going on? Some have pointed towards the preferences of certain cabinet members for officials in the NRTC. But the web behind these buses is complicated and intertwined. To understand it, we need to go to the beginning.

Let’s take a step back. In June 2022, Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari inaugurated the intra-district Peoples Bus Service project for Karachi. Under the project, around 240 air-conditioned buses imported from China will be plied on seven routes in the me-

Perhaps one of Karachi’s greatest woes has been the alarming state of its public transport system. For a city of over 15 million people (already a vastly underreported number) public transport in Pakistan’s largest metropolis is rickety and riddled with problems at best and non-existent at worst. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of buses in the city went down from 22,000 to 13,000. However, various sources including the Karachi Transport Ittehad (KTI) claim the number has fallen below 5000. Reliance has grown heavily on cars and motorcycles, with traffic congestion contributing to increased air and noise pollution, leading to health problems, high accident rates, and environmental degradation. The impact that good public transport can have on the living standards of any population is staggering. Just think of it this way: one of the biggest factors in people choosing their place of employment is how long the commute is. This then leads to other decisions such as where a person decides to live, and where they send their children to school. As a result, transport woes have a direct and often visceral impact on quality of life, and it is usually marginalised groups like women and the disabled that are most acutely affected by these problems. So what is the solution to Karachi’s urban transport mess? Ideally, large cities should be interconnected by a system of underground, on-road, and overhead trains and buses that run around the clock. In Karachi’s case, the first baby-step would be putting more buses on the road.

tropolis. The longest route on the bus would cost Rs 50.

The buses were to run on seven routes. Route 1 commenced its operations in June running from Model Colony to Tower, covering 29.5 kilometres and having 38 stations. The other six routes include the areas from North Karachi to Indus Hospital (Korangi) 32.9km; Nagan Chowrangi to Singer Chowrangi (Korangi Industrial Area) 33km; North Karachi to Dockyard 30.4km; Surjani Town to PAF Masroor 28.2km; Gulshan-i-Bihar (Orangi Town) to Singer Chowrangi 29km and Mosamiyat to Baldia Town 28.9km.

Alongside Bilawal Bhutto during this inauguration was Sharjeel Memon, the information minister in Sindh who has been the focal person for the People’s Bus Project.

To manage this project, the provincial government had established the Sindh Mass Transit Authority (SMTA) solely focused upon providing safe, efficient, and comfortable urban transportation systems in the major cities of Sindh. This in itself is a good step for the beleaguered citizens of Sindh ravaged by high inflation, sky rocketing fuel prices and endemic corruption in the province. But the involvement of the SMTA in the project seems to have been diluted, and strangely enough it is the National Radio and Transmission Company (NRTC) that is at the forefront of the project.

You see, in the first phase of the People’s Bus Service the SMTA was to operate 250 city buses and had to import 250 Buses for this purpose. Of these, there would be 150 low entry diesel-hybrid city buses of 12m in length and

100 low entry diesel-hybrid city buses of 8.5m in length for Karachi and Larkana. Sources close to the transport department informed Profit that an initial bidding process had taken place for the award of the Red Line (for which the above mentioned routes have been designated) but was then cancelled without any explanation to any of the participants. The contract was then unilaterally awarded to the NRTC.

That is the four billion rupee question. The NRTC is a high tech industry engaged in manufacturing of telecommunication equipment in Pakistan. The NRTC is an organisation of the Ministry of Defence Production (MoDP) is the sole National Electronic Industry engaged in design and development of cutting edge technologies in fields such as Robotics, Public Safety Network Communication, Power, Surveillance, Number Plates, Ground Surveillance Radars, and Cyber Security.

Questions were immediately raised about whether the awarding of the contract to the NRTC was against the rules of the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA) which disallows any government tender to be given to a department that does not have the expertise in the relevant field. “By doing this SMTA is clearly violating PPRA rules by outsourcing ‘maintenance of Sindh Intra district peoples bus service’ project to non-transport, in this case NRTC,” said one source close to

the story.

So why would the SMTA do this? The transit authority has maintained a tacit silence on the issue and has not responded to Profit’s many queries. However, sources close to the issue have said on condition of anonymity that the NRTC’s involvement was politically motivated and the SMTA had no other option but to comply with the wishes of senior ministers in the government.

Meanwhile, in different meetings, the high ups of the Transport & Mass Transit Department and GM-South of NRTC in their in-house discussion claimed that NRTC is a sovereign body and the Sindh Government has a mandate to award contracts on Government-to-Government basis to NRTC.

MD SMTA Kamal Dayo did not respond to queries. Other senior officials continued to hesitate in speaking up and shifted the blame around before expressing no knowledge of the issue. On the other hand, GM South NRTC Sohaib Soddiqui told Profit that this was a misrepresentation of facts. “There is no PPRA rules violation and the department did not also sub-let the projects. SMTA and NRTC are government of Pakistan departments and this is a successful project,” he said.

Upon being pressed, the GM did not provide any explanation for his statement and did not answer the question of how the NRTC could get the contract without violating PPRA rules. He was also unable to provide an answer regarding what the NRTC’s competence is to be managing this project.

Sources with the transit department have continued to say that this decision to unilaterally award the contract was opposed intensely by the SMTA brass at the time, but they were overruled in order to safeguard and perpetuate the political interests of a provincial minister. “We recorded our protest back then because we knew it would be against PPRA rules. However, nothing could be done at that point and we had to give the go-ahead,”

Statistics from an academic article titled “An empirical review of Karachi’s transportation predicaments” published in the Journal of Transport & Health in March 2019. Most people rely on private modes of transport in Karachi with more bikes hitting the road

they said.

This is where things stand. The Sindh Government launched a mass transit project that included 250 buses on seven routes as well as an additional ‘white line’ bus service for which they imported electric buses. Separately from this, they also launched a ‘pink’ bus service meant for women passengers. But for some reason, the National Radio Transmission Company was given the tender to import these buses and manage them. And that isn’t where this strange mixing of jurisdictional lines and awarding of contracts end.

Initially, when the NRTC was vying for the contract the mass transit department and

The outlay of the purchase of buses is $38 million, which is a huge amount of foreign currency for a cash strapped country like Pakistan. Approximately 150 buses have been imported at a cost of Rs 8.0 billion ($23 million equivalent) and handed over to NRTC. Again, the purchase of these buses was in a very opaque manner with only one supplier, Higer of China qualifying, and buses being provided at an approximately 20% higher rate than comparable, sources disclosed.Why other suppliers were not evaluated or looked at especially in the presence of local manufacturers who could import CKD kits, manufacture here and provide the same quality buses at a lower cost is a question that needs to be answered. Insiders say that the specifications and requirements were documented in such a manner that only Higer could have qualified. Again, this is a huge loss to the Exchequer and the people of Sindh because due process and transparency was fell by the wayside.

other stakeholders were told that they had a Turkish partner who would assist them with the technical know-how. This allayed some concerns but as soon as the NRTC was awarded the contract the partner disappeared from conversations and was nowhere to be found.

Since the NRTC is not a transport company, they really had no idea how to manage this project. They further sub-leased the route to the present network operators like GRC (Pvt.) Ltd, Al-Shayma Services, Faisal Movers, KTN etc. all of whom are non-standardized transporters as per international norms and standard operating procedures.

To just illustrate just one aspect of the unprofessional & non-technical nature of the way the NRTC bus routes are operated in Karachi, it has been learnt that NRTC was unable to conduct its own independent proper technical study by experts in the mass-transit field. Rather it is relying only on the study done by the Sindh Government.

The present sub-contractors are providing a below par service on the new buses and hence the service is missing the four key elements of a scheduled bus service — timings, route, stops and fare are still not in place and are variable. In addition, there is no Information Technology based ticketing or monitoring system.

Because these companies are subcontracted to run the service, many old habits such as lingering of busses on route to pick up paying passengers at non-designated stops coupled with a structural misunderstanding of how a bus service should be run have contributed to the fact that the Peoples Bus Service is being run in the same way as previous such bus schemes.

This means that the bus service has essentially been subcontracted three times and is four times removed from the Sindh Mass Transit Authority which has the jurisdiction to run the project. The SMTA sub-let it to the NRTC which has sub-let it to TIP who have in-turn sub-let it to Al-Shayma, which has in turn sublet to various local contractors, who have then sold individual routes to operators, which has badly affected the quality of the service.

And this is where we get back to the fight. The reason the SMTA’s CEO and NRTC’s chairman almost came to blows was that the project involves some serious money and revenue collection. The government of Sindh had created the SMTA particularly to manage Karachi’s abysmal public sector transport situation. However, for the management contract of such a product to be awarded to a company like the NRTC ruffled the feathers of the SMTA high-ups.

Soon after the near-brawl, Channa was transferred from his post as CEO because he continued to raise questions about how the NRTC could take over the project with no competence on the issue. Profit reached out to multiple officials of the NRTC but this correspondent was received coldly and with curt, empty answers. Profit also reached out to Sindh Information Minister Sharjeel Memon multiple times but did not receive any response despite messages having been read. Interestingly enough, Mr Memon’s display picture on Whatsapp is an image of a bus from the People’s Bus Service. Officials of the SMTA expressed their apologies and said they could not comment, but some high-ups in the authority on the condition of anonymity expressed anger towards the blatant awarding of the contract to the NRTC. “They are playing political favourites,” said one of the sources that spoke anonymously.

Some of the issues are that the NRTC has

“The sidewalk at the stop I boarded the bus at, Nursery, is dug up. The grey structure is still dishevelled. Except for the red and white painted curb, nothing about this stop says new service. The map for Route 1 identifies 38 stops along the roughly 30km corridor and Nursery is one of them. The bus, however, stops again 200m ahead, and then again, about 400m ahead, before reaching the next notified stop, FTC. From there to Tower, the bus would make far more than 38 stops, sometimes stopping in the middle of nowhere to drop off a loud passenger. In the absence of clearly notified and marked stations, each stop is a negotiation between an aggressive passenger, a clueless conductor and a pliant driver. Some of the passenger aggression stems from confusion over the route.” - From a review of the Red Line service that appeared in Dawn.

been unable to undertake the development of stops, yards, management & financial controls, or even a main centralised command and control centre for SMTA as promised. What little work has been done is on an ad hoc basis and is not up to international specifications.

One of the major disputes is on the installation of the Automatic Revenue Collection System (ARC). The ARC and associated IT systems such as ticket issuance etc. was to be installed by NRTC, but until now that has not been done. In the absence of an ARC there is no way to verify what revenue is being collected and how much is actually making it back to the Sindh Government. As per information NRTC has paid its vendor GCS (Pvt.) Ltd. in full for the system but they have been unable to deliver it to date.

In the absence of proper financial control and the reliance on human interaction for issuance and collection of tickets there is a significant leakage that is happening. That is even more surprising is that when SMTA was pushing for an internal extended audit of accounts and physical audit by third parties to verify the revenues collected and of

the numbers, NRTC flatley refused and black balled them. So again, here the people of Sindh are losing out because of belligerence of NRTC and leakage from the system.

In the same way the NRTC is refusing to account to SMTA for the ad revenue that is collected. NRTC is offering SMTA only Rs. 70,000/- per month per bus as additional revenue from advertising on the buses, while they are averaging between Rs. 400,000 – Rs. 500,000 per bus.

While, the agreement with NRTC is that NFR there will be an equal split between the two parties, which is not being followed. The second main point of contention is that fuel indexation formula. This formula was put together by qualified third parties, in this case Ernst and Young (EY) and Exponent Engineering, both of whom are of international repute. Yet, NRTC is belligerent that the formula is wrong and that it needs to be changed.

When the SMTA and its consultants have pushed back and asked for a written alternative of how NRTC wants the calculations done or its reservations, the NRTC team is unable to provide them anything in writing.

NRTC is also belligerent that the number of passengers per day provided by SMTA and consultants is wrong. The consultants had provided a number of 700 passengers per bus a day and it is NRTC’s contention that they don’t get more than 400 passengers a day. The number provided by NRTC is a wild guess at best because they have been unable to conduct their own independent survey due to their lack of knowledge about urban transport and its associated protocols.

The project itself, envisioned by a presumably more enlightened third generation leadership of the PPP under Bilawal Bhutto, to address Karachi’s perennial public transport’s nightmarish problems, has evidently come crashing down owing to the same old problems. It seems that even this solution to Karachi’s mess of a public bus service became a problem for all the bottom feeders living off it. n

country Chile.

And then there is Pakistan, which finds itself way down on the list (number 48) of cherry producing countries in the world. At just over 6000 tonnes produced a year, cherries are neither a major agricultural product for Pakistan and nor do we export any. The unfortunate part is that Pakistan very much could be. In the North, vast swathes of Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) are ideal for growing cherries. They have been grown in the region for centuries and this is in fact where most of Pakistan’s cherries come from. But that isn’t all. Balochistan over the past few years has also emerged as a great location for growing cherries.

By Abdullah Niazi

By Abdullah Niazi

In Japan, the Cherry Blossom has many purposes. It serves as a symbol for life and death, it is a cultural marker, and the annual Cherry Blossom Festival in the island nation attracts tourists from around the world every year.

Scenic views of Cherry gardens stretching as far as the eye can see with their gentle pink petals scattered all over the floor have become synonymous with the land of the rising sun. Despite this, Japan does not even crack the list of the top 25 cherry producing countries in the world. In fact, they rank number 26 on the list. Surprisingly enough, Turkey is the largest producer of cherries in the world and the biggest exporter is the South American

With all this the question arises, can Pakistan utilise its cherry potential and become an exporter? The answer is yes, and we’re already on the path to do exactly so. A report from last week revealed that following the opening of the China-Pakistan border on April 1, the Chinese government has allowed the import of cherries from Pakistan. China is actually a very large emerging market for Pakistan’s cherries. The only problem is that the Chinese have very strict regulations on the import of perishable fruits. So what can Pakistan do to encourage cherry farming and open up a rich new market for farmers?

Much like in Japan, there are Cherry Blossoms in Pakistan too. Hunza, for example, is a tourist location where you can find clusters of these trees in some locations. However, cherries are not grown in large

The demand for Pakistani cherries in China is going up despite strict regulations. The opportunity is not one to be lost

swathes across Gilgit Baltistan. Rather, most farmers have few trees and grow them within their homes or on very small tracts of land spread far apart. Because of this, there is no real cherry belt in the country even though there is a cherry growing region.

According to MNFS&R statistics and FAO Statistics, the total production of fresh cherries in 2016 in mainland Pakistan was 2,120 tonnes, with a world ranking of 47th producer. However, these figures do not include production from Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), because it is treated as a disputed area. When GB’s production of 3,898 tonnes, grown on 1,363 ha (2014) of land is included, the total cherry production of Pakistan adds up to 6,013 tonnes, and Pakistan’s ranking improves to 45th.

GB and Balochistan provinces are the main cherry growing regions in Pakistan. The largest producer is GB, with a 64.77% share in the total cherry production in 2014. The second largest producer is Balochistan with a share of 32.92%. The remaining 2.31% is produced in KPK. The total area devoted to cherries in Pakistan is about 2,512 ha. The average yield in Pakistan is calculated as 2.42 t/ha, which comes to about 45% of the global average.

The thing about fruits like the cherry is that they are high-value products that can change the lives of small farmers if grown correctly and with guidance. Cherry production in Pakistan has been expanding at a modest rate of 2.47% per annum during 2001-16, which is higher than the growth in population at 2.24%.

This implies that per capita consumption is slowly and gradually improving overtime. Most of the increase came from the expansion in area while per ha yield also improved during the period (Table 2). Because of its high commercial value, farmers

and traders are extremely careful in handling the product at every stage of the value chain. Still, postharvest losses range from 10% in the mainland to 20% in GB, without including the losses during transportation and at the wholesale and retail levels. Fruits that are damaged during harvest are separated at the time of grading, and are dried and sold, separately.

This is where the problem comes in. Pakistan has not had a bad start in cherry growing. Starting from a low base, expansion in area under cherry and its production is higher than the world average growth rates. However, Pakistan faces the same problem in this crop that it faces in so many others — average yield. Because of poor farming practices, while there are a lot of cherry trees in Pakistan, they do not grow as many cherries as the world average. This stops Pakistan from achieving its cherry export potential.

According to a 2020 report of the planning commission, almost 99% of cherries produced in the country are consumed in the domestic market. As a matter of proximity to nearest consumer markets, cherries produced in GB are supplied and sold in the markets of Islamabad and Punjab, while fresh cherries coming from Balochistan are sold in the urban centres of Sindh, such as Karachi and Hyderabad and Southern Punjab.

“Cherry production in Pakistan is far behind the world level in terms of per ha yield, export to production ratio, export and export price. For example, Pakistan gets only 40% of the world average yield, it exports a negligible quantity while globally 24% of the production

is exported, and its export earns only 56% of the average world export price, suggesting that Pakistani cherry does not compete in the international market due to its poor quality. However, the farm gate price of cherries in Pakistan is far below the international average farm gate price, which shows that Pakistan has a competitive edge over the global cherry value chain at the production level,” reads the report.

In comparison, global cherry production has increased from 2.9 million tonnes in 2001 to 3.6 million tonnes during 2017 with an average growth rate of 1.6% per annum. This growth in production is higher than the world population growth of 1.19% during the period suggesting international growth in per capita consumption, although relatively slowly. Most of the increase in cherry production came from the expansion in per ha yield at 5.5% per annum, while area growth during the period is insignificant at 0.2% per annum.

The largest volumes of cherry are traded and consumed as fresh. As reported earlier, small quantities that are bruised during harvest and separated out during grading, are dried and traded in niche markets. Cherry exports surpassed US$2.3 billion in 2017, an increase from US$383 million since 2001 with an average annual growth rate of 7.8% in its quantities and 11.7% in values. Pakistan’s main market in this would be China — where transporting cherries directly through the border would be much easier and the supply chain could be tailored for this need.

Following the opening of the China-Pakistan border on April 1, the Chinese government has allowed the import of cherries from Pakistan. But the trade requires stiff phytosanitary standards that are difficult to comply with, according to experts.

The Chinese embassy informed the Ministry of National Food security and Research through a letter that the General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China (GACC) has decided to carry out compliance inspections through remote video investigations on orchards and cold treatment facilities for the export of fresh

cherries from Pakistan to China.

Zulfiqar Monin, a leading exporter of fresh fruit, has said that the cherries produced in Pakistan, especially those from Gilgit Baltistan, are juicier than normal cherries but also highly perishable. Because of the Chinese protocols, these cherries cannot be exported to China under the existing phytosanitary measures. Under the protocol, local cherries need to be kept under one-degree temperature for over 18 days, and after that period, the health of the fruit will be checked for final export.

The only way to make the local fruits able to enter into the Chinese market is to grow imported cherry plants that may produce fruits with a shelf life of around 25 days in one degree centigrade. The existing fruits can’t survive under one degree centigrade for more than one week.

However, there is no packhouse or major cold storage to keep the cherry and treat them as per protocol in Gilgit-Baltistan. To fa-

cilitate the export to China, the existing rules need to be relaxed, and imported cherries need to be cultivated as a long-term strategy.

Cherry is a seasonal fruit with a limited lifetime grown throughout the lowlands of Gilgit Baltistan. Some of its varieties are black, red, and French cherry. It is a major source of cash for hundreds of families in the region. It has recently garnered the attention of traders in Gilgit Baltistan and has been started as a business by supplying to the rest of the country in Pakistan.

With trade permission, the local cherry industry can blossom as China is the largest consumer of cherries in the world. The Chinese and Pakistani governments have worked together since 2019 to establish an agreement on the export of fresh cherries from Pakistan to China. The export protocol includes strict conditions on quarantine pests and cold treatment facilities, which must be met by cherry orchards, packaging plants, and refrigerated warehouses. With cherries from Pakistan enjoying zero tariffs when exported to China under the China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement, the cherry industry in Pakistan has the potential to grow further.

Currently only 10% of the cherries are available for export, but there is significant potential for further export growth. With China importing more than 200,000 tons of cherries annually, the approval of Pakistani cherries to enter the Chinese market is expected to drive the development of Pakistan’s domestic cherry industry. n

be produced. Such a scenario leads to reduction in production, eventually resulting in shortages across the board. As shortages increase, an informal market develops, wherein medicines are sold at a considerable premium, or are of dubious quality, since the gray market starts actively supplying the same.

The government is obsessed with fixing prices, whether that be of the most basic staples, fuel, or medicine – it wants to meddle in the market, and thereby disrupt supply chains in the process. Thousands of years of evidence clearly demonstrates that price fixing never works, and often results in shortages, or creation of an informal market, that hurts consumer welfare.

Pharmaceutical products have complex supply chains. Most raw material is imported, and thereby remains susceptible to depreciation of the PKR. Processing is done locally, and that is susceptible to changes in overall cost of doing business, whether that be electricity prices, or inflation, etc. Product pricing is a mix of all these factors, after adding on top a ma rgin – the latter being a function of competition in the market.

Over the last two years, the PKR has depreciated by more than 70 percent, whereas compounded inflation has been in excess of 40 percent. As the cost of production increases, it makes logical sense to increase prices to at least cover for such costs. However, if the price is fixed by the government, and price reviews are done at the highest level of the government on an ad-hoc basis, then the pricing strategy completely fails. If a price remains lower, or even at cost of production and distribution, then there is no economic incentive for medicine to

It is estimated that more than 1,200 pharmaceutical products stopped production because it did not make any economic sense to continue producing products at a loss. If we look at production level data, over the last two years, production of tablets dropped by 25 percent, whereas the production of syrups dropped by 17 percent. This is in an environment where the population continues to grow, resulting in significant contraction in availability of medicine on a per capita basis. As production stopped, so did production units, resulting in loss of jobs. Due to a classic policy error of fixing prices, not only did the consumer lose out, but employment also got decimated. In simpler terms, slightly expensive medicine is better than no medicine.

An unintended consequence of fixing prices is a signal that is sent to the market that discourages investment. It makes no sense to invest in a sector where the producer does not have any pricing power. This has resulted in significant divestment from the sector given lack of growth opportunities due to a restrictive, and anti-competitive regulatory environment. As our population continues to grow at one of the highest rates in the world, we need more investment in the healthcare sector, and not less. Policy measures that actually lead to divestment, rather than investment harm the long-term healthcare prospects of the country’s population.

There is an argument that if prices are not fixed then that may lead to price gouging. It is essential to understand that price gouging can only exist if a market is not competitive. It is the responsibility of the government, and the regulator to create an enabling environment for a competitive market. The government should only be in the business of providing an enabling environment, and ensuring stringent quality controls. Creating an environment where there is more investment in the sector, such that we not only meet local demand, but also develop backward integration through investment along the pharmaceutical value chain is critical for long-term sustenance, and growth of the healthcare segment.

Investment in backward linkages can potentially insulate pricing from depreciation of PKR while also enabling price stability. If the government wants price stability, and if it wants medicine prices to actually reduce in real terms, it needs to create a more competitive market, and we can never have a competitive market with consistently debunked notions of price caps. n

The pharmaceutical pricing crisis is just another example of how fixing prices does not work

Apple CEO Tim Cook paid a visit next door this April, to cut the ribbon in Mumbai and New Delhi as India welcomed its first Apple stores with exultation and sanguinity. The air was redolent with the sound of animated chatter as the event marked the evolution of Apple’s involvement in India. A new chapter in a relationship dating back to 2017 when India enticed Apple to outsource iPhone manufacturing. A relationship that has even led to Apple rivalling arch-rival Samsung in adopting India’s PLI’s scheme to net the country over $9 billion in phone exports this fiscal year alone.

We observed with bated breath and a twinge of envy as our rival made these strides. How did India manage to pull this off? How did it convince the world’s most valuable company to invest? These were just some of the many questions that ran through our minds as we witnessed the spectacle.

Our mobile industry, in contrast to its Indian counterpart, currently stares into the abyss. A paucity of raw materials and components has debilitated the industry, and its inability to open letters of credit portends a complete shutdown.

As Cook left India with a note expressing his eagerness to return, it was clear that India had made a lasting impression. For us looking on with envy, this only added insult to injury. The contrast couldn’t be more pronounced. It was hard not to imagine what it would be like if these stores had opened under the guise of Lahore’s minarets and not Delhi’s, or peppered with the briny zephyr of Karachi

and not Mumbai. How did we let another opportunity slip through our fingers? Does April’s situation offer a chance for reflection on our capabilities and limitations? In this momentary lapse in mobile manufacturing, we can ask: Should we expect Tim Cook on our shores anytime soon or will we repeat history by supporting an inferior industry?

For the sake of brevity, our story begins in 2019 with the creation of Transsion-Tecno Electronics: a joint venture between China’s Transsion Holdings and Pakistan’s Tecno Group. The company was to manufacture Transsion’s Itel, Tecno, and Infinix brands in Pakistan.

The very next year, the Engineering Development Board (EDB) doubled down by unveiling the Mobile Device Manufacturing Policy (2020). It aimed to facilitate mobile phone manufacturing by offering incentives such as:

• Regulatory duties and fixed income tax waived on CKD/SKDs for mobiles up to $350

• Higher fixed income tax on $351-$500 category by Rs 2,000 and $500 by Rs 6,300 on CKD/SKDs

• Measures to prevent misdeclaration

• 3% R&D allowance for local manufacturers exporting mobile phones

• Sustained tariff differential between CBU and CKD/SKD

• Local industry to follow a roadmap for localising value chain

The EDB granted licences to 30 compa-

nies to partner with international brands to locally manufacture mobiles. It even enticed global giants like Samsung, Xiaomi, and Oppo to partner with local partners such as Lucky Motors,Tecno Pack Electronics, and Exert Tech respectively.

If you think the policy resembles another sector’s policy framework under the EDB’s purview, you’re right. It’s uncannily similar to the automotive industry. However, the policy hit the ground running.

Locally built phones’ production numbers shot up from 290,000 to 24.6 million in 2021, based on Pakistan Telecommunication Authority’s (PTA) statistics. Despite the economic crisis in 2022, mobile producers still churned out 21.94 million units. These numbers may seem large, but there’s still room to grow. Pakistan’s total number of cellular subscribers has only grown year-on-year.

Total cellular subscribers rose to 194.58 million at the end of 2022, with an average annual increase of 10.7 million between 2017 and 2022. These 10.7 million subscribers are completely new customers. This means companies can target existing customers and are also guaranteed 10.7 million new customers every year based on the past half-decade trend.

It seems like an incredibly lucrative business. The only thing grander than its potential are the towering claims it has made regarding its position in Pakistan’s economy. “This is a sunrise industry, bursting with opportunity. With proper nurturing, it has the potential to generate a staggering $10-15 billion in export earnings,” declares Muzzaffar Hayat Piracha, CEO of Air Link Communication and Senior Vice Chairman of the Pakistan Mobile Phone Manufacturers Association. Piracha’s Air Link is one of 30 licensed companies that manufacture mobile phones in Pakistan both directly, and through its subsidiary Select Technologies.

“Given a free hand, we could contribute $10-15 billion to the exchequer in export earnings over the next 3-5 years. If we follow Vietnam’s example, then over the next 5-10 years we could even earn $40-50 billion,” Piracha elaborates. For context, Pakistan’s exports for

Muhammad Naqi, CEO of Premier Code

FY 2021-22 stood at $31.782 billion according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS).

“Not even a single rupee worth of letters of credit (LC) can be accessed, leaving us without raw materials needed for production. The industry teeters on the brink of closure,” warned Piracha. “In all honesty, the industry has already shut down. The question is whether it will collapse entirely. Major global brands like Samsung and Xiaomi stand poised to abandon Pakistan,” Piracha continued.

So what’s the solution? “If we are granted LCs again, then the sector will resume production. It was booming,” posits Piracha.

We could end the article here; we have chronicled this nascent sector’s journey. But this moment of halt begs the question: what are we even doing here? This sector has come out of nowhere for most of us and makes mind-boggling claims.

How many of us knew that our Samsung phones are made here? Or that they’re made by the same company which makes the KIA Sportage? This lapse in production is our opportunity to ensure our Samsung phones don’t suffer the same fate as their estranged

Profit has scoured State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) and PBS’ trade data to find the value of mobile phones exported, but came up empty-handed. This is odd because mobiles are listed as an easily identifiable import item. So why isn’t the reverse true?

“If it isn’t a listed item, then the volume probably doesn’t merit it,” says Dr Aadil Nakhoda, Assistant Professor at IBA. Profit searched for any export data, and could only find three instances. The PTA highlighted how Inovi Telecom had exported to the UAE in August 2021 and December 2022. The only other instance relates to Razak Dawood lauding Air Link for exporting locally built mobiles to the UAE in September 2021. And that’s about it. This is a far cry from the $1 billion that the industry aimed to achieve by June 2022.

While some suggest sinister reasons for why local companies are not exporting, Profit suggests an alternative. In their current capacity, they simply cannot.

This industry is headed for an automotive-style trainwreck if we don’t get our act together. We need robust policies and a serious push for localisation. If we’re importing $14.75 billion in raw materials to hit $15 billion in exports, what are we really exporting?Hayat Piracha, CEO of Air Link Communication

The UAE and ‘African countries’ are the only cited markets where these phones have been exported. Piracha claims phones are also being exported to Saudi Arabia and Oman, but this cannot be corroborated. Maybe it’s just him exporting there?

“Let’s examine the markets touted as export destinations. The Middle East is a highend market dominated by Apple and Samsung. A phone made directly by Samsung in Vietnam is cheaper than one made through a joint venture (JV) in Pakistan. They can directly export phones from their subsidiary in Vietnam to the Middle East and reap the profits themselves. Why share profits with a local partner in Pakistan?”, says Muhammad Naqi, CEO of Premier Code.

Naqi’s Premier Code is one of the 30 mobile phone manufacturing companies. However, it has gone the mobile route alone rather than entering a JV with any international manufac-

turer like most others in the industry.

“Looking at Africa, Egypt is also big on manufacturing. Samsung and Nokia have their own manufacturing centres there. Even if our local players could beat Samsung and Nokia in terms of costs, African countries are bound by free trade agreements. If you export to Africa, how would you have a cost advantage against a company based there?” Naqi adds.

The lack of a potential cost advantage, and subsequent un-exportability raises the spectre of comparison with the one industry that mobile manufacturers ideally want to stay clear of: the automotive industry.

“Mobiles are a necessity, cars are a luxury,” declares Piracha.

“Your phone is your lifeline. Forget it at home? You turn back. But no car? No problem. Catch a ride,

pedal a bike, hop on a bus, or hail a rickshaw,” Piracha adds.”The mobile industry boasts massive volumes, unlike automotive which has never exported anything. With $10-15 billion in potential exports, localisation is inevitable,” Piracha reflects. Piracha draws comparison with the automotive industry by using the word ‘necessity’.

“Cars are essential too. How can you label a Mehran a luxury?” asserts Nakhoda. “The Mehran was an affordable alternative to a motorcycle. It was the people’s car. But with each price hike, it slipped out of reach for the average person,” Nakhoda adds.

“Why do they crave import duties on mobiles if they’re essential goods? How can there be a tariff on a necessity? If the government imposes duties on flour or sugar one day, they could vindicate it by claiming these goods are necessities. It’s preposterous,” Nakhoda exclaims. “If mobiles are necessities, are we establishing value chains that will never produce iPhones or other high-end phones? It’s mind-boggling,” Nakhoda questions.

The comparisons transcend mere slip of tongue and accidental coincidences. They align with technical capacities too.”Localisation? At best, you can only localise 10-15% of a mobile’s value. Certain things cannot happen in Pakistan,” Naqi asserts.

“Take chipsets. The investment required is astronomical. Even if you could muster the funds, the water needs are immense. Manufacturing chipsets is a water-guzzling industry and Pakistan is water-scarce. The clean water requirement means it’s a non-starter,” Naqi explains.

“LCD screens? The market isn’t big enough for anyone to consider manufacturing here. Only five to six companies in the world make LCDs. Setting up manufacturing in Pakistan would require massive investments that local groups can’t undertake. Samsung invested $500 million to set up its LCD plant in India. Their government gave rebates and concessions which ours would struggle to match,” Naqi elaborates.

“And cameras for phones? Those also cannot be made in Pakistan,” Naqi adds. Naqi’s outlook is grim. Nakhoda doesn’t mince words: ‘If they can’t cut it on cost, they won’t export. They’ll just lobby to jack up duties

Given a free hand, we could contribute $10-15 billion to the exchequer in export earnings over the next 3-5 years. If we follow Vietnam’s example, then over the next 5-10 years we could even earn $40-50 billion.

Muzzaffar

and cash in on domestic margins. It’s a tale as old as time - it happened in automotive and mobiles could be next,”.

The situation is quite bleak. However, not having a sector is easier than scrapping one. It’s also not as if the sector is left gasping for straws. It’s new, there are underlying realities that favour it. Do they know it is the question?

Dr Aadil Nakhoda, Assistant Professor at IBA

Naqi pulls no punches: “This industry is headed for an automotive-style trainwreck if we don’t get our act together. We need robust policies and a serious push for localisation. If we’re importing $14.75 billion in raw materials to hit $15 billion in

exports, what are we really exporting”?

There are several low-hanging fruits ripe for the picking in the sector. According to PTA’s statistics, half of Pakistan’s mobile users have feature phone users. These phones, with their relatively simple manufacturing vis-à-vis smartphones, provide opportunities for economies of scale. Phone manufacturers are cognisant of this. The majority of locally made phones are feature phones. The disparity in scale between feature phones and smartphones raises questions about potential synergies between the two segments. However, the silver lining is that smartphone production could increase to meet unmet demand if LCs for import become obtainable as Piracha claims. Even if the idea seems far-fetched amidst the current crisis.

“If the principal’s skin is not in the game, they will not work on localisation, exports, or technology transfer,” asserts Naqi.”We can start working on patents and intellectual property rights in the processes that have been brought over. Once we start incorporating these, localisation in terms of the value of the mobile phone will increase,” he elaborates.

“A low-hanging fruit is how India enticed chipset manufacturers to set-up their testing centres,” Naqi reveals. “They initiated the process of having companies outsource their labour to India,” he adds. “This was followed by R&D labs, and eventually other large-scale processes. India leveraged Foxconn to convince Apple to increase their investment in India,” he continues.

The clock is ticking. Staring at our neighbour green with envy won’t do us much good if we remain silent spectators.

The mobile manufacturing industry stands at a crossroads, teetering on the precipice of triumph or tragedy. Can it achieve cost advantages and fulfil its promises to export? The stakes are high. Pakistan cannot afford to nurture another industry that relies on taxpayer largesse. It cannot have another nascent industry, dubbed a sunrise industry, become a foundering rather than delivering on its promises. This momentary lapse in production provides opportunities to discuss what the sector is, what it should be, and most importantly what it absolutely should not be. n

Why do they crave import duties on mobiles if they’re essential goods? How can there be a tariff on a necessity? If the government imposes duties on flour or sugar one day, they could vindicate it by claiming these goods are necessities. It’s preposterous

By Shahnawaz Ali

By Shahnawaz Ali

If there is one thing that people remember about the economic policy of the short-lived tenure of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, it was the two-wave process of nationalisation. Backed by a socialist rationale, Bhutto’s nationalisation was an attempt of the devolution of power from the hands of the poor into the hands of the public.

It’s been 50 years since the decision was made by Bhutto. Over the years, most of the businesses that Bhutto nationalised, have been privatised once again, but the ones that haven’t, live to serve as a case study of how socialism and the developing world do not go hand in hand.

What, however, cannot be attributed to Bhutto is the current portfolio of Pakistan’s State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Pakistan has a total of 212 state owned entities, 85 out of which are commercial entities. A recent report published by the World Bank has named Pakistan’s SOE’s as the worst in Asia. Within the coming week, it is also expected that the finance division will table an SOE bill in Parliament. The bill represents the actions proposed in the latest WB report.

To understand how Pakistan decided to use the findings of the WB report to implement a strategy of obtaining a result that would identify what to do with which SOE, we have to go back to the start. Once we do that, we will look at the viability of this strategy itself.

Since the financial year 2014-15, Pakistan’s SOEs have been in a net loss.

Every year, the loss gets higher. As of FY18, Pakistan recorded a cumulative total of Rs 286 billion in net losses incurred by SOEs. It is important to remember that net losses also account for all the SOE’s that have made a profit. The projections after 2019 are missing in the report but it is no secret that the net profit of the SOEs of Pakistan is still below 0.

The recent World Bank report revealed that Pakistan’s SOEs eat more than Rs 458 billion in public funds annually just to stay afloat and their combined loans and guarantees rose

to almost 10 percent of GDP or Rs 5.4 trillion in FY21, up from 3.1 percent of GDP (Rs 1.05 trillion) in 2016. The report deems the SOEs of Pakistan as the worst in Asia.

The “State-Owned Enterprises Triage: Reforms & Way Forward” that was initially published by the world bank and later by the finance division in 2021 states that 90% of the losses incurred by the state owned enterprises can be attributed to the top 10 loss making entities. Hence these “white elephants” is where the problem essentially lies.

Logically, these entities would be concentrated on and would be on the priority list for privatisation however, that is not the case. The proposed solution itself, is what the “triage” is all about.

The World Bank report highlighted a framework designed to help policymakers make informed decisions about whether to retain, restructure, or divest SOEs based on their strategic importance, financial performance, and social impact.

The proposed framework includes the following steps:

1. Strategic importance: This step involved assessing the strategic importance of each SOE by analysing its role in the economy, its contribution to public policy objectives, and its potential for private sector competition. SOEs that were deemed to have strategic importance would be retained by the government.

2. Financial performance: This step involved analysing the financial performance of each SOE by looking at its profitability, efficiency, and solvency. SOEs that were financially sound would be retained, while those that were financially unsustainable would be divested.

3. Social impact: This step involved analysing the social impact of each SOE by as-

sessing its contribution to employment, income distribution, and public service provision. SOEs that had a positive social impact would be retained, while those that had negative social impacts would be restructured or divested. Based on this model that was devised in 2019, and approved in 2021, the result of assessment has finally made its way to the parliament.

Much to the disappointment of a lot of Pakistanis, most of the top 10 loss making entities have not been made a part of the privatisation list in the first phase. The Finance Division has decided to retain PIA, Pakistan Railways, and Pakistan Post along with most of the DISCOs and GENCOs that are expected to be privatised in the “next phase”. Owing to the ongoing political instability in Pakistan, “next phase” often means a halt for the foreseeable future.

But what is it that allows the state to keep these entities, even after them being a complete waste of the fiscal capacity? Loopholes.

As standardised as the process looks, the whole triage methodology is contingent upon political wishes. Words like triage, and strategic importance often have a convoluted assessment.There is a huge difference between how the world bank defines strategic importance and how it is assessed in this case.

Let us take the example of PIA. In the undying words of businessman and Ex finance minister Miftah Ismail, “The state has no business running airlines and railways.”

What he said almost a year ago, is still etched on the financial statements of the Pakistan International Airlines. The airline made a loss of Rs. 41 billion in the first half of 2022. Even though this was Rs. 16 billion worse than the same period in the previous year, it is important to remember that the net loss in that period was also positive, i.e; Rs. 25 billion. As per the consolidated financial statements of PIA, the airline has its total liabilities in excess of $3 billion dollars.

Similarly, the Pakistan railways has incurred losses in excess of Rs. 150 billion in the last 3 years. And while there is some competition for PIA with other indigenous airlines, Pakistan Railways operates as a sole operator in its sector. So what strategic mission is there to be obtained from these entities? Strategic importance is defined by the world bank by its relation with promoting private sector contribution, with the current pakistani airlines not being internationally acclaimed, and PIA incurring losses for the last 6 years, no social, strategic and financial logic seems to be justifying the retention of PIA.

Even if retention of these companies is

“The state has no business running airlines and railways”

Miftah Ismail, Former Federal Finance Minister

accepted as the fate, the current plan also fails to mention an improvement in corporate governance framework after retention. In its article about Pakistani SOEs published in 2021, the International Monetary Fund writes, “Consistent with survey results, an IMF technical assistance mission in early 2020 noted that the corporate governance of SOEs in Pakistan was weak, which may explain—at least in part—the performance of the SOE portfolio, displaying low productivity and efficiency levels”. Sadly the organisations are still privy to pre-colonial frameworks of bureaucracy and are slow to take off with time.

It is important to mention that organisations can hold a strategic importance for the government. Organisations like ZTBL, which are also amongst the loss making entities do play a huge role in agricultural policy. Similar arguments can be made for the Broadcasting corporations or even the DISCOs. But it’s high time the government prioritises the sectors that it can be a part of, and leave the rest until it is not as cash strapped as it is in the current circumstances. The organisations on the privatisation list include prominent entities like Pakistan Steel Mill and OGDCL.

When it comes to improving the financial health of SOEs, the commercially feasible solution has been privatisation since the last 2 decades. However the willingness to do so by the governments has

always been a big question mark. Not only has the issue been politicised, it has had different solutions proposed by different parties over the years.

The PML(N)’s stand on privatisation

has mainly been open, however there has been little to no actionable plan to execute their political slogans. On the other hand, the PPP has always maintained a stance akin to Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s on nationalisation.

The PTI government, when they were in power, largely went with a trial and error approach. After trying various things, they were finally made to land upon this standardised triage by the IMF. The PDM has shown consistency with the same plan, be it as a policy measure or out of necessity.

The bill being tabled by the PDM, with there being no functional opposition in parliament at the moment, may well be passed. But that is only the first step. As we have seen multiple times before, privatisation is an unpopular move that carries a political cost. Apart from the tedious task of looking for a willing and appropriate buyer, there is the negotiation phase that takes time.

A lot can happen during that. Employees of the entity being privatised can hit the streets, as witnessed under PML-(N)’s last tenure when they moved forward with PIA’s privatisation. Other times, the courts have gotten involved; the Supreme Court disrupting the sale of Pakistan Steel Mills is a case in point.

The WB Triage report method may be something new and perhaps even workable. But it will certainly take more than just the passing of law based on said report to cure Pakistan’s worsening SOE headache. n